The Relationship between the IC50 Values and the Apparent Inhibition Constant in the Study of Inhibitors of Tyrosinase Diphenolase Activity Helps Confirm the Mechanism of Inhibition

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Diphenolase Activity

2.2. Tyrosinase Inhibition by Benzoate and Cinnamate

Check of Inhibition by Cinnamate and Benzoate. Calculation of the IC50 Value and Its Relationship with

2.3. Discussion about the Relationship of IC50 and the Values of the Inhibition Constant with Data from the Literature for Tyrosinase

2.3.1. With Reference to Competitive Inhibitors

2.3.2. With Reference to Non-Competitive Inhibitors

2.3.3. With Reference to Uncompetitive Inhibitors

2.3.4. With Reference to Mixed-Type Inhibitors

2.4. Other Possible Causes of the Lack of Correlation between IC50 and

2.4.1. Inhibitor Can Be Alternative Substrate

2.4.2. Inhibitor Can Be a Suicide Substrate

2.4.3. Enzyme Inhibition Assay Design

Preincubations and Use of Organic Solvents

2.5. Proposal for an Experimental Design to Determine the Type and Strength of a Tyrosinase Inhibitor from Values

- could be competitive.

- is non-competitive and .

- could be uncompetitive.

- ambiguity between competitive and mixed type (1).

- ambiguity between competitive and mixed type (2).

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Enzyme Source

3.2. Reagents

3.3. Spectrophotometric Assays

3.4. Simulation Assays

3.5. Kinetic Data Analysis

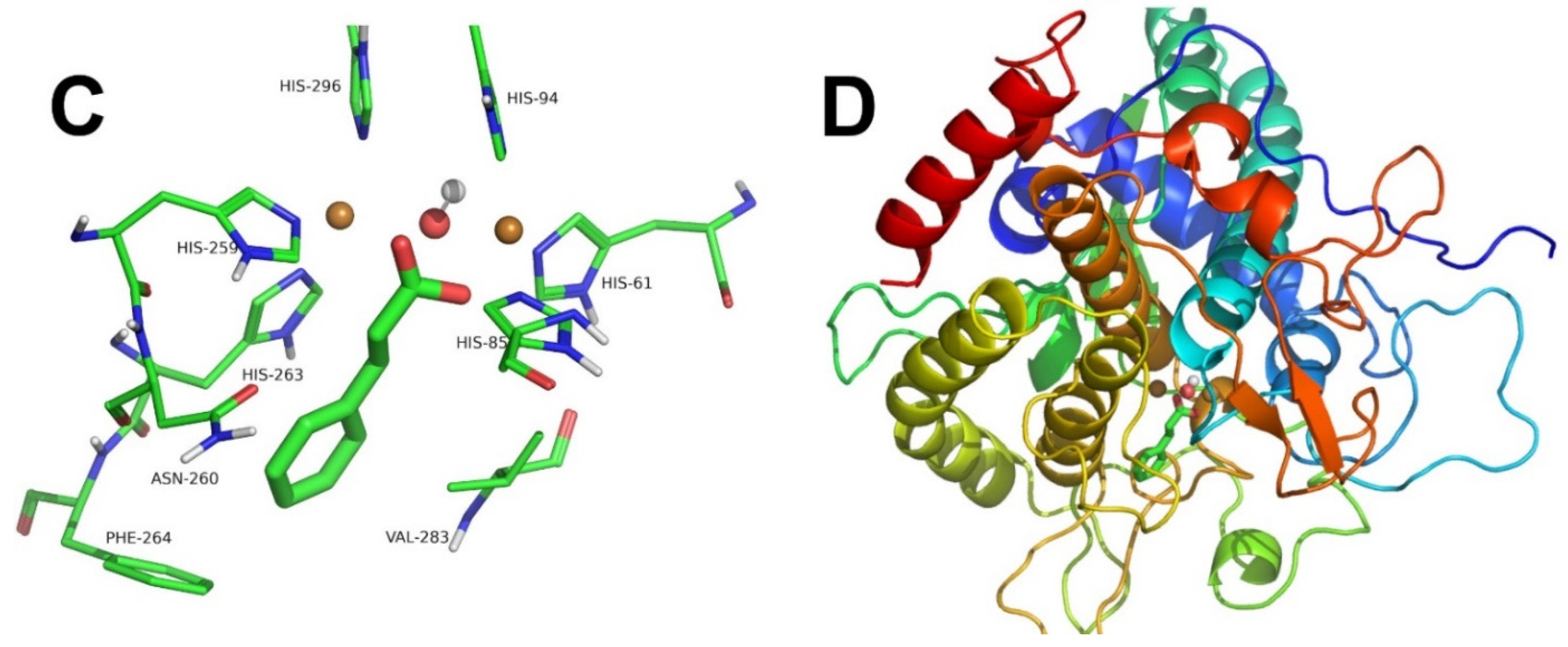

3.6. Computational Docking

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

References

- Kanteev, M.; Goldfeder, M.; Fishman, A. Structure–function correlations in tyrosinases. Protein Sci. 2015, 24, 1360–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Ferrer, Á.; Neptuno Rodríguez-López, J.; García-Cánovas, F.; García-Carmona, F. Tyrosinase: A comprehensive review of its mechanism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Protein Struct. Mol. Enzymol. 1995, 1247, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Huh, Y.; Lim, K.-M. Anti-Pigmentary Natural Compounds and Their Mode of Action. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maddaleno, A.S.; Camargo, J.; Mitjans, M.; Vinardell, M.P. Melanogenesis and Melasma Treatment. Cosmetics 2021, 8, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolghadri, S.; Bahrami, A.; Hassan Khan, M.T.; Munoz-Munoz, J.; Garcia-Molina, F.; Garcia-Canovas, F.; Saboury, A.A. A comprehensive review on tyrosinase inhibitors. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2019, 34, 279–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, X.; Bian, G.; Kang, P.; Cheng, X.; Yan, K.; Liu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Li, D. Recent advance in the discovery of tyrosinase inhibitors from natural sources via separation methods. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2021, 36, 2104–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, R.; Zucca, P.; Rescigno, A.; Peddio, S.; Saleem, R.S.Z.; Batool, S. Plants as a Promising Reservoir of Tyrosinase Inhibitors. Mini-Rev. Org. Chem. 2020, 18, 808–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Wang, G.; Zeng, Q.-H.; Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, J.J.; Zhao, Y. A systematic review of synthetic tyrosinase inhibitors and their structure-activity relationship. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Feng, L.; Liu, L.; Wang, F.; Ouyang, L.; Zhang, L.; Hu, X.; Wang, G. Recent advances in the design and discovery of synthetic tyrosinase inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 224, 113744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillaiyar, T.; Manickam, M.; Jung, S.-H. Inhibitors of melanogenesis: A patent review (2009–2014). Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2015, 25, 775–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillaiyar, T.; Namasivayam, V.; Manickam, M.; Jung, S.-H. Inhibitors of Melanogenesis: An Updated Review. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 7395–7418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina, F.G.; Muñoz, J.L.; Varón, R.; López, J.N.R.; Cánovas, F.G.; Tudela, J. An approximate analytical solution to the lag period of monophenolase activity of tyrosinase. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2007, 39, 238–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz-Ruiz, C.V.; Maria-Solano, M.A.; Garcia-Molina, M.D.M.; Varon, R.; Tudela, J.; Tomas, V.; Garcia-Canovas, F. Kinetic characterization of substrate-analogous inhibitors of tyrosinase. IUBMB Life 2015, 67, 757–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ujan, R.; Saeed, A.; Ashraf, S.; Channar, P.A.; Abbas, Q.; Rind, M.A.; Hassan, M.; Raza, H.; Seo, S.-Y.; El-Seedi, H.R. Synthesis, computational studies and enzyme inhibitory kinetics of benzothiazole-linked thioureas as mushroom tyrosinase inhibitors. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021, 39, 7035–7043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iraji, A.; Panahi, Z.; Edraki, N.; Khoshneviszadeh, M.; Khoshneviszadeh, M. Design, synthesis, in vitro and in silico studies of novel Schiff base derivatives of 2-hydroxy-4-methoxybenzamide as tyrosinase inhibitors. Drug Dev. Res. 2021, 82, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung-Chi, C.; Prusoff, W.H. Relationship between the inhibition constant (KI) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 per cent inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1973, 22, 3099–3108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés, A.; Cascante, M.; Cárdenas, M.L.; Cornish-Bowden, A. Relationships between inhibition constants, inhibitor concentrations for 50% inhibition and types of inhibition: New ways of analysing data. Biochem. J. 2001, 357, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.-J.; Wu, J.C. A Simple Kinetic Method for Rapid Mechanistic Analysis of Reversible Enzyme Inhibitors. Assay Drug Dev. Technol. 2003, 1, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buker, S.M.; Boriack-Sjodin, P.A.; Copeland, R.A. Enzyme-Inhibitor Interactions and a Simple, Rapid Method for Determining Inhibition Modality. SLAS Discov. Adv. Life Sci. R D 2019, 24, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-López, J.N.; Fenoll, L.G.; Peñalver, M.J.; García-Ruiz, P.A.; Varón, R.; Martínez-Ortíz, F.; García-Cánovas, F.; Tudela, J. Tyrosinase action on monophenols: Evidence for direct enzymatic release of o-diphenol. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Protein Struct. Mol. Enzymol. 2001, 1548, 238–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-López, J.N.; Ros, J.R.; Varón, R.; García-Cánovas, F. Oxygen Michaelis constants for tyrosinase. Biochem. J. 1993, 293, 859–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenoll, L.G.; Rodríguez-López, J.N.; García-Molina, F.; García-Cánovas, F.; Tudela, J. Michaelis constants of mushroom tyrosinase with respect to oxygen in the presence of monophenols and diphenols. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2002, 34, 332–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornish-Bowden, A. Fundamentals of Enzyme Kinetics; Portland Press: London, UK, 1995; ISBN 1855780720. [Google Scholar]

- Segel, I.H. Enzyme Kinetics: Behavior and Analysis of Rapid Equilibrium and Steady State Enzyme Systems; Irwin, H.S., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Copeland, R.A. Enzymes: A Practical Introduction to Structure, Mechanism, and Data Analysis, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0-471-35929-6. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Choi, H.; Park, Y.; Jung, H.J.; Ullah, S.; Choi, I.; Kang, D.; Park, C.; Ryu, I.Y.; Jeong, Y.; et al. Urolithin and Reduced Urolithin Derivatives as Potent Inhibitors of Tyrosinase and Melanogenesis: Importance of the 4-Substituted Resorcinol Moiety. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Ran, M.; Wang, M.; Liu, X.; Liu, S.; Yu, Y. Structure–activity relationships of antityrosinase and antioxidant activities of cinnamic acid and its derivatives. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2021, 85, 1697–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Öztürk, C.; Bayrak, S.; Demir, Y.; Aksoy, M.; Alım, Z.; Özdemir, H.; İrfan Küfrevioglu, Ö. Some indazoles as alternative inhibitors for potato polyphenol oxidase. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gheibi, N.; Taherkhani, N.; Ahmadi, A.; Haghbeen, K.; Ilghari, D. Characterization of inhibitory effects of the potential therapeutic inhibitors, benzoic acid and pyridine derivatives, on the monophenolase and diphenolase activities of tyrosinase. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2015, 18, 122–129. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.-F.; Hu, Y.-H.; Lin, H.-T.; Liu, X.; Chen, Y.-H.; Zhang, S.; Chen, Q.-X. Inhibitory Effects of Propyl Gallate on Tyrosinase and Its Application in Controlling Pericarp Browning of Harvested Longan Fruits. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 2889–2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.-H.; Li, Y.-F.; Gan, H.-X.; Feng, N.; Han, Y.-P.; Li, L.-M. Synergistic effects and antityrosinase mechanism of four plant polyphenols from Morus and Hulless Barley. Food Chem. 2022, 374, 131716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Z.; Ge, S.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, P.; Zhang, K.; Xu, X.; Li, C.; Zhao, D.; Tang, X. Design, synthesis and evaluation of cinnamic acid ester derivatives as mushroom tyrosinase inhibitors. Medchemcomm 2018, 9, 853–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.J.; Choi, D.C.; Noh, S.G.; Choi, H.; Choi, I.; Ryu, I.Y.; Chung, H.Y.; Moon, H.R. New Benzimidazothiazolone Derivatives as Tyrosinase Inhibitors with Potential Anti-Melanogenesis and Reactive Oxygen Species Scavenging Activities. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, Y.; Saeed, A.; Rafiq, M.; Afzal, S.; Ali, A.; Latif, M.; Zuegg, J.; Hussein, W.M.; Fercher, C.; Barnard, R.T.; et al. Hydroxyl substituted benzoic acid/cinnamic acid derivatives: Tyrosinase inhibitory kinetics, anti-melanogenic activity and molecular docking studies. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 30, 126722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashim, F.J.; Vichitphan, S.; Han, J.; Vichitphan, K. Alternative Approach for Specific Tyrosinase Inhibitor Screening: Uncompetitive Inhibition of Tyrosinase by Moringa oleifera. Molecules 2021, 26, 4576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.K.; Heo, H.-Y.; Park, S.; Kim, H.; Oh, J.J.; Sohn, E.-H.; Jung, S.-H.; Lee, K. Characterization of Phenethyl Cinnamamide Compounds from Hemp Seed and Determination of Their Melanogenesis Inhibitory Activity. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 31945–31954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, N.T.; Dang, P.H.; Nguyen, H.X.; Do, T.N.V.; Le, T.H.; Le, T.Q.H.; Nguyen, M.T.T. Tyrosinase Inhibitors from the Stems of Streblus Ilicifolius. Evid. Based Complementary Altern. Med. 2021, 2021, 5561176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.-P.; Chen, Q.-X.; Huang, H.; Wang, H.-Z.; Zhang, R.-Q. Inhibitory Effects of Some Flavonoids on the Activity of Mushroom Tyrosinase. Biochemistry 2003, 68, 487–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhao, X.; Tao, G.-J.; Chen, J.; Zheng, Z.-P. Investigating the inhibitory activity and mechanism differences between norartocarpetin and luteolin for tyrosinase: A combinatory kinetic study and computational simulation analysis. Food Chem. 2017, 223, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampatsikas, I.; Pretzler, M.; Rompel, A. Identification of Amino Acid Residues Responsible for C−H Activation in Type-III Copper Enzymes by Generating Tyrosinase Activity in a Catechol Oxidase. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 20940–20945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfeder, M.; Kanteev, M.; Isaschar-Ovdat, S.; Adir, N.; Fishman, A. Determination of tyrosinase substrate-binding modes reveals mechanistic differences between type-3 copper proteins. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matoba, Y.; Oda, K.; Muraki, Y.; Masuda, T. The basicity of an active-site water molecule discriminates between tyrosinase and catechol oxidase activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 183, 1861–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Jimenez, A.; Munoz-Munoz, J.L.; García-Molina, F.; Teruel-Puche, J.A.; García-Cánovas, F. Spectrophotometric Characterization of the Action of Tyrosinase on p-Coumaric and Caffeic Acids: Characteristics of o-Caffeoquinone. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 3378–3386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Jimenez, A.; García-Molina, F.; Teruel-Puche, J.A.; Saura-Sanmartin, A.; Garcia-Ruiz, P.A.; Ortiz-Lopez, A.; Rodríguez-López, J.N.; Garcia-Canovas, F.; Munoz-Munoz, J. Catalysis and inhibition of tyrosinase in the presence of cinnamic acid and some of its derivatives. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 119, 548–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz-Muñoz, J.L.; García-Molina, F.; García-Ruiz, P.A.; Molina-Alarcón, M.; Tudela, J.; García-Cánovas, F.; Rodríguez-López, J.N. Phenolic substrates and suicide inactivation of tyrosinase: Kinetics and mechanism. Biochem. J. 2008, 416, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Muñoz-Muñoz, J.L.; Garcia-Molina, F.; Varon, R.; Garcia-Ruíz, P.A.; Tudela, J.; Garcia-Cánovas, F.; Rodríguez-López, J.N. Suicide inactivation of the diphenolase and monophenolase activities of tyrosinase. IUBMB Life 2010, 62, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz-Ruiz, C.V.; Ballesta de los Santos, M.; Berna, J.; Fenoll, J.; Garcia-Ruiz, P.A.; Tudela, J.; Garcia-Canovas, F. Kinetic characterization of oxyresveratrol as a tyrosinase substrate. IUBMB Life 2015, 67, 828–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Munoz-Munoz, J.L.; García-Molina, F.; Varón, R.; Tudela, J.; García-Cánovas, F.; Rodríguez-López, J.N. Generation of hydrogen peroxide in the melanin biosynthesis pathway. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Proteins Proteom. 2009, 1794, 1017–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz-Munoz, J.L.; García-Molina, F.; Molina-Alarcón, M.; Tudela, J.; García-Cánovas, F.; Rodríguez-López, J.N. Kinetic Characterization of the Enzymatic and Chemical Oxidation of the Catechins in Green Tea. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 9215–9224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.-X.; Liu, X.-D.; Huang, H. Inactivation kinetics of mushroom tyrosinase in the dimethyl sulfoxide solution. Biochemistry 2003, 68, 644–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rodakiewicz-Nowak, J.; Ito, M. Effect of water-miscible solvents on the organic solvent-resistant tyrosinase from Streptomyces sp. REN-21. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2003, 78, 809–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-Q.; Li, Z.-C.; Pan, Z.-Z.; Zhu, Y.-J.; Yan, R.-R.; Wang, Q.; Yan, J.-H.; Chen, Q.-X. Inactivation kinetics of polyphenol oxidase from pupae of blowfly (Sarcophaga bullata) in the dimethyl sulfoxide solution. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2010, 160, 2166–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-López, J.N.; Fenoll, L.G.; García-Ruiz, P.A.; Varón, R.; Tudela, J.; Thorneley, R.N.F.; García-Cánovas, F. Stopped-Flow and Steady-State Study of the Diphenolase Activity of Mushroom Tyrosinase. Biochemistry 2000, 39, 10497–10506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismaya, W.T.; Rozeboom, H.J.; Weijn, A.; Mes, J.J.; Fusetti, F.; Wichers, H.J.; Dijkstra, B.W. Crystal Structure of Agaricus bisporus Mushroom Tyrosinase: Identity of the Tetramer Subunits and Interaction with Tropolone. Biochemistry 2011, 50, 5477–5486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- García-Molina, F.; Muñoz, J.L.; Varón, R.; Rodríguez-López, J.N.; García-Cánovas, F.; Tudela, J. A Review on Spectrophotometric Methods for Measuring the Monophenolase and Diphenolase Activities of Tyrosinase. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 9739–9749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Sevilla, F.; Garrido-del Solo, C.; Duggleby, R.G.; García-Cánovas, F.; Peyró, R.; Varón, R. Use of a windows program for simulation of the progress curves of reactants and intermediates involved in enzyme-catalyzed reactions. Biosystems 2000, 54, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Systat Software. Sigma Plot 9.0 for Windows; Systat Software: San Jose, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Varon, R.; Garcia-Sevilla, F.; Garcia-Moreno, M.; Garcia-Canovas, F.; Peyro, R.; Duggleby, R.G. Computer program for the equations describing the steady state of enzyme reactions. Bioinformatics 1997, 13, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, S.; Thiessen, P.A.; Bolton, E.E.; Chen, J.; Fu, G.; Gindulyte, A.; Han, L.; He, J.; He, S.; Shoemaker, B.A.; et al. PubChem Substance and Compound databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, D1202–D1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria-Solano, M.A.; Ortiz-Ruiz, C.V.; Muñoz-Muñoz, J.L.; Teruel-Puche, J.A.; Berna, J.; Garcia-Ruiz, P.A.; Garcia-Canovas, F. Further insight into the pH effect on the catalysis of mushroom tyrosinase. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2016, 125, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanner, M.F. Python: A programming language for software integration and development. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 1999, 17, 57–61. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, G.M.; Huey, R.; Lindstrom, W.; Sanner, M.F.; Belew, R.K.; Goodsell, D.S.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 2785–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huey, R.; Morris, G.M.; Olson, A.J.; Goodsell, D.S. A semiempirical free energy force field with charge-based desolvation. J. Comput. Chem. 2007, 28, 1145–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Molina, P.; García-Molina, F.; Teruel-Puche, J.A.; Rodríguez-López, J.N.; García-Cánovas, F.; Muñoz-Muñoz, J.L. Considerations about the kinetic mechanism of tyrosinase in its action on monophenols: A review. Mol. Catal. 2022, 518, 112072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger, L. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, V. 2.3. Available online: https://www.schrodinger.com/products/pymol (accessed on 8 April 2022).

- Adasme, M.F.; Linnemann, K.L.; Bolz, S.N.; Kaiser, F.; Salentin, S.; Haupt, V.J.; Schroeder, M. PLIP 2021: Expanding the scope of the protein–ligand interaction profiler to DNA and RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W530–W534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Inhibitor | ||

|---|---|---|

| Benzoate | 0.49 ± 0.01 | 0.53 ± 0.06 |

| Cinnamate | 0.40 ± 0.01 | 0.44 ± 0.04 |

| Figures | Compound Name | Inhibition Type | Oxy | Met | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kd (mM) | Kd (mM) | ||||

| Figure 3A,B and Figure 4A,B | Benzoate | Competitive | 2.76 | 0.072 | [13] |

| Figure 3C,D and Figure 4C,D | Cinnamate | Competitive | 3.73 | 0.016 | [13] |

| Figure S8 | 2′-(Hydroxymethyl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-2,4-diol | Competitive | 14.05 | 1.86 | [26] |

| Figure S9 | trans-3,4-Diflurocinnamate | Competitive | 3.29 | 0.14 | [27] |

| Figure S10 | 6-Fluoro-1H-indazole | Non-competitive | 0.5 | 0.77 | [28] |

| Figure S10 | 7-Fluoro-1H-indazole | Non-competitive | 0.5 | 0.6 | [28] |

| Figure S10 | 4-Chloro-1H-indazole | Non-competitive | 0.5 | 0.4 | [28] |

| Figure S10 | 6-Bromo-1H-indazole | Non-competitive | 0.47 | 0.9 | [28] |

| Figure S10 | 7-Bromo-1H-indazole | Non-competitive | 0.47 | 0.34 | [28] |

| Figure S11 | 2-Aminobenzoate | Non-competitive | 1.87 | 0.052 | [29] |

| Figure S11 | 4-Aminobenzoate | Non-competitive | 2.17 | 0.081 | [29] |

| Figure S15 | Propyl gallate | Mixed | 3.91 | 0.68 | [30] |

| Figure S17 | Sanggenone C | Competitive | 255.29 | 0.034 | [31] |

| Figure S25 | (E)-2-Acetyl-5-methoxyphenyl-3-(4-methoxyphenyl)acrylate | Mixed | 0.3 | 0.46 | [32] |

| Figures | Compound Name | Inhibition Type Proposed | Oxy | Met | Possible Alternative Substrate | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kd (mM) | d-O2 (Ᾰ) | Kd (mM) | |||||

| Figure 5A,B | [2-(3-Methoxyphenoxy)-2-oxoethyl] 2,4-dihydroxybenzoate | Non-competitive | 0.5 | 2.8 | 0.25 | Monophenol | [34] |

| Figure 6A,B | 2-(3-methoxyphenoxy)-2-oxoethyl-(E)-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl) acrylate | Non-competitive | 0.36 | 2.8 | 0.25 | Monophenol | [34] |

| Figure S2 | (Z)-2-(4-Hydroxybenzylidene)benzo[4,5]imidazo[2,1-b]thiazol-3(2H)-one | Competitive | 0.14 | 2.9 | 0.15 | Monophenol | [33] |

| Figure S3A,B | (Z)-2-(3,4-Dihydroxybenzylidene)benzo[4,5]imidazo[2,1-b]thiazol-3(2H)-one | Competitive | 0.14 | - | 0.089 | o-Diphenol | [33] |

| Figure S4 | (Z)-2-(2,4-Dihydroxybenzylidene)benzo[4,5]imidazo[2,1-b]thiazol-3(2H)-one | Competitive | 0.25 | 2.7 | 0.19 | Monophenol | [33] |

| Figure S6 | 1,3-Dihydroxy-6H-benzo[c]chromen-6-one | Competitive | 0.71 | 3.7 | 0.34 | Monophenol | [26] |

| Figure S7 | 1,3-Dihydroxy-8-methoxy-6H-benzo[c]chromen-6-one | Competitive | 0.99 | 3.7 | 0.51 | Monophenol | [26] |

| Figures S13 and S14 | Luteolin | Uncompetitive Non-competitive | 1.1 | - | 14.57 | o-Diphenol | [35] |

| Figure S18 | Oxyresveratrol | Non-competitive | 4.8 | 4.8 | 1.18 | Monophenol | [31] |

| Figure S19A,B | L-Epicatechin | Competitive | 3.84 | - | 4.9 | o-Diphenol | [31] |

| Figure S20A,B | Catechin | Competitive | 3.87 | - | 2.27 | o-Diphenol | [31] |

| Figure S22A,B | N-trans-Caffeoyltyramine | Competitive | 1.5 | - | 0.15 | o-Diphenol | [36] |

| Figure S23 | N-trans-feruloyltyramine | Competitive | 0.093 | 2.9 | 0.038 | Monophenol | [36] |

| Figure S24 | N-trans-Coumaroyltyramine | Competitive | 0.067 | 2.8 | 0.032 | Monophenol | [36] |

| Figure S26 | (E)-2-Acetyl-5-methoxyphenyl-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)acrylate | Non-competitive | 0.11 | 2.8 | 0.115 | Monophenol | [32] |

| Figure S27 | (E)-2-Isopropyl-5-methylphenyl-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)acrylate | Mixed | 0.15 | 2.8 | 0.12 | Monophenol | [32] |

| Figure S29 | Streblus C | Competitive | 0.076 | 2.7 | 0.071 | Monophenol | [37] |

| Figure S30 | Streblus D | Competitive | 1.3 | 3.4 | 0.24 | Monophenol | [37] |

| Type | |

|---|---|

| Competitive | |

| Non-competitive | |

| Uncompetitive | |

| Mixed type (1) | |

| Mixed type (2) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Garcia-Molina, P.; Garcia-Molina, F.; Teruel-Puche, J.A.; Rodriguez-Lopez, J.N.; Garcia-Canovas, F.; Muñoz-Muñoz, J.L. The Relationship between the IC50 Values and the Apparent Inhibition Constant in the Study of Inhibitors of Tyrosinase Diphenolase Activity Helps Confirm the Mechanism of Inhibition. Molecules 2022, 27, 3141. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27103141

Garcia-Molina P, Garcia-Molina F, Teruel-Puche JA, Rodriguez-Lopez JN, Garcia-Canovas F, Muñoz-Muñoz JL. The Relationship between the IC50 Values and the Apparent Inhibition Constant in the Study of Inhibitors of Tyrosinase Diphenolase Activity Helps Confirm the Mechanism of Inhibition. Molecules. 2022; 27(10):3141. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27103141

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcia-Molina, Pablo, Francisco Garcia-Molina, Jose Antonio Teruel-Puche, Jose Neptuno Rodriguez-Lopez, Francisco Garcia-Canovas, and Jose Luis Muñoz-Muñoz. 2022. "The Relationship between the IC50 Values and the Apparent Inhibition Constant in the Study of Inhibitors of Tyrosinase Diphenolase Activity Helps Confirm the Mechanism of Inhibition" Molecules 27, no. 10: 3141. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27103141

APA StyleGarcia-Molina, P., Garcia-Molina, F., Teruel-Puche, J. A., Rodriguez-Lopez, J. N., Garcia-Canovas, F., & Muñoz-Muñoz, J. L. (2022). The Relationship between the IC50 Values and the Apparent Inhibition Constant in the Study of Inhibitors of Tyrosinase Diphenolase Activity Helps Confirm the Mechanism of Inhibition. Molecules, 27(10), 3141. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27103141