Alteration of Skin Properties with Autologous Dermal Fibroblasts

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Autologous Fibroblasts Promote Wound Healing

3. Autologous Fibroblasts for Cellular Therapies

3.1. Preclinical Studies and Approach

3.2. Fibroblast Expansion and Production

3.3. Mode of Administration and Cell Delivery

4. Therapeutic Indications

4.1. Cutaneous Burns

4.2. Cosmetic Indications

4.3. Orthopedic Indications

4.4. Wound Repair

5. Regional and Microanatomic Specificity of Fibroblast Populations

5.1. Regional Identity

5.1.1. Induction of Acral Skin

5.2. Microanatomic Specificity

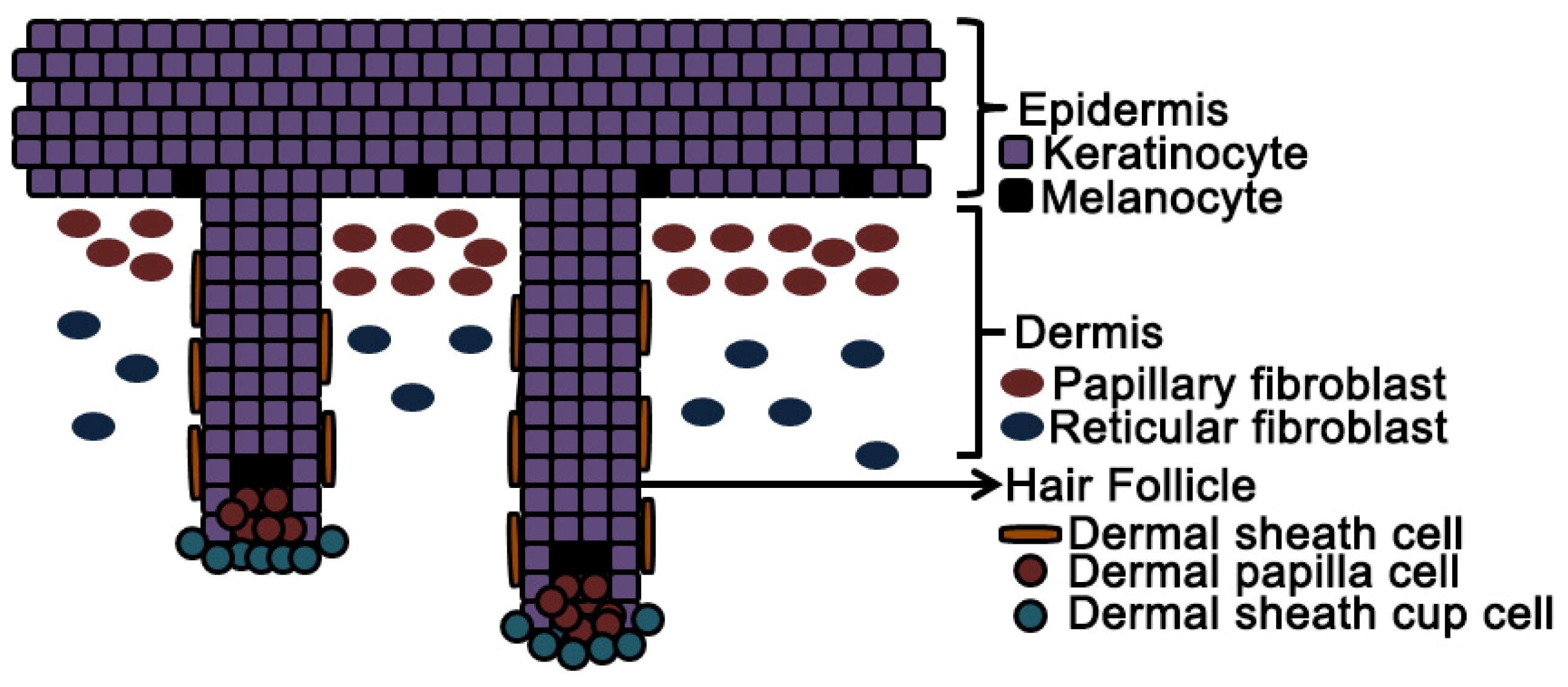

5.2.1. Papillary and Reticular Dermal Fibroblasts

5.2.2. Dermal Papilla and Dermal Sheath Cells

5.2.3. Induction of Hair Follicles

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DP | dermal papilla |

| DS | dermal sheath |

| FGF | fibroblast growth factor 2 |

| GMP | Good Manufacturing Process |

| HGF | hepatocyte growth factor |

| ILF | integrin-linked kinase |

| MMP | Matrix metalloproteinase |

| VEGF | vascular endothelial growth factor |

- Author ContributionsR.L.T., T.N.D. and J.M. conceived the review, designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. R.L.T. performed the experiments. R.L.T., T.N.D. and J.M. analyzed the data.

References

- Weiss, R.A. Autologous cell therapy: Will it replace dermal fillers? Fac. Plast. Surg. Clin. N. Am 2013, 21, 299–304. [Google Scholar]

- McHeik, J.N.; Barrault, C.; Pedretti, N.; Garnier, J.; Juchaux, F.; Levard, G.; Morel, F.; Lecron, J.C.; Bernard, F.X. Foreskin-isolated keratinocytes provide successful extemporaneous autologous paediatric skin grafts. J. Tissue Eng. Regener. Med 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asai, J.; Takenaka, H.; Ii, M.; Asahi, M.; Kishimoto, S.; Katoh, N.; Losordo, D.W. Topical application of ex vivo expanded endothelial progenitor cells promotes vascularisation and wound healing in diabetic mice. Int. Wound J 2013, 10, 527–533. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Zhao, R.C.; Tredget, E.E. Concise review: Bone marrow-derived stem/progenitor cells in cutaneous repair and regeneration. Stem Cells 2010, 28, 905–915. [Google Scholar]

- Ohyama, M.; Okano, H. Promise of human induced pluripotent stem cells in skin regeneration and investigation. J. Investig. Dermatol 2014, 134, 605–609. [Google Scholar]

- Lohmeyer, J.A.; Liu, F.; Kruger, S.; Lindenmaier, W.; Siemers, F.; Machens, H.G. Use of gene-modified keratinocytes and fibroblasts to enhance regeneration in a full skin defect. Langenbeck’s Arch. Surg. Dtsch. Ges. Chir 2011, 396, 543–550. [Google Scholar]

- Hata, K. Current issues regarding skin substitutes using living cells as industrial materials. J. Artif. Organs 2007, 10, 129–132. [Google Scholar]

- Greaves, N.S.; Iqbal, S.A.; Baguneid, M.; Bayat, A. The role of skin substitutes in the management of chronic cutaneous wounds. Wound Repair Regen 2013, 21, 194–210. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano, E.; Cochis, A.; Varoni, E.; Rimondini, L.; Azzimonti, B. Tissue-engineered skin substitutes: An overview. J. Artif. Organs 2013, 16, 397–403. [Google Scholar]

- Greaves, N.S.; Ashcroft, K.J.; Baguneid, M.; Bayat, A. Current understanding of molecular and cellular mechanisms in fibroplasia and angiogenesis during acute wound healing. J. Dermatol. Sci 2013, 72, 206–217. [Google Scholar]

- Vedrenne, N.; Coulomb, B.; Danigo, A.; Bonte, F.; Desmouliere, A. The complex dialogue between (myo)fibroblasts and the extracellular matrix during skin repair processes and ageing. Pathologie-Biologie 2012, 60, 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Glim, J.E.; Niessen, F.B.; Everts, V.; van Egmond, M.; Beelen, R.H. Platelet derived growth factor-CC secreted by M2 macrophages induces alpha-smooth muscle actin expression by dermal and gingival fibroblasts. Immunobiology 2013, 218, 924–929. [Google Scholar]

- McGee, H.M.; Schmidt, B.A.; Booth, C.J.; Yancopoulos, G.D.; Valenzuela, D.M.; Murphy, A.J.; Stevens, S.; Flavell, R.A.; Horsley, V. IL-22 promotes fibroblast-mediated wound repair in the skin. J. Investig. Dermatol 2013, 133, 1321–1329. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, H.X.; Lin, C.; Lin, B.B.; Wang, Z.G.; Zhang, H.Y.; Wu, F.Z.; Cheng, Y.; Xiang, L.J.; Guo, D.J.; Luo, X.; et al. The anti-scar effects of basic fibroblast growth factor on the wound repair in vitro and in vivo. PLoS One 2013, 8, e59966. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, J.; Jun, H.; Chung, H.; Yoon, C.; Kim, T.; Kwon, M.; Lee, S.; Jung, S.; Kim, M.; Park, J.H. Comparison of EGF with VEGF non-viral gene therapy for cutaneous wound healing of streptozotocin diabetic mice. Diabetes Metab. J 2011, 35, 226–235. [Google Scholar]

- Loyd, C.M.; Diaconu, D.; Fu, W.; Adams, G.N.; Brandt, E.; Knutsen, D.A.; Wolfram, J.A.; McCormick, T.S.; Ward, N.L. Transgenic overexpression of keratinocyte-specific VEGF and Ang1 in combination promotes wound healing under nondiabetic but not diabetic conditions. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol 2012, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kellouche, S.; Mourah, S.; Bonnefoy, A.; Schoevaert, D.; Podgorniak, M.P.; Calvo, F.; Hoylaerts, M.F.; Legrand, C.; Dosquet, C. Platelets, thrombospondin-1 and human dermal fibroblasts cooperate for stimulation of endothelial cell tubulogenesis through VEGF and PAI-1 regulation. Exp. Cell Res 2007, 313, 486–499. [Google Scholar]

- Conway, K.; Price, P.; Harding, K.G.; Jiang, W.G. The molecular and clinical impact of hepatocyte growth factor, its receptor, activators, and inhibitors in wound healing. Wound Repair Regen 2006, 14, 2–10. [Google Scholar]

- Schnickmann, S.; Camacho-Trullio, D.; Bissinger, M.; Eils, R.; Angel, P.; Schirmacher, P.; Szabowski, A.; Breuhahn, K. AP-1-controlled hepatocyte growth factor activation promotes keratinocyte migration via CEACAM1 and urokinase plasminogen activator/urokinase plasminogen receptor. J. Investig. Dermatol 2009, 129, 1140–1148. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano, I.; Diez-Marques, M.L.; Rodriguez-Puyol, M.; Herrero-Fresneda, I.; Raimundo Garcia del, M.; Dedhar, S.; Ruiz-Torres, M.P.; Rodriguez-Puyol, D. Integrin-linked kinase (ILK) modulates wound healing through regulation of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF). Exp. Cell Res 2012, 318, 2470–2481. [Google Scholar]

- Finnson, K.W.; McLean, S.; di Guglielmo, G.M.; Philip, A. Dynamics of transforming growth factor beta signaling in wound healing and scarring. Adv. Wound Care 2013, 2, 195–214. [Google Scholar]

- Rolfe, K.J.; Irvine, L.M.; Grobbelaar, A.O.; Linge, C. Differential gene expression in response to transforming growth factor-β1 by fetal and postnatal dermal fibroblasts. Wound Repair Regen 2007, 15, 897–906. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, S.E.; Parks, W.C. Metalloproteinases and their inhibitors: Regulators of wound healing. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol 2008, 40, 1334–1347. [Google Scholar]

- Olaso, E.; Lin, H.C.; Wang, L.H.; Friedman, S.L. Impaired dermal wound healing in discoidin domain receptor 2-deficient mice associated with defective extracellular matrix remodeling. Fibrogen. Tissue Repair 2011, 4, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Gawronska-Kozak, B. Scarless skin wound healing in FOXN1 deficient (nude) mice is associated with distinctive matrix metalloproteinase expression. Matrix Biol. J. Int. Soc. Matrix Biol 2011, 30, 290–300. [Google Scholar]

- Bouissou, H.; Pieraggi, M.; Julian, M.; Uhart, D.; Kokolo, J. Fibroblasts in dermal tissue repair. Electron microscopic and immunohistochemical study. Int. J. Dermatol 1988, 27, 564–570. [Google Scholar]

- Purdue, G.F.; Hunt, J.L.; Still, J.M., Jr.; Law, E.J.; Herndon, D.N.; Goldfarb, I.W.; Schiller, W.R.; Hansbrough, J.F.; Hickerson, W.L.; Himel, H.N.; et al. A multicenter clinical trial of a biosynthetic skin replacement, Dermagraft-TC, compared with cryopreserved human cadaver skin for temporary coverage of excised burn wounds. J. Burn Care Rehabil 1997, 18, 52–57. [Google Scholar]

- Junker, J.P.; Sommar, P.; Skog, M.; Johnson, H.; Kratz, G. Adipogenic, chondrogenic and osteogenic differentiation of clonally derived human dermal fibroblasts. Cells Tissues Organs 2010, 191, 105–118. [Google Scholar]

- Driskell, R.R.; Lichtenberger, B.M.; Hoste, E.; Kretzschmar, K.; Simons, B.D.; Charalambous, M.; Ferron, S.R.; Herault, Y.; Pavlovic, G.; Ferguson-Smith, A.C.; et al. Distinct fibroblast lineages determine dermal architecture in skin development and repair. Nature 2013, 504, 277–281. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, G.; Sebastian, J.; Lacombe, U.; Toft, K.; Lask, G.; Revazova, E. Safety of injectable autologous human fibroblasts. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med 2000, 130, 786–789. [Google Scholar]

- Lamme, E.N.; van Leeuwen, R.T.; Brandsma, K.; van Marle, J.; Middelkoop, E. Higher numbers of autologous fibroblasts in an artificial dermal substitute improve tissue regeneration and modulate scar tissue formation. J. Pathol 2000, 190, 595–603. [Google Scholar]

- Svensjo, T.; Yao, F.; Pomahac, B.; Winkler, T.; Eriksson, E. Cultured autologous fibroblasts augment epidermal repair. Transplantation 2002, 73, 1033–1041. [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto, N.; Saso, Y.; Tomihata, K.; Taira, T.; Takahashi, Y.; Ohta, M.; Suzuki, S. Viability and function of autologous and allogeneic fibroblasts seeded in dermal substitutes after implantation. J. Surg. Res 2005, 125, 56–67. [Google Scholar]

- Lamme, E.N.; van Leeuwen, R.T.; Mekkes, J.R.; Middelkoop, E. Allogeneic fibroblasts in dermal substitutes induce inflammation and scar formation. Wound Repair Regen 2002, 10, 152–160. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, L.; Mao, J.J. Tissue-engineered rabbit cranial suture from autologous fibroblasts and BMP2. J. Dent. Res 2004, 83, 751–756. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Chen, B.; Deng, D.; Xu, F.; Cui, L.; Cao, Y. Repair of tendon defect with dermal fibroblast engineered tendon in a porcine model. Tissue Eng 2006, 12, 775–788. [Google Scholar]

- Kanzaki, M.; Yamato, M.; Yang, J.; Sekine, H.; Takagi, R.; Isaka, T.; Okano, T.; Onuki, T. Functional closure of visceral pleural defects by autologous tissue engineered cell sheets. Eur. J. Cardio-Thorac. Surg 2008, 34, 864–869. [Google Scholar]

- Egan, J.J.; Saltis, J.; Wek, S.A.; Simpson, I.A.; Londos, C. Insulin, oxytocin, and vasopressin stimulate protein kinase C activity in adipocyte plasma membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1990, 87, 1052–1056. [Google Scholar]

- Van Zuijlen, P.P.; van Leeuwen, R.T.; Middelkoop, E. Practical sources for autologous fibroblasts to prepare a bioengineered dermal equivalent. Burns 1998, 24, 687. [Google Scholar]

- Rinn, J.L.; Bondre, C.; Gladstone, H.B.; Brown, P.O.; Chang, H.Y. Anatomic demarcation by positional variation in fibroblast gene expression programs. PLoS Genet 2006, 2, e119. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, J.A.; Headon, D.J. Regionalisation of the skin. Sem. Cell Dev. Biol 2014, 25–26, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.Y.; Hafner, J.; Dragieva, G.; Burg, G. High yields of autologous living dermal equivalents using porcine gelatin microbeads as microcarriers for autologous fibroblasts. Cell Transpl 2006, 15, 445–451. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S.R.; Munavalli, G.; Weiss, R.; Maslowski, J.M.; Hennegan, K.P.; Novak, J.M. A multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of autologous fibroblast therapy for the treatment of nasolabial fold wrinkles. Dermatol. Surg 2012, 38, 1234–1243. [Google Scholar]

- Marcelo, D.; Beatriz, P.M.; Jussara, R.; Fabiana, B. Tissue therapy with autologous dermal and epidermal culture cells for diabetic foot ulcers. Cell Tissue Bank 2012, 13, 241–249. [Google Scholar]

- Boyce, S.T.; Kagan, R.J.; Greenhalgh, D.G.; Warner, P.; Yakuboff, K.P.; Palmieri, T.; Warden, G.D. Cultured skin substitutes reduce requirements for harvesting of skin autograft for closure of excised, full-thickness burns. J. Trauma 2006, 60, 821–829. [Google Scholar]

- Scuderi, N.; Onesti, M.G.; Bistoni, G.; Ceccarelli, S.; Rotolo, S.; Angeloni, A.; Marchese, C. The clinical application of autologous bioengineered skin based on a hyaluronic acid scaffold. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 1620–1629. [Google Scholar]

- Gilleard, O.; Segaren, N.; Healy, C. Experience of recell in skin cancer reconstruction. Arch. Plast. Surg 2013, 40, 627–629. [Google Scholar]

- Vogt, P.M.; Kolokythas, P.; Niederbichler, A.; Knobloch, K.; Reimers, K.; Choi, C.Y. Innovative wound therapy and skin substitutes for burns. Chirurg 2007, 78, 335–342. [Google Scholar]

- Blais, M.; Parenteau-Bareil, R.; Cadau, S.; Berthod, F. Concise review: Tissue-engineered skin and nerve regeneration in burn treatment. Stem Cells Transl. Med 2013, 2, 545–551. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, J.W.; MacMillan, B.G.; Law, E.; Kittur, D.S. Treatment of severe burns with widely meshed skin autograft and meshed skin allograft overlay. J. Trauma 1981, 21, 433–438. [Google Scholar]

- Killat, J.; Reimers, K.; Choi, C.Y.; Jahn, S.; Vogt, P.M.; Radtke, C. Cultivation of keratinocytes and fibroblasts in a three-dimensional bovine collagen-elastin matrix (Matriderm(R)) and application for full thickness wound coverage in vivo. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 14460–14474. [Google Scholar]

- Caruso, D.M.; Schuh, W.H.; Al-Kasspooles, M.F.; Chen, M.C.; Schiller, W.R. Cultured composite autografts as coverage for an extensive body surface area burn: Case report and review of the technology. Burns 1999, 25, 771–779. [Google Scholar]

- Wisser, D.; Steffes, J. Skin replacement with a collagen based dermal substitute, autologous keratinocytes and fibroblasts in burn trauma. Burns 2003, 29, 375–380. [Google Scholar]

- Llames, S.G.; del Rio, M.; Larcher, F.; Garcia, E.; Garcia, M.; Escamez, M.J.; Jorcano, J.L.; Holguin, P.; Meana, A. Human plasma as a dermal scaffold for the generation of a completely autologous bioengineered skin. Transplantation 2004, 77, 350–355. [Google Scholar]

- Llames, S.; Garcia, E.; Garcia, V.; del Rio, M.; Larcher, F.; Jorcano, J.L.; Lopez, E.; Holguin, P.; Miralles, F.; Otero, J.; et al. Clinical results of an autologous engineered skin. Cell Tissue Bank 2006, 7, 47–53. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, I.S.; Lee, A.R.; Lee, H.; Park, H.J.; Chung, S.Y.; Wallraven, C.; Bulthoff, I.; Chae, Y. Psychological distress and attentional bias toward acne lesions in patients with acne. Psychol. Health Med 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, C.; Williamson, H.; Rumsey, N. The romantic experiences of adolescents with a visible difference: Exploring concerns, protective factors and support needs. J. Health Psychol 2012, 17, 1053–1064. [Google Scholar]

- Funt, D.; Pavicic, T. Dermal fillers in aesthetics: An overview of adverse events and treatment approaches. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol 2013, 6, 295–316. [Google Scholar]

- West, T.B.; Alster, T.S. Autologous human collagen and dermal fibroblasts for soft tissue augmentation. Dermatol. Surg 1998, 24, 510–512. [Google Scholar]

- Boss, W.K., Jr.; Usal, H.; Fodor, P.B.; Chernoff, G. Autologous cultured fibroblasts: A protein repair system. Ann. Plast. Surg 2000, 44, 536–542. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, D.; Keller, G.S.; Lacombe, V.; Fodor, P.B.; Rawnsley, J.; Lask, G.P. Autologous fibroblasts for treatment of facial rhytids and dermal depressions. A pilot study. Arch. Fac. Plast. Surg 1999, 1, 165–170. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, R.A.; Weiss, M.A.; Beasley, K.L.; Munavalli, G. Autologous cultured fibroblast injection for facial contour deformities: A prospective, placebo-controlled, Phase III clinical trial. Dermatol. Surg 2007, 33, 263–268. [Google Scholar]

- Munavalli, G.S.; Smith, S.; Maslowski, J.M.; Weiss, R.A. Successful treatment of depressed, distensible acne scars using autologous fibroblasts: A multi-site, prospective, double blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Dermatol. Surg 2013, 39, 1226–1236. [Google Scholar]

- Eca, L.P.; Pinto, D.G.; de Pinho, A.M.; Mazzetti, M.P.; Odo, M.E. Autologous fibroblast culture in the repair of aging skin. Dermatol. Surg 2012, 38, 180–184. [Google Scholar]

- Obaid, H.; Clarke, A.; Rosenfeld, P.; Leach, C.; Connell, D. Skin-derived fibroblasts for the treatment of refractory Achilles tendinosis: Preliminary short-term results. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. Vol 2012, 94, 193–200. [Google Scholar]

- Connell, D.; Datir, A.; Alyas, F.; Curtis, M. Treatment of lateral epicondylitis using skin-derived tenocyte-like cells. Br. J. Sports Med 2009, 43, 293–298. [Google Scholar]

- Shevtsov, M.A.; Galibin, O.V.; Yudintceva, N.M.; Blinova, M.I.; Pinaev, G.P.; Ivanova, A.A.; Savchenko, O.N.; Suslov, D.N.; Potokin, I.L.; Pitkin, E.; et al. Two-stage implantation of the skin- and bone-integrated pylon seeded with autologous fibroblasts induced into osteoblast differentiation for direct skeletal attachment of limb prostheses. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.K.; Kim, S.Y.; Choi, R.J.; Jeong, S.H.; Kim, W.K. Comparison of tissue-engineered and artificial dermis grafts after removal of basal cell carcinoma on face-A pilot study. Dermatol. Surg 2014, 40, 460–467. [Google Scholar]

- Karr, J.C. Retrospective comparison of diabetic foot ulcer and venous stasis ulcer healing outcome between a dermal repair scaffold (PriMatrix) and a bilayered living cell therapy (Apligraf). Adv. Skin Wound Care 2011, 24, 119–125. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, N.E.; Avram, M.R. Medical treatments for male and female pattern hair loss. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol 2008, 59, 547–566, quiz 567–568. [Google Scholar]

- Nieves, A.; Garza, L.A. Does Prostaglandin D2 hold the cure to male pattern baldness? Exp. Dermatol 2014, 23, 224–227. [Google Scholar]

- Dhouailly, D. Dermo-epidermal interactions between birds and mammals: Differentiation of cutaneous appendages. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol 1973, 30, 587–603. [Google Scholar]

- Jahoda, C.A.; Horne, K.A.; Oliver, R.F. Induction of hair growth by implantation of cultured dermal papilla cells. Nature 1984, 311, 560–562. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H.Y.; Chi, J.T. Diversity, topographic differentiation, and positional memory in human fibroblasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 12877–12882. [Google Scholar]

- Rinn, J.L.; Wang, J.K.; Allen, N.; Brugmann, S.A.; Mikels, A.J.; Liu, H.; Ridky, T.W.; Stadler, H.S.; Nusse, R.; Helms, J.A.; et al. A dermal HOX transcriptional program regulates site-specific epidermal fate. Genes Dev 2008, 22, 303–307. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.C.; Helms, J.A.; Chang, H.Y. Regeneration, repair and remembering identity: The three Rs of HOX gene expression. Trends Cell Biol 2009, 19, 268–275. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi, Y.; Itami, S.; Tarutani, M.; Hosokawa, K.; Miura, H.; Yoshikawa, K. Regulation of keratin 9 in nonpalmoplantar keratinocytes by palmoplantar fibroblasts through epithelial-mesenchymal interactions. J. Investig. Dermatol 1999, 112, 483–488. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi, Y.; Itami, S.; Watabe, H.; Yasumoto, K.; Abdel-Malek, Z.A.; Kubo, T.; Rouzaud, F.; Tanemura, A.; Yoshikawa, K.; Hearing, V.J. Mesenchymal-epithelial interactions in the skin: Increased expression of dickkopf1 by palmoplantar fibroblasts inhibits melanocyte growth and differentiation. J. Cell Biol 2004, 165, 275–285. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi, Y.; Passeron, T.; Hoashi, T.; Watabe, H.; Rouzaud, F.; Yasumoto, K.; Hara, T.; Tohyama, C.; Katayama, I.; Miki, T.; et al. Dickkopf 1 (DKK1) regulates skin pigmentation and thickness by affecting Wnt/β-catenin signaling in keratinocytes. FASEB J 2008, 22, 1009–1020. [Google Scholar]

- Boulton, A.J.; Kirsner, R.S.; Vileikyte, L. Clinical practice. Neuropathic diabetic foot ulcers. N. Engl. J. Med 2004, 351, 48–55. [Google Scholar]

- Brem, H.; Kirsner, R.S.; Falanga, V. Protocol for the successful treatment of venous ulcers. Am. J. Surg 2004, 188, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Charles, C.A.; Tomic-Canic, M.; Vincek, V.; Nassiri, M.; Stojadinovic, O.; Eaglstein, W.H.; Kirsner, R.S. A gene signature of nonhealing venous ulcers: Potential diagnostic markers. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol 2008, 59, 758–771. [Google Scholar]

- Zaulyanov, L.; Kirsner, R.S. A review of a bi-layered living cell treatment (Apligraf) in the treatment of venous leg ulcers and diabetic foot ulcers. Clin. Interv. Aging 2007, 2, 93–98. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, C. FDA approves first cell therapy for wrinkle-free visage. Nat. Biotechnol 2011, 29, 674–675. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, N.B.; Garza, L.A.; Foote, C.E.; Kang, S.; Meyerle, J.H. High prevalence of stump dermatoses 38 years or more after amputation. Arch. Dermatol 2012, 148, 1283–1286. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, R.A.; Grove, G. Human skin fibroblasts derived from papillary and reticular dermis: Differences in growth potential in vitro. Science 1979, 204, 526–527. [Google Scholar]

- Mine, S.; Fortunel, N.O.; Pageon, H.; Asselineau, D. Aging alters functionally human dermal papillary fibroblasts but not reticular fibroblasts: A new view of skin morphogenesis and aging. PLoS One 2008, 3, e4066. [Google Scholar]

- Schonherr, E.; Beavan, L.A.; Hausser, H.; Kresse, H.; Culp, L.A. Differences in decorin expression by papillary and reticular fibroblasts in vivo and in vitro. Biochem. J. 1993, 290, 893–899. [Google Scholar]

- Janson, D.G.; Saintigny, G.; van Adrichem, A.; Mahe, C.; El Ghalbzouri, A. Different gene expression patterns in human papillary and reticular fibroblasts. J. Investig. Dermatol 2012, 132, 2565–2572. [Google Scholar]

- Pageon, H.; Zucchi, H.; Asselineau, D. Distinct and complementary roles of papillary and reticular fibroblasts in skin morphogenesis and homeostasis. Eur. J. Dermatol 2012, 22, 324–332. [Google Scholar]

- Tajima, S.; Pinnell, S.R. Collagen synthesis by human skin fibroblasts in culture: Studies of fibroblasts explanted from papillary and reticular dermis. J. Investig. Dermatol 1981, 77, 410–412. [Google Scholar]

- Sorrell, J.M.; Baber, M.A.; Caplan, A.I. Site-matched papillary and reticular human dermal fibroblasts differ in their release of specific growth factors/cytokines and in their interaction with keratinocytes. J. Cell. Physiol 2004, 200, 134–145. [Google Scholar]

- Varkey, M.; Ding, J.; Tredget, E.E. Differential collagen-glycosaminoglycan matrix remodeling by superficial and deep dermal fibroblasts: Potential therapeutic targets for hypertrophic scar. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 7581–7591. [Google Scholar]

- Jahoda, C.A.; Reynolds, A.J. Hair follicle dermal sheath cells: Unsung participants in wound healing. Lancet 2001, 358, 1445–1448. [Google Scholar]

- Botchkarev, V.A.; Paus, R. Molecular biology of hair morphogenesis: Development and cycling. J. Exp. Zool. B 2003, 298, 164–180. [Google Scholar]

- Kramann, R.; DiRocco, D.P.; Humphreys, B.D. Understanding the origin, activation and regulation of matrix-producing myofibroblasts for treatment of fibrotic disease. J. Pathol 2013, 231, 273–289. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, J.; Zawadzka, A.; Philips, E.; Turetsky, A.; Batchelor, S.; Peacock, J.; Durrant, S.; Garlick, D.; Kemp, P.; Teumer, J. Hair follicle neogenesis induced by cultured human scalp dermal papilla cells. Regen. Med 2009, 4, 667–676. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, M.H.; van Exan, R.J.; Sonstegard, K.S.; Sweeny, P.R. Basal lamina changes during tissue interactions in hair follicles–An in vitro study of normal dermal papillae and vitamin A-induced glandular morphogenesis. J. Investig. Dermatol 1983, 80, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, R.; Guerrero-Juarez, C.F.; Plikus, M.V. Hair follicle signaling networks: A dermal papilla-centric approach. J. Investig. Dermatol 2013, 133, 2306–2308. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.C.; Chuong, C.M. Multi-layered environmental regulation on the homeostasis of stem cells: The saga of hair growth and alopecia. J. Dermatol. Sci 2012, 66, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.C.; Cotsarelis, G. Review of hair follicle dermal cells. J. Dermatol. Sci 2010, 57, 2–11. [Google Scholar]

- Christoph, T.; Muller-Rover, S.; Audring, H.; Tobin, D.J.; Hermes, B.; Cotsarelis, G.; Ruckert, R.; Paus, R. The human hair follicle immune system: Cellular composition and immune privilege. Br. J. Dermatol 2000, 142, 862–873. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, R.P.; Haycock, J.W.; Jahoda, C.A. Human hair follicle dermal cells and skin fibroblasts show differential activation of NFκB in response to pro-inflammatory challenge. Exp. Dermatol 2012, 21, 158–160. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, A.J.; Lawrence, C.; Cserhalmi-Friedman, P.B.; Christiano, A.M.; Jahoda, C.A. Trans-gender induction of hair follicles. Nature 1999, 402, 33–34. [Google Scholar]

- McElwee, K.J.; Kissling, S.; Wenzel, E.; Huth, A.; Hoffmann, R. Cultured peribulbar dermal sheath cells can induce hair follicle development and contribute to the dermal sheath and dermal papilla. J. Invest. Dermatol 2003, 121, 1267–1275. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Deng, Z.; Wang, H.; Yang, Z.; Guo, W.; Li, Y.; Ma, D.; Yu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, Y. Expansion and delivery of human fibroblasts on micronized acellular dermal matrix for skin regeneration. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 2666–2674. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, C.A.; Chen, J.C.; Cerise, J.E.; Jahoda, C.A.; Christiano, A.M. Microenvironmental reprogramming by three-dimensional culture enables dermal papilla cells to induce de novo human hair-follicle growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 19679–19688. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, C.A.; Richardson, G.D.; Ferdinando, D.; Westgate, G.E.; Jahoda, C.A. Modelling the hair follicle dermal papilla using spheroid cell cultures. Exp. Dermatol 2010, 19, 546–548. [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto, N.; Takemoto, S.; Kanda, N.; Ayvazyan, A.; Taira, M.T.; Suzuki, S. The utilization of animal product-free media and autologous serum in an autologous dermal substitute culture. J. Surg. Res 2011, 171, 339–346. [Google Scholar]

- Mazlyzam, A.L.; Aminuddin, B.S.; Saim, L.; Ruszymah, B.H. Human serum is an advantageous supplement for human dermal fibroblast expansion: Clinical implications for tissue engineering of skin. Arch. Med. Res 2008, 39, 743–752. [Google Scholar]

- Aoi, N.; Inoue, K.; Chikanishi, T.; Fujiki, R.; Yamamoto, H.; Kato, H.; Eto, H.; Doi, K.; Itami, S.; Kato, S.; et al. 1α,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 modulates the hair-inductive capacity of dermal papilla cells: Therapeutic potential for hair regeneration. Stem Cells Transl. Med 2012, 1, 615–626. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.H.; Yoon, J.; Shin, S.H.; Zahoor, M.; Kim, H.J.; Park, P.J.; Park, W.S.; Min do, S.; Kim, H.Y.; Choi, K.Y. Valproic acid induces hair regeneration in murine model and activates alkaline phosphatase activity in human dermal papilla cells. PLoS One 2012, 7, e34152. [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi, K.; Kurosaka, A. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 enhances the expression of alkaline phosphatase and insulin-like growth factor-1 in human primary dermal papilla cell culture and maintains mouse hair bulbs in organ culture. Arch. Dermatol. Res 2009, 301, 357–365. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.; Du, X.; Wang, W.; Boucher, M.; Parimoo, S.; Stenn, K. Organogenesis from dissociated cells: Generation of mature cycling hair follicles from skin-derived cells. J. Investig. Dermatol 2005, 124, 867–876. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, B.M.; Kwack, M.H.; Kim, M.K.; Kim, J.C.; Sung, Y.K. Sphere formation increases the ability of cultured human dermal papilla cells to induce hair follicles from mouse epidermal cells in a reconstitution assay. J. Investig. Dermatol 2012, 132, 237–239. [Google Scholar]

- Thangapazham, R.L.; Klover, P.; Wang, J.A.; Zheng, Y.; Devine, A.; Li, S.; Sperling, L.; Cotsarelis, G.; Darling, T.N. Dissociated human dermal papilla cells induce hair follicle neogenesis in grafted dermal-epidermal composites. J. Investig. Dermatol 2014, 134, 538–540. [Google Scholar]

- McElwee, K.; Hall, P.D.D.; Hoffmann, R. Towards a cell-based treatment for androgenetic alopecia in men and women: 12-Month interim safety results of a phase 1/2a clinical trial using autologous dermal sheath cup cell injections. Proceedings of the 7th World Congress for Hair Research, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK, 4–6 May 2013; Nature Publishing Group: Edinburgh, UK, 2013; 113, pp. 1391–1439. [Google Scholar]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Thangapazham, R.L.; Darling, T.N.; Meyerle, J. Alteration of Skin Properties with Autologous Dermal Fibroblasts. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 8407-8427. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms15058407

Thangapazham RL, Darling TN, Meyerle J. Alteration of Skin Properties with Autologous Dermal Fibroblasts. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2014; 15(5):8407-8427. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms15058407

Chicago/Turabian StyleThangapazham, Rajesh L., Thomas N. Darling, and Jon Meyerle. 2014. "Alteration of Skin Properties with Autologous Dermal Fibroblasts" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 15, no. 5: 8407-8427. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms15058407

APA StyleThangapazham, R. L., Darling, T. N., & Meyerle, J. (2014). Alteration of Skin Properties with Autologous Dermal Fibroblasts. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 15(5), 8407-8427. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms15058407