Multifunctional Composites of Chiral Valine Derivative Schiff Base Cu(II) Complexes and TiO2

Abstract

:1. Introduction

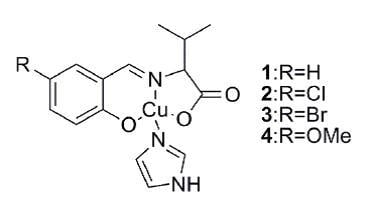

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Crystal Structures

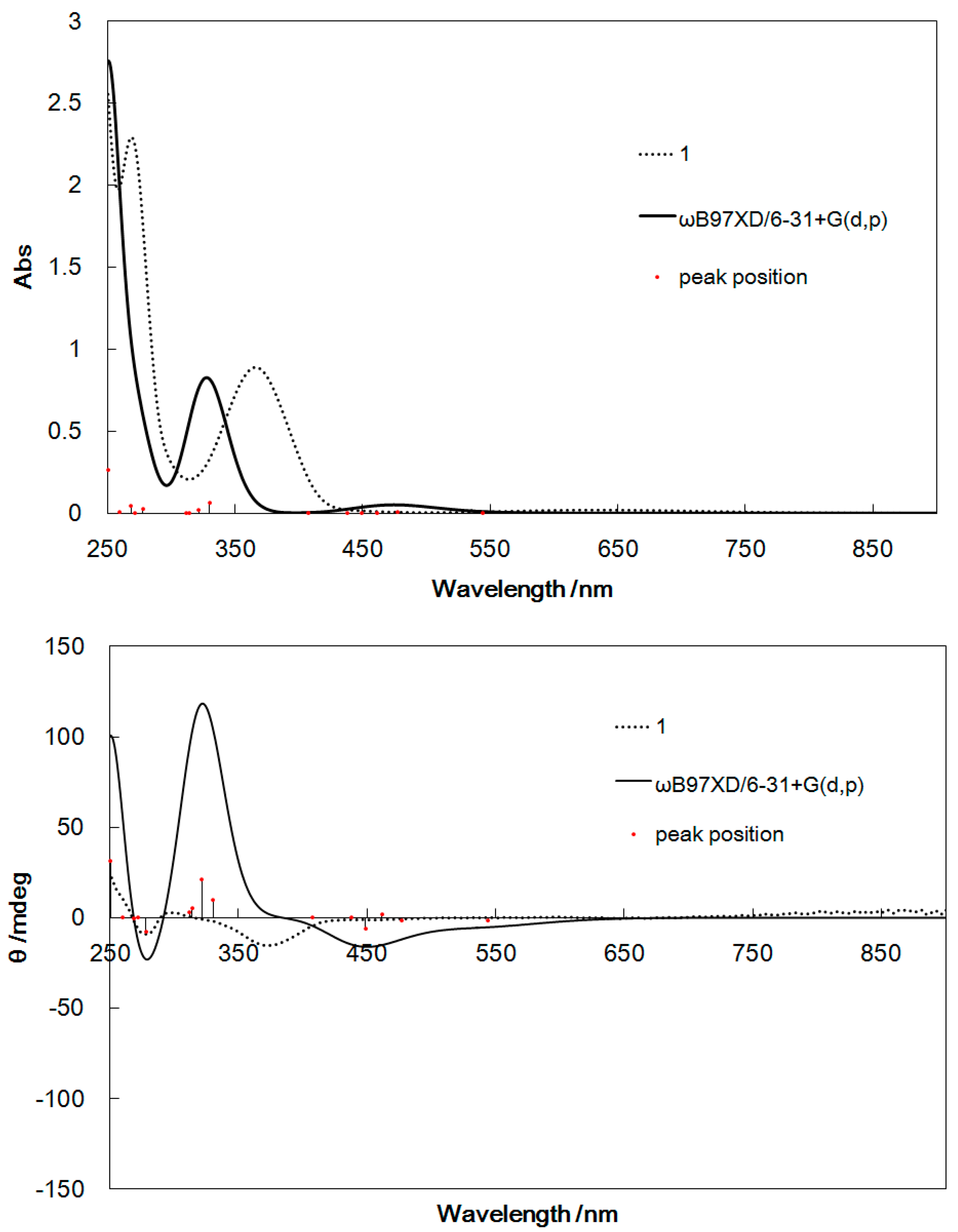

2.2. UV–Vis and CD Spectra

2.3. Redox Potential

2.4. Computational Results

2.5. UV Light-Induced Reactions

3. Experimental Section

3.1. General Procedures

3.2. Preparations

3.2.1. Preparation of 1

3.2.2. Preparation of 2

3.2.3. Preparation of 3

3.2.4. Preparation of 4

3.3. Physical Measurements

3.4. X-ray Crystallography

3.4.1. Crystallographic Data for 1

3.4.2. Crystallographic Data for 2

3.4.3. Crystallographic Data for 4

3.5. Computational Methods

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Walters, C.; Keeney, A.; Wigal, C.T.; Johnston, C.R.; Cornelius, R.D. UV spectra and cost analysis of suntan lotions: A simple introduction to the use of recording spectrophotometers. J. Chem. Educ. 1997, 74, 99–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazawa, M. Cosmetic Science; Kyoritsu Shuppan: Tokyo, Japan, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fujishige, S.; Takizawa, S. A simple preparative method to evaluate total UV protection by commercial sunscreens. J. Chem. Educ. 2001, 78, 1678–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeur, H.P.; Zanella, A.; Poon, T. An introduction to UV–Vis spectroscopy using sunscreens. J. Chem. Educ. 2006, 83, 769–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, H.; Chen, D.; Junlv, X.; Wang, Y.; Hongli, J. Energy-efficient photodegradation of azo dyes with TiO2 nanoparticles based on photoisomerization and alternate UV–visible light. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 1107–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abney, J.R.; Scalettar, B.A. Saving your students’ skin: Undergraduate experiments that probe UV protection by sunscreens and sunglasses. J. Chem. Educ. 1998, 75, 757–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Buyukcakir, O.; Mara, M.W.; Coskun, A.; Dimitrijevic, N.M.; Barin, G.; Kokhan, O.; Stickrath, A.B.; Ruppert, R.; Tiede, D.M.; et al. Highly efficient ultrafast electron injection from the singlet MLCT excited state of copper(I) diimine complexes to TiO2 nanoparticles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 12711–12715. [Google Scholar]

- Mosconi, E.; Yum, J.; Kessler, F.; García, C.J.G.; Zuccaccia, C.; Cinti, A.; Nazeeruddin, M.K.; Grätzel, M.; Angelis, F.D. Cobalt electrolyte/dye interactions in dye-sensitized solar cells: A combined computational and experimental study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 19438–19453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- G-Oliveros, G.; Ortega, F.M.; P-Mozo1, E.; Ferronato, C.; Chovelon, J.M. Photoactivity of metal-phenylporphyrins adsorbed on TiO2 under visible light radiation: Influence of central metal. Open Mater. Sci. J. 2010, 4, 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Magni, M.; Colomboa, A.; Dragonetti, C.; Mussini, P. Steric vs. electronic effects and solvent coordination in the electrochemistry of phenanthroline-based copper complexes. Electrochim. Acta 2014, 141, 324–330. [Google Scholar]

- Colombo, A.; Dragonetti, C.; Magni, M.; Roberto, D.; Demartin, F.; Caramori, S.; Bignozzi, C.A. Efficient copper mediators based on bulky asymmetric phenanthrolines for DSSCs. Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 13945–13955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaki, S.; Kurokib, T.; Hamada, T. Synthesis of a new copper(I) complex, [Cu(tmdcbpy)2]+ (tmdcbpy = 4,4',6,6'-tetramethyl-2,2'-bipyridine-5,5'-dicarboxylic acid), and its application to solar cells. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 2002, 6, 840–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akitsu, T.; Ishiguro, Y.; Yamamoto, S.; Nishizuru, H. Tuning electronic states of some copper complexes by titanium dioxide photocatalyst. Asian Chem. Lett. 2010, 14, 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Akitsu, T.; Yamamoto, S. Spectroscopic detection of photofunctional systems of copper(II) complexes, azo-dye, and TiO2. Asian Chem. Lett. 2010, 14, 255–260. [Google Scholar]

- Akitsu, T.; Nishizuru, H. Tuning of electronic states of copper(II) complexes showing equilibrium of coordination in solutions. Asian Chem. Lett. 2010, 14, 261–266. [Google Scholar]

- Nishizuru, H.; Kimura, N.; Akitsu, T. Photo-induced reduction of hybrid systems of phenylalanine and other derivatives of Schiff base Cu(II) complexes and titanium(IV) oxide. Asian Chem. Lett. 2012, 16, 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, Y.; Akitsu, T. Preparations of hybrid systems of l-amino acid derivatives of Schiff base Cu(II) and Zn(II) complexes and polyoxometalates. Asian Chem. Lett. 2012, 16, 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, S.; Akitsu, T. Fluorescence detection by photochromic dye of photoinduced electron transfer reactions between lysine and methionine derivative Schiff base copper(II) complexes and titanium oxide. Asian Chem. Lett. 2011, 15, 203–209. [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama, T.; Minemoto, M.; Nishizuru, H.; Akitsu, T. Spectroelectrochemistry of photoinduced electron transfer reactions between leucine and serine derivative Schiff base copper(II) complexes and titanium Oxide. Asian Chem. Lett. 2011, 15, 215–219. [Google Scholar]

- Kurata, M.; Yoshida, N.; Fukunaga, S.; Akitsu, T. Proposed mechanism of photo-induced reactions of chiral threonine Schiff base Cu(II) complexes with imidazole by TiO2. Contemp. Eng. Sci. 2013, 6, 255–260. [Google Scholar]

- Takeshita, Y.; Nogami, A.; Akitsu, T. UV light-induced reaction of chiral arginine derivative-schiff base Cu(II) complexes and TiO2. World Sci. Echo 2014, 1, 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, J.D.; Head-Gordon, M. Long-range corrected hybrid density functionals with damped atom–atom dispersion corrections. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2008, 10, 6615–6620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeshita, Y.; Akitsu, T. Multi-functional composite and substituent effects of chiral Schiff base Cu(II) complexes and titanium(IV) oxide. Trends Photochem. Photobiol. 2015, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Bruker. SMART and SAINT; Bruker AXS Inc.: Madison, WI, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick, G.M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. A 2008, 64, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SADABS; Program for Empirical Absorption, Correction of Area Detector Data; University of Gottingen: Göttingen, Germany, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Mennucci, B.; Petersson, G.A.; et al. Gaussian 09, Revision D.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Takeshita, Y.; Takakura, K.; Akitsu, T. Multifunctional Composites of Chiral Valine Derivative Schiff Base Cu(II) Complexes and TiO2. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 3955-3969. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms16023955

Takeshita Y, Takakura K, Akitsu T. Multifunctional Composites of Chiral Valine Derivative Schiff Base Cu(II) Complexes and TiO2. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2015; 16(2):3955-3969. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms16023955

Chicago/Turabian StyleTakeshita, Yuki, Kazuya Takakura, and Takashiro Akitsu. 2015. "Multifunctional Composites of Chiral Valine Derivative Schiff Base Cu(II) Complexes and TiO2" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 16, no. 2: 3955-3969. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms16023955

APA StyleTakeshita, Y., Takakura, K., & Akitsu, T. (2015). Multifunctional Composites of Chiral Valine Derivative Schiff Base Cu(II) Complexes and TiO2. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 16(2), 3955-3969. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms16023955