Non-Isocyanate Urethane Acrylate Derived from Isophorone Diamine: Synthesis, Characterization and Its Application in 3D Printing

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

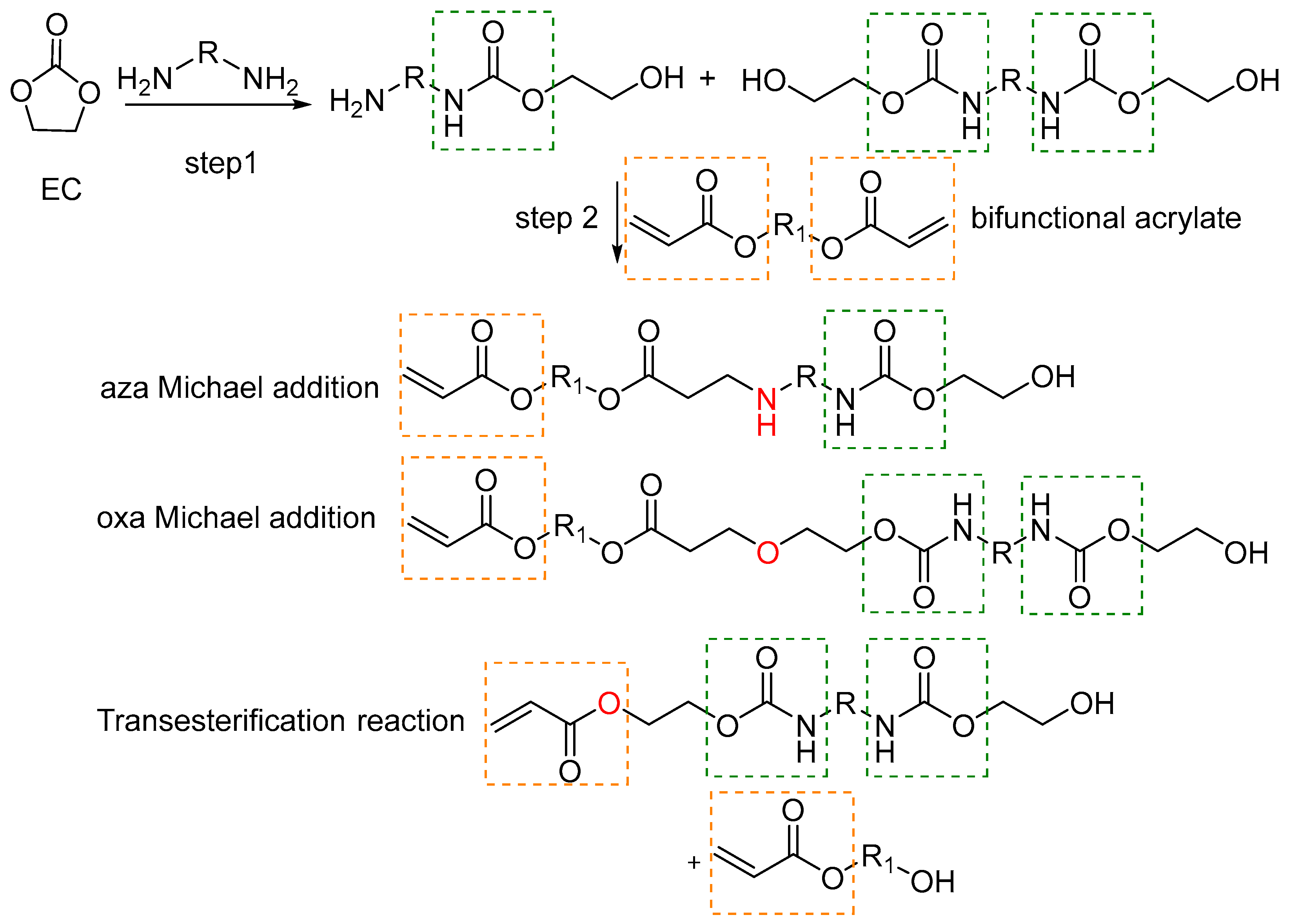

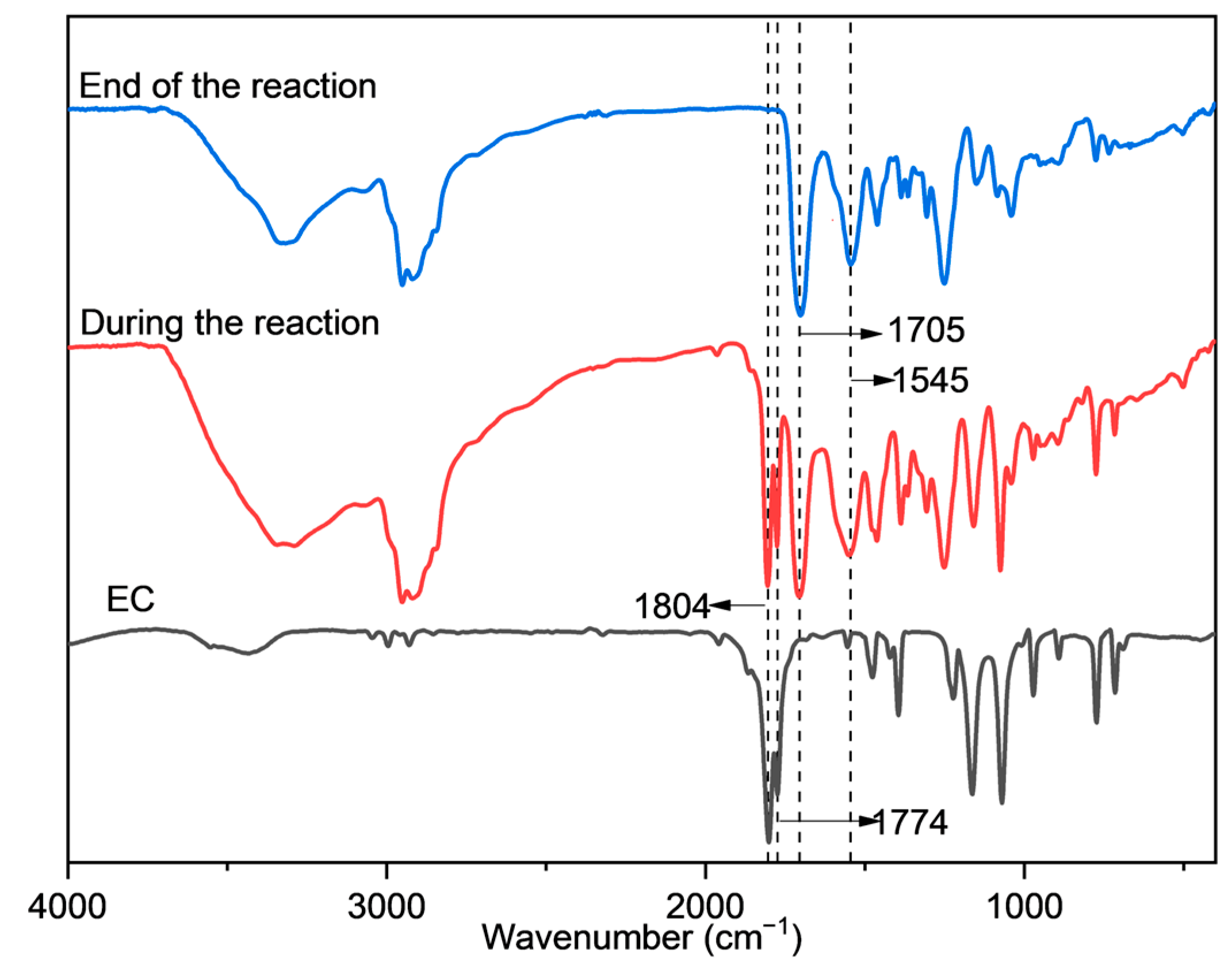

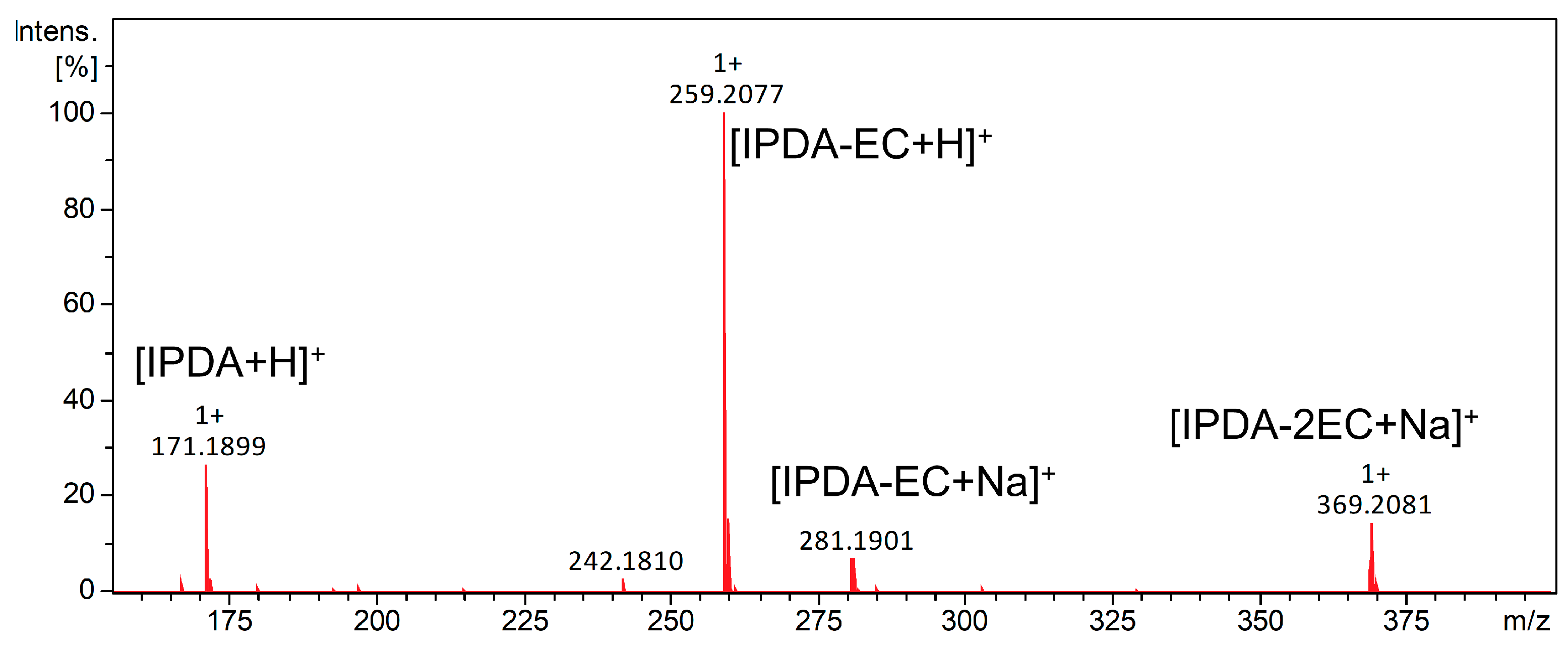

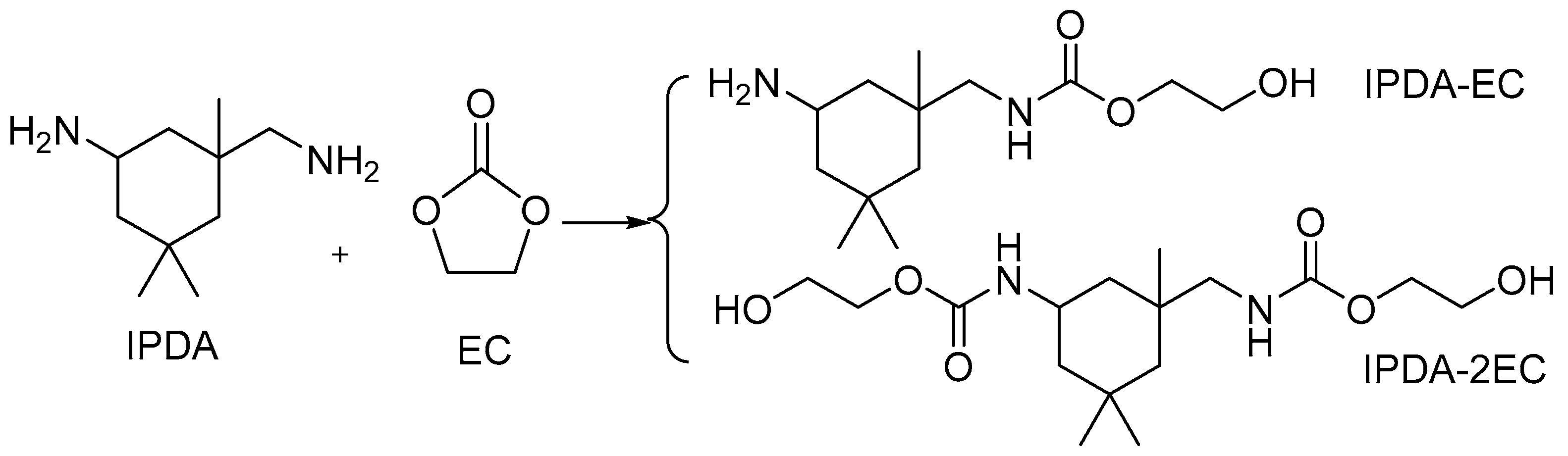

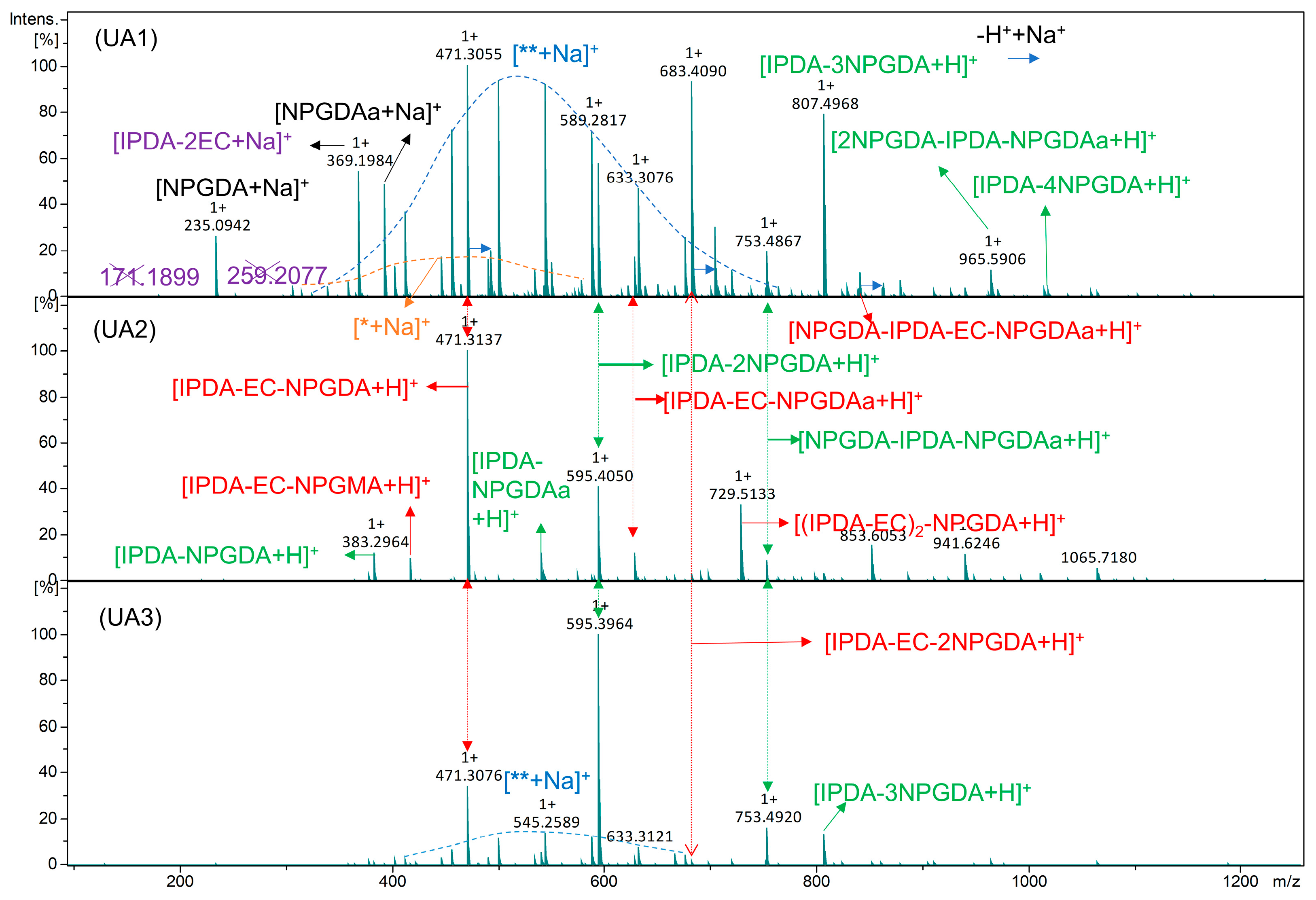

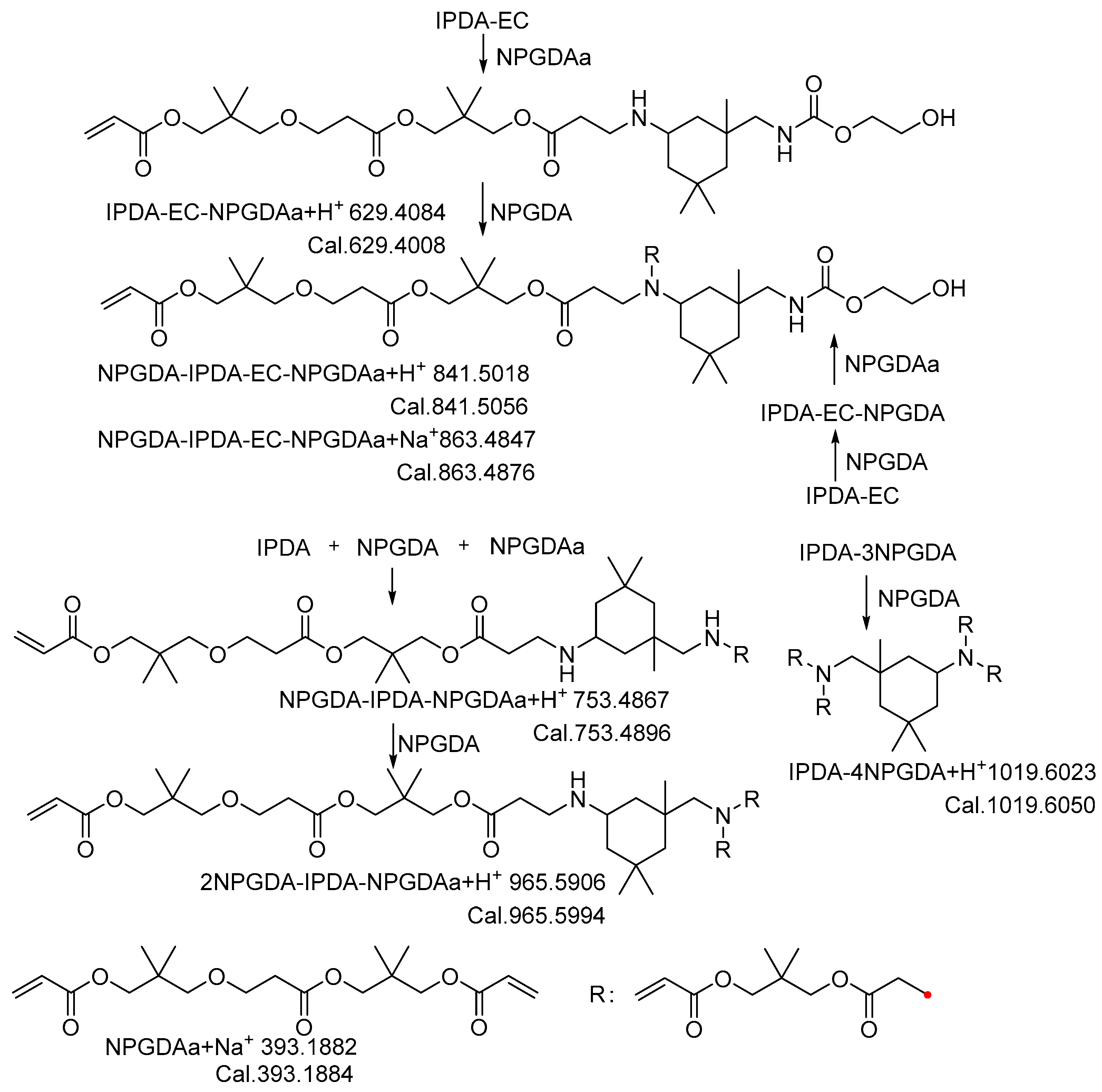

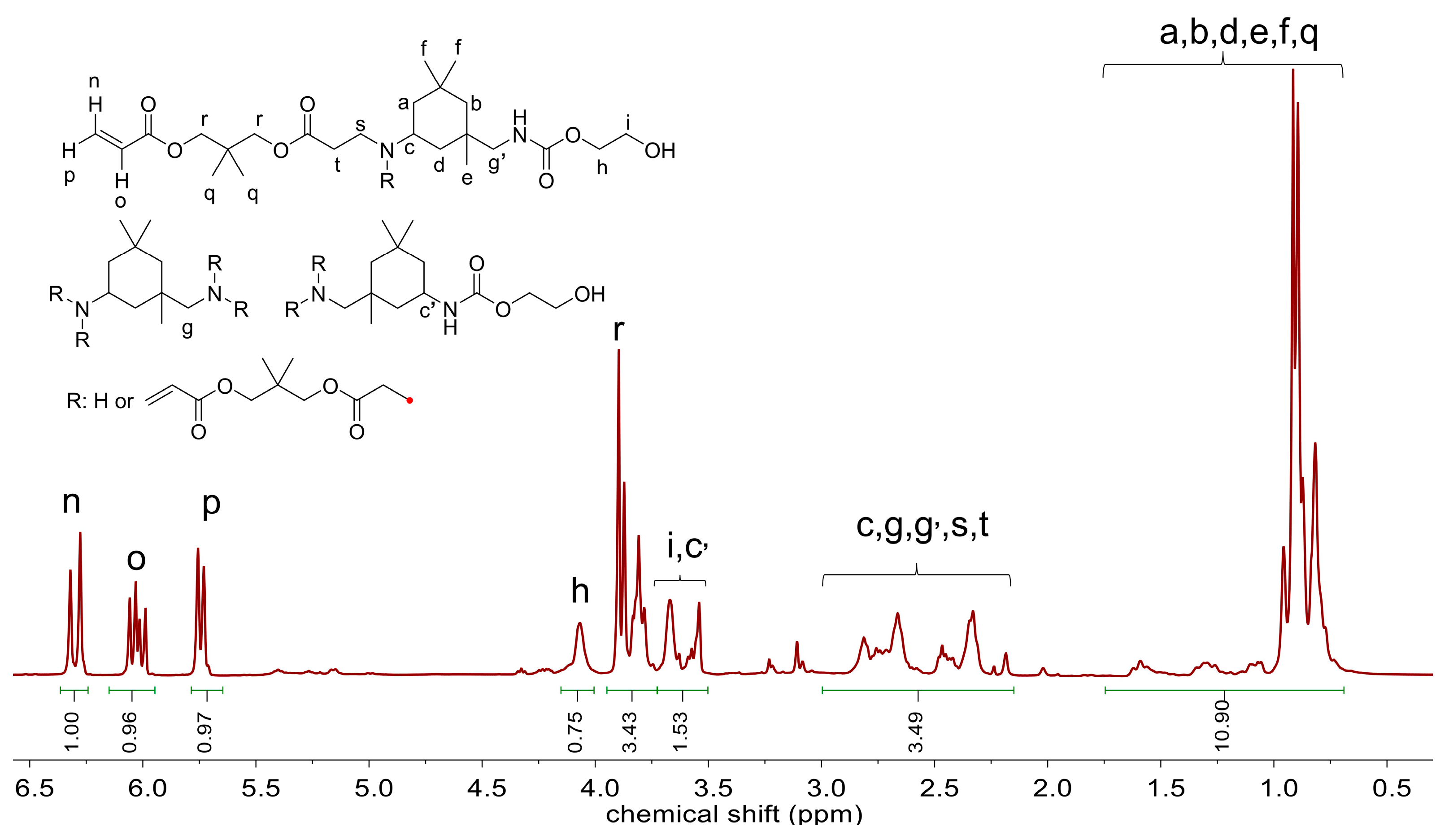

2.1. Synthesis and Characterization of UA

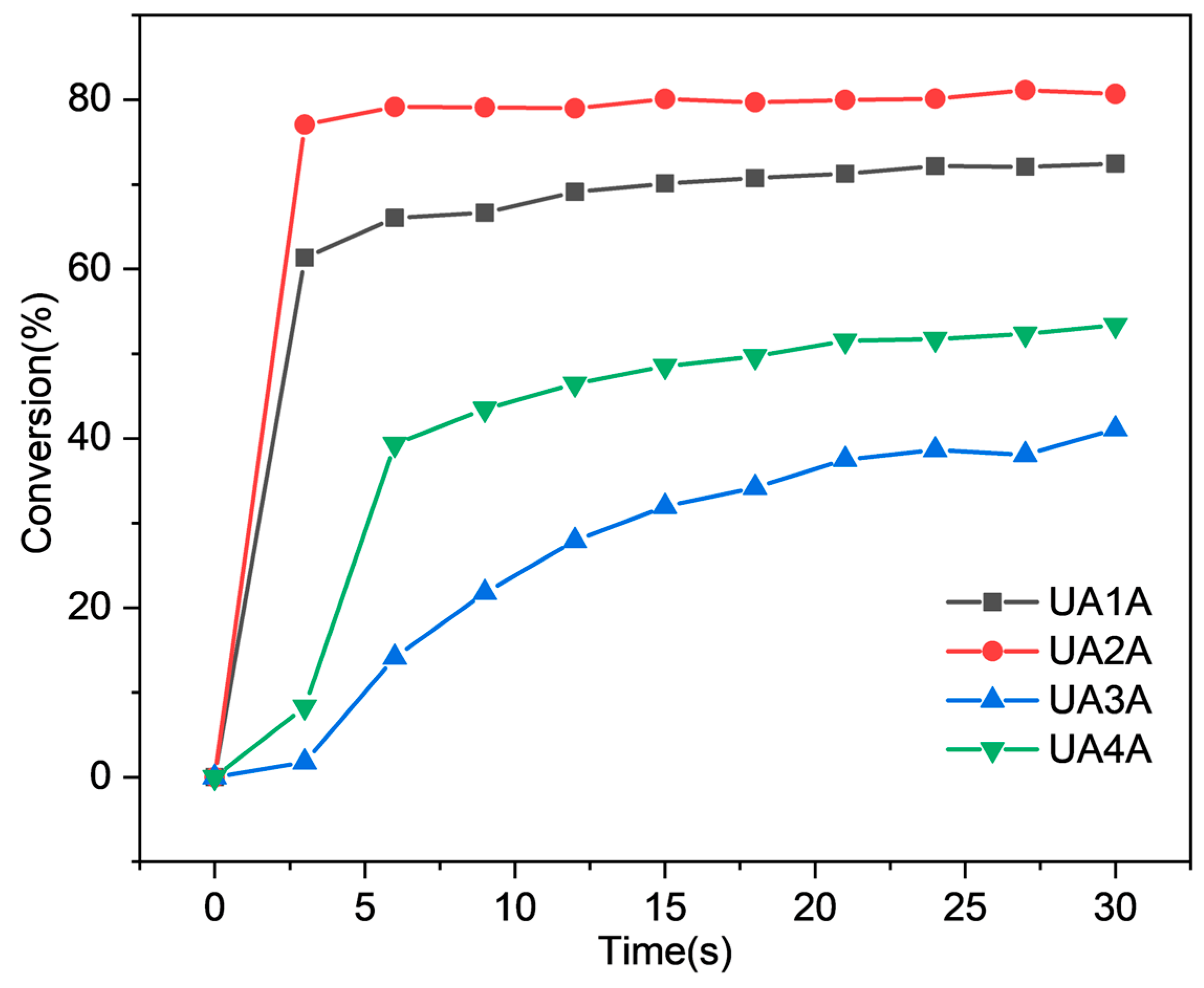

2.2. Photopolymerization Kinetics of UA

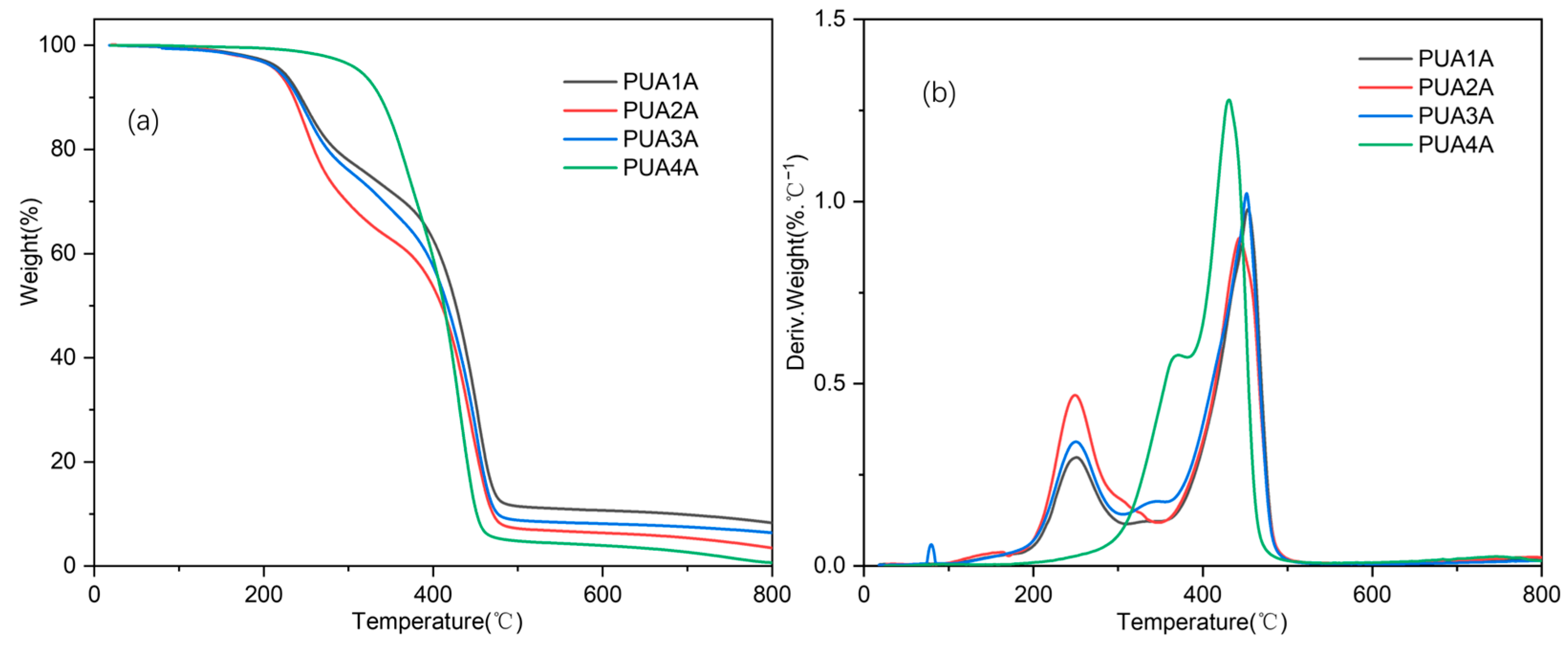

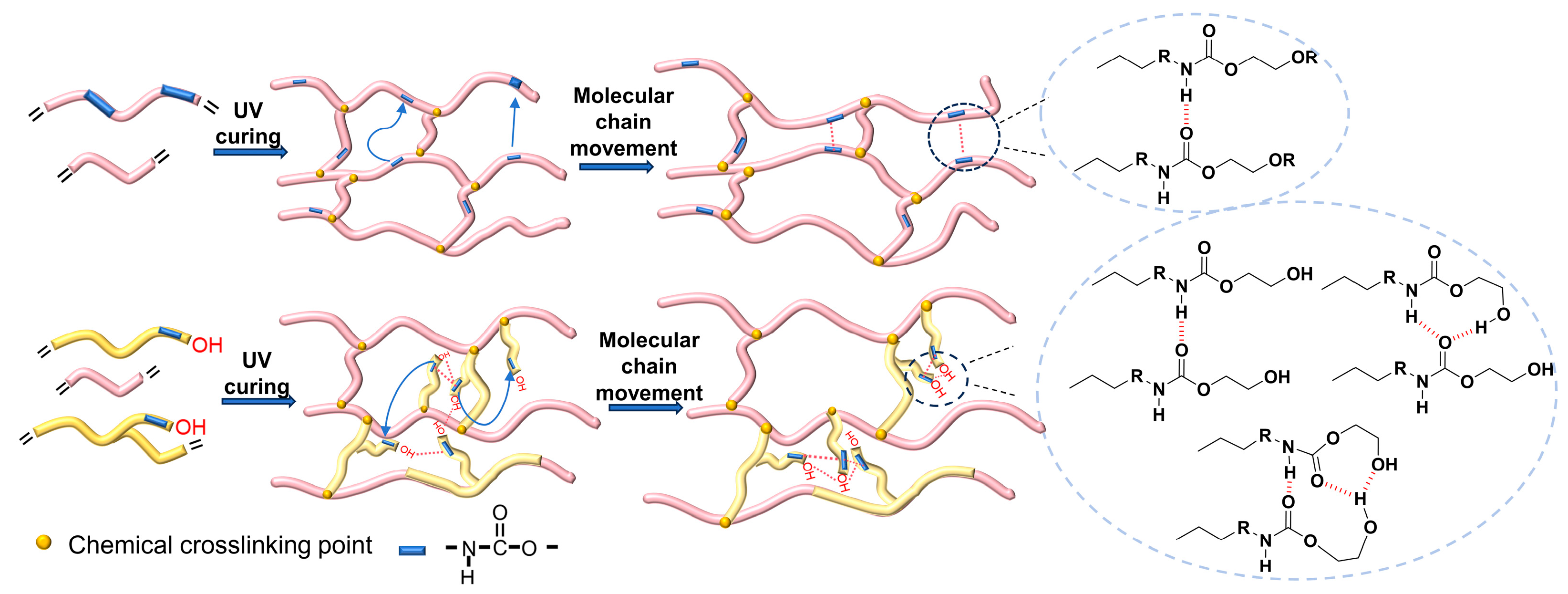

2.3. Thermal and Mechanical Properties of PUA1A~PUA4A

2.4. 3D Printing of PUA

3. Experimental

3.1. Materials and Methods

3.2. Synthesis of Urethane Acrylates

3.2.1. Synthesis of Urethane Acrylates by Non-Isocyanate Method

3.2.2. Synthesis of Urethane Acrylates by Traditional Method

3.3. Formulations of UV Curing Composites

3.4. Photopolymerization Kinetics

3.5. Volume Shrinkage and Gel Content

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rawat, R.S.; Chouhan, N.; Talwar, M.; Diwan, R.K.; Tyagi, A.K. UV coatings for wooden surfaces. Prog. Org. Coat. 2019, 135, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, M.Y.; Basirun, W.J.; Sarih, N.M.; Shalauddin, M.; Lee, S.Y.; Ang, D.T.-C. Utilization of liquid epoxidized natural rubber as prepolymer and crosslinker in development of UV-curable palm oil-based alkyd coating. React. Funct. Polym. 2023, 191, 105658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhu, G.; Zhang, J.; Huang, J.; Yu, X.; Shang, Q.; An, R.; Liu, C.; Hu, L.; Zhou, Y. Rubber Seed Oil-Based UV-Curable Polyurethane Acrylate Resins for Digital Light Processing (DLP) 3D Printing. Molecules 2021, 26, 5455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarczyk, P.; Walkowiak, K.; Irska, I. Epoxy (Meth)acrylate-Based Thermally and UV Initiated Curable Coating Systems. Polymers 2023, 15, 4664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Cheng, Q.; Weng, Y.; Ren, J. Synthesis and properties of UV-curable polyester acrylate resins from biodegradable poly(l-lactide) and poly(ε-caprolactone). React. Funct. Polym. 2020, 155, 104695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.; Cernadas, T.; Martins, P.; Miguel, S.P.; Correia, I.J.; Alves, P.; Ferreira, P. Polyester-based photocrosslinkable bioadhesives for wound closure and tissue regeneration support. React. Funct. Polym. 2021, 158, 104798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Hu, C.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Z.; Shu, J.; Gu, J. Modification of birch wood surface with silane coupling agents for adhesion improvement of UV-curable ink. Prog. Org. Coat. 2020, 148, 105833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, T.; Eschig, S.; Biemans, T.; Scheifler, F. Bio-based polyester itaconates as binder resins for UV-curing offset printing inks. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 2018, 16, 689–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Džunuzović, E.; Tasić, S.; Božić, B.; Jeremić, K.; Dunjić, B. Photoreactive hyperbranched urethane acrylates modified with a branched saturated fatty acid. React. Funct. Polym. 2006, 66, 1097–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grauzeliene, S.; Schuller, A.-S.; Delaite, C.; Ostrauskaite, J. Biobased vitrimer synthesized from 2-hydroxy-3-phenoxypropyl acrylate, tetrahydrofurfuryl methacrylate and acrylated epoxidized soybean oil for digital light processing 3D printing. Eur. Polym. J. 2023, 198, 112424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzana, L.; Melilli, G.; Guigo, N.; Sbirrazzuoli, N.; Sangermano, M. Photopolymerization of furan-based monomers: Exploiting UV-light for a new age of green polymers. React. Funct. Polym. 2023, 185, 105540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Back, J.H.; Kwon, Y.; Kim, H.J.; Yu, Y.; Lee, W.; Kwon, M.S. Visible-Light-Curable Solvent-Free Acrylic Pressure-Sensitive Adhesives via Photoredox-Mediated Radical Polymerization. Molecules 2021, 26, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernadas, T.; Santos, M.; Gonçalves, F.A.M.M.; Alves, P.; Correia, T.R.; Correia, I.J.; Ferreira, P. Functionalized polyester-based materials as UV curable adhesives. Eur. Polym. J. 2019, 120, 109196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Yang, Y.D.; Zhou, H.Y.; Li, Y.Q.; Wang, J.X. Novel polymerizable HMPP-type photoinitiator with carbamate: Synthesis and photoinitiating behaviors. Prog. Org. Coat. 2017, 110, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Zhou, L.; Soucek, M.D.; Wollyung, K.M.; Wesdemiotis, C. UV-curable hybrid coatings based on vinylfunctionlized siloxane oligomer and acrylated polyester. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2007, 105, 2376–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zhou, M.; Wu, B.; Jiang, Z.; Nie, J. Synthesis and properties of novel polyurethane acrylate containing 3-(2-hydroxyethyl) isocyanurate segment. Prog. Org. Coat. 2010, 67, 264–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohail, M.; Ashfaq, B.; Azeem, I.; Faisal, A.; Doğan, S.Y.; Wang, J.; Duran, H.; Yameen, B. A facile and versatile route to functional poly(propylene) surfaces via UV-curable coatings. React. Funct. Polym. 2019, 144, 104366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Wang, L.; Yu, H.; Haroon, M.; Haq, F.; Shi, W.; Wu, B.; Wang, L. Research progress of UV-curable polyurethane acrylate-based hardening coatings. Prog. Org. Coat. 2019, 131, 82–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delebecq, E.; Pascault, J.P.; Boutevin, B.; Ganachaud, F. On the versatility of urethane/urea bonds: Reversibility, blocked isocyanate, and non-isocyanate polyurethane. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 80–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Fan, Y.; He, N.; Song, Y.; Shen, J.; Gong, Z.; Tong, X.; Yang, X. Castor oil based high transparent UV cured silicone modified polyurethane acrylate coatings with outstanding tensile strength and good chemical resistance. Prog. Org. Coat. 2022, 163, 106624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hu, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X. Preparation of UV-curable strippable coatings based on polyurethane acrylate from CO2-polyol and different isocyanates. Prog. Org. Coat. 2023, 184, 107865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraskar, P.M.; Hatkar, V.M.; Kulkarni, R.D. Facile synthesis and characterization of renewable dimer acid-based urethane acrylate oligomer and its utilization in UV-curable coatings. Prog. Org. Coat. 2020, 149, 105946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assumption, H.J.; Mathias, L.J. Photopolymerization of urethane dimethacrylates synthesized via a non-isocyanate route. Polymer 2003, 44, 5131–5136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Wang, X.; Ocepek, M.; Soucek, M.D. A new class of non-isocyanate urethane methacrylates for the urethane latexes. Polymer 2017, 109, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boisaubert, P.; Kébir, N.; Schuller, A.-S.; Burel, F. Photo-crosslinked Non-Isocyanate Polyurethane Acrylate (NIPUA) coatings through a transurethane polycondensation approach. Polymer 2020, 206, 122855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dave, P.N.; Patel, N.N. Studies on novel interpenetrating networks of urethane modified poly(ester-amide) and vinyl ester of bisphenol-C. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2016, 20, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabalinia, N.; Farkhondehnia, M.; Marić, M. Synthesis and characterization of waterborne bio-based hybrid isocyanate-free poly (hydroxy urethane)-poly(methacrylate) latexes with vitrimeric properties. React. Funct. Polym. 2024, 194, 105799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.; Lecamp, L.; Labib, H.; Aloui, F.; Kébir, N.; Burel, F. Synthesis and properties of allyl terminated renewable non-isocyanate polyurethanes (NIPUs) and polyureas (NIPUreas) and study of their photo-crosslinking. Eur. Polym. J. 2016, 84, 828–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wołosz, D.; Parzuchowski, P.G.; Rolińska, K. Environmentally Friendly Synthesis of Urea-Free Poly(carbonate-urethane) Elastomers. Macromolecules 2022, 55, 4995–5008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.N.; Wang, Y.M.; Li, X.Y.; Zhang, J.Y.; Zhao, J.B. High-performance epoxy hybrid non-isocyanate polyurethanes prepared from diol-cyclocarbonation bisphenol A dicyclocarbonate. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2023, 63, 3025–3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimpf, V.; Asmacher, A.; Fuchs, A.; Bruchmann, B.; Mülhaupt, R. Polyfunctional Acrylic Non-isocyanate Hydroxyurethanes as Photocurable Thermosets for 3D Printing. Macromolecules 2019, 52, 3288–3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zareanshahraki, F.; Asemani, H.R.; Skuza, J.; Mannari, V. Synthesis of non-isocyanate polyurethanes and their application in radiation-curable aerospace coatings. Prog. Org. Coat. 2020, 138, 105394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namikoshi, T.; Hashimoto, T.; Shikano, N.; Urushisaki, M.; Sakaguchi, T. Syntheses of poly (vinyl ether) s containing hydroxyurethanes by reaction of cyclic carbonate with alkanolamines and their characterizations. Polym. Bull. 2023, 80, 3689–3701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Soucek, M.D. Investigation of non-isocyanate urethane dimethacrylate reactive diluents for UV-curable polyurethane coatings. Prog. Org. Coat. 2013, 76, 1057–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Yang, W. Synthesis and characterization of aliphatic thermoplastic poly(ether urethane) elastomers through a non-isocyanate route. Polymer 2015, 57, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotanen, S.; Laaksonen, T.; Sarlin, E. Feasibility of polyamines and cyclic carbonate terminated prepolymers in polyurethane/polyhydroxyurethane synthesis. Mater. Today Commun. 2020, 23, 100863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janvier, M.; Ducrot, P.-H.; Allais, F. Isocyanate-Free Synthesis and Characterization of Renewable Poly(hydroxy)urethanes from Syringaresinol. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 8648–8656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Xie, T.; Qiu, R. Improvement of properties for biobased composites from modified soybean oil and hemp fibers: Dual role of diisocyanate. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2016, 90, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Zhang, R.; Liu, W.; Zhu, J.; Dong, X.; Guo, H.; Hu, G.-H. A Multiscale Investigation on the Mechanism of Shape Recovery for IPDI to PPDI Hard Segment Substitution in Polyurethane. Macromolecules 2016, 49, 5931–5944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Wu, G.; Huo, S.; Jin, C.; Kong, Z. Synthesis and properties of non-isocyanate polyurethane coatings derived from cyclic carbonate-functionalized polysiloxanes. Prog. Org. Coat. 2017, 112, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Cai, W.; Chen, R.; Qu, J. Synthesis and properties of ambient-curable non-isocyanate polyurethanes. Prog. Org. Coat. 2018, 119, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Dai, J.; Tang, L.; Qu, J. Sorbitol-based aqueous cyclic carbonate dispersion for waterborne nonisocyanate polyurethane coatings via an environment-friendly route. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 2018, 16, 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhshi, H.; Yeganeh, H.; Mehdipour-Ataei, S.; Solouk, A.; Irani, S. Polyurethane Coatings Derived from 1,2,3-Triazole-Functionalized Soybean Oil-Based Polyols: Studying their Physical, Mechanical, Thermal, and Biological Properties. Macromolecules 2013, 46, 7777–7788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.Y.; Luo, L.P.; Zhou, H.Y.; Wang, J.X. Novel phenolic modified acrylates: Synthesis, characterization and application in 3D printing. Eur. Polym. J. 2023, 192, 112075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, X.; Yang, Z.; Yuan, T. A novel multi-functional bio-based reactive diluent derived from cardanol for high bio-content UV-curable coatings application. Prog. Org. Coat. 2020, 148, 105880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Hao, Y.; Zhong, M.; Tang, L.; Nie, J.; Zhu, X. Synthesis of furan derivative as LED light photoinitiator: One-pot, low usage, photobleaching for light color 3D printing. Dyes Pigments 2019, 165, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Tang, L.; Qu, J. Synthesis and photopolymerization of novel UV-curable macro-photoinitiators. Prog. Org. Coat. 2020, 141, 105546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | T5% (°C) | Modulus of Elasticity (MPa) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Elongation at Break (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PUA1A | 222 | 97.0 ± 4.2 | 21.3 ± 0.8 | 16.7 ± 1.9 |

| PUA2A | 215 | 184.4 ± 5.0 | 24.4 ± 0.8 | 14.7 ± 0.5 |

| PUA3A | 216 | 107.9 ± 8.8 | 20.7 ± 2.1 | 14.8 ± 0.6 |

| PUA4A | 311 | 416.2 ± 13.6 | 16.4 ± 1.3 | 10.8 ± 0.6 |

| Sample | The Main Composition |

|---|---|

| UA1 | IPDA-EC-NPGDA, IPDA-EC-2NPGDA, IPDA-2NPGDA, IPDA-3NPGDA, NPGDA |

| UA2 | NPGDA, IPDA-EC-NPGDA, IPDA-2NPGDA |

| UA3 | NPGDA, IPDA-2NPGDA, IPDA-EC-NPGDA |

| UA4 | IPDI-2HEMA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, X.; Zan, X.; Yin, J.; Wang, J. Non-Isocyanate Urethane Acrylate Derived from Isophorone Diamine: Synthesis, Characterization and Its Application in 3D Printing. Molecules 2024, 29, 2639. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29112639

Zhang X, Zan X, Yin J, Wang J. Non-Isocyanate Urethane Acrylate Derived from Isophorone Diamine: Synthesis, Characterization and Its Application in 3D Printing. Molecules. 2024; 29(11):2639. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29112639

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Xinqi, Xinxin Zan, Jiangdi Yin, and Jiaxi Wang. 2024. "Non-Isocyanate Urethane Acrylate Derived from Isophorone Diamine: Synthesis, Characterization and Its Application in 3D Printing" Molecules 29, no. 11: 2639. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29112639