Bio-Based Self-Healing Epoxy Vitrimers with Dynamic Imine and Disulfide Bonds Derived from Vanillin, Cystamine, and Dimer Diamine

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

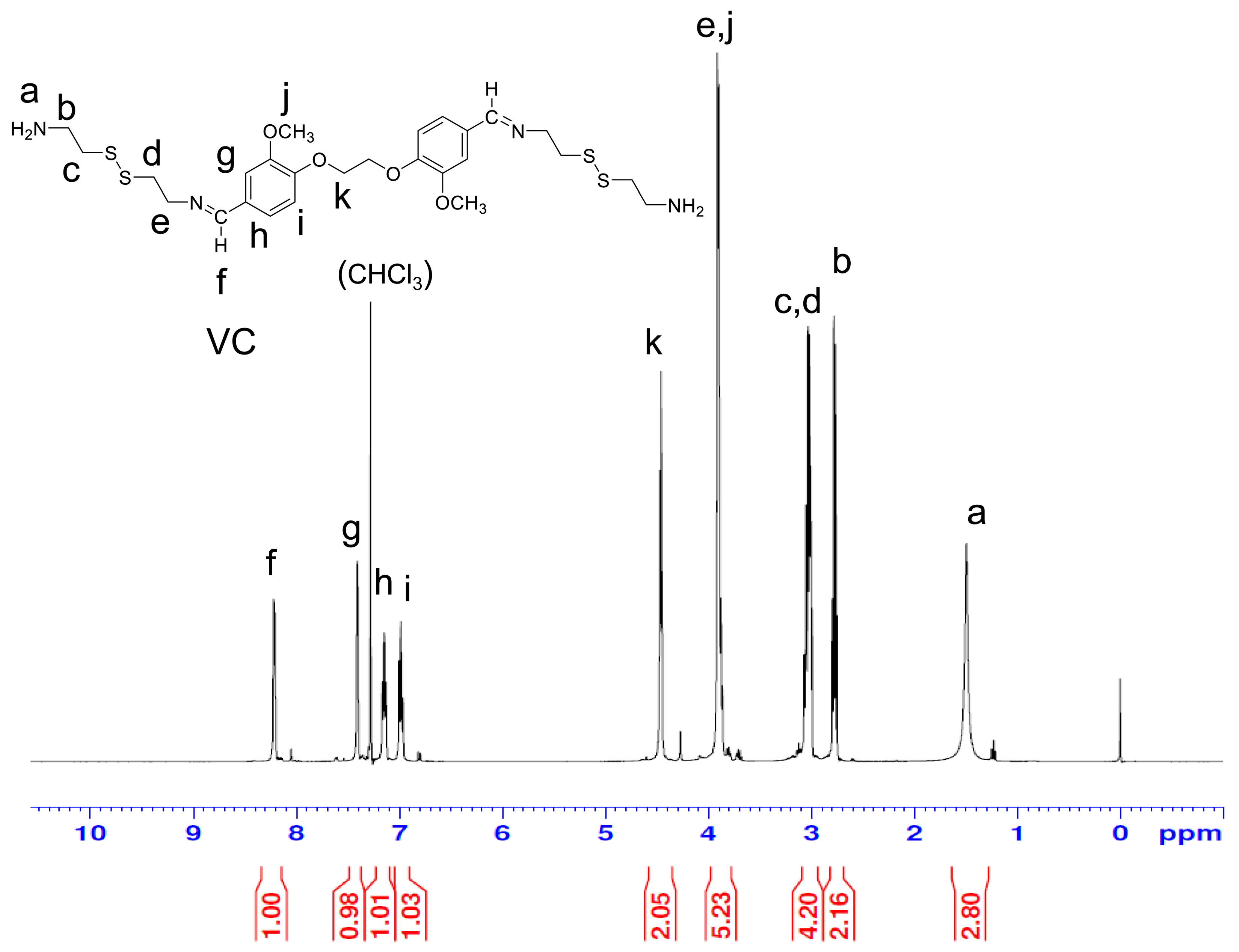

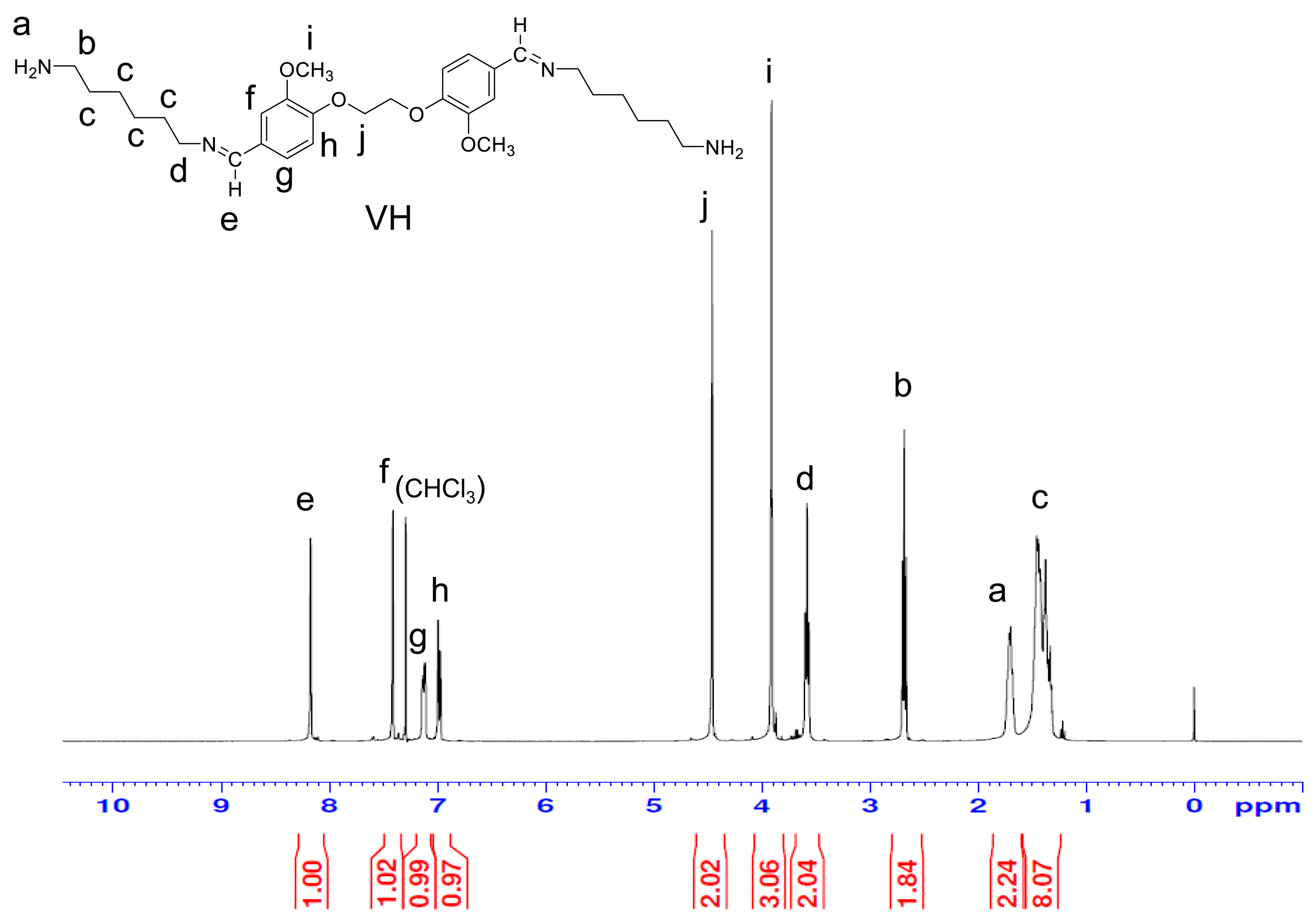

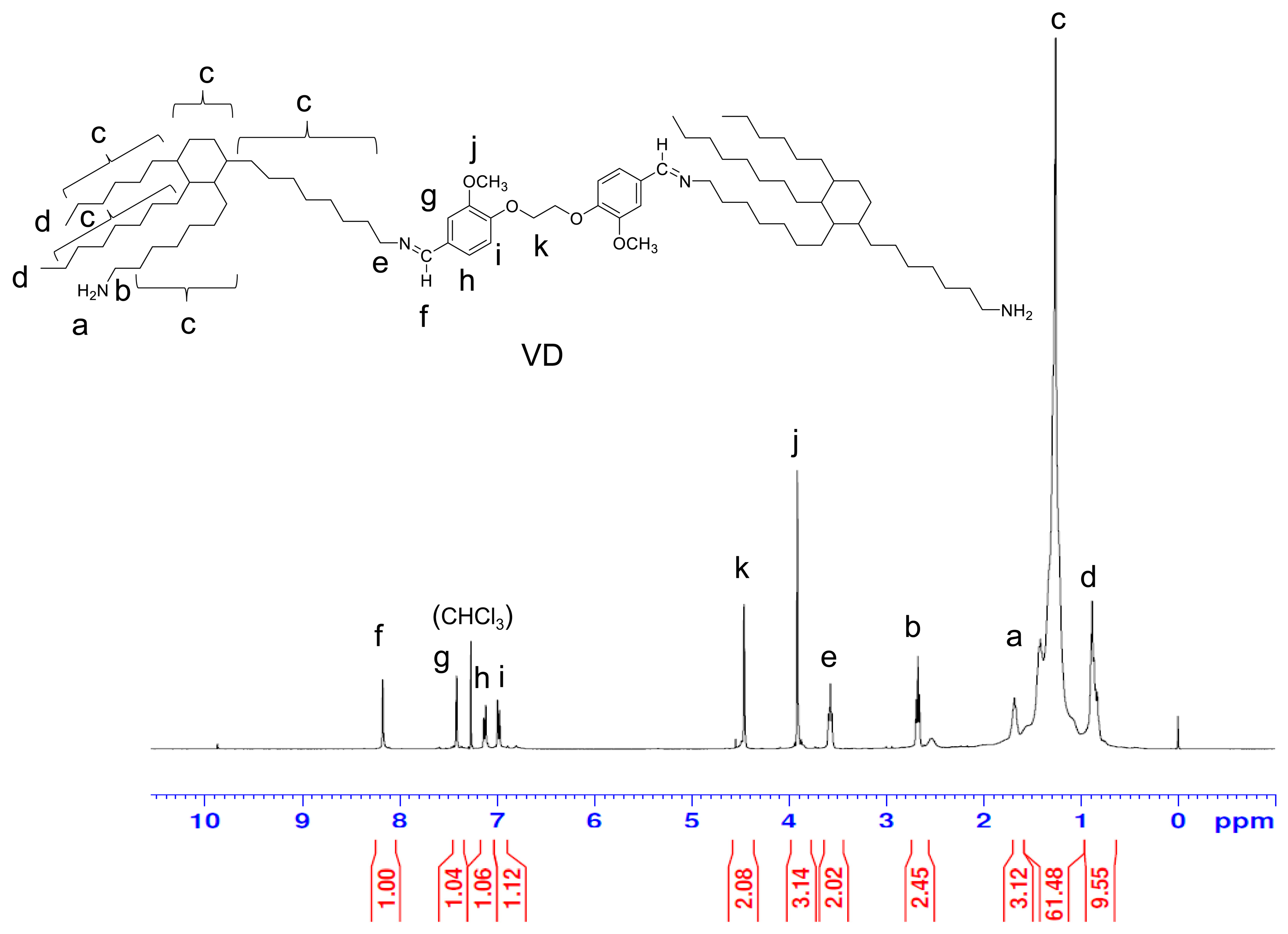

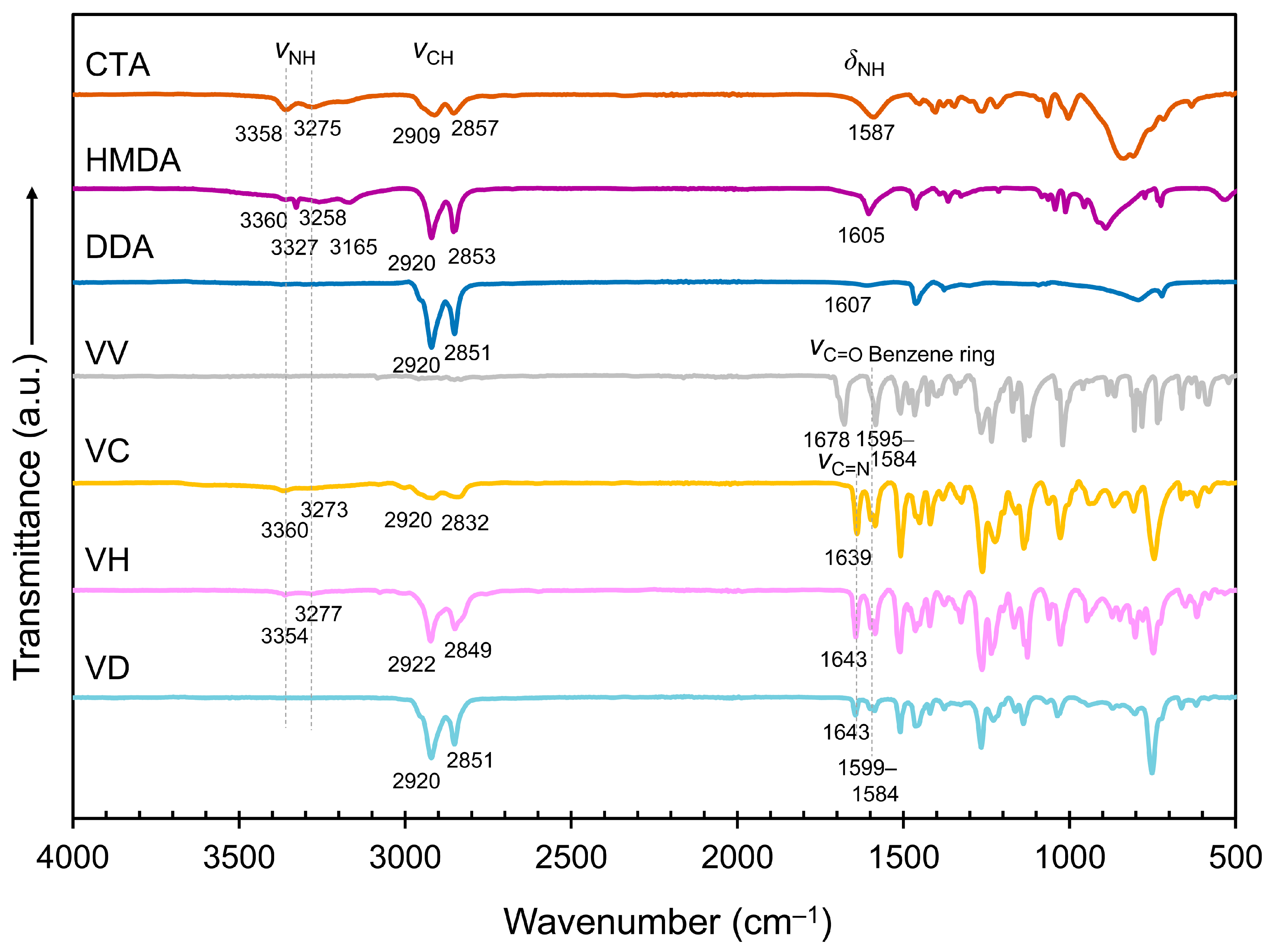

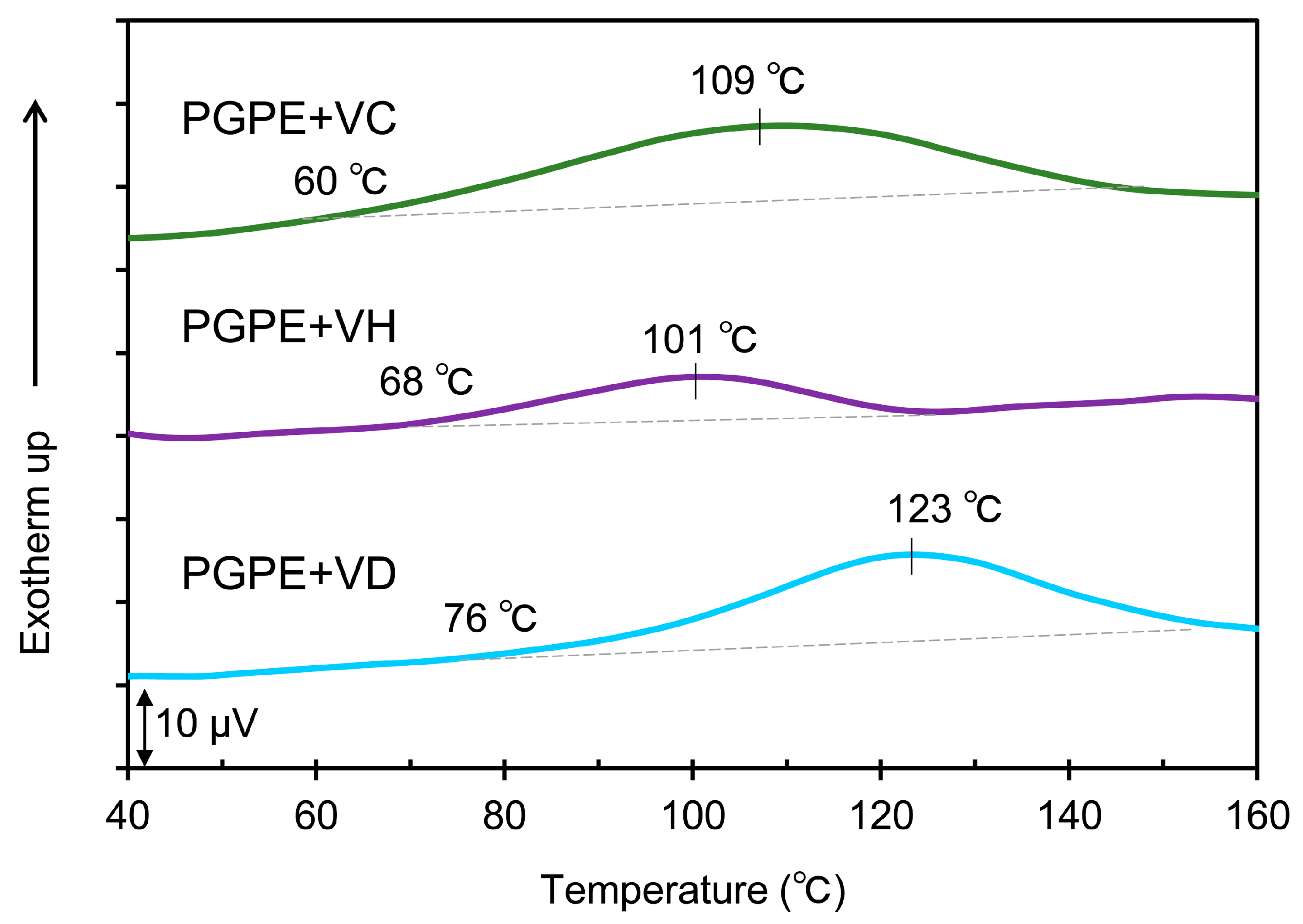

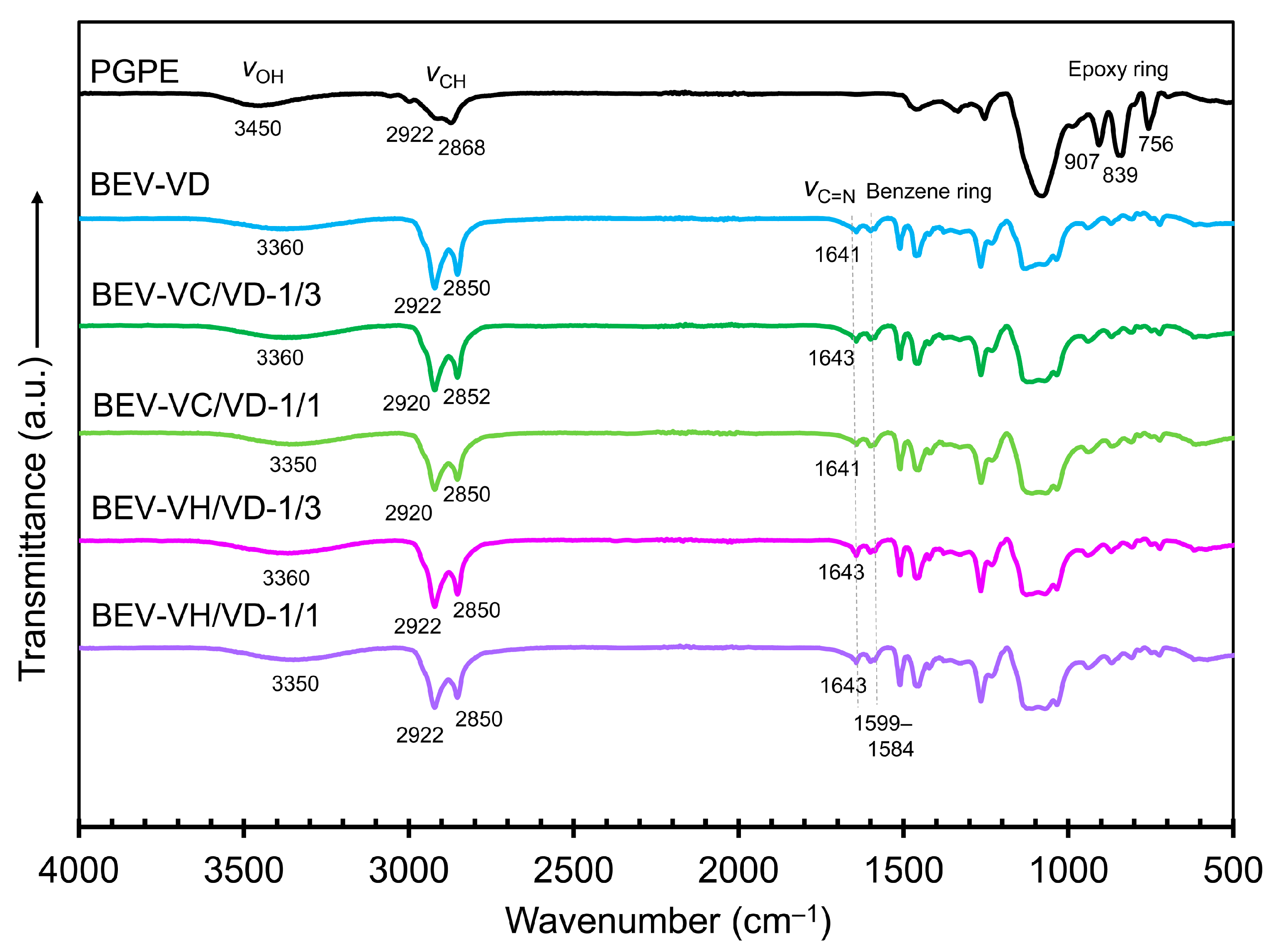

2.1. Preparation and Characterization of the BEV-VC/VD and BEV-VH/VD Films

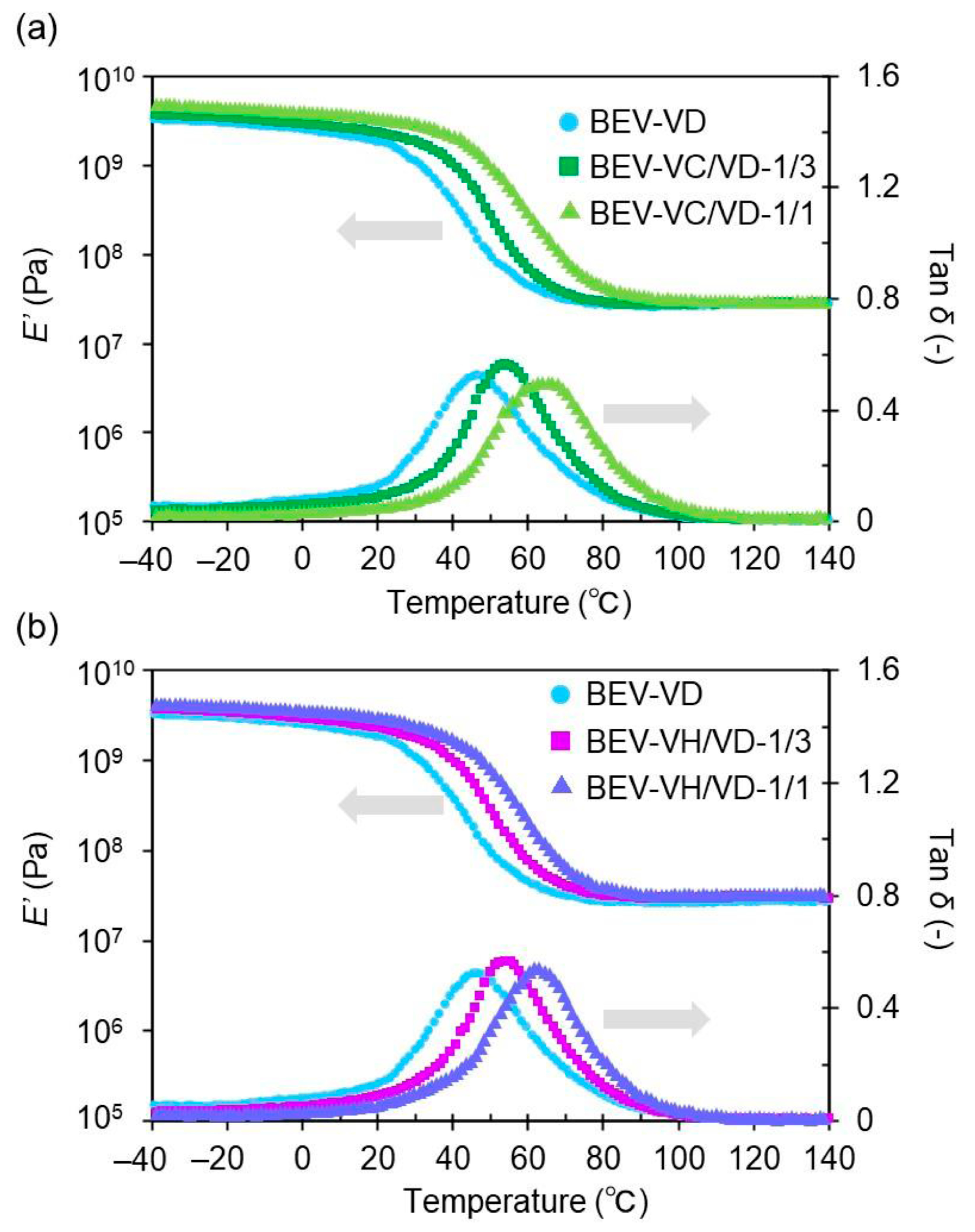

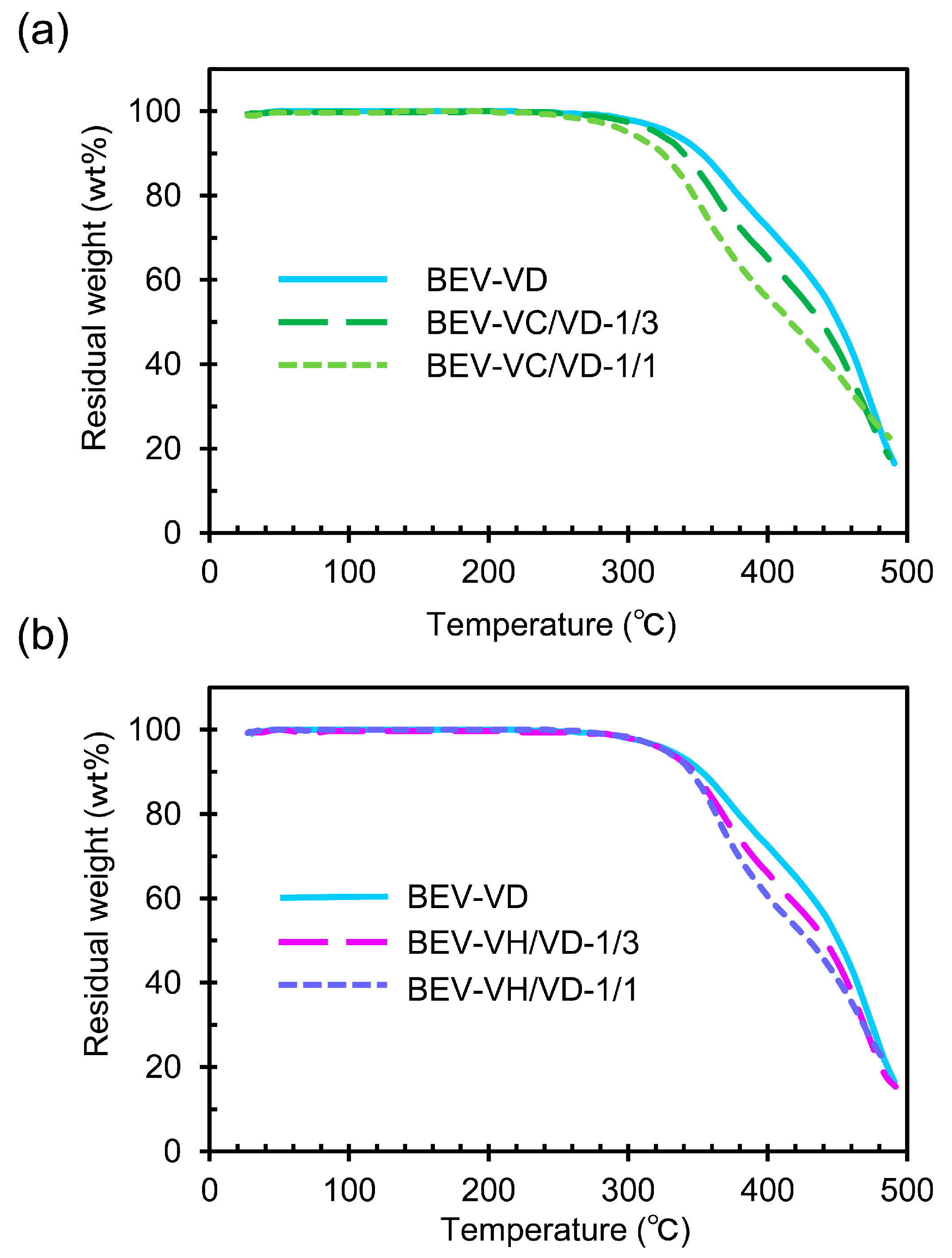

2.2. Thermal Properties of the BEV-VD, BEV-VC/VD, and BEV-VH/VD Films

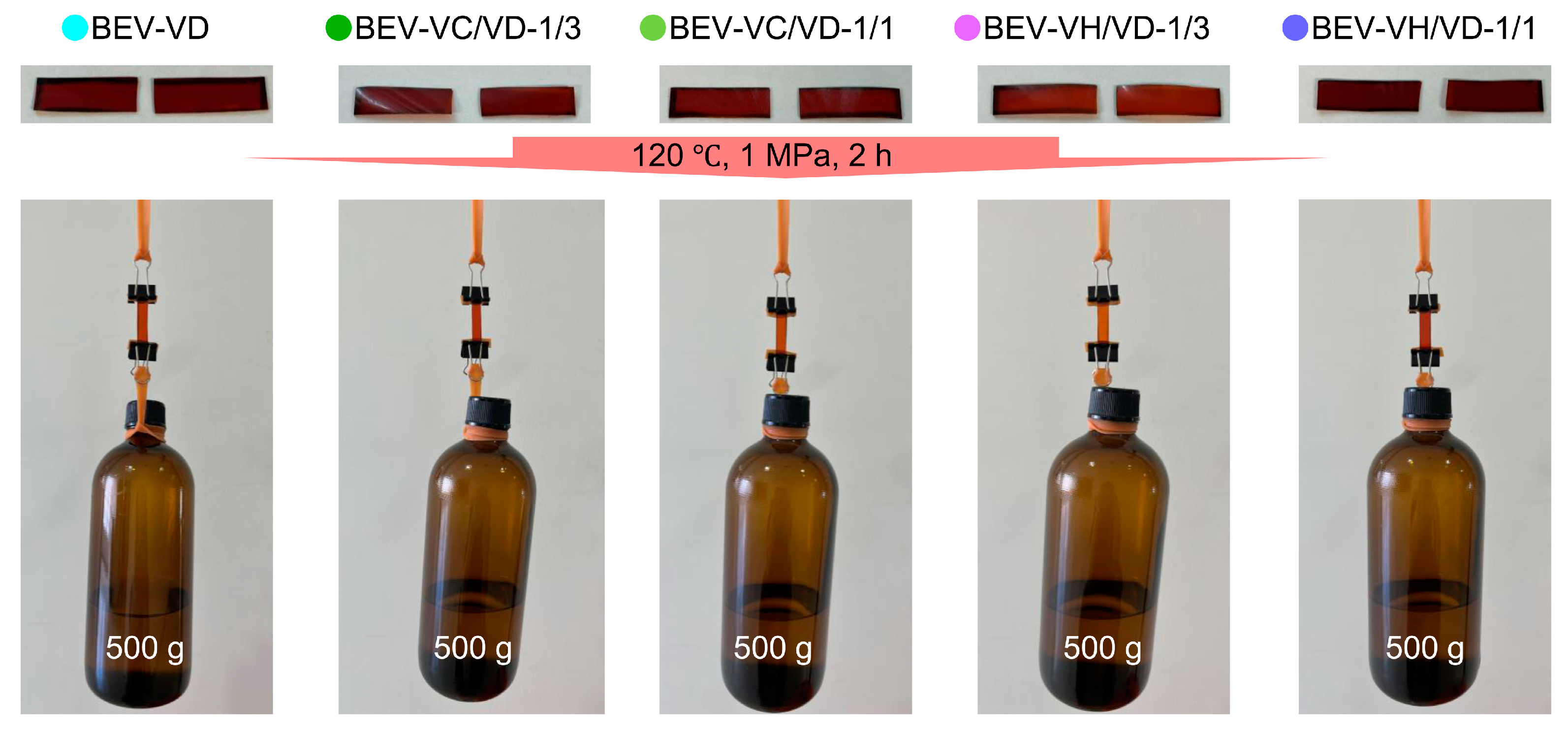

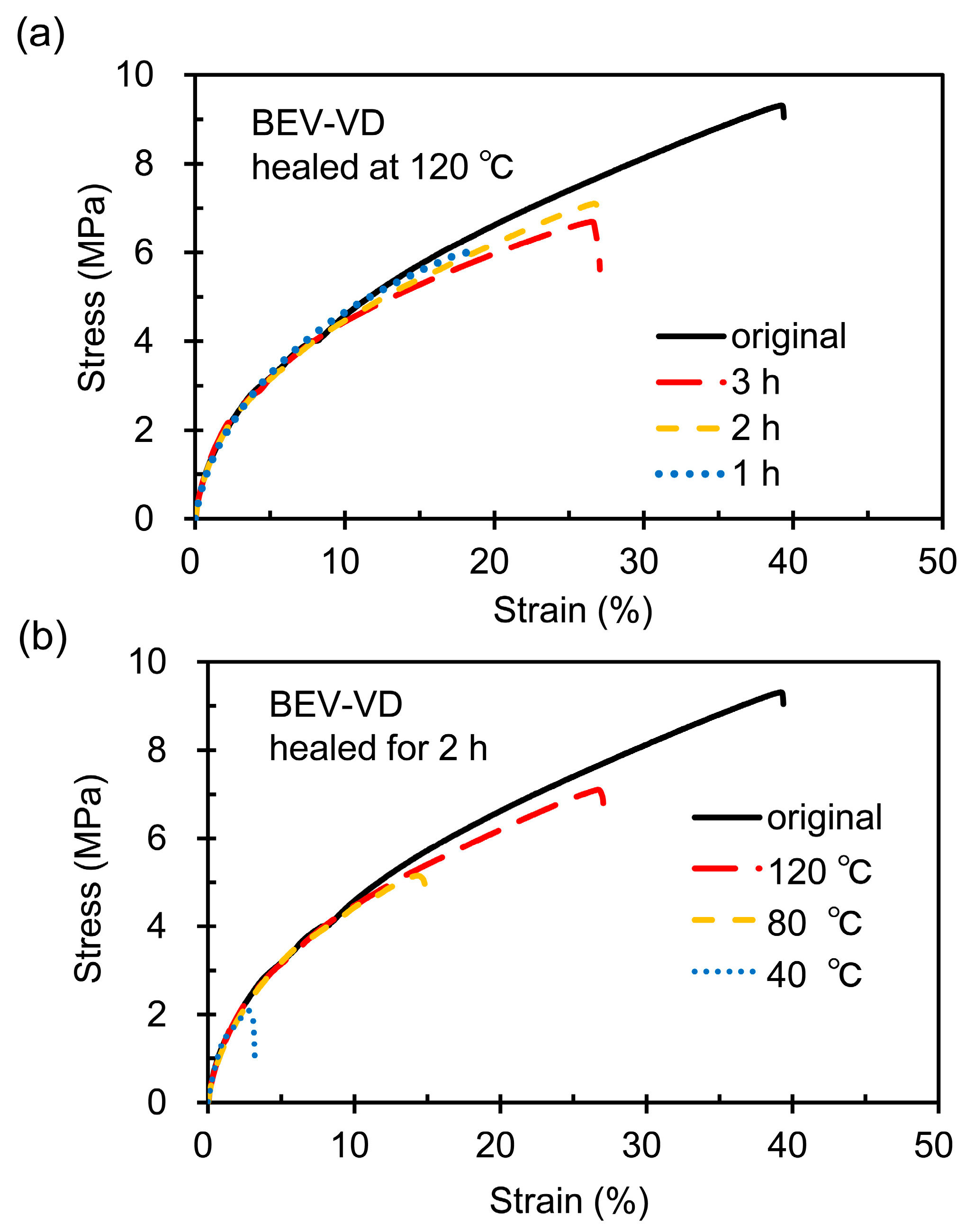

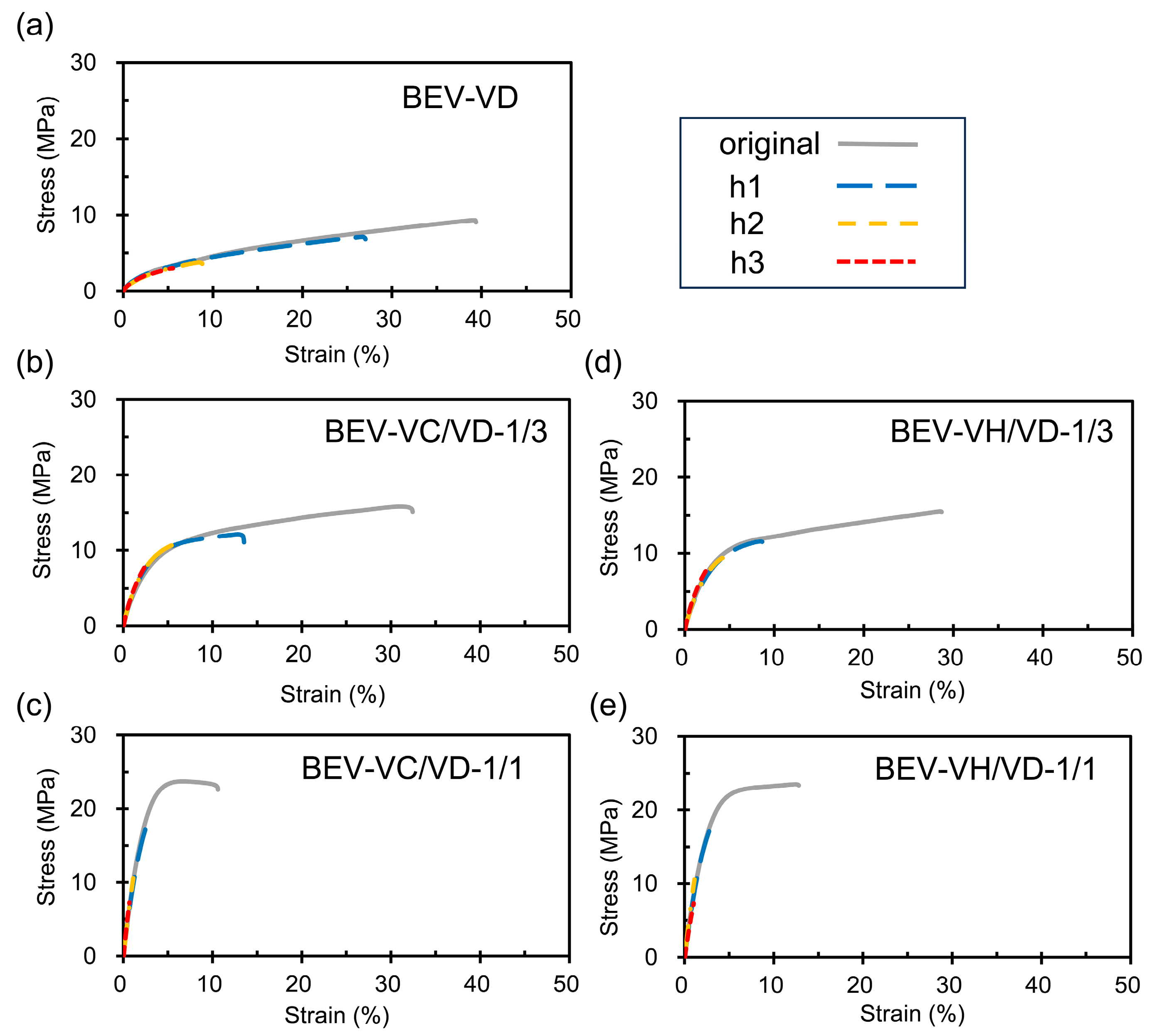

2.3. Mechanical and Self-Healing Properties of the BEV-VD, BEV-VC/VD, and BE-VH/VD Films

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

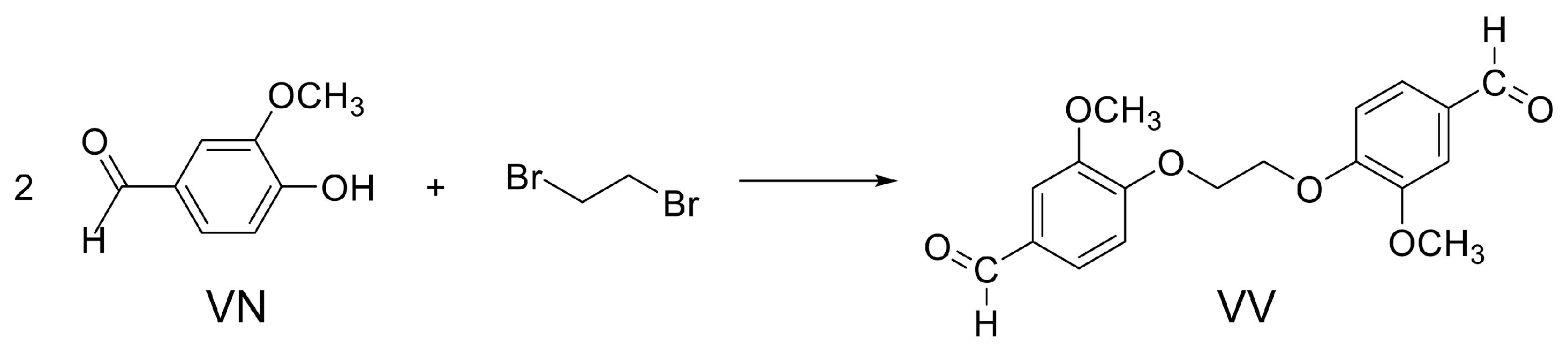

3.2. Synthesis of VV

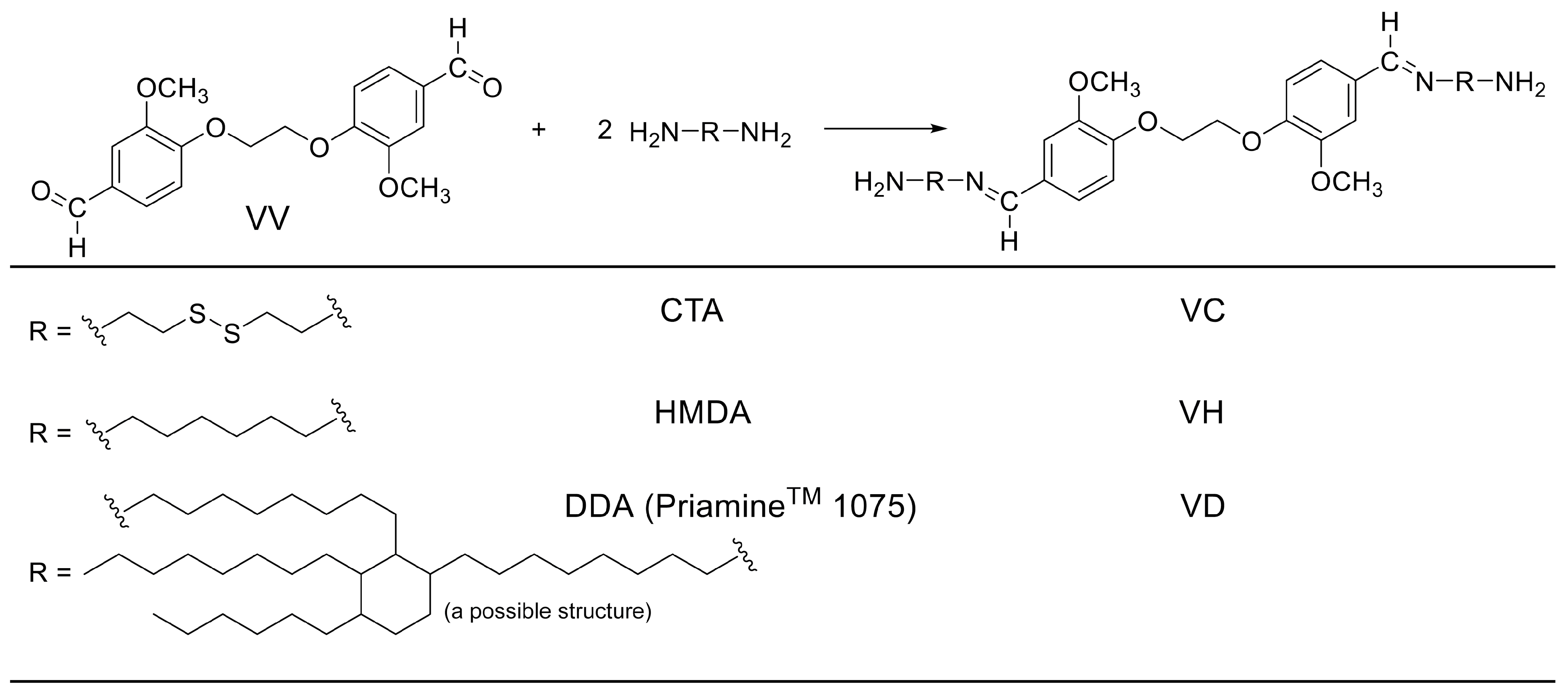

3.3. Synthesis of VC, VH, and VD

3.4. Preparation of BEV-VD, BEV-VC/VD, and BEV-VH/VD Films

3.5. Self-Healing Analysis Experiments

3.6. Measurements

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Memon, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhu, C. Recyclable and reformable epoxy resins based on dynamic covalent bonds—Present, past, and future. Polym. Test. 2022, 105, 107420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucherelli, M.A.; Duval, A.; Avérous, L. Biobased vitrimers: Towards sustainable and adaptable performing polymer materials. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2022, 127, 101515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnakumar, B.; Pucci, A.; Wadgaonkar, P.P.; Kumar, I.; Binder, W.H.; Rana, S. Vitrimers based on bio-derived chemicals: Overview and future prospects. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 433, 133261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, K.L.; Lai, J.C.; Rahman, R.A.; Adrus, N.; Al-Saffar, Z.H.; Hassan, A.; Lim, T.H.; Wahit, M.U. A review on recent approaches to sustainable bio-based epoxy vitrimer from epoxidized vegetable oils. Ind. Crops. Prod. 2022, 189, 115857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ma, F.; Shi, L.; Lyu, B.; Ma, J. Recyclable, repairable, and malleable bio-based epoxy vitrimers: Overview and future prospects. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2023, 39, 100726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Lin, H.; Lin, B.; Tang, D.; Xu, J.; Dai, L.; Si, C. From biomass to vitrimers: Latest developments in the research of lignocellulose, vegetable oil, and naturally-occurring carboxylic acids. Ind. Crops. Prod. 2023, 206, 117690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangermano, M.; Bergoglio, M.; Schögl, S. Biobased vitrimetric epoxy networks. Macromol. Mater. Engn. 2024, 309, 2300371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Krishnan, S.; Prabakaran, K. Renewable resource-based epoxy vitrimer composites for future application: A comprehensive review. ACS Sustain. Resour. Manag. 2024, 1, 1874–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fache, M.; Boutevin, B.; Caillol, S. Vanillin, a key-intermediate of biobased polymers. Eur. Polym. J. 2015, 68, 488–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguori, A.; Hakkarainen, M. Designed from biobased materials for recycling: Imine-based covalent adaptable networks. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2022, 43, 2100816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, H.; Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Zhu, Y. From vanillin to biobased aromatic polymers. Polym. Chem. 2023, 14, 4255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Abu-Omar, M.M. Recyclable and malleable epoxy thermoset bearing aromatic imine bonds. Macromolecules 2018, 51, 9816–9824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Peng, X.; Wang, Y.; Geng, H.; Xu, A.; Zhang, X.; Xu, W.; Ye, D. Vanillin-based degradable epoxy vitrimers: Reprocessability and mechanical properties study. Eur. Polym. J. 2019, 117, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, H.; Liu, H.; Rashid, M.A.; Chen, L.; Jiang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Wei, Y.; Liu, W.; Qiu, Y. Vanillin-based epoxy vitrimer with high performance and closed-loop recyclability. Macromolecules 2020, 53, 621630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-Y.; Hew, J.; Li, Y.-D.; Zhao, X.-L.; Zeng, J.-B. Biobased epoxy vitrimer from epoxidized soybean oil for reprocessable and recyclable carbon fiber reinforced composite. Compos. Commun. 2020, 22, 100445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liang, L.; Lu, M.; Song, X.; Liu, H.; Chen, G. Water-resistant bio-based vitrimers based on dynamic imine bonds: Self-healability, remodelability and ecofriendly recyclability. Polymer 2020, 210, 123030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.-L.; Liu, Y.-Y.; Weng, Y.; Li, Y.-D.; Zeng, J.-B. Sustainable epoxy vitrimers from epoxidized soybean oil and vanillin. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 15020–15029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, E.; Feng, Z.; Liu, J.; Chen, B.; Liang, L. Degradable bio-based epoxy vitrimers based on imine chemistry and their application in recyclable carbon fiber composites. J. Mater. Sci. 2021, 56, 15733–15751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhu, C. Correlating the thermomechanical properties of a novel bio-based epoxy vitrimer with its crosslink density. Mater. Today Commun. 2021, 29, 102814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-Y.; Liu, G.-L.; Li, Y.-D.; Weng, Y.; Zeng, J.-B. Biobased high-performance epoxy vitrimer with UV shielding for recyclable carbon fiber reinforced composites. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 4638–4647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roig, A.; Hidalgo, P.; Ramis, X.; Flor, S.D.; Serra, À. Vitrimeric epoxy-amine polyimine networks based on a renewable vanillin derivative. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2022, 4, 9341–9350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, P.-X.; Li, Y.-D.; Weng, Y.; Hu, Z.; Zeng, J.-B. Reprocessable, chemically recyclable, and flame-retardant biobased epoxy vitrimers. Eur. Polym. J. 2023, 193, 112078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.A.; Mian, M.M.; Wei, Y.; Liu, W. A vanillin-derived hardener for recyclable, degradable and self-healable high-performance epoxy vitrimers based on transamination. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 35, 106178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xu, H.; Xia, Z.; Zheng, J.; Wu, J. Extrudable, robust and recyclable bio-based epoxy vitrimer via tailoring the topology of a dual dynamic-covalent-bond network. Polymer 2023, 289, 126487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteserin, C.; Blanco, M.; Uranga, N.; Sanchez, J.; Laza, J.M.; Vilas, J.L.; Aranzabe, E. Sustainable biobased epoxy thermosets with covalent dynamic imine bonds for green composite development. Polymer 2023, 285, 126339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.A.; Zhu, S.; Zhang, L.; Jin, K.; Liu, W. High-performance and fully recyclable epoxy resins cured by imine-containing hardeners derived from vanillin and syringaldehyde. Eur. Polym. J. 2023, 187, 111878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.-H.; Ao, X.; Islam, M.; Liu, Y.-Y.; Prolomgo, S.G.; Wang, D.-Y. Bio-based epoxy vitrimer with inherent excellent flame retardance and recyclability via molecular design. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 262, 129363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guggari, S.; Magliozzi, F.; Malburet, S.; Graillot, A.; Destareac, M.; Guerre, M. Vanillin-based dual dynamic epoxy building block: A promising accelerator for disulfide vitrimers. Polym. Chem. 2024, 15, 1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Bai, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Hou, W. Bio-based epoxy vitrimer: Fast self-repair under acid-thermal stimulation. J. Mater. Sci. 2024, 59, 12111–12127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Bai, X.; Wang, Y.; Hou, W.; Huang, Y. Catalyst-free and sustainable bio-based epoxy vitrimer prepared based on ester exchange and imine bonding. J. Polym. Environ. 2024, 32, 4912–4924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdugo, P.; Santiago, D.; Flor, S.D.; Serra, À. A biobased epoxy vitrimer with dual relaxation mechanism: A promising material for renewable, reusable, and recyclable adhesives and composites. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 5965–5978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lari, G.M.; Pastore, G.; Mondelli, C.; Pérez-Ramirez, J. Towards sustainable manufacture of epichlorohydrin from glycerol using hydrotalcite derived basic oxides. Green Chem. 2018, 20, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morodo, R.; Gérardy, R.; Petit, G.; Monbaliu, J.-C.M. Continuous flow upgrading of glycerol toward oxiranes and active pharmaceutical ingredients thereof. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 4422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, Z.A.A.; Blencowe, A.; Ozcelik, B.; Palmer, J.A.; Stevens, G.W.; Abberton, K.M.; Morrison, W.A.; Penington, A.J.; Oiao, G.G. Epoxy-amine synthesised hydrogel scaffolds for soft-tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 6454–6467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pemba, A.G.; Rostagno, M.; Lee, T.A.; Miller, S.A. Cyclic and spirocyclic polyacetal ethers from lignin-based aromatics. Polym. Chem. 2014, 5, 3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverria-Altuna, O.; Ollo, O.; Larraza, I.; Gabilondo, N.; Harismendy, I.; Eceiza, A. Effect of the biobased polyols chemical structure on high performance thermoset polyurethane properties. Polymer 2022, 63, 125515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, M.; Ishigami, N.; Shibita, A. Synthesis of sugar alcohol-derived water-soluble polyamines by the thiolene reaction and their utilization as hardeners of water-soluble bio-based epoxy resins. React. Funct. Polym. 2017, 118, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Tα (°C) | E′ (MPa) at 20 °C | E′ (MPa) at (Tα + 50) °C | ve (mmol cm–3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BEV-VD | 46.5 | 1875 | 26.43 | 2.87 |

| BEV-VC/VD-1/3 | 53.8 | 2350 | 27.60 | 2.94 |

| BEV-VC/VD-1/1 | 65.3 | 3361 | 30.11 | 3.11 |

| BEV-VH/VD-1/3 | 55.2 | 2351 | 31.09 | 3.30 |

| BEV-VH/VD-1/1 | 61.6 | 3026 | 32.22 | 3.36 |

| Sample | Td5% (°C) | Td10% (°C) | Td50% (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BEV-VD | 330 | 353 | 450 |

| BEV-VC/VD-1/3 | 321 | 341 | 438 |

| BEV-VC/VD-1/1 | 303 | 325 | 416 |

| BEV-VH/VD-1/3 | 327 | 346 | 440 |

| BEV-VH/VD-1/1 | 327 | 345 | 429 |

| VC | 147 | 179 | 359 |

| VH | 131 | 206 | 398 |

| VD | 337 | 376 | 462 |

| Sample | ησ (%) of h1-Sample | ησ (%) of h2-Sample | ησ (%) of h3-Sample | Imine Content (wt%) | Disulfide Content (wt%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BEV-VD | 74.7 ± 8.9 | 39.4 ± 4.1 | 32.8 ± 1.3 | 2.6 | - |

| BEV-VC/VD-1/3 | 77.8 ± 5.0 | 61.2 ± 7.5 | 48.4 ± 3.1 | 2.9 | 1.7 |

| BEV-VC/VD-1/1 | 76.8 ± 3.9 | 46.3 ± 3.3 | 33.6 ± 4.5 | 3.2 | 3.8 |

| BEV-VH/VD-1/3 | 75.5 ± 6.7 | 56.0 ± 4.8 | 41.4 ± 2.7 | 2.9 | - |

| BEV-VH/VD-1/1 | 76.3 ± 6.7 | 46.3 ± 4.8 | 31.6 ± 1.5 | 3.3 | - |

| Sample | VC *1 | VH *1 | VD *1 | PGPE *2 g (mmol-epoxy) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VV g (mmol-CHO) | CTA g (mmol-NH2) | VV g (mmol-CHO) | HMDA g (mmol-NH2) | VV g (mmol-CHO) | DDA g (mmol-NH2) | ||

| BEV-VD | 0.948 (5.74) | - | - | 3.13 (11.48) | 1.92 (11.48) | ||

| BEV-VC/VD-1/3 | 0.262 (1.58) | 0.241 (3.17) | - | 0.785 (4.75) | 2.59 (9.51) | 2.12 (12.67) | |

| BEV-VC/VD-1/1 | 0.584 (3.53) | 0.538 (7.07) | - | 0.584 (3.53) | 1.93 (7.07) | 2.37 (14.14) | |

| BEV-VH/HD-1/3 | - | - | 0.264 (1.60) | 0.186 (3.20) | 0.793 (4.80) | 2.61 (9.60) | 2.14 (12.80) |

| BEV-VH/VD-1/1 | - | - | 0.597 (3.61) | 0.420 (7.22) | 0.597 (3.61) | 1.97 (7.22) | 2.42 (14.45) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abe, I.; Shibata, M. Bio-Based Self-Healing Epoxy Vitrimers with Dynamic Imine and Disulfide Bonds Derived from Vanillin, Cystamine, and Dimer Diamine. Molecules 2024, 29, 4839. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29204839

Abe I, Shibata M. Bio-Based Self-Healing Epoxy Vitrimers with Dynamic Imine and Disulfide Bonds Derived from Vanillin, Cystamine, and Dimer Diamine. Molecules. 2024; 29(20):4839. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29204839

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbe, Itsuki, and Mitsuhiro Shibata. 2024. "Bio-Based Self-Healing Epoxy Vitrimers with Dynamic Imine and Disulfide Bonds Derived from Vanillin, Cystamine, and Dimer Diamine" Molecules 29, no. 20: 4839. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29204839

APA StyleAbe, I., & Shibata, M. (2024). Bio-Based Self-Healing Epoxy Vitrimers with Dynamic Imine and Disulfide Bonds Derived from Vanillin, Cystamine, and Dimer Diamine. Molecules, 29(20), 4839. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29204839