Abstract

Cellular response to hypoxia is controlled by the hypoxia-inducible transcription factors HIF1α and HIF2α. Some genes are preferentially induced by HIF1α or HIF2α, as has been explored in some cell models and for particular sets of genes. Here we have extended this analysis to other HIF-dependent genes using in vitro WT8 renal carcinoma cells and in vivo conditional Vhl-deficient mice models. Moreover, we generated chimeric HIF1/2 transcription factors to study the contribution of the HIF1α and HIF2α DNA binding/heterodimerization and transactivation domains to HIF target specificity. We show that the induction of HIF1α-dependent genes in WT8 cells, such as CAIX (CAR9) and BNIP3, requires both halves of HIF, whereas the HIF2α transactivation domain is more relevant for the induction of HIF2 target genes like the amino acid carrier SLC7A5. The HIF selectivity for some genes in WT8 cells is conserved in Vhl-deficient lung and liver tissue, whereas other genes like Glut1 (Slc2a1) behave distinctly in these tissues. Therefore the relative contribution of the DNA binding/heterodimerization and transactivation domains for HIF target selectivity can be different when comparing HIF1α or HIF2α isoforms, and that HIF target gene specificity is conserved in human and mouse cells for some of the genes analyzed.

1. Introduction

In different pathological scenarios such as tumor growth, cardiac ischemia or lung diseases there are insufficiencies in the oxygen supply, a situation that also arises in physiological circumstances like embryonic development. Hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) are central to the biological tolerance of hypoxia. HIFs are heterodimeric transcription factors composed of one alpha subunit (HIFα) and one beta subunit (HIFβ), the aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (ARNT) [1,2]. While the HIFβ subunit is stable, the stability of the HIFα subunits is controlled by the prolyl-4-hydroxylase (PHD) domain proteins (PHD1, PHD2 and PHD3), 2-oxoglutarate dependent Fe2+-dioxygenases [3,4]. In normoxia, PHDs use oxygen to hydroxylate two conserved proline residues in the HIFα subunits, and these hydroxylated prolyl residues are recognized by the VHL/E3 ubiquitin ligase complex, which targets the HIFα subunits for proteasome degradation [5,6]. Conversely, in hypoxic conditions PHDs do not have enough oxygen to hydroxylate the HIFα subunits, preventing their recognition by VHL/E3 and resulting in their stabilization. Stable HIFα subunits can shuttle to the nucleus, where they can heterodimerize with HIFβ subunits and bind to DNA at the hypoxia response elements (HREs) of target genes, thereby driving a HIF-dependent transcriptional program [7,8,9].

The HIF1α and HIF2α subunits are those that have been studied most intensely, and that have been seen to be involved in numerous cellular responses to hypoxia like angiogenesis, erythropoiesis or metabolic reprogramming [10,11]. Some of the genes induced by HIF can be induced equally by both isoforms, whereas others are preferentially or exclusively controlled by the HIF1α or HIF2α isoform. Indeed, genes encoding glycolytic enzymes are exclusively controlled by HIF1α in different cellular models, which is consistent with the HIF1α isoform participating in the anaerobic metabolic switch executed by hypoxic cells [12,13,14,15]. In sharp contrast, expression of the hypoxia-dependent erythropoietin (EPO) gene in kidney tissue is controlled exclusively by the HIF2α isoform [16], reflecting the central role of HIF2α in erythropoiesis. Indeed, EPO production is controlled by HIF2α in scenarios other than the kidney, such as in hepatocytes, astrocytes and pericytes [17,18,19]. Moreover, HIF1α and HIF2α appear to be involved in opposing biological actions, in line with the target genes specifically controlled by each isoform. Thus, HIF1α and HIF2α have contrasting properties in human clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC), which is characterized by the loss of VHL and the ensuing constitutive stabilization of HIF in normoxic conditions. In this context HIF1α can repress tumor cell proliferation in different biological settings [20,21,22,23], including that of ccRCC, while HIF2α favors the proliferation of VHL-deficient RCCs and tumor formation [24,25,26]. These contrasting responses were first related to the distinct effects of HIF1α and HIF2α isoforms on c-Myc activity [24,25]. Moreover other genes have since been shown to be preferentially induced by HIF1α in VHL-deficient renal tumor cells, including carbonic anhydrase IX (CAR9, from here on referred to as CAIX) and BCL2/adenovirus E1B interacting protein 3 (BNIP3) [27]. Unlike, some other genes involved in renal cancer proliferation, such as cyclin D1 (CCND1), transforming growth factor alpha (TGFA) and the amino acid carrier SLC7A5 are preferentially induced by HIF2α. Thus, these latter genes have been associated with the oncoprotein potential of the HIF2α isoform in VHL-deficient RCC [27,28,29].

HIF1α or HIF2α isoforms show a high degree of amino acid similarity in their N-terminal half, the region containing the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) domain involved in DNA binding and the Per-Arnt-Sim (PAS) domain that is responsible for heterodimerization with the HIF1β subunit [13,30]. Weaker similarity is found in the C-terminal region of these HIF proteins where their N-terminal transactivation domain (NTAD) and C-terminal transactivation domain (CTAD) transactivation domains are located [13,30]. The specificity of HIF1 for genes like phosphoglycerate kinase 1 (PGK-1) has been attributed to its NTAD region in HEK293 and Hep3B cells [13]. However, both the bHLH-PAS and NTAD/CTAD regions have been shown to be necessary for other HIF1α-dependent genes like CAIX in 786-O RCC cells [31,32]. Regarding HIF2α, its NTAD/CTAD region is involved in the HIF2α-dependent induction of the plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (SERPINE1) and Cbp/p300-interacting transactivator, with Glu/Asp-rich carboxy-terminal domain 2 (CITED2) in some cell lines, such as Hep3B [13], as well as that of PHD3 in the 786-O cell line [31]. HIF target gene specificity has been largely studied in in vitro cellular models [12,13,27,31,33,34,35]. Moreover, the target specificity of HIF1 and HIF2 in biological settings has been less well explored in vivo [17,36]. In addition, the relative contribution of the bHLH-PAS and NTAD/CTAD halves of HIF1α and HIF2α to target gene selectivity has been studied for particular sets of genes. Here we have extended the analysis to some other HIF1α and HIF2α-dependent genes in an in vitro cell model of human renal cell carcinoma as well as in mice with Vhl gene inactivation in which HIF1α and HIF2α isoforms are constitutively activated. Moreover, we have evaluated the relative contribution of the bHLH/PAS and the NTAD/CTAD transactivation halves to confer HIF1α and HIF2α-target selectivity for some genes that have not been included in previous studies. We found that both HIF1α bHLH/PAS and NTAD/CTAD halves can be necessary to induce some HIF1α-dependent genes while the HIF2α NTAD/CTAD half is more relevant to confer HIF2 target selectivity. Finally we found that the target selectivity showed by most of the genes preferentially induced by HIF2α in human renal cell carcinoma is controlled by HIF2α in the liver, the lung and the kidney of Vhl-deficient mice, suggesting that HIF target specificity has been conserved in some extent between mouse and human cells.

2. Results

2.1. Target Gene Selectivity of HIF1α and HIF2α in WT8 Cells

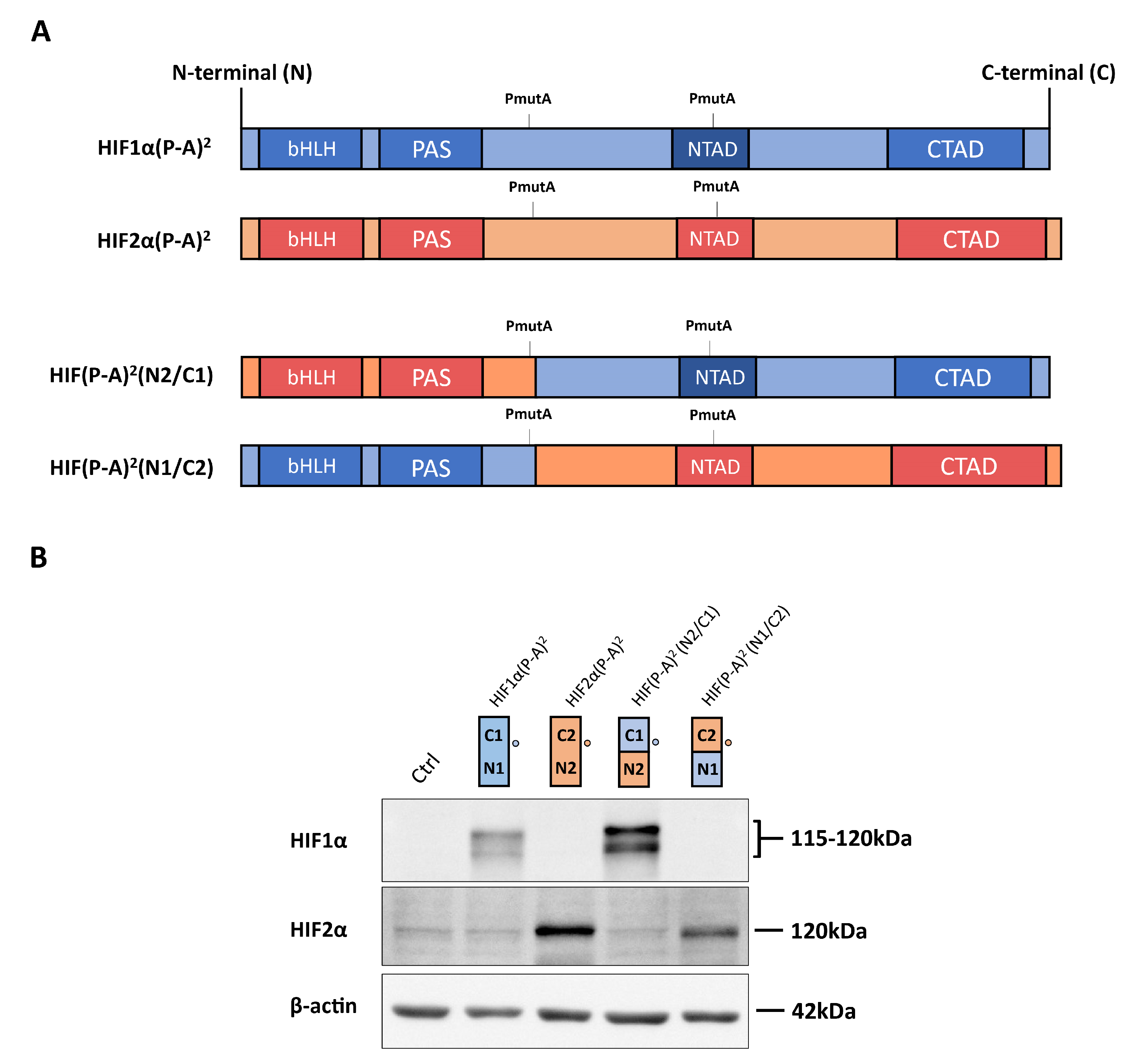

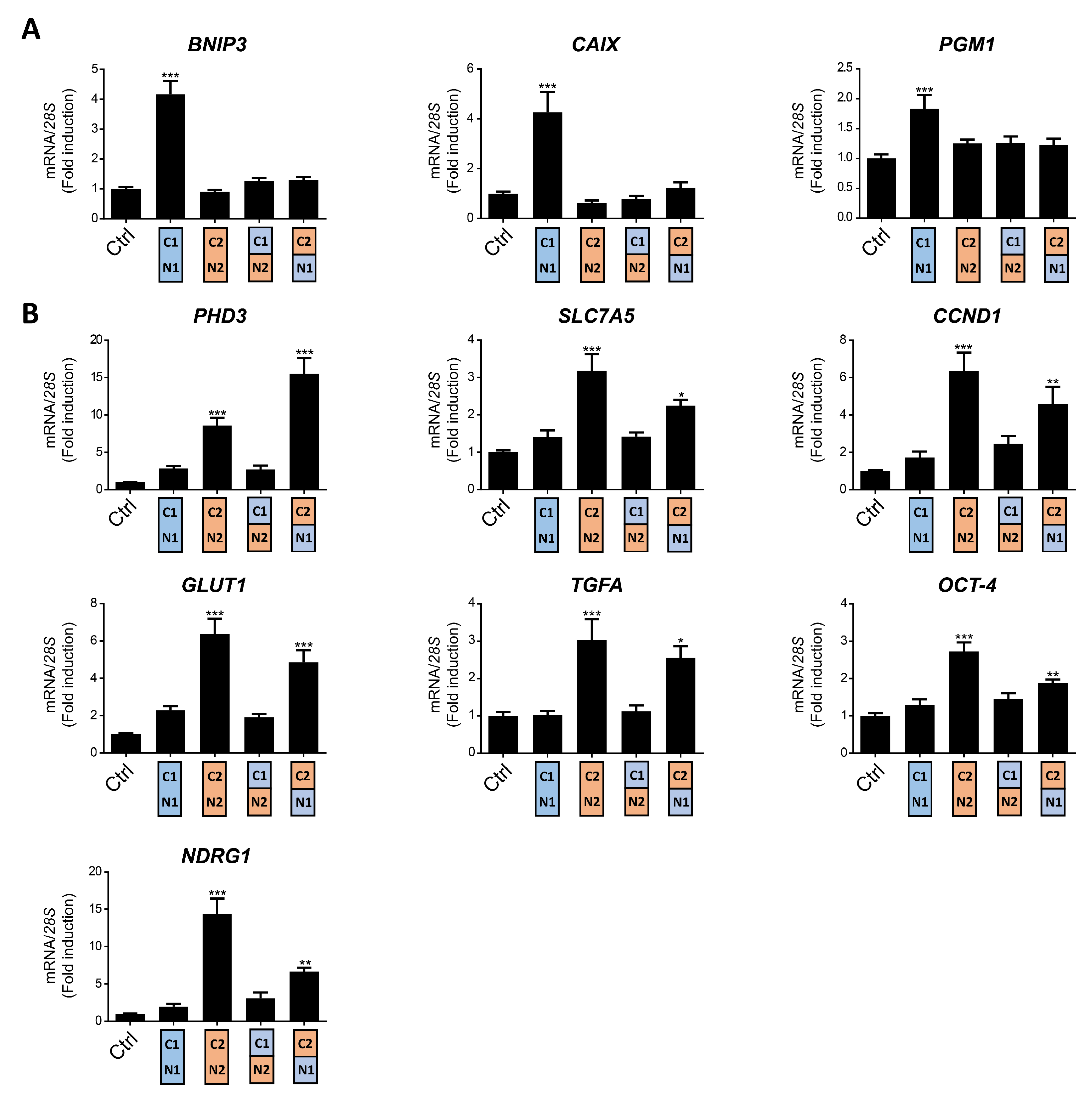

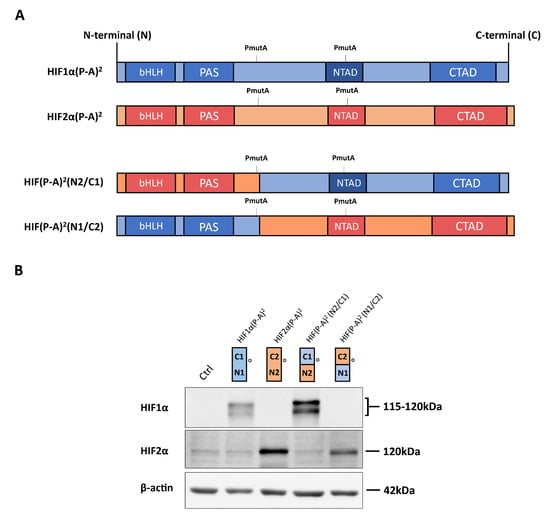

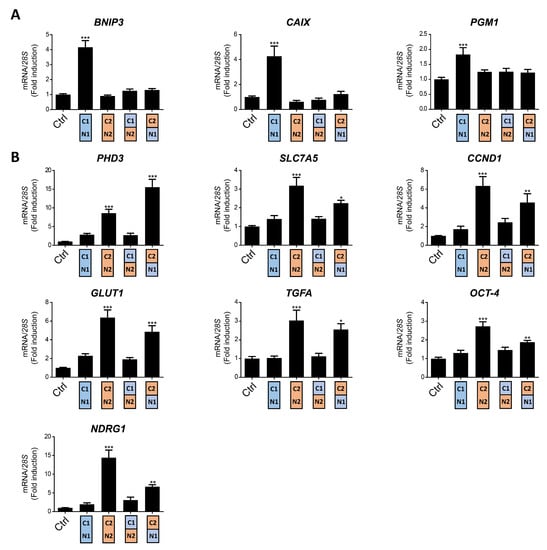

The VHL-deficient ccRCC cells represent a model in which genes preferentially induced by HIF1α and HIF2α have been identified, and where both HIF isoforms are constitutively active in normoxic conditions. To study the distinct transcriptional responses provoked by HIF1α or HIF2α in renal cell carcinoma (RCC), we used WT8 cells that were generated by restoration of VHL expression into the 786-O VHL deficient RCC cell line [26]. The specific transcriptional effect of the HIF1α and HIF2α isoforms can be investigated in this cell model by expressing constitutively active HIF1α or HIF2α constructs HIF1α(P-A)2 or HIF2α(P-A)2, which lack the critical proline residues for VHL recognition (Figure 1A,B). As such, the expression of CAIX, BNIP3 and phosphoglycerate mutase-1 (PGM1) was elevated exclusively in HIF1α(P-A)2 WT8 cells but not in HIF2α(P-A)2 WT8 cells relative to the control cells (Figure 2A), in line with previous studies showing that these genes are induced by HIF1α in ccRCC cells [27,31,37,38]. By contrast, the expression of other HIF-dependent genes like PHD3, CCND1, solute carrier family 2 member 1 (SLC2A1 or GLUT-1), TGFA, POU domain class 5 transcription factor 1 (POU5F1 or OCT-4) and N-myc downstream regulated gene 1 (NDRG1) was preferentially elevated in HIF2α(P-A)2 WT8 cells (Figure 2B), again in line with previous studies showing the participation of HIF2α in the gene expression of these genes [27,29,31,39,40].

Figure 1.

Expression of hypoxia-inducible transcription factor (HIF)1α(P-A)2, HIF2α(P-A)2 and the HIF(P-A)2 (N2/C1), HIF(P-A)2 (N1/C2) chimeric versions in WT8 cells. (A) Scheme of the HIF1α(P-A)2 (in blue) and HIF2α(P-A)2 (in red), as well as the HIF1α/HIF2α chimeric constructs. The HIF(P-A)2 (N2/C1) construct contains residues 1–414 of HIF2α, including the HIF2α basic helix-loop-helix-Per-Arnt-Sim (bHLH-PAS) domain, and residues 412–826 of HIF1α that includes the HIF1α N-terminal transactivation domain/N-terminal transactivation domain (NTAD/CTAD) transactivation domains. The HIF(P-A)2 (N1/C2) construct contains amino acids 1–411 of HIF1α, including the HIF1α bHLH-PAS domain, and amino acids 415–870 of HIF2α that includes the HIF2α NTAD/CTAD transactivation domain; (B) representative Western blots probed for the HIF1α, HIF2α and β-actin proteins in control WT8 cells, and those expressing the HIF1α(P-A)2, HIF2α(P-A)2 and the HIF(P-A)2 (N2/C1) or HIF(P-A)2 (N1/C2) chimeric constructs. Circle indicates the HIF1α and HIF2α half where the antibodies against HIF1α or anti-HIF2α recognize. Estimated molecular weights of HIF1α and HIF2α (based on molecular weights markers included in the Western blot analysis) are included.

Figure 2.

Target gene specificity for HIF1α(P-A)2, HIF2α(P-A)2 and the HIF(P-A)2 (N2/C1), HIF(P-A)2 (N1/C2) chimeric versions in WT8 cells. (A) Relative BNIP3, PGM1 and CAIX gene expression in control WT8 cells and those expressing the HIF1α(P-A)2, HIF2α(P-A)2 and the HIF(P-A)2 (N2/C1) or HIF(P-A)2 (N1/C2) chimeric constructs; (B) relative PHD3, OCT-4, NDRG1, TFGA, GLUT1, CCND1 and SLC7A5 expression in control WT8 cells (n = 6), and those expressing the HIF1α(P-A)2 (n = 6), HIF2α(P-A)2 (n = 6) and the HIF(P-A)2 (N2/C1) (n = 6) or HIF(P-A)2 (N1/C2) (n = 4) chimeric constructs. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001. Significance with control group is indicated.

As described above, there is higher amino acid similarity in the half of the HIFα isoforms involved in DNA binding and heterodimerization, containing the bHLH and PAS domains, than in that which contains their NTAD and CTAD domains (Figure 1A). Therefore, we set out to assess the relative contribution of the bHLH-PAS region as opposed to that of the NTAD/CTAD transactivation region of the HIF1α and HIF2α isoforms to their target gene selectivity in WT8 cells. As such, we generated a HIF(P-A)2 (N1/C2) chimera that contained the HIF1α bHLH-PAS N-terminal region (residues 1 to 411 of HIF1α) fused to the HIF2α C-terminal stabilization/transactivation region (residues 415 to 870 of HIF2α) (Figure 1A). Similarly, we also generated the HIF(P-A)2 (N2/C1) chimera comprised of the HIF2α bHLH-PAS N-terminal region (residues 1 to 414 of HIF2α) fused to the HIF1α C-terminal stabilization/transactivation region (residues 412 to 826 of HIF1α) (Figure 1A). Like HIF1(P-A)2 and HIF2(P-A)2, these chimeras also lack the key proline residues for VHL recognition and therefore they are constitutively expressed in WT8 cells under normoxic conditions. Indeed, HIF(P-A)2 (N1/C2) and HIF(P-A)2 (N2/C1) chimeras were also efficiently expressed in normoxic WT8 cells (Figure 1B). The expression of CAIX, BNIP3 and PGM1 was not elevated in either HIF(P-A)2 (N2/C1) WT8 cells or HIF(P-A)2 (N1/C2) WT8 cells (Figure 2A). Hence, these data suggest that the HIF1(P-A)2-dependent induction of CAIX, BNIP3 and PGM1 expression requires the integrity of both the bHLH-PAS and the transactivation NTAD/CTAD HIF1α region (Figure 2A).

In terms of the HIF2-dependent genes, we first found that the HIF (P-A)2 (N2/C1) chimera did not induce or produced a modest elevation in the expression of the HIF2-dependent genes analyzed. In contrast PHD3 expression was induced by the HIF(P-A)2 (N1/C2) chimera to a greater extent than by HIF2(P-A)2 (Figure 2B). Moreover HIF(P-A)2 (N1/C2) also induced CCND1, GLUT1, TGFA, NDRG1 and OCT-4 expression but only partially when compared with HIF2(P-A)2 especially OCT-4 and NDRG1 (Figure 2B). Notably, the HIF(P-A)2 (N1/C2) chimeric protein was routinely expressed more weakly than HIF2(P-A)2 (Figure 1B), which might also explain the partial induction of CCND1, GLUT-1, TGFA, NDRG1 and OCT-4 gene expression by this HIF(P-A)2 (N1/C2) chimera (see discussion). These data suggest that the NTAD/CTAD transactivation region of HIF2α plays a role in the gene expression specifically induced by HIF2, especially in the case of PHD3 for which HIF2α selectivity could be fully attributed to this C-terminal region of HIF2α in WT8 cells. Moreover, these data also suggest that the relative contribution of the NTAD/CTAD transactivation region of HIF2α might be different in each HIF2α-dependent gene.

Collectively these data suggest that selective HIF1-dependent induction of CAIX, BNIP3 and PGM1 in WT8 cells requires the presence of both the bHLH-PAS and transactivation NTAD/CTAD regions of HIF1α, while the transactivation NTAD/CTAD region of HIF2α seem to be more relevant than the bHLH-PAS region to explain the preferential induction of PHD3, CCND1, GLUT-1, TGFA, OCT-4 and NDRG1 by HIF2α.

2.2. The Role of the HIF2α NTAD/CTAD Transactivation Region in the Expression of the SLC7A5 Amino Acid Carrier

We previously identified the expression of the amino acid carrier SLC7A5 to be preferentially induced by the HIF2α isoform in RCC cells, providing a molecular basis for the pro-proliferative activity of HIF2α in these tumor cells [28]. Moreover, increased SLC7A5 expression has been found in VHL-deficient human ccRCC samples relative to a healthy kidney [28,41,42]. In line with our previous studies, the expression of SLC7A5 mRNA was preferentially induced in HIF2α(P-A)2 WT8 cells when compared to HIF1α(P-A)2 and control WT8 cells (Figure 2B). Thus, we wondered about the relative contribution of the HIF2α bHLH/PAS and NTAD/CTAD domains to HIF2α-dependent SLC7A5 expression. We found that the HIF(P-A)2 (N1/C2) chimera partially induced SLC7A5 gene expression, while HIF(P-A)2 (N2/C1) did not show any significant effect on SLC7A5 expression relative to HIF2(P-A)2 in WT8 cells (Figure 2B). Therefore, the NTAD/CTAD HIF2α region appeared to be more relevant to explain the preferential SLC7A5 expression driven by the HIF2α isoform, which is similar to the data obtained for the CCND1, GLUT-1, TGFA, OCT-4 and NDRG1 genes (Figure 2B). However, and as mentioned above, it should be noted that the expression of the HIF(P-A)2 (N1/C2) chimera was weaker than that of HIF2(P-A)2 (Figure 1B), which might also explain why HIF(P-A)2 (N1/C2) might be less potent as HIF2(P-A)2 to induce SLC7A5.

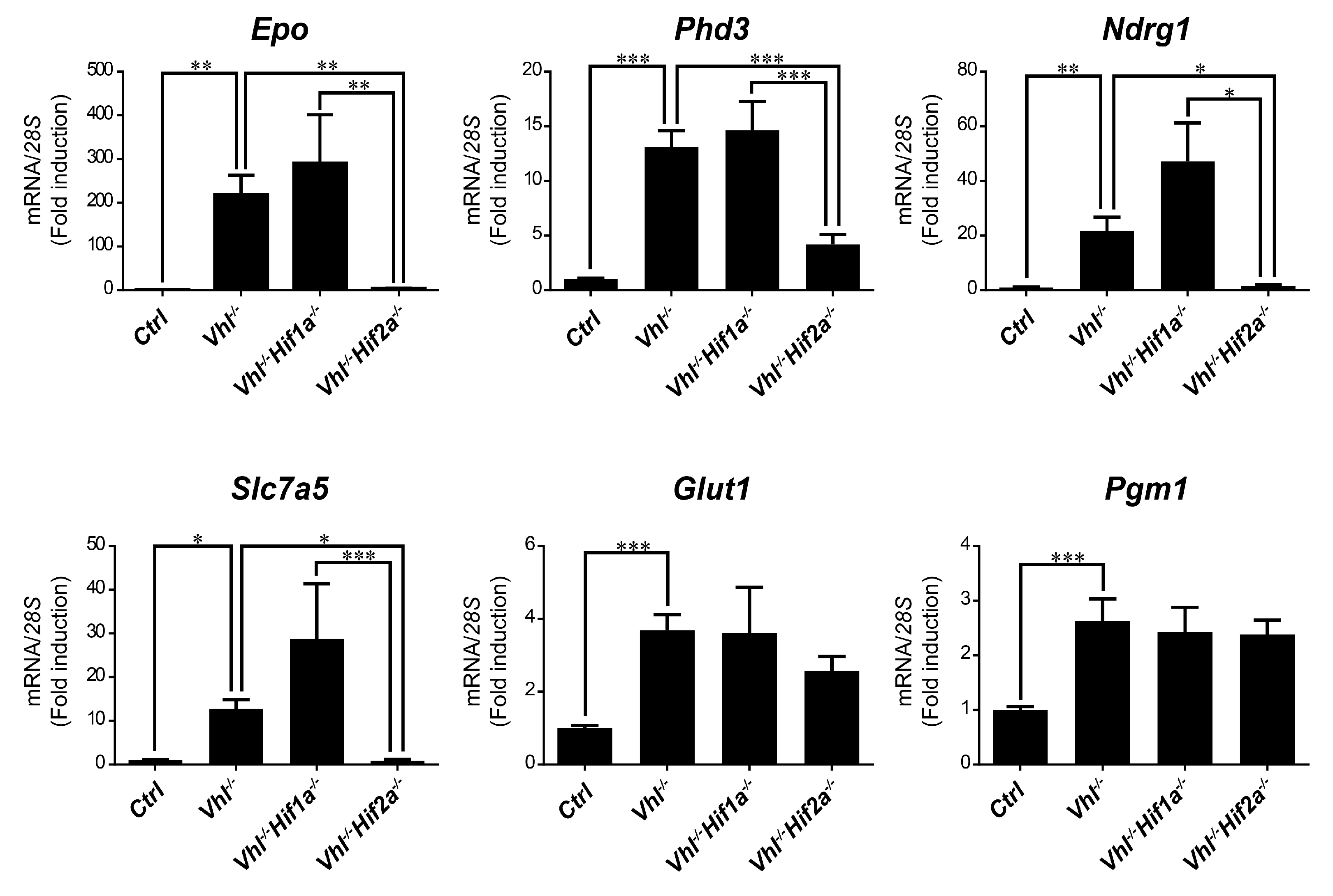

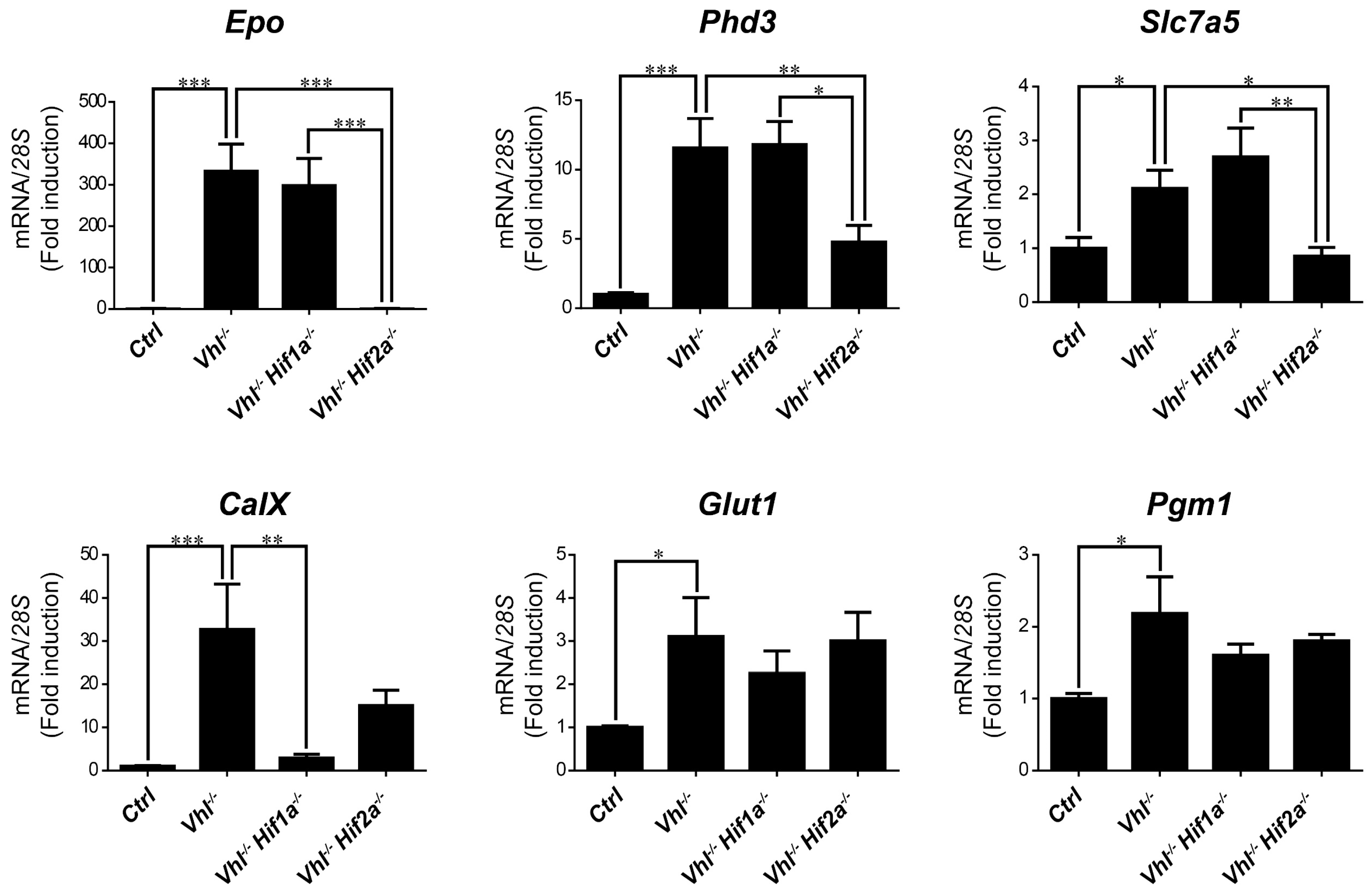

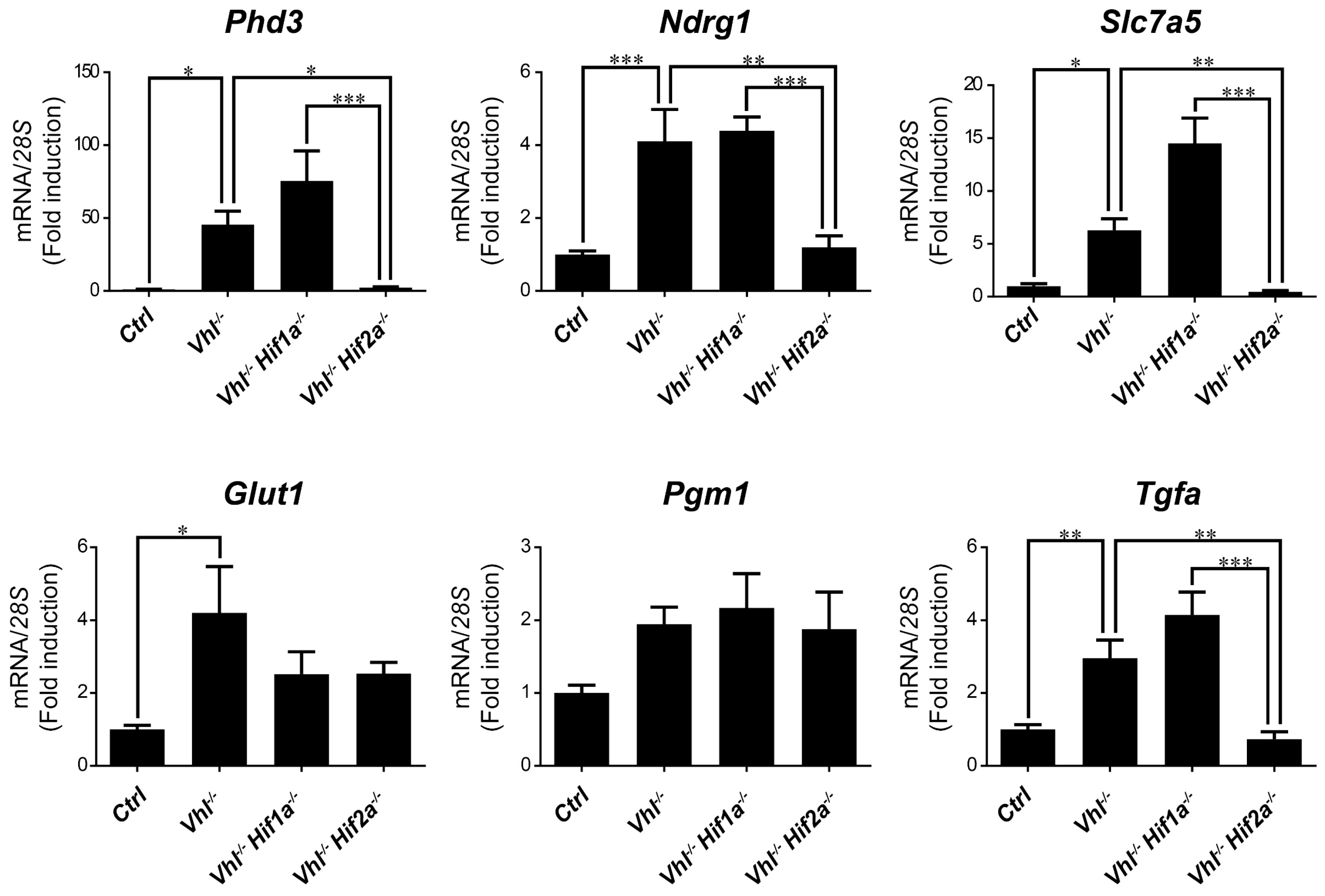

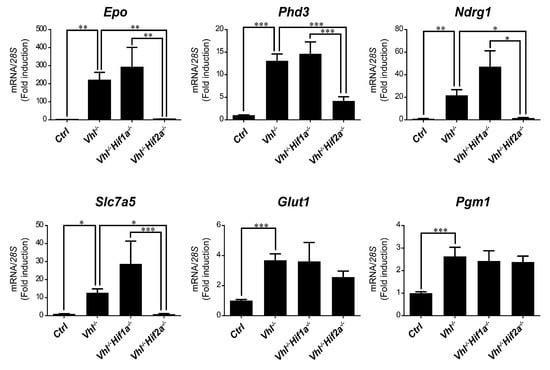

2.3. HIF1α and HIF2α Selectivity in Vhl-Deficient Tissues

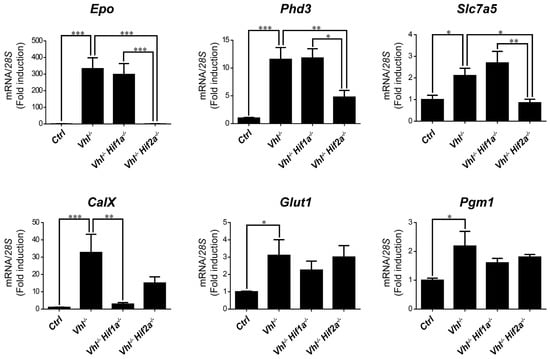

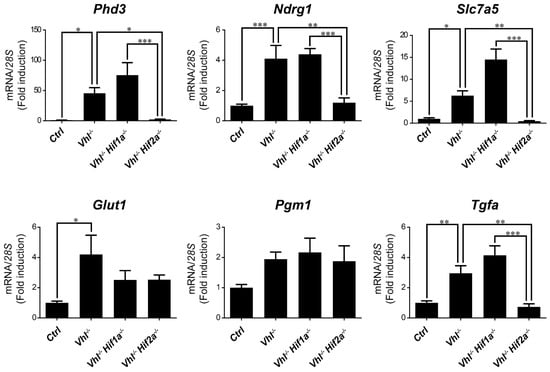

We then asked whether HIF1α and HIF2α selectivity in WT8 RCC cells was also conserved in vivo upon HIF activation in mouse tissues. To this end, we generated adult UBC-Cre-ERT2 VhlLoxP/LoxP-mice (here on are referred to as Vhl−/−), in which the expression of Vhl can be acutely inactivated globally (Supplementary Figure S1), leading to constitutive HIF1α and HIF2α activation [28,43]. In addition, we also generated Vhl−/−Hif1a−/− and Vhl−/−Hif2a−/− mice in which Vhl and Hif1a or Hif2a can be inactivated simultaneously, allowing us to investigate the potential target gene specificity for either HIF isoform (Supplementary Figure S1). As a positive control we first analyzed erythropoietin (Epo) mRNA levels in liver and kidney tissue. In line with previous studies Epo and mRNA levels are markedly induced in Vhl−/− liver (Figure 3) and kidney (Figure 4) through HIF2α isoform [17,44,45,46]. We also found that the expression of Phd3 was induced consistently in the liver, kidney and lung of both Vhl−/− and Vhl−/−Hif1a−/− mice (Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5), indicating that the induction of Phd3 in vivo was not driven by the HIF1α isoform in these three tissues (Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5). However, elevated expression of Phd3 was markedly reduced in Vhl−/−Hif2a−/− mice (Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5), indicating that the HIF-dependent expression of Phd3 in the liver, kidney and lung was driven by the HIF2α isoform, as in WT8 cells. In line with our previous study [28], we also found that Slc7a5 expression was preferentially induced by the HIF2α isoform in the liver, kidney and lung of Vhl−/− mice (Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5), as observed in WT8 cells. However, it should be noted that the increase in Slc7a5 expression in the kidney tissue takes place to a lesser extent when compared with the liver and lung tissue (Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5). Moreover, Tgfa expression was only induced in the lung tissue of Vhl−/− mice preferentially by the HIF2α isoform (Figure 5). Furthermore, Ndrg1 expression was markedly induced in the Vhl−/− liver and lung tissue through the HIF2α isoform (Figure 3 and Figure 5). Therefore, Tgfa and Ndrg1 displayed a similar HIF2α specificity in these tissues as in renal cell carcinoma WT8 cells but not induced in the Vhl-deficient kidney tissue (see discussion). In contrast, CaIX expression was markedly in Vhl−/− kidney tissue and reduced to a larger extent in the kidney tissue of Vhl−/−Hif1a−/− than Vhl−/−Hif2a−/− mice (Figure 4). These data suggest that CaIX expression is largely controlled by HIF1α in line with data obtained in WT8 cells. Furthermore, while Glut1 expression was induced in the liver, kidney and lung of Vhl−/− mice, its expression was not significantly reduced in both Vhl−/−Hif2a−/− and Vhl−/−Hif1a−/− mice although a trend to be reduced is observed in the liver of Vhl−/−Hif2a−/− mice, the kidney of Vhl−/−Hif1a−/− mice as well as the lung of Vhl−/−Hif2a−/− and Vhl−/−Hif1a−/− mice (Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5). Pgm1 expression showed a significant induction in Vhl−/− liver and kidney tissue (Figure 3 and Figure 4) and a trend in Vhl−/− lung tissue (Figure 5). Similar to Glut1, the expression of Pgm1 in the liver and kidney was not affected when compared Vhl−/− with Vhl−/−Hif2a−/− and Vhl−/−Hif1a−/− mice (Figure 3 and Figure 4). These data suggest that both HIF1α and HIF2α isoforms might contribute to Glut1 and Pgm1 expression in Vhl−/− mouse tissues analyzed. Therefore, the HIF selectivity of Glut1 and Pgm1 appeared to differ in human WT8 cells to that in mouse tissues of Vhl−/− mice.

Figure 3.

Target gene selectivity for HIF1α or HIF2α in the liver of Vhl−/− mice. Relative Epo, Phd3, Ndrg1, Slc7a5, Glut1 and Pgm1 expression in the liver of Vhl−/− mice (n = 13–14), Vhl−/−Hif1a−/− mice (n = 5–7), Vhl−/−Hif2a−/− mice (n = 12) and the corresponding controls (n = 15–18). Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001.

Figure 4.

Target gene selectivity for HIF1α or HIF2α in the kidney of Vhl−/− mice. Relative Epo, Phd3, Slc7a5, CaIX, Glut1 and Pgm1 expression in the kidney of Vhl−/− mice (n = 6), Vhl−/−Hif1a−/− mice (n = 3), Vhl−/−Hif2a−/− mice (n = 5) and the corresponding controls (n = 8–10). Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001.

Figure 5.

Target gene selectivity for HIF1α or HIF2α in the lung of Vhl−/− mice. Relative Phd3, Ndrg1, Slc7a5, Glut1, Pgm1 and Tfga expression in the lung of Vhl−/− mice (n = 4–6), Vhl−/−Hif1a−/− mice (n = 5), Vhl−/−Hif2a−/− mice (n = 7) and the corresponding controls (n = 5–6). Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001.

Together these data indicate a different contribution of the bHLH-PAS and NTAD/CTAD halves of HIF1α and HIF2α isoforms to the specific activity of these factors on their target genes. Moreover, we show that HIF target selectivity is conserved for some—not all—genes when compared to in vivo mouse tissues and a WT8 renal cell carcinoma cell model.

3. Discussion

The HIF1α and HIF2α isoforms are central factors in the cellular response to hypoxia. However, HIF1α and HIF2α do not affect all HIF-dependent genes equally. This phenomenon has been investigated in VHL-deficient RCC cells characterized by the constitutive activation of HIF1α and HIF2α isoforms, and where each isoform has a distinct biological output. Indeed, some HIF-dependent genes like CAIX are preferentially induced by the HIF1α isoform in these RCC cells while other genes like PHD3 are preferentially induced by the HIF2α isoform [12,13,27,31,33,35].

In this study we show that HIF isoforms specifically target some genes in an RCC model (WT8 cells), as also manifested in other Vhl-deficient biological settings in vivo. Indeed, expression of the Slc7a5 and Phd3 genes is preferentially induced by the HIF2α isoform in the liver, kidney and lung of Vhl deficient mice. In addition, Tgfa and Ndrg1 expression is also preferentially induced by HIF2α but not in all the tissues analyzed. In this line Tgfa and Ndrg1 expression is induced by HIF2α in renal cell carcinoma WT8 cells while is not induced in Vhl−/− kidneys. It cannot be ruled out that Tgfa and Ndrg1 expression might be induced in some particular renal cell types in Vhl−/− kidneys and therefore could not be detected in this RNA analysis in the whole kidney tissue. Along this line, higher expression of CaIX, Phd3, Slc7a5, Glut1, Pgm1 occurred but not Ndrg1 in a Vhl-deficient renal cell mouse model when compared with non-tumor renal region, which is in line with our data in Vhl-deficient kidneys [47]. This study detected an elevated expression of Tgfa. This tumor model is a different biological setting than our Vhl deficient kidneys. In this line, it might be considered that these tumors are characterized by a specific ccRCC immune microenvironment and that Vhl gene inactivation by itself is not enough to initiate the generation of a renal cell carcinoma [48,49,50], which might explain the differences between these two models regarding Tgfa expression. Other HIF-dependent genes show different HIF target specificity in mice than in human WT8 cells. For example, GLUT1 gene expression is preferentially controlled by HIF2α activity in WT8 cells while PGM1 is preferentially induced by HIF1α isoform. However, our data also show that elevated Glut1 and Pgm1 expression in the Vhl-deficient mouse tissues analyzed is not significantly reduced upon Hif1a or Hif2a inactivation, which suggest that both isoforms might be competent to induce Glut1 and Pgm1 in both tissues. Along this line, in contrast to renal cell carcinoma cells, GLUT1 expression has also been shown to be controlled by HIF1α in Hep3B cells [13,32]. Furthermore, SLC7A5 is preferentially induced by HIF2α in VHL-deficient RCC cells, and in Vhl-deficient liver and lung tissue [28,51]. Moreover, HIF2α controls SLC7A5 expression in other biological settings, such as neuroblastoma cells [52,53]. In addition, SLC7A5 expression is consistently induced in a panel of breast cancer cell lines subjected to hypoxia [54]. However, glioblastoma cells not only induce SLC7A5 in response to hypoxia through HIF2α but also, the HIF1α isoform is involved in its expression [55]. The molecular basis of this contrasting HIF selectivity of certain HIF-dependent genes remains unknown. Previous data and those presented here suggest that tissue (or cell) specific factors may influence the participation of HIF1 or HIF2 factors in the regulation of some HIF-dependent genes. In addition the relative abundance of the HIF1α and HIF2α isoforms in each cell type may also contribute in some extent to this HIF target selectivity, particularly if we take into consideration the distinct patterns of HIF1α and HIF2α tissue-specific expression [2,56]. Moreover, differences in HIF selectivity between human and mouse cells cannot be ruled out for some particular HIF-dependent genes.

Previous studies showed that HIF1 target specificity for genes like CAIX or phosphoglycerate kinase 1 (PGK1) cannot simply be explained by the preferential binding of HIF1α to the HRE of these two target genes [13,31]. Indeed, HIF2α binds to the HRE of these two genes in hypoxic cells or in VHL-deficient RCC cells [13,31]. Along similar lines, a HIF chimeric protein that contains the bHLH-PAS of HIF1α coupled to the NTAD/CTAD region of HIF2α cannot induce CAIX or PGK1 gene expression in HEK293 cells or RCC cells [13,31,32], highlighting the relevance of the HIF1α NTAD/CTAD region to explain HIF1α target selectivity. Consistent with these data, we also show that a similar HIF (P-A)2 (N2/C1) construct cannot induce CAIX expression but also, that of other HIF1α target genes like BNIP3 and PGM1. Furthermore, the NTAD region appears to be essential to explain HIF1α target selectivity [13,31,32]. Conversely, a HIF chimeric protein including the bHLH-PAS of HIF2α and the NTAD/CTAD region of HIF1α was sufficient to induce PGK1 gene transcription in HEK293 cells [13]. These data suggest that the selective PGK1 expression driven by the HIF1α isoform can largely be explained by the NTAD in HIF1α. However, our data show that the HIF chimera that includes the bHLH-PAS of HIF2α and the NTAD/CTAD region of HIF1α was not capable of inducing CAIX, BNIP3 and PGM1 expression in WT8 cells. Two independent studies found similar data regarding CAIX expression in 786-O RCC and HEK293 cells [31,32]. These data suggest that the bHLH/PAS region may also be relevant to confer HIF1α selectivity to some genes like CAIX, BNIP3 and PGM1. In this context, the HIF1α and HIF2α isoform may also show different DNA binding patterns for some genes [57,58] and therefore, some but not all HIF1α selective genes like BNIP3 or PGM1 might not bind the HIF2α isoform at their respective promoters. In this line, HIF1α binding to DNA is associated with histone H3K4me3 modifications while HIF2α associates with H3K4me1 [57]. Regarding the additional factors that might help HIF1α to achieve target selectivity, the involvement of the STAT3 transcription factor has been proposed. STAT3 can be recruited specifically to the promoters of HIF1α target genes like CAIX, where it contributes to specific HIF1α gene expression [32,59]. Thus, it is possible that STAT3 may also participate in the induction of other HIF1-dependent genes, such as BNIP3 and PGM1.

Previous studies have shown that HIF chimeras that include the HIF1 bHLH-PAS and the HIF2 NTAD/CTAD region induce HIF2α targets genes like PHD3, PAI-1 or adrenomedulin (ADM) [13,31,32]. We extended this analysis in WT8 cells to other HIF2 target genes like OCT-4, NDRG1, TFGA, GLUT1, CCND1 and SLC7A5. We first found that the expression of these HIF2α target genes is not induced or minimally affected by a chimeric HIF construct that contains the HIF2α bHLH-PAS half and the HIF1α NTAD/CTAD half of the protein. By contrast, a HIF chimera that contains the HIF1α bHLH-PAS half and the HIF2α NTAD/CTAD half is sufficient to induce in a different extent all the HIF2α target genes analyzed, including the amino acid carrier SLC7A5, a HIF2α target gene previously identified in different biological settings [28]. However, it should be noted that some of the genes analyzed such as OCT-4 and NDRG1 are induced by this chimera to a lesser extent than other HIF2α-dependent genes. These data suggest that the relative contribution of the NTAD/CTAD region of HIF2α to confer target selectivity can be different in each HIF2α-dependent gene. The upstream stimulatory factor 2 (USF2) has been involved in the specific HIF2-dependent expression of EPO and SERPINE1, involving a physical interaction between the USF2 and the HIF2α NTAD/CTAD region [32,60]. Therefore, it is also possible that USF2 also participates in the HIF2α-dependent expression of PHD3, OCT-4, NDRG1, TGFA, GLUT1, CCND1 and SLC7A5 in renal cell carcinoma. It should be noted that the HIF chimera that contains the HIF1α bHLH-PAS half and the HIF2α NTAD/CTAD half partially induces the expression of most of the HIF2-dependent genes partially, except PHD3 that is induced with this chimera at higher levels than HIF2α (P-A)2. These data suggest that the HIF2 NTAD/CTAD half might be not sufficient to achieve full HIF2 activity for some HIF2α-dependent genes. However, as indicated above the HIF (P-A)2 (N1/C2) construct is routinely expressed more weakly than HIF2α (P-A)2, which might also explain the partial induction of HIF2 target genes by the HIF (P-A)2 (N1/C2) construct. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out that the induction of a full HIF2 response requires both the HIF2α bHLH-PAS and NTAD/CTAD halves to be present. In this line, it has been proposed that the ETS-1 transcription factor confers HIF2 selectivity by interacting with the bHLH-PAS half of the HIF2α isoform [61]. In addition to ETS-1, Elk-1 is another transcription factor of the ETS family that has been proposed to participate in HIF2 specificity. Again, it is conceivable that the participation of the HIF2 bHLH-PAS region in HIF2 specificity may involve its interaction with ETS-1 and possibly provides a molecular basis of the distinct DNA binding of HIF1α and HIF2α in some HIF-dependent genes referred to above [57].

In general, our data extend the analysis of HIF selectivity to in vivo mouse biological settings where we show that HIF target selectivity can be conserved for some—not all—genes such as SLC7A5, NDRG1 or TGFA between human and mouse cells. These data suggest that mechanisms that assure HIF selectivity seem to be conserved during evolution, which might reflect the biological relevance of HIF target specificity. Furthermore, we have shown the involvement of HIF1 bHLH/PAS and NTAD/CTAD regions to confer HIF1α selectivity for the genes analyzed and the major relevance of HIF2α NTAD/CTAD region to understand HIF2 target gene specificity. Further studies will be necessary to understand the conserved molecular basis of HIF target gene selectivity especially using in vivo biological settings.

4. Methods

4.1. Cell Lines and Cell Culture Conditions

The HEK293T and WT8 cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco’s high glucose modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM: HyClone, GE HealthCare, Chicago, IL, USA) supplemented with 100 units/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 20 mM HEPES and 10% fetal bovine serum (U.S.) (FBS: HyClone, GE HealthCare, Chicago, IL, USA). Cells were maintained at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2/95% air (normoxic conditions).

4.2. DNA Plasmid Construction

To generate chimeric HIFα versions, a novel XbaI restriction site was introduced on aa 411 of HA-HIF1α-P402A/P564A and in aa414 of HA-HIF2α-P405A/P531A [62]. For this purpose the N-terminal half of pBabe-puro HA-HIF1α-P402A/P564A (1 to 411) was amplified using a forward primer including an ApaI site (forward, 5′-TTCTCTAgggccc(ApaI)GGCCGGAT-3′) and a reverse primer including an XbaI site (reverse, 5′-TCGTTGCTGCCAAAAtctaga(XbaI)GATATGATTGTGTCTCC-3′). The C-terminal half of pBabe-puro HA-HIF1α-P402A/P564A (412 to 826) was amplified using a forward primer including an XbaI site (forward, 5′-GGAGACACAATCATATCtctaga(XbaI)TTTTGGCAGCAACGA-3′) and a reverse primer including an XbaI site (reverse, 5′-TAACTGACACACATtctaga(XbaI)GGGTCGACCACTGT-3′). The N-terminal half of pBabe-puro HA-HIF2α-P405A/P531A (1 to 414) was amplified using a forward primer including an ApaI site (forward, 5′-TTCTCTAgggccc(ApaI)GGCCGGAT-3′) and a reverse primer including an XbaI site (reverse, 5′-GTTCTGATTCCCGAAAtctaga(XbaI)GAGATGATGGCG-3′). The C-terminal half of pBabe-puro HA-HIF2α-P405A/P531A (415 to 870) was amplified using a forward primer including an XbaI site (forward, 5′-CGCCATCATCTCtctaga(XbaI)TTTCGGGAATCAGAAC-3′) and a reverse primer including an XbaI site (reverse, 5′- TAACTGACACACATtctaga(XbaI)GGGTCGACCACTGT-3′). After confirmation by DNA sequencing each of these four amplicons werecloned in the pCR™2.1-TOPO™ vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Then the N-terminal regions of HA-HIF1α-P402A/P564A and HA-HIF2α-P405A/P531A were excised with ApaI–XbaI to be cloned in pLVX–Puro lentiviral expression vector. Finally, the C-terminal region of HA-HIF1α-P402A/P564A was excised with XbaI–XbaI to be cloned in the pLVX lentiviral expression vector harboring the N-terminal region of HA-HIF2α-P405A/P531A. Similarly, the C-terminal region of HA-HIF2α-P405A/P531A was excised with XbaI–XbaI to be cloned in the pLVX–Puro lentiviral expression vector harboring the N-terminal region of HA-HIF1α-P402A/P564A.

4.3. Lentiviral Infection

For lentiviral infection, HEK293T cells were seeded in p100 plates, and transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) with 3.9 μg of pLP1, 2.7 μg of pLP2, 3.3 μg of VSVg and 9.9 μg of each lentiviral vector. Cell culture supernatants were harvested 24 h after transfection, filtered through a 0.45 μm pore filter, and added to WT8 cells along with 8 μg/mL polybrene (final concentration). This step was repeated over the next 2 days and the cells were then selected with 1 mg/mL puromycin to obtain polyclonal resistant cell pools.

4.4. Western Blotting and Antibodies

Cells were lysed in Laemmli buffer, and the protein extract was resolved on 10% or 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to 0.45 μm nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were then blocked and probed with antibodies against: HIF2α (ab199, Abcam); HIF1α (610959, BD Transduction Laboratories, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA); β-actin (A3854, Sigma, Saint Louis, MO, USA). Antibody binding was detected by enhanced chemiluminiscence (Clarity, BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA; and SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and visualized on a digital luminescent image analyzer (Image Quant LAS4000 Mini; GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA).

4.5. RNA Extraction, RT-PCR Analysis and Primers

Total RNA from the cells was isolated using Ultraspec or TRIsure (BIO-38032, Bioline USA, Inc., Cincinnati, OH, USA). This RNA (1 µg) was then reverse-transcribed using Improm-II reverse transcriptase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplifications were performed using the Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) in a QuantStudio5 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Primer sets used are included in Supplementary Table S1. The data were analyzed with QuantStudio5 Design and Analysis Software v1.4 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

4.6. Mouse Models

C;129S-Vhltm1Jae/J (stock no. 4081, Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) were used to generate the UBC-Cre-ERT2 VhlLoxP/LoxP mice. These mice harbor two loxP sites flanking the promoter and exon 1 of the murine Vhl locus [63]. The C;129S-Vhltm1Jae/J mice were crossed with B6.Cg-Ndor1Tg(UBC-cre/ERT2)1Ejb/1J or UBC-Cre-ERT2 mice (Jackson Laboratories, stock no. 008085) that ubiquitously express a tamoxifen-inducible Cre recombinase (Cre-ERT2) [64]. UBC-Cre-ERT2 VhlLoxP/LoxP mice were generated through the appropriate crosses, along with the corresponding control mice. Then UBC-Cre-ERT2 VhlLoxP/LoxPHif1aLoxP/LoxP mice were generated using B6.129-Hif1atm3Rsjo/J mice (Jackson Laboratories, stock no. 007561) that harbor two loxP sites flanking exon 2 of the murine Hif1a locus [65]. These mice were then crossed with B6.Cg-Ndor1Tg(UBC-cre/ERT2)1Ejb/1J mice as described above to generate UBC-Cre-ERT2 Hif1aLoxP/LoxP mice, which were subsequently crossed with C;129S-Vhltm1Jae/J mice to generate UBC-Cre-ERT2 VhlLoxP/LoxPHif1aLoxP/LoxP mice and their corresponding control mice. The UBC-Cre-ERT2 VhlLoxP/LoxPHif2aLoxP/LoxP mice were generated through the appropriate crosses using Epas1tm1Mcs/J mice (Jackson Laboratories, stock no. 008407) [66].

4.7. Ethics Statements

All experimental procedures involving mice were first approved by the research ethics committee at the Autonomous University of Madrid (UAM) (CEIC 55-1002-A049, approval date 9 May 2014 and CEIC 103-1993 -341 approval date 25 November 2019), and they were carried out under the supervision of animal welfare responsible at the UAM in accordance with Spanish RD 53/2013 and European (EU Directive 2010/63/EU) guidelines.

4.8. Statistical Analysis

Data were expressed as the mean ± SEM (standard error of the mean), and the differences between groups were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software (San Diego, CA, USA).

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/21/24/9401/s1.

Author Contributions

A.B. and F.M.-R. and A.A.U. conducted all the experiments. J.A. was involved in the design of the experiments, data analysis, and writing the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from Ministerio de Economia y Competitividad (SAF2016-76815-R and SAF2017-90794-REDT), Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (PID2019-106371RB-I00) and Fundació La Marató de TV3 (534/C/2016). A.A.U is supported by the CAM “Atracción de Talento” program and Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, grant SI1/PJI/2019-00399.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank W.G. Kaelin (Medical Oncology/Molecular and Cellular Department, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA) for providing the vectors encoding HIF1α P402A;P564A, HIF2α P405A;P531A and the corresponding control. We also thank Chris W. Pugh (Nuffield Department of Medicine, University of Oxford) for his help in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wang, G.L.; Jiang, B.H.; Rue, E.A.; Semenza, G.L. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is a basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS heterodimer regulated by cellular O2 tension. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 5510–5514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; McKnight, S.L.; Russell, D.W. Endothelial PAS domain protein 1 (EPAS1), a transcription factor selectively expressed in endothelial cells. Genes Dev. 1997, 11, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruick, R.K.; McKnight, S.L. A conserved family of prolyl-4-hydroxylases that modify HIF. Science 2001, 294, 1337–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, A.C.R.; Gleadle, J.M.; McNeill, L.A.; Hewitson, K.S.; O’Rourke, J.; Mole, D.R.; Mukherji, M.; Metzen, E.; Wilson, M.I.; Dhanda, A.; et al. C. elegans EGL-9 and mammalian homologs define a family of dioxygenases that regulate HIF by prolyl hydroxylation. Cell 2001, 107, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivan, M.; Kondo, K.; Yang, H.; Kim, W.; Valiando, J.; Ohh, M.; Salic, A.; Asara, J.M.; Lane, W.S.; Kaelin, W.G., Jr. HIFα targeted for VHL-mediated destruction by proline hydroxylation: Implications for O2 sensing. Science 2001, 292, 464–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaakkola, P.; Mole, D.R.; Tian, Y.M.; Wilson, M.I.; Gielbert, J.; Gaskell, S.J.; Von Kriegsheim, A.; Hebestreit, H.F.; Mukherji, M.; Schofield, C.J.; et al. Targeting of HIF-α to the von Hippel-Lindau ubiquitylation complex by O2-regulated prolyl hydroxylation. Science 2001, 292, 468–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.H.; Rue, E.; Wang, G.L.; Roe, R.; Semenza, G.L. Dimerization, DNA binding, and transactivation properties of hypoxia- inducible factor 1. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 17771–17778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratcliffe, P.J.; O’Rourke, J.F.; Maxwell, P.H.; Pugh, C.W. Oxygen sensing, hypoxia-inducible factor-1 and the regulation of mammalian gene expression. J. Exp. Biol. 1998, 201, 1153–1162. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Barahona, A.; Villar, D.; Pescador, N.; Amigo, J.; del Peso, L. Genome-wide identification of hypoxia-inducible factor binding sites and target genes by a probabilistic model integrating transcription-profiling data and in silico binding site prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenza, G.L. Hypoxia-inducible factors in physiology and medicine. Cell 2012, 148, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaelin, W.G.; Ratcliffe, P.J. Oxygen Sensing by Metazoans: The Central Role of the HIF Hydroxylase Pathway. Mol. Cell 2008, 30, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, C.-J.; Wang, L.-Y.; Chodosh, L.A.; Keith, B.; Simon, M.C. Differential Roles of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1α (HIF-1α) and HIF-2α in Hypoxic Gene Regulation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003, 23, 9361–9374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, C.J.; Sataur, A.; Wang, L.; Chen, H.; Simon, M.C. The N-terminal transactivation domain confers target gene specificity of hypoxia-inducible factors HIF-1α and HIF-2α. Mol. Biol. Cell 2007, 18, 4528–4542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyer, N.V.; Kotch, L.E.; Agani, F.; Leung, S.W.; Laughner, E.; Wenger, R.H.; Gassmann, M.; Gearhart, J.D.; Lawler, A.M.; Yu, A.Y.; et al. Cellular and developmental control of O2 homeostasis by hypoxia- inducible factor 1α. Genes Dev. 1998, 12, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenza, G.L.; Roth, P.H.; Fang, H.M.; Wang, G.L. Transcriptional regulation of genes encoding glycolytic enzymes by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 23757–23763. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, H.; Liu, Q.; Binns, T.C.; Urrutia, A.A.; Davidoff, O.; Kapitsinou, P.P.; Pfaff, A.S.; Olauson, H.; Wernerson, A.; Fogo, A.B.; et al. Distinct subpopulations of FOXD1 stroma-derived cells regulate renal erythropoietin. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 1926–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankin, E.B.; Biju, M.P.; Liu, Q.; Unger, T.L.; Rha, J.; Johnson, R.S.; Simon, M.C.; Keith, B.; Haase, V.H. Hypoxia-inducible factor-2 (HIF-2) regulates hepatic erythropoietin in vivo. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 1068–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidemann, A.; Johnson, R.S. Nonrenal Regulation of EPO Synthesis. Kidney Int. 2009, 75, 682–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrutia, A.A.; Afzal, A.; Nelson, J.; Davidoff, O.; Gross, K.W.; Haase, V.H. Prolyl-4-hydroxylase 2 and 3 coregulate murine erythropoietin in brain pericytes. Blood 2016, 128, 2550–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeliet, P.; Dor, Y.; Herber, J.M.; Fukumura, D.; Brusselmans, K.; Dewerchin, M.; Neeman, M.; Bono, F.; Abramovitch, R.; Maxwell, P.; et al. Role of HIF-1α in hypoxiamediated apoptosis, cell proliferation and tumour angiogenesis. Nature 1998, 394, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordan, J.D.; Thompson, C.B.; Simon, M.C. HIF and c-Myc: Sibling Rivals for Control of Cancer Cell Metabolism and Proliferation. Cancer Cell 2007, 12, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, C.; Beroukhim, R.; Schumacher, S.E.; Zhou, J.; Chang, M.; Signoretti, S.; Kaelin, W.G. Genetic and functional studies implicate HIF1a as a 14q kidney cancer suppressor gene. Cancer Discov. 2011, 1, 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubbi, M.E.; Kshitiz; Gilkes, D.M.; Rey, S.; Wong, C.C.; Luo, W.; Kim, D.H.; Dang, C.V.; Levchenko, A.; Semenza, G.L. A nontranscriptional role for HIF-1α as a direct inhibitor of DNA replication. Sci. Signal. 2013, 6, ra10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordan, J.D.; Bertout, J.A.; Hu, C.J.; Diehl, J.A.; Simon, M.C. HIF-2α Promotes Hypoxic Cell Proliferation by Enhancing c-Myc Transcriptional Activity. Cancer Cell 2007, 11, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordan, J.D.; Lal, P.; Dondeti, V.R.; Letrero, R.; Parekh, K.N.; Oquendo, C.E.; Greenberg, R.A.; Flaherty, K.T.; Rathmell, W.K.; Keith, B.; et al. HIF-α Effects on c-Myc Distinguish Two Subtypes of Sporadic VHL-Deficient Clear Cell Renal Carcinoma. Cancer Cell 2008, 14, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondo, K.; Klco, J.; Nakamura, E.; Lechpammer, M.; Kaelin, W.G. Inhibition of HIF is necessary for tumor suppression by the von Hippel-Lindau protein. Cancer Cell 2002, 1, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raval, R.R.; Lau, K.W.; Tran, M.G.B.; Sowter, H.M.; Mandriota, S.J.; Li, J.L.; Pugh, C.W.; Maxwell, P.H.; Harris, A.L.; Ratcliffe, P.J. Contrasting Properties of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1 (HIF-1) and HIF-2 in von Hippel-Lindau-Associated Renal Cell Carcinoma. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005, 25, 5675–5686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elorza, A.; Soro-Arnáiz, I.; Meléndez-Rodríguez, F.; Rodríguez-Vaello, V.; Marsboom, G.; de Cárcer, G.; Acosta-Iborra, B.; Albacete-Albacete, L.; Ordóñez, A.; Serrano-Oviedo, L.; et al. HIF2α Acts as an mTORC1 Activator through the Amino Acid Carrier SLC7A5. Mol. Cell 2012, 48, 681–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, K.; Gunaratnam, L.; Morley, M.; Franovic, A.; Mekhail, K.; Lee, S. Silencing of epidermal growth factor receptor suppresses hypoxia-inducible factor-2-driven VHL-/- renal cancer. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 5221–5230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Rourke, J.F.; Tian, Y.M.; Ratcliffe, P.J.; Pugh, C.W. Oxygen-regulated and transactivating domains in endothelial PAS protein 1: Comparison with hypoxia-inducible factor-1α. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 2060–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, K.W.; Tian, Y.M.; Raval, R.R.; Ratcliffe, P.J.; Pugh, C.W. Target gene selectivity of hypoxia-inducible factor-α in renal cancer cells is conveyed by post-DNA-binding mechanisms. Br. J. Cancer 2007, 96, 1284–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawlus, M.R.; Wang, L.; Murakami, A.; Dai, G.; Hu, C.J. STAT3 or USF2 Contributes to HIF Target Gene Specificity. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e72358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, C.U.; von Stedingk, K.; Fredlund, E.; Bexell, D.; Påhlman, S.; Wigerup, C.; Mohlin, S. ARNT-dependent HIF-2 transcriptional activity is not sufficient to regulate downstream target genes in neuroblastoma. Exp. Cell Res. 2020, 388, 111845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, M.; Tanaka, T.; Maemura, K.; Uchiyama, T.; Sato, H.; Maeno, T.; Suga, T.; Iso, T.; Ohyama, Y.; Arai, M.; et al. The PAI-1 gene as a direct target of endothelial PAS domain protein-1 in adenocarcinoma A549 cells. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2004, 31, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Du, X.; Rizzi, J.P.; Liberzon, E.; Chakraborty, A.A.; Gao, W.; Carvo, I.; Signoretti, S.; Bruick, R.K.; Josey, J.A.; et al. On-target efficacy of a HIF-2α antagonist in preclinical kidney cancer models. Nature 2016, 539, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickey, M.M.; Richardson, T.; Wang, T.; Mosqueira, M.; Arguiri, E.; Yu, H.; Yu, Q.C.; Solomides, C.C.; Morrisey, E.E.; Khurana, T.S.; et al. The von Hippel-Lindau Chuvash mutation promotes pulmonary hypertension and fibrosis in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2010, 120, 827–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meléndez-Rodríguez, F.; Urrutia, A.A.; Lorendeau, D.; Rinaldi, G.; Roche, O.; Böğürcü-Seidel, N.; Ortega Muelas, M.; Mesa-Ciller, C.; Turiel, G.; Bouthelier, A.; et al. HIF1α Suppresses Tumor Cell Proliferation through Inhibition of Aspartate Biosynthesis. Cell Rep. 2019, 26, 2257–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, J.; Bellot, G.; Gounon, P.; Lacas-Gervais, S.; Pouysségur, J.; Mazure, N.M. Glycogen synthesis is induced in hypoxia by the hypoxia-inducible factor and promotes cancer cell survival. Front. Oncol. 2012, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Hill, H.; Christie, A.; Kim, M.S.; Holloman, E.; Pavia-Jimenez, A.; Homayoun, F.; Ma, Y.; Patel, N.; Yell, P.; et al. Targeting renal cell carcinoma with a HIF-2 antagonist. Nature 2016, 539, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Covello, K.L.; Kehler, J.; Yu, H.; Gordan, J.D.; Arsham, A.M.; Hu, C.J.; Labosky, P.A.; Simon, M.C.; Keith, B. HIF-2alpha regulates Oct-4: Effects of hypoxia on stem cell function, embryonic development, and tumor growth. Genes Dev. 2006, 20, 557–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betsunoh, H.; Fukuda, T.; Anzai, N.; Nishihara, D.; Mizuno, T.; Yuki, H.; Masuda, A.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Abe, H.; Yashi, M.; et al. Increased expression of system large amino acid transporter (LAT)-1 mRNA is associated with invasive potential and unfavorable prognosis of human clear cell renal cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer 2013, 13, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higuchi, K.; Sakamoto, S.; Ando, K.; Maimaiti, M.; Takeshita, N.; Okunushi, K.; Reien, Y.; Imamura, Y.; Sazuka, T.; Nakamura, K.; et al. Characterization of the expression of LAT1 as a prognostic indicator and a therapeutic target in renal cell carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miró-Murillo, M.; Elorza, A.; Soro-Arnáiz, I.; Albacete-Albacete, L.; Ordoñez, A.; Balsa, E.; Vara-Vega, A.; Vázquez, S.; Fuertes, E.; Fernández-Criado, C.; et al. Acute Vhl gene inactivation induces cardiac HIF-dependent erythropoietin gene expression. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e22589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minamishima, Y.A.; Kaelin, W.G. Reactivation of hepatic EPO synthesis in mice after PHD loss. Science 2010, 329, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, H.; Liu, J.; Urrutia, A.A.; Burmakin, M.; Ishii, K.; Rajan, M.; Davidoff, O.; Saifudeen, Z.; Haase, V.H. Hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl-4-hydroxylation in FOXD1 lineage cells is essential for normal kidney development. Kidney Int. 2017, 92, 1370–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scortegagna, M.; Morris, M.A.; Oktay, Y.; Bennett, M.; Garcia, J.A. The HIF family member EPAS1/HIF-2alpha is required for normal hematopoiesis in mice. Blood 2003, 102, 1634–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoefflin, R.; Harlander, S.; Schäfer, S.; Metzger, P.; Kuo, F.; Schönenberger, D.; Adlesic, M.; Peighambari, A.; Seidel, P.; Chen, C.Y.; et al. HIF-1α and HIF-2α differently regulate tumour development and inflammation of clear cell renal cell carcinoma in mice. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliopoulos, O.; Kibel, A.; Gray, S.; Kaelin, W.G. Tumour suppression by the human von Hippel-Lindau gene product. Nat. Med. 1995, 1, 822–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinot, A.; Lehmann, H.; Wild, P.J.; Frew, I.J. Combined deletion of Vhl, Trp53 and Kif3a causes cystic and neoplastic renal lesions. J. Pathol. 2016, 239, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harlander, S.; Schönenberger, D.; Toussaint, N.C.; Prummer, M.; Catalano, A.; Brandt, L.; Moch, H.; Wild, P.J.; Frew, I.J. Combined mutation in Vhl, Trp53 and Rb1 causes clear cell renal cell carcinoma in mice. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 869–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouthelier, A.; Aragonés, J. Role of the HIF oxygen sensing pathway in cell defense and proliferation through the control of amino acid metabolism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2020, 1867, 118733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onishi, Y.; Hiraiwa, M.; Kamada, H.; Iezaki, T.; Yamada, T.; Kaneda, K.; Hinoi, E. Hypoxia affects Slc7a5 expression through HIF-2α in differentiated neuronal cells. FEBS Open Biol. 2019, 9, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbet, C.; Draoui, N.; Polet, F.; Pinto, A.; Drozak, X.; Riant, O.; Feron, O. The SIRT1/HIF2α axis drives reductive glutamine metabolism under chronic acidosis and alters tumor response to therapy. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 5507–5519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morotti, M.; Bridges, E.; Valli, A.; Choudhry, H.; Sheldon, H.; Wigfield, S.; Gray, N.; Zois, C.E.; Grimm, F.; Jones, D.; et al. Hypoxia-induced switch in SNAT2/SLC38A2 regulation generates endocrine resistance in breast cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 12452–12461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Chen, Y.; Shi, X.; Zhou, M.; Bao, L.; Hatanpaa, K.J.; Patel, T.; DeBerardinis, R.J.; Wang, Y.; Luo, W. Regulation of branched-chain amino acid metabolism by hypoxia-inducible factor in glioblastoma. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiesener, M.S.; Jürgensen, J.S.; Rosenberger, C.; Scholze, C.K.; Hörstrup, J.H.; Warnecke, C.; Mandriota, S.; Bechmann, I.; Frei, U.A.; Pugh, C.W.; et al. Widespread hypoxia-inducible expression of HIF-2alpha in distinct cell populations of different organs. FASEB J. 2003, 17, 271–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smythies, J.A.; Sun, M.; Masson, N.; Salama, R.; Simpson, P.D.; Murray, E.; Neumann, V.; Cockman, M.E.; Choudhry, H.; Ratcliffe, P.J.; et al. Inherent DNA-binding specificities of the HIF-1α and HIF-2α transcription factors in chromatin. EMBO Rep. 2019, 20, e46401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schödel, J.; Mole, D.R.; Ratcliffe, P.J. Pan-genomic binding of hypoxia-inducible transcription factors. Biol. Chem. 2013, 394, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlus, M.R.; Wang, L.; Hu, C.J. STAT3 and HIF1α cooperatively activate HIF1 target genes in MDA-MB-231 and RCC4 cells. Oncogene 2014, 33, 1670–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlus, M.R.; Wang, L.; Ware, K.; Hu, C.J. Upstream stimulatory factor 2 and hypoxia-inducible factor 2α (HIF2α) cooperatively activate HIF2 target genes during hypoxia. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 32, 4595–4610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elvert, G.; Kappel, A.; Heidenreich, R.; Englmeier, U.; Lanz, S.; Acker, T.; Rauter, M.; Plate, K.; Sieweke, M.; Breier, G.; et al. Cooperative interaction of hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha (HIF-2alpha) and Ets-1 in the transcriptional activation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (Flk-1). J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 7520–7530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Q.; Bartz, S.; Mao, M.; Li, L.; Kaelin, W.G. The hypoxia-inducible factor 2alpha N-terminal and C-terminal transactivation domains cooperate to promote renal tumorigenesis in vivo. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 27, 2092–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haase, V.H.; Glickman, J.N.; Socolovsky, M.; Jaenisch, R. Vascular tumors in livers with targeted inactivation of the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 1583–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruzankina, Y.; Pinzon-Guzman, C.; Asare, A.; Ong, T.; Pontano, L.; Cotsarelis, G.; Zediak, V.P.; Velez, M.; Bhandoola, A.; Brown, E.J. Deletion of the developmentally essential gene ATR in adult mice leads to age-related phenotypes and stem cell loss. Cell Stem Cell 2007, 1, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, H.E.; Lo, J.; Johnson, R.S. HIF-1 alpha is required for solid tumor formation and embryonic vascularization. EMBO J. 1998, 17, 3005–3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, M.; Hu, C.J.; Johnson, R.S.; Brown, E.J.; Keith, B.; Simon, M.C. Acute postnatal ablation of Hif-2alpha results in anemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 2301–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).