Preventive Effects of Tryptophan–Methionine Dipeptide on Neural Inflammation and Alzheimer’s Pathology

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Effects of WM Peptide on Aβ Deposition in 5×FAD Mice

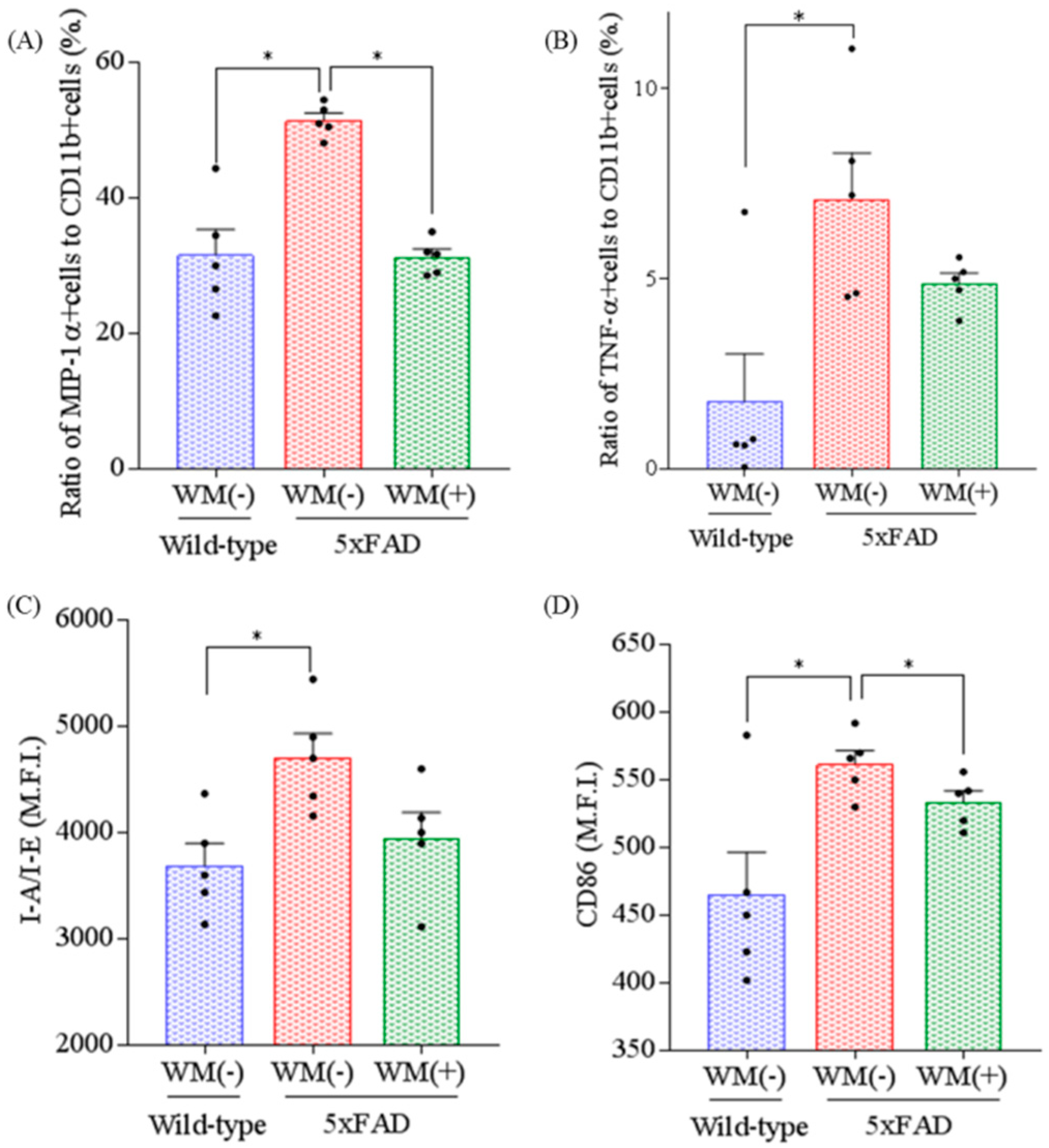

2.2. Effects of WM Peptide on Inflammation and Microglial Activation in 5×FAD Mice

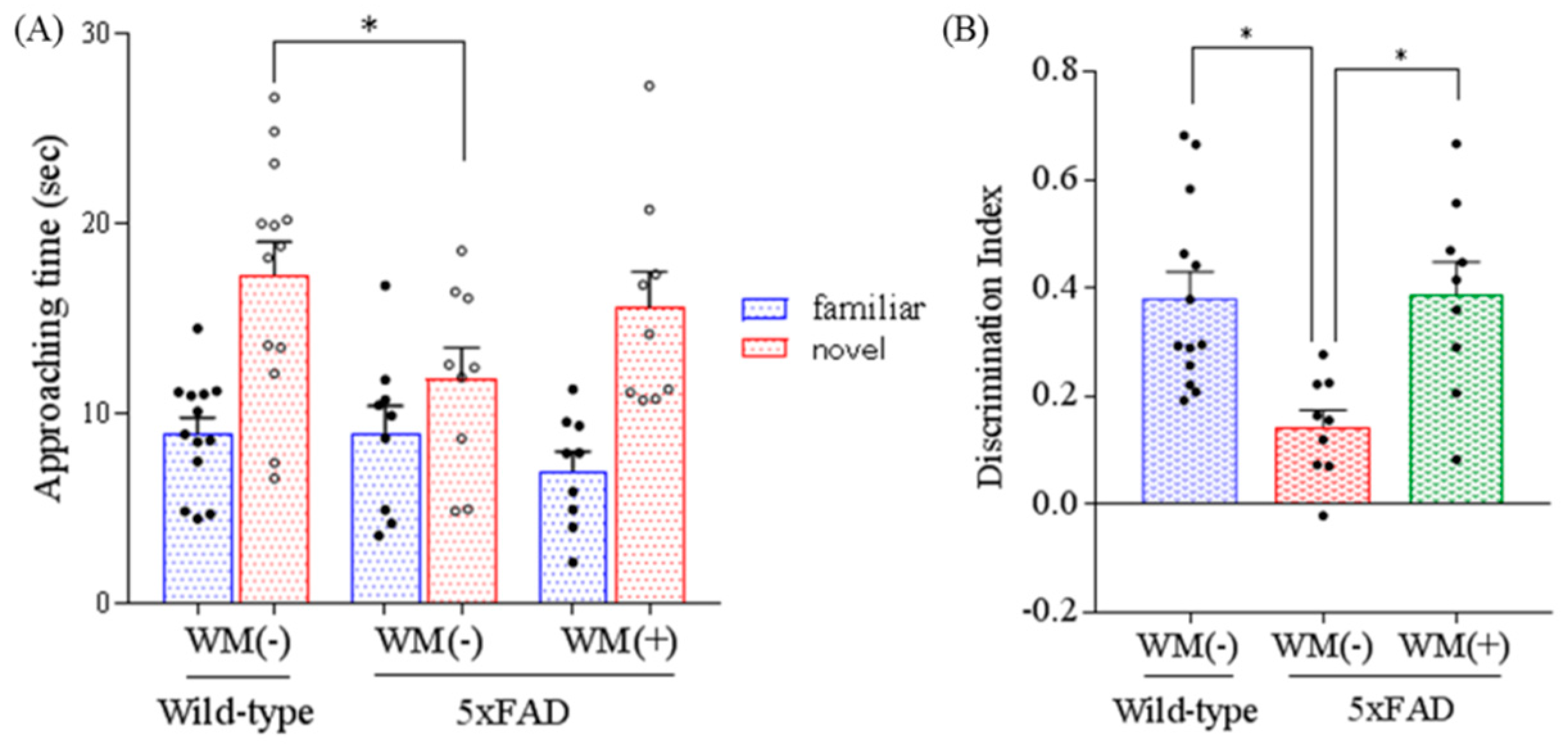

2.3. Effects of WM Peptide on Memory Impairment in 5×FAD Mice

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals

4.2. Quantification of Cytokine and Aβ by ELISA

4.3. Immunohistochemistry

4.4. Characterization of Microglia Using Flow Cytometry

4.5. Novel Object Recognition Test

4.6. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Aβ | amyloid beta |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| ELISA | enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| FAD | familial Alzheimer’s disease |

| IL | Interleukin |

| LM-1 | logical memory 1 |

| LPS | lipopolysaccharide |

| MACS | magnetic cell sorting |

| MIP-1α | macrophage inflammatory protein-1α |

| NFT | neurofibrillary tangle |

| TBS | Tris-buffered saline |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor α |

| WM | Tryptophan–methionine |

| WY | Tryptophan–tyrosine |

References

- Murphy, M.P.; LeVine, H., III. Alzheimer’s disease and the amyloid-β peptide. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2010, 19, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takashima, A. Amyloid-β, tau, and dementia. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2009, 17, 729–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsumoto, A.; Takeuchi, H.; Takahashi, K.; Tanaka, F. Microglia in Alzheimer’s Disease: Risk Factors and Inflammation. Front. Neurol. 2018, 9, 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinney, J.W.; Bemiller, S.M.; Murtishaw, A.S.; Leisgang, A.M.; Salazar, A.M.; Lamb, B.T. Inflammation as a central mechanism in Alzheimer’s disease. Alz. Dement. 2018, 4, 575–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.C.; Rizer, J.; Selenica, M.L.; Reid, P.; Kraft, C.; Johnson, A.; Blair, L.; Gordon, M.N.; Dickey, C.A.; Morgan, D. LPS- induced inflammation exacerbates phospho-tau pathology in rTg4510 mice. J. Neuroinflamm. 2010, 7, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, J.; Nutma, E.; van der Valk, P.; Amor, S. Inflammation in CNS neurodegenerative diseases. Immunology 2018, 154, 204–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sarlus, H.; Heneka, M.T. Microglia in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Clin. Invest. 2017, 127, 3240–3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ano, Y.; Nakayama, H. Preventive Effects of Dairy Products on Dementia and the Underlying Mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camfield, D.A.; Owen, L.; Scholey, A.B.; Pipingas, A.; Stough, C. Dairy constituents and neurocognitive health in ageing. Br. J. Nutr. 2011, 106, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ozawa, M.; Ninomiya, T.; Ohara, T.; Doi, Y.; Uchida, K.; Shirota, T.; Yonemoto, K.; Kitazono, T.; Kiyohara, Y. Dietary patterns and risk of dementia in an elderly Japanese population: The Hisayama Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 97, 1076–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozawa, M.; Ohara, T.; Ninomiya, T.; Hata, J.; Yoshida, D.; Mukai, N.; Nagata, M.; Uchida, K.; Shirota, T.; Kitazono, T.; et al. Milk and dairy consumption and risk of dementia in an elderly Japanese population: The Hisayama Study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2014, 62, 1224–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogata, S.; Tanaka, H.; Omura, K.; Honda, C.; Osaka Twin Research, G.; Hayakawa, K. Association between intake of dairy products and short-term memory with and without adjustment for genetic and family environmental factors: A twin study. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 35, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kita, M.; Kobayashi, K.; Obara, K.; Koikeda, T.; Umeda, S.; Ano, Y. Supplementation with Whey Peptide Rich in β-Lactolin Improves Cognitive Performance in Healthy Older Adults: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ano, Y.; Ozawa, M.; Kutsukake, T.; Sugiyama, S.; Uchida, K.; Yoshida, A.; Nakayama, H. Preventive effects of a fermented dairy product against Alzheimer’s disease and identification of a novel oleamide with enhanced microglial phagocytosis and anti-inflammatory activity. PloS ONE 2015, 10, e0118512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ano, Y.; Yoshino, Y.; Kutsukake, T.; Ohya, R.; Fukuda, T.; Uchida, K.; Takashima, A.; Nakayama, H. Tryptophan-related dipeptides in fermented dairy products suppress microglial activation and prevent cognitive decline. Aging 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, K.; Hikida, A.; Kawai, S.; Lan, V.T.; Motoyama, T.; Kitagawa, S.; Yoshikawa, Y.; Kato, R.; Kawarasaki, Y. Analysing the substrate multispecificity of a proton-coupled oligopeptide transporter using a dipeptide library. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ano, Y.; Ayabe, T.; Ohya, R.; Kondo, K.; Kitaoka, S.; Furuyashiki, T. Tryptophan-Tyrosine Dipeptide, the Core Sequence of β-Lactolin, Improves Memory by Modulating the Dopamine System. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ano, Y.; Ayabe, T.; Kutsukake, T.; Ohya, R.; Takaichi, Y.; Uchida, S.; Yamada, K.; Uchida, K.; Takashima, A.; Nakayama, H. Novel lactopeptides in fermented dairy products improve memory function and cognitive decline. Neurobiol. Aging 2018, 72, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagatsu, T.; Sawada, M. Molecular mechanism of the relation of monoamine oxidase B and its inhibitors to Parkinson’s disease: Possible implications of glial cells. J. Neural. Trans. Suppl. 2006, 53–65. [Google Scholar]

- Son, B.; Jun, S.Y.; Seo, H.; Youn, H.; Yang, H.J.; Kim, W.; Kim, H.K.; Kang, C.; Youn, B. Inhibitory effect of traditional oriental medicine-derived monoamine oxidase B inhibitor on radioresistance of non-small cell lung cancer. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 21986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miwa, M.; Tsuboi, M.; Noguchi, Y.; Enokishima, A.; Nabeshima, T.; Hiramatsu, M. Effects of betaine on lipopolysaccharide-induced memory impairment in mice and the involvement of GABA transporter 2. J. Neuroinflamm. 2011, 8, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fruhauf, P.K.; Ineu, R.P.; Tomazi, L.; Duarte, T.; Mello, C.F.; Rubin, M.A. Spermine reverses lipopolysaccharide-induced memory deficit in mice. J. Neuroinflamm. 2015, 12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parbo, P.; Ismail, R.; Hansen, K.V.; Amidi, A.; Marup, F.H.; Gottrup, H.; Braendgaard, H.; Eriksson, B.O.; Eskildsen, S.F.; Lund, T.E.; et al. Brain inflammation accompanies amyloid in the majority of mild cognitive impairment cases due to Alzheimer’s disease. Brain J. Neurol. 2017, 140, 2002–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imbimbo, B.P.; Solfrizzi, V.; Panza, F. Are NSAIDs useful to treat Alzheimer’s disease or mild cognitive impairment? Front. Aging Neurosci. 2010, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, W.F.; Kawas, C.; Corrada, M.; Metter, E.J. Risk of Alzheimer’s disease and duration of NSAID use. Neurology 1997, 48, 626–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ano, Y.; Dohata, A.; Taniguchi, Y.; Hoshi, A.; Uchida, K.; Takashima, A.; Nakayama, H. Iso-α-acids, Bitter Components of Beer, Prevent Inflammation and Cognitive Decline Induced in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 3720–3728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ano, Y.; Ohya, R.; Kondo, K.; Nakayama, H. Iso-α-acids, Hop-Derived Bitter Components of Beer, Attenuate Age-Related Inflammation and Cognitive Decline. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2019, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ano, Y.; Yoshikawa, M.; Takaichi, Y.; Michikawa, M.; Uchida, K.; Nakayama, H.; Takashima, A. Iso-α-Acids, Bitter Components in Beer, Suppress Inflammatory Responses and Attenuate Neural Hyperactivation in the Hippocampus. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ano, Y.; Takaichi, Y.; Uchida, K.; Kondo, K.; Nakayama, H.; Takashima, A. Iso-α-Acids, the Bitter Components of Beer, Suppress Microglial Inflammation in rTg4510 Tauopathy. Molecules 2018, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunan, J.; Small, D.H. Regulation of APP cleavage by α-, β- and γ-secretases. FEBS Lett. 2000, 483, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakley, H.; Cole, S.L.; Logan, S.; Maus, E.; Shao, P.; Craft, J.; Guillozet-Bongaarts, A.; Ohno, M.; Disterhoft, J.; Van Eldik, L.; et al. Intraneuronal beta-amyloid aggregates, neurodegeneration, and neuron loss in transgenic mice with five familial Alzheimer’s disease mutations: Potential factors in amyloid plaque formation. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 10129–10140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ano, Y.; Hoshi, A.; Ayabe, T.; Ohya, R.; Uchida, S.; Yamada, K.; Kondo, K.; Kitaoka, S.; Furuyashiki, T. Iso-α-acids, the bitter components of beer, improve hippocampus-dependent memory through vagus nerve activation. FASEB J. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Item | Wild-Type | 5×FAD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| WM(−) | WM(−) | WM(+) | |

| IL-1β | 6.55 ± 0.62 | 12.06 ± 0.92 * | 8.88 ± 1.07 † |

| TNF-α | 10.02 ± 1.78 | 14.72 ± 0.84 * | 11.30 ± 1.04 † |

| IL-6 | 0.27 ± 0.03 | 0.35 ± 0.04 * | 0.23 ± 0.06 † |

| IL-12p40 | 2.06 ± 0.23 | 2.49 ± 0.12 * | 2.16 ± 0.32 |

| IL-12p70 | 1.09 ± 0.19 | 1.32 ± 0.09 * | 1.18 ± 0.22 |

| MIP-1α | 3.99 ± 1.26 | 35.87 ± 4.16 ** | 22.67 ± 3.47 †† |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ano, Y.; Yoshino, Y.; Uchida, K.; Nakayama, H. Preventive Effects of Tryptophan–Methionine Dipeptide on Neural Inflammation and Alzheimer’s Pathology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3206. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20133206

Ano Y, Yoshino Y, Uchida K, Nakayama H. Preventive Effects of Tryptophan–Methionine Dipeptide on Neural Inflammation and Alzheimer’s Pathology. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2019; 20(13):3206. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20133206

Chicago/Turabian StyleAno, Yasuhisa, Yuka Yoshino, Kazuyuki Uchida, and Hiroyuki Nakayama. 2019. "Preventive Effects of Tryptophan–Methionine Dipeptide on Neural Inflammation and Alzheimer’s Pathology" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 20, no. 13: 3206. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20133206

APA StyleAno, Y., Yoshino, Y., Uchida, K., & Nakayama, H. (2019). Preventive Effects of Tryptophan–Methionine Dipeptide on Neural Inflammation and Alzheimer’s Pathology. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 20(13), 3206. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20133206