Essential Oils from Neotropical Piper Species and Their Biological Activities

Abstract

1. Introduction

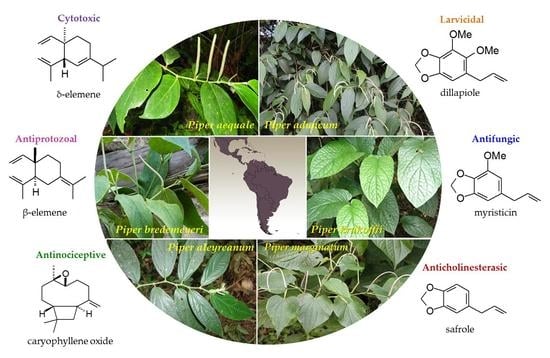

2. Volatile Profiles

3. Biological Activities

3.1. Antibacterial and Antifungal Activity

3.2. Antiprotozoal Activity

3.3. Anticholinesterase Potential

3.4. Anti-Inflammatory and Antinociceptive Effects

3.5. Cytotoxic Activity

4. Composition-Bioactivity Correlation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACh | Acetylcholine |

| AChE | Acetylcholine esterase |

| DL | Detection limit |

| DPPH | 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (radical) |

| EO | Essential oil |

| FIOCRUZ | Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (Oswaldo Cruz Foundation) |

| GC-MS | Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry |

| HD | Hydrodistillation |

| IC50 | Median inhibitory concentration |

| ID50 | Median inhibitory dose |

| LC50 | Median lethal concentration |

| MFC | Minimum fungicidal concentration |

| MH | Monoterpene hydrocarbons |

| MIC | Minimum inhibitory concentration |

| MWHD | Microwave-assisted hydrodistillation |

| OM | Oxygenated monoterpenoids |

| OS | Oxygenated sesquiterpenoids |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| PP | Phenylpropanoids |

| RI | Retention index |

| SD | Steam distillation |

| SH | Sesquiterpene hydrocarbons |

| spp. | Species (plural) |

| TLC | Thin-layer chromatography |

Appendix A

| Piper species | Collection Site | Essential Oil | Major Components (>5%) | Bioactivity of EO | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. abutiloides Kunth | Cultivated (State University of Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil) | Leaf (HD) | --- | Antibacterial (Escherichia coli, MIC 700 μg/mL) | [52] |

| P. acutifolium Ruiz & Pav. | La Florida, Cajamarca, Peru | Leaf (HD) | (E)-β-Ocimene (8.1%), α-copaene (6.1%), β-caryophyllene (7.9%), allo-aromadendrene (6.0%), α-cadinene (6.7%), δ-cadinene (6.8%), dillapiole (5.9%) | --- | [99] |

| P. aduncum L. | Serra do Navio, Amapá state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | Limonene (5.2%), γ-terpinene (7.1%), terpinen-4-ol (11.0%), piperitone (15.1%), dillapiole (31.5%) | --- | [15] |

| P. aduncum L. | Melgaço, Pará state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | γ-Terpinene (6.5%), terpinen-4-ol (7.3%), piperitone (13.9%), dillapiole (50.8%) | --- | [15] |

| P. aduncum L. | Benfica, Pará state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | Piperitone (7.0%), dillapiole (56.3%) | --- | [15] |

| P. aduncum L. | Belém, Pará state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | Dillapiole (82.2%) | --- | [15] |

| P. aduncum L. | Belém, Pará state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | Dillapiole (86.9%) | --- | [15] |

| P. aduncum L. | Manaus, Amazonas state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | Dillapiole (91.1%) | --- | [15] |

| P. aduncum L. | Manaus-Caracaraí, Amazonas, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | Dillapiole (97.3%) | --- | [15] |

| P. aduncum L. | Cruzero do Sul, Acre state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | Dillapiole (88.1%) | --- | [15] |

| P. aduncum L. | Pinar del Río, Cuba | Leaf (HD) | Dillapiole (82.2%) | --- | [27] |

| P. aduncum L. | Valle del Sajta, Cochabamba, Bolivia | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (9.0%), β-pinene (7.1%), limonene (5.0%), 1,8-cineole (40.5%), asaricin (12.9%) | --- | [100] |

| P. aduncum L. | Altos de Campana National Park, Panama | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (8.8%), linalool (8.6%), β-caryophyllene (17.4%), aromadendrene (13.4%) | --- | [100] |

| P. aduncum L. | Reserva da Ripasa, Ibaté, São Paulo state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | (E)-β-Ocimene (5.0%), linalool (31.7%), β-caryophyllene (9.1%), α-humulene (5.5%), bicyclogermacrene (11.2%), (E)-nerolidol (10.4%) | Antifungal, TLC bioautography (Cladosporium sphareospermum) | [59] |

| P. aduncum L. | Reserva da Ripasa, Ibaté, São Paulo state, Brazil | Floral (HD) a | α-Terpinene (6.8%), (Z)-β-ocimene (5.6%), (E)-β-ocimene (11.1%), γ-terpinene (12.0%), linalool (41.2%), (E)-nerolidol (6.1%) | --- | [59] |

| P. aduncum L. | Reserva da Ripasa, Ibaté, São Paulo state, Brazil | Stem (HD) | α-Pinene (7.2%), β-pinene (14.2%), limonene (8.7%), (Z)-β-ocimene (5.5%), (E)-β-Ocimene (13.3%), linalool (11.8%), β-caryophyllene (7.6%), α-humulene (6.3%), (E)-nerolidol (10.6%) | Antifungal, TLC bioautography (Cladosporium cladosporioides, Cladosporium sphareospermum) | [59] |

| P. aduncum L. | Brejo da Madre de Deus, Matas Serranas, Pernambuco state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | (E)-Nerolidol (80.6–82.5%), longipinanol (2.4–5.6%) | --- | [26] |

| P. aduncum L. | Serra Negra, Matas Serranas, Pernambuco state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | (E)-Nerolidol (79.2–81.2%), longipinanol (11.1–13.6%) | --- | [26] |

| P. aduncum L. | Cultivated (State University of Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil) | Leaf (HD) | --- | Antibacterial (Escherichia coli, MIC 500 μg/mL) | [52] |

| P. aduncum L. | Bulo Bulo, Bolivia | Leaf (SD) | α-Pinene (8.0–8.9%), β-pinene (6.6–7.0%), 1,8-cineole (42.0–42.5%), (E)-β-ocimene (6.4%), bicyclogermacrene (3.8–6.0%), asaricin (9.2–10.5%) | --- | [101] |

| P. aduncum L. | Wasak'entsa reserve, Ecuador | Aerial parts (HD) | (E)-β-Ocimene (10.4%), piperitone (8.5%), dillapiole (45.9%) | Antifungal activity against dermatophytes (Trichophyton mentagrophytes, MIC 500 μg/mL, IC50 92.7 μg/mL; Trichophyton tonsurans, MIC 500 μg/mL, IC50 108.7 μg/mL; Nantzzia cajetani, IC50 195 μg/mL) | [65] |

| P. aduncum L. | Ducke Reserve, Manaus, Amazonas state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | Dillapiole (94.8%) | Acaricidal (Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus, LC50 9.3 mg/mL) | [28] |

| P. aduncum L. | Santo Antonio do Tauá, Pará state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | Dillapiole (86.9%) | Larvicidal and insecticidal activity against mosquitoes (Anopheles marajoara, LC50 50.9 μg/mL, 417 μg/mL, respectively; Aedes aegypti, LC50 54.5 μg/mL, 401 μg/mL, respectively) | [16] |

| P. aduncum L. | Araraquara, São Paulo state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | (E)-β-Ocimene (5.0%), linalool (31.8%), β-caryophyllene (9.3%), α-humulene (5.5%), bicyclogermacrene (11.3%), (E)-nerolidol (10.3%) | Antifungal, broth dilution assay (Cryptococcus neoformans, MIC 62.5 μg/mL) | [35] |

| P. aduncum L. | Brazlândia, Distrito Federal, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | β-Phellandrene (6.8%), γ-terpinene (8.3%), terpinen-4-ol (15.0%), piperitone (22.7%), asaricin (5.6%) | --- | [16] |

| P. aduncum L. | Parque do Guará, Distrito Federal, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | β-Phellandrene (6.6%), γ-terpinene(8.2%), terpinen-4-ol (16.8%), piperitone (24.9%) | --- | [16] |

| P. aduncum L. | Córrego Bananal, Distrito Federal, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | (E)-β-Ocimene (11.6%), terpinen-4-ol (6.7%), piperitone (11.0%), asaricin (15.8%) | --- | [16] |

| P. aduncum L. | Fazenda Água Limpa, Distrito Federal, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | Piperitone (16.3%), dillapiole (49.5%) | --- | [16] |

| P. aduncum L. | Mata de Dois Irmãos, Recife, Pernambuco, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | Dillapiole (79.0%) | --- | [29] |

| P. aduncum L. | Belém, Pará state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | Dillapiole (64.4%) | Insecticidal (Solenopsis saevissima, IC50 135 μg/mL) | [41] |

| P. aduncum L. | Bocaiuva, Minas Gerais state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (14.2%), β-pinene (9.0%), 1,8-cineole (57.2%) | --- | [25] |

| P. aduncum L. | Montes Claros, Minas Gerais state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | (E)-β-Ocimene (13.4%), valencene (6.9%), (E)-nerolidol (5.9%) | --- | [25] |

| P. aduncum L. | Topes de Collantes Nature Reserve, Escambray Mountains, Cuba | Leaf (HD) | Camphene (10.9%), 1,8-cineole (8.7%), camphor (17.1%), piperitone (34.0%), viridiflorol (7.4%) | Antioxidant (DPPH radical scavenging assay, IC50 30.1 μg/mL) | [50] |

| P. aduncum L. | Gallery Forest, Angico River, Minas Gerais state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | 1,8-Cineole (55.8%), α-terpineol (5.9%) | Egg hatch inhibition (Haemonchus contortus, IC50 2.6 mg/mL) | [102] |

| P. aduncum L. | Santo Antonio do Tauá, Pará state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | Dillapiole (85.9%) | Antifungal activity against dermatophytes (Trichophyton mentagrophytes, MIC 500 μg/mL; Epidermophyton floccosum, MIC 500 μg/mL; Microsporum canis, MIC 250 μg/mL; Microsporum gypseum, MIC 250 μg/mL; Aspergillus fumigatus, MIC 3.9 μg/mL) | [30] |

| P. aduncum L. | Cultivated, Federal University of Lavras, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | Linalool (9.3–13.4%), β-caryophyllene (5.1–6.7%), α-humulene (8.5–10.6%), (E)-nerolidol (14.3–16.7%), spathulenol (0–5.6%), cis-cadin-4-en-7-ol (7.5–12.2%) | --- | [103] |

| P. aduncum L. | Cultivated, Federal University of Lavras, Brazil | Root (HD) | α-Selinene (14.1–16.5%), geranyl 2-methylbutyrate (8.9–13.6%), bulnesol (4.6–6.1%), elemicin (4.6–5.9%), dillapiole (13.0–18.4%), apiole (16.3–29.5%) | --- | [103] |

| P. aduncum L. | Monte Alegre do Sul, São Paulo state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (6.4%), safrole (13.3%), valencene (9.7%), spathulenol (10.6%), asaricin (14.9%) | --- | [31] |

| P. aduncum L. | Votuporanga, São Paulo state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | Safrole (10.8%), asaricin (80.1%) | --- | [31] |

| P. aduncum L. | Votuporanga, São Paulo state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | Safrole (10.5%), asaricin (73.4%) | --- | [31] |

| P. aduncum L. | Belém, Pará state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | Dillapiole (73.0%) | --- | [62] |

| P. aduncum L. | Cerro Azul, Paraná state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | (Z)-β-Ocimene (7.0%), (E)-β-ocimene (13.9%), safrole (6.2%), bicyclogermacrene (20.9%), γ-cadinene (5.5%), spathulenol (5.3%) | Antileishmanial (L. amazonensis promastigotes, IC50 25.9 μg/mL; L. amazonensis axenic amastigotes, IC50 36.2 μg/mL) | [70] |

| P. aduncum L. | Universidade Federal de Lavras, Matto Grosso state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | Linalool (13.4%), (E)-nerolidol (25.2%), spathulenol (6.3%) | Antitrypanosomal (T. cruzi trypomastigotes, IC50 2.8 μg/mL; linalool is the active agent, IC50 0.31 μg/mL) Antileishmanial (L. braziliensis promatigotes, IC50 77.9 μg/mL; (E)-nerolidol is the active agent, IC50 74.3 μg/mL) | [67,68] |

| P. aduncum L. | Institute of Pharmacy and Food, Havana, Cuba | Aerial parts (HD) | Camphene (5.9%), camphor (17.1%) piperitone (23.7%), viridiflorol (14.5%) | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium falciparum, IC50 1.3 μg/mL; Trypanosoma brucei, IC50 2.0 μg/mL; Trypanosoma cruzi, IC50 2.1 μg/mL; Leishmania amazonensis, IC50 23.8 μg/mL; Leishmania donovani, IC50 7.7 μg/mL; Leishmania infantum, IC50 8.1 μg/mL) | [32] |

| P. aduncum subsp. ossanum (C. DC.) Saralegui [syn. P. ossanum (C. DC.) Trel.] | Pinar del Río, Cuba | Leaf (HD) | Camphene (6.1%), camphor (8.3%), piperitone (12.9%), β-caryophyllene (6.7%), germacrene D (8.2%), 1-epi-cubenol (6.2%) | --- | [104] |

| P. aduncum subsp. ossanum (C. DC.) Saralegui [syn. P. ossanum (C. DC.) Trel.] | Artemisa Province, Cuba | Leaf (HD) | Camphene (5.4–7.4%), camphor (9.4–13.9%), piperitone (19.0–20.1%), viridiflorol (13.0–18.8%) | Antiprotozoal (Plasmodium falciparum, IC50 1.5 μg/mL; Trypanosoma brucei, IC50 8.1 μg/mL; Trypanosoma cruzi, IC50 8.0 μg/mL; Leishmania amazonensis, IC50 19.3 μg/mL; Leishmania infantum, IC50 32.5 μg/mL), antibacterial (Staphylococcus aureus, IC50 39.5 μg/mL) | [53] |

| P. aequale Vahl | Monteverde, Costa Rica | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (39.3%), sabinene (18.4%), limonene (6.7%) | Antibacterial (Bacillus cereus, MIC 156 μg/mL) | [34] |

| P. aequale Vahl | Carajás National Forest, Parauapebas, Pará state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | α-Pinene (12.6%), β-pinene (15.6%), δ-elemene (19.0%), bicyclogermacrene (5.5%), cubebol (7.2%), β-atlantol (5.9%) | Cytotoxic (HCT-116 human colorectal carcinoma, IC50 8.69 μg/mL; ACP03 human gastric adenocarcinoma, IC50 1.54 μg/mL; essential oil induced apoptosis in ACP03 cells) | [95] |

| P. sp. aff. aereum | Monteverde, Costa Rica | Leaf (HD) | β-Caryophyllene (6.6%), δ-cadinene (7.3%), guaiol (41.2%), α-muurolol (5.8%), α-cadinol (9.2%) | Antibacterial (Bacillus cereus, MIC 78 μg/mL; Staphylococcus aureus, MIC 78 μg/mL), cytotoxic (MCF-7 human breast adenocarcinoma) | [34] |

| P. aleyreanum C. DC. | Porto Velho, Rondônia state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (7.0%), β-pinene (14.4%), α-phellandrene (8.6%), (Z)-caryophyllene (17.5%), β-caryophyllene (18.6%), δ-cadinene (6.2%) | --- | [105] |

| P. aleyreanum C. DC. | Porto Velho, Rondônia state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | Camphene (5.2%), β-pinene (9.0%), spathulenol (6.7%), caryophyllene oxide (11.5%) | Antinociceptive, anti-inflammatory (mouse model) | [90] |

| P. aleyreanum C. DC. | Carajás National Forest, Parauapebas, Pará state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | δ-Elemene (8.2%), β-elemene (16.3%), β-caryophyllene (6.2%), germacrene D (6.9%), bicyclogermacrene (9.2%), spathulenol (5.2%) | Antifungal, TLC bioautography (Cladosporium cladosporioides, Cladosporium sphaerospermum), cytotoxic (SKMel19 human melanoma, IC50 7.4 μg/mL) | [61] |

| P. amalago L. | Fazenda Sucupira, Embrapa, Brasília, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (30.5%), camphene (8.9%), limonene (6.8%), borneol (5.7%) | --- | [33] |

| P. amalago L. | Monteverde, Costa Rica | Leaf (HD) | α-Phellandrene (1.7–8.1%), β-elemene (11.5–24.6%), β-caryophyllene (15.9–23.3%), germacrene D (28.9–29.4%), germacrene A (6.5–9.7%) | --- | [34] |

| P. amalago L. | Morro Reuter, Rio Grande do Sul state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | α-Pinene (5.2%), limonene (20.5%), δ-elemene (6.8%), zingiberene (11.2%) | --- | [106] |

| P. amalago L. | Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | γ-Muurolene (7.3%), germacrene D (9.9%), bicyclogermacrene (27.9%), spathulenol (19.2%), α-cadinol (7.6%) | --- | [35] |

| P. amalago L. | Dourados, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | p-Cymene (9.4%), methyl geranate (7.8%), α-amorphene (25.7%), cubenol (6.2%) | --- | [107] |

| P. amalago L. | Dourados, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil | Stem (HD) | Longifolene (6.6%), α-amorphene (23.3%), α-muurolol (9.3%) | --- | [107] |

| P. amalago L. | Dourados, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil | Root (HD) | α-Amorphene (14.4%) | --- | [107] |

| P. amalago L. | Dourados, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil | Floral (HD) a | p-Cymene (9.3%), limonene (10.5%), silphiperfol-6-ene (13.5%), allo-aromadendrene (18.5%), α-muurolol (5.0%) | --- | [107] |

| P. amalago L. | Campinas, São Paulo state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (14.8%), β-phellandrene (39.3%), germacrene D (11.7%) | --- | [31] |

| P. amalago L. | Campinas, São Paulo state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (6.7%), sabinene (6.7%), β-phellandrene (15.9%), bicyclogermacrene (20.8%), spathulenol (9.1%) | --- | [31] |

| P. amalago L. | Campinas, São Paulo state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (11.7%), β-phellandrene (33.1%), bicyclogermacrene (15.0%) | --- | [31] |

| P. amalago L. | Adamantina, São Paulo state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | Sabinene (8.2%), myrcene (6.8%), β-phellandrene (12.3%), bicyclogermacrene (19.4%), γ-muurolene (5.9%), spathulenol (5.6%) | --- | [31] |

| P. amalago var. medium (Jacq.) Yunck. | Fênix, Paraná state, Brazil | Floral (HD) a | β-Phellandrene (7.3–8.2%), bicyclogermacrene (3.0–9.1%), δ-cadinene (2.3–6.6%), (E)-nerolidol (14.2–19.9%), germacrene D-4-ol (10.3–12.7%), τ-cadinol (4.9–6.1%), α-cadinol (8.2–11.1%) | --- | [108] |

| P. amplum Kunth | Pariquera-Açu, São Paulo state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (18.1%), (Z)-β-ocimene (10.5%), limonene (8.6%), β-caryophyllene (8.8%), germacrene D (5.5%) | --- | [31] |

| P. angustifolium Lam. | Cuzco, Peru | Aerial parts (HD) | Camphene (22.4%), camphor (25.3%), isoborneol (12.8%) | Antibacterial, broth dilution assay (Pseudomonas aeruginosa, MIC 30 μg/mL; Escherichia coli, MIC 100 μg/mL); antifungal, broth dilution assay (Trichophyton mentagrophytes, MIC 10 μg/mL; Candida albicans, MIC 50 μg/mL; Cryptococcus neoformans, MIC 50 μg/mL; Aspergillus flavus, MIC 100 μg/mL) | [109] |

| P. angustifolium Lam. | Abobral Subregion of the Pantanal of Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (5.9%), (E)-nerolidol (5.8%), spathulenol (23.8%), caryophyllene oxide (13.1%) | Antileishmanial (L. infantum amastigotes, IC50 1.43 μg/mL) | [69] |

| P. anonifolium Kunth | Bujaru, Pará state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | α-Pinene (41.1–45.7%), β-pinene (17.2–18.6%), limonene (6.1–8.5%), β-caryophyllene (2.5–6.3%) | --- | [110] |

| P. anonifolium Kunth | Santa Isabel, Pará state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | α-Pinene (53.1%), β-pinene (22.9%) | --- | [110] |

| P. anonifolium Kunth | Ananindeua, Pará state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | α-Pinene (7.3%), limonene (5.9%), ishwarane (19.1%), germacrene D (9.6%), α-eudesmol (33.5%) | --- | [110] |

| P. anonifolium Kunth | Carajás National Forest, Parauapebas, Pará state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | α-Pinene (8.8%), β-selinene (12.7%), α-selinene (11.9%), selin-11-en-4α-ol (20.0%) | Antifungal, TLC bioautography (Cladosporium cladosporioides, Cladosporium sphaerospermum); enzyme inhibitory, TLC bioautography (acetylcholinesterase) | [61] |

| P. arboreum Aubl. | Chepo, Panama | Leaf (HD) | β-Pinene (6.6%), α-copaene (7.4%), germacrene D (5.3%), δ-cadinene (25.8%), (E)-nerolidol (5.2%) | --- | [111] |

| P. arboreum Aubl. | Fazenda Sucupira, Embrapa, Brasília, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | Bicyclogermacrene (12.1%), spathulenol (8.4%), caryophyllene oxide (10.2%) b | --- | [33] |

| P. arboreum Aubl. | Universidade Estadual Paulista, Araraquara, São Paulo state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | β-Caryophyllene (25.1%), germacrene D (9.6%), bicyclogermacrene (49.5%) | --- | [59] |

| P. arboreum Aubl. | Universidade Estadual Paulista, Araraquara, São Paulo state, Brazil | Floral (HD) a | Limonene (6.3%), linalool (10.4%), β-elemene (5.3%), β-caryophyllene (6.6%), germacrene D (49.3%), germacrene A (8.5%) | --- | [59] |

| P. arboreum Aubl. | Universidade Estadual Paulista, Araraquara, São Paulo state, Brazil | Stem (HD) | δ-3-Carene (18.7%), α-copaene (9.0%), β-caryophyllene (26.5%), bicyclogermacrene (21.1%) | --- | [59] |

| P. arboreum Aubl. | Antonina, Paraná state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | α-Copaene (5.6%), β-caryophyllene (12.6%), trans-cadina-1(6),4-diene (9.6%), spathulenol (7.9%), caryophyllene oxide (5.9%), 1-epi-cubenol (10.4%), α-cadinol (5.4%) | Antileishmanial (L. amazonensis promastigotes, IC50 15.2 μg/mL; L. amazonensis axenic amastigotes, IC50 > 200 μg/mL) | [70] |

| P. arboreum var. latifolium (C. DC.) Yunck. | Rondônia state, Brazil | Leaf (SD) | Octanal (5.5%), germacrene D (72.9%), γ-elemene (6.8%) c | --- | [112] |

| P. artanthe C. DC. | San Migues, Santander, Colombia | Aerial parts (HD) | δ-Elemene (11.7%), β-caryophyllene (10.2%), epi-cubebol (8.9%), cubebol (6.3%), myristicin (6.4%), apiole (14.5%) | --- | [113] |

| P. augustum Rudge | Reserva Biológica Alberto Manuel Brenes, Costa Rica | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (10.5%), α-phellandrene (14.7%), limonene (13.0%), β-phellandrene (5.6%), linalool (10.3%), β-caryophyllene (13.5%) | --- | [114] |

| P. augustum Rudge | Valle de Anton, Cerro Caracoral, Cocle, Panama | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (6.0%), β-elemene (12.3%), cembrene (11.7%), cembratrienol 1 (25.4%), cembratrienol 2 (8.6%) | --- | [47] |

| P. auritum Kunth | Boca de Uracillo, Colon Province, Panama | Leaf (HD) | Safrole (70%) | --- | [115] |

| P. auritum Kunth | Güira de Melena, Cuba | Leaf (HD) | Safrole (64.5%) | --- | [116] |

| P. auritum Kunth | Monteverde, Costa Rica | Floral (HD) a | Safrole (93.2%) | --- | [49] |

| P. auritum Kunth | Universidad de La Habana, Cuba | Aerial parts (HD) | Safrole (86.9%) | Antileishmanial (promastigotes of L. major, IC50 29.1 μg/mL; L. mexicana, IC50 63.3 μg/mL; L. braziliensis, IC50 52.1 μg/mL; L. donovani, IC50 12.8 μg/mL; amastigotes of L. donovani, IC50 22.3 μg/mL) | [117] |

| P. auritum Kunth | Cali, Valle del Cauca, Colombia | Aerial parts (MWHD) | Safrole (91.3%) | --- | [118] |

| P. auritum Kunth | Topes de Collantes Nature Reserve, Escambray Mountains, Cuba | Leaf (HD) | Camphene (5.5%), safrole (71.8%) | Antioxidant (DPPH radical scavenging assay, IC50 14.8 μg/mL) | [50] |

| P. barbatum Kunth | Amazonas region, Peru | Aerial parts (HD) | Crocatone (10.9%), (E)-asarone (14.1%), apiole (8.0%), 2′-methoxy-4′,5′-methylenedioxy-propiophenone (29.5%) | --- | [119] |

| P. biasperatum Trel. | Monteverde, Costa Rica | Leaf (HD) | β-Elemene (46.4%), germacrene D (9.5%), bicyclogermacrene (14.1%), germacrene A (13.2%) | Cytotoxic (MCF-7 human breast adenocarcinoma) | [34] |

| P. bogotense C. DC. | Ipiales, Nariño, Colombia | Aerial parts (MWHD) | α-Pinene (8.7%), α-phellandrene (13.7%), limonene (5.3%), trans-sabinene hydrate (14.2%) | Antitrypanosomal (T. cruzi epimastigotes, IC50 10.1 μg/mL); cytotoxic (Vero cells, IC50 90.1 μg/mL), Antifungal, broth dilution assay (Trichophyton rubrum, MIC 79 μg/mL; Trichophyton mentagrophytes, MIC 500 μg/mL); cytotoxic (Vero cells, IC50 25.8 μg/mL) | [118,120,121] |

| P. brachypodon (Benth.) C. DC. | Quibdó, Chocó, Colombia | Aerial parts (MWHD) | β-Caryophyllene (20.2%), 9-epi-β-caryophyllene (5.8%), germacrene D (5.9%), bicyclogermacrene (8.1%), spathulenol (5.7%), caryophyllene oxide (10.8%) | --- | [120] |

| P. brachypodon (Benth.) C. DC. | Tutunendo, Chocó, Colombia | Aerial parts (MWHD) | β-Caryophyllene (20.2%), 9-epi-(E)-caryophyllene (5.8%), germacrene D (5.9%), bicyclogermacrene (8.1%), spathulenol (5.7%), caryophyllene oxide (10.8%) | Antiprotozoal (Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigotes, IC50 0.34 μg/mL; Leishmania infantum promastigotes, IC50 23.4 μg/mL); cytotoxic (Vero cells, IC50 30.5 μg/mL; THP-1 human monocytic leukemia, IC50 66.3 μg/mL) | [118] |

| P. brachypodon var. hirsuticaule Yunck. | Samurindó, Chocó, Colombia | Aerial parts (MWHD) | β-Elemene (6.4%), β-caryophyllene (9.8%), α-guaiene (5.9%), germacrene D (16.7%), bicyclogermacrene (6.2%) | Antiprotozoal (Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigotes, IC50 32.5 μg/mL; Leishmania infantum promastigotes, IC50 93.6 μg/mL); cytotoxic (Vero cells, IC50 86.4 μg/mL) | [118] |

| P. bredemeyeri Jacq. | Monteverde, Costa Rica | Leaf (HD) | β-Elemene (34.0%), β-caryophyllene (24.2%), germacrene D (21.7%), bicyclogermacrene (14.1%), germacrene A (11.4%) | Antibacterial, broth dilution assay (Bacillus cereus, MIC 78 μg/mL), enzyme inhibitory (cruzain, IC50 0.96 μg/mL) | [34] |

| P. bredemeyeri Jacq. | Pueblo Bello, Cesar, Colombia | Aerial parts (MWHD) | α-Pinene (20.3%), β-pinene (32.3%), β-caryophyllene (6.3%) | Antifungal, broth dilution assay (Trichophyton rubrum, MIC 157 μg/mL; Trichophyton mentagrophytes, MIC 125 μg/mL); cytotoxic (Vero cells, IC50 15.2 μg/mL) | [121] |

| P. caldense C. DC. | Recife, Pernambuco state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | δ-Cadinene (5.6%), thujopsan-2β-ol (7.4%), α-muurolol (9.0%), α-cadinol (19.0%) | Antibacterial, agar diffusion assay (Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae) | [54] |

| P. caldense C. DC. | Recife, Pernambuco state, Brazil | Root (HD) | Valencene (10.5%), pentadecane (35.7%), selina-3,7(11)-diene (5.4%) | Antibacterial, agar diffusion assay (Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa) | [54] |

| P. caldense C. DC. | Recife, Pernambuco state, Brazil | Stem (HD) | Terpinen-4-ol (18.5%), α-terpineol (15.3%), caryophyllene oxide (6.2%), α-cadinol (9.8%) | Antibacterial, agar diffusion assay (Bacillus subtilis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa) | [54] |

| P. callosum Ruiz & Pav. | Marituba, Pará state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | Safrole (69.2%), methyleugenol (8.6%) | Insecticidal (Solenopsis saevissima, IC50 > 500 μg/mL) | [41] |

| P. callosum Ruiz & Pav. | Barcarena, Pará state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | Safrole (66.0%), methyl eugenol (10.2%) | Enzyme inhibitory (acetylcholinesterase) | [62] |

| P. carniconnectivum C. DC. | Porto Velho, Rondônia state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | β-Pinene (6.3%), caryophyllene oxide (21.3%) | --- | [122] |

| P. carniconnectivum C. DC. | Porto Velho, Rondônia state, Brazil | Stem (HD) | α-Pinene (8.0%), β-pinene (19.0%), spathulenol (23.7%), caryophyllene oxide (7.8%) | --- | [122] |

| P. carpunya Ruiz & Pav. | Cajamarca region, Peru | Leaf (HD) | α-Terpinene (12.1%), p-cymene (10.9%), 1,8-cineole (13.0%), safrole (14.9%), bicyclogermacrene (6.7%), spathulenol (9.8%) | --- | [123] |

| P. carpunya Ruiz & Pav. | Cajamarca region, Peru | Floral (HD) a | α-Pinene (6.2%), α-terpinene (9.8%), p-cymene (7.7%), 1,8-cineole (30.2%), safrole (32.0%) | --- | [123] |

| P. cernuum Vell. | Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (7.2%), β-pinene (6.2%), β-caryophyllene (20.7%), germacrene D (6.7%), bicyclogermacrene (21.9%) | Antimicrobial, agar diffusion assay (Staphylococcus aureus, Candida albicans) | [38] |

| P. cernuum Vell. | São Francisco de Assis Natural Reserve, Blumenau, Santa Catarina state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | trans-Dihydroagarofuran (31.0%), elemol (12.0%), 10-epi-γ-eudesmol (13.0%) | --- | [124] |

| P. cernuum Vell. | Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | β-Elemene (7.2%), β-caryophyllene (22.2%), germacrene D (9.3%), bicyclogermacrene (25.1%), (Z)-α-bisabolene (5.7%), spathulenol (7.2%) | --- | [35,60] |

| P. cernuum Vell. | Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil | Floral (HD) a | α-Copaene (6.5%), β-caryophyllene (9.8%), germacrene D (14.3%), bicyclogermacrene (6.5%), spathulenol (9.7%) | Antifungal, TLC bioautography (Cladosporium cladosporioides, C. sphaerospermum) | [60] |

| P. cernuum Vell. | Reserva da Matinha, Ilhéus, Bahia state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | β-Elemene (11.6%), β-caryophyllene (8.3%), cis-β-guaiene (8.2%), γ-muurolene (7.6%), epi-cubebol (13.1%), spathulenol (9.6%), caryophyllene oxide (7.7%), valeranone (9.1%) | --- | [125] |

| P. cernuum Vell. | Parque Ecológico do Pereque, Cubatão, São Paulo state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | β-Elemene (30.0%), β-caryophyllene (16.3%), germacrene D (12.7%), bicyclogermacrene (19.9%) | Cytotoxic (B16F10-Nex2 murine melanoma, IC50 30 μg/mL; A2058 human melanoma, IC50 24 μg/mL; U87-MG human glioblastoma, IC50 19.1 μg/mL; HeLa human cervical tumor, IC50 23 μg/mL; HL-60 humal myloid leukemia, IC50 16 μg/mL) | [39] |

| P. cernuum Vell. | Parque Ecológico do Pereque, Cubatão, São Paulo state, Brazil | Branches (HD) | Camphene (46.4%), p-cymene (5.8%), linalool (8.7%), α-terpineol (11.6%), carvacrol (11.6%) d | Cytotoxic (B16F10-Nex2 murine melanoma, IC50 39.0 μg/mL; A2058 human melanoma, IC50 24.6 μg/mL; U87-MG human glioblastoma, IC50 19.0 μg/mL; HeLa human cervical tumor, IC50 23.6 μg/mL; HL-60 humal myloid leukemia, IC50 15.5 μg/mL) | [96] |

| P. cernuum Vell. | Ubatuba, São Paulo state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (10.0%), camphene (6.3%), trans-dihydroagarofuran (28.7%), 10-epi-γ-eudesmol (13.5%), 4-epi-cis-dihydroagarofuran (10.8%) | --- | [31] |

| P. cernuum Vell. | Pariquera-Açu, São Paulo state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (11.8%), camphene (8.7%), trans-dihydroagarofuran (33.8%), 10-epi-γ-eudesmol (12.2%) | --- | [31] |

| P. cernuum Vell. | Antonina, Paraná state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (11.4%), β-pinene (7.9%), β-elemene (10.1%), β-caryophyllene (6.9%), spathulenol (11.5%), caryophyllene oxide (5.1%), τ-muurolol (6.2%), α-muurolol (5.8%) | Antileishmanial (L. amazonensis promastigotes, IC50 27.1 μg/mL; L. amazonensis axenic amastigotes, IC50 > 200 μg/mL), anti-Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MIC 125 μg/mL) | [70] |

| P. cernuum Vell. | Blumenau, Santa Catarina state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (2.6–5.4%), β-caryophyllene (5.9–8.7%), 4-epi-cis-dihydroagarofuran (11.2–13.4%), trans-dihydroagarofuran (30.0–36.7%), elemol (5.9–9.2%), γ-eudesmol (8.3–13.3%) | Antibacterial, agar dilution assay (Bacillus subtilis, MIC 48 μg/mL; Staphylococcus aureus, MIC 780 μg/mL; Streptococcus pyogenes, MIC 780 μg/mL); antifungal, agar dilution assay (Microsporum canis, Microsporum gypseum, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, Trichophyton rubrum, Epidermophyton flocosum, Cryptococcus neoformans, MIC 48 μg/mL) | [37] |

| P. cernuum Vell. var. cernuum | Tijuca Forest, Rio de Janeiro state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (10.2%), camphene (5.3%), β-pinene (7.4%), cis-dihydroagarofuran (32.3%), elemol (6.7%) | --- | [36] |

| P. claussenianum (Miq.) C. DC. | São Manoel, Castelo, Espírito Santo, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | Linalool (2.1–5.2%), (E)-nerolidol (81.4–83.3%) | Antileishmanial (promastigotes of L. amazonensis, IC50 30.24 μg/mL) Anticandidal (C. albicans, MIC 0.2–1.26%) | [71,126] |

| P. claussenianum (Miq.) C. DC. | São Manoel, Castelo, Espírito Santo, Brazil | Floral (HD) a | Linalool (50.2–54.5%), (E)-nerolidol (22.7–24.3%) | Antileishmanial (promastigotes of L. amazonensis, IC50 1328 μg/mL) Anticandidal (C. albicans, MIC 0.04–0.1%) Antiparasitic (Plasmodium falciparum W2, IC50 7.9 μg/mL) | [71,73,126] |

| P. corcovadense (Miq.) C. DC. | Jardim Botânico de Recife, Pernambuco, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (5.9%), terpinolene (17.4%), 4-butyl-1,2-methylenedioxybenzene (30.6%), β-caryophyllene (6.3%) | Mosquito larvicidal activity (Aedes aegypti, LC50 30.5 μg/mL) | [127] |

| P. corrugatum Kuntze | Valle de Anton, Cerro Caracoral, Cocle, Panama | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (12.2%), β-pinene (26.6%), limonene (8.2%), p-cymene (8.6%), 1,8-cineole (5.9%), (E)-nerolidol (12.8%), caryophyllene oxide (8.5%) | --- | [47] |

| P. crassinervium Kunth | Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | β-Caryophyllene (8.1%), germacrene D (14.0%), bicyclogermacrene (9.2%), epi-α-selinene (5.0%), (E)-nerolidol (8.2%), spathulenol (9.8%), guiaol (5.8%), β-eudesmol (10.1%) | Antifungal, TLC bioautography (Cladosporium cladosporioides, Cladosporium sphaerospermum) | [35,60] |

| P. crassinervium Kunth | Mococa, São Paulo state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (11.5%), β-pinene (11.6%), β-caryophyllene (7.8%), germacrene D (9.2%), bicyclogermacrene (5.1%), guaiol (5.5%) | --- | [31] |

| P. curtispicum C. DC. | Altos de Campana, Panama | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (19.4%), limonene (8.1%), β-caryophyllene (13.9%) | --- | [47] |

| P. cyrtopodon C. DC. | Marituba, Pará state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | α-Cubebene (5.1%), β-caryophyllene (19.2%), germacrene D (10.0%), bicyclogermacrene (13.0%), spathulenol (8.4%) | --- | [128] |

| P. cyrtopodon C. DC. | Santarém, Pará state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | p-Cymene (6.3%), germacrene D (17.9%), bicyclogermacrene (23.3%), (E)-nerolidol (6.6%), spathulenol (6.9%) | --- | [128] |

| P. cyrtopodon C. DC. | Ananindeua, Pará state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | α-Pinene (7.5%), β-pinene (6.0%), β-caryophyllene (34.6%), germacrene D (13.6%), bicyclogermacrene (21.4%), spathulenol (8.4%) | --- | [128] |

| P. cyrtopodon C. DC. | Ananindeua, Pará state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | β-Caryophyllene (18.8%), germacrene D (14.8%), bicyclogermacrene (14.0%), germacrene B (26.8%) | --- | [128] |

| P. cyrtopodon C. DC. | Bujaru, Pará state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | α-Cubebene (6.7%), β-caryophyllene (18.1%), germacrene D (13.6%), bicyclogermacrene (14.9%), germacrene B (10.1%) | --- | [128] |

| P. cyrtopodon C. DC. | Manaus, Amazonas state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | Germacrene D (7.5%), bicyclogermacrene (8.3%), α-cadinol (9.5%), epi-α-bisabolol (26.3%) | --- | [128] |

| P. dactylostigmum Yunck. | Itacoatiara, Amazonas State, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | β-Caryophyllene (8.9%), γ-muurolene (5.9%), β-selinene (9.0%), α-selinene (8.0%), caryophyllene oxide (6.0%), τ-muurolol (7.5%), α-cadinol (21.7%) | --- | [129] |

| P. darienense C. DC. | Parque Nacional Chagres, Panama | Leaf (HD) | Limonene (6.3%), (E)-β-farnesene (63.7%) | --- | [47] |

| P. demeraranum (Miq.) C. DC. | Belém, Pará state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | α-Pinene (7.3%), sabinene (12.9%), β-pinene (7.7%), limonene (20.2%) | --- | [130] |

| P. demeraranum (Miq.) C. DC. | Ananindeua, Pará state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | α-Pinene (6.1–12.3%), sabinene (17.0–22.7%), β-pinene (8.2–14.4%), limonene (30.6–40.3%) | --- | [130] |

| P. demeraranum (Miq.) C. DC. | Adolpho Ducke Reserve, Manaus, Amazonas state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | β-Pinene (6.7%), limonene (19.3%), β-elemene (33.1%), β-caryophyllene (6.0%), germacrene D (5.2%), β-selinene (5.0%), bicyclogermacrene (8.8%) | Antileishmanial (L. amazonensis promastigotes, IC50 86.0 μg/mL; L. amazonensis amastigotes, IC50 78.0 μg/mL; L. guyanensis promastigotes, IC50 22.7 μg/mL) | [72] |

| P. dilatatum Rich. | Fazenda Sucupira, Embrapa, Brasília, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | (E)-β-Ocimene (19.7%), β-caryophyllene (11.4%), germacrene D (8.9%), bicyclogermacrene (8.8%), spathulenol (6.5%), caryophyllene oxide (5.3%) | --- | [33] |

| P. dilatatum Rich. | Alto Alegre, Roraima state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | β-Caryophyllene (11.7%), germacrene D (6.7%), α-selinene (6.1%), δ-cadinene (5.4%), caryophyllene oxide (6.1%), α-cadinol (12.2%) | --- | [131] |

| P. dilatatum Rich. | Alto Alegre, Roraima state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | β-Caryophyllene (15.5%), germacrene D (10.2%), α-selinene (6.9%), δ-cadinene (8.5%), hinesol (6.4%), α-cadinol (7.0%) | --- | [131] |

| P. dilatatum Rich. | Benfica, Pará state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | Germacrene D (12.6%), bicyclogermacrene (7.4%), (E)-nerolidol (10.2%), spathulenol (11.8%), hinesol (6.4%), α-cadinol (5.8%) | --- | [131] |

| P. dilatatum Rich. | Belterra, Pará state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | α-Pinene (9.7%), β-pinene (14.8%), (Z)-β-ocimene (10.0%), β-caryophyllene (7.4%), bicyclogermacrene (27.6%), spathulenol (15.0%) | --- | [131] |

| P. dilatatum Rich. | Marituba, Pará state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | p-Cymene (11.7%), β-selinene (6.4%), curzerene (13.8%), (E)-nerolidol (5.7%), α-eudesmol (8.0%), atractylone (5.1%) | --- | [131] |

| P. dilatatum Rich. | Marituba, Pará state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | Germacrene D (30.2%), bicyclogermacrene (9.4%), spathulenol (40.6%), hinesol (6.4%), α-cadinol (5.8%) | --- | [131] |

| P. dilatatum Rich. | Serra dos Carajás, Pará state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | p-Cymene (5.1%), β-elemene (21.8%), β-caryophyllene (5.1%), germacrene D (18.5%) | --- | [131] |

| P. dilatatum Rich. | Serra dos Carajás, Pará state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | β-Pinene (10.5%), limonene (6.4%), δ-elemene (7.6%), β-elemene (13.8%), bicyclogermacrene (7.9%), spathulenol (9.3%) | --- | [131] |

| P. dilatatum Rich. | Angico, Tocantins state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | (Z)-β-Farnesene (7.0%), germacrene D (24.5%), bicyclogermacrene (6.7%), β-bisabolene (8.1%), (Z)-α-bisabolene (39.3%) | --- | [131] |

| P. dilatatum Rich. | Xambioá, Tocantins state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | Germacrene D (8.5%), bicyclogermacrene (34.7%), spathulenol (35.2%) | --- | [131] |

| P. dilatatum Rich. | Xambioá, Tocantins state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | Germacrene D (15.2%), curzerene (28.7%), β-bisabolene (5.5%), (Z)-α-bisabolene (23.2%) | --- | [131] |

| P. dilatatum Rich. | Carolina, Maranhão state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | Limonene (19.4%), germacrene D (43.0%), bicyclogermacrene (13.2%) | --- | [131] |

| P. diospyrifolium Kunth | Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | (E)-Nerolidol (18.2%), spathulenol (25.4%), caryophyllene oxide (7.7%), globulol (6.6%), humulene epoxide II (6.9%) | --- | [35,60] |

| P. diospyrifolium Kunth | Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil | Floral (HD) a | α-Copaene (47.7%), β-caryophyllene (12.3%), α-humulene (5.7%) | --- | [60] |

| P. diospyrifolium Kunth | Maringá, Parana state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | Limonene (8.5%), (E)-β-ocimene (5.8%), β-caryophyllene (16.8%), γ-muurolene (10.6%), cis-eudesma-6,11-diene (21.1%), germacrene B (6.2%) | Antifungal, agar diffusion assay (Candida albicans, Candida parapsilosis, Candida tropicalis) | [55] |

| P. diospyrifolium Kunth | Antonina, Paraná state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (6.7%), limonene (6.7%), α-copaene (5.4%), β-caryophyllene (7.4%), γ-gurjunene (6.9%), germacrene B (6.7%), selin-11-en-4α-ol (17.7%) | Antileishmanial (L. amazonensis promastigotes, IC50 13.5 μg/mL; L. amazonensis axenic amastigotes, IC50 76.1 μg/mL; anti-Mycobacterium tuberculosis, MIC 125 μg/mL) | [70] |

| P. divaricatum G. Mey. | Guaramiranga Mountain, Ceará state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (9.0–18.8%), β-pinene (19.9–25.3%), 1,8-cineole (8.9–9.6%), linalool (23.4–29.7%), germacrene D (6.3–6.5%) | --- | [132] |

| P. divaricatum G. Mey. | Guaramiranga Mountain, Ceará state, Brazil | Floral (HD) a | α-Pinene (6.3–17.6%), β-pinene (12.0–18.0%), α-phellandrene (4.6–10.0%), 1,8-cineole (0.7–12.0%), linalool (3.3–8.3%), β-caryophyllene (9.0–11.4%), germacrene D (0.9–6.1%), bicyclogermacrene (5.3–6.9%) | --- | [132] |

| P. divaricatum G. Mey. | Marajó Island, Breves, Pará state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | Eugenol (23.6%), methyleugenol (63.8%) | Antifungal (Cladosporium cladosporioides, MIC 0.5 μg/mL; Cladosporium sphaerospermum, 5.0 μg/mL); antioxidant (DPPH radical scavenging assay, IC50 16.2 μg/mL) | [40] |

| P. divaricatum G. Mey. | Breves, Pará state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | Eugenol (16.2%), methyleugenol (69.2%) | Insecticidal (Solenopsis saevissima, IC50 453 μg/mL) | [41] |

| P. divaricatum G. Mey. | Itabuna, Bahia state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | Safrole (98.0%) | Antibacterial (Listeria monocytogenes, MIC 156 μg/mL) | [44] |

| P. divaricatum G. Mey. | Rovira, Tolima, Colombia | Aerial parts (MWHD) | α-Pinene (11.4%), β-pinene (5.1%), α-phellandrene (6.1%), 1,8-cineole (18.3%), linalool (15.0%), β-caryophyllene (8.2%) | Antiprotozoal (Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigotes, IC50 13.1 μg/mL; Leishmania infantum promastigotes, IC50 73.3 μg/mL); cytotoxic (Vero cells, IC50 89.8 μg/mL) Antifungal, broth dilution assay (Trichophyton rubrum, MIC 397 μg/mL; Trichophyton mentagrophytes, MIC 500 μg/mL); cytotoxic (Vero cells, IC50 200 μg/mL) | [118,121] |

| P. divaricatum G. Mey. | Marajó Island, Breves, Pará state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | Eugenol (7.9%), methyleugenol (77.1%) | Antifungal (Fusarium solani f. sp. piperis, IC50 698 μg/mL) | [42] |

| P. divaricatum G. Mey. | Breves, Pará state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | Methyleugenol (80.6–93.3%) | --- | [43] |

| P. dolichotrichum Yunck. | Quibdó, Chocó, Colombia | Aerial parts (MWHD) | β-Elemene (6.4%), β-caryophyllene (9.8%), germacrene D (16.7%), bicyclogermacrene (6.2%), α-guaiene (5.9%) | --- | [120] |

| P. dotanum Trel. | Monteverde, Costa Rica | Leaf (HD) | α-Thujene (5.2%), sabinene (50.4%), germacrene D (15.3%), bicyclogermacrene (7.4%) | --- | [34] |

| P. duckei C. DC. | Adolpho Ducke Reserve, Manaus, Amazonas state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | 1,8-Cineole (5.8%), β-caryophyllene (27.1%), germacrene D (14.7%), bicyclogermacrene (5.2%), γ-eudesmol (17.9%) | Antileishmanial (L. amazonensis promastigotes, IC50 46.0 μg/mL; L. amazonensis amastigotes, IC50 42.4 μg/mL; L. guyanensis promastigotes, IC50 15.2 μg/mL) | [72] |

| P. dumosum Rudge | Porto Velho, Rondônia state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (12.1%), β-pinene (16.0%), α-phellandrene (5.2%), β-caryophyllene (15.9%), aromadendrene (6.9%), bicyclogermacrene (16.2%) | --- | [105] |

| P. eriopodon (Miq.) C. DC. | Pueblo Bello, Cesar, Colombia | Aerial parts (MWHD) | β-Caryophyllene (8.1%), β-selinene (5.0%), dillapiole (38.8%) | Antifungal, broth dilution assay (Trichophyton mentagrophytes, MIC 500 μg/mL); cytotoxic (Vero cells, IC50 15.8 μg/mL) | [121] |

| P. fimbriulatum C. DC. | Altos de Campana National Park, Panama | Leaf (HD) | Linalool (5.3%), linalyl acetate (5.3%), β-caryophyllene (11.3%), germacrene D (12.8%) | --- | [111] |

| P. fimbriulatum C. DC. | Monteverde, Costa Rica | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (10.2%), δ-elemene (9.4%), germacrene D (32.9%), bicyclogermacrene (8.1%) | Antibacterial (Bacillus cereus, MIC 39 μg/mL) | [34] |

| P. friedrichsthalii C. DC. | Pacayas, Cartago, Costa Rica | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (14.7%), camphene (5.2%), germacrene D (7.1%) | --- | [133] |

| P. friedrichsthalii C. DC. | Pacayas, Cartago, Costa Rica | Floral (HD) a | α-Pinene (13.4%), β-phellandrene (5.2%), trans-p-menth-2-en-1-ol (7.0%), cis-p-menth-2-en-1-ol (5.1%) | --- | [133] |

| P. friedrichsthalii C. DC. | Fortuma, Quebrada Honda, Chiriqui, Panama | Leaf (HD) | Germacrene D (9.6%), α-selinene (12.0%), β-selinene (7.9%), selin-11-en-4α-ol (12.8%) | --- | [133] |

| P. gaudichaudianum Kunth | Sapiranga, Rio Grande do Sul state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | β-Pinene (5.6%), β-caryophyllene (17.4%), α-humulene (37.5%), allo-aromadendrene (7.7%) | --- | [134] |

| P. gaudichaudianum Kunth | Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | β-Caryophyllene (12.1%), α-humulene (13.3%), β-selinene (15.7%), α-selinene (16.6%) | --- | [135] |

| P. gaudichaudianum Kunth | Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | β-Caryophyllene (19.3%), α-humulene (29.2%), α-selinene (8.9%) | --- | [135] |

| P. gaudichaudianum Kunth | State of Rondônia, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | Aromadendrene (15.6%), ishwarane (10.0%), β-selinene (10.5%), viridiflorol (27.5%), selin-11-en-4α-ol (8.5%) | Mosquito larvicidal (Aedes aegypti, LC50 121 μg/mL) | [136] |

| P. gaudichaudianum Kunth | Riozinho, Rio Grande do Sul state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | β-Caryophyllene (8.9%), α-humulene (16.5%), bicyclogermacrene (7.4%), (E)-nerolidol (22.4%) | Cytotoxic (V79 Chinese hamster lung cells, IC50 4.0 μg/mL) | [137] |

| P. gaudichaudianum Kunth | Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | β-Caryophyllene (15.6%), α-humulene (23.4%), β-selinene (6.6%), viridiflorene (8.1%), hinesol (6.4%), α-cadinol (7.0%) | Antifungal, broth dilution assay (Candida krusei, MIC 31.25 μg/mL) | [35] |

| P. gaudichaudianum Kunth | Riozinho, Rio Grande do Sul state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | β-Caryophyllene (7.5%), α-humulene (21.3%), bicyclogermacrene (13.2%), (E)-nerolidol (22.1%) | Not mutagenic (Saccharomyces cerevisiae); EO and nerolidol generate reactive oxygen species | [138] |

| P. gaudichaudianum Kunth | Pariquera-Açu, São Paulo state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (12.2%), β-pinene (7.0%), β-caryophyllene (8.5%), trans-β-guaiene (6.9%), (E)-nerolidol (17.5%), caryophyllene oxide (8.5%) | --- | [31] |

| P. gaudichaudianum Kunth | Antonina, Paraná state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | δ-3-Carene (5.9%), γ-elemene (5.4%), δ-cadinene (45.3%) | Antileishmanial (L. amazonensis promastigotes, IC50 93.5 μg/mL) | [70] |

| P. glabratum Kunth | Reserva da Matinha, Ilhéus, Bahia state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | (Z)-Caryophyllene (5.2%), β-caryophyllene (14.6%), δ-cadinene (6.3%), (E)-nerolidol (5.3%), longiborneol (12.0%) | --- | [125] |

| P. glabrescens (Miq.) C. DC. | Monteverde, Costa Rica | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (26.0%), limonene (56.6%) | Cytotoxic (MCF-7 human breast adenocarcinoma) | [34] |

| P. grande Vahl | Parque Nacional Camino de Cruces, Panama | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (6.3%), β-pinene (14.5%), γ-terpinene (8.0%), p-cymene (43.9%) | --- | [47] |

| P. heterophyllum Ruiz & Pav. | Estancia, Bolivia | Leaf (SD) | α-Pinene (9.3%), β-pinene (6.2%), 1,8-cineole (39.0%), (E)-β-ocimene (6.5%), asaricin (8.8%) | --- | [101] |

| P. hispidinervum C. DC. | Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | Terpinolene (5.4%), safrole (85.1%) | Amebicidal (Acanthamoeba polyphaga trophozoites, LC50 66 μg/mL) | [139] |

| P. hispidum Sw. | Rondônia state, Brazil | Leaf (SD) | α-Pinene (5.2%), camphene (15.6%), β-phellandrene (9.7%), β-caryophyllene (5.4%), α-guaiene (11.5%), γ-cadinene (25.1%), γ-elemene (10.9%) c | --- | [112] |

| P. hispidum Sw. | Pinar del Río, Cuba | Leaf (HD) | Curzerene (12.9%), elemol (7.6%), γ-eudesmol (9.3%), β-eudesmol (17.5%), α-eudesmol (8.1%), 14-Hydroxy-α-muurolene (5.0%) | --- | [46] |

| P. hispidum Sw. | Fazenda Sucupira, Embrapa, Brasília, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (9.0%), β-pinene (19.7%), δ-3-carene (7.4%), spathulenol (6.2%), α-cadinol (6.9%) | --- | [33] |

| P. hispidum Sw. | Pacurita, Chocó, Colombia | Leaf (HD) | β-Elemene (5.1%), β-caryophyllene (5.1%), (E)-nerolidol (23.6%), caryophyllene oxide (5.4%) | --- | [48] |

| P. hispidum Sw. | Fênix, Paraná state, Brazil | Floral (HD) a | α-Pinene (7.1–13.9%), β-pinene (7.5–13.3%), α-copaene (28.7–36.2%) | --- | [108] |

| P. hispidum Sw. | Chiguará, Mérida state, Venezuela | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (15.3%), β-pinene (14.8%), δ-3-carene (6.9%), β-elemene (8.1%), β-caryophyllene (6.2%), germacrene B (5.2%), spathulenol (5.0%), caryophyllene oxide (7.8%) | Antibacterial (Bacillus subtilis, MIC 12.5 μg/mL; Bacillus cereus, MIC 12.5 μg/mL; Staphylococcus aureus, MIC 12.5 μg/mL; Staphylococcus epidermidis, MIC 12.5 μg/mL; Staphylococcus saprophyticus, MIC 12.5 μg/mL; Enterococcus faecalis, MIC 15.0 μg/mL), antifungal (Candida albicans, MIC 200 μg/mL), cytotoxic (HeLa human cervical carcinoma, IC50 36.6 μg/mL; A-549 human lung carcinoma, IC50 37.5 μg/mL; MCF-7 human breast adenocarcinoma, IC50 34.2 μg/mL) | [97] |

| P. hispidum Sw. | Reserva da Matinha, Ilhéus, Bahia state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (6.6%), β-pinene (12.0%), khusimene (12.1%), γ-cadinene (13.2%), δ-cadinene (6.3%), ledol (8.8%) | --- | [125] |

| P. hispidum Sw. | Carajás National Forest, Parauapebas, Pará state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | δ-3-Carene (9.1%), limonene (6.9%), α-copaene (7.3%), β-caryophyllene (10.5%), α-humulene (9.5%), β-selinene (5.1%), caryophyllene oxide (5.9%) | Antifungal, TLC bioautography (Cladosporium cladosporioides, Cladosporium sphaerospermum); enzyme inhibitory, TLC bioautography (acetylcholinesterase) | [61] |

| P. hispidum Sw. | Atrato, Chocó, Colombia | Aerial parts (MWHD) | β-Elemene (5.1%), β-caryophyllene (5.1%), (E)-nerolidol (23.6%), caryophyllene oxide (5.4%) | Antifungal, broth dilution assay (Fusarium oxysporum, MIC 500 μg/mL; Trichophyton rubrum, MIC 99 μg/mL; Trichophyton mentagrophytes, MIC 125 μg/mL); cytotoxic (Vero cells, IC50 51.7 μg/mL) | [121] |

| P. hispidum Sw. | Altos de Campana, Panama | Leaf (HD) | Piperitone (10.0%), dillapiole (57.7%) | Mosquito larvicidal (Aedes aegypti, LC100 250 μg/mL) | [47] |

| P. hostmannianum (Miq.) C. DC. | State of Rondônia, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | Piperitone (5.6%), germacrene D (6.8%), asaricin (27.4%), myristicin (20.3%), dillapiole (7.7%) | Mosquito larvicidal (Aedes aegypti, LC50 54 μg/mL) | [136] |

| P. humaytanum Yunck. | State of Rondônia, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | β-Selinene (15.8%), sesquicineole (5.0%), spathulenol (6.3%), caryophyllene oxide (16.6%), β-oplopenone (6.0%) | Mosquito larvicidal (Aedes aegypti, LC50 156 μg/mL) | [136] |

| P. ilheusense Yunck. | Ilheus, Bahia, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | β-Caryophyllene (11.8%), γ-cadinene (6.9%), germacrene B (7.2%), gleenol (7.5%), patchouli alcohol (11.1%) | Antimicrobial, agar diffusion assay (Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus, Candida albicans, Candida crusei, Candida parapsilosis) | [57] |

| P. imperiale (Miq.) C. DC. | Monteverde, Costa Rica | Leaf (HD) | β-Elemene (5.2%), β-caryophyllene (25.5%), α-guaiene (7.6%), germacrene D (5.5%), bicyclogermacrene (19.7%), germacrene A (8.5%), α-bulnesene (10.8%), dillapiole (6.7%) | Antibacterial (Bacillus cereus, MIC 156 μg/mL), cytotoxic (MCF-7 human breast adenocarcinoma) | [34] |

| P. jacquemontianum Kunth | Lachuá, Alta Verapaz, Guatemala | Leaf (HD) | Linalool (69.4%), (E)-nerolidol (8.0%) | --- | [140] |

| P. jacquemontianum Kunth | Parque Nacional Soberania, Panama | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (9.6%), β-pinene (10.1%), α-phellandrene (13.8%), limonene (12.2%), p-cymene (7.4%), linalool (14.5%) | --- | [47] |

| P. klotzschianum (Kunth) C. DC. | Vila do Riacho, Gimuna Forest, Aracruz, Espírito Santo, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | 4-Butyl-1,2-methylenedioxybenzene (81.0%), γ-asarone (9.1%) | --- | [141] |

| P. klotzschianum (Kunth) C. DC. | Vila do Riacho, Gimuna Forest, Aracruz, Espírito Santo, Brazil | Root (HD) | 4-Butyl-1,2-methylenedioxybenzene (96.2%) | Mosquito larvicidal activity (Aedes aegypti, LC50 10.0 μg/mL) | [141] |

| P. klotzschianum (Kunth) C. DC. | Vila do Riacho, Gimuna Forest, Aracruz, Espírito Santo, Brazil | Seed (HD) | α-Phellandrene (17.0%), p-cymene (7.4%), limonene (17.8%), 4-Butyl-1,2-methylenedioxybenzene (36.9%), α-trans-bergamotene (8.8%) | Mosquito larvicidal activity (Aedes aegypti, LC50 13.3 μg/mL) | [141] |

| P. klotzschianum (Kunth) C. DC. | Vila do Riacho, Gimuna Forest, Aracruz, Espírito Santo, Brazil | Stem (HD) | 4-Butyl-1,2-methylenedioxybenzene (84.8%), γ-asarone (5.4%) | --- | [141] |

| P. krukoffii Yunck. | Carajás National Forest, Parauapebas, Pará state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | β-Elemene (1.7–8.2%), myristicin (26.7–40.6%), τ-muurolol (0.2–5.7%), apiole (25.3–34.1%) | --- | [142] |

| P. lanceifolium Kunth | San Isidro del Tejar, Costa Rica | Leaf (HD) | β-Caryophyllene (20.6%), germacrene D (12.5%), elemicin (24.4%), apiole (11.7%) | --- | [143] |

| P. lanceifolium Kunth | San Isidro del Tejar, Costa Rica | Floral (HD) a | α-Pinene (13.7%), β-pinene (15.8%), γ-terpinene (6.9%), β-caryophyllene (5.1%), elemicin (16.4%), apiole (9.8%) | --- | [143] |

| P. lanceifolium Kunth | Monteverde, Costa Rica | Leaf (HD) | Dillapiole (74.6%) | --- | [34] |

| P. lanceifolium Kunth | Bagadó, Chocó, Colombia | Aerial parts (MWHD) | β-Pinene (5.4%), β-caryophyllene (11.6%), germacrene D (10.7%), β-selinene (7.8%), δ-cadinene (6.1%), caryophyllene oxide (5.9%) | Antiprotozoal (Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigotes, IC50 7.48 μg/mL; Leishmania infantum promastigotes, IC50 37.8 μg/mL); cytotoxic (Vero cells, IC50 46.0 μg/mL; THP-1 human monocytic leukemia, IC50 55.7 μg/mL) | [118] |

| P. leptorum Kunth | Monte Alegre do Sul, São Paulo state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | Seychellene (34.7%), caryophyllene oxide (12.5%) | --- | [31] |

| P. longispicum C. DC. | Altos de Campana, Panama | Leaf (HD) | β-Caryophyllene (45.2%), caryophyllene oxide (5.5%) | Mosquito larvicidal (Aedes aegypti, LC100 250 μg/mL) | [47] |

| P. lucaeanum var. grandifolium Yunck. | Rio de Janeiro state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (30.0%), β-caryophyllene (5.0%), α-zingiberene (30.4%), β-bisabolene (8.9%), β-sesquiphellandrene (11.1%) | Antiparasitic (Plasmodium falciparum W2, IC50 2.65 μg/mL) | [73] |

| P. madeiranum Yunck. | Reserva da Matinha, Ilhéus, Bahia state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | β-Caryophyllene (11.2%), germacrene D-4-ol (11.1%), 1,10-di-epi-cubenol (7.0%), α-bisabolol (7.1%), epi-α-bisabolol (5.4%) | --- | [125] |

| P. malacophyllum (C. Presl) C. DC. | Florianópolis, Santa Catarina, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (5.0%), camphene (30.8%), camphor (32.8%) | Antibacterial (Staphylococcus aureus, MIC 3700 μg/mL; Bacillus cereus, MIC 1850 μg/mL; Acinetobacter baumanii, MIC 3700 μg/mL; Escherichia coli, MIC 1850 μg/mL; Pseudomonas aeruginosa, MIC 3700 μg/mL); antifungal (Epidermophyton flocosum, MIC 1000 μg/mL; Microsporum gypseum, MIC 1000 μg/mL; Trichophyton mentagrophytes, MIC 500 μg/mL; Trichophyton rubrum, MIC 1000 μg/mL; Candida albicans, MIC 1000 μg/mL; Cryptococcus neoformans, MIC 500 μg/mL); antiparasitic (Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigotes, IC50 312 μg/mL) | [56] |

| P. manausense Yunck. | Ananindeua, Pará state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | α-Pinene (5.2–6.6%), β-pinene (4.7–6.5%), β-caryophyllene (7.7–8.5%), germacrene D (3.5–6.1%), bicyclogermacrene (32.0–34.0%), δ-cadinene (5.8–7.0%), gleenol (6.8–9.4%) | --- | [144] |

| P. manausense Yunck. | Acará, Pará state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | α-Pinene (9.1%), β-pinene (9.2%), β-caryophyllene (5.9%), bicyclogermacrene (41.0%), δ-cadinene (5.8%) | --- | [144] |

| P. manausense Yunck. | Marituba, Pará state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | β-Caryophyllene (6.0%), aromadendrene (5.0%), bicyclogermacrene (7.8%), spathulenol (15.0%), globulol (9.4%), α-muurolol (7.6%) | --- | [144] |

| P. marginatum Jacq. | Itacoatiara, Amazonas State, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | (E)-β-Ocimene (5.2%), α-copaene (5.6%), β-caryophyllene (9.1%), γ-elemene (8.5%), propiopiperone (18.2%) | --- | [145] |

| P. marginatum Jacq. | Itacoatiara, Amazonas State, Brazil | Stem (HD) | δ-3-Carene (6.9%), β-caryophyllene (11.6%), myristicin (19.3%), propiopiperone (18.6%) | --- | [145] |

| P. marginatum Jacq. | Monteverde, Costa Rica | Aerial parts (HD) | p-Cymene (7.1%), estragole (6.6%), p-anisaldehyde (22.0%), (E)-anethole (45.9%), anisyl methyl ketone (14.2%) | --- | [49] |

| P. marginatum Jacq. | Cultivated (State University of Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil) | Leaf (HD) | --- | Antibacterial (Escherichia coli, MIC 700 μg/mL) | [52] |

| P. marginatum Jacq. | Monte Alegre, Pará state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | (E)-β-Ocimene (5.6%), safrole (63.9%), methyleugenol (5.9%), propiopiperone (7.3%) | --- | [45] |

| P. marginatum Jacq. | Xambioá, Tocantins state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | Safrole (52.3–52.5%), myristicin (6.3–9.3%), propiopiperone (11.8–14.1%) | --- | [45] |

| P. marginatum Jacq. | Nazaré, Tocantins state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | Safrole (41.1%), myristicin (8.2%), propiopiperone (30.4%) | --- | [45] |

| P. marginatum Jacq. | Monte Alegre, Pará state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | (Z)-β-Ocimene (5.3%), (E)-β-ocimene (13.5%), safrole (23.9%), β-caryophyllene (6.0%), propiopiperone (33.2%) | --- | [45] |

| P. marginatum Jacq. | Belém, Pará state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | p-Mentha-1(7),8-diene (39.0%), (E)-β-ocimene (9.8%), propiopiperone (19.0%) | --- | [45] |

| P. marginatum Jacq. | Alter do Chão, Pará state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (5.0%), p-mentha-1(7),8-diene (34.8%), (E)-β-ocimene (8.7%), propiopiperone (23.1%), elemicin (6.5%) | --- | [45] |

| P. marginatum Jacq. | Belterra, Pará state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | p-Mentha-1(7),8-diene (22.9%), (E)-β-ocimene (8.2%), propiopiperone (40.7%) | --- | [45] |

| P. marginatum Jacq. | Melgaço, Pará state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | (E)-β-Ocimene (8.0%), safrole (10.4%), germacrene D (8.1%), bicyclogermacrene (6.4%), myristicin (16.0%), propiopiperone (17.4%) | --- | [45] |

| P. marginatum Jacq. | Xinguara, Pará state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | (Z)-β-Ocimene (8.6%), (E)-β-ocimene (15.2%), germacrene D (10.4%), myristicin (5.4%), propiopiperone (14.5%), τ-muurolol (5.0%) | --- | [45] |

| P. marginatum Jacq. | Manaus, Amazonas state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | Safrole (6.4%), α-copaene (7.4%), β-caryophyllene (9.5%), germacrene D (5.5%), propiopiperone (25.0%) | --- | [45] |

| P. marginatum Jacq. | Macapá, Amapá state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | (E)-β-Ocimene (5.5%), β-caryophyllene (10.6%), myristicin (9.6%), propiopiperone (22.9%) | --- | [45] |

| P. marginatum Jacq. | Monte Alegre, Pará state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | (Z)-β-Ocimene (5.7%), (E)-β-ocimene (13.5%), β-caryophyllene (9.3%), propiopiperone (40.2%) | --- | [45] |

| P. marginatum Jacq. | Viseu, Pará state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | γ-Terpinene (14.4%), myristicin (5.0%), propiopiperone (29.6%), spathulenol (6.6%) | --- | [45] |

| P. marginatum Jacq. | Alta Floresta, Mato Grosso state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | γ-Terpinene (8.6%), myristicin (5.5%), propiopiperone (18.4%) | --- | [45] |

| P. marginatum Jacq. | Manaus, Amazonas state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | γ-Terpinene (6.5%), safrole (5.7%), β-caryophyllene (13.3%), germacrene D (8.7%), propiopiperone (7.9%) | --- | [45] |

| P. marginatum Jacq. | Manaus, Amazonas state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | (Z)-β-Ocimene (5.2%), (E)-β-ocimene (8.7%), α-copaene (11.4%), β-caryophyllene (10.2%), germacrene D (7.6%), bicyclogermacrene (8.2%), propiopiperone (10.4%) | --- | [45] |

| P. marginatum Jacq. | Salvaterra, Pará state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | p-Mentha-1(7),8-diene (5.2%), (Z)-anethole (8.4%), (E)-anethole (16.5%), isoosmorhizole (17.4%), (E)-isoosmorhizole (29.1%) | --- | [45] |

| P. marginatum Jacq. | Manaus, Amazonas state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | (Z)-Anethole (6.0%), (E)-anethole (26.4%), isoosmorhizole (11.2%), (E)-isoosmorhizole (32.2%) | --- | [45] |

| P. marginatum Jacq. | Óbidos, Pará state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | (E)-Anethole (13.6%), isoosmorhizole (24.5%), (E)-isoosmorhizole (46.8%) | --- | [45] |

| P. marginatum Jacq. | Medicilândia, Pará state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | β-Caryophyllene (6.7%), (E)-isoosmorhizole (15.8%), crocatone (21.9%), 2′-methoxy-4′,5′-methylenedioxypropiophenone (26.3%) | --- | [45] |

| P. marginatum Jacq. | Paredão, Roraima state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | β-Caryophyllene (13.6%), bicyclogermacrene (11.7%), (Z)-asarone (8.8%), exalatacin (7.9%), (E)-asarone (10.8%) | --- | [45] |

| P. marginatum Jacq. | Venadillo, Tolima, Colombia | Aerial parts (HD) | α-Phellandrene (11.1%), limonene (7.5%), β-caryophyllene (11.0%), elemicin (18.0%), isoelemicin (9.2%) | --- | [120] |

| P. marginatum Jacq. | Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco, Recife, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | β-Caryophyllene (7.5%), α-acoradiene (5.1%), bicyclogermacrene (9.4%), elemol (9.7%), (Z)-asarone (30.4%), patchouli alcohol (16.0%), (E)-asarone (6.4%) | Mosquito larvicidal (Aedes aegypti, LC50 23.8 μg/mL) | [146] |

| P. marginatum Jacq. | Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco, Recife, Brazil | Floral (HD) a | α-Copaene (9.4%), β-caryophyllene (13.1%), α-acoradiene (9.7%), patchouli alcohol (23.4%), (E)-asarone (22.1%) | Mosquito larvicidal (Aedes aegypti, LC50 19.9 μg/mL) | [146] |

| P. marginatum Jacq. | Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco, Recife, Brazil | Stem (HD) | β-Caryophyllene (6.8%), seychellene (5.8%), elemicin (6.9%), (Z)-asarone (8.5%), patchouli alcohol (25.7%), (E)-asarone (32.6%) | Mosquito larvicidal (Aedes aegypti, LC50 19.9 μg/mL) | [146] |

| P. marginatum Jacq. | Belém, Pará state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | p-Mentha-1(7),8-diene (39.0%), (E)-β-ocimene (9.8%), propiopiperone (19.0%) | Insecticidal (Solenopsis saevissima, IC50 240 μg/mL) | [41] |

| P. marginatum Jacq. | Manaus, Amazonas state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | (E)-Anethole (26.4%), isoosmorhizole (11.2%), (E)-isoosmorhizole (32.2%) | Insecticidal (Solenopsis saevissima, IC50 439 μg/mL) | [41] |

| P. marginatum Jacq. | Venadillo, Tolima, Colombia | Aerial parts (MWHD) | α-Phellandrene (11.2%), limonene (7.6%), β-caryophyllene (11.1%), elemicin (18.4%), isoelemicin (9.3%) | Antiprotozoal (Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigotes, IC50 16.2 μg/mL; Leishmania infantum promastigotes, IC50 88.7 μg/mL); cytotoxic (Vero cells, IC50 40.2 μg/mL) Antifungal, broth dilution assay (Trichophyton rubrum, MIC 500 μg/mL; Trichophyton mentagrophytes, MIC 250 μg/mL) | [118,121] |

| P. marginatum Jacq. | Belém, Pará state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | β-Caryophyllene (5.0%), propiopiperone (21.8%), elemol (5.9%) | Antifungal, TLC bioautography (Cladosporium cladosporioides, Cladosporium sphareospermum), enzyme inhibitory (acetylcholinesterase) | [62] |

| P. mikanianum (Kunth) Steud. | Sapiranga, Rio Grande do Sul state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (6.5%), myrcene (5.6%), limonene (14.8%), β-caryophyllene (10.5%), bicyclogermacrene (14.3%) | --- | [134] |

| P. mikanianum (Kunth) Steud. | Atalanta, Santa Catarina state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | Safrole (82.0%) | --- | [147] |

| P. mikanianum (Kunth) Steud. | Curitiba, Paraná state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | Bicyclogermacrene (5.3%), (Z)-isoelemicin (21.5%), (E)-asarone (11.6%), β-vetivone (33.5%) | --- | [148] |

| P. mikanianum (Kunth) Steud. | Picada Café, Rio Grando do Sul state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | Bicyclogermacrene (6.6%), germacrene B (7.8%), α-cadinol (5.1%), apiole (64.9%) | Acaricidal (Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus, LC50 2.33 μL/mL) | [106] |

| P. mikanianum (Kunth) Steud. | Atalanta, Santa Catarina state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | α-Thujene (6.0%), safrole (72.4%) | --- | [70] |

| P. mollicomum Kunth | Cultivated (State University of Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil) | Leaf (HD) | --- | Antibacterial (Escherichia coli, MIC 1000 μg/mL) | [52] |

| P. mollicomum Kunth | Cultivated, FIOCRUZ, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | (Z)-β-Ocimene (14.1%), (E)-β-ocimene (12.1%), germacrene D (10.8%), germacrene B (13.4%), myrtenic acid (7.5%), α-bisabolol (9.9%), (E)-nerolidol (9.6%) | Antinociceptive (mouse model, 1 mg/kg) | [91] |

| P. mosenii C. DC. | Antonina, Paraná state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | β-Caryophyllene (8.6%), α-humulene (11.3%), bicyclogermacrene (7.4%), caryophyllene oxide (12.1%), viridiflorol (5.8%), humulene epoxide II (6.3%) | Antileishmanial (L. amazonensis promastigotes, IC50 17.4 μg/mL; L. amazonensis axenic amastigotes, IC50 >200 μg/mL), anti-Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MIC 250 μg/mL) | [70] |

| P. multiplinervium C. DC. | Parque Nacional Soberania, Panama | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (7.1%), β-pinene (7.9%), α-phellandrene (11.8%), limonene (11.4%), p-cymene (9.0%), linalool (16.5%), (E)-nerolidol (5.5%) | --- | [47] |

| P. nemorense C. DC. | Monteverde, Costa Rica | Leaf (HD) | α-Phellandrene (8.8%), limonene (6.3%), α-copaene (5.7%), β-bourbonene (14.0%), β-caryophyllene (5.6%), β-copaene (15.0%), γ-elemene (6.8%), germacrene D (8.4%), bicyclogermacrene (7.5%) | --- | [34] |

| P. oblanceolatum Trel. | Monteverde, Costa Rica | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (6.2%), linalool (11.3%), β-caryophyllene (6.8%), germacrene D (8.9%), δ-amorphene (9.0%) | Antibacterial (Bacillus cereus, MIC 78 μg/mL), cytotoxic (MCF-7 human breast adenocarcinoma) | [34] |

| P. obliquum Ruiz & Pav. | Altos de Campana National Park, Panama | Leaf (HD) | β-Caryophyllene (27.6%), spathulenol (10.6%), caryophyllene oxide (8.3%) | --- | [111] |

| P. obliquum Ruiz & Pav. | Wasak'entsa reserve, Ecuador | Aerial parts (HD) | γ-Terpinene (17.1%), terpinolene (11.5%), safrole (45.9%) | --- | [65] |

| P. obrutum Trel. & Yunck. | Samurindó, Chocó, Colombia | Aerial parts (MWHD) | Linalool (15.8%), β-elemene (7.6%), α-humulene (6.4%), (E)-nerolidol (5.8%) | Antiprotozoal (Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigotes, IC50 29.3 μg/mL; Leishmania infantum promastigotes, IC50 35.9 μg/mL; L. infantum amastigotes, IC50 89.0 μg/mL); cytotoxic (Vero cells, IC50 45.3 μg/mL) | [118] |

| P. ovatum Vahl | Fazenda Sucupira, Embrapa, Brasília, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (23.1%), β-pinene (14.2%), β-caryophyllene (5.3%), germacrene D (10.3%), epi-cubebol (10.7%) | --- | [33] |

| P. peltatum L. [syn. Pothomorphe peltata (L.) Miq.] | Pinar del Río, Cuba | Leaf (HD) | α-Copaene (5.2%), trans-calamenene (5.4%), spathulenol (9.0%), caryophyllene oxide (22.9%) | --- | [27] |

| P. permucronatum Yunck. | Tijuca Forest, Rio de Janeiro state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | β-Caryophyllene (6.8%), δ-cadinene (12.7%), α-cadinol (6.9%) | --- | [149] |

| P. permucronatum Yunck. | State of Rondônia, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | Asaricin (8.6%), myristicin (25.6%), elemicin (9.9%), dillapiole (54.7%) | Mosquito larvicidal (Aedes aegypti, LC50 36 μg/mL) | [136] |

| P. plurinervosum Yunck. | Egler Reserva, Amazonas, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | 1,8-Cineole (31.6%), β-caryophyllene (6.6%), (E)-nerolidol (6.4%), caryophyllene oxide (5.7%), guaiol (6.2%), α-cadinol (8.5%) | --- | [129] |

| P. pseudolindenii C. DC. | Turrialba, Cartago, Costa Rica | Leaf (HD) | β-Pinene (6.7%), β-elemene (15.0%), β-caryophyllene (11.8%), α-humulene (7.0%), germacrene D (9.0%), germacrene B (5.4%) | --- | [133] |

| P. regnellii (Miq.) C. DC. | Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | β-Caryophyllene (23.4%), (E)-nerolidol (13.7%), spathulenol (11.1%), globulol (6.1%) | --- | [135] |

| P. regnellii (Miq.) C. DC. | Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | Myrcene (52.6%), linalool (15.9%), β-caryophyllene (8.5%) | Antimicrobial, agar diffusion assay (Staphylococcus aureus, Candida albicans) | [38] |

| P. regnellii (Miq.) C. DC. | Cultivated (State University of Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil) | Leaf (HD) | --- | Antibacterial (Escherichia coli, MIC 300 μg/mL) | [52] |

| P. regnellii (Miq.) C. DC. | Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | β-Pinene (13.3%), myrcene (15.5%), β-caryophyllene (7.2%), aromadendrene (8.3%), bicyclogermacrene (9.7%), (E)-nerolidol (8.4%), spathulenol (7.8%) | --- | [35] |

| P. regnellii (Miq) C. DC. var. regnellii (C. DC.) Yunck | Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | β-caryophyllene (8.2–9.5%), germacrene D (45.6–51.4%) and α-chamigrene (8.9–11.3%) | Cytotoxic (B16F10-Nex2 murine melanoma, IC50 66 μg/mL; A2058 human melanoma, IC50 57 μg/mL; HeLa human cervical carcinoma, IC50 13 μg/mL; SiHa human cervical IC50 71 μg/mL; HCT human colon carcinoma, IC50 61 μg/mL; SKBR3 breast cancer, IC50 79 μg/mL; U87 human glioblastoma, IC50 71 μg/mL; β-caryophyllene, germacrene D, α-chamigrene cytotoxic to HeLa cells: IC50 11, 7, 32 μg/mL, respectively) | [98] |

| P. renitens (Miq.) Yunck. | Mirante da Serra, Rondonia, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | α-Pinene (12.5%), camphene (5.6%), β-pinene (12.4%), (Z)-caryophyllene (6.9%), germacrene D (13.8%), bicyclogermacrene (6.6%), guaiol (13.9%), eudesm-7(11)-en-4-ol (9.3%) | --- | [150] |

| P. reticulatum L. | Costa Arriba, Rio Cascajal, Colon, Panama | Leaf (HD) | β-Elemene (16.1%), β-selinene (19.0%), α-selinene (15.5%), spathulenol (6.1%) | --- | [47] |

| P. rivinoides Kunth | Cultivated, FIOCRUZ, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (32.9%), β-pinene (20.7%), β-caryophyllene (7.6%), germacrene B (6.7%) | Antinociceptive (mouse model, 1 mg/kg) | [91] |

| P. rivinoides Kunth | Ubatuba, São Paulo state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (73.2%), β-pinene (5.2%) | --- | [31] |

| P. rivinoides Kunth | Antonina, Paraná state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | β-Caryophyllene (6.6%), α-humulene (10.0%), dehydroaromadendrane (7.8%), bicyclogermacrene (11.8%), (Z)-α-bisabolene (10.9%), spathulenol (5.1%) | Antileishmanial (L. amazonensis promastigotes, IC50 10.9 μg/mL; L. amazonensis axenic amastigotes, IC50 > 200 μg/mL), anti-Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MIC 125 μg/mL) | [70] |

| P. septuplinervium (Miq.) C. DC. | Pandó, Chocó, Colombia | Aerial parts (MWHD) | β-Caryophyllene (5.0%), epi-cubebol (9.0%), δ-cadinene (10.9%), germacrene D-4-ol (5.6%), viridiflorol (7.9%) | Antiprotozoal (Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigotes, IC50 14.0 μg/mL; Leishmania infantum promastigotes, IC50 30.1 μg/mL; L. infantum amastigotes, IC50 64.8 μg/mL); cytotoxic (Vero cells, IC50 42.7 μg/mL; THP-1 human monocytic leukemia, IC50 48.8 μg/mL) | [118] |

| P. solmsianum C. DC. | Teresópolis, Rio de Janeiro state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | δ-3-Carene (23.3%), asaricin (39.2%) | The essential oil and the major component asaricin cause depressant and ataxia effects in mice. | [151] |

| P. solmsianum C. DC. | Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | Spathulenol (5.2%), isoelemecin (53.5%) | Antifungal, broth dilution assay (Cryptococcus neoformans, MIC 62.5 μg/mL) Antifungal, TLC bioautography (Cladosporium cladosporioides, C. sphareospermum) | [35,60] |

| P. solmsianum C. DC. | Ubatuba, São Paulo state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (22.7%), myrcene (26.1%), δ-3-carene (66.9%), α-selinene (5.5%) | --- | [31] |

| P. tectoniaefolium (Kunth) Kunth ex C. DC. | Fazenda Sucupira, Embrapa, Brasília, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (12.9%), β-pinene (8.8%), caryophyllene oxide (10.9%) e | --- | [33] |

| P. trigonum C. DC. | Altos de Campana, Panama | Leaf (HD) | α-Copaene (6.0%), β-elemene (8.4%), β-caryophyllene (7.1%), germacrene D (19.7%), δ-cadinene (7.2%), α-cadinol (5.8%) | --- | [47] |

| P. tuberculatum Jacq. var. tuberculatum | Rondônia state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (8.4%), β-pinene (7.0%), limonene (6.7%), (E)-β-ocimene (9.0%), β-caryophyllene (26.3%), (E)-β-farnesene (6.1%), α-cadinol (13.7%) | --- | [152] |

| P. tuberculatum Jacq. | Universidade Estadual Paulista, Araraquara, São Paulo state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (10.4%), β-pinene (12.5%), (E)-β-ocimene (8.6%), β-caryophyllene (40.2%), (E)-β-farnesene (8.3%), germacrene D (5.5%) | --- | [59] |

| P. tuberculatum Jacq. | Universidade Estadual Paulista, Araraquara, São Paulo state, Brazil | Floral (HD) a | α-Pinene (28.7%), β-pinene (38.2%), (E)-β-ocimene (9.8%), β-caryophyllene (14.0%) | --- | [59] |

| P. tuberculatum Jacq. | Universidade Estadual Paulista, Araraquara, São Paulo state, Brazil | Stem (HD) | α-Pinene (17.3%), β-pinene (27.0%), (E)-β-ocimene (14.5%), β-caryophyllene (32.1%) | Antifungal, TLC bioautography (Cladosporium cladosporioides, Cladosporium sphareospermum) | [59] |

| P. tuberculatum Jacq. | Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | (E)-Nerolidol (12.7%), spathulenol (15.8%), viridiflorol (13.5%), τ-cadinol (6.3%) | --- | [35] |

| P. umbellatum L. | Monteverde, Costa Rica | Aerial parts (HD) | β-Elemene (6.9%), β-caryophyllene (28.3%), germacrene D (16.7%), bicyclogermacrene (6.6%), (E,E)-α-farnesene (14.5%) | --- | [49] |

| P. umbellatum L. | Araraquara, São Paulo state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | γ-Muurolene (8.9%), germacrene D (34.2%), bicyclogermacrene (9.0%), γ-cadinene (5.9%), δ-cadinene (15.0%) | --- | [35,60] |

| P. umbellatum L. | Topes de Collantes Nature Reserve, Escambray Mountains, Cuba | Leaf (HD) | Camphor (9.6%), safrole (26.4%), β-caryophyllene (6.6%) | Antioxidant (DPPH radical scavenging assay, IC50 32.3 μg/mL) | [50] |

| P. umbellatum L. | Campinas, São Paulo state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | β-Caryophyllene (6.3%), germacrene D (55.8%), bicyclogermacrene (11.8%) | --- | [31] |

| P. variabile C. DC. | Lachuá, Alta Verapaz, Guatemala | Leaf (HD) | Camphene (16.6%), p-cymene (6.3%), limonene (13.9%), camphor (28.4%), guaiol (6.3%) | --- | [140] |

| P. vicosanum Yunck. | Parque Estabdual do Rio Doce, Minas Gerais state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | α-Pinene (6.1%), 1,8-cineole (10.4%), limonene (45.5%) | --- | [153] |

| P. vicosanum Yunck. | Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | α-Pinene (7.2%), 1,8-cineole (15.0%), limonene (40.0%), terpinolene (10.1%) | --- | [153] |

| P. vicosanum Yunck. | Dourados, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | Limonene (9.1%), γ-elemene (14.2%), α-alaskene (13.4%) | Anti-inflammatory (rat paw edema, 100–300 mg/kg) | [89] |

| P. vitaceum Yunck. | Manaus-Caracaraí, Amazonas, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | p-Cymene (12.8%), limonene (33.2%), (E)-nerolidol (20.6%), caryophyllene oxide (5.2%) | --- | [129] |

| P. xylosteoides (Kunth) Steud. | Fazenda Sucupira, Embrapa, Brasília, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | Myrcene (31.0%), α-terpinene (11.3%), p-cymene (12.4%), γ-terpinene (26.1%) | --- | [17,33] |

| P. xylosteoides (Kunth) Steud. | São Francisco de Paula, Rio Grande do Sul state, Brazil | Aerial parts (HD) | α-Pinene (6.0%), limonene (5.1%), zingiberene (9.3%), safrole (47.8%) | Acaricidal (Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus, LC50 6.15 μL/mL) | [106] |

| P. xylosteoides (Kunth) Steud. | Orleans, Santa Catarina state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (7.7%), safrole (84.1%) | Antibacterial, broth dilution assay (Bacillus cereus, MIC 2091 μg/mL; Staphylococcus aureus, MIC 2091 μg/mL) | [154] |

| P. xylosteoides (Kunth) Steud. | São Bonifácio, Santa Catarina state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | α-Pinene (15.3%), safrole (75.8%) | Antibacterial, broth dilution assay (Bacillus cereus, MIC 2091 μg/mL; Staphylococcus aureus, MIC 2091 μg/mL) | [154] |

| P. xylosteoides (Kunth) Steud. | Ubatuba, São Paulo state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | Germacrene B (10.6%), trans-β-guaiene (7.8%), (E)-nerolidol (8.2%), spathulenol (12.3%), β-copaen-4α-ol (9.4%) | --- | [31] |

| P. xylosteoides (Kunth) Steud. | Cerro Azul, Paraná state, Brazil | Leaf (HD) | α-Thujene (7.9%), β-phellandrene (22.6%), δ-elemene (6.6%), β-caryophyllene (7.0%), bicyclogermacrene (7.2%), (E)-nerolidol (8.5%) | --- | [70] |

Appendix B

Appendix C

| Piper Species | Classes (%) | Biological activity | Ref. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PP | MH | OM | SH | OS | Total | |||

| P. aducum | 0.0 | 13.7 | 40.8 | 16.8 | 24.3 | 95.6 | Antiprotozoal | [53] |

| P. aduncum | 0.0 | 20.9 | 7.5 | 42.2 | 18.3 | 88.9 | Antiprotozoal | [70] |

| P. aduncum | 87.8 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 6.5 | 2.4 | 97.6 | Antimicrobial | [30] |

| P. aduncum | 0.0 | 14.1 | 31.8 | 26.0 | 11.6 | 83.5 | Antimicrobial | [35] |

| P. aduncum | 0.9 | 9.7 | 13.4 | 19.3 | 43.9 | 87.2 | Antiprotozoal | [68] |

| P. aduncum | 0.0 | 9.7 | 50.3 | 8.3 | 29.3 | 97.6 | Antiprotozoal | [32] |

| P. aduncum | 0.0 | 13.7 | 31.7 | 39.8 | 11.8 | 97.0 | Antimicrobial | [59] |

| P. aduncum | 0.0 | 55.1 | 11.8 | 13.9 | 10.6 | 91.4 | Antimicrobial | [59] |

| P. aduncum | 46.8 | 25.1 | 15.7 | 6.3 | 1.0 | 94.8 | Antimicrobial | [65] |

| P. aduncum | 89.2 | 1.1 | 2.2 | 3.8 | 2.6 | 98.9 | Insecticidal | [16] |

| P. aduncum | 95.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.9 | 99.2 | Acaricidal | [28] |

| P. aequale | 0.0 | 29.2 | 0.0 | 42.9 | 20.9 | 93.0 | Citotoxic | [95] |

| P. aequale | 3.7 | 70.2 | 0.2 | 12.4 | 13.5 | 100.0 | Antimicrobial | [34] |

| P. angustifolium | 0.0 | 13.4 | 4.7 | 21.9 | 53.0 | 93.0 | Antiprotozoal | [69] |

| P. anonifolium | 0.0 | 11.7 | 0.0 | 38.6 | 38.9 | 89.2 | Antimicrobial/Enzimaitc | [61] |

| P. aleyreanum | 0.0 | 10.1 | 0.0 | 56.7 | 23.1 | 89.9 | Antimicrobial/Citotoxic | [61] |

| P. aleyreanum | 0.0 | 16.6 | 16.4 | 16.2 | 28.3 | 77.5 | Antinociceptive/Anti-inflammatory | [90] |

| P. arboreum | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 46.7 | 41.0 | 89.4 | Antiprotozoal | [70] |

| P. auritum | 88.5 | 3.4 | 0.7 | 3.2 | 0.6 | 96.4 | Antiprotozoal | [117] |

| P. biasperatum | 0.0 | 4.5 | 0.0 | 94.9 | 0.0 | 99.4 | Cytotoxic | [34] |

| P. bredemeyeri | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 99.8 | 0.0 | 100.0 | Antimicrobial | [34] |

| P. caldense | 0.0 | 0.0 | 47.1 | 7.2 | 24.3 | 78.6 | Antimicrobial | [54] |

| P. caldense | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.5 | 17.2 | 59.7 | 83.4 | Antimicrobial | [54] |

| P. caldense | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 63.5 | 20.1 | 84.0 | Antimicrobial | [54] |

| P. callosun | 80.1 | 6.9 | 4.2 | 4.9 | 2.1 | 98.2 | Enzyme inhibitory | [62] |

| P. cernuum | 0.0 | 18.9 | 0.0 | 62.4 | 16.7 | 97.9 | Antimicrobial | [38] |

| P. cernuum | 0.0 | 3.1 | 0.0 | 81.3 | 15.0 | 99.4 | Antimicrobial | [60] |

| P. cernuum | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 78.9 | 0.0 | 78.9 | Cytotoxic | [39] |

| P. cernuum | 0.0 | 52.2 | 23.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 75.4 | Cytotoxic | [96] |

| P. cernuum | 0.0 | 20.5 | 0.0 | 31.0 | 35.0 | 86.5 | Antiprotozoal/Antimicrobial | [70] |

| P. cernuum | 0.0 | 12.3 | 1.2 | 10.4 | 75.5 | 99.4 | Antimicrobial | [37] |

| P. claussenianum | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 9.1 | 86.2 | 95.6 | Antiprotozoal/Antimicrobial | [71,126] |

| P. claussenianum | 0.0 | 1.5 | 51.4 | 7.5 | 28.3 | 88.7 | Antiprotozoal/Antimicrobial | [71,126] |

| P. corcovadensis | 30.6 | 35.1 | 0.2 | 20.4 | 6.4 | 92.7 | Insecticidal | [127] |

| P. crassinervium | 0.0 | 7.8 | 0.0 | 54.8 | 37.1 | 99.7 | Antimicrobial | [60] |

| P. demeraranum | 0.0 | 29.9 | 0.0 | 63.0 | 0.0 | 92.9 | Antiprotozoal | [72] |

| P. diospyrifolium | 0.0 | 19.5 | 1.1 | 68.2 | 11.2 | 100.0 | Antimicrobial | [55] |

| P. diospyrifolium | 0.0 | 16.1 | 0.0 | 46.5 | 28.5 | 91.1 | Antiprotozoal | [70] |

| P. divaricatum | 89.6 | 3.3 | 0.0 | 5.6 | 0.6 | 99.1 | Antimicrobial | [40] |

| P. divaricatum | 98.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 98.0 | Antimicrobial | [44] |

| P. divaricatum | 89.1 | 7.2 | 0.1 | 1.9 | 0.2 | 98.5 | Antimicrobial | [42] |

| P. duckei | 0.0 | 1.1 | 5.8 | 60.2 | 23.0 | 90.1 | Antiprotozoal | [72] |

| P. fimbriulatum | 0.0 | 19.5 | 0.0 | 76.4 | 4.1 | 100.0 | Antimicrobial | [34] |

| P. gaudichaudianum | 0.0 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 44.3 | 44.0 | 90.8 | Insecticidal | [136] |

| P. gaudichaudianum | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 65.4 | 28.3 | 93.8 | Cytotoxic | [138] |

| P. gaudichaudianum | 0.1 | 4.2 | 0.4 | 56.0 | 29.5 | 90.2 | Cytotoxic | [137] |

| P. gaudichaudianum | 0.0 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 72.6 | 14.4 | 87.9 | Antimicrobial | [35] |

| P. gaudichaudianum | 0.0 | 7.1 | 0.0 | 76.0 | 9.9 | 93.0 | Antiprotozoal | [70] |

| P. glabratum | 0.2 | 25.8 | 1.0 | 50.4 | 21.2 | 98.6 | Anti-inflammatory | [88] |

| P. glabrescens | 0.0 | 83.7 | 0.0 | 15.3 | 1.0 | 100.0 | Cytotoxic | [34] |

| P. hispidinervum | 85.5 | 9.3 | 0.0 | 2.5 | 0.8 | 98.0 | Antimicrobial | [139] |

| P. hispidum | 0.0 | 18.5 | 1.0 | 52.2 | 16.6 | 88.3 | Antimicrobial/Enzyme inhibitory | [61] |

| P. hispidum | 0.0 | 43.9 | 1.7 | 27.8 | 15.4 | 88.8 | Antimicrobial/Cytotoxic | [97] |

| P. hispidum | 58.3 | 5.0 | 12.6 | 14.2 | 5.0 | 95.1 | Insecticidal | [47] |

| P. hostmannianum | 57.0 | 1.0 | 5.6 | 20.1 | 10.6 | 94.3 | Insecticidal | [136] |

| P. humaytanum | 0.0 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 34.0 | 45.4 | 80.9 | Insecticidal | [136] |

| P. ilheuense | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 46.5 | 34.1 | 80.6 | Antimicrobial | [57] |

| P. imperiale | 6.7 | 2.7 | 0.0 | 89.4 | 1.2 | 100.0 | Antimicrobial/Cytotoxic | [34] |

| P. klotzschianum | 98.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 99.6 | Insecticidal | [141] |

| P. klotzschianum | 39.4 | 44.3 | 0.0 | 14.5 | 0.0 | 98.2 | Insecticidal | [141] |

| P. longispicum | 1.1 | 1.4 | 0.2 | 66.0 | 11.9 | 80.6 | Insecticidal | [47] |

| P. marginatum | 0.0 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 2.2 | 26.2 | 30.5 | Insecticidal | [146] |

| P. marginatum | 28.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 44.6 | 26.2 | 99.2 | Insecticidal | [146] |

| P. marginatum | 51.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 21.7 | 26.4 | 99.7 | Insecticidal | [146] |

| P. marginatum | 42.0 | 10.3 | 1.6 | 17.6 | 17.5 | 89.0 | Antimicrobial/Enzyme inhibitory | [62] |

| P. mikanianum | 67.9 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 23.4 | 8.6 | 100.4 | Acaricidal | [106] |

| P. mollicomum | 0.6 | 24.2 | 9.8 | 33.2 | 25.1 | 92.9 | Antinociceptive | [91] |

| P. mosenii | 0.0 | 7.2 | 0.0 | 41.5 | 37.7 | 86.4 | Antiprotozoal/Antimicrobial | [70] |

| P. oblanceolatum | 0.0 | 16.6 | 12.2 | 61.4 | 9.8 | 100.0 | Antimicrobial/Cytotoxic | [34] |

| P. permucronatum | 98.8 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 99.6 | Insecticidal | [136] |

| P. regnellii | 0.0 | 60.8 | 17.8 | 13.8 | 6.1 | 98.5 | Antimicrobial | [38] |

| P. regnellii | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 82.0 | 10.8 | 93.5 | Cytotoxic | [98] |

| P. rivinoides | 0.0 | 65.9 | 0.8 | 21.8 | 4.8 | 93.2 | Antinociceptive | [91] |

| P. rivinoides | 0.0 | 10.4 | 0.0 | 54.7 | 20.1 | 85.2 | Antiprotozoal | [70] |

| P. solmsianum | 40.3 | 30.3 | 0.0 | 5.8 | 4.2 | 80.7 | Depressant/Ataxia | [151] |

| P. solmsianum | 53.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 12.4 | 12.3 | 78.2 | Antimicrobial | [35] |

| P. tuberculatum | 0.0 | 35.7 | 0.3 | 60.2 | 2.9 | 99.1 | Antimicrobial | [59] |

| P. vicosanum | 0.0 | 16.4 | 0.0 | 62.6 | 20.8 | 99.8 | Anti-inflammatory | [89] |

| P. xylosteoides | 48.5 | 17.0 | 0.4 | 23.7 | 10.4 | 100.0 | Acaricidal | [106] |

References

- Quijano-Abril, M.A.; Callejas-Posada, R.; Miranda-Esquivel, D.R. Areas of endemism and distribution patterns for Neotropical Piper species (Piperaceae). J. Biogeogr. 2006, 33, 1266–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez Amezcua, J.M. Piper commutatum (Piperaceae), the correct name for a widespread species in Mexico and Mesoamerica. Acta Botanica Mexicana 2016, 116, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]