Abstract

Bacteria that surround plant roots and exert beneficial effects on plant growth are known as plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR). In addition to the plant growth-promotion, PGPR also imparts resistance against salinity and oxidative stress and needs to be studied. Such PGPR can function as dynamic bioinoculants under salinity conditions. The present study reports the isolation of phytase positive multifarious Klebsiella variicola SURYA6 isolated from wheat rhizosphere in Kolhapur, India. The isolate produced various plant growth-promoting (PGP), salinity ameliorating, and antioxidant traits. It produced organic acid, yielded a higher phosphorous solubilization index (9.3), maximum phytase activity (376.67 ± 2.77 U/mL), and copious amounts of siderophore (79.0%). The isolate also produced salt ameliorating traits such as indole acetic acid (78.45 ± 1.9 µg/mL), 1 aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate deaminase (0.991 M/mg/h), and exopolysaccharides (32.2 ± 1.2 g/L). In addition to these, the isolate also produced higher activities of antioxidant enzymes like superoxide dismutase (13.86 IU/mg protein), catalase (0.053 IU/mg protein), and glutathione oxidase (22.12 µg/mg protein) at various salt levels. The isolate exhibited optimum growth and maximum secretion of these metabolites during the log-phase growth. It exhibited sensitivity to a wide range of antibiotics and did not produce hemolysis on blood agar, indicative of its non-pathogenic nature. The potential of K. variicola to produce copious amounts of various PGP, salt ameliorating, and antioxidant metabolites make it a potential bioinoculant for salinity stress management.

1. Introduction

The excess use of agrochemicals has resulted in the depletion of nutrients and useful rhizobia from soil [1]. The continued use of these chemicals has also severely affected soil fertility, soil health, agro-ecosystem, and human health [2]. These negative impacts of agrochemicals highlight the need for sustainable substitutes [3]. The salinity of agricultural soil, i.e., the presence of excess amounts of salts, is one of the major abiotic stresses [4,5]. Soil salinity is an increasing problem worldwide for about 27% of the world’s arable land [6]. Plant growth in these soils is adversely affected by both excess salts and excess sodium levels [7]. Saline soil prevents the normal growth of crops and results in poor crop yield [7]. The effects of soil salinization are more detrimental, particularly in arid and semi-arid regions.

The use of organic manure and farmyard manure has been successful in restoring soil health and soil fertility, however, these are less effective and not sustainable [4]. The various conventional methods of ameliorating soil salinity have provided some success, but they show negative impacts on soil health [6]. A sustainable agriculture practice demands effective and eco-friendly measures to combat these issues without compromising soil health [7]. In this context, the application of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) has proved the best alternatives to agrochemicals and effective bioinoculants to promote plant growth in saline soils [1]. PGPR exerts a spectrum of beneficial effects on crop plants, including plant growth promotion and the amelioration of soil salinity and antioxidant activities [8]. PGPR helps plant growth through phosphate, iron, and other mineral nutrition, provision of nitrogen, ammonia, and phytohormones [1]. Aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate deaminase (ACCD) produced by PGPR promotes root growth [6]. PGPR also excrete exopolysaccharides (EPS) which help in salinity amelioration [8]. Applications of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) are known as effective, and sustainable inputs for the replenishment of soil nutrients, plant nutrients, and plant health [9]. Various reports claim that the application of PGPR for sustainable improvements in nutrients and the health of soil and plants [4,9,10,11]. PGPR are known to produce a wide variety of plant growth-promoting traits that include siderophores [10,11], phytohormones [12,13], hydrolytic enzymes [14], exopolysaccharide [15,16,17], stress-tolerant metabolites [18,19,20,21], and phosphate solubilization [22,23], etc. PGPR through these metabolites promotes seed germination, root and shoot growth, the level of soil and plant nutrients [13,21,24]. The beneficial effects of PGPR are sometimes not obtained due to various reasons such as the production of a limited number of plant growth-promoting (PGP) traits, competition with the native soil microflora, less root colonization, and sensitivity to biotic and abiotic stresses [2,3,20]. A multifarious and stress-tolerant PGPR can serve as an effective bioinoculant and stress elevator [25] that also helps in restoring soil health [26,27]. To be used as an effective bioinoculant, it is desired to confirm the multifarious plant growth-promoting, salinity ameliorating, and antioxidant ability of such PGPR. Therefore, the present study was aimed to screen multifarious PGPR with the potential of producing, PGP, salinity ameliorating, and antioxidant metabolites. The present study reports the isolation of Klebsiella variicola SURYA6 isolated from wheat rhizosphere and the production of multiple PGP, salinity ameliorating, and antioxidant traits.

2. Results

2.1. Production of Plant Growth-Promoting Traits

2.1.1. Screening for Phytase Production

A total of 34 bacterial isolates were obtained from the collected soil samples. Four isolates, namely N6, H7, B1, and V8 produced larger zones of P solubilization among the other isolates, hence they were selected for further studies. The isolate N6 yielded maximum P solubilization index (9.3 mm) and maximum phytase activity (376.67 ± 2.77 U/mL) vis-à-vis other isolates (Table 1). Among the 34 isolates, four isolates showed a clear zone on PVK and KB agar plates. The isolate N6 showed maximum P solubilization on PVK agar and in PVK broth (Table 1).

Table 1.

Screening for the production of PGP traits of various isolates.

NA plates supplemented with the pH indicator dye and separately inoculated with four isolates, namely N6, H7, B1, and V8, showed a change in the color of the medium from yellow to pink, surrounding the colonies of these isolates. This color change in the color of colonies indicated the production of organic acids. Isolate N6 showed dark, intense pink color as compared to the other isolates.

2.1.2. Screening for Nitrogen Fixation, Production of Ammonia and Siderophore

All the isolates were found to grow luxuriously on nitrogen-deficient MM (Table 1) indicating their nitrogen fixation ability. All the isolates produced ammonia and siderophore in varying amounts, however, the isolate N6 produced maximum amounts of ammonia and siderophore units (79.0%) as compared to the other isolates (Table 1), and hence it was considered as multifarious PGPR.

2.2. Production of Salinity Ameliorating Traits

The isolate N6 produced the maximum amount of IAA, ACCD, and EPS compared to the H7, B1, and V8 isolates (Table 1).

2.3. Screening for Antioxidant Enzymes

Among the various isolates, isolate N6 produced higher activities of SOD (13.86 IU/mg protein), CAT (0.053 IU/mg protein), and GSH (22.12 µg/mg protein) (Table 1).

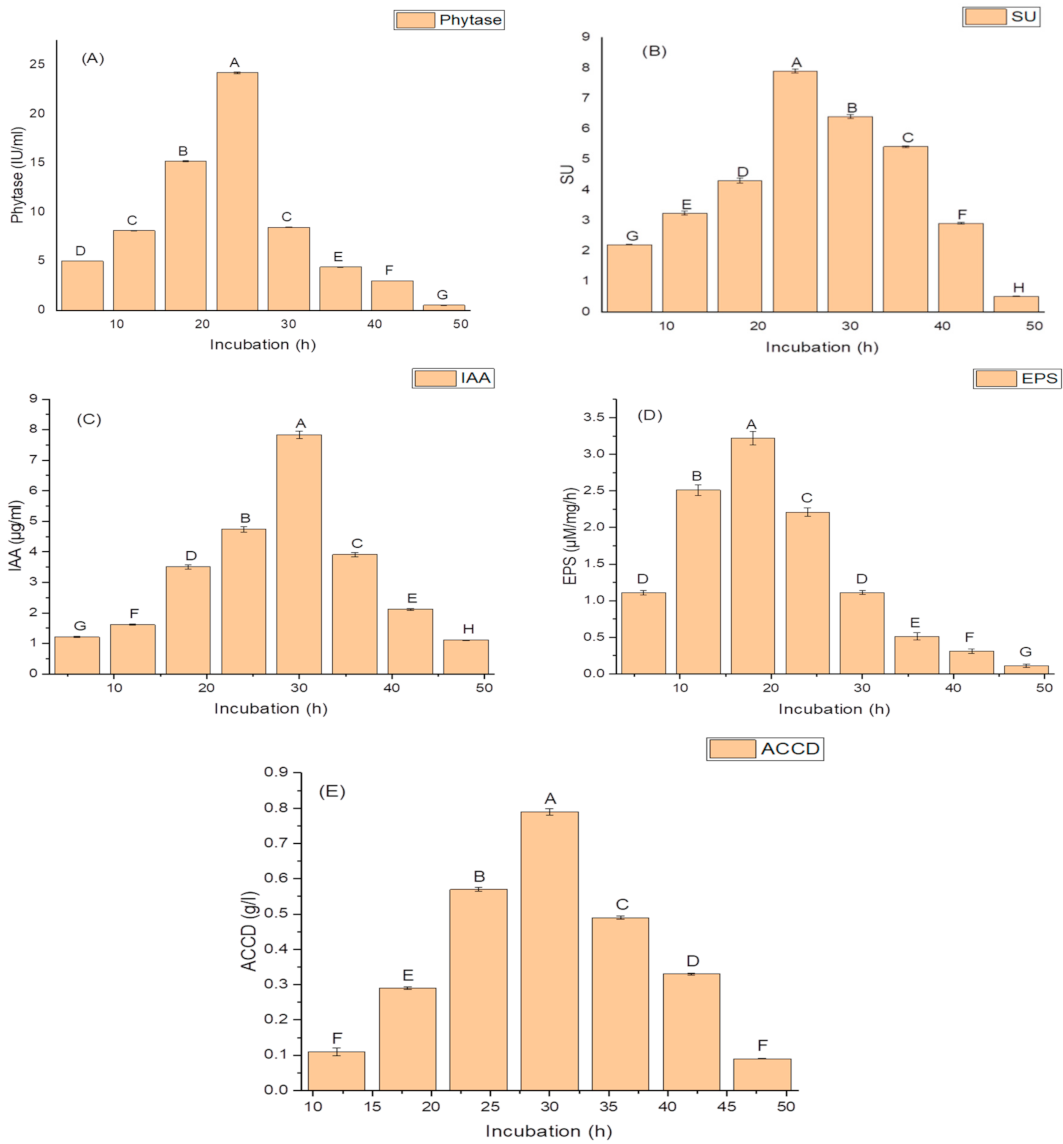

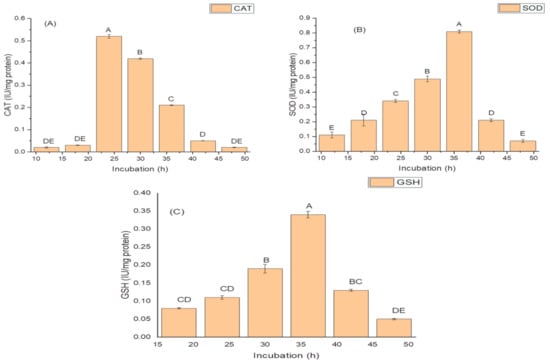

2.4. Effect of Incubation Period on Growth, and Production of PGP and Antioxidant Traits

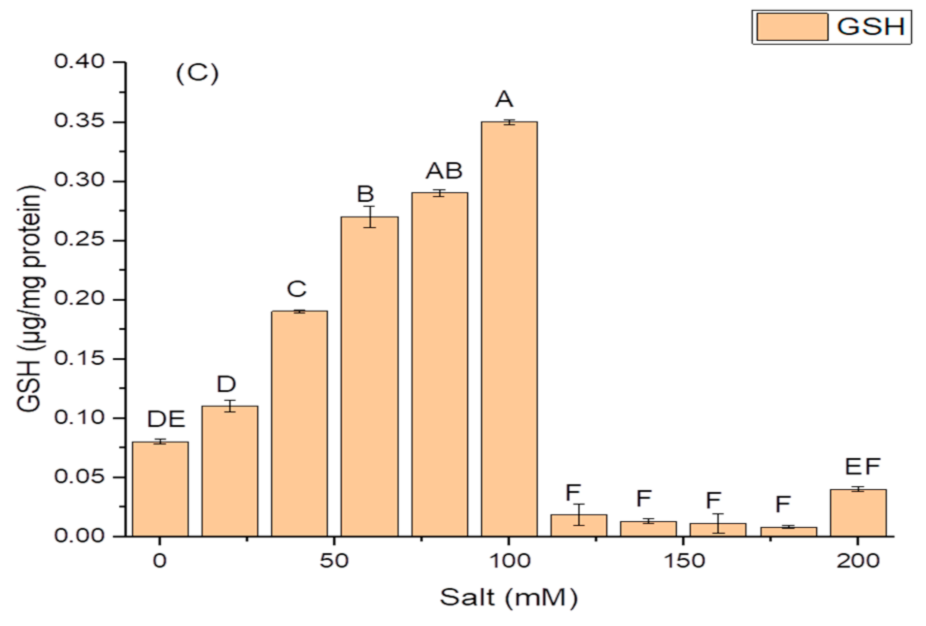

Growth phases of isolate N6 showed a lag phase of 4 h, an active exponential phase from 6 to 30 h, a stationary phase after 30 h, and a decline phase from 36 h onwards. Production of PGP and antioxidant traits began from 12 h and continued up to 48. The maximum amounts of PGP traits and antioxidant enzymes were produced during the end of the exponential phase (30 h). A significant decline in the amounts of these traits occurred after 30 h growth. The isolate N6 produced a maximum phytase activity of 8.46 ± 2.1 (IU/mL) (Figure 1A); optimum siderophore yield (77.42 ± 1.9 SU); (Figure 1B), IAA (78.45 ± 1.9 µg/mL) (Figure 1C), maximum EPS yield of 32.2 ± 1.2 g/L (Figure 1D) and highest ACCD activity (0.891 M/mg/h) (Figure 1E) during 30 h of incubation.

Figure 1.

Effect of the incubation period on (A) phytase activity; (B) the production of siderophore units (SU); (C) Indole acetic acid (IAA) production; (D) Exopolysachharide (EPS) production; and (E) 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate deaminase (ACCD) activity of K. variicola SURYA6. Values are the average of five replicates and were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Turkey’s test. Different letters on mean value of each parameter indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

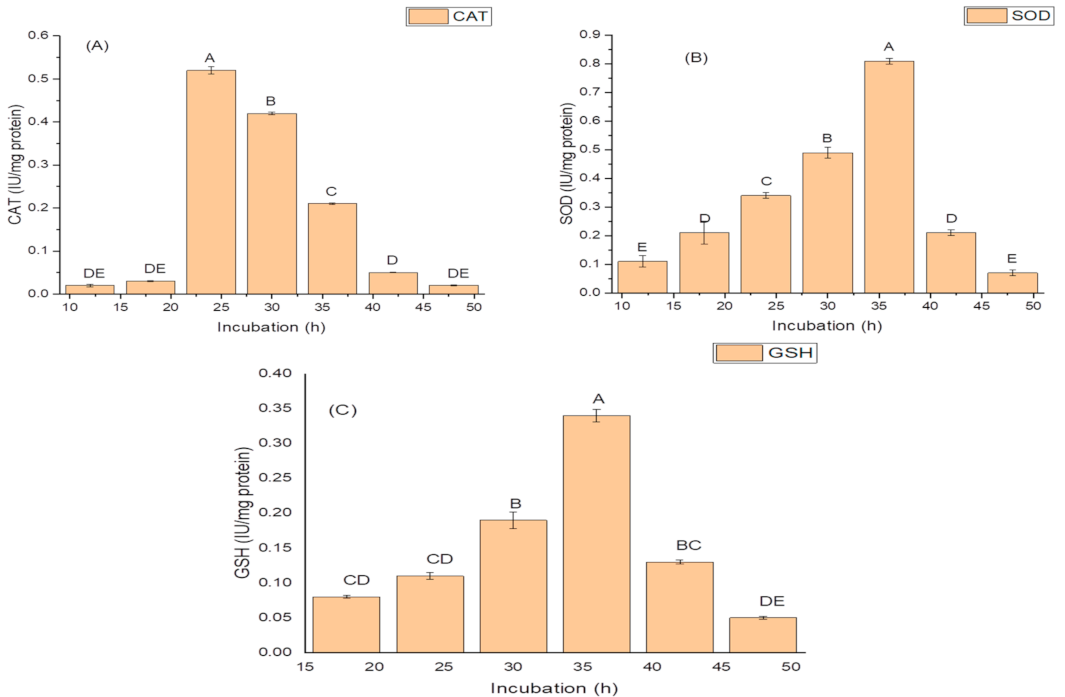

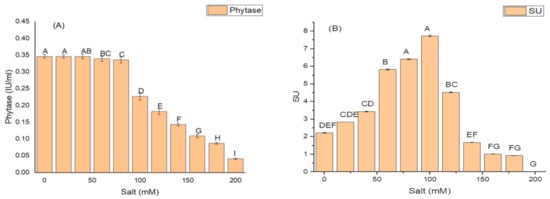

The highest activities of antioxidant enzymes were also recorded during the log phase (30 h) of growth. The isolate exhibited optimum CAT activity, i.e., 0.81 IU/mg protein during 24 h of growth; (Figure 2A); while it produced the highest SOD activity of 14.96 IU/mg protein (Figure 2B); and the maximum GSH oxidase activity of 34.09 IU/mg protein (Figure 2C); during 36 h of incubation (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Effect of the incubation period on (A) catalase (CAT) activity; (B) superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity; and (C) glutathione reductase (GSH) activity of K. variicola SURYA6. Values are the average of five replicates and were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Turkey’s test. Different letters on mean value of each parameter indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

2.5. Effect of Salt Concentration on Growth and Production of PGP Taits and Antioxidant Enzymes in K. variicola SURYA6

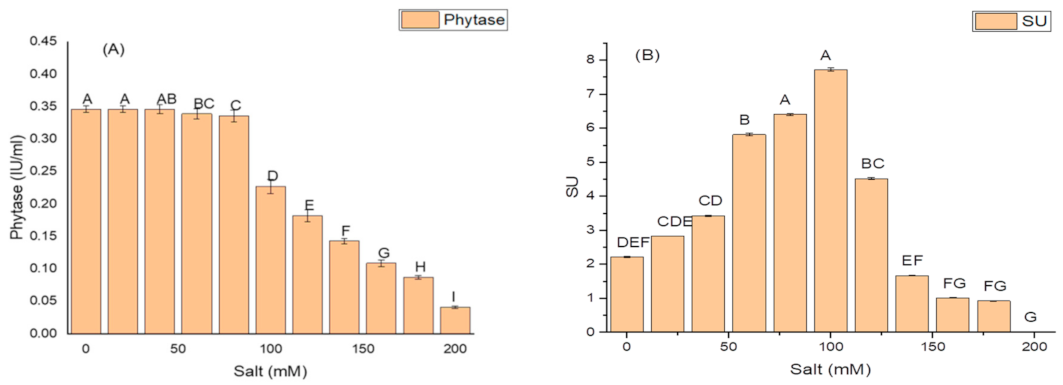

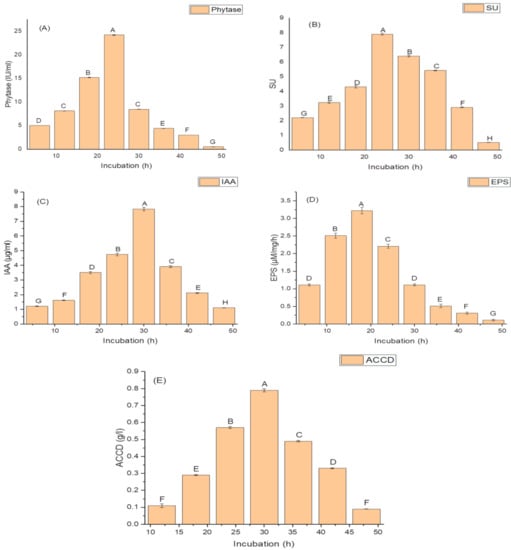

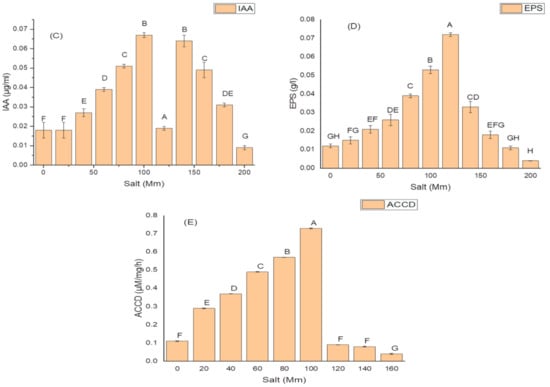

K. variicola produced a good amount of PG traits at a varying range of salt concentrations. An increase in the amounts of PGP traits was observed with increasing concentrations of salt. The threshold level of salt (NaCl) that inhibited phytase activity was 100 mM (Figure 3). Siderophore production (Figure 3B) ceased and was negatively impacted above 100 mM of NaCl concentration, while salt-ameliorating traits such IAA (Figure 3C), EPS (Figure 3D), and ACCD (Figure 3D) reflected a higher threshold level (120 mM) of salt. The maximum phytase activity of 8.46 ± 2.1 (IU/mL) was observed at 120 mM of NaCl (Figure 3A); the optimum siderophore units (77.42 + 0.18) were produced at 100 mM of NaCl (Figure 3B) while the highest amount of IAA (99.32 ± 1.8 µg/mL) (Figure 3C), maximum EPS (72.2 ± 1.1 g/L) (Figure 3D) and optimum ACCD activity (0.981 M/mg/h) (Figure 3E) were recorded at 120 mM of salt.

Figure 3.

Effect of salt (NaCl) concentrations on (A) phytase activity; (B) production of siderophore units (Sus); (C) IAA production; (D) EPS production; and (E) ACCD activity of K. variicola SURYA6. Values are the average of five replicates and were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Turkey’s test. Different letters on mean value of each parameter indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

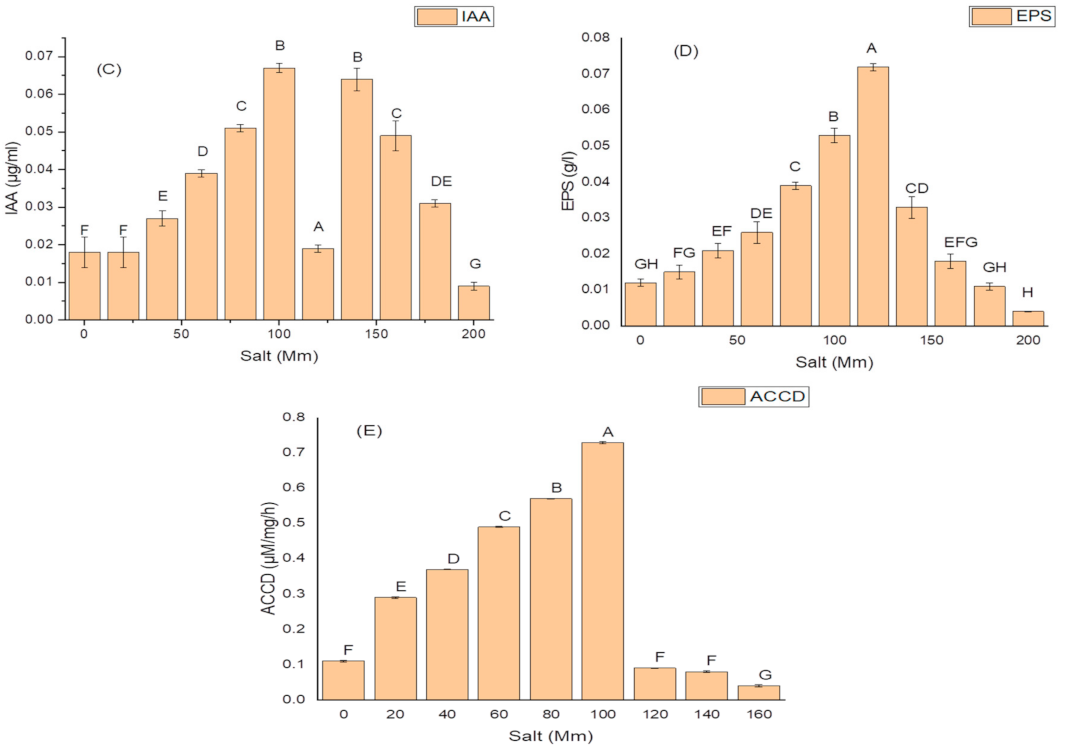

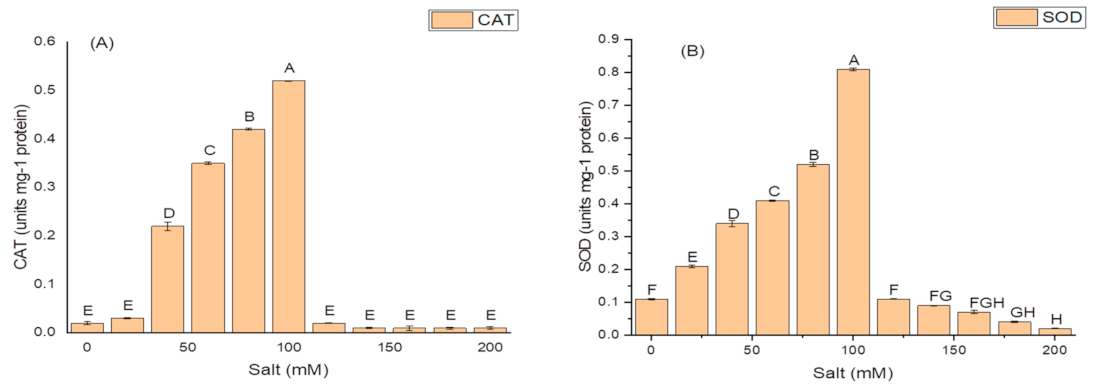

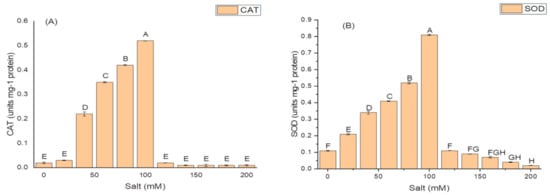

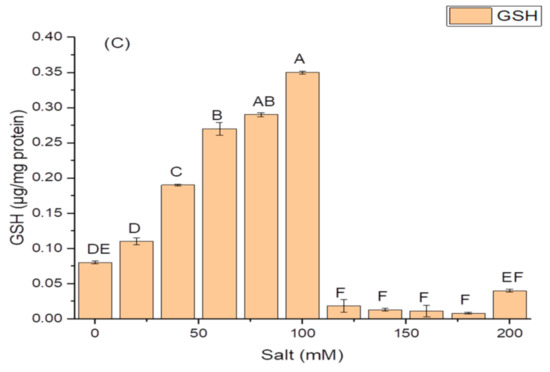

The isolate N6 produced the antioxidant enzymes at all the concentrations of salt, however, NaCl concentration above 100 mM significantly affected the production of these enzymes. The optimum CAT activity, i.e., 0.55 ± 1.7 IU/mg protein (Figure 4A); SOD activity of 82.21 ± 1.9 IU/mg protein (Figure 4B); and maximum GSH oxidase activity of 35.09 ± 1.8 IU/mg protein (Figure 4C); were obtained at 100 mM salt (NaCl) concentration.

Figure 4.

Effect of salt (NaCl) concentrations on (A) catalase (CAT) activity; (B) superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity; and (C) glutathione reductase (GSH) activity of K. variicola SURYA6. Values are the average of five replicates and were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Turkey’s test. Different letters on mean value of each parameter indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

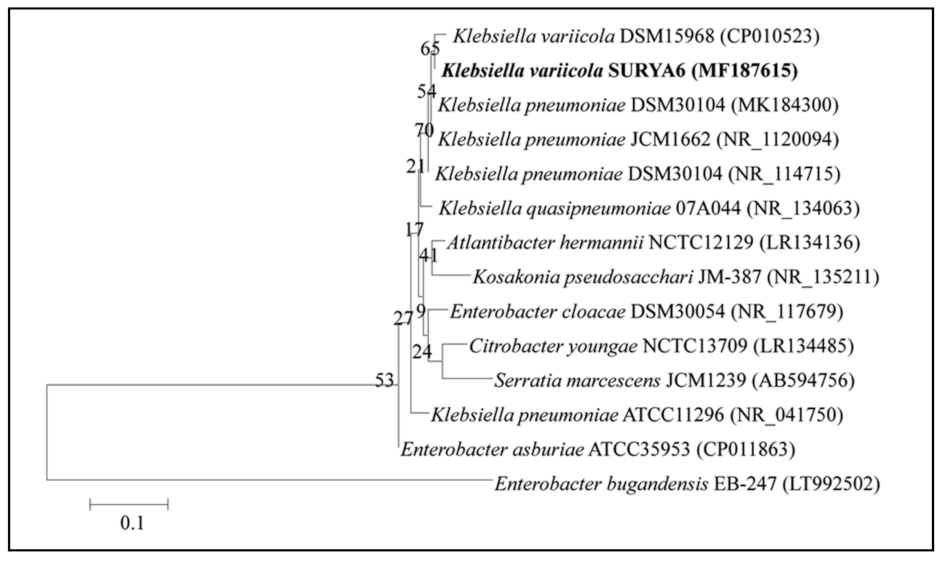

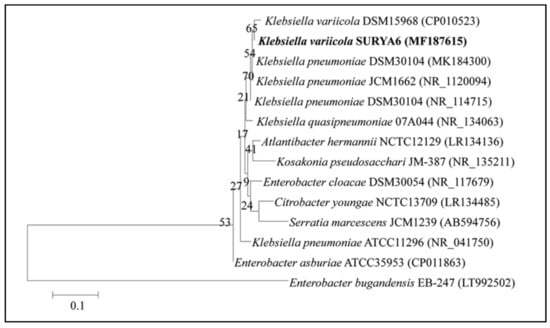

2.6. Identification of the Potent Isolate-Ribotyping

Comparison of 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis of isolate N6 exhibited 99.82% similarity with Klebsiella variicola (Figure 5), thus the isolate was identified as Klebsiella variicola, and 16S rRNA gene sequences of the isolate were deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) gene bank under the name Klebsiella variicola SURYA6 with the accession number MF187615.1.

Figure 5.

A phylogenetic tree showing the relatedness of the isolate N6 to other members of Genus Klebsiella. The 16S rRNA gene was amplified on PCR followed by electrophoresis. Amplified sequences were identified using the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database and a phylogenetic tree was constructed.

3. Discussion

Agricultural soil is a rich source of a diverse population of PGPR [6,9]. These PGPR provide several benefits to the plants such as plant growth promotion, the enrichment of plant nutrients, as well the enrichment of the nutrients in soil [1]. They exert a wide variety of plant beneficial activities such as N2 fixation, the production of IAA, ammonia, HCN, siderophore, EPS, and P solubilization [5,12]. In addition to plant growth-promoting effects, PGPR produces a wide range of metabolites that protect the plant from oxidative damages caused due to the excess of salts [16,17,18].

The phytase-producing soil bacteria widely occur in the rhizosphere of different plant species [26,27,28,29,30]. Phytase-producing K. variicola sp. has been isolated as endophytes from banana and maize leaves [31,32]. The isolate produced phytase and yielded a 39 mm clear zone of phytate solubilization. Singh et al. and Liu et al. reported the isolation of phytase producing Bacillus subtilis strain DR6 and Bacillus sp., respectively, from maize rhizosphere, they reported the 378 U/mL of phytase [29,30]. Reports of the present study on the phytase activity of K. variicola are in line with the reports of Singh et al. [28]. This study reports the highest phytate solubilization index than K. pneumonia isolated from the rhizosphere of sugarcane, and rice [31,32,33].

P solubilization is attributed to the secretion of phytase and the production of organic acids that decrease the pH of the medium. The secretion of phytase has been reported as the key factor in P solubilization [34,35]. The production of IAA is regarded as the principal criterion for screening PGPR because IAA-producing bacteria are known to exert profound beneficial effects on plant growth [6]. The production of ammonia has been reported in many P solubilizing Klebsiella sp. isolated from the various plant rhizospheres [33,34].

The production of ammonia is a well-known mechanism of PGPR adopted for plant growth promotion [35,36]. Bhardwaj et al. [30] isolated phytase positive, P solubilizing, and IAA producing multifarious K. pneumonia from the rhizosphere of sugar cane. Kuan et al. reported two sp. of Klebsiella namely Klebsiella sp. Br1 and K. pneumonae Fr1 to fix N2, solubilize P, and produce IAA [37]. Sachdev et al. reported the production of IAA in six strains of K. pneumoniae isolated from the wheat rhizosphere [38]. Mazumdar et al. isolated P solubilizing K. pneumoniae rs26 from the chickpea rhizosphere. They also reported N2 fixation and IAA production in this isolate [33]. Rosenblueth et al., reported N2 fixation activity in K. variicola [30]. Govindarajan et al. isolated Klebsiella sp. GR9 from sugarcane rhizosphere and found the bacterium capable of producing multiple plant growth-promoting traits [39].

Sayyed et al., reported siderophore production in Achromobacter sp. isolated from d rhizosphere [9]. Shaikh et al. observed siderophore production in Pseudomonas sp. isolated from the banana rhizosphere [8]. Haahtela et al. reported enterochellin siderophore production in K. pneumoniae and K. terrigena isolated from plants [40]. These isolates also produced auxins and IAA. Marasco et al. reported multifarious Klebsiella sp. from pepper rhizosphere [41].

EPS production has been reported in various members of Klebsiella sp. such as K. oxytoca [42], K. pnuemoniae [42,43], K. pneumoniae sp. pneumoniae serotype K63 [44], and Klebsiella sp. PHRC1.001 [45]. The production of EPS by rhizobacteria is one of the useful traits, as it chelates excess salt ions, thus protecting the plant from the osmotic effects of salts [45,46]. K. variicola SURYA6 exhibited higher yields (32.2 ± 1.2 g/L) of vis-à-vis K. oxytoca (6–15 g/L) reported by Hariyono [47], and K. pneumoniae strain DSM 30,104 (1.75 mg/mL) reported by Dlamini et al. [48].

The ability of the isolate to grow in high concentrations of various salts can be attributed to the excretion of EPS that maintains the viability of bacterial cells under salt stress and protects them in the rhizosphere [6]. Good growth of the isolate at higher concentrations of a wide variety of salts indicates its halophilic physiology and its ability to survive under salinity stress. Halophilic organisms grow at higher salt levels (100–300 mM) as they can maintain the balance of the osmotic pressure of the environment and thus protect their enzymes and proteins [49]. Halophilic Klebsiella sp. isolated from the plant roots showed tolerance to higher levels (4 to 8% NaCl) of salts [22]. Singh et al., reported the growth of Klebsiella sp. at a higher level (6% of NaCl (Salt) [50]. The results of the present studies are in line with Arora et al. [51].

The majority of the PGP and salt-ameliorating traits are produced during the active/log-phase growth of PGPR [52]. Sayyed et al. and Reshma et al. reported the production of EPS, siderophore, and antioxidant enzymes during the exponential growth of Enterobacter sp. RZS5, Achromobacter sp., and Pseudomonas sp., respectively [9,15,53]. The reduction in growth and decreased synthesis of PGP metabolites and antioxidant enzymes is because of the reduced availability of nutrients, accumulation of toxic wastes, and unfavorable changes in the pH of the medium [18]. Rhizobacteria are known to ameliorate salinity stress through the production of ACCD [17,18]. Halophiles of Enterobacteriaceae sp. that are adapted to salinity stress produce an array of PGP metabolites [54] like siderophores [9,15], exopolysaccharides (EPS), phytohormones, and various stress-tolerant enzymes [53]. Sagar et al., reported the production of various PGP traits and ACCD in E.cloacae PR4 [16]. Jabborova et al., reported the production of various PGPR traits in halophilic endophytes [11].

Production of ACCD is attributed to the presence of ACC in MM [18] and the production of ACCD in PGPR is one of the best mechanisms of salinity tolerance [9]. The enzyme ACCD lowers the level of ACC in root exudates, the suboptimal level of ACC reduces the concentration of ethylene in the plant roots and thus helps in root length which improves the absorption of nutrients [9]. Srivastav and Kumar reported the 0.539 µM/mg/h activity of ACCD in Klebsiella sp. strain ECI-10A [55]. Singh et al. reported ACCD and other plant-growth-promoting activities in Klebsiella sp. SBP-8 isolated from Sorghum bicolor from the desert region of Rajasthan, India [50]. The isolate exhibited optimum growth and ACCD activity at high salt (NaCl) concentrations of up to 6%. The isolate ameliorated 150–200 mM of salt in wheat and promoted plant growth under salinity conditions. ACCD-producing rhizobacteria are widely studied as PGPR to elevate a variety of stresses in plants [56]. Acuña et al., isolated Klebsiella isolate sp. 8LJA and 27IJA from Parastrephia quadrangularis rhizosphere [56]. These isolates produced ACCD and SOD activities under salt stress (250 mM and 450 mM NaCl). The presence of ACCD and antioxidant enzyme-producing PGPR activates a defensive system in the plants which removes the free radicals produced due to salt or other stresses [57].

Antioxidant enzymes like SOD, CAT, and GSH produced by PGPR protect plants from oxidation due to osmotic shocks [3]. Sapre et al. isolated halophilic Klebsiella sp. IG 3 from Avena sativa rhizosphere [58]. Their isolate tolerated salinity stress up to 100 mM, produced IAA, proline, and antioxidant enzymes under normal and salinity stress conditions, and helped in salinity stress amelioration and growth promotion in A. sativa. The production of antioxidant enzymes in K. variicola is due to its halophilic nature. To prevent the oxidation of their important biomolecules to protect the cell from the osmotic damage of salts, halophilic microorganisms produce antioxidant enzymes [3]. Salinity conditions create oxidative stress that damages the cell membranes and cell structures in microbes as well as plant cells. Under salinity stress conditions, the presence of antioxidant enzyme-producing PGPR activates an antioxidative defensive mechanism in the plants and removes the free radicals produced due to salinity stress [57].

Multiple resistances to a wide variety of antibiotics are commonly exhibited by Klebsiella sp. associated with clinical infections [31]. However, the isolate, K. variicola SURYA6, exhibited sensitivity towards 26 different types of antibiotics; moreover, the inability of the isolate to grow on BA confirmed its non-clinical and non-pathogenic origin. Some reports showed that the K. variicola is associated with extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing ability, however, K. variicola SURYA6 did not show ESBL activity. Barrios et al. [25] claimed K. variicola was a versatile bacterium capable of colonizing different hosts such as plants, humans, insects, and animals. K. variicola of plant origin is non-pathogenic to humans or animals [59].

The ability of the isolate to grow under salinity stress through the secretion of salinity ameliorating and antioxidant metabolites and to secrete multiple plant growth-promoting characters makes it a good bioinoculant for plant growth promotion while removing the excess salts. However, multiple field studies over the period and under different agroclimatic conditions need to be explored to use this isolate as a bioinoculant at the commercial level.

4. Material and Methods

4.1. Soil Samples

Ten grams of rhizosphere soils of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) were collected each from four agroecological zones, namely the Valivade (16.7185° N, 74.3133° E), Hatakanagale (16.7446° N, 74.4467° E), Nandani (16.7262° N, 74.5434° E), and Balinga (16.6878° N, 74.1703° E) villages of Kolhapur District of Maharashtra, India.

4.2. Screening for Multifarious PGPR Isolate

4.2.1. Screening for Phytase Production

All the soil samples were individually mixed @ 1.0 g in separate sterile saline, serially diluted and 0.1 mL of 10−6 aliquots of each sample were individually incubated in sterile nutrient broth (NB) at 28 ± 2 °C for 48 h. A 0.1 mL of culture broth from each NB was separately spread on phytase screening medium [60] and incubated at 28 ± 2 °C for 48 h and then observed for the zone of hydrolysis of phytate around the colonies as an indication of extracellular phytase production. An un-inoculated phytase screening medium served as a control. The efficient phytase producers were selected based on the phytate solubilizing index (PSI). PSI is calculated as follows:

For phytase assay, each isolate was individually grown in Pikovskaya’s (PKV) broth [61] at 28 ± 2 °C for 48–72 h, and then the broth was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. After that, the phytase activity of the supernatant was measured according to the method of Fiske and Subbarao [62]. One unit of phytase was defined as the amount of phytase that liberates 1 µM of inorganic phytate per min at 28 °C at pH 6.5.

4.2.2. Phosphate Solubilization and Organic Acid Production

P solubilization ability of isolates was checked on Pikovskaya’s (PKV) agar [61], and Katznalson’s and Bose (KB) agar [63]. For this purpose, the log phase cultures (5 × 10−5 cell/mL) of each isolate from phytase screening medium were separately grown on PKV and KB agar at 28 °C for 24–48 h, and then observed for the formation of P solubilization around the colonies. Uninoculated PKV and KB agar served as a control. The isolates that formed bigger zones of P solubilization were selected as efficient P solubilizing bacteria (PSB) [61].

For the quantitative estimation of P solubilization, log-phase cultures (5 × 10−5 cells/mL) of each potent PSB were individually grown in each PKV broth at 28 ± 2 °C and 120 rpm for 72 h, and then the broth was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. The inorganic P in the cell-free supernatant was determined according to the method of Fiske and Subbarao [62]. An un-inoculated PKV broth served as a control.

Screening for organic acid production was performed on nutrient agar nutrient agar (NA) supplemented with 1% sugar and 0.05% (w/v) of acid fuchsine (pH indicator dye). Each culture was separately grown on NA at 28 ± 2 °C for 24 h and observed for change in the color of the medium from pale yellow to dark pink [64].

4.2.3. Screening for Nitrogen Fixation and Production of Ammonia, Siderophore and Indole Acetic Acid (IAA)

For screening N2 fixation ability, log-phase cultures (5 × 10−5 cells/mL) of each isolate were grown in the nitrogen-deficient mineral media (NDM) at 28 ± 2 °C for 24 h and observed for the occurrence of bacterial growth. The occurrence of the growth of isolate on NDM was taken as an indication of the N2 fixing ability of the isolate [65]. Uninoculated NDM served as a control.

For the screening of ammonia production, log phase culture (5 × 10−5 cells/mL) of each isolate was grown in the sterile peptone water (PW) medium at 28 ± 2 °C for 24 h, and plates were observed for the occurrence of yellow color as a sign of ammonia production [66]. Uninoculated PW medium served as a control.

For the evaluation of siderophore-producing ability, log phase culture (5 × 10−5 cells/mL) of each isolate was individually grown on Chrome Azurol S (CAS) agar plates at 28 ± 2 °C for 24–48 h. Following the incubation, plates were observed for the formation of yellow-orange halos surrounding the colonies [67]. Uninoculated CAS agar served as a control.

For siderophore production, log phase cultures (5 × 105 cells/mL) of each isolate was separately grown in succinate medium [68] at 28 ± 2 °C for 24–48 h and the cell broth was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. Siderophore content (% siderophore units) from cell supernatant was estimated by CAS shuttle assay [69]. An uninoculated succinate medium was used as a reference.

For the screening of indole acetic acid (IAA) production, each isolate (5 × 105 cells/mL) was grown in NB; supplemented with 0.2% of tryptophan at 28 ± 2 °C for 48 h at 120 rpm and the amount of IAA was measured according to the method of Gordon and Weber [70]. Uninoculated NB served as a reference.

4.3. Screening for Salinity Ameliorating Traits

4.3.1. Production of ACCD and EPS

For the screening and estimation of ACCD activity, log phase cultures (5 × 10−5 cells/mL) of each isolate were grown in minimal medium (MM) containing (g/L), KH2PO4, 2; K2HPO4, 0.5; MgSO4, 0.2; glucose, 0.2, and (NH4)2SO4, 0.19, at 30 °C for 48 h and were then observed for the appearance of growth of the isolate [71]. Uninoculated MM was used as a reference. ACCD activity was estimated as per the Penrose and Glick method [72]. The ACCD activity was defined as the amount of α-keto-butyrate produced per mg of protein per h.

For EPS production, log phase cultures (5 × 105 cells/mL) of each isolate were grown in 5% glucose basal medium at 28 ± 2 °C for 72 h at 120 rpm and the medium was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 20 min. The EPS was precipitated and extracted with cold ethanol, dried at 50 ± 2 °C until a constant weight was obtained for the estimation of EPS [14,73].

4.3.2. Screening for Production of Antioxidant Enzymes

For the screening for superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and reduced glutathione oxidase (GSH) production, each isolate was separately grown in MM at 28 ± 2 °C for 30 h at 120 rpm. After incubation, the broth was centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 10 min. The uniform cell homogenate thus obtained was used for enzyme assay.

For the estimation of SOD activity, 100 µL of cell homogenate was mixed with 100 µL of pyrogallol solution in EDTA buffer (pH 7.0) and the absorbance was measured at 420 nm [74]. One unit of SOD was defined as the amount (IU/mg) of SOD required to inhibit 50% of the autoxidation of pyrogallol.

For measuring the catalase (CAT) activity, 100 µL of cell homogenate was mixed with 100 µL of hydrogen peroxide in phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), and the absorbance of the mixture was measured at 240 nm [75] by using a molar extinction coefficient of hydrogen peroxide (43.6 per M/cm). One unit of catalase was defined as an mM of hydrogen peroxide decomposed/min.

Reduced glutathione (GSH) activity was measured by mixing 100 µL cell homogenate in 100 µL of GSH and the absorbance of the mixture was measured at 240 nm [76]. GSH activity was measured as the reduction in µM of GSH per min.

4.4. Selection of Potent PGPR Isolate

The isolate that produced copious amounts of plant beneficial metabolites and salinity ameliorating traits was selected as a potent PGPR. The potent isolate was identified based on molecular characterization.

4.5. Growth Kinetics and Production of PGP and Salinity Ameliorating Traits in Potent PGPR

To decide the right time required for the optimum growth and production of PGP traits such as phytase, siderophore, IAA, ACCD, and EPS, the log phase culture (5 × 105 cells/mL) of isolate N6 was separately grown in PKV broth, succinate medium Sabouraud’s broth, and MM, respectively, at 28 °C for 48 h. The samples were withdrawn after the 6 h interval and were assayed for the quantification of growth, phytase activity, the amount of siderophore, IAA, ACCD, and EPS [72,77,78,79].

To decide the exact time required for optimum cell growth and the optimum production of antioxidant enzymes, each isolate was separately grown in a basal medium at 28 °C for 48 h. Cell mass was harvested at 6 h intervals and assayed for the estimation of cell growth and SOD, CAT, and GSH activities [74,75,76].

4.6. The Effect of Salt Stress on the Production of PGP and Salinity Ameliorating Traits

The effect of various concentrations (0–200 mM) of salt (NaCl) on the growth and production of PGP and salt-ameliorating traits in the isolate N6 was evaluated by separately growing the log phase culture (5 × 105 cells/mL) of isolate N6 in each nutrient broth (NB) containing varying amounts of NaCl salt (0–200 mM) at 28 °C for 48 h. Following incubation, cell growth was measured in terms of absorbance (optical density (OD) at 620 nm. For the estimation of PGP and salt-ameliorating traits, cell broth was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 20 min, then cell-free supernatant was assayed for the estimation of IAA, siderophore, EPS, activities of phytase, ACCD, SOD, CAT, and GSH as described above.

4.7. Identification of the Potent Isolate-Ribotyping

The phylogenetic identification of isolate N6 was performed by sequencing 16S rRNA genes of the isolate. The genomic DNA of N6 was isolated as per Sambrook and Russell [80]. The 16S rRNA genes were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (Elmer System 9700, Perkin, USA) by using the primers: 27f (5′-AGA GTT TGA TCC TGG CTC AG-3′) and 1492r (3′-ACG GCT ACC TTG TTA CGA CTT-5′) [81]. The 16S rRNA genes were amplified at denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min, 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 1 min, annealing at 55 °C for 1 min and extension at 72 °C for 1 min, final extension at 72 °C for 7 min with a final hold at 20 °C for infinity. The resulting PCR products were purified on agarose gel (1.0%) and sequenced on ABI 3730Xl automated sequencer using a ready reaction kit. The amplified sequences were analyzed by using gapped BLASTn. Phylogenetic analysis was performed using Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 8 [82] and phylogenetic trees were constructed [83]. The 16S rRNA gene sequences of the isolate were submitted to GenBank.

4.8. Statistical Analyses

All the experiments were performed in five replicates and the average values of five replicates. The effect of incubation and salt concentrations of the growth and production of metabolites was analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Turkey Honest Significant Difference (HSD) [84]. All statistical computations were performed on Statistica version 12.0 (Tibco Software, Palo Alto, CA, USA) and graphs were prepared by using origin (Origin Lab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA).

5. Conclusions

The rhizosphere harbors a great and diverse abundance of PGPR. These PGPR produce various metabolites that are involved in plant growth promotion and tolerance to a wide range of biotic and abiotic stresses. Therefore, multifarious PGPR having the potential of growing under salinity conditions, the ability to secrete multiple PGP metabolites, salinity ameliorating traits, and an array of antioxidant enzymes can serve as the best PGPR as well as salinity elevator under field conditions. The potential of wheat rhizosphere K. variicola to grow over the range of high salt concentrations and produce copious amounts of multiple PGP metabolites, salt-ameliorating traits and antioxidant enzymes, make it a potential bioinoculant for plant growth promotion under saline soil. However, field trials under different seasons and different agroclimatic conditions can confirm the multiple potentials of K. variicola.

Author Contributions

S.P.K., methodology; Y.C.A., conceptualization and supervision; R.Z.S., writing—original draft, writing—review and editing of the original draft of the paper; N.I., reviewing and editing of the manuscript, statistical analysis and preparation of graphs; R.A.M., formal analysis; N.L.S., formal analysis, N.K., reviewing and editing of the manuscript; H.A.E.E., review, and editing of the manuscript and funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors extend their appreciation to Universiti Teknologi Malaysia (UTM) for project No. 526 QJ130000.3609.02M43, QJ130000.3609.02M39, and All Cosmos Industries Sdn. Bhd. through project No. R.J130000.7344.4B200.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All the data is included in the manuscript file.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to Universiti Teknologi Malaysia (UTM), Malaysia, and all Cosmos Industries Sdn. Bhd. for providing support to this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Sample Availability

Samples of the compounds are available from the authors.

References

- Basu, A.; Prasad, P.; Das, S.N.; Kalam, S.; Sayyed, R.Z.; Reddy, M.S.; El Enshasy, H. Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) as Green Bioinoculants: Recent Developments, Constraints, and Prospects. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, S.; Sayyed, R. Role of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria and their formulation in biocontrol of plant diseases. In Plant Microbes Symbiosis: Applied Facets; Springer: Singapore, 2015; pp. 337–351. [Google Scholar]

- Fazeli-Nasab, B.; Sayyed, R. Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria and Salinity Stress: A Journey into the Soil. In Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria for Sustainable Stress Management; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Lubna; Asaf, S.; Hamayun, M.; Gul, H.; Lee, I.J.; Hussain, A. Aspergillus niger CSR3 regulates plant endogenous hormones and secondary metabolites by producing gibberellins and indoleacetic acid. J. Plant Interact. 2018, 13, 100–111. [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh, S.S.; Sayyed, R.Z.; Reddy, M.S. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria: An eco-friendly approach for sustainable agroecosystem. In Plant, Soil and Microbes; Springer: Singapore, 2016; pp. 181–201. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A.; Sayyed, R.; Seifi, S. Rhizobacteria: Legendary Soil Guards in Abiotic Stress Management. In Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria for Sustainable Stress Management; Reddy, M.S., Sayyed, R.Z., Arora, N.K., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 327–343. [Google Scholar]

- Jabborova, D.; Wirth, S.; Kannepalli, A.; Narimanov, A.; Desouky, S.; Davranov, K.; Sayyed, R.; El Enshasy, H.; Malek, R.A.; Syed, A. Co-Inoculation of rhizobacteria and biochar application improves growth and nutrients in soybean and enriches soil nutrients and enzymes. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, S.; Patel, P.; Patel, S.; Nikam, S.; Rane, T.; Sayyed, R. Production of biocontrol traits by banana field fluorescent Pseudomonads and comparison with chemical fungicide. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 2014, 52, 917–920. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sayyed, R.; Seifi, S.; Patel, P.; Shaikh, S.; Jadhav, H.; El Enshasy, H. Siderophore production in groundnut rhizosphere isolate, Achromobacter sp. RZS2 influenced by physicochemical factors and metal ions. Env. Sustain. 2019, 2, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandya, N.; Desai, P.; Jadhav, H.; Sayyed, R. Plant growth-promoting potential of Aspergillus sp. NPF7, isolated from wheat rhizosphere in South Gujarat, India. Environ. Sustain. 2018, 1, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabborova, D.; Annapurna, K.; Fayzullaeva, M.; Sulaymonov, K.; Kadirova, D.; Jabbarov, Z.; Sayyed, R. Isolation and characterization of endophytic bacteria from ginger (Zingiber officinale Rosc.). Ann. Phytomed. 2020, 9, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, S.; Wani, S.; Sayyed, R.; Thakur, R.; Gulati, A. Production, purification and kinetics of chitinase of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia isolated from rhizospheric soil. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 2018, 56, 274–278. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, I.; Awan, S.A.; Ikram, R.; Rizwan, M.; Akhtar, N.; Yasmin, H.; Sayyed, R.Z.; Ali, S.; Ilyas, N. Effect of 24-Epibrassinolide on plant growth, antioxidants defense system and endogenous hormones in two wheat varieties under drought stress. Physiol. Plant. 2020, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayyed, R.; Jamadar, D.; Patel, P. Production of exo-polysaccharide by Rhizobium sp. Ind. J. Microbiol. 2011, 51, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayyed, R.; Patel, P.; Shaikh, S. Plant growth promotion and root colonization by EPS producing Enterobacter sp. RZS5 under heavy metal contaminated soil. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 2015, 53, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sagar, A.; Shukla, P.; Sayyed, R.; Ramteke, P. Stimulation of Seed Germination and Growth Parameters of Rice var. Sahbhagi by Enterobacter cloacae in the presence of ammonium sulfate as a substitute of ACC. In Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR): Prospects for Sustainable Agriculture; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 117–124. [Google Scholar]

- Sagar, A.; Riyazuddin, R.; Shukla, P.; Ramteke, P.; Sayyed, R. Heavy metal stress tolerance in Enterobacter sp. PR14 is mediated by plasmid. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 2020, 58, 115–121. [Google Scholar]

- Sagar, A.; Sayyed, R.; Ramteke, P.; Sharma, S.; Marraiki, N.; Elgorban, A.M.; Syed, A. ACC deaminase and antioxidant enzymes producing halophilic Enterobacter sp. PR14 promotes the growth of rice and millets under salinity stress. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2020, 26, 1847–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, N.; Mumtaz, K.; Akhtar, N.; Yasmin, H.; Sayyed, R.; Khan, W.; Enshasy, H.A.E.; Dailin, D.J.; Elsayed, E.A.; Ali, Z. Exopolysaccharides Producing Bacteria for the Amelioration of Drought Stress in Wheat. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.B.; Sayyed, R.Z.; Trivedi, M.H.; Gobi, T.A. Phosphate solubilizing microbes: Sustainable approach for managing phosphorus deficiency in agricultural soils. SpringerPlus 2013, 2, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.B.; Sayyed, R.Z.; Sonawane, M.; Trivedi, M.H.; Thivakaran, G.A. Neurospora sp. SR8, a novel phosphate solubilizer from rhizosphere soil of Sorghum in Kachchh, Gujarat, India. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 2016, 54, 644–649. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Suriani, N.L.; Suprapta, D.N.; Nazir, N.; Parwanayoni, N.M.S.; Darmadi, A.A.K.; Dewi, D.A.; Sudatri, N.W.; Fudholi, A.; Sayyed, R.; Syed, A. A Mixture of Piper Leaves Extracts and Rhizobacteria for Sustainable Plant Growth Promotion and Bio-Control of Blast Pathogen of Organic Bali Rice. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dailin, D.J.; Hanapi, S.Z.; Elsayed, E.A.; Sukmawati, D.; Azelee, N.I.W.; Eyahmalay, J.; Siwapiragam, V.; El Enshasy, H. Fungal Phytases: Biotechnological applications in food and feed industries. In Recent Advancements in White Biotechnology through Fungi; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 65–99. [Google Scholar]

- El Enshasy, H.; Dailin, D.J.; Abd Manas, N.H.; Azlee, N.I.W.; Eyahmalay, J.; Yahaya, S.A.; Abd Malek, R.; Siwapiragam, V.; Siwapiragam, D. Current and future applications of phytases in poultry industry: A critical review. J. Adv. Vet. Bio Sci. Techniq. 2018, 3, 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Barrios-Camacho, H.; Aguilar-Vera, A.; Beltran-Rojel, M.; Baguilar-Vera, E.; Duran-Bedolla, J.; Rodriguez-Medina, N.; Lozano-Aguirre, L.; Perez-Carrascal, O.M.; Rojas, J.; Garza-Ramos, U. Molecular epidemiology of Klebsiella variicola obtained from different sources. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Balaban, N.P.; Suleimanova, A.D.; Valeeva, L.R.; Chastukhina, I.B.; Rudakova, N.L.; Sharipova, M.R.; Shakirov, E.V. Microbial phytases and phytate: Exploring opportunities for sustainable phosphorus management in agriculture. Amer. J. Mol. Biol. 2016, 7, 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Singh, P.; Jorquera, M.A.; Sangwan, P.; Kumar, P.; Verma, A.K.; Agrawal, S. Isolation of phytase-producing bacteria from Himalayan soils and their effect on growth and phosphorus uptake of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea). World. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 29, 1361–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.K.; Joshi, D.K.; Gupta, R.K. Isolation of phytase producing bacteria and optimization of phytase production parameters. Jund. J. Microbiol. 2013, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Li, A.; Chen, J.; Su, Y.; Li, Y.; Ma, S. Isolation of a phytase-producing bacterial strain from agricultural soil and its characterization and application as an effective eco-friendly phosphate solubilizing bioinoculant. Comm. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2018, 49, 984–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblueth, M.; Martínez, L.; Silva, J.; Martínez-Romero, E. Klebsiella variicola, a novel species with clinical and plant-associated isolates. System. Appl. Microbiol. 2004, 27, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, G.; Shah, R.; Joshi, B.; Patel, P. Klebsiella pneumoniae VRE36 as a PGPR isolated from Saccharum officinarum cultivar Co99004. J. Appl. Biol. Biotech. 2017, 5, 047–052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlova, A.; Leontieva, M.; Smirnova, T.; Kolomeitseva, G.; Netrusov, A.; Tsavkelova, E. Colonization strategy of the endophytic plant growth-promoting strains of Pseudomonas fluorescens and Klebsiella oxytoca on the seeds, seedlings, and roots of the epiphytic orchid, Dendrobium nobile Lindl. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2017, 123, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazumdar, D.; Saha, S.P.; Ghosh, S. Klebsiella pneumoniae rs26 as a potent PGPR isolated from chickpea (Cicer arietinum) rhizosphere. Pharma. Innov. J. 2018, 7, 56–62. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S.; Trivedi, M.; Sayyed, R.; Thivakaran, G. Status of soil phosphorus in context with phosphate solubilizing microorganisms in different agricultural amendments in Kachchh, Gujarat, Western India. Ann. Res. Rev. Biol. 2014, 2901–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, P.; Choudhury, A.; Chakraborty, S.; Ray, D.P.; Deb, S.; Patra, P.S.; Mahato, B.; Paramanik, B.; Singh, A.K.; Chauhan, R.K. Phosphorus Solubilizing Bacteria from Tea Soils and their Phosphate Solubilizing Abilities. Int. J. Biores. Sci. 2017, 4, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahemad, M.; Khan, M.S. Effects of insecticides on plant-growth-promoting activities of phosphate solubilizing rhizobacterium Klebsiella sp. strain PS19. Pesti. Biochem. Physiol. 2011, 100, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuan, K.B.; Othman, R.; Abdul Rahim, K.; Shamsuddin, Z.H. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria inoculation to enhance vegetative growth, nitrogen fixation, and nitrogen remobilization of maize under greenhouse conditions. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0152478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sachdev, D.P.; Chaudhari, H.G.; Kasture, V.M.; Dhavale, D.D.; Chopade, B.A. Isolation and characterization of indole acetic acid (IAA) producing Klebsiella pneumoniae strains from the rhizosphere of wheat (Triticum aestivum) and their effect on plant growth. Ind. J. Exp. Biol. 2009, 47, 993–1000. [Google Scholar]

- Govindarajan, M.; Kwon, S.-W.; Weon, H.-Y. Isolation, molecular characterization, and growth-promoting activities of endophytic sugarcane diazotroph Klebsiella sp. GR9. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 23, 997–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haahtela, K.; Ronkko, R.; Laakso, T.; Williams, P.H.; Korhonen, T.K. Root-associated Enterobacter and Klebsiella in Poa pratensis: Characterization of an iron-scavenging system and a substance stimulating root hair production. Mol. Plant-Microbe. Interact. 1990, 3, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghannem, S.A.; Farag, M.M.; Shehab, A.; Azab, M.S. Media optimization for exopolysaccharide producing Klebsiella oxytoca KY498625 under varying cultural conditions. Int. J. Adv. Res. Biol. Sci. 2017, 4, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AMAO, J.A.; Omojasola, P.F.; Barooah, M. Isolation, and characterization of some exopolysaccharide producing bacteria from cassava peel heaps. Sci. Afr. 2019, 4, e00093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivakumar, T.; Shankar, T.; Thangapandian, V.; Mahendran, S. Media optimization for exopolysaccharide producing Klebsiella pneumoniae KU215681 under varying cultural conditions. Int. J. Biochem. Biophys. 2016, 4, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Castillo, M.; Uribelarrea, J. Improved process for exopolysaccharide production by Klebsiella pneumoniae sp. pneumoniae by a fed-batch strategy. Biotechnol. Lett. 2004, 26, 1301–1306. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Cui, N.; Qu, F.; Huang, X.; Yang, H.; Nie, S.; Zha, X.; Cui, S.W.; Nishinari, K.; Phillips, G.O. Novel nano-particulated exopolysaccharide produced by Klebsiella sp. PHRC1. 001. Carbon Poly. 2017, 171, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariyono, D. The effect of planting hole size and manure on vegetative growth of golden teak (Tectona grandis L.). J. Degrad. Min. Lands Manag. 2018, 5, 1293–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.; Shaikh, S.; Sayyed, R. Dynamism of PGPR in bioremediation and plant growth promotion in heavy metal contaminated soil. Ind. J. Exp. Biol. 2016, 54, 286–290. [Google Scholar]

- Dlamini, A.M.; Peiris, P.S.; Bavor, J.H.; Kailasapathy, K. Rheological characteristics of an exopolysaccharide produced by a strain of Klebsiella oxytoca. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2009, 107, 272–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, W.V.; Kennedy, S.P.; Mahairas, G.G.; Berquist, B.; Pan, M.; Shukla, H.D.; Lasky, S.R.; Baliga, N.S.; Thorsson, V.; Sbrogna, J. Genome sequence of Halobacterium species NRC-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 12176–12181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.P.; Jha, P.; Jha, P.N. The plant-growth-promoting bacterium Klebsiella sp. SBP-8 confers induced systemic tolerance in wheat (Triticum aestivum) under salt stress. J. Plant Physiol. 2015, 184, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, M.; Kaushik, A.; Rani, N.; Kaushik, C. Effect of cyanobacterial exopolysaccharides on salt stress alleviation and seed germination. J. Environ. Biol. 2010, 31, 701–704. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Othman, N.Z.; Elsayed, E.A.; Malek, R.A.; Ramli, S.; Masri, H.J.; Sarmidi, M.R.; Aziz, R.; Wadaan, M.A.; El Enshasy, H.A. Aeration rate effect on the growth kinetics, phytase production and plasmid stability of recombinant Escherichia coli BL21(DE3). J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 8, 2721–2728. [Google Scholar]

- Reshma, P.; Naik, M.; Aiyaz, M.; Niranjana, S.; Chennappa, G.; Shaikh, S.; Sayyed, R. Induced systemic resistance by 2, 4-diacetylphloroglucinol positive fluorescent Pseudomonas strains against rice sheath blight. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 2018, 56, 207–212. [Google Scholar]

- Ahemad, M.; Khan, M.S. Plant growth-promoting activities of phosphate solubilizing Enterobacter asburiae as influenced by fungicides. Eurasian J. Biosci. 2010, 4, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, U.P.; Kumar, A. Characterization and optimization of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate deaminase (ACCD) activity in different rhizospheric PGPR along with Microbacterium sp. strain ECI-12A. Int. J. Appl. Sci. Biotechnol. 2013, 1, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuña, J.J.; Campos, M.; de la Luz Mora, M.; Jaisi, D.P.; Jorquera, M.A. ACCD-producing rhizobacteria from an Andean altiplano native plant (Parastrephia quadrangularis) and their potential to alleviate salt stress in wheat seedlings. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2019, 136, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapre, S.; Gontia-Mishra, I.; Tiwari, S. Klebsiella sp. confers enhanced tolerance to salinity and plant growth promotion in oat seedlings (Avena sativa). Microbiol. Res. 2018, 206, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Medina, N.; Barrios-Camacho, H.; Duran-Bedolla, J.; Garza-Ramos, U. Klebsiella variicola: An emerging pathogen in humans. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2019, 8, 973–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalam, S.; Basu, A.; Ahmad, I.; Sayyed, R.; El Enshasy, H.; Dailin, D.J.; Suriani, N. Recent understanding of soil acidobacteria and their ecological significance: A critical review. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 580024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villamizar, G.A.C.; Funkner, K.; Nacke, H.; Foerster, K.; Daniel, R. Functional metagenomics unwraps a new catalytic domain associated to phytase activity: The Metallo-β-lactamase superfamily domain, discovery and functional characterization of novel soil-metagenome-derived phosphatases. mBio 2019, 10, e01918–e01966. [Google Scholar]

- Pikovskaya, R. Mobilization of phosphorus in soil in connection with vital activity of some microbial species. Mikrobiologiya 1948, 17, 362–370. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske, C.H.; Subbarow, Y. The colorimetric determination of phosphorus. J. Biol. Chem. 1925, 66, 375–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katznelson, H.; Bose, B. Metabolic activity and phosphate-dissolving capability of bacterial isolates from wheat roots, rhizosphere, and non-rhizosphere soil. Can. J. Microbiol. 1959, 5, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashid, M.; Khalil, S.; Ayub, N.; Alam, S.; Latif, F. Organic acids production and phosphate solubilization by phosphate solubilizing microorganisms (PSM) under in vitro conditions. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 2004, 7, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremner, J. Determination of nitrogen in soil by the Kjeldahl method. J. Agric. Sci. 1960, 55, 11–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, J.; Thakur, D. Evaluation of multifarious plant growth-promoting traits, antagonistic potential, and phylogenetic affiliation of rhizobacteria associated with commercial tea plants grown in Darjeeling, India. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, P.; Shaikh, S.; Sayyed, R. Modified chrome azurol S method for detection and estimation of siderophores having an affinity for metal ions other than iron. Environ. Sustain. 2018, 1, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.M.; Abdallah, M. The fluorescent pigment of Pseudomonas fluorescens: Biosynthesis, purification, and physicochemical properties. Microbiology 1978, 107, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, S.M. Detection, isolation, and characterization of siderophores. Methods Enzymol. 1994, 35, 329–344. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, S.A.; Weber, R.P. Colorimetric estimation of indoleacetic acid. Plant Physiol. 1951, 26, 192–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safronova, V.I.; Stepanok, V.V.; Engqvist, G.L.; Alekseyev, Y.V.; Belimov, A.A. root-associated bacteria containing 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate deaminase improve growth and nutrient uptake by pea genotypes cultivated in cadmium supplemented soil. Biol. Fert. Soils. 2006, 42, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penrose, D.M.; Glick, B.R. Methods for isolating and characterizing ACC deaminase-containing plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Physiol. Planta. 2003, 118, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.A.; Anandapandian, K.T.K.; Parthiban, K. Production and characterization of exopolysaccharides (EPS) from biofilm-forming marine bacterium. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2011, 54, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marklund, S. Gudrun Marklund. Involvement of the superoxide anion radical in the autoxidation of pyrogallol and a convenient assay for superoxide dismutase. Euro. J. Biochem. 1974, 47, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beers, R.F.; Sizer, I.W. A spectrophotometric method for measuring the breakdown of hydrogen peroxide by catalase. J. Biol. Chem. 1952, 195, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nürnberg, D.; Danon, A. Determination of reduced and total glutathione content in extremophilic microalgae Galdieria phlegrea. Plant. Cell. Physiol. 2016, 7, e2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nautiyal, C.S. An efficient microbiological growth medium for screening phosphate solubilizing microorganisms. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1999, 170, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bric, J.M.; Bostock, R.M.; Silverstone, S.E. Rapid in situ assay for indoleacetic acid production by bacteria immobilized on a nitrocellulose membrane. Appl. Env. Microbiol. 1991, 57, 535–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damodaran, T.; Sah, V.; Rai, R.; Sharma, D.; Mishra, V.; Jha, S.; Kannan, R. Isolation of salt-tolerant endophytic and rhizospheric bacteria by natural selection and screening for promising plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) and growth vigor in tomato under sodic environment. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2013, 7, 5082–5089. [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook, J.; Russell, D.W. The Condensed Protocols from Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory MANUAL; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Cold Spring Harbor: New York, NY, USA, 2001; p. 800. [Google Scholar]

- Pediyar, V.; Adam, K.A.; Badri, N.N.; Patole, M.; Shouche, Y.S. Aeromonas culicicola sp. nov., from the midgut of Culexquinque fasciatus. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2002, 52, 1723–1728. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J.D.; Toby, J.G.; Frederic, P.; François, J.; Desmond, G.H. The CLUSTAL × windows interface: Flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 25, 4876–4882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, K.N.M.; Kumar, S. Prospects for inferring very large phylogenies by using the neighbor-joining method. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 11030–11035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, R.E. Continuous distribution: Tests of significance, In Introductory Statistics for Biology, 2nd ed.; Arnold, B.S., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: London, UK, 1979; pp. 18–42. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).