Poly(imidazolyliden-yl)borato Complexes of Tungsten: Mapping Steric vs. Electronic Features of Facially Coordinating Ligands

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Pro-Ligand Synthesis

2.2. Ligand Installation

2.3. Quantification of Steric and Electronic Features

2.4. Sub-Series of Ligands

2.4.1. Hydrotris(N-R1-imidazolylidenyl)borates

2.4.2. Cyclopentadienyl Derivatives

2.4.3. Arene Derivatives

2.4.4. Pnictolyl Ligands

2.4.5. Toluidyne Orientation

2.5. A Heterobimetallic Hydrotris(imidazolylidenyl)borate Complex

3. Experimental

3.1. General Considerations

3.2. Synthesis of [W(≡CC6H4Me-4)(CO)2(pic)2(Br)] (2a)

3.3. Synthesis of [Mo(≡CC6H4Me-4)(CO)2(pic)2(Br)] (2b)

3.4. Synthesis of [Tris(1-methylimidazolium)borate] Bis(hexafluorophosphate) ([1](PF6)2)

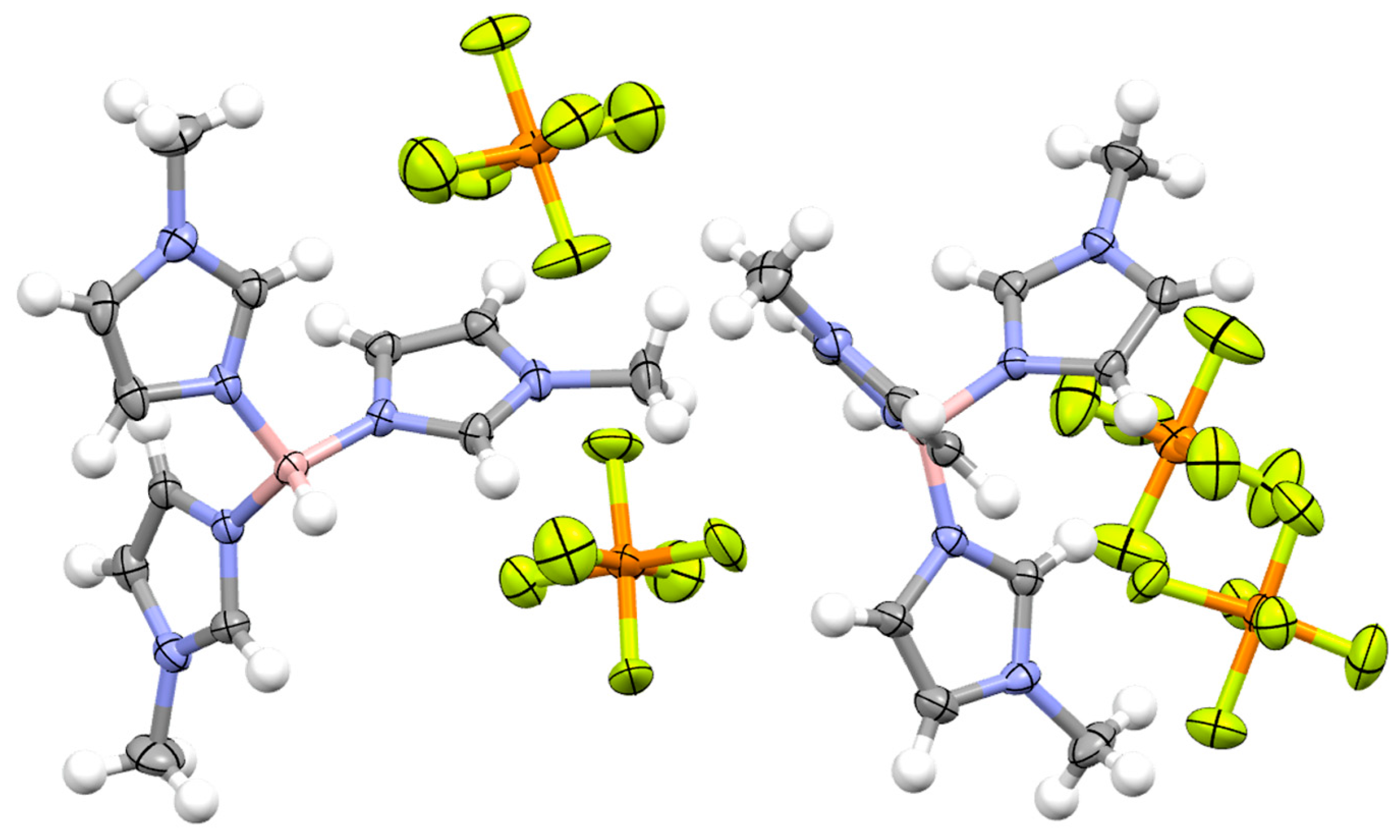

3.5. Synthesis of [W(≡CC6H4Me-4)(CO)2{HB(ImMe)3}] (4)

3.6. Synthesis of [W(≡CC6H4Me-4)(CO)2(Tp*)] (5)

3.7. Synthesis of [WAu(μ2-CC6H4Me-4)Cl(CO)2{HB(ImMe)3}] (6)

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Trofimenko, S. Boron-pyrazole Chemistry. IV. Carbon- and Boron-Substituted Poly[(1-pyrazolyl) borates]. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1967, 89, 6288–6294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trofimenko, S. Scorpionates: The Coordination Chemistry of Polypyrazolylborate Ligands; Imperial College Press: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Pettinari, C. Scorpionates II: Chelating Borate Ligands; Imperial College Press: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkinson, M.; Richter, C.; Schedler, M.; Glorius, F. An Overview of N-Heterocyclic Carbenes. Nature 2014, 510, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellotti, P.; Koy, M.; Glorius, F. Recent Advances in the Chemistry and Applications of N-heterocyclic Carbenes. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2021, 5, 711–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, C.A.; Narouz, M.R.; Lummis, P.A.; Singh, I.; Nazemi, A.; Li, C.-H.; Crudden, C.M. N-Heterocyclic Carbenes in Materials Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 4986–5056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kernbach, U.; Ramm, M.; Luger, P.; Fehlhammer, W.P. A Chelating Triscarbene and its Hexacarbene Iron Complex. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1996, 35, 310–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankel, R.; Kniczek, J.; Ponikwar, W.; Noth, H.; Polborn, K.; Fehlhammer, W.P. Bis(imidazolin-2-ylidene-1-yl)borate Complexes of Palladium(II), Platinum(II) and Gold(I). Inorg. Chim. Acta 2001, 312, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankel, R.; Kernbach, U.; Bakola-Christianopoulou, M.; Plaia, U.; Suter, M.; Ponikwar, W.; Noth, H.; Moinet, C.; Fehlhammer, W.P. Hexacarbene Complexes. J. Organomet. Chem. 2001, 617–618, 530–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biffis, A.; Tubaro, C.; Scattolin, E.; Basato, M.; Papini, G.; Santini, C.; Alvarez, E.; Conejero, S. Trinuclear Copper(I) Complexes with Triscarbene Ligands: Catalysis of C–N and C–C Coupling Reactions. Dalton Trans. 2009, 35, 7223–7229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, I.; Cervantes-Lee, F.; Smith, J.M. A New Synthetic Route to Bulky “Second Generation” Tris(imidazol-2-ylidene)borate Ligands: Synthesis of a Four Coordinate Iron(ii) Complex. Chem. Commun. 2005, 30, 3811–3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Williams, T.J. Di(carbene)-Supported Nickel Systems for CO2 Reduction Under Ambient Conditions. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 6670–6673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meihaus, K.R.; Minasian, S.G.; Lukens, W.W., Jr.; Kozimor, S.A.; Shuh, D.K.; Tyliszczak, T.; Long, J.R. Influence of Pyrazolate vs N-Heterocyclic Carbene Ligands on the Slow Magnetic Relaxation of Homoleptic Trischelate Lanthanide(III) and Uranium(III) Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 6056–6068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickey, A.K.; Muñoz, S.B.; Lutz, S.A.; Pink, M.; Chen, C.-H.; Smith, J.M. Arrested α-hydride migration activates a phosphido ligand for C–H insertion. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 412–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elpitiya, G.R.; Malbrecht, B.J.; Jenkins, D.M. A Chromium(II) Tetracarbene Complex Allows Unprecedented Oxidative Group Transfer. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 14101–14110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bass, H.M.; Cramer, S.A.; McCullough, A.S.; Bernstein, K.J.; Murdock, C.R.; Jenkins, D.M. Employing Dianionic Macrocyclic Tetracarbenes to Synthesize Neutral Divalent Metal Complexes. Organometallics 2013, 32, 2160–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isbill, S.B.; Chandrachud, P.P.; Kern, J.L.; Jenkins, D.M.; Roy, S. Elucidation of the Reaction Mechanism of C2 + N1 Aziridination from Tetracarbene Iron Catalysts. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 6223–6233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrachud, P.P.; Bass, H.M.; Jenkins, D.M. Synthesis of Fully Aliphatic Aziridines with a Macrocyclic Tetracarbene Iron Catalyst. Organometallics 2016, 35, 1652–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anneser, M.R.; Elpitiya, G.R.; Townsend, J.; Johnson, E.J.; Powers, X.B.; DeJesus, J.F.; Vogiatzis, K.D.; Jenkins, D.M. Unprecedented Five-Coordinate Iron(IV) Imides Generate Divergent Spin States Based on the Imide R-Groups. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 8115–8118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anneser, M.R.; Elpitiya, G.R.; Powers, X.B.; Jenkins, D.M. Toward a Porphyrin-Style NHC: A 16-Atom Ringed Dianionic Tetra-NHC Macrocycle and Its Fe(II) and Fe(III) Complexes. Organometallics 2019, 38, 981–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeJesus, J.F.; Jenkins, D.M. A Chiral Macrocyclic Tetra- N -Heterocyclic Carbene Yields an “All Carbene” Iron Alkylidene Complex. Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 26, 1429–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, I.; Bontchev, R.P.; Smith, J.M. Synthesis of a Bulky Bis(carbene)borate Ligand—Contrasting Structures of Homoleptic Nickel(II) Bis(pyrazolyl)borate and Bis(carbene)borate Complexes. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2008, 2008, 2476–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrowsmith, M.; Hill, M.S.; Kociok-Köhn, G. Bis(imidazolin-2-ylidene-1-yl)borate Complexes of the Heavier Alkaline Earths: Synthesis and Studies of Catalytic Hydroamination. Organometallics 2009, 28, 1730–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufhold, S.; Rosemann, N.W.; Chábera, P.; Lindh, L.; Losada, I.B.; Uhlig, J.; Pascher, T.; Strand, D.; Wärnmark, K.; Yartsev, A.; et al. Microsecond Photoluminescence and Photoreactivity of a Metal-Centered Excited State in a Hexacarbene–Co(III) Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 1307–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjær, K.S.; Kaul, N.; Prakash, O.; Chábera, P.; Rosemann, N.W.; Honarfar, A.; Gordivska, O.; Fredin, L.A.; Bergquist, K.E.; Häggström, L.; et al. Luminescence and reactivity of a charge-transfer excited iron complex with nanosecond lifetime. Science 2019, 363, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forshaw, A.P.; Smith, J.M.; Ozarowski, A.; Krzystek, J.; Smirnov, D.; Zvyagin, S.A.; Harris, T.D.; Karunadasa, H.I.; Zadrozny, J.M.; Schnegg, A.; et al. Low-Spin Hexacoordinate Mn(III): Synthesis and Spectroscopic Investigation of Homoleptic Tris(pyrazolyl)borate and Tris(carbene)borate Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 144–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, O.; Chábera, P.; Rosemann, N.W.; Huang, P.; Häggström, L.; Ericsson, T.; Strand, D.; Persson, P.; Bendix, J.; Lomoth, R.; et al. A Stable Homoleptic Organometallic Iron(IV) Complex. Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 26, 12728–12732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forshaw, A.P.; Bontchev, R.P.; Smith, J.M. Oxidation of the Tris(carbene)borate Complex PhB(MeIm)3MnI(CO)3 to MnIV[PhB(MeIm)3]2(OTf)2. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 46, 3792–3794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Wang, G.-F.; Li, Y.-Z.; Chen, X.-T.; Xue, Z.-L. Syntheses, structures and electrochemical properties of homoleptic ruthenium(III) and osmium(III) complexes bearing two tris(carbene)borate ligands. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2012, 21, 88–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Wang, G.-F.; Li, Y.-Z.; Chen, X.-T.; Xue, Z.-L. Synthesis and characterization of rhodium(I) and iridium(I) carbonyl phosphine complexes with bis(N-heterocyclic carbene)borate ligands. J. Organomet. Chem. 2010, 710, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Sun, J.-F.; Li, T.-Y.; Chen, X.-T.; Xue, Z.-L. Iridium(I) and Rhodium(I) Carbonyl Complexes with the Bis(3-tert-butylimidazol-2-ylidene)borate Ligand and Unusual B−H Fluorination. Organometallics 2011, 30, 2006–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiura, T.; Takabatake, A.; Okutsu, M.; Nakazawa, J.; Hikichi, S. Heteroleptic cobalt(iii) acetylacetonato complexes with N-heterocyclic carbine-donating scorpionate ligands: Synthesis, structural characterization and catalysis. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 2564–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fostvedt, J.I.; Lohrey, T.D.; Bergman, R.G.; Arnold, J. Structural diversity in multinuclear tantalum polyhydrides formed via reductive hydrogenolysis of metal–carbon bonds. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 13263–13266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fostvedt, J.I.; Boreen, M.A.; Bergman, R.G.; Arnold, J. A Diverse Array of C–C Bonds Formed at a Tantalum Metal Center. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 9912–9931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieto, I.; Bontchev, R.P.; Ozarowski, A.; Smirnov, D.; Krzystek, J.; Telser, J.; Smith, J.M. Synthesis and spectroscopic investigations of four-coordinate nickel complexes supported by a strongly donating scorpionate ligand. Inorganica Chim. Acta 2009, 362, 4449–4460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papini, G.; Bandoli, G.; Dolmella, A.; Lobbia, G.G.; Pellei, M.; Santini, C. New homoleptic carbene transfer ligands and related coinage metal complexes. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2008, 11, 1103–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, S.B.; Foster, W.K.; Lin, H.-J.; Margarit, C.G.; Dickie, D.A.; Smith, J.M. Tris(carbene)borate Ligands Featuring Imidazole-2-ylidene, Benzimidazol-2-ylidene, and 1,3,4-Triazol-2-ylidene Donors. Evaluation of Donor Properties in Four-Coordinate {NiNO}10 Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 51, 12660–13668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.-F.; Li, X.-W.; Li, Y.-Z.; Chen, X.-T.; Xue, Z.-L. Synthesis and structures of π-allylpalladium(II) complexes containing bis(1,2,4-triazol-5-ylidene-1-yl)borate ligands. An unusual tetrahedral palladium complex. J. Organomet. Chem. 2011, 696, 3800–3806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Stevens, E.D.; Nolan, S.P.; Petersen, J.L. Olefin Metathesis-Active Ruthenium Complexes Bearing a Nucleophilic Carbene Ligand. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 2674–2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholl, M.; Trnka, T.M.; Morgan, J.P.; Grubbs, R.H. Increased Ring Closing Metathesis Activity of Ruthenium-Based Olefin Metathesis Catalysts Coordinated with Imidazolin-2-ylidene Ligands. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999, 40, 2247–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, L.; Fürstner, A.; Weskamp, T.; Kohl, F.J.; Herrmann, W.A. Ruthenium carbene complexes with imidazolin-2-ylidene ligands allow the formation of tetrasubstituted cycloalkenes by RCM. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999, 40, 4787–4790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholl, M.; Ding, S.; Lee, C.W.; Grubbs, R.H. Synthesis and Activity of a New Generation of Ruthenium-Based Olefin Metathesis Catalysts Coordinated with 1,3-Dimesityl-4,5-dihydroimidazol-2-ylidene Ligands. Org. Lett. 1999, 1, 953–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardin, D.J.; Doyle, M.J.; Lappert, M.F. Rhodium(I)-catalysed dismutation of electron-rich olefins: Rhodium(I) carbene complexes as intermediates. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1972, 16, 927–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, M.; Zheng, L.; Qiao, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, J. A Unique Ruthenium Carbyne Complex: A Highly Thermo-endurable Catalyst for Olefin Metathesis. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2012, 354, 2743–2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledoux, N.; Drozdzak, R.; Allaert, B.; Linden, A.; Van Der Voort, P.; Verpoort, F. Exploring new synthetic strategies in the development of a chemically activated Ru-based olefin metathesis catalyst. Dalton Trans. 2007, 44, 5201–5210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buil, M.L.; Cardo, J.J.F.; Esteruelas, M.A.; Oñate, E. Square-Planar Alkylidyne–Osmium and Five-Coordinate Alkylidene–Osmium Complexes: Controlling the Transformation from Hydride-Alkylidyne to Alkylidene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 9720–9728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castarlenas, R.; Esteruelas, M.A.; Lalrempuia, R.; Oliván, M.; Oñate, E. Osmium−Allenylidene Complexes Containing an N-Heterocyclic Carbene Ligand. Organometallics 2008, 27, 795–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buil, M.L.; Cardo, J.J.F.; Esteruelas, M.A.; Oñate, E. Dehydrogenative Addition of Aldehydes to a Mixed NHC-Osmium-Phosphine Hydroxide Complex: Formation of Carboxylate Derivatives. Organometallics 2016, 35, 2171–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castarlenas, R.; Esteruelas, M.A.; Oñate, E. Preparation and Structure of Alkylidene−Osmium and Hydride−Alkylidyne−Osmium Complexes Containing an N-Heterocyclic Carbene Ligand. Organometallics 2007, 26, 2129–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buil, M.L.; Cardo, J.J.F.; Esteruelas, M.A.; Fernández, I.; Oñate, E. Hydroboration and Hydrogenation of an Osmium–Carbon Triple Bond: Osmium Chemistry of a Bis-σ-Borane. Organometallics 2015, 34, 547–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, J.; Irran, E.; Hrobárik, P.; Klare, H.F.T.; Oestreich, M. Si–H Bond Activation with Bullock’s Cationic Tungsten(II) Catalyst: CO as Cooperating Ligand. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 18845–18850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koy, M.; Elser, I.; Meisner, J.; Frey, W.; Wurst, K.; Kästner, J.; Buchmeiser, M.R. High Oxidation State Molybdenum N -Heterocyclic Carbene Alkylidyne Complexes: Synthesis, Mechanistic Studies, and Reactivity. Chem. Eur. J. 2017, 23, 15484–15490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, P.M.; van der Ende, M.; Groos, J.; Frey, W.; Wang, D.; Buchmeiser, M.R. Cationic Tungsten Alkylidyne N-Heterocyclic Carbene Complexes: Synthesis and Reactivity in Alkyne Metathesis. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 2020, 3070–3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elser, I.; Groos, J.; Hauser, P.M.; Koy, M.; van der Ende, M.; Wang, D.; Frey, W.; Wurst, K.; Meisner, J.; Ziegler, F.; et al. Molybdenum and Tungsten Alkylidyne Complexes Containing Mono-, Bi-, and Tridentate N-Heterocyclic Carbenes. Organometallics 2019, 38, 4133–4146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groos, J.; Koy, M.; Musso, J.; Neuwirt, M.; Pham, T.; Hauser, P.M.; Frey, W.; Buchmeiser, M.R. Ligand Variations in Neutral and Cationic Molybdenum Alkylidyne NHC Catalysts. Organometallics 2022, 41, 1167–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groos, J.; Hauser, P.M.; Koy, M.; Frey, W.; Buchmeiser, M.R. Highly Reactive Cationic Molybdenum Alkylidyne N-Heterocyclic Carbene Catalysts for Alkyne Metathesis. Organometallics 2021, 40, 1178–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, P.M.; Musso, J.V.; Frey, W.; Buchmeiser, M.R. Cationic Tungsten Oxo Alkylidene N-Heterocyclic Carbene Complexes via Hydrolysis of Cationic Alkylidyne Progenitors. Organometallics 2021, 40, 927–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, L.M. Alkylidyne Complexes Ligated by Poly(pyrazolyl)borates. Adv. Organomet. Chem. 2008, 56, 1–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, M.A.; Moore, D.A.; Popham, R.E.; Sisler, H.H.; Dolan, S.; Shore, S.G. Trimethylamine-Tribromoborane. Inorg. Synth. 2007, 29, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dossett, S.J.; Hill, A.F.; Jeffery, J.C.; Marken, F.; Sherwood, P.; Stone, F.G.A. Synthesis and Reactions of the Alkylidynemetal Complexes [M(CR)(CO)2(η-C5H5)](R = C6H3Me2-2,6, M = Cr, Mo, or W; R = C6H4Me-2, C6H4OMe-2, or C6H4NMe2-4, M = Mo); Crystal Structure of the Compound [MoFe(µ-CC6H3Me2-2,6)(CO)5(η-C5H5)]. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1988, 9, 2453–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.; Hill, A.F.; Nasir, B.A. Steric and "Indenyl" Effects in the Chemistry of Alkylidyne Complexes of Tungsten and Molybdenum. Organometallics 1995, 14, 2987–2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A.F.; Malget, J.M.; White, A.J.P.; Williams, D.J. Dihydrobis(pyrazolyl)borate Alkylidyne Complexes of Tungsten. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2004, 2004, 818–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadwal, R.S.; Rottschäfer, D.; Andrada, D.M.; Frenking, G.; Schürmann, C.J.; Stammler, H.-G. Normal-to-abnormal rearrangement of an N-heterocyclic carbene with a silylene transition metal complex. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 7791–7799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeffery, J.C.; Gordon, F.; Stone, A.; Williams, G.K. Synthesis of alkylidyne tungsten complexes with hydrotris(pyrazol-1-yl)borate ligands. Polyhedron 1991, 10, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.; Cook, D.J.; Hill, A.F.; Malget, J.M.; White, A.J.P.; Williams, D.J. Reactions of Tungsten Alkylidynes with Thionyl Chloride. Organometallics 2004, 23, 2552–2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadepohl, H.; Arnold, U.; Pritzkow, H.; Calhorda, M.J.; Veiros, L.F. Interplay of ketenyl and nitrile ligands on d6-transition metal centres. Acetonitrile as an end-on (two-electron) and a side-on (four-electron) ligand. J. Organomet. Chem. 1999, 587, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foreman, M.R.S.-J.; Hill, A.F.; White, A.J.P.; Williams, D.J. Hydrotris(methimazolyl)borato Alkylidyne Complexes of Tungsten. Organometallics 2003, 22, 3831–3840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kläui, W.; Hamers, H. Molybdän- und wolfram-dicarbonyl-carbin-komplexe stabilisiert durch dreizähnige sauerstoff-liganden. J. Organomet. Chem. 1988, 345, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayr, A.; Ahn, S. Oxidatively induced insertion of an alkylidyne unit into the tungsten tris(pyrazolyl)borate cage. Inorganica Chim. Acta 2000, 300–302, 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, A.R.; Frogley, B.J.; Hill, A.F. Metal coordination to a dimetallaoctatetrayne. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 13674–13684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzano, R.A.; Hill, A.F. Fluorocarbyne complexes via electrophilic fluorination of carbido ligands. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 3776–3781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolman, C.A. Steric effects of phosphorus ligands in organometallic chemistry and homogeneous catalysis. Chem. Rev. 1977, 77, 313–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusev, D.G. Electronic and Steric Parameters of 76 N-Heterocyclic Carbenes in Ni(CO)3(NHC). Organometallics 2009, 28, 6458–6461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorta, R.; Stevens, E.D.; Hoff, C.D.; Nolan, S.P. Stable, three-coordinate Ni(CO)2(NHC)(NHC= N-heterocyclic carbene) complexes enabling the determination of Ni−NHC bond energies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 10490–10491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorta, R.; Stevens, E.D.; Scott, N.M.; Costabile, C.; Cavallo, L.; Hoff, C.D.; Nolan, S.P. Steric and Electronic Properties of N-Heterocyclic Carbenes (NHC): A Detailed Study on Their Interaction with Ni(CO)4. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 2485–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huynh, H.V. Electronic Properties of N-Heterocyclic Carbenes and Their Experimental Determination. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 9457–9492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abernethy, R.J.; Foreman MR, S.t.-J.; Hill, A.F.; Tshabang, N.; Willis, A.C.; Young, R.D. Similar arguments have been applied to complexes of the form [M(NO)(CO)2(L)] and [M(κ3-C3H5)(CO)2(L)] (M = Mo, W): (b) Poly(methimazolyl)borato Nitrosyl Complexes of Molybdenum and Tungsten. Organometallics 2008, 27, 4455–4463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abernethy, R.J.; Foreman, M.R.S.-J.; Hill, A.F.; Smith, M.K.; Willis, A.C. Relative hemilabilities of H2B(az)2 (az = pyrazolyl, dimethylpyrazolyl, methimazolyl) chelates in the complexes [M(η-C3H5)(CO)2{H2B(az)2}] (M = Mo, W). Dalton Trans. 2020, 49, 781–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, M.; Howard, J.A.K.; James, A.L.; Nunn, C.M.; Stone, F.G.A. Alkylidyne(carbaborane)tungsten-gold and -Rhodium Complexes; Crystal Structures of [AuW(µ-CR)(CO)2(PPh3)(η5-C2B9H9Me2)], [RhW(µ-CR)(CO)2(PPh3)2(η5-C2B9H9Me2)], and [RhW(µ-CR)(CO)2(PPh3)2{η5-C2B9(C7H9)H8Me2}](R = C6H4Me-4). J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1987, 1, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, F.-W.; Chan, M.C.-W.; Cheung, K.-K.; Che, C.-M. Carbyne complexes of the group 6 metals containing 1,4,7-triazacyclononane and its 1,4,7-trimethyl derivative. J. Organomet. Chem. 1998, 552, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, F.-W.; Chan, M.C.-W.; Cheung, K.-K.; Che, C.-M. Synthesis, crystal structures and spectroscopic properties of cationic carbyne complexes of molybdenum and tungsten supported by tripodal nitrogen, phosphorus and sulphur donor ligands. J. Organomet. Chem. 1998, 563, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, E.O.; Lindner, T.L.; Kreissl, F.R. Übergangsmetall-carbin-komplexe: XVI. π-Cyclopentadienyl(dicarbonyl)carbin-komplexe des wolframs. J. Organomet. Chem. 1976, 112, C27–C30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, E.O.; Lindner, T.L.; Huttner, G.; Friedrich, P.; Kreißl, F.R.; Besenhard, J.O. Übergangsmetall-Carbin-Komplexe, XXVII. Dicarbonyl(π-cyclopentadienyl)carbin-Komplexe des Wolframs. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 1977, 110, 3397–3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.; Howard, J.A.K.; James, A.P.; Nunn, C.M.; Stone, F.G.A. Synthesis of Alkylidynetungsten Complexes with (Pyrazol-1-yl)borato Ligands; Crystal Structures of [W(CC6H4Me-4)(CO)2{B(pz)4}], [Rh2W(µ3-CC6H4Me-4)(µ-CO)(CO)2(η-C9H7)2{HB(pz)3}]·CH2Cl2 and [FeRhW(µ3-CC6H4Me-4)(µ-MeC2Me)(CO)4(η-C9H7){HB(pz)3}]. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1986, 1, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.; Howard, J.A.K.; James, A.P.; Jelfs, A.N.d.M.; Nunn, C.M.; Stone, F.G.A. Alkylidyne[pyrazol-1-yl)borato]tungsten complexes:metal–carbon triple bonds as four-electron donors. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1984, 24, 1623–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, E.; Hein, J.; Jeffery, J.C.; Ratermann, A.L.; Stone, F.A. Addition of Methylene Groups to the Unsaturated Complex [FeW(μ-CC6H4Me-4)(CO)5(η-C5Me5)]: μ-Alkenyl Ligand Rearrangements at a Dimetal Centre. J. Organomet. Chem. 1986, 307, C23–C26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byers, P.K.; Stone, F.G.A. Alkylidyne Tungsten and Molybdenum Complexes with Pyrazolylmethane Ligands. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1990, 11, 3499–3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devore, D.D.; Henderson, S.J.; Howard, J.A.; Gordon, F.; Stone, A. Docosahedral carbaboranetungsten-alkylidyne complexes: Synthesis of compounds with heteronuclear metal-metal bonds. J. Organomet. Chem. 1988, 358, C6–C10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crennell, S.J.; DeVore, D.D.; Henderson, S.J.B.; Howard, J.A.K.; Stone, F.G.A. Docosahedral Carbaborane(alkylidyne)tungsten Complexes as Reagents for the Synthesis of Compounds with Heteronuclear Metal–metal Bonds: Crystal Structures of [NEt4][W(CC6H6Me2-2,6)(CO)2(η6-C2B10H10Me2)] and [NEt4][WFe(µ-CC6H3Me2-2,6)(CO)4(η6-C2B10H10Me2)]. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1989, 7, 1363–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, F.A.; Kraihanzel, C.S. Vibrational Spectra and Bonding in Metal Carbonyls. I. Infrared Spectra of Phosphine-substituted Group VI Carbonyls in the CO Stretching Region. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1962, 84, 4432–4438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, D.J. Solvent effects on the infrared active CO stretching frequencies of some metal carbonyl complexes—I. Dimanganese decarbonyl and dirhenium decarbonyl. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Spectrosc. 1983, 39, 463–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poater, A.; Cosenza, B.; Correa, A.; Giudice, S.; Ragone, F.; Scarano, V.; Cavallo, L. SambVca: A Web Application for the Calculation of the Buried Volume of N-Heterocyclic Carbene Ligands. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 2009, 1759–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falivene, L.; Cao, Z.; Petta, A.; Serra, L.; Poater, A.; Oliva, R.; Scarano, V.; Cavallo, L. Towards the online computer-aided design of catalytic pockets. Nat. Chem. 2019, 11, 872–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clavier, H.; Nolan, S.P. Percent buried volume for phosphine and N-heterocyclic carbene ligands: Steric properties in organometallic chemistry. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 841–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, J.-D.; Head-Gordon, M. Systematic optimization of long-range corrected hybrid density functionals. J. Chem. Phys. 2008, 128, 084106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, J.D.; Head-Gordon, M. Long-range Corrected Hybrid Density Functionals with Damped Atom–atom Dispersion Corrections. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2008, 10, 6615–6620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hehre, W.J.; Ditchfield, R.; Pople, J.A. Self—Consistent Molecular Orbital Methods. XII. Further Extensions of Gaussian—Type Basis Sets for Use in Molecular Orbital Studies of Organic Molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 1972, 56, 2257–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, P.J.; Wadt, W.R. Ab initio effective core potentials for molecular calculations. Potentials for the transition metal atoms Sc to Hg. J. Chem. Phys. 1985, 82, 270–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, P.J.; Wadt, W.R. Ab initio effective core potentials for molecular calculations. Potentials for K to Au including the outermost core orbitals. J. Chem. Phys. 1985, 82, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadt, W.R.; Hay, P.J. Ab initio effective core potentials for molecular calculations. Potentials for main group elements Na to Bi. J. Chem. Phys. 1985, 82, 284–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SPARTAN20®, Wavefunction Inc.: Irvine, CA, USA, 2022.

- The National Institute of Standards and Technology Computational Chemistry Comparison and Benchmark Data Base. Recommends a scaling factor on 0.9485 for the B97X-D/6-31G* combination. 2022. Available online: https://cccbdb.nist.gov/vibscalejust.asp (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Merrick, J.P.; Moran, D.; Radom, L. An Evaluation of Harmonic Vibrational Frequency Scale Factors. J. Phys. Chem. A 2007, 111, 11683–11700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.Y.; George, M.W.; Gill, P.M.W. EDF2: A Density Functional for Predicting Molecular Vibrational Frequencies. Aust. J. Chem. 2004, 57, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halls, M.D.; Velkovski, J.; Schlegel, H.B. Harmonic frequency scaling factors for Hartree-Fock, S-VWN, B-LYP, B3-LYP, B3-PW91 and MP2 with the Sadlej pVTZ electric property basis set. Theor. Chem. Accounts 2001, 105, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, R.L.; Johnson, R.D.; Irikura, K.K.; Kacker, R.N. Anharmonic Vibrational Frequency Calculations Are Not Worthwhile for Small Basis Sets. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2013, 9, 951–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barone, V.; Cossi, M. Quantum Calculation of Molecular Energies and Energy Gradients in Solution by a Conductor Solvent Model. J. Phys. Chem. A 1998, 102, 1995–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marenich, A.V.; Cramer, C.J.; Truhlar, D.G. Universal Solvation Model Based on Solute Electron Density and on a Continuum Model of the Solvent Defined by the Bulk Dielectric Constant and Atomic Surface Tensions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 6378–6396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klamt, A.; Schüürmann, G. COSMO: A new approach to dielectric screening in solvents with explicit expressions for the screening energy and its gradient. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1993, 2, 799–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klamt, A. Conductor-like Screening Model for Real Solvents: A New Approach to the Quantitative Calculation of Solvation Phenomena. J. Phys. Chem. 1995, 99, 2224–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolenko, T.M.; Petko, K.I.; Yagupolskii, L.M. N-Trifluoromethylazoles. Chem. Heterocyclic Comp. 2009, 45, 430–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffett, L.S.; Gunter, K.L.; Kreisel, K.A.; Yap, G.P.; Rabinovich, D. Nickel nitrosyl complexes in a sulfur-rich environment: The first poly(mercaptoimidazolyl)borate derivatives. Polyhedron 2007, 26, 4758–4764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.C.; Underwood, C. Pentamethylcyclopentadienylnickelnitrosyl: Synthesis and photoelectron spectrum. J. Organomet. Chem. 1997, 528, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landry, V.K.; Pang, K.; Quan, S.M.; Parkin, G. Tetrahedral nickel nitrosyl complexes with tripodal [N3] and [Se3] donor ancillary ligands: Structural and computational evidence that a linear nitrosyl is a trivalent ligand. Dalton Trans. 2007, 8, 820–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacBeth, C.E.; Thomas, J.C.; Betley, T.A.; Peters, J.C. The Coordination Chemistry of “[BP3]NiX” Platforms: Targeting Low-Valent Nickel Sources as Promising Candidates to L3NiE and L3Ni⋮E Linkages. Inorg. Chem. 2004, 43, 4645–4662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomson, N.C.; Crimmin, M.R.; Petrenko, T.; Roseburgh, L.E.; Sproules, S.; Boyd, W.C.; Bergman, R.G.; DeBeer, S.; Toste, F.D.; Wieghardt, K. A Step Beyond the Feltham-Enemark Notation: Spectroscopic and Correlated Ab Initio Computational Support for an Antiferromagnetically Coupled M(II)(NO) Description of Tp*M(NO)(M = Co, Ni). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 18785–18801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, R.; Chen, M.M.L.; Elian, M.; Rossi, A.R.; Mingos, D.M.P. Pentacoordinate nitrosyls. Inorg. Chem. 1974, 13, 2666–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rerek, M.E.; Ji, L.-N.; Basolo, F. The indenyl ligand effect on the rate of substitution reactions of Rh(η-C9H7)(CO)2and Mn(η-C9H7)(CO)3. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1983, 21, 1208–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart-Davis, A.J.; Mawby, R.J. Reactions of π-indenyl complexes of transition metals. Part I. Kinetics and mechanisms of reactions of tricarbonyl-π-indenylmethylmolybdenum with phosphorus(III) ligands. J. Chem. Soc. A Inorg. Phys. Theor. 1969, 2403–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartik, T.; Weng, W.; Ramsden, J.A.; Szafert, S.; Falloon, S.B.; Arif, A.M.; Gladysz, J.A. New Forms of Coordinated Carbon: Wirelike Cumulenic C3 and C5 sp Carbon Chains that Span Two Different Transition Metals and Mediate Charge Transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 11071–11081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzano, R.A.; Hill, A.F. For a review of tricarbido complexes see Propargylidyne and tricarbido complexes. Adv. Organomet. Chem. 2019, 72, 103–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, G.A.; Carr, N.; Green, M.; Mahon, M.F. Reaction of [W(η2-PhC2Ph)3(NCMe)] with o-diphenylphosphino-styrene and -allylbenzene; evidence for novel carbon–carbon double and triple bond cleavage and alkyne insertion reactions. Chem. Commun. 1996, 21, 2431–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, W.-Y. C60-induced alkyne–alkyne coupling and alkyne scission reactions of a tungsten tris(diphenylacetylene) complex. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 1506–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buss, J.A.; Agapie, T. Four-electron deoxygenative reductive coupling of carbon monoxide at a single metal site. Nature 2016, 529, 72–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buss, J.A.; Agapie, T. Mechanism of Molybdenum-MediatedCarbon Monoxide Deoxygenation and Coupling: Mono- and Dicarbyne Complexes Precede C−O Bond Cleavage and C−C Bond Formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 16466–16477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buss, J.A.; Bailey, G.A.; Oppenheim, J.; VanderVelde, D.G.; Goddard, W.A.; Agapie, T. CO Coupling Chemistry of a Terminal Mo Carbide: Sequential Addition of Proton, Hydride, and CO Releases Ethenone. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 15664–15674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, G.A.; Buss, J.A.; Oyala, P.H.; Agapie, T. Terminal, Open-Shell Mo Carbide and Carbyne Complexes: Spin Delocalization and Ligand Noninnocence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 13091–13102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortin, Y.; Lugan, N.; Mathieu, R. Subtle reactivity patterns of non-heteroatom-substituted manganese alkynyl carbene complexes in the presence of phosphorus probes. Dalton Trans. 2005, 9, 1620–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casey, C.P.; Kraft, S.; Kavana, M. Intramolecular CH Insertion Reactions of (Pentamethylcyclopentadienyl)Rhenium Alkynylcarbene Complexes. Organometallics 2001, 20, 3795–3799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, E.O.; Chen, J. Nucleophilic Cleavage of the Carbon-Fluorine Bond in a Fluorocarbene Complex of Manganese. Z. Naturforsch. 1983, 38, 580–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, E.O.; Chen, J.; Scherzer, K. π-Cyclopentadienyl(dicarbonyl)[aryl(halogen)-carben]-komplexe des Mangans und Rheniums. J. Organomet. Chem. 1983, 253, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orama, O.; Schubert, U.; Kreissl, F.R.; Fischer, E.O. Reaction of a Cationic Carbyne Complex with a Carbonylmetalate. The Phenylketenyl Group as a Bridging Ligand. Z. Naturforsch. 1980, 35, 82–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R.D.; Lawes, D.J.; Hill, A.F.; Ball, G.E. Observation of a Tungsten Alkane σ-Complex Showing Selective Binding of Methyl Groups Using FTIR and NMR Spectroscopies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 8294–8297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, T.J.; Kampf, J.W.; Szymczak, N.K. Reduction of Borazines Mediated by Low-Valent Chromium Species. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 13168–13349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinz, R.; Werner, H. Tricarbonylhexamethylborazolechromium. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1967, 6, 91–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreickmann, T.; Arndt, S.; Schrock, R.R.; Müller, P. Imido Alkylidene Bispyrrolyl Complexes of Tungsten. Organometallics 2007, 26, 5702–5711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathey, F. The Organic Chemistry of Phospholes. Chem. Rev. 1988, 88, 429–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmichael, D.; Mathey, F. New Trends in Phosphametallocene Chemistry. Top. Curr. Chem. 2002, 220, 27–51. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, D.P.; Evans, P. f-Block Phospholyl and Arsolyl Chemistry. Chem. Eur. J. 2021, 27, 6645–6665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abel, E.W.; Clark, N.; Towers, C. η-Tetraphenylphospholyl and η-tetraphenylarsolyl derivatives of manganese, rhenium, and iron. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1979, 1552–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, R.M.; Hill, A.F. Arsolyl-supported intermetallic dative bonding. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 6830–6835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirk, R.M.; Hill, A.F. Free and coordinated biarsolyls. Dalton Trans. 2023, 52, 13235–13243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, R.M.; Hill, A.F. Bridging arsolido complexes. Dalton Trans. 2023, 52, 10190–10196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byers, P.K.; Carr, N.; Stone, F.G.A. Chemistry of polynuclear metal complexes with bridging carbene or carbyne ligands. Part 106. Synthesis and reactions of the alkylidyne complexes [M(≡CR)(CO)2{(C6F5)AuC(pz)3}](M = WorMo, R = alkyloraryl, pz = pyrazol-1-yl); crystal structure of [WPtAU(C6F5)(µ3-CMe)(CO)2(PMe2Ph)2{(C6F5)AuC(pz)3}] and 105 preceding parts in the series. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1990, 12, 3701–3708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, G.; Cochrane, C.; Roper, W.; Wright, L. The interaction of an osmium-carbon triple bond with copper(I), silver(I) and gold(I) to give mixed dimetallocyclopropene species and the structures of Os(AgCl)(CR)Cl(CO)(PPh3)2. J. Organomet. Chem. 1980, 199, C35–C38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, N.; Gimeno, M.C.; Goldberg, J.E.; PIlotti, M.U.; Stone, F.G.A.; Topiloglu, I. Synthesis of Mixed-metal Compounds via the Salts [NEt4][Rh(CO)L(η5-C2B9H9R2)](L = PPh3, R = H; L = CO, R = Me); Crystal Structures of the Complexes [WRhAu(µ-CC6H4Me-4)(CO)3(PPh3)(η-C5H5)(η5-C2B9H11)] and [WRh2Au2(µ3-CC6H4Me-4)(CO)6(η-C5H5)(η5-C2B9H9Me2)2]·0.5CH2Cl2. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1990, 7, 2253–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carriedo, G.A.; Riera, V.; Sánchez, G.; Solans, X. Synthesis of new heteronuclear complexes with bridging carbyne ligands between tungsten and gold. X-Ray crystal structure of [AuW(µ-CC6H4Me-4)(CO)2(bipy)(C6F5)Br]. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1988, 7, 1957–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasser, C.E.; Cronje, S.; Raubenheimer, H.G. Fischer-type tungsten acyl (carbeniate), carbene and carbyne complexes bearing C5-attached thiazolyl substituents: Interaction with gold(i) fragments. New J. Chem. 2010, 34, 458–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Li, Y.; Shao, Y.; Hua, Y.; Zhang, H.; Lin, Y.-M.; Xia, H. Reactions of Cyclic Osmacarbyne with Coinage Metal Complexes. Organometallics 2018, 37, 1788–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borren, E.S.; Hill, A.F.; Shang, R.; Sharma, M.; Willis, A.C. A Golden Ring: Molecular Gold Carbido Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 4942–4945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frogley, B.J.; Hill, A.F.; Onn, C.S.; Watson, L.J. Bi- and Polynuclear Transition-Metal Carbon Tellurides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 15349–15353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frogley, B.J.; Hill, A.F. Synthesis of pyridyl carbyne complexes and their conversion to N-heterocyclic vinylidenes. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 15077–15080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onn, C.S.; Hill, A.F.; Olding, A. Metal coordination of phosphoniocarbynes. Dalton Trans. 2020, 49, 12731–12741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A.F.; Manzano, R.A. A [C1+C2] Route to Propargylidyne Complexes. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 6596–6610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burt, L.K.; Hill, A.F. Heterobimetallic μ2-Halocarbyne Complexes. Dalton Trans. 2022, 51, 12080–12099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.L.H.; Parkin, G. Application of the Covalent Bond Classification Method for the Teaching of Inorganic Chemistry. J. Chem. Educ. 2014, 91, 807–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilford, J.B.; Powell, H.M. The crystal and molecular structure of tricarbonyl-π-cyclopentadienyltungstiotriphenylphosphinegold. J. Chem. Soc. A Inorganic Phys. Theor. 1969, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, P.J.; Krohn, K.M.; Mwenda, E.T.; Young, V.G. (2-(Dimethylammonium)ethyl)cyclopentadienyltricarbonylmetalates: Group VI Metal Zwitterions. Attenuation of the Brønsted Basicity and Nucleophilicity of Formally Anionic Metal Centers. Organometallics 2005, 24, 5116–5126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CrysAlisPro. Oxford Diffraction; Revision 5.2; Agilent Technologies UK Ltd.: Yarnton, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dolomanov, O.V.; Bourhis, L.J.; Gildea, R.J.; Howard, J.A.K.; Puschmann, H. OLEX2: A complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Cryst. 2009, 42, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macrae, C.F.; Bruno, I.J.; Chisholm, J.A.; Edgington, P.R.; McCabe, P.; Pidcock, E.; Rodriguez-Monge, L.; Taylor, R.; van de Streek, J.; Wood, P.A. Mercury CSD 2.0—New features for the visualization and investigation of crystal structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2008, 41, 466–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuveke, R.E.H.; Barwise, L.; van Ingen, Y.; Vashisht, K.; Roberts, N.; Chitnis, S.S.; Dutton, J.L.; Martin, C.D.; Melen, R. An International Study Evaluating Elemental Analysis. ACS Cent. Sci. 2022, 8, 855–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| L | x | ν(CO)/cm−1 | kCK/Ncm–1 d | ν(CO)/cm−1 | kCK/Ncm−1 | ν(WC)/cm−1 | %Volburc | Ref | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental a | Calculated b | λ1(λ2) i | |||||||

| 1 | κ3-HB(ImMe)3 | 0 | 1958, 1873 | 14.80 | 1969, 1907 | 15.15 (14.76) | 1334 | 52.4 | - |

| 2 | κ3-HB(pzMe2)3 g | 0 | 1971, 1889 c | 15.07 | 1980, 1912 | 15.27 (14.86) | 1350 | 50.7 | [64] |

| 3 | η5-C2B9H9Me2 | 1– | 1956, 1874 | 14.82 | 1970, 1900 | 15.10 (14.71) | 1354 | 49.6 | [79] |

| 4 | κ3-CpCo(PO3Me2)3 | 0 | 1961, 1859 | 14.74 | 1980, 1906 | 15.23 (14.83) | 1353 | 44.0 | [68] |

| 5 | κ3-HB(mt)3 | 0 | 1967, 1875 | 14.91 | 1983, 1916 | 15.33 (14.93) | 1352 | 48.7 | [67] |

| 6 | η5-C2B9H11 | 1– | 1965, 1880 | 14.93 | 1974, 1906 | 15.18 (14.77) | 1356 | 44.3 | [79] |

| 7 | κ3-Me3[9]aneN3 e | 1+ | 1975, 1879 f | 15.00 | 2003, 1940 | 15.68 (15.27) | 1347 | 52.5 | [80] |

| 8 | κ3-HC(py)3 e | 1+ | 1988, 1894 b,f | 15.22 | 2007, 1949 | 15.78 (15.37) | 1346 | 46.2 | [81] |

| 9 | κ3-[9]aneS3 e,h | 1+ | 2007, 1925 f | 15.59 | 2029, 1980 | 16.20 (15.78) | 1346 | 46.0 | [81] |

| 10 | η5-C5H5 | 0 | 1982, 1902 | 15.24 | 1997, 1941 | 15.64 (15.23) | 1348 | 35.2 | [82] |

| 11 | κ3-HB(pz)3 k | 0 | 1986, 1903 | 15.28 | 1998, 1934 | 15.49 (15.11) | 1347 | 43.3 | [84] |

| 12 | η5-C5Me5 | 0 | 1981, 1910 c,j | 15.29 | 1989, 1933 | 15.51 (15.12) | 1349 | 42.4 | [86] |

| 13 | κ3-HC(pz)3 | 1+ | 1995, 1912 | 15.42 | 2016, 1959 | 15.93 (15.52) | 1347 | 41.7 | [87] |

| 14 | η6-C2B10H10Me2 | 1– | 1990, 1930 | 15.52 | 1981, 1932 | 15.44 (15.04) | 1352 | 53.5 | [89] |

| 15 | κ3-P(py)3 e | 1+ | 2007, 1925 f | 15.62 | 2008, 1951 | 15.80 (15.39) | 1349 | 47.9 | [81] |

| 16 | κ3-MeC(CH2Ph2)3 e,g | 1+ | 1999, 1934 b,f | 15.62 | 2095, 2037 | 17.01 (15.46) | n.r. | 59.8 | [81] |

| 17 | κ3-HC(pzMe2)3 | 1+ | – | – | 2002, 1941 | 15.68 (15.27) | 1349 | 49.1 | – |

| 18 | κ3-MeC(CH2Pme2)3 | 1+ | – | – | 2021, 1974 | 16.09 (15.67) | 1342 | 51.5 | – |

| 19 | η6-C6H6 | 1+ | – | – | 2051, 2017 | 16.68 (16.25) | 1356 | 39.3 | – |

| 20 | η6-C6Me6 | 1+ | – | – | 2030, 1989 | 16.28 (15.85) | 1351 | 45.9 | – |

| 21 | η6-C6Et6 | 1+ | – | – | 2019, 1975 | 16.08 (15.66) | 1351 | 53.3 | |

| 22 | η5-C9H7 (indenyl) | 0 | – | h | 2002, 1949 | 15.74 (15.32) | 1348 | 37.3 | [61] |

| 23 | η5-C13H9 (fluorenyl) | 0 | – | – | 1999, 1941 | 15.65 (15.24) | 1356 | 40.4 | – |

| 24 | η5-C5Ph5 g | 0 | – | – | 2077, 2015 | 16.88 (15.34) | 1532 | 48.3 | – |

| 25 | η5-C5Cl5 | 0 | – | – | 2012, 1962 | 15.92 (15.51) | 1354 | 40.8 | – |

| 26 | η5-C5H3(SiMe3)2-1,3 | 0 | – | – | 1987, 1931 | 15.48 (15.08) | 1307 | 54.5 | – |

| 27 | η5-C5Me4N | 0 | – | – | 1992, 1937 | 15.56 (15.16) | 1350 | 39.2 | – |

| 28 | η5-C5Me4P | 0 | – | – | 1990, 1937 | 15.55 (15.15) | 1348 | 41.7 | – |

| 29 | η5-C5Me4As | 0 | – | – | 1989, 1936 | 15.53 (15.13) | 1348 | 37.5 | – |

| 30 | η5-C5H5BH | 0 | – | – | 2006, 1953 | 15.80 (15.39) | 1351 | 40.8 | – |

| 31 | κ3-MeB(CH2PPh2)3 g | 0 | – | – | 2072, 2003 | 16.74 (15.22) | 1519 | 59.8 | – |

| 32 | κ3-MeB(CH2Pme2)3 | 0 | – | – | 1988, 1933 | 15.50 (15.10) | 1339 | 51.2 | – |

| 33 | κ3-MeB(CH2Sme)3 | 0 | – | – | 1996, 1935 | 15.58 (15.17) | 1348 | 49.7 | – |

| 34 | κ3-HB(mtSe)3 | 0 | – | – | 1981, 1915 | 15.31 (14.91) | 1357 | 49.7 | – |

| 35 | κ3-HB(ImEt)3 | 0 | – | – | 1968, 1906 | 15.13 (14.74) | 1322 | 54.4 | – |

| 36 | κ3-HB(ImiPr)3 | 0 | – | – | 1970, 1907 | 15.16 (14.76) | 1340 | 53.1 | |

| 37 | κ3-HB(ImtBu)3 | 0 | – | – | 1950, 1881 | 14.80 (14.41) | 1334 | 59.5 | – |

| 38 | κ3-HB(ImPh)3 | 0 | – | – | 1981, 1919 | 15.34 (14.94) | 1329 | 54.3 | – |

| 39 | κ3-HB(ImCF3)3 | 0 | – | – | 1999, 1947 | 15.70 (15.29) | 1337 | 57.1 |

| L | x | λmax/nm | λmax/nm | Z(W) | Z(C) | LBO | r(W≡C)/Å | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dxy→π*W≡C | πW≡C→π*W≡C | (W≡C) | ||||||

| 1 | κ3-HB(ImMe)3 (4) | 0 | 433 | 332 | +0.748 | –0.316 | 2.37 | 1.833 |

| 2 | κ3-HB(pzMe2)3 (5) | 0 | 406 | 316 | +1.013 | –0.268 | 2.40 | 1.811 |

| 3 | η5-C2B9H9Me2 | 1– | 435 | 359 | +0.831 | –0.214 | 2.35 | 1.810 |

| 4 | κ3-CpCo(PO3Me2)3 | 0 | 431 | 374 | +1.177 | –0.299 | 2.40 | 1.802 |

| 5 | κ3-HB(mt)3 | 0 | 444 | 335 | +0.685 | –0.256 | 2.42 | 1.800 |

| 6 | η5-C2B9H11 | 1– | 428 | 358 | +0.845 | –0.230 | 2.36 | 1.810 |

| 7 | κ3-Me3[9]aneN3 b | 1+ | 400 | 377 | +0.858 | –0.188 | 2.39 | 1.812 |

| 8 | κ3-HC(py)3x | 1+ | 403 b | 377 b | +0.909 | –0.213 | 2.40 | 1.813 |

| 9 | κ3-[9]aneS3 | 1+ | 377 | 330 | +0.405 | –0.131 | 2.35 | 1.818 |

| 10 | η5-C5H5 | 0 | 420 | 319 | +0.851 | –0.270 | 2.40 | 1.815 |

| 11 | κ3-HB(pz)3 | 0 | 412 | 313 | +0.979 | –0.253 | 2.42 | 1.810 |

| 12 | η5-C5Me5 | 0 | 430 | 326 | +0.870 | –0.284 | 2.41 | 1.814 |

| 13 | κ3-HC(pz)3 b | 1+ | 405 | 337 | +0.886 | –0.190 | 2.41 | 1.811 |

| 14 | η6-C2B10H10Me2 | 1– | 417 | 372 | +0.732 | –0.171 | 2.34 | 1.811 |

| 15 | κ3-P(py)3 b | 1+ | 384 | 332 | +0.911 | –0.214 | 2.40 | 1.809 |

| 17 | κ3-HC(pzMe2)3 | 1+ | 386 | 319 | +0.920 | –0.208 | 2.40 | 1.810 |

| 18 | κ3-MeC(cH2PMe2)3 | 1+ | 390 | 335 | +0.146 | –0.130 | 2.33 | 1.830 |

| 19 | η6-C6H6 | 1+ | 356 | 381 | +0.697 | –0.105 | 2.32 | 1.820 |

| 20 | η6-C6Me6 | 1+ | 386 | 333 | +0.754 | –0.134 | 2.35 | 1.813 |

| 21 | η6-C6Et6 | 1+ | 379 | 336 | +0.759 | –0.130 | 2.33 | 1.814 |

| 22 | η5-C9H7 (indenyl) | 0 | 415 | 354 | +0.889 | –0.269 | 2.45 | 1.802 |

| 23 | η5-C13H9 (fluorenyl) | 0 | 436 | 357 | +0.909 | –0.237 | 2.45 | 1.798 |

| 25 | η5-C5Cl5 | 0 | 422 | 323 | +0.851 | –0.214 | 2.41 | 1.805 |

| 26 | η5-C5H3(SiMe3)2-1,3 | 0 | 418 | 318 | +0.849 | –0.257 | 2.40 | 1.812 |

| 27 | η5-C4Me4N | 0 | 415 | 326 | +0.939 | –0.273 | 2.40 | 1.811 |

| 28 | η5-C4Me4P | 0 | 391 | 365 | +0.755 | –0.247 | 2.37 | 1.816 |

| 29 | η5-C4Me4As | 0 | 390 | 366 | +0.740 | –0.255 | 2.37 | 1.816 |

| 30 | η5-C5H4BH | 0 | 383 | 323 | +0.769 | –0.164 | 2.37 | 1.811 |

| 32 | κ3-MeB(cH2PMe2)3 | 0 | 412 | 329 | +0.274 | –0.213 | 2.37 | 1.825 |

| 33 | κ3-MeB(cH2SMe)3 | 0 | 422 | 323 | +0.587 | –0.224 | 2.40 | 1.809 |

| 34 | κ3-HB(mtSe)3 | 0 | 443 | 338 | +0.631 | –0.263 | 2.42 | 1.800 |

| 35 | κ3-HB(ImEt)3 | 0 | 424 | 329 | +0.763 | –0.324 | 2.35 | 1.835 |

| 36 | κ3-HB(ImiPr)3 | 0 | 437 | 335 | +0.749 | –0.318 | 2.38 | 1.830 |

| 37 | κ3-HB(ImtBu)3 | 0 | 423 | 322 | +0.864 | –0.294 | 2.33 | 1.820 |

| 38 | κ3-HB(ImPh)3 | 0 | 449 | 335 | +0.960 | –0.300 | 2.37 | 1.828 |

| 39 | κ3-HB(ImCF3)3 | 0 | 426 | 329 | +0.689 | –0.238 | 2.37 | 1.824 |

| R | Mean W–C | Mean W–Ccis | W–Ctrans | TR a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Å | Å | Å | ||

| Me | 2.262 | 2.226 | 2.335 | 1.049 |

| CF3 | 2.276 | 2.232 | 2.365 | 1.060 |

| Et | 2.268 | 2.233 | 2.339 | 1.047 |

| iPr | 2.268 | 2.232 | 2.341 | 1.049 |

| Ph | 2.277 | 2.237 | 2.357 | 1.054 |

| tBu | 2.349 | 2.312 | 2.424 | 1.048 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Inglis, C.M.; Manzano, R.A.; Kirk, R.M.; Sharma, M.; Stewart, M.D.; Watson, L.J.; Hill, A.F. Poly(imidazolyliden-yl)borato Complexes of Tungsten: Mapping Steric vs. Electronic Features of Facially Coordinating Ligands. Molecules 2023, 28, 7761. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28237761

Inglis CM, Manzano RA, Kirk RM, Sharma M, Stewart MD, Watson LJ, Hill AF. Poly(imidazolyliden-yl)borato Complexes of Tungsten: Mapping Steric vs. Electronic Features of Facially Coordinating Ligands. Molecules. 2023; 28(23):7761. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28237761

Chicago/Turabian StyleInglis, Callum M., Richard A. Manzano, Ryan M. Kirk, Manab Sharma, Madeleine D. Stewart, Lachlan J. Watson, and Anthony F. Hill. 2023. "Poly(imidazolyliden-yl)borato Complexes of Tungsten: Mapping Steric vs. Electronic Features of Facially Coordinating Ligands" Molecules 28, no. 23: 7761. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28237761

APA StyleInglis, C. M., Manzano, R. A., Kirk, R. M., Sharma, M., Stewart, M. D., Watson, L. J., & Hill, A. F. (2023). Poly(imidazolyliden-yl)borato Complexes of Tungsten: Mapping Steric vs. Electronic Features of Facially Coordinating Ligands. Molecules, 28(23), 7761. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28237761