Morphing of Ibogaine: A Successful Attempt into the Search for Sigma-2 Receptor Ligands

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. 3D-Ligand Evaluation and Scaffold-Hopping Analysis

2.2. Molecular Docking Analysis

2.3. Pinoline Biological Assay

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. 2D to 3D Building and Minimization of Structures

3.2. Compound Alignment and Scaffold-Hopping Analysis

3.3. Molecular Docking

3.4. Radioligand Binding Assay

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hayashi, T.; Su, T.P. Sigma-1 receptor chaperones at the ER-mitochondrion interface regulate Ca(2+) signaling and cell survival. Cell 2007, 131, 596–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, H.R.; Zheng, S.; Gurpinar, E.; Koehl, A.; Manglik, A.; Kruse, A.C. Crystal structure of the human sigma1 receptor. Nature 2016, 532, 527–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujimoto, M.; Hayashi, T.; Urfer, R.; Mita, S.; Su, T.P. Sigma-1 receptor chaperones regulate the secretion of brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Synapse 2012, 66, 630–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Weng, T.Y.; Tsai, S.A.; Su, T.P. Roles of sigma-1 receptors on mitochondrial functions relevant to neurodegenerative diseases. J. Biomed. Sci. 2017, 24, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurice, T. Improving Alzheimer’s Disease-Related Cognitive Deficits with sigma1 Receptor Agonists. Drug News Perspect. 2002, 15, 617–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albayrak, Y.; Hashimoto, K. Sigma-1 Receptor Agonists and Their Clinical Implications in Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 964, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Olivieri, M.; Amata, E.; Vinciguerra, S.; Fiorito, J.; Giurdanella, G.; Drago, F.; Caporarello, N.; Prezzavento, O.; Arena, E.; Salerno, L.; et al. Antiangiogenic Effect of (+/−)-Haloperidol Metabolite II Valproate Ester [(+/−)-MRJF22] in Human Microvascular Retinal Endothelial Cells. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 9960–9966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amata, E.; Dichiara, M.; Arena, E.; Pittala, V.; Pistara, V.; Cardile, V.; Graziano, A.C.E.; Fraix, A.; Marrazzo, A.; Sortino, S.; et al. Novel Sigma Receptor Ligand-Nitric Oxide Photodonors: Molecular Hybrids for Double-Targeted Antiproliferative Effect. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 9531–9544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arena, E.; Dichiara, M.; Floresta, G.; Parenti, C.; Marrazzo, A.; Pittalà, V.; Amata, E.; Prezzavento, O. Novel Sigma-1 receptor antagonists: From opioids to small molecules: What is new? Future Med. Chem. 2018, 10, 231–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schinina, B.; Martoran, A.; Colabufo, N.A.; Contino, M.; Niso, M.; Perrone, M.G.; De Guidi, G.; Catalfo, A.; Rappazzo, G.; Zuccarello, E.; et al. 4-Nitro-2,1,3-benzoxadiazole derivatives as potential fluorescent sigma receptor probes. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 47108–47116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pati, M.L.; Groza, D.; Riganti, C.; Kopecka, J.; Niso, M.; Berardi, F.; Hager, S.; Heffeter, P.; Hirai, M.; Tsugawa, H.; et al. Sigma-2 receptor and progesterone receptor membrane component 1 (PGRMC1) are two different proteins: Proofs by fluorescent labeling and binding of sigma-2 receptor ligands to PGRMC1. Pharmacol. Res. 2017, 117, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alon, A.; Schmidt, H.R.; Wood, M.D.; Sahn, J.J.; Martin, S.F.; Kruse, A.C. Identification of the gene that codes for the sigma2 receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 7160–7165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, K.W.; Bowen, W.D. Sigma-2 receptor agonists activate a novel apoptotic pathway and potentiate antineoplastic drugs in breast tumor cell lines. Cancer Res. 2002, 62, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zeng, C.; McDonald, E.S.; Mach, R.H. Molecular Probes for Imaging the Sigma-2 Receptor: In Vitro and In Vivo Imaging Studies. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2017, 244, 309–330. [Google Scholar]

- Van Waarde, A.; Rybczynska, A.A.; Ramakrishnan, N.K.; Ishiwata, K.; Elsinga, P.H.; Dierckx, R.A. Potential applications for sigma receptor ligands in cancer diagnosis and therapy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1848, 2703–2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Washington University School of Medicine. [18F]ISO-1 PET/CT in Breast Cancer. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02762110 (accessed on 29 December 2018).

- Sahn, J.J.; Mejia, G.L.; Ray, P.R.; Martin, S.F.; Price, T.J. Sigma 2 Receptor/Tmem97 Agonists Produce Long Lasting Antineuropathic Pain Effects in Mice. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2017, 8, 1801–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vazquez-Rosa, E.; Watson, M.R.; Sahn, J.J.; Hodges, T.R.; Schroeder, R.E.; Cintron-Perez, C.J.; Shin, M.K.; Yin, T.C.; Emery, J.L.; Martin, S.F.; et al. Neuroprotective Efficacy of a Novel Sigma 2 Receptor/TMEM97 Modulator (DKR-1677) after Traumatic Brain Injury. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, B.; Sahn, J.J.; Ardestani, P.M.; Evans, A.K.; Scott, L.L.; Chan, J.Z.; Iyer, S.; Crisp, A.; Zuniga, G.; Pierce, J.T.; et al. Small molecule modulator of sigma 2 receptor is neuroprotective and reduces cognitive deficits and neuroinflammation in experimental models of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurochem. 2017, 140, 561–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, L.L.; Sahn, J.J.; Ferragud, A.; Yen, R.C.; Satarasinghe, P.N.; Wood, M.D.; Hodges, T.R.; Shi, T.; Prakash, B.A.; Friese, K.M.; et al. Small molecule modulators of sigma2R/Tmem97 reduce alcohol withdrawal-induced behaviors. Neuropsychopharmacology 2018, 43, 1867–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washington University School of Medicine. Study to Evaluate Efficacy and Safety of Roluperidone (MIN-101) in Adult Patients with Negative Symptoms of Schizophrenia. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03397134 (accessed on 29 December 2018).

- Bowen, W.D.; Vilner, B.J.; Williams, W.; Bertha, C.M.; Kuehne, M.E.; Jacobson, A.E. Ibogaine and its congeners are sigma 2 receptor-selective ligands with moderate affinity. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1995, 279, R1–R3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popik, P.; Layer, R.T.; Skolnick, P. 100 years of ibogaine: Neurochemical and pharmacological actions of a putative anti-addictive drug. Pharmacol. Rev. 1995, 47, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- He, D.Y.; Ron, D. Autoregulation of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor expression: Implications for the long-lasting actions of the anti-addiction drug, Ibogaine. FASEB J. 2006, 20, 2420–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maciulaitis, R.; Kontrimaviciute, V.; Bressolle, F.M.; Briedis, V. Ibogaine, an anti-addictive drug: Pharmacology and time to go further in development. A narrative review. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2008, 27, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litjens, R.P.; Brunt, T.M. How toxic is ibogaine? Clin. Toxicol. 2016, 54, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deecher, D.C.; Teitler, M.; Soderlund, D.M.; Bornmann, W.G.; Kuehne, M.E.; Glick, S.D. Mechanisms of action of ibogaine and harmaline congeners based on radioligand binding studies. Brain Res. 1992, 571, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popik, P.; Layer, R.T.; Skolnick, P. The putative anti-addictive drug ibogaine is a competitive inhibitor of [3H]MK-801 binding to the NMDA receptor complex. Psychopharmacology 1994, 114, 672–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sweetnam, P.M.; Lancaster, J.; Snowman, A.; Collins, J.L.; Perschke, S.; Bauer, C.; Ferkany, J. Receptor binding profile suggests multiple mechanisms of action are responsible for ibogaine’s putative anti-addictive activity. Psychopharmacology 1995, 118, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowen, W.D. Sigma receptors and iboga alkaloids. Alkaloids Chem. Biol. 2001, 56, 173–191. [Google Scholar]

- Mésangeau, C.; Amata, E.; Alsharif, W.; Seminerio, M.J.; Robson, M.J.; Matsumoto, R.R.; Poupaert, J.H.; McCurdy, C.R. Synthesis and pharmacological evaluation of indole-based sigma receptor ligands. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 46, 5154–5161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prezzavento, O.; Arena, E.; Sánchez-Fernández, C.; Turnaturi, R.; Parenti, C.; Marrazzo, A.; Catalano, R.; Amata, E.; Pasquinucci, L.; Cobos, E.J. (+)-and (−)-Phenazocine enantiomers: Evaluation of their dual opioid agonist/σ1 antagonist properties and antinociceptive effects. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 125, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastasi, G.; Miceli, C.; Pittala, V.; Modica, M.N.; Prezzavento, O.; Romeo, G.; Rescifina, A.; Marrazzo, A.; Amata, E. S2RSLDB: A comprehensive manually curated, internet-accessible database of the sigma-2 receptor selective ligands. J. Cheminform. 2017, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rescifina, A.; Floresta, G.; Marrazzo, A.; Parenti, C.; Prezzavento, O.; Nastasi, G.; Dichiara, M.; Amata, E. Development of a Sigma-2 Receptor affinity filter through a Monte Carlo based QSAR analysis. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 106, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floresta, G.; Rescifina, A.; Marrazzo, A.; Dichiara, M.; Pistara, V.; Pittala, V.; Prezzavento, O.; Amata, E. Hyphenated 3D-QSAR statistical model-scaffold hopping analysis for the identification of potentially potent and selective sigma-2 receptor ligands. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 139, 884–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rescifina, A.; Floresta, G.; Marrazzo, A.; Parenti, C.; Prezzavento, O.; Nastasi, G.; Dichiara, M.; Amata, E. Sigma-2 receptor ligands QSAR model dataset. Data Brief 2017, 13, 514–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floresta, G.; Amata, E.; Barbaraci, C.; Gentile, D.; Turnaturi, R.; Marrazzo, A.; Rescifina, A. A Structure- and Ligand-Based Virtual Screening of a Database of “Small” Marine Natural Products for the Identification of “Blue” Sigma-2 Receptor Ligands. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floresta, G.; Apirakkan, O.; Rescifina, A.; Abbate, V. Discovery of High-Affinity Cannabinoid Receptors Ligands through a 3D-QSAR Ushered by Scaffold-Hopping Analysis. Molecules 2018, 23, 2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floresta, G.; Pittala, V.; Sorrenti, V.; Romeo, G.; Salerno, L.; Rescifina, A. Development of new HO-1 inhibitors by a thorough scaffold-hopping analysis. Bioorg. Chem. 2018, 81, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floresta, G.; Amata, E.; Dichiara, M.; Marrazzo, A.; Salerno, L.; Romeo, G.; Prezzavento, O.; Pittala, V.; Rescifina, A. Identification of Potentially Potent Heme Oxygenase 1 Inhibitors through 3D-QSAR Coupled to Scaffold-Hopping Analysis. ChemMedChem 2018, 13, 1336–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sander, T.; Freyss, J.; von Korff, M.; Rufener, C. DataWarrior: An open-source program for chemistry aware data visualization and analysis. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2015, 55, 460–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheeseright, T.; Mackey, M.; Rose, S.; Vinter, A. Molecular field extrema as descriptors of biological activity: Definition and validation. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2006, 46, 665–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greish, K.F.; Salerno, L.; Al Zahrani, R.; Amata, E.; Modica, M.N.; Romeo, G.; Marrazzo, A.; Prezzavento, O.; Sorrenti, V.; Rescifina, A.; et al. Novel Structural Insight into Inhibitors of Heme Oxygenase-1 (HO-1) by New Imidazole-Based Compounds: Biochemical and In Vitro Anticancer Activity Evaluation. Molecules 2018, 23, 1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floresta, G.; Cilibrizzi, A.; Abbate, V.; Spampinato, A.; Zagni, C.; Rescifina, A. FABP4 inhibitors 3D-QSAR model and isosteric replacement of BMS309403 datasets. Data Brief 2018, 22, 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floresta, G.; Cilibrizzi, A.; Abbate, V.; Spampinato, A.; Zagni, C.; Rescifina, A. 3D-QSAR assisted identification of FABP4 inhibitors: An effective scaffold hopping analysis/QSAR evaluation. Bioorg. Chem. 2019, 84, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

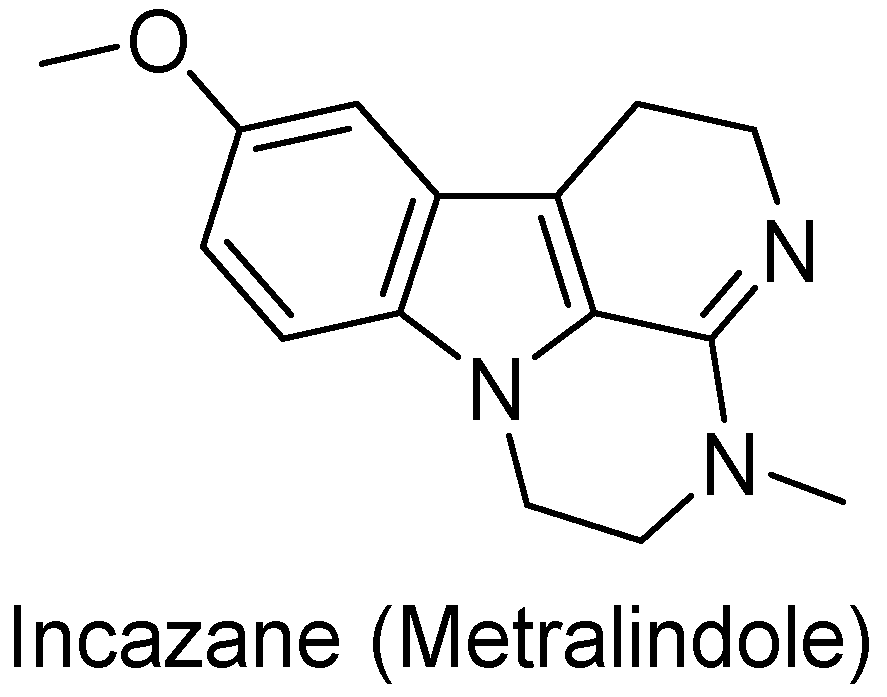

- Andreeva, N.I.; Asnina, V.V.; Liberman, S.S. Domestic Antidepressants. 3. Incazane (Metralindole). Pharm. Chem. J. 2001, 35, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airaksinen, M.M.; Huang, J.T.; Ho, B.T.; Taylor, D.; Walker, K. The uptake of 6-methoxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-beta-carboline and its effect on 5-hydroxytryptamine uptake and release in blood platelets. Acta Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1978, 43, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amata, E.; Rescifina, A.; Prezzavento, O.; Arena, E.; Dichiara, M.; Pittalà, V.; Montilla-Garcia, A.; Punzo, F.; Merino, P.; Cobos, E.J.; Marrazzo, A. (+)-Methyl (1R,2S)-2-{[4-(4-Chlorophenyl)-4-hydroxypiperidin-1-yl]methyl}-1-phenylcyclopropa necarboxylate [(+)-MR200] Derivatives as Potent and Selective Sigma Receptor Ligands: Stereochemistry and Pharmacological Properties. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 372–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lever, J.R.; Gustafson, J.L.; Xu, R.; Allmon, R.L.; Lever, S.Z. σ1 and σ2 receptor binding affinity and selectivity of SA4503 and fluoroethyl SA4503. Synapse 2006, 59, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J.J.P. Optimization of Parameters for Semiempirical Methods 1. Method. J. Comput. Chem. 1989, 10, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J.J.P. Optimization of parameters for semiempirical methods IV: Extension of MNDO, AM1, and PM3 to more main group elements. J. Mol. Model. 2004, 10, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J.J.P. MOPAC2016. Available online: http://OpenMOPAC.net (accessed on 29 December 2018).

- Krieger, E.; Vriend, G. YASARA View—Molecular graphics for all devices—From smartphones to workstations. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2981–2982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, E.; Koraimann, G.; Vriend, G. Increasing the precision of comparative models with YASARA NOVA—A self-parameterizing force field. Proteins 2002, 47, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, R.R.; Bowen, W.D.; Tom, M.A.; Vo, V.N.; Truong, D.D.; De Costa, B.R. Characterization of two novel sigma receptor ligands: Antidystonic effects in rats suggest sigma receptor antagonism. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1995, 280, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mach, R.H.; Smith, C.R.; Childers, S.R. Ibogaine possesses a selective affinity for sigma 2 receptors. Life Sci. 1995, 57, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehavenhudkins, D.L.; Fleissner, L.C.; Fordrice, F.Y. Characterization of the Binding of [H-3] (+)-Pentazocine to Sigma-Recognition Sites in Guinea-Pig Brain. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1992, 227, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Entry ID | Structure | Predicted pKi |

|---|---|---|

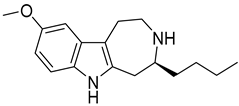

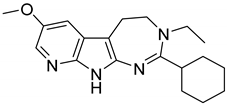

| 1 |  | 7.4 |

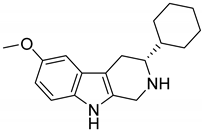

| 6 |  | 7.0 |

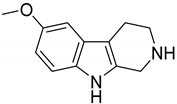

| 45 |  | 6.9 |

| 125 (Incazane derivative) |  | 6.5 |

| 179 (Pinoline) |  | 4.7 |

| Entry | Structure | Predicted pKi |

|---|---|---|

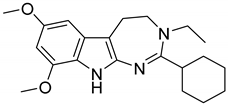

| 1 |  | 8.3 |

| 4 |  | 8.1 |

| 35 |  | 7.8 |

| Series ID_Entry ID | 3D-QSAR Predicted σ2 pKi | Docking Calculated σ2 pKi | Docking Calculated σ1 pKi | SI a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1_1 | 7.4 | 7.24 | 6.50 | 5.5 |

| 1_6 | 7.0 | 6.98 | 6.81 | 1.5 |

| 1_45 | 6.9 | 7.19 | 6.77 | 2.6 |

| 1_125 (Incazane derivative) | 6.5 | 7.40 | 5.13 | 186.2 |

| 1_179 (Pinoline) | 4.7 | 4.53 | 3.81 | 5.2 |

| 2_1 | 8.3 | 7.56 | 6.15 | 25.7 |

| 2_4 | 8.1 | 8.39 | 6.65 | 55.0 |

| 2_35 | 7.8 | 8.14 | 6.58 | 36.3 |

| Incazane | 6.4 | 6.63 | 5.35 | 19.1 |

| Ibogaine | 6.8 | 6.89 | 5.06 | 67.6 b |

| DTG | 6.8 | 7.27 | 7.32 | 0.9 c |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Floresta, G.; Dichiara, M.; Gentile, D.; Prezzavento, O.; Marrazzo, A.; Rescifina, A.; Amata, E. Morphing of Ibogaine: A Successful Attempt into the Search for Sigma-2 Receptor Ligands. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 488. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20030488

Floresta G, Dichiara M, Gentile D, Prezzavento O, Marrazzo A, Rescifina A, Amata E. Morphing of Ibogaine: A Successful Attempt into the Search for Sigma-2 Receptor Ligands. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2019; 20(3):488. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20030488

Chicago/Turabian StyleFloresta, Giuseppe, Maria Dichiara, Davide Gentile, Orazio Prezzavento, Agostino Marrazzo, Antonio Rescifina, and Emanuele Amata. 2019. "Morphing of Ibogaine: A Successful Attempt into the Search for Sigma-2 Receptor Ligands" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 20, no. 3: 488. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20030488

APA StyleFloresta, G., Dichiara, M., Gentile, D., Prezzavento, O., Marrazzo, A., Rescifina, A., & Amata, E. (2019). Morphing of Ibogaine: A Successful Attempt into the Search for Sigma-2 Receptor Ligands. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 20(3), 488. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20030488