Abstract

The understanding that zidovudine (ZDV or azidothymidine, AZT) inhibits the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) of SARS-CoV-2 and that chalcogen atoms can increase the bioactivity and reduce the toxicity of AZT has directed our search for the discovery of novel potential anti-coronavirus compounds. Here, the antiviral activity of selenium and tellurium containing AZT derivatives in human type II pneumocytes cell model (Calu-3) and monkey kidney cells (Vero E6) infected with SARS-CoV-2, and their toxic effects on these cells, was evaluated. Cell viability analysis revealed that organoselenium (R3a–R3e) showed lower cytotoxicity than organotellurium (R3f, R3n–R3q), with CC50 ≥ 100 µM. The R3b and R3e were particularly noteworthy for inhibiting viral replication in both cell models and showed better selectivity index. In Vero E6, the EC50 values for R3b and R3e were 2.97 ± 0.62 µM and 1.99 ± 0.42 µM, respectively, while in Calu-3, concentrations of 3.82 ± 1.42 µM and 1.92 ± 0.43 µM (24 h treatment) and 1.33 ± 0.35 µM and 2.31 ± 0.54 µM (48 h) were observed, respectively. The molecular docking calculations were carried out to main protease (Mpro), papain-like protease (PLpro), and RdRp following non-competitive, competitive, and allosteric inhibitory approaches. The in silico results suggested that the organoselenium is a potential non-competitive inhibitor of RdRp, interacting in the allosteric cavity located in the palm region. Overall, the cell-based results indicated that the chalcogen-zidovudine derivatives were more potent than AZT in inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 replication and that the compounds R3b and R3e play an important inhibitory role, expanding the knowledge about the promising therapeutic capacity of organoselenium against COVID-19.

1. Introduction

COVID-19, caused by the highly pathogenic novel coronavirus (CoV) known as SARS-CoV-2, was characterized as a pandemic by the World Health Organization in March 2020 [1]. Since the outbreak began in December 2019, SARS-CoV-2 has spread from China to the rest of the world. Currently, it is estimated that over 770 million cases of infection have been reported since the beginning of the pandemic, and over 6.9 million deaths have been reported worldwide [2]. Globally, disease cases continue to rise, and therefore the development of effective antiviral therapies to aid severe SARS-CoV-2 infected patients is relevant [3,4].

The clinical scenario of COVID-19 is variable, and the classic symptoms are compatible with those of influenza syndromes during the initial stages of infection [5]. However, about 10–15% of symptoms progress to acute pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, cardiomyopathy, and disseminated intravascular coagulation, which pose a serious risk of mortality in these cases [6,7,8,9]. It is recognized that a progressive infection can lead to exacerbated immune and inflammatory responses [10]. Therefore, different therapeutic strategies using antivirals, antiretrovirals, antimalarials, and anti-inflammatory drugs, as well as corticosteroids, immunomodulators, or immunoglobulin therapies, have been required and repurposed for the COVID-19 treatment [11,12]. It is important to highlight that the effectiveness of vaccines has been fundamental in preventing new cases and improving the symptomatology of the disease. However, there are still significant challenges when it comes to developing specific antivirals against SARS-CoV-2 [13,14,15].

SARS-CoV-2 is a β-coronavirus belonging to the family Coronaviridae and containing a single-stranded positive polarity RNA (+ssRNA) [13,14]. The genome encodes four structural proteins, which play an important role in the assembly of virions and in the activation of the host’s immune response, and are classified as nucleocapsid (N), spike (S), membrane (M), and envelope (E) proteins, and sixteen non-structural proteins (nsp1-16) that are essential for viral transcription and replication [16,17]. The main protease (Mpro or 3CLpro), papain-like protease (PLpro), and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) are configured as non-structural proteins and have been the focus of numerous research studies and stand out as key molecules in the fight against COVID-19 [18,19,20,21,22].

The approved drugs and drugs authorized under an emergency use by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are characterized as protease inhibitors (nirmatrelvir/ritonavir), RdRp inhibitors (remdesivir and molnupiravir), inflammatory mediators (baracitinib and tocilizumab), and monoclonal antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, representing a significant advancement in the fight against this virus [23]. However, clinical studies have shown limited or nonexistent efficacy for most proposed medications, as well as it was reported various side effects [24,25]. Additionally, there is the occurrence of COVID-19 rebound effect with the treatment based on molnupiravir and nirmatrelvir/ritonavir [26]. Furthermore, the emergence of new strains that are more transmissible and have higher infectivity is referenced as another concerning factor, and thus the development of new drugs is an important strategy to broaden therapeutic targets and consequently reduce the emergence of new mutations in the virus [15]. In this context, some organochalcogenium compounds have been described in the literature as showing anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity. For instance, Mangiavacchi et al. reported the seleno-functionalization of quercetin and the corresponding anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity. The authors described that the introduction of the specific para-tolylselenyl fragment at the quercetin moiety led to a 24-fold improvement in the antiviral potency when compared with the original quercetin [27]. Additionally, at the beginning of the SARS-CoV-2 spread, it was reported the potential application of ebselen as an anti-SARS-CoV-2 agent to target the viral proteases [28,29], and recently different groups have reported novel ebselen derivatives to improve the anti-SARS-CoV-2 profile, at interacting not only with Mpro or PLpro but also with nsp14 guanine N7-methyltransferase and RdRp [30,31,32,33].

An important trend in the chemotherapy field involves the study of nucleoside analogs and the analysis of their multiple antioxidant, antitumor, antimicrobial, and antiviral properties [34,35,36,37]. Azidothymidine (AZT), also known as zidovudine (ZDV), is a synthetic nucleoside analog of thymidine that was originally synthesized as an antitumor compound but gained notable prominence due to its inhibitory activity on reverse transcriptase, an essential enzyme for HIV replication [38,39]. Interestingly, current studies have revealed that AZT has also been described as an inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) in vitro (kinetic test) [40,41]. In silico analyses have shown that the antiretroviral drug binds to the catalytic site of RdRp and impairs the functioning of the transcriptase-replicase complex responsible for the formation of new viral RNA strands [42]. However, since prolonged use of AZT has been correlated with the emergence of severe side effects due to its high toxicity [38,43], the development of analog molecules, based on AZT scaffold, has been required as a strategy for new therapies against cancer and viral infections [44,45].

Previous data from the group have demonstrated that new compounds formed by adding chalcogen atoms to the structure of commercial AZT were able to enhance the in vitro antioxidant and antitumor action of the hydride molecules [46,47]. In this context, it was reported that the presence of chalcogen in the molecule 5′-arylchalcogenyl-3-(phenylselanyl-triazoyl)-thymidine reduced the proliferative capacity of bladder cancer cells and amplified the activity of the compound [48]. Additional results revealed that in breast cancer cell line, AZT analogs containing tellurium were more effective in inhibiting tumor growth and showed lower cytotoxicity than the original antiretroviral molecule [46]. Furthermore, it was described that the organochalcogen 5′-selenothymidine (S1073) acts as an important neuroprotective agent and attenuates oxidative stress in mice with cognitive dysfunction induced by intracerebroventricular-streptozotocin (ICV-STZ) [49]. Expanding on these findings, Ecker et al. [50,51] indicated that, after selenium insertion, the compound 5′-(4-methylphenylseleno) zidovudine (SZ3) was not toxic to human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and exhibited a protective action on red blood cells. In summary, these data expand our knowledge of nucleoside analogs, reveal the multifunctional role of AZT-derivatives, and direct us towards the search for new low-toxicity chalcogen-zidovudines with potent antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2.

Thus, in the present study, human pneumocytes type II model (Calu-3) and monkey kidney cells (Vero E6) were infected with novel coronavirus, and the inhibitory capacity of organochalcogens from the chalcogen-zidovudines (5′-arylchalcogeno-3-aminothymidine derivatives, Figure 1) was evaluated against in vitro viral replication. In addition, molecular docking calculations were carried out to evaluate the capacity of these chalcogen-zidovudine derivatives to interact with the three main enzymes reported as key targets of this class of compounds (Mpro, PLpro, and RdRp). Since the experimental enzymatic assays were not conducted, it was considered non-competitive, competitive, and allosteric inhibitory mechanisms for the in silico approach for a better interpretation of the interaction between drug and target.

Figure 1.

The chemical structure for 5′-arylchalcogeno-3-aminothymidine derivatives (R3 series) and azidothymidine (AZT).

2. Results and Discussion

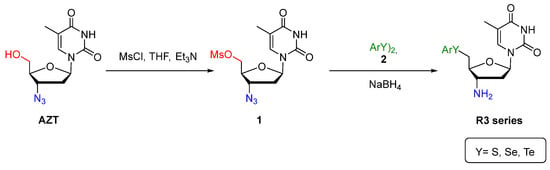

2.1. Synthesis of 5′-Arylchalcogeno-3-aminothymidine Derivatives

The compounds were prepared by LabSelen NanoBio Laboratory in the Chemistry Department at Federal University of Santa Maria—RS, as described by Da Rosa [52]. Briefly, AZT was initially mesylated employing mesyl chloride and Et3N, producing the respective AZT-mesylate 1 (Scheme 1). Then, the chalcogenium portion was introduced via chalcogenolate anion, obtained by reaction of diaryldichalcogenide 2 and NaBH4. The azide reduction was performed in the same reduction system (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of 5′-arylchalcogeno-3-aminothymidine derivatives.

A total of 12 compounds among selenides (R3a–R3e), tellurides (R3f, R3n–R3q), sulfide (R3r), and AZT were obtained (Figure 1) with yield in the range of 40–78% (see Supplementary Materials). The respective compounds were characterized using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) techniques (1H and 13C) and high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) analysis. Additional information on experimental procedures, NMR data, and HRMS analysis are in da Rosa et al. and Leal et al. [52,53].

2.2. The Effect of Chalcogeno-Zidovudines on Different Cell Lineages Viability

The 5′-arylchalcogeno-3-aminothymidine derivatives (R3 series), previously recognized by the group as important antioxidant and antitumor agents with broad biological spectrum properties [52], were evaluated in this study as potential inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 replication. The antiviral activity of the compounds was evaluated in two distinct cell lines: Calu-3 (that recapitulate human type II pneumocytes) and Vero E6 (African green monkey kidney cells). These cellular models are well-established in studies of SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, the mechanisms of interaction of the Spike protein with the proteases of each of these host cells and the intercellular route of coronavirus are distinct [54,55]. The Calu-3 represents the better infection model, since SARS-CoV-2 enters in host cell mediated by transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2) [56]. This human pneumocyte cell line is widely used as a preclinical model of respiratory cells for drug screening and nasal spray development against respiratory infections, thus was used in this research as the main in vitro infection model [57,58,59].

First, we assayed the toxicity of the organocompounds to ensure the safety before the antiviral assays. Therefore, non-infected cells were treated with high concentrations (6.25–200 µM) of each chalcogen-zidovudine derivative (R3 series) and subsequently processed for the cell viability assay.

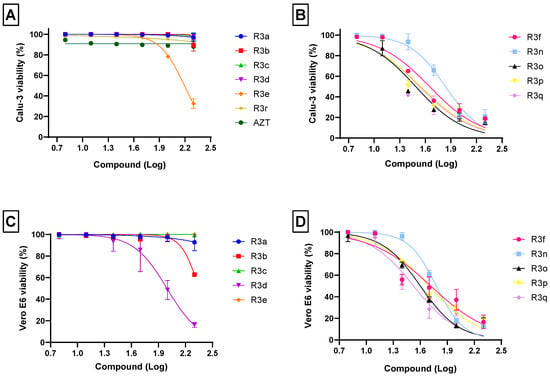

The cell toxicity was determined by methylene blue procedure and the results showed that all chalcogen-zidovudine derivatives containing selenium (R3a–3e) stood out in the cell-based analysis for presenting CC50 values ≥ 100 µM for both Calu-3 and Vero E6 models (Figure 2A,C). Exclusively, the R3a–3c showed CC50 > 200 µM in Calu-3 and Vero E6 cells (Table 1). In contrast, it was evidenced that despite tellurium compounds (R3f; R3n–R3q) being more cell toxic than the selenium (R3a–3e) compounds, the tellurium compounds are not toxic to either cell models at the maximum concentration used (10 µM) in the anti-SARS-CoV-2 assays (Section 2.3). The viability of Vero E6 and Calu-3 was substantially reduced after the treatment with the compounds R3f and R3n–R3q at high concentrations (Figure 2B,D). On average, CC50 values for organoselenium compounds are up to 6-fold greater than those for organotellurium compounds (Table 1). The organosulfur (R3r) and AZT were used as compound controls, and the CC50 values were >200 µM in Calu-3 for both compounds.

Figure 2.

Effects of chalcogen-zidovudine derivatives on the viability of Calu-3 (A,B) and Vero E6 (C,D) cells. The cells were exposed to different concentrations (6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, 100 and 200 µM) of molecules for 72 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2. The cell viability was determined by staining with methylene blue procedure. High cell viability was observed in both cellular models when treated with organoseleniums R3a–R3e (A,C). On the other hand, treatment with organotellurium compounds R3f–R3q revealed higher toxicity in both cellular models (B,D). Organosulfur (R3r) and AZT were used as compounds control (A). Values of R2 varied from 0.80 to 0.97.

Table 1.

Biological activity for the chalcogen-zidovudine compounds according to EC50, CC50, and SI values in Vero E6 (24 hpi) and Calu-3 cells (24 and 48 hpi). The EC50 values were determined under a multiplicity of infection of 0.01.

The understanding that nucleoside and nucleotide analogs are important therapeutic agents and are widely used in the treatment of viral diseases and cancer [60] has directed our research towards molecules belonging to this class and their possible role in the fight against COVID-19. AZT, originally synthesized as an antitumor compound [61], has been approved by the FDA and categorized as an important antiretroviral in the treatment of AIDS [62]. Although AZT plays a valuable role as an inhibitor of the reverse transcriptase of the HIV virus, it also exhibits antibacterial activity in vivo [63] and inhibits the growth of breast, ovarian, and lung tumors [64,65,66]. However, there are clinical reports that AZT causes many side effects and prolonged use can lead to bone marrow toxicity, causing anemia and leukopenia, and even psychosis, myopathy, cardiopathy, and hepatotoxicity [43,67,68]. Therefore, modifications in the structure of AZT aiming to reduce the drug’s toxicity without compromising its biological activity have been proposed [52,69], e.g., data previously generated by the group reported that the addition of chalcogen in the AZT core was able to amplify the antitumor and antioxidant activity of the new compounds, as well as reducing cell damage and toxicity in treatments performed with human leukocytes and in mice inoculated with the organochalcogen [52].

Synthetic compounds containing chalcogen atoms have been the subject of several studies due to their broad biological properties [70,71]. The performance of organoselenium, organotellurium, and organosulfur against free radicals, as well as their effectiveness as antiviral, anti-inflammatory, and antitumor agents, has directed many scientific studies [72,73,74]. Rocha et al. [46], in their research on breast cancer, considered that AZT combined with tellurium not only exhibited selectivity between cancerous and healthy cells, but also had a good pharmacokinetic profile and efficient protective action against oxidative stress. Furthermore, in the study with derivatives of 3′-triazolyl-5′-arylchalcogenilthymidine containing tellurium, it was observed that the higher reactivity and electron-donating capacity presented by this chalcogen justified its better anti-proliferative performance under bladder carcinoma 5637 cells, and, contrary to expectations, tellurium compounds were less toxic in human cell lines and rodents than selenium compounds [75].

The toxicity presented by selenium and tellurium compounds has been debated by some authors, and although studies have shown that organotellurium compounds are less toxic than selenium derivatives [74,75], consistent data indicate that organoselenium compounds have reduced toxicity [50,76,77,78,79]. In the present analyses, it was observed that Vero E6 and Calu-3 were preserved in a selenium organocompounds exposition, and that AZT derivatives containing tellurium were highly toxic for the cells at higher concentrations treatment. In addition to this analysis, it is interesting to note that other selenium compounds also presented low cytotoxicity in other human cell lineages, such as 5′-(4-methylphenylseleno)zidovudine (SZ3), which showed reduced toxic effect on immune human cells [51]. Therefore, these findings suggest that the chalcogen-zidovudine activity may be broad, and that this compound class can be categorized as an interesting candidate for future studies as an antiviral.

2.3. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Activity of Chalcogeno-Zidovudines

The recognition that chalcogen addition to the AZT structure increases its bioactivities [80] and that AZT inhibits the RdRp of SARS-CoV-2 [40,41,42] led us to analyze the possible antiviral effect of 5′-arylchalcogeno-3-aminothymidine derivatives on the SARS-CoV-2 replication in previously infected Vero E6 and Calu-3 cells. The concentration used in cytotoxicity assays was up to 20-fold higher than the concentration used in antiviral assays, which ensures the cell viability in this study.

Here, we evaluated the activity of 12 nucleoside analogs belonging to the class of organoselenium (R3a, R3b, R3c, R3d and R3e), organotellurium (R3f, R3n, R3o, R3p and R3q), organosulfur (R3r), and AZT (Figure 1), focusing on molecules that showed the best performance against SARS-CoV-2 in Calu-3 cells. Therefore, the most promising molecules were those that presented high effectivity with lower EC50 and higher selectivity index (SI; calculated by the ratio of CC50 and EC50 values).

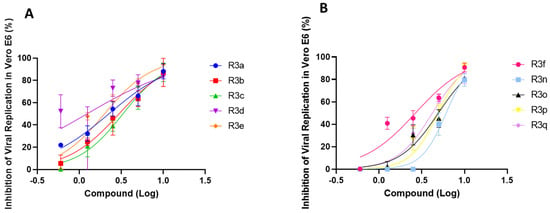

The obtained results demonstrated that at 24 h post-infection (hpi) in Vero E6 cells, compounds R3e, R3f, and R3p inhibited approximately 95% of SARS-CoV-2 replication at the highest tested concentration (10 µM) (Figure 3). However, the most interesting EC50 values were notable for organoselenium molecules (R3a–R3e) and R3f, reaching values below 3.0 µM (Table 1). The pharmacological activity of these compounds against SARS-CoV-2 replication is comparable to that presented by antiretroviral atazanavir in infected Vero E6 cells (EC50: 2.0 ± 0.12 µM) [81].

Figure 3.

Anti-SARS-CoV-2 profile by organocompounds containing selenium (A) and tellurium (B) in Vero E6 cells. Cells were infected with SARS-CoV-2 under MOI of 0.01 for 1 h, then the medium was changed to a medium with R3 molecules in different concentrations (0.6, 1.25, 2.5, 5 and 10 µM). The supernatants were harvested 24 hpi for virus titration by a Plaque-Forming Units (PFU/mL) assay. The effect of treatment was evaluated by comparison with infected/untreated and infected/treated cells. Data represent the results of three independent experiments with three technical replicates. The variation presented by R2 ranged from 0.43 (for organotellurium molecules) to 0.97 (for organoselenium molecules).

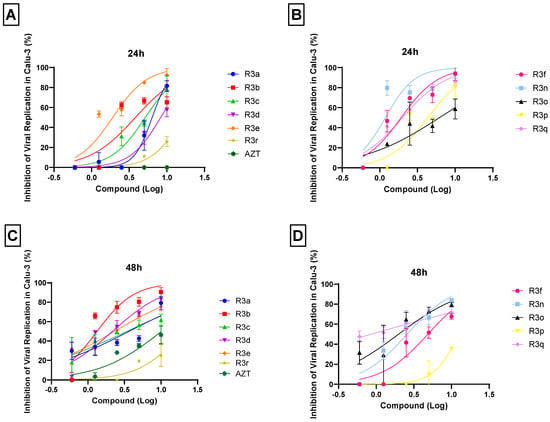

In human type II pneumocytes cells (Calu-3), widely used as a model for human respiratory diseases study and new drugs discovery [58], the treatment effect was evaluated in 24 and 48 hpi. The results obtained after 24 hpi showed that the R3e, R3f, R3n, and R3q at 10 µM inhibited coronavirus replication by over 95% with EC50 ≤ 2 µM (Figure 4A,B and Table 1). On the other hand, when the treatment period was extended to 48 hpi, only the R3b was able to inhibit viral replication by 95% at 10 µM with EC50 value of 1.33 ± 0.35 µM (Figure 4C). This result is comparable those presented for daclatasvir, a SARS-CoV-2 RdRp inhibitor (EC50: 1.1 ± 0.3 µM), on Calu-3-based assays also after 48 hpi [82]. Furthermore, selectivity index (SI) data indicated significant activity of this molecule at a later treatment period, without harming the viability of the host cell. In addition, it was observed that the EC50 for R3d, R3e, R3n, R3o, and R3q was ≤2.57 µM (Table 1). However, the EC50 for R3d and R3o did not represent the concentration of molecules necessary to inhibit 50% of viral replication, because 100% of virus replication inhibition at the maximum evaluated concentration (10 µM) was not observed. Overall, the data highlighted that the selectivity indexes for organoselenium molecules were up to 6-fold higher than for organotellurium compounds (Table 1). Organosulfur (R3r) and AZT were used as compound controls for structural comparison, showing low antiviral effect in the analyzed cell model if compared to the organoselenium compounds tested (Figure 4B,C, Table 1).

Figure 4.

Anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity of chalcogen-zidovudine in Calu-3 cells. Cells were infected with SARS-CoV-2 under MOI of 0.01 for 1 h, then the medium was changed to a medium with R3 molecules in different concentrations (0.6, 1.25, 2.5, 5 and 10 µM). The supernatants were harvested 24 and 48 hpi for virus titration by a Plaque-Forming Units (PFU/mL) assay. The virus titration revealed the inhibitory effect after 24 (A,B) and 48 (C,D) hours of treatment with organoselenium or organosulfur (A,C) and organotellurium (B,D) AZT derivatives. The percentage inhibition was obtained by comparison with infected/untreated and infected/treated cells. Data represent the results of three independent experiments with three technical replicates. The R2 values ranged from 0.63 (for organotellurium molecules) to 0.92 (for organoselenium, organosulfur and AZT molecules).

To validate the experimental assays, atazanavir was used as experimental control for the cell toxicity and the virus inhibition at its CC50 and EC50 values in Vero E6 and Calu-3 assays [81,83].

Interestingly, only organoselenium R3e presented low and similar EC50 values in all cell types tested and regardless of the established treatment time, as verified in Calu-3 cells (Table 1). Moreover, their effect was equivalent to molnupiravir (estimated EC50 of 1.97 µM), an FDA-approved drug for COVID-19 emergency use [84], and more potent than lopinavir/ritonavir (EC50: 8.2 ± 0.3 µM), proposed as a treatment for COVID-19 during 2020 [82]. Furthermore, the selenium derivatives showed prominent SI values, presenting high CC50 values in antiviral in vitro assays. These results contrasted with the cell viability observed in cultures treated with AZT derivatives containing tellurium. In this context, it is important to emphasize that although tellurium compounds have shown interesting EC50 values in both infection models, the curves’ R2 were lower than for organoselenium molecules. Organotellurane’s stability in aqueous solution, such as culture medium, has already been reported [85]. However, we observed a notable results variation. This fact, associated with the high toxicity exhibited by these molecules and their reduced selectivity index (Table 1), directly impacts the non-choice of chalcogen-zidovudines containing tellurium as promising candidates for the next in silico assays.

Repurposing drugs is an important strategy for the development of new effective therapies against SARS-CoV-2 [86]. Remdesivir, an FDA approved drug for COVID-19 treatment, has paved the way for other repurposing drugs [23]. The remdesivir mechanism of action was originally described against positive-strand RNA viruses, including Ebola, HCV, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV [87,88,89], with inhibition of viral RdRp [90,91]. Additional studies have shown that sofosbuvir, alovudine, and zidovudine also act as SARS-CoV-2 polymerase inhibitors [40,92]. In addition, the pharmacological importance of organic selenium compounds against SARS-CoV-2, including the ebselen (Eb) and diphenyl diselenide ((PhSe)2), has been highlighted since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic [33,93,94,95]. The EC50 values obtained for tested organoselenium molecules are comparable to those already reported for Eb and ((PhSe)2 in Calu-3, for both 24 and 48 hpi [94,96]. The obtained data become even more promising due to the solid understanding that selenium derivatives might interact with key enzymes for SARS-CoV-2 replication, i.e., Mpro, PLpro, and RdRp [29,30,31,32,33]. In addition, selenium derivatives also play a key role in the host immune response against RNA viruses, as well as contributing to maintaining redox homeostasis and modulating the inflammatory response, being a feasible multi-target compound [97]. Thus, motivated by the possible interactive profile between selenium derivatives and SARS-CoV-2 Mpro, PLpro, and RdRp, molecular docking calculations were carried out to suggest the main target that the chalcogen-zidovudine derivatives containing selenium compounds (R3a–R3e) might interact with. R3r (chalcogen-zidovudine with sulfur) and AZT were used as comparative molecules. Finally, the possible inhibitory mechanism (competitive, non-competitive, or allosteric) was also explored via in silico calculations.

2.4. In Silico Studies

The favorable in vitro results as anti-SARS-CoV-2 for the chalcogen-zidovudine derivatives containing selenium compounds (R3a–R3e) led to the in silico evaluation on the main targets that these compounds might interact (Mpro, PLpro, and RdRp). Additionally, it was also evaluated the compound R3r to verify the selenium effect on the binding capacity, while AZT (in the active form, AZT triphosphate—AZTTP) was used as a positive control for RdRp. Table 2 summarizes the docking score value (dimensionless) for each enzyme in different inhibitory mechanisms approaches. Since each pose obtained by GOLD 2022.3 software is considered as the negative value of the sum of energy terms, a more positive docking score value indicates better interaction [98].

Table 2.

Molecular docking score value (dimensionless) for the interactive profile between the AZT derivatives and SARS-CoV-2 Mpro, PLpro, and RdRp.

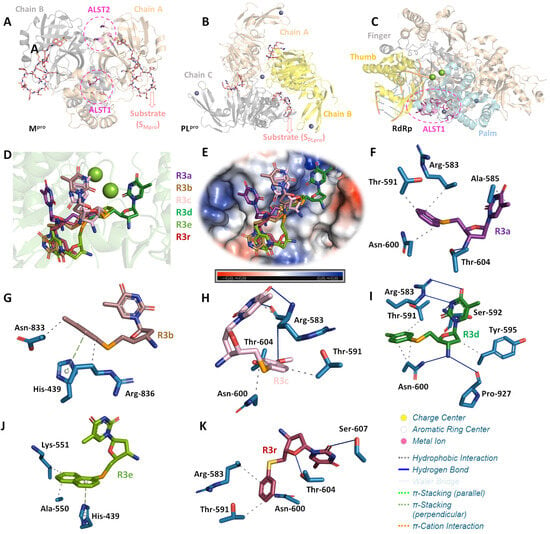

For both SARS-CoV-2 proteases, R3a–R3e and R3r did not show favorable docking score values into the catalytic site in the presence of substrate, suggesting a competitive or allosteric inhibitory approach. The 3D structure of Mpro is composed of a homodimer and its active site is characterized by the presence of amino acid residues His-41 and Cys-145 (Figure 5A), while PLpro is a homotrimer with Cys-112, His-273, and Asp-287 residues as a catalytic triad (Figure 5B). In addition, for Mpro there are two allosteric sites: one in the interface between both monomers formed by Glu-288, Asp-289, Phe-290, and Thr-291 residues (ALST1), and the other on each chain A and B formed by Lys-12, Cys-16, and Lys-97 (ALST2) (Figure 5A) [99,100,101]. The docking score values for both SARS-CoV-2 proteases by competitive inhibitory mechanism approach are quite similar, suggesting that chalcogen-zidovudine derivatives containing selenium compounds can interact with both Mpro and PLpro. These results agree with previous literature on the inhibitory capacity of selenium compounds to SARS-CoV-2 proteases [30,31,102,103].

Figure 5.

The 3D structure of SARS-CoV-2 (A) Mpro, (B) PLpro, and (C) RdRp highlighting the chains constituents for the proteases and the three main regions of polymerase (finger, thumb, and palm). Each allosteric site is represented as pink circle, while Mpro and PLpro substrates (SMpro and SPLpro, respectively) are in stick representation in beige and Mg(II) and Zn(II) are as spheres in green and lilac, respectively. (D) Superposition of the best docking pose for R3a–R3e and R3r into the ALST1 of SARS-CoV-2 RdRp. (E) Electrostatic potential map for SARS-CoV-2 RdRp docked with the chalcogen-zidovudine derivatives containing selenium compounds and R3r. The interactive profile between the amino acid residues from ALST1 of SARS-CoV-2 RdRp with (F) R3a, (G) R3b, (H) R3c, (I) R3d, (J) R3e, and (K) R3r. Selected amino acid residues, R3a, R3b, R3c, R3d, R3e, and R3r are in stick representation in light blue, purple, brown, light pink, dark green, limon, and wine, respectively. Elements’ colors: oxygen, nitrogen, chloro, sulfur, and selenium in red, dark blue, green, yellow, and orange, respectively. For better interpretation, the hydrogen atoms were omitted.

Since the evaluated compounds have AZT moiety, the SARS-CoV-2 RdRp can also be considered as a feasible target to R3a–R3e. Interestingly, the docking score values for RdRp into the catalytic site without and in the presence of substrate are lower than for the allosteric site located in the palm region (ALST1) (Table 2 and Figure 5C). Additionally, the docking score value for the palm region is higher than for SARS-CoV-2 proteases, suggesting that the chalcogen-zidovudine derivatives containing selenium compounds interact preferentially with RdRp than Mpro and PLpro via ALST1. The docking score value for AZT-TP (positive control) is higher than for R3a–R3e into the catalytic site of RdRp in the presence of substrate. It occurs due to the phosphorylation of AZT structure by endogenous enzymes (prodrug), acting as a chain terminator [99,100,104]. Despite R3a–R3e having AZT moiety, it is difficult to ascertain if they act similarly to AZT-TP mainly due to the low probability of chalcogen-zidovudine derivatives containing selenium compounds to be phosphorylated by endogenous enzymes. A future combination of biochemical and biophysical assays, e.g., experimental enzymatic inhibitory assays, thermal shift, and surface plasmon resonance, should be performed to further clarify how R3a–R3e could target SARS-CoV-2 RdRp.

Molecular docking results identified different binding poses and connecting points between each chalcogen-zidovudine derivative containing selenium and RdRp into ALST1 (Figure 5D,E). Hydrophobic and hydrogen bonding were detected as the main intermolecular forces (Figure 5F–K and Table 3); however, the p-methylbenzene and naphthalene moieties from R3b and R3e, respectively, might interact via π-stacking forces with His-439 residue in a positive electrostatic pocket of the enzyme (Figure 5E,G,J). This has been reported as an important region for the SARS-CoV-2 RdRp activity [105]; thus, this might be one of the reasons that the compounds R3b and R3e had better in vitro anti-SARS-CoV-2 results than the others tested compounds.

Table 3.

Molecular docking results for the interaction between SARS-CoV-2 RdRp and R3a–R3e/R3r in the ALST1.

It is important to highlight that despite the replacement of selenium (R3a) by sulfur (R3r) did not impact drastically the docking score value, which was expected mainly due to their structural similarities, the sulfur-bearing R3r also did not display considerable inhibition of viral replication in vitro, probably due to the impact on the binding pose, resulting in differences in the interactive profile with the amino acid residues located in the ALST1 of SARS-CoV-2 RdRp. Additionally, besides the possible influence of the size of chalcogen atoms, the selenium- and tellurium-related redox processes may play a key role in the viral inhibition activity [33,106], reinforcing their differences in the experimental assays. This is supported by extant literature, as selenium- and tellurium-bearing organic compounds may undergo reversible redox reactions in biological medium [79,107], leading to either anti- or prooxidant effects upon enzymes, particularly thiol-dependent ones [108,109]. As selenoethers and telluroethers are among the known biologically active organochalcogen derivatives [110,111], the redox-related hypothesis may deserve proper evaluation in future studies.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Cell Culture and Virus

African green monkey kidney cells (Vero E6, ATCC CRL-1586) and human type II pneumocytes model (Calu-3) were kindly provided by Farmanguinhos platform RPT11M and grown in high-glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM; GIBCO) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 µg/mL streptomycin. The cells were grown in 96-well plates with a density of 1.5 × 104 cells/well in an incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2 atmosphere. Afterwards, the cultures were processed for different assays. The SARS-CoV-2 isolate (lineage B.1, GenBank #MT710714, SisGen AC58AE2) was stored at −80 °C and manipulated in a biosafety level 3 (BSL3) environment, in accordance with World Health Organization recommendations [112].

3.2. Cytotoxicity Assays

Vero E6 and Calu-3 cells grown in 96-well plates were treated with molecules for 72 h at different concentrations, ranging from 6.25–200 µM. The compounds were previously solubilized in 100% dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) and reached a final concentration of 0.1% (v/v) after dilution in DMEM in order to not compromise cell growth [113,114]. As an experimental control, the cell lines were maintained only with the solvent DMSO in the same proportion of treated cells.

The cell viability was determined by staining with methylene blue to quantify the percentage of viable cells post-treatment [115]. For this analysis, the cells were washed with saline solution and fixed/stained for 1 h in the incubator with methylene blue solution (Hanks’ solution (HBSS) + 1.25% glutaraldehyde + 0.6% methylene blue). Then, the solution was removed, and cells were washed with distilled water and dried at room temperature (RT). Subsequently, elution solution (50% ethanol, 49% PBS, 1% acetic acid) was added and the cells were incubated for 15 min at RT. Finally, the supernatant of the stained cultures was transferred to a 96-well plate and read at a wavelength of 660 nm. To evaluate the data obtained, a viability curve was constructed to obtain the CC50 values, which is the molecule concentration that causes the death of 50% of the treated cells [115].

3.3. Viral Replication Inhibition Assays

Vero E6 and Calu-3 cells were infected with SARS-CoV-2 at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.01 for 1 h at 37 °C. The cells were treated with the R3 series molecules using a concentration curve (0.6, 1.25, 2.5, 5 and 10 µM). After 24 and 48 hpi, the supernatants were harvested, and the virus was grown in the presence or absence of molecules titrated. The effect of the treatment was evaluated by comparing the cells that were only infected, which were characterized as the infection control, with infected and treated cells. The EC50 values obtained are the concentration of molecule necessary to obtain 50% of its effective inhibitory activity [96,115]. The CC50 and EC50 values of the atazanavir (ATV) were used as an experimental control for virus inhibition and cell viability in Vero E6 and Calu-3 assays [81,83].

3.4. SARS-CoV-2 Titration

The replication capacity of SARS-CoV-2 in cell cultures with or without treatment was performed by plaque forming units’ assays (PFU/mL). Vero E6 previously seeded in 96-well plates were exposed to different dilutions of the supernatants. After 1 h of infection, 2.4% carboxymethylcellulose medium (containing DMEM 10×, sodium bicarbonate 0.22%, FBS 2%, penicillin 1%, and streptomycin 1%) was added and the infection was maintained for 72 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2 atmosphere. For the control, non-exposed cells to virus supernatants followed the same steps described above. After the infection time, the same volume of formalin 10% was added for cell fixation and viral inactivation. After 3 h, the medium was removed, and the monolayer was stained for 1 h with crystal violet 0.04%. After this step, the dye was removed, the wells were washed in running water, and dried at RT for subsequent quantification of PFUs [96,115].

3.5. Graphics

The graphics were made using GraphPad Prism version 9.0 program for Windows (GraphPad Software, Boston, MA, USA). The CC50 and EC50 values were determined by Nonlinear regression of Log (inhibitor) vs. Normalized response, of best curve generated.

3.6. Molecular Docking Studies

Structure models of compounds R3a–R3f, R3r, and AZT (in the active form, AZT triphosphate—AZTTP) were built in Avogadro molecular editor [15], followed by energy minimization by UFF method, available in the same software [116]. In all examples, amine was in a protonated state to conform with biological medium. Energy-minimized models were further optimized by PM6 semiempirical method [117], included in MOPAC quantum chemistry software, version 2016. The crystallographic structure of Mpro, PLpro, and RdRp was obtained in the Protein Data Bank (PDB), with access code 6LU7, 6W9C, and 7BV2, respectively [118,119]. Molecular docking calculations were performed with GOLD 2022.3.0 software (CCDC, Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, Cambridge, UK) [120] considering competitive, non-competitive, and allosteric inhibitory mechanisms. A radius of 10 Å around the corresponding binding sites was delimitated for molecular docking calculations and the standard scoring function “ChemPLP” was used. The commercial substrate of Mpro (SMpro, modified peptide DABCYLKTSAVLQSGFRKME-EDANS with CAS number 730985-86-1) and PLpro (SPLpro, modified peptide Z-RLRGG-AMC with CAS number 167698-69-3) was docked in the active site of chain A of the corresponding protease, and the best result was replicated for the other chains following previous publication [121]. On the other hand, the substrate of RdRp was reported in the crystallographic structure of this enzyme. Protein-Ligand Interaction Profiler (PLIP) webserver (https://plip-tool.biotec.tu-dresden.de/plip-web/plip/index, accessed on 23 August 2023) [122] was used for the identification of protein-ligand interactions and the 3D-figures were generated by PyMOL Molecular Graphics System 1.0 level software (Delano Scientific LLC software, Schrödinger, New York, NY, USA) [123].

4. Conclusions

Cell-based data have shown that AZT derivatives containing selenium outperformed tellurium compounds in anti-SARS-CoV-2 screening. The selenium molecules R3b and R3e stood out for their potent effect on the SARS-CoV-2 replication in Calu-3 and Vero E6 cells, with low cytotoxicity. Furthermore, the results have expanded the possibilities of in silico studies with the main molecular targets for coronavirus replication (Mpro, PLpro, and RdRp). Although more efforts are needed to understand the molecular mechanisms of R3b and R3e action, the in silico results suggested that these molecules mainly interact in the allosteric site of RdRp located in the palm region. Moreover, the role of selenium as an inflammation modulator also opens ways for further research on the benefits of chalcogen-zidovudine derivatives in the COVID-19 pathogenesis.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/molecules28186696/s1. The experimental procedure and NMR data for the 5′-arylchalcogeno-3-aminothymidine derivatives are available in SM file.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.D.M., J.B.T.d.R. and O.E.D.R.; methodology, A.R.T., R.M.d.R., A.S.R., O.A.C., V.N.S.F., T.K.F.O., D.D.C.S., N.R.R.B., L.D., N.S.R. and J.C.P.M.; software, A.R.T., A.S.R., O.A.C. and J.C.P.M.; validation, A.R.T., O.A.C., L.D., J.C.P.M., O.E.D.R. and M.D.M.; formal analysis, O.A.C., J.C.P.M., O.E.D.R. and M.D.M.; investigation, A.R.T., R.M.d.R., A.S.R., O.A.C., V.N.S.F., T.K.F.O., D.D.C.S., N.R.R.B., N.S.R. and J.C.P.M.; resources, L.D., J.B.T.d.R., O.E.D.R. and M.D.M.; data curation, O.E.D.R. and M.D.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.R.T., R.M.d.R., J.C.P.M., O.E.D.R. and M.D.M.; writing—review and editing, O.A.C., O.E.D.R. and M.D.M.; visualization, M.D.M.; supervision, O.E.D.R. and M.D.M.; project administration, M.D.M.; funding acquisition, J.B.T.d.R., O.E.D.R. and M.D.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) and Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ). A.R.T., A.S.R., V.N.S.F., T.K.F.O., D.D.C.S., N.R.R.B. and M.D.M., supported by Laboratório de Morfologia e Morfogênese Viral, Instituto Oswaldo Cruz (IOC), Fiocruz, FIOTEC (grant number IOC-023-FIO-18-2-58), CNPq (Bolsista do CNPq—Brasil, DT nível 2 grant number: 312027/2022-2), CAPES (scholarships and grant numbers: 88887.717861/2022-00, 88887.694990/2022-00, 88887.719751/2022-00) and FAPERJ (E-26/201.426/2022, E-26/201.574/2021). O.E.D.R. supported by CAPES-Finance Code 001 (PROEX, PrInt-UFSM NANOMATERIAIS), CNPq (306240/2018-1), FAPERGS (Ed. PqG-19/2551-0001932-7). The APC was funded by Oswaldo Cruz Institute.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to Biosafety Level 3 (BSL3) laboratory facility in Pavilhão Leonidas Deane, Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. Fiocruz, RJ; and Andre Sampaio from Farmanguinhos, platform RPT11M, for kindly donating the Calu-3 cells. O.E.D.R. gratefully acknowledge Farmanguinhos (FIOCRUZ).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Sample Availability

Samples of the compounds are available from the authors.

References

- WHO. WHO Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID19—11 March 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- WHO. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Singh, M.; de Wit, E. Antiviral agents for the treatment of COVID-19: Progress and challenges. Cell Rep. Med. 2022, 3, 100549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmah, L.; Abarikwu, S.O.; Arero, A.G.; Essouma, M.; Jibril, A.T.; Fal, A.; Flisiak, R.; Makuku, R.; Marquez, L.; Mohamed, K.; et al. Oral antiviral treatments for COVID-19: Opportunities and challenges. Pharmacol. Rep. 2022, 74, 1255–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, W.; Yi, G.Y.; Zhu, Y. Estimation of the basic reproduction number, average incubation time, asymptomatic infection rate, and case fatality rate for COVID-19: Meta-analysis and sensitivity analysis. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 2543–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klok, F.A.; Kruip, M.; van der Meer, N.J.M.; Arbous, M.S.; Gommers, D.; Kant, K.M.; Kaptein, F.H.J.; van Paassen, J.; Stals, M.A.M.; Huisman, M.V.; et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb. Res. 2020, 191, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, G.; Xu, J.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020, 395, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bearse, M.; Hung, Y.P.; Krauson, A.J.; Bonanno, L.; Boyraz, B.; Harris, C.K.; Helland, T.L.; Hilburn, C.F.; Hutchison, B.; Jobbagy, S.; et al. Factors associated with myocardial SARS-CoV-2 infection, myocarditis, and cardiac inflammation in patients with COVID-19. Mod. Pathol. 2021, 34, 1345–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otifi, H.M.; Adiga, B.K. Endothelial Dysfunction in Covid-19 Infection. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 363, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, L.F. Immune Response, Inflammation, and the Clinical Spectrum of COVID-19. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, J.M.; Monogue, M.L.; Jodlowski, T.Z.; Cutrell, J.B. Pharmacologic Treatments for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Review. JAMA 2020, 323, 1824–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vegivinti, C.T.R.; Evanson, K.W.; Lyons, H.; Akosman, I.; Barrett, A.; Hardy, N.; Kane, B.; Keesari, P.R.; Pulakurthi, Y.S.; Sheffels, E.; et al. Efficacy of antiviral therapies for COVID-19: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. BMC Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roizman, B.S.A. Fields Virology, 7th ed.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ravi, V.; Saxena, S.; Panda, P.S. Basic virology of SARS-CoV 2. Indian J. Med. Microbiol. 2022, 40, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanwell, M.D.; Curtis, D.E.; Lonie, D.C.; Vandermeersch, T.; Zurek, E.; Hutchison, G.R. Avogadro: An advanced semantic chemical editor, visualization, and analysis platform. J. Cheminform. 2012, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.Y.; Zhao, R.; Gao, L.J.; Gao, X.F.; Wang, D.P.; Cao, J.M. SARS-CoV-2: Structure, Biology, and Structure-Based Therapeutics Development. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 587269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Rao, Z. Structural biology of SARS-CoV-2 and implications for therapeutic development. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 685–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steuten, K.; Kim, H.; Widen, J.C.; Babin, B.M.; Onguka, O.; Lovell, S.; Bolgi, O.; Cerikan, B.; Neufeldt, C.J.; Cortese, M.; et al. Challenges for Targeting SARS-CoV-2 Proteases as a Therapeutic Strategy for COVID-19. ACS Infect. Dis. 2021, 7, 1457–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, Z.; Cano, K.E.; Jia, L.; Drag, M.; Huang, T.T.; Olsen, S.K. Targeting SARS-CoV-2 Proteases for COVID-19 Antiviral Development. Front. Chem. 2022, 9, 819165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicenti, I.; Zazzi, M.; Saladini, F. SARS-CoV-2 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase as a therapeutic target for COVID-19. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2021, 31, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouffouk, C.; Mouffouk, S.; Hambaba, L.; Haba, H. Flavonols as potential antiviral drugs targeting SARS-CoV-2 proteases (3CL(pro) and PL(pro)), spike protein, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) and angiotensin-converting enzyme II receptor (ACE2). Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 891, 173759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaves, O.A.; Fintelman-Rodrigues, N.; Wang, X.; Sacramento, C.Q.; Temerozo, J.R.; Ferreira, A.C.; Mattos, M.; Pereira-Dutra, F.; Bozza, P.T.; Castro-Faria-Neto, H.C.; et al. Commercially Available Flavonols Are Better SARS-CoV-2 Inhibitors than Isoflavone and Flavones. Viruses 2022, 14, 1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FDA. Coronavirus (COVID-19)|Drugs. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/emergency-preparedness-drugs/coronavirus-covid-19-drugs (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- National Institutes of Health. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Treatment Guides. Available online: https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/ (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Ganipisetti, V.M.; Bollimunta, P.; Maringanti, S. Paxlovid-Induced Symptomatic Bradycardia and Syncope. Cureus 2023, 15, e33831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Berger, N.A.; Davis, P.B.; Kaelber, D.C.; Volkow, N.D.; Xu, R. COVID-19 rebound after Paxlovid and Molnupiravir during January–June 2022. medRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangiavacchi, F.; Botwina, P.; Menichetti, E.; Bagnoli, L.; Rosati, O.; Marini, F.; Fonseca, S.F.; Abenante, L.; Alves, D.; Dabrowska, A.; et al. Seleno-Functionalization of Quercetin Improves the Non-Covalent Inhibition of M(pro) and Its Antiviral Activity in Cells against SARS-CoV-2. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weglarz-Tomczak, E.; Tomczak, J.M.; Talma, M.; Burda-Grabowska, M.; Giurg, M.; Brul, S. Identification of ebselen and its analogues as potent covalent inhibitors of papain-like protease from SARS-CoV-2. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 3640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sies, H.; Parnham, M.J. Potential therapeutic use of ebselen for COVID-19 and other respiratory viral infections. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 156, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zmudzinski, M.; Rut, W.; Olech, K.; Granda, J.; Giurg, M.; Burda-Grabowska, M.; Kaleta, R.; Zgarbova, M.; Kasprzyk, R.; Zhang, L.; et al. Ebselen derivatives inhibit SARS-CoV-2 replication by inhibition of its essential proteins: PL(pro) and M(pro) proteases, and nsp14 guanine N7-methyltransferase. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 9161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahoo, P.; Lenka, D.R.; Batabyal, M.; Pain, P.K.; Kumar, S.; Manna, D.; Kumar, A. Detailed Insights into the Inhibitory Mechanism of New Ebselen Derivatives against Main Protease (M(pro)) of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2). ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2023, 6, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannalire, R.; Cerchia, C.; Beccari, A.R.; Di Leva, F.S.; Summa, V. Targeting SARS-CoV-2 Proteases and Polymerase for COVID-19 Treatment: State of the Art and Future Opportunities. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 2716–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omage, F.B.; Madabeni, A.; Tucci, A.R.; Nogara, P.A.; Bortoli, M.; Rosa, A.D.S.; Neuza Dos Santos Ferreira, V.; Teixeira Rocha, J.B.; Miranda, M.D.; Orian, L. Diphenyl Diselenide and SARS-CoV-2: In silico Exploration of the Mechanisms of Inhibition of Main Protease (M(pro)) and Papain-like Protease (PL(pro)). J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2023, 63, 2226–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, E.; Li, G. Approved Antiviral Drugs over the Past 50 Years. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2016, 29, 695–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaoui, S.; Dufies, M.; Driowya, M.; Demange, L.; Bougrin, K.; Robert, G.; Auberger, P.; Pages, G.; Benhida, R. Synthesis and anti-cancer activities of new sulfonamides 4-substituted-triazolyl nucleosides. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 27, 1989–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jonghe, S.; Herdewijn, P. An Overview of Marketed Nucleoside and Nucleotide Analogs. Curr. Protoc. 2022, 2, e376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivakrishna, B.; Islam, S.; Panda, A.; Saranya, M.; Santra, M.K.; Pal, S. Synthesis and Anticancer Properties of Novel Truncated Carbocyclic Nucleoside Analogues. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2018, 18, 1425–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperling, R. Zidovudine. Infect. Dis. Obstet. Gynecol. 1998, 6, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohsin, N.U.A.; Ahmed, M.; Irfan, M. Zidovudine: Structural Modifications and their impact on biological activities and pharmacokinetic properties. J. Chil. Chem. Soc. 2019, 64, 4523–4530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, J.; Li, X.; Kumar, S.; Jockusch, S.; Chien, M.; Tao, C.; Morozova, I.; Kalachikov, S.; Kirchdoerfer, R.N.; Russo, J.J. Nucleotide analogues as inhibitors of SARS-CoV Polymerase. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2020, 8, e00674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chien, M.; Anderson, T.K.; Jockusch, S.; Tao, C.; Li, X.; Kumar, S.; Russo, J.J.; Kirchdoerfer, R.N.; Ju, J. Nucleotide Analogues as Inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 Polymerase, a Key Drug Target for COVID-19. J. Proteome Res. 2020, 19, 4690–4697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copertino, D.C., Jr.; Casado Lima, B.C.; Duarte, R.R.R.; Powell, T.R.; Ormsby, C.E.; Wilkin, T.; Gulick, R.M.; de Mulder Rougvie, M.; Nixon, D.F. Antiretroviral drug activity and potential for pre-exposure prophylaxis against COVID-19 and HIV infection. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2022, 40, 7367–7380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richman, D.D.; Fischl, M.A.; Grieco, M.H.; Gottlieb, M.S.; Volberding, P.A.; Laskin, O.L.; Leedom, J.M.; Groopman, J.E.; Mildvan, D.; Hirsch, M.S.; et al. The toxicity of azidothymidine (AZT) in the treatment of patients with AIDS and AIDS-related complex. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. N. Engl. J. Med. 1987, 317, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shastina, N.S.; Mal’tseva, T.; D’Iakova, L.N.; Lobach, O.A.; Chataeva, M.S.; Nosik, D.N.; Shvetz, V.I. Synthesis, properties and anti-HIV activity of novel lipophilic 3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine conjugates containing functional phosphoric linkages. Bioorg. Khim 2013, 39, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Y.J.; Chen, Z.S.; Kwon, C.H. Synthesis and evaluation of sulfonylethyl-containing phosphotriesters of 3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine as anticancer prodrugs. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2014, 22, 5747–5756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira Rocha, A.M.; Severo Sabedra Sousa, F.; Mascarenhas Borba, V.; Munchen, T.S.; Guerin Leal, J.; Dorneles Rodrigues, O.E.; Fronza, M.G.; Savegnago, L.; Collares, T.; Kommling Seixas, F. Evaluation of the effect of synthetic compounds derived from azidothymidine on MDA-MB-231 type breast cancer cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 30, 127365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza, D.; Mariano, D.O.; Nedel, F.; Schultze, E.; Campos, V.F.; Seixas, F.; da Silva, R.S.; Munchen, T.S.; Ilha, V.; Dornelles, L.; et al. New organochalcogen multitarget drug: Synthesis and antioxidant and antitumoral activities of chalcogenozidovudine derivatives. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 3329–3339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quoos, N.; Dornelles, L.; Julieti Buss, K.; Begnini, R.; Collares, T.; Seixas, F.K.; Garcia, F.D.; Rodrigues, O.E.D. Synthesis and Antiproliferative Evaluation of 5-Arylchalcogenyl-3-(phenylselanyl-triazoyl)-thymidine. Chem. Sel. 2020, 5, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomé, G.R.; Oliveira, V.A.; Chitolina Schetinger, M.R.; Saraiva, R.A.; Souza, D.; Dorneles Rodrigues, O.E.; Teixeira Rocha, J.B.; Ineu, R.P.; Pereira, M.E. Selenothymidine protects against biochemical and behavioral alterations induced by ICV-STZ model of dementia in mice. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2018, 294, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecker, A.; Ledur, P.C.; da Silva, R.S.; Leal, D.B.R.; Rodrigues, O.E.D.; Ardisson-Araujo, D.; Waczuk, E.P.; da Rocha, J.B.T.; Barbosa, N.V. Chalcogenozidovudine Derivatives with Antitumor Activity: Comparative Toxicities in Cultured Human Mononuclear Cells. Toxicol. Sci. 2017, 160, 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecker, A.; da Silva, R.S.; Dos Santos, M.M.; Ardisson-Araujo, D.; Rodrigues, O.E.D.; da Rocha, J.B.T.; Barbosa, N.V. Safety profile of AZT derivatives: Organoselenium moieties confer different cytotoxic responses in fresh human erythrocytes during in vitro exposures. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2018, 50, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Rosa, R.M.; Piccoli, B.C.; da Silva, F.D.; Dornelles, L.; Rocha, J.B.T.; Sonego, M.S.; Begnini, K.R.; Collares, T.; Seixas, F.K.; Rodrigues, O.E.D. Synthesis, antioxidant and antitumoral activities of 5′-arylchalcogeno-3-aminothymidine (ACAT) derivatives. Medchemcomm 2017, 8, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, J.G.; Piccoli, B.C.; Oliveira, C.S.; da Silva, F.D.A.; Omage, F.B.; da Rocha, J.B.T.; Sonego, M.S.; Segatto, N.V.; Seixas, F.K.; Collares, T.V.; et al. Synthesis, antioxidant and antitumoral activity of new 5′-arylchalcogenyl-3′-N-(E)-feruloyl-3′, 5′-dideoxy-amino-thymidine (AFAT) derivatives. New J. Chem. 2022, 46, 22306–22313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essalmani, R.; Jain, J.; Susan-Resiga, D.; Andreo, U.; Evagelidis, A.; Derbali, R.M.; Huynh, D.N.; Dallaire, F.; Laporte, M.; Delpal, A.; et al. Distinctive Roles of Furin and TMPRSS2 in SARS-CoV-2 Infectivity. J. Virol. 2022, 96, e00128-22, Erratum in J. Virol. 2022, 96, e0074522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.B.; Farzan, M.; Chen, B.; Choe, H. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 entry into cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, J.M.; Schiffer, J.T.; Bender Ignacio, R.A.; Xu, S.; Kainov, D.; Ianevski, A.; Aittokallio, T.; Frieman, M.; Olinger, G.G.; Polyak, S.J. Drug Combinations as a First Line of Defense against Coronaviruses and Other Emerging Viruses. mBio 2021, 12, e0334721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Sarma, P.; Kaur, H.; Prajapat, M.; Bhattacharyya, A.; Avti, P.; Sehkhar, N.; Bansal, S.; Mahendiratta, S.; Mahalmani, V.M.; et al. Clinically relevant cell culture models and their significance in isolation, pathogenesis, vaccine development, repurposing and screening of new drugs for SARS-CoV-2: A systematic review. Tissue Cell 2021, 70, 101497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Chidekel, A.; Shaffer, T.H. Cultured human airway epithelial cells (calu-3): A model of human respiratory function, structure, and inflammatory responses. Crit. Care Res. Pract. 2010, 2010, 394578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, F.; Castro, P. Concepts and models for drug permeability studies. In Cell-Based In Vitro Models for Nasal Permeability Studies; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordheim, L.P.; Durantel, D.; Zoulim, F.; Dumontet, C. Advances in the development of nucleoside and nucleotide analogues for cancer and viral diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2013, 12, 447–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostertag, W.; Roesler, G.; Krieg, C.J.; Kind, J.; Cole, T.; Crozier, T.; Gaedicke, G.; Steinheider, G.; Kluge, N.; Dube, S. Induction of endogenous virus and of thymidine kinase by bromodeoxyuridine in cell cultures transformed by Friend virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1974, 71, 4980–4985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brook, I. Approval of Zidovudine (AZT) for Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome: A Challenge to the Medical and Pharmaceutical Communities. JAMA 1987, 258, 1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, B.R.; White, G.; Wilson, H.R. In vivo efficacy of zidovudine (3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine) in experimental gram-negative-bacterial infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1989, 33, 479–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, C.R.; Ballato, G.; Akanni, A.O.; McIntee, E.J.; Larson, R.S.; Chang, S.; Abul-Hajj, Y.J. Potent growth inhibitory activity of zidovudine on cultured human breast cancer cells and rat mammary tumors. Cancer Res. 1997, 57, 2341–2345. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Savaraj, N.; Wu, C.; Wangpaichitr, M.; Kuo, M.T.; Lampidis, T.; Robles, C.; Furst, A.J.; Feun, L. Overexpression of mutated MRP4 in cisplatin resistant small cell lung cancer cell line: Collateral sensitivity to azidothymidine. Int. J. Oncol. 2003, 23, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, Y.; Tseng, J.J. Azidothymidine (AZT) Inhibits Proliferation of Human Ovarian Cancer Cells by Regulating Cell Cycle Progression. Anticancer Res. 2020, 40, 5517–5527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abers, M.S.; Shandera, W.X.; Kass, J.S. Neurological and psychiatric adverse effects of antiretroviral drugs. CNS Drugs 2014, 28, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynx, M.D.; McKee, E.E. 3′-Azido-3′-deoxythymidine (AZT) is a competitive inhibitor of thymidine phosphorylation in isolated rat heart and liver mitochondria. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2006, 72, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zenchenko, A.A.; Drenichev, M.S.; Il’icheva, I.A.; Mikhailov, S.N. Antiviral and Antimicrobial Nucleoside Derivatives: Structural Features and Mechanisms of Action. Mol. Biol. 2021, 55, 786–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mugesh, G.; du Mont, W.W.; Sies, H. Chemistry of biologically important synthetic organoselenium compounds. Chem. Rev. 2001, 101, 2125–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michelotti, P.; Goncalves, D.F.; Duarte, T.; Sarturi, J.M.; Da Silva, R.S.; Rodrigues, O.E.D.; Rocha, J.B.T.; Dalla Corte, C.L. Toxicological evaluation of zidovudine and novel chalcogen derivatives in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2023, 37, e23356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, E.; Plano, D.; Lamberto, I.; Font, M.; Encio, I.; Palop, J.A.; Sanmartin, C. Sulfur and selenium derivatives of quinazoline and pyrido [2,3-d]pyrimidine: Synthesis and study of their potential cytotoxic activity in vitro. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 47, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinz, M.; Reis, A.S.; Duarte, V.; da Rocha, M.J.; Goldani, B.S.; Alves, D.; Savegnago, L.; Luchese, C.; Wilhelm, E.A. 4-Phenylselenyl-7-chloroquinoline, a new quinoline derivative containing selenium, has potential antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory actions. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 780, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engman, L. Synthetic applications of organotellurium compounds. Acc. Chem. Res. 1985, 18, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munchen, T.S.; Sonego, M.S.; Souza, D.d.; Dornelles, L.; Seixas, F.K.; Collares, T.; Piccoli, B.C. New 3′-Triazolyl-5′-aryl-chalcogenothymidine: Synthesis and Anti-oxidant and Antiproliferative Bladder Carcinoma (5637) Activity. ChemistrySelect 2018, 3, 3479–3486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, C.W.; Meotti, F.C.; Curte, E.; Pilissao, C.; Zeni, G.; Rocha, J.B. Investigations into the potential neurotoxicity induced by diselenides in mice and rats. Toxicology 2003, 183, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farina, M.; Soares, F.A.; Zeni, G.; Souza, D.O.; Rocha, J.B. Additive pro-oxidative effects of methylmercury and ebselen in liver from suckling rat pups. Toxicol. Lett. 2004, 146, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nogueira, C.W.; Rotta, L.N.; Perry, M.L.; Souza, D.O.; da Rocha, J.B. Diphenyl diselenide and diphenyl ditelluride affect the rat glutamatergic system in vitro and in vivo. Brain Res. 2001, 906, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nogueira, C.W.; Zeni, G.; Rocha, J.B. Organoselenium and organotellurium compounds: Toxicology and pharmacology. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 6255–6285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarturi, J.M.; Dornelles, L.; Segatto, N.V.; Collares, T.; Seixas, F.K.; Piccoli, B.C.; da Silva, F.D.; Omage, F.B.; da Rocha, J.B.T.; Balaguez, R.A.; et al. Chalcogenium-AZT Derivatives: A Plausible Strategy to Tackle The RT-Inhibitors-Related Oxidative Stress While Maintaining Their Anti- HIV Properties. Curr. Med. Chem. 2022, 30, 2449–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fintelman-Rodrigues, N.; Sacramento, C.Q.; Ribeiro Lima, C.; da Silva, F.S.; Ferreira, A.C.; Mattos, M.; de Freitas, C.S.; Cardoso Soares, V.; da Silva Gomes Dias, S.; Temerozo, J.R.; et al. Atazanavir, Alone or in Combination with Ritonavir, Inhibits SARS-CoV-2 Replication and Proinflammatory Cytokine Production. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacramento, C.Q.; Fintelman-Rodrigues, N.; Temerozo, J.R.; Da Silva, A.P.D.; Dias, S.; da Silva, C.D.S.; Ferreira, A.C.; Mattos, M.; Pao, C.R.R.; de Freitas, C.S.; et al. In vitro antiviral activity of the anti-HCV drugs daclatasvir and sofosbuvir against SARS-CoV-2, the aetiological agent of COVID-19. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021, 76, 1874–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, O.A.; Sacramento, C.Q.; Ferreira, A.C.; Mattos, M.; Fintelman-Rodrigues, N.; Temerozo, J.R.; Vazquez, L.; Pinto, D.P.; da Silveira, G.P.E.; da Fonseca, L.B.; et al. Atazanavir Is a Competitive Inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 M(pro), Impairing Variants Replication In Vitro and In Vivo. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 15, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Wang, Y.; Lavrijsen, M.; Lamers, M.M.; de Vries, A.C.; Rottier, R.J.; Bruno, M.J.; Peppelenbosch, M.P.; Haagmans, B.L.; Pan, Q. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant is highly sensitive to molnupiravir, nirmatrelvir, and the combination. Cell Res. 2022, 32, 322–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Princival, C.R.; Archilha, M.; Dos Santos, A.A.; Franco, M.P.; Braga, A.A.C.; Rodrigues-Oliveira, A.F.; Correra, T.C.; Cunha, R.; Comasseto, J.V. Stability Study of Hypervalent Tellurium Compounds in Aqueous Solutions. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 4431–4439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvathaneni, V.; Gupta, V. Utilizing drug repurposing against COVID-19—Efficacy, limitations, and challenges. Life Sci. 2020, 259, 118275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, A.; Saunders, O.L.; Butler, T.; Zhang, L.; Xu, J.; Vela, J.E.; Feng, J.Y.; Ray, A.S.; Kim, C.U. Synthesis and antiviral activity of a series of 1′-substituted 4-aza-7,9-dideazaadenosine C-nucleosides. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 2705–2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheahan, T.P.; Sims, A.C.; Graham, R.L.; Menachery, V.D.; Gralinski, L.E.; Case, J.B.; Leist, S.R.; Pyrc, K.; Feng, J.Y.; Trantcheva, I.; et al. Broad-spectrum antiviral GS-5734 inhibits both epidemic and zoonotic coronaviruses. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, 9, eaal3653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gotte, M. Remdesivir for the treatment of COVID-19: The value of biochemical studies. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2021, 49, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, C.J.; Tchesnokov, E.P.; Woolner, E.; Perry, J.K.; Feng, J.Y.; Porter, D.P.; Gotte, M. Remdesivir is a direct-acting antiviral that inhibits RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 with high potency. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 6785–6797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, Y.L.; Salim, C.K.; Chu, J.J.H. Drug repurposing for COVID-19: Approaches, challenges and promising candidates. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 228, 107930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jockusch, S.; Tao, C.; Li, X.; Anderson, T.K.; Chien, M.; Kumar, S.; Russo, J.J.; Kirchdoerfer, R.N.; Ju, J. A library of nucleotide analogues terminate RNA synthesis catalyzed by polymerases of coronaviruses that cause SARS and COVID-19. Antivir. Res. 2020, 180, 104857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amporndanai, K.; Meng, X.; Shang, W.; Jin, Z.; Rogers, M.; Zhao, Y.; Rao, Z.; Liu, Z.J.; Yang, H.; Zhang, L.; et al. Inhibition mechanism of SARS-CoV-2 main protease by ebselen and its derivatives. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huff, S.; Kummetha, I.R.; Tiwari, S.K.; Huante, M.B.; Clark, A.E.; Wang, S.; Bray, W.; Smith, D.; Carlin, A.F.; Endsley, M.; et al. Discovery and Mechanism of SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 65, 2866–2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citarella, A.; Scala, A.; Piperno, A.; Micale, N. SARS-CoV-2 M(pro): A Potential Target for Peptidomimetics and Small-Molecule Inhibitors. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildner, G.; Tucci, A.R.; Prestes, A.D.S.; Muller, T.; Rosa, A.d.S.; Borba, N.R.R.; Ferreira, V.N.; Rocha, J.B.T.; Miranda, M.D.; Barbosa, N.V. Ebselen and Diphenyl Diselenide Inhibit SARS-CoV-2 Replication at Non-Toxic Concentrations to Human Cell Lines. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermano, G.; Meplan, C.; Mercer, D.K.; Hesketh, J.E. Selenium and viral infection: Are there lessons for COVID-19? Br. J. Nutr. 2020, 125, 618–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaves, O.A.; Loureiro, R.J.S.; Costa-Tuna, A.; Almeida, Z.L.; Pina, J.; Brito, R.M.M.; Serpa, C. Interaction of Two Commercial Azobenzene Food Dyes, Amaranth and New Coccine, with Human Serum Albumin: Biophysical Characterization. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 3, 955–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuce, M.; Cicek, E.; Inan, T.; Dag, A.B.; Kurkcuoglu, O.; Sungur, F.A. Repurposing of FDA-approved drugs against active site and potential allosteric drug-binding sites of COVID-19 main protease. Proteins 2021, 89, 1425–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunther, S.; Reinke, P.Y.A.; Fernandez-Garcia, Y.; Lieske, J.; Lane, T.J.; Ginn, H.M.; Koua, F.H.M.; Ehrt, C.; Ewert, W.; Oberthuer, D.; et al. X-ray screening identifies active site and allosteric inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 main protease. Science 2021, 372, 642–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sztain, T.; Amaro, R.; McCammon, J.A. Elucidation of Cryptic and Allosteric Pockets within the SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021, 61, 3495–3501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogara, P.A.; Omage, F.B.; Bolzan, G.R.; Delgado, C.P.; Aschner, M.; Orian, L.; Teixeira Rocha, J.B. In silico Studies on the Interaction between Mpro and PLpro From SARS-CoV-2 and Ebselen, its Metabolites and Derivatives. Mol. Inform. 2021, 40, e2100028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, M.K.; Fatima, W.; Alraya, R.A.; Khuzaim Alzahrani, A.; Kamal, M.; Alshammari, R.S.; Alshammari, S.A.; Alharbi, L.M.; Alsubaie, N.S.; Alosaimi, R.B.; et al. Selenium and COVID-19: A spotlight on the clinical trials, inventive compositions, and patent literature. J. Infect. Public Health 2022, 15, 1225–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, L.W.; McKenna, C.E. Prodrug approaches to improving the oral absorption of antiviral nucleotide analogues. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2009, 6, 405–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, M.; Mittal, L.; Kumari, A.; Asthana, S. Molecular Dynamics Simulations Reveal the Interaction Fingerprint of Remdesivir Triphosphate Pivotal in Allosteric Regulation of SARS-CoV-2 RdRp. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 639614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, V.; Alberto, E.E.; Tondo, D.W.; Dambrowski, D.; Detty, M.R.; Nome, F.; Braga, A.L. GPx-Like activity of selenides and selenoxides: Experimental evidence for the involvement of hydroxy perhydroxy selenane as the active species. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 138–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, C.W.; Barbosa, N.V.; Rocha, J.B.T. Toxicology and pharmacology of synthetic organoselenium compounds: An update. Arch. Toxicol. 2021, 95, 1179–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comparsi, B.; Meinerz, D.F.; Franco, J.L.; Posser, T.; Prestes Ade, S.; Stefanello, S.T.; dos Santos, D.B.; Wagner, C.; Farina, M.; Aschner, M.; et al. Diphenyl ditelluride targets brain selenoproteins in vivo: Inhibition of cerebral thioredoxin reductase and glutathione peroxidase in mice after acute exposure. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2012, 370, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thenin-Houssier, S.; de Vera, I.M.; Pedro-Rosa, L.; Brady, A.; Richard, A.; Konnick, B.; Opp, S.; Buffone, C.; Fuhrmann, J.; Kota, S.; et al. Ebselen, a Small-Molecule Capsid Inhibitor of HIV-1 Replication. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 2195–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasim, M.J.; Zuraik, M.M.; Abdin, A.Y.; Ney, Y.; Jacob, C. Selenomethionine: A Pink Trojan Redox Horse with Implications in Aging and Various Age-Related Diseases. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNaughton, M.; Engman, L.; Birmingham, A.; Powis, G.; Cotgreave, I.A. Cyclodextrin-derived diorganyl tellurides as glutathione peroxidase mimics and inhibitors of thioredoxin reductase and cancer cell growth. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Laboratory Biosafety Guidance Related to Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19); WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- Dludla, P.V.; Jack, B.; Viraragavan, A.; Pheiffer, C.; Johnson, R.; Louw, J.; Muller, C.J.F. A dose-dependent effect of dimethyl sulfoxide on lipid content, cell viability and oxidative stress in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Toxicol. Rep. 2018, 5, 1014–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, S.T.; Nguyen, H.T.-L.; Truong, K.D. Comparative cytotoxic effects of methanol, ethanol and DMSO on human cancer cell lines. Biomed. Res. Ther. 2020, 7, 3855–3859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caleffi, G.S.; Rosa, A.S.; de Souza, L.G.; Avelar, J.L.S.; Nascimento, S.M.R.; de Almeida, V.M.; Tucci, A.R.; Ferreira, V.N.; da Silva, A.J.M.; Santos-Filho, O.A.; et al. Aurones: A Promising Scaffold to Inhibit SARS-CoV-2 Replication. J. Nat. Prod. 2023, 86, 1536–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rappe, A.K.; Casewit, C.J.; Colwell, K.S.; Goddard, W.A., III; Skiff, W.M. UFF, a full periodic table force field for molecular mechanics and molecular dynamics simulations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 20, 720–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J.J.P. Optimization of parameters for semiempirical methods V: Modification of NDDO approximations and application to 70 elements. J. Mol. Model. 2007, 13, 1173–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Du, X.; Xu, Y.; Deng, Y.; Liu, M.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, B.; Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Peng, C.; et al. Structure of M(pro) from SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of its inhibitors. Nature 2020, 582, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, W.; Mao, C.; Luan, X.; Shen, D.D.; Shen, Q.; Su, H.; Wang, X.; Zhou, F.; Zhao, W.; Gao, M.; et al. Structural basis for inhibition of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from SARS-CoV-2 by remdesivir. Science 2020, 368, 1499–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, G.; Willett, P.; Glen, R.C.; Leach, A.R.; Taylor, R. Development and validation of a genetic algorithm for flexible docking. J. Mol. Biol. 1997, 267, 727–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaves, O.A.; Lima, C.R.; Fintelman-Rodrigues, N.; Sacramento, C.Q.; de Freitas, C.S.; Vazquez, L.; Temerozo, J.R.; Rocha, M.E.N.; Dias, S.S.G.; Carels, N.; et al. Agathisflavone, a natural biflavonoid that inhibits SARS-CoV-2 replication by targeting its proteases. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 222, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adasme, M.F.; Linnemann, K.L.; Bolz, S.N.; Kaiser, F.; Salentin, S.; Haupt, V.J.; Schroeder, M. PLIP 2021: Expanding the scope of the protein-ligand interaction profiler to DNA and RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W530–W534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.C.; Chan, H.C.S.; Hu, Z. Using PyMOL as a platform for computational drug design. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2017, 7, e1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).