Acute and Chronic Effects of Cocaine on Cardiovascular Health

Abstract

1. Introduction

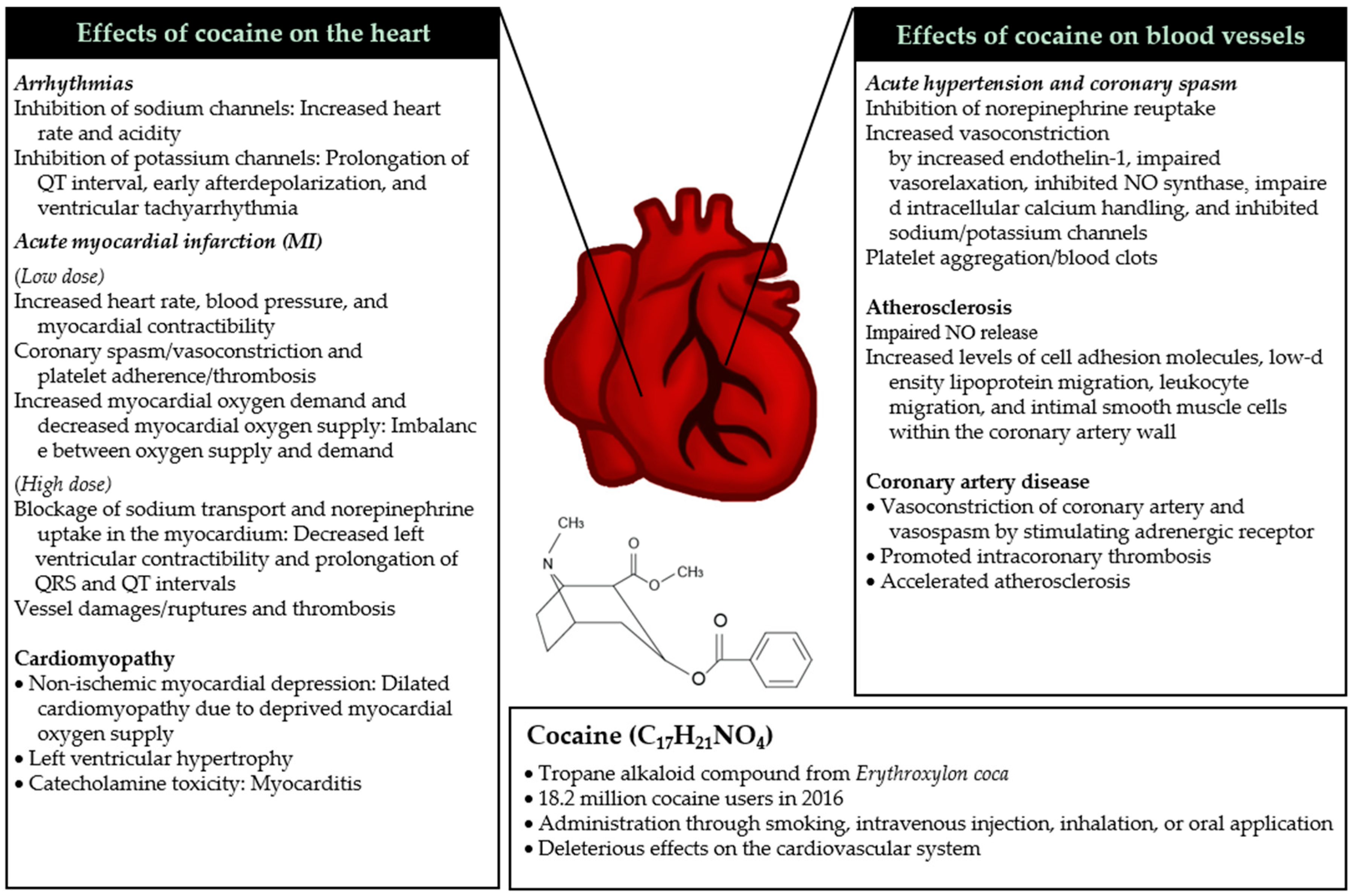

2. Pathophysiological Mechanisms of Cocaine on Cardiovascular Health

2.1. Mechanisms of Acute Toxicity

2.1.1. Acute Hypertension and Coronary Spasm

2.1.2. Arrhythmias

2.1.3. Acute Myocardial Infarction

2.2. Mechanisms of Chronic Toxicity

2.2.1. Cardiomyopathy

2.2.2. Atherosclerosis

2.2.3. Coronary Artery Diseases

3. Cocaine Cardiotoxicity in Human Studies

3.1. Acute Effects of Cocaine

3.2. Chronic Effects of Cocaine

3.3. Effects of Cocaine on Mortality

4. Cocaine and Nutrition

5. Conclusions

Author contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cornish, J.W.; O’Brien, C.P. Crack cocaine abuse: An epidemic with many public health consequences. Annu. Rev. Public Health 1996, 17, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Drug Report 2018. Available online: https://www.unodc.org/wdr2018/prelaunch/WDR18_Booklet_3_DRUG_MARKETS.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2018).

- Behavioral Health Trends in the United States: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Available online: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FRR1-2014/NSDUH-FRR1-2014.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2018).

- Egred, M.; Davis, G.K. Cocaine and the heart. Postgrad. Med. J. 2005, 81, 568–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Giorgi, A.; Fabbian, F.; Pala, M.; Bonetti, F.; Babini, I.; Bagnaresi, I.; Manfredini, F.; Portaluppi, F.; Mikhailidis, D.P.; Manfredini, R. Cocaine and acute vascular diseases. Curr. Drug Abuse Rev. 2012, 5, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, R.A.; Hillis, L.D. Cardiovascular complications of cocaine use. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trends in Substance Use Disorders among Adults Aged 18 or Older. Available online: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/report_2790/ShortReport-2790.html (accessed on 11 November 2018).

- Drug Abuse Warning Network Trends Tables, 2011 Update. Available online: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/DAWN2k11ED/DAWN2k11ED/rpts/DAWN2k11-Trend-Tables.htm (accessed on 11 November 2018).

- Vongpatanasin, W.; Mansour, Y.; Chavoshan, B.; Arbique, D.; Victor, R.G. Cocaine stimulates the human cardiovascular system via a central mechanism of action. Circulation 1999, 100, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howell, L.L.; Carroll, F.I.; Votaw, J.R.; Goodman, M.M.; Kimmel, H.L. Effects of combined dopamine and serotonin transporter inhibitors on cocaine self-administration in rhesus monkeys. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2007, 320, 757–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, B.G.; Rezkalla, S.; Kloner, R.A. Cardiovascular effects of cocaine. Circulation 2010, 122, 2558–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennings, E.J.; Leccese, A.P.; Wolff, F.A. Effects of concurrent use of alcohol and cocaine. Addiction 2002, 97, 773–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezkalla, S.H.; Kloner, R.A. Cocaine-induced acute myocardial infarction. Clin. Med. Res. 2007, 5, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, O.; Ajayeoba, O.; Kurian, D. Coronary artery spasm: An often overlooked diagnosis. Niger. Med. J. 2014, 55, 356–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talarico, G.P.; Crosta, M.L.; Giannico, M.B.; Summaria, F.; Calo, L.; Patrizi, R. Cocaine and coronary artery diseases: A systematic review of the literature. J. Cardiovasc. Med. 2017, 18, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilbert-Lampen, U.; Seliger, C.; Zilker, T.; Arendt, R.M. Cocaine increases the endothelial release of immunoreactive endothelin and its concentrations in human plasma and urine: Reversal by coincubation with sigma-receptor antagonists. Circulation 1998, 98, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togna, G.I.; Graziani, M.; Russo, P.; Caprino, L. Cocaine toxic effect on endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation: An in vitro study on rabbit aorta. Toxicol. Lett. 2001, 123, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, W.; Singh, A.K.; Arruda, J.A.; Dunea, G. Role of nitric oxide in cocaine-induced acute hypertension. Am. J. Hypertens. 1998, 11, 708–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perreault, C.L.; Morgan, K.G.; Morgan, J.P. Effects of cocaine on intracellular calcium handling in cardiac and vascular smooth muscle. NIDA Res. Monogr. 1991, 108, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Scholz, A. Mechanisms of (local) anaesthetics on voltage-gated sodium and other ion channels. Br. J. Anaesth. 2002, 89, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, A.J.; Sholar, M.B.; Mendelson, J.H.; Lukas, S.E.; Kaufman, M.J.; Renshaw, P.F.; McDonald, J.C.; Lewandrowski, K.B.; Apple, F.S.; Stec, J.J.; et al. Cocaine-induced erythrocytosis and increase in von Willebrand factor: Evidence for drug-related blood doping and prothrombotic effects. Arch. Intern. Med. 1999, 159, 1925–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crumb, W.J., Jr.; Clarkson, C.W. Characterization of cocaine-induced block of cardiac sodium channels. Biophys. J. 1990, 57, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, R.S. Treatment of patients with cocaine-induced arrhythmias: Bringing the bench to the bedside. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2010, 69, 448–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.J.; Restieaux, N.J.; Low, C.J. Myocardial infarction in young people with normal coronary arteries. Heart 1998, 79, 191–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.Q.; Crumb, W.J., Jr.; Clarkson, C.W. Cocaethylene, a metabolite of cocaine and ethanol, is a potent blocker of cardiac sodium channels. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1994, 271, 319–325. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, R.A.; DesLauriers, C.; Burda, A.; Johnson-Arbor, K. Cocaine: History, social implications, and toxicity: A review. Semin. Diagn. Pathol. 2009, 26, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, M.E. Inhibition of HERG potassium channels by cocaethylene: A metabolite of cocaine and ethanol. Cardiovasc. Res. 2002, 53, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.; Crumb, W.J., Jr.; Carlton, C.G.; Clarkson, C.W. Effects of cocaine and its major metabolites on the HERG-encoded potassium channel. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2001, 299, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- O’Leary, M.E.; Hancox, J.C. Role of voltage-gated sodium, potassium and calcium channels in the development of cocaine-associated cardiac arrhythmias. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2010, 69, 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crandall, C.G.; Vongpatanasin, W.; Victor, R.G. Mechanism of cocaine-induced hyperthermia in humans. Ann. Intern. Med. 2002, 136, 785–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catravas, J.D.; Waters, I.W. Acute cocaine intoxication in the conscious dog: Studies on the mechanism of lethality. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1981, 217, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bachi, K.; Mani, V.; Jeyachandran, D.; Fayad, Z.A.; Goldstein, R.Z.; Alia-Klein, N. Vascular disease in cocaine addiction. Atherosclerosis 2017, 262, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouhaffel, A.H.; Madu, E.C.; Satmary, W.A.; Fraker, T.D., Jr. Cardiovascular complications of cocaine. Chest 1995, 107, 1426–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, R.A.; Cigarroa, R.G.; Yancy, C.W., Jr.; Willard, J.E.; Popma, J.J.; Sills, M.N.; McBride, W.; Kim, A.S.; Hillis, L.D. Cocaine-induced coronary-artery vasoconstriction. N. Engl. J. Med. 1989, 321, 1557–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, Y.; Smith, S.W.; Thordsen, S.E.; Apple, F.S. Supply/demand type 2 myocardial infarction: Should we be paying more attention? J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 63, 2079–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, L.; Mondal, D.; Chandra, S.; Ali, M.; Agrawal, K.C. Molecular analysis of cocaine-induced endothelial dysfunction: Role of endothelin-1 and nitric oxide. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2008, 8, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohm, F.; Pernow, J. The importance of endothelin-1 for vascular dysfunction in cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc. Res. 2007, 76, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Previtali, E.; Bucciarelli, P.; Passamonti, S.M.; Martinelli, I. Risk factors for venous and arterial thrombosis. Blood Transfus. 2011, 9, 120–138. [Google Scholar]

- Badimon, L.; Padro, T.; Vilahur, G. Atherosclerosis, platelets and thrombosis in acute ischaemic heart disease. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care 2012, 1, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, N.M.; Martin, M.; Goff, T.; Morgan, J.; Elworthy, R.; Ghoneim, S. Cocaine and thrombosis: A narrative systematic review of clinical and in-vivo studies. Subst. Abuse Treat. Prev. Policy 2007, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalogeris, T.; Baines, C.P.; Krenz, M.; Korthuis, R.J. Cell biology of ischemia/reperfusion injury. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2012, 298, 229–317. [Google Scholar]

- Graziani, M.; Antonilli, L.; Togna, A.R.; Grassi, M.C.; Badiani, A.; Saso, L. Cardiovascular and hepatic toxicity of cocaine: Potential beneficial effects of modulators of oxidative stress. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, E.D.; Lange, R.A.; Cigarroa, R.G.; Hillis, L.D. Effect of cocaine on coronary artery dimensions in atherosclerotic coronary artery disease: Enhanced vasoconstriction at sites of significant stenoses. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1990, 16, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, R.E.; Hueter, D.C.; Davis, G.J. Acute myocardial infarction following cocaine abuse in a young woman with normal coronary arteries. JAMA 1985, 254, 95–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maceira, A.M.; Ripoll, C.; Cosin-Sales, J.; Igual, B.; Gavilan, M.; Salazar, J.; Belloch, V.; Pennell, D.J. Long term effects of cocaine on the heart assessed by cardiovascular magnetic resonance at 3T. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2014, 16, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hale, S.L.; Alker, K.J.; Rezkalla, S.; Figures, G.; Kloner, R.A. Adverse effects of cocaine on cardiovascular dynamics, myocardial blood flow, and coronary artery diameter in an experimental model. Am. Heart J. 1989, 118, 927–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitts, W.R.; Vongpatanasin, W.; Cigarroa, J.E.; Hillis, L.D.; Lange, R.A. Effects of the intracoronary infusion of cocaine on left ventricular systolic and diastolic function in humans. Circulation 1998, 97, 1270–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, S.L.; Alker, K.J.; Rezkalla, S.H.; Eisenhauer, A.C.; Kloner, R.A. Nifedipine protects the heart from the acute deleterious effects of cocaine if administered before but not after cocaine. Circulation 1991, 83, 1437–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardin, J.M.; Wong, N.; Alker, K.; Hale, S.L.; Paynter, J.; Knoll, M.; Jamison, B.; Patterson, M.; Kloner, R.A. Acute cocaine administration induces ventricular regional wall motion and ultrastructural abnormalities in an anesthetized rabbit model. Am. Heart J. 1994, 128, 1117–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo, C.S.; Rojas, C.A.; Martinez, S.; Riascos, R.; Marmol-Velez, A.; Carrillo, J.; Vargas, D. Cardiovascular complications of cocaine: Imaging findings. Emerg. Radiol. 2009, 16, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.J.; Said, S.; Alkhateeb, H.; Rodriguez, E.; Trien, R.; Ajmal, S.; Blandon, P.A.; Hernandez, G.T. Dilated cardiomyopathy secondary to chronic cocaine abuse: A case report. BMC Res. Notes 2013, 6, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, K.; Luk, A.; Soor, G.S.; Abraham, J.R.; Leong, S.; Butany, J. Cocaine cardiotoxicity: A review of the pathophysiology, pathology, and treatment options. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Drugs 2009, 9, 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felker, G.M.; Hu, W.; Hare, J.M.; Hruban, R.H.; Baughman, K.L.; Kasper, E.K. The spectrum of dilated cardiomyopathy. The Johns Hopkins experience with 1,278 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 1999, 78, 270–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brickner, M.E.; Willard, J.E.; Eichhorn, E.J.; Black, J.; Grayburn, P.A. Left ventricular hypertrophy associated with chronic cocaine abuse. Circulation 1991, 84, 1130–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahas, G.G.; Trouve, R.; Manger, W.M. Cocaine, catecholamines and cardiac toxicity. Acta. Anaesthesiol. Scand. Suppl. 1990, 94, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloner, R.A.; Hale, S.; Alker, K.; Rezkalla, S. The effects of acute and chronic cocaine use on the heart. Circulation 1992, 85, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolodgie, F.D.; Virmani, R.; Cornhill, J.F.; Herderick, E.E.; Smialek, J. Increase in atherosclerosis and adventitial mast cells in cocaine abusers: An alternative mechanism of cocaine-associated coronary vasospasm and thrombosis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1991, 17, 1553–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrizi, R.; Pasceri, V.; Sciahbasi, A.; Summaria, F.; Rosano, G.M.; Lioy, E. Evidence of cocaine-related coronary atherosclerosis in young patients with myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006, 47, 2120–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minor, R.L., Jr.; Scott, B.D.; Brown, D.D.; Winniford, M.D. Cocaine-induced myocardial infarction in patients with normal coronary arteries. Ann. Intern. Med. 1991, 115, 797–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Havranek, E.P.; Nademanee, K.; Grayburn, P.A.; Eichhorn, E.J. Endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation is impaired in cocaine arteriopathy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1996, 28, 1168–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, X.; Zhang, L.; Berger, O.; Stins, M.F.; Way, D.; Taub, D.D.; Chang, S.L.; Kim, K.S.; House, S.D.; Weinand, M.; et al. Cocaine enhances brain endothelial adhesion molecules and leukocyte migration. Clin. Immunol. 1999, 91, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, R.W.; Edwards, W.D. Pathogenesis of cocaine-induced ischemic heart disease. Autopsy findings in a 21-year-old man. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 1986, 110, 479–484. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, P.K. Mechanisms of plaque vulnerability and rupture. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2003, 41 (Suppl. S4), 15S–22S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindstedt, K.A.; Mayranpaa, M.I.; Kovanen, P.T. Mast cells in vulnerable atherosclerotic plaques—A view to a kill. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2007, 11, 739–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkonen, J.O.; Kovanen, P.T. Stimulation of mast cells leads to cholesterol accumulation in macrophages in vitro by a mast cell granule-mediated uptake of low density lipoprotein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1987, 84, 2287–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkonen, J.O.; Kovanen, P.T. Proteolytic enzymes of mast cell granules degrade low density lipoproteins and promote their granule-mediated uptake by macrophages in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 1989, 264, 10749–10755. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, M.; Pang, X.; Letourneau, R.; Boucher, W.; Theoharides, T.C. Acute stress induces cardiac mast cell activation and histamine release, effects that are increased in Apolipoprotein E knockout mice. Cardiovasc. Res. 2002, 55, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohm, M.; La Rosee, K.; Schwinger, R.H.; Erdmann, E. Evidence for reduction of norepinephrine uptake sites in the failing human heart. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1995, 25, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billman, G.E. Cocaine: A review of its toxic actions on cardiac function. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 1995, 25, 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, W.E.; Moore, E.E.; Penkala, R.A.; Bolgiano, D.D.; Lopez, J.A. Cocaine and specific cocaine metabolites induce von Willebrand factor release from endothelial cells in a tissue-specific manner. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2013, 33, 1230–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heesch, C.M.; Wilhelm, C.R.; Ristich, J.; Adnane, J.; Bontempo, F.A.; Wagner, W.R. Cocaine activates platelets and increases the formation of circulating platelet containing microaggregates in humans. Heart 2000, 83, 688–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moons, A.H.; Levi, M.; Peters, R.J. Tissue factor and coronary artery disease. Cardiovasc. Res. 2002, 53, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Herrera, G.A. Thrombotic microangiopathy in cocaine abuse-associated malignant hypertension: Report of 2 cases with review of the literature. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2007, 131, 1817–1820. [Google Scholar]

- Fogo, A.; Superdock, K.R.; Atkinson, J.B. Severe arteriosclerosis in the kidney of a cocaine addict. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 1992, 20, 513–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Li, J.; Li, W.; Altura, B.; Altura, B. Cocaine induces apoptosis in primary cultured rat aortic vascular smooth muscle cells: Possible relationship to aortic dissection, atherosclerosis, and hypertension. Int. J. Toxicol. 2004, 23, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabbouseh, N.M.; Ardelt, A. Cocaine mediated apoptosis of vascular cells as a mechanism for carotid artery dissection leading to ischemic stroke. Med. Hypotheses 2011, 77, 201–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramondo, A.B.; Mistrorigo, F.; Angelini, A. Intimal hyperplasia and cystic medial necrosis as substrate of acute coronary syndrome in a cocaine abuser: An in vivo/ex vivo pathological correlation. Heart 2009, 95, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhauer, J.R.; Caulfield, J.B. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection associated with cocaine use: A case report and brief review. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2001, 10, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamineni, R.; Sadhu, A.; Alpert, J.S. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: Report of two cases and a 50-year review of the literature. Cardiol. Rev. 2002, 10, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meghani, M.; Siddique, M.N.; Bhat, T.; Samarneh, M.; Elsayegh, S. Internal carotid artery redundancy and dissection in a young cocaine abuser. Vascular 2013, 21, 243–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozor, R.; Grieve, S.M.; Buchholz, S.; Kaye, S.; Darke, S.; Bhindi, R.; Figtree, G.A. Regular cocaine use is associated with increased systolic blood pressure, aortic stiffness and left ventricular mass in young otherwise healthy individuals. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e89710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariyanna, P.T.; Jayarangaiah, A.; Al-Sadawi, M.; Ahmed, R.; Green, J.; Dubson, I.; McFarlane, S.I. A rare case of second degree Mobitz type II AV block associated with cocaine use. Am. J. Med. Case Rep. 2018, 6, 146–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satran, A.; Bart, B.A.; Henry, C.R.; Murad, M.B.; Talukdar, S.; Satran, D.; Henry, T.D. Increased prevalence of coronary artery aneurysms among cocaine users. Circulation 2005, 111, 2424–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, N.; Washam, J.B.; Mountantonakis, S.E.; Li, S.; Roe, M.T.; de Lemos, J.A.; Arora, R. Characteristics, management, and outcomes of cocaine-positive patients with acute coronary syndrome (from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry). Am. J. Cardiol. 2014, 113, 749–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salihu, H.M.; Salemi, J.L.; Aggarwal, A.; Steele, B.F.; Pepper, R.C.; Mogos, M.F.; Aliyu, M.H. Opioid drug use and acute cardiac events among pregnant women in the United States. Am. J. Med. 2018, 131, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslibekyan, S.; Levitan, E.B.; Mittleman, M.A. Prevalent cocaine use and myocardial infarction. Am. J. Cardiol. 2008, 102, 966–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunja, A.; Stanislawski, M.A.; Baron, A.E.; Maddox, T.M.; Bradley, S.M.; Vidovich, M.I. The implications of cocaine use and associated behaviors on adverse cardiovascular outcomes among veterans: Insights from the VA Clinical Assessment, Reporting, and Tracking (CART) Program. Clin. Cardiol. 2018, 41, 809–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Dodani, S.; Kaeley, G.S.; Kraemer, D.F.; Aldridge, P.; Pomm, R. Cocaine use and subclinical coronary artery disease in Caucasians. J. Clin. Exp. Cardiol. 2015, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Bamberg, F.; Schlett, C.L.; Truong, Q.A.; Rogers, I.S.; Koenig, W.; Nagurney, J.T.; Seneviratne, S.; Lehman, S.J.; Cury, R.C.; Abbara, S.; et al. Presence and extent of coronary artery disease by cardiac computed tomography and risk for acute coronary syndrome in cocaine users among patients with chest pain. Am. J. Cardiol. 2009, 103, 620–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.M.; Walsh, K.M.; Shofer, F.S.; McCusker, C.M.; Litt, H.I.; Hollander, J.E. Relationship between cocaine use and coronary artery disease in patients with symptoms consistent with an acute coronary syndrome. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2011, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, H.; Moore, R.; Celentano, D.D.; Gerstenblith, G.; Treisman, G.; Keruly, J.C.; Kickler, T.; Li, J.; Chen, S.; Lai, S.; et al. HIV infection itself may not be associated with subclinical coronary artery disease among African Americans without cardiovascular symptoms. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2016, 5, e002529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, G.M.; Atta, M.G.; Fine, D.M.; McFall, A.M.; Estrella, M.M.; Zook, K.; Stein, J.H. HIV, cocaine use, and hepatitis C virus: A triad of nontraditional risk factors for subclinical cardiovascular disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2016, 36, 2100–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFilippis, E.M.; Singh, A.; Divakaran, S.; Gupta, A.; Collins, B.L.; Biery, D.; Qamar, A.; Fatima, A.; Ramsis, M.; Pipilas, D.; et al. Cocaine and marijuana use among young adults with myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 71, 2540–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morentin, B.; Ballesteros, J.; Callado, L.F.; Meana, J.J. Recent cocaine use is a significant risk factor for sudden cardiovascular death in 15–49-year-old subjects: A forensic case-control study. Addiction 2014, 109, 2071–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, A.I.; Chaudhry, S.A.; Suri, M.F. Cocaine use and the likelihood of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality: Data from the third national health and nutrition examination survey mortality follow-up study. J. Vasc. Interv. Neurol. 2014, 7, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hser, Y.I.; Kagihara, J.; Huang, D.; Evans, E.; Messina, N. Mortality among substance-using mothers in California: A 10-year prospective study. Addiction 2012, 107, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atoui, M.; Fida, N.; Nayudu, S.K.; Glandt, M.; Chilimuri, S. Outcomes of patients with cocaine induced chest pain in an inner city hospital. Cardiol. Res. 2011, 2, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollander, J.E.; Hoffman, R.S. Cocaine-induced myocardial infarction: An analysis and review of the literature. J. Emerg. Med. 1992, 10, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pletcher, M.J.; Kiefe, C.I.; Sidney, S.; Carr, J.J.; Lewis, C.E.; Hulley, S.B. Cocaine and coronary calcification in young adults: The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. Am. Heart J. 2005, 150, 921–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, S.; Lai, H.; Meng, Q.; Tong, W.; Vlahov, D.; Celentano, D.; Strathdee, S.; Nelson, K.; Fishman, E.K.; Lima, J.A. Effect of cocaine use on coronary calcium among black adults in Baltimore, Maryland. Am. J. Cardiol. 2002, 90, 326–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, S.; Lima, J.A.; Lai, H.; Vlahov, D.; Celentano, D.; Tong, W.; Bartlett, J.G.; Margolick, J.; Fishman, E.K. Human immunodeficiency virus 1 infection, cocaine, and coronary calcification. Arch. Intern. Med. 2005, 165, 690–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, S.; Fishman, E.K.; Lai, H.; Moore, R.; Cofrancesco, J., Jr.; Pannu, H.; Tong, W.; Du, J.; Barlett, J. Long-term cocaine use and antiretroviral therapy are associated with silent coronary artery disease in African Americans with HIV infection who have no cardiovascular symptoms. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008, 46, 600–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.J.; Volkow, N.D.; Logan, J.; Pappas, N.R.; Wong, C.T.; Zhu, W.; Netusil, N.; Fowler, J.S. Brain dopamine and obesity. Lancet 2001, 357, 354–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkow, N.D.; Wang, G.J.; Baler, R.D. Reward, dopamine and the control of food intake: Implications for obesity. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2011, 15, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahapatra, A. Overeating, obesity, and dopamine receptors. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2010, 1, 346–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanos, P.K.; Cho, J.; Kim, R.; Michaelides, M.; Primeaux, S.; Bray, G.; Wang, G.J.; Volkow, N.D. Bromocriptine increased operant responding for high fat food but decreased chow intake in both obesity-prone and resistant rats. Behav. Brain Res. 2011, 217, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramamoorthy, S.; Bauman, A.L.; Moore, K.R.; Han, H.; Yang-Feng, T.; Chang, A.S.; Ganapathy, V.; Blakely, R.D. Antidepressant- and cocaine-sensitive human serotonin transporter: Molecular cloning, expression, and chromosomal localization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 2542–2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, V.K.; Oury, F.; Suda, N.; Liu, Z.W.; Gao, X.B.; Confavreux, C.; Klemenhagen, K.C.; Tanaka, K.F.; Gingrich, J.A.; Guo, X.E.; et al. A serotonin-dependent mechanism explains the leptin regulation of bone mass, appetite, and energy expenditure. Cell 2009, 138, 976–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicentic, A.; Jones, D.C. The CART (cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript) system in appetite and drug addiction. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2007, 320, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogge, G.; Jones, D.; Hubert, G.W.; Lin, Y.; Kuha, M.J. CART peptides: Regulators of body weight, reward and other functions. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2008, 9, 747–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wortley, K.E.; Chang, G.Q.; Davydova, Z.; Fried, S.K.; Leibowitz, S.F. Cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript in the arcuate nucleus stimulates lipid metabolism to control body fat accrual on a high-fat diet. Regul. Pept. 2004, 117, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, R.G.; Philpot, K.; Vicentic, A.; Dominguez, G.; Hubert, G.W.; Kuhar, M.J. CART in feeding and obesity. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 15, 454–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balopole, D.C.; Hansult, C.D.; Dorph, D. Effect of cocaine on food intake in rats. Psychopharmacology 1979, 64, 121–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolgin, D.L.; Hertz, J.M. Effects of acute and chronic cocaine on milk intake, body weight, and activity in bottle- and cannula-fed rats. Behav. Pharmacol. 1995, 6, 746–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, M.W.; Morbach, C.A.; Subramanian, M.G. Comparative effects of prenatal cocaine, alcohol, and undernutrition on maternal/fetal toxicity and fetal body composition in the Sprague-Dawley rat with observations on strain-dependent differences. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 1995, 17, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, F.G.; Newcomb, M.D.; Cadish, K. Lifestyle differences between young adult cocaine users and their nonuser peers. J. Drug Educ. 1987, 17, 89–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ersche, K.D.; Stochl, J.; Woodward, J.M.; Fletcher, P.C. The skinny on cocaine: Insights into eating behavior and body weight in cocaine-dependent men. Appetite 2013, 71, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quach, L.A.; Wanke, C.A.; Schmid, C.H.; Gorbach, S.L.; Mwamburi, D.M.; Mayer, K.H.; Spiegelman, D.; Tang, A.M. Drug use and other risk factors related to lower body mass index among HIV-infected individuals. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008, 95, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, M.; Scherer, J.N.; Soares, C.M.; Guimaraes, L.S.P.; Hagen, M.E.; von Diemen, L.; Pechansky, F. Active Brazilian crack cocaine users: Nutritional, anthropometric, and drug use profiles. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2018, 40, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniz, A.E.; Evans, T. Acute gastrointestinal manifestations associated with use of crack. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2001, 19, 61–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billing, L.; Ersche, K.D. Cocaine’s appetite for fat and the consequences on body weight. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse 2015, 41, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, D.S.; Pereira, M.A.; Kroenke, C.H.; Hilner, J.E.; Van Horn, L.; Slattery, M.L.; Jacobs, D.R., Jr. Dietary fiber, weight gain, and cardiovascular disease risk factors in young adults. JAMA 1999, 282, 1539–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel, C.; Shu, R.G.; Lazar, L.D.; Vittinghoff, E.; Hsue, P.Y.; Marcus, G.M. Beta-blockers for chest pain associated with recent cocaine use. Arch. Intern. Med. 2010, 170, 874–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, P.D.; Akinlonu, A.; Mene-Afejuku, T.O.; Dumancas, C.; Saeed, M.; Cativo, E.H.; Visco, F.; Mushiyev, S.; Pekler, G. Clinical outcomes of B-blocker therapy in cocaine-associated heart failure. Int. J. Cardiol. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dattilo, P.B.; Hailpern, S.M.; Fearon, K.; Sohal, D.; Nordin, C. Beta-blockers are associated with reduced risk of myocardial infarction after cocaine use. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2008, 51, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study (year) | Country | Study Design | Data Source | Study Population (Sample Size) | Male %, Age (mean ± SD) | Outcome(s) | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute effects of cocaine | |||||||

| Kozor et al. (2014) [81] | Australia | Cross-sectional | Study participants | Adults with no coronary disease, no previous MI, no contraindication to CMR imaging, and no cocaine use in the 48 h prior to image acquisition (n = 20 for social cocaine users; n = 20 for cocaine non-users) | 85%, 37 ± 7 yrs in the social cocaine users’ group; 95%, 33 ± 7 yrs in the cocaine nonusers group | Systolic blood pressure, aortic stiffness, and LV mass | Cocaine use associated with high systolic blood pressure (134 ± 11 vs. 126 ± 11 mmHg), increased aortic stiffness, and greater LV mass (124 ± 25 vs. 105 ± 16 g) compared with no cocaine use |

| Sharma et al. (2016) [43] | US | Retrospective | ECG recordings in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study from Aug. 2006 to Dec. 2014 | Cocaine-dependent subjects (n = 97); non-cocaine-using control subjects (n = 8513) | 86%, 50 ± 4 yrs in the cocaine-dependent subjects’ group; 46%, 52 ± 5 yrs in the controls group | Resting ECG parameters | Significant effects of cocaine use on early repolarization (OR = 4.92, 95% CI: 2.73–8.87), bradycardia (OR = 3.02, 95% CI: 1.95-4.66), severe bradycardia (OR = 5.11, 95% CI: 2.95-8.84), and heart rate (B weight = −5.84, 95% CI: −7.85 to −3.82) |

| Kariyanna et al. (2018) [82] | US | Case-report | Patient | A 55-year-old woman presenting with a chest pain after cocaine use (n = 1) | 0%, 55 yrs | Second degree Mobitz type II atrioventricular block | Cocaine-induced Mobitz type II second degree atrioventricular block |

| Satran et al. (2005) [83] | US | Retrospective | Angiographic database at Hennepin County Medical Center in Minnesota | Patients with a history of cocaine use (n = 112); Patients with no history of cocaine use (n = 79) | 79%, 44 ± 8 yrs in the cocaine users’ group; 61%, 46 ± 5 yrs in the cocaine non-users group | CAA | Significantly higher CAA in cocaine users compared with cocaine nonusers (30.4% vs. 7.6%) |

| Gupta et al. (2014) 1 [84] | US | Retrospective | Acute Coronary Treatment and Intervention Outcomes Network Registry-Get With The Guidelines (ACTION Registry-GWTG) | Patients admitted within 24 h of acute MI from July 2008 to March 2010 (n = 924 in the cocaine group; n = 102,028 in the non-cocaine group) | 80%, 50 (range: 44–56) yrs in the cocaine group; 65%, 64 (range: 54–76) yrs in the non-cocaine group | Acute STEMI, cardiogenic shock, multivessel CAD, and in-hospital mortality | Higher percentages of STEMI (46.3% vs. 39.7%) and cardiogenic shock (13% vs. 4.4%) in the cocaine group, but a lower percentage of multivessel coronary artery disease (53.3% vs. 64.5%). Similar in-hospital mortality between the cocaine group and the non-cocaine group (OR = 1.00, 95% CI: 0.69–1.44) |

| Salihu et al. (2018) [85] | US | Retrospective | National Inpatient Sample (NIS) from Jan. 2002 to Dec. 2014 | Pregnant women aged 13-49 yrs who had pregnancy-related inpatient hospitalizations (n = 153,608 cocaine users; n = 56,882,258 non-drug users) | 0%, Age group: 13–24 (21.4%); 25–34 (55.4%); 35–49 (20.5%) in the cocaine users’ group; 0%, Age group: 13-24 (34.0%); 25–34 (51.3%); 35–49 (14.7%) in the non-drug users’ group | Acute MI or cardiac arrest | Cocaine use associated with acute MI or cardiac arrest (adjusted OR = 1.83, 95% CI: 1.28–2.62) |

| Aslibekyan et al. (2008) [86] | US | Retrospective | National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) in 1988–1994 and 2005–2006 | Civilian non-institutionalized US adults (a) aged 18-59 (n = 11,993); (b) aged 18-45 (n = 9337) | (a) 46%, 36 yrs (N/R); (b) 39%, 31 yrs (N/R) | Prevalence of MI | (a) No significant association between cocaine use and MI in the 18–59 age group; (b) Significant association between cocaine use of > 10 lifetime instances and MI in the 18–45 age group (aged-adjusted OR = 4.60, 95% CI: 1.12–18.88), but this association was attenuated in the multivariate-adjusted model (OR = 3.84, 95% CI: 0.98–15.07) |

| Gunja et al. (2018) 2 [87] | US | Retrospective | Veterans Affairs database | Veterans with CAD undergoing cardiac catheterization from Oct. 2007 to Sep. 2014 (n = 3082 in the cocaine group; n = 118,953 in the non-cocaine group) | 98.6%, median age: 58 (IQR: 54–62) yrs in the cocaine group; 98.6%, median age: 65 (IQR: 61–72) yrs in the non-cocaine group | MI and 1-year all-cause mortality | With adjustment of basic cardiac risk factors, cocaine use was significantly associated with MI (HR = 1.40, 95% CI: 1.07–1.83) and mortality (HR = 1.23, 95% CI: 1.08–1.39). After adjustment for risky behaviors, cocaine use was associated with mortality (HR = 1.22, 95% CI: 1.04–1.42), but not with MI (HR = 1.17, 95% CI: 0.87–1.56). After adjustment for causal pathway conditions, mortality was no longer significant (HR = 1.15, 95% CI: 0.99–1.33) |

| Chronic effects of cocaine | |||||||

| Maceira et al. (2014) [45] | Spain | Prospective | Study participants and a gender and age matched healthy group | Cocaine abusers attending a rehabilitation clinic for the first time (n = 94) | 86%, 37 ± 7 yrs | Cocaine cardiotoxicity using a CMR protocol | Increased LV end-systolic volume, LV mass index, and RV end-systolic volume, and decreased LV ejection fraction and RV ejection fraction in cocaine abusers compared with those in the gender and age matched healthy group |

| Arora et al. (2015) [88] | US | Cross-sectional | Drug treatment center in Florida | Caucasian adults with cocaine use disorder (n = 33) | 33%, 37 ± 9 yrs | Presence of subclinical CAD using CIMT | No association between chronic cocaine use and subclinical CAD measured by CIMT |

| Bamberg et al. (2009) [89] | US | Nested matched cohort | Massachusetts General Hospital | Patients who presented to the emergency department with acute chest pain in May to July, 2005 (n = 44 in the cocaine group; n = 132 in the non-cocaine group) | 86%, 46 ± 7 yrs in the cocaine group; 86%, 46 ± 7 yrs in the non-cocaine group | ACS and CAD using coronary CT | Significant association of cocaine use with increased risk of ACS group (OR = 5.79, 95% CI: 1.24–27.02), but no association with coronary stenosis |

| Chang et al. (2011) [90] | US | Cross-sectional | University of Pennsylvania Hospital | Patients who received coronary CTA for evaluation of CAD in the emergency department from May 2005 to Dec. 2008 (n = 157 in the cocaine group; n = 755 in the non-cocaine group) | 58%, 46 ± 6 yrs in the cocaine group; 40%, 48 ± 9 yrs in the non-cocaine group | CAD | No association between recent cocaine use and the presence of coronary lesions ≥ 25% (adjusted RR = 0.92, 95% CI: 0.58–1.45) and coronary lesions ≥ 50% (adjusted RR = 0.96, 95% CI: 0.46–2.01) |

| Lai et al. (2016) [91] | US | Cross-sectional | Study participants | African American adults with/without HIV infection in Baltimore (n = 737 in the cocaine group; n = 692 in the non-cocaine group) | 60.3%, 45 (IQR: 40–50) yrs in the entire population | Subclinical CAD defined by the presence of CAC detected by noncontrast CT and/or coronary plaque detected by contrast-enhanced coronary CT angiography | Chronic cocaine use associated with high risk for subclinical CAD (propensity score-adjusted prevalence ratio = 1.27, 95% CI: 1.08–1.49), CAC (propensity score-adjusted prevalence ratio=1.26, 95% CI: 1.05–1.52), any coronary stenosis (propensity score-adjusted prevalence ratio = 1.30, 95% CI: 1.08–1.57), and calcified plaques (propensity score-adjusted prevalence ratio = 1.37, 95% CI: 1.10–1.71) |

| Lucas et al. (2016) [92] | US | Cross-sectional and longitudinal | Study participants | Adults with/without human immunodeficiency virus infection in Baltimore (n = 57 never cocaine users; n = 82 past cocaine users; n = 153 current cocaine users) | 67%, 46 (IQR: 41–53) yrs in the never users; 66%, 51 (IQR: 46–54) yrs in the past users; 75%, 49 (IQR:45–52) yrs in the current users | Subclinical CVD: carotid artery plaque | Cocaine use associated with approximately three-fold higher odds of carotid plaques at baseline (OR = 3.3, 95% CI: 1.5–7.3 for past cocaine users vs. cocaine nonusers; OR = 2.7, 95% CI: 1.3–5.5 for the current cocaine users vs. cocaine nonusers) |

| Cocaine effects on mortality | |||||||

| DeFilippis et al. (2018) [93] | US | Retrospective cohort | Two academic medical centers (Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital) | Patients presenting with an MI at ≤50 years between 2000 and 2016 (n = 99 in the cocaine group; 1873 in the non-cocaine group) | 85%, 44 (range: 40–46) yrs in the cocaine group; 80%, 45 (range: 42–48) yrs in the non-cocaine group | Cardiovascular mortality and all-cause mortality | Significant association of cocaine use with cardiovascular mortality (HR = 2.32, 95% CI: 1.11–4.85) and all-cause mortality (HR = 1.91, 95% CI: 1.11–3.29) |

| Morentin et al. (2014) [94] | Spain | Case-control retrospective | Forensic autopsy reports in Biscay, Spain | All SCVD in individuals aged 15–49 (n = 311); SnoCVD (n = 126) from Jan. 2003 to Dec. 2009 | 82%, 41 ± 7 yrs in SCVD; 71%, 39 ± 7 yrs in SnoCVD | Cocaine detected in blood | Cocaine being the risk for SCVD (OR = 4.10; 95% CI: 1.12–15.0) |

| Qureshi et al. (2014) [95] | US | Retrospective | NHANES in 1988-1994 | Civilian non-institutionalized US adults aged 18–45 (n = 7751 cocaine nonusers; n = 730 infrequent cocaine users (1–10 times); n = 354 frequent cocaine users (>10 times); n = 178 regular cocaine users (>100 times)) | 43%, 31 ± 8 yrs in the cocaine non-users’ group; 59%, 31±10 yrs in the infrequent cocaine users group; 65%, 33 ± 9 yrs in the frequent cocaine users group; 70%, 33 ± 7 yrs in the regular cocaine users group | Cardiovascular mortality and all-cause mortality | Regular lifetime cocaine use was associated with high all-cause mortality (RR = 1.9, 95% CI: 1.2–3.0), but not cardiovascular mortality (RR = 0.6, 95% CI: 0.1–4.7) compared with cocaine nonusers |

| Hser et al. (2012) [96] | US | Prospective cohort | California Treatment Outcome Project (CalTOP) between 2000 and 2002, the National Death Index by 2008, the National Death Register by 2010, and the California Department of Mental Health | Women admitted to 40 drug abuse treatment programs through CalTOP (n = 4,253 for those alive in 2010; n = 194 for those deceased by 2010) | 0%, 33 ± 8 yrs for living; 0% 37 ± 7 yrs for the deceased | 8 to 10-year mortality | Cocaine was associated with higher mortality relative to methamphetamine (HR = 3.56, 95% CI: 1.95–6.48) |

| Atoui et al. (2011) [97] | US | Retrospective chart review | Electronic medical records in Bronx Lebanon Hospital Center | Patients admitted with chest pain to the hospital who had no cardiovascular risk factors from July 2009 to June 2010 (n = 54 in the cocaine group; n = 372 in the non-cocaine group) | 59%, 44 ± 10 yrs in the cocaine group; 49%, 43 ± 12 yrs in the non-cocaine group | Length of stay and mortality | No significant difference in length of stay (3.0 vs. 2.4) and in-hospital mortality (0% vs. 1%) between the cocaine group and the non-cocaine group |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, S.T.; Park, T. Acute and Chronic Effects of Cocaine on Cardiovascular Health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 584. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20030584

Kim ST, Park T. Acute and Chronic Effects of Cocaine on Cardiovascular Health. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2019; 20(3):584. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20030584

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Sung Tae, and Taehwan Park. 2019. "Acute and Chronic Effects of Cocaine on Cardiovascular Health" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 20, no. 3: 584. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20030584

APA StyleKim, S. T., & Park, T. (2019). Acute and Chronic Effects of Cocaine on Cardiovascular Health. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 20(3), 584. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20030584