Aurora Kinase B Inhibition: A Potential Therapeutic Strategy for Cancer

Abstract

:1. Introduction

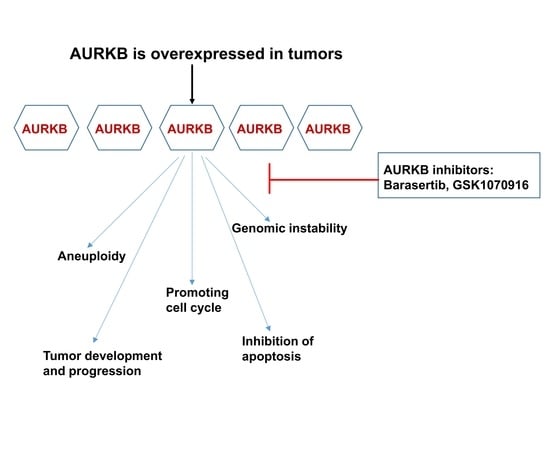

2. Structure and Function of AURKB

3. Deregulation of AURKB in Cancer

4. Regulation of AURKB Function in Cancer

4.1. AURKB Regulation by Myc and Vice-Versa

4.2. Bcr-Abl Positively Regulates AURKB

4.3. AURKB Crosstalks with BRCA1 and BRCA2

4.4. RASSF7 Activates AURKB

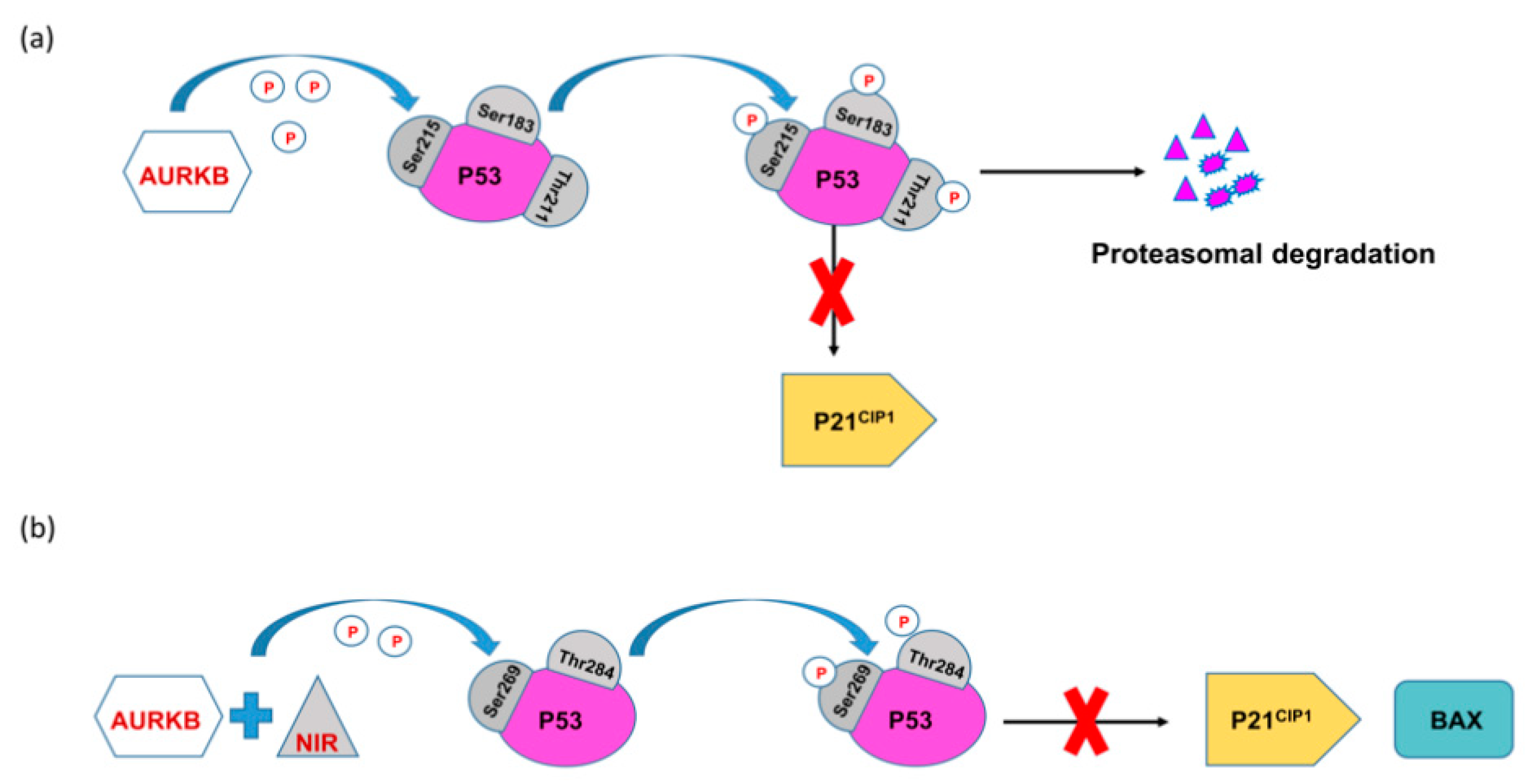

4.5. p53 Dependent Tumor Suppressor FBXW7 Negatively Regulates AURKB

4.6. AURKB Regulation by MDM2

4.7. AURKB Is a Downstream Target of Cyclin K in Prostate Cancer

5. Targeting AURKB in Cancer

5.1. AURKB Specific Inhibitors

5.1.1. Hesperadin

5.1.2. Barasertib

5.1.3. SP-96

5.2. Pan Aurora Kinase Inhibitors in Clinical Trials

5.2.1. GSK1070916

5.2.2. Danusertib (PHA-739358)

5.2.3. AT9283

5.2.4. AMG900

5.2.5. CYC116

5.2.6. Other Pan-AURK Inhibitors

6. Therapy-Related Drug Resistance and AURKB

7. Combination Therapy with AURKB Inhibition

8. Computational Chemistry Approaches to Develop Promising Inhibitors for AURKB

9. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nigg, E.A. Mitotic kinases as regulators of cell division and its checkpoints. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001, 2, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieterich, K.; Soto Rifo, R.; Karen Faure, A.; Hennebicq, S.; Amar, B.B.; Zahi, M.; Perrin, J.; Martinez, D.; Sèle, B.; Jouk, P.S.; et al. Homozygous mutation of AURKC yields large-headed polyploid spermatozoa and causes male infertility. Nat. Genet. 2007, 39, 661–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharif, B.; Na, J.; Lykke-Hartmann, K.; McLaughlin, S.H.; Laue, E.; Glover, D.M.; Zernicka-Goetz, M. The chromosome passenger complex is required for fidelity of chromosome transmission and cytokinesis in meiosis of mouse oocytes. J. Cell Sci. 2010, 123, 4292–4300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Carmena, M.; Earnshaw, W.C. The cellular geography of Aurora kinases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003, 4, 842–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Deng, Z.; Fu, J.; Xu, C.; Xin, G.; Wu, Z.; Luo, J.; Wang, G.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, B.; et al. Spatial compartmentalization specializes the function of Aurora A and Aurora B. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 17546–17558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marumoto, T.; Zhang, D.; Saya, H. Aurora-A—A guardian of poles. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2005, 5, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galetta, D.; Cortes-Dericks, L. Promising therapy in lung cancer: Spotlight on aurora kinases. Cancers 2020, 12, 3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, A.; Gao, K.; Chu, L.; Zhang, R.; Yang, J.; Zheng, J. Aurora kinases: Novel therapy targets in cancers. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 23937–23954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Crosio, C.; Fimia, G.M.; Loury, R.; Kimura, M.; Okano, Y.; Zhou, H.; Sen, S.; Allis, C.D.; Sassone-corsi, P. Mitotic Phosphorylation of Histone H3: Spatio-Temporal Regulation by Mammalian Aurora Kinases. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002, 22, 874–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ota, T.; Suto, S.; Katayama, H.; Han, Z.B.; Suzuki, F.; Maeda, M.; Tanino, M.; Terada, Y.; Tatsuka, M. Increased mitotic phosphorylation of histone H3 attributable to AIM-1/aurora-B overexpression contributes to chromosome number instability. Cancer Res. 2002, 62, 5168–5177. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kanda, A.; Kawai, H.; Suto, S.; Kitajima, S.; Sato, S.; Takata, T.; Tatsuka, M. Aurora-B/AIM-1 kinase activity is involved in Ras-mediated cell transformation. Oncogene 2005, 24, 7266–7272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bolanos-Garcia, V.M. Aurora kinases. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2005, 37, 1572–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheetham, G.M.T.; Knegtel, R.M.A.; Coll, J.T.; Renwick, S.B.; Swenson, L.; Weber, P.; Lippke, J.A.; Austen, D.A. Crystal structure of Aurora-2, an oncogenic serine/threonine kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 42419–42422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Willems, E.; Dedobbeleer, M.; Digregorio, M.; Lombard, A.; Lumapat, P.N.; Rogister, B. The functional diversity of Aurora kinases: A comprehensive review. Cell Div. 2018, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nguyen, H.G.; Chinnappan, D.; Urano, T.; Ravid, K. Mechanism of Aurora-B Degradation and Its Dependency on Intact KEN and A-Boxes: Identification of an Aneuploidy-Promoting Property. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005, 25, 4977–4992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Portella, G.; Passaro, C.; Chieffi, P. Aurora B: A New Prognostic Marker and Therapeutic Target in Cancer. Curr. Med. Chem. 2011, 18, 482–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vader, G.; Medema, R.H.; Lens, S.M.A. The chromosomal passenger complex: Guiding Aurora-B through mitosis. J. Cell Biol. 2006, 173, 833–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gassmann, R.; Carvalho, A.; Henzing, A.J.; Ruchaud, S.; Hudson, D.F.; Honda, R.; Nigg, E.A.; Gerloff, D.L.; Earnshaw, W.C. Borealin: A novel chromosomal passenger required for stability of the bipolar mitotic spindle. J. Cell Biol. 2004, 166, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zeitlin, S.G.; Shelby, R.D.; Sullivan, K.F. CENP-A is phosphorylated by Aurora B kinase and plays an unexpected role in completion of cytokinesis. J. Cell Biol. 2001, 155, 1147–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broad, A.J.; DeLuca, K.F.; DeLuca, J.G. Aurora B kinase is recruited to multiple discrete kinetochore and centromere regions in human cells. J. Cell Biol. 2020, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Q.; Chen, Q.; Yan, H.; Zhang, M.; Liang, C.; Xiang, X.; Pan, X.; Wang, F. Aurora B kinase activity– dependent and –independent functions of the chromosomal passenger complex in regulating sister chromatid cohesion. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 2021–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Uehara, R.; Tsukada, Y.; Kamasaki, T.; Poser, I.; Yoda, K.; Gerlich, D.W.; Goshima, G. Aurora B and Kif2A control microtubule length for assembly of a functional central spindle during anaphase. J. Cell Biol. 2013, 202, 623–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schumacher, J.M.; Golden, A.; Donovan, P.J. AIR-2: An Aurora/Ipl1-related protein kinase associated with chromosomes and midbody microtubules is required for polar body extrusion and cytokinesis in Caenorhabditis elegans embryos. J. Cell Biol. 1998, 143, 1635–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Giet, R.; Glover, D.M. Drosophila aurora B kinase is required for histone H3 phosphorylation and condensin recruitment during chromosome condensation and to organize the central spindle during cytokinesis. J. Cell Biol. 2001, 152, 669–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Adams, R.R.; Maiato, H.; Earnshaw, W.C.; Carmena, M. Essential roles of Drosophila inner centromere protein (INCENP) and aurora B in histone H3 phosphorylation, metaphase chromosome alignment, kinetochore disjunction, and chromosome segregation. J. Cell Biol. 2001, 153, 865–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, H.G.; Makitalo, M.; Yang, D.; Chinnappan, D.; St.Hilaire, C.; Ravid, K. Deregulated Aurora-B induced tetraploidy promotes tumorigenesis. FASEB J. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chieffi, P.; Troncone, G.; Caleo, A.; Libertini, S.; Linardopoulos, S.; Tramontano, D.; Portella, G. Aurora B expression in normal testis and seminomas. J. Endocrinol. 2004, 181, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sorrentino, R.; Libertini, S.; Pallante, P.L.; Troncone, G.; Palombini, L.; Bavetsias, V.; Spalletti-Cernia, D.; Laccetti, P.; Linardopoulos, S.; Chieffi, P.; et al. Aurora B overexpression associates with the thyroid carcinoma undifferentiated phenotype and is required for thyroid carcinoma cell proliferation. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 90, 928–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.L.; Bowers, N.L.; Betticher, D.C.; Gautschi, O.; Ratschiller, D.; Hoban, P.R.; Booton, R.; Santibáñez-Koref, M.F.; Heighway, J. Overexpression of aurora B kinase (AURKB) in primary non-small cell lung carcinoma is frequent, generally driven from one allele, and correlates with the level of genetic instability. Br. J. Cancer 2005, 93, 719–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vischioni, B.; Oudejans, J.J.; Vos, W.; Rodriguez, J.A.; Giaccone, G. Frequent overexpression of aurora B kinase, a novel drug target, in non-small cell lung carcinoma patients. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2006, 5, 2905–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Al-Khafaji, A.S.K.; Davies, M.P.A.; Risk, J.M.; Marcus, M.W.; Koffa, M.; Gosney, J.R.; Shaw, R.J.; Field, J.K.; Liloglou, T. Aurora B expression modulates paclitaxel response in non-small cell lung cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2017, 116, 592–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pohl, A.; Azuma, M.; Zhang, W.; Yang, D.; Ning, Y.; Winder, T.; Danenberg, K.; Lenz, H.J. Pharmacogenetic profiling of Aurora kinase B is associated with overall survival in metastatic colorectal cancer. Pharm. J. 2011, 11, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, D.; Huang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Weng, J.; Zhang, S.; Gu, W. Relation of AURKB over-expression to low survival rate in BCRA and reversine-modulated aurora B kinase in breast cancer cell lines. Cancer Cell Int. 2019, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.F.; Navaratne, K.; Prayson, R.A.; Weil, R.J. Aurora B expression correlates with aggressive behaviour in glioblastoma multiforme. J. Clin. Pathol. 2007, 60, 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nie, M.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Z.; Li, X.; Deng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, D.; Li, Q.; Zeng, X.; Ju, J.; et al. AURKB promotes gastric cancer progression via activation of CCND1 expression. Aging 2020, 12, 1304–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, G.; Ogawa, I.; Kudo, Y.; Miyauchi, M.; Siriwardena, B.S.M.S.; Shimamoto, F.; Tatsuka, M.; Takata, T. Aurora-B expression and its correlation with cell proliferation and metastasis in oral cancer. Virchows Arch. 2007, 450, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pannone, G.; Hindi, S.A.H.; Santoro, A.; Sanguedolce, F.; Rubini, C.; Cincione, R.I.; De Maria, S.; Tortorella, S.; Rocchetti, R.; Cagiano, S.; et al. Aurora B expression as a prognostic indicator and possibile therapeutic target in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2011, 24, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, M.; Liu, H.; Zhao, Q.; Han, S.; Zhou, L.; Liu, W.; Li, W.; Gao, F. Targeting Aurora B kinase with Tanshinone IIA suppresses tumor growth and overcomes radioresistance. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chieffi, P.; Cozzolino, L.; Kisslinger, A.; Libertini, S.; Staibano, S.; Mansueto, G.; De Rosa, G.; Villacci, A.; Vitale, M.; Linardopoulos, S.; et al. Aurora B expression directly correlates with prostate cancer malignancy and influence prostate cell proliferation. Prostate 2006, 66, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Z.Z.; Jeng, Y.M.; Hu, F.C.; Pan, H.W.; Tsao, H.W.; Lai, P.L.; Lee, P.H.; Cheng, A.L.; Hsu, H.C. Significance of Aurora B overexpression in hepatocellular carcinoma. Aurora B Overexpression in HCC. BMC Cancer 2010, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hartsink-Segers, S.A.; Zwaan, C.M.; Exalto, C.; Luijendijk, M.W.J.; Calvert, V.S.; Petricoin, E.F.; Evans, W.E.; Reinhardt, D.; De Haas, V.; Hedtjärn, M.; et al. Aurora kinases in childhood acute leukemia: The promise of aurora B as therapeutic target. Leukemia 2013, 27, 560–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Borah, N.A.; Sradhanjali, S.; Barik, M.R.; Jha, A.; Tripathy, D.; Kaliki, S.; Rath, S.; Raghav, S.K.; Patnaik, S.; Mittal, R.; et al. Aurora Kinase B Expression, Its Regulation and Therapeutic Targeting in Human Retinoblastoma. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2021, 62, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Z.; Li, C.; Kang, B.; Gao, G.; Li, C.; Zhang, Z. GEPIA: A web server for cancer and normal gene expression profiling and interactive analyses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, W98–W102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Den Hollander, J.; Rimpi, S.; Doherty, J.R.; Rudelius, M.; Buck, A.; Hoellein, A.; Kremer, M.; Graf, N.; Scheerer, M.; Hall, M.A.; et al. Aurora kinases A and B are up-regulated by Myc and are essential for maintenance of the malignant state. Blood 2010, 116, 1498–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bogen, D.; Wei, J.S.; Azorsa, D.O.; Ormanoglu, P.; Guha, R.; Keller, J.M.; Griner, L.A.M.; Song, Y.K.; Liao, H.; Mendoza, A.; et al. Aurora B kinase is a potent and selective target in MYCN-driven neuroblastoma. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 35247–35262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jiang, J.; Wang, J.; Yue, M.; Cai, X.; Wang, T.; Wu, C.; Su, H.; Wang, Y.; Han, M.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Direct Phosphorylation and Stabilization of MYC by Aurora B Kinase Promote T-cell Leukemogenesis. Cancer Cell 2020, 37, 200–215.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sradhanjali, S.; Tripathy, D.; Rath, S.; Mittal, R.; Reddy, M.M. Overexpression of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 in retinoblastoma: A potential therapeutic opportunity for targeting vitreous seeds and hypoxic regions. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sradhanjali, S.; Reddy, M.M. Inhibition of Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Kinase as a Therapeutic Strategy against Cancer. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2018, 18, 444–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Ikezoe, T.; Nishioka, C.; Udaka, K.; Yokoyama, A. Bcr-Abl activates AURKA and AURKB in chronic myeloid leukemia cells via AKT signaling. Int. J. Cancer 2014, 134, 1183–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Qi, Z.; Yin, S.; Zhang, N.; Liu, Y.; Liu, M.; Meng, J.; Zang, R.; Zhang, Z.; et al. The negative interplay between Aurora A/B and BRCA1/2 controls cancer cell growth and tumorigenesis via distinct regulation of cell cycle progression, cytokinesis, and tetraploidy. Mol. Cancer 2014, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Volodko, N.; Gordon, M.; Salla, M.; Ghazaleh, H.A.; Baksh, S. RASSF tumor suppressor gene family: Biological functions and regulation. FEBS Lett. 2014, 588, 2671–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Recino, A.; Sherwood, V.; Flaxman, A.; Cooper, W.N.; Latif, F.; Ward, A.; Chalmers, A.D. Human RASSF7 regulates the microtubule cytoskeleton and is required for spindle formation, Aurora B activation and chromosomal congression during mitosis. Biochem. J. 2010, 430, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Akhoondi, S.; Sun, D.; Von Der Lehr, N.; Apostolidou, S.; Klotz, K.; Maljukova, A.; Cepeda, D.; Fiegl, H.; Dofou, D.; Marth, C.; et al. FBXW7/hCDC4 is a general tumor suppressor in human cancer. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 9006–9012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sailo, B.L.; Banik, K.; Girisa, S.; Bordoloi, D.; Fan, L.; Halim, C.E.; Wang, H.; Kumar, A.P.; Zheng, D.; Mao, X.; et al. FBXW7 in cancer: What has been unraveled thus far? Cancers 2019, 11, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, Z.; Sun, Y.; Chen, X.; Squires, J.; Nowroozizadeh, B.; Liang, C.; Huang, J. P53 mutation directs AURKA overexpression via miR-25 and FBXW7 in prostatic small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. Mol. Cancer Res. 2015, 13, 584–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Teng, C.L.; Hsieh, Y.C.; Phan, L.; Shin, J.; Gully, C.; Velazquez-Torres, G.; Skerl, S.; Yeung, S.C.J.; Hsu, S.L.; Lee, M.H. FBXW7 is involved in Aurora B degradation. Cell Cycle 2012, 11, 4059–4068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gully, C.P.; Velazquez-Torres, G.; Shin, J.H.; Fuentes-Mattei, E.; Wang, E.; Carlock, C.; Chen, J.; Rothenberg, D.; Adams, H.P.; Choi, H.H.; et al. Aurora B kinase phosphorylates and instigates degradation of p53. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 1513–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, L.; Ma, C.A.; Zhao, Y.; Jain, A. Aurora B interacts with NIR-p53, leading to p53 phosphorylation in its DNA-binding domain and subsequent functional suppression. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 2236–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jha, H.C.; Yang, K.; El-Naccache, D.W.; Sun, Z.; Robertson, E.S. EBNA3C regulates p53 through induction of Aurora kinase B. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 5788–5803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kanagasabai, T.; Venkatesan, T.; Natarajan, U.; Alobid, S.; Alhazzani, K.; Algahtani, M.; Rathinavelu, A. Regulation of cell cycle by MDM2 in prostate cancer cells through Aurora Kinase-B and p21WAF1(/CIP1) mediated pathways. Cell. Signal. 2020, 66, 109435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schecher, S.; Walter, B.; Falkenstein, M.; Macher-Goeppinger, S.; Stenzel, P.; Krümpelmann, K.; Hadaschik, B.; Perner, S.; Kristiansen, G.; Duensing, S.; et al. Cyclin K dependent regulation of Aurora B affects apoptosis and proliferation by induction of mitotic catastrophe in prostate cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 141, 1643–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groot, C.O.D.; Hsia, J.E.; Anzola, J.V.; Motamedi, A. A Cell Biologist’s Field Guide to Aurora Kinase Inhibitors. Front. Oncol. 2015, 5, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hauf, S.; Cole, R.W.; LaTerra, S.; Zimmer, C.; Schnapp, G.; Walter, R.; Heckel, A.; Van Meel, J.; Rieder, C.L.; Peters, J.M. The small molecule Hesperadin reveals a role for Aurora B in correcting kinetochore-microtubule attachment and in maintaining the spindle assembly checkpoint. J. Cell Biol. 2003, 161, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sessa, F.; Mapelli, M.; Ciferri, C.; Tarricone, C.; Areces, L.B.; Schneider, T.R.; Stukenberg, P.T.; Musacchio, A. Mechanism of Aurora B activation by INCENP and inhibition by hesperadin. Mol. Cell 2005, 18, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamsipour, F.; Hosseinzadeh, S.; Arab, S.S.; Vafaei, S.; Farid, S.; Jeddi-Tehrani, M.; Balalaie, S. Synthesis and investigation of new Hesperadin analogues antitumor effects on HeLa cells. J. Chem. Biol. 2014, 7, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, J.; Ikezoe, T.; Nishioka, C.; Tasaka, T.; Taniguchi, A.; Kuwayama, Y.; Komatsu, N.; Bandobashi, K.; Togitani, K.; Koeffler, H.P.; et al. AZD1152, a novel and selective aurora B kinase inhibitor, induces growth arrest, apoptosis, and sensitization for tubulin depolymerizing agent or topoisomerase II inhibitor in human acute leukemia cells in vitro and in vivo. Blood 2007, 110, 2034–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bertran-Alamillo, J.; Cattan, V.; Schoumacher, M.; Codony-Servat, J.; Giménez-Capitán, A.; Cantero, F.; Burbridge, M.; Rodríguez, S.; Teixidó, C.; Roman, R.; et al. AURKB as a target in non-small cell lung cancer with acquired resistance to anti-EGFR therapy. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfrich, B.A.; Kim, J.; Gao, D.; Chan, D.C.; Zhang, Z.; Tan, A.P.A.B., Jr. Barasertib (AZD1152), a Small Molecule Aurora B Inhibitor, Inhibits the Growth of SCLC Cell Lines In Vitro and In Vivo. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2016, 15, 2314–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wilkinson, R.W.; Odedra, R.; Heaton, S.P.; Wedge, S.R.; Keen, N.J.; Crafter, C.; Foster, J.R.; Brady, M.C.; Bigley, A.; Brown, E.; et al. AZD1152, a selective inhibitor of Aurora B kinase, inhibits human tumor xenograft growth by inducing apoptosis. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007, 13, 3682–3688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tsuboi, K.; Yokozawa, T.; Sakura, T.; Watanabe, T.; Fujisawa, S.; Yamauchi, T.; Uike, N.; Ando, K.; Kihara, R.; Tobinai, K.; et al. A phase I study to assess the safety, pharmacokinetics and efficacy of barasertib (AZD1152), an Aurora B kinase inhibitor, in Japanese patients with advanced acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk. Res. 2011, 35, 1384–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, M.; Davies, M.; Oliver, S.; D’Souza, R.; Pike, L.; Stockman, P. Phase i study of the Aurora B kinase inhibitor barasertib (AZD1152) to assess the pharmacokinetics, metabolism and excretion in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2012, 70, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Creutzig, U.; Kaspers, G.J.L. Revised recommendations of the International Working Group for diagnosis, standardization of response criteria, treatment outcomes, and reporting standards for therapeutic trials in acute myeloid leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 22, 3432–3433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantarjian, H.M.; Martinelli, G.; Jabbour, E.J.; Quintás-Cardama, A.; Ando, K.; Bay, J.O.; Wei, A.; Gröpper, S.; Papayannidis, C.; Owen, K.; et al. Stage i of a phase 2 study assessing the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of barasertib (AZD1152) versus low-dose cytosine arabinoside in elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer 2013, 119, 2611–2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kantarjian, H.M.; Sekeres, M.A.; Ribrag, V.; Rousselot, P.; Garcia-Manero, G.; Jabbour, E.J.; Owen, K.; Stockman, P.K.; Oliver, S.D. Phase i study assessing the safety and tolerability of barasertib (azd1152) with low-dose cytosine arabinoside in elderly patients with AML. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2013, 13, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boss, D.S.; Witteveen, P.O.; Van der Sar, J.; Lolkema, M.P.; Voest, E.E.; Stockman, P.K.; Ataman, O.; Wilson, D.; Das, S.; Schellens, J.H. Clinical evaluation of AZD1152, an i.v. inhibitor of Aurora B kinase, in patients with solid malignant tumors. Ann. Oncol. 2011, 22, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, G.K.; Carvajal, R.D.; Midgley, R.; Rodig, S.J.; Stockman, P.K.; Ataman, O.; Wilson, D.; Das, S.; Shapiro, G.I. Phase i study of barasertib (AZD1152), a selective inhibitor of Aurora B kinase, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Investig. New Drugs 2013, 31, 370–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, G.P.; Eyre, T.A.; Linton, K.M.; Radford, J.; Vallance, G.D.; Soilleux, E.; Hatton, C. A phase II trial of AZD1152 in relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Br. J. Haematol. 2015, 170, 886–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakkaniga, N.R.; Zhang, L.; Belachew, B.; Gunaganti, N.; Frett, B.; Li, H. yu Discovery of SP-96, the first non-ATP-competitive Aurora Kinase B inhibitor, for reduced myelosuppression. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 203, 112589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.I.; Hunt, J.P.; Herrgard, S.; Ciceri, P.; Wodicka, L.M.; Pallares, G.; Hocker, M.; Treiber, D.K.; Zarrinkar, P.P. Comprehensive analysis of kinase inhibitor selectivity. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 1046–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floc’H, N.; Ashton, S.; Taylor, P.; Trueman, D.; Harris, E.; Odedra, R.; Maratea, K.; Derbyshire, N.; Caddy, J.; Jacobs, V.N.; et al. Optimizing Therapeutic Effect of Aurora B Inhibition in Acute Myeloid Leukemia with AZD2811 Nanoparticles. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2017, 16, 1031–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Floc’h, N.; Ashton, S.; Ferguson, D.; Taylor, P.; Carnevalli, L.S.; Hughes, A.M.; Harris, E.; Hattersley, M.; Wen, S.; Curtis, N.J.; et al. Modeling dose and schedule effects of AZD2811 nanoparticles targeting aurora b kinase for treatment of diffuse large b-cell lymphoma. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2019, 18, 909–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zekri, A.; Ghaffari, S.H.; Ghanizadeh-Vesali, S.; Yaghmaie, M.; Salmaninejad, A.; Alimoghaddam, K.; Modarressi, M.H.; Ghavamzadeh, A. AZD1152-HQPA induces growth arrest and apoptosis in androgen-dependent prostate cancer cell line (LNCaP) via producing aneugenic micronuclei and polyploidy. Tumor Biol. 2015, 36, 623–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Qi, Z.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Y.; Liu, F.; Zhao, G.; Wang, Z. Aurora kinase B inhibitor barasertib (AZD1152) inhibits glucose metabolism in gastric cancer cells. Anticancer. Drugs 2019, 30, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aihara, A.; Tanaka, S.; Yasen, M.; Matsumura, S.; Mitsunori, Y.; Murakata, A.; Noguchi, N.; Kudo, A.; Nakamura, N.; Ito, K.; et al. The selective Aurora B kinase inhibitor AZD1152 as a novel treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2010, 52, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noronha, S.; Alt, L.A.C.; Scimeca, T.E.; Zarou, O.; Obrzut, J.; Zanotti, B.; Hayward, E.A.; Pillai, A.; Mathur, S.; Rojas, J.; et al. Preclinical evaluation of the Aurora kinase inhibitors AMG 900, AZD1152-HQPA, and MK-5108 on SW-872 and 93T449 human liposarcoma cells. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol. Anim. 2018, 54, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Zhang, P.; Girdler, F.; Frascogna, V.; Castedo, M.; Bourhis, J.; Kroemer, G.; Deutsch, E. Enhancement of radiation response in p53-deficient cancer cells by the Aurora-B kinase inhibitor AZD1152. Oncogene 2008, 27, 3244–3255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gully, C.P.; Zhang, F.; Chen, J.; Yeung, J.A.; Velazquez-Torres, G.; Wang, E.; Yeung, S.C.J.; Lee, M.H. Antineoplastic effects of an Aurora B kinase inhibitor in breast cancer. Mol. Cancer 2010, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baldini, E.; Tuccilli, C.; Prinzi, N.; Sorrenti, S.; Antonelli, A.; Gnessi, L.; Morrone, S.; Moretti, C.; Bononi, M.; Arlot-Bonnemains, Y.; et al. Effects of selective inhibitors of Aurora kinases on anaplastic thyroid carcinoma cell lines. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2014, 21, 797–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sánchez-Molina, S.; Figuerola-Bou, E.; Blanco, E.; Sánchez-Jiménez, M.; Táboas, P.; Gómez, S.; Ballaré, C.; García-Domínguez, D.J.; Prada, E.; Hontecillas-Prieto, L.; et al. RING1B recruits EWSR1-FLI1 and cooperates in the remodeling of chromatin necessary for Ewing sarcoma tumorigenesis. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuccilli, C.; Baldini, E.; Prinzi, N.; Morrone, S.; Sorrenti, S.; Filippini, A.; Catania, A.; Alessandrini, S.; Rendina, R.; Coccaro, C.; et al. Preclinical testing of selective Aurora kinase inhibitors on a medullary thyroid carcinoma-derived cell line. Endocrine 2016, 52, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.P.; Liu, Z.L.; Peng, A.F.; Zhou, Y.F.; Long, X.H.; Luo, Q.F.; Huang, S.H.; Shu, Y. Inhibition of Aurora-B suppresses osteosarcoma cell migration and invasion. Exp. Ther. Med. 2014, 7, 560–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Löwenberg, B.; Muus, P.; Ossenkoppele, G.; Rousselot, P.; Cahn, J.Y.; Ifrah, N.; Martinelli, G.; Amadori, S.; Berman, E.; Sonneveld, P.; et al. Phase 1/2 study to assess the safety, efficacy, and pharmacokinetics of barasertib (AZD1152) in patients with advanced acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2011, 118, 6030–6036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintás-Cardama, A.; Ravandi, F.; Liu-Dumlao, T.; Brandt, M.; Faderl, S.; Pierce, S.; Borthakur, G.; Garcia-Manero, G.; Cortes, J.; Kantarjian, H. Epigenetic therapy is associated with similar survival compared with intensive chemotherapy in older patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2012, 120, 4840–4845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McNeish, I.; Anthoney, A.; Loadman, P.; Berney, D.; Joel, S.; Halford, S.E.R.; Buxton, E.; Race, A.; Ikram, M.; Scarsbrook, A.; et al. A phase I pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) study of the selective aurora kinase inhibitor GSK1070916A. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dent, S.F.; Gelmon, K.A.; Chi, K.N.; Jonker, D.J.; Wainman, N.; Capier, C.A.; Chen, E.X.; Lyons, J.F.; Seymour, L. NCIC CTG IND.181: Phase i study of AT9283 given as a weekly 24 h infusion in advanced malignancies. Investig. New Drugs 2013, 31, 1522–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hay, A.E.; Murugesan, A.; Dipasquale, A.M.; Kouroukis, T.; Sandhu, I.; Kukreti, V.; Bahlis, N.J.; Lategan, J.; Reece, D.E.; Lyons, J.F.; et al. A phase II study of AT9283, an aurora kinase inhibitor, in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: NCIC clinical trials group IND.191. Leuk. Lymphoma 2016, 57, 1463–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foran, J.; Ravandi, F.; Wierda, W.; Garcia-Manero, G.; Verstovsek, S.; Kadia, T.; Burger, J.; Yule, M.; Langford, G.; Lyons, J.; et al. A phase i and pharmacodynamic study of AT9283, a small-molecule inhibitor of aurora kinases in patients with relapsed/refractory leukemia or myelofibrosis. Clin. Lymphoma, Myeloma Leuk. 2014, 14, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vormoor, B.; Veal, G.J.; Griffin, M.J.; Boddy, A.V.; Irving, J.; Minto, L.; Case, M.; Banerji, U.; Swales, K.E.; Tall, J.R.; et al. A phase I/II trial of AT9283, a selective inhibitor of aurora kinase in children with relapsed or refractory acute leukemia: Challenges to run early phase clinical trials for children with leukemia. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2017, 64, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arkenau, H.T.; Plummer, R.; Molife, L.R.; Olmos, D.; Yap, T.A.; Squires, M.; Lewis, S.; Lock, V.; Yule, M.; Lyons, J.; et al. A phase I dose escalation study of AT9283, a small molecule inhibitor of aurora kinases, in patients with advanced solid malignancies. Ann. Oncol. 2012, 23, 1307–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, L.; Marshall, L.V.; Pearson, A.D.J.; Morland, B.; Elliott, M.; Campbell-Hewson, Q.; Makin, G.; Halford, S.E.R.; Acton, G.; Ross, P.; et al. A phase i trial of AT9283 (a selective inhibitor of aurora kinases) in children and adolescents with solid tumors: A cancer research UK study. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Duong, J.K.; Griffin, M.J.; Hargrave, D.; Vormoor, J.; Edwards, D.; Boddy, A. V A population pharmacokinetic model of AT9283 in adults and children to predict the maximum tolerated dose in children with leukaemia. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2017, 83, 1713–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, R.B.; Jones, S.F.; Aggarwal, C.; Von Mehren, M.; Cheng, J.; Spigel, D.R.; Greco, F.A.; Mariani, M.; Rocchetti, M.; Ceruti, R.; et al. A phase I dose-escalation study of danusertib (PHA-739358) administered as a 24-h infusion with and without granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in a 14-day cycle in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 6694–6701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Borthakur, G.; Dombret, H.; Schafhausen, P.; Brummendorf, T.H.; Boisse, N.; Jabbour, E.; Mariani, M.; Capolongo, L.; Carpinelli, P.; Davite, C.; et al. A phase I study of danusertib (PHA-739358) in adult patients with accelerated or blastic phase chronic myeloid leukemia and philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia resistant or intolerant to imatinib and/or other second generation c-ABL therapy. Haematologica 2015, 100, 898–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meulenbeld, H.J.; Bleuse, J.P.; Vinci, E.M.; Raymond, E.; Vitali, G.; Santoro, A.; Dogliotti, L.; Berardi, R.; Cappuzzo, F.; Tagawa, S.T.; et al. Randomized phase II study of danusertib in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer after docetaxel failure. BJU Int. 2013, 111, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steeghs, N.; Eskens, F.A.L.M.; Gelderblom, H.; Verweij, J.; Nortier, J.W.R.; Ouwerkerk, J.; Van Noort, C.; Mariani, M.; Spinelli, R.; Carpinelli, P.; et al. Phase I pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of the aurora kinase inhibitor danusertib in patients with advanced or metastatic solid tumors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 5094–5101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantarjian, H.M.; Schuster, M.W.; Jain, N.; Advani, A.; Jabbour, E.; Gamelin, E.; Rasmussen, E.; Juan, G.; Anderson, A.; Chow, V.F.; et al. A phase 1 study of AMG 900, an orally administered pan-aurora kinase inhibitor, in adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Am. J. Hematol. 2017, 92, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carducci, M.; Shaheen, M.; Markman, B.; Hurvitz, S.; Mahadevan, D.; Kotasek, D.; Goodman, O.B.; Rasmussen, E.; Chow, V.; Juan, G.; et al. A phase 1, first-in-human study of AMG 900, an orally administered pan-Aurora kinase inhibitor, in adult patients with advanced solid tumors. Investig. New Drugs 2018, 36, 1060–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mross, K.; Richly, H.; Frost, A.; Scharr, D.; Nokay, B.; Graeser, R.; Lee, C.; Hilbert, J.; Goeldner, R.G.; Fietz, O.; et al. A phase I study of BI 811283, an Aurora B kinase inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2016, 78, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Döhner, H.; Müller-Tidow, C.; Lübbert, M.; Fiedler, W.; Krämer, A.; Westermann, J.; Bug, G.; Schlenk, R.F.; Krug, U.; Goeldner, R.G.; et al. A phase I trial investigating the Aurora B kinase inhibitor BI 811283 in combination with cytarabine in patients with acute myeloid leukaemia. Br. J. Haematol. 2019, 185, 583–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, M.L.; Cosaert, J.G.C.E.; Falchook, G.S.; Jones, S.F.; Strickland, D.; Greenlees, C.; Charlton, J.; MacDonald, A.; Overend, P.; Adelman, C.; et al. A phase I, open label, multicenter dose escalation study of AZD2811 nanoparticle in patients with advanced solid tumors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 3098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Shim, J.; Jung, H.A.; Sun, J.-M.; Lee, S.-H.; Park, W.-Y.; Ahn, J.S.; Ahn, M.-J.; Park, K. Biomarker driven phase II umbrella trial study of AZD1775, AZD2014, AZD2811 monotherapy in relapsed small cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 8514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnellan, W.B.; Atallah, E.L.; Asch, A.S.; Patel, M.R.; Yang, J.; Eghtedar, A.; Borthakur, G.M.; Charlton, J.; MacDonald, A.; Korzeniowska, A.; et al. A Phase I/II Study of AZD2811 Nanoparticles (NP) As Monotherapy or in Combination in Treatment-Naïve or Relapsed/Refractory AML/MDS Patients Not Eligible for Intensive Induction Therapy. Blood 2019, 134, 3919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, N.D.; Adams, J.L.; Burgess, J.L.; Chaudhari, A.M.; Copeland, R.A.; Donatelli, C.A.; Drewry, D.H.; Fisher, K.E.; Hamajima, T.; Hardwicke, M.A.; et al. Discovery of GSK1070916, a potent and selective inhibitor of aurora B/C kinase. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 3973–4001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardwicke, M.A.; Oleykowski, C.A.; Plant, R.; Wang, J.; Liao, Q.; Moss, K.; Newlander, K.; Adams, J.L.; Dhanak, D.; Yang, J.; et al. GSK 1070916, a potent Aurora B/C kinase inhibitor with broad antitumor activity in tissue culture cells and human tumor xenograft models. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2009, 8, 1808–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spartà, A.M.; Bressanin, D.; Chiarini, F.; Lonetti, A.; Cappellini, A.; Evangelisti, C.; Evangelisti, C.; Melchionda, F.; Pession, A.; Bertaina, A.; et al. Therapeutic targeting of Polo-like kinase-1 and Aurora kinases in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cell Cycle 2014, 13, 2237–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wu, Z.-X.; Yang, Y.; Wang, J.-Q.; Zhou, W.-M.; Chen, J.; Fu, Y.-G.; Patel, K.; Chen, Z.-S.; Zhang, J.-Y. Elevated ABCB1 Expression Confers Acquired Resistance to Aurora Kinase Inhibitor GSK-1070916 in Cancer Cells. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 615824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zi, D.; Zhou, Z.W.; Yang, Y.J.; Huang, L.; Zhou, Z.L.; He, S.M.; He, Z.X.; Zhou, S.F. Danusertib induces apoptosis, cell cycle arrest, and autophagy but inhibits epithelial to mesenchymal transition involving PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in human ovarian cancer cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 27228–27251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fraedrich, K.; Schrader, J.; Ittrich, H.; Keller, G.; Gontarewicz, A.; Matzat, V.; Kromminga, A.; Pace, A.; Moll, J.; Bläker, M.; et al. TarGeting aurora kinases with danusertib (PHA-739358) inhibits growth of liver metastases from gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors in an orthotopic xenograft model. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 4621–4632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shang, Y.Y.; Yu, N.; Xia, L.; Yu, Y.Y.; Ma, C.M.; Jiao, Y.N.; Li, Y.F.; Wang, Y.; Dang, J.; Li, W. Augmentation of danusertib’s anticancer activity against melanoma by blockage of autophagy. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2020, 10, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, C.X.; Zhou, Z.W.; Yang, Y.X.; He, Z.X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, D.; Yang, T.; Pan, S.Y.; Chen, X.W.; Zhou, S.F. Danusertib, a potent pan-Aurora kinase and ABL kinase inhibitor, induces cell cycle arrest and programmed cell death and inhibits epithelial to mesenchymal transition involving the Pi3K/Akt/mTOR-mediated signaling pathway in human gastric cancer AGS and N. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2015, 9, 1293–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhu, Q.; Yu, X.; Zhou, Z.-W.; Luo, M.; Zhou, C.; He, Z.-X.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, S.-F. A quantitative proteomic response of hepatocellular carcinoma Hep3B cells to danusertib, a pan-Aurora kinase inhibitor. J. Cancer 2018, 9, 2061–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Balabanov, S.; Gontarewicz, A.; Keller, G.; Raddrizzani, L.; Braig, M.; Bosotti, R.; Moll, J.; Jost, E.; Barett, C.; Rohe, I.; et al. Abcg2 overexpression represents a novel mechanism for acquired resistance to the multi-kinase inhibitor danusertib in BCR-ABL-positive cells in vitro. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e19164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.P.; Yang, Y.X.; Liu, Q.L.; Zhou, Z.W.; Pan, S.T.; He, Z.X.; Zhang, X.; Yang, T.; Pan, S.Y.; Duan, W.; et al. The pan-inhibitor of aurora kinases danusertib induces apoptosis and autophagy and suppresses epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in human breast cancer cells. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2015, 9, 1027–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- He, S.J.; Shu, L.P.; Zhou, Z.W.; Yang, T.; Duan, W.; Zhang, X.; He, Z.X.; Zhou, S.F. Inhibition of Aurora kinases induces apoptosis and autophagy via AURKB/p70S6K/RPL15 axis in human leukemia cells. Cancer Lett. 2016, 382, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Meyskens, F.L. The pan-Aurora kinase inhibitor, PHA-739358, induces apoptosis and inhibits migration in melanoma cell lines. Melanoma Res. 2013, 23, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Feng, W.; Li, Y.; Cao, X. Molecular mechanism of Aurora kinase inhibitor PHA739358 in inhibited proliferation and induced apoptosis of breast cancer cells. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2012, 92, 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- Benten, D.; Keller, G.; Quaas, A.; Schrader, J.; Gontarewicz, A.; Balabanov, S.; Braig, M.; Wege, H.; Moll, J.; Lohse, A.W.; et al. Aurora kinase inhibitor PHA-739358 suppresses growth of hepatocellular carcinoma in vitro and in a xenograft mouse model. Neoplasia 2009, 11, 934–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fei, F.; Lim, M.; Schmidhuber, S.; Moll, J.; Groffen, J.; Heisterkamp, N. Treatment of human pre-B acute lymphoblastic leukemia with the Aurora kinase inhibitor PHA-739358 (Danusertib). Mol. Cancer 2012, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Howard, S.; Berdini, V.; Boulstridge, J.A.; Carr, M.G.; Cross, D.M.; Curry, J.; Devine, L.A.; Early, T.R.; Fazal, L.; Gill, A.L.; et al. Fragment-based discovery of the pyrazol-4-yl urea (AT9283), a multitargeted kinase inhibitor with potent aurora kinase activity. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, W.; Liu, X.; Cooke, L.S.; Persky, D.O.; Miller, T.P.; Squires, M.; Mahadevan, D. AT9283, a novel aurora kinase inhibitor, suppresses tumor growth in aggressive B-cell lymphomas. Int. J. Cancer 2012, 130, 2997–3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, C.C.; Kolb, E.A.; Sampson, V.B. Recent advances of cell-cycle inhibitor therapies for pediatric cancer. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 6489–6498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Takeda, T.; Tsubaki, M.; Genno, S.; Nemoto, C.; Onishi, Y.; Yamamoto, Y.; Imano, M.; Satou, T.; Nishida, S. AT9283 exhibits antiproliferative effect on tyrosine kinase inhibitor-sensitive and -resistant chronic myeloid leukemia cells by inhibition of Aurora A and Aurora B. Oncol. Rep. 2020, 44, 2211–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, R.; Squires, M.S.; Kimura, S.; Yokota, A.; Nagao, R.; Yamauchi, T.; Takeuchi, M.; Yao, H.; Reule, M.; Smyth, T.; et al. Activity of the multitargeted kinase inhibitor, AT9283, in imatinib-resistant BCR-ABL-positive leukemic cells. Blood 2010, 116, 2089–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Geuns-Meyer, S.; Cee, V.J.; Deak, H.L.; Du, B.; Hodous, B.L.; Nguyen, H.N.; Olivieri, P.R.; Schenkel, L.B.; Vaida, K.R.; Andrews, P.; et al. Discovery of N -(4-(3-(2-Aminopyrimidin-4-yl)pyridin-2-yloxy)phenyl)-4-(4-methylthiophen-2-yl)phthalazin-1-amine (AMG 900), A Highly Selective, Orally Bioavailable Inhibitor of Aurora Kinases with Activity against Multidrug-Resistant Cancer Cell Lines. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 5189–5207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, J.; Pyo, J.; Lee, C.W.; Kim, J.E. An Aurora kinase inhibitor, AMG900, inhibits glioblastoma cell proliferation by disrupting mitotic progression. Cancer Med. 2018, 7, 5589–5603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payton, M.; Cheung, H.-K.; Ninniri, M.S.S.; Marinaccio, C.; Wayne, W.C.; Hanestad, K.; Crispino, J.D.; Juan, G.; Coxon, A. Dual Targeting of Aurora Kinases with AMG 900 Exhibits Potent Preclinical Activity Against Acute Myeloid Leukemia with Distinct Post-Mitotic Outcomes. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2018, 17, 2575–2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kalous, O.; Conklin, D.; Desai, A.J.; Dering, J.; Goldstein, J.; Ginther, C.; Anderson, L.; Lu, M.; Kolarova, T.; Eckardt, M.A.; et al. AMG 900, pan-Aurora kinase inhibitor, preferentially inhibits the proliferation of breast cancer cell lines with dysfunctional p53. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2013, 141, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Midgley, C.A.; Scaërou, F.; Grabarek, J.B.; Griffiths, G.; Jackson, W.; Kontopidis, G.; McClue, S.J.; McInnes, C.; Meades, C.; et al. Discovery of N-Phenyl-4-(thiazol-5-yl)pyrimidin-2-amine aurora kinase inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 4367–4378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Soncini, C.; Carpinelli, P.; Gianellini, L.; Fancelli, D.; Vianello, P.; Rusconi, L.; Storici, P.; Zugnoni, P.; Pesenti, E.; Croci, V.; et al. PHA-680632, a novel aurora kinase inhibitor with potent antitumoral activity. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006, 12, 4080–4089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lima, K.; Carlos, J.A.E.G.; de Melo Alves-Paiva, R.; Vicari, H.P.; de Souza Santos, F.P.; Hamerschlak, N.; Costa-Lotufo, L.V.; Traina, F.; Machado-Neto, J.A. Reversine exhibits antineoplastic activity in JAK2V617F-positive myeloproliferative neoplasms. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Liu, Z.G.; Zhang, H.; Xie, J.D.; Chen, X.G.; Zhao, X.Q.; Wang, F.; Liang, Y.J.; Chen, L.K.; Singh, S.; et al. Enhancing chemosensitivity in ABCB1- and ABCG2-overexpressing cells and cancer stem-like cells by an Aurora kinase inhibitor CCT129202. Mol. Pharm. 2012, 9, 1971–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okcanoğlu, T.B.; Kayabaşı, Ç.; Gündüz, C. Effect of CCT137690 on long non-coding RNA expression profiles in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cell lines. Bosn. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2020, 20, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Furqan, M.; Huma, Z.; Ashfaq, Z.; Nasir, A.; Ullah, R.; Bilal, A.; Iqbal, M.; Khalid, M.H.; Hussain, I.; Faisal, A. Identification and evaluation of novel drug combinations of Aurora kinase inhibitor CCT137690 for enhanced efficacy in oral cancer cells. Cell Cycle 2019, 18, 2281–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbitrario, J.P.; Belmont, B.J.; Evanchik, M.J.; Flanagan, W.M.; Fucini, R.V.; Hansen, S.K.; Harris, S.O.; Hashash, A.; Hoch, U.; Hogan, J.N.; et al. SNS-314, a pan-Aurora kinase inhibitor, shows potent anti-tumor activity and dosing flexibility in vivo. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2010, 65, 707–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almatroodi, S.A.; Alsahli, M.A.; Almatroudi, A.; Verma, A.K.; Aloliqi, A.; Allemailem, K.S.; Khan, A.A.; Rahmani, A.H. Potential Therapeutic Targets of Quercetin, a Plant Flavonol, and Its Role in the Therapy of Various Types of Cancer through the Modulation of Various Cell Signaling Pathways. Molecules 2021, 26, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xingyu, Z.; Peijie, M.; Dan, P.; Youg, W.; Daojun, W.; Xinzheng, C.; Xijun, Z.; Yangrong, S. Quercetin suppresses lung cancer growth by targeting Aurora B kinase. Cancer Med. 2016, 5, 3156–3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, M.; Feng, X.; Su, D.; Wang, G.; Wang, C.; Tang, M.; Paulucci-Holthauzen, A.; Hart, T.; Chen, J. Genome-wide CRISPR screen uncovers a synergistic effect of combining Haspin and Aurora kinase B inhibition. Oncogene 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traynor, A.M.; Hewitt, M.; Liu, G.; Flaherty, K.T.; Clark, J.; Freedman, S.J.; Scott, B.B.; Leighton, A.M.; Watson, P.A.; Zhao, B.; et al. Phase I dose escalation study of MK-0457, a novel Aurora kinase inhibitor, in adult patients with advanced solid tumors. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2011, 67, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, N.; Maly, D.J.; Chanthery, Y.H.; Sirkis, D.W.; Nakamura, J.L.; Berger, M.S.; James, C.D.; Shokat, K.M.; Weiss, W.A.; Persson, A.I. Radiotherapy followed by aurora kinase inhibition targets tumor-propagating cells in human glioblastoma. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2015, 14, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pinel, S.; Barbault-Foucher, S.; Lott-Desroches, M.-C.; Astier, A. Inhibitors of aurora kinases. Ann. Pharm. Fr. 2009, 67, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.H.; Zhou, Z.W.; Ha, C.F.; Zhang, X.Y.; Pan, S.T.; He, Z.X.; Edelman, J.L.; Wang, D.; Yang, Y.X.; Zhang, X.; et al. Alisertib, an Aurora kinase A inhibitor, induces apoptosis and autophagy but inhibits epithelial to mesenchymal transition in human epithelial ovarian cancer cells. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2015, 9, 425–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yeung, S.-C.; Gully, C.; Lee, M.-H. Aurora-B Kinase Inhibitors for Cancer Chemotherapy. Mini-Reviews Med. Chem. 2008, 8, 1514–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santo, L.; Hideshima, T.; Cirstea, D.; Bandi, M.; Nelson, E.A.; Gorgun, G.; Rodig, S.; Vallet, S.; Pozzi, S.; Patel, K.; et al. Antimyeloma activity of a multitargeted kinase inhibitor, AT9283, via potent Aurora kinase and STAT3 inhibition either alone or in combination with lenalidomide. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 3259–3271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chang, X.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Q.; Rathore, M.G.; Reddy, K.; Chen, H.; Shin, S.H.; Ma, W.Y.; Bode, A.M.; Dong, Z. HI-511 overcomes melanoma drug resistance via targeting AURKB and BRAF V600E. Theranostics 2020, 10, 9721–9740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzariti, A.; Bocci, G.; Porcelli, L.; Fioravanti, A.; Sini, P.; Simone, G.M.; Quatrale, A.E.; Chiarappa, P.; Mangia, A.; Sebastian, S.; et al. Aurora B kinase inhibitor AZD1152: Determinants of action and ability to enhance chemotherapeutics effectiveness in pancreatic and colon cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2011, 104, 769–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boeckx, C.; Op de Beeck, K.; Wouters, A.; Deschoolmeester, V.; Limame, R.; Zwaenepoel, K.; Specenier, P.; Pauwels, P.; Vermorken, J.B.; Peeters, M.; et al. Overcoming cetuximab resistance in HNSCC: The role of AURKB and DUSP proteins. Cancer Lett. 2014, 354, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hole, S.; Pedersen, A.M.; Lykkesfeldt, A.E.; Yde, C.W. Aurora kinase A and B as new treatment targets in aromatase inhibitor-resistant breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2015, 149, 715–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Illert, A.L.; Seitz, A.K.; Rummelt, C.; Kreutmair, S.; Engh, R.A.; Goodstal, S.; Peschel, C.; Duyster, J.; von Bubnoff, N. Inhibition of Aurora kinase B is important for biologic activity of the dual inhibitors of BCR-ABL and Aurora kinases R763/AS703569 and PHA-739358 in BCR-ABL transformed cells. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e112318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Failes, T.W.; Mitic, G.; Abdel-Halim, H.; Po’uha, S.T.; Liu, M.; Hibbs, D.E.; Kavallaris, M. Evolution of resistance to Aurora kinase B inhibitors in leukaemia cells. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e30734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guo, J.; Anderson, M.G.; Tapang, P.; Palma, J.P.; Rodriguez, L.E.; Niquette, A.; Li, J.; Bouska, J.J.; Wang, G.; Semizarov, D.; et al. Identification of genes that confer tumor cell resistance to the aurora B kinase inhibitor, AZD1152. Pharm. J. 2009, 9, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Girdler, F.; Sessa, F.; Patercoli, S.; Villa, F.; Musacchio, A.; Taylor, S. Molecular basis of drug resistance in aurora kinases. Chem. Biol. 2008, 15, 552–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.C.Y.; Frolov, A.; Li, R.; Ayala, G.; Greenberg, N.M. Targeting Aurora kinases for the treatment of prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 4996–5002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nair, J.S.; de Stanchina, E.; Schwartz, G.K. The topoisomerase I poison CPT-11 enhances the effect of the aurora B kinase inhibitor AZD1152 both in vitro and in vivo. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 2022–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shah, O.J.; Lin, X.; Li, L.; Huang, X.; Li, J.; Anderson, M.G.; Tang, H.; Rodriguez, L.E.; Warder, S.E.; McLoughlin, S.; et al. Bcl-XL represents a druggable molecular vulnerability during aurora B inhibitor-mediated polyploidization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 12634–12639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guo, Y.; Wei, Q.; Tan, L.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Li, L.; Jiang, T.; Zhang, S.; Jin, H. Inhibition of AURKB, regulated by pseudogene MTND4P12, confers synthetic lethality to PARP inhibition in skin cutaneous melanoma. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2020, 10, 3458–3474. [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi, T.; Uzui, K.; Shigemi, H.; Negoro, E.; Yoshida, A.; Ueda, T. Aurora B inhibitor barasertib and cytarabine exert a greater-than-additive cytotoxicity in acute myeloid leukemia cells. Cancer Sci. 2013, 104, 926–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oser, M.G.; Fonseca, R.; Chakraborty, A.A.; Brough, R.; Spektor, A.; Jennings, R.B.; Flaifel, A.; Novak, J.S.; Gulati, A.; Buss, E.; et al. Cells lacking the RB1 tumor suppressor gene are hyperdependent on aurora B kinase for survival. Cancer Discov. 2019, 9, 230–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yang, D.; Liu, H.; Goga, A.; Kim, S.; Yuneva, M.; Bishop, J.M. Therapeutic potential of a synthetic lethal interaction between the MYC proto-oncogene and inhibition of aurora-B kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 13836–13841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Diaz, R.J.; Golbourn, B.; Faria, C.; Picard, D.; Shih, D.; Raynaud, D.; Leadly, M.; MacKenzie, D.; Bryant, M.; Bebenek, M.; et al. Mechanism of action and therapeutic efficacy of Aurora kinase B inhibition in MYC overexpressing medulloblastoma. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 3359–3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Murai, S.; Matuszkiewicz, J.; Okuzono, Y.; Miya, H.; DE Jong, R. Aurora B Inhibitor TAK-901 Synergizes with BCL-xL Inhibition by Inducing Active BAX in Cancer Cells. Anticancer. Res. 2017, 37, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, O.; Huppi, K.; Chakka, S.; Gehlhaus, K.; Dubois, W.; Patel, J.; Chen, J.; Mackiewicz, M.; Jones, T.L.; Pitt, J.J.; et al. Loss-of-function RNAi screens in breast cancer cells identify AURKB, PLK1, PIK3R1, MAPK12, PRKD2, and PTK6 as sensitizing targets of rapamycin activity. Cancer Lett. 2014, 354, 336–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, S.; Hwang, E.E.; Guha, R.; O’Neill, A.F.; Melong, N.; Veinotte, C.J.; Saur, A.C.; Wuerthele, K.; Shen, M.; McKnight, C.; et al. High-throughput chemical screening identifies focal adhesion Kinase and Aurora Kinase B inhibition as a synergistic treatment combination in ewing sarcoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tsuno, T.; Natsume, A.; Katsumata, S.; Mizuno, M.; Fujita, M.; Osawa, H.; Nakahara, N.; Wakabayashi, T.; Satoh, Y.; Inagaki, M.; et al. Inhibition of Aurora-B function increases formation of multinucleated cells in p53 gene deficient cells and enhances anti-tumor effect of temozolomide in human glioma cells. J. Neurooncol. 2007, 83, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Bhattacharya, D.; Rangaraj, N.; Chakarvarty, S.; Kondapi, A.K.; Rao, N.M. Aurora kinase B siRNA-loaded lactoferrin nanoparticles potentiate the efficacy of temozolomide in treating glioblastoma. Nanomedicine 2018, 13, 2579–2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alafate, W.; Wang, M.; Zuo, J.; Wu, W.; Sun, L.; Liu, C.; Xie, W.; Wang, J. Targeting Aurora kinase B attenuates chemoresistance in glioblastoma via a synergistic manner with temozolomide. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2019, 215, 152617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, K.S.; Castro-Gamero, A.M.; Moreno, D.A.; Da Silva Silveira, V.; Brassesco, M.S.; De Paula Queiroz, R.G.; De Oliveira, H.F.; Carlotti, C.G.; Scrideli, C.A.; Tone, L.G. Inhibition of Aurora kinases enhances chemosensitivity to temozolomide and causes radiosensitization in glioblastoma cells. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 138, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hijjawi, M.S.; Abutayeh, R.F.; Taha, M.O. Structure-Based Discovery and Bioactivity Evaluation of Novel Aurora-A Kinase Inhibitors as Anticancer Agents via Docking-Based Comparative Intermolecular Contacts Analysis (dbCICA). Molecules 2020, 25, 6003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, M.E. Design, synthesis and molecular docking study of new purine derivatives as Aurora kinase inhibitors. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1229, 129843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sanea, M.M.; Elkamhawy, A.; Paik, S.; Lee, K.; El Kerdawy, A.M.; Syed Nasir Abbas, B.; Joo Roh, E.; Eldehna, W.M.; Elshemy, H.A.H.; Bakr, R.B.; et al. Sulfonamide-based 4-anilinoquinoline derivatives as novel dual Aurora kinase (AURKA/B) inhibitors: Synthesis, biological evaluation and in silico insights. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2020, 28, 115525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, Í.A.; Braga Resende, D.; Ramalho, T.C.; Kuca, K.; Da Cunha, E.F.F. Theoretical Studies Aimed at Finding FLT3 Inhibitors and a Promising Compound and Molecular Pattern with Dual Aurora B/FLT3 Activity. Molecules 2020, 25, 1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sl. No. | Drug | Study | Tumor | Phase | Sponsored by | Remarks | References/Clinical Trials.Gov Identifier |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AZD1152 | A Phase I, Open Label, Multi-centre Study to Assess the Safety, Tolerability, and Pharmacokinetics of AZD1152 in Japanese Patients With Acute Myeloid Leukaemia. | Leukemia | 1 | AstraZeneca (Cambridge, UK) | Promising response rate of 19% (3/16 patients) indicating the requirement of additional studies. | [70]/ NCT00530699 |

| 2 | AZD1152 | A Phase 2 Trial of AZD1152 in Relapsed/Refractory Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma | Lymphoma | 2 | Oxford University Hospitals NHS Trust (Oxford, England) | Although, AURKB appears to be a valid target, the relatively low responses and difficulty in administering makes AZD1152 an unsuitable candidate for monotherapy. | [77]/ NCT01354392 |

| 3 | AZD1152 | A Phase I, Open-Label, Multi-Centre Study to Assess the Safety, Tolerability and Pharmacokinetics of AZD1152 Given as a 2-h or 48-h Intravenous Infusions in Patients With Advanced Solid Malignancies | Solid tumors | 1 | AstraZeneca | Manageable tolerance with neutropenia and leukopenia. | [76]/ NCT00338182 |

| 4 | AZD1152 | A Phase I Open, Non-randomised, Single-centre Study to Assess the Metabolism, Excretion and Pharmacokinetics of AZD1152 and AZD1152 hQPA Following Intravenous Administration of [14C]-AZD1152 in Patients With Acute Myeloid Leukaemia (AML) | Leukemia | 1 | AstraZeneca | The drug was well tolerated in the tested population and excreted via hepatic metabolic routes. Potential benefits can be achieved with further investigations. | [71]/ NCT01019161 |

| 5 | AZD1152 | A Phase I/II, Open Label, Multi-centre Study to Assess the Safety, Tolerability, Pharmacokinetics and Efficacy of AZD1152 in Patients With Acute Myeloid Leukaemia. | Leukemia | 1 | AstraZeneca | A manageable toxicity profile was observed with a response rate of 25% | [92]/ NCT00497991 |

| 6 | AZD1152 | A Phase I, Open-label, Multi-centre, Multiple Ascending Dose Study to Assess the Safety and Tolerability of AZD1152 in Combination With Low Dose Cytosine Arabinoside (LDAC) in Patients With Acute Myeloid Leukaemia (AML) | Leukemia | 1 | AstraZeneca | The combination of Barasertib with low dose cytosine arabinoside showed acceptable tolerability with an overall response rate of 45% at the maximum tolerated dose | [74,93]/ NCT00926731 |

| 7 | AZD1152 | A Randomised, Open-label, Multi-centre, 2-stage, Parallel Group Study to Assess the Efficacy, Safety and Tolerability of AZD1152 Alone and in Combination With Low Dose Cytosine Arabinoside (LDAC) in Comparison With LDAC Alone in Patients Aged ≥ 60 with Newly Diagnosed Acute Myeloid Leukaemia (AML) | Leukemia | 2/3 | AstraZeneca | AZD1152 shows a significant improvement in response when compared to low-dose cytosine arabinoside with relatively high but manageable safety profile. | [73,93]/ NCT00952588 |

| 8 | AZD1152 | A Phase I, Open-Label, Multi-Centre Study to Assess the Safety, Tolerability and Pharmacokinetics of AZD1152 Given as a Continuous 7-Day Intravenous Infusion in Patients With Advanced Solid Malignancies | Solid tumors | 1 | AstraZeneca | The study was discontinued because of technical difficulties in administering the drug and lack of efficacy. Additionally, the prescribed schedule was inconvenient. | [76]/ NCT00497679 |

| 9 | AZD1152 | A Phase I, Open-Label, Multi-Centre Study to Assess the Safety, Tolerability and Pharmacokinetics of AZD1152 Given as a 2 Hour Intravenous Infusion on Two Dose Schedules in Patients With Advanced Solid Malignancies | Solid tumors | 1 | AstraZeneca | The study was terminated because of lack of efficacy of AZD1152 in monotherapy on solid tumors at the time of study | [75]/ NCT00497731 |

| 10 | AZD1152 | A Phase I/II, Open-Label, Multicentre 2-Part Study to Assess the Safety, Tolerability, Pharmacokinetics, and Efficacy of AZD2811 as Monotherapy or in Combination in Treatment-Naïve or Relapsed/Refractory Acute Myeloid Leukaemia Patients Not Eligible for Intensive Induction Therapy. | Leukemia | 1/2 | AstraZeneca | The study is currently in the recruitment phase. | NCT03217838 |

| 11 | GSK1070916 | A Cancer Research UK Phase I Trial to Evaluate Safety, Tolerability, Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Aurora B Inhibitor GSK1070916A in Patients With Advanced Solid Tumors. | Solid tumors | 1 | Cancer Research UK (London, UK) | Neutropenia was the dose limiting toxicity with 85 mg/m2/day being the maximum tolerated dose. | [94]/ NCT01118611 |

| 12 | AT9283 | A Phase I Study of AT9283 Given As a 24-h Infusion on Days 1 and 8 Every Three Weeks in Patients with Advanced Incurable Malignancy | Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and solid tumors | 1 | NCIC Clinical Trials group (Kingston, Canada) | AT9283 showed manageable tolerability with recommended phase 2 dose at 40 mg/m2/day given on day 1 and 8 every 21 days. The dose limiting toxicity was febrile neutropenia. | [95]/ NCT00443976 |

| 13 | AT9283 | A Phase II Study of AT9283 in Patients with Relapsed or Refractory Multiple Myeloma | Multiple myeloma | 2 | NCIC Clinical Trials group | The study reports that the dose and schedule of AT9283 used in the study is not recommended for further investigation for the treatment of multiple myeloma. Although, aurora kinases as a possible drug target is not ruled out. | [96]/ NCT01145989 |

| 14 | AT9283 | A Phase I/IIa Open-label Study to Assess the Safety, Tolerability and Preliminary Efficacy of AT9283, a Small Molecule Inhibitor of Aurora Kinases, in Patients With Refractory Hematological Malignancies | Leukemia | 1/2 | Astex Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (Pleasanton, CA, USA) | The study reports cardiac tachyarrythmias and severe reversible cardiomyopathy in addition to other toxicities associated with cytotoxic therapy. Reduction of leukemic blasts were observed in some patients but this did not lead to a significant clinical response. | [97]/ NCT00522990 |

| 15 | AT9283 | A Cancer Research UK Phase I/IIa Trial of AT9283 (A Selective Inhibitor of Aurora Kinases) Given Over 72 h Every 21 Days Via Intravenous Infusion in Children and Adolescents Aged 6 Months to 18 Years With Relapsed and Refractory Acute Leukemia | Leukemia | 1 | Cancer Research UK | The study shows that although toxicity was tolerable, there was no evidence suggesting efficacy of AT9283. | [98]/ NCT01431664 |

| 16 | AT9283 | A phase I dose escalation study of AT9283, a small molecule inhibitor of aurora kinases, in patients with advanced solid malignancies | Solid tumors | 1 | Astex Therapeutics Ltd. (Pleasanton, CA, USA); Cancer Research UK; Experimental Cancer Medicine Centre (UK); National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre (UK) | AT9283 was well tolerated up to a maximum tolerated dose of 27 mg/m2/72 h and febrile neutropenia was the dose limiting toxicity. | [99] |

| 17 | AT9283 | A Phase I Trial of AT9283 (a Selective Inhibitor of Aurora Kinases) in Children and Adolescents with Solid Tumors: A Cancer Research UK Study | Solid tumors | 1 | Experimental Cancer Medicine Network (UK); Cancer Research UK; the Oak Foundation at The Royal Marsden Hospital (London, UK); National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centres; Children’s Cancer and Leukemia Group (Leicester, UK) | AT9283 had manageable toxicity and was well tolerated. | [100,101]/ NCT00985868 |

| 18 | PHA-739358 | An Exploratory Phase II Study of PHA-739358 in Patients With Multiple Myeloma Harbouring the t(4;14) Translocation With or Without FGFR3 Expression | Multiple myeloma | 2 | Nerviano Medical Sciences (Milan, Italy) | The study was terminated due to low recruitment rate. | NCT00872300 |

| 19 | PHA-739358 | A Pilot Phase II Study of PHA-739358 in Patients With Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Relapsing on Gleevec or c-ABL Therapy | Leukemia | 2 | Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center (Los Angeles, CA, USA) | Results have not been reported so far | NCT00335868 |

| 20 | PHA-739358 | A Phase I Dose-Escalation Study of danusertib (PHA-739358) Administered as a 24-h Infusion With and Without G-CSF in a 14-day Cycle in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors | Solid tumors | 1 | National Cancer Institute (Bethesda, MD, USA) | The study concluded that it was safe to administer danusertib and the recommended phase 2 dose was determined. | [102] |

| 21 | PHA-739358 | A phase I study of danusertib (PHA-739358) in adult patients with accelerated or blastic phase chronic myeloid leukemia and Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia resistant or intolerant to imatinib and/or other second generation c-ABL therapy | Leukemia | 1 | Nerviano Medical Sciences | Danusertib treatment had an acceptable toxicity profile and could be a promising agent for malignancies associated with Bcr-Abl. | [103] |

| 22 | PHA-739358 | Randomized phase II study of danusertib in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer after docetaxel failure | Prostate cancer | 2 | Nerviano Medical Sciences | Drug was well-tolerated with neutropenia being the most common adverse event. Monotherapy with danusertib showed minimal efficacy and further studies are recommended. | [104]/NCT00766324 |

| 23 | PHA-739358 | Phase I Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Study of the Aurora Kinase Inhibitor danusertib in Patients With Advanced or Metastatic Solid Tumors | Solid tumors | 1 | Nerviano Medical Sciences | The recommended phase 2 dose was determined in the study and neutropenia was reported as the dose limiting toxicity. However, it was short lasting and there were no reported non-hematologic toxicities. | [105] |

| 24 | AMG900 | A Phase 1 Study Evaluating the Safety, Tolerability, Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Orally Administered AMG900 in Adult Subjects With Acute Myeloid Leukemia | Leukemia | 1 | Amgen (Thousand Oaks, CA, USA) | The study reported manageable hematologic toxicities but the patient response was modest. Dose escalation was hampered due to prolonged cytopenias. | [106]/ NCT01380756 |

| 25 | AMG900 | A Phase 1, First-in-Human Study Evaluating the Safety, Tolerability, Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Orally Administered AMG900 in Adult Subjects With Advanced Solid Tumors | Solid tumors | 1 | Amgen | AMG900 showed acceptable tolerance. | [107]/ NCT00858377 |

| 26 | CYC116 | A Phase I Pharmacologic Study of CYC116, an Oral Aurora Kinase Inhibitor, in Patients With Advanced Solid Tumors | Solid tumors | 1 | Cyclacel Pharmaceuticals, Inc.(Berkeley Heights, NJ, USA) | The study was terminated by the sponsors | NCT00560716 |

| 27 | BI 811283 | An Open Phase I Single Dose Escalation Study of Two Dosing Schedules of BI 811283 Administered Intravenously Over 24 h Continuous Infusion in Patients With Advanced Solid Tumours With Repeated Administration in Patients With Clinical Benefit | Solid tumors | 1 | Boehringer Ingelheim (Ingelheim am Rhein, Germany) | The study demonstrated a manageable toxicity profile with disease stabilization recorded for 19 patients. Although, the limited anti-cancer activity did not warrant further development of the drug as a monotherapy agent. | [108] NCT00701324 |

| 28 | BI 811283 | An Open Phase I/IIa Trial to Investigate the Maximum Tolerated Dose, Safety, Efficacy and Pharmacokinetics of BI 811283 in Combination With Cytarabine in Patients With Previously Untreated Acute Myeloid Leukaemia Ineligible for Intensive Treatment | Acute Myeloid Leukemia | 2 | Boehringer Ingelheim | An acceptable safety profile was demonstrated but the use of BI 811283 with LDAC did not show increased treatment efficacy in comparison to LDAC treatment in isolation. | [109] NCT00632749 |

| 29 | AZD2811 | A Phase I, Open-Label, Multicentre Dose Escalation Study to Assess the Safety, Tolerability, and Pharmacokinetics of AZD2811 in Patients With Advanced Solid Tumours. | Solid tumors | 1 | AstraZeneca | The study determined the maximum tolerable dose and the drug is in further investigation | [110] NCT02579226 |

| 30 | AZD2811 | Phase II, Single-arm Study of AZD2811 and Durvalumab (MEDI4736) Combination Therapy in Relapsed Small Cell Lung Cancer Subjects With c-MYC Expression [SUKSES-E] | Small cell lung cancer | 2 | Keunchil Park, Samsung Medical Center (Seoul, South Korea) | The study is in the recruitment phase | NCT04525391 |

| 31 | AZD2811 | Phase II, Single-arm Study of AZD 2811 Monotherapy in Relapsed Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients [SUKSES-N3] | Small cell lung cancer | 2 | Samsung Medical Center | The study was terminated as the purpose of the study was fulfilled earlier. | [111] NCT03366675 |

| 32 | AZD2811 | A Phase II Multicenter, Open-Label, Single Arm Study to Determine the Efficacy, Safety and Tolerability of AZD2811 and Durvalumab Combination as Maintenance Therapy After Induction With Platinum-Based Chemotherapy Combined With Durvalumab, for the First-Line Treatment of Patients With Extensive Stage Small-Cell Lung Cancer | Small cell lung cancer | 2 | AstraZeneca | New study. The recruitment has not started yet | NCT04745689 |

| 33 | AZD2811 | A Phase I/II, Open-Label, Multicentre 2-Part Study to Assess the Safety, Tolerability, Pharmacokinetics, and Efficacy of AZD2811 as Monotherapy or in Combination in Treatment-Naïve or Relapsed/Refractory Acute Myeloid Leukaemia Patients Not Eligible for Intensive Induction Therapy. | Acute Myeloid Leukemia | 1/2 | AstraZeneca | This is an ongoing study and the latest update suggests good tolerability of the drug. Dose escalations are currently being planned. | [112] NCT03217838 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Borah, N.A.; Reddy, M.M. Aurora Kinase B Inhibition: A Potential Therapeutic Strategy for Cancer. Molecules 2021, 26, 1981. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26071981

Borah NA, Reddy MM. Aurora Kinase B Inhibition: A Potential Therapeutic Strategy for Cancer. Molecules. 2021; 26(7):1981. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26071981

Chicago/Turabian StyleBorah, Naheed Arfin, and Mamatha M. Reddy. 2021. "Aurora Kinase B Inhibition: A Potential Therapeutic Strategy for Cancer" Molecules 26, no. 7: 1981. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26071981