Research on Hydrogen Production from Ammonia Decomposition by Pulsed Plasma Catalysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Plasma Reaction Kinetics Modeling

2.1. Nanosecond-Pulsed Plasma Model

2.1.1. Chemical Composition

2.1.2. Reaction Mechanism

3. Results and Discussion

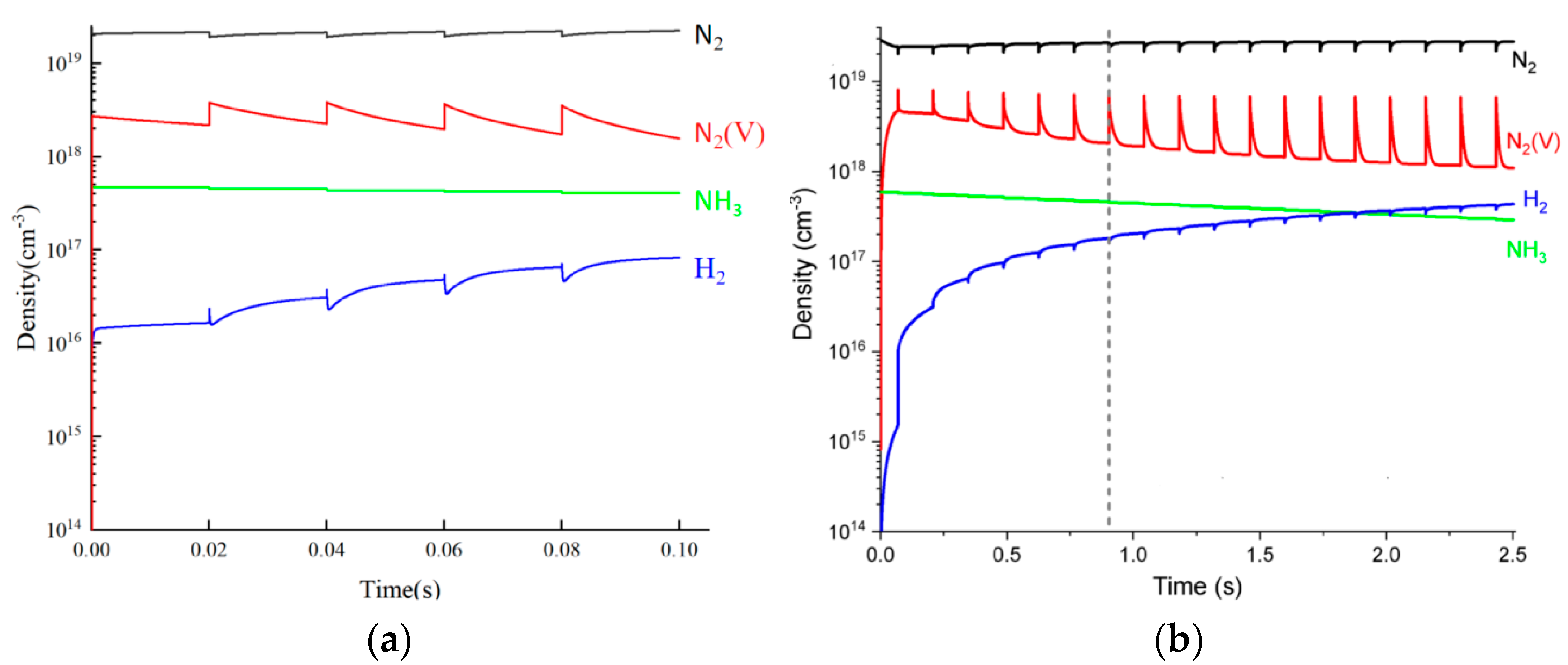

3.1. Model Verification

3.2. Analysis of Influencing Factors

3.2.1. Reaction Temperature

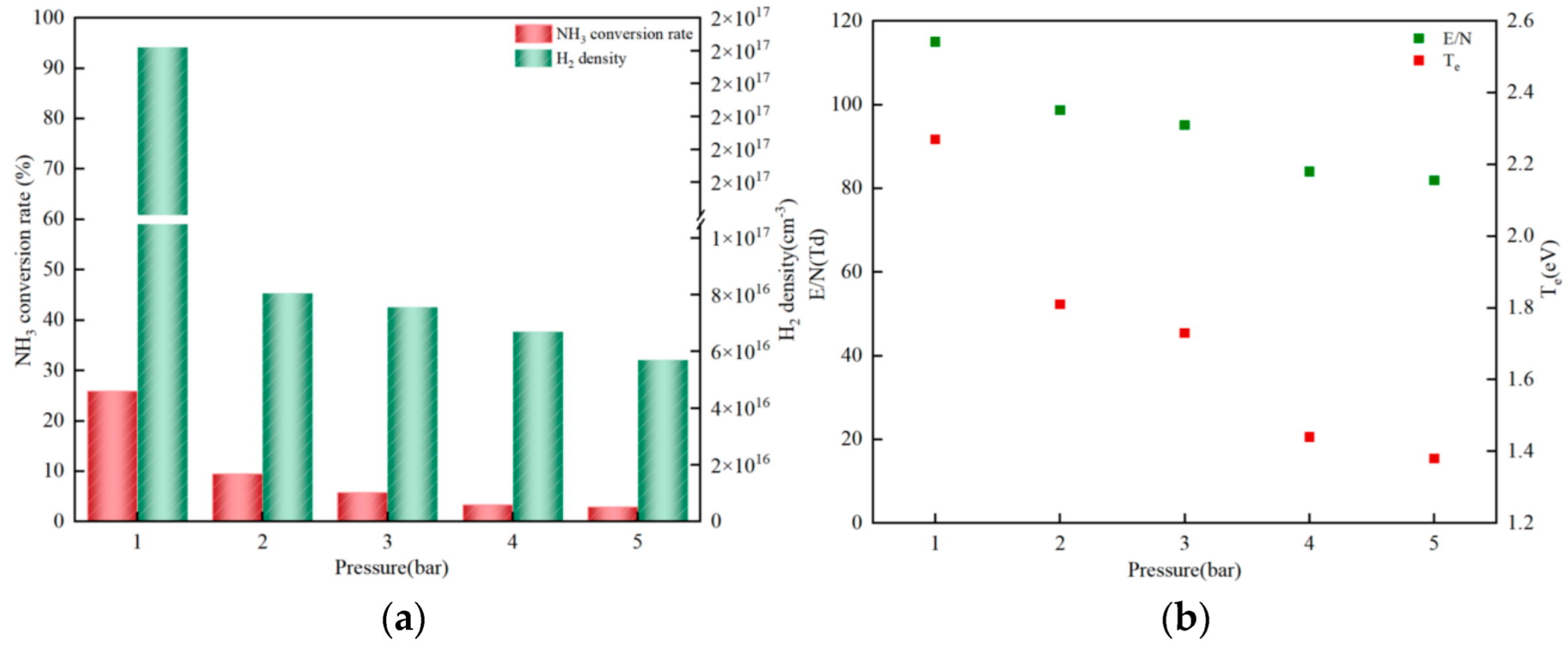

3.2.2. Reaction Pressure

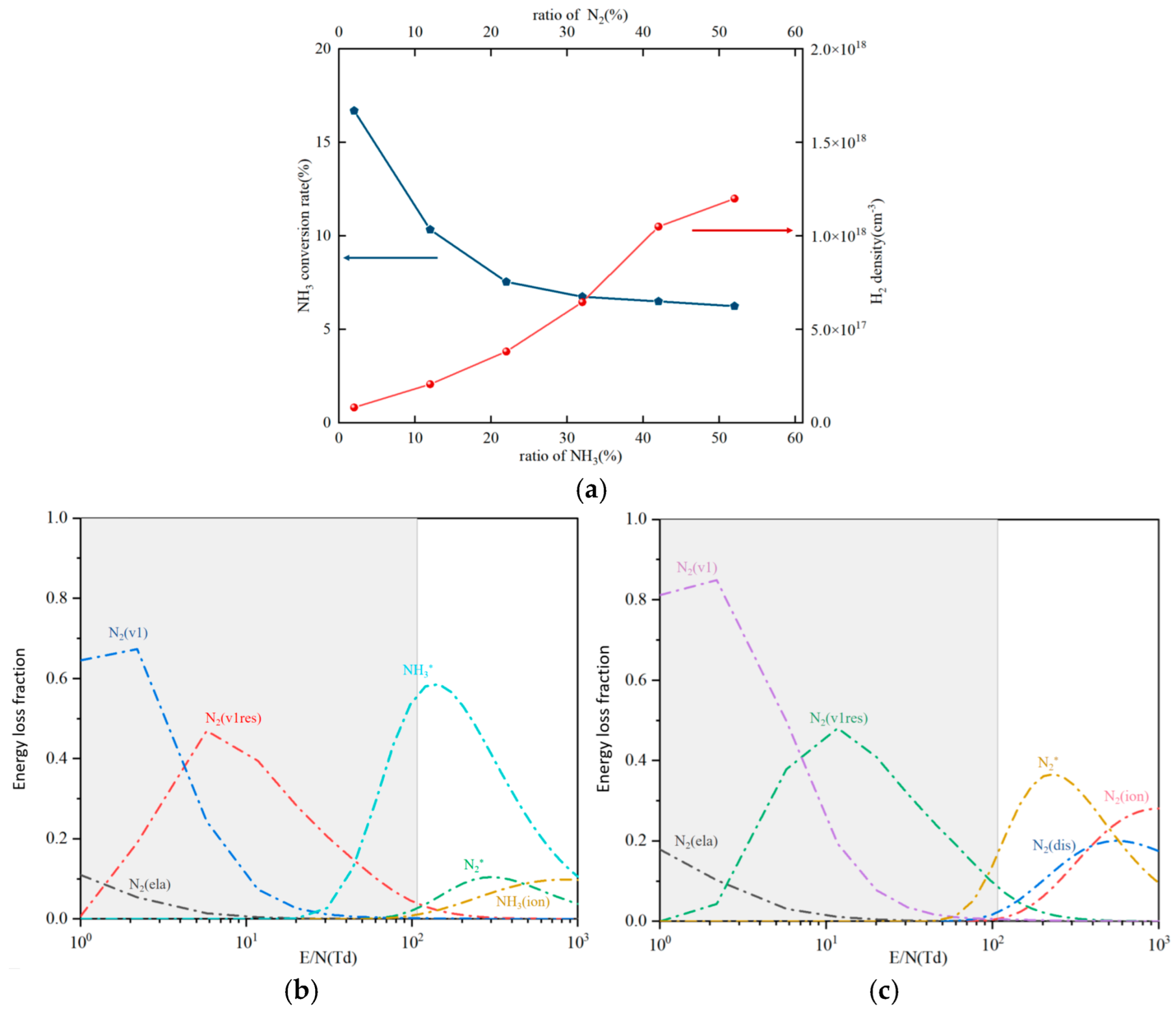

3.2.3. Different Ratios of Feed Gases

3.3. Reaction Mechanism Analysis

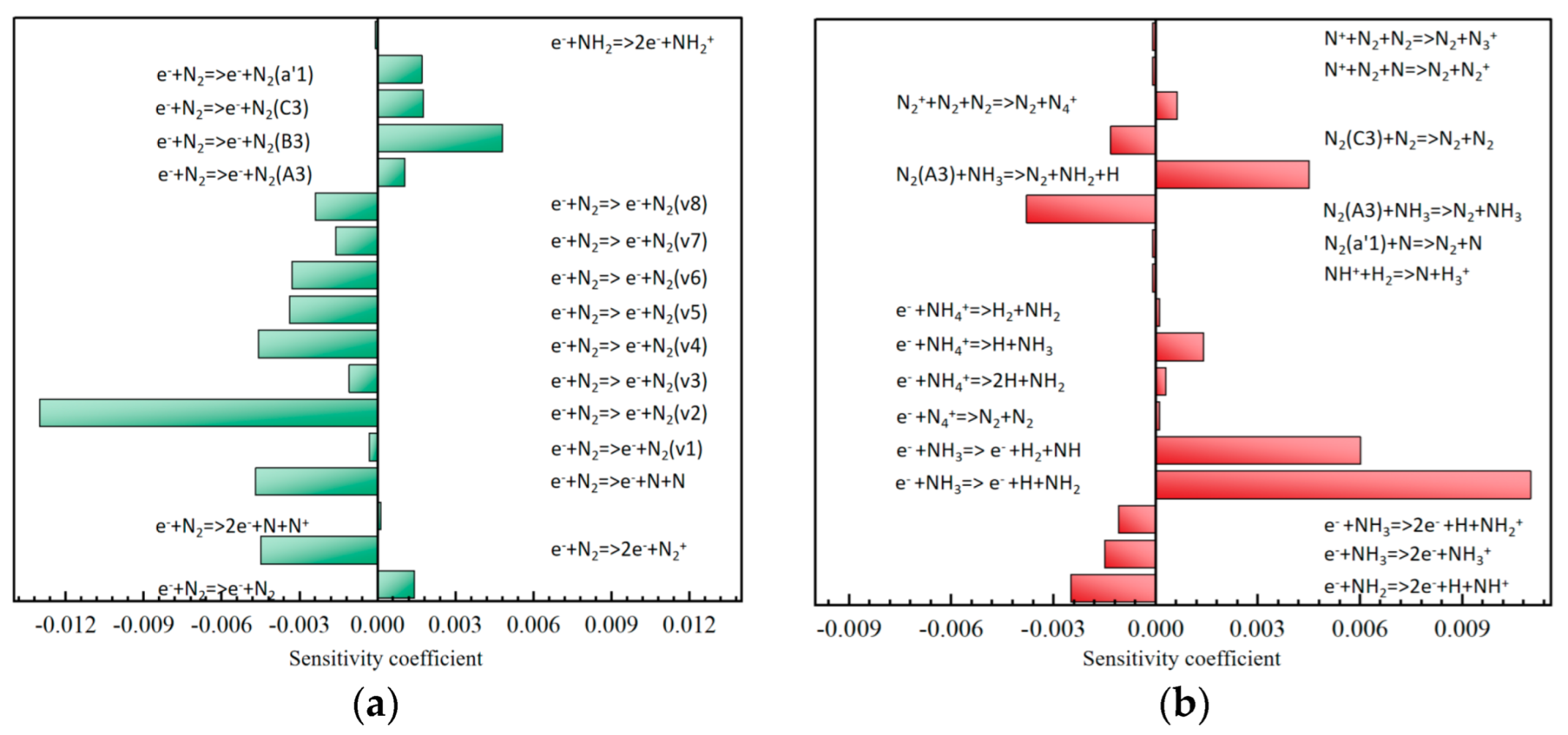

3.3.1. Sensitivity Analysis

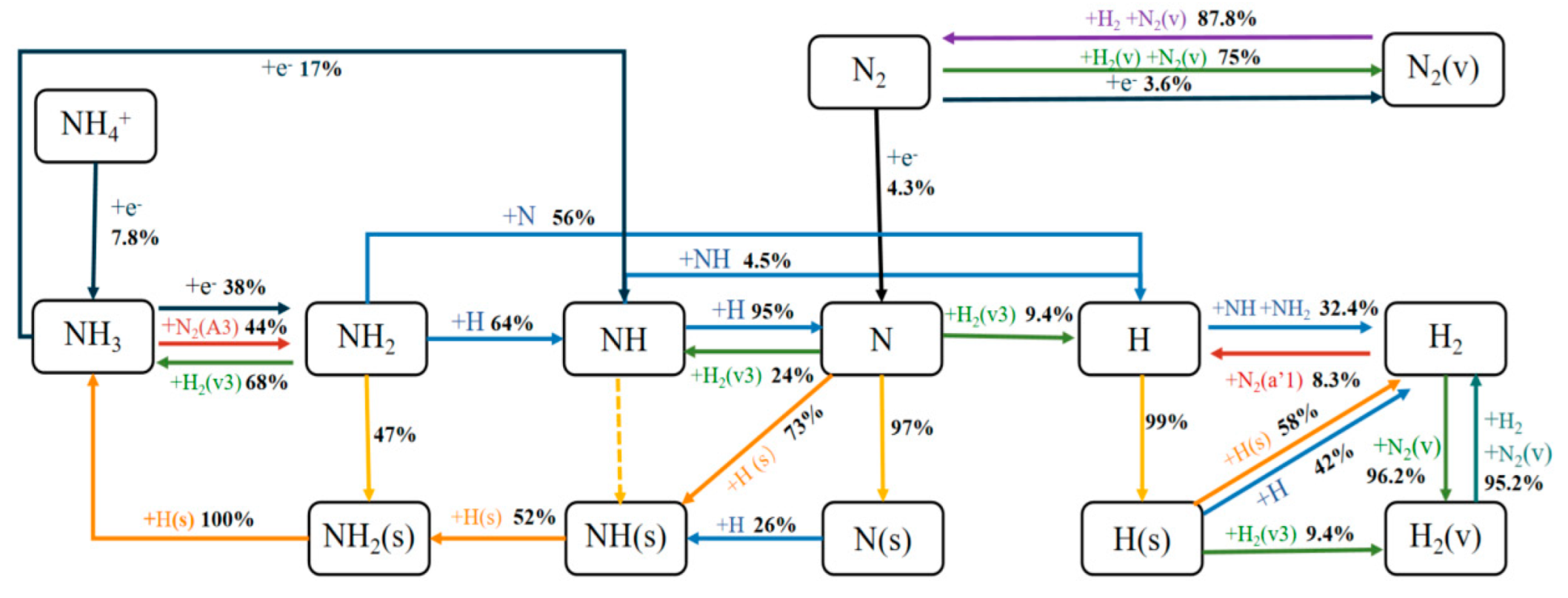

3.3.2. Reaction Path Analysis

4. Calculation Method

4.1. Calculation of the Particle Number Density and Reduced Electric Field Strength

4.1.1. Calculation of Particle Number Density

4.1.2. Calculation of the Reduced Electric Field Strength

4.2. Calculation of Ammonia Conversion Rate and Sensitivity Coefficient

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Energy saving, carbon reduction and green development of inland waterway transportation system should do so. China Water Transport, 17 February 2022.

- Shaping the New Advantages of “Thoroughfare of Nine States”-Survey on Enhancing the Open Hub Function of Hubei Province. Economic Daily, 10 April 2024.

- Hubei Province 2023 National Economic and Social Development Statistics Bulletin. Hubei Province Statistics Bureau, 27 March 2024.

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, X.H.; Liu, L. Theoretical investigation of the combustion performance of ammonia/hydrogen mixtures on a marine diesel engine. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 14805–14812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Sun, Y.; Gong, Z.; Meng, S.; Wei, X.; Tang, B.; Wan, J. Study on the impact mechanism of ammonia energy fraction on in-cylinder combustion and pollutant generation under wide operation conditions of medium-speed diesel engines. Fuel 2024, 360, 130617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.S. Challenges and Path of China’s Shipping Decarbonization. China Marit. Saf. 2023, 6, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitriou, P.; Javaid, R. A review of ammonia as a compression ignition engine fuel. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 7098–7118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boretti, A. Novel dual fuel diesel-ammonia combustion system in advanced TDI engines. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 7071–7076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.C.; Kao, Y.L.; Yeh, G.T.; Rei, M.H. An onboard hydrogen generator for hydrogen enhanced combustion with internal combustion engine. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 21334–21342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lhuillier, C.; Brequigny, P.; Contino, F.; Rousselle, C. Combustion characteristics of ammonia in a modern spark-ignition engine. SAE Tech. Pap. 2019, 237, 2019–2024. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.L.; Liu, Z.T. In-cylinder thermochemical fuel reforming for high efficiency in ammonia spark-ignited engines through hydrogen generation from fuel-rich operations. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 54, 837–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Lu, C.; Ye, S.; Hua, Z.; Gu, C. Optimization on volume ratio of three-stage cascade storage system in hydrogen refueling stations. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 13430–13441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, S.J.; Wang, Z.; Ma, X.; Xu, H.M.; Xin, H.E.; Wang, J. Low carbon and zero carbon technology paths and key technologies of ICEs under the background of carbon neutrality. Automot. Saf. Energy 2021, 12, 417–439. [Google Scholar]

- Sami, A.; Mehrpooya, M.; Noorpoor, A. Investigation of an integrated thermochemical hydrogen production and high temperature solar thermochemical energy storage and CO2 capture process. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 214, 1359–4311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanda, V.K.; Fend, T.; Laaber, D. Experimental investigation of the applicability of a 250kW ceria receiver/reactor for solar thermochemical hydrogen generation. Renew. Energy 2022, 198, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pein, M.; Neumann, N.C.; Venstrom, L.J.; Vieten, J.; Roeb, M.; Sattler, C. Two-step thermochemical electrolysis: An approach for green hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 24909–24918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.H.; Zheng, S.S.; Yao, Y.D.; Chen, R.; Wang, Z. Research progress on electrocatalytic decomposition of ammonia for hydrogen production. CIESC J. 2022, 73, 1008–1021. [Google Scholar]

- Yuzawa, H.; Mori, T.; Itoh, H.; Yoshida, H. Reaction mechanism of ammonia decomposition to nitrogen and hydrogen over metal loaded titanium oxide photocatalyst. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 4126–4136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. The Research of Ammonia Decomposition via Plasma-Catalysis. Ph.D. Thesis, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ban, J.Y.; Kim, H.I.; Choung, S.J.; Jeong, H.; Kang, M. NH3 removal using the dielectric barrier discharge plasma-V-TiO2 photocatalytic hybrid system. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2008, 25, 780–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouwenhorst, K.H.R.; Lefferts, L. Feasibility study of plasma-catalytic ammonia synthesis for energy storage applications. Catalysts 2020, 10, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaerts, A.; Tu, X.; Whitehead, J.C.; Centi, G.; Lefferts, L.; Guaitella, O.; Azzolina-Jury, F.; Kim, H.H.; Murphy, A.B.; Schneider, W.F.; et al. The 2020 plasma catalysis roadmap. Phys. D-Appl. Phys. 2020, 53, 443001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaerts, A.; Neyts, E.C. Plasma technology: An emerging technology for energy storage. ACS Energy Lett. 2018, 3, 1013–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.W. Performance Analysis of Organic Rankine Cycle for Low Temperature Waste Heat Recovery on Ship. Ph.D. Thesis, Dalian Maritime University, Dalian, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Analysis of the development status and technical difficulties of ammonia-hydrogen-powered offshore vessels. China Hydrogen Alliance, 5 December 2023.

- Huang, G.C. Design and Optimization of Low Grade Waste Heat Utilization Scheme for Marine Diesel Engine Based on Organic Rankine Cycle. Ph.D. Thesis, Guangxi University, Nanning, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Wang, H.; Duan, B.; Yang, C.; Hu, D.; Wang, Y. Effect of ammonia/hydrogen mixture ratio on engine combustion and emission performance at different inlet temperatures. Energy 2023, 272, 127110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, C.J.; Li, N.; Du, J.; Zong, L.J.; Chen, T.; Pan, J. Numerical modeling and mechanism of gas phase-surface coupling for plasma catalytic ammonia synthesis. High Volt. Eng. 2022, 48, 1142–1156. [Google Scholar]

- Pancheshnyi, S.; Eismann, B.; Hagelaar, G.; Pitchford, L. ZDPlasKin: A new tool for plasma chemical simulations. Bull. Am. Phys. Soc. 2008, 53, 2–15. [Google Scholar]

- van’t Veer, K.; Engelmann, Y.; Reniers, F.; Bogaerts, A. Plasma-Catalytic ammonia synthesis in a DBD plasma: Role of micro-discharges and their afterglows. J. Phys. Chem. C 2020, 124, 22871–22883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.T.; Chen, Q.; Zhao, X.T.; Lin, H.; Qin, W. Kinetic investigation of plasma catalytic synthesis of ammonia: Insights into the role of excited states and plasma-enhanced surface chemistry. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2022, 31, 094009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagelaar, G.J.M.; Pitchford, L.C. Solving the Boltzmann equation to obtain electron transport coefficientents and rate coefficientents for fluid models. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2005, 14, 722–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capitelli, M.; Ferreira, C.M.; Gordiets, B.F.; Osipov, A.I. Plasma Kinetics in Atmospheric Gases; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 101–140. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, J.; Pancheshnyi, S.; Tam, E.; Lowke, J.J.; Prawer, S.; Murphy, A.B. Kinetic modelling of NH3 production in N2-H2 non-equilibrium atmospheric-pressure plasma catalysis. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2017, 50, 154005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van’t Veer, K.; Reniers, F.; Bogaerts, A. Zero-dimensional modelling of unpacked and packed bed dielectric barrier discharges: The role of vibrational kinetics in ammonia synthesis. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2020, 29, 45020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, J.A.; van’t Veer, K.; Christensen, J.M.; Østberg, M.; Bogaerts, A.; Jensen, A.D. Ammonia decomposition in a dielectric barrier discharge plasma: Insights from experiments and kinetic modeling. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2023, 271, 118550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, S.; Snoeckx, R.; Cha, M.S. Kinetic study for plasma assisted cracking of NH3: Approaches and challenges. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 127, 1271–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snoeckx, R.; Tennyson, J.; Cha, M.S. Theoretical cross sections for electron collisions relevant for ammonia discharges part 1: NH3, NH2, and NH. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2023, 32, 115020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N. Numerical Simulations and Deep Neural Network Solutions of Plasma Catalytic Ammonia Syntheses by Nanosecond Pulsed Discharge. Ph.D. Thesis, Shandong Normal University, Jinan, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, X.; Su, H.Y.; Sun, X.; Pang, W.; Hao, X.; Xu, Y.; Sun, K. Interplay between surface structure, reaction condition and mechanism for ammonia decomposition on Ru catalyst. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 649, 159175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadiri, S.; Shu, B.; Goldsmith, C.F.; Fernandes, R. Development of comprehensive kinetic models of ammonia/methanol ignition using Reaction Mechanism Generator (RMG). Combust Flame 2023, 251, 112710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.B.; Zhou, M.; Hu, E.J.; Zhao, Y.; Yin, G.; Huang, Z. Hydrogen generation by dielectric barrier discharge plasma assisted ammonia decomposition. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 306, 118271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markosyan, A.H.; Luque, A.; Gordillo-Vázquez, F.J.; Ebert, U. PumpKin: A tool to find principal pathways in plasma chemical models. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2014, 185, 2697–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, E.; Delikonstantis, E.; Scapinello, M.; Smith, G.; Stefanidis, G.D.; Bogaerts, A. Methane coupling in nanosecond pulsed plasmas: Correlation between temperature and pressure and effects on product selectivity. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 462, 142227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Particle Species | Chemical Formula |

|---|---|

| Ground-state molecule | N2, H2, NH3 |

| Atom/radical | N, H, NH, NH2, NH3, N2H, N2H2, N2H3, N2H4 |

| Excited-state molecule | N2 (v1), N2 (v2), N2 (v3), N2 (v4), N2 (v5), N2 (v6), N2 (v7), N2 (v8), H2 (v1), H2 (v2), H2 (v3), N2 (a’1), N2 (A3), N2 (B3), N2 (C3), N2 (2D), N2 (2P) |

| Ion | , , , , , , , , , , , e−, H− |

| Surface-adsorbed particle | N (s), H (s), NH (s), NH2 (s), NH3 (s) |

| Particle Reaction Types | Source of Collision Cross-Section Data and Reaction Rate Coefficient a |

|---|---|

| The dissociation reaction of NH3 colliding with electrons | Ref. [37] |

| The elastic collision reaction of NH3 with electrons | Morgan database |

| The ionization reaction of NH3 colliding with electrons | Morgan database |

| The vibrational reaction of N2 colliding with electrons | Phelps database |

| The electron excitation reaction of N2 colliding with electrons | Phelps database |

| The elastic collision reaction of N2 colliding with electrons | Phelps database |

| The ionization reaction of N2 colliding with electrons | Itikawa database |

| The dissociation reaction of N2 collision with electrons | Ref. [37] |

| The elastic collision reaction of H2 colliding with electrons | Itikawa database |

| The vibrational reaction of H2 colliding with electrons | Phelps database |

| The electron excitation reaction of H2 colliding with electrons | Itikawa database |

| The dissociation reaction of H2 colliding with electrons | Itikawa database |

| The ionization reaction of H2 colliding with electrons | Itikawa database |

| The electron excitation reaction of N colliding with electrons | Ref. [37] |

| The elastic collision reaction of N colliding with electrons | Ref. [37] |

| The ionization reaction of N colliding with electrons | Ref. [37] |

| The elastic collision reaction of H colliding with electrons | Ref. [37] |

| The ionization reaction of H colliding with electrons | Ref. [37] |

| Reaction Number | Reaction Equation |

|---|---|

| R-156 | N + NH2 => H2 + N2 |

| R-46 | e + NH3 => e + NH + H2 |

| R-177 | NH + NH => H2 + N2 |

| R-41 | e + NH2 => e + N+H2 |

| R-488 | H(s) + H(s) => H2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

He, Y.; Zhu, N.; Cai, Y. Research on Hydrogen Production from Ammonia Decomposition by Pulsed Plasma Catalysis. Molecules 2025, 30, 1054. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30051054

He Y, Zhu N, Cai Y. Research on Hydrogen Production from Ammonia Decomposition by Pulsed Plasma Catalysis. Molecules. 2025; 30(5):1054. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30051054

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Yuze, Neng Zhu, and Yunkai Cai. 2025. "Research on Hydrogen Production from Ammonia Decomposition by Pulsed Plasma Catalysis" Molecules 30, no. 5: 1054. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30051054

APA StyleHe, Y., Zhu, N., & Cai, Y. (2025). Research on Hydrogen Production from Ammonia Decomposition by Pulsed Plasma Catalysis. Molecules, 30(5), 1054. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30051054