Leptin, Adiponectin, and Sam68 in Bone Metastasis from Breast Cancer

Abstract

:1. Introduction

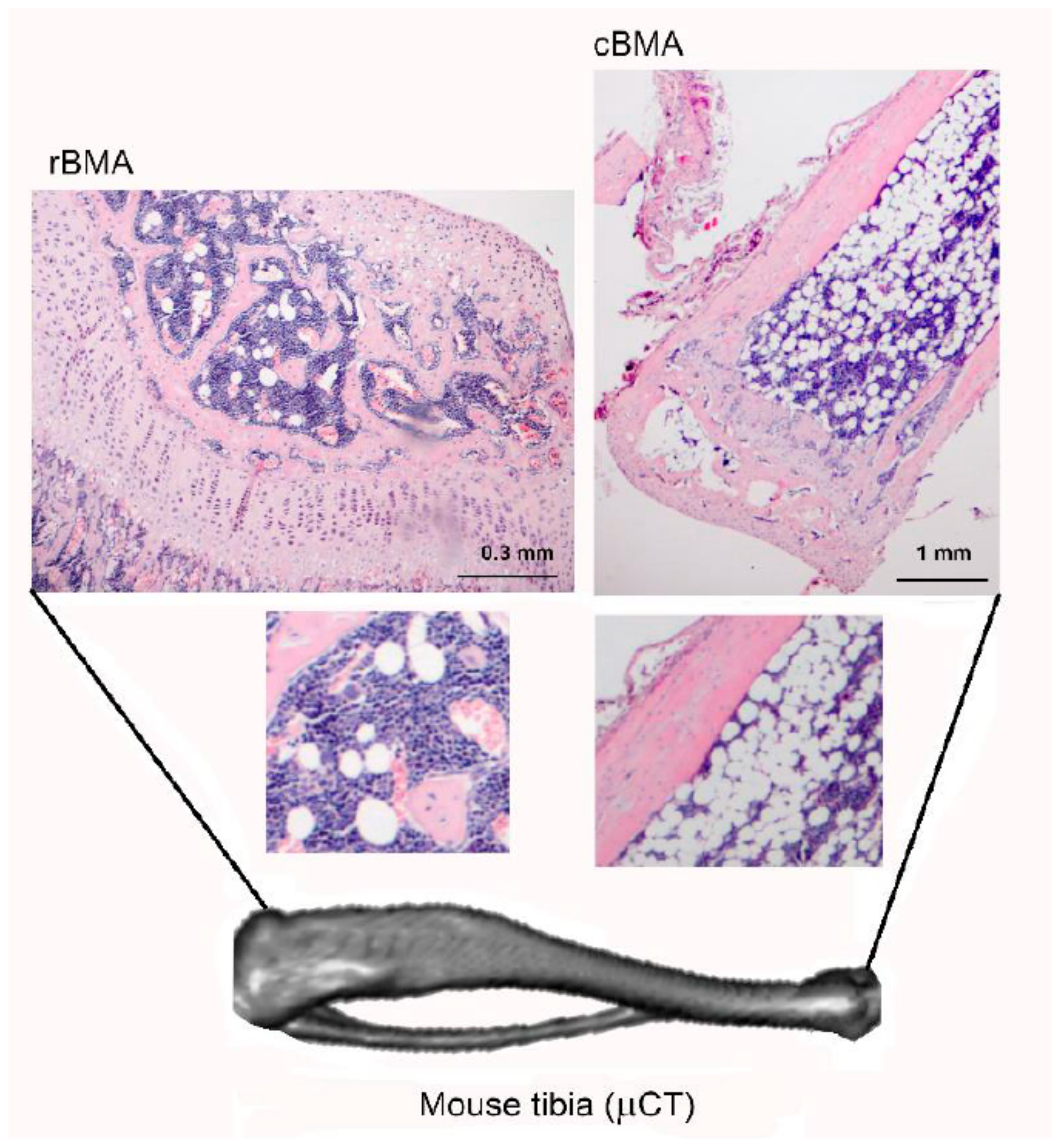

2. Bone Marrow Adipose Tissue (BMAT), the Third Fat Depot

3. Adipocytes as Source of Factors in Tumour Stroma: Adiponectin and Leptin

3.1. Adiponectin

Adiponectin and Breast Cancer/Bone Metastasis

3.2. Leptin

3.2.1. Leptin and Breast Cancer

3.2.2. Leptin and Bone Metastasis

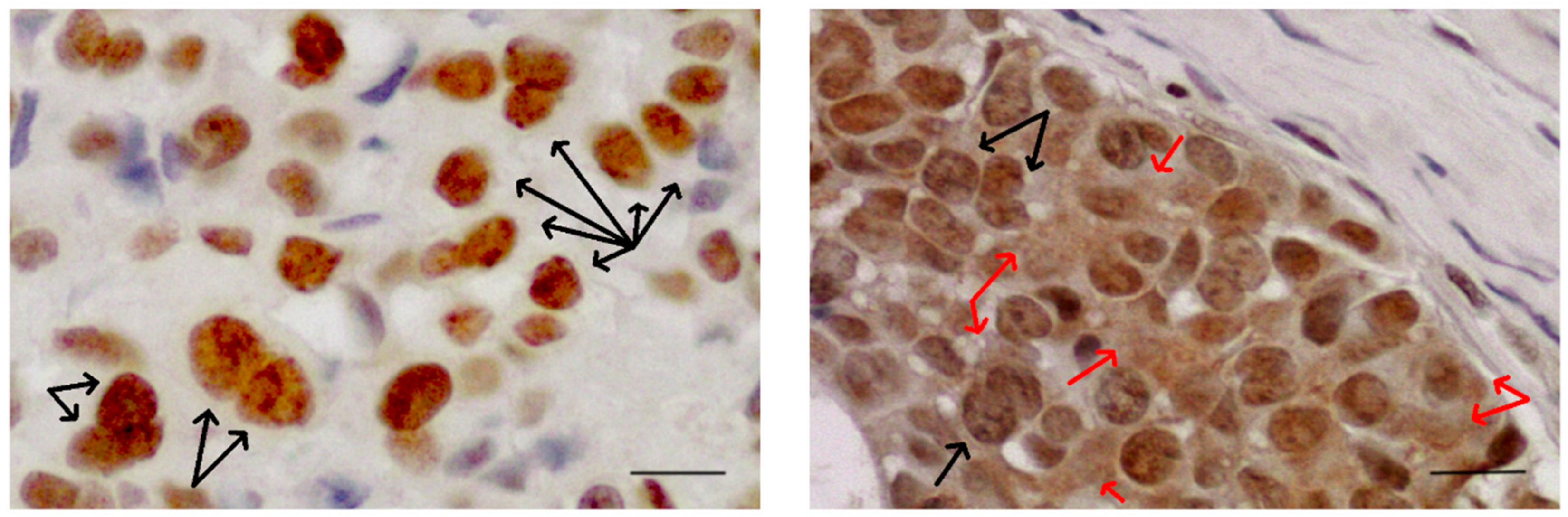

4. The RNA-Binding Protein Src-Associated in Mitosis of 68 kDa (Sam68)

5. Alternative Splicing Regulates EMT: Role of Sam68

6. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MSC | Mesenchymal stem cell |

| STAR | Signal Transduction and Activation of RNA |

| WAT | White adipose tissue |

| BAT | Brown adipose tissue |

| BMAT | Bone marrow adipose tissue |

| cBMA | Constitutive bone marrow adipocytes |

| rBMA | Regulated bone marrow adipocytes |

| PLOD2 | 2-oxoglutarate 5-dioxygenase 2 |

| AMPK | Adenosine-monophosphate activated protein kinase |

| LKB1 | Liver kinase B1 |

| Ob-R | Leptin receptor |

| BMSC | Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell |

| CSC | Cancer stem cell |

| NILCO | Notch, Interleukin-1, and leptin crosstalk outcome |

| EMT | Epithelial to mesenchymal transition |

| TAMs | Tumor-associate macrophages |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| sICAM | Soluble intercellular adhesion molecules |

| Sam68 | Src-associated in mitosis 68 |

| MET | Mesenchymal to epithelial transition |

| SRSF1 | Serine/arginine-rich splicing factor 1 |

References

- Caers, J.; Deleu, S.; Belaid, Z.; De Raeve, H.; Van Valckenborgh, E.; De Bruyne, E.; Defresne, M.P.; Van Riet, I.; Van Camp, B.; Vanderkerken, K. Neighbouring adipocytes participate in the bone marrow microenvironment of multiple myeloma cells. Leukemia 2007, 21, 1580–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brook, N.; Brook, E.; Dharmarajan, A.; Dass, C.R.; Chan, A. Breast cancer bone metastases: Pathogenesis and therapeutic targets. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2018, 96, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santini, D.; Tampellini, M.; Vincenzi, B.; Ibrahim, T.; Ortega, C.; Virzi, V.; Silvestris, N.; Berardi, R.; Masini, C.; Calipari, N.; et al. Natural history of bone metastasis in colorectal cancer: Final results of a large Italian bone metastases study. Ann. Oncol. 2012, 23, 2072–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santini, D.; Procopio, G.; Porta, C.; Ibrahim, T.; Barni, S.; Mazzara, C.; Fontana, A.; Berruti, A.; Berardi, R.; Vincenzi, B.; et al. Natural history of malignant bone disease in renal cancer: Final results of an Italian bone metastasis survey. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e83026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Deng, T.; Lyon, C.J.; Bergin, S.; Caligiuri, M.A.; Hsueh, W.A. Obesity, Inflammation, and Cancer. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2016, 11, 421–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sulston, R.J.; Cawthorn, W.P. Bone marrow adipose tissue as an endocrine organ: Close to the bone? Horm. Mol. Biol. Clin. Investig. 2016, 28, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cawthorn, W.P.; Scheller, E.L.; Parlee, S.D.; Pham, H.A.; Learman, B.S.; Redshaw, C.M.; Sulston, R.J.; Burr, A.A.; Das, A.K.; Simon, B.R.; et al. Expansion of Bone Marrow Adipose Tissue During Caloric Restriction Is Associated With Increased Circulating Glucocorticoids and Not With Hypoleptinemia. Endocrinology 2016, 157, 508–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Blebea, J.S.; Houseni, M.; Torigian, D.A.; Fan, C.; Mavi, A.; Zhuge, Y.; Iwanaga, T.; Mishra, S.; Udupa, J.; Zhuang, J.; et al. Structural and functional imaging of normal bone marrow and evaluation of its age-related changes. Semin. Nucl. Med. 2007, 370, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazeli, P.K.; Horowitz, M.C.; MacDougald, O.A.; Scheller, E.L.; Rodeheffer, M.S.; Rosen, C.J.; Klibanski, A. Marrow Fat and Bone—New Perspectives. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 98, 935–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scheller, E.L.; Doucette, C.R.; Learman, B.S.; Cawthorn, W.P.; Khandaker, S.; Schell, B.; Wu, B.; Ding, S.Y.; Bredella, M.A.; Fazeli, P.K.; et al. Region-specific variation in the properties of skeletal adipocytes reveals regulated and constitutive marrow adipose tissues. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martin, P.J.; Haren, N.; Ghali, O.; Clabaut, A.; Chauveau, C.; Hardouin, P.; Broux, O. Adipogenic RNAs are transferred in osteoblasts via bone marrow adipocytes-derived extracellular vesicles (EVs). BMC Cell Biol. 2015, 16, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Naveiras, O.; Nardi, V.; Wenzel, P.L.; Hauschka, P.V.; Fahey, F.; Daley, G.Q. Bone-marrow adipocytes as negative regulators of the haematopoietic microenvironment. Nature 2009, 460, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nieman, K.M.; Romero, I.L.; Van Houten, B.; Lengyel, E. Adipose tissue and adipocytes support tumorigenesis and metastasis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1831, 1533–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xiong, Y.; McDonald, L.T.; Russell, D.L.; Kelly, R.R.; Wilson, K.R.; Mehrotra, M.; Soloff, A.C.; LaRue, A.C. Hematopoietic stem cell-derived adipocytes and fibroblasts in the tumor microenvironment. World J. Stem Cells 2015, 7, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Luo, G.; He, Y.; Yu, X. Bone Marrow Adipocyte: An Intimate Partner with Tumor Cells in Bone Metastasis. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herroon, M.K.; Rajagurubandara, E.; Diedrich, J.D.; Heath, E.I.; Podgorski, I. Adipocyte-activated oxidative and ER stress pathways promote tumor survival in bone via upregulation of Heme Oxygenase 1 and Survivin. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Diedrich, J.D.; Rajagurubandara, E.; Herroon, M.K.; Mahapatra, G.; Hüttemann, M.; Podgorski, I. Bone marrow adipocytes promote the Warburg phenotype in metastatic prostate tumors via HIF-1α activation. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 64854–64877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morris, E.V.; Edwards, C.M. Adipokines, adiposity, and bone marrow adipocytes: Dangerous accomplices in multiple myeloma. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018, 233, 9159–9166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, E.V.; Edwards, C.M. Bone marrow adiposity and multiple myeloma. Bone 2019, 118, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilg, H.; Moschen, A.R. Adipocytokines: Mediators linking adipose tissue, inflammation and immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2006, 6, 772–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irish, J.M.; Kotecha, N.; Nolan, G.P. Mapping normal and cancer cell signalling networks: Towards single-cell proteomics. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2006, 6, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilkes, D.M.; Bajpai, S.; Chaturvedi, P.; Wirtz, D.; Semenza, G.L. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) promotes extracellular matrix remodelling under hypoxic conditions by inducing P4HA1, P4HA2, and PLOD2 expression in fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 10819–10829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Song, Y.; Zheng, S.; Wang, J.; Long, H.; Fang, L.; Wang, G.; Li, Z.; Que, T.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; et al. Hypoxia-induced PLOD2 promotes proliferation, migration and invasion via PI3K/Akt signaling in glioma. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 41947–41962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Eisinger-Mathason, T.S.; Zhang, M.; Qiu, Q.; Skuli, N.; Nakazawa, M.S.; Karakasheva, T.; Mucaj, V.; Shay, J.E.; Stangenberg, L.; Sadri, N.; et al. Hypoxia-dependent modification of collagen networks promotes sarcoma metastasis. Cancer Discov. 2013, 3, 1190–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gilkes, D.M.; Bajpai, S.; Wong, C.C.; Chaturvedi, P.; Hubbi, M.E.; Wirtz, D.; Semenza, G.L. Procollagen lysyl hydroxylase 2 is essential for hypoxia-induced breast cancer metastasis. Mol. Cancer Res. 2013, 11, 456–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, Y.; Terajima, M.; Yang, Y.; Sun, L.; Ahn, Y.H.; Pankova, D.; Puperi, D.S.; Watanabe, T.; Kim, M.P.; Blackmon, S.H.; et al. Lysyl hydroxylase 2 induces a collagen cross-link switch in tumor stroma. J. Clin. Investig. 2015, 125, 1147–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, F.; Zhang, J.; Hu, G.; Liu, L.; Liang, W. Hypoxia and TGF-beta1 induced PLOD2 expression improve the migration and invasion of cervical cancer cells by promoting epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and focal adhesion formation. Cancer Cell Int. 2017, 17, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, A.H.; Combs, T.P.; Scherer, P.E. ACRP30/adiponectin: An adipokine regulating glucose and lipid metabolism. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2002, 13, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadowaki, T.; Yamauchi, T. Adiponectin and adiponectin receptors. Endocr. Rev. 2005, 26, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beltowski, J. Adiponectin and resistin—New hormones of white adipose tissue. Med. Sci. Monit. 2003, 9, RA55–RA61. [Google Scholar]

- Cawthorn, W.P.; Scheller, E.L.; Learman, B.S.; Parlee, S.D.; Simon, B.R.; Mori, H.; Ning, X.; Bree, A.J.; Schell, B.; Broome, D.T.; et al. Bone marrow adipose tissue is an endocrine organ that contributes to increased circulating adiponectin during caloric restriction. Cell Metab. 2014, 20, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Arita, Y.; Kihara, S.; Ouchi, N.; Takahashi, M.; Maeda, K.; Miyagawa, J.; Hotta, K.; Shimomura, I.; Nakamura, T.; Miyaoka, K.; et al. Paradoxical decrease of an adipose-specific protein, adiponectin, in obesity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999, 257, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delporte, M.L.; Brichard, S.M.; Hermans, M.P.; Beguin, C.; Lambert, M. Hyperadiponectinaemia in anorexia nervosa. Clin. Endocrinol. 2003, 58, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Combs, T.P.; Berg, A.H.; Rajala, M.W.; Klebanov, S.; Iyengar, P.; Jimenez-Chillaron, J.C.; Patti, M.E.; Klein, S.L.; Weinstein, R.S.; Scherer, P.E. Sexual differentiation, pregnancy, calorie restriction, and aging affect the adipocyte-specific secretory protein adiponectin. Diabetes 2003, 52, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, X.; Chen, T.; Wu, Y.; Tang, Z. Role and mechanism of PTEN in adiponectin-induced osteogenesis in human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 483, 712–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Wu, Y.W.; Lu, H.; Guo, Y.; Tang, Z.H. Adiponectin enhances osteogenic differentiation in human adipose-derived stem cells by activating the APPL1-AMPK signalling pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 461, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.H.; Lee, Y.Y.; Yu, B.Y.; Yang, B.S.; Cho, K.H.; Yoon, D.K.; Roh, Y.K. Adiponectin induces growth arrest and apoptosis of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2005, 28, 1263–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieudonne, M.N.; Bussiere, M.; Dos Santos, E.; Leneveu, M.C.; Giudicelli, Y.; Pecquery, R. Adiponectin mediates antiproliferative and apoptotic responses in human MCF7 breast cancer cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006, 345, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, N.K.; Fu, P.P.; Nagalingam, A.; Wang, J.; Handy, J.; Cohen, C.; Tighiouart, M.; Sharma, D.; Anania, F.A. Adiponectin modulates C-jun N-terminal kinase and mammalian target of rapamycin and inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2010, 139, 1762–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ishikawa, M.; Kitayama, J.; Yamauchi, T.; Kadowaki, T.; Maki, T.; Miyato, H.; Yamashita, H.; Nagawa, H. Adiponectin inhibits the growth and peritoneal metastasis of gastric cancer through its specific membrane receptors AdipoR1 and AdipoR2. Cancer Sci. 2007, 98, 1120–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, L.; Gasser, J.; Zhao, J.; Yang, B.; Li, F.; Zhao, A.Z. Human adiponectin inhibits cell growth and induces apoptosis in human endometrial carcinoma cells, HEC-1-A and RL95 2. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2007, 14, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossmann, M.E.; Nkhata, K.J.; Mizuno, N.K.; Ray, A.; Cleary, M.P. Effects of adiponectin on breast cancer cell growth and signaling. Br. J. Cancer 2008, 98, 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Di Zazzo, E.; Polito, R.; Bartollino, S.; Nigro, E.; Porcile, C.; Bianco, A.; Daniele, A.; Moncharmont, B. Adiponectin as Link Factor between Adipose Tissue and Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, E839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Y.; Lam, J.B.; Lam, K.S.; Liu, J.; Lam, M.C.; Hoo, R.L.; Wu, D.; Cooper, G.J.; Xu, A. Adiponectin modulates the glycogen synthase kinase-3β/β-catenin signaling pathway and attenuates mammary tumorigenesis of MDA-MB-231 cells in nude mice. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 11462–11470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dos Santos, E.; Benaitreau, D.; Dieudonne, M.N.; Leneveu, M.C.; Serazin, V.; Giudicelli, Y.; Pecquery, R. Adiponectin mediates an antiproliferative response in human MDA-MB 231 breast cancer cells. Oncol. Rep. 2008, 20, 971–977. [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama, S.; Miyoshi, Y.; Ishihara, H.; Noguchi, S. Growth-inhibitory effect of adiponectin via adiponectin receptor 1 on human breast cancer cells through inhibition of s-phase entry without inducing apoptosis. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2008, 112, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauro, L.; Pellegrino, M.; De Amicis, F.; Ricchio, E.; Giordano, F.; Rizza, P.; Catalano, S.; Bonofiglio, D.; Sisci, D.; Panno, M.L.; et al. Evidences that estrogen receptor α interferes with adiponectin effects on breast cancer cell growth. Cell Cycle 2014, 13, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mauro, L.; Pellegrino, M.; Giordano, F.; Ricchio, E.; Rizza, P.; De Amicis, F.; Catalano, S.; Bonofiglio, D.; Panno, M.L.; Andò, S. Estrogen receptor-α drives adiponectin effects on cyclin D1 expression in breast cancer cells. FASEB J. 2015, 29, 2150–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Panno, M.L.; Naimo, G.D.; Spina, E.; Andò, S.; Mauro, L. Different molecular signaling sustaining adiponectin action in breast cancer. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2016, 31, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, N.K.; Sharma, D. Metastasis suppression by adiponectin: LKB1 rises up to the challenge. Cell Adhes. Migr. 2010, 4, 358–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Libby, E.F.; Frost, A.R.; Demark-Wahnefried, W.; Hurst, D.R. Linking adiponectin and autophagy in the regulation of breast cancer metastasis. J. Mol. Med. 2014, 92, 1015–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lin, R.; Wang, S.; Zhao, R.C. Exosomes from human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells promote migration through Wnt signaling pathway in a breast cancer cell model. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2013, 383, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gernapudi, R.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wolfson, B.; Roy, S.; Duru, N.; Eades, G.; Yang, P.; Zhou, Q. Targeting exosomes from preadipocytes inhibits preadipocyte to cancer stem cell signaling in early-stage breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2015, 150, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ducy, P.; Amling, M.; Takeda, S.; Priemel, M.; Schilling, A.F.; Beil, F.T.; Shen, J.; Vinson, C.; Rueger, J.M.; Karsenty, G. Leptin inhibits bone formation through a hypothalamic relay: A central control of bone mass. Cell 2000, 100, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Turner, R.T.; Kalra, S.P.; Wong, C.P.; Philbrick, K.A.; Lindenmaier, L.B.; Boghossian, S.; Iwaniec, U.T. Peripheral leptin regulates bone formation. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2013, 28, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhou, B.O.; Yu, H.; Yue, R.; Zhao, Z.; Rios, J.J.; Naveiras, O.; Morrison, S.J. Bone marrow adipocytes promote the regeneration of stem cells and haematopoiesis by secreting SCF. Nat. Cell Biol. 2017, 19, 891–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, B.O.; Yue, R.; Murphy, M.M.; Peyer, J.G.; Morrison, S.J. Leptin-receptor-expressing mesenchymal stromal cells represent the main source of bone formed by adult bone marrow. Cell Stem Cell 2014, 15, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reseland, J.E.; Syversen, U.; Bakke, I.; Qvigstad, G.; Eide, L.G.; Hjertner, O.; Gordeladze, J.O.; Drevon, C.A. Leptin is expressed in and secreted from primary cultures of human osteoblasts and promotes bone mineralization. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2001, 16, 1426–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köllmer, M.; Buhrman, J.S.; Zhang, Y.; Gemeinhart, R.A. Markers Are Shared Between Adipogenic and Osteogenic Differentiated Mesenchymal Stem Cells. J. Dev. Biol. Tissue Eng. 2013, 5, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldefie-Chézet, F.; Damez, M.; de Latour, M.; Konska, G.; Mishellani, F.; Fusillier, C.; Guerry, M.; Penault-Llorca, F.; Guillot, J.; Vasson, M.P. Leptin: A proliferative factor for breast cancer? Study on human ductal carcinoma. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 334, 737–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assiri, A.M.; Kamel, H.F. Evaluation of diagnostic and predictive value of serum adipokines: Leptin, resistin and visfatin in postmenopausal breast cancer. Obes Res. Clin. Pract. 2016, 10, 442–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliustaoglu, M.; Bilici, A.; Gumus, M.; Colak, A.T.; Baloglu, G.; Irmak, R.; Seker, M.; Ustaalioglu, B.B.; Salman, T.; Sonmez, B.; et al. Preoperative serum leptin levels in patients with breast cancer. Med. Oncol. 2010, 27, 388–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, L.; Wang, C.D.; Cao, C.; Cai, L.R.; Li, D.H.; Zheng, Y.Z. Association of serum leptin with breast cancer: A meta-analysis. Medicine 2019, 98, e14094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishikawa, M.; Kitayama, J.; Nagawa, H. Enhanced expression of leptin and leptin receptor (OB-R) in human breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004, 10, 4325–4331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Guo, S.; Gonzalez-Perez, R.R. Notch, IL-1 and leptin crosstalk outcome (NILCO) is critical for leptin-induced proliferation, migration and VEGF/VEGFR-2 expression in breast cancer. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e21467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhou, J.; Wulfkuhle, J.; Zhang, H.; Gu, P.; Yang, Y.; Deng, J.; Margolick, J.B.; Liotta, L.A.; Petricoin, E., 3rd; Zhang, Y. Activation of the PTEN/mTOR/STAT3 pathway in breast cancer stem-like cells is required for viability and maintenance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 16158–16163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pratt, M.A.; Tibbo, E.; Robertson, S.J.; Jansson, D.; Hurst, K.; Perez-Iratxeta, C.; Lau, R.; Niu, M.Y. The canonical NF-kappaB pathway is required for formation of luminal mammary neoplasias and is activated in the mammary progenitor population. Oncogene 2009, 28, 2710–2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Knight, B.B.; Oprea-Ilies, G.M.; Nagalingam, A.; Yang, L.; Cohen, C.; Saxena, N.K.; Sharma, D. Survivin upregulation, dependent on leptin-EGFR-Notch1 axis, is essential for leptin-induced migration of breast carcinoma cells. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2011, 18, 413–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guo, S.; Liu, M.; Wang, G.; Torroella-Kouri, M.; Gonzalez-Perez, R.R. Oncogenic role and therapeutic target of leptin signaling in breast cancer and cancer stem cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1825, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lipsey, C.C.; Harbuzariu, A.; Daley-Brown, D.; Gonzalez-Perez, R.R. Oncogenic role of leptin and Notch interleukin-1 leptin crosstalk outcome in cancer. World J. Methodol. 2016, 6, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giordano, C.; Gelsomino, L.; Barone, I.; Panza, S.; Augimeri, G.; Bonofiglio, D.; Rovito, D.; Naimo, G.D.; Leggio, A.; Catalano, S.; et al. Leptin Modulates Exosome Biogenesis in Breast Cancer Cells: An Additional Mechanism in Cell-to-Cell Communication. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, E1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bowers, L.W.; Rossi, E.L.; McDonell, S.B.; Doerstling, S.S.; Khatib, S.A.; Lineberger, C.G.; Albright, J.E.; Tang, X.; deGraffenried, L.A.; Hursting, S.D. Leptin Signaling Mediates Obesity-Associated CSC Enrichment and EMT in Preclinical TNBC Models. Mol. Cancer Res. 2018, 16, 869–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Juárez-Cruz, J.C.; Zuñiga-Eulogio, M.D.; Olea-Flores, M.; Castañeda-Saucedo, E.; Mendoza-Catalán, M.A.; Ortuño-Pineda, C.; Moreno-Godinez, M.E.; Villegas-Comonfort, S.; Padilla-Benavides, T.; Navarro-Tito, N. Leptin induces cell migration and invasion in a FAK-Src- dependent manner in breast cancer cells. Endocr. Connect. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Li, K.; Wei, L.; Huang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Su, M.; Pang, X.; Wang, N.; Ji, F.; Zhong, C.; Chen, T. Leptin promotes breast cancer cell migration and invasion via IL-18 expression and secretion. Int. J. Oncol. 2016, 48, 2479–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ojalvo, L.S.; King, W.; Cox, D.; Pollard, J.W. High-density gene expression analysis of tumor-associated macrophages from mouse mammary tumors. Am. J. Pathol. 2009, 174, 1048–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cao, H.; Huang, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, H.; Pang, X.; Li, K.; Dang, W.; Tang, H.; Wei, L.; Su, M.; et al. Leptin promotes migration and invasion of breast cancer cells by stimulating IL-8 production in M2 macrophages. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 65441–65453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- He, J.Y.; Wei, X.H.; Li, S.J.; Liu, Y.; Hu, H.L.; Li, Z.Z.; Kuang, X.H.; Wang, L.; Shi, X.; Yuan, S.T.; et al. Adipocyte-derived IL-6 and leptin promote breast cancer metastasis via upregulation of Lysyl Hydroxylase-2 expression. Cell Commun. Signal. 2018, 16, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Du, H.; Pang, M.; Hou, X.; Yuan, S.; Sun, L. PLOD2 in cancer research. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 90, 670–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, A.; Saeidi, J.; Azimi-Nejad, M.; Hashemy, S.I. Leptin-induced signaling pathways in cancer cell migration and invasion. Cell Oncol. 2019, 42, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph-Silverstein, J.; Silverstein, R.L. Cell adhesion molecules: An overview. Cancer Investig. 1998, 16, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.F.; Chen, J.H.; Wu, C.T.; Chang, P.C.; Wang, S.L.; Yeh, W.L. Induction of osteoclast-like cell formation by leptin-induced soluble intercellular adhesion molecule secreted from cancer cells. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2019, 14, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, S.J.; Shalloway, D. An RNA-binding protein associated with Src through its SH2 and SH3 domains in mitosis. Nature 1994, 368, 867–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisone, P.; Pradella, D.; Di Matteo, A.; Belloni, E.; Ghigna, C.; Paronetto, M.P. SAM68: Signal Transduction and RNA Metabolism in Human Cancer. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 528954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Maroni, P.; Citterio, L.; Piccoletti, R.; Bendinelli, P. Sam68 and ERKs regulate leptin-induced expression of OB-Rb mRNA in C2C12 myotubes. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2009, 309, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, K.; Li, L.; Nisson, P.E.; Gruber, C.; Jessee, J.; Cohen, S.N. Neoplastic transformation and tumorigenesis associated with sam68 protein deficiency in cultured murine fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 40195–40201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taylor, S.J.; Resnick, R.J.; Shalloway, D. Sam68 exerts separable effects on cell cycle progression and apoptosis. BMC Cell Biol. 2004, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Richard, S.; Torabi, N.; Franco, G.V.; Tremblay, G.A.; Chen, T.; Vogel, G.; Morel, M.; Cléroux, P.; Forget-Richard, A.; Komarova, S.; et al. Ablation of the Sam68 RNA binding protein protects mice from age-related bone loss. PLoS Genet 2005, 1, e74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, S.; Vogel, G.; Huot, M.E.; Guo, T.; Muller, W.J.; Lukong, K.E. Sam68 haploinsufficiency delays onset of mammary tumorigenesis and metastasis. Oncogene 2008, 27, 548–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derry, J.J.; Richard, S.; Valderrama Carvajal, H.; Ye, X.; Vasioukhin, V.; Cochrane, A.W.; Chen, T.; Tyner, A.L. Sik (BRK) phosphorylates Sam68 in the nucleus and negatively regulates its RNA binding ability. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000, 20, 6114–6126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paronetto, M.P.; Venables, J.P.; Elliott, D.J.; Geremia, R.; Rossi, P.; Sette, C. Tr-kit promotes the formation of a multimolecular complex composed by Fyn, PLCgamma1 and Sam68. Oncogene 2003, 22, 8707–8715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andreotti, A.H.; Bunnell, S.C.; Feng, S.; Berg, L.J.; Schreiber, S.L. Regulatory intramolecular association in a tyrosine kinase of the Tec family. Nature 1997, 385, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Boisvert, F.M.; Bazett-Jones, D.P.; Richard, S. A role for the GSG domain in localizing Sam68 to novel nuclear structures in cancer cell lines. Mol. Biol. Cell 1999, 10, 3015–3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; Zheng, H.; Yu, C.; Chen, J.; Liu, Z.; Li, M.; Zeng, M.; Zhou, F.; Song, L. Expression and cytoplasmic localization of SAM68 is a significant and independent prognostic marker for renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol. Prev. Biomark. 2009, 18, 2685–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Li, Z.; Yu, C.P.; Zhong, Y.; Liu, T.J.; Huang, Q.D.; Zhao, X.H.; Huang, H.; Tu, H.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Sam68 expression and cytoplasmic localization is correlated with lymph node metastasis as well as prognosis in patients with early-stage cervical cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2012, 23, 638–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Xiong, H.; Wu, J.; Li, J.; Li, M. Sam68 up-regulation correlates with, and its down-regulation inhibits, proliferation and tumourigenicity of breast cancer cells. J. Pathol. 2010, 222, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Li, Z.; He, B.; Liu, J.; Li, S.; Zhou, L.; Pan, C.; Yu, Z.; Xu, Z. Sam68 is a novel marker for aggressive neuroblastoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2013, 6, 1751–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bielli, P.; Busà, R.; Paronetto, M.P.; Sette, C. The RNA-binding protein Sam68 is a multifunctional player in human cancer. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2011, 18, R91–R102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Busà, R.; Paronetto, M.P.; Farini, D.; Pierantozzi, E.; Botti, F.; Angelini, D.F.; Attisani, F.; Vespasiani, G.; Sette, C. The RNA-binding protein Sam68 contributes to proliferation and survival of human prostate cancer cells. Oncogene 2007, 26, 4372–4382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lukong, K.E.; Richard, S. Sam68, the KH domain-containing superSTAR. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2003, 1653, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babic, I.; Jakymiw, A.; Fujita, D.J. The RNA binding protein Sam68 is acetylated in tumor cell lines, and its acetylation correlates with enhanced RNA binding activity. Oncogene 2004, 23, 3781–3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Côté, J.; Boisvert, F.M.; Boulanger, M.C.; Bedford, M.T.; Richard, S. Sam68 RNA binding protein is an in vivo substrate for protein arginine N-methyltransferase 1. Mol. Biol. Cell 2003, 14, 274–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Babic, I.; Cherry, E.; Fujita, D.J. SUMO modification of Sam68 enhances its ability to repress cyclin D1 expression and inhibits its ability to induce apoptosis. Oncogene 2006, 25, 4955–4964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sette, C. Post-translational regulation of star proteins and effects on their biological functions. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2010, 693, 54–66. [Google Scholar]

- Lukong, K.E.; Larocque, D.; Tyner, A.L.; Richard, S. Tyrosine phosphorylation of sam68 by breast tumor kinase regulates intranuclear localization and cell cycle progression. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 38639–38647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Paronetto, M.P.; Achsel, T.; Massiello, A.; Chalfant, C.E.; Sette, C. The RNA-binding protein Sam68 modulates the alternative splicing of Bcl-x. J. Cell Biol. 2007, 176, 929–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Paronetto, M.P.; Farini, D.; Sammarco, I.; Maturo, G.; Vespasiani, G.; Geremia, R.; Rossi, P.; Sette, C. Expression of a truncated form of the c-Kit tyrosine kinase receptor and activation of Src kinase in human prostatic cancer. Am. J. Pathol. 2004, 164, 1243–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valacca, C.; Bonomi, S.; Buratti, E.; Pedrotti, S.; Baralle, F.E.; Sette, C.; Ghigna, C.; Biamonti, G. Sam68 regulates EMT through alternative splicing-activated nonsense-mediated mRNA decay of the SF2/ASF proto-oncogene. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 191, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Pérez, A.; Sánchez-Jiménez, F.; Vilariño-García, T.; de la Cruz, L.; Virizuela, J.A.; Sánchez-Margalet, V. Sam68 Mediates the Activation of Insulin and Leptin Signalling in Breast Cancer Cells. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0158218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biamonti, G.; Bonomi, S.; Gallo, S.; Ghigna, C. Making alternative splicing decisions during epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT). Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2012, 69, 2515–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa, P.J.; Menezes, J.; Romao, L. The role of alternative splicing coupled to nonsense-mediated mRNA decay in human disease. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2017, 91, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalves, V.; Pereira, J.F.S.; Jordan, P. Signaling Pathways Driving Aberrant Splicing in Cancer Cells. Genes 2017, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Amin, E.M.; Oltean, S.; Hua, J.; Gammons, M.V.; Hamdollah-Zadeh, M.; Welsh, G.I.; Cheung, M.K.; Ni, L.; Kase, S.; Rennel, E.S.; et al. WT1 mutants reveal SRPK1 to be a downstream angiogenesis target by altering VEGF splicing. Cancer Cell 2011, 20, 768–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pelisch, F.; Khauv, D.; Risso, G.; Stallings-Mann, M.; Blaustein, M.; Quadrana, L.; Radisky, D.C.; Srebrow, A. Involvement of hnRNP A1 in the matrix metalloprotease-3-dependent regulation of Rac1 pre-mRNA splicing. J. Cell Biochem. 2012, 113, 2319–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gokmen-Polar, Y.; Murray, N.R.; Velasco, M.A.; Gatalica, Z.; Fields, A.P. Elevated protein kinase C betaII is an early promotive event in colon carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 1375–1381. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Montiel, N.; Rosas-Murrieta, N.; Martínez-Contreras, R. Alternative splicing regulation: Implications in cancer diagnosis and treatment. Med. Clin. 2015, 144, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebestyén, E.; Zawisza, M.; Eyras, E. Detection of recurrent alternative splicing switches in tumor samples reveals novel signatures of cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, 1345–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- David, C.J.; Manley, J.L. Alternative pre-mRNA splicing regulation in cancer: Pathways and programs unhinged. Genes Dev. 2010, 24, 2343–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Matter, N.; Herrlich, P.; König, H. Signal-dependent regulation of splicing via phosphorylation of Sam68. Nature 2002, 420, 691–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Sharp, P.A. Regulation of CD44 alternative splicing by SRm160 and its potential role in tumor cell invasion. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006, 26, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ghigna, C.; Giordano, S.; Shen, H.; Benvenuto, F.; Castiglioni, F.; Comoglio, P.M.; Green, M.R.; Riva, S.; Biamonti, G. Cell motility is controlled by SF2/ASF through alternative splicing of the Ron protooncogene. Mol. Cell 2005, 20, 881–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, S.; Hu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Maihle, N.J.; Grande, J.P.; Cleary, M.P. Effects of high-fat diet and/or body weight on mammary tumor leptin and apoptosis signaling pathways in MMTV-TGF-alpha mice. Breast Cancer Res. 2007, 9, R91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahmed, S.D.H.; Idrees, F.; Ahsan, M.; Khanam, A.; Sultan, N.; Akhter, N. Association of serum leptin with serum estradiol in relation to breast carcinogenesis: A comparative case-control study between pre- and postmenopausal women. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 48, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Lam, J.B.; Chow, K.H.; Xu, A.; Lam, K.S.; Moon, R.T.; Wang, Y. Adiponectin stimulates Wnt inhibitory factor-1 expression through epigenetic regulations involving the transcription factor specificity protein 1. Carcinogenesis 2008, 29, 2195–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lam, J.B.; Chow, K.H.; Xu, A.; Lam, K.S.; Liu, J.; Wong, N.S.; Moon, R.T.; Shepherd, P.R.; Cooper, G.J.; Wang, Y. Adiponectin haploinsufficiency promotes mammary tumor development in MMTV-PyVT mice by modulation of phosphatase and tensin homolog activities. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e4968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukong, K.E.; Richard, S. Targeting the RNA-binding protein Sam68 as a treatment for cancer? Future Oncol. 2007, 3, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chang, Y.C.; Liu, C.L.; Chang, K.J.; Guo, I.C. Leptin-induced growth of human ZR-75-1 breast cancer cells is associated with up-regulation of cyclin D1 and c-Myc and down-regulation of tumor suppressor p53 and p21WAF1/CIP1. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2006, 98, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, C.N.; Spalding, H.S.; Mohammed, S.I.; Camarillo, I.G. Identification of proteins secreted from leptin stimulated MCF-7 breast cancer cells: A dual proteomic approach. Exp. Biol. Med. 2008, 233, 708–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumura, M.; Yamamoto, M.; Sakuma, H.; Kojima, T.; Maruyama, T.; Jamali, M.; Cooper, D.R.; Yasuda, K. Leptin and high glucose stimulate cell proliferation in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells: Reciprocal involvement of PKC-alpha and PPAR expression. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2002, 1592, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dalamaga, M.; Diakopoulos, K.N.; Mantzoros, C.S. The role of adiponectin in cancer: A review of current evidence. Endocr. Rev. 2012, 33, 547–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jia, Z.; Liu, Y.; Cui, S. Adiponectin induces breast cancer cell migration and growth factor expression. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2014, 70, 1239–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Jin, Q.; Su, M.; Ji, F.; Wang, N.; Zhong, C.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, J.; et al. Leptin promotes the migration and invasion of breast cancer cells by upregulating ACAT2. Cell. Oncol. 2017, 40, 537–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taliaferro-Smith, L.; Nagalingam, A.; Zhong, D.; Zhou, W.; Saxena, N.K.; Sharma, D. LKB1 is required for adiponectin-mediated modulation of AMPK-S6K axis and inhibition of migration and invasion of breast cancer cells. Oncogene 2009, 28, 2621–2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Libby, F.E.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.I.; Lewis, M.J.; Demark-Wahnefried, W.; Hurst, D.R. Globular adiponectin enhances invasion in human breast cancer cells. Oncol. Lett. 2016, 11, 633–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Locatelli, A.; Lange, C.A. Met receptors induce Sam68-dependent cell migration by activation of alternate extracellular signal-regulated kinase family members. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 21062–21072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mishra, A.K.; Parish, C.R.; Wong, M.L.; Licinio, J.; Blackburn, A.C. Leptin signals via TGFB1 to promote metastatic potential and stemness in breast cancer. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0178454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gonzalez-Perez, R.R.; Xu, Y.; Guo, S.; Watters, A.; Zhou, W.; Leibovich, S.J. Leptin upregulates VEGF in breast cancer via canonic and non-canonical signalling pathways and NFkappaB/HIF-1alpha activation. Cell. Signal. 2010, 22, 1350–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guo, S.; Liu, M.; Gonzalez-Perez, R.R. Role of Notch and its oncogenic signaling crosstalk in breast cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2011, 1815, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Delort, L.; Jardé, T.; Dubois, V.; Vasson, M.P.; Caldefie-Chézet, F. New insights into anticarcinogenic properties of adiponectin: A potential therapeutic approach in breast cancer? Vitam. Horm. 2012, 90, 397–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzel, M.S.; Hebbard, L.W.; Shostak, G.; Shapiro, L.; Cardiff, R.D.; Ranscht, B. Adiponectin deficiency limits tumor vascularization in the MMTV-PyV-mT mouse model of mammary cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 3256–3264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Landskroner-Eiger, S.; Qian, B.; Muise, E.S.; Nawrocki, A.R.; Berger, J.P.; Fine, E.J.; Koba, W.; Deng, Y.; Pollard, J.W.; Scherer, P.E. Proangiogenic contribution of adiponectin toward mammary tumor growth in vivo. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 3265–3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jiang, H.; Yu, J.; Guo, H.; Song, H.; Chen, S. Upregulation of survivin by leptin/STAT3 signaling in MCF-7 cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 368, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Cheng, J.; Chen, L.; Xu, H.; Li, Q.; Pang, T. Sam68 affects cell proliferation and apoptosis of human adult T-acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells via AKT/mTOR signal pathway. Leuk. Res. 2016, 46, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esper, R.M.; Dame, M.; McClintock, S.; Holt, P.R.; Dannenberg, A.J.; Wicha, M.S.; Brenner, D.E. Leptin and Adiponectin Modulate the Self-renewal of Normal Human Breast Epithelial Stem Cells. Cancer Prev. Res. 2015, 8, 1174–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benoit, Y.D.; Mitchell, R.R.; Risueño, R.M.; Orlando, L.; Tanasijevic, B.; Boyd, A.L.; Aslostovar, L.; Salci, K.R.; Shapovalova, Z.; Russell, J.; et al. Sam68 Allows Selective Targeting of Human Cancer Stem Cells. Cell Chem. Biol. 2017, 24, 833–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhao, Z.; Song, Z.; Liao, Z.; Liu, Z.; Sun, H.; Lei, B.; Chen, W.; Dang, C. PKM2 promotes stemness of breast cancer cell by through Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Tumor Biol. 2016, 37, 4223–4234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olea-Flores, M.; Juárez-Cruz, J.C.; Mendoza-Catalán, M.A.; Padilla-Benavides, T.; Navarro-Tito, N. Signaling Pathways Induced by Leptin during Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Breast Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, E3493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, L.; Tang, C.; Cao, H.; Li, K.; Pang, X.; Zhong, L.; Dang, W.; Tang, H.; Huang, Y.; Wei, L.; et al. Activation of IL-8 via PI3K/Akt-dependent pathway is involved in leptin-mediated epithelial-mesenchymal transition in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2015, 16, 1220–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wei, L.; Li, K.; Pang, X.; Guo, B.; Su, M.; Huang, Y.; Wang, N.; Ji, F.; Zhong, C.; Yang, J.; et al. Leptin promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition of breast cancer via the upregulation of pyruvate kinase M2. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 35, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cui, E.; Guo, H.; Shen, M.; Yu, H.; Gu, D.; Mao, W.; Wang, X. Adiponectin inhibits migration and invasion by reversing epithelial-mesenchymal transition in non-small cell lung carcinoma. Oncol. Rep. 2018, 40, 1330–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.; Wang, L.; Ma, Q.; Qi, M.; Lu, N.; Zhang, L.; Han, B. Adiponectin as a potential tumor suppressor inhibiting epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition but frequently silenced in prostate cancer by promoter methylation. Prostate 2015, 75, 1197–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Breast Cancer Progress | Leptin | Adiponectin | Sam68 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tumourigenesis | + [60,121,122] | − [123,124,125] | + [94,125] |

| Tumour progression | + [126,127,128] | − [42,50,129] or + [51,130] | + [96,125] |

| Cancer cell invasion | + [131,132] | − [50,74] or + [130,133] | + [134] |

| Metastasis | + [72,135] | − [50] or + [51] | + [134] |

| Angiogenesis | + [65,136,137] | − [138] or + [139,140] | ? |

| Tumour cell apoptosis | − [127,141] | − [38] or + [138] | + [112,142] |

| Cancer stem cells (CSC) | + [69,72,135] | − [143] | + [144] |

| EMT | + [145,146,147,148] | ? (in breast cancer) − (in lung and prostate carcinoma [149,150]) | +/− [107,151] |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maroni, P. Leptin, Adiponectin, and Sam68 in Bone Metastasis from Breast Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1051. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21031051

Maroni P. Leptin, Adiponectin, and Sam68 in Bone Metastasis from Breast Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020; 21(3):1051. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21031051

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaroni, Paola. 2020. "Leptin, Adiponectin, and Sam68 in Bone Metastasis from Breast Cancer" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21, no. 3: 1051. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21031051