Endothelial Ca2+ Signaling, Angiogenesis and Vasculogenesis: Just What It Takes to Make a Blood Vessel

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Growth Factors and Chemokines Induce Pro-Angiogenic Ca2+ Signals in Vascular Endothelial Cells

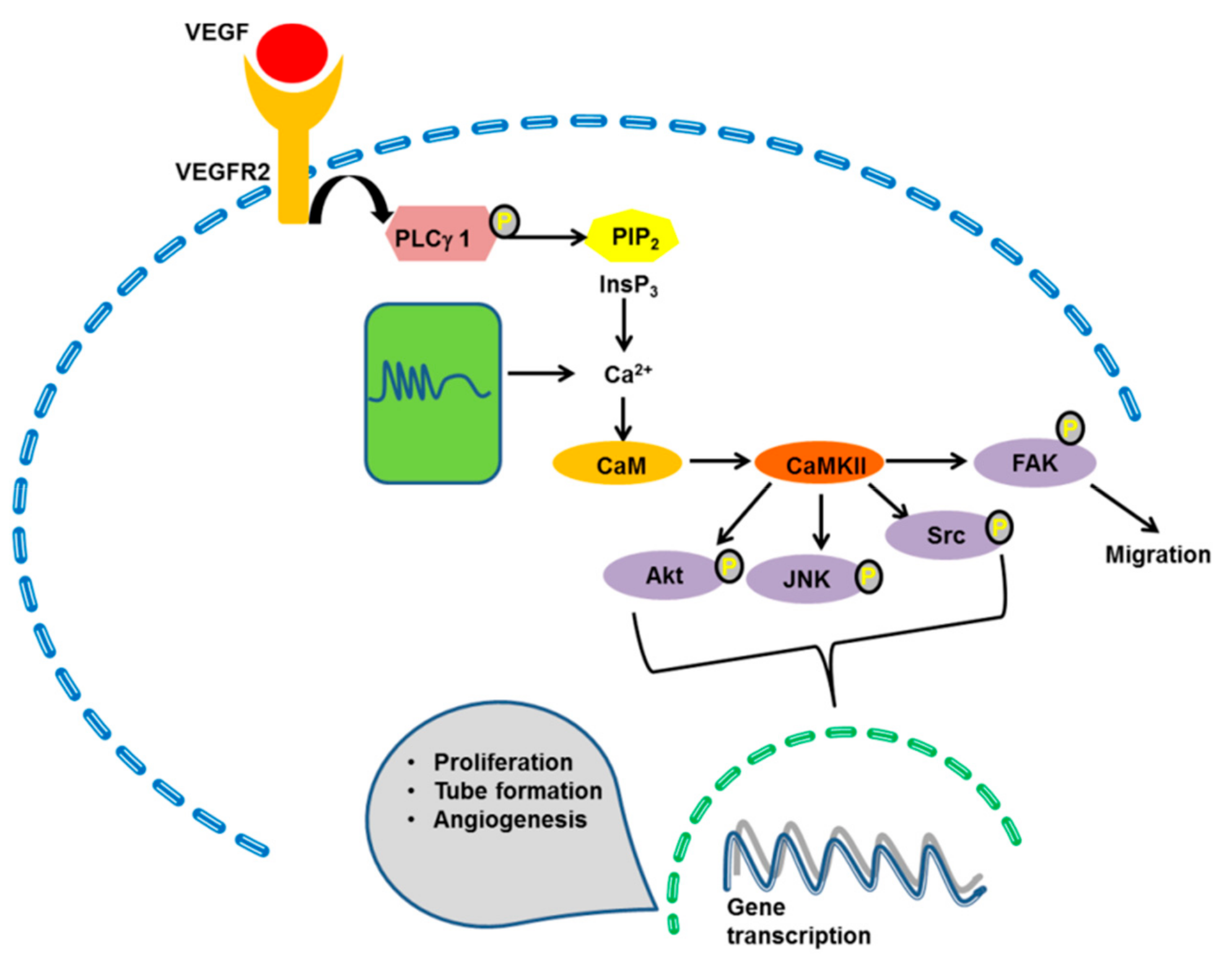

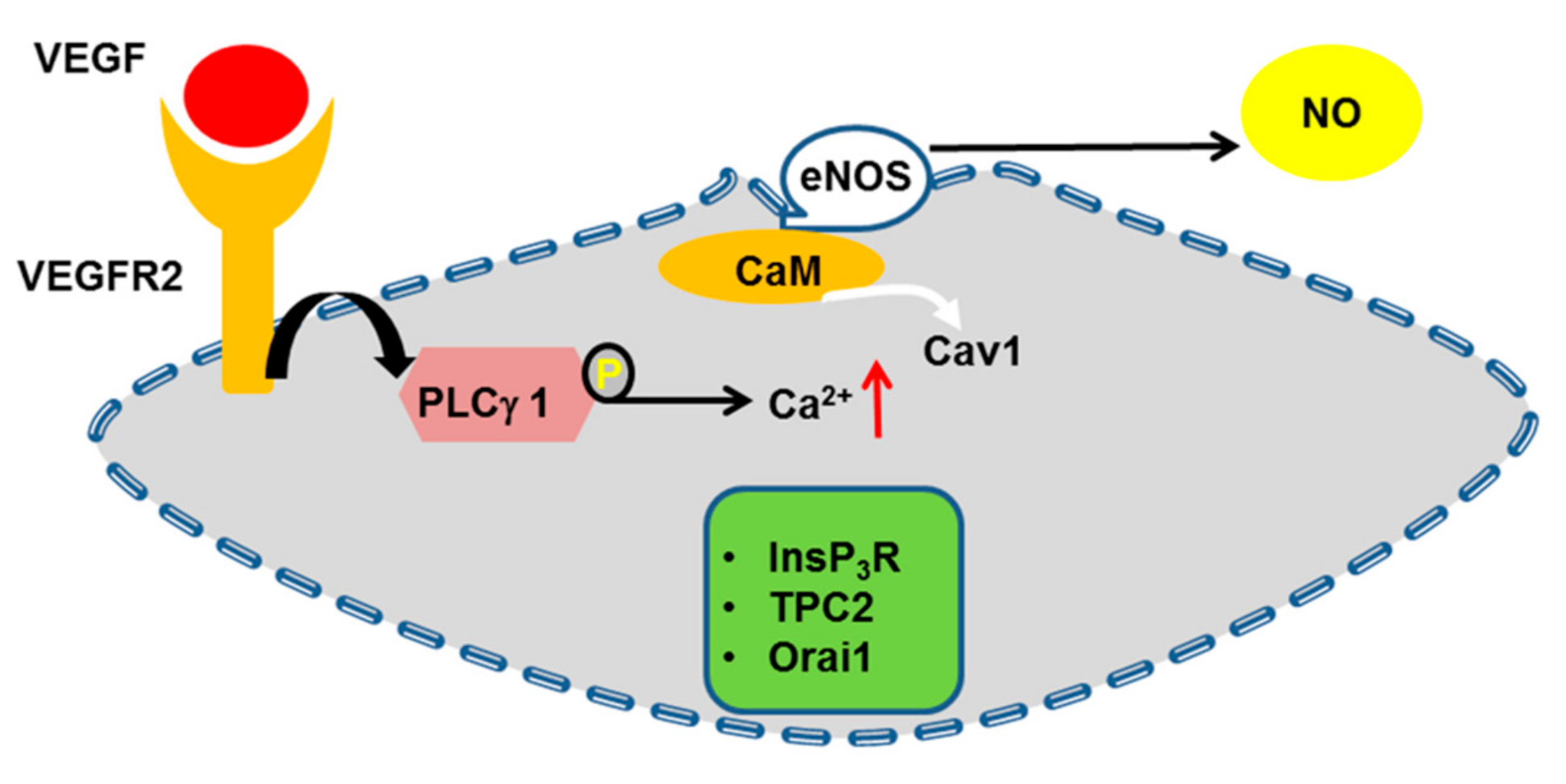

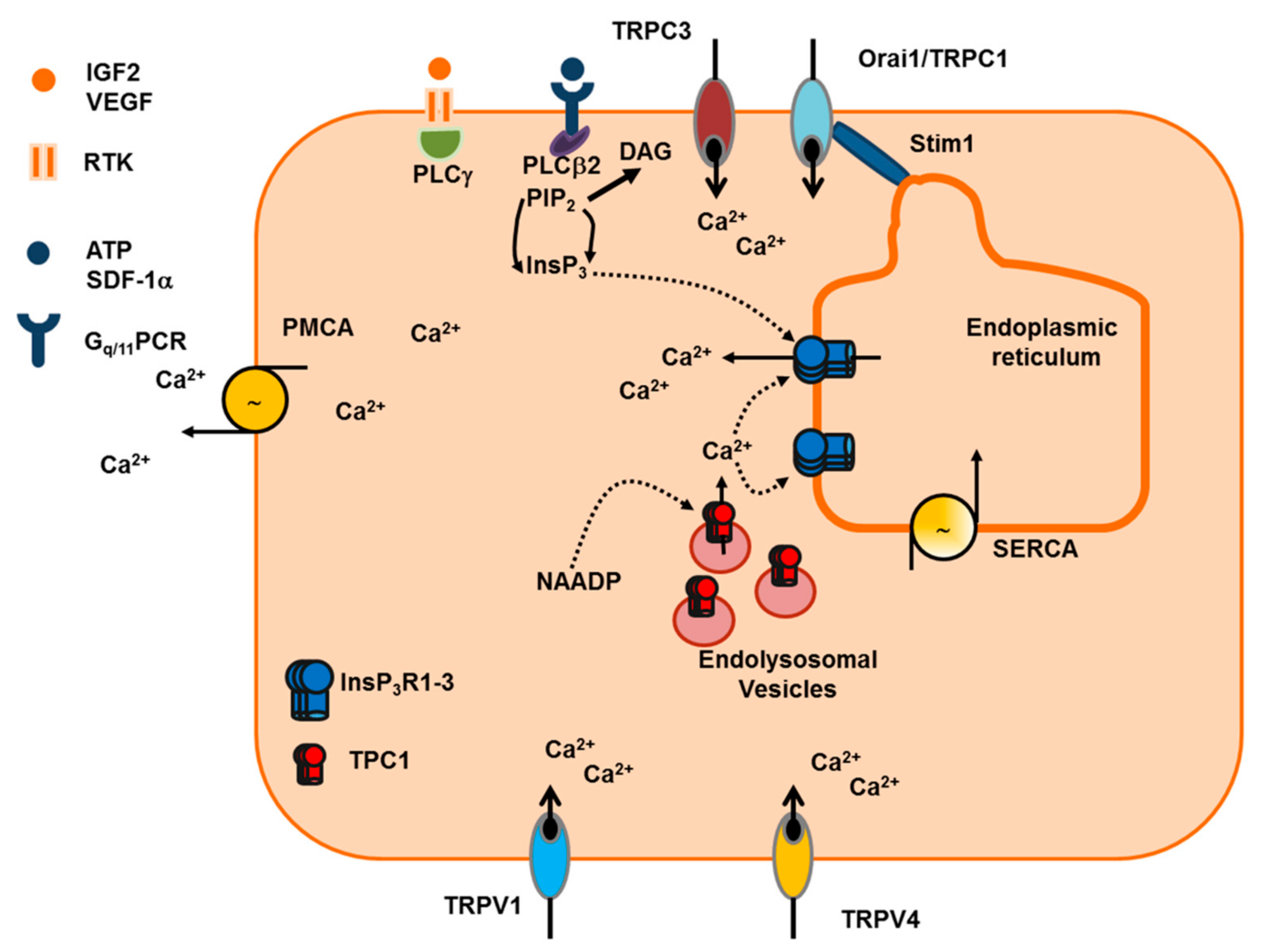

2.1. The Endothelial Ca2+ Toolkit Recruited by Growth Factors and Chemokines to Stimulate Angiogenesis

2.1.1. The Onset of Pro-Angiogenic Ca2+ Signals: PLCβ and PLCγ

2.1.2. Endogenous Ca2+ Release Induced by Pro-Angiogenic Cues: InsP3 Receptors (InsP3R), Ryanodine Receptors (RyR) and Two-Pore Channels (TPC)

2.1.2.1. InsP3R

2.1.2.2. RyR

2.1.2.3. TPC

2.1.3. Extracellular Ca2+ Entry Induced by Pro-Angiogenic Cues in Vascular Endothelial Cells: Store-Operated Ca2+ Entry (SOCE), STIM1 and Orai1, and TRPC

2.1.3.1. SOCE: STIM1 and Orai1

2.1.3.2. SOCE: STIM2 and Orai2-3

2.1.3.3. SOCE: TRPC1 and TRPC4

3. Pro-Angiogenic Ca2+ Signals in Vascular Endothelial Cells

3.1. VEGF-Induced Intracellular Ca2+ Signals in Vascular Endothelial Cells

3.2. VEGF-Induced Intracellular Ca2+ Signals in HUVEC

3.3. VEGF-Induced Intracellular Ca2+ Signals in Other Vascular Endothelial Cell Types: In Vitro and In Vivo Evidences

3.4. Modulation of VEGF-Induced Endothelial Ca2+ Signals

3.5. Endothelial Ca2+ Signals Induced by bFGF, Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF), PDGF, and SDF-1α

3.6. Endothelial Ca2+ Signals Induced by Angiopoietins (ANG)

4. The Ca2+-Dependent Decoders of Angiogenesis

4.1. The ERK 1/2 Pathway

4.2. The PI3K/Akt Pathway

4.3. Calcineurin and NFAT

4.4. CaMKII

4.5. MLCK, Calpain and Proline-Rich Tyrosine Kinase-2 (Pyk2)

| Signal | EC | InsP3R | RyR | TPC | STIM1/Ora1 | TRPC1/TRPC4 | TRPC3/TRPC6 | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VEGF | HUVEC | Yes | N.I. | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | [73,76,77,104,122,123,124,163,164] |

| VEGF | EA.hy926 | Yes | N.I. | N.I. | No | No | No | [165] |

| VEGF | HAEC | Yes | Yes | N.I. | Yes | N.I. | N.I. | [48] |

| VEGF | Zebrafish tip cells | Yes | N.I. | Yes | N.I. | N.I. | N.I. | [26] |

| bFGF | HUVEC | Yes | N.I. | N.I. | Yes | N.I. | N.I | [203,205,223,260] |

| EGF | CMEC | Yes | No | N.I. | Yes | N.I. | N.I. | [209] |

| ANG | HUVEC | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | [217] |

| Angiostatin | BAEC | Yes | N.I. | N.I. | N.I. | N.I. | N.I. | [192] |

| Endostatin | BAEC | Yes | N.I. | N.I. | N.I. | N.I. | N.I. | [192] |

4.6. eNOS

4.7. Non-Canonical Wnt/Ca2+ Signaling Pathway

5. The Role of Ca2+ Signaling in Vasculogenesis

5.1. The Ca2+ Toolkit in Human ECFC: Endogenous Ca2+ Release and Extracellular Ca2+ Entry

5.2. IGF-2 and SDF-1α Stimulate ECFC Homing to Hypoxic Tissues through an Increase in [Ca2+]i

5.3. VEGF and NAADP Stimulate Proliferation and Tube Formation through an Increase in [Ca2+]i in ECFC

5.4. VEGF-Induced Intracellular Ca2+ Oscillations Are Down-Regulated in Tumor-Derived ECFC

5.5. The Ca2+ Toolkit in Rodent MAC

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Herbert, S.P.; Stainier, D.Y. Molecular control of endothelial cell behaviour during blood vessel morphogenesis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011, 12, 551–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ramasamy, S.K.; Kusumbe, A.P.; Adams, R.H. Regulation of tissue morphogenesis by endothelial cell-derived signals. Trends Cell Biol. 2015, 25, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aird, W.C. Spatial and temporal dynamics of the endothelium. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2005, 3, 1392–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galley, H.F.; Webster, N.R. Physiology of the endothelium. Br. J. Anaesth. 2004, 93, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cahill, P.A.; Redmond, E.M. Vascular endothelium—Gatekeeper of vessel health. Atherosclerosis 2016, 248, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafii, S.; Butler, J.M.; Ding, B.S. Angiocrine functions of organ-specific endothelial cells. Nature 2016, 529, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Carmeliet, P.; Jain, R.K. Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of angiogenesis. Nature 2011, 473, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ribatti, D.; Crivellato, E. “Sprouting angiogenesis”, a reappraisal. Dev. Biol. 2012, 372, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoder, M.C. Human endothelial progenitor cells. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012, 2, a006692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoder, M.C. Endothelial stem and progenitor cells (stem cells): (2017 Grover Conference Series). Pulm. Circ. 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alessio, A.; Moccia, F.; Li, J.H.; Micera, A.; Kyriakides, T.R. Angiogenesis and Vasculogenesis in Health and Disease. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 126582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wietecha, M.S.; Cerny, W.L.; DiPietro, L.A. Mechanisms of vessel regression: Toward an understanding of the resolution of angiogenesis. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2013, 367, 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, C.; Schneider, M.; Carmeliet, P. Principles and therapeutic implications of angiogenesis, vasculogenesis and arteriogenesis. In The Vascular Endothelium II, Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; Volume 176, pp. 157–212. [Google Scholar]

- Potente, M.; Gerhardt, H.; Carmeliet, P. Basic and therapeutic aspects of angiogenesis. Cell 2011, 146, 873–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moccia, F.; Lodola, F.; Dragoni, S.; Bonetti, E.; Bottino, C.; Guerra, G.; Laforenza, U.; Rosti, V.; Tanzi, F. Ca2+ signalling in endothelial progenitor cells: A novel means to improve cell-based therapy and impair tumour vascularisation. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2014, 12, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moccia, F.; Tanzi, F.; Munaron, L. Endothelial remodelling and intracellular calcium machinery. Curr. Mol. Med. 2014, 14, 457–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munaron, L. Intracellular calcium, endothelial cells and angiogenesis. Recent Pat. Anticancer Drug Discov. 2006, 1, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moccia, F.; Berra-Romani, R.; Tanzi, F. Update on vascular endothelial Ca2+ signalling: A tale of ion channels, pumps and transporters. World J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 3, 127–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moccia, F.; Guerra, G. Ca2+ Signalling in Endothelial Progenitor Cells: Friend or Foe? J. Cell. Physiol. 2016, 231, 314–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moccia, F.; Poletto, V. May the remodeling of the Ca2+ toolkit in endothelial progenitor cells derived from cancer patients suggest alternative targets for anti-angiogenic treatment? Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1853, 1958–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smani, T.; Gomez, L.J.; Regodon, S.; Woodard, G.E.; Siegfried, G.; Khatib, A.M.; Rosado, J.A. TRP Channels in Angiogenesis and Other Endothelial Functions. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakore, P.; Earley, S. Transient Receptor Potential Channels and Endothelial Cell Calcium Signaling. Compr. Physiol. 2019, 9, 1249–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohn, E.C.; Alessandro, R.; Spoonster, J.; Wersto, R.P.; Liotta, L.A. Angiogenesis: Role of calcium-mediated signal transduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 1307–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simons, M.; Gordon, E.; Claesson-Welsh, L. Mechanisms and regulation of endothelial VEGF receptor signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016, 17, 611–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noren, D.P.; Chou, W.H.; Lee, S.H.; Qutub, A.A.; Warmflash, A.; Wagner, D.S.; Popel, A.S.; Levchenko, A. Endothelial cells decode VEGF-mediated Ca2+ signaling patterns to produce distinct functional responses. Sci. Signal. 2016, 9, ra20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savage, A.M.; Kurusamy, S.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Chhabria, K.; MacDonald, R.B.; Kim, H.R.; Wilson, H.L.; van Eeden, F.J.M.; Armesilla, A.L.; et al. Tmem33 is essential for VEGF-mediated endothelial calcium oscillations and angiogenesis. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patton, A.M.; Kassis, J.; Doong, H.; Kohn, E.C. Calcium as a molecular target in angiogenesis. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2003, 9, 543–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troidl, C.; Nef, H.; Voss, S.; Schilp, A.; Kostin, S.; Troidl, K.; Szardien, S.; Rolf, A.; Schmitz-Rixen, T.; Schaper, W.; et al. Calcium-dependent signalling is essential during collateral growth in the pig hind limb-ischemia model. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2010, 49, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troidl, C.; Troidl, K.; Schierling, W.; Cai, W.J.; Nef, H.; Mollmann, H.; Kostin, S.; Schimanski, S.; Hammer, L.; Elsasser, A.; et al. Trpv4 induces collateral vessel growth during regeneration of the arterial circulation. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2009, 13, 2613–2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrikopoulos, P.; Kieswich, J.; Harwood, S.M.; Baba, A.; Matsuda, T.; Barbeau, O.; Jones, K.; Eccles, S.A.; Yaqoob, M.M. Endothelial Angiogenesis and Barrier Function in Response to Thrombin Require Ca2+ Influx through the Na+/Ca2+ Exchanger. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 18412–18428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kini, V.; Chavez, A.; Mehta, D. A new role for PTEN in regulating transient receptor potential canonical channel 6-mediated Ca2+ entry, endothelial permeability, and angiogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 33082–33091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpellino, G.; Genova, T.; Avanzato, D.; Bernardini, M.; Bianco, S.; Petrillo, S.; Tolosano, E.; de Almeida Vieira, J.R.; Bussolati, B.; Fiorio Pla, A.; et al. Purinergic Calcium Signals in Tumor-Derived Endothelium. Cancers 2019, 11, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avanzato, D.; Genova, T.; Fiorio Pla, A.; Bernardini, M.; Bianco, S.; Bussolati, B.; Mancardi, D.; Giraudo, E.; Maione, F.; Cassoni, P.; et al. Activation of P2X7 and P2Y11 purinergic receptors inhibits migration and normalizes tumor-derived endothelial cells via cAMP signaling. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyubchenko, T.; Woodward, H.; Veo, K.D.; Burns, N.; Nijmeh, H.; Liubchenko, G.A.; Stenmark, K.R.; Gerasimovskaya, E.V. P2Y1 and P2Y13 purinergic receptors mediate Ca2+ signaling and proliferative responses in pulmonary artery vasa vasorum endothelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2011, 300, C266–C275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.W.; Wang, H. Non-neuronal nicotinic alpha 7 receptor, a new endothelial target for revascularization. Life Sci. 2006, 78, 1863–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egleton, R.D.; Brown, K.C.; Dasgupta, P. Angiogenic activity of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: Implications in tobacco-related vascular diseases. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009, 121, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.B.; Su, K.H.; Kou, Y.R.; Guo, B.C.; Lee, K.I.; Wei, J.; Lee, T.S. Role of transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 in regulating erythropoietin-induced activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Acta Physiol. 2017, 219, 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maltaneri, R.E.; Schiappacasse, A.; Chamorro, M.E.; Nesse, A.B.; Vittori, D.C. Participation of membrane calcium channels in erythropoietin-induced endothelial cell migration. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2018, 97, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berra-Romani, R.; Raqeeb, A.; Avelino-Cruz, J.E.; Moccia, F.; Oldani, A.; Speroni, F.; Taglietti, V.; Tanzi, F. Ca2+ signaling in injured in situ endothelium of rat aorta. Cell Calcium 2008, 44, 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berra-Romani, R.; Raqeeb, A.; Torres-Jácome, J.; Guzman-Silva, A.; Guerra, G.; Tanzi, F.; Moccia, F. The mechanism of injury-induced intracellular calcium concentration oscillations in the endothelium of excised rat aorta. J. Vasc. Res. 2012, 49, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moccia, F.; Berra-Romani, R.; Rosti, V. Manipulating Intracellular Ca2+ Signals to Stimulate Therapeutic Angiogenesis in Cardiovascular Disorders. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2018, 19, 686–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berridge, M.J.; Bootman, M.D.; Roderick, H.L. Calcium signalling: Dynamics, homeostasis and remodelling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003, 4, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moccia, F.; Berra-Romani, R.; Baruffi, S.; Spaggiari, S.; Signorelli, S.; Castelli, L.; Magistretti, J.; Taglietti, V.; Tanzi, F. Ca2+ uptake by the endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase in rat microvascular endothelial cells. Biochem. J. 2002, 364, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berra-Romani, R.; Raqeeb, A.; Guzman-Silva, A.; Torres-Jacome, J.; Tanzi, F.; Moccia, F. Na+-Ca2+ exchanger contributes to Ca2+ extrusion in ATP-stimulated endothelium of intact rat aorta. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 395, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurusamy, S.; Lopez-Maderuelo, D.; Little, R.; Cadagan, D.; Savage, A.M.; Ihugba, J.C.; Baggott, R.R.; Rowther, F.B.; Martinez-Martinez, S.; Arco, P.G.; et al. Selective inhibition of plasma membrane calcium ATPase 4 improves angiogenesis and vascular reperfusion. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2017, 109, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggott, R.R.; Alfranca, A.; Lopez-Maderuelo, D.; Mohamed, T.M.; Escolano, A.; Oller, J.; Ornes, B.C.; Kurusamy, S.; Rowther, F.B.; Brown, J.E.; et al. Plasma membrane calcium ATPase isoform 4 inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor-mediated angiogenesis through interaction with calcineurin. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2014, 34, 2310–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evangelista, A.M.; Thompson, M.D.; Bolotina, V.M.; Tong, X.; Cohen, R.A. Nox4-and Nox2-dependent oxidant production is required for VEGF-induced SERCA cysteine-674 S-glutathiolation and endothelial cell migration. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012, 53, 2327–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelista, A.M.; Thompson, M.D.; Weisbrod, R.M.; Pimental, D.R.; Tong, X.; Bolotina, V.M.; Cohen, R.A. Redox regulation of SERCA2 is required for vascular endothelial growth factor-induced signaling and endothelial cell migration. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2012, 17, 1099–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, Y.; Thompson, M.D.; Shiraishi, Y.; Cohen, R.A.; Tong, X. Sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase C674 promotes ischemia-and hypoxia-induced angiogenesis via coordinated endothelial cell and macrophage function. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2014, 76, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.D.; Mei, Y.; Weisbrod, R.M.; Silver, M.; Shukla, P.C.; Bolotina, V.M.; Cohen, R.A.; Tong, X. Glutathione adducts on sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase Cys-674 regulate endothelial cell calcium stores and angiogenic function as well as promote ischemic blood flow recovery. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 19907–19916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malli, R.; Frieden, M.; Osibow, K.; Graier, W.F. Mitochondria efficiently buffer subplasmalemmal Ca2+ elevation during agonist stimulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 10807–10815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malli, R.; Frieden, M.; Osibow, K.; Zoratti, C.; Mayer, M.; Demaurex, N.; Graier, W.F. Sustained Ca2+ transfer across mitochondria is Essential for mitochondrial Ca2+ buffering, sore-operated Ca2+ entry, and Ca2+ store refilling. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 44769–44779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malli, R.; Frieden, M.; Trenker, M.; Graier, W.F. The role of mitochondria for Ca2+ refilling of the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 12114–12122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarron, J.G.; Wilson, C.; Heathcote, H.R.; Zhang, X.; Buckley, C.; Lee, M.D. Heterogeneity and emergent behaviour in the vascular endothelium. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2019, 45, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarron, J.G.; Lee, M.D.; Wilson, C. The Endothelium Solves Problems That Endothelial Cells Do Not Know Exist. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2017, 38, 322–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Beziau, D.M.; Toussaint, F.; Blanchette, A.; Dayeh, N.R.; Charbel, C.; Tardif, J.C.; Dupuis, J.; Ledoux, J. Expression of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C isoforms in native endothelial cells. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0123769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo Vasco, V.R.; Pacini, L.; Di Raimo, T.; D’Arcangelo, D.; Businaro, R. Expression of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C isoforms in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. J. Clin. Pathol. 2011, 64, 911–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozen, E.J.; Roewenstrunk, J.; Barallobre, M.J.; Di Vona, C.; Jung, C.; Figueiredo, A.F.; Luna, J.; Fillat, C.; Arbones, M.L.; Graupera, M.; et al. DYRK1A Kinase Positively Regulates Angiogenic Responses in Endothelial Cells. Cell Rep. 2018, 23, 1867–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Matsui, A.; Okigaki, M.; Amano, K.; Adachi, Y.; Jin, D.; Takai, S.; Yamashita, T.; Kawashima, S.; Kurihara, T.; Miyazaki, M.; et al. Central role of calcium-dependent tyrosine kinase PYK2 in endothelial nitric oxide synthase-mediated angiogenic response and vascular function. Circulation 2007, 116, 1041–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, P.G.; Park, J.I.; Manzoli, L.; Cocco, L.; Peak, J.C.; Katan, M.; Fukami, K.; Kataoka, T.; Yun, S.; Ryu, S.H. Multiple roles of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C isozymes. BMB Rep. 2008, 41, 415–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, S.G. Regulation of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2001, 70, 281–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.; Peng, W.; Lin, X.; Huang, Q.L.; Lin, J.Y. PLC/CAMK IV-NF-kappaB involved in the receptor for advanced glycation end products mediated signaling pathway in human endothelial cells. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2010, 320, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Q.Y.; Zhao, Y.J.; Zhou, C.; Liu, A.X.; Zhong, X.Q.; Yan, Q.; Li, Y.; Yi, F.X.; Bird, I.M.; Zheng, J. G Protein alpha Subunit 14 Mediates Fibroblast Growth Factor 2-Induced Cellular Responses in Human Endothelial Cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 10184–10195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korybalska, K.; Rutkowski, R.; Luczak, J.; Czepulis, N.; Karpinski, K.; Witowski, J. The role of purinergic P2Y12 receptor blockers on the angiogenic properties of endothelial cells: An in vitro study. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2018, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunduz, D.; Tanislav, C.; Schluter, K.D.; Schulz, R.; Hamm, C.; Aslam, M. Effect of ticagrelor on endothelial calcium signalling and barrier function. Thromb. Haemost. 2017, 117, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, D.; Konstantoulaki, M.; Ahmmed, G.U.; Malik, A.B. Sphingosine 1-phosphate-induced mobilization of intracellular Ca2+ mediates rac activation and adherens junction assembly in endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 17320–17328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhlmann, C.R.; Schaefer, C.A.; Reinhold, L.; Tillmanns, H.; Erdogan, A. Signalling mechanisms of SDF-induced endothelial cell proliferation and migration. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 335, 1107–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, R.D.; Latz, C.; Rahimi, N. Recruitment and activation of phospholipase Cgamma1 by vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 are required for tubulogenesis and differentiation of endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 16347–16355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunze, K.; Spieker, T.; Gamerdinger, U.; Nau, K.; Berger, J.; Dreyer, T.; Sindermann, J.R.; Hoffmeier, A.; Gattenlohner, S.; Brauninger, A. A recurrent activating PLCG1 mutation in cardiac angiosarcomas increases apoptosis resistance and invasiveness of endothelial cells. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 6173–6183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, R.; Kwon, J.; Li, X.; Wang, E.; Patra, S.; Bida, J.P.; Bajzer, Z.; Claesson-Welsh, L.; Mukhopadhyay, D. Distinct role of PLCbeta3 in VEGF-mediated directional migration and vascular sprouting. J. Cell Sci. 2009, 122, 1025–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeppner, L.H.; Phoenix, K.N.; Clark, K.J.; Bhattacharya, R.; Gong, X.; Sciuto, T.E.; Vohra, P.; Suresh, S.; Bhattacharya, S.; Dvorak, A.M.; et al. Revealing the role of phospholipase Cbeta3 in the regulation of VEGF-induced vascular permeability. Blood 2012, 120, 2167–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, J.M.; Baek, S.H.; Kim, Y.H.; Jin, S.Y.; Lee, H.S.; Kim, S.J.; Shin, H.K.; Lee, D.H.; Song, S.H.; Kim, C.D.; et al. Regulation of retinal angiogenesis by phospholipase C-beta3 signaling pathway. Exp. Mol. Med. 2016, 48, e240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faehling, M.; Kroll, J.; Fohr, K.J.; Fellbrich, G.; Mayr, U.; Trischler, G.; Waltenberger, J. Essential role of calcium in vascular endothelial growth factor A-induced signaling: Mechanism of the antiangiogenic effect of carboxyamidotriazole. FASEB J. 2002, 16, 1805–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamdollah Zadeh, M.A.; Glass, C.A.; Magnussen, A.; Hancox, J.C.; Bates, D.O. VEGF-mediated elevated intracellular calcium and angiogenesis in human microvascular endothelial cells in vitro are inhibited by dominant negative TRPC6. Microcirculation 2008, 15, 605–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, H.W.; James, A.F.; Foster, R.R.; Hancox, J.C.; Bates, D.O. VEGF activates receptor-operated cation channels in human microvascular endothelial cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2006, 26, 1768–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, R.; Tai, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, K.; Yang, S.; Cheng, T.; Zou, Q.; Shen, F.; Wang, Y. Critical role of TRPC6 channels in VEGF-mediated angiogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2009, 283, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrikopoulos, P.; Eccles, S.A.; Yaqoob, M.M. Coupling between the TRPC3 ion channel and the NCX1 transporter contributed to VEGF-induced ERK1/2 activation and angiogenesis in human primary endothelial cells. Cell. Signal. 2017, 37, 12–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antigny, F.; Girardin, N.; Frieden, M. Transient receptor potential canonical channels are required for in vitro endothelial tube formation. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 5917–5927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, P.G.; Gillespie, J.I. Evidence for mitochondrial Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release in permeabilised endothelial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998, 246, 543–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeley, T.P.; Siow, R.C.M.; Jacob, R.; Mann, G.E. Reduced SERCA activity underlies dysregulation of Ca2+ homeostasis under atmospheric O2 levels. FASEB J. 2018, 32, 2531–2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mountian, I.; Manolopoulos, V.G.; De Smedt, H.; Parys, J.B.; Missiaen, L.; Wuytack, F. Expression patterns of sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor isoforms in vascular endothelial cells. Cell Calcium 1999, 25, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, I.A.; Donthamsetty, R.; Debski, P.; Zhou, M.H.; Zhang, S.L.; Yuan, J.X.; Han, W.; Makino, A. STIM1 restores coronary endothelial function in type 1 diabetic mice. Circ. Res. 2012, 111, 1166–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, M.Y.; Geyer, M.; Komarova, Y.A. IP3 receptor signaling and endothelial barrier function. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2017, 74, 4189–4207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ottolini, M.; Hong, K.; Sonkusare, S.K. Calcium signals that determine vascular resistance. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Syst. Biol. Med. 2019, e1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berridge, M.J. Inositol trisphosphate and calcium signalling mechanisms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2009, 1793, 933–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Prole, D.L.; Taylor, C.W. Structure and Function of IP3 Receptors. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hertle, D.N.; Yeckel, M.F. Distribution of inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor isotypes and ryanodine receptor isotypes during maturation of the rat hippocampus. Neuroscience 2007, 150, 625–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zuccolo, E.; Laforenza, U.; Negri, S.; Botta, L.; Berra-Romani, R.; Faris, P.; Scarpellino, G.; Forcaia, G.; Pellavio, G.; Sancini, G.; et al. Muscarinic M5 receptors trigger acetylcholine-induced Ca2+ signals and nitric oxide release in human brain microvascular endothelial cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 4540–4562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuccolo, E.; Lim, D.; Kheder, D.A.; Perna, A.; Catarsi, P.; Botta, L.; Rosti, V.; Riboni, L.; Sancini, G.; Tanzi, F.; et al. Acetylcholine induces intracellular Ca2+ oscillations and nitric oxide release in mouse brain endothelial cells. Cell Calcium 2017, 66, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isakson, B.E. Localized expression of an Ins(1,4,5)P3 receptor at the myoendothelial junction selectively regulates heterocellular Ca2+ communication. J. Cell Sci. 2008, 121, 3664–3673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grayson, T.H.; Haddock, R.E.; Murray, T.P.; Wojcikiewicz, R.J.; Hill, C.E. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor subtypes are differentially distributed between smooth muscle and endothelial layers of rat arteries. Cell Calcium 2004, 36, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, T.D.; Ogden, D. Kinetics of Ca2+ release by InsP3 in pig single aortic endothelial cells: Evidence for an inhibitory role of cytosolic Ca2+ in regulating hormonally evoked Ca2+ spikes. J. Physiol. 1997, 504, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foskett, J.K.; White, C.; Cheung, K.H.; Mak, D.O. Inositol trisphosphate receptor Ca2+ release channels. Physiol. Rev. 2007, 87, 593–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaca, L.; Kunze, D.L. IP3-activated Ca2+ channels in the plasma membrane of cultured vascular endothelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. 1995, 269, C733–C738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garnier-Raveaud, S.; Usson, Y.; Cand, F.; Robert-Nicoud, M.; Verdetti, J.; Faury, G. Identification of membrane calcium channels essential for cytoplasmic and nuclear calcium elevations induced by vascular endothelial growth factor in human endothelial cells. Growth Factors 2001, 19, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dellis, O.; Dedos, S.G.; Tovey, S.C.; Taufiq Ur, R.; Dubel, S.J.; Taylor, C.W. Ca2+ entry through plasma membrane IP3 receptors. Science 2006, 313, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santulli, G.; Lewis, D.; des Georges, A.; Marks, A.R.; Frank, J. Ryanodine Receptor Structure and Function in Health and Disease. Subcell. Biochem. 2018, 87, 329–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kohler, R.; Brakemeier, S.; Kuhn, M.; Degenhardt, C.; Buhr, H.; Pries, A.; Hoyer, J. Expression of ryanodine receptor type 3 and TRP channels in endothelial cells: Comparison of in situ and cultured human endothelial cells. Cardiovasc. Res. 2001, 51, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paltauf-Doburzynska, J.; Frieden, M.; Spitaler, M.; Graier, W.F. Histamine-induced Ca2+ oscillations in a human endothelial cell line depend on transmembrane ion flux, ryanodine receptors and endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase. J. Physiol. 2000, 524, 701–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Yang, B.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.L.; Chen, R.W.; Wang, Y.B. Bradykinin regulates the expression of claudin-5 in brain microvascular endothelial cells via calcium-induced calcium release. J. Neurosci. Res. 2014, 92, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.B.; Liu, Y.H. Bradykinin selectively modulates the blood-tumor barrier via calcium-induced calcium release. J. Neurosci. Res. 2009, 87, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kameritsch, P.; Pogoda, K.; Ritter, A.; Munzing, S.; Pohl, U. Gap junctional communication controls the overall endothelial calcium response to vasoactive agonists. Cardiovasc. Res. 2012, 93, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borisova, L.; Wray, S.; Eisner, D.A.; Burdyga, T. How structure, Ca signals, and cellular communications underlie function in precapillary arterioles. Circ. Res. 2009, 105, 803–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favia, A.; Desideri, M.; Gambara, G.; D’Alessio, A.; Ruas, M.; Esposito, B.; Del Bufalo, D.; Parrington, J.; Ziparo, E.; Palombi, F.; et al. VEGF-induced neoangiogenesis is mediated by NAADP and two-pore channel-2-dependent Ca2+ signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, E4706–E4715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S. Function and dysfunction of two-pore channels. Sci. Signal. 2015, 8, re7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moccia, F.; Nusco, G.A.; Lim, D.; Kyozuka, K.; Santella, L. NAADP and InsP3 play distinct roles at fertilization in starfish oocytes. Dev. Biol. 2006, 294, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Foster, W.J.; Taylor, H.B.C.; Padamsey, Z.; Jeans, A.F.; Galione, A.; Emptage, N.J. Hippocampal mGluR1-dependent long-term potentiation requires NAADP-mediated acidic store Ca2+ signaling. Sci. Signal. 2018, 11, 9093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faris, P.; Pellavio, G.; Ferulli, F.; Di Nezza, F.; Shekha, M.; Lim, D.; Maestri, M.; Guerra, G.; Ambrosone, L.; Pedrazzoli, P.; et al. Nicotinic Acid Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate (NAADP) Induces Intracellular Ca2+ Release through the Two-Pore Channel TPC1 in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Cells. Cancers 2019, 11, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guse, A.H.; Diercks, B.P. Integration of nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP)-dependent calcium signalling. J. Physiol. 2018, 596, 2735–2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boslett, J.; Hemann, C.; Christofi, F.L.; Zweier, J.L. Characterization of CD38 in the major cell types of the heart: Endothelial cells highly express CD38 with activation by hypoxia-reoxygenation triggering NAD(P)H depletion. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2018, 314, C297–C309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, B.; Gambara, G.; Lewis, A.M.; Palombi, F.; D’Alessio, A.; Taylor, L.X.; Genazzani, A.A.; Ziparo, E.; Galione, A.; Churchill, G.C.; et al. NAADP links histamine H1 receptors to secretion of von Willebrand factor in human endothelial cells. Blood 2011, 117, 4968–4977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Galione, A. A primer of NAADP-mediated Ca2+ signalling: From sea urchin eggs to mammalian cells. Cell Calcium 2015, 58, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faris, P.; Shekha, M.; Montagna, D.; Guerra, G.; Moccia, F. Endolysosomal Ca2+ Signalling and Cancer Hallmarks: Two-Pore Channels on the Move, TRPML1 Lags Behind! Cancers 2018, 11, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berra-Romani, R.; Faris, P.; Pellavio, G.; Orgiu, M.; Negri, S.; Forcaia, G.; Var-Gaz-Guadarrama, V.; Garcia-Carrasco, M.; Botta, L.; Sancini, G.; et al. Histamine induces intracellular Ca2+ oscillations and nitric oxide release in endothelial cells from brain microvascular circulation. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronco, V.; Potenza, D.M.; Denti, F.; Vullo, S.; Gagliano, G.; Tognolina, M.; Guerra, G.; Pinton, P.; Genazzani, A.A.; Mapelli, L.; et al. A novel Ca2+-mediated cross-talk between endoplasmic reticulum and acidic organelles: Implications for NAADP-dependent Ca2+ signalling. Cell Calcium 2015, 57, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Zhao, Z.; Gu, M.; Feng, X.; Xu, H. Release and uptake mechanisms of vesicular Ca2+ stores. Protein Cell 2018, 10, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prakriya, M.; Lewis, R.S. Store-Operated Calcium Channels. Physiol. Rev. 2015, 95, 1383–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Moccia, F.; Zuccolo, E.; Soda, T.; Tanzi, F.; Guerra, G.; Mapelli, L.; Lodola, F.; D’Angelo, E. Stim and Orai proteins in neuronal Ca2+ signaling and excitability. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parekh, A.B. Functional consequences of activating store-operated CRAC channels. Cell Calcium 2007, 42, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blatter, L.A. Tissue Specificity: SOCE: Implications for Ca2+ Handling in Endothelial Cells. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 993, 343–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groschner, K.; Shrestha, N.; Fameli, N. Cardiovascular and Hemostatic Disorders: SOCE in Cardiovascular Cells: Emerging Targets for Therapeutic Intervention. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 993, 473–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullaev, I.F.; Bisaillon, J.M.; Potier, M.; Gonzalez, J.C.; Motiani, R.K.; Trebak, M. Stim1 and Orai1 mediate CRAC currents and store-operated calcium entry important for endothelial cell proliferation. Circ. Res. 2008, 103, 1289–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Cubbon, R.M.; Wilson, L.A.; Amer, M.S.; McKeown, L.; Hou, B.; Majeed, Y.; Tumova, S.; Seymour, V.A.L.; Taylor, H.; et al. Orai1 and CRAC channel dependence of VEGF-activated Ca2+ entry and endothelial tube formation. Circ. Res. 2011, 108, 1190–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jho, D.; Mehta, D.; Ahmmed, G.; Gao, X.P.; Tiruppathi, C.; Broman, M.; Malik, A.B. Angiopoietin-1 opposes VEGF-induced increase in endothelial permeability by inhibiting TRPC1-dependent Ca2 influx. Circ. Res. 2005, 96, 1282–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antigny, F.; Jousset, H.; Konig, S.; Frieden, M. Thapsigargin activates Ca2+ entry both by store-dependent, STIM1/Orai1-mediated, and store-independent, TRPC3/PLC/PKC-mediated pathways in human endothelial cells. Cell Calcium 2011, 49, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, M.H.; Zheng, H.; Si, H.; Jin, Y.; Peng, J.M.; He, L.; Zhou, Y.; Munoz-Garay, C.; Zawieja, D.C.; Kuo, L.; et al. Stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) and Orai1 mediate histamine-evoked calcium entry and nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT) signaling in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 29446–29456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girardin, N.C.; Antigny, F.; Frieden, M. Electrophysiological characterization of store-operated and agonist-induced Ca2+ entry pathways in endothelial cells. Pflug. Arch. 2010, 460, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasolato, C.; Nilius, B. Store depletion triggers the calcium release-activated calcium current (ICRAC) in macrovascular endothelial cells: A comparison with Jurkat and embryonic kidney cell lines. Pflug. Arch. 1998, 436, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kito, H.; Yamamura, H.; Suzuki, Y.; Yamamura, H.; Ohya, S.; Asai, K.; Imaizumi, Y. Regulation of store-operated Ca2+ entry activity by cell cycle dependent up-regulation of Orai2 in brain capillary endothelial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 459, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdeva, R.; Fleming, T.; Schumacher, D.; Homberg, S.; Stilz, K.; Mohr, F.; Wagner, A.H.; Tsvilovskyy, V.; Mathar, I.; Freichel, M. Methylglyoxal evokes acute Ca2+ transients in distinct cell types and increases agonist-evoked Ca2+ entry in endothelial cells via CRAC channels. Cell Calcium 2019, 78, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, J.; Kim, M.L.; Heo, W.D.; Jones, J.T.; Myers, J.W.; Ferrell, J.E., Jr.; Meyer, T. STIM is a Ca2+ sensor essential for Ca2+-store-depletion-triggered Ca2+ influx. Curr. Biol. 2005, 15, 1235–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diercks, B.P.; Werner, R.; Weidemuller, P.; Czarniak, F.; Hernandez, L.; Lehmann, C.; Rosche, A.; Kruger, A.; Kaufmann, U.; Vaeth, M.; et al. ORAI1, STIM1/2, and RYR1 shape subsecond Ca2+ microdomains upon T cell activation. Sci. Signal. 2018, 11, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiel, M.; Lis, A.; Penner, R. STIM2 drives Ca2+ oscillations through store-operated Ca2+ entry caused by mild store depletion. J. Physiol. 2013, 591, 1433–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Bruns, A.F.; Hou, B.; Rode, B.; Webster, P.J.; Bailey, M.A.; Appleby, H.L.; Moss, N.K.; Ritchie, J.E.; Yuldasheva, N.Y.; et al. Orai3 Surface Accumulation and Calcium Entry Evoked by Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2015, 35, 1987–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Moccia, F.; Dragoni, S.; Lodola, F.; Bonetti, E.; Bottino, C.; Guerra, G.; Laforenza, U.; Rosti, V.; Tanzi, F. Store-dependent Ca2+ entry in endothelial progenitor cells as a perspective tool to enhance cell-based therapy and adverse tumour vascularization. Curr. Med. Chem. 2012, 19, 5802–5818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Earley, S.; Brayden, J.E. Transient receptor potential channels in the vasculature. Physiol. Rev. 2015, 95, 645–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curcic, S.; Schober, R.; Schindl, R.; Groschner, K. TRPC-mediated Ca2+ signaling and control of cellular functions. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Buduo, C.A.; Moccia, F.; Battiston, M.; De Marco, L.; Mazzucato, M.; Moratti, R.; Tanzi, F.; Balduini, A. The importance of calcium in the regulation of megakaryocyte function. Haematologica 2014, 99, 769–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moccia, F.; Lucariello, A.; Guerra, G. TRPC3-mediated Ca2+ signals as a promising strategy to boost therapeutic angiogenesis in failing hearts: The role of autologous endothelial colony forming cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018, 233, 3901–3917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundivakkam, P.C.; Freichel, M.; Singh, V.; Yuan, J.P.; Vogel, S.M.; Flockerzi, V.; Malik, A.B.; Tiruppathi, C. The Ca2+ sensor stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) is necessary and sufficient for the store-operated Ca2+ entry function of transient receptor potential canonical (TRPC) 1 and 4 channels in endothelial cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 2012, 81, 510–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freichel, M.; Suh, S.H.; Pfeifer, A.; Schweig, U.; Trost, C.; Weissgerber, P.; Biel, M.; Philipp, S.; Freise, D.; Droogmans, G.; et al. Lack of an endothelial store-operated Ca2+ current impairs agonist-dependent vasorelaxation in TRP4-/-mice. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001, 3, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brough, G.H.; Wu, S.; Cioffi, D.; Moore, T.M.; Li, M.; Dean, N.; Stevens, T. Contribution of endogenously expressed Trp1 to a Ca2+-selective, store-operated Ca2+ entry pathway. FASEB J. 2001, 15, 1727–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cioffi, D.L.; Wu, S.; Alexeyev, M.; Goodman, S.R.; Zhu, M.X.; Stevens, T. Activation of the endothelial store-operated ISOC Ca2+ channel requires interaction of protein 4.1 with TRPC4. Circ. Res. 2005, 97, 1164–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiruppathi, C.; Freichel, M.; Vogel, S.M.; Paria, B.C.; Mehta, D.; Flockerzi, V.; Malik, A.B. Impairment of store-operated Ca2+ entry in TRPC4(-/-) mice interferes with increase in lung microvascular permeability. Circ. Res. 2002, 91, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parekh, A.B.; Putney, J.W., Jr. Store-operated calcium channels. Physiol. Rev. 2005, 85, 757–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albert, A.P.; Large, W.A. Store-operated Ca2+-permeable non-selective cation channels in smooth muscle cells. Cell Calcium 2003, 33, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Cioffi, E.A.; Alvarez, D.; Sayner, S.L.; Chen, H.; Cioffi, D.L.; King, J.; Creighton, J.R.; Townsley, M.; Goodman, S.R.; et al. Essential role of a Ca2+-selective, store-operated current (ISOC) in endothelial cell permeability: Determinants of the vascular leak site. Circ. Res. 2005, 96, 856–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaca, L.; Kunze, D.L. Depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores activates a Ca2+-selective channel in vascular endothelium. Am. J. Physiol. 1994, 267, C920–C925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groschner, K.; Hingel, S.; Lintschinger, B.; Balzer, M.; Romanin, C.; Zhu, X.; Schreibmayer, W. Trp proteins form store-operated cation channels in human vascular endothelial cells. FEBS Lett. 1998, 437, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Encabo, A.; Romanin, C.; Birke, F.W.; Kukovetz, W.R.; Groschner, K. Inhibition of a store-operated Ca2+ entry pathway in human endothelial cells by the isoquinoline derivative LOE 908. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996, 119, 702–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Cheng, K.T.; Wong, C.O.; O’Neil, R.G.; Birnbaumer, L.; Ambudkar, I.S.; Yao, X. Heteromeric TRPV4-C1 channels contribute to store-operated Ca2+ entry in vascular endothelial cells. Cell Calcium 2011, 50, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioffi, D.L.; Barry, C.; Stevens, T. Store-operated calcium entry channels in pulmonary endothelium: The emerging story of TRPCS and Orai1. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2010, 661, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cioffi, D.L.; Wu, S.; Chen, H.; Alexeyev, M.; St Croix, C.M.; Pitt, B.R.; Uhlig, S.; Stevens, T. Orai1 determines calcium selectivity of an endogenous TRPC heterotetramer channel. Circ. Res. 2012, 110, 1435–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasauskas, A.A.; Chen, H.; Wu, S.; Cioffi, D.L. The serine-threonine phosphatase calcineurin is a regulator of endothelial store-operated calcium entry. Pulm. Circ. 2014, 4, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, N.; Cioffi, D.L.; Alexeyev, M.; Rich, T.C.; Stevens, T. Sodium entry through endothelial store-operated calcium entry channels: Regulation by Orai1. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2015, 308, C277–C288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apte, R.S.; Chen, D.S.; Ferrara, N. VEGF in Signaling and Disease: Beyond Discovery and Development. Cell 2019, 176, 1248–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koch, S.; Claesson-Welsh, L. Signal transduction by vascular endothelial growth factor receptors. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012, 2, a006502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancardi, D.; Pla, A.F.; Moccia, F.; Tanzi, F.; Munaron, L. Old and new gasotransmitters in the cardiovascular system: Focus on the role of nitric oxide and hydrogen sulfide in endothelial cells and cardiomyocytes. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2011, 12, 1406–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criscuolo, G.R.; Lelkes, P.I.; Rotrosen, D.; Oldfield, E.H. Cytosolic calcium changes in endothelial cells induced by a protein product of human gliomas containing vascular permeability factor activity. J. Neurosurg. 1989, 71, 884–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cunningham, S.A.; Tran, T.M.; Arrate, M.P.; Bjercke, R.; Brock, T.A. KDR activation is crucial for VEGF165-mediated Ca2+ mobilization in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. 1999, 276, C176–C181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fearnley, G.W.; Bruns, A.F.; Wheatcroft, S.B.; Ponnambalam, S. VEGF-A isoform-specific regulation of calcium ion flux, transcriptional activation and endothelial cell migration. Biol. Open 2015, 4, 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dawson, N.S.; Zawieja, D.C.; Wu, M.H.; Granger, H.J. Signaling pathways mediating VEGF165-induced calcium transients and membrane depolarization in human endothelial cells. FASEB J. 2006, 20, 991–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrikopoulos, P.; Baba, A.; Matsuda, T.; Djamgoz, M.B.; Yaqoob, M.M.; Eccles, S.A. Ca2+ influx through reverse mode Na+/Ca2+ exchange is critical for vascular endothelial growth factor-mediated extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) 1/2 activation and angiogenic functions of human endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 37919–37931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusaba, T.; Okigaki, M.; Matui, A.; Murakami, M.; Ishikawa, K.; Kimura, T.; Sonomura, K.; Adachi, Y.; Shibuya, M.; Shirayama, T.; et al. Klotho is associated with VEGF receptor-2 and the transient receptor potential canonical-1 Ca2+ channel to maintain endothelial integrity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 19308–19313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potenza, D.M.; Guerra, G.; Avanzato, D.; Poletto, V.; Pareek, S.; Guido, D.; Gallanti, A.; Rosti, V.; Munaron, L.; Tanzi, F.; et al. Hydrogen sulphide triggers VEGF-induced intracellular Ca2+ signals in human endothelial cells but not in their immature progenitors. Cell Calcium 2014, 56, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moccia, F.; Bertoni, G.; Pla, A.F.; Dragoni, S.; Pupo, E.; Merlino, A.; Mancardi, D.; Munaron, L.; Tanzi, F. Hydrogen sulfide regulates intracellular Ca2+ concentration in endothelial cells from excised rat aorta. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2011, 12, 1416–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pupo, E.; Pla, A.F.; Avanzato, D.; Moccia, F.; Cruz, J.E.; Tanzi, F.; Merlino, A.; Mancardi, D.; Munaron, L. Hydrogen sulfide promotes calcium signals and migration in tumor-derived endothelial cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011, 51, 1765–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munaron, L.; Avanzato, D.; Moccia, F.; Mancardi, D. Hydrogen sulfide as a regulator of calcium channels. Cell Calcium 2013, 53, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altaany, Z.; Moccia, F.; Munaron, L.; Mancardi, D.; Wang, R. Hydrogen sulfide and endothelial dysfunction: Relationship with nitric oxide. Curr. Med. Chem. 2014, 21, 3646–3661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banumathi, E.; O’Connor, A.; Gurunathan, S.; Simpson, D.A.; McGeown, J.G.; Curtis, T.M. VEGF-induced retinal angiogenic signaling is critically dependent on Ca2+ signaling by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011, 52, 3103–3111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.B.; Jun, H.O.; Kim, J.H.; Fruttiger, M.; Kim, J.H. Suppression of transient receptor potential canonical channel 4 inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor-induced retinal neovascularization. Cell Calcium 2015, 57, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, F.X.; Boeldt, D.S.; Magness, R.R.; Bird, I.M. [Ca2+]i signaling vs. eNOS expression as determinants of NO output in uterine artery endothelium: Relative roles in pregnancy adaptation and reversal by VEGF165. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2011, 300, H1182–H1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bird, I.M.; Sullivan, J.A.; Di, T.; Cale, J.M.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, J.; Magness, R.R. Pregnancy-dependent changes in cell signaling underlie changes in differential control of vasodilator production in uterine artery endothelial cells. Endocrinology 2000, 141, 1107–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anaya, H.A.; Yi, F.X.; Boeldt, D.S.; Krupp, J.; Grummer, M.A.; Shah, D.M.; Bird, I.M. Changes in Ca2+ Signaling and Nitric Oxide Output by Human Umbilical Vein Endothelium in Diabetic and Gestational Diabetic Pregnancies. Biol. Reprod. 2015, 93, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boeldt, D.S.; Bird, I.M. Vascular adaptation in pregnancy and endothelial dysfunction in preeclampsia. J. Endocrinol. 2017, 232, R27–R44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Holmes, K.; Chapman, E.; See, V.; Cross, M.J. VEGF stimulates RCAN1.4 expression in endothelial cells via a pathway requiring Ca2+/calcineurin and protein kinase C-delta. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e11435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.; Spokes, K.C.; Aird, W.C.; Abid, M.R. Intracellular Ca2+ can compensate for the lack of NADPH oxidase-derived ROS in endothelial cells. FEBS Lett. 2010, 584, 3131–3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzapoiazova, T.; Kolosova, I.; Usatyuk, P.V.; Natarajan, V.; Verin, A.D. Diverse effects of vascular endothelial growth factor on human pulmonary endothelial barrier and migration. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2006, 291, L718–L724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McLaughlin, A.P.; De Vries, G.W. Role of PLCgamma and Ca2+ in VEGF- and FGF-induced choroidal endothelial cell proliferation. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2001, 281, C1448–C1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Andersson, C.; Roomans, G.M.; Ito, N.; Claesson-Welsh, L. Signaling properties of VEGF receptor-1 and -2 homo- and heterodimers. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2001, 33, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.M.; Yuan, Y.; Zawieja, D.C.; Tinsley, J.; Granger, H.J. Role of phospholipase C, protein kinase C, and calcium in VEGF-induced venular hyperpermeability. Am. J. Physiol. 1999, 276, H535–H542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pal, S.; Wu, J.; Murray, J.K.; Gellman, S.H.; Wozniak, M.A.; Keely, P.J.; Boyer, M.E.; Gomez, T.M.; Hasso, S.M.; Fallon, J.F.; et al. An antiangiogenic neurokinin-B/thromboxane A2 regulatory axis. J. Cell Biol. 2006, 174, 1047–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bazzazi, H.; Popel, A.S. Computational investigation of sphingosine kinase 1 (SphK1) and calcium dependent ERK1/2 activation downstream of VEGFR2 in endothelial cells. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2017, 13, e1005332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokota, Y.; Nakajima, H.; Wakayama, Y.; Muto, A.; Kawakami, K.; Fukuhara, S.; Mochizuki, N. Endothelial Ca2+ oscillations reflect VEGFR signaling-regulated angiogenic capacity in vivo. eLife 2015, 4, e08817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szewczyk, M.M.; Pande, J.; Akolkar, G.; Grover, A.K. Caloxin 1b3: A novel plasma membrane Ca2+-pump isoform 1 selective inhibitor that increases cytosolic Ca2+ in endothelial cells. Cell Calcium 2010, 48, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paszty, K.; Caride, A.J.; Bajzer, Z.; Offord, C.P.; Padanyi, R.; Hegedus, L.; Varga, K.; Strehler, E.E.; Enyedi, A. Plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPases can shape the pattern of Ca2+ transients induced by store-operated Ca2+ entry. Sci. Signal. 2015, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holton, M.L.; Wang, W.; Emerson, M.; Neyses, L.; Armesilla, A.L. Plasma membrane calcium ATPase proteins as novel regulators of signal transduction pathways. World J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 1, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grgic, I.; Eichler, I.; Heinau, P.; Si, H.; Brakemeier, S.; Hoyer, J.; Kohler, R. Selective blockade of the intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel suppresses proliferation of microvascular and macrovascular endothelial cells and angiogenesis in vivo. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2005, 25, 704–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, G.; Lucariello, A.; Perna, A.; Botta, L.; De Luca, A.; Moccia, F. The Role of Endothelial Ca2+ Signaling in Neurovascular Coupling: A View from the Lumen. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, J.Z.; Braun, A.P. Small-and intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels directly control agonist-evoked nitric oxide synthesis in human vascular endothelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2007, 293, C458–C467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Beckett, T.; Bagher, P.; Garland, C.J.; Dora, K.A. VEGF-A inhibits agonist-mediated Ca2+ responses and activation of IKCa channels in mouse resistance artery endothelial cells. J. Physiol. 2018, 596, 3553–3566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Jha, V.; Dhanabal, M.; Sukhatme, V.P.; Alper, S.L. Intracellular Ca2+ signaling in endothelial cells by the angiogenesis inhibitors endostatin and angiostatin. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2001, 280, C1140–C1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berridge, M.J. The endoplasmic reticulum: A multifunctional signaling organelle. Cell Calcium 2002, 32, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.W.; Machaca, K. IP3 receptors and store-operated Ca2+ entry: A license to fill. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2018, 57, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, O.H.; Verkhratsky, A. Endoplasmic reticulum calcium tunnels integrate signalling in polarised cells. Cell Calcium 2007, 42, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, A.Y.; Teggatz, E.G.; Zou, A.P.; Campbell, W.B.; Li, P.L. Endostatin uncouples NO and Ca2+ response to bradykinin through enhanced O2-production in the intact coronary endothelium. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2005, 288, H686–H694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazzazi, H.; Isenberg, J.S.; Popel, A.S. Inhibition of VEGFR2 Activation and Its Downstream Signaling to ERK1/2 and Calcium by Thrombospondin-1 (TSP1): In silico Investigation. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ayada, T.; Taniguchi, K.; Okamoto, F.; Kato, R.; Komune, S.; Takaesu, G.; Yoshimura, A. Sprouty4 negatively regulates protein kinase C activation by inhibiting phosphatidylinositol 4,5-biphosphate hydrolysis. Oncogene 2009, 28, 1076–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gifford, S.M.; Grummer, M.A.; Pierre, S.A.; Austin, J.L.; Zheng, J.; Bird, I.M. Functional characterization of HUVEC-CS: Ca2+ signaling, ERK 1/2 activation, mitogenesis and vasodilator production. J. Endocrinol. 2004, 182, 485–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munaron, L.; Fiorio Pla, A. Calcium influx induced by activation of tyrosine kinase receptors in cultured bovine aortic endothelial cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 2000, 185, 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffucci, T.; Raimondi, C.; Abu-Hayyeh, S.; Dominguez, V.; Sala, G.; Zachary, I.; Falasca, M. A phosphoinositide 3-kinase/phospholipase Cgamma1 pathway regulates fibroblast growth factor-induced capillary tube formation. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e8285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergler, S.; Dannowski, H.; Bednarz, J.; Engelmann, K.; Hartmann, C.; Pleyer, U. Calcium influx induced by activation of receptor tyrosine kinases in SV40-transfected human corneal endothelial cells. Exp. Eye Res. 2003, 77, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniotti, S.; Fiorio Pla, A.; Barral, S.; Scalabrino, O.; Munaron, L.; Lovisolo, D. Interaction between TRPC channel subunits in endothelial cells. J. Recept. Signal Transduct. Res. 2006, 26, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoniotti, S.; Fiorio Pla, A.; Pregnolato, S.; Mottola, A.; Lovisolo, D.; Munaron, L. Control of endothelial cell proliferation by calcium influx and arachidonic acid metabolism: A pharmacological approach. J. Cell. Physiol. 2003, 197, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoniotti, S.; Lovisolo, D.; Fiorio Pla, A.; Munaron, L. Expression and functional role of bTRPC1 channels in native endothelial cells. FEBS Lett. 2002, 510, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiecha, J.; Munz, B.; Wu, Y.; Noll, T.; Tillmanns, H.; Waldecker, B. Blockade of Ca2+-activated K+ channels inhibits proliferation of human endothelial cells induced by basic fibroblast growth factor. J. Vasc. Res. 1998, 35, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiecha, J.; Reineker, K.; Reitmayer, M.; Voisard, R.; Hannekum, A.; Mattfeldt, T.; Waltenberger, J.; Hombach, V. Modulation of Ca2+-activated K+ channels in human vascular cells by insulin and basic fibroblast growth factor. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 1998, 8, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharbrodt, W.; Kuhlmann, C.R.; Wu, Y.; Schaefer, C.A.; Most, A.K.; Backenkohler, U.; Neumann, T.; Tillmanns, H.; Waldecker, B.; Erdogan, A.; et al. Basic fibroblast growth factor-induced endothelial proliferation and NO synthesis involves inward rectifier K+ current. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2004, 24, 1229–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moccia, F.; Berra-Romani, R.; Tritto, S.; Signorelli, S.; Taglietti, V.; Tanzi, F. Epidermal growth factor induces intracellular Ca2+ oscillations in microvascular endothelial cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 2003, 194, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valley, C.C.; Lidke, K.A.; Lidke, D.S. The dddspatiotemporal organization of ErbB receptors: Insights from microscopy. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2014, 6, a020735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridefelt, P.; Yokote, K.; Claesson-Welsh, L.; Siegbahn, A. PDGF-BB triggered cytoplasmic calcium responses in cells with endogenous or stably transfected PDGF beta-receptors. Growth Factors 1995, 12, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moccia, F.; Bonetti, E.; Dragoni, S.; Fontana, J.; Lodola, F.; Romani, R.B.; Laforenza, U.; Rosti, V.; Tanzi, F. Hematopoietic progenitor and stem cells circulate by surfing on intracellular Ca2+ waves: A novel target for cell-based therapy and anti-cancer treatment? Curr. Signal Transduct. Ther. 2012, 7, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noels, H.; Zhou, B.; Tilstam, P.V.; Theelen, W.; Li, X.; Pawig, L.; Schmitz, C.; Akhtar, S.; Simsekyilmaz, S.; Shagdarsuren, E.; et al. Deficiency of endothelial CXCR4 reduces reendothelialization and enhances neointimal hyperplasia after vascular injury in atherosclerosis-prone mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2014, 34, 1209–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.K.; Lysko, P.G.; Pillarisetti, K.; Ohlstein, E.; Stadel, J.M. Chemokine receptors in human endothelial cells. Functional expression of CXCR4 and its transcriptional regulation by inflammatory cytokines. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 4282–4287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sameermahmood, Z.; Balasubramanyam, M.; Saravanan, T.; Rema, M. Curcumin modulates SDF-1alpha/CXCR4-induced migration of human retinal endothelial cells (HRECs). Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2008, 49, 3305–3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Augustin, H.G.; Koh, G.Y.; Thurston, G.; Alitalo, K. Control of vascular morphogenesis and homeostasis through the angiopoietin-Tie system. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009, 10, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pafumi, I.; Favia, A.; Gambara, G.; Papacci, F.; Ziparo, E.; Palombi, F.; Filippini, A. Regulation of Angiogenic Functions by Angiopoietins through Calcium-Dependent Signaling Pathways. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 965271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Ohk, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, E.J.; Kim, J.; Han, S.; Park, D.; Jung, H.; Kim, C. Calmodulin Mediates Ca2+-Dependent Inhibition of Tie2 Signaling and Acts as a Developmental Brake During Embryonic Angiogenesis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2016, 36, 1406–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, K.; Xiong, Z.G. Silencing TRPM7 promotes growth/proliferation and nitric oxide production of vascular endothelial cells via the ERK pathway. Cardiovasc. Res. 2009, 83, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashraf, S.; Bell, S.; O’Leary, C.; Canning, P.; Micu, I.; Fernandez, J.A.; O’Hare, M.; Barabas, P.; McCauley, H.; Brazil, D.P.; et al. CAMKII as a therapeutic target for growth factor-induced retinal and choroidal neovascularization. JCI Insight 2019, 4, 122442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Li, B.; Dong, Q.; Qian, C.; Cheng, J.; Wang, Y. Repetitive Transient Ischemia-Induced Cardiac Angiogenesis is Mediated by Camkii Activation. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 47, 914–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, N.M.; Wang, Y.; Youn, J.Y.; Cai, H. Endothelial cell calpain as a critical modulator of angiogenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2017, 1863, 1326–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, F.C.; Seki, A.; Yang, H.W.; Hayer, A.; Carrasco, S.; Malmersjo, S.; Meyer, T. A polarized Ca2+, diacylglycerol and STIM1 signalling system regulates directed cell migration. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014, 16, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avraham, H.K.; Lee, T.H.; Koh, Y.; Kim, T.A.; Jiang, S.; Sussman, M.; Samarel, A.M.; Avraham, S. Vascular endothelial growth factor regulates focal adhesion assembly in human brain microvascular endothelial cells through activation of the focal adhesion kinase and related adhesion focal tyrosine kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 36661–36668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brouet, A.; Sonveaux, P.; Dessy, C.; Balligand, J.L.; Feron, O. Hsp90 ensures the transition from the early Ca2+-dependent to the late phosphorylation-dependent activation of the endothelial nitric-oxide synthase in vascular endothelial growth factor-exposed endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 32663–32669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelinas, D.S.; Bernatchez, P.N.; Rollin, S.; Bazan, N.G.; Sirois, M.G. Immediate and delayed VEGF-mediated NO synthesis in endothelial cells: Role of PI3K, PKC and PLC pathways. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002, 137, 1021–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Zhu, L.; Cai, L.; Zhang, J.; Zeng, X.; Li, J.; Su, Y.; Hu, Q. A stromal interaction molecule 1 variant up-regulates matrix metalloproteinase-2 expression by strengthening nucleoplasmic Ca2+ signaling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1863, 617–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, I.; Moon, S.O.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, H.J.; Koh, Y.S.; Koh, G.Y. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression of intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1), vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1), and E-selectin through nuclear factor-kappa B activation in endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 7614–7620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Song, S.; Pi, Y.; Yu, Y.; She, W.; Ye, H.; Su, Y.; Hu, Q. Cumulated Ca2+ spike duration underlies Ca2+ oscillation frequency-regulated NFkappaB transcriptional activity. J. Cell Sci. 2011, 124, 2591–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtwright, A.; Siamakpour-Reihani, S.; Arbiser, J.L.; Banet, N.; Hilliard, E.; Fried, L.; Livasy, C.; Ketelsen, D.; Nepal, D.B.; Perou, C.M.; et al. Secreted frizzle-related protein 2 stimulates angiogenesis via a calcineurin/NFAT signaling pathway. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 4621–4628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, B.; Korn, C.; Wojtarowicz, J.; Mogler, C.; Augustin, I.; Boutros, M.; Niehrs, C.; Augustin, H.G. Endothelial RSPO3 Controls Vascular Stability and Pruning through Non-canonical WNT/Ca2+/NFAT Signaling. Dev. Cell 2016, 36, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, T.; Ueno, H.; Shibuya, M. VEGF activates protein kinase C-dependent, but Ras-independent Raf-MEK-MAP kinase pathway for DNA synthesis in primary endothelial cells. Oncogene 1999, 18, 2221–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xia, P.; Aiello, L.P.; Ishii, H.; Jiang, Z.Y.; Park, D.J.; Robinson, G.S.; Takagi, H.; Newsome, W.P.; Jirousek, M.R.; King, G.L. Characterization of vascular endothelial growth factor’s effect on the activation of protein kinase C, its isoforms, and endothelial cell growth. J. Clin. Investig. 1996, 98, 2018–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parenti, A.; Morbidelli, L.; Cui, X.L.; Douglas, J.G.; Hood, J.D.; Granger, H.J.; Ledda, F.; Ziche, M. Nitric oxide is an upstream signal of vascular endothelial growth factor-induced extracellular signal-regulated kinase1/2 activation in postcapillary endothelium. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 4220–4226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.Y.; Luciano, A.K.; Ackah, E.; Rodriguez-Vita, J.; Bancroft, T.A.; Eichmann, A.; Simons, M.; Kyriakides, T.R.; Morales-Ruiz, M.; Sessa, W.C. Endothelial Akt1 mediates angiogenesis by phosphorylating multiple angiogenic substrates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 12865–12870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Carmeliet, P.; Lampugnani, M.G.; Moons, L.; Breviario, F.; Compernolle, V.; Bono, F.; Balconi, G.; Spagnuolo, R.; Oosthuyse, B.; Dewerchin, M.; et al. Targeted deficiency or cytosolic truncation of the VE-cadherin gene in mice impairs VEGF-mediated endothelial survival and angiogenesis. Cell 1999, 98, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, G.X.; Kazlauskas, A. Axl is essential for VEGF-A-dependent activation of PI3K/Akt. EMBO J. 2012, 31, 1692–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cullen, P.J.; Lockyer, P.J. Integration of calcium and Ras signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002, 3, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, K.; Sugimoto, N.; Takuwa, N.; Takuwa, Y. Essential role for class II phosphoinositide 3-kinase alpha-isoform in Ca2+-induced, Rho- and Rho kinase-dependent regulation of myosin phosphatase and contraction in isolated vascular smooth muscle cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 2007, 71, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, M.R.; Rao, A. NFAT, immunity and cancer: A transcription factor comes of age. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2010, 10, 645–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graef, I.A.; Chen, F.; Chen, L.; Kuo, A.; Crabtree, G.R. Signals transduced by Ca2+/calcineurin and NFATc3/c4 pattern the developing vasculature. Cell 2001, 105, 863–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, P.; Mirams, G.R.; Christian, H.C.; Parekh, A.B. Control of NFAT Isoform Activation and NFAT-Dependent Gene Expression through Two Coincident and Spatially Segregated Intracellular Ca2+ Signals. Mol. Cell 2016, 64, 746–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.P.; Bakowski, D.; Mirams, G.R.; Parekh, A.B. Selective recruitment of different Ca2+-dependent transcription factors by STIM1-Orai1 channel clusters. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noy, P.J.; Gavin, R.L.; Colombo, D.; Haining, E.J.; Reyat, J.S.; Payne, H.; Thielmann, I.; Lokman, A.B.; Neag, G.; Yang, J.; et al. Tspan18 is a novel regulator of the Ca2+ channel Orai1 and von Willebrand factor release in endothelial cells. Haematologica 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schweighofer, B.; Testori, J.; Sturtzel, C.; Sattler, S.; Mayer, H.; Wagner, O.; Bilban, M.; Hofer, E. The VEGF-induced transcriptional response comprises gene clusters at the crossroad of angiogenesis and inflammation. Thromb. Haemost. 2009, 102, 544–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Minami, T.; Horiuchi, K.; Miura, M.; Abid, M.R.; Takabe, W.; Noguchi, N.; Kohro, T.; Ge, X.; Aburatani, H.; Hamakubo, T.; et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor- and thrombin-induced termination factor, Down syndrome critical region-1, attenuates endothelial cell proliferation and angiogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 50537–50554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schabbauer, G.; Schweighofer, B.; Mechtcheriakova, D.; Lucerna, M.; Binder, B.R.; Hofer, E. Nuclear factor of activated T cells and early growth response-1 cooperate to mediate tissue factor gene induction by vascular endothelial growth factor in endothelial cells. Thromb. Haemost. 2007, 97, 988–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Jia, H.; Holmes, D.I.; Stannard, A.; Zachary, I. Vascular endothelial growth factor-regulated gene expression in endothelial cells: KDR-mediated induction of Egr3 and the related nuclear receptors Nur77, Nurr1, and Nor1. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2003, 23, 2002–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, J.J.; Genesca, L.; Kingsbury, T.J.; Cunningham, K.W.; Perez-Riba, M.; Estivill, X.; de la Luna, S. DSCR1, overexpressed in Down syndrome, is an inhibitor of calcineurin-mediated signaling pathways. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000, 9, 1681–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Iizuka, M.; Abe, M.; Shiiba, K.; Sasaki, I.; Sato, Y. Down syndrome candidate region 1,a downstream target of VEGF, participates in endothelial cell migration and angiogenesis. J. Vasc. Res. 2004, 41, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghanem, A.F.; Wilkinson, E.L.; Emmett, M.S.; Aljasir, M.A.; Holmes, K.; Rothermel, B.A.; Simms, V.A.; Heath, V.L.; Cross, M.J. RCAN1.4 regulates VEGFR-2 internalisation, cell polarity and migration in human microvascular endothelial cells. Angiogenesis 2017, 20, 341–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbs, B.K.; Cruz, A.L.; Werneck, M.B.; Mognol, G.P.; Viola, J.P. Dual roles for NFAT transcription factor genes as oncogenes and tumor suppressors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2008, 28, 7168–7181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suehiro, J.; Kanki, Y.; Makihara, C.; Schadler, K.; Miura, M.; Manabe, Y.; Aburatani, H.; Kodama, T.; Minami, T. Genome-wide approaches reveal functional vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-inducible nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) c1 binding to angiogenesis-related genes in the endothelium. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 29044–29059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lisman, J.; Yasuda, R.; Raghavachari, S. Mechanisms of CaMKII action in long-term potentiation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2012, 13, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Beckendorf, J.; van den Hoogenhof, M.M.G.; Backs, J. Physiological and unappreciated roles of CaMKII in the heart. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2018, 113, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toussaint, F.; Charbel, C.; Allen, B.G.; Ledoux, J. Vascular CaMKII: Heart and brain in your arteries. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2016, 311, C462–C478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toussaint, F.; Charbel, C.; Blanchette, A.; Ledoux, J. CaMKII regulates intracellular Ca2+ dynamics in native endothelial cells. Cell Calcium 2015, 58, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakravarti, B.; Yang, J.; Ahlers-Dannen, K.E.; Luo, Z.; Flaherty, H.A.; Meyerholz, D.K.; Anderson, M.E.; Fisher, R.A. Essentiality of Regulator of G Protein Signaling 6 and Oxidized Ca2+/Calmodulin-Dependent Protein Kinase II in Notch Signaling and Cardiovascular Development. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e007038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Wang, X.; Chen, M.; Ouyang, K.; Song, L.S.; Cheng, H. Calcium flickers steer cell migration. Nature 2009, 457, 901–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tsai, F.C.; Meyer, T. Ca2+ pulses control local cycles of lamellipodia retraction and adhesion along the front of migrating cells. Curr. Biol. 2012, 22, 837–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iamshanova, O.; Fiorio Pla, A.; Prevarskaya, N. Molecular mechanisms of tumour invasion: Regulation by calcium signals. J. Physiol. 2017, 595, 3063–3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamalice, L.; Le Boeuf, F.; Huot, J. Endothelial cell migration during angiogenesis. Circ. Res. 2007, 100, 782–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariyoshi, H.; Yoshikawa, N.; Aono, Y.; Tsuji, Y.; Ueda, A.; Tokunaga, M.; Sakon, M.; Monden, M. Localized activation of m-calpain in migrating human umbilical vein endothelial cells stimulated by shear stress. J. Cell. Biochem. 2001, 81, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, N.; Ariyoshi, H.; Aono, Y.; Sakon, M.; Kawasaki, T.; Monden, M. Gradients in cytoplasmic calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i) in migrating human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) stimulated by shear-stress. Life Sci. 1999, 65, 2643–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, T.; Honda, K.; Ohata, H. Requirement of Ca2+ influx-and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-mediated m-calpain activity for shear stress-induced endothelial cell polarity. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2007, 293, C1216–C1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Inoue, K.; Sun, H.; Leng, T.; Feng, X.; Zhu, L.; Xiong, Z.G. TRPM7 regulates vascular endothelial cell adhesion and tube formation. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2015, 308, C308–C318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baldoli, E.; Maier, J.A. Silencing TRPM7 mimics the effects of magnesium deficiency in human microvascular endothelial cells. Angiogenesis 2012, 15, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukumura, D.; Gohongi, T.; Kadambi, A.; Izumi, Y.; Ang, J.; Yun, C.O.; Buerk, D.G.; Huang, P.L.; Jain, R.K. Predominant role of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in vascular endothelial growth factor-induced angiogenesis and vascular permeability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 2604–2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Papapetropoulos, A.; Garcia-Cardena, G.; Madri, J.A.; Sessa, W.C. Nitric oxide production contributes to the angiogenic properties of vascular endothelial growth factor in human endothelial cells. J. Clin. Investig. 1997, 100, 3131–3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, X.; Keller, T.C.T.; Begandt, D.; Butcher, J.T.; Biwer, L.; Keller, A.S.; Columbus, L.; Isakson, B.E. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase in the microcirculation. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2015, 72, 4561–4575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reihill, J.A.; Ewart, M.A.; Hardie, D.G.; Salt, I.P. AMP-activated protein kinase mediates VEGF-stimulated endothelial NO production. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007, 354, 1084–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Faehling, M.; Koch, E.D.; Raithel, J.; Trischler, G.; Waltenberger, J. Vascular endothelial growth factor-A activates Ca2+ -activated K+ channels in human endothelial cells in culture. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2001, 33, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, A. Wnt/Ca2+ signaling pathway: A brief overview. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2011, 43, 745–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, J.R.; Fortunato, I.C.; Fonseca, C.G.; Pezzarossa, A.; Barbacena, P.; Dominguez-Cejudo, M.A.; Vasconcelos, F.F.; Santos, N.C.; Carvalho, F.A.; Franco, C.A. Non-canonical Wnt signaling regulates junctional mechanocoupling during angiogenic collective cell migration. eLife 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.N.; Zhu, N.; Liu, C.; Wu, H.T.; Gui, Y.; Liao, D.F.; Qin, L. Wnt5a and its signaling pathway in angiogenesis. Clin. Chim. Acta 2017, 471, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korn, C.; Scholz, B.; Hu, J.; Srivastava, K.; Wojtarowicz, J.; Arnsperger, T.; Adams, R.H.; Boutros, M.; Augustin, H.G.; Augustin, I. Endothelial cell-derived non-canonical Wnt ligands control vascular pruning in angiogenesis. Development 2014, 141, 1757–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arderiu, G.; Espinosa, S.; Pena, E.; Aledo, R.; Badimon, L. Monocyte-secreted Wnt5a interacts with FZD5 in microvascular endothelial cells and induces angiogenesis through tissue factor signaling. J. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2014, 6, 380–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stefater, J.A., III; Rao, S.; Bezold, K.; Aplin, A.C.; Nicosia, R.F.; Pollard, J.W.; Ferrara, N.; Lang, R.A. Macrophage Wnt-Calcineurin-Flt1 signaling regulates mouse wound angiogenesis and repair. Blood 2013, 121, 2574–2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheng, C.W.; Yeh, J.C.; Fan, T.P.; Smith, S.K.; Charnock-Jones, D.S. Wnt5a-mediated non-canonical Wnt signalling regulates human endothelial cell proliferation and migration. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 365, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, R.J.; Barber, C.L.; Sabatier, F.; Dignat-George, F.; Melero-Martin, J.M.; Khosrotehrani, K.; Ohneda, O.; Randi, A.M.; Chan, J.K.Y.; Yamaguchi, T.; et al. Endothelial Progenitors: A Consensus Statement on Nomenclature. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2017, 6, 1316–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, C.L.; McLoughlin, K.J.; Chambers, S.E.J.; Guduric-Fuchs, J.; Stitt, A.W.; Medina, R.J. The Vasoreparative Potential of Endothelial Colony Forming Cells: A Journey Through Pre-clinical Studies. Front. Med. 2018, 5, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moccia, F.; Ruffinatti, F.A.; Zuccolo, E. Intracellular Ca2+ Signals to Reconstruct A Broken Heart: Still A Theoretical Approach? Curr. Drug Targets 2015, 16, 793–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poletto, V.; Rosti, V.; Biggiogera, M.; Guerra, G.; Moccia, F.; Porta, C. The role of endothelial colony forming cells in kidney cancer’s pathogenesis, and in resistance to anti-VEGFR agents and mTOR inhibitors: A speculative review. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2018, 132, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moccia, F.; Zuccolo, E.; Poletto, V.; Cinelli, M.; Bonetti, E.; Guerra, G.; Rosti, V. Endothelial progenitor cells support tumour growth and metastatisation: Implications for the resistance to anti-angiogenic therapy. Tumour Biol. 2015, 36, 6603–6614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poletto, V.; Dragoni, S.; Lim, D.; Biggiogera, M.; Aronica, A.; Cinelli, M.; De Luca, A.; Rosti, V.; Porta, C.; Guerra, G.; et al. Endoplasmic Reticulum Ca2+ Handling and Apoptotic Resistance in Tumor-Derived Endothelial Colony Forming Cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 2016, 117, 2260–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragoni, S.; Laforenza, U.; Bonetti, E.; Lodola, F.; Bottino, C.; Berra-Romani, R.; Carlo Bongio, G.; Cinelli, M.P.; Guerra, G.; Pedrazzoli, P.; et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor stimulates endothelial colony forming cells proliferation and tubulogenesis by inducing oscillations in intracellular Ca2+ concentration. Stem Cells 2011, 29, 1898–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuccolo, E.; Dragoni, S.; Poletto, V.; Catarsi, P.; Guido, D.; Rappa, A.; Reforgiato, M.; Lodola, F.; Lim, D.; Rosti, V.; et al. Arachidonic acid-evoked Ca2+ signals promote nitric oxide release and proliferation in human endothelial colony forming cells. Vascul. Pharmacol. 2016, 87, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Hernandez, Y.; Laforenza, U.; Bonetti, E.; Fontana, J.; Dragoni, S.; Russo, M.; Avelino-Cruz, J.E.; Schinelli, S.; Testa, D.; Guerra, G.; et al. Store-operated Ca2+ entry is expressed in human endothelial progenitor cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2010, 19, 1967–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeng, Y.S.; Choi, H.J.; Kwon, J.Y.; Park, Y.W.; Choi, K.S.; Min, J.K.; Kim, Y.H.; Suh, P.G.; Kang, K.S.; Won, M.H.; et al. Endothelial progenitor cell homing: Prominent role of the IGF2-IGF2R-PLCbeta2 axis. Blood 2009, 113, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodola, F.; Laforenza, U.; Bonetti, E.; Lim, D.; Dragoni, S.; Bottino, C.; Ong, H.L.; Guerra, G.; Ganini, C.; Massa, M.; et al. Store-operated Ca2+ entry is remodelled and controls in vitro angiogenesis in endothelial progenitor cells isolated from tumoral patients. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragoni, S.; Laforenza, U.; Bonetti, E.; Lodola, F.; Bottino, C.; Guerra, G.; Borghesi, A.; Stronati, M.; Rosti, V.; Tanzi, F.; et al. Canonical transient receptor potential 3 channel triggers vascular endothelial growth factor-induced intracellular Ca2+ oscillations in endothelial progenitor cells isolated from umbilical cord blood. Stem Cells Dev. 2013, 22, 2561–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragoni, S.; Guerra, G.; Fiorio Pla, A.; Bertoni, G.; Rappa, A.; Poletto, V.; Bottino, C.; Aronica, A.; Lodola, F.; Cinelli, M.P.; et al. A functional Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 4 (TRPV4) channel is expressed in human endothelial progenitor cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 2015, 230, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, T.C.; Nagano, M.; Yamashita, T.; Hamada, H.; Ohneda, K.; Kimura, K.; Ohneda, O. A Chemokine Receptor, CXCR4, Which Is Regulated by Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 2alpha, Is Crucial for Functional Endothelial Progenitor Cells Migration to Ischemic Tissue and Wound Repair. Stem Cells Dev. 2016, 25, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]