Evaluation of Polymeric Matrix Loaded with Melatonin for Wound Dressing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

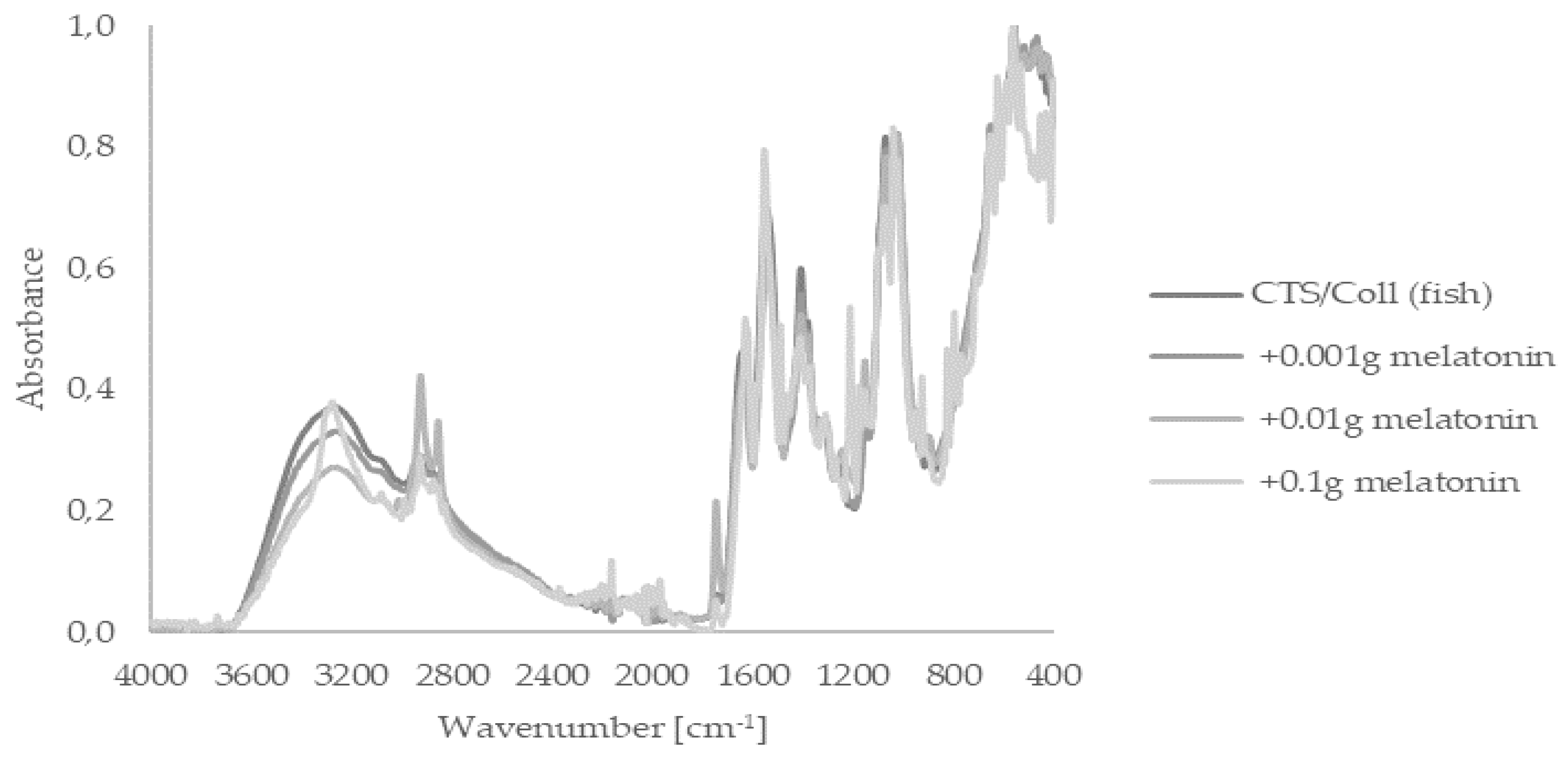

2.1. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy—Attenuated Total Reflectance (FTIR–ATR)

2.2. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

2.3. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TG)

2.4. Cellular Assessments Using Cutaneous Models

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents

4.2. Sample Preparation

4.3. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy—Attenuated Total Reflectance (FTIR–ATR)

4.4. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

4.5. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TG)

4.6. Cell Culture

4.7. Cell Viability Assay

4.8. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Działo, M.; Mierziak, J.; Korzun, U.; Preisner, M.; Szopa, J.; Kulma, A. The Potential of Plant Phenolics in Prevention and Therapy of Skin Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardeland, R.; Fuhrberg, B. Ubiquitous melatonin—Presence and effects in unicells, plants and animals. Trends Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 1996, 2, 25–45. [Google Scholar]

- Paredes, S.D.; Korkmaz, A.; Manchester, L.C.; Tan, D.-X.; Reiter, R.J. Phytomelatonin: A review. J. Exp. Bot. 2009, 60, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, R.J. Pineal Melatonin: Cell Biology of Its Synthesis and of Its Physiological Interactions. Endocr. Rev. 1991, 12, 151–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.-X.; Hardeland, R.; Manchester, L.C.; Paredes, S.D.; Korkmaz, A.; Sainz, R.M.; Mayo, J.C.; Fuentes-Broto, L.; Reiter, R.J. The changing biological roles of melatonin during evolution: From an antioxidant to signals of darkness, sexual selection and fitness. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2010, 85, 607–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.-X.; Manchester, L.C.; Reiter, R.J.; Qi, W.-B.; Zhang, M.; Weintraub, S.T.; Cabrera, J.; Sainz, R.M.; Mayo, J.C. Identification of highly elevated levels of melatonin in bone marrow: Its origin and significance. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 1999, 1472, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Vico, A.; Calvo, J.R.; Abreu, P.; Lardone, P.J.; García-Mauriño, S.; Reiter, R.J.; Guerrero, J.M. Evidence of melatonin synthesis by human lymphocytes and its physiological significance: Possible role as intracrine, autocrine, and/or paracrine substance. FASEB J. 2004, 18, 537–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iuvone, P.M.; Tosini, G.; Pozdeyev, N.; Haque, R.; Klein, D.C.; Chaurasia, S.S. Circadian clocks, clock networks, arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferase, and melatonin in the retina. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2005, 24, 433–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.-J.; Zhuang, J.; Zhu, H.-Y.; Shen, Y.-X.; Tan, Z.-L.; Zhou, J.-N. Cultured rat cortical astrocytes synthesize melatonin: Absence of a diurnal rhythm. J. Pineal Res. 2007, 43, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naranjo, M.C.; Guerrero, J.M.; Rubio, A.; Lardone, P.J.; Carrillo-Vico, A.; Carrascosa-Salmoral, M.P.; Jiménez-Jorge, S.; Arellano, M.V.; Leal-Noval, S.R.; Leal, M.; et al. Melatonin biosynthesis in the thymus of humans and rats. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2007, 64, 781–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slominski, A.T.; Hardeland, R.; Zmijewski, M.A.; Slominski, R.M.; Reiter, R.J.; Paus, R. Melatonin: A Cutaneous Perspective on its Production, Metabolism, and Functions. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2018, 138, 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slominski, A.T.; Pisarchik, A.; Semak, I.; Sweatman, T.; Wortsman, J.; Szczesniewski, A.; Slugocki, G.; McNulty, J.; Kauser, S.; Tobin, D.J.; et al. Serotoninergic and melatoninergic systems are fully expressed in human skin. FASEB J. 2002, 16, 896–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slominski, A.; Tobin, D.J.; Zmijewski, M.A.; Wortsman, J.; Paus, R. Melatonin in the skin: Synthesis, metabolism and functions. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 19, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, R.J.; Tamura, H.; Tan, D.X.; Xu, X.-Y. Melatonin and the circadian system: Contributions to successful female reproduction. Fertil. Steril. 2014, 102, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.-M.; Tian, X.-Z.; Zhou, G.-B.; Wang, L.; Gao, C.; Zhu, S.-E.; Zeng, S.-M.; Tian, J.-H.; Liu, G.-S. Melatonin exists in porcine follicular fluid and improves in vitro maturation and parthenogenetic development of porcine oocytes. J. Pineal Res. 2009, 47, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Raey, M.; Geshi, M.; Somfai, T.; Kaneda, M.; Hirako, M.; Abdel-Ghaffar, A.E.; Sosa, G.A.; El-Roos, M.E.A.; Nagai, T. Evidence of melatonin synthesis in the cumulus oocyte complexes and its role in enhancing oocyte maturation in vitro in cattle. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2011, 78, 250–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaguchi, K.; Itoh, M.T.; Takahashi, N.; Tarumi, W.; Ishizuka, B. The rat oocyte synthesises melatonin. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2013, 25, 674–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegra, M.; Reiter, R.J.; Tan, D.-X.; Gentile, C.; Tesoriere, L.; Livrea, M.A. The chemistry of melatonin’s interaction with reactive species. J. Pineal Res. 2003, 34, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, C.; Mayo, J.C.; Sainz, R.M.; Antolin, I.; Herrera, F.; Martin, V.; Reiter, R.J. Regulation of antioxidant enzymes: A significant role for melatonin. J. Pineal Res. 2004, 36, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.-X.; Reiter, R.J.; Manchester, L.C.; Yan, M.-T.; El-Sawi, M.; Sainz, R.M.; Mayo, J.C.; Kohen, R.; Allegra, M.; Hardelan, R. Chemical and Physical Properties and Potential Mechanisms: Melatonin as a Broad Spectrum Antioxidant and Free Radical Scavenger. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2002, 2, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menendez-Pelaez, A.; Reiter, R.J. Distribution of melatonin in mammalian tissues: The relative importance of nuclear versus cytosolic localization. J. Pineal Res. 1993, 15, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, E.J.; Shida, C.S.; Biaggi, M.H.; Ito, A.S.; Lamy-Freund, M.T. How melatonin interacts with lipid bilayers: A study by fluorescence and ESR spectroscopies. FEBS Lett. 1997, 416, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, M.; Macías, M.; Escames, G.; León, J.; Acuña-Castroviejo, D. Melatonin but not vitamins C and E maintains glutathione homeostasis in t-butyl hydroperoxide-induced mitochondrial oxidative stress. FASEB J. 2000, 14, 1677–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venegas, C.; García, J.A.; Escames, G.; Ortiz, F.; López, A.; Doerrier, C.; García-Corzo, L.; López, L.C.; Reiter, R.J.; Acuña-Castroviejo, D. Extrapineal melatonin: Analysis of its subcellular distribution and daily fluctuations. J. Pineal Res. 2012, 52, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiter, R.J.; Ma, Q.; Sharma, R. Melatonin in Mitochondria: Mitigating Clear and Present Dangers. Physiology 2020, 35, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semak, I.; Naumova, M.; Korik, E.; Terekhovich, V.; Wortsman, A.J.; Slominski, A. A Novel Metabolic Pathway of Melatonin: Oxidation by Cytochrome c. Biochemistry. 2005, 44, 9300–9307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrabi, S.A.; Sayeed, I.; Siemen, D.; Wolf, G.; Horn, T.F.W. Direct inhibition of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore: A possible mechanism responsible for anti-apoptotic effects of melatonin. FASEB J. 2004, 18, 869–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janjetovic, Z.; Nahmias, Z.P.; Hanna, S.; Jarrett, S.G.; Kim, T.-K.; Reiter, R.J.; Slominski, A.T. Melatonin and its metabolites ameliorate ultraviolet B-induced damage in human epidermal keratinocytes. J. Pineal Res. 2014, 57, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slominski, A.T.; Zmijewski, M.A.; Semak, I.; Kim, T.-K.; Janjetovic, Z.; Slominski, R.M.; Zmijewski, J.W. Melatonin, mitochondria, and the skin. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2017, 74, 3913–3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleszczyński, K.; Zillikens, D.; Fischer, T.W. Melatonin enhances mitochondrial ATP synthesis, reduces reactive oxygen species formation, and mediates translocation of the nuclear erythroid 2-related factor 2 resulting in activation of phase-2 antioxidant enzymes (γ-GCS, HO-1, NQO1) in ultraviolet radiation-treated normal human epidermal keratinocytes (NHEK). J. Pineal Res. 2016, 61, 187–197. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, T.K.; Kleszczyński, K.; Janjetovic, Z.; Sweatman, T.; Lin, Z.; Li, W.; Reiter, R.J.; Fischer, T.W.; Slominski, A.T. Metabolism of melatonin and biological activity of intermediates of melatoninergic pathway in human skin cells. FASEB J. 2013, 27, 2742–2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slominski, A.T.; Kleszczyński, K.; Semak, I.; Janjetovic, Z.; Żmijewski, M.A.; Kim, T.-K.; Slominski, R.M.; Reiter, R.J.; Fischer, T.W. Local Melatoninergic System as the Protector of Skin Integrity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 17705–17732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slominski, R.M.; Reiter, R.J.; Schlabritz-Loutsevitch, N.; Ostrom, R.S.; Slominski, A.T. Melatonin membrane receptors in peripheral tissues: Distribution and functions. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2012, 351, 152–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilska, B.; Schedel, F.; Piotrowska, A.; Stefan, J.; Zmijewski, M.; Pyza, E.; Reiter, R.J.; Steinbrink, K.; Slominski, A.T.; Tulic, M.K.; et al. Mitochondrial function is controlled by melatonin and its metabolites in vitro in human melanoma cells. J. Pineal Res. 2021, 70, e12728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleszczyński, K.; Bilska, B.; Stegemann, A.; Flis, D.J.; Ziolkowski, W.; Pyza, E.; Luger, T.A.; Reiter, R.J.; Böhm, M.; Slominski, A.T. Melatonin and Its Metabolites Ameliorate UVR-Induced Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress in Human MNT-1 Melanoma Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleszczyński, K.; Kim, T.; Bilska, B.; Sarna, M.; Mokrzynski, K.; Stegemann, A.; Pyza, E.; Reiter, R.J.; Steinbrink, K.; Böhm, M.; et al. Melatonin exerts oncostatic capacity and decreases melanogenesis in human MNT-1 melanoma cells. J. Pineal Res. 2019, 67, e12610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lalanne, S.; Fougerou-Leurent, C.; Anderson, G.M.; Schroder, C.M.; Nir, T.; Chokron, S.; Delorme, R.; Claustrat, B.; Bellissant, E.; Kermarrec, S.; et al. Melatonin: From Pharmacokinetics to Clinical Use in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wan, J.; Liu, A.; Sun, J. Melatonin regulates Aβ production/clearance balance and Aβ neurotoxicity: A potential therapeutic molecule for Alzheimer’s disease. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 132, 110887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talib, W.H.; Alsayed, A.R.; Abuawad, A.; Daoud, S.; Mahmod, A.I. Melatonin in Cancer Treatment: Current Knowledge and Future Opportunities. Molecules 2021, 26, 2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, R.J.; Tan, D.X.; Galano, A. Melatonin: Exceeding Expectations. Physiology 2014, 29, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tordjman, S.; Chokron, S.; Delorme, R.; Charrier, A.; Bellissant, E.; Jaafari, N.; Fougerou, C. Melatonin: Pharmacology, Functions and Therapeutic Benefits. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2017, 15, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, R.J.; Mayo, J.C.; Tan, D.-X.; Sainz, R.M.; Alatorre-Jimenez, M.; Qin, L. Melatonin as an antioxidant: Under promises but over delivers. J. Pineal Res. 2016, 61, 253–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, R.J.; Paredes, S.D.; Manchester, L.C.; Tan, D.-X. Reducing oxidative/nitrosative stress: A newly-discovered genre for melatonin. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2009, 44, 175–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.-H.; Feenstra, M.G.P.; Zhou, J.-N.; Liu, R.-Y.; Toranõ, J.S.; van Kan, H.J.M.; Fischer, D.F.; Ravid, R.; Swaab, D.F. Molecular Changes Underlying Reduced Pineal Melatonin Levels in Alzheimer Disease: Alterations in Preclinical and Clinical Stages. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003, 88, 5898–5906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-H.; Swaab, D.F. The human pineal gland and melatonin in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. J. Pineal Res. 2005, 38, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soriano, J.L.; Calpena, A.C.; Rincon, M.; Perez, N.; Halbaut, L.; Rodriguez-Lagunas, M.J.; Clares, B. Melatonin nanogel promotes skin healing response in burn wounds of rats. Nanomedicine 2020, 15, 2133–2147. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.; Tong, C.; Yang, J.; Cong, P.; Liu, Y.; Shi, X.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Zou, R.; Xiao, K.; et al. Injectable melatonin-loaded carboxymethyl chitosan (CMCS)-based hydrogel accelerates wound healing by reducing inflammation and promoting angiogenesis and collagen deposition. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 63, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Han, Q.; Zhao, X.; Song, J.; Cheng, Y.; Fang, Z.; Ouyang, Y.; Yuan, W.-E.; Fan, C. 3D melatonin nerve scaffold reduces oxidative stress and inflammation and increases autophagy in peripheral nerve regeneration. J. Pineal Res. 2018, 65, e12516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chen, X.; Qian, Y.; Tang, H.; Song, J.; Qu, X.; Yue, B.; Yuan, W.E. Melatonin-Based and Biomimetic Scaffold as Muscle–ECM Implant for Guiding Myogenic Differentiation of Volumetric Muscle Loss. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 2002378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Diao, J.; Zhao, N.; Shi, X.; Wang, Y. Melatonin decorated 3D-printed beta-tricalcium phosphate scaffolds promoting bone regeneration in a rat calvarial defect model. J. Mater. Chem. B 2019, 7, 3250–3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjunath, K.S.; Subha, K.R.; Jaison, D.; Sridhar, K.; Kasthuri, N.; Gopinath, V.; Sivaperumal, P.; Shantanu, P.S. Melatonin delivery from PCL scaffold enhances glycosaminoglycans deposition in human chondrocytes—Bioactive scaffold model for cartilage regeneration. Proc. Biochem. 2020, 99, 36–47. [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarek, B.; Sionkowska, A.; Monteiro, F.J.; Carvalho, A.; Łukowicz, K.; Osyczka, A.M. Characterization of gelatin and chitosan scaffolds cross-linked by addition of dialdehyde starch. Biomed. Mater. 2017, 13, 015016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacEwan, M.R.; MacEwan, S.; Kovacs, T.R.; Batts, J. What Makes the Optimal Wound Healing Material? A Review of Current Science and Introduction of a Synthetic Nanofabricated Wound Care Scaffold. Cureus 2017, 9, e1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, L.L.; Resende, C.X.; Tavares, D.S.; Soares, G.A. Cytocompatibility of chitosan and collagen-chitosan scaffolds for tissue engineering. Polimeros 2011, 21, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prus, W.; Kozłowska, J. The influence of collagen from various sources on skin parameters. Eng. Biomater. 2018, 21, 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarek, B.; Mazur, O. Collagen-Based Materials Modified by Phenolic Acids—A Review. Materials 2020, 13, 3641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sionkowska, A.; Michalska, M.; Walczak, M. Preparation and characterization of silk fibroin/collagen sponge with nanohydroxyapatite. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 2016, 640, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez-Portalatin, N.; Alfonso-Garcia, A.; Liu, J.C.; Marcu, L.; Panitch, A. Physical, Biomechanical, and Optical Characterization of Collagen and Elastin Blend Hydrogels. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 48, 2924–2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, J.; Stowers, R.; Nam, S.; Xia, Y.; Chaudhuri, O. Stress relaxing hyaluronic acid-collagen hydrogels promote cell spreading, fiber remodeling, and focal adhesion formation in 3D cell culture. Biomaterials 2018, 154, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagha, A.; Nourallah, A.; Hariri, S. Characterization of dexamethasone loaded collagen-chitosan sponge and in vitro release study. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 55, 101449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Lu, Z.; Wu, H.; Li, W.; Zheng, L.; Zhao, J. Collagen-alginate as bioink for three-dimensional (3D) cell printing based cartilage tissue engineering. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2018, 83, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, B.; Nadolna, K.; Owczarek, A.; Mazur, O.; Sionkowska, A.; Łukowicz, K.; Vishnu, J.; Manivasagam, G.; Osyczka, A.M. Properties of scaffolds based on chitosan and collagen with bioglass 45S5. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2020, 14, 830–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, B.; Mazur, O.; Miłek, O.; Michalska-Sionkowska, M.; Osyczka, A.M.; Kleszczyński, K. Development of tannic acid-enriched materials modified by poly(ethylene glycol) for potential applications as wound dressing. Prog. Biomater. 2020, 9, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgado, P.I.; Aguiar-Ricardo, A.; Correia, I.J. Asymmetric membranes as ideal wound dressings: An overview on production methods, structure, properties and performance relationship. J. Membr. Sci. 2015, 490, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andonegi, M.; Heras, K.L.; Santos-Vizcaíno, E.; Igartua, M.; Hernandez, R.M.; de la Caba, K.; Guerrero, P. Structure-properties relationship of chitosan/collagen films with potential for biomedical applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 237, 116159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correa, V.L.R.; Martins, J.A.; de Souza, T.R.; Rincon, G.D.C.N.; Miguel, M.P.; de Menezes, L.B.; Amaral, A.C. Melatonin loaded lecithin-chitosan nanoparticles improved the wound healing in diabetic rats. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 162, 1465–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.-K.; Lin, Z.; Li, W.; Reiter, R.J.; Slominski, A.T. N 1-Acetyl-5-Methoxykynuramine (AMK) Is Produced in the Human Epidermis and Shows Antiproliferative Effects. Endocrinology 2015, 156, 1630–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slominski, A.; Semak, I.; Pisarchik, A.; Sweatman, T.; Szczesniewski, A.; Wortsman, J. Conversion ofL-tryptophan to serotonin and melatonin in human melanoma cells. FEBS Lett. 2002, 511, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafner, A.; Lovrić, J.; Voinovich, D.; Filipović-Grčić, J. Melatonin-loaded lecithin/chitosan nanoparticles: Physicochemical characterisation and permeability through Caco-2 cell monolayers. Int. J. Pharm. 2009, 381, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirmajidi, T.; Chogan, F.; Rezayan, A.H.; Sharifi, A.M. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of a nanofiber wound dressing loaded with melatonin. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 596, 120213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romić, M.D.; Sušac, A.; Lovrić, J.; Cetina-Čižmek, B.; Filipović-Grčić, J.; Hafner, A. Evaluation of stability and in vitro wound healing potential of melatonin loaded (lipid enriched) chitosan based microspheres. Acta Pharm. 2019, 69, 635–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozlowska, J.; Kaczmarkiewicz, A. Collagen matrices containing poly(vinyl alcohol) microcapsules with retinyl palmitat—Structure, stability, mechanical and swelling properties. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2019, 161, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sionkowska, A.; Kozłowska, J. Properties and modification of porous 3-D collagen/hydroxyapatite composites. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2013, 52, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.G.; Leapman, R.D.; Zhang, G.; Lai, B.; Valencia, J.C.; Cardarelli, C.O.; Vieira, W.D.; Hearing, V.J.; Gottesman, M.M. Influence of Melanosome Dynamics on Melanoma Drug Sensitivity. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2009, 101, 1259–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmichael, J.; DeGraff, W.G.; Gazdar, A.F.; Minna, J.D.; Mitchell, J.B. Evaluation of a tetrazolium-based semiautomated colorimetric assay: Assessment of chemosensitivity testing. Cancer Res. 1987, 47, 936–942. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Specimen | T1 [°C] | T2 [°C] | T3 [°C] |

|---|---|---|---|

| CTS/Coll (fish) | 61.23 | 190.43 | 287.51 |

| +0.001 g melatonin | 53.64 | 188.70 | 286.27 |

| +0.01 g melatonin | 58.42 | 175.31 | 289.51 |

| +0.1 g melatonin | 57.73 | n.o. | 289.57 |

| CTS/Coll (rat) | 60.19 | 175.54 | 292.28 |

| +0.001 g melatonin | 52.03 | 169.96 | 293.92 |

| +0.01 g melatonin | 58.08 | 171.76 | 291.45 |

| +0.1 g melatonin | n.o. | n.o. | 280.83 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kaczmarek-Szczepańska, B.; Ostrowska, J.; Kozłowska, J.; Szota, Z.; Brożyna, A.A.; Dreier, R.; Reiter, R.J.; Slominski, A.T.; Steinbrink, K.; Kleszczyński, K. Evaluation of Polymeric Matrix Loaded with Melatonin for Wound Dressing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5658. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22115658

Kaczmarek-Szczepańska B, Ostrowska J, Kozłowska J, Szota Z, Brożyna AA, Dreier R, Reiter RJ, Slominski AT, Steinbrink K, Kleszczyński K. Evaluation of Polymeric Matrix Loaded with Melatonin for Wound Dressing. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021; 22(11):5658. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22115658

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaczmarek-Szczepańska, Beata, Justyna Ostrowska, Justyna Kozłowska, Zofia Szota, Anna A. Brożyna, Rita Dreier, Russel J. Reiter, Andrzej T. Slominski, Kerstin Steinbrink, and Konrad Kleszczyński. 2021. "Evaluation of Polymeric Matrix Loaded with Melatonin for Wound Dressing" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22, no. 11: 5658. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22115658

APA StyleKaczmarek-Szczepańska, B., Ostrowska, J., Kozłowska, J., Szota, Z., Brożyna, A. A., Dreier, R., Reiter, R. J., Slominski, A. T., Steinbrink, K., & Kleszczyński, K. (2021). Evaluation of Polymeric Matrix Loaded with Melatonin for Wound Dressing. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(11), 5658. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22115658