The Role of Sclerostin in Bone and Ectopic Calcification

Abstract

1. Discovery of Sclerostin

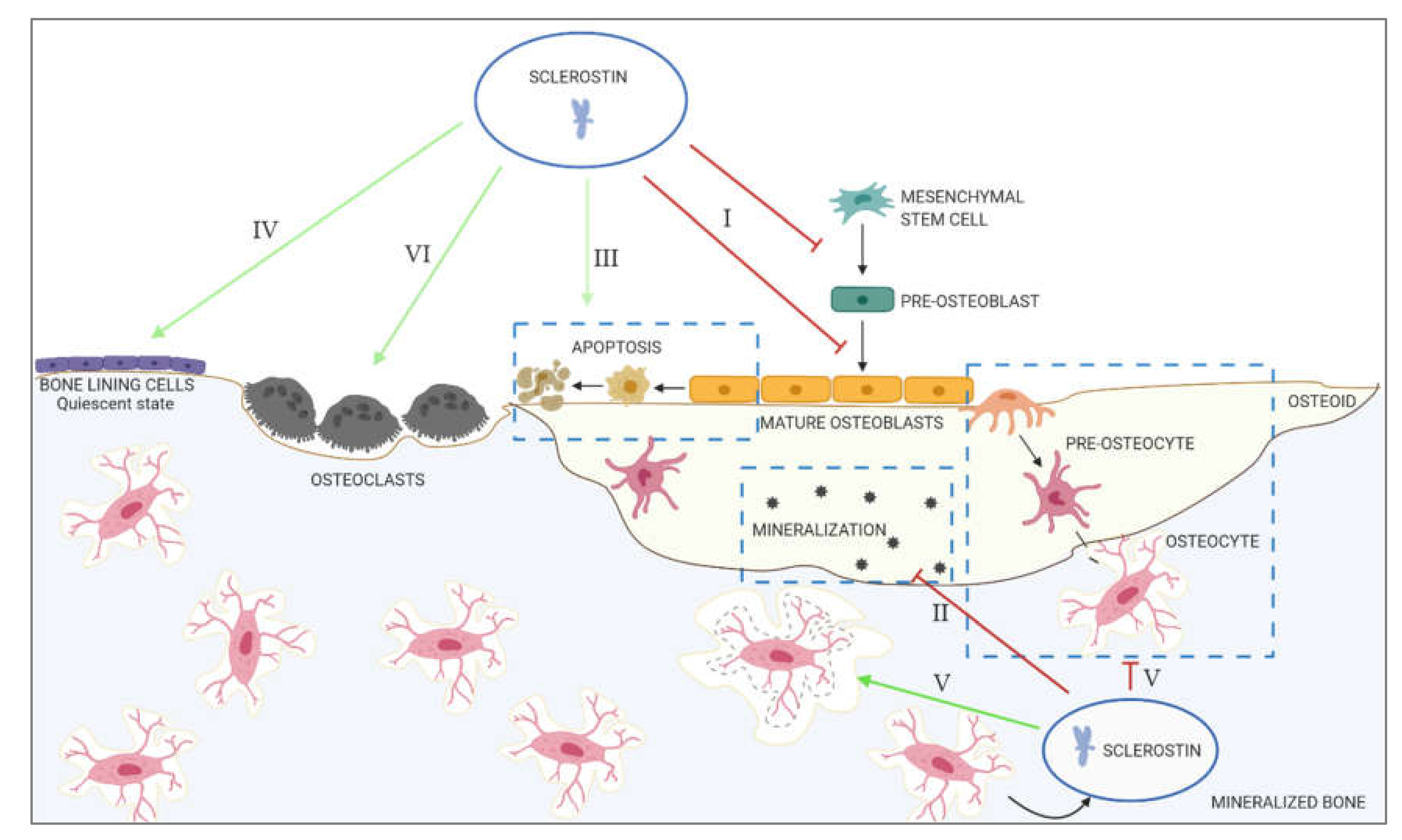

2. The Role of Sclerostin in Physiological Calcification

- I.

- Inhibition of proliferation and differentiation of osteoprogenitor/pre-osteoblastic cells, as well as decreased activation of mature osteoblasts

- II.

- Decreased mineralization

- III.

- Increased apoptosis of the osteogenic cells

- IV.

- Maintenance of bone lining cells in the quiescent state

- V.

- Regulation of osteocyte maturation and osteocytic osteolysis

- VI.

- Stimulation of bone resorption

3. The Role of Sclerostin in Ectopic Calcification

3.1. Vascular Calcification

3.2. Aortic Valve Calcification

3.3. Genetic Disorders Characterized by Ectopic Calcification

3.4. Cancer-Associated Calcifications

3.5. Intracranial Calcification

4. Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SOST | gene encoding sclerostin |

| Wnt | Wingless-related integration site |

| Fz | Frizzled |

| LRP5/6 | Low-density Lipoprotein Receptor-related Protein 5/6 |

| TCF | T-cell factor |

| LEF | Lymphoid Enhancer-binding factor |

| PPARγ | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor γ |

| C/EBPα | CCAAT/Enhancer-Binding Protein α |

| Runx2 | Runt-related transcription factor 2 |

| OPG | Osteoprotegerin |

| RANKL | Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor Kappa-Β ligand |

| PTH | Parathyroid hormone |

| LRP4 | Low-density Lipoprotein Receptor-related Protein 4 |

| P1NP | Procollagen type 1 N-terminal Propeptide |

| BsAP | Bone-specific Alkaline Phosphatase |

| SIBLINGS | Small Integrin Binding Ligand N-Glycoproteins |

| MEPE | Matrix Extracellular Phosphoglycoprotein |

| ASARM | Acidic Serine Aspartate-Rich MEPE-associated motif |

| PHEX | Phosphate-regulating neutral Endopeptidase, X-linked |

| KO | Knockout |

| WT | Wild type |

| Bax | Bcl2- associated X protein |

| DMP1 | Dentin matrix acidic phosphoprotein 1 |

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| VSMC | Vascular smooth muscle cell |

| sFRP | secreted Frizzled-related protein |

| ESRD | End-stage renal disease |

| Jck | Juvenile cystic kidney |

| FGF23 | Fibroblast growth factor 23 |

| MGP | Matrix γ-carboxyglutamic acid |

| AVC | Aortic valve calcification |

| DKK3 | Dickkopf-related protein 3 |

| DKK1 | Dickkopf-related protein 1 |

References

- Truswell, A.S. Osteopetrosis with syndactyly; a morphological variant of Albers-Schonberg’s disease. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 1958, 40, 209–218. [Google Scholar]

- Buchem, V. Hyperostosis corticalis generalisata familiaris (van Buchem’s disease). Acta Radiol. 1955, 44, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beighton, P.; Barnard, A.; Hamersma, H.; van der Wouden, A. The syndromic status of sclerosteosis and van Buchem disease. Clin. Genet. 1984, 25, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Hul, W.; Balemans, W.; Van Hul, E.; Dikkers, F.G.; Obee, H.; Stokroos, R.J.; Hildering, P.; Vanhoenacker, F.; Van Camp, G.; Willems, P.J. Van Buchem disease (hyperostosis corticalis generalisata) maps to chromosome 17q12-q21. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1998, 62, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balemans, W.; Van Den Ende, J.; Freire Paes-Alves, A.; Dikkers, F.G.; Willems, P.J.; Vanhoenacker, F.; de Almeida-Melo, N.; Alves, C.F.; Stratakis, C.A.; Hill, S.C.; et al. Localization of the gene for sclerosteosis to the van Buchem disease-gene region on chromosome 17q12-q21. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1999, 64, 1661–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balemans, W.; Ebeling, M.; Patel, N.; Van Hul, E.; Olson, P.; Dioszegi, M.; Lacza, C.; Wuyts, W.; Van Den Ende, J.; Willems, P.; et al. Increased bone density in sclerosteosis is due to the deficiency of a novel secreted protein (SOST). Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001, 10, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunkow, M.E.; Gardner, J.C.; Van Ness, J.; Paeper, B.W.; Kovacevich, B.R.; Proll, S.; Skonier, J.E.; Zhao, L.; Sabo, P.J.; Fu, Y.; et al. Bone dysplasia sclerosteosis results from loss of the SOST gene product, a novel cystine knot-containing protein. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001, 68, 577–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balemans, W.; Patel, N.; Ebeling, M.; Van Hul, E.; Wuyts, W.; Lacza, C.; Dioszegi, M.; Dikkers, F.G.; Hildering, P.; Willems, P.J.; et al. Identification of a 52 kb deletion downstream of the SOST gene in patients with van Buchem disease. J. Med. Genet. 2002, 39, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staehling-Hampton, K.; Proll, S.; Paeper, B.W.; Zhao, L.; Charmley, P.; Brown, A.; Gardner, J.C.; Galas, D.; Schatzman, R.C.; Beighton, P.; et al. A 52-kb deletion in the SOST-MEOX1 intergenic region on 17q12-q21 is associated with van Buchem disease in the Dutch population. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2002, 110, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loots, G.G.; Kneissel, M.; Keller, H.; Baptist, M.; Chang, J.; Collette, N.M.; Ovcharenko, D.; Plajzer-Frick, I.; Rubin, E.M. Genomic deletion of a long-range bone enhancer misregulates sclerostin in Van Buchem disease. Genome Res. 2005, 15, 928–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Lierop, A.H.; Hamdy, N.A.; van Egmond, M.E.; Bakker, E.; Dikkers, F.G.; Papapoulos, S.E. Van Buchem disease: Clinical, biochemical, and densitometric features of patients and disease carriers. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2013, 28, 848–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, S.S.; Kojima, Y.; Yamaguchi, Y.L.; Nishinakamura, R.; Tam, P.P. Impact of WNT signaling on tissue lineage differentiation in the early mouse embryo. Dev. Growth Differ. 2011, 53, 843–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nusse, R.; Varmus, H. Three decades of Wnts: A personal perspective on how a scientific field developed. Embo J. 2012, 31, 2670–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, S.; Bennett, C.N.; Gerin, I.; Rapp, L.A.; Hankenson, K.D.; MacDougald, O.A. Wnt signaling stimulates osteoblastogenesis of mesenchymal precursors by suppressing CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 14515–14524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, C.N.; Longo, K.A.; Wright, W.S.; Suva, L.J.; Lane, T.F.; Hankenson, K.D.; MacDougald, O.A. Regulation of osteoblastogenesis and bone mass by Wnt10b. Proc. Natl Acad Sci USA 2005, 102, 3324–3329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robling, A.G.; Niziolek, P.J.; Baldridge, L.A.; Condon, K.W.; Allen, M.R.; Alam, I.; Mantila, S.M.; Gluhak-Heinrich, J.; Bellido, T.M.; Harris, S.E.; et al. Mechanical stimulation of bone in vivo reduces osteocyte expression of Sost/sclerostin. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 5866–5875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellido, T.; Ali, A.A.; Gubrij, I.; Plotkin, L.I.; Fu, Q.; O’Brien, C.A.; Manolagas, S.C.; Jilka, R.L. Chronic elevation of parathyroid hormone in mice reduces expression of sclerostin by osteocytes: A novel mechanism for hormonal control of osteoblastogenesis. Endocrinology 2005, 146, 4577–4583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, H.; Kneissel, M. SOST is a target gene for PTH in bone. Bone 2005, 37, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, K.; Roforth, M.M.; Demaray, S.; McGregor, U.; Kirmani, S.; McCready, L.K.; Peterson, J.M.; Drake, M.T.; Monroe, D.G.; Khosla, S. Effects of Estrogen on Bone mRNA Levels of Sclerostin and Other Genes Relevant to Bone Metabolism in Postmenopausal Women. J. Clin. Endocr. Metab. 2014, 99, E81–E88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudin, E.; Yorgan, T.; Fijalkowski, I.; Sonntag, S.; Steenackers, E.; Hendrickx, G.; Peeters, S.; De Mare, A.; Vervaet, B.; Verhulst, A.; et al. The Lrp4 R1170Q Homozygous Knock-In Mouse Recapitulates the Bone Phenotype of Sclerosteosis in Humans. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2017, 32, 1739–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Niklason, L.E. Small-diameter human vessel wall engineered from bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs). FASEB J. 2008, 22, 1635–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oswald, J.; Boxberger, S.; Jorgensen, B.; Feldmann, S.; Ehninger, G.; Bornhauser, M.; Werner, C. Mesenchymal stem cells can be differentiated into endothelial cells in vitro. Stem Cells 2004, 22, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thouverey, C.; Caverzasio, J. Sclerostin inhibits osteoblast differentiation without affecting BMP2/SMAD1/5 or Wnt3a/beta-catenin signaling but through activation of platelet-derived growth factor receptor signaling in vitro. Bonekey Rep. 2015, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padhi, D.; Jang, G.; Stouch, B.; Fang, L.; Posvar, E. Single-dose, placebo-controlled, randomized study of AMG 785, a sclerostin monoclonal antibody. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2011, 26, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.; David, V.; Laurence, J.S.; Schwarz, P.M.; Lafer, E.M.; Hedge, A.M.; Rowe, P.S.N. Degradation of MEPE, DMP1, and release of SIBLING ASARM-Peptides (Minhibins): ASARM-peptide(s) are directly responsible for defective mineralization in HYP. Endocrinology 2008, 149, 1757–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, P.S.N.; de Zoysa, P.A.; Dong, R.; Wang, H.R.; White, K.E.; Econs, M.J.; Oudet, C.L. MEPE, a new gene expressed in bone marrow and tumors causing osteomalacia. Genomics 2000, 67, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, P.S.N. The wrickkened pathways of FGF23, MEPE and PHEX. Crit Rev. Oral. Biol. M 2004, 15, 264–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Rowe, P.S.N.; Liu, S.G.; Simpson, L.G.; Xiao, Z.S.; Quarles, L.D. Inhibition of MEPE cleavage by Phex. Biochem. Bioph. Res. Co. 2002, 297, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, P.S.N.; Kumagai, Y.; Gutierrez, G.; Garrett, I.R.; Blacher, R.; Rosen, D.; Cundy, J.; Navvab, S.; Chen, D.; Drezner, M.K.; et al. MEPE has the properties of an osteoblastic phosphatonin and minhibin. Bone 2004, 34, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, G.J.; Rowe, P.S.; Lim, H.P.; Welldon, K.J.; Ormsby, R.; Wijenayaka, A.R.; Zelenchuk, L.; Evdokiou, A.; Findlay, D.M. Sclerostin Is a Locally Acting Regulator of Late-Osteoblast/Preosteocyte Differentiation and Regulates Mineralization Through a MEPE-ASARM-Dependent Mechanism. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2011, 26, 1425–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogawa, M.; Khalid, K.A.; Wijenayaka, A.R.; Ormsby, R.T.; Evdokiou, A.; Anderson, P.H.; Findlay, D.M.; Atkins, G.J. Recombinant sclerostin antagonizes effects of ex vivo mechanical loading in trabecular bone and increases osteocyte lacunar size. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Ph. 2018, 314, C53–C61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause, C.; Korchynskyi, O.; de Rooij, K.; Weidauer, S.E.; de Gorter, D.J.J.; van Bezooijen, R.L.; Hatsell, S.; Economides, A.N.; Mueller, T.D.; Lowik, C.W.G.M.; et al. Distinct Modes of Inhibition by Sclerostin on Bone Morphogenetic Protein and Wnt Signaling Pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 41614–41626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandra, A.; Lin, T.; Young, T.; Tong, W.; Ma, X.Y.; Tseng, W.J.; Kramer, I.; Kneissel, M.; Levine, M.A.; Zhang, Y.J.; et al. Suppression of Sclerostin Alleviates Radiation-Induced Bone Loss by Protecting Bone-Forming Cells and Their Progenitors Through Distinct Mechanisms. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2017, 32, 360–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, M.K.; Geoghegan, J.C.; Yu, C.P.; Turcott, E.; Skonier, J.E.; Winkler, D.G.; Latham, J.A. Sclerostin promotes the apoptosis of human osteoblastic cells: A novel regulation of bone formation. Bone 2004, 35, 828–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karsdal, M.A.; Larsen, L.; Engsig, M.T.; Lou, H.; Ferreras, M.; Lochter, A.; Delaisse, J.M.; Foged, N.T. Matrix metalloproteinase-dependent activation of latent transforming growth factor-beta controls the conversion of osteoblasts into osteocytes by blocking osteoblast apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 44061–44067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kollet, O.; Dar, A.; Shivtiel, S.; Kalinkovich, A.; Lapid, K.; Sztainberg, Y.; Tesio, M.; Samstein, R.M.; Goichberg, P.; Spiegel, A.; et al. Osteoclasts degrade endosteal components and promote mobilization of hematopoietic progenitor cells. Nat. Med. 2006, 12, 657–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everts, V.; Delaisse, J.M.; Korper, W.; Jansen, D.C.; Tigchelaar-Gutter, W.; Saftig, P.; Beertsen, W. The bone lining cell: Its role in cleaning Howship’s lacunae and initiating bone formation. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2002, 17, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ominsky, M.S.; Niu, Q.T.; Li, C.Y.; Li, X.D.; Ke, H.Z. Tissue-Level Mechanisms Responsible for the Increase in Bone Formation and Bone Volume by Sclerostin Antibody. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2014, 29, 1424–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.W.; Lu, Y.H.; Williams, E.A.; Lai, F.; Lee, J.Y.; Enishi, T.; Balani, D.H.; Ominsky, M.S.; Ke, H.Z.; Kronenberg, H.M.; et al. Sclerostin Antibody Administration Converts Bone Lining Cells Into Active Osteoblasts. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2017, 32, 892–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irie, K.; Ejiri, S.; Sakakura, Y.; Shibui, T.; Yajima, T. Matrix mineralization as a trigger for osteocyte maturation. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2008, 56, 561–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genetos, D.C.; Yellowley, C.E.; Loots, G.G. Prostaglandin E2 signals through PTGER2 to regulate sclerostin expression. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e17772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winkler, D.G.; Sutherland, M.K.; Geoghegan, J.C.; Yu, C.; Hayes, T.; Skonier, J.E.; Shpektor, D.; Jonas, M.; Kovacevich, B.R.; Staehling-Hampton, K.; et al. Osteocyte control of bone formation via sclerostin, a novel BMP antagonist. Embo J. 2003, 22, 6267–6276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kogawa, M.; Wijenayaka, A.R.; Ormsby, R.T.; Thomas, G.P.; Anderson, P.H.; Bonewald, L.F.; Findlay, D.M.; Atkins, G.J. Sclerostin regulates release of bone mineral by osteocytes by induction of carbonic anhydrase 2. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2013, 28, 2436–2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qing, H.; Ardeshirpour, L.; Pajevic, P.D.; Dusevich, V.; Jahn, K.; Kato, S.; Wysolmerski, J.; Bonewald, L.F. Demonstration of osteocytic perilacunar/canalicular remodeling in mice during lactation. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2012, 27, 1018–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsourdi, E.; Jahn, K.; Rauner, M.; Busse, B.; Bonewald, L.F. Physiological and pathological osteocytic osteolysis. J. Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2018, 18, 292–303. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, W.; Zeve, D.; Suh, J.M.; Wang, X.; Du, Y.; Zerwekh, J.E.; Dechow, P.C.; Graff, J.M.; Wan, Y. Biphasic and dosage-dependent regulation of osteoclastogenesis by beta-catenin. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011, 31, 4706–4719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijenayaka, A.R.; Kogawa, M.; Lim, H.P.; Bonewald, L.F.; Findlay, D.M.; Atkins, G.J. Sclerostin stimulates osteocyte support of osteoclast activity by a RANKL-dependent pathway. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e25900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weivoda, M.M.; Ruan, M.; Hachfeld, C.M.; Pederson, L.; Howe, A.; Davey, R.A.; Zajac, J.D.; Kobayashi, Y.; Williams, B.O.; Westendorf, J.J.; et al. Wnt Signaling Inhibits Osteoclast Differentiation by Activating Canonical and Noncanonical cAMP/PKA Pathways. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2016, 31, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmen, S.L.; Zylstra, C.R.; Mukherjee, A.; Sigler, R.E.; Faugere, M.C.; Bouxsein, M.L.; Deng, L.F.; Clemens, T.L.; Williams, B.O. Essential role of beta-catenin in postnatal bone acquisition. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 21162–21168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giachelli, C.M. Ectopic calcification: Gathering hard facts about soft tissue mineralization. Am. J. Pathol. 1999, 154, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, C.M.; Crouthamel, M.H.; Kapustin, A.; Giachelli, C.M. Arterial Calcification in Chronic Kidney Disease: Key Roles for Calcium and Phosphate. Circ. Res. 2011, 109, 697–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neven, E.; De Schutter, T.M.; De Broe, M.E.; D’Haese, P.C. Cell biological and physicochemical aspects of arterial calcification. Kidney Int. 2011, 79, 1166–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neven, E.; Persy, V.; Dauwe, S.; De Schutter, T.; De Broe, M.E.; D’Haese, P.C. Chondrocyte Rather Than Osteoblast Conversion of Vascular Cells Underlies Medial Calcification in Uremic Rats. Arterioscl Throm Vas 2010, 30, 1741–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, H.E.; Van der Heiden, K.; Farrell, E.; Gijsen, F.J.H.; Akyildiz, A.C. Calcifications in atherosclerotic plaques and impact on plaque biomechanics. J. Biomech. 2019, 87, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, A.M.; Sullivan, K.M.; D’Amore, P.A. Cultured endothelial cells display endogenous activation of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway and express multiple ligands, receptors, and secreted modulators of Wnt signaling. Dev. Dyn. 2006, 235, 3110–3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, A.M.; Kitajewski, J.; D’Amore, P.A. Wnt1 and Wnt5a affect endothelial proliferation and capillary length; Wnt2 does not. Growth Factors 2007, 25, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M.; Aikawa, M.; Szeto, W.; Papkoff, J. Identification of a Wnt-responsive signal transduction pathway in primary endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res. Commun. 1999, 263, 384–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Kim, D.W.; Ha, Y.; Ihm, M.H.; Kim, H.; Song, K.; Lee, I. Wnt5a induces endothelial inflammation via beta-catenin-independent signaling. J. Immunol. 2010, 185, 1274–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikram, A.; Kim, Y.R.; Kumar, S.; Naqvi, A.; Hoffman, T.A.; Kumar, A.; Miller, F.J., Jr.; Kim, C.S.; Irani, K. Canonical Wnt signaling induces vascular endothelial dysfunction via p66Shc-regulated reactive oxygen species. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc. Biol. 2014, 34, 2301–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Liu, Z.; Park, S.H.; Gwag, T.; Lu, W.; Ma, M.; Sui, Y.; Zhou, C. Myeloid beta-Catenin Deficiency Exacerbates Atherosclerosis in Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor-Deficient Mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc. Biol. 2018, 38, 1468–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaale, K.; Neumann, J.; Schneider, D.; Ehlers, S.; Reiling, N. Wnt signaling in macrophages: Augmenting and inhibiting mycobacteria-induced inflammatory responses. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2011, 90, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borrell-Pages, M.; Romero, J.C.; Badimon, L. Cholesterol modulates LRP5 expression in the vessel wall. Atherosclerosis 2014, 235, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magoori, K.; Kang, M.J.; Ito, M.R.; Kakuuchi, H.; Ioka, R.X.; Kamataki, A.; Kim, D.H.; Asaba, H.; Iwasaki, S.; Takei, Y.A.; et al. Severe hypercholesterolemia, impaired fat tolerance, and advanced atherosclerosis in mice lacking both low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 and apolipoprotein E. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 11331–11336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchand, A.; Atassi, F.; Gaaya, A.; Leprince, P.; Le Feuvre, C.; Soubrier, F.; Lompre, A.M.; Nadaud, S. The Wnt/beta-catenin pathway is activated during advanced arterial aging in humans. Aging Cell 2011, 10, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezan, J.; Leroux, L.; Barandon, L.; Dufourcq, P.; Jaspard, W.; Moreau, C.; Allieres, C.; Daret, D.; Couffinhal, T.; Duplaa, C. FrzA/sFRP-1, a secreted antagonist of the Wnt-Frizzled pathway, controls vascular cell proliferation in vitro and in vivo. Cardiovasc Res. 2004, 63, 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leto, G.; D’Onofrio, L.; Lucantoni, F.; Zampetti, S.; Campagna, G.; Foffi, C.; Moretti, C.; Carlone, A.; Palermo, A.; Leopizzi, M.; et al. Sclerostin is expressed in the atherosclerotic plaques of patients who undergoing carotid endarterectomy. Diabetes Metab Res. 2019, 35, e3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Santana, S.; Garcia-Fontana, B.; Garcia-Martin, A.; Rozas-Moreno, P.; Garcia-Salcedo, J.A.; Reyes-Garcia, R.; Munoz-Torres, M. Atherosclerotic Disease in Type 2 Diabetes Is Associated With an Increase in Sclerostin Levels. Diabetes Care 2013, 36, 1667–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, S.M.; Seto, S.W.; Jose, R.J.; Li, J.; Morton, S.K.; Biros, E.; Wang, Y.; Nsengiyumva, V.; Lindeman, J.H.N.; Loots, G.G.; et al. Wnt Signaling Pathway Inhibitor Sclerostin Inhibits Angiotensin II-Induced Aortic Aneurysm and Atherosclerosis. Arterioscl Throm Vas 2017, 37, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S.; Ishibashi-Ueda, H.; Niizuma, S.; Yoshihara, F.; Horio, T.; Kawano, Y. Coronary Calcification in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease and Coronary Artery Disease. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephro 2009, 4, 1892–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, A.; Waddell, I.C.; Friesen, R.W.; Michalski, R.T. Monckeberg medial calcific sclerosis mimicking malignant calcification pattern at mammography. J. Clin. Pathol. 2005, 58, 447–448. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, B.V.; Torczynski, E.; Edward, D.P. Monckeberg’s sclerosis in temporal artery biopsy specimens. Brit. J. Ophthalmol. 1999, 83, 1091–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, D.; Wang, Q.; Hao, L.R. Aberrant activation of Wnt pathways in arteries associates with vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2016, 48, 1313–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, F.; Wang, H.; Ren, W.Y.; Ma, Y.; Liao, Y.P.; Zhu, J.H.; Cui, J.; Deng, Z.L.; Su, Y.X.; Gan, H.; et al. BMP9/COX-2 axial mediates high phosphate-induced calcification in vascular smooth muscle cells via Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. J. Cell. Biochem. 2018, 119, 2851–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, X.C.; Rong, S.; Yuan, W.J.; Gu, L.J.; Jia, J.S.; Wang, L.; Yu, H.L.; Zhuge, Y.F. Frontiers in Physiology High Mobility Group Box 1 Promotes Aortic Calcification in Chronic Kidney Disease via the Wnt/beta-Catenin Pathway. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, J.; Shen, Z.; Gu, Y.; Xu, L.; Hu, J.; Zhang, X.; Ding, X. Indoxyl sulfate accelerates vascular smooth muscle cell calcification via microRNA-29b dependent regulation of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Toxicol. Lett. 2018, 284, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, D.; Diao, Z.; Han, X.; Liu, W. Secreted Frizzled-Related Protein 5 Attenuates High Phosphate-Induced Calcification in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells by Inhibiting the Wnt/ss-Catenin Pathway. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2016, 99, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, B.Y.; Yao, L.; Sheng, Z.T.; Wan, P.Z.; Qiu, X.B.; Wang, J.; Xu, T.H. Specific knockdown of WNT8b expression protects against phosphate-induced calcification in vascular smooth muscle cells by inhibiting the Wnt-beta-catenin signaling pathway. J. Cell Physiol. 2019, 234, 3469–3477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, S.; Zhao, X.Z.; Jin, X.C.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, L.; Zhu, Y.X.; Yuan, W.J. Vascular Calcification in Chronic Kidney Disease is Induced by Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2 via a Mechanism Involving the Wnt/beta-Catenin Pathway. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2014, 34, 2049–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freise, C.; Kretzschmar, N.; Querfeld, U. Wnt signaling contributes to vascular calcification by induction of matrix metalloproteinases. BMC Cardiovasc Disor. 2016, 16, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, R.X.; Wang, L.Y.; Li, J.M.; Xiong, Y.Q.; Li, Y.P.; Han, M.; Jiang, H.; Anil, M.; Su, B.H. Vascular Calcification Is Associated with Wnt-Signaling Pathway and Blood Pressure Variability in Chronic Kidney Disease Rats. Nephrol Dial. Transpl. 2019, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, B.; Zhang, S.Y.; Guan, S.M.; Zhou, S.Q.; Fang, X. Role of Wnt/beta-Catenin Pathway in the Arterial Medial Calcification and Its Effect on the OPG/RANKL System. Curr Med. Sci. 2019, 39, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faverman, L.; Mikhaylova, L.; Malmquist, J.; Nurminskaya, M. Extracellular transglutaminase 2 activates beta-catenin signaling in calcifying vascular smooth muscle cells. Febs Lett. 2008, 582, 1552–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeadin, M.G.; Butcher, M.K.; Shaughnessy, S.G.; Werstuck, G.H. Leptin promotes osteoblast differentiation and mineralization of primary cultures of vascular smooth muscle cells by inhibiting glycogen synthase kinase (GSK)-3 beta. Biochem. Bioph. Res. Co 2012, 425, 924–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.Y.; Shan, J.G.; Yang, W.G.; Zheng, H.; Xue, S. High Mobility Group Box 1 (HMGB1) Mediates High-Glucose-Induced Calcification in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells of Saphenous Veins. Inflammation 2013, 36, 1592–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.S.; Cheng, S.L.; Pingsterhaus, J.M.; Charlton-Kachigian, N.; Loewy, A.R.; Towler, D.A. Msx2 promotes cardiovascular calcification by activating paracrine Wnt signals. J. Clin. Investig. 2005, 115, 1210–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, T.; Sun, D.Q.; Duan, Y.; Wen, P.; Dai, C.S.; Yang, J.W.; He, W.C. WNT/beta-catenin signaling promotes VSMCs to osteogenic transdifferentiation and calcification through directly modulating Runx2 gene expression. Exp. Cell Res. 2016, 345, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mare, A.; Maudsley, S.; Azmi, A.; Hendrickx, J.O.; Opdebeeck, B.; Neven, E.; D’Haese, P.C.; Verhulst, A. Sclerostin as Regulatory Molecule in Vascular Media Calcification and the Bone-Vascular Axis. Toxins 2019, 11, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Qiu, X.B.; Xu, T.H.; Sheng, Z.T.; Yao, L. Sclerostin/Receptor Related Protein 4 and Ginkgo Biloba Extract Alleviates beta-Glycerophosphate-Induced Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Calcification By Inhibiting Wnt/beta-Catenin Pathway. Blood Purificat 2019, 47, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oca, A.M.; Guerrero, F.; Martinez-Moreno, J.M.; Madueno, J.A.; Herencia, C.; Peralta, A.; Almaden, Y.; Lopez, I.; Aguilera-Tejero, E.; Gundlach, K.; et al. Magnesium Inhibits Wnt/beta-Catenin Activity and Reverses the Osteogenic Transformation of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e89525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herencia, C.; Rodriguez-Ortiz, M.E.; Munoz-Castaneda, J.R.; Martinez-Moreno, J.M.; Canalejo, R.; Montes de Oca, A.; Diaz-Tocados, J.M.; Peralbo-Santaella, E.; Marin, C.; Canalejo, A.; et al. Angiotensin II prevents calcification in vascular smooth muscle cells by enhancing magnesium influx. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2015, 45, 1129–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.L.; Mao, H.J.; Chen, C.; Wu, L.; Wang, N.N.; Zhao, X.F.; Qian, J.; Xing, C.Y. The Role and Mechanism of alpha-Klotho in the Calcification of Rat Aortic Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 194362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, Y.; Nakamura, K.; Miura, D.; Yunoki, K.; Miyoshi, T.; Yoshida, M.; Kawakita, N.; Kimura, T.; Kondo, M.; Sarashina, T.; et al. Suppression of Wnt Signaling and Osteogenic Changes in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells by Eicosapentaenoic Acid. Nutrients 2017, 9, 858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, M.; Chen, T.L.; Wu, L.; Zhao, X.F.; Mao, H.J.; Xing, C.Y. Effect of pioglitazone on the calcification of rat vascular smooth muscle cells through the downregulation of the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 16, 6208–6213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freise, C.; Bobb, V.; Querfeld, U. Collagen XIV and a related recombinant fragment protect human vascular smooth muscle cells from calcium-/phosphate-induced osteochondrocytic transdifferentiation. Exp. Cell Res. 2017, 358, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Bao, S.M.; Guo, W.; Diao, Z.L.; Wang, L.Y.; Han, X.; Guo, W.K.; Liu, W.H. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes alleviate high phosphorus-induced vascular smooth muscle cells calcification by modifying microRNA profiles. Funct Integr. Genom. 2019, 19, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, P.; Chen, N.X.; O’Neill, K.; McClintick, J.N.; Moe, S.M.; Janga, S.C. Differential miRNA Expression in Cells and Matrix Vesicles in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells from Rats with Kidney Disease. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0131589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.L.; Shao, J.S.; Halstead, L.R.; Distelhorst, K.; Sierra, O.; Towler, D.A. Activation of Vascular Smooth Muscle Parathyroid Hormone Receptor Inhibits Wnt/beta-Catenin Signaling and Aortic Fibrosis in Diabetic Arteriosclerosis. Circ. Res. 2010, 107, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Li, Y.; Du, Y.; Li, G.; Wang, L.; Zhou, F. Resveratrol Ameliorated Vascular Calcification by Regulating Sirt-1 and Nrf2. Transpl. P 2016, 48, 3378–3386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoli-Leonard, F.; Wilkinson, F.L.; Langford-Smith, A.W.W.; Alexander, M.Y.; Weston, R. The Interplay of SIRT1 and Wnt Signaling in Vascular Calcification. Front. Cardiovasc Med. 2018, 5, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.Y.; Ryu, H.M.; Oh, E.J.; Choi, J.Y.; Cho, J.H.; Kim, C.D.; Kim, Y.L.; Park, S.H. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor gemigliptin protects against vascular calcification in an experimental chronic kidney disease and vascular smooth muscle cells. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalhoub, V.; Shatzen, E.; Henley, C.; Boedigheimer, M.; McNinch, J.; Manoukian, R.; Damore, M.; Fitzpatrick, D.; Haas, K.; Twomey, B.; et al. Calcification inhibitors and Wnt signaling proteins are implicated in bovine artery smooth muscle cell calcification in the presence of phosphate and vitamin D sterols. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2006, 79, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Moreno, J.M.; Munoz-Castaneda, J.R.; Herencia, C.; de Oca, A.M.; Estepa, J.C.; Canalejo, R.; Rodriguez-Ortiz, M.E.; Perez-Martinez, P.; Aguilera-Tejero, E.; Canalejo, A.; et al. In vascular smooth muscle cells paricalcitol prevents phosphate-induced Wnt/beta-catenin activation. Am. J. Physiol. Renal 2012, 303, F1136–F1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelletier, S.; Dubourg, L.; Carlier, M.C.; Hadj-Aissa, A.; Fouque, D. The Relation between Renal Function and Serum Sclerostin in Adult Patients with CKD. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephro 2013, 8, 819–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cejka, D.; Jager-Lansky, A.; Kieweg, H.; Weber, M.; Bieglmayer, C.; Haider, D.G.; Diarra, D.; Patsch, J.M.; Kainberger, F.; Bohle, B.; et al. Sclerostin serum levels correlate positively with bone mineral density and microarchitecture in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial. Transpl. 2012, 27, 226–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cejka, D.; Marculescu, R.; Kozakowski, N.; Plischke, M.; Reiter, T.; Gessl, A.; Haas, M. Renal Elimination of Sclerostin Increases With Declining Kidney Function. J. Clin. Endocr. Metab. 2014, 99, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbagh, Y.; Graciolli, F.G.; O’Brien, S.; Tang, W.; dos Reis, L.M.; Ryan, S.; Phillips, L.; Boulanger, J.; Song, W.P.; Bracken, C.; et al. Repression of osteocyte Wnt/beta-catenin signaling is an early event in the progression of renal osteodystrophy. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2012, 27, 1757–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, A.R.; Olauson, H.; Witasp, A.; Haarhaus, M.; Brandenburg, V.; Wernerson, A.; Lindholm, B.; Soderberg, M.; Wennberg, L.; Nordfors, L.; et al. Increased circulating sclerostin levels in end-stage renal disease predict biopsy-verified vascular medial calcification and coronary artery calcification. Kidney Int. 2015, 88, 1356–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisson, S.K.; Ung, R.V.; Picard, S.; Valade, D.; Agharazii, M.; Lariviere, R.; Mac-Way, F. High calcium, phosphate and calcitriol supplementation leads to an osteocyte-like phenotype in calcified vessels and bone mineralisation defect in uremic rats. J. Bone Miner. Metab 2019, 37, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Lopez, N.; Panizo, S.; Alonso-Montes, C.; Martinez-Arias, L.; Avello, N.; Sosa, P.; Dusso, A.S.; Cannata-Andia, J.B.; Naves-Diaz, M. High-serum phosphate and parathyroid hormone distinctly regulate bone loss and vascular calcification in experimental chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial. Transpl. 2019, 34, 934–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramann, R.; Brandenburg, V.M.; Schurgers, L.J.; Ketteler, M.; Westphal, S.; Leisten, I.; Bovi, M.; Jahnen-Dechent, W.; Knuchel, R.; Floege, J.; et al. Novel insights into osteogenesis and matrix remodelling associated with calcific uraemic arteriolopathy. Nephrol Dial. Transpl. 2013, 28, 856–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandenburg, V.M.; Kramann, R.; Rothe, H.; Kaesler, N.; Korbiel, J.; Specht, P.; Schmitz, S.; Kruger, T.; Floege, J.; Ketteler, M. Calcific uraemic arteriolopathy (calciphylaxis): Data from a large nationwide registry. Nephrol Dial. Transpl. 2017, 32, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, T.Y.; Chen, N.C.; Hsu, C.Y.; Huang, C.W.; Lee, P.T.; Chou, K.J.; Fang, H.C.; Chen, C.L. Evaluation of the association of Wnt signaling with coronary artery calcification in patients on dialysis with severe secondary hyperparathyroidism. BMC Nephrol. 2019, 20, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuipers, A.L.; Miljkovic, I.; Carr, J.J.; Terry, J.G.; Nestlerode, C.S.; Ge, Y.R.; Bunker, C.H.; Patrick, A.L.; Zmuda, J.M. Association of circulating sclerostin with vascular calcification in Afro-Caribbean men. Atherosclerosis 2015, 239, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morena, M.; Jaussent, I.; Dupuy, A.M.; Bargnoux, A.S.; Kuster, N.; Chenine, L.; Leray-Moragues, H.; Klouche, K.; Vernhet, H.; Canaud, B.; et al. Osteoprotegerin and sclerostin in chronic kidney disease prior to dialysis: Potential partners in vascular calcifications. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 2015, 30, 1345–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelletier, S.; Confavreux, C.B.; Haesebaert, J.; Guebre-Egziabher, F.; Bacchetta, J.; Carlier, M.C.; Chardon, L.; Laville, M.; Chapurlat, R.; London, G.M.; et al. Serum sclerostin: The missing link in the bone-vessel cross-talk in hemodialysis patients? Osteoporos. Int. 2015, 26, 2165–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.T.; Ng, H.Y.; Chiu, T.T.Y.; Li, L.C.; Pei, S.N.; Kuo, W.H.; Lee, C.T. Association of bone-derived biomarkers with vascular calcification in chronic hemodialysis patients. Clin. Chim. Acta 2016, 452, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, W.; Guan, L.N.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, S.Q.; Cao, B.F.; Ji, Y.Q. Sclerostin as a new key factor in vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease stages 3 and 4. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2016, 48, 2043–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, H.S.; Winther, S.; Dupont, L.; Bottcher, M.; Rejnmark, L.; Hauge, E.M.; Svensson, M.; Ivarsen, P. Sclerostin is not associated with cardiovascular event or fracture in kidney transplantation candidates. Clin. Nephrol. 2018, 90, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.Y.; Chang, Z.F.; Chau, Y.P.; Chen, A.; Yang, W.C.; Yang, A.H.; Lee, O.K.S. Circulating Wnt/beta-catenin signalling inhibitors and uraemic vascular calcifications. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 2015, 30, 1356–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evenepoel, P.; Goffin, E.; Meijers, B.; Kanaan, N.; Bammens, B.; Coche, E.; Claes, K.; Jadoul, M. Sclerostin Serum Levels and Vascular Calcification Progression in Prevalent Renal Transplant Recipients. J. Clin. Endocr. Metab. 2015, 100, 4669–4676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borawski, J.; Zoltko, J.; Labij-Reduta, B.; Koc-Zorawska, E.; Naumnik, B. Effects of Enoxaparin on Intravascular Sclerostin Release in Healthy Men. J. Cardiovasc. Pharm T 2018, 23, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Mare, A.; Verhulst, A.; Cavalier, E.; Delanaye, P.; Behets, G.J.; Meijers, B.; Kuypers, D.; D’Haese, P.C.; Evenepoel, P. Clinical Inference of Serum and Bone Sclerostin Levels in Patients with End-Stage Kidney Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delanaye, P.; Paquot, F.; Bouquegneau, A.; Blocki, F.; Krzesinski, J.M.; Evenepoel, P.; Pottel, H.; Cavalier, E. Sclerostin and chronic kidney disease: The assay impacts what we (thought to) know. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 2018, 33, 1404–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piec, I.; Washbourne, C.; Tang, J.; Fisher, E.; Greeves, J.; Jackson, S.; Fraser, W.D. How Accurate is Your Sclerostin Measurement? Comparison Between Three Commercially Available Sclerostin ELISA Kits. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2016, 98, 546–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, M.; Hanafusa, N.; Kawaguchi, H.; Tsuchiya, K.; Nitta, K. A Prospective Cohort Study Showing No Association Between Serum Sclerostin Level and Mortality in Maintenance Hemodialysis Patients. Kidney Blood Press R 2018, 43, 1023–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowak, A.; Artunc, F.; Serra, A.L.; Pollock, E.; Krayenbuhl, P.A.; Muller, C.; Friedrich, B. Sclerostin Quo Vadis?—Is This a Useful Long-Term Mortality Parameter in Prevalent Hemodialysis Patients? Kidney Blood Press R 2015, 40, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delanaye, P.; Krzesinski, J.M.; Warling, X.; Moonen, M.; Smelten, N.; Medart, L.; Bruyere, O.; Reginster, J.Y.; Pottel, H.; Cavalier, E. Clinical and Biological Determinants of Sclerostin Plasma Concentration in Hemodialysis Patients. Nephron Clin. Pract. 2014, 128, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalves, F.L.C.; Elias, R.M.; dos Reis, L.M.; Graciolli, F.G.; Zampieri, F.G.; Oliveira, R.B.; Jorgetti, V.; Moyses, R.M.A. Serum sclerostin is an independent predictor of mortality in hemodialysis patients. BMC Nephrol. 2014, 15, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drechsler, C.; Evenepoel, P.; Vervloet, M.G.; Wanner, C.; Ketteler, M.; Marx, N.; Floege, J.; Dekker, F.W.; Brandenburg, V.M.; Grp, N.S. High levels of circulating sclerostin are associated with better cardiovascular survival in incident dialysis patients: Results from the NECOSAD study. Nephrol Dial. Transpl. 2015, 30, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jean, G.; Chazot, C.; Bresson, E.; Zaoui, E.; Cavalier, E. High Serum Sclerostin Levels Are Associated with a Better Outcome in Haemodialysis Patients. Nephron 2016, 132, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.R.; Yuan, L.A.; Zhang, J.J.; Hao, L.; Wang, D.G. Serum sclerostin values are associated with abdominal aortic calcification and predict cardiovascular events in patients with chronic kidney disease stages 3-5D. Nephrology 2017, 22, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lips, L.; van Zuijdewijn, C.L.M.D.; Ter Wee, P.M.; Bots, M.L.; Blankestijn, P.J.; van den Dorpel, M.A.; Fouque, D.; de Jongh, R.; Pelletier, S.; Vervloet, M.G.; et al. Serum sclerostin: Relation with mortality and impact of hemodiafiltration. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 2017, 32, 1217–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persy, V.; D’Haese, P. Vascular calcification and bone disease: The calcification paradox. Trends Mol. Med. 2009, 15, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viaene, L.; Behets, G.J.; Claes, K.; Meijers, B.; Blocki, F.; Brandenburg, V.; Evenepoel, P.; D’Haese, P.C. Sclerostin: Another bone-related protein related to all-cause mortality in haemodialysis? Nephrol Dial. Transpl. 2013, 28, 3024–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rattazzi, M.; Bertacco, E.; Del Vecchio, A.; Puato, M.; Faggin, E.; Pauletto, P. Aortic valve calcification in chronic kidney disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 2013, 28, 2968–2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, G.J.; Chen, T.; Zhou, H.M.; Sun, K.X.; Li, J. Role of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway in the mechanism of calcification of aortic valve. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technol. Med. Sci. 2014, 34, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandenburg, V.M.; Kramann, R.; Koos, R.; Kruger, T.; Schurgers, L.; Muhlenbruch, G.; Hubner, S.; Gladziwa, U.; Drechsler, C.; Ketteler, M. Relationship between sclerostin and cardiovascular calcification in hemodialysis patients: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nephrol. 2013, 14, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koos, R.; Brandenburg, V.; Mahnken, A.H.; Schneider, R.; Dohmen, G.; Autschbach, R.; Marx, N.; Kramann, R. Sclerostin as a Potential Novel Biomarker for Aortic Valve. J. Heart Valve Dis 2013, 22, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.Q.; Guan, L.N.; Yu, S.X.; Yin, P.Y.; Shen, X.Q.; Sun, Z.W.; Liu, J.; Lv, W.; Yu, G.P.; Ren, C. Serum sclerostin as a potential novel biomarker for heart valve calcification in patients with chronic kidney disease. Eur Rev. Med. Pharmaco 2018, 22, 8822–8829. [Google Scholar]

- Munroe, P.B.; Olgunturk, R.O.; Fryns, J.P.; Van Maldergem, L.; Ziereisen, F.; Yuksel, B.; Gardiner, R.M.; Chung, E. Mutations in the gene encoding the human matrix Gla protein cause Keutel syndrome. Nat. Genet. 1999, 21, 142–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutsch, F.; Ruf, N.; Vaingankar, S.; Toliat, M.R.; Suk, A.; Hohne, W.; Schauer, G.; Lehmann, M.; Roscioli, T.; Schnabel, D.; et al. Mutations in ENPP1 are associated with ‘idiopathic’ infantile arterial calcification. Nat. Genet. 2003, 34, 379–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nitschke, Y.; Baujat, G.; Botschen, U.; Wittkampf, T.; du Moulin, M.; Stella, J.; Le Merrer, M.; Guest, G.; Lambot, K.; Tazarourte-Pinturier, M.F.; et al. Generalized Arterial Calcification of Infancy and Pseudoxanthoma Elasticum Can Be Caused by Mutations in Either ENPP1 or ABCC6. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012, 90, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pendleton, A.; Johnson, M.D.; Hughes, A.; Gurley, K.A.; Ho, A.M.; Doherty, M.; Dixey, J.; Gillet, P.; Loeuille, D.; McGrath, R.; et al. Mutations in ANKH cause chondrocalcinosis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2002, 71, 933–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- St Hilaire, C.; Ziegler, S.G.; Markello, T.C.; Brusco, A.; Groden, C.; Gill, F.; Carlson-Donohoe, H.; Lederman, R.J.; Chen, M.Y.; Yang, D.; et al. NT5E Mutations and Arterial Calcifications. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 432–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafaelsen, S.; Johansson, S.; Raeder, H.; Bjerknes, R. Long-term clinical outcome and phenotypic variability in hyperphosphatemic familial tumoral calcinosis and hyperphosphatemic hyperostosis syndrome caused by a novel GALNT3 mutation; case report and review of the literature. BMC Genet. 2014, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, S.C.; Sears, R.L.; Lemos, R.R.; Quintans, B.; Huang, A.; Spiteri, E.; Nevarez, L.; Mamah, C.; Zatz, M.; Pierce, K.D.; et al. Mutations in SLC20A2 are a major cause of familial idiopathic basal ganglia calcification. Neurogenetics 2013, 14, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarb, Y.; Weber-Stadlbauer, U.; Kirschenbaum, D.; Kindler, D.R.; Richetto, J.; Keller, D.; Rademakers, R.; Dickson, D.W.; Pasch, A.; Byzova, T.; et al. Ossified blood vessels in primary familial brain calcification elicit a neurotoxic astrocyte response. Brain 2019, 142, 885–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellahcene, A.; Castronovo, V. Expression of bone matrix proteins in human breast cancer: Potential roles in microcalcification formation and in the genesis of bone metastases. Bull. Cancer 1997, 84, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Grewal, R.G.; Austin, J.H. CT demonstration of calcification in carcinoma of the lung. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 1994, 18, 867–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakkos, S.K.; Scopa, C.D.; Chalmoukis, A.K.; Karachalios, D.A.; Spiliotis, J.D.; Harkoftakis, J.G.; Karavias, D.D.; Androulakis, J.A.; Vagenakis, A.G. Relative risk of cancer in sonographically detected thyroid nodules with calcifications. J. Clin. Ultrasound 2000, 28, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimas, R.; Bennett, B.; Gardner, W.A., Jr. Prostatic calculi: A review. Prostate 1985, 7, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livingston, J.H.; Stivaros, S.; Warren, D.; Crow, Y.J. Intracranial calcification in childhood: A review of aetiologies and recognizable phenotypes. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2014, 56, 612–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemos, R.R.; Ferreira, J.B.; Keasey, M.P.; Oliveira, J.R. An update on primary familial brain calcification. Int Rev. Neurobiol. 2013, 110, 349–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westenberger, A.; Balck, A.; Klein, C. Primary familial brain calcifications: Genetic and clinical update. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2019, 32, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassanein, A.M.; Glanz, S.M.; Kessler, H.P.; Eskin, T.A.; Liu, C. Beta-catenin is expressed aberrantly in tumors expressing shadow cells—Pilomatricoma, craniopharyngioma, and calcifying odontogenic cyst. Am. J. Clin. Pathol 2003, 120, 732–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juca, C.E.B.; Colli, L.M.; Martins, C.S.; Campanini, M.L.; Paixao, B.; Juca, R.V.; Saggioro, F.P.; de Oliveira, R.S.; Moreira, A.C.; Machado, H.R.; et al. Impact of the Canonical Wnt Pathway Activation on the Pathogenesis and Prognosis of Adamantinomatous Craniopharyngiomas. Horm Metab Res. 2018, 50, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplon, H.; Muralidharan, M.; Schneider, Z.; Reichert, J.M. Antibodies to watch in 2020. MAbs 2020, 12, 1703531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandenburg, V.M.; Verhulst, A.; Babler, A.; D’Haese, P.C.; Evenepoel, P.; Kaesler, N. Sclerostin in chronic kidney disease-mineral bone disorder think first before you block it! Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 2019, 34, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saag, K.G.; Petersen, J.; Brandi, M.L.; Karaplis, A.C.; Lorentzon, M.; Thomas, T.; Maddox, J.; Fan, M.; Meisner, P.D.; Grauer, A. Romosozumab or Alendronate for Fracture Prevention in Women with Osteoporosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1417–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukita, M.; Yamaguchi, T.; Ohata, N.; Tamura, M. Sclerostin Enhances Adipocyte Differentiation in 3T3-L1 Cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 2016, 117, 1419–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairfield, H.; Falank, C.; Harris, E.; Demambro, V.; McDonald, M.; Pettitt, J.A.; Mohanty, S.T.; Croucher, P.; Kramer, I.; Kneissel, M.; et al. The skeletal cell-derived molecule sclerostin drives bone marrow adipogenesis. J. Cell Physiol. 2018, 233, 1156–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beier, E.E.; Sheu, T.J.; Resseguie, E.A.; Takahata, M.; Awad, H.A.; Cory-Slechta, D.A.; Puzas, J.E. Sclerostin activity plays a key role in the negative effect of glucocorticoid signaling on osteoblast function in mice. Bone Res. 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.P.; Frey, J.L.; Li, Z.; Kushwaha, P.; Zoch, M.L.; Tomlinson, R.E.; Da, H.; Aja, S.; Noh, H.L.; Kim, J.K.; et al. Sclerostin influences body composition by regulating catabolic and anabolic metabolism in adipocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E11238–E11247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L.J.; Zhang, L.; Yang, J.; Hao, L.R. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma inhibits vascular calcification by upregulating Klotho. Exp. Ther Med. 2017, 13, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woldt, E.; Terrand, J.; Mlih, M.; Matz, R.L.; Bruban, V.; Coudane, F.; Foppolo, S.; El Asmar, Z.; Chollet, M.E.; Ninio, E.; et al. The nuclear hormone receptor PPAR gamma counteracts vascular calcification by inhibiting Wnt5a signalling in vascular smooth muscle cells. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouinard, L.; Felx, M.; Mellal, N.; Varela, A.; Mann, P.; Jolette, J.; Samadfam, R.; Smith, S.Y.; Locher, K.; Buntich, S.; et al. Carcinogenicity risk assessment of romosozumab: A review of scientific weight-of-evidence and findings in a rat lifetime pharmacology study. Regul. Toxicol Pharm. 2016, 81, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ominsky, M.S.; Boyd, S.K.; Varela, A.; Jolette, J.; Felx, M.; Doyle, N.; Mellal, N.; Smith, S.Y.; Locher, K.; Buntich, S.; et al. Romosozumab Improves Bone Mass and Strength While Maintaining Bone Quality in Ovariectomized Cynomolgus Monkeys. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2017, 32, 788–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pflanz, D.; Birkhold, A.I.; Albiol, L.; Thiele, T.; Julien, C.; Seliger, A.; Thomson, E.; Kramer, I.; Kneissel, M.; Duda, G.N.; et al. Sost deficiency led to a greater cortical bone formation response to mechanical loading and altered gene expression. Sci Rep. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Lierop, A.H.; Moester, M.J.C.; Hamdy, N.A.T.; Papapoulos, S.E. Serum Dickkopf 1 Levels in Sclerostin Deficiency. J. Clin. Endocr. Metab. 2014, 99, E252–E256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.H.; Keller, J.J.; Lin, H.C. Bisphosphonates reduced the risk of acute myocardial infarction: A 2-year follow-up study. Osteoporosis Int. 2013, 24, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Rogers, J.R.; Fulchino, L.A.; Kim, C.A.; Solomon, D.H.; Kim, S.C. Bisphosphonates and Risk of Cardiovascular Events: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kranenburg, G.; Bartstra, J.W.; Weijmans, M.; de Jong, P.A.; Mali, W.P.; Verhaar, H.J.; Visseren, F.L.J.; Spiering, W. Bisphosphonates for cardiovascular risk reduction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis 2016, 252, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EVENITY™ (romosozumab-aqqg), U.S. Prescribing Information. Available online: https://www.pi.amgen.com/~/media/amgen/repositorysites/pi-amgen-com/evenity/evenity_pi_hcp_english.ashx (accessed on 18 March 2020).

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De Maré, A.; D’Haese, P.C.; Verhulst, A. The Role of Sclerostin in Bone and Ectopic Calcification. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3199. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21093199

De Maré A, D’Haese PC, Verhulst A. The Role of Sclerostin in Bone and Ectopic Calcification. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020; 21(9):3199. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21093199

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Maré, Annelies, Patrick C. D’Haese, and Anja Verhulst. 2020. "The Role of Sclerostin in Bone and Ectopic Calcification" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21, no. 9: 3199. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21093199

APA StyleDe Maré, A., D’Haese, P. C., & Verhulst, A. (2020). The Role of Sclerostin in Bone and Ectopic Calcification. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(9), 3199. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21093199