Abstract

Panax ginseng is a valuable traditional Chinese medicine in Northeast China. Ginsenoside, the active component of ginseng, has not been investigated much for its effects on aging and its underlying mechanism(s) of action. Here, we investigated the effects of total ginsenoside (TG), a mixture of the primary active ginsenosides from Panax ginseng, on the lifespan of Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans). We found that TG extended the lifespan of C. elegans and reduced lipofuscin accumulation. Moreover, TG increased the survival of C. elegans in response to heat and oxidative stress via the reduction of ROS. Next, we used RNA-seq to fully define the antiaging mechanism(s) of TG. The KEGG pathway analysis showed that TG can prolong the lifespan and is involved in the longevity regulating pathway. qPCR showed that TG upregulated the expression of nrh-80, daf-12, daf-16, hsf-1 and their downstream genes. TG also reduced the fat accumulation and promoted lipid metabolism. Moreover, TG failed to extend the lifespan of daf-16 and hsf-1 mutants, highlighting their role in the antiaging effects of TG in C. elegans. The four main constitution of TG were then confirmed by HPLC and included ginsenoside Re, Rg1, Rg2 and Rd. Of the ginsenosides, only ginsenoside Rd prolonged the lifespan of C. elegans to levels comparable to TG. These findings provided mechanistic insight into the antiaging effects of ginsenoside in C. elegans.

1. Introduction

Aging is defined as a progressive decline in tissue, organ and neuronal function [1]. With the elucidation of the signaling pathways that influence aging, strategies to prolong the lifespan and improve human health have been explored. Antioxidants are one such example, which delay aging and promote health [2,3]. Antioxidants are commonly associated with stress responses and can reduce reactive oxygen species levels in vivo. In addition, recent figures have suggested that lipid metabolism plays a key role in aging, and specific lipids and lipid-related molecules can regulate the lifespans of a variety of model organisms (e.g., C. elegans, Drosophila melanogaster, mosquitoes and rodents) [1,4].

Panax ginseng is an important traditional Chinese medicine in Northeast China that has gained popularity. Ginseng root has been widely used for centuries in Chinese medicine as a panacea that prolongs the lifespan [5]. White and red ginseng are obtained through the processing of fresh ginseng root but have differential functions. Ginseng has been extensively studied and is used in clinics for a range of disease states. Ginseng contains ginsenosides, polysaccharides, peptides and fatty acids [6,7]. The majority of the pharmacological effects of ginseng root can be attributed to ginsenosides, a diverse group of steroidal saponins [7]. The positive effects of ginsenosides have been shown in the CNS and in the cardiovascular, endocrine and immune systems [8,9,10]. Ginsenosides have been ascribed antineoplastic [11], anti-inflammatory [12] and antioxidant activity [13], which have good medicinal and commercial prospects. Ginsenosides can be utilized by C. elegans as a sterol substitute and play an important role in the growth and recovery of nematodes in a cholesterol-deprived medium [14,15]. Ginseng extract can resist the negative effects of heat stress [16]. Studies on C. elegans have shown the promising efficacy of certain saponins in reversing age-related declines via antioxidant regulation and longevity signaling pathways [17]. Sun Ginseng can effectively inhibit the proliferation and differentiation of adipocytes and can reduce the fat accumulation in C. elegans, which also suggests that the active substance in ginseng that plays the function of reducing the fat accumulation may be ginsenosides [18]. Ginseng extract consists of a mixture of the primary active ginsenosides. Although ginseng possesses antiaging effects, the molecular mechanism(s) of how total ginsenoside (TG) delays aging through the lipid metabolism pathway remain undefined.

In this study, we used a Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans) model to evaluate the antiaging effects of TG and its underlying mechanism(s) of action. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was also performed to identify the active constituents of TG. We found that TG and ginsenoside Rd treatment significantly extend the lifespan of C. elegans through a shared mechanism. A subsequent genetic analysis revealed that TG and ginsenoside Rd extend the lifespan of C. elegans through a shared mechanism involving nhr-80, daf-12, daf-16 and hsf-1.

2. Results

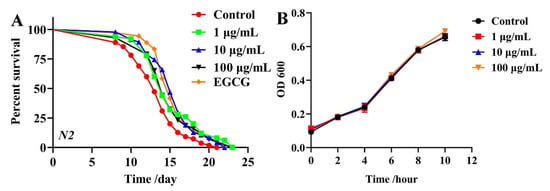

2.1. Effects of TG on the Lifespan of C. elegans

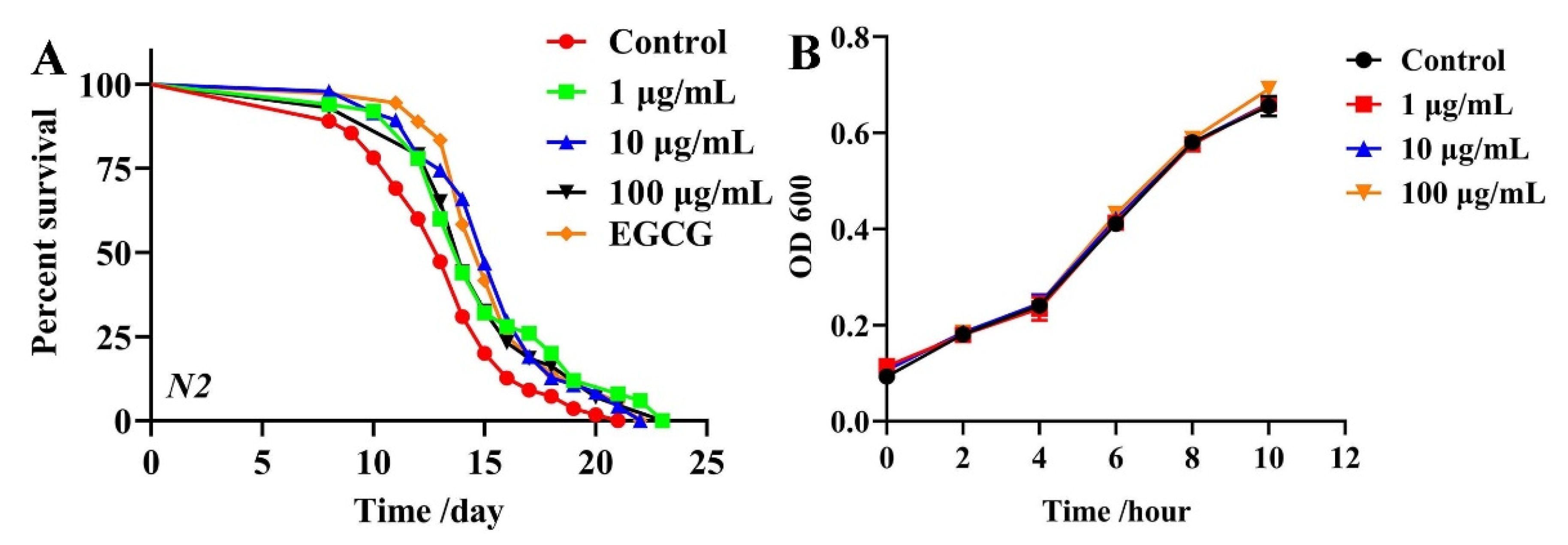

To investigate the effects of TG on the lifespan of C. elegans, we compared to the control group the lifespan curves of the three test concentrations (1 μg/mL, 10 μg/mL and 100 μg/mL and 500 μM EGCG as a positive control), which showed a significant rightward shift (Figure 1A and Table S3), suggesting that TG treatment extended the lifespan of C. elegans. Moreover, the most significant effect occurred at 10 μg/mL, which increased the mean lifespan by 9.11 ± 2.04% (Table S3). These data confirmed the ability of TG to prolong the lifespan of C. elegans.

Figure 1.

Effects of TG on the lifespan of C. elegans and E coil. OP50. (A) Survival of C. elegans treated with 0.1% DMSO (control); 500 μM EGCG (positive control) and 1, 10 and 100 μg/mL TG. TG produced its optimal effects at 10 μg/mL, extending the lifespan of C. elegans by up to 9.11 ± 2.04%, n = 3 (~80 individuals per group), Kaplan–Meier survival analysis with the log-rank test. (B) OP50 in LB medium containing 1, 10 and 100 μg/mL TG. TG did not inhibit the growth of OP50 during any bacterial growth phase. Data were analyzed by a Student’s t-test using GraphPad 8. Values are presented as the mean ± SEM.

Previous studies showed that the metabolism of OP50 influences the lifespan of C. elegans and that ginsenosides possess antibacterial effects [19,20,21]. Live OP50 was used in all the experiments. To eliminate the influence of bacterial growth and metabolism on the lifespan of C. elegans, we explored whether TG influences the growth and metabolism of OP50. Growth curves of OP50 in LB liquid media containing 1, 10 and 100 μg/mL TG were determined. TG had no significant effects on the proliferation of OP50 (Figure 1B). These results suggested that the TG treatment effectively extended the lifespan of C. elegans at 10 μg/mL. This concentration was selected for subsequent experiments.

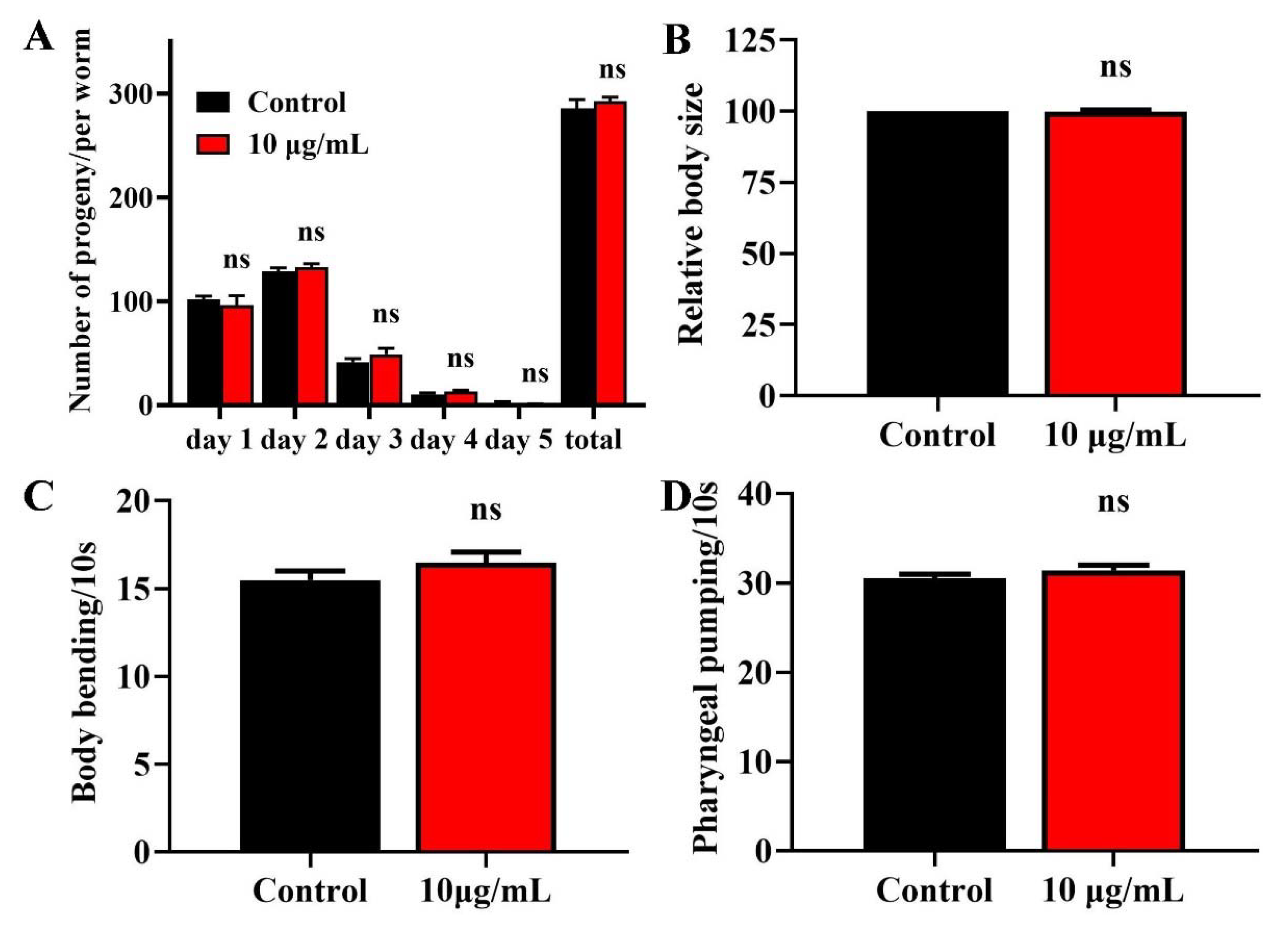

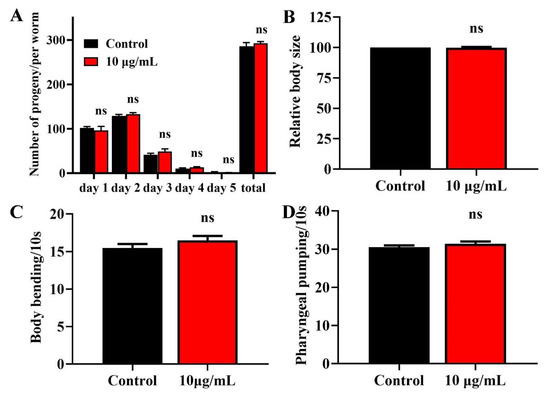

2.2. TG Has No Effects on the Fecundity and Body Size of C. elegans

Lifespan extension is related to a loss of fecundity [22]. We therefore investigated the effects of TG treatment on the reproduction of C. elegans. We observed no significant difference in daily egg production and total progeny production following TG treatment (Figure 2A), suggesting that the TG-mediated lifespan extension of C. elegans was not dependent on sacrificial reproduction. The pretreatment with TG also caused no changes in the body length (Figure 2B). All of these suggested that TG had no effects on the normal growth and development.

Figure 2.

Effects of TG on the breeding population, body size, body bending and pharyngeal pumping in C. elegans. (A) Breeding of C. elegans treated with or without TG. The number of eggs were monitored on day 1 of adulthood until day 5. (B) Worms treated with TG showed no significant changes in body size. (C) Worms treated with TG showed no significant changes in body bending. (D) Worms treated with TG showed no significant changes in pharyngeal pumping.

2.3. TG Has No Effect on the Body Bending and Food Intake of C. elegans

Muscle cells gradually lose vitality during aging, leading to the loss of locomotion and pharyngeal pumping [23,24]. We measured the body bending rates and pharyngeal pumping of TG treatment as an indicator of muscle change. TG treatment had no effect on body bending or the pharyngeal muscle contractility of C. elegans (Figure 2C,D). Pharyngeal pumping also reflects the food intake, which indicated that TG had no effect on the food intake of C. elegans. The pretreatment with TG can effectively delay the degradation of muscle performance.

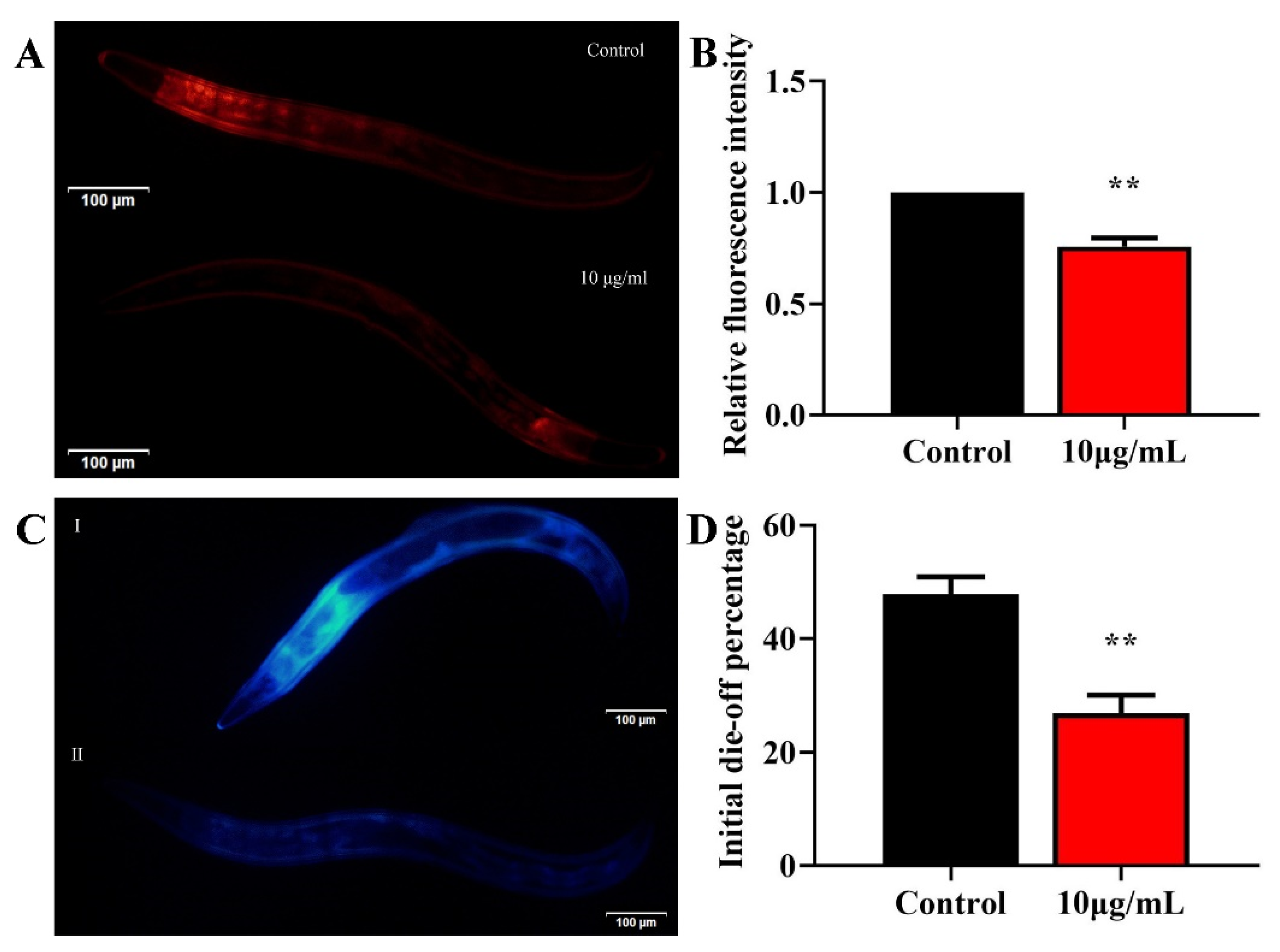

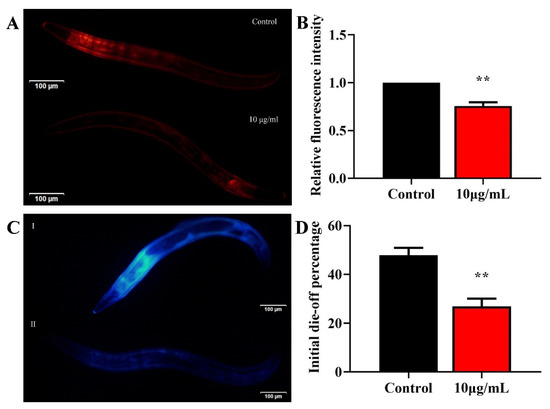

2.4. TG Reduces Lipofuscin Accumulation

To understand whether TG treatment increases the health span, we evaluated the effects of 10 μg/mL TG on age-associated lipofuscin changes. Lipofuscin is often used as a marker of aging [24,25]. The accumulation of lipofuscin may diminish the autophagocytotic capacity and interfere with the recycling of cellular components [26]. Standardization regarding the excitation/emission wavelengths for the detection of lipofuscin are lacking [25]. It has been reported that blue autofluorescence (excitation/emission centered on 340/430 nm) increases by only low levels before and after death, which may reflect the fraction of dead or almost-dead individuals in the sample. In contrast, red autofluorescence (excitation/emission centered on 546/600 nm) increases linearly over time and correlates with the future lifespan of each individual [25]. We therefore used two excitation wavelengths to detect lipofuscin. TG treatment significantly reduced the lipofuscin deposition compared to the control group (Figure 3A–D). Altogether, TG treatment significantly reduced age-associated lipofuscin accumulation, which can be considered an improvement in the health span of C. elegans.

Figure 3.

Effects of TG on the lipofuscin accumulation in C. elegans. (A–D) Worms were treated with TG for 8 days at 20 °C. Lipofuscin accumulation was measured using blue (Ex/Em 340/430 nm) and red autofluorescence (Ex/Em 546/600 nm). TG significantly reduced the lipofuscin accumulation in C. elegans. The data were analyzed using a Student’s t-test. The values were shown as the mean ± SEM, ** p < 0.01.

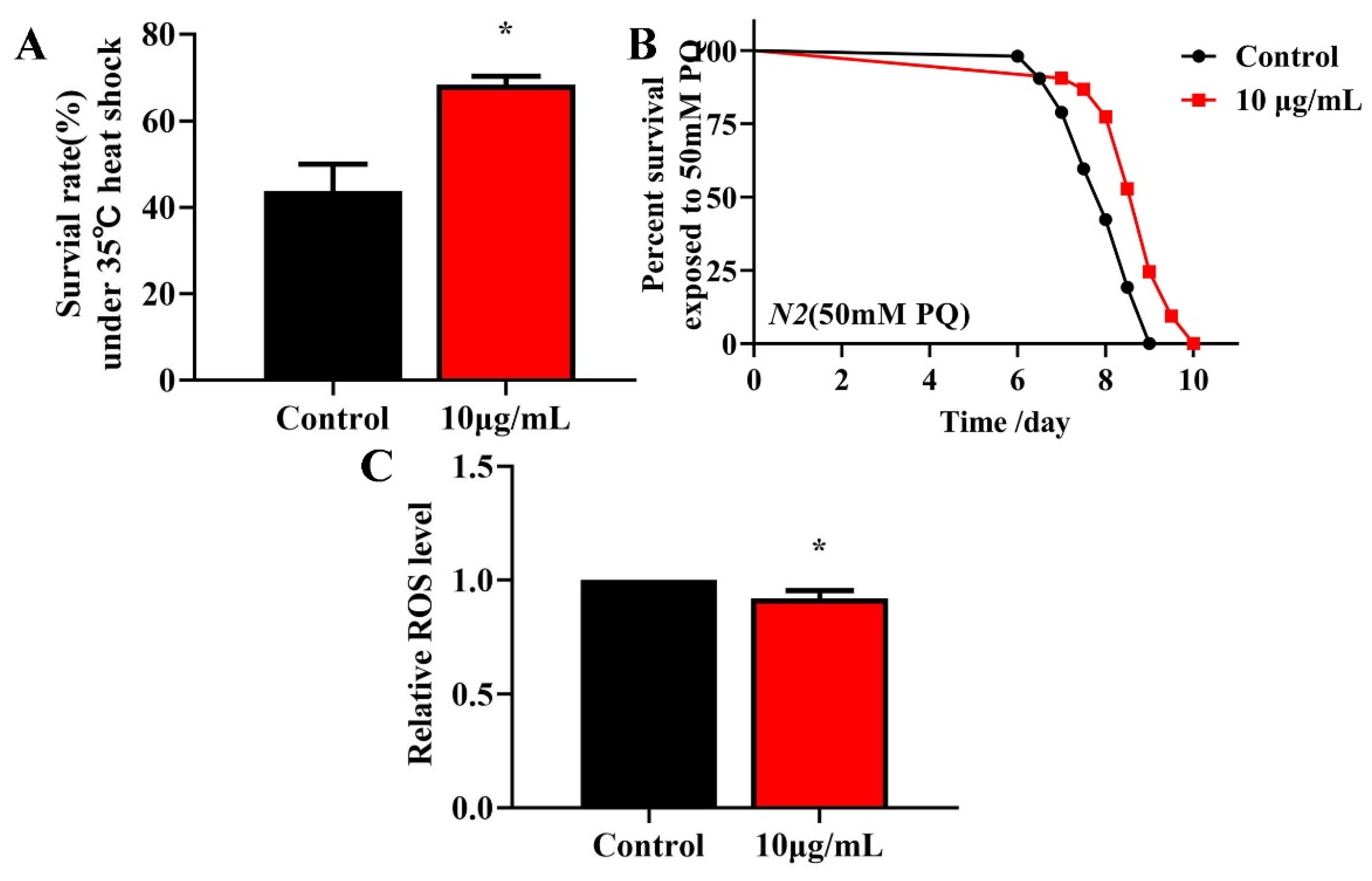

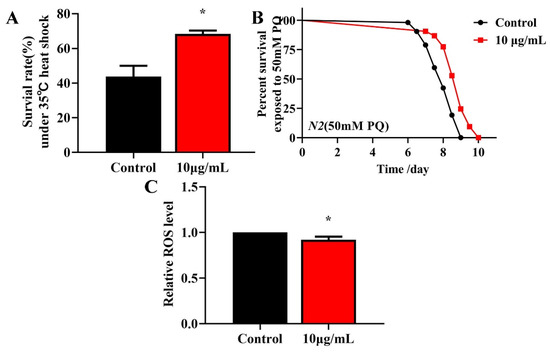

2.5. TG Increases Survival and Reduces ROS Levels in Stress-Induced C. elegans

Longevity is associated with survival under conditions of oxidative or heat stress [27,28]. To investigate whether TG treatment enhances the stress resistance, L4 worms were pretreated with 10 μg/mL TG for 3 days at 20 °C and exposed to 50 mM paraquat (an intracellular ROS generator) or heat stress (35 °C). The pretreatment with TG significantly increased the survival of worms under stress conditions (Figure 4A,B), indicating that TG increases the resistance of C. elegans to oxidative and heat stress. According to the Free Radical Theory of Aging, excessive ROS levels are responsible for the process of aging [29]. Moreover, heat stress leads to ROS accumulation [30,31]. The fluorescent probe H2DCFDA can be used to determine the ROS levels in C. elegans. The results showed that the TG treatment reduced the intracellular ROS levels under heat stress (Figure 4C). Collectively, the pretreatment with TG not only prolonged the lifespan of worms but also improved their ability to resist stress. Part of the reason for that may be that TG reduced the ROS levels in C. elegans.

Figure 4.

Effects of TG pretreatment on the stress resistance and ROS accumulation in C. elegans. (A) TG significantly increased the survival of worms under heat stress. (B) The worms were treated with or without TG and exposed to 50 mM paraquat. (C) Relative levels of ROS in C. elegans following the treatment with TG. TG decreased the ROS levels in the worms, evidenced by the quantification of the fluorescence intensity. The data were analyzed using a Student’s t-test. The values were shown as the mean ± SEM, * p < 0.05.

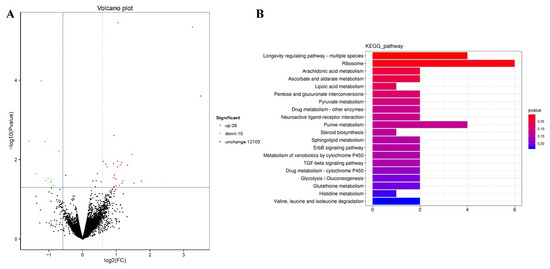

2.6. Genome-Wide Transcriptional Profiling of C. elegans

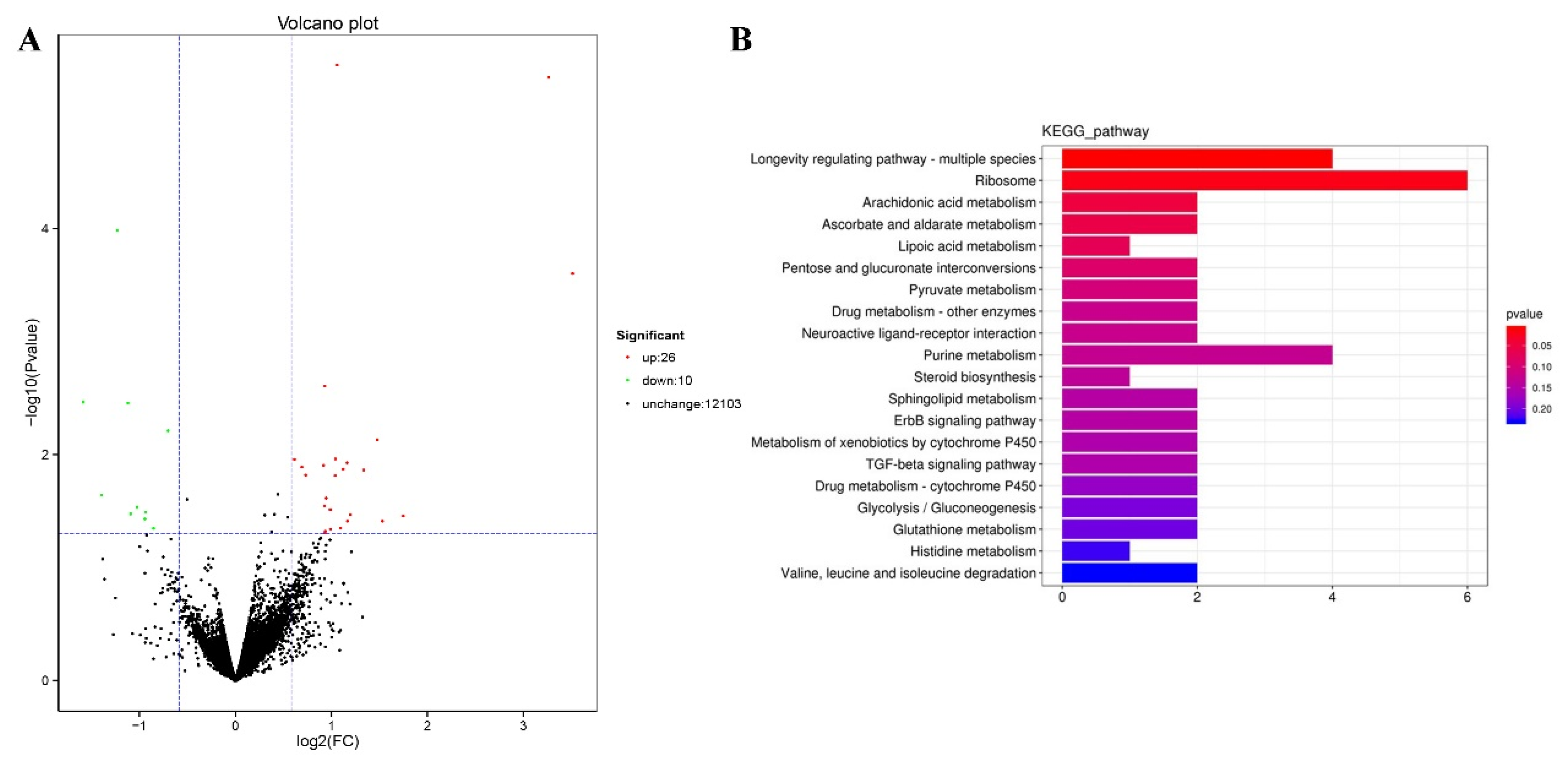

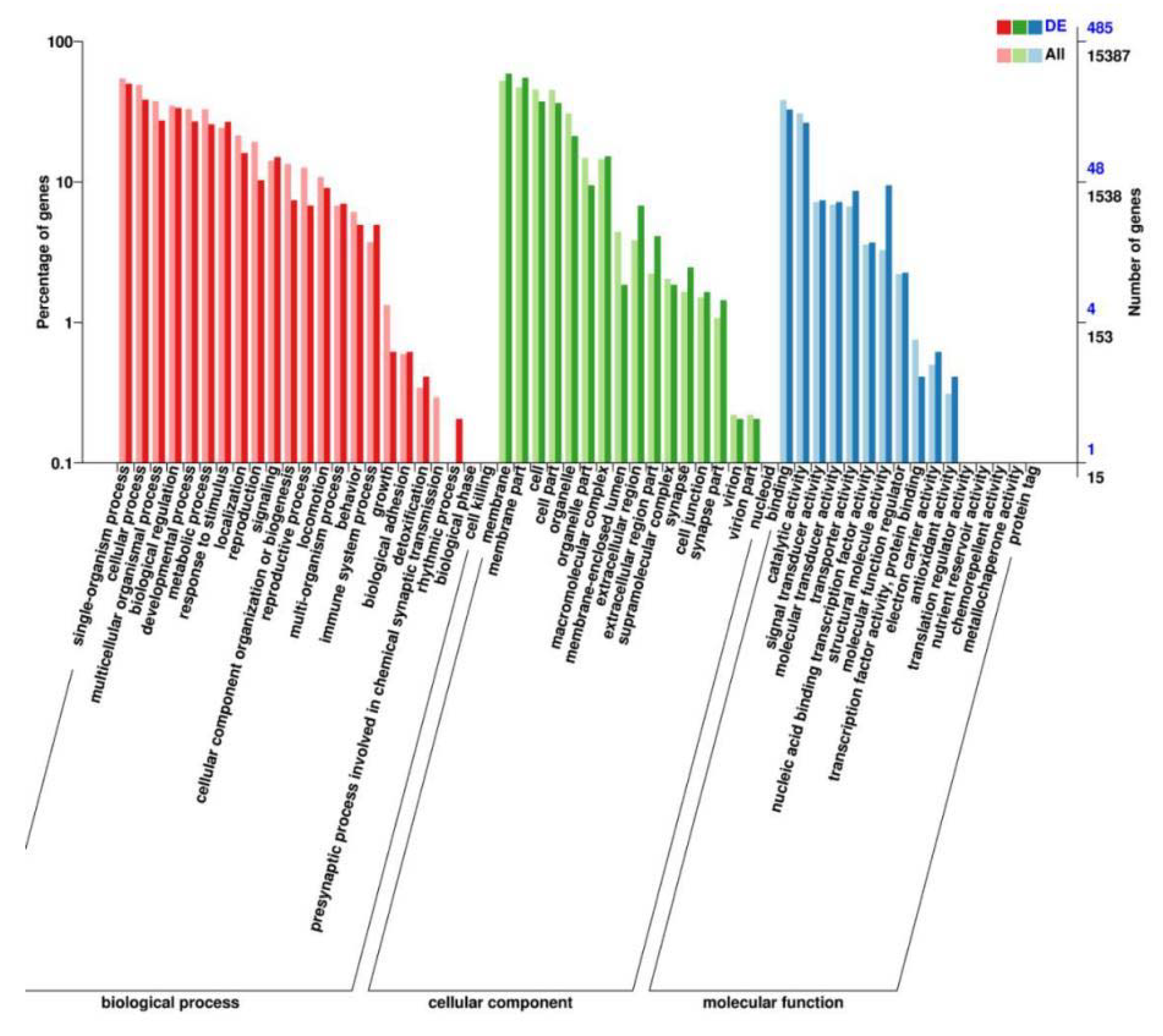

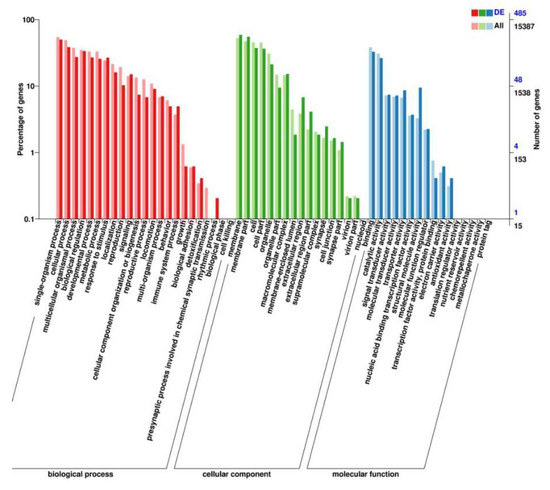

We performed RNA-seq to identify the genes mediating the effects of TG on lifespan extension on a more global scale. Following 3 days of TG treatment, 26 genes were upregulated and 10 were downregulated (fold change > 1.5, p < 0.05; Figure 5A). A larger number of GO terms were enriched in upregulated genes, namely single-organism processes, cellular processes, membranes, membrane part binding and catalytic activity (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Modulated pathways in TG treated in C. elegans. (A) A total of 26 genes were upregulated and 10 genes were downregulated following the TG treatment (FDR < 0.05 and fold change > 1.5). (B) The KEGG analysis of differentially expressed genes in TG-treated C. elegans.

Figure 6.

GO analysis of the genes significantly regulated in TG-treated C. elegans.

The functional description of differential genes in the WormBase database revealed that the top five most significantly up and downregulated genes were influenced by the nuclear receptor daf-12 and downstream of the insulin/IGF-1 signaling pathways (daf-2), including daf-16 and hsf-1 (Table 1 and Table 2). Differentially expressed genes were concentrated in the germ cells, intestinal cells and neurons, indicating that the effects of TG on C. elegans were tissue-specific.

Table 1.

Top 5 upregulated genes in response to TG.

Table 2.

Top 5 genes downregulated in response to TG.

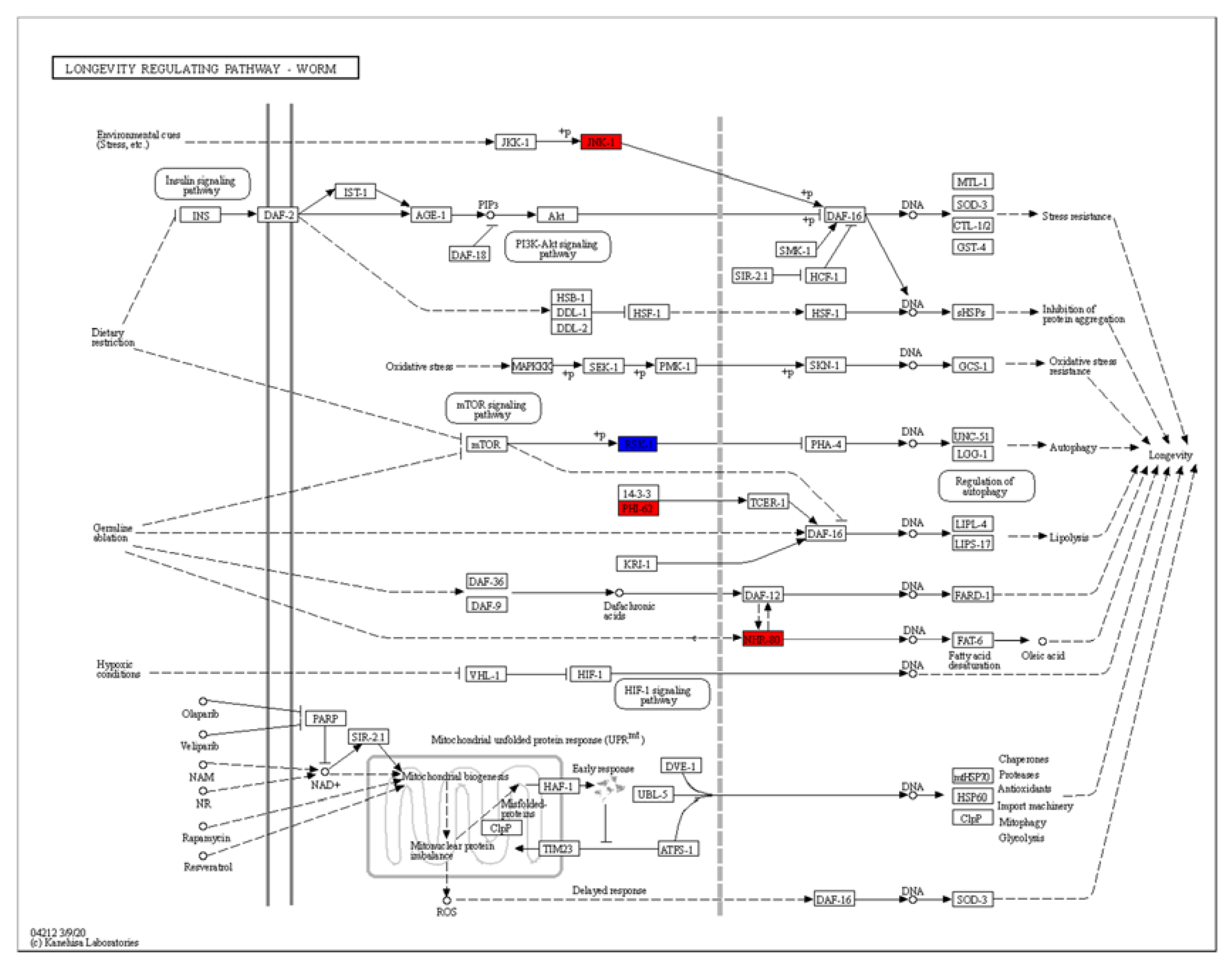

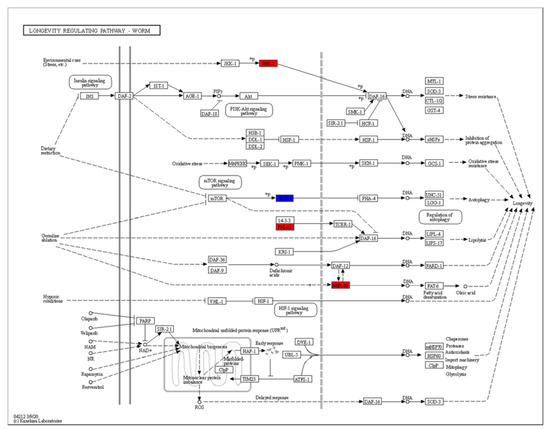

The KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) analysis revealed dramatic changes in the ribosomes and the metabolism of arachidonic acid, ascorbate, aldarate, lipoic acid and purine (Figure 5B). Differentially expressed genes enriched in the lifespan regulatory pathways showed that jnk-1, phi-62 and nhr-80 were significantly upregulated (Figure 7). Jnk-1 and phi-62 were upstream of the transcription factor DAF-16, which activates DAF-16 and promotes the lifespan of C. elegans. As a known activator of DAF-16, JNK-1 is activated in response to cellular stress [32,33]. PHI-62 influences DAF-16-dependent transcription through its interaction with TCER-1 [34]. Moreover, germline ablation and dietary restrictions regulate the stress resistance, lipid metabolism and protein aggregation through DAF-16 and NHR-80 (Figure 7). The nuclear hormone receptor NHR-80 interacts with DAF-12 (Figure 7). According to Table 1 and Table 2, we speculate that TG mediates the longevity of C. elegans by influencing the downstream transcription factors of insulin/IGF-1 signaling, DAF-12 and NHR-80. These genes were explored in subsequent experiments.

Figure 7.

The KEGG analysis of differentially regulated genes.

2.7. TG Extends the Lifespan of C. elegans through Lipid Metabolism Signaling Pathway

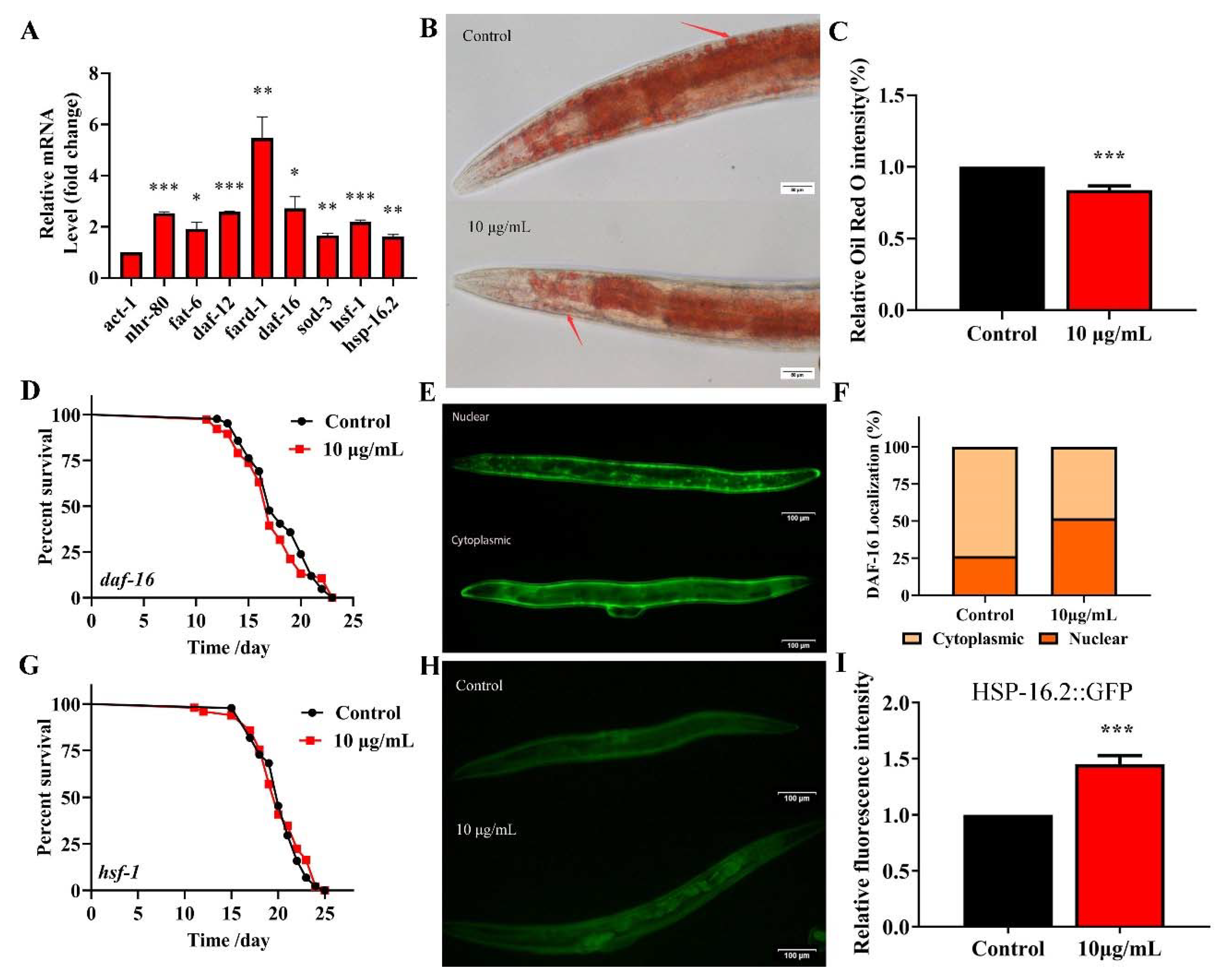

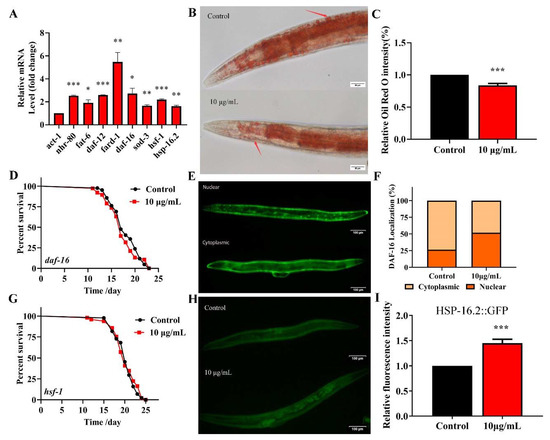

Fatty acid desaturase FAT-6 is a key target of NHR-80 and regulates the lipid metabolism in C. elegans [35]. The fard-1 gene of C. elegans is predicted to encode a lipid acyl-CoA reductase, regulated by the nuclear receptor DAF-12. These four genes regulate the lipid-metabolism and longevity [36]. TG significantly upregulates the expression of NRH-80 (Figure 7). We used qPCR to analyze the effects of TG on daf-12 and nhr-80 and their downstream genes fard-1 and fat-6 (Figure 8A). As predicted, TG significantly increased the expression of all genes; amongst which, fard-1 mRNA increased by more than five-fold. These data confirmed that the regulatory effects of TG on the lipid metabolism are associated with the increased expression of daf-12, nhr-80 and their downstream genes fard-1 and fat-6. We used Oil red staining to observe the lipid accumulation, and the results showed that 10 μg/mL TG significantly reduced the fat accumulation at day 3 (Figure 8B,C). During the aging process, fat gradually accumulates, even leading to obesity-related diseases [37]. This data suggested that TG activated the lipid metabolism signaling pathway and also improved the health span in C. elegans through the lipid metabolism signaling pathway.

Figure 8.

TG reduces the fat accumulation and increases the expression of nhr-80, daf-12, daf-16 and hsf-1 in C. elegans. (A) TG enhances the expression of nhr-80, fat-6, daf-12, fard-1, daf-16, sod-3, hsf-1 and hsp-16.2. (B,C) The fat content in C. elegans treated with or without TG. The worms were stained with oil red O. TG significantly reduced the fat content in C. elegans. (D) The mean lifespan of daf-16 (mgDf50) treated with or without TG. TG could not extend the lifespan of daf-16 (mgDf50). (E,F) DAF-16::GFP expression in TG-treated worms. (G) The mean lifespan of hsf-1 (sy441) with or without TG. TG failed to extend the lifespan of hsf-1 (sy441). (H,I). The quantification of HSP-16.2::GFP fluorescence in the presence or absence of TG. TG significantly increases the expression of HSP-16.2 in C. elegans. The data were analyzed using a Student’s t-test. The values were shown as the mean ± SEM, *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05.

2.8. TG Extends the Lifespan of C. elegans through Activating the Stress Response Signaling Pathway

DAF-16 activates the expression of proteins associated with the resistance to stress responses, which integrates multiple signaling pathways by shuttling from the cytoplasm to the nucleus [38]. To understand the mechanism(s) through which TG extends the lifespan of C. elegans through DAF-16/FOXO, lifespan assays were performed in daf-16(mgDf50) worms. We found that TG did not extend the lifespan of daf-16(mgDf50) worms (Figure 8D and Table S3), suggesting that daf-16 is required for the TG-mediated lifespan extension of C. elegans. A pretreatment with TG induced the nuclear accumulation of DAF-16 (Figure 8E,F) and increased the expression of daf-16 mRNA (Figure 8A). Cytoprotective genes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD-3) are upregulated by the IIS-dependent transcription factor DAF-16 [39]. A qPCR analysis showed that sod-3 was significantly upregulated in C. elegans exposed to TG (Figure 8A). These results suggested that the antiaging mechanisms of TG were closely related to DAF-16 and its downstream gene sod-3.

Heat shock factor-1 (HSF-1) is a master regulator of stress responses and longevity [40]. TG treatment improves the survival of C. elegans under stress conditions (Figure 4A). The most significant differential genes affected by HSF-1 in the RNA-Seq data were, therefore, investigated (Table 1). We utilized worms defective in hsf-1, hsf-1(sy441), for the lifespan assays. The findings suggested that TG treatment did not extend the lifespan of hsf-1(sy441) worms (Figure 8G and Table S3). The qPCR analysis showed that the expression of hsf-1 was significantly upregulated (Figure 8A). These results indicated that hsf-1 was required for the TG-mediated lifespan extension of C. elegans. HSF-1 can activate the expression of heat shock proteins (HSPs), which, in turn, promote longevity and prevent protein aggregation [41,42]. The qPCR analysis showed that hsp-16.2 is significantly upregulated in C. elegans exposed to TG (Figure 8A). Transgenic C. elegans expressing HSP-16.2::GFP were then used to examine the effects of TG on HSP-16.2 (Figure 8H,I). The results suggested that TG enhanced the expression of antioxidant stress-related genes, and TG extended the lifespan of C. elegans through activating the stress response signaling pathway.

2.9. Analysis of the Major Components of TG and Their Antiaging Effects

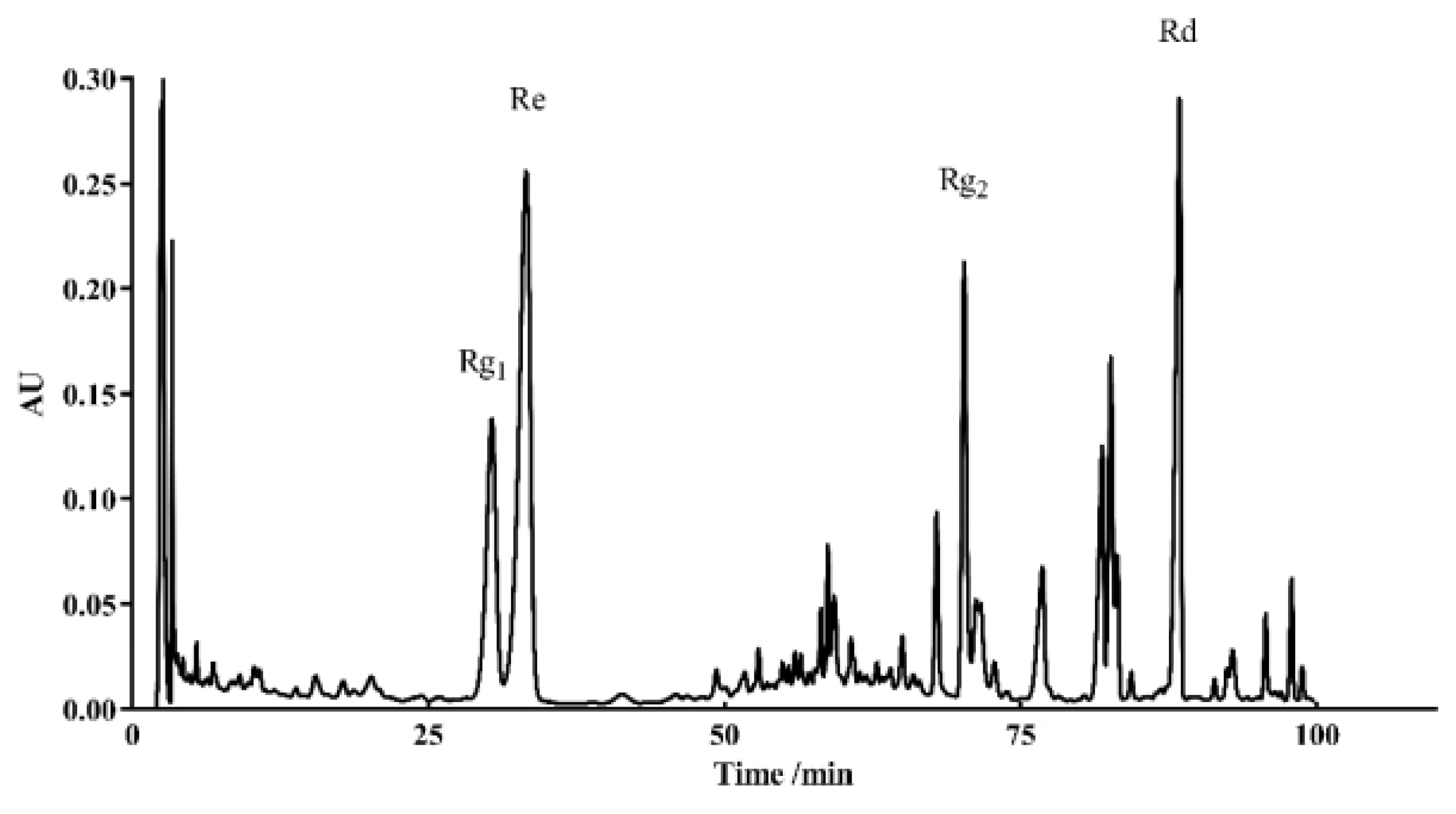

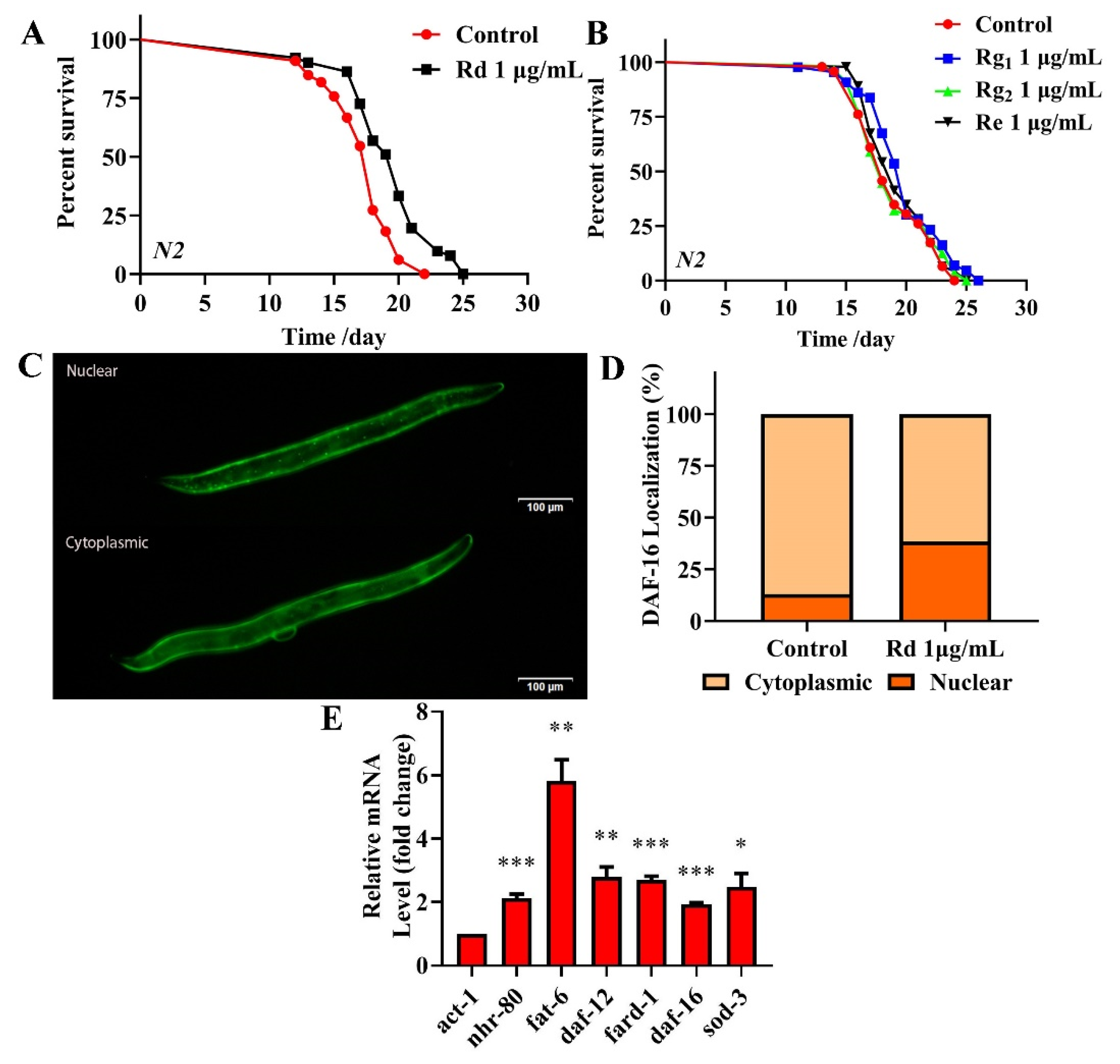

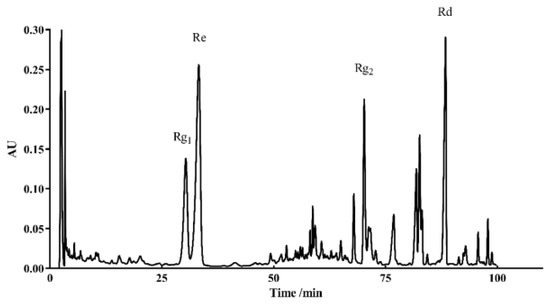

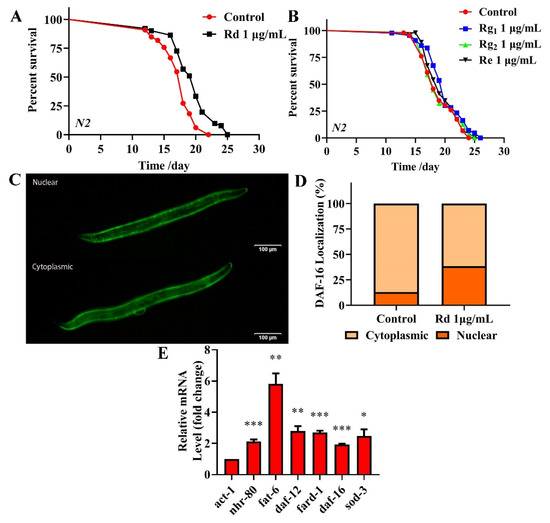

HPLC was used to identify the active components within TG. We observed the presence of ginsenoside Rg1, Re, Rg2 and Rd, which had relative abundance values of 10.91%, 24.61%, 20.05% and 7.64%, respectively (Figure 9 and Table 3). Rg1, Re, Rg2 and Rd were then analyzed for their antiaging effects to further investigate the effects of these components on the lifespan of C. elegans. Based on the HPLC analysis, the concentrations of the four ginsenosides in TG were approximately 1 μg/mL. The treatment with 1 μg/mL ginsenoside Rd significantly prolonged the mean lifespan of C. elegans by 13.26 ± 2.25% (Figure 10A and Table S3). Ginsenosides Rg1, Re and Rg2 had no significant effect on the mean lifespan (Figure 10B and Table S3).

Figure 9.

HPLC chromatograms of TG recorded at 203 nm.

Table 3.

Contents of the ginsenosides in TG.

Figure 10.

Effects of ginsenoside Rd, Rg1, Re and Rg2 on the lifespan of C. elegans. (A) The survival of C. elegans treated with 0.1% DMSO (control) and 1 μg/mL Rd, Rg1, Re and Rg2. Worms exposed to ginsenoside Rd survived longer than untreated worms (p < 0.05). (B) Ginsenoside Rg1, Re and Rg2 (1 μg/mL) did not extend the lifespan of C. elegans. (C,D) Fluorescence images of DAF-16::GFP expression in ginsenoside Rd-treated and untreated worms. (E) mRNA levels of nhr-80, daf-12 and daf-16 and the downstream genes fat-6, fard-1 and sod-3 in C. elegans treated with ginsenoside Rd. The data were analyzed using a Student’s t-test. The values were shown as the mean ± SEM, *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05.

To confirm that the antiaging mechanisms of ginsenoside Rd are similar to those of TG, we analyzed the expression of nhr-80, daf-12 and daf-16 and their downstream genes fat-6, fard-1 and sod-3 following the ginsenoside Rd treatment. The results showed that ginsenoside Rd significantly increased the expression of nhr-80, daf-12, daf-16, fat-6, fard-1 and sod-3 (Figure 10E). We next investigated the effects of ginsenoside Rd on DAF-16 using the TJ356 transgenic strain (expressing DAF-16::GFP). We found that the treatment with 1 μg/mL ginsenoside Rd significantly increased the transport of DAF-16 into the nucleus (Figure 10C,D), suggesting a similar mechanism of lifespan extension to that of TG.

3. Discussion

Due to the increasing age of the population globally, interest in the development of pharmacological approaches that can delay the process of aging and other aging pathologies has intensified. Recent studies have suggested that ginsenoside can prevent oxidative stress, metabolic disorders and neurodegenerative disease [43,44,45]. Previous studies have suggested that scavenging free radicals could reduce the occurrence of diseases and effectively prolong the lives of organisms [2,3]. We found that TG treatment extends the lifespan of C. elegans (Figure 1A). Previous studies have found that ginseng extract extends the lifespan of C. elegans through a resistance to oxidative stress (daf-16) and heat stress (hsp-1 and hsp-16.2) [16]. Our results were mutually verified with the above reports. The TG-mediated extension of the lifespan of C. elegans raised the possibility that TG effectively protects C. elegans from stress conditions through the reduction of ROS levels (Figure 4A–C). Lipofuscin is an age-related pigment, and it has been shown that lipofuscin accumulate in vivo with the increase of age in C. elegans [25]. Our results found that TG treatment significantly extended the lifespan of C. elegans through its ability to reduce intestinal lipofuscin (Figure 3A–D).

C. elegans is advantageous for antiaging research due to its complete genome sequence [24]. We investigated the possible mechanisms of TG on the lifespan extension of C. elegans through RNA-seq. We speculated that TG activates daf-12, nhr-80 and downstream insulin/IGF-1 signaling pathways (daf-2) such as daf-16 and hsf-1. DAF-16 is in the FOXO family of transcription factors and regulates the genes involved in promoting stress resistance, fat metabolism and influencing the lifespan [46]. We used traditional methods to verify the RNA-seq datasets. TG treatment activated DAF-16 and HSF-1 and upregulated antioxidant cellular defense genes (Figure 8A). More importantly, daf-16 and hsf-1 were required for TG-mediated lifespan extension. HSF-1 and DAF-16 activate the expression of heat shock proteins, which, in turn, promote longevity [28]. The expression of stress-response proteins such as HSP-16.2 were upregulated following TG treatment (Figure 8H,I). The overexpression of the cytoplasmic stress reporter hsp-16.2 could extend the lifespan of C. elegans [47]. These results showed that the beneficial effects of TG were mediated through its ability to prevent oxidative stress and regulate the lipid metabolism.

Gonadal longevity relies on the transcriptional activity of the steroid nuclear receptor DAF-12 and nuclear receptor NHR-80 [48]. NHR-80 is a nuclear transcription factor involved in the regulation of longevity in lysosomal signaling pathways [49]. Ginsenosides could increase the effects of cholesterol on reproduction, growth and development in C. elegans [14]. In this study, given the array of metabolic pathways identified (Figure 7), we speculated that TG mediated its effects on the aging of C. elegans through metabolism. Two major metabolic receptors, nhr-80 and daf-12, were significantly upregulated following TG treatment, confirming its ability to promote metabolism. After lipid staining, we further determined that TG can reduce fat accumulation (Figure 8B,C). In conclusion, TG extended the lifespan of C. elegans through multiple signaling pathways, including lipid metabolism and activating the stress response signaling pathway. Ginsenosides are bioactive components of Panax ginseng. TG as an extract of ginseng has a complex composition. HPLC was used to determine the bioactive compounds present in TG. Four ginsenosides were identified (Rg1, Re, Rg2 and Rd). Lifespan assays were performed for Rg1, Re, Rg2 and Rd (Figure 10A,B). Only Rd (1 μg/mL) prolonged the lifespan of C. elegans and significantly increased the expression of nhr-80, daf-12, daf-16, fat-6, fard-1 and sod-3 (Figure 10E). The pathways through which ginsenoside Rd promoted the longevity of C. elegans were therefore similar to those of TG.

In this study, we used the genome-wide transcriptional profiling of N2 worms to explore the mechanism of the TG-increased lifespan in C. elegans. We found that TG and ginsenoside Rd have similar mechanisms in prolonging the lifespan of C. elegans. Yet, further studies on the mechanisms of ginsenoside monomers remain to be conducted. This study provided new insight into further studying the antiaging effect of ginsenoside monomers in the future.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Strains and Chemicals

All strains were obtained from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC) and are shown in Table S1. The strains were grown and maintained on NGM plates seeded with E. coli OP50 (OP50). Total ginsenoside (TG) was purchased from Shanghai YuanYe Biotechnology and dissolved in H2O. Ginsenosides standard, Rd, Rg1, Re and Rg2 were purchased from Dalian Meilunbio and dissolved in DMSO and diluted to 0.01%. Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) was purchased from Aladdin (Shanghai, China). The samples were mixed with OP50 and coated on the surface of NGM overnight prior to use.

4.2. Lifespan Assays

Lifespan assays were performed at 20 °C. At least 80 synchronized L4 larvae worms were transferred to NGM plates (60 mm in diameter) containing OP50. The plates consisted of 50 μM 5-fluoro-2-deoxyuridine (FUDR, Aladdin, China) to prevent egg laying [50]. Synchronization was defined as experimental day 0. The worms were transferred to fresh plates with or without TG each day. The worms that did not respond to mechanical stimuli were scored as dead.

4.3. Antibacterial Assay

TG was diluted in 96-well microtiter plates with OP50. A total of 100 μL of bacterial suspension was incubated at 37 °C and read in a microplate reader (Infinity 200 Pro microplate reader, Tecan Trading, Switzerland). OD600 values were recorded every 2 h.

4.4. Body Length Measurements

Synchronized L4 worms were treated with 10 μg/mL TG for 3 days. The worms were exposed to heat treatment at 45 °C for 2 h prior to body length measurements [51]. The images were captured on an Olympus X71 fluorescence microscope (Olympus Co., Tokyo, Japan). The body lengths were measured from the top of the head to the tip of the tail using segmented line tools on ImageJ 15.2v (Rawak Software Inc., Stuttgart, Germany).

4.5. Reproduction Assays

A total of 5 synchronized L4 worms were randomly transferred to fresh NGM plates with or without 10 μg/mL TG. The worms were transferred onto fresh NGM plates every 24 h until reproduction ceased. The eggs were allowed to hatch and were counted at the L2 or L3 stage. The daily and total fecundity of each worm were recorded.

4.6. Body Bend Assay

Synchronized L4 worms were treated with 10 μg/mL TG for 3 days. The frequency of the body bending of the worms was counted for 10 s in M9 buffer under a microscope (BK1201, Chongqing, China). The number of sinusoidal curves made during locomotion was scored.

4.7. Pharyngeal Pumping Assay

Synchronized L4 worms were treated with 10 μg/mL TG for 8 days. The pharyngeal pump of worms was counted for 10 s under a microscope (BK1201, Chongqing, China).

4.8. Lipofuscin Assays

Synchronized L4 worms were treated with 10 μg/mL TG for 8 days. The images were captured using an Olympus X71 fluorescence microscope (Olympus Co., Tokyo, Japan). A total of 30 worms were measured and detected by red (Ex/Em 546/600 nm) or blue fluorescence (Ex/Em 350/460 nm) [52]. The worms were separated into Class I (dead or almost-dead individuals) and II (normal) with respect to the blue autofluorescence. Representative images of the two types of worms were recorded. The number of worms in each category were counted. Red fluorescence was measured on ImageJ, and the background signals were subtracted. The scores were the average age pigment fluorescence intensity levels of three independent trials.

4.9. Resistance to Thermal Stress

Thermal stress assays were performed as previously described [53]. NGM plates containing 30 animals per plate were treated with 10 μg/mL TG. Survival was measured after 4 h at 35 °C, followed by a recovery period of 12 h at 20 °C. The worms that did not respond to mechanical stimuli were considered dead.

4.10. Oxidative Stress Assays

Paraquat-induced oxidative stress assays were performed by incubating the worms with 10 μg/mL TG for 24 h [54]. The worms were then transferred to fresh NGM plates containing 50 mM paraquat (Aladdin, Shanghai, China) and 10 μg/mL TG. Worm survival was monitored every 12 h by touch-provoking movement. Worms that failed to respond to mechanical stimuli were considered dead. Log-rank tests were used for all statistical analyses.

4.11. ROS Assessments under Thermal Stress

The ROS levels were quantified using 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA) (Meilunbio, Dalian, China, Ex/Em 470/550 nm) [55]. After exposure to 10 μg/mL TG for 3 days, the worms were washed with cold M9 buffer and stained with 100 μM H2DCFDA at 37 ℃ for 30 min. The images were taken on an Olympus X71 microscope (Olympus Co., Tokyo, Japan). ImageJ was used to analyze the gray values. Background signals were subtracted.

4.12. Oil Red O Staining

Oil Red O (Aladdin, Shanghai, China) staining was performed as previously described with minor modifications [56]. Following the 10 μg/mL TG treatment, the worms were harvested by washing with cold M9 buffer. Oil red O solution (1%) in isopropanol (Aladdin, Shanghai, China) was diluted in 2% Triton X-100. The worms were fixed for 20 min, stained, washed with M9 buffer and placed on 2% agarose gel pads. ImageJ was used to quantify the mean intensity of Oil red O staining [52]. Background signals were subtracted.

4.13. Fluorescence Intensity Quantification Assays

To investigate the fluorescence intensity, transgenic worms (TJ375) were treated with 10 μg/mL TG for 3 days, anesthetized in 10 mM levamisole (Aladdin, Shanghai, China) and placed on a 2% agarose pad. The images were captured using an Olympus X71 microscope and quantified using ImageJ [52].

4.14. DAF-16 Nuclear Localization Assays

For the quantification of DAF-16::GFP localization, synchronized L4 larvae TJ356 worms expressing DAF-16::GFP were soaked in M9 buffer containing 10 μg/mL TG for 3 h and analyzed on a fluorescence microscope. The worms were grouped into two categories (cytoplasmic and nuclear) dependent on the localization of DAF-16::GFP. Representative images of transgenic TJ356 worms with cytosolic and nuclear DAF-16::GFP were taken, and the number of worms in each category was counted.

4.15. mRNA Extraction and Quantitative Real-Time PCR

The worms were treated with 10 μg/mL TG for 3 days, and the total RNA was extracted from ~2000 worms per experimental condition using the Trizol reagent (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China). First-stranded cDNA was prepared using commercial qPCR kits (Bimake, Houston, TX, USA). qPCR was performed using the Prism 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with SYBR® PCR kits (Bimake, Houston, TX, USA). qPCR consisted of 0.5-μM primers and 1 μL cDNA in a reaction volume of 20 μL. Relative fold changes in the transcript levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method. The expression of act-1 was used as an endogenous control to normalize the total mRNA levels. The primers are shown in Table S2.

4.16. RNA Sequencing

Wild-type C. elegans treated with 10 μg/mL TG at day 3 were assessed by the Biomarker Technology Company (Beijing, China). The WBcel235 genome was used as a reference for all the analyses. The gene expression was quantified as fragments per Kb of the transcript per million fragments mapped. The formula was as follows:

A differential expression analysis of the two samples was performed using edgeR. FDR < 0.05 and fold change > 1.5 were set as the thresholds for significant differential expression.

See the Supplementary Materials for more information.

4.17. HPLC Analysis of TG

The ginsenosides standards were obtained from Extrasynthese (Meilun, Dalian, China). The samples were dissolved in methanol and analyzed by HPLC (Waters Delta 600 system, Milford, MA, USA) using a ZORBAX C18 5 μm 4.6 × 250 mm column (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The water mobile phase was 0.1% phosphoric acid in water (A), and the organic phase was acetonitrile (B). An isocratic elution of 19% B lasted from 0 to 35 min; at 35–55 min, from 19% B to 29% B; 55–70 min, 29% B and 29–40% solvent B from 70 to 100 min; finally, the column returned to its starting condition at 10 min. The column flow was 1 mL/min, the temperature was kept at 25 °C and the absorbance at 203 nm was monitored.

4.18. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate. The lifespans were compared using GraphPad 8 software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). The p-values were calculated using the log-rank test. The numerical data were analyzed using a Student’s t-test. The values were shown as the mean ± SEM. The statistical differences were considered significant at p < 0.05 (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001).

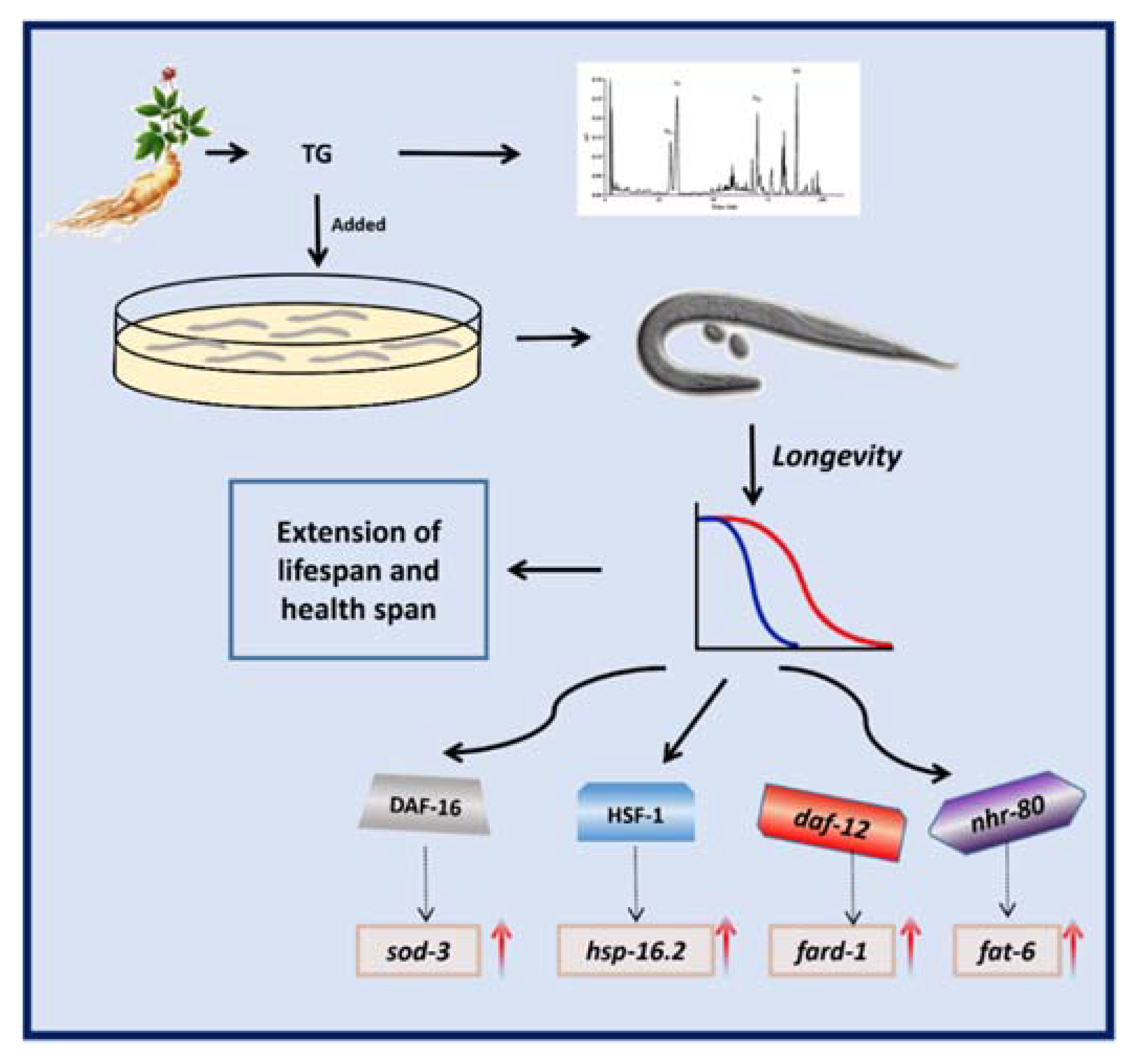

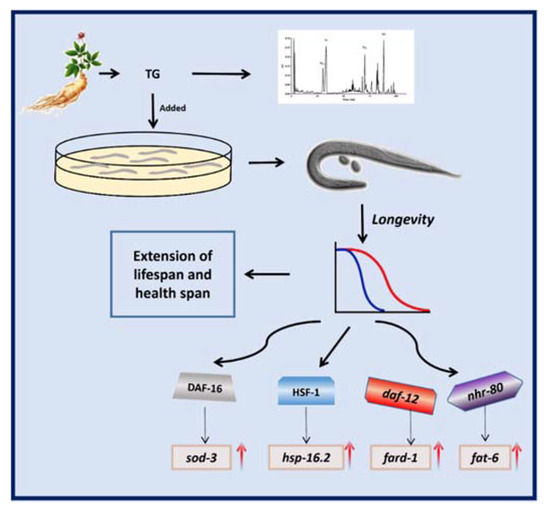

5. Conclusions

The results of the present study showed that TG increased the lifespan in C. elegans (Figure 11). In summary, we showed that TG promoted stress resistance and the lifespan of C. elegans. Moreover, a pretreatment with TG and ginsenoside Rd prolonged the longevity through the lipid metabolism and activated the stress response signaling pathway in C. elegans. Further studies are now required to investigate the beneficial effects of ginsenosides on the lifespan and as a potential treatment for age-related diseases.

Figure 11.

Schematic representation of the mechanism of the TG-extended lifespan.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms22189668/s1, Table S1. All the strains used in this study. Table S2. A list of the primers used for the quantitative real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction. Table S3. The lifespans of N2 and mutant C. elegans.

Author Contributions

Methodology, L.W. and S.G.; Resources, X.Y.; Software, W.G. and Z.X.; Visualization, X.Y. and D.L.; Writing–Original Draft, H.L. and X.Y. and Writing–Review and Editing, S.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Caenorhabditis Genetics Centre (CGC) supported by the NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440) and Caldwell Laboratory, University of Alabama for the supply of the C. elegans strains.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Harman, D. Free radical involvement in aging. Pathophysiology and therapeutic implications. Drugs Aging 1993, 3, 60–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Back, P.; Braeckman, B.P.; Matthijssens, F. ROS in aging Caenorhabditis elegans: Damage or signaling? Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2012, 2012, 608478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pietsch, K.; Saul, N.; Chakrabarti, S.; Stuerzenbaum, S.R.; Menzel, R.; Steinberg, C.E.W. Hormetins, antioxidants and prooxidants: Defining quercetin-, caffeic acid- and rosmarinic acid-mediated life extension in C. elegans. Biogerontology 2011, 12, 329–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, A.A.; Stolzing, A. The role of lipid metabolism in aging, lifespan regulation, and age-related disease. Aging Cell 2019, 18, e13048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ru, W.; Wang, D.; Xu, Y.; He, X.; Sun, Y.-E.; Qian, L.; Zhou, X.; Qin, Y. Chemical constituents and bioactivities of Panax ginseng (C. A. Mey.). Drug Discov. Ther. 2015, 9, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qi, L.-W.; Wang, C.-Z.; Yuan, C.-S. Isolation and analysis of ginseng: Advances and challenges. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2011, 28, 467–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attele, A.S.; Wu, J.A.; Yuan, C.-S. Ginseng pharmacology: Multiple constituents and multiple actions. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1999, 58, 1685–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.-K.; Song, I.-S. Interactions of ginseng with therapeutic drugs. Arch. Pharmacal. Res. 2019, 42, 862–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irfan, M.; Kim, M.; Rhee, M.H. Anti-platelet role of Korean ginseng and ginsenosides in cardiovascular diseases. J. Ginseng Res. 2020, 44, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, C.; Santangelo, R. Panax ginseng and Panax quinquefolius: From pharmacology to toxicology. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2017, 107, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, M.; Ye, Y.; Xiao, L.; Duan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H. Anticancer effects of ginsenoside Rg3 (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2017, 39, 507–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Im, D.-S. Pro-Resolving Effect of Ginsenosides as an Anti-Inflammatory Mechanism of Panax ginseng. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yao, F.; Xue, Q.; Li, K.; Cao, X.; Sun, L.; Liu, Y. Phenolic Compounds and Ginsenosides in Ginseng Shoots and Their Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Capacities in LPS-Induced RAW264.7 Mouse Macrophages. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lee, J.-H.; Choi, S.-H.; Kwon, O.-S.; Shin, T.-J.; Lee, J.; Lee, B.-H.; Yoon, I.-S.; Pyo, M.K.; Rhim, H.; Lim, Y.-H.; et al. Effects of Ginsenosides, Active Ingredients of Panax ginseng, on Development, Growth, and Life Span of Caenorhabditis elegans. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2007, 30, 2126–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, J.-H.; Ahn, J.-Y.; Shin, T.-J.; Choi, S.-H.; Lee, B.-H.; Hwang, S.-H.; Kang, J.-Y.; Kim, H.-J.; Park, C.-W.; Nah, S.-Y. Effects of Minor Ginsenosides, Ginsenoside Metabolites, and Ginsenoside Epimers on the Growth of Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Ginseng Res. 2011, 35, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sandner, G.; Mueller, A.S.; Zhou, X.; Stadlbauer, V.; Schwarzinger, B.; Schwarzinger, C.; Wenzel, U.; Maenner, K.; Van Der Klis, J.D.; Hirtenlehner, S.; et al. Ginseng Extract Ameliorates the Negative Physiological Effects of Heat Stress by Supporting Heat Shock Response and Improving Intestinal Barrier Integrity: Evidence from Studies with Heat-Stressed Caco-2 Cells, C. elegans and Growing Broilers. Molecules 2020, 25, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhai, L.; Sun, L.; Zhao, D.; Wang, Z.; Li, X. Ginsenoside extract from ginseng extends lifespan and health span in Caenorhabditis elegans. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 6793–6808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Kim, J.; Park, J.Y.; Kang, K.S.; Park, J.H.; Hwang, G.S. Processed Panax ginseng, sun ginseng, inhibits the differentiation and proliferation of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes and fat accumulation in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Ginseng Res. 2017, 41, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zheng, S.; Ding, A.-J.; Li, G.-P.; Wu, G.-S.; Luo, H.-R. Drug Absorption Efficiency in Caenorhbditis elegans Delivered by Different Methods. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e56877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garigan, D.; Hsu, A.L.; Fraser, A.G.; Kamath, R.S.; Ahringer, J.; Kenyon, C. Genetic analysis of tissue aging in Caenorhabditis elegans: A role for heat-shock factor and bacterial proliferation. Genetics 2002, 161, 1101–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Huang, Y.; Yin, G.; Wang, J.; Wang, P.; Chen, Z.-Y.; Wang, T.; Ren, G. Antimicrobial activities of Asian ginseng, American ginseng, and notoginseng. Phytother. Res. 2020, 34, 1226–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jasienska, G. Reproduction and lifespan: Trade-offs, overall energy budgets, intergenerational costs, and costs neglected by research. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2009, 21, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, D.; Mouchiroud, L.A.; Andreux, P.; Katsyuba, E.; Moullan, N.; Nicolet-Dit-Félix, A.A.; Williams, E.; Jha, P.; Sasso, G.L.; Huzard, D.; et al. Urolithin A induces mitophagy and prolongs lifespan in C. elegans and increases muscle function in rodents. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 879–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herndon, L.A.; Wolkow, C.; Hall, D.H. WormAtlas Aging Handbook-Introduction to Aging in C. elegans; WormAtlas: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pincus, Z.; Mazer, T.C.; Slack, F.J. Autofluorescence as a measure of senescence in C. elegans: Look to red, not blue or green. Aging 2016, 8, 889–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brunk, U.T.; Terman, A. Lipofuscin: Mechanisms of age-related accumulation and influence on cell function. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2002, 33, 611–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, J.; Li, T.; Liu, R.H. Blueberry extract promotes longevity and stress tolerance via DAF-16 in Caenorhabditis elegans. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 5273–5282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yu, X.; Li, C.; Ma, L.; Zhao, Z.; Guan, S.; Wang, L. Caffeic acid protects against Abeta toxicity and prolongs lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans models. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 1219–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, D. Aging: A Theory Based on Free Radical and Radiation Chemistry. J. Gerontol. 1956, 11, 298–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Reczek, C.R.; Birsoy, K.; Kong, H.; Martinez-Reyes, I.; Wang, T.; Gao, P.; Sabatini, D.M.; Chandel, N.S. A CRISPR screen identifies a pathway required for paraquat-induced cell death. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017, 13, 1274–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belhadj Slimen, I.; Najar, T.; Ghram, A.; Dabbebi, H.; Ben Mrad, M.; Abdrabbah, M. Reactive oxygen species, heat stress and oxidative-induced mitochondrial damage. A review. Int. J. Hyperth. 2014, 30, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, M.; Hisamoto, N.; Iino, Y.; Yamamoto, M.; Ninomiya-Tsuji, J.; Matsumoto, K. A Caenorhabditis elegans JNK signal transduction pathway regulates coordinated movement via type-D GABAergic motor neurons. EMBO J. 1999, 18, 3604–3615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jahn, A.; Scherer, B.; Fritz, G.; Honnen, S. Statins Induce a DAF-16/Foxo-dependent Longevity Phenotype via JNK-1 through Mevalonate Depletion in C. elegans. Aging Dis. 2020, 11, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McCormick, M.; Chen, K.; Ramaswamy, P.; Kenyon, C. New genes that extend Caenorhabditis elegans’ lifespan in response to reproductive signals. Aging Cell 2011, 11, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goudeau, J.; Bellemin, S.; Toselli-Mollereau, E.; Shamalnasab, M.; Chen, Y.; Aguilaniu, H. Fatty Acid Desaturation Links Germ Cell Loss to Longevity Through NHR-80/HNF4 in C. elegans. PLoS Biol. 2011, 9, e1000599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Farias-Pereira, R.; Kim, E.; Park, Y. Cafestol increases fat oxidation and energy expenditure in Caenorhabditis elegans via DAF-12-dependent pathway. Food Chem. 2020, 307, 125537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Włodarczyk, M.; Nowicka, G. Obesity, DNA Damage, and Development of Obesity-Related Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Chen, W.-D.; Wang, Y.-D. DAF-16/FOXO Transcription Factor in Aging and Longevity. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tullet, J.; Hertweck, M.; An, J.H.; Baker, J.; Hwang, J.Y.; Liu, S.; Oliveira, R.D.P.; Baumeister, R.; Blackwell, T.K. Direct Inhibition of the Longevity-Promoting Factor SKN-1 by Insulin-like Signaling in C. elegans. Cell 2008, 132, 1025–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chiang, W.C.; Ching, T.T.; Lee, H.C.; Mousigian, C.; Hsu, A.L. HSF-1 regulators DDL-1/2 link insulin-like signaling to heat-shock responses and modulation of longevity. Cell 2012, 148, 322–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cohen, E.; Bieschke, J.; Perciavalle, R.M.; Kelly, J.W.; Dillin, A. Opposing Activities Protect Against Age-Onset Proteotoxicity. Science 2006, 313, 1604–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, A.-L.; Murphy, C.T.; Kenyon, C. Regulation of Aging and Age-Related Disease by DAF-16 and Heat-Shock Factor. Science 2003, 300, 1142–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Song, J.H.; Lee, H.-J.; Kang, K.S. Procyanidin C1 Activates the Nrf2/HO-1 Signaling Pathway to Prevent Glutamate-Induced Apoptotic HT22 Cell Death. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Ma, C.; Yan, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X.; Rausch, W.-D. Ginsenoside Rd and ginsenoside Re offer neuroprotection in a novel model of Parkinson’s disease. Am. J. Neurodegener. Dis. 2016, 5, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.; An, X.; Lang, P.; Wang, F.; Xie, Y. Ginsenoside Rd contributes the attenuation of cardiac hypertrophy in vivo and in vitro. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 109, 1016–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tullet, J.M.A. DAF-16 target identification in C. elegans: Past, present and future. Biogerontology 2015, 16, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fonte, V.; Kipp, D.R.; Yerg, J.; Merin, D.; Forrestal, M.; Wagner, E.; Link, C.D. Suppression of in vivo beta-amyloid peptide toxicity by overexpression of the HSP-16.2 small chaperone protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 784–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Antebi, A. Regulation of longevity by the reproductive system. Exp. Gerontol. 2013, 48, 596–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Folick, A.; Oakley, H.; Yu, Y.; Armstrong, E.H.; Kumari, M.; Sanor, L.; Moore, D.D.; Ortlund, E.; Zechner, R.; Wang, M.C. Lysosomal signaling molecules regulate longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 2015, 347, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lu, M.; Tan, L.; Zhou, X.-G.; Yang, Z.-L.; Zhu, Q.; Chen, J.-N.; Wu, G.S. Secoisolariciresinol Diglucoside Delays the Progression of Aging-Related Diseases and Extends the Lifespan of Caenorhabditis elegans via DAF-16 and HSF-1. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 1293935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surco-Laos, F.; Cabello, J.; Gómez-Orte, E.; Manzano, S.G.; González-Paramás, A.M.; Santos-Buelga, C.; Dueñas, M.; Duenas-Paton, M. Effects of O-methylated metabolites of quercetin on oxidative stress, thermotolerance, lifespan and bioavailability on Caenorhabditis elegans. Food Funct. 2011, 2, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband, W.S.; Eliceiri, K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumsta, C.; Chang, J.T.; Schmalz, J.; Hansen, M. Hormetic heat stress and HSF-1 induce autophagy to improve survival and proteostasis in C. elegans. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jia, W.; Peng, Q.; Su, L.; Yu, X.; Ma, C.W.; Liang, M.; Yin, X.; Zou, Y.; Huang, Z. Novel Bioactive Peptides from Meretrix meretrix Protect Caenorhabditis elegans against Free Radical-Induced Oxidative Stress through the Stress Response Factor DAF-16/FOXO. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ogawa, T.; Kodera, Y.; Hirata, D.; Blackwell, T.K.; Mizunuma, M. Natural thioallyl compounds increase oxidative stress resistance and lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans by modulating SKN-1/Nrf. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 21611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lee, D.; An, S.W.A.; Jung, Y.; Yamaoka, Y.; Ryu, Y.; Goh, G.Y.S.; Beigi, A.; Yang, J.-S.; Jung, G.Y.; Ma, D.K.; et al. MDT-15/MED15 permits longevity at low temperature via enhancing lipidostasis and proteostasis. PLoS Biol. 2019, 17, e3000415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).