Abstract

For a long time, Cannabis sativa has been used for therapeutic and industrial purposes. Due to its increasing demand in medicine, recreation, and industry, there is a dire need to apply new biotechnological tools to introduce new genotypes with desirable traits and enhanced secondary metabolite production. Micropropagation, conservation, cell suspension culture, hairy root culture, polyploidy manipulation, and Agrobacterium-mediated gene transformation have been studied and used in cannabis. However, some obstacles such as the low rate of transgenic plant regeneration and low efficiency of secondary metabolite production in hairy root culture and cell suspension culture have restricted the application of these approaches in cannabis. In the current review, in vitro culture and genetic engineering methods in cannabis along with other promising techniques such as morphogenic genes, new computational approaches, clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR), CRISPR/Cas9-equipped Agrobacterium-mediated genome editing, and hairy root culture, that can help improve gene transformation and plant regeneration, as well as enhance secondary metabolite production, have been highlighted and discussed.

1. Introduction

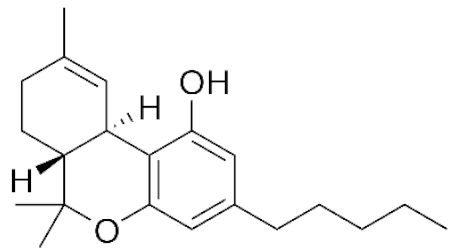

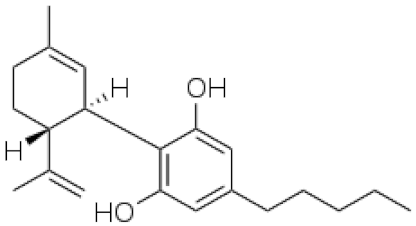

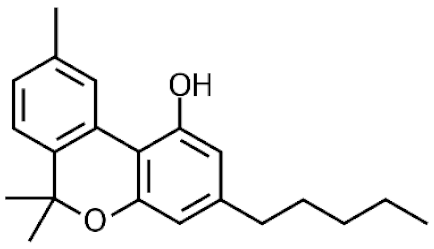

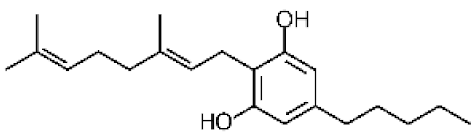

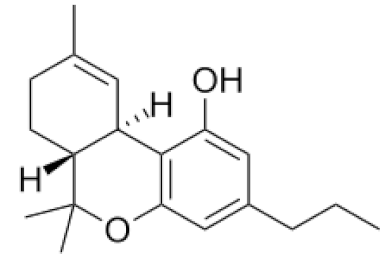

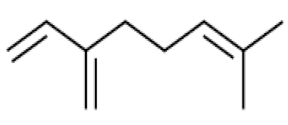

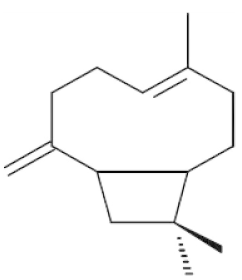

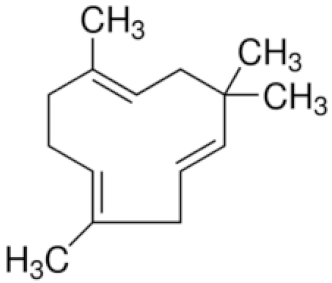

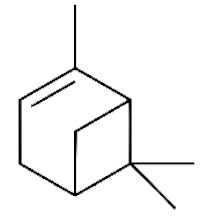

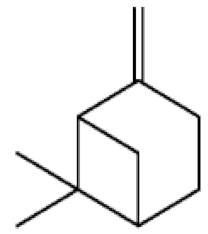

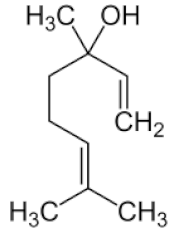

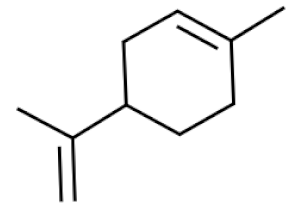

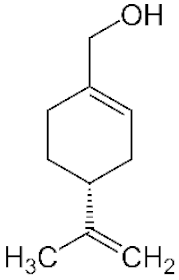

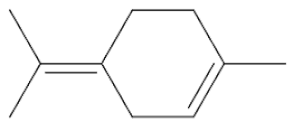

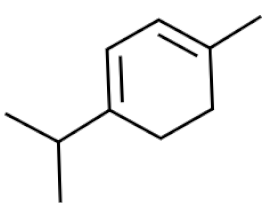

Cannabis sativa L. is a high-demand plant with a long history of medicinal, industrial, recreational, and agricultural uses [1,2]. Cannabis can be categorized based on taxonomic relationships or chemotype but is often divided into two main groups and regulated based on the level of psychoactive cannabinoids that are produced. In most countries, anything below 0.3% Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is classified as hemp and plants that produce 0.3% or greater are categorized as marijuana [3]. To date, more than 560 secondary metabolites are known in cannabis [1,2]. Although cannabinoids and terpenes are the predominant biomolecules in cannabis, phenolic compounds and flavonoids have also been detected. Currently, more than 115 cannabinoids, isoprenylated polyketides, have been identified in cannabis, which are mainly produced in glandular trichomes of female flowers. Cannabidiol (CBD), THC, and cannabichromene (CBC) can be considered as the major cannabinoids in the crop, but new genetics that express other cannabinoids such as cannabigerol (CBG) are now emerging [4].

During the last decade, the industrial properties of cannabis (Figure 1) for applications in textiles, paper, building materials, cosmetics, and foods [5,6,7], as well as pharmacological properties (Table 1) such as the palliation of chronic pains associated with cancer, neutralizing the adverse impacts of chemotherapy with cytostatic drugs, eating disorders related to anorexia and AIDS, inflammatory diseases, epilepsy, and anti-spastic activity in Tourette’s syndrome or sclerosis multiplex cases have been broadly studied and supported [5,8].

Figure 1.

Some industrial properties of Cannabis.

Table 1.

Some pharmacological properties of Cannabis.

While cannabinoids and cannabinoid-containing products are a new market, they are exponentially growing and a recent market report estimated that the global value of CBD alone will reach 16 billion by 2025 [9]. As the demand for these products increases, there is a pressing need to develop improved genetics and cultivation techniques [10,11].

Conventional plant breeding involves directed crosses of parent plants with desirable characteristics, population evaluation, selection, and fixing desired traits (selfing). In cannabis, these are difficult criteria to meet due to plant biology (e.g., dioecy) and regulations. Cannabis plants are predominantly dioecious but selfing can be achieved through the induction of male flowers on female plants to produce feminized seeds [40]. These limitations in cannabis make conventional breeding methods time-consuming, costly, and laborious. The composition and content of cannabis secondary metabolites, in particular cannabinoids and terpenes, is also greatly related to various factors such as genotypes, age of plants, sex, developmental phase, growth and environmental conditions, harvesting time, storage conditions, and methods of cultivation [3,5].

For most crops with this economic importance, biotechnological tools (i.e., genetic engineering methods including transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) [41], zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs) [42], and clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) [43] are well developed and have been implemented into breeding programs for decades. However, due to the long history of the prohibition of recreational/drug type cannabis, along with the strict regulation and lower market value of hemp, these tools are rudimentary, and many common techniques used in other crops have yet to be applied to cannabis [44]. With recent shifts towards the legalization of cannabis for medicinal and recreational purposes in many jurisdictions and the establishment of a legal market for cannabinoids, cannabis production is becoming a large-scale enterprise similar to other major crops [3]. Along with the emergence of legal commercial producers, the need for modern technologies for genetic improvement is steadily increasing. While biotechnology of cannabis is still relatively new and unrefined, with the advent of affordable large-scale sequencing technologies (i.e., next-generation sequencing (NGS)) and the increasing body of candidate genes for traits of interest, we argue that it is time for a paradigm shift toward improving cannabis genetics through genetic engineering.

Recently, whole genomic and transcriptomic information of cannabis has been obtained using NGS methods [1]. Cannabis NGS information can be applied for robust molecular tools such as DNA barcoding to detect genetic diversity, sex determination, and chemotype inheritance [5]. Moreover, these data can be merged with metabolomics and proteomics to identify unknown secondary metabolites of cannabis [3]. More rapid and accurate transcriptome analysis to detect key enzymes and genes in the biosynthetic pathway of secondary metabolites, mapping of unknown and wild populations using restriction site-associated DNA sequencing (e.g., genotyping by sequencing (GBS)) [45], and interpretation of targeting-induced local lesions in genomes (TILLING) populations are applicable based on the NGS information in cannabis [3,5]. Above all, NGS-derived data facilitate the introduction of genetic engineering methods in cannabis [46].

In vitro tissue culture techniques (e.g., callus and cell culture, de novo regeneration, hairy root culture) are the basis of micropropagation and breeding in cannabis [10,47]. In vitro culture methods coupled with genetic engineering techniques (e.g., Agrobacterium-mediated gene transformation and genome editing) as well as polyploidy induction offer opportunities for producing new genotypes and manipulating secondary metabolite production in cannabis [46]. Although conventional genetic engineering tools (e.g., Agrobacterium-mediated gene transformation and A. rhizogenes-mediated hairy root cultures) can alter the production of some secondary metabolites, it seems that the CRISPR/Cas9 system has more potential than these tools to introduce new germplasms and enhance secondary metabolite production in cannabis in a faster manner [10,47]. Therefore, biotechnological methods can be employed in order to develop improved genetics to help satisfy the demands of producers and consumers.

In the current review, all applied in vitro propagation and genetic engineering methods in cannabis along with other possibly applicable techniques such as designing new culture media, machine learning algorithms, and morphogenic genes that can help cannabis propagation and improvements, as well as enhance secondary metabolite yield, have been highlighted and discussed. The principles, benefits, weaknesses, and concerns of different methods have also been presented.

2. In vitro Culture in Cannabis

In vitro culture is the basis of most biotechnological tools [10,47]. Many methods such as micropropagation, in situ and ex situ conservation, cell culture, Agrobacterium-mediated gene transformation, and polyploidy induction completely depend on in vitro culture techniques [48]. Moreover, plant cell and tissue culture is also a robust method for assessing the secondary metabolite production and endogenous phytohormone metabolism signaling in many plants [46]. Indeed, in vitro culture techniques are useful to propagate plants, but also to produce engineered biomolecules and initiate synthetic biology approaches [10,47].

Callus and cell suspension cultures were one of the main objectives of early in vitro culture in cannabis. The first attempts of callus cultures to produce cannabinoids were performed by Hemphill et al. [49], Loh et al. [50], and Braemer and Paris [51] and led to the conversion of olivetol and CBD to cannabielsoin. However, unstable and inadequate levels of cannabinoid production were achieved. Furthermore, cannabinoids could not be synthesized without adding exogenous cannabigerolic acid (CBGA) as a precursor to the callogenesis medium. Further studies [52,53] revealed that cannabinoids could not be produced even from an inflorescence-derived callus. In another study, Flores-Sanchez et al. [54] used various biotic (Pythium aphanidermatum and Botrytis cinerea) and abiotic (methyl jasmonate, salicylic acid, jasmonic acid, UV-B, AgNO3, NiSO4·6H2O, and CoCl2·6H2O) elicitors in cannabis cell suspension cultures; however, improved cannabinoid production was not obtained.

These results suggest that the biosynthesis of cannabinoids is completely linked to tissue and organ-specific development and complex gene regulatory networks that can only be efficiently produced by trichomes, which are most abundant in differentiated floral tissues. However, cell suspension cultures may still be promising for producing other secondary metabolites such as terpenes, polyphenols, lignans, and alkaloids [7,10]. For instance, Gabotti et al. [55] reported that the activity and expression of tyrosine aminotransferase (TAT) and phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) increased in cannabis cell suspension cultures using a methyl jasmonate elicitor in combination with tyrosine precursor. Some aromatic compounds such as 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate (4-HPP) were also identified. This is relevant as highly biologically active flavonoids have been isolated from cannabis [55].

Hairy root culture is another application of in vitro methods that have been used for secondary metabolite production in many species and investigated in cannabis [10]. Affordable and high production of secondary metabolites, high genetic stability, and rapid accumulation and growth of biomass are only some of the merits of hairy root cultures [46]. A larger scale and more profitable process can also be achieved by the cultivation of hairy roots in bioreactors [56]. Sirikantaramas et al. [57] isolated Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinolic acid synthase (THCAS) from cannabis leaves and cloned its cDNA. Then, the cDNA was transformed in tobacco hairy roots using A. rhizogenes. Although THCA was produced through THCAS expression and by adding CBGA, the THCA production rate was low. Farag and Kayser [58] reported 1 µg THCA g−1 dry weight (DW), 1.7 µg CBDA g−1 DW, 1.6 µg CBGA g−1 DW, and 2 µg cannabinoids g−1 DW obtained from adventitious roots from callus cultures. Given that floral tissues from whole plants can produce over 20% THC w/dw, these levels are very low [58]. These results are not surprising given that cannabinoids are generally produced in trichomes, which are not found in root tissues and this approach is likely not suitable for cannabinoids production. Generally, many compounds require differentiated tissues for efficient production. Moher et al. [59] demonstrated that in vitro plants respond to photoperiod and that they develop “normal” looking flowers. While the cannabinoid content of these flowers has not been examined, it is likely that they produce much higher levels than would be observed in undifferentiated tissues, or roots. Therefore, this could be an alternative approach to producing cannabinoids in vitro but it has yet to be explored.

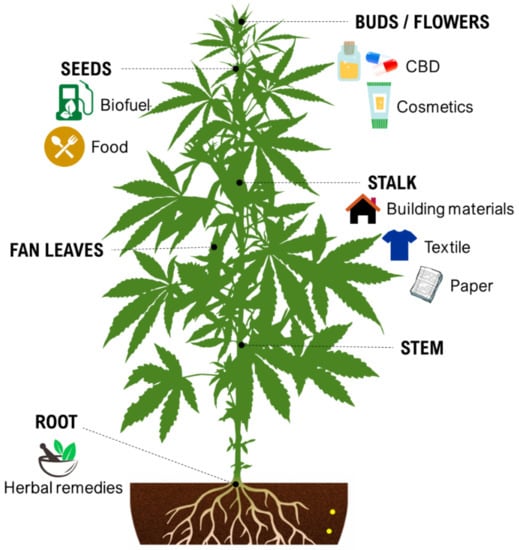

Micropropagation is the first and foremost application of in vitro culture in cannabis [10,47,60,61]. While micropropagation for applications in genetic preservation or propagation are generally achieved through shoot proliferation from existing meristems, many applications in biotechnology require the establishment of de novo regeneration in which plants are produced from non-meristematic tissues. Somatic embryogenesis and organogenesis through either direct or indirect regeneration are the most important platforms for developing regeneration protocols (Figure 2). Although somatic embryogenesis is considered the ideal approach since they regenerate from single cells and reduce chimerism in transformed plants [46], it has been rarely achieved in cannabis. Table 2 represents callogenesis and organogenesis studies in cannabis to date. As can be seen in Table 2, most studies have investigated the effects of plant growth regulators (PGRs) and type of explants and genotypes on micropropagation of cannabis. However, there are many factors (e.g., medium composition and incubation conditions, discussed in the following sections) that affect cannabis micropropagation. Therefore, it is necessary to study these factors for obtaining high-frequency protocols.

Figure 2.

The schematic diagram of plant tissue culture procedures.

Table 2.

In vitro regeneration studies in cannabis.

2.1. Strategies to Improve In Vitro Culture Procedures

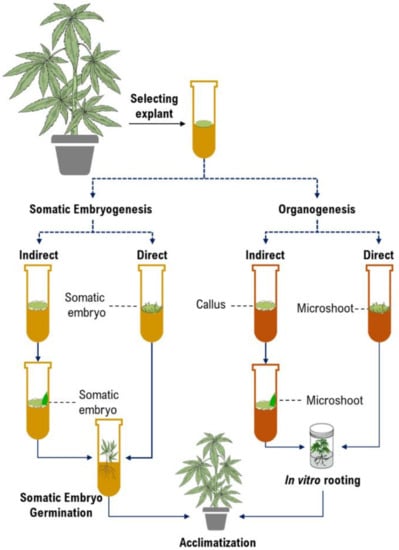

Despite advances in in vitro cell and tissue culture of cannabis in recent years, efficient cannabis regeneration remains one of the main obstacles to applying biotechnology for cannabis improvement and the species is generally considered to be relatively recalcitrant [94]. Genotypes, type and concentration of PGRs, size, age, and type of explant, gelling agent, carbohydrate sources, type and concentration of macro- and micro-nutrients, type and concentration of vitamins, type and concentration of additives (casein hydrolysate, nanoparticles, phloroglucinol, activated charcoal, etc.), pH of the medium, type and volume of the vessels, volume of the medium per culture vessels, and culture conditions (intensity and quality of the light, temperature, photoperiod, and light source) are the most important factors affecting in vitro culture systems [94,95] (Figure 3). However, most studies have investigated the effects of PGRs and the type of explants and genotypes on cannabis micropropagation and little information on many other factors is available. Therefore, studying other factors may result in high-frequency regeneration systems or even obtaining somatic embryogenesis and haploid production protocols. In this section, several promising strategies for improving in vitro culture protocols have been highlighted based on the mentioned factors, new computational methodologies such as machine learning algorithms, and new genetic engineering methods.

Figure 3.

The schematic diagram of factors affecting in vitro culture procedures.

Although a few studies [78,81] have tested newer PGRs and additives such as 6-benzylamino-9-(tetrahydroxypyranyl) purin (BAP9THP) and meta-topolin (mT) for cannabis micropropagation, there are still some promising PGRs and additives, such as polyamines, brassinosteroids, nano-particles, and nitric oxide (NO) that have not been used for developing cannabis micropropagation protocols. NO, a messenger molecule regulating plant development such as flowering, germination, fruit ripening, and organ senescence, has been recently characterized as a phytohormone [96,97]. It was shown that NO can be experimentally applied in the media as sodium nitroprusside (SNP), which eliminates the difficulty in the application of NO in its gaseous form [98]. Several studies showed that NO is one of the main signaling pathways in in vitro organogenesis and somatic embryogenesis [96,99]. Therefore, the application of SNP may pave the way for obtaining somatic embryogenesis or improving organogenesis protocols in cannabis. Recent studies showed that adding nanoparticles to the culture media improves callogenesis, organogenesis, somatic embryogenesis, and rhizogenesis by inhibiting the production of ROS and ethylene and altering gene expression and antioxidant enzyme activities [100,101,102,103,104,105]. Thus, the application of nanoparticles can be investigated as a promising approach to enhance the in vitro regeneration capacity of cannabis.

The source of carbohydrates is another factor affecting in vitro culture systems. The effect of sucrose, glucose, and fructose as the most important carbohydrates have been widely studied in in vitro morphogenic responses of different plants [106]. While sucrose has resulted in the maximum in vitro organogenesis and embryogenesis in some plants (e.g., Agave angustifolia [107], Sapindus trifoliatus [108], and Pinus koraiensis [109]), other plants (e.g., Vitis Vinifera [110], Brassica napus [111], and Chrysanthemum ×grandiflorum [112]) had better in vitro morphogenic responses to glucose and fructose [106]. Therefore, it is essential to study the effect of different carbohydrate sources on cannabis micropropagation.

The source, intensity, and quality of light play a pivotal role in in vitro organogenesis and embryogenesis [112,113]. The usefulness of light emitting diodes (LEDs) in different micropropagation procedures has been widely demonstrated [114,115]. LEDs provide an appropriate light spectrum and therefore can be considered promising light sources for improving micropropagation studies [113,116]. However, it has been shown that each step of in vitro culture needs a particular light spectrum [113]. For instance, there is an ongoing debate on using red or blue light. However, several studies showed that the red light is better than blue light for somatic embryogenesis [112,117].

Many cannabis micropropagation studies [65,66,67,69,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,83] used MS [118] as a basal medium while the composition of MS medium was initially defined for the analysis of tissue ashes of tobacco. Several factors related to the basal medium, such as macro- and micro-elements and vitamins, are known as major factors that are affected in vitro morphogenesis in different species or plant organs [119]. Recently, Page et al. [92] reported that plants cultivated on MS medium displayed a number of physiological defects and that DKW [120] basal salts were much better. Additionally, they reported that DKW basal salts also supported greater callus growth from leaf explants. Together, this suggests that MS salts are sub-optimal for shoot and callus growth in cannabis, but the authors also stated that plants cultured on DKW basal salts still displayed some symptoms and further improvement is likely possible and they did not report regeneration so it is unknown if DKW is suitable for that application.

The challenges in designing a de novo medium and optimizing these myriad factors for specific purposes are expensive and time consuming due to the large number of variables and their interactions with one another. Therefore, new approaches such as new computational methodologies (i.e., machine learning algorithms) are needed to design regeneration protocols. Artificial intelligence models and optimization algorithms provide a complementary outlook for calibrating in vitro protocols, as these algorithms find optimal solutions in terms of genotype, explant source, plant growth regulators, medium composition, and incubation conditions, without the requirement for large-scale, costly, time-consuming, and tedious experimental trials [95,121]. Recently, different machine learning algorithms have been successfully used for predicting and optimizing different in vitro culture processes such as shoot proliferation [122,123,124,125,126], callogenesis [127,128], somatic embryogenesis [129], secondary metabolite production [130,131,132], and gene transformation [133]. Hence, the combination of the experimental approach and machine learning algorithms can be considered a powerful and reliable method to develop a specific protocol for cannabis.

It has been shown that micropropagation after mechanical wounding induced by brushing tissue surfaces has been significantly increased [134]. Although there are no reports regarding the effect of wounding on cannabis micropropagation, from our observations callusing has generally initialed at wound sites and tissue wounding may be a promising approach to improve plant regeneration in cannabis. Three consecutive stages improve in vitro organogenesis by tissue wounding: (i) organogenesis is stimulated by some signals related to tissue damages, (ii) subsequently, endogenous phytohormones are accumulated, which results in (iii) cell fate transition [134].

Thin cell layer culture can be considered as another promising approach that can be used in cannabis micropropagation [135]. Although this method has been used in different recalcitrant plants such as Hedychium coronarium [136], Withania coagulans [135], and Agave fourcroydes [137], there is no report of the application of thin cell layer culture in cannabis. In this method, a thin layer of tissue as the explant is selected, which causes close contact between wounded cells and medium composition and finally leads to improvement of regeneration [135].

Bioreactors (e.g., continuous immersion and temporary immersion) can be considered as useful tools for cannabis micropropagation and for studying plant development [138]. The use of these devices can help overcome the recalcitrance of cannabis genotypes to proliferation, rooting, and acclimation. In addition, they can also be used to reduce the cost of large-scale propagation. The number of cannabis plants cultured in bioreactors is steadily increased, and frequently the physiological state of plant propagules improves with these systems of culture, which also facilitate photoautotrophic propagation.

The use of morphogenic genes is another strategy that may help alleviate the bottlenecks in cannabis regeneration. This strategy has been extensively discussed in section “4.2. Strategies to Improve Gene Transformation Efficiency”.

Protoplast culture can be considered a powerful method for many purposes such as plant regeneration, functional genetic analyses, genome editing, and studying cell processes (e.g., membrane function, cell structure, and hormonal signalization) [139,140]. The development of reproducible and stable protoplast isolation is one of the most important prerequisites for the success of protoplast-based technology. Although there are a few studies about protoplast isolation in cannabis (Table 3), there is no report regarding protoplast-mediated plant regeneration.

Table 3.

Protoplast isolation studies in Cannabis.

Beard et al. [141] showed protoplast isolation from the mesophyll of young, not fully expanded leaves of in vitro grown plantlets of C. sativa var. Cherry x Otto II: Sweetened. The authors reported that an enzymolysis solution composed of 0.3% w/v Macerozyme R-10, 20 mM MES (2-(N-morpholino) ethanesulfonic acid), 1.25% w/v Cellulase R-10, 0.4 M mannitol, 0.1% w/v bovine serum albumin, 10 mM calcium chloride, 20 mM potassium chloride, and 0.075% w/v Pectolyase Y23, adjusted to pH 5.7 and heated to 55 °C for 10 min, resulted in the maximum number of protoplasts (2.27 × 106 protoplasts per gram of leaf segments). Lazič [142] showed protoplast isolation from etiolated hypocotyls and the mesophyll of leaf cells of cannabis. The author also reported that an enzyme solution composed of 0.4% Macerozyme R–10 and 1.5% Cellulase Onozuka R-10 resulted in the maximum number of protoplasts from leaves whereas the highest number of protoplasts from etiolated hypocotyls was achieved from enzyme solution supplemented with 0.1% Macerozyme R-10 and 1% Cellulase Onozuka R-10. In another study, cannabis protoplasts were isolated using a digestion solution supplemented with 88 mM sucrose, 0.4 M mannitol, 1% (w/v) Cellulase Onozuka R-10, 0.1% (w/v) pectolyase Y-23, and 0.2% (w/v) Macerozyme R-10 at 30 °C for 4 h with gentle agitation [143].

Cannabis is a dioecious species, with separate male and female plants, and the most economically important product is unfertilized, seedless, female flowers [1]. Some of the challenges that result from these factors include producers not being able to have pollen-producing plants in their production facility, plants must be unfertilized for accurate phenotyping, which complicates breeding strategies, and it is difficult to self-pollenate plants to produce inbred lines for F1 hybrid seed production [48]. To address these challenges, in vitro techniques for the production of homozygous double haploids for F1 hybrid production can be considered as a robust solution [128]. In vitro haploid production consists of different methods such as wide hybridization-chromosome elimination, parthenogenesis, gynogenesis, and androgenesis [144]. Although there are no reports regarding haploid production in cannabis, it seems that haploid production protocols are needed for further genetic engineering studies. Recently, knockdown and/or knockout of the centromere-specific histone H3 (CENH3) gene, which connects spindle microtubules to chromosome centromere regions, provides a robust tool for producing haploid plants [145,146]. For instance, Wang et al. [145] and Kelliher et al. [146] successfully used the CRISPR/Cas9 system for the knockout of the CENH3 gene in maize genotypes to produce haploid inducer lines. It seems that such methodologies are very useful for haploid production in cannabis [147]; however, it is vital to develop stable gene transformation and plant regeneration systems before this can be done.

A combination of polyploidy induction and CRISPR/Cas9-equipped Agrobacterium rhizogenes-mediated hairy root culture can be considered as a robust strategy for increasing secondary metabolites production and changing the chemical profile [46]. This strategy has been recently applied for the knockout of the SmCPS1, an important gene in the tanshinone biosynthesis pathway [148] and SmRAS, a key gene in rosmarinic acid biosynthesis, [149] in Salvia miltiorrhiza, as well as DzFPS, a key gene in farnesyl pyrophosphate biosynthesis, in Dioscorea zingiberensis [150]. It seems that this strategy can be used to overcome the problems in hairy root culture of cannabis.

2.2. Somaclonal Variation

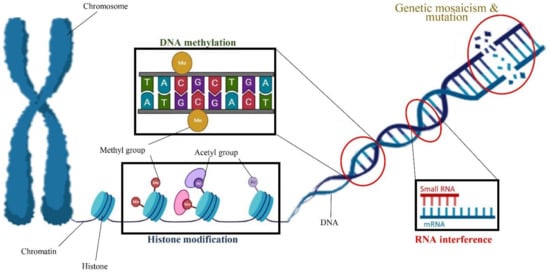

Most previous cannabis tissue culture studies have focused on optimizing culture conditions to increase the cannabis micropropagation rate. However, the optimal condition for in vitro propagation may not be optimal to preserve the genetic integrity of the regenerated genotype [151]. Indeed, in vitro conditions such as medium composition, PGRs, high humidity, the number of subcultures, length of the culture period, temperature, light quality, and light intensity can eventually result in several developmental and physiological aberrations of the micropropagated plants [60]. The term “somaclonal variation” refers to any phenotypic variation detected among micropropagated plants [151]. Somaclonal variation is created by either chromosome mosaics and spontaneous mutation or epigenetic regulations such as histone modification (e.g., histone methylation and histone acetylation), DNA methylation, and RNA interference [151,152] (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

A schematic view of factors involved in somaclonal variation including genetic mosaicism and mutation as well as epigenetic regulations such as DNA methylation, histone modification, and RNA interference.

Somaclonal variation can be considered as a double-edged sword that has its own merits and demerits based on the objective of the micropropagation experiment. If the objective of micropropagation is breeding, increasing diversity, and generating new variants, somaclonal variation can be considered a beneficial event. On the other hand, if the objective of micropropagation is the production of true-to-type clones, somaclonal variation can be considered as an obstacle.

Although previous cannabis tissue culture studies have shown that regenerated cannabis plants are phenotypically similar to the mother plants and genetically stable with a low mutation rate [78,81,153,154,155], they employed low-resolution molecular markers such as Inter Simple Sequence Repeats (ISSR), which leads to the detection of somaclonal variation, only, at specific genomic regions. Recently, Adamek et al. [156] employed deep whole-genome sequencing to determine the accumulation of somatic mutations within different parts of an individual Cannabis sativa cv. “Honey Banana” plant. They identified a significant number of intra-plant genetic diversity that could impact the long-term genetic fidelity of clonal lines and potentially contribute to the phenotypic variation. Application of the new approaches based on NGS technologies in combination with epigenetic studies is required for the future investigation of the mutation rate in micropropagated cannabis.

3. Ploidy Engineering in Cannabis

Polyploidy is common in many cultivated crop species including wheat, banana, potato, sugar cane, rye, alfalfa, apple, and strawberry [157]; however, the way in which each crop harnesses the benefits of polyploidy is unique. Polyploid can be used as a method of increasing heterosis in a population or can help to mask deleterious alleles [158]. The ploidy level of crops can also be manipulated to induce desired characteristics such as seedless fruits and is achieved by crossing two individuals with unique ploidy levels to produce progeny with an odd number of chromosomes [157]. This is a desired characteristic in cannabis production as seedless flowers produce a greater economic yield [48]. As the production of cannabis moves outdoors, seedless cultivars will likely become increasingly popular. Cannabis is naturally a diploid and multiple successful artificial inductions of polyploidy in cannabis have been reported [159,160,161]. Kurtz et al. [160] have used this technique to produce triploid plants, but field performance and lack of seed development have not yet been reported. These reports provide promising results for the potential for polyploidy to be used to improve cannabis cultivars. Polyploidy induction studies in cannabis have been summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Polyploidy induction studies in Cannabis.

3.1. Types of Polyploids

Polyploidy occurs when the normal somatic cells of an organism have more than two sets of homologous chromosomes [158]. An organism can also be a chimera where the individual is composed of cells with different numbers of chromosomes. If the DNA content within the chimera has various ploidy levels, then the organism is a mixoploid [157]. Autopolyploid is defined as polyploidization within a single species and can be produced either somatically or sexually [158].

Somatic polyploids are produced using anti-mitotic agents that are intended to alter the process of mitosis inducing irregular cell division [157]. Oryzalin has been proven to effectively disrupt the action of mitosis in plants through disruption of microtubule action [158]. In contrast, allopolyploid is described as a polyploidization as a result of a hybridization between two unique species, which has not yet been documented for cannabis [158,161].

3.2. Advantages to Polyploidy in Breeding Programs

The natural production of polyploids is considered to be one of the major mechanisms of speciation [158]. The formation of polyploids in nature creates increased heterosis, which could potentially be exploited by modern breeders.

A major benefit of polyploidy is the ability to produce seedless triploids [157]. The production of seedless plants requires crossing two individuals with different ploidy levels. This is usually done by crossing a tetraploid and diploid plant [158]. As both the diploid and tetraploid organisms contain even sets of chromosomes the pairs segregate normally [163]. The two gametes fuse in the mother and produce a triploid (2n = 3x) embryo [163]. The triploid embryo is viable and can undergo regular cell division. The seedless mechanism in triploids alters meiosis so that viable gametes are not produced. Due to the inability of the triploid plant to produce viable gametes, seed production is aborted [164]. Seedless cultivars of cannabis are particularly valuable as studies have shown that seed sets reduce the production of secondary metabolites [165]. This is of particular interest to commercial operations as production moves outdoor.

3.3. Disadvantages to Polyploid Breeding

While autopolyploids provide many benefits to breeders, there are also some fundamental problems with breeding at higher ploidy levels. One drawback to polyploid breeding is that heterozygotes and homozygotes do not separate into classic mendelian ratios [157]. This becomes a significant issue when selecting for disease resistance or selecting more than one recessive trait [158]. Another issue breeders face is that combining two recessive traits becomes more difficult where the chance of getting a double recessive genotype decreases from 1/16 to 1/1296 in tetraploids [157]. This suggests that if the goal of a polyploid breeding program is to combine two or more recessive alleles it would be beneficial to make these improvements at the diploid level before polyploidization. Finally, severe inbreeding depression in polyploid cannabis could render this mechanism useless [163].

3.4. Effects of Polyploidy

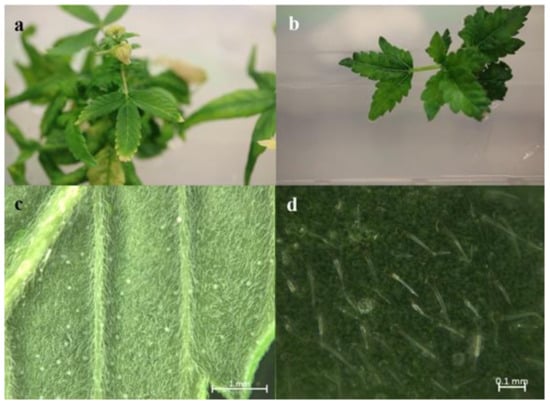

Studies observing the morphological traits of tetraploid hemp-type cannabis have shown differences in leaf width, stomate count, and stomate size compared to diploid plants (Figure 5) [159]. The tetraploid leaves were 47% larger than diploid leaves and the tetraploid flowers were more than twice the diameter in comparison to the control flowers [159]. Stomates in the tetraploid plants were twice the length of the diploid stomates but the stomate density was lower [159]. The above-ground shoot weight of the tetraploid plants was almost twice the mass of the diploids. At the cellular level, it is noted that tetraploid individuals have larger mesophyll cells and less intercellular space [162].

Figure 5.

Comparing the morphological traits of diploid and tetraploid cannabis (a) Diploid Cannabis leaf, (b) Tetraploid Cannabis leaf, which is noticeably wider than the diploid, (c) Bright light image of diploid Cannabis stomata, (d) Bright light image of tetraploid Cannabis stomata.

A recent study [161] reported a successful in vitro polyploidy induction in a drug type cannabis using oryzalin. In this study, growth media was supplemented with various concentrations of oryzalin ranging from 20–150 µM and clonal explants from a greenhouse were exposed to treatments for 24 h. The most successful treatments reported were 20 and 40 µM concentrations [161]. Two cultivars were used in this trial and results did vary between treatments. For one cultivar, the 20 µM treatment was sufficient to induce polyploidy; however, for the second cultivar the 20 µM concentration did not produce tetraploids and the 40 µM treatment was most successful. It was noted that following treatments it took several weeks for explants to show any signs of growth. Following treatments, explants were acclimatized and transferred to a greenhouse to observe growth. Tetraploid plants showed an increase in rooting time and a decrease in rooting success compared to diploids [161]. The polyploid plants had slight morphological differences compared to diploids. Tetraploid plants had wider leaves, larger stomates, and a lower density of stomates compared to diploids [161]. The effect of polyploidy on phytochemical composition was noted and CBDA was the only cannabinoid that increased in the polyploid population. In addition, the terpene content of the cannabis plants was also increased in the polyploid population [161].

3.5. Secondary Metabolites

Many species that produce secondary metabolites have witnessed an increased production of these compounds at higher ploidy levels [158]. An increase of secondary metabolite production yield has been reported in polyploid Vetiveria zizanioides L. Nash compared to its diploid counterpart [166]. This species produces aromatic compounds valuable to the fragrance industry and production of these compounds was increased by over 62% when polyploidy was induced [166]. As secondary metabolites produced by cannabis are becoming a legal commodity, the production of these compounds needs to be optimized. In recent literature, it has been reported that polyploid cannabis plants had lower THC production compared to diploid controls but also had increased CBD production [161]. In hemp, the polyploid individuals produced on average 50% less THC in the female flowers compared to the control, but CBD production in the female leaves was more than three times greater in the polyploid population [162]. This study utilized a hemp variety of cannabis, which is bred for low secondary metabolite production [162]. Duplication of some deleterious recessive alleles may be responsible for the decreased THC concentration observed in polyploid cannabis plants. A deleterious allele affecting an important enzyme involved in the metabolic pathway of cannabinoid synthesis could inhibit the entire process. Secondary metabolites such as cannabinoids are heavily dependent on the presence of chemical precursors and enzymes [158].

3.6. Limitations of Existing Polyploidy Literature and Future Potential

Based on the current literature there is very little reported work in the interest of polyploidization in cannabis, with only moderate morphological/chemical differences [161,162]. However, it should be noted that the existing literature does not evaluate many agronomically important traits and only evaluated the first generation of artificially induced autotetraploids. It is worthwhile to mention that, while the tetraploids hold twice as many chromosomes, they do not contain a greater number of unique alleles. Further studies including crosses of unique tetraploids are needed to fully understand the effects of tetraploidy that includes greater allelic diversity. It is possible that while the initial generation of tetraploids is similar to their diploid progenitors, subsequent generations may demonstrate unique phenotypes that are of use to modern breeding programs. Regardless, the use of tetraploids to produce seedless triploids has great potential for the cannabis industry. Moreover, ploidy engineering can be used in cannabis for terpene manipulation, CBD-to-THC ratio in hemp, biomass improvements, and novel cannabinoid production.

4. Genetic Engineering Approaches in Cannabis

Plant genetic engineering can be considered a basic approach to studying gene function and genetic improvement. Generally, plant cells can be either transiently or stably transformed [167]. Although there are a few studies [168,169] that used targeting-induced local lesions in genomes (TILLING) and virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) approaches for studying the function of some genes in cannabis, there is still a dire need for developing a stable gene transformation system [93]. TILLING, as a powerful method for selecting mutations in specific genes, was used by Bielecka et al. [168] to find cannabis plants with mutations in CsFAD2 and CsFAD3 genes that result in the modification of the seed-oil composition. The requirement of large mutant populations and homozygous mutations are the flip side of the TILLING method. Recently, the VIGS system using Cotton leaf crumple virus (CLCrV) was successfully applied in cannabis to knockdown endogenous phytoene desaturase (PDS) and magnesium chelatase subunit I (ChlI) genes [169].

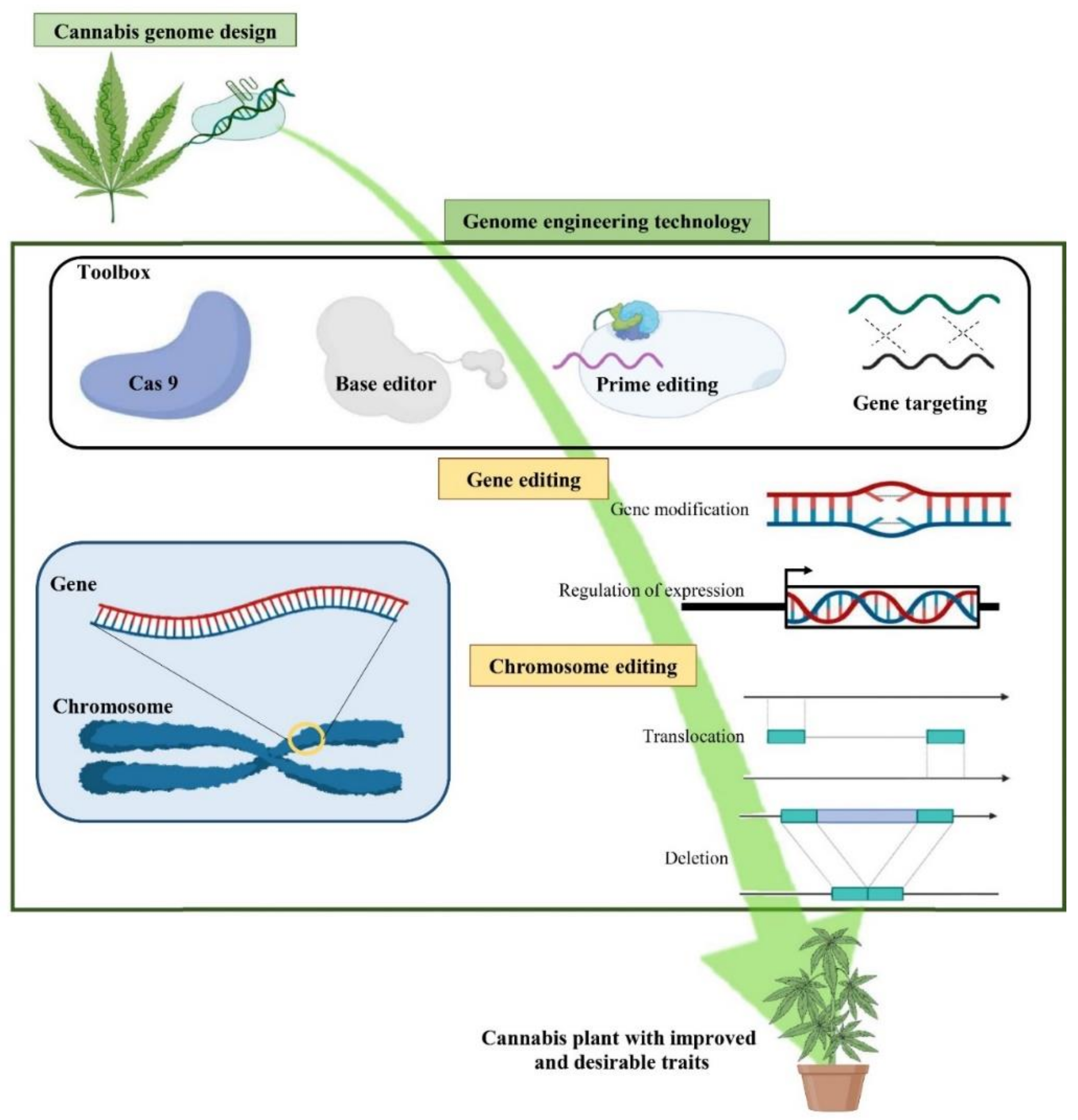

Genetic transformation allows foreign genes to be introduced into a crop and has been extensively used to introduce a variety of important traits (herbicide resistance, pro-vitamin A production, insect resistance, etc.) into major crops for decades [167]. CRISPR/Cas systems have also been recently applied for modifying major crops such as wheat and rice [170]. Developing a gene transformation and/or genome editing systems in cannabis are not only useful for modifying horticultural traits, growth morphology, and biotic and abiotic stress resistance but are also important for studying gene functions. Agrobacterium- and Biolistic-mediated gene transformation systems, de novo meristem induction, and virus-assisted gene editing are applicable to cannabis. Biolistic-mediated gene transformation, which uses particle bombardment to transfer the gene into the plant, and genome editing methods have not yet been reported in cannabis. On the other hand, several studies have investigated Agrobacterium-mediated gene transformation in cannabis. The Agrobacterium-mediated gene transformation system is directly dependent on plant tissue culture (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

The schematic diagram of Agrobacterium-mediated gene transformation.

Recently, Beard et al. [141] used the protoplast of C. sativa var. Cherry x Otto II: Sweetened for transient transformation with plasmid DNA containing a fluorescent marker gene. The authors reported that more than 31% of the cells were successfully transformed. Although gene transformation has been achieved in cannabis by different studies [141,171,172,173,174,175,176], there is only one report regarding transgenic plant regeneration [93].

In the following section, cannabis transformation studies, factors involved in gene transformation, and strategies for improving gene transformation have been discussed.

4.1. Agrobacterium-Mediated Gene Transformation

As soon as the susceptibility of cannabis genotypes to Agrobacterium was revealed [171], Agrobacterium-mediated gene transformation in cannabis became of great interest to many. However, several obstacles have been reported for establishing and developing gene transformation in cannabis such as low efficiency of gene transformation, low rates of regeneration, chimeric regeneration including both non-transgenic and transgenic cells and tissues, as well as inactivation of the transgene [10,47]. Therefore, it is crucial to study different factors involved in gene transformation such as Agrobacterium strains, treatments for explants infection, selection markers, eliminating chimerism, promoters, and translational enhancer. Agrobacterium-mediated gene transformation studies have been summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Agrobacterium-mediated gene transformation studies in Cannabis.

4.1.1. Agrobacterium Strains

Agrobacterium strain selection is one of the most important factors in gene transformation (Table 5). The first study of successful gene transformation with more than 50% transformation frequency in fiber-type cannabis (hemp) was performed by MacKinnon et al. [171]. However, they did not report which strain of Agrobacterium was used. Feeney and Punja [172] obtained an acceptable transformation efficiency (15.1 to 55.3%) by using A. tumefaciens EHA101. Wahby et al. [173] used three A. tumefaciens strains including LBA4404, C58, and IVIA 251, as well as eight A. rhizogenes strains including 476, 477, 478, A424, AR10GUS, A4, AR10, and R1601 for establishing hairy root cultures in different genotypes of cannabis. According to their results, genotypes had different responses to Agrobacterium strains in such a way that transformation efficiency ranged between 43% for AR10GUS to 98% for R1601 in A. rhizogenes strains, and between 33.7% for IVIA251 and 63% for C58 for A. tumefaciens strains. Generally, Wahby et al. [173] reported that the gene transformation frequency in cannabis is dependent not only on the strains of Agrobacterium but also on cannabis genotypes, consisting of their sensitivity to agro-infection and their potential to regenerate transgenic tissues.

Deguchi et al. [175] compared transformation efficiency among several hemp genotypes in including Ferimon, Fedora 17, USO31, Felina 32, Santhica 27, Futura 75, CRS-1, and CFX-2 using different A. tumefaciens strains including LBA4404, GV3101, and EHA105 and found high transformation efficiency (>50%) for some genotypes. Based on their results, the maximum GUS expression was observed in the CRS-1 genotype and A. tumefaciens GV3101 led to the highest transformation frequency. In another study, Sorokin et al. [176] investigated the potential of A. tumefaciens EHA105 in transforming different cannabis genotypes (Candida CD-1, Holy Grail x CD-1, Green Crack CBD, and Nightingale) and obtained a high transformation efficiency (45–70.6%). Different responses to Agrobacterium strains are not unique to cannabis and it has been previously documented that various Agrobacterium strains differ in their capacity to transform different recalcitrant plants such as maize [177]. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate more strains to obtain efficient strains for a high-frequency gene transformation protocol.

4.1.2. Infection of Explant

The physiological condition and source of explants play a pivotal role in Agrobacterium-mediated gene transformation. Different explants such as shoot tip and hypocotyl have been employed for gene transformation in cannabis (Table 5). Most studies used different parts of in vitro grown seedlings. MacKinnon et al. [171] succeeded in gene transformation using shoot tip explants that were selected from greenhouse-grown cannabis. Feeney and Punja [172] used callus cells derived from stem and leaf segments of cannabis for Agrobacterium-mediated gene transformation. In another study, Wahby et al. [173] used different parts of 5-day-old in vitro grown seedling of hemp including hypocotyls, cotyledons, cotyledonary node, and primary leaves for gene transformation and reported that the best gene transformation results were obtained from hypocotyl segments. Sorokin et al. [176] also used cotyledons and true leaves of 4-day-old in vitro grown seedling of hemp for gene transformation. Deguchi et al. [175] reported a successful gene transformation using male and female flowers, stem, leaf, and root tissues derived from 2-month-old in vitro grown seedling of hemp.

The co-cultivation period and concentration of Agrobacterium inoculum (optical density (OD)) have a significant impact on successful gene transformation. Feeney and Punja [172] suggested three-day co-cultivation and OD600nm 1.6–1.8 for gene transformation of callus cells. In another study, different explants were co-cultured for two days [173]. Sorokin et al. [176] suggested three days of co-cultivation and OD600nm 0.6 for gene transformation of different parts of in vitro grown seedling of hemp.

Agrobacterium infection efficiency in cannabis can be increased by adding chemical compounds, such as sodium citrate, acetosyringone, and mannose, to the co-cultivation medium. Feeney and Punja [172] reported increased Agrobacterium infection using 100 µM acetosyringone and 2% mannose for hemp gene transformation in the co-cultivation medium. Wahby et al. [173] studied the effect of different concentrations of acetosyringone (20, 100, and 200 µM), sucrose (0.5 and 2%), sodium citrate (20 mM), and 2-N-morpholineethanesulfonic acid (MES) (30 mM) on the gene transformation of cannabis and reported that different chemical compounds had little impact on Agrobacterium infection efficiency, and 20 µM acetosyringone resulted in the best results. On the other hand, Deguchi et al. [175] applied 200 μM acetosyringone, 2% glucose, and 10 mM MES for increasing strain virulence in the gene transformation of hemp. Sorokin et al. [176] also reported increasing the Agrobacterium infectability by using 100 µM acetosyringone for cannabis gene transformation in the co-cultivation medium. Recently, Karthik et al. [178] reported that SNP improved the efficiency of Agrobacterium-mediated gene transformation in soybean. Therefore, it is reasonable to investigate the effects of SNP on the gene transformation of cannabis.

4.1.3. Selection Markers

Although kanamycin has been the main selection agent of transgenic cannabis cells and tissues, other antibiotics, such as spectinomycin, rifampicin, and chloramphenicol, have also been successfully applied for selecting the transformed cells and tissues of cannabis [10,47]. However, it is necessary to study the effect of other antibiotics on cannabis gene transformation because the response of various tissues and genotypes to different antibiotics may vary. For instance, Sorokin et al. [176] and Feeney and Punja [174] used spectinomycin- and kanamycin-resistant genes as selectable markers in the Agrobacterium vectors. Wahby et al. [173] used Agrobacterium vectors carrying kanamycin-, carbenicillin-, and rifampicin-resistant genes for transforming cannabis. Sorokin et al. [176] also used kanamycin- and rifampicin-resistant genes in Agrobacterium vectors. Moreover, Deguchi et al. [175] considered the chloramphenicol-resistant gene as a selective marker in Agrobacterium vectors.

Twin T-DNA binary vectors have also been successfully used for generating marker-free transgenic plants. This would be a very useful and promising method for generating marker-free transgenic cannabis and to mitigate scientific and public concerns regarding dispersing herbicide- and antibiotic-resistant genes of GMO products into the environment.

4.1.4. Eliminating Chimerism

The regeneration of chimeric tissue with both non-transformed and transformed cells and tissues is one of the most crucial challenges in developing a stable gene transformation system in different plants [179]. Therefore, it is essential to use an approach to eliminate the chimeric cells and regenerate only transgenic cells. Feeney and Punja [172] studied the gene transformation frequency and chimerism using the phosphomannose isomerase (PMI) selection strategy, which is based on the existence of sugar (mannose) in the medium. They compared two transformation procedures including 1% mannose and 300 mg/L Timentin (treatment 1) and 2% mannose and 150 mg/L Timentin (treatment 2) and reported that treatment 1 was not capable of distinguishing non-transgenic cells from transgenic cells, and, therefore, they suggested treatment 2 for gene transformation in cannabis. Wahby et al. [173] compared the transformation performance and chimerism of two procedures of gene transformation: complex media MI1 (100 µM acetosyringone, 0.5% sucrose, and 30 mM MES) and MI2 (200 µM acetosyringone, 2% sucrose, 20 mM sodium citrate) and reported that these media could not completely detect transgenic tissues from non-transgenic tissues. Chimerism in transformation systems is not unique to cannabis and is a challenge in many species and is highly dependent on the regeneration system. Moving forward, developing an efficient somatic embryogenesis-based regeneration system will be important to mitigate this issue.

4.1.5. Promoters and Translational Enhancer

Sorokin et al. [176] and Feeney and Punja [174] used the binary vector pNOV3635 and pCAMBIA1301, respectively, carrying a coding region for PMI under control of the nopaline synthase terminator (NOS) and the ubiquitin promoter derived from Arabidopsis thaliana (Ubq3), as well as a spectinomycin and kanamycin selectable marker genes. They also used chlorophenol-red PMI assay, PCR, and southern blot for confirming gene transformation.

When the β-glucuronidase (GUS) reporter gene was employed using the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S RNA (CaMV35S) promoter, GUS activities were observed [173]. In another study, Deguchi et al. [175] used a pEarleyGate 101 vector harboring the eGFP gene and uidA gene under the control of the CaMV 35 S promoter and OCS terminator for GFP fluorescence and GUS staining assays. Moreover, Sorokin et al. [176] reported that when the GUS gene in the pCAMBIA1301 vector was under the control of a CaMV 35S:: Intron, the highest GUS activity in the transgenic cannabis was achieved. While future studies will undoubtedly establish more efficient, or tissue/age-specific promotors, existing promoters are generally effective in cannabis.

4.2. Strategies to Improve Gene Transformation Efficiency

Despite advances in the gene transformation of cannabis over the past few years, efficient transgenic regeneration remains an obstacle. The ability to express and introduce transgene and to regenerate de novo shoots or embryos are two important obstacles to producing transgenic cannabis. Recent studies have confirmed that cannabis cells can be efficiently transformed [10,47,176]; however, there is only one report of transgenic cannabis regeneration [93]. The application of genes related to regulating plant growth and development such as WUSCHEL (WUS) [180], BABY BOOM (BBM) [181], and Growth-Regulating Factors (GRFs) alone or in combination with GRF-Interacting Factor (GIF) [182] is reported as a promising approach to increase plant regeneration efficiency [170]. In this way, ectopic overexpression of genes involved in meristem maintenance, somatic embryogenesis, or phytohormone metabolism can be used to overcome plant regeneration obstacles in recalcitrant plants [183]. Numerous genes involved in meristem maintenance, somatic embryogenesis, and phytohormone metabolism have been identified in different plants [180,183,184]. Accordingly, these studies led to novel approaches for in vitro plant regeneration and Agrobacterium-mediated gene transformation research on recalcitrant species. The downside of this approach is that morphogenic genes have adverse pleiotropic impacts and should be removed from transformed or edited plants [180,182,183,184]. The next sections presented recent progress in using morphogenic genes and highlighted possible approaches to overcome negative pleiotropic effects.

4.2.1. Morphogenic Genes, Key Factors in Plant Regeneration

Morphogenic genes that induce regeneration, when overexpressed, are categorized into two classes according to their growth reactions. The first group is composed of genes (e.g., SERK1, AGL15, WUS, and STM) that improve a pre-existing response of embryogenesis under in vitro conditions [180]. The second group includes genes (e.g., BBM, EMK, RKD4, LEC1, LEC2, L1L, HAP3A, FUS3, WUS, WOX5, KN1, CUC1, CUC2, ESR1, and ESR2) that stimulate ectopic embryogenesis or meristem induction under in vitro conditions where such events are usually not seen [180,183,185,186]. The roles of morphogenic genes in plant regeneration have been summarized in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

A schematic view of the morphogenic genes demonstrating their roles in plant growth and development as well as in vitro plant regeneration (AGL15: AGAMOUS-LIKE15; ARR: ARABIDOPSIS RESPONSE REGULATOR; BBM: BABY BOOM; CLV3: CLAVATA3; CUC: CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON; ESR: ENHANCER OF SHOOT REGENERATION; FUS3: FUSCA3; GA3ox: Gibberellin 3-beta-dioxygenase; IAA30: Indole acetic acid inducible 30; LEC: LEAFY COTYLEDON; PIN1: PIN-FORMED 1; PKL: PICKLE; PLT: PLETHORA; PRC: Polycomb repressive complex; STM: SHOOT MERISTEMLESS; TAA: TRYPTOPHAN AMINOTRANSFERASE ARABIDOPSIS; WOX: WUSCHEL-related homeobox; WUS: WUSCHEL; YUC: YUCCA).

In the first class, the overexpression of genes leads to an increase in embryogenesis under in vitro conditions in which the formation of somatic embryos is already observed. For instance, overexpression of SOMATIC EMBRYOGENESIS RECEPTOR KINASE1 (SERK1) using CaMV 35S promoter resulted in ~4-fold and 2-fold increases in somatic embryogenesis of Arabidopsis thaliana [187] and Coffea canephora [188], respectively. Similarly, further studies in Arabidopsis [189], cotton [190], and soybean [191] have shown an increase in somatic embryogenesis with overexpression of the AGAMOUS-LIKE15 (AGL15) gene, a member of the SERK1 protein complex [192]. It is also well documented that SERK1 and SERK3 are the co-receptors of the Brassinosteroid Insensitive 1 (BRI1) protein. Brassinosteroid is a known PGR that plays a key role in plant embryogenesis. The members of SERK proteins seem to act as mediators across the plasma membrane for brassinosteroid signaling [193].

The use of meristem formation-related genes such as SHOOT MERISTEMLESS (STM) [194] or A. thaliana WUSCHEL (AtWUS), a key gene for regulating meristem cell fate [195], have also resulted in improving embryogenic responses. Arroyo-Herrera et al. [196] reported that somatic embryogenesis in Coffea canephora was increased up to 3–5 fold using an estradiol-inducible AtWUS construct. In line with this result, Bouchabké-Coussa et al. [197] reported that using the 35S::AtWUS cassette led to a 3-fold increase in somatic embryogenesis of Gossypium hirsutum after Agrobacterium-mediated gene transformation. In another study, microspore-derived embryogenesis of Brassica napus was increased using the 35S::BnSTM construct [198].

In the second class, gene overexpression leads to spontaneous regeneration or direct ectopic regeneration of meristems or embryo-like structures in the lack of inductive in vitro conditions. The early studies have shown that overexpression of the AtWUS gene [199] and B. napus BABY BOOM (BnBBM) gene, a member of the AP2/ERF transcription factors (TFs) [200], leads to embryonic morphogenesis. Consequently, Boutilier et al. [200] reported that the constitutive expression of the BnBBM gene in A. thaliana led to ectopic somatic embryogenesis and these ectopic embryos could generate plantlets in the lack of PGRs. This approach has been successfully used to regenerate the transgenic T0 plantlets in different plants using orthologs of the BnBBM gene such as transforming 35S::AtBBM into Nicotiana tabacum [201], soybean 35S::GmBBM into A. thaliana [202], oil palm 35S::EgBBM into A. thaliana [203], and 35S::TcBBM into Theobroma cacao [204]. In another study, Tsuwamoto et al. [205] reported that ectopic overexpression of A. thaliana EMBRYOMAKER (AtEMK) led to embryo-like structures at 23% of cotyledon tips; however, these structures could not regenerate the plantlets. They concluded that AtEMK, a member of the AP2/ERF TFs and related to BBM, should be expressed under a regulated network for avoiding pleiotropic effects and achieving normal plantlets. RKD4 as a key gene in the RWP-RK TF family is another gene that has an important role during early embryo development in A. thaliana and plays a pivotal role in the first asymmetrical zygotic division [206,207]. For instance, ectopic somatic embryogenesis of Phalaenopsis, a plant typically reluctant to direct somatic embryogenesis, was obtained using the chemical induction of transgenic RKD4 [208].

The overexpression of genes related to embryo maturation (e.g., FUSCA3 (FUS3), LEAFY COTYLEDON1 (LEC1), and LEC2) causes similar morphogenic reactions. Lotan et al. [209] characterized the first of these genes namely LEC1, in which a cassette of 35S::AtLEC1 was transformed to A. thaliana. Although the embryo-like structures were produced, functional ectopic embryogenesis was not observed [209]. In another study, Zhu et al. [210] used a 35S::CsL1L cassette for overexpression of Citrus sinensis LEC1 after gene transformation in epicotyls of sweet orange and reported that embryo-like structures were obtained after two months. They concluded that overexpression of L1L in Citrus is sufficient for recovering functional somatic embryos. However, Uddenberg et al. [211] indicated that although the overexpression of the LEC1/L1L (PaHAP3A) did not lead to ectopic embryogenesis in vegetative tissues, ectopic embryogenesis was obtained during zygotic embryo maturation. These findings showed that certain types of cells and tissues may be more receptive to morphogenic genes for enhancing ectopic embryogenesis or meristem maintenance [211]. Later studies have shown that the overexpression of LEC2 leads to more somatic embryogenesis in comparison with LEC1, FUS3, or L1L [212,213,214].

However, several studies [190,197,198,200] showed that pre-existing embryogenic responses are increased through overexpression of morphogenic genes, and additional studies revealed that ectopic overexpression of morphogenic genes resulted in improving somatic embryogenesis where such events are usually not seen [183]. Zuo et al. [199] identified the first “meristem” gene in Arabidopsis (AtWUS) which enhances somatic embryogenesis. They suggested that the vegetative-to-embryonic transition can be stimulated by the WUS gene. Moreover, Gallois et al. [215] demonstrated that the overexpression of WUS and STM genes generates the bulk of cells contiguous to the WUS foci showing primary meristems. In another study, Gallois et al. [216] indicated that unique phenotypes obtained from WUS overexpression were related to different factors such as co-expression of other morphogenic TFs, phytohormone regime, and type of WUS activation (such as GAL4-VP16 activation method and HSP::CRE-mediated excision). Rashid et al. [217] also reported that a member of the WUS/WOX gene family namely AtWOX5 led to the direct organogenic response in Nicotiana tabacum. Luo et al. [218] showed that shoot organogenesis in N. tabacum was increased 3-fold by overexpression of the maize STM ortholog KNOTTED1 (KN1) through 35S::ZmKN1 cassette. Similar results were reported by Nishimura et al. [219].

The CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON1 (CUC1) and CUC2 genes are known to have a key role in the shoot meristem formation. Daimon et al. [220] indicated that the overexpression of AtCUC1 and AtCUC2 under a CaMV 35S promoter resulted in a significant increase (about 6.5–9-fold) in shoot organogenesis of A. thaliana transgenic calli. However, no micro-shoots were recovered in the lack of hormones, showing the hormone-dependent function of CUC1 and CUC2 genes. Genes related to the phytohormone signal transduction (both downstream targets and receptors), play a pivotal role in improving plant regeneration; genes like ENHANCER OF SHOOT REGENERATION 1 (ESR1) and ESR2 that are involved in the cytokinin response pathway and MONOPTEROS (MP) that is involved in the auxin response pathway. Several studies have shown that the overexpression of these genes led to an increase in the shoot meristem formation [221,222,223]. Moreover, the phenotypic response of morphogenic genes can be impacted by levels of phytohormones. For instance, Wójcikowska et al. [224] reported that the high and low concentrations of auxin led to callogenesis and somatic embryogenesis, respectively, in the transformed A. thaliana overexpressing LEC2 under a dexamethasone (DEX)-inducible system.

4.2.2. Strategies to Overcome Pleiotropic Effects

Based on the aforementioned literature and other references therein, it is clear that the use of morphogenic genes may help to increase regeneration efficiency in plants. However, strong and constitutive overexpression of these genes can lead to unwanted pleiotropic effects such as infertility of regenerated plants [170]. A promising approach to mitigate this is to implement an inducible expression system for these genes in a stable transformation system. This means, it is necessary to apply an additional step that includes optimization of the morphogenic gene expression level with restricting expression after transformation. Such an approach causes enhanced gene transformation and improved fertile and healthy T0 plantlets regeneration. Generally, there are five strategies to cope with these challenges including (i) removing the morphogenic gene when no longer needed, (ii) using the inducible expression of the gene for improving morphogenic growth response followed by excision of the inducing ligand for silencing the expression, (iii) using Agrobacterium-mediated gene transformation in such a way that promotes the transient expression of the morphogenic genes, (iv) using promoter that can turn off the morphogenic regulatory gene when no longer required, and (v) using GRF-GIF Chimeras [180,182,183,185,186].

The excision-based method has provided a reliable strategy for applying morphogenic genes to regenerate fertile and healthy transgenic plantlets. The first successful application of this method through BBM and Flippase (FLP)-recombinase was reported in Populus tomentosa [225]. A T-DNA construct including a single pair of FLP Recombination Target Sites (FRT) encompassing both a CaMV 35S promoter stimulating B. campestris BBM (BcBBM) expression and a heat-shock inducible promoter stimulating expression of FLP recombinase was designed. Deng et al. [225] reported that after transforming this T-DNA construct, more than 28% of calli produced normal plantlets on phytohormone-free media and also showed that 42 °C heat shock treatment for 2 h resulted in the removal of both the BBM and FLP recombinase cassettes. In another study, Lowe et al. [226] reported that high transformation efficiency in inbred maize was obtained by low expression of ZmWUS2 (using the Agrobacterium NOPALINE SYNTHASE, or NOS, promoter) and overexpression of ZmBBM (using the Zea mays UBIQUITIN promoter). The explants were inoculated on dry filter paper to induce a desiccation-stimulated maize promoter derived from an ABA-responsive gene (RAB17) carrying CRE recombinase, which then removed these 3 expression cassettes. After the removal of the BBM, WUS2, and CRE transgenes, only the T-DNA construct with the genes of interest were remained. This method has been successfully used in other recalcitrant plants such as sorghum, rice, corn, and sugarcane [227].

Inducible expression to control morphogenic gene expression is another robust alternative approach. Heidmann et al. [228] reported that gene transformation in Capsicum annum, a recalcitrant plant species, was achieved using the 35S::BnBBM~GR vector for gene transformation and cultivation of explants in the medium consisting of DEX and TDZ. In a similar study, Lutz et al. [229] reported that transgenic fertile and healthy A. thaliana plantlets were achieved using the DEX-inducible AtBBM~GR cassette.

The overexpression of PLANT GROWTH ACTIVATION genes, such as PGA37 in A. thaliana led to the transition of the vegetative phase to the embryogenic phase by using the estradiol-inducible system [230]. The PGA37 gene, based on the DNA-binding domain similarities, encodes the MYB118. Wang et al. [230] reported that root segments developed somatic embryos by PGA37 expression under inducible control, which were related to overexpression of LEC1. The green-yellowish embryonic calli were produced through the expression of PGA37 using the estradiol-inducible system in the medium containing auxin after 7–10 days of inoculation and somatic embryos were obtained after 3–5 weeks. When estradiol was removed from the medium, which causes downregulating PGA37 expression, healthy, fertile plantlets were obtained from the somatic embryos. Moreover, Wang et al. [230] showed that estradiol-induced expression of MYB115, a closely related homolog, resulted in somatic embryogenesis from root segments. A similar strategy using DEX-induced expression of TcLEC2 was successfully used for the regeneration of transgenic somatic embryos in Theobroma cacao [231].

Using Agrobacterium-mediated gene transformation in such a way that promotes the transient expression of the morphogenic genes is another alternative strategy [232,233,234,235]. Negative selectable markers located outside the T-DNA (beyond the left border) have been used to remove plant cells containing these sequences [233]. Other studies have located a positive marker gene outside the T-DNA, which could be transiently expressed for generating marker-free transgenic plants [236]. A mixture of T-DNAs could be received by placing an Agrobacterium-derived isopentyl transferase (IPT) gene outside the T-DNA, with the greater part of the T-strands containing the trait and a minority of T-strands not terminated properly outside the T-DNA, including the flanking IPT gene. Therefore, the transient expression of the IPT gene could stimulate the signaling of cytokinin and subsequently improve shoot proliferation, which results in the recovery of transgenic plants without a selectable marker. This strategy was successfully used in maize genotypes by positioning WUS2 and BBM beyond the left border for transient somatic embryogenesis and subsequent transgenic plantlet regeneration [183].

Recently, a new strategy has been developed using the maize phospholipid transfer protein (PLTP) promoter driving BBM and the maize auxin inducible (AXIG1) promoter for improving gene transformation [237]. The application of these two promoters in the expression cassettes led to somatic embryogenesis within a week, and germination of these somatic embryos within 3–4 weeks. Similarly, the use of a combination of GRF and GIF has been proposed as a new method to tackle negative pleiotropic effects [170,182,238]. Debernardi et al. [170] demonstrated that fertile transgenic wheat, rice, and citrus without obvious developmental defects can be achieved by the expression of a fusion protein combining wheat GRF4 and GIF1. Moreover, they reported that GRF4–GIF1 induced efficient plant regeneration in the absence of exogenous PGRs which helps transgenic plant selection without selectable markers. They also combined CRISPR–Cas9 with GRF4– GIF1 and regenerated edited transgenic plants. Therefore, the combination of CRISPR–Cas9 and GRF4– GIF1 can be considered a powerful and promising strategy for the regeneration of healthy and fertile transgenic plants [170]. This strategy has been recently used in cannabis. Zhang et al. [93] reported that using GRF3– GIF1 in the CRISPR vector resulted in a 1.7-fold increase in edited plant regeneration.

As a future perspective, morphogenic genes can be considered as targets of gene transformation in order to overcome current obstacles in cannabis tissue culture and successful regeneration of transformed plants. Furthermore, useful techniques enabled us to control the side effects of ectopic expression of these genes through transient and inducible gene expression in the host.

4.3. Strategies to Prevent Transgene Escape

The frequency of the alleles/genes in a population can be changed due to outcrossing of gametes or gene flow [239]. Thus, transgenes can move from a transgenic plant to their non-transgenic counterparts or wild relatives, a process called transgene escape. It is not uncommon for transgenic plants to mate with their wild relatives. Spontaneous hybridization will occur among transgenic and non-transgenic plants unless the proper distances are maintained [239]. This is an area much of concern, specifically in outcrossing plants, in plant biotechnology. Outcrossing poses negative impacts in terms of contamination in non-transgenic crops but this problem depends on whether a new allele causes an increase in transgene escape or not [240]. While dealing with trans-gene flow one should consider the situations according to transgenic crops [240]. In general, the possible containment and mitigation strategies are physical containment [241], biological/molecular containments (e.g., sterility [242], clistogamy [243], apomixes [244], maternal transformation [245], incompatible genome [246], gene splitting [247], expression in virus [248], genetic use restriction technology (GURT) [239]), and transgenic mitigation [249]. The appropriate approaches should be considered after transgenic cannabis production to prevent transgene escape.

4.4. CRISPR/Cas-Mediated Genome Editing

CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome editing has exceptionally improved plant biotechnology [43,250]. This system is robust and offers relatively high target programmability and specificity that can allow accurate genetic modification. The CRISPR/Cas system provides a unique opportunity to improve cannabis varieties with desired traits in a sustainable fashion. Recently, Zhang et al. [93] employed the CRISPR/Cas9 system to knock out the phytoene desaturase gene and they reported that four edited cannabis plantlets with albino phenotype have been successfully generated. However, the numerous new biotechnological methods such as base editing and prime editing based on CRISPR/Cas platforms would expand cannabis synthetic biology and the toolbox of fundamental research. A successful CRISPR/Cas system experiment requires designing target-specific guide RNAs (gRNAs) and an efficient regeneration protocol for developing transgenic/edited plantlets [251]. The gRNA is categorized as a chimeric RNA including a CRISPR RNA (crRNA) and a trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA). The crRNA consists of a guide (spacer) sequence that accurately navigates the Cas9 protein to the targeted gene. Then, the targeted DNA is cleaved by the RNA-guided DNA endonuclease Cas9. Another key part of CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome editing is the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM), which is a conserved and CRISPR-dependent DNA sequence motif adjacent to the target site (protospacer) and is utilized by the endogenous CRISPR in archaea and bacteria to discriminate invading- and self-DNAs. Generally, the application of an effective and precise CRISPR/Cas system is strongly dependent on the selection of the best guide sequence (gRNA target site) [43,250,251].

In the previous sections, promising approaches for developing tissue culture protocols for genetic material delivery (e.g., Agrobacterium-mediated method) and regeneration methods have been discussed. In this section, we discuss the principles of designing gRNA in order to produce precise target mutation(s) and prevent off-target mutations as one of the most important prerequisites of genome editing technology. We also present the available bioinformatics tools for designing gRNAs that can be used in cannabis.

The prediction of the presence of off-target sites (i.e., unintended mutations) is one of the most important steps in designing gRNA for CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome editing. The design of the candidate gRNAs starts with the screening of the organism’s whole-genome sequence. Therefore, the availability and accessibility of a high-quality reference genome is required, which is the case in cannabis [252]. The genome of cannabis has been de novo assembled nearly a decade ago [253]; however, there are still some major challenges to using the cannabis reference genome. Currently, 12 different genomes (assembled and annotated) are available for cannabis [252]. Having multiple reference genomes can be considered a bonus, but, contradictorily, there are significant differences in reported genome size, chromosome order, and gene annotations among cannabis genome assemblies [1,2,252]. Therefore, designing a precise and accurate gRNA is an important starting point for high-quality CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome editing in cannabis with the minimum off-target activities. As can be seen in Figure 8, there are three types of off-targets induced by the CRISPR/Cas system including (a) off-target sites with a base mismatch, (b) off-target sites with extra base (DNA bulge or deletion), and (c) off-target site with missing base (RNA bulge or insertion) [254]. Cases (b) and (c) are considered as the indel (insertion or deletion) off-target events [254]. It is necessary to consider these off-targets during genome engineering projects.

Figure 8.

Three types of off-targets induced by CRISPR-mediated genome editing; (a) off-target sites with base mismatch, (b) off-target sites with extra base (DNA bulge or deletion), and (c) off-target site with missing base (RNA bulge or insertion).

Over the past few years, several bioinformatics tools have been developed to design gRNAs and predict, in silico, the off-targets. These tools have significantly facilitated the successful application of CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome editing technology [43,250]. A list of bioinformatics tools that contain cannabis genome information is presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

The main characteristics of some tools for the design of gRNA for genome editing in cannabis.

Generally, these tools exploit a similar algorithm to design gRNA [255]. However, some characteristics related to the gRNA spacer region (e.g., number and type of mismatch, GC-content, length, and indels) and the selection of specific Cas-nucleases vary between these tools [256]. In general, these tools provide multiple sequences for designing gRNA, which are appropriate for editing similar genome conservative motives of various evolutionarily related genotypes [256]. These tools require the sequence of the targeted gene and the Cas-nucleases type. Then they search the genome and provide information related to candidate gRNAs such as the potential protospacers, both non-ranked and ranked with respect to their fitness, and off-target sites [255]. Generally, considering variations in the nucleotide sequences and the increase in individual gene copy number, it is necessary to design multiple gRNAs for each target for an efficient genome editing.