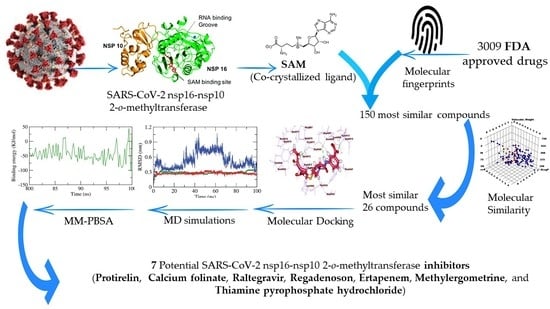

Ligand and Structure-Based In Silico Determination of the Most Promising SARS-CoV-2 nsp16-nsp10 2′-o-Methyltransferase Complex Inhibitors among 3009 FDA Approved Drugs

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Filter Using Fingerprint

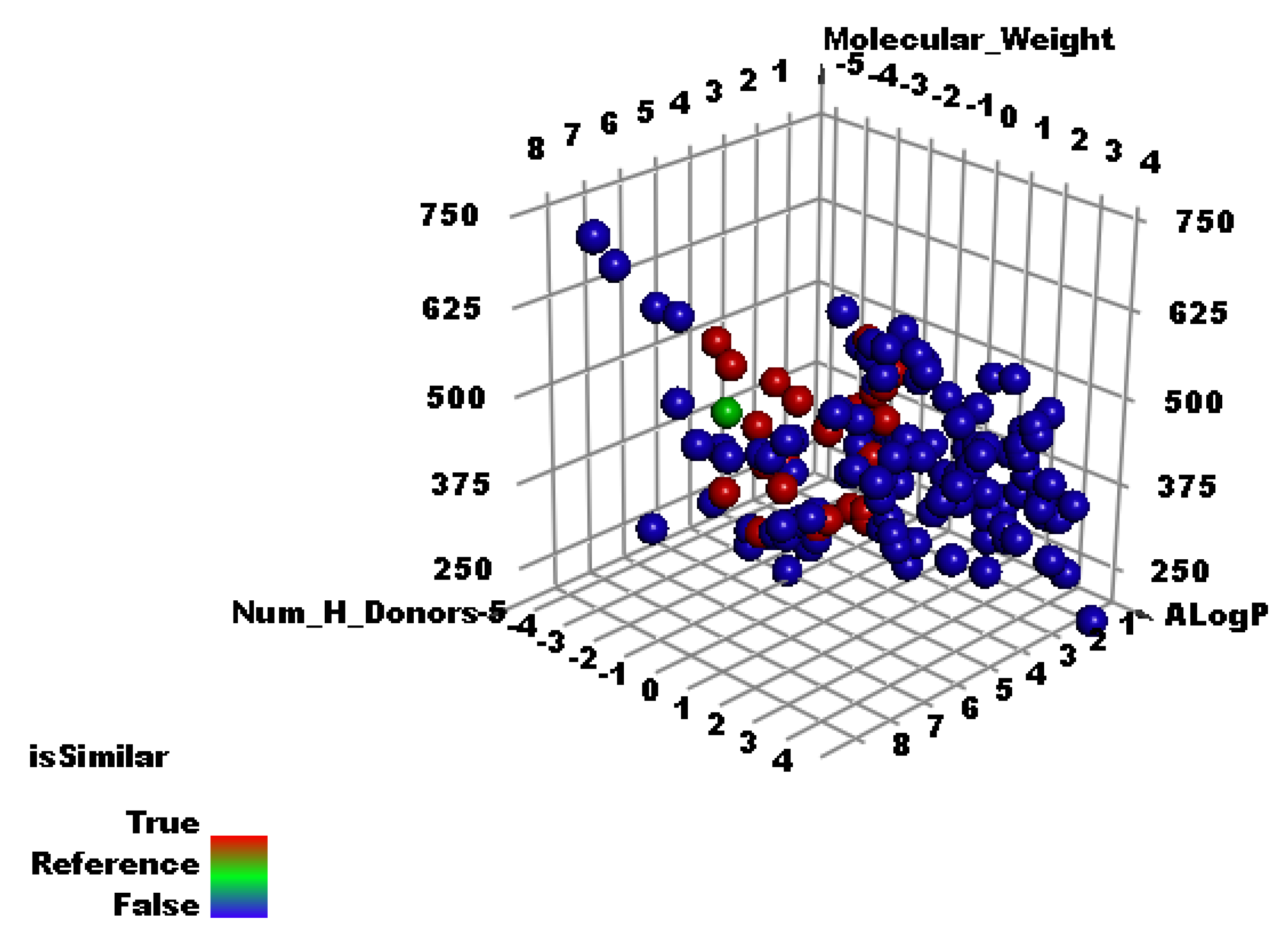

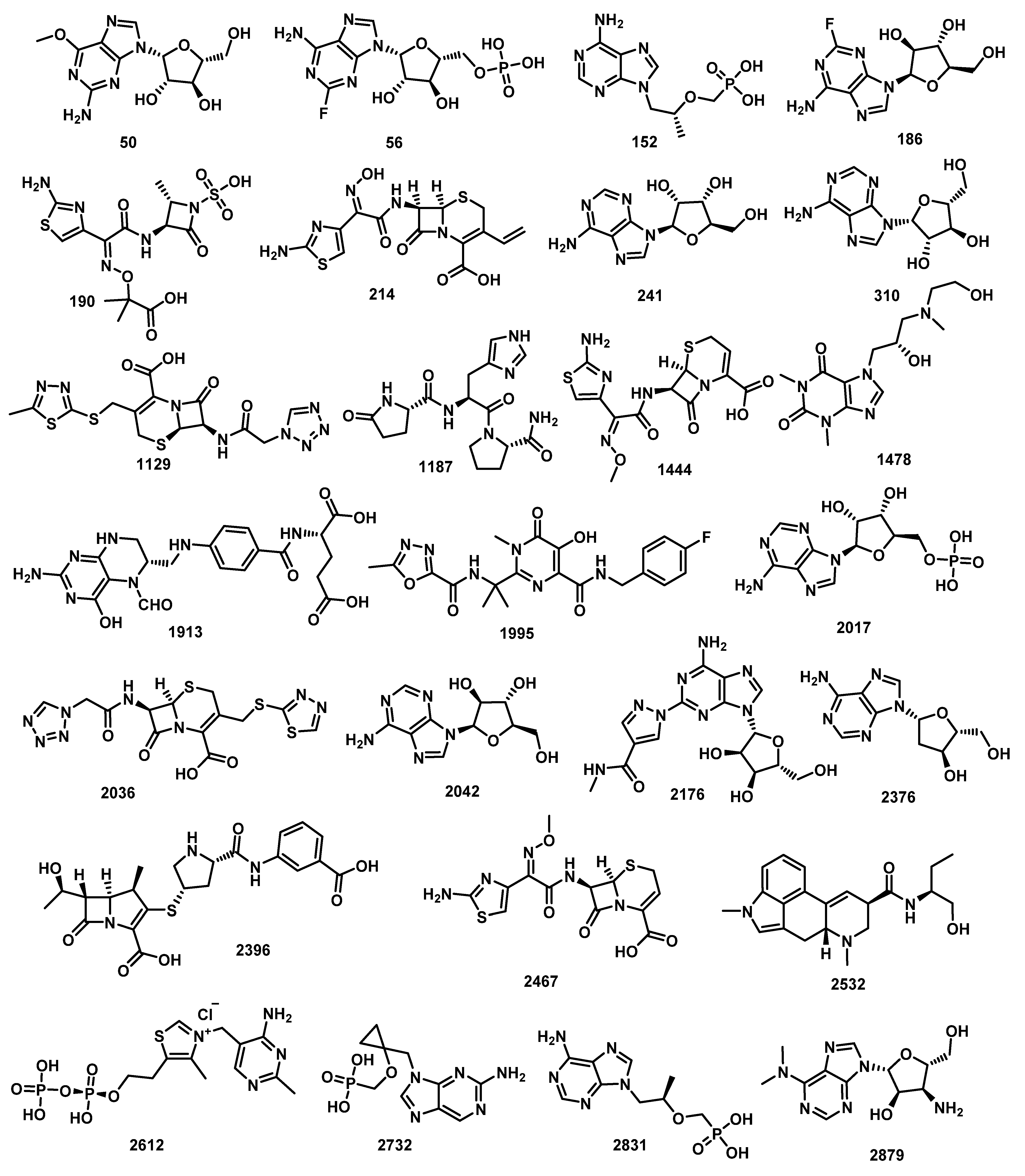

2.2. Molecular Similarity

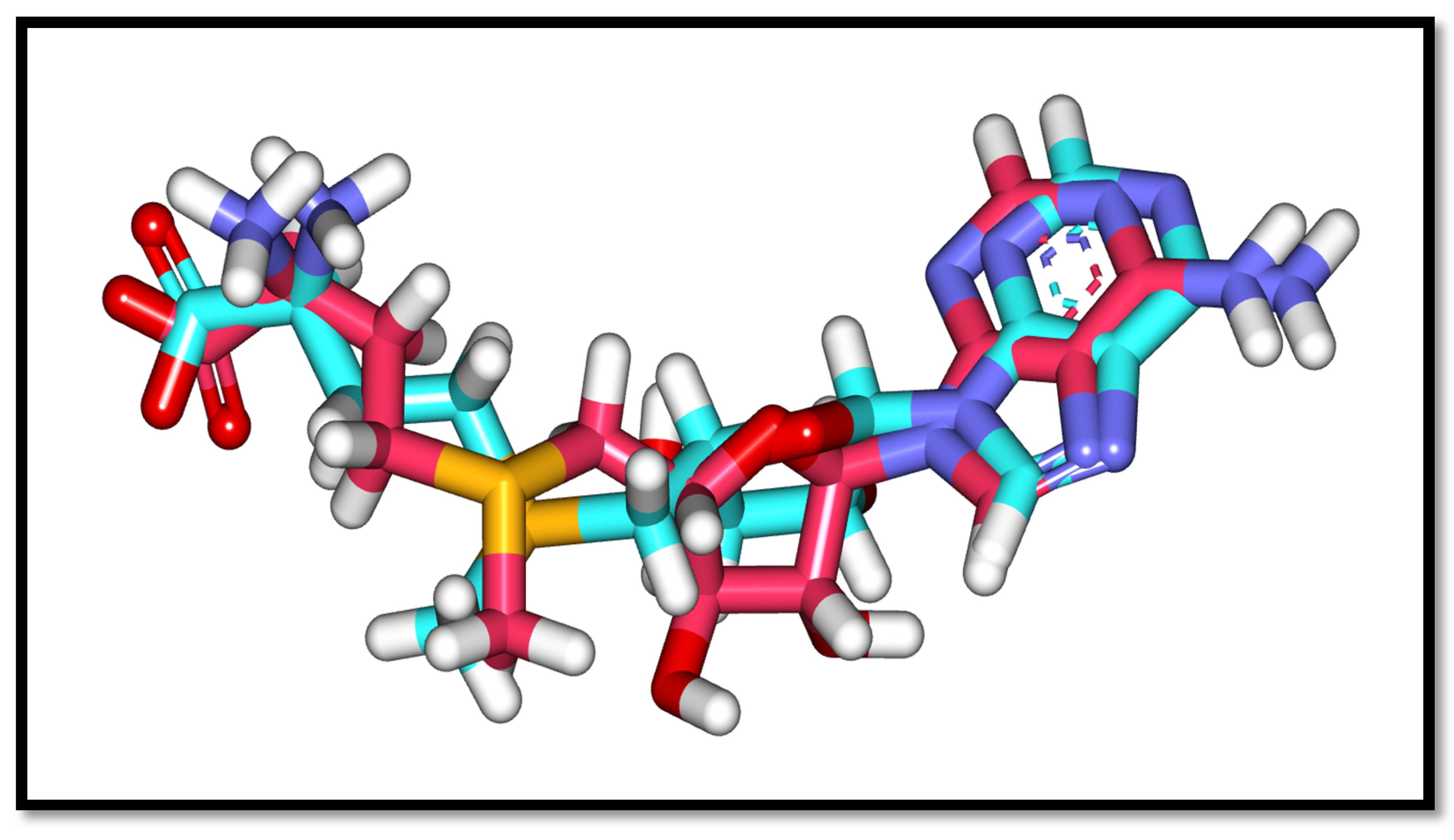

2.3. Docking Studies

2.4. Molecular Dynamic Simulation

2.5. Molecular Mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MM-PBSA) Studies

3. Method

3.1. Molecular Similarity Detection

3.2. Fingerprint Studies

3.3. Docking Studies

3.4. Molecular Dynamics Simulation

3.5. MM-PBSA Studies

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

References

- WHO. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 19 January 2022).

- Wang, Q.; Yang, L.; Jin, H.; Lin, L. Vaccination against COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis of acceptability and its predictors. Prev. Med. 2021, 150, 106694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, H.S.; Shan, H.; Dahoun, T.; Vogel, H.; Yuan, S. Advancing drug discovery via artificial intelligence. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 40, 592–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pushpakom, S.; Iorio, F.; Eyers, P.A.; Escott, K.J.; Hopper, S.; Wells, A.; Doig, A.; Guilliams, T.; Latimer, J.; McNamee, C. Drug repurposing: Progress, challenges and recommendations. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019, 18, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleire, L.; Førde, H.E.; Netland, I.A.; Leiss, L.; Skeie, B.S.; Enger, P.Ø. Drug repurposing in cancer. Pharmacol. Res. 2017, 124, 74–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, T.U.; Parida, S.; Lingaraju, M.C.; Kesavan, M.; Kumar, D.; Singh, R.K. Drug repurposing approach to fight COVID-19. Pharmacol. Rep. 2020, 72, 1479–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, J.; Bang, M. Anti-inflammatory strategies for schizophrenia: A review of evidence for therapeutic applications and drug repurposing. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 2020, 18, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Konreddy, A.K.; Rani, G.U.; Lee, K.; Choi, Y. Recent drug-repurposing-driven advances in the discovery of novel antibiotics. Curr. Med. Chem. 2019, 26, 5363–5388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirley, D.-A.; Sharma, I.; Warren, C.A.; Moonah, S. Drug repurposing of the alcohol abuse medication disulfiram as an anti-parasitic agent. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, J.; Mohan, M.; Byrareddy, S.N. Drug repurposing approaches to combating viral infections. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westbrook, J.D.; Burley, S.K. How structural biologists and the Protein Data Bank contributed to recent FDA new drug approvals. Structure 2019, 27, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grimme, S.; Schreiner, P.R. Computational chemistry: The fate of current methods and future challenges. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 4170–4176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, S.; Banerjee, S.; Singh, S.; Qureshi, I.A.; Gayen, S.; Jha, T. First structure–activity relationship analysis of SARS-CoV-2 virus main protease (Mpro) inhibitors: An endeavor on COVID-19 drug discovery. Mol. Divers. 2021, 25, 1827–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranjan, S.; Devarapalli, R.; Kundu, S.; Saha, S.; Deolka, S.; Vangala, V.R.; Reddy, C.M. Isomorphism: Molecular similarity to crystal structure similarity’in multicomponent forms of analgesic drugs tolfenamic and mefenamic acid. IUCrJ 2020, 7, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Baidya, A.T.; Ghosh, K.; Amin, S.A.; Adhikari, N.; Nirmal, J.; Jha, T.; Gayen, S. In silico modelling, identification of crucial molecular fingerprints, and prediction of new possible substrates of human organic cationic transporters 1 and 2. New J. Chem. 2020, 44, 4129–4143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y. Support vector regression-based QSAR models for prediction of antioxidant activity of phenolic compounds. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 8806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Idris, M.O.; Yekeen, A.A.; Alakanse, O.S.; Durojaye, O.A. Computer-aided screening for potential TMPRSS2 inhibitors: A combination of pharmacophore modeling, molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation approaches. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021, 39, 5638–5656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Li, M. A new computer model for evaluating the selective binding affinity of phenylalkylamines to T-Type Ca2+ channels. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eissa, I.H.; Ibrahim, M.K.; Metwaly, A.M.; Belal, A.; Mehany, A.B.; Abdelhady, A.A.; Elhendawy, M.A.; Radwan, M.M.; ElSohly, M.A.; Mahdy, H.A. Design, molecular docking, in vitro, and in vivo studies of new quinazolin-4 (3H)-ones as VEGFR-2 inhibitors with potential activity against hepatocellular carcinoma. Bioorgan. Chem. 2021, 107, 104532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhanzhaxina, A.; Suleimen, Y.; Metwaly, A.M.; Eissa, I.H.; Elkaeed, E.B.; Suleimen, R.; Ishmuratova, M.; Akatan, K.; Luyten, W. In vitro and in silico cytotoxic and antibacterial activities of a diterpene from cousinia alata schrenk. J. Chem. 2021, 2021, 5542455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalmakhanbetova, R.; Elkaeed, E.B.; Eissa, I.H.; Metwaly, A.M.; Suleimen, Y.M. Synthesis and molecular docking of some grossgemin amino derivatives as tubulin inhibitors targeting colchicine binding site. J. Chem. 2021, 2021, 5586515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Adl, K.; El-Helby, A.-G.A.; Ayyad, R.R.; Mahdy, H.A.; Khalifa, M.M.; Elnagar, H.A.; Mehany, A.B.; Metwaly, A.M.; Elhendawy, M.A.; Radwan, M.M. Design, synthesis, and anti-proliferative evaluation of new quinazolin-4 (3H)-ones as potential VEGFR-2 inhibitors. Biorgan. Med. Chem. 2021, 29, 115872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imieje, V.O.; Zaki, A.A.; Metwaly, A.M.; Eissa, I.H.; Elkaeed, E.B.; Ali, Z.; Khan, I.A.; Falodun, A. Antileishmanial derivatives of humulene from Asteriscus hierochunticus with in silico tubulin inhibition potential. Rec. Nat. Prod. 2021, 16, 150–171. [Google Scholar]

- Rafi, M.O.; Al-Khafaji, K.; Tok, T.T.; Rahman, M.S. Computer-based identification of potential compounds from Salviae miltiorrhizae against Neirisaral adhesion A regulatory protein. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parmar, D.R.; Soni, J.Y.; Guduru, R.; Rayani, R.H.; Kusurkar, R.V.; Vala, A.G.; Talukdar, S.N.; Eissa, I.H.; Metwaly, A.M.; Khalil, A. Discovery of new anticancer thiourea-azetidine hybrids: Design, synthesis, in vitro antiproliferative, SAR, in silico molecular docking against VEGFR-2, ADMET, toxicity, and DFT studies. Biorgan. Chem. 2021, 115, 105206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Adl, K.; Sakr, H.M.; Yousef, R.G.; Mehany, A.B.; Metwaly, A.M.; Elhendawy, M.A.; Radwan, M.M.; ElSohly, M.A.; Abulkhair, H.S.; Eissa, I.H. Discovery of new quinoxaline-2 (1H)-one-based anticancer agents targeting VEGFR-2 as inhibitors: Design, synthesis, and anti-proliferative evaluation. Biorgan. Chem. 2021, 114, 105105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleimen, Y.M.; Metwaly, A.M.; Mostafa, A.E.; Elkaeed, E.B.; Liu, H.-W.; Basnet, B.B.; Suleimen, R.N.; Ishmuratova, M.Y.; Turdybekov, K.M.; Van Hecke, K. Isolation, Crystal Structure, and In Silico Aromatase Inhibition Activity of Ergosta-5, 22-dien-3β-ol from the Fungus Gyromitra esculenta. J. Chem. 2021, 2021, 5529786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, R.G.; Sakr, H.M.; Eissa, I.H.; Mehany, A.B.; Metwaly, A.M.; Elhendawy, M.A.; Radwan, M.M.; ElSohly, M.A.; Abulkhair, H.S.; El-Adl, K. New quinoxaline-2 (1 H)-ones as potential VEGFR-2 inhibitors: Design, synthesis, molecular docking, ADMET profile and anti-proliferative evaluations. New J. Chem. 2021, 45, 16949–16964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, H.H.; Alotaibi, S.H.; Trawneh, A.H.; Metwaly, A.M.; Eissa, I.H. Anticancer activity, spectroscopic and molecular docking of some new synthesized sugar hydrazones, Arylidene and α-Aminophosphonate derivatives. Arab. J. Chem. 2021, 14, 103348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, A.; Farooqui, A.; Khanam, A.; Sharma, S.; Mahfooz, S.; Shamim, A.; Akhter, F.; Alatar, A.A.; Faisal, M.; Ahmad, S. Physicochemical characterization of C-phycocyanin from Plectonema sp. and elucidation of its bioactive potential through in silico approach. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2021, 67, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.O.; El Ashry, E.S.H.; Khalid, A.; Amer, M.R.; Metwaly, A.M.; Eissa, I.H.; Elkaeed, E.B.; Elshobaky, A.; Hafez, E.E. Expression, Purification, and Comparative Inhibition of Helicobacter pylori Urease by Regio-Selectively Alkylated Benzimidazole 2-Thione Derivatives. Molecules 2022, 27, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imieje, V.O.; Zaki, A.A.; Metwaly, A.M.; Mostafa, A.E.; Elkaeed, E.B.; Falodun, A. Comprehensive In Silico Screening of the Antiviral Potentialities of a New Humulene Glucoside from Asteriscus hierochunticus against SARS-CoV-2. J. Chem. 2021, 2021, 5541876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Demerdash, A.; Metwaly, A.M.; Hassan, A.; El-Aziz, A.; Mohamed, T.; Elkaeed, E.B.; Eissa, I.H.; Arafa, R.K.; Stockand, J.D. Comprehensive virtual screening of the antiviral potentialities of marine polycyclic guanidine alkaloids against SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19). Biomolecules 2021, 11, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalmakhanbetova, R.I.; Suleimen, Y.M.; Oyama, M.; Elkaeed, E.B.; Eissa, I.; Suleimen, R.N.; Metwaly, A.M.; Ishmuratova, M.Y. Isolation and In Silico Anti-COVID-19 Main Protease (Mpro) Activities of Flavonoids and a Sesquiterpene Lactone from Artemisia sublessingiana. J. Chem. 2021, 2021, 5547013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleimen, Y.M.; Jose, R.A.; Suleimen, R.N.; Arenz, C.; Ishmuratova, M.; Toppet, S.; Dehaen, W.; Alsfouk, A.A.; Elkaeed, E.B.; Eissa, I.H.; et al. Isolation and In Silico Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Papain-Like Protease Potentialities of Two Rare 2-Phenoxychromone Derivatives from Artemisia spp. Molecules 2022, 27, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesawy, M.S.; Abdallah, A.E.; Taghour, M.S.; Elkaeed, E.B.; H Eissa, I.; Metwaly, A.M. In Silico Studies of Some Isoflavonoids as Potential Candidates against COVID-19 Targeting Human ACE2 (hACE2) and Viral Main Protease (Mpro). Molecules 2021, 26, 2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eissa, I.H.; Khalifa, M.M.; Elkaeed, E.B.; Hafez, E.E.; Alsfouk, A.A.; Metwaly, A.M. In Silico Exploration of Potential Natural Inhibitors against SARS-Cov-2 nsp10. Molecules 2021, 26, 6151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesawy, M.S.; Elkaeed, E.B.; Alsfouk, A.A.; Metwaly, A.M.; Eissa, I. In Silico Screening of Semi-Synthesized Compounds as Potential Inhibitors for SARS-CoV-2 Papain-like Protease: Pharmacophoric Features, Molecular Docking, ADMET, Toxicity and DFT Studies. Molecules 2021, 26, 6593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA-Approved Drug Library. Available online: https://www.selleckchem.com/screening/fda-approved-drug-library.html (accessed on 19 November 2021).

- Briem, H.; Kuntz, I.D. Molecular similarity based on DOCK-generated fingerprints. J. Med. Chem. 1996, 39, 3401–3408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, D.; Garcia-Serna, R.; Mestres, J. Ligand-based approaches to in silico pharmacology. In Chemoinformatics and Computational Chemical Biology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 489–502. [Google Scholar]

- Hassell, A.M.; An, G.; Bledsoe, R.K.; Bynum, J.M.; Carter, H.L.; Deng, S.-J.; Gampe, R.T.; Grisard, T.E.; Madauss, K.P.; Nolte, R.T. Crystallization of protein–ligand complexes. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2007, 63, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.; He, Q.-X.; Wang, J.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Y.-Q.; Lin, Z.-H. In silico design of novel benzohydroxamate-based compounds as inhibitors of histone deacetylase 6 based on 3D-QSAR, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics simulations. New J. Chem. 2020, 44, 21201–21210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ieritano, C.; Campbell, J.L.; Hopkins, W.S. Predicting differential ion mobility behaviour in silico using machine learning. Analyst 2021, 146, 4737–4743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taha, M.; Ismail, N.H.; Ali, M.; Rashid, U.; Imran, S.; Uddin, N.; Khan, K.M. Molecular hybridization conceded exceptionally potent quinolinyl-oxadiazole hybrids through phenyl linked thiosemicarbazide antileishmanial scaffolds: In silico validation and SAR studies. Biorgan. Chem. 2017, 71, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opo, F.A.D.M.; Rahman, M.M.; Ahammad, F.; Ahmed, I.; Bhuiyan, M.A.; Asiri, A.M. Structure based pharmacophore modeling, virtual screening, molecular docking and ADMET approaches for identification of natural anti-cancer agents targeting XIAP protein. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durant, J.L.; Leland, B.A.; Henry, D.R.; Nourse, J.G. Reoptimization of MDL keys for use in drug discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2002, 42, 1273–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maggiora, G.; Vogt, M.; Stumpfe, D.; Bajorath, J. Molecular similarity in medicinal chemistry: Miniperspective. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 3186–3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, A.; Glen, R.C. Molecular similarity: A key technique in molecular informatics. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2004, 2, 3204–3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, K.M.; Enoch, S.J.; Ezendam, J.; Sewald, K.; Roggen, E.L.; Cochrane, S. An adverse outcome pathway for sensitization of the respiratory tract by low-molecular-weight chemicals: Building evidence to support the utility of in vitro and in silico methods in a regulatory context. Appl. Vitr. Toxicol. 2017, 3, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Altamash, T.; Amhamed, A.; Aparicio, S.; Atilhan, M. Effect of hydrogen bond donors and acceptors on CO2 absorption by deep eutectic solvents. Processes 2020, 8, 1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Tian, Y.; Wang, W.; Gu, S.; Ju, X.; Liu, G. In silico studies of diarylpyridine derivatives as novel HIV-1 NNRTIs using docking-based 3D-QSAR, molecular dynamics, and pharmacophore modeling approaches. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 40529–40543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Turchi, M.; Cai, Q.; Lian, G. An evaluation of in-silico methods for predicting solute partition in multiphase complex fluids—A case study of octanol/water partition coefficient. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2019, 197, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escamilla-Gutiérrez, A.; Ribas-Aparicio, R.M.; Córdova-Espinoza, M.G.; Castelán-Vega, J.A. In silico strategies for modeling RNA aptamers and predicting binding sites of their molecular targets. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 2021, 40, 798–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaushik, A.C.; Kumar, A.; Bharadwaj, S.; Chaudhary, R.; Sahi, S. Ligand-Based Approach for In-silico Drug Designing. In Bioinformatics Techniques for Drug Discovery; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Ren, J.-X.; Ma, J.-X.; Ding, L. Development of an in silico prediction model for chemical-induced urinary tract toxicity by using naïve Bayes classifier. Mol. Divers. 2019, 23, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheridan, R.P.; Kearsley, S.K. Why do we need so many chemical similarity search methods? Drug Discov. Today 2002, 7, 903–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MOE. MOE User Guide. Available online: https://www.easa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/dfu/B01.UG_.CAO_.00024-008%20User%20Guide%20for%20Maintenance%20Organisation%20Exposition.PDF (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Rosas-Lemus, M.; Minasov, G.; Shuvalova, L.; Inniss, N.L.; Kiryukhina, O.; Brunzelle, J.; Satchell, K.J. High-resolution structures of the SARS-CoV-2 2′-O-methyltransferase reveal strategies for structure-based inhibitor design. Sci. Signal. 2020, 13, eabe1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, S.F.; Fernandes, P.A.; Ramos, M.J. Protein–ligand docking: Current status and future challenges. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 2006, 65, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollingsworth, S.A.; Dror, R.O. Molecular dynamics simulation for all. Neuron 2018, 99, 1129–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, X.; Shi, D.; Zhou, S.; Liu, H.; Liu, H.; Yao, X. Molecular dynamics simulations and novel drug discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2018, 13, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzmanic, A.; Zagrovic, B. Determination of ensemble-average pairwise root mean-square deviation from experimental B-factors. Biophys. J. 2010, 98, 861–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Protein Data Bank. 2021. Available online: https://www.rcsb.org/structure/4OW0 (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Jo, S.; Kim, T.; Iyer, V.G.; Im, W. CHARMM-GUI: A web-based graphical user interface for CHARMM. J. Comput. Chem. 2008, 29, 1859–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, B.R.; Brooks, C.L., III.; Mackerell, A.D., Jr.; Nilsson, L.; Petrella, R.J.; Roux, B.; Won, Y.; Archontis, G.; Bartels, C.; Boresch, S.; et al. CHARMM: The biomolecular simulation program. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 1545–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Cheng, X.; Swails, J.M.; Yeom, M.S.; Eastman, P.K.; Lemkul, J.A.; Wei, S.; Buckner, J.; Jeong, J.C.; Qi, Y.; et al. CHARMM-GUI Input Generator for NAMD, GROMACS, AMBER, OpenMM, and CHARMM/OpenMM Simulations Using the CHARMM36 Additive Force Field. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2016, 12, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Best, R.B.; Zhu, X.; Shim, J.; Lopes, P.E.; Mittal, J.; Feig, M.; Mackerell, A.D., Jr. Optimization of the additive CHARMM all-atom protein force field targeting improved sampling of the backbone phi, psi and side-chain chi(1) and chi(2) dihedral angles. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012, 8, 3257–3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Phillips, J.C.; Braun, R.; Wang, W.; Gumbart, J.; Tajkhorshid, E.; Villa, E.; Chipot, C.; Skeel, R.D.; Kale, L.; Schulten, K. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem. 2005, 26, 1781–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Comp. | Similarity | SA | SB | SC | Comp. | Similarity | SA | SB | SC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAM | 1 | 237 | 0 | 0 | 1670 | 0.57 | 257 | 214 | −20 |

| 4 | 0.497396 | 191 | 147 | 46 | 1694 | 0.5 | 191 | 145 | 46 |

| 42 | 0.597 | 138 | −6 | 99 | 1737 | 0.506944 | 146 | 51 | 91 |

| 50 | 0.651 | 157 | 4 | 80 | 1740 | 0.491582 | 146 | 60 | 91 |

| 51 | 0.581 | 137 | −1 | 100 | 1756 | 0.506912 | 220 | 197 | 17 |

| 56 | 0.665 | 171 | 20 | 66 | 1761 | 0.523404 | 246 | 233 | −9 |

| 58 | 0.491525 | 174 | 117 | 63 | 1766 | 0.54321 | 176 | 87 | 61 |

| 74 | 0.495652 | 171 | 108 | 66 | 1778 | 0.511299 | 181 | 117 | 56 |

| 91 | 0.496241 | 132 | 29 | 105 | 1792 | 0.50211 | 238 | 237 | −1 |

| 113 | 0.485714 | 170 | 113 | 67 | 1793 | 0.494792 | 285 | 339 | −48 |

| 130 | 0.490463 | 180 | 130 | 57 | 1802 | 0.56 | 237 | 186 | 0 |

| 152 | 0.624 | 143 | −8 | 94 | 1805 | 0.501433 | 175 | 112 | 62 |

| 158 | 0.5 | 189 | 141 | 48 | 1818 | 0.508475 | 210 | 176 | 27 |

| 186 | 0.644 | 150 | −4 | 87 | 1860 | 0.494024 | 124 | 14 | 113 |

| 189 | 0.5 | 122 | 7 | 115 | 1886 | 0.493478 | 227 | 223 | 10 |

| 190 | 0.492958 | 175 | 118 | 62 | 1911 | 0.490683 | 158 | 85 | 79 |

| 214 | 0.515723 | 164 | 81 | 73 | 1913 | 0.494033 | 207 | 182 | 30 |

| 241 | 0.717 | 160 | −14 | 77 | 1917 | 0.929 | 235 | 16 | 2 |

| 251 | 0.490956 | 190 | 150 | 47 | 1919 | 0.488701 | 173 | 117 | 64 |

| 272 | 0.508403 | 121 | 1 | 116 | 1927 | 0.489796 | 216 | 204 | 21 |

| 281 | 0.510806 | 260 | 272 | −23 | 1928 | 0.488636 | 215 | 203 | 22 |

| 304 | 0.488938 | 221 | 215 | 16 | 1932 | 0.50303 | 166 | 93 | 71 |

| 310 | 0.717 | 160 | −14 | 77 | 1949 | 0.505464 | 185 | 129 | 52 |

| 322 | 0.486154 | 158 | 88 | 79 | 1960 | 0.48995 | 195 | 161 | 42 |

| 380 | 0.514563 | 159 | 72 | 78 | 1993 | 0.522599 | 185 | 117 | 52 |

| 390 | 0.52862 | 157 | 60 | 80 | 1995 | 0.488998 | 200 | 172 | 37 |

| 404 | 0.535211 | 190 | 118 | 47 | 2002 | 0.49 | 147 | 63 | 90 |

| 428 | 0.498623 | 181 | 126 | 56 | 2009 | 0.511364 | 135 | 27 | 102 |

| 446 | 0.50641 | 158 | 75 | 79 | 2017 | 0.663 | 193 | 54 | 44 |

| 458 | 0.488136 | 144 | 58 | 93 | 2023 | 0.627 | 168 | 31 | 69 |

| 461 | 0.507837 | 162 | 82 | 75 | 2024 | 0.527378 | 183 | 110 | 54 |

| 470 | 0.491803 | 180 | 129 | 57 | 2031 | 0.57 | 147 | 21 | 90 |

| 515 | 0.501493 | 168 | 98 | 69 | 2036 | 0.487179 | 171 | 114 | 66 |

| 516 | 0.561 | 165 | 57 | 72 | 2042 | 0.664 | 172 | 22 | 65 |

| 539 | 0.519149 | 122 | −2 | 115 | 2174 | 0.488318 | 209 | 191 | 28 |

| 562 | 0.489496 | 233 | 239 | 4 | 2176 | 0.661 | 199 | 64 | 38 |

| 573 | 0.491049 | 192 | 154 | 45 | 2232 | 0.642 | 265 | 176 | −28 |

| 598 | 0.510504 | 243 | 239 | −6 | 2233 | 0.701 | 202 | 51 | 35 |

| 659 | 0.540816 | 159 | 57 | 78 | 2256 | 0.543662 | 193 | 118 | 44 |

| 663 | 0.492537 | 198 | 165 | 39 | 2268 | 0.538776 | 132 | 8 | 105 |

| 672 | 0.48913 | 135 | 39 | 102 | 2303 | 0.503597 | 210 | 180 | 27 |

| 679 | 0.501661 | 151 | 64 | 86 | 2306 | 0.494737 | 188 | 143 | 49 |

| 683 | 0.488798 | 240 | 254 | −3 | 2333 | 0.494595 | 183 | 133 | 54 |

| 711 | 0.566 | 137 | 5 | 100 | 2376 | 0.643 | 160 | 12 | 77 |

| 723 | 0.561 | 142 | 16 | 95 | 2396 | 0.491525 | 232 | 235 | 5 |

| 736 | 0.5 | 169 | 101 | 68 | 2410 | 0.513587 | 189 | 131 | 48 |

| 753 | 0.504425 | 228 | 215 | 9 | 2437 | 0.489189 | 181 | 133 | 56 |

| 771 | 0.486076 | 192 | 158 | 45 | 2467 | 0.503086 | 163 | 87 | 74 |

| 772 | 0.489703 | 214 | 200 | 23 | 2483 | 0.539185 | 172 | 82 | 65 |

| 781 | 0.487603 | 177 | 126 | 60 | 2488 | 0.542274 | 186 | 106 | 51 |

| 816 | 0.497297 | 184 | 133 | 53 | 2496 | 0.522099 | 189 | 125 | 48 |

| 821 | 0.493369 | 186 | 140 | 51 | 2501 | 0.496711 | 151 | 67 | 86 |

| 824 | 0.492958 | 175 | 118 | 62 | 2530 | 0.495468 | 164 | 94 | 73 |

| 874 | 0.553531 | 243 | 202 | −6 | 2532 | 0.491667 | 236 | 243 | 1 |

| 919 | 0.504032 | 125 | 11 | 112 | 2538 | 0.501887 | 133 | 28 | 104 |

| 1129 | 0.5 | 186 | 135 | 51 | 2581 | 0.486141 | 228 | 232 | 9 |

| 1179 | 0.488701 | 173 | 117 | 64 | 2585 | 0.524 | 131 | 13 | 106 |

| 1185 | 0.571 | 348 | 372 | −111 | 2612 | 0.504792 | 158 | 76 | 79 |

| 1187 | 0.510989 | 186 | 127 | 51 | 2618 | 0.489028 | 156 | 82 | 81 |

| 1249 | 0.497222 | 179 | 123 | 58 | 2717 | 0.555556 | 190 | 105 | 47 |

| 1274 | 0.502 | 251 | 263 | −14 | 2732 | 0.571 | 140 | 8 | 97 |

| 1315 | 0.514368 | 179 | 111 | 58 | 2751 | 0.490667 | 184 | 138 | 53 |

| 1391 | 0.494005 | 206 | 180 | 31 | 2786 | 0.562 | 140 | 12 | 97 |

| 1401 | 0.490446 | 154 | 77 | 83 | 2831 | 0.603 | 155 | 20 | 82 |

| 1411 | 0.491803 | 180 | 129 | 57 | 2853 | 0.52214 | 283 | 305 | −46 |

| 1444 | 0.495238 | 156 | 78 | 81 | 2861 | 0.522822 | 252 | 245 | −15 |

| 1458 | 0.5 | 166 | 95 | 71 | 2876 | 0.635 | 223 | 114 | 14 |

| 1478 | 0.558074 | 197 | 116 | 40 | 2877 | 0.519651 | 238 | 221 | −1 |

| 1587 | 0.485849 | 206 | 187 | 31 | 2879 | 0.7 | 168 | 3 | 69 |

| 1595 | 0.547414 | 127 | −5 | 110 | 2884 | 0.486425 | 215 | 205 | 22 |

| 1604 | 0.489189 | 181 | 133 | 56 | 2894 | 0.494279 | 216 | 200 | 21 |

| 1642 | 0.603 | 225 | 136 | 12 | 2907 | 0.488889 | 220 | 213 | 17 |

| 1651 | 0.586 | 309 | 290 | −72 | 2918 | 0.490028 | 172 | 114 | 65 |

| 1662 | 0.507576 | 134 | 27 | 103 | 2959 | 0.489362 | 230 | 233 | 7 |

| Comp. | ALog p | MW | HBA | HBD | Rotatable Bonds | Rings | Aromatic Rings | MFPSA | Minimum Distance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAM | −4.25 | 399.45 | 9 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 0.483 | 0 |

| 50 | −1.38 | 297.27 | 9 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 0.508 | 0.768 |

| 56 | −1.38 | 365.21 | 11 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 0.602 | 0.738 |

| 152 | −0.77 | 287.21 | 8 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 0.502 | 0.836 |

| 186 | −1.31 | 285.23 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 0.52 | 0.884 |

| 190 | −1.04 | 435.43 | 11 | 4 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 0.576 | 0.874 |

| 214 | −0.17 | 395.41 | 9 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 0.577 | 0.91 |

| 241 | −1.88 | 267.24 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 0.539 | 0.877 |

| 310 | −1.88 | 267.24 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 0.539 | 0.877 |

| 1129 | −2.81 | 476.49 | 11 | 1 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 0.624 | 0.896 |

| 1187 | −2.39 | 362.38 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 0.414 | 0.801 |

| 1444 | −0.64 | 383.4 | 9 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 0.56 | 0.874 |

| 1478 | −3.74 | 434.45 | 9 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 0.316 | 0.478 |

| 1913 | −3.05 | 511.5 | 12 | 5 | 9 | 3 | 2 | 0.545 | 0.67 |

| 1995 | −0.99 | 482.51 | 7 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 0.442 | 0.796 |

| 2017 | −2.16 | 365.24 | 12 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 0.655 | 0.856 |

| 2036 | −1.59 | 440.48 | 11 | 2 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 0.594 | 0.781 |

| 2042 | −2.09 | 285.26 | 9 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 0.589 | 0.874 |

| 2176 | −1.93 | 390.35 | 10 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 0.491 | 0.838 |

| 2376 | −1.32 | 269.26 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 0.54 | 0.917 |

| 2396 | −4.6 | 497.5 | 9 | 4 | 7 | 4 | 1 | 0.484 | 0.705 |

| 2467 | −2.12 | 405.39 | 9 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 0.628 | 0.87 |

| 2532 | −0.73 | 469.53 | 7 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 0.266 | 0.909 |

| 2612 | −1.98 | 460.77 | 10 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 0.572 | 0.594 |

| 2732 | −0.82 | 299.22 | 8 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 0.504 | 0.752 |

| 2831 | −0.98 | 305.23 | 9 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 0.55 | 0.76 |

| 2879 | −1.26 | 294.31 | 8 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 0.395 | 0.846 |

| Comp. | Name | ΔG [kcal/mol] |

|---|---|---|

| SAM | S-Adenosylmethionine | −21.52 |

| 50 | Arranon (Nelarabine) | −13.84 |

| 56 | Fludara (Fludarabine) | −15.53 |

| 152 | Tenofovir (PMPA) | −13.58 |

| 186 | Fludarabine | −14.19 |

| 190 | Azactam (aztreonam) | −14.88 |

| 214 | Cefdinir (cefdinir) | −15.41 |

| 241 | Adenosine | −14.09 |

| 310 | VIRA-A (vidarabine) | −14.10 |

| 1129 | Cefazolin | −16.66 |

| 1187 | Protirelin | −18.68 |

| 1444 | Ceftizoxime | −10.99 |

| 1478 | Xanthinol Nicotinate | −16.19 |

| 1913 | Calcium folinate | −19.09 |

| 1995 | Raltegravir | −21.07 |

| 2017 | Adenosine 5′-monophosphate | −15.34 |

| 2036 | Ceftezole | −15.21 |

| 2042 | Vidarabine | −13.41 |

| 2176 | Regadenoson | −18.54 |

| 2376 | 2′-Deoxyadenosine | −13.16 |

| 2396 | Ertapenem | −20.73 |

| 2467 | Ceftizoxime | −13.63 |

| 2532 | Methylergometrine | −20.46 |

| 2612 | Thiamine pyrophosphate hydrochloride | −18.03 |

| 2732 | Besifovir | −13.47 |

| 2831 | Tenofovir | −14.36 |

| 2879 | Puromycin aminonucleoside | −15.33 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Eissa, I.H.; Alesawy, M.S.; Saleh, A.M.; Elkaeed, E.B.; Alsfouk, B.A.; El-Attar, A.-A.M.M.; Metwaly, A.M. Ligand and Structure-Based In Silico Determination of the Most Promising SARS-CoV-2 nsp16-nsp10 2′-o-Methyltransferase Complex Inhibitors among 3009 FDA Approved Drugs. Molecules 2022, 27, 2287. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27072287

Eissa IH, Alesawy MS, Saleh AM, Elkaeed EB, Alsfouk BA, El-Attar A-AMM, Metwaly AM. Ligand and Structure-Based In Silico Determination of the Most Promising SARS-CoV-2 nsp16-nsp10 2′-o-Methyltransferase Complex Inhibitors among 3009 FDA Approved Drugs. Molecules. 2022; 27(7):2287. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27072287

Chicago/Turabian StyleEissa, Ibrahim H., Mohamed S. Alesawy, Abdulrahman M. Saleh, Eslam B. Elkaeed, Bshra A. Alsfouk, Abdul-Aziz M. M. El-Attar, and Ahmed M. Metwaly. 2022. "Ligand and Structure-Based In Silico Determination of the Most Promising SARS-CoV-2 nsp16-nsp10 2′-o-Methyltransferase Complex Inhibitors among 3009 FDA Approved Drugs" Molecules 27, no. 7: 2287. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27072287

APA StyleEissa, I. H., Alesawy, M. S., Saleh, A. M., Elkaeed, E. B., Alsfouk, B. A., El-Attar, A.-A. M. M., & Metwaly, A. M. (2022). Ligand and Structure-Based In Silico Determination of the Most Promising SARS-CoV-2 nsp16-nsp10 2′-o-Methyltransferase Complex Inhibitors among 3009 FDA Approved Drugs. Molecules, 27(7), 2287. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27072287