Abstract

The Mimosa genus belongs to the Fabaceae family of legumes and consists of about 400 species distributed all over the world. The growth forms of plants belonging to the Mimosa genus range from herbs to trees. Several species of this genus play important roles in folk medicine. In this review, we aimed to present the current knowledge of the ethnogeographical distribution, ethnotraditional uses, nutritional values, pharmaceutical potential, and toxicity of the genus Mimosa to facilitate the exploitation of its therapeutic potential for the treatment of human ailments. The present paper consists of a systematic overview of the scientific literature relating to the genus Mimosa published between 1931 and 2020, which was achieved by consulting various databases (Science Direct, Francis and Taylor, Scopus, Google Scholar, PubMed, SciELO, Web of Science, SciFinder, Wiley, Springer, Google, The Plant Database). More than 160 research articles were included in this review regarding the Mimosa genus. Mimosa species are nutritionally very important and several species are used as feed for different varieties of chickens. Studies regarding their biological potential have shown that species of the Mimosa genus have promising pharmacological properties, including antimicrobial, antioxidant, anticancer, antidiabetic, wound-healing, hypolipidemic, anti-inflammatory, hepatoprotective, antinociceptive, antiepileptic, neuropharmacological, toxicological, antiallergic, antihyperurisemic, larvicidal, antiparasitic, molluscicidal, antimutagenic, genotoxic, teratogenic, antispasmolytic, antiviral, and antivenom activities. The findings regarding the genus Mimosa suggest that this genus could be the future of the medicinal industry for the treatment of various diseases, although in the future more research should be carried out to explore its ethnopharmacological, toxicological, and nutritional attributes.

1. Introduction

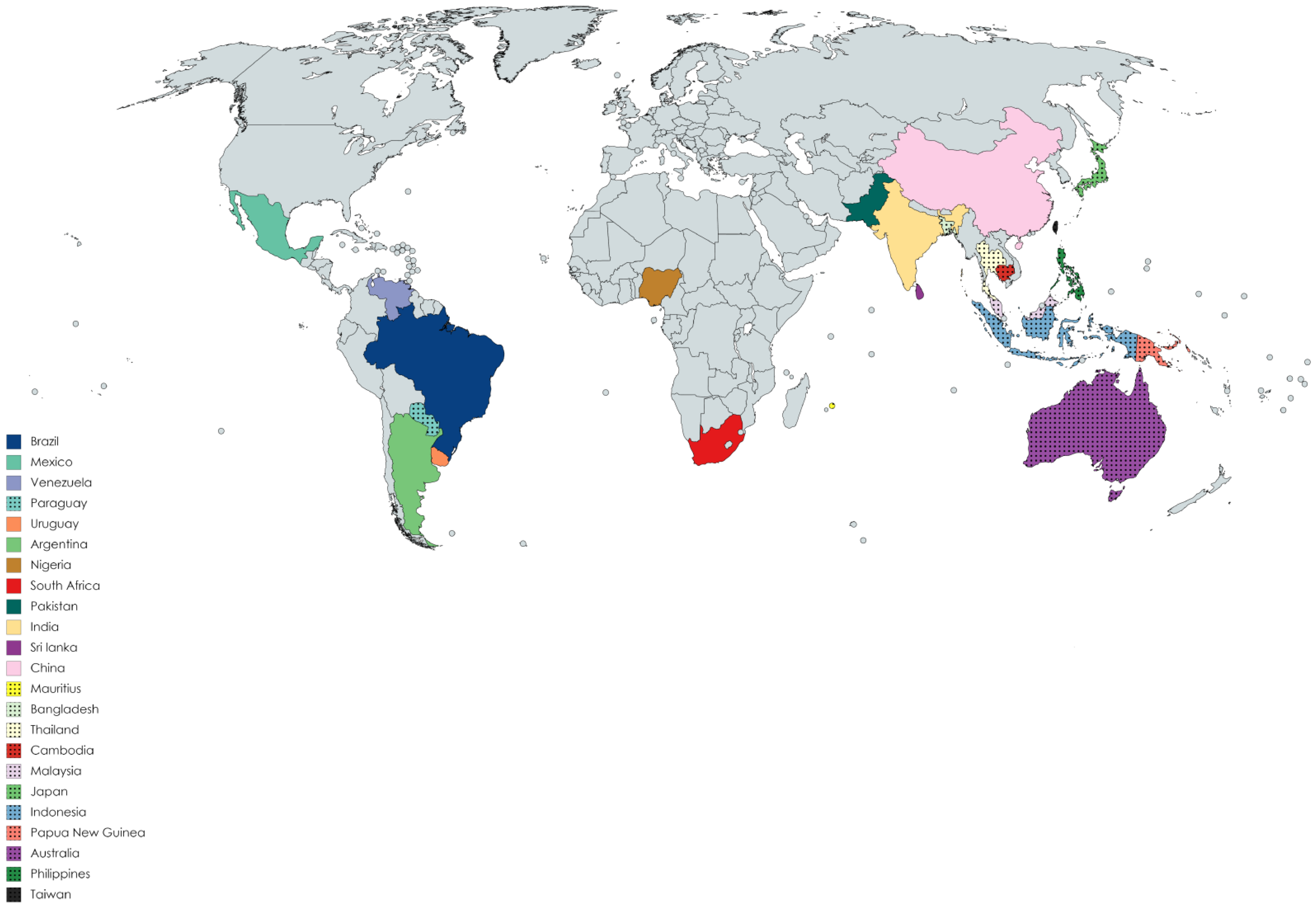

The Mimosa genus belongs to the Fabaceae family of legumes (subfamily: Mimosoideae) and consists of almost 400 species of shrubs and herbs [1]. The species are distributed mainly in Bangladesh, Indonesia, Malaysia, Japan, India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, China, Cambodia, Taiwan, Africa (Nigeria, Mauritius, and Reunion Island), Australia, Brazil, Venezuela, Mexico, Philippines, Cuba, northern Central America, Paraguay, Argentina, Uruguay, Thailand, several Pacific Islands, Papua New Guinea, and North America [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. Figure 1 presents the ethnogeographical distribution of the Mimosa species in different countries of the world. Almost 20–25 species of this genus are well known to the world, including Mimosa tenuiflora (Wild.) pior, Mimosa pudica L., Mimosa pigra L., Mimosa caesalipiniifolia Benth., Mimosa hamata Willd., Mimosa diplotricha Sauvalle, Mimosaa xanthocentra Mart., Mimosa artemisiana Heringer and Paula, Mimosa invisa Mart. ex Colla, Mimosa scabrella Benth., Mimosa somnians Humb. and Bonpl. ex Willd., Mimosa bimucronata (DC.) Kuntze, Mimosa verrucosa Benth., Mimosa arenosa (Willd.) Poir., Mimosa humilis Willd., Mimosa rubicaulis Lam., Mimosa linguis, and M. albida Willd. Mimosa ophthalmocentra Mart. ex Benth. (http://mpns.kew.org/MPNS.kew.org 2018; www.theplantlist.org 2017) (Accessed on 18 May 2021). Leaves of this genus may be bipinnate or binate, compound or branched, with one or two pairs of branchlets or much larger branched leaves. Some species have the ability to fold their leaves when touched, with M. pudica being one common example. The flowers may be pink and globular in the form of clusters and with prickles or may be white and grouped in dense heads 3–6.5 mm long. The fruit are lance-shaped with 2–6 articulations. The fruit wall is compressed between the seeds. Huge amounts of starch and calcium oxalate crystals are present in the bark [12]. Some species are prickly leguminous shrubs [13]. The plants of this genus usually grow across roadsides, walkways, marshes, and hillsides, and on margins of rivers and lakes on wet soil, where several individuals can form dense aggregations [14]. The plants are commonly used for ornamental purposes. They also serve as sleeping shelters for animals [15]. Economically, their wood is used for fence posts, firewood, coal, plywood, particle board, and lightweight containers, and more recently has been introduced in furniture and flooring [16]. Leaves of the plants are used for poultry diets [17]. In the food industry, the leaves are used as additives, while in the leather and textile industry they are used as colorants [18,19]. The plants provide wood for market purposes and add nitrogen in warm-climate silvopasture systems [20]. This genus has remarkable economic importance in the cosmetics industry [21]. Traditionally, species of this genus are used in folklore medicines for the treatment of various ailments, including head colds, wounds, toothaches, jaundice, eye problems, fever, weak heart, skin burns, asthma, diarrhea, piles, gastrointestinal ailments, liver disorders (such as hepatitis and diuresis), and respiratory [22,23,24,25,26] disorders. They are also used as coagulants and in tonics for urinary complaints. The genus Mimosa has been demonstrated to possess various pharmacological activities, including antiseptic, antimicrobial [27,28], antioxidant [29,30,31,32,33,34], anticonvulsant [35], antifertility [36], antigout [37], anti-inflammatory [38,39,40], antinociceptive [41,42], antiulcer [43], antimalarial [44], antiparasitic [45], antidiabetic [46,47], anticancer [48,49], antidepressant [50], antidiarrheal [51,52], antihistamic [53], wound-healing [54], antispasmolytic [55], hypolipidemic [56], hepatoprotective [57], hypolipidiemic [58], antivenom [40], antiproliferative [59], antiviral [60], and aphrodisiac activities [61]. Phytochemicals studies of plants have revealed the presence of secondary metabolites, such as alkaloids, tannins, flavonoids, terpenoids, saponins, steroids [62,63], and coumarins [64]. The green synthesis of nanoparticles is cheap, simple, comparatively and reproducible, resulting in the production of more stable and useful materials [65]. The Mimosa genus has been used in the green synthesis of pharmacologically important gold [66], silver [67], iron [68], cadmium [69], platinum [70], and zinc oxide [71]-based nanoparticles; however, data regarding all species of the Mimosa genus have not been compared and organized to date in proper review form (to the best knowledge of the authors). Our research group is currently working on compiling data regarding bioactive constituents isolated from the genus Mimosa and their pharmacological effectiveness.

Figure 1.

Ethnogeographical distribution of Mimosa species.

2. Materials and Methods

A detailed bibliographic study that included papers published from 1931 to 2020 was carried out. Several databases (Science Direct, Francis and Taylor, Scopus, Google Scholar, PubMed, SciELO, Web of Science, SciFinder, Wiley, Springer, Google, and The Plant Database) were explored in order to collect information on this genus. Various books, full text manuscripts, and abstracts were consulted. The genus name and the synonyms and scientific names of Mimosa species were used as keywords. The scientific names of all plants of the genus Mimosa and their synonyms were validated using a standard database (http://mpns.kew.org/MPNS.kew.org 2018; www.theplantlist.org 2017) (accessed on 15 May 2021).

3. Nutritional Potential of Genus Mimosa

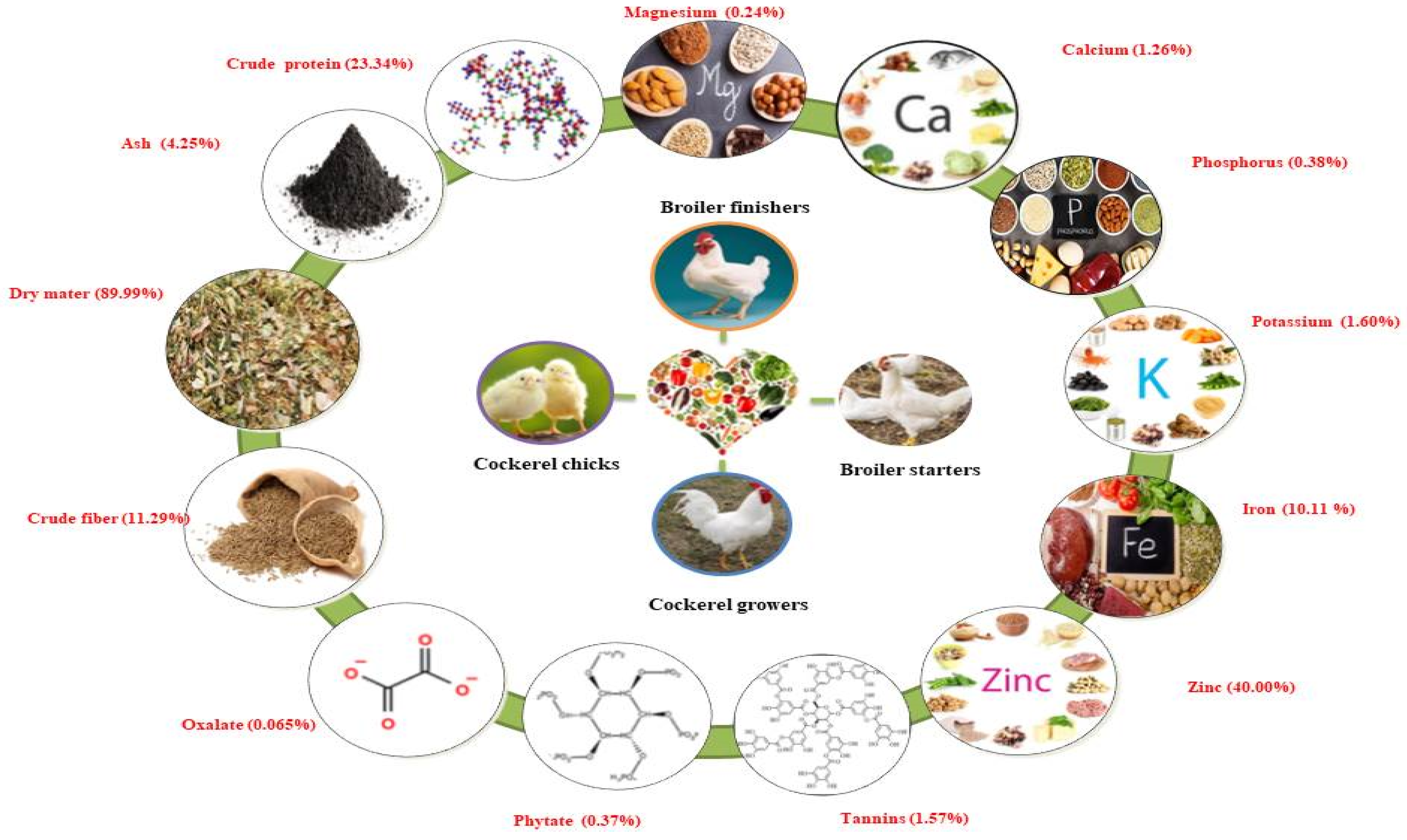

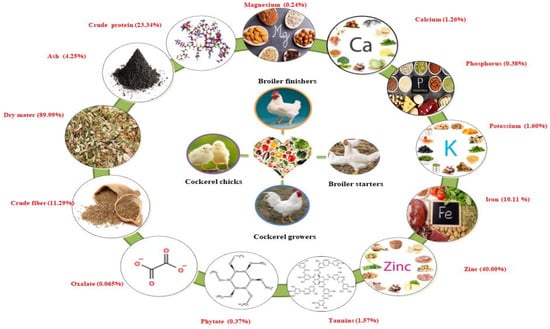

Nworgu and Egbunike [17] reported on the nutritional potential of M. invisa leaves by preparing meals for different varieties of cockerel chicks, cockerel growers, broiler starters, and finishers within the years 2004–2009. The diets were formulated for cockerel chicks, broiler starters, and finishers. Leaves were found to be rich in crude protein (23.34%), ash (4.25%), dry matter (89.99%), crude fiber (11.29%), nitrogen-free extract (58.74%), oxalate (0.065%), phytate (0.37%), and tannins (1.57%). High mineral elements were found in M. invisa leaves, including zinc (40.00% of DM), iron (10.11% of DM), potassium (1.60% of DM), calcium (1.26% of DM), phosphorus (0.38% of DM), and magnesium (0.24% of DM). Inclusion of more than 20 g/kg M. invisa leaf meal to the diets of cockerel chicks and cockerel growers resulted in decreased feed intake, weight gain, and feed conversion ratio. Dietary inclusion of leaf meal in broiler starters and finishers resulted in significant reductions in feed, weight gain, and feed conversion ratio. These results were found to be progressive and comparable within different chicken types. A schematic illustration of the nutritional value of the Mimosa genus is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic presentation of the nutritional value of the Mimosa genus. Note: % represents percentage of dry matter content.

Rajan et al. [72] measured trace elements present in M. pudica leaves with the help of the proton-induced X-ray emission (PIXE) technique. PIXE analysis revealed that trace elements of Fe = 308.467 mg/L, Mn = 65.664 mg/L, Zn =18.209 mg/L, Cu = 10.707 mg/L, Co = 2.025 mg/L, and V= 0.059 mg/L were present in M. pudica leaves. These trace elements are used for curing skin diseases, especially infections on the legs and between the fingers, and are also taken orally. Yongpisanphop et al. [73] estimated lead contamination levels in M. pudica roots. The lead contamination level found to be in the root sample was 826 mg/kg, as compared to 496 mg/kg in the soil sample. There are no reports available regarding the trace elements and mineral compositions of other Mimosa species.

4. Ethno-Traditional Uses of Genus Mimosa

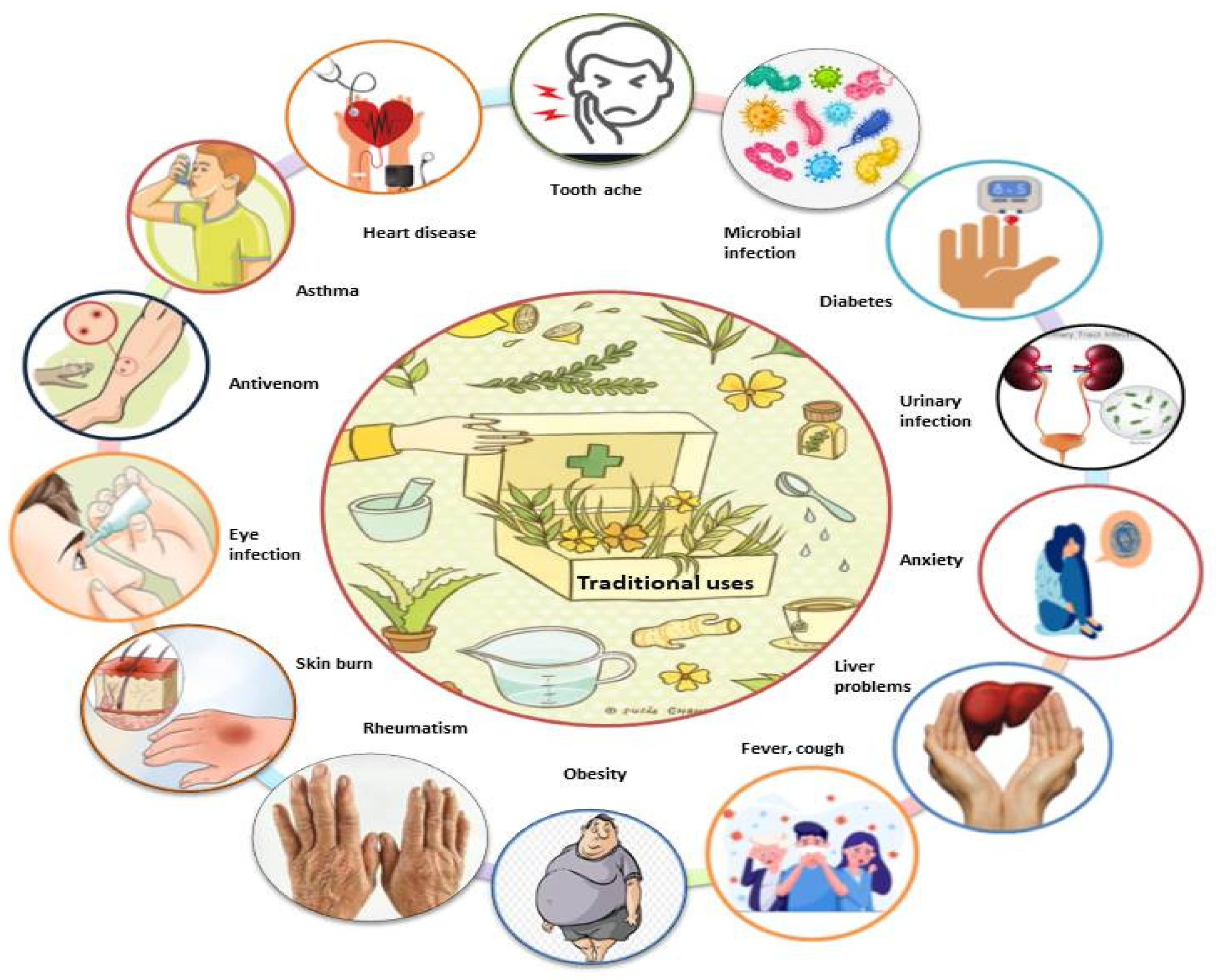

Various species of Mimosa, including M. tenuiflora, M. pudica, M. pigra, M. caesalpiniifolia, M. hamata, M. rubicaulis, M. somnians, M. bimucronata, M. linguis, M. humilis, M. invisa, M. arenosa, M. ophthalmocentra, M. verrucosa, and M. albida, have been reported to be used in traditional medicine for the treatment of various ailments (Figure 3). Due to their potential benefits in phytomedicines, all parts of this genus are used in traditional systems of medicine in Mexico, Brazil, India, Bangladesh, China, Indonesia, Madagascar, South America, and tropical Africa for countless ailments, including toothaches, head colds, and eye problems. M. tenuiflora is a perennial shrub or tree commonly known as skin tree or Jurema-preta in many parts of the world. In Northeastern Brazil, the bark of M. tenuiflora is used in a religious drink called Yurema [74,75], while the leaves, stem, and flowers are used to relieve fever, menstrual colic, headache, hypertension, bronchitis, and coughs [41,55,76,77,78,79,80,81]. In Mexico, its stem bark is used to treat skin burns, lesions, and inflammation [24].

Figure 3.

Schematic illustration of the traditional uses of the genus Mimosa.

M. pudica is a creeping perennial or annual flowering plant and is the most famous plant of this genus; it is commonly known as touch-me-not, sensitive plant, or shy plant. In Mexico, M. pudica is used for the treatment of depression, anxiety, premenstrual syndrome, menorrhagia, skin wounds, diarrhea, and rheumatoid arthritis [50,82,83,84,85]. Ayurveda and Unani are the two main medical systems in India, in which M. pudica leaves and roots are used for prevention of vaginal and uterine infections [86], ulcers, bile, leprosy, fever, small pox, jaundice, and piles [87,88]. The seeds are combined with sugar and used to control skin and venereal diseases [72]. Indians use it for the removal of kidney stone (vesicle calculi) myalgia, rheumatism, uterus tumors, and odema-type disorders [89]. The leaves are commonly used in Bangladesh as one of the ingredients to control piles, diarrhea, persistent dysentery, and convulsion of children [90]; additionally, the root extracts have antivenomic properties [91]. In China, women use its herbal paste in the form of a solution to narrow their vaginas [92], and it is also used as a dental powder to treat gingiva and bad breath [93]. M. pigra is a leguminous shrub known as giant sensitive tree and bashful plant. The people of Africa, the America, Indonesia, and Mexico use M. pigra to deal with several health disorders, such as liver ailments, hepatitis and respiratory disorders [94], and snakebite [95]. It is also used for mouthwash to treat toothaches and in eye medicines [96]. Additionally, the leaves are used by the local people of Bangladesh to lower their blood sugar [97], while Indonesian people use the roasted ground leaves to stabilize a weak heart or weak pulse [98,99].

M. caesalpiniifolia is a spiny, deciduous tree or shrub with white flowers that is commonly found in Brazil. Its bark and flowers are used as an effective remedy to prevent skin infections, injuries [100], and hypertension [77].

M. hamata is a flowering shrub found in India that is known as Jinjani, which is used as animal feed. The roots and leaves are used in customary medications for the treatment of numerous health ailments, such as jaundice, diarrhea, coagulant, fever, wounds, piles, gastrointestinal and liver disorders (such as hepatitis), and respiratory issues [3], as well as being used in tonics for urinary complaints. A paste made from the leaves is applied to reduce glandular swelling, piles, sinus issues, and sores [101,102]. The seed extract is used as a blood purifier [33,103].

M. albida is a leguminous shrub commonly found in rain forests. In Brazil, roots are used for cardiovascular and renal system disorders [104], as well as inflammation of the uterus [105]. In Mexico, the leaves are used for treatment of chronic pain [106]. In Honduras, women use its roots in abortifacient agents [107]. Different species of Mimosa are known by different names in different countries. Ethnobotanical information for this genus based on their geographic distribution, along with the plant parts and their corresponding medicinal properties, are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Ethnotraditional uses of different species of the genus Mimosa.

5. Pharmacological Activities of Genus Mimosa

During the past decades, the genus Mimosa has been extensively studied for its broad biological and pharmacological potential. Different preparations and extracts from this genus have demonstrated multiple health benefits and pharmacological effects, including antimicrobial, antioxidant, anticancer, wound-healing, hypolipidemic, anti-inflammatory, hepatoprotective, antinociceptive, antiepileptic, neuropharmacological, toxicological, antiallergic, antihyperurisemic, larvicidal, antiparasitic, molluscicidal, antimutagenic, genotoxic–teratogenic, antispasmolytic, antiviral, and antivenom activities. These pharmacological effects have been studied through in vitro and in vivo assays. These activities are presented in detail in this review article (Table 2).

Table 2.

Pharmacological studies of different species of the genus Mimosa.

5.1. Antimicrobial Activity

Valencia-Gómez et al. [129] determined the antibacterial activity of biofilms made from chitosan and M. tenuiflora bark. Composite biofilms in different concentrations (100:0, 90:10, 80:20, and 70:30) successfully inhibited the growth of E. coli and M. lysodeikticus. Souza-Araújo et al. [130] measured the antimicrobial activity of pyroligneous acid (PA) obtained from slow pyrolysis of wood of M. tenuiflora against E. coli, P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, C. albicans, and C. neoformans using the agar diffusion method. The growth of all microorganisms was inhibited by pyroligneous acid at different tested concentrations (20, 50, and 100%), whereas gentamicin was used as a standard drug. The antimicrobial potential of EtOH (95%) extract of M. tenuiflora bark against different bacterial and fungal strains has been reported. Active doses of the extract inhibited the growth of E. coli, B. subtilis, M. luteus, and P. oxalicum. Gonçalves et al. [131] reported the antimicrobial potential of the hydroalcoholic extract of M. tenuiflora bark against various bacterial strains using the agar well diffusion method. The results revealed that the extract successfully inhibited the growth of S. pyogenes, P. Mirabilis, S. sonnei, S. pyogenes, and Staphylococcus spp. Padilha et al. [132] described the antibacterial activity of the EtOH extract of M. tenuiflora stem bark against S. aureus by using the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) with the agar dilution method and time-kill assay. At concentrations up to 4x MIC, only a bacteriostatic effect was observed, while at 8.x MIC a fast bactericidal effect was observed [133]. The minimum inhibitory concentration shown by active doses of 95% M. tenuiflora EtOH extract against S. epidermidis and A. calcoaceticus were >10.0 μg/mL, S. aureus and M. luteus = 10.0 μg/mL, E. coli and K. pneumonia = 20.0 μg/mL, and C. albicans = 70.0 μg/mL [134]. The antimicrobial potential of BuOH, MeOH, and EtOAc extracts of M. tenuiflora bark against S. aureus, E. coli, and C. albicans has been reported [135]. De Morais-Leite et al. [136] determined the antibacterial potential of the EtOH extract of M. tenuiflora bark via the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and the minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) values against S. aureus (ATCC 25.925 and ATCC 25.213), E. coli (ATCC 8859 and ATCC 2536), and P. aeruginosa (ATCC 25.619). S. aureus (ATCC 25.925) and P. aeruginosa (ATCC 25.619) showed MIC and MBC values of 128 and 256 μg/mL, respectively, while S. aureus (ATCC 25.213) showed MIC = 512 and MBC = 1024 μg/mL. For E. coli (ATCC 8859) and E. coli (ATCC 2536), the observed values were MIC = 1024 and MBC ˃1024 μg/mL. Silva and his colleagues reported on the antimicrobial potential of the EtOH extract of M. tenuiflora bark using the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values against S. aureus, E. coli, C. albicans, and T. interdigitale. Lower MIC values were observed against S. aureus [137].

Racadio [116] and Molina [117] reported on the antimicrobial activity of the EtOH extract of M. pudica leaves against S. aureus, B. subtilis, and C. albicans using the Kirby–Bauer disc diffusion method. Inhibition zones were observed against S. aureus = 21.8 mm (4.61%), B. subtilis = 23.7 mm (9.56%), and C. albicans = 6.1 mm (1.96%). Nagarajan et al. [139] determined the antibacterial activity of Aq. extracts of M. pudica leaves and stems against E. coli, staphylococcus sp., Bacillus sp., Pseudomonas sp., and Streptococci sp. by disc diffusion method. Zones of inhibition were observed against order E. coli (18 mm) > Bacillus sp. (12.5 mm) > Pseudomonas sp. (12 mm) > Staphylococcus sp. (11 mm) > Streptococcai sp. (9 mm). Abirami et al. [139] reported on the antimicrobial potential of extracts (ACE, EtOAc, petroleum ether, and Aq.) of M. pudica leaves using the well diffusion method. The antimicrobial efficacy levels of all of the extracts were determined against E. coli, P. aeurogiosa, L., Bacillus, S. typhi, S. aureus, P. foedians, F. oxysporum, and P. variotii at different concentrations of 30, 60, 90, and 120 μL/mL. ACE extract showed a maximum zone of inhibition against S. aureus, while Aq. extract showed a maximum activity against E. coli. Petroleum ether showed a higher zone of inhibition against S. typhi. Durgadevi and Karthika [62] determined the antimicrobial potential of Aq. extract of M. pudica leaves by using the agar well diffusion method against B. cereus, E. coli, P. valgaris, P. auroginosa, S. aureus, A. flavus, A. niger, A. terreus, Fusarium sp., and Penicillium sp. at different concentrations (25, 50, 75 and 100 mg). The extract showed significant zones of inhibition at 100 mg concentration. Sheeba et al. [140] determined the antibacterial activity of the MeOH extract of M. pudica leaves using the disc diffusion method against P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, and V. harveyi. The plant extract showed zones of inhibition against S. aureus (10.66 mm), P. aeruginosa (8.66 mm), and V. harveyi (8.00 mm), while ampicillin was used as the standard antibiotic. Sheeba et al. [140] determined the antimycobacterial activity of MeOH extracts of M. pudica leaves against M. tuberculosis using disc diffusion and agar well diffusion methods. Extract exhibited a zone of inhibition against M. tuberculosis (disc diffusion = 7.00 mm; agar well diffusion method = 4.33 mm). Kakad et al. [141] determined the antibacterial activity of MeOH extract of M. pudica leaves against two Gram-positive (B. subtilis, S. aureus) and three Gram-negative (P. aeroginosa, P. vulgaris, and S. typhi) bacterium using the agar well diffusion method. Significant results were obtained and data were compared with the standard antibiotics penicillium (100 μg/disc) and gentamicin (10 μg/disc). Muhammad et al. [82] measured the antifungal activity of extracts (EtOH and Aq.) of M. pudica leaves against T. verrucosum, M. ferrugineum, T. shoenleinii, T. rubrum, M. canis, T. concentricum, T. soudanense, and M. gyseum at four different concentrations (150, 200, 250, and 300 mg). T. verrucosum, M. ferrugineum, T. shoenleinii, M. canis, T. soudanense, and M. gyseum were sensitive to EtOH extract.

Thakur et al. [142] determined the antimicrobial activity of hydroalcoholic extract of M. pudica leaves against E. coli, S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, and B. cereus using the disc diffusion method. The extract showed significant results at 25, 50, and 100 mL/disk concentrations. Le Thoa et al. [143] measured the antibacterial activity of Aq. and EtOH extracts of M. pudica leaves and stems using the agar well diffusion method. The EtOH extract showed significant zones of inhibition against different strains (E. coli = 11 mm, S. aureus = 19 mm, B. cereus = 17 mm, S. typhi = 16 mm), while the Aq. extract significantly inhibited S. aureus = 14 mm and B. subtilis = 15 mm. The results were compared with standard chloramphenicol. Dhanya and Thangavel [144] measured the antimicrobial potential of MeOH extracts of M. pudica leaves, flowers, and roots against S.aureus, E. coli, and Pseudomonas sp. using the disc diffusion method. Zones of inhibition shown by the extract of the leaves in decreasing order were: S. aureus (23.5 mm) > E. coli (20 mm) > Pseudomonas sps (14 mm). The flower extract showed activity against Pseudomonas sp. 22.5 > E. coli 14 > S. aureus 12 mm. The root extract also showed significant activity against R. solani (29 mm) > A. niger (21 mm) > M. phaseolina (17.7 mm). Ahuchaogu et al. [145] screened the antimicrobial potential of the EtOH extract of M. pudica whole plant against S. aureus, P. aeroginosa, E. coli, M. smegmatis, and E. faecalis at various concentrations (25, 50, and 100 mg/disc). At 100 mg/disc, maximum antimicrobial activity was observed and a comparison was made with standard chloramphenicol. Chukwu et al. [146] determined the antimicrobial activity of absolute EtOH extract of M. pudica whole plant against the tested microorganisms (A. flavus and T. rubrum) at three different concentrations (25, 50, and 100 mg/mL). At 100 mg/mL, the extract was very found to be highly active against A. flavus and T. rubrum (100 mg/mL = 22 and 17 mm, respectively). Rosado-Vallado et al. [23] screened the antimicrobial potential of MeOH and Aq. extracts of M. Pigra leaves against various microorganisms (S. aureus, E. coli, P. aeruginosa, B. subtilis, A. niger, and C. albicans) using the agar–well diffusion method. Itraconazole (0.025 mg/µL), nystatin (50 IU/mL), and amikacin (0.03 mg/mL) were used as positive controls for bacteria, yeast, and fungi. Both plant extracts were found to be active against P. aeruginosa, C. albicans, S. aureus, and B. subtilis and inactive against E. coli and A. niger. De Morais et al. [147] determined the antifungal activity of 60% MeOH, DCM, and EtOAc fractions of M. pigra leaves by measuring the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values against dermatophyte strains (T. mentagrophytes, E. floccosum, M. gypseum, and T. rubrum). The MeOH extract showed the lowest MIC values against all dermatophytes (1.9 to 1000 mg/mL). DCM, EtOAc, and Hex fractions showed significant results. Jain et al. [60] determined the in vitro antimicrobial activity of EtOH extracts and fractions (Aq., CF, PE, and BZ) of M. hamata whole plant against E. coli, K. pneumonia, P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, P. vulgaris, A. flavus, F. moniliforme, and R. bataticola by disc diffusion method. At 500 mg/disc, the EtOH extract and Aq. fraction inhibited the growth of all bacteria and fungi, although the activity of the Aq. fraction was less than that of the EtOH extracts. PE was found to be active against fungi. Ali et al. [148] measured the antimicrobial activity of crude Hex and MeOH extracts of M. hamata whole plant. The Hex extract showed potent % growth inhibition against B. cereus (29.75%), C. diphteriae (1.40%), P. aeroginosa (74.11%), A. niger (30.50%), M. canis (36.21%), and M. phaseolina (89.95%), while the MeOH extract also showed potent activity against B. cereus (59.49%), C, diphteriae (30.16%), E. coli (6.31%), S. sonii (73.13%), P. aeroginosa (32.74%), S. typhi (16.84%), S. pyogenes (57.18%), T. longifuses (67.26%), P. boydii (95.10%), M. canis (45.31%), T. simii (75.00%), F. solani (54.75%), and T. schoenleinii (84.18%). Standard ampicillin and rifampicin showed 99–100% growth inhibition. Mahmood et al. [5] investigated the antimicrobial potential of crude MeOH extract of M. pigra leaves against E. coli, B. subtilis, P. aeruginosa, K. pneumonia, A. niger, and A. flavus by agar tube diffusion and agar tube dilution methods for bacteria and fungi, respectively. The plant showed significant inhibition of E. coli, P. aeruginosa, and K. pneumonia bacteria and minor activity against B. subtilis, while no activity was observed against fungi. Silva and his colleagues reported the antimicrobial potential of the EtOH extracts of M. verrucosa and M. pteridifolia bark via the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values against S. aureus, E. coli, C. albicans, T. interdigitale. M. verrucose, and M. pteridifolia, showing lower MIC values of 250 μg/mL and 500 μg/mL, respectively, against S. aureus [137] (Table 2).

5.2. Antioxidant Activity

Magalhães et al. [149] determined the antioxidant potential of the EtOH extract and various fractions (n-hex, DCM, EtOAc, and HyOH) of M. tenuiflora leaves, twigs, barks, and roots using DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging activities. The EtOH extract showed the lowest EC50 values against DPPH (EC50 = 132.99 μg/mL) and ABTS (EC50 = 189.14 μg/mL) radicals. The EtOAc fraction proved to have potent antioxidant activity against DPPH (EC50 = 141.20 μg/ mL) and ABTS (EC50 = 273.00) radicals. Silva and colleagues determined the antioxidant potential of the EtOH extract of M. tenuiflora bark using DPPH and ABTS scavenging assays. The plant showed potent scavenging effects against DPPH and ABTS radicals, with IC50 values of 17.21 and 3.57 μg/mL, respectively. The results were compared with Trolox [137]. Almalki [30] reported the antioxidant potential of M. pudica leaves (Hex extract) by using the DPPH, hydroxyl, nitric oxide, and superoxide radical scavenging assays. The extracts showed significant scavenging effects at concentrations between 5 and 25 mM against DPPH (IC50 = 20.83 mM), hydroxyl (IC50 = 19.37 mM), nitric oxide (IC50 = 21.62 mM), and superoxide (IC50 = 22.19 mM) radicals, while the standards butylated hydroxytoluene and vitamin C showed excellent antioxidant potential as compared to the plant extract. Lee et al. [150] determined the antioxidant potential of hydrophilic extracts (ACE-Aq.-AA (8.0 mL, 70:29.5:0.5) of M. pudica leaves using oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORAC) and DPPH free radical scavenging assays. The extract showed significant results in the ORAC (1187.9 = μmol TE g−1 FW) and DPPH (EC50 = 243.2 mg kg−1) assays, while the total vitamin C content was found to be 259 μg/g FW. Durgadevi and Karthika [62] measured the antioxidant activity of the Aq. extract of M. pudica leaves using the H2O2 scavenging assay. Different concentrations (0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1.0%) of the extract showed (34.6, 39.4, 49.6, 54.6, and 58.3%) significant antioxidant activity. The results were compared with standard thiobarbituric acid. Das et al. [151] determined the antioxidant potential of the MeOH extract of M. pudica leaves via DPPH free radical scavenging assay. The IC50 values of extracts and ascorbic acid were found to be 126.71 and 20.13 μg/mL, respectively, while the total antioxidant capacity of the extract was IC50 = 5.038 mg/g AAE. Chimsook [152] screened the antioxidant activity levels of PE, EtOAc, absolute EtOH, and Aq. extract of M. pudica leaves using ABTS assay. The extracts showed significant results (EC50; PE = 40.6, EtOAc = 27.2, absolute EtOH = 73.8, Aq. = 13.2 μg/mL), while standard ascorbic acid showed EC50 = 11.5 μg/mL. Parmar et al. [31] screened the antioxidant activity of the HyEtOH extract and L-mimosine compound of M. pudica whole plant (stems, leaves, roots, and flower buds) using the DPPH free radical scavenging assay. L-mimosine treatment exhibited lower antioxidant activity than the extract.

Jose et al. [153] screened the in vitro antioxidant activity of isolated flavonoids from EtOAc-soluble fractions of M. pudica whole plant by using DPPH and hydroxyl radical scavenging assays. Significant DPPH radical scavenging was observed (IC50 = 56.32 μg/mL) as compared to the reference standard (ascorbic acid IC50 = 21.11 μg/mL). The isolated flavonoid also showed significant % inhibition at concentrations of 20–140 µg/mL, while ascorbic acid showed significant % inhibition. Ittiyavirah and Pullochal [154] measured the antioxidant activity of the EtOH extract of M. pudica whole plant by using H2O2 and superoxide scavenging assays. The plant showed significant H2O2 scavenging (IC50 = 19 mg/mL), while standard ascorbic acid showed IC50 = 5.2 mg/mL. Significant superoxide scavenging was also observed (IC50 = 80.4 mg/mL) and gallic acid was used as the standard (IC50 = 50.10 mg/mL). Tunna et al. [46] determined the antioxidant potential of the MeOH extract and fractions (n-hex, EtOAc, ACE, and MeOH) of M. pudica aerial parts using the DPPH free radical scavenging assay. The plant showed significant DPPH radical scavenging and the results were compared with standard ascorbic acid (IC50 = 20.13 μg/mL). Silva et al. [32] measured the total phenol and antioxidant potential of the EtOH extract and EtOAc fraction of M. caesalpiniifolia leaves using the DPPH free radical scavenging assay. The results for the total phenol and antioxidant activity showed a concentration of 46.8 g gallic acid eq./kg with an antioxidant activity of 35.3 g vitamin C eq./kg in the EtOH extract and 71.50 g gallic acid eq./kg with an antioxidant activity of 65.3 g vitamin C eq./kg in the EtOAc fraction. Rakotomalala et al. [155] determined the antioxidant capacity of the HyMeOH extract of M. pigra leaves using DPPH free radical scavenging activity and oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORAC) assays. The extract showed significant antioxidant potential (DPPH = 1268 and ORAC = 2287 µmol TE/g) as compared to the standard drugs chlorogenic acid (DPPH = 2927 and ORAC = 11.939 µmol TE/µmol) and quercetin (DPPH = 6724 µmol TE/µmol and ORAC = 22,218 µmol TE/µmol).

Saxena et al. [29] determined the in vitro antioxidant properties of the EtOH extract and sub-fractions (EtOAc and diethyl-ether) of M. hamata whole plant using DPPH free radical and H2O2 scavenging assays. The EtOH extract (76.01%) and EtOAc and diethyl-ether sub-fractions (96.63%) showed % inhibition of DPPH scavenging at 100 μg/mL concentration, while the standard drug ascorbic acid showed 93.52% inhibition. The EtOH extract (67.81%) and EtOAc and diethyl-ether sub-fractions (88.43%) showed significant H2O2 scavenging activity at 100 μg/mL. The results were compared to the standard drug ascorbic acid (86.87%). Chandarana et al. [33] determined the antioxidant potential of cycloHex, EtOAc, and MeOH extracts of M. hamata stem using DPPH free radical and ABTS scavenging assays. The MeOH (IC50 = 0.70 μg/mL), EtOAc (IC50 = 0.85 μg/mL), cycloHex (IC50 = 0.95 μg/mL) extracts showed significant DPPH free radical scavenging as compared to standard ascorbic acid (IC50 = 0.60 μg/mL). In the ABTS scavenging assay, the MeOH extract showed the highest scavenging activity (IC50 = 0.35 μg/mL), followed by EtOAc (IC50 = 0.37 μg/mL) and cycloHex extracts (IC50 = 0.40 μg/mL), while the standard drug ascorbic acid showed the highest activity (IC50 = 0.32 μg/mL). Singh et al. [156] screened the antioxidant activity levels of PE, CF, BuOH, and Aq. extracts of M. hamata (stem, leaves, roots, and seeds) using a DPPH free radical scavenging assay. Different extracts of M. hamata showed significant DPPH scavenging levels, as represented by IC50 values (leaves, 51.30–56.50 μg/mL; stem, 51.80–61.80 μg/mL; roots, 26.33–73.16 μg/mL; seeds, 16.60–51.16 μg/mL). Jiménez et al. [157] determined the antioxidant activity of M. albida whole plant with the help of various assays (DPPH radical scavenging, ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP), Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity (TEAC), oxygen radical absorption capacity (ORAC), LDL-C oxidation inhibition). The plant showed significant antioxidant potential in various assays (DPPH = 1540 µmol TE/g, FRAP = 1070 µmol TE/g, TEAC = 1770 µmol TE/g, ORAC = 1870 µmol TE/g). The LDL-C oxidation inhibition assay showed greater than 50% inhibition at 100 µg/mL concentration of the extract. Manosroi et al. [127] investigated the antioxidant efficacy of the Aq. extract of M. Invisia leaves using a DPPH free radical scavenging assay. M. invisa showed significant free radical scavenging activity (IC50 = 0.119 mg/mL), which was 0.49-fold that of the positive control (ascorbic acid). Silva and colleagues determined the antioxidant potential of the EtOH extract of M. verrucosa and M. pteridifolia bark using DPPH and ABTS scavenging assays. The plant showed potent scavenging effects against DPPH and ABTS radicals, while Trolox was used as the standard antioxidant [137]. (Table 2).

5.3. Anticancer Activity

Valencia-Gómez et al. [129] screened the cytotoxicity of biocomposite films made from M. tenuiflora cortex and chitosan against (3T3) fibroblasts using MTT assays. Chitosan–M. tenuiflora films at different concentrations (100:0, 90:10, 80:20, and 70:30) were used. The cells decreased significantly in the 90:10 and 80:20 chitosan–M. Tenuiflora films. Cytotoxicity increased for high–concentration M. tenuiflora (70:30) and chitosan films (100:0). Silva and colleagues reported on the cytotoxicity of M. tenuiflora bark EtOH extract against four human cancer cell lines (HL-60, HCT-116, PC-3, and SF-295). No activity was observed against any tested cancer lines up to 50 μg/mL concentration [137]. Chimsook [152] reported on the in vitro anticancer activity levels of different extracts (PE, EtOAc, absolute EtOH, and Aq.) of M. pudica leaves against three human cancer cell lines derived from lung (CHAGO), liver (HepG2), and colon (SW620) samples using an MTT assay. The EtOAc extract was found to be potent (IC50 = 29.74 μM) against CHAGO cells, while the EtOAc and absolute EtOH extracts inhibited the SW620 cells, with IC50 values of 11.12 and 5.85 μM, respectively. HepG2 cell growth was inhibited by EtOAc (IC50 = 29.81 μM) and absolute EtOH (IC50 = 10.11 μM) extracts. The results were compared with standard amonafide, which showed significant cytotoxicity in CHAGO (IC50 = 1.05 μM), SW620 (IC50 = 0.32 μM), and HepG2 (IC50= 1.71 μM) cell lines. Parmar et al. [31] screened the anticancer activity of the Hy-EtOH extracts of M. pudica whole-plant samples (stems, leaves, roots, and flower buds) and L-mimosine using MTT assay against the Daudi cell line. At concentrations of 12.5–400 μg/mL, the IC50 values were found to be 201.65 μg/mL and 86.61 μM at 72 h for M. pudica extract and L-mimosine, respectively. Rakotomalala et al. [155] screened the cell viability and proliferation of smooth muscle in male Wistar rats from HyMeOH extract of M. pigra leaves using an MTT assay. No significant effects were observed by the extract (at a concentration of 0.01 to 1 mg/mL) on smooth muscle cell proliferation or cell viability. Saeed et al. [98] measured the antitumor activity of M. pigra fruit extract via oral administration. This plant has been used by Sudanese healers against tumors.

Silva et al. [158] screened the anticancer activity of an EtOH extract of M. caesalpiniifolia leaves against the human breast cancer cell line MCF-7 by using the SRB assay. The extract at 5.0 μg/mL for 24 h the reduced protein (50%) and cyclophosphamide (30%) contents, while treatment for 48 h reduced protein to 80% and cyclophosphamide to 55%, with the extract showing maximum effect at 320.0 μg/mL, which demonstrates that the extract exhibited cytotoxic effect against MCF-7 cells. Monção et al. [49] reported on the anticancer activity of an EtOH extract and fractions (n-Hex, DCM, EtOAc, and Aq.) of M. caesalpiniifolia stem bark using an MTT assay against HCT-116, OVCAR-8, and SF-295 cancer cells. The percentage inhibition of cell proliferation for the EtOH extract and n-Hex fraction varied from 69.5% to 84.8% and 65.5% to 86.4%, respectively, while the DCM fraction and betulinic acid showed inhibition levels above 86.5% and doxorubicin (at 0.3 μg/mL) >83.0%. EtOAc and Aq. fractions showed minimal inhibition of cell proliferation. Nandipati et al. [122] determined the cytotoxicity of the MeOH extract of M. rubicaulis stem against an Ehrlich ascites carcinoma (EAC) tumor model in Swiss albino mice against cancer cell lines (such as EAC, MCF-7, and MDA-MB 435S) using an XTT assay. The extract at a concentration of 200 µg/mL reduced the cytotoxicity of the cell lines (EAC 78.3%, MCF-7 = 79%, MDA-MB 435S = 83%), while standard amoxifen exhibited maximal cytotoxic effects on EAC (99.3%), MCF-7 (95.5%), and MDA-MB 435S (99.4%) cell lines. They also measured the antitumor activity of the M. rubicaulis (MeOH extract) against an Ehrlich ascites carcinoma (EAC) tumor model in Swiss albino mice who received 100, 200, and 400 mg/kg bw by measuring hematological parameters IRBC, WBC, hemoglobin, and PCV). At a dose of 400 mg/kg, the level of WBC increased while decreases in RBC and PCV were observed as compared to the standard drug 5-FU 20 mg/kg ip. Silva and colleagues reported on the cytotoxicity of M. verrucosa and M. pteridifolia bark EtOH extracts against four human cancer cell lines (HL-60, HCT-116, PC-3, and SF-295). No activity was observed against any of the tested cancer lines up to 50 μg/mL concentration [137] (Table 2).

5.4. Antidiabetic Activity

Tunna et al. [46] investigated the antidiabetic potential of MeOH extract and fractions (Hex, EtOAc, ACE, and MeOH) of M. pudica aerial parts using α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory assays. The percentages of inhibition in α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory assays shown by the MeOH extract were found to be 33.86% and 95.65%, while the fractions also showed potent inhibitory effects (Hex = 10.583% and 0.884%, EtOAc = 18.65% and 51.87%, ACE = 15.64% and 16.04%, MeOH = 27.21% and 4.83%). Standard acarbose showed 28.24 and 36.93% inhibition effects, respectively. This study has proven the strong antidiabetic activity of tested extracts, which could lead to future studies with respect to obtaining new antidiabetic agents from M. pudica. Piyapong and Ampa [159] screened the hypoglycemic activity of 80% EtOH extract of M. pudica whole plant in diabetic male albino Wistar rats using an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) and fasting blood glucose test (FBG). In the OGTT, after 30 min of extract administration, the extract (500 mg/kg bw) did not decrease blood glucose (572.83 mg/dL) in diabetic rats as compared to standard glybenclamide (0.5 mg/kg bw = 473.50 mg/dL). In the FBG test, after 1 week of administration, the extract (500 mg/kg bw) decreased the blood glucose level to 421.00 mg/dL, while standard glybenclamide (0.5 mg/kg bw) also significantly decreased blood glucose level (572.67 mg/dL). Konsue et al. [160] determined the antidiabetic activity of Aq. and HyEtOH extracts of M. pudica whole plant in diabetic male albino Wistar rats using fasting blood glucose levels (FBG) and hematological values, including red blood cell (RBC), white blood cell (WBC), hemoglobin (Hb), platelet, hematocrit (Hct), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC) counts, as well as differential white blood cell, lymphocyte, monocyte, neutrophil, and eosinophil counts, at three different concentration (125, 250, and 500 mg/kg bw). At 250 mg/kg bw concentration, Aq. (517.00 mg/dL) and HyEtOH (484.00 mg/dL) extracts significantly decreased fasting blood glucose levels. The results were compared with standard glibenclamide. No effect was observed on RBC, Hb, Hct, platelet, MCH, MCHC, lymphocytes, monocytes neutrophils, or eosinophils, while in diabetic rats the WBC and MCV were decreased by the extract. From this study, it was concluded that use of M. pudica Aq. extract could be a potential method of diabetes prevention. Lee et al. [150] determined the enzymatic activity of hydrophilic extracts (ACE–Aq.-AA (8.0 mL, 70:29.5:0.5)) of M. pudica leaves using α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory assays. M. pudica showed significant inhibition of α-amylase (189.3 μmol AE/g) and α-glucosidase (6.6 μmol AE/g). Acarbose was used as the positive control and statistically significant results were obtained.

Manosroi et al. [127] determined the hypoglycemic activity of M. invisa leaves (Aq. extract) in normoglycemic and diabetic male ICR mice. Alloxan monohydrate at 75 mg/kg bw was injected into the mouse tail vein. After the 3rd day, diabetes was confirmed and various doses (100, 200, and 400 mg/kg bw) of the plant extract were orally given to the 18-h-fasted normal and diabetic mice. Insulin and glibenclamide were used as standards and hypoglycemic effect was measured by decreased fasting blood glucose (FBG). M. invisa significantly reduced the fasting blood glucose (FBG) by 14.84% in normoglycemic mice at 1 h with the 200 mg/kg bw dose, which was 0.24- and 0.47-fold the values for insulin and glibenclamide, respectively. M. invisa also showed significant FBG reductions of 16.60% and 9.28% at doses of 100 and 400 mg/kg bw at 240 min, which were 0.27- and 0.52-fold the values for insulin and 0.15- and 0.29-fold the values for glibenclamide, respectively. In diabetic mice, M. invisa only showed a significant reduction in fasting blood glucose (FBG) of 25.01%, at 180 min with the lower dose of 100 mg/kg bw, which was 0.35-fold that of insulin and 0.55-fold that of glibenclamide, respectively. Ahmed et al. [97] determined the glucose tolerance properties of the MeOH extract of M. pigra stem in Swiss albino male mice using the glucose oxidase method. Mice orally received different concentrations of extract (50, 100, 200 and 400 mg/kg/bw) and standard drug glibenclamide (10 mg/kg/bw). After 1 h, all mice orally received 2 g glucose/kg bw. All doses of the extract decreased the concentration of glucose almost 37.84, 39.83, 42.39, and 50.50%, respectively, while glibenclamide reduced the concentration of glucose almost 56.33%. Ao et al. [161] screened the antihyperglycemic activity of the EtOH extract of M. pigra roots in albino rats by checking fasting blood glucose (FBG) levels. Diabetes was induced through intraperitoneal injection (160 mg/kg) of alloxan monohydrate. Diabetic albino rats orally received EtOH extract (250 and 500 mg/kg) and glibenclamide (10 mg/kg). In an acute study, administration of the extract at 250 mg/kg concentration showed a significant blood glucose reduction (360.00 mg/dL), while at the 500 mg/kg dose no significant results (391.80 mg/dL) were obtained as compared to diabetic untreated mice; however, the extract showed a significant hypoglycemic effect, while the glibenclamide showed no significant reduction in blood glucose. During prolonged treatment, a fluctuation was observed in the blood glucose levels of the diabetic treated albino rats. The extract (250 and 500 mg/kg) showed a reduction in blood glucose levels (Table 2).

5.5. Wound Healing

Choi et al. [162] measured the wound-healing effects of a herbal mixture of M. tenuiflora leaves (20%) and A. vulgaris (20%) on human keratinocyte (HaCaT), umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), and mouse fibroblast (3T3-L1) using a scratch test. Fusidic acid was used as the standard. According to the histological study, synthesis of collagen, re-epithelialization, and re-generation of appendages of skin and hair follicles were promoted by the herbal mixture. Immunohistochemical studies showed that blood vessel stabilization, improvement of angiogenesis, and accelerated granulation tissue formation were also achieved through use of the herbal mixture. The herbal mixture can also promote the migration of keratinocytes, endothelial cells, and fibroblasts and the proliferation of macrophages and lymphatic vessels; therefore, the herbal mixture can be used therapeutically for the treatment of cutaneous wounds. Zippel et al. [108] screened the wound-healing efficiency of Aq. extracts and EtOH-precipitated compounds from M. tenuiflora bark by measuring the mitochondrial (MTT, WST-1), proliferation (BrdU incorporation), and necrosis (LDH) activities on human primary dermal fibroblasts and HaCaT keratinocytes. The Aq. extract (10 and 100 µg/mL) caused loss of cell viability and proliferation in dermal fibroblasts, while the EtOH-precipitated compound EPC (10 µg/mL) significantly stimulated mitochondrial activity and proliferation of dermal fibroblasts and showed minor stimulation on human kerationocytes at 100 µg/mL. Molina et al. [50] measured the wound-healing activity of 10% powder of M. tenuiflora bark in adult humans for external use. The results were found to be significant for inflammation and venous leg ulceration diseases. Arunakumar et al. [163] reported on the wound-healing activity of the MeOH extract of M. tenuiflora whole plant by using a chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) model in 9-day-old fertilized chick eggs. The extract increased the numbers of capillaries on the treated CAM surfaces, which might be beneficial for wound healing. Rivera-Arce et al. [24] determined the therapeutic effectiveness of the M. tenuiflora cortex extract in the treatment of venous leg ulceration disease. Patients received a hydrogel containing 5% crude extract standardized in a tannin concentration (1.8%). A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial was conducted. Therapeutic effectiveness was achieved in all patients in the extract group after the 8th treatment week, with ulcer size being reduced by 92% as compared to the control group (Table 2).

5.6. Hypolipidemic Activity

Piyapong and Ampa [159] screened the hypolipidemic effects of 80% EtOH extract of M. pudica whole plant in diabetic male albino Wistar rats using biochemical data, including total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels. In diabetic rats, the levels of TC, TG, and LDL were significantly reduced by plant extract doses and glibenclamide, while plant extract at the dose of 500 mg/kg bw significantly increased HDL. These results indicate that M. pudica possesses a hypolipidemic effect in diabetic rats and may lead to decreased risk of cardiovascular disease and related complications. Purkayastha et al. [58] reported on the hypolipidemic effect of an EtOH extract of M. pudica leaves in Wistar albino rats with hepatic injury induced by CCl4 by measuring biochemical parameters such as triglyceride (TG), total cholesterol (TC), very low density lipoprotein (VLDL), low density lipoprotein (LDL), and high density lipoprotein (HDL) levels. The extract at the dose of 400 mg/kg showed significant decreases in biochemical parameters (TG = 96.8 mg/dL, TC = 98.7 mg/dL, VLDL = 26.9 mg/dL, LDL = 37.4 mg/dL, HDL = 34.3 mg/dL) (Table 2).

5.7. Anti-Inflammatory and Hepatoprotective Activity

Da Silva-Leite et al. [164] determined the healing efficacy of an alcoholic extract prepared from polysaccharides extracted from M. tenuiflora barks (EP-Mt) using MeOH/NaOH and EtOH precipitation. The activity was determined in Wistar rat models of acute inflammation (paw edema and peritonitis). The activity was measured with three different doses (0.01, 0.1, and 1.0 mg kg−1) of plant extract, with the maximum effect with the 1 mg kg−1 concentration as compared to saline. Durgadevi and Karthika [62] reported on the anti-inflammatory activity of an Aq. extract of M. pudica leaves by using bovine serum albumin and egg methods. Extracts at different concentrations (0.2, 0.6, 0.6, 0.8, and 1.0%) showed significant anti-inflammatory activity (serum albumin: 51.5, 59.7, 55.7, 71.5, and 83.7%, respectively; egg: 42.5, 39.6, 48.2, 56.7, 65.3, and 76.7%, respectively) when compared with diclofenac sodium. Onyije et al. [165] measured the anti-inflammatory activity of Aq. extract of M. pudica leaves on adult male Sprague–Dawley rats with cadmium (CdCl2)-induced inflammation of the testes. A sperm analysis was carried out, measuring motility, morphology, and sperm count. Significant activation of sperm motility was observed at different doses of the extract (250 mg/kg = 13.00%; 500 mg/kg = 9.00%) compared with the control group (Aq. = 15.00%). Both doses of the extract showed significant effects on sperm morphology. The sperm counts at different extracts doses (250 mg/kg = 4.18 × 106/cc; 500 mg/kg = 2.54 × 106/cc) were enhanced as compared to control group (12.78 × 106/cc). This study confirmed that M. pudica has ethnomedical uses as a therapeutic intervention for infertility; however, when this plant is used as an aphrodisiac, there is also an added benefit of antioligospermia effects. Kumaresan et al. [57] reported on the hepatoprotective activity of a crude powder of M. pudica whole plant on male albino rats. Injection in parallel with CCl4 and paraffin were given to rats to induce jaundice. Various hepatic parameters such as acid phosphatase (ACP), total bilirubin, gamma glutamyl transferase (γ-GT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), and lipid peroxide (LPO) levels in tissue, serum, aspartate transaminase (AST), and alanine transaminase (ALT) samples were checked. All of these parameters played roles in liver impairment. A dose of 100 mg/kg of extract powder significantly reduced the levels of all parameters and protected the hepatic cells.

Silva et al. [166] reported on the protective action of HyOH extract and EtOAc fraction of M. caesalpiniifolia leaves in adult male Wistar rats suffering from colitis. The HyOH extract (125 and 250 mg/kg) and EtOAc fraction (25 mg/kg) were able to decrease TNF-α immune expression in rats and were found to be effective at lower doses after inducing colitis. The extract showed lower tissue damage at both doses, while the EtOAc fraction was effective at the highest dose (50 mg/kg) only in terms of decreasing COX-2 immune expression. COX-2 and TNF-α played pivotal roles in chronic colitis caused by TNBS. Rakotomalala et al. [155] measured the in vitro anti-inflammatory ability of HyMeOH extract of M. pigra leaves in male Wistar rats to reduce TNFα-induced bound vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1) expression in endothelial cells. The extract at different concentrations (0.01–1 mg/mL) inhibited the induction of VCAM-1 in response to TNFα, with a maximal inhibitory effect of 90% at 1 mg/mL, while the standard drug pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate (200 mM) showed 98% inhibitory effect. In vivo chronic hypoxic PAH cardiac remodeling was also determined in male Wistar rats. Rats were orally treated with extract (400 mg/kg/day) in a hypobaric chamber for 21 days. The extract reduced hypoxic PAH in rats by decreasing pulmonary arterial pressure by 22.3% and pulmonary artery and cardiac remodeling by 20.0% and 23.9%, respectively (Table 2).

5.8. Antinociceptive Activity

Patro et al. [167] determined the antinociceptive effects of M. pudica leaves (EtOAc extract) on adult Wistar albino rats using AA-induced writhing, hot plate, and tail flick models at three concentration (100, 200 and 400 mg/kg). In the hot plate and tail flick tests, after 30 min the extract and the standard diclofenac sodium significantly increased the analgesic activity. The extract doses of 100, 200, and 400 mg/kg decreased the writhing by 20.18, 33.42, and 43.46% respectively, while the standard diclofenac sodium showed 52.01% writhing inhibition against AA. Ahmed et al. [97] determined the antinociceptive activity of the MeOH extract of M. pigra stem in Swiss albino male mice via AA-induced writhing test. Mice orally received various extract doses of 50, 100, 200, and 400 mg/kg/bw, decreasing writhing by 70.01, 74.96, 77.51, and 85.01%, respectively. Aspirin was used as the standard drug.

Rejón-Orantes et al. [106] screened the antinociceptive effects of an Aq. extract of M. albida roots in male ICR mice via AA-induced writhing and hot plate tests. In the AA-induced writhing test, the Aq. plant extract at different concentrations (12.5, 25, and 50 mg/kg) and the reference analgesic drug (dypirone, 100 and 500 mg/kg) were administered 60 min before the AA (0.6%) administration. Counts of the writhing responses (abdominal wall contractions and rotation of pelvis followed by extension of hind limb) were carried out during the test (20 min). M. albida extract (50 mg/kg) and dypirone (500 mg/kg) prevented the abdominal writhing. This study model was also helpful in an investigation of the opioid system involvement in the antinociceptive effects of the M. albida extract. The extract and fentanyl decreased the writhing, although naloxone was only able to antagonize the effects of fentanyl, leaving the antinociceptive potential of the M. albida extract intact. Fentanyl seemed to be more potent than the extract. In the hot plate test, pain reaction (hind paw licking and jumping) was determined as the response latency. Before the test, the response latency was determined, after administration of either M. albida extract, fentanyl (0.1 mg/kg), or the vehicle (NaCl). Fentanyl (30 and 60 min) after treatment and extract (12.5, 25, and 50 mg/kg) at 60 min from its injection produced significant increases in pain latency (Table 2).

5.9. Antiepileptic Activity

Patro et al. [167] measured the antiepileptic effects of EtOAc extract of M. pudica leaves on Swiss albino mice using a maximal electroshock (MES)-induced seizure model, PTZ-induced seizure model, and INH-induced seizure model at different extract doses (100, 200 and 400 mg/kg/day). In the maximum electric shock test, the extract at 100, 200, and 400 mg/kg concentrations and the standard drug diazepam (0.4 mg/kg) caused delayed onset of convulsion by 1.87, 2.69, 3.21, and 3.53 s, respectively; as well as decreased duration of convulsion by 68.09, 53.54, 42.21, and 38.89 s, respectively. In the PTZ-induced convulsion test, the extract at different concentrations of 100, 200, and 400 mg/kg and diazepam (04 mg/kg) caused delayed onset of convulsion (5.38, 6.08, 6.98, and 7.81 min, respectively) and decreased duration of convulsion (14.76, 12.65, 11.13, and 9.39 min, respectively). Regarding the INH-induced convulsions, the extract at different concentrations (100, 200, and 400 mg/kg) showed delayed convulsion latency times of 37.21, 45.49, and 58.62 min, respectively; the results were compared with diazepam (04 mg/kg = 69.14 min delayed convulsion latency). Prathima et al. [35] measured the antiepileptic activity of the EtOH extract of M. pudica roots in adult Swiss albino mice. Maximal electroshock (MES) and pentylenetetrazole (PTZ)-induced seizures were performed. In the maximal electroshock-induced seizures (MES), the durations of tonic hind limb flexion (THLF), tonic hind limb extension (THLE), clonus, and stupor were noted. In the MES tests, the percentages of inhibition of convulsions in mice at different doses (1000 mg/kg = 42.41%; 2000 mg/kg = 52.35%) were noted, while standard valproate showed 73.86% inhibition at 200 mg/kg. In the pentylenetetrazole (PTZ)-induced seizures, the clonic convulsion onset times, durations of clonic convulsions, and postictal depression were observed for a period of 30 min. The extract (1000 and 2000 mg/kg) significantly decreased the number and duration of myoclonic jerks and clonic seizures and the duration of postictal depression (Table 2).

5.10. Neuropharmacological Activities

Arunakumar et al. [163] determined the anti-Alzheimer’s potential of the MeOH extract of M. tenuiflora whole plant by using acetylcholinesterase inhibitory therapy (AChEIs). The results showed that M. tenuiflora is a rich source of compounds with potential anti-Alzheimer’s activity. Ttiyavirah and Pullochal [154] measured the antistress activity of EtOH extract of M. pudica plant in albino Wistar rats by performing swimming endurance, radial arm maze, Morris Aq. maze, and retention phase tests. Adaptogenic activity was assessed by using oral doses of 500 mg/kg of extract and 2 mg/kg diazepam as the standard compound in the swimming endurance test. In the other three tests, the extract was found to effectively reduced stress as compared to standard D-galactose + piracetam. Significant improvements in memory were observed from the test paradigms for the Morris Aq. Maze and radial arm maze tests. The results from the study indicated that the EtOH extract of Mimosa pudica possessed significant antistress activity, along with a potential protective effect against a chronic Alzheimer’s model. Mv et al. [168] measured the neuroprotective effects of M. pudica plant in a Parkinson’s male C57BL/6J model at 100 and 300 mg/kg concentrations of extracts using a vertical grid test, horizontal grid test, and immunohistochemistry measurements. In the vertical grid test, the extract at different concentrations (100 and 300 mg/kg) significantly increased the time taken to climb the grid. In the horizontal grid test, the extract decreased the hang time. The extract at 100 and 300 mg/kg doses decreased SYN- and increased DAT- and TH-positive cells. Patro et al. [167] measured the motor coordination activity of the EtOAc extract of M. pudica leaves in Swiss albino mice by performing locomotor activity, rotarod, and traction tests with three different extract concentrations (100, 200, and 400 mg/kg), while diazepam at 0.4 mg/kg concentration was used as the standard drug. Significant decreases in locomotor activity were observed. In the rotarod test, the fall time was significantly decreased, while in the traction test, the holding time was also significantly decreased. Kishore et al. [169] screened the CNS activities of Aq. extract of M. Pudica leaves in adult albino mice using locomotor activity, elevated plus maze, and rotarod tests at a dose of 200 mg/kg. Percentage changes in locomotor activity were caused by the extract (200 mg/kg = 56.33%) and standard diazepam (0.5 mg/kg = 79.61%). In the elevated plus maze test, the extract (200 kg/mg) and diazepam (0.5 mg/kg) increased the numbers of open arm entries by 67.92% and 78.59% while decreasing the times spent in closed arm positions by 7.32% and 8.64%, respectively. In the rotarod test, the fall times were decreased significantly by the extract (200 kg/mg = 152.1) and diazepam (0.5 mg/kg = 157.6). Mahadevan et al. [170] measured the in vitro neuroprotective effects of the Aq. extract of M. pudica whole plant against Parkinson’s disease in SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cell lines using cell viability assay or MTT assay. The extract significantly upregulated TH and DAT and downregulated α-synuclein expression in intoxicated cell lines. This disease occurs due to decreases in the dopaminergic neurons and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and increases in α-synuclein protein levels.

Rejón-Orantes et al. [106] determined the exploratory and motor coordination activities of the Aq. extract of M. albida roots in male ICR mice. Various concentrations of the extract (50, 100, and 200 mg/kg) and the vehicle NaCl were given to mice before tests. For exploratory activity, an open field test was performed to evaluate the locomotor activity of mice. Locomotory activity (number of lines crossed by the animal) was recorded for 5 min. The extract produced a significant decrease in the number of lines crossed by the animal as compared to the vehicle. For motor coordination activity, the rotarod test was performed. The number of falls from the rolling rod were recorded during the test (3 min). The number of falls from the rotarod were significantly increased after supplementation of Aq. extract from the roots of M. albida (100 and 200 mg/kg) as compared to the vehicle. Rejón-Orantes et al. [106] reported on the anxiolytic activity of Aq. root extract of M. albida in male ICR mice by using elevated plus maze and hole board tests. In the elevated plus maze test, the extract at various concentrations (3.2, 12.5, 25, and 50 mg/kg), dypirone (1 mg/kg), and the vehicle (NaCl) were administrated to mice before testing. In the beginning, the mice were placed on the central plate facing the open arms. Then, the time spent (%) on the open arms was calculated. Significant increases in exploration of open arms in the elevated plus maze test were caused by diazepam. Regarding the hole board apparatus, animals were placed in position and head dippings were counted. Head dippings were significantly enhanced by the diazepam. At all extract doses, M. albida showed no significant effect in either test (Table 2).

5.11. Antiallergic and Antihyperurisemic Activity

Lauriola and Corazza [113] determined the antiallergic activity of the glyceric acid extract of M. tenuiflora bark in a non-atopic 30-year-old woman who had developed acute eczema of the neck in the retroauricular and laterocervical areas. The plant extract was applied on her skin and patch tests were performed. M. tenuiflora potentially soothed the skin with its good antimicrobial properties. Sumiwi et al. [171] measured the antihyperurisemic activity of the EtOH (70%) extract of M. pudica leaves in vitro and ex vivo in Swiss Webster mice (Mus musculus). The IC50 values for the inhibition of uric acid formation with M. pudica tablet, M. pudica extract, and allopurinol were 68.04 ppm, 32.75 ppm, and 18.73 ppm, respectively. The ex vivo results showed that M. pudica tablet at 125 mg/kg of body weight and the extract reduced uric acid levels in hyperurisemic mice by 36% and 43%, respectively. Mimosa pudica tablets at 125 mg/kg of bodyweight inhibited uric acid formation in hyperuricemic mice; therefore, this pharmaceutical dosage form could be proposed as an antihyperurisemic drug (Table 2).

5.12. Larvicidal, Antiparasitic, and Molluscicidal Activity

Oliveira et al. [172] measured the effects of M. tenuiflora leaves and stem on the larval establishment of H. contortus in sheep. The rate of larval establishment was not reduced by the leaves, but stem intake caused a 27.9% reduction; however, no significant reduction was observed. Bautista et al. [173] determined the antiparasitic activity of Hex, MeOH, and ACE extracts of M. tenuiflora leaves against E. histolytica and G. lamblia. The extracts showed significant inhibition (Hex: IC50 = 65.9 and 80.2 μg/mL; ACE: IC50 = 80.7 and 116.8 μg/mL; MeOH: 73.5 and 95.5 μg/mL) against both E. histolytica and G. lamblia, but against G. lamblia. Santos et al. [174] determined the molluscicidal activity of the EtOH extract of M. tenuiflora stems against the snail species Biomphalaria glabrata. The extract showed excellent activity at the 100 µg/mL concentration (LC90 = 62.05 mg/L; LC50= 20.22 mg/L; LC10= 6.59 mg/L). Shamsuddini et al. [175] determined the effects of M. tenuiflora stem extracts against human leishmaniases by using an MTT assay and by counting parasites with various concentrations (10, 100, 500, and 1000 micg/mL) of M. tenuiflora extracts. Different concentrations of M. tenuiflora extract have different effects on the multiplication of Leishmania protozoa in culture medium. The multiplication of promastigotes was found to be suppressed at 1000 and 500 micg/mL concentrations. This finding suggested that M. tenuiflora extract contains both inhibitory and acceleratory effects on Leishmania growth in vitro. Surendra et al. [176] determined the larvicidal action of Aq. extract of M. pudica leaves against Aedes aegypti larvae at different doses (250, 500, 750, 1000, and 2000 μg/m). The potential was determined at 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 12, and 24 h and the percentage mortality rates were calculated. Percentage mortality was approximately zero at all concentrations over 24 h. The Aq. extract was found to possess poor larvicidal actions; thus, it can be concluded that Mimosa pudica was not suitable for larvicidal actions. Brito et al. [177] reported in vivo anthelmintic (AH) activity of M. caesalpiniifolia leaf powder supplementation against nematodes (Haemonchus, Trichostrongylus, and Oesophagostomum) in male goats. Goats were given a M. caesalpiniifolia leaf powder that was rich in condensed tannins (days 1–7 and 14–21). After 28 days, the worm burden was estimated. Post-mortem worm counts indicated a decreased in Haemonchus adult worm burden (57.7%) in goats. For the CT group, no anthelmintic effect against Oesophagostomum was observed; thus, to control gastrointestinal nematode (GIN) infections in goats, feeding with dry M. caesalpiniifolia leaves proved encouraging (Table 2).

5.13. Antispasmolytic, Antivenom, and Antiviral Activity

Lozoya et al. [135] screened the antispasmolytic activity of BuOH, EtOAc, and MeOH extracts of M. Tenuiflora in guinea pig and mouse models. BuOH, EtOAc, and MeOH at 30.0 μg/mL showed significant results by increasing the muscular tonus and frequency of contraction of the uterus. Increases in muscular tonus in the stomach in rats and relaxation of the ileum in guinea pigs were observed. Bitencourt et al. [40] measured the neutralizing capacity of the extract of M. tenuiflora bark on the inflammation induced by Tityus serrulatus scorpion venom in male BALB/c mice. Animals were inoculated intravenously with saline, Aq. extracts (20, 30, or 40 mg/kg) and fractions, DCM, butyl alcohol, and EtOAc (40 mg/kg). The EtOAc fraction showed potent inhibition against inflammatory cells. The EtOAc fraction showed 83, 67, and 86% inhibition at doses of 20, 30, and 40 mg/kg, respectively. The Aq. extract showed 76% cell inhibition at a dose of 30 mg/kg. Jain et al. [60] determined the in vivo antiviral activity of EtOH extract and fractions (Aq., CF, PE, and BZ) of M. hamata whole plant against H. Simplex, poliomyelitis, and V. stomatitis using the plaque inhibition method. The EtOH extract was found to be active against all three viruses. CF and PE were found to be active against V. stomatitis. None of the fractions were active against poliomyelitis (Table 2).

6. Toxicological Studies of the Genus Mimosa Concerning Hemolysis, Antimutagenic, Genotoxic, and Teratogenic Effects

Magalhães et al. [149] determined the toxicity of the EtOH extract and fractions (Hex, DCM, EtOAc, and HyOH) of M. tenuiflora leaves, roots, twigs, and barks using non-specific toxicity to A. salina L. and cytotoxicity to African green monkey kidney (Vero) cells via MTT assay. Only the HyOH fraction killed 50% of the nauplii (LC50 = 793.70 μg/mL). The fraction of M. tenuiflora with the highest antioxidant potential (FATEM) was not toxic to A. salina L. (LC50 ˃ 1000.00 μg/mL) or Vero cells (CC50 = 512.6 μg/mL). Meckes-Lozoya et al. [135] investigated the hemolytic effects of BuOH, EtOAc, and MeOH extracts of M. tenuiflora stem bark against enterocytes. BuOH and EtOAc extracts at 250.0 g/mL and MeOH at 500.0 μg/mL increased hemolysis by 74%, 48%, and 68%, respectively. Furthermore, de Morais-Leite et al. [136] measured the hemolytic effects of EtOH extract of M. tenuiflora bark on human erythrocytes (types A, B, and O). At the concentration of 1000 μg only, hemolysis was observed in erythrocytes type A at 3.0%, but at the concentration of 2000 μg all three human erythrocytes (A, B, and O) presented hemolysis (23.1, 5.17, and 1.08% respectively). Overall, the extract showed low toxicity for the human erythrocyte cells. Silva and colleagues reported the hemolytic potential of EtOH bark extract of M. tenuiflora against human RBCs at various concentrations (250, 500, and 1000 μg/mL). At the 1000 μg/mL concentration, highest hemolysis was observed (90%). While at low concentrations (125, 62.5, 31.25, 15.8 μg/mL), no activity was observed [137] (Table 3).

Prathima et al. [35] measured the acute toxicity of the EtOH extract of M. pudica roots in adult Swiss albino mice at different doses (0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 5 g/kg p.o.). There was no mortality amongst the mice treated with the graded dose of extract up to a dose of 5000 mg/kg at a duration of 72 h. Cadmium (Cd) is a well-recognized pollutant with great neuroendocrine-disrupting efficacy. It damages the hypothalamic–pituitary–testicular axis in mature male Wistar rats. The aqueous (Aq.) extract of M. pudica leaves was administered orally to rats at a dose of 200 mg/kg for 40 consecutive days. At the end of the analysis period, the extract was used as a therapeutic intervention for infertility [178]. The acute toxicity of EtOAc [167] and EtOH [58] extracts of M. pudica leaves on adult Wistar albino rats was determined. No mortality or signs of toxicity were observed at the dose of 2000 mg/kg. Nghonjuyi et al. [22] measured the in vivo toxicity of HyOH extracts of M. pudica leaves in Kabir chicks. Single doses of HyOH extracts were administered orally at doses ranging from 40 to 5120 mg/kg for the acute toxicity test. No death was recorded at doses lower than 2560 mg/kg. Very low hypoactivity was observed at the extract dose of 5120 mg/kg. In the sub-chronic study, these extracts were given orally as a single administration to chicks at doses of 80, 160, 320, and 640 mg/kg/day for 42 days. No toxicity was observed with oral sub-chronic low dose administration. Das et al. [151] measured the cytotoxicity of the MeOH extract of M. pudica leaves using a brine shrimp lethality bioassay. The LC50 of the extract was found to be 282.4 μg/mL, whereas the reference standard vincristine sulphate exhibited an LC50 of 0.45 μg/mL. The results of the above findings clearly demonstrated that the leaves of M. pudica showed mild cytotoxic properties. Olusayo et al. [179] screened the acute toxicity of the EtOH extract of M. pigra roots in adult Wistar rats. No mortality was observed at 5000 mg/kg, which showed that the plant is relatively safe. In sub-acute toxicity tests, three groups of adult Wistar rats were given different concentration of the extract of 250, 500, and 1000 mg/kg/bw, which corresponded to 1/20th, 1/10th, and 1/5th of the 5000 mg/kg dose, respectively. To determine the biochemical (ast, alt, alp, total protein, cholesterol, urea, creatinine, and total bilirubin) and hematological (pcv, rbc, and hb) parameters, rat blood samples were collected on the 29th day. The results of the study showed that there were significant increases in packed hemoglobin, cell volume, and red blood cell count at different extract doses (500 and 1000 mg/kg). The extract produced no significant changes in the levels of total bilirubin, total cholesterol, total protein, aspartate aminotransferase, or alkaline phosphatase in any of the groups that were treated, although a significant increase in the level of alanine transaminase was observed. Serum levels of urea and creatinine were not affected. The findings of this study showed that the roots of M. pigra may be safe at doses below 500 mg/kg but may pose toxicological risks at doses greater than 500 mg/kg, with the liver being most affected with prolonged usage. Monção et al. [180] reported on an in vivo toxicological and androgenic evaluation of the EtOH extract of M. caesalpiniifolia leaves in adult male Wistar rats using body weight loss and serum biochemical parameters (ALP, AST, urea, and creatinine). In the toxicological evaluation, the extract induced a body weight loss at the highest tested dose (750 mg/kg). No androgenic activity was observed at any dose level (250, 500, or 750 mg/kg). Monção et al. [180] reported on the in vitro cytotoxicity of the EtOH extract of M. caesalpiniifolia leaves using an MTT assay in murine macrophages and a brine shrimp lethality assay in Artemia salina. The extract showed LC50 values of 1765 µg/mL against Artemia salina and 706.5 µg/mL against murine macrophages. Rejón-Orantes et al. [106] reported acute toxicity of Aq. extract of M. albida roots in male ICR mice. Different doses (3.2, 12.5, 25.50, 100, 200, 300, and 400 mg/kg) of M. albida extract were given to various mice groups and their mortality rates were recorded until 48 h; no mortality was observed. Nandipati et al. [122] reported acute toxicity of MeOH extract (500–4000 mg/kg) of M. rubicaulis stem against Swiss albino mice, administered by oral gavage. No mortality was witnessed at the dose of 4000 mg/kg. Silva and colleagues reported the hemolytic potential of the EtOH bark extracts of M. verrucosa and M. pteridifolia against human RBCs at various concentrations (250, 500, and 1000 μg/mL). For the M. verrucosa extract at the 1000 μg/mL concentration, the highest hemolysis rate was observed (100%). At low concentrations (125, 62.5, 31.25, and 15.8 μg/mL), no activity was observed [138], while M. pteridifolia showed no hemolysis with any tested concentrations (Table 3).

Silva et al. [181] measured the mutagenic and antimutagenic effects of crude EtOH extract of M. tenuiflora stem bark against S. typhimurium strains (TA97, TA98, TA100, TA102) using the Ames test. No mutation was induced in any of the strains at concentrations of 50 and 100 μg/mL of extract. The extract showed antimutagenic effects in all strains, although no antimutagenic effect was observed in TA98. The genotoxicity of crude EtOH extract of M. tenuiflora stem bark using a micronucleus test in the peripheral blood of albino Swiss mice has been reported [181]. The extract (100 to 200 mg/kg) and cyclophosphamide (reference drug, 50 mg/kg) were given to mice, whereby the extract at 100 and 200 mg/kg increased the numbers of micronucleus by 8.75 and 9.91, respectively, as compared to cyclophosphamide (50 mg/kg = 43.5). Medeiros et al. [182] determined the teratogenic effects of M. tenuiflora seeds in pregnant Wistar rats, whereby a 10% dose of M. tenuiflora seeds was given to rats in a Brazilian semiarid climate. The extract was given from the 6th to the 21st day of pregnancy. No differences were observed in weight gain in the lungs, heart, liver, or kidneys of rats or in food or Aq. consumption between treated and controlled rats. Ninety bone malformations were observed in 40 of the 101 fetuses, including skeletal malformations such as scoliosis, bifid sternum, cleft palate, and hypoplasia of the nasal bone. Scientists measured [183,184] the teratogenic effects of M. tenuiflora in pregnant goats and lambs in the semiarid rangelands of Northeastern Brazil. The four goats fed on fresh green M. tenuiflora during pregnancy delivered 4 kids, 3 of which had abnormalities, including cleft lip, ocular bilateral dermoids, unilateral corneal opacity, buphthalmos (with a cloudy brownish appearance of the anterior chamber due to an iridal cyst), and segmental stenosis of the colon. Dantas et al. [185] measured the teratogenic effects of green fresh M. tenuiflora in pregnant goats in the semiarid rangelands of Northeastern Brazil. A high frequency of embryonic deaths was observed in pregnant goats if M. tenuiflora was ingested in the first 60 days of gestation. Gardner et al. [186] determined the teratogenicity of M. tenuiflora leaves and seeds on pregnant rats in Northeastern Brazil. Compounds extracted from M. tenuiflora showed higher incidence rates of soft tissue cleft palate and skeletal malformations. Silva et al. [32] measured the antigenotoxic activities of the EtOH extract and EtOAc fraction of M. caesalpiniifolia leaves using a comet challenge assay and micronucleus test. The extract at a concentration of 125 mg/ kg bw inhibited oxidative DNA damage in liver cells, which was induced by hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in animals intoxicated with cadmium (Cd). Furthermore, the EtOAc fraction decreased the genomic damage and mutagenesis induced by cadmium exposure. The genus Mimosa is able to modulate the toxic effects caused by cadmium exposure as a result of antigenotoxic and antioxidant activities in blood and liver cells of rats (Table 3).

Table 3.

Toxicological studies of the genus Mimosa regarding hemolysis, antimutagenic, genotoxic, and teratogenic effects.

Table 3.

Toxicological studies of the genus Mimosa regarding hemolysis, antimutagenic, genotoxic, and teratogenic effects.

| Activities | Plant | Plant Part | Extract/Fraction | Assay | Model | Results/Outcome/Response | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toxicological studies | M. tenuiflora | Leaves, twigs, barks, roots | EtOH extract and fractions (Hex, DCM, EtOAc and HyOH | (1) Non-specific toxicity (2) Cytotoxicity to Vero cells by MTT assay | (1) Artemia salina L. (2) Vero cells of African green monkey kidney | Only the HyOH fraction killed 50% of the nauplii (LC50 = 793.70 μg/mL). Fractions of EtOH extract were not toxic to A. salina L. (LC50 ˃ 1000.00 μg/mL). Fractions of EtOH extract were not toxic to Vero cells (CC50 = 512.6 μg/mL) | [149] |

| Stem bark | BuOH, EtOAc MeOH | In vitro | Erythrocytes | Buthanol 250 μg/mL = 74%; EtOAc 250 g/mL = 48%; MeOH 500 μg/mL = 68% | [135] | ||

| EtOH | Hemolytic assay | Human erythrocytes type A, B, and O | At 1000 μg concentration, only hemolysis of erythrocyte A (3%) was observed, while at 2000 μg concentration, extract showed hemolysis on type A = 23.1%; type B = 5.17%; type O = 1.08% | [136] | |||

| Bark | EtOH | Hemolytic assay | Human RBCs | % hemolysis at 1000 μg/mL = 90%, 500 μg/mL = 35%, 250 μg/mL = 17% | [137] | ||

| M. pudica | Roots | EtOH | Acute toxicity | Swiss albino mice | No mortality was observed at extract dose up to 5000 mg/kg | [35] | |

| Leaves | Aq. | Histoarchitecture parameters | Mature male Wistar rats/cadmium-induced toxicity | Extract doses of 200 mg/kg were found effective | [178] | ||

| EtOAc | Acute toxicity | Adult Wistar rats | No mortality or signs of toxicity were observed at the dose of 2000 mg/kg | [167] | |||

| EtOH | Acute toxicity | Wistar albino rats | No mortality as observed up to the dose level of 2000 mg/kg bw | [58] | |||

| HyOH | In vivo toxicity/Kabir chicks | Very low toxicity observed at high dose of 5120 mg/kg | [22] | ||||

| Sub-chronic toxicity observed at doses of 80, 160, 320, and 640 mg/kg | |||||||

| MeOH | Brine shrimp lethality bioassay | Extract 1–500 μg/mL; LC50 = 282.3495 μg/mL), standard vincristine sulphate; LC50 = 0.45 μg/mL | [151] | ||||

| M. pigra | Roots | EtOH | Acute toxicity | Adult Wistar rats | No mortality observed | [179] | |

| Hematological and biochemical parameters | Adult Wistar rats | Doses greater than 500 mg/kg posed toxicological risks | |||||