The Effect of High Pressure Techniques on the Stability of Anthocyanins in Fruit and Vegetables

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Principles and Food Applications of High Pressure Techniques

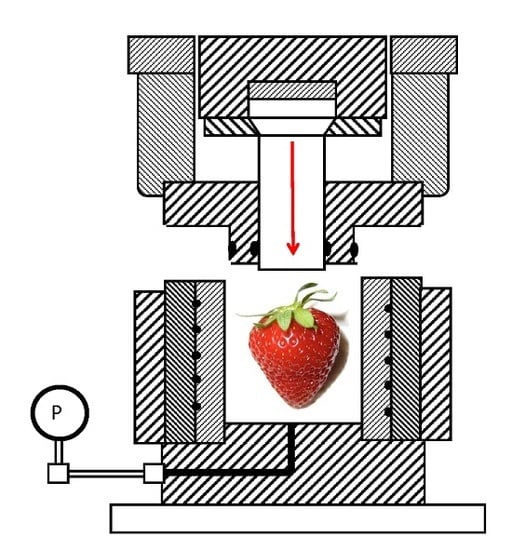

2.1. High Pressure Processing (HPP)

2.2. High Pressure Carbon Dioxide (HPCD)

2.3. High Pressure Homogenization (HPH)

3. Anthocyanins Stability Factors

3.1. Role of Enzymes in Anthocyanins Degradation

3.2. Other Factors Affecting Anthocyanin Stability

4. Inactivation of Enzymes Responsible for Degradation of Anthocyanins during Pressure Processes

4.1. High Pressure Processing (HPP)

4.2. High Pressure Carbon Dioxide (HPCD)

4.3. High Pressure Homogenization (HPH)

5. Stability of Anthocyanins under Pressurization

5.1. High Pressure Processing (HPP)

5.2. High Pressure Carbon Dioxide (HPCD)

5.3. High Pressure Homogenization (HPH)

6. Traditional Thermal Processing (TP) vs. Pressure Techniques

7. Influence of High Pressure on the Anthocyanin Stability during Storage

7.1. High Pressure Processing (HPP)

7.2. High Pressure Carbon Dioxide (HPCD)

7.3. High Pressure Homogenization (HPH)

8. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Torres, B.; Tiwari, B.K.; Partas, A.; Cullen, P.J.; Brunton, N.; O’Donnel, C.P. Stability of anthocyanins and ascorbic acid of high pressure processes blood orange juice during storage. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. 2011, 12, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oren-Shamir, M. Does anthocyanins degradation play a significant role in determining pigment concentration in plants? Plant Sci. 2009, 177, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, B.K.; O’Donnell, C.P.; Cullen, P.J. Effect of non-thermal processing technologies on the anthocyanin content of fruit juices. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2009, 20, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patras, A.; Brunton, N.P.; O’Donnell, C.; Tiwari, B.K. Effect of thermal processing on anthocyanin stability in foods; mechanisms and kinetics of degradation. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 21, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougall, G.J.; Fyffe, S.; Dobson, P.; Stewart, D. Anthocyanins from red wine—Their stability under simulated gastrointestinal digestion. Phytochemistry 2005, 66, 2540–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wrolstad, R.E.; Durst, R.W.; Jungmin, L. Tracking color and pigment changes in anthocyanin products. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2005, 16, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeyst, L.; Oey, I.; Plancken, V.I.; Hendrickx, M.; Loey, A. Kinetic study on the thermal and pressure degradation of anthocyanins in strawberries. Food Chem. 2010, 123, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, F.J.; Terefe, N.S.; Buckow, R.; Knorr, D.; Orlien, V. New opportunities and perspectives of high pressure treatment improve health and safety attributes of foods. Food Res. Int. 2015, 77, 725–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, G.; Kay, C.D.; Cottrell, T.; Holub, B.J. Absorption of anthocyanins from blueberries and serum antioxidant status in human subjects. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 7731–7737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bitsch, I.; Janssen, M.; Netzel, M.; Strass, G.; Frank, T. Bioavailability of anthocyanidin-3-glycosides following consumption of elderberry extract and blackcurrant juice. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2004, 42, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bub, A.; Watzl, B.; Heeb, D.; Rechkemmer, G.; Briviba, K. Malvidin-3-glucoside bioavailability in humans after ingestion of red wine, dealcoholised red wine and red grape juice. Eur. J. Nutr. 2001, 40, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, T.; Netzel, M.; Strass, G.; Bitsch, I. Bioavailability of anthocyanidin-3-glucosides following consumption of red wine and red grape juice. Can. J. Physiol. Pharm. 2003, 81, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marszałek, K.; Mitek, M.; Skąpska, S. The effect of thermal pasteurization and high pressure processing at cold and mild temperatures on the chemical compositions, microbial and enzyme activity in strawberry puree. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. 2015, 27, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Sánchez, C.; Lozano-Sánchez, J.; Seguera-Carretero, A.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A. Alternatives to conventional thermal treatments in fruit-juice processing. Part 1: Techniques and applications. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 501–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenez-Sánchez, C.; Lozano-Sánchez, J.; Seguera-Carretero, A.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A. Alternatives to conventional thermal treatments in fruit-juice processing. Part 2: Effect on composition. Phytochemical content, and physicochemical, rheorogical, and organoleptic properties of fruit juices. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 637–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butz, P.; Garcia, F.; Lindauer, R.; Dietrich, S.; Bognar, A.; Tauscher, B. Influence of ultra-high pressure processing on fruit and vegetable products. J. Food Eng. 2003, 56, 233–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdamidis, V.P.; Graham, W.D.; Beattie, A.; Linton, M.; McKay, A.; Fearon, A.M.; Petterson, M.F. Defining the stability interfaces of apple juice: Implications on the optimisation and design of high hydrostatic pressure treatment. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. 2010, 10, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deuel, C.L.; Plotto, A. Strawberries and Raspberries. In Processing Fruits: Science and Technology, 2nd ed.; Barrett, D.M., Somogyi, L.P., Ramaswamy, H.S., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Oey, I.; Lille, M.; van Loey, A.; Hendrickx, M. Effect of high pressure processing on colour, texture and flavour of fruit and vegetable-based food products. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2008, 19, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damar, S.; Balaban, M.O. Review of dense phase CO2 technology: Microbial and enzyme inactivation, and effects on food quality. J. Food Sci. 2006, 71, R1–R11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betoret, E.; Betoret, N.; Carbonell, J.V.; Fito, P. Effects of pressure homogenization on particle size and the functional properties of citrus juices. J. Food Eng. 2009, 92, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, K.; Köhler, K.; Schuchmann, H.P. Stability of anthocyanins in high pressure homogenisation. Food Chem. 2012, 130, 716–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Jacobo, Á.; Rüfer, C.E.; Gervilla, R.; Guamis, B.; Roig-Sagués, A.X.; Saldo, J. Influence of ultra-high pressure homogenisation on antioxidant capacity, polyphenol and vitamin content of clear apple juice. Food Chem. 2011, 127, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suárez-Jacobo, Á.; Saldo, J.; Rüfer, C.E.; Guamis, B.; Roig-Sagués, A.X.; Gervilla, R. Aseptically packaged UHPH-treated apple juice: Safety and quality parameters during storage. J. Food Eng. 2012, 109, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velázquez-Estrada, R.M.; Hernández-Herrero, M.M.; Rüfer, C.E.; Guamis-López, B.; Roig-Sagués, A.X. Influence of ultra-high-pressure homogenization processing on bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity of orange juice. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. 2013, 18, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro-Funes, N.; Bosch-Fusté, J.; Veciana-Nogués, M.T.; Vidal-Carou, M.C. Changes of isoflvones and protein quality in soymilk pasteurized by ultra-high-pressure homogenisation throughout storage. Food Chem. 2014, 162, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumay, E.; Chevalier-Lucia, D.; Picart-Palmade, L.; Benzaria, A.; Gràcia-Julià, A.; Blayo, C. Technological aspects and potential applications of ultra-high-pressure homogenisation. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 31, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Munoz, M.; Chevalier-Lucia, D.; Dumay, E. Characteristics of submicron emulsions prepared by ultra-high pressure homogenisation: Effect of chilled or frozen storage. Food Hydrocoll. 2009, 23, 640–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, M.G.; Kelly, A.L. High-pressure homogenisation of raw whole bovine milk effects on fat globule size and other properties. J. Dairy Res. 2003, 70, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiełczewska, K.; Kruk, A.; Czerniewicz, M.; Haponiuk, E. Effects of high-pressure homogenisation on the physicochemical properties of milk with various fat concentrations. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2006, 56, 91–94. [Google Scholar]

- Vachon, J.F.; Khedar, E.E.; Giasson, J.; Pasquin, P.; Fliss, I. Inactivation of foodborne pathogens in milk using dynamic high pressure. J. Food Prot. 2002, 65, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanciotti, R.; Vannini, L.; Patrignani, F.; Lucci, L.; Valliceli, M.; Ndagijimana, M.; Guerzoni, M.E. Effect of high pressure homogenisation of milk on cheese field and microbiology, lipolysis and proteolysis during ripening of Caciotta cheese. J. Dairy Res. 2006, 73, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calligaris, S.; Foschia, M.; Bartolomeoli, I.; Maifreni, M.; Manzocco, L. Study on the applicability of high-pressure homogenization for the production of banana juices. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 45, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wu, J.; Xiao, G.; Fu, M.; Zhang, Y. Effect of ultra-high-pressure homogenization processing on phenolic compounds, antioxidant capacity and anti-glucosidase of mulberry juice. Food Chem. 2014, 153, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Augusto, P.E.D.; Ibarz, A.; Cristianini, M. Effect of high pressure homogenization (HPH) on the rheological properties of tomato juice: Time-dependent and steady-state shear. J. Food Eng. 2012, 111, 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrignani, F.; Vannini, L.; Leroy, S.; Kamdem, S.; Lancotti, R.; Guerzoni, E.M. Effect of high-pressure homogenization on Saccharomyces cerevisiae inactivation and physic-chemical features in apricot and carrot juices. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2009, 136, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardeike, J.; Hommoss, A.; Müller, R.H. Lipid nanoparticles (SLN, NLC) in cosmetic and pharmaceutical dermal products. Int. J. Pharm. 2009, 366, 170–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, W.; Mao, S.; Shi, Y.; Li, L.C.; Fang, L. Nanonization of itraconazole by high-pressure homogenization: Stabilizer optimization and effect of particle size on oral absorption. J. Pharm. Sci. 2011, 100, 3365–3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suárez-Jacobo, Á.; Gervilla, R.; Guamis, B.; Roig-Sagués, A.X.; Saldo, J. Effect of UHPH on indigenous microbiota of apple juice: A preliminary study of microbial shelf-life. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2010, 136, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velázquez-Estrada, R.M.; Hernández-Herrero, M.M.; López-Pedemonte, T.J.; Briñez-Zambrano, W.J.; Rüfer, C.E.; Guamis-López, B.; Roig-Sagués, A.X. Inactivation of Listeria monocytogenes and Salmonella enterica serovar Senftenberg 775W inoculated into fruit juice by means of ultra-high-pressure homogenisation. Food Control. 2011, 22, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velázquez-Estrada, R.M.; Hernández-Herrero, M.M.; Guamis-López, B.; Roig-Sagués, A.X. Impact of ultra-high-pressure homgenization on pectin methylesterase activity and microbial characteristics of orange juice: A comparative study against conventional heat pasteurization. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. 2012, 13, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donsì, F.; Ferrari, G.; Lenza, E.; Maresca, P. Main factors regulating microbial inactivation by high-pressure homogenization: Operating parameters and scale of operation. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2009, 64, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maresca, P.; Donsì, F.; Ferrari, G. Application of a multi-pass high-pressure homogenization treatment for the pasteurization of fruit juices. J. Food Eng. 2011, 104, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amador-Espejo, G.G.; Suàrez-Berencia, A.; Juan, B.; Bárcenas, M.E.; Trujillo, A.J. Effect of moderate inlet temperatures in ultra-high-pressure homogenization treatments on physicochemical and sensory characteristics of milk. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 659–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahiri, I.; Makhlouf, J.; Paquin, P.; Fliss, I. Inactivation off food spoilage bacteria and Escherichia coli O157:H7 in phosphate buffer and orange juice using dynamic high pressure. Food Res. Int. 2006, 39, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuytack, E.Y.; Diels, A.M.J.; Michiels, C.W. Bacterial inactivation by high-pressure homogenisation and high hydrostatic pressure. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2002, 77, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grácia-Juliá, A.; René, M.; Cortés-Munoz, M.; Picart, L.; López-Pedemonte, T.; Chevalier, D.; Dumay, E. Effect of dynamic high pressure on whey protein aggregation: A comparison with the effect of continuous short-time thermal treatments. Food Hydrocoll. 2008, 22, 1014–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenmenger, M.J.; Reyes de Corcuera, J.I. High-pressure enhancement of enzymes. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2009, 45, 331–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Li, D.; Liu, C.; Cheng, A.; Wang, W. Partial purification and characterization of polyphenol oxidase and peroxidase from chestnut kernel. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 60, 1095–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, M.V.; Whitaker, J.R. The biochemistry and control of enzymatic browning. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 6, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elstner, E.F.; Heupel, A. Formation of hydrogen peroxide by isolated cell walls from horseradish (Amoracia lapathifolia Gilib.). Planta 1976, 130, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, R.J.; Gupta, R.C.; Saranjit, S.; Bansal, A.K.; Singh, I.P. Stability of anthocyanins- and anthocyanins-enriched extracts, and formulations of fruit pulp of Eugenia jambolana (“jamun”). Food Chem. 2016, 190, 808–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Rosso, V.V.; Mercadante, A.Z. The high ascorbic acid content is the main cause of the low stability of anthocyanin extracts from acerola. Food Chem. 2007, 103, 935–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bąkowska-Barczak, A. Acylated anthocyanins as stable, natural food colorants. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2005, 14, 107–116. [Google Scholar]

- Torskangerpoll, K.; Andersen, O. Colour stability of anthocyanins in aqueous solution at various pH values. Food Chem. 2005, 89, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C.; Rojanasasithara, T.; Mutilangi, W.; McClements, D.J. Stability improvement of natural food colors: Impact of amino acid and peptide on anthocyanins stability in model beverages. Food Chem. 2017, 218, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercadante, A.Z.; Bobbio, F.O. Anthocyanins in Foods: Occurrence and Physicochemical Properties. In Food Colorants: Chemical and Functional Properties; Sociaciu, C., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, F.J. Food colorants: Anthocyanins. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. 1989, 28, 273–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.; Yu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wen, G.; Wei, F.; Zheng, Q.; Wang, C.; Xiao, X. Stability-increasing effects of anthocyanins glycosyl acylation. Food Chem. 2017, 214, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morild, E. The theory of pressure effects on enzymes. Adv. Protein Chem. 1981, 34, 93–166. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cano, M.P.; Hernandez, A.; Ancos, B. High-pressure and thermal effects on enzyme inactivation in strawberry and orange products. J. Food Sci. 1997, 62, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terefe, N.S.; Matthies, K.; Simons, L.; Versteeg, C. Combined high-pressure-mild temperature processing for optimal retention of physical and nutrition quality of strawberries (Fragaria × ananassa). Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. 2009, 10, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terefe, N.S.; Yang, Y.H.; Knoerzer, K.; Buckow, R.; Versteeg, C. High-pressure and thermal inactivation kinetics of polyphenol oxidase and peroxidase in strawberry puree. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. 2010, 11, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terefe, N.S.; Kleintschek, T.; Gamage, T.; Fanning, K.J.; Netzel, G.; Versteeg, C.; Netzel, M. Comparative effect of thermal and high-pressure processing on phenolic phytochemicals in different strawberry cultivars. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. 2013, 19, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Wang, Y.; Yi, J.; Liao, X. Effects of high hydrostatic pressure on enzymes, phenolic compounds, anthocyanins, polymeric color and color of strawberry pulps. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2011, 91, 877–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duong, T.; Balaban, M. Optimisation of the process parameters of combined high hydrostatic pressure and dense phase carbon dioxide on enzyme inactivation in feijoa (Acca sellowiana) puree using response surface methodology. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. 2014, 26, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Rao, P.S.; Mishra, H.N. Kinetic modeling of polyphenoloxidase and peroxidase inactivation in pineapple (Ananas comosus L.) puree during high-pressure and thermal treatments. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. 2015, 27, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anese, M.; Nicoli, M.C.; Dall Aglio, G.; Lerici, C.R. Effect of high-pressure treatments on peroxidase and polyphenoloxidase activities. J. Food Biochem. 1995, 18, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaka, M.; Hayashi, R. Activation of Polyphenoloxidase in pear fruits by high-pressure treatment. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1991, 55, 2439–2440. [Google Scholar]

- Butz, P.; Koller, W.D.; Tauscher, B.; Wolf, S. Ultra-high-pressure processing of onions: Chemical and sensory changes. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 1994, 27, 463–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolibert, F.; Tonello, C.; Sagegh, P.; Raymond, J. Effect of high pressure on fruit polyphenol oxidase. BIOS 1994, 251, 27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Weemaes, C.A.; Ludikhuyze, L.R.; van den Broeck, I.; Hendrickx, M.E. Kinetic of combined pressure-temperature inactivation of avocado polyphenoloxidase. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1998, 60, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, A.; Silva, F.V.M. High pressure processing, thermal processing and freezing of “Camarosa” strawberry for the inactivation of polyphenoloxidase and control of browning. Food Control 2013, 33, 424–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Palazon, A.; Suthanthangjai, W.; Kajda, P.; Zabetakis, I. The effects of high pressure on β-glucosidase, peroxidase and polyphenoloxidase in red raspberry (Rubus idaeus) and strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa). Food Chem. 2004, 88, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Baier, D.; Knorr, D.; Mishra, H.N. High pressure inactivation of polygalacturonase, pectinmethylesterase and polyphenoloxidase in strawberry puree mixed with sugar. Food Bioprod. Process. 2015, 95, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marszałek, K.; Woźniak, Ł.; Skąpska, S. Application of high pressure mild temperature processing for prolonging shelf-life of strawberry purée. High Press. Res. 2016, 36, 220–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finten, G.; Aguero, M.V.; Jagus, R.J.; Niranjan, K. High hydrostatic pressure blanching of baby spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.). LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 73, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, N.; Rao, P.S.; Mishra, H.N. Process optimalization for thermal-assisted high-pressure processing of mango (Mangifera indica L.) pulp using response surface methodology. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 69, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terefe, N.S.; Delon, A.; Buckow, R.; Versteeg, C. Blueberry polyphenol oxidase: Characterization and the kinetics of thermal and high-pressure activation and inactivation. Food Chem. 2015, 188, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Parra, J.; Gonzalez-Cebrino, F.; Delgado, J.; Cava, R.; Ramirez, R. High-pressure assisted thermal processing of pump kin puree: Effect on microbial counts, color, bioactive compounds and polyphenoloxidase enzyme. Food Bioprod. Process. 2016, 98, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Kebede, B.T.; Dang, D.N.H.; Buve, C.; Grauwet, T.; Loey, A.V.; Hendrickx, M. Quality change during high-pressure processing and thermal processing of cloudy apple juice. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 75, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xu, Q.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Ning, C.; Chang, X.; Meng, X. Effects of high hydrostatic pressure on physicochemical properties, enzymes activity, and antioxidant capacities of anthocyanins extracts of wild Lonicera caerulea berry. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. 2016, 36, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paciulli, M.; Medina-Meza, I.G.; Chiavaro, E.; Barbosa-Canovas, G.V. Impact of thermal and high pressure processing on quality parameters of beetroot (Beta vulgaris L.). LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 68, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terefe, N.S.; Tepper, P.; Ullman, A.; Knoerzer, K.; Juliano, P. High-pressure thermal processing of pears: Effect on endogenous enzyme activity and related quality attributes. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. 2016, 33, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marszałek, K.; Skąpska, S.; Woźniak, Ł.; Sokołowska, B. Application of supercritical carbon dioxide for the preservation of strawberry juice: Microbial and physicochemical quality, enzymatic activity and the degradation kinetics of anthocyanins during the storage. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. 2015, 32, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marszałek, K.; Skąpska, S.; Woźniak, Ł. Effect of supercritical carbon dioxide on selected quality parameters of preserved strawberry juice. Food Sci. Technol. Quality 2015, 2, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, F.; Wu, J.; Chen, F.; Liao, X.; Hu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Z. Inactivation of polyphenol oxidases in cloudy apple juice exposed to supercritical carbon dioxide. Food Chem. 2007, 100, 1678–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Pozo-Insfran, D.; Balaban, M.O.; Talcott, S.T. Inactivation of polyphenol oxidase in muscadine grape juice by dense phase-CO2 processing. Food Res. Int. 2007, 40, 894–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Wang, Y.; Hu, X.; Wu, J.; Liao, X. Effect of high pressure carbon dioxide on the quality of carrot juice. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. 2009, 10, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spilimbergo, S.; Komes, D.; Vojvodic, A.; Levaj, B.; Ferretino, G. High-pressure carbon dioxide pasteurization of fresh-cut carrot. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2013, 79, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.; Xu, Z.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yang, Y.; Liao, X.; Hu, X. Comparative study on cloudy apple juice qualities from apple slices treated by high-pressure carbon dioxide and mild heat. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. 2010, 11, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownmiller, C.; Howard, L.R.; Prior, R.L. Processing and storage effects on monomeric anthocyanins, percent polymeric color, and antioxidant capacity of processed blueberry products. J. Food Sci. 2008, 73, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, A.; Ahkoh, C.C.; Yi, W.; Fischer, J.; Krewer, G. Effect of storage conditions on the biological activity of phenolic compounds of blueberry extract packed in glass bottles. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 2705–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirsch, A.R.; Alexandra, K.; Carle, R.; Neidhart, S. Impact of minimal heat-processing on pectin methylesterase and peroxidase activity in freshly squeezed citrus juices. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2011, 232, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, J.L.; Izquierdo, L.; Carbonell, J.V.; Sentandreu, E. Effect of pH, temperature and maturity on pectinmethylesterase inactivation of citrus juices treated by high-pressure homogenization. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 57, 785–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floury, J.; Bellettre, J.; Legrand, J.; Desrumaux, A. Analysis of new type of high-pressure homogeniser. A study of the flow pattern. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2004, 59, 843–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, N.S.; Capellas, M.; Hernández, M.; Trujillo, A.J.; Guamis, B.; Ferragut, V. Ultra-high-pressure homogenization of soymilk: Microbiological, physicochemical and microstructural characteristics. Food Res. Int. 2007, 40, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacroix, N.; Fliss, I.; Makhlouf, J. Inactivation of pectin methylesterase and stabilization of opalescence in orange juice by dynamic high-pressure. Food Res. Int. 2005, 38, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balny, C.; Masson, P. Effects of high-pressure on proteins. Food Rev. Int. 1993, 9, 611–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welti-Chanes, J.; Ochoa-Velasco, C.E.; Guerrero-Beltrán, J.Á. High-pressure homogenization of orange juice to inactivate pectinmethylesterase. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. 2009, 10, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karacam, C.H.; Sahin, S.; Oztop, M.H. Effect of high pressure homogenization (microfluidization) on the quality of Ottoman strawberry (F. Ananassa) juice. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 64, 932–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreño, J.M.; Gurrea, M.C.; Sampedro, F.; Carbonell, J.V. Effect of high hydrostatic pressure and high-pressure homogenisation on Lactobacillus plantarum inactivation kinetics and quality parameters of mandarin juice. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2011, 232, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, M.A.; Linton, M.; Stirling, J.; Mackle, A.; Patterson, F.M. A comparative study of changes in the microbiota of apple juice treated by high hydrostatic pressure (HHP) or high pressure homogenisation (HPH). Food Microbiol. 2011, 28, 1426–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, G.; Maresca, P.; Ciccarone, R. The effects of high hydrostatic pressure on the polyphenols and anthocyanins in red fruit products. Procedia Food Sci. 2011, 1, 847–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeyst, L.; Hendrickx, M.; Loey, A. Charakterisation and screening of the process stability of bioactive compounds in red fruit paste and red fruit juice. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2012, 234, 593–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrales, M.; Butz, P.; Tausher, B. Anthocyanin condensation reactions under high hydrostatic pressure. Food Chem. 2008, 110, 627–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, F.J.; Esteve, M.J.; Frigola, A. Physicochemical and nutritional characteristic of blueberry juice after high pressure processing. Food Res. Int. 2013, 50, 545–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, G.; Maresca, P.; Ciccarone, R. The application of high hydrostatic pressure for the stabilization of functional foods: Pomegranate juice. J. Food Eng. 2010, 100, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodelón, O.G.; Avizcuri, J.M.; Fernández-Zurbano, P.; Dizy, M.; Préstamo, G. Pressurization and cold storage of strawberry purée: Colour, anthocyanins, ascorbic acid and pectin methylesterase. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 52, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabroni, S.; Amenta, M.; Timpanaro, N.; Rapisarda, P. Supercritical carbon dioxide-treated blood orange juice as a new product in the fresh juice market. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. 2010, 11, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Rodrigues, M.M.; Plaza, M.L.; Azeredo, A.; Balaban, M.O.; Marshall, M.R. Phytochemical, sensory attributes and aroma stability of dense phase carbon dioxide processed Hibiscus sabdariffa beverage during storage. Food Chem. 2012, 134, 1425–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, H.; Lit, T.; Bi, X.; Zhao, L.; Wang, Y.; Liao, X. Comparison of high hydrostatic pressure, high-pressure carbon dioxide and high-temperature short-time processing on quality of mulberry juice. Food Bioprocess. Technol. 2016, 9, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Pozo-Insfran, D.; Balaban, M.O.; Talcott, S.T. Microbial stability, phytochemical retention, and organoleptic attributes of dense phase CO2 processed muscadine grape juice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 5468–5473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Pozo-Insfran, D.; Balaban, M.O.; Talcott, S.T. Enhancing the retention of phytochemicals and organoleptic attributes in muscadine grape juice through a combined approach between dense phase CO2 processing and copigmentation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 6705–6712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danişman, G.; Arslan, E.; Toklucu, A.K. Kinetic analysis of anthocyanin degradation and polymeric colour formation in grape juice during heating. Czech J. Food Sci. 2015, 33, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syamaladevi, R.M.; Insan, S.K.; Dhawan, S.; Andrews, P.; Sablani, S.S. Physicochemical properties of encapsulated red raspberry (Rubus idaeus) powder: Influence of high-pressure homogenization. Dry Technol. 2012, 30, 484–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Zhong, Q. The improved thermal stability of anthocyanins at pH 5.0 by gum Arabic. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 64, 706–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouniaki, S.; Kajda, P.; Zabetakis, I. The effect of high hydrostatic pressure on anthocyanins and ascorbic acid in blackcurrant (Ribes nigrum). Flavour Fragr. J. 2004, 19, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabetakis, I.; Koulentianos, A.; Orruno, E.; Boyes, I. The effect of high hydrostatic pressure on strawberry flavour compounds. Food Chem. 2000, 71, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suthanthangjai, W.; Kajda, P.; Zabetakis, I. The effect of high hydrostatic pressure on the anthocyanins of raspberry (Rubus ideus). Food Chem. 2005, 90, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimenez, J.; Kajda, P.; Margomenou, L.; Piggott, J.R.; Zabetakis, I. A study on the color and sensory attributes of high hydrostatic pressure jams as compared with traditional jams. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2001, 81, 1228–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Pozo-Insfran, D.; del Follo-Martinez, A.; Talcott, S.T.; Brenes, C.H. Stability of copigmented anthocyanins and ascorbic acid in muscadine grape juice processes by high hydrostatic pressure. J. Food Sci. 2007, 72, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, X.; Bi, X.; Huang, W.; Wu, J.; Hu, X.; Liao, X. Changes of quality of high hydrostatic pressure processed cloudy and clear strawberry juices during storage. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. 2012, 16, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marszałek, K.; Woźniak, Ł.; Skąpska, S.; Mitek, M. High-pressure processing, and thermal pasteurization of strawberry puree: Quality parameters, and shelf life evaluation during cold storage. J. Food Sci. Technol. Mysore 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.; Ren, P.; Cao, X.; Yan, B.; Liao, X.; Sun, Z.; Wang, Y. Comparing quality changes of cupped strawberry treated by high hydrostatic pressure ant thermal processing during storage. Food Bioprod. Process. 2016, 100, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Lin, Y.; Zhan, Y.; He, J.; Zhu, S. Effect of high pressure processing on the stability of anthocyanins, ascorbic acid and color of Chinese bayberry juice during storage. J. Food Process. 2013, 119, 701–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Xi, H.; Guo, X.; Qin, Z.; Pang, X.; Hu, X.; Liao, X.; Wu, J. Comparative study of quality of cloudy pomegranate juice treated by high hydrostatic pressure and high temperature short time. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. 2013, 19, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Błaszczak, W.; Amarowicz, R.; Górecki, A. Antioxidant capacity, phenolic composition and microbial stability of aronia juice subjected to high hydrostatic pressure processing. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. 2017, 39, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Enzyme | Source | Processing Conditions | Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPO | Apples | 300–700 MPa, 25 °C, 1 min | Activation at 300 MPa and inactivation at 700 MPa | [68] |

| Avocados | Up to 900 MPa, 25–77 °C | Pressure increase caused a decrease in inactivation rate | [72] | |

| Onions | >700 MPa, 25 °C, 10 min | Activation, maximal at 500 MPa | [70] | |

| Pears | 400, 25 °C, 10 min | Activation | [69] | |

| Pears | 900 MPa, 25 °C | slight inactivation | [72] | |

| White grapes | 700 MPa, 25 °C | inactivation | [72] | |

| Pineapples | 200–600 MPa, 30–70 °C, 5–20 min | 25% and 70% maximum inactivation at 600 MPa for 20 min and 30 and 70 °C, respectively | [67] | |

| Feijoas | 200–600 MPa, 1–13 min, room temperature | Maximum 30% inactivation at 600 for 7 min | [66] | |

| Strawberries | 200–600 MPa, 5–15 min, room temperature | Slight activation at 200 MPa, and up to 80% inactivation at 600 MPa for 15 min | [73] | |

| Red raspberries, strawberries | 400–800 MPa, 18 and 22 °C | 30% inactivation at 800 MPa after 15 min treatment in raspberries, total inactivation after 15 min at 600 and 800 MPa and after 10 min at 800 MPa in strawberries | [74] | |

| Strawberry puree | 100–690 MPa, 24–90 °C, 5–15 min | 24% inactivation at 690 MPa and 90 °C for 5 and 15 min | [63] | |

| Strawberries | 300–600 MPa, 20–60 °C, 2–10 min | Maximum 29% inactivation at 600 MPa for 10 min and 60 °C | [62] | |

| Strawberries 3 cultivars | 600 MPa, 20 °C, 5 min | 20%–40% of inactivation depending on cultivar | [64] | |

| Strawberry puree with 10% of sugar | 200–600 MPa, 40–80 °C, 2.5–10 min | Maximum 50% inactivation | [75] | |

| Strawberry pulp | 400–600 MPa, 5–25 min, room temperature | 51% inactivation at 600 MPa for 25 min | [65] | |

| Strawberry puree | 50–400 MPa, 20–60 °C | 60% inactivation under 250 MPa and 20 °C, | [61] | |

| Strawberry puree | 300–500 MPa, 0–50 °C, 5–15 min | 72% inactivation at 500 MPa, 15 min, 50 °C | [13] | |

| Strawberry puree | 300–600 MPa, 50 °C, 15 min | 58% and 41% of inactivation at 300 and 600 MPa, 15 min, 50 °C, respectively | [76] | |

| Spinach | 700 MPa, 20 °C, 15 min | 86% inactivation | [77] | |

| Mango pulp | 400–600 MPa, 40–60 °C, 5–15 min | Up to 63% inactivation at the harshest conditions | [78] | |

| Blueberry | 0.1–700 MPa, 30–80 °C | Up to 6 fold increase activity at 500 MPa and 30 °C, significant decrease at minimum 500 MPa and temperature over 76 °C | [79] | |

| Pumpkin puree | 300–900 MPa, 60–80 °C, 1 min | Up to 60% inactivation at 900 MPa and 70 °C | [80] | |

| Cloudy apple juice | 600 MPa, 3 min | Up to 50% inactivation | [81] | |

| Wild berries | 200–600 MPa, room temperature, 5–30 min | Up to 3 fold increase activity at 200 MPa, 5 min and insignificant inactivation at harshest conditions | [82] | |

| Beet root | 650 MPa, 3–30 min | 10%–25% inactivation depending on time | [83] | |

| Peach | 600 MPa, 20–100 °C, 3–5 min | 68% inactivation at 20 °C for 5 min and 90% inactivation at 80–100 °C after 3 min | [84] | |

| POD | Strawberries | 400–800 MPa, 18 and 22 °C | 11%–35% inactivation at 600 MPa for 15 min in strawberries | [74] |

| Strawberry puree | 100–690 MPa, 24–90 °C, 5–15 min | 97% inactivation at 100 MPa and 90 °C for 15 min, 35% inactivation at the same pressure and the lowest temperature | [63] | |

| Strawberries | 300–600 MPa, 20–60 °C, 2–10 min | Maximum 59% inactivation at 600 MPa for 2 min and 60 °C | [62] | |

| Strawberries of three cultivars | 600 MPa, 20 °C, 5 min | 40% inactivation | [64] | |

| Strawberry puree | 50–400 MPa, 20–60 °C | 50% inactivation under 230 MPa and 43 °C | [61] | |

| Strawberry pulp | 400–600 MPa, 5–25 min, room temperature | 74% inactivation at 600 MPa for 25 min | [65] | |

| Pineapples | 200–600 MPa, 30–70 °C, 5–20 min | 25% and 80% maximum inactivation at 600 MPa for 20 min and 30 and 70 °C, respectively | [67] | |

| Feijoas | 200–600 MPa, 1–13 min, room temperature | Maximum 24% inactivation at 400 for 13 min and 600 MPa for 7 min | [66] | |

| Strawberry puree | 300–500 MPa, 0–50 °C, 5–15 min | 50% inactivation at 500 MPa, 15 min, 50 °C | [13] | |

| Strawberry puree | 300–600 MPa, 50 °C, 15 min | 31% and 83% inactivation at 300 and 600 MPa, 15 min, 50 °C, respectively | [76] | |

| Spinach | 700 MPa, 20 °C, 15 min | 77% inactivation | [77] | |

| Mango pulp | 400–600 MPa, 40–60 °C, 5–15 min | Up to 67% inactivation at the harshest conditions | [78] | |

| Cloudy apple juice | 600 MPa, 3 min | Up to 50% inactivation | [81] | |

| Wild berries | 200–600 MPa, room temperature, 5–30 min | Up to 3 fold increase activity at 200 MPa, 5 min and insignificant inactivation at harshest conditions | [82] | |

| Beet root | 650 MPa, 3–30 min | Up to 25% inactivation | [83] | |

| Peach | 600 MPa, 20–100 °C, 3–5 min | 26% inactivation at 20 °C for 5 min and 92% inactivation at 80–100 °C after 3 min | [84] | |

| β-GLC | Red raspberries, strawberries | 400–800 MPa, 18 and 22 °C | 10% inactivation at 600 and 800 MPa for 15 min in raspberries, 50% and 60% reduction at 600 and 800 MPa for 15 min in strawberries | [74] |

| Strawberry pulp | 400–600 MPa, 5–25 min, room temperature | 41% inactivation at 600 MPa for 25 min | [65] | |

| Strawberries | 200–800 MPa, room temperature, 15 min | Increase of about 50% and 70% at 200 and 400 MPa, decrease of about 50% and 65% at 600 and 800 MPa. | [85] |

| Source | Anthocyanin Studied | Processing Conditions | Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orange juice | Cy-3-glc | 400–600 MPa for 15 min at 20 °C | 99% retention of Cy-3-glc at 600 MPa | [1] |

| Pure anthocyanin | Cy-3-glc | 200, 600 MPa at 25 °C and 70 °C for up to 6 h | Insignificant changes at 200 MPa and 70 °C, 25% loss of Cy-3-glc after 30 min at 600 MPa and 70 °C, 53% loss after 6 h at the same parameters | [106] |

| Blueberries | Total anthocyanins content | 200–600 MPa, 5–15 min, 25 °C | Insignificant changes | [107] |

| Pomegranate juice | Total anthocyanins content | 400–600 MPa, 25–50 °C, 5–10 min | Slight decrease progressing with increasing the pressure and temperature | [108] |

| Strawberry and wild berry mousses, pomegranate juice | Total anthocyanins content | 500 MPa, 50 °C, 10 min for mousses, 400 MPa, 25 °C, 5 min for juice | 90% retention in strawberry and wild berry mousses and 37% of losses in pomegranate juice | [104] |

| Strawberry pulps | Cy-3-glc Pg-3-glc Pg-3-rut | 400–600 MPa, 5–25 min, room temperature | Insignificant changes of Cy-3-glc and Pg-3-glc, 6% loss of Pg-3-rut at 400 MPa, 10 min | [65] |

| Strawberries 3 cultivars | Cy-3-glc Pg-3-glc Pg-3-rut | 600 MPa, 20 °C, 5 min | 20%–28% losses depending on the strawberry cultivar | [64] |

| Strawberry and raspberry pastes and juices | Cy-3-glc Pg-3-glc Pg-3-ara Cy-3-soph Cy-3-rut | 400–700 MPa, 20–110 °C, 20 min | Up to 23% changes at temperature below 80 °C and ca. 80% losses at temperature over 80 °C | [105] |

| Strawberry paste | Cy-3-rut | 200–700 MPa, 80–110 °C, up to 50 min | Increasing the pressure accelerated degradation from 1.7 to 2.4 times (depending on the temperature), increasing the temperature accelerated degradation from 5.0 to 6.0 times (depending on the pressure) | [7] |

| Strawberries | Total anthocyanins content | 300–600 MPa, 20–60 °C, 2–10 min | Insignificant changes | [62] |

| Strawberry puree | 14 different anthocyanins compounds and their condensed pigments | 100–400 MPa, 20–50 °C, 15 min | Insignificant changes | [109] |

| Strawberry puree | Cy-3-glc Pg-3-glc Pg-3-rut | 300–500 MPa, 0–50 °C, 5–15 min | 8% losses at 0 °C and 15% at 50 °C, insignificant influence of pressure and time | [13] |

| Strawberry puree | Cy-3-glc Pg-3-glc Pg-3-rut | 300–600 MPa, 50 °C, 15 min | Up to 20% losses at 600 MPa | [76] |

| Source | Anthocyanin Studied | Processing Conditions | Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure anthocyanin | cyanidin-3-glucoside | 70 °C for up to 6 h | 5% loss after 30 min, 25% loss after 6 h | [106] |

| Strawberry pulp | cyanidin-3-glucoside, pelargonidin-3-glucoside, pelargonidin-3-rutinoside | 70 °C, 2 min | 20% loss of total anthocyanins | [65] |

| Strawberries | cyanidin-3-glucoside, pelargonidin-3-glucoside, pelargonidin-3-rutinoside | 88 °C, 2 min | 22%–25% loss of total anthocyanins | [64] |

| Strawberry and raspberry pastes and juices | cyanidin-3-glucoside, pelargonidin-3-glucoside, pelargonidin-3-arabinoside | 80–140 °C, 20 min | Significant degradation of all monomer, at 140 °C almost total degradation of anthocyanins | [105] |

| Strawberry paste | cyanidin-3-glucoside | 95–130 °C, up to 50 min | Increasing the temperature from 95 to 130 °C increased Cy-3-Glc degradation 15× | [7] |

| Strawberry puree | cyanidin-3-glucoside, pelargonidin-3-glucoside, pelargonidin-3-rutinoside | 90 °C, 15 min | 43% losses | [13] |

| Source | Anthocyanin Studied | Processing/Storage Conditions | Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raspberries | Cy-3-glc Cy-3-Soph | 200–800 MPa, 18–22 °C, 15 min, Storage : 4, 20, 30 °C for 9 days | Greater stability at 800 MPa for Cy-3-glc and Cy-3-Soph at 4 °C of storage | [120] |

| Blackcurrants | Dp-3-rut Cy-3-rut | 200–800 MPa, 18–22 °C, 15 min, Storage: 5, 20, 30 °C for 7 days | Greater stability at 600 MPa for Cy-3-rut and 800 MPa for Dp-3-rut at 5 °C of storage | [118] |

| Muscadine grape juice | Delphinidin-3, 5-diglucoside, Petunidin-3,5-diglucoside, Peonidin-3,5-diglucoside, Malvidin-3,5-diglucoside | 400 and 550 MPa for 15 min, Storage: 25 °C for 21 days | 28%–34% losses at 25 °C of storage | [122] |

| Orange juice | Cy-3-glc | 400–600 MPa for 15 min at 20 °C, Storage : 4 and 20 °C for 10 days | 93% and 89% retention at 600 MPa in juice stored at 4 and 20 °C | [1] |

| Strawberry and wild berry mousses, pomegranate juice | Total anthocyanins content | 500 MPa, 50 °C, 10 min for mousses, 400 MPa, 25 °C, 5 min for juice, Storage: 4 and 25 °C for 72 days | 35%–37% of losses for both products | [104] |

| Strawberries | Cy-3-glc Pg-3-glc Pg-3-rut | 600 MPa, 20 °C, 5 min, Storage: 4 °C for 3 months | 19%–25% retention after 3 month of storage | [64] |

| Strawberry cloudy and clear juices | Cy-3-glc Pg-3-glc Pg-3-rut | 600 MPa, room temperature, 4 min, Storage: 4 and 25 °C for 6 months | 30% and 7% losses in cloudy and clear juices | [123] |

| Strawberries | Pg-3-glc Pg-3-rut | 200–800 MPa, 18–22 °C, 15 min, Storage: 4, 20, 30 °C for 9 days | Greatest stability after processing at 800 MPa; storage at 4 °C | [119] |

| Strawberry puree | Cy-3-glc Pg-3-glc Pg-3-rut | 300–600 MPa, 50 °C, 15 min, Storage: 6 °C for 4 and 28 weeks for 300 and 600 MPa, respectively | fastest degradation after processing at 600 MPa compared to 300 MPa, half-life: 62 and 86 days, respectively for 600 and 300 MPa, the lowest stability of Pg-3-rut | [76] |

| Strawberry puree | Cy-3-glc Pg-3-glc Pg-3-rut | 500 MPa, 50 °C, 15 min, Storage: 6 °C for 12 weeks | 73% degradation of TCA, the lowest stability of Pg-3-rut | [124] |

| Strawberry | Total anthocyanins content | 400 MPa, room temperature, 5 min, Storage: 4 and 25 °C for 45 days | 33% and 57% degradation in samples stored at 4 and 25 °C | [125] |

| Bayberry juice | Cy-3-glc | 400–600 MPa, room temperature, 10 min, Storage: 4 and 25 °C for 25 days | 8% degradation in samples stored at 4 and significantly higher in samples stored at 25 °C | [126] |

| Pomegranate juice | Total anthocyanins content | 300–400 MPa, room temperature, 2.5–25 min, Storage: 4 °C for 90 days | 25% degradation | [127] |

| Aronia juice | - | 200–600 MPa, room temperature, 15 min, Storage 4 °C for 80 days | Ca. 40% degradation at 600 MPa | [128] |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marszałek, K.; Woźniak, Ł.; Kruszewski, B.; Skąpska, S. The Effect of High Pressure Techniques on the Stability of Anthocyanins in Fruit and Vegetables. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 277. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18020277

Marszałek K, Woźniak Ł, Kruszewski B, Skąpska S. The Effect of High Pressure Techniques on the Stability of Anthocyanins in Fruit and Vegetables. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2017; 18(2):277. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18020277

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarszałek, Krystian, Łukasz Woźniak, Bartosz Kruszewski, and Sylwia Skąpska. 2017. "The Effect of High Pressure Techniques on the Stability of Anthocyanins in Fruit and Vegetables" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 18, no. 2: 277. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18020277