KYNA Derivatives with Modified Skeleton; Hydroxyquinolines with Potential Neuroprotective Effect †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Synthesis of Functionalized and Heteroatom Containing KYNA Derivatives

2.1. Nitrogen-Containing Ring Systems

2.1.1. Pyridine- and Pyrimidine-Fused Ring Systems

2.1.2. N-Bridgehead Annulations

2.1.3. Five-Membered B-Ring Derivatives

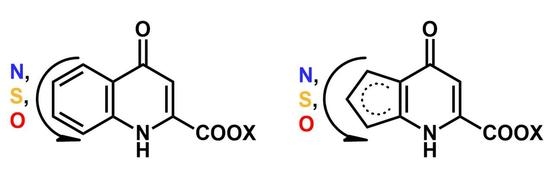

2.2. Sulfur-Containing Ring Systems

2.3. Oxygen-Containing Ring Systems

2.4. New Aspects on the Synthesis of KYNA Derivatives

3. Mannich-Type Transformations of KYNA and Its Substituted Derivatives

3.1. C-3 Substitutions of KYNA Derivatives

3.2. Aminoalkylations of Hydroxy-KYNA Derivatives

3.2.1. Derivatives with Structural Similarities to 1-Napthol

3.2.2. Derivatives with Structural Similarities to 2-Napthol

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Acetonitrile | MeCN |

| Blood-brain barrier | BBB |

| 1,2-Dichlorobenzene | DCB |

| Diethylacetylene dicarboxylate | DEAD |

| Diethyl fumarate | DEF |

| N,N′-Diisopropylcarbodiimide | DIC |

| Dimethylacetylene dicarboxylate | DMAD |

| N,N-Dimethylformamide | DMF |

| Diphenyl ether | Ph2O |

| 1,3-Bis(diphenylphosphino)propane | dppp |

| Electron-donating groups | EDG |

| 1-Hydroxybenzotriazole hydrate | HOBt |

| Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide | NAD |

| Modified Mannich reaction | mMr |

| Polyphosphoric acid | PPA |

| Tetraphenylporphin | tPorphin |

| TNF-stimulated gene 6 protein | TSG-6 |

| p-Toluenesulfonic acid | pTsOH |

| Triethylamine | TEA |

| Tryptophan | TRP |

| Tumor necrosis factor alpha | TNF-α |

References

- Rózsa, E.; Robotka, H.; Vécsei, L.; Toldi, J. The Janus-face kynurenic acid. J. Neural Transm. 2008, 115, 1087–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, T.W. Kynurenic acid antagonists and kynurenine pathway inhibitors. Expert Opin. Inv. Drug. 2001, 10, 633–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Németh, H.; Toldi, J.; Vécsei, L. Role of kynurenines in the central and peripheral nervous systems. Curr. Neurovasc. Res. 2005, 2, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Németh, H.; Toldi, J.; Vécsei, L. Kynurenines, Parkinson’s disease and other neurodegenerative disorders: Preclinical and clinical studies. J. Neural Transm. Supp. 2006, 70, 285–304. [Google Scholar]

- Sas, K.; Robotka, H.; Toldi, J.; Vécsei, L. Mitochondria, metabolic disturbances, oxidative stress and the kynurenine system, with focus on neurodegenerative disorders. J. Neurol. Sci. 2007, 257, 221–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gigler, G.; Szénási, G.; Simó, A.; Lévay, G.; Hársing, L.G., Jr.; Sas, K.; Vécsei, L.; Toldi, J. Neuroprotective effect of L-kynurenine sulfate administered before focal cerebral ischemia in mice and global cerebral ischemia in gerbils. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2007, 564, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luchowska, E.; Luchowski, P.; Sarnowska, A.; Wielosz, M.; Turski, W.A.; Urbańska, E.M. Endogenous level of kynurenic acid and activities of kynurenine aminotransferases following transient global ischemia in the gerbil hippocampus. Pol. J. Pharmacol. 2003, 55, 443–447. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Harrison, B.L.; Baron, B.M.; Cousino, D.M.; McDonald, I.A. 4-[(Carboxymethyl)oxy]- and 4-[(carboxymethyl)amino]-5,7-dichloroquinoline-2-carboxylic acid: New antagonists of the strychnine-insensitive glycine binding site on the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor complex. J. Med. Chem. 1990, 33, 3130–3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edmont, D.; Rocher, R.; Plisson, C.; Chenault, J. Synthesis and evaluation of quinoline carboxyguanidines as antidiabetic agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2000, 16, 1831–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonina, F.P.; Arenare, L.; Ippolito, R.; Boatto, G.; Battaglia, G.; Bruno, V.; De Caprariis, P. Synthesis, pharmacokinetics and anticonvulsant activity of 7-chlorokynurenic acid prodrugs. Int. J. Pharm. 2000, 202, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredini, S.; Pavan, B.; Vertuani, S.; Scaglianti, M.; Compagnone, D.; Biondi, C.; Scatturin, A.; Tanganelli, S.; Ferraro, L.; Prasad, P.; et al. Design, synthesis and activity of ascorbic acid prodrugs of nipecotic, kynurenic and diclophenamic acids, liable to increase neurotropic activity. J. Med. Chem. 2002, 45, 559–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manfredini, S.; Vertuani, S.; Pavan, B.; Vitali, F.; Scaglianti, M.; Bortolotti, F.; Biondi, C.; Scatturin, A.; Prasad, P.; Dalpiaz, A. Design, synthesis and in vitro evaluation on HRPE cells of ascorbic and 6-bromoascorbic acid conjugates with neuroactive molecules. Bioorgan. Med. Chem. 2004, 12, 5453–5463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yielding, K.L.; Nichols, A.C. Anticonvulsant activity of antagonists for the NMDA-associated glycine binding site. Mol. Chem. Neuropathol. 1993, 19, 269–282. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, T.W. Inhibitors of the kynurenine pathway. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2000, 35, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, A.C.; Yielding, K.L. Anticonvulsant activity of 4-urea-5,7-dichlorokynurenic acid derivatives that are antagonists at the NMDA-associated glycine binding site. Mol. Chem. Neuropathol. 1998, 35, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Füvesi, J.; Somlai, C.; Németh, H.; Varga, H.; Kis, Z.; Farkas, T.; Károly, N.; Dobszay, M.; Penke, Z.; Penke, B.; et al. Comparative study on the effects of kynurenic acid and glucosamine-kynurenic acid. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2004, 77, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Sun, F.; Li, Y.; Sun, X.; Liu, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, L.H.; Ye, X.S.; Xiao, J. Rapid Synthesis of Iminosugar Derivatives for Cell-Based In Situ Screening: Discovery of “Hit” Compounds with Anticancer Activity. ChemMedChem 2007, 2, 1594–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brik, A.; Lin, Y.C.; Elder, J.; Wong, C.H. A quick diversity-oriented amide forming reaction coupled with in situ screening as an approach to identify optimal p-subsite residues of HIV-1 protease inhibitors. Chem. Biol. 2002, 9, 891–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tossi, A.; Benedetti, F.; Norbedo, S.; Skrbec, D.; Berti, F.; Romeo, D. Small hydroxyethylene-based peptidomimetics inhibiting both HIV-1 and C. albicans aspartic proteases. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2003, 11, 4719–4727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knyihár-Csillik, E.; Mihály, A.; Krisztin-Péva, B.; Robotka, H.; Szatmári, I.; Fülöp, F.; Toldi, J.; Csillik, B.; Vécsei, L. The kynurenate analog SZR-72 prevents the nitroglycerol-induced increase of c-fos immunoreactivity in the rat caudal trigeminal nucleus: Comparative studies of the effects of SZR-72 and kynurenic acid. Neurosci. Res. 2008, 61, 429–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fülöp, F.; Szatmári, I.; Vámos, E.; Zádori, D.; Toldi, J.; Vécsei, L. Syntheses, transformations and pharmaceutical applications of kynurenic acid derivatives. Curr. Med. Chem. 2009, 16, 4828–4842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sako, M. Category 2, Hetarenes and Related Ring Systems; Yamamoto, Y., Shinkai, I., Eds.; Product Class. 19: Pyridopyrimidines; Thieme Verlagsgruppe: Stuttgart, Germany; New York, NY, USA; New Delhi, India, 2004; pp. 1155–1267. [Google Scholar]

- Conrad, M.; Limpach, L. Synthesen von Chinolinderivaten mittelst Acetessigester. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1887, 20, 944–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, M.; Limpach, L. Ueber das γ-Oxychinaldin und dessen Derivate. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1887, 20, 948–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hauser, C.R.; Reynolds, G.A. Reactions of β-keto esters with aromatic amines. Synthesis of 2-and-4-hydroxyquinoline derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1948, 70, 2402–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, A.A.; Theobald, R.S.; Williamson, W. Derivatives of 2-alkoxy-8-amino-1:5-naphthyridines. J. Chem. Soc. 1954, 2357–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, S.; Haneda, T.; Hata, K.; Inoue, S.; Matsukura, M.; Nakamoto, K.; Tanaka, K.; Tsukada, I.; Ueda, N.; Watanabe, N. Novel Antifungal Agent Comprising Heterocyclic Compound. Patent WO2005033079A1, 14 April 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, J.; Broekema, M.; Feng, J.; Liu, C.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y. Alkene Compounds as Farnesoid X Receptor Modulators. Patent WO2019089670A1, 9 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Abe, S.; Haneda, T.; Inoue, S.; Matsukura, M.; Nakamoto, K.; Sagane, K.; Tanaka, K.; Tsukada, I.; Ueda, N. Novel Antimalaria Agent Containing Heterocyclic Compound. Patent WO2006016548A1, 16 February 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, J.; Liu, C.; Huang, Y. Alkene Spirocyclic Compounds as Farnesoid X Receptor Modulators. Patent WO2019089665A1, 9 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Vasil’ev, L.S.; Surzhikov, F.E.; Baranin, S.V.; Dorokhov, V.A. Trifluoromethyl-substituted 1,6-naphthyridines and pyrido[4,3-d]pyrimidines. Russ. Chem Bull. 2013, 62, 1255–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasil’ev, L.S.; Surzhikov, F.E.; Azarevich, O.G.; Bogdanov, V.S.; Dorokhov, V.A. Synthesis of 4-hydroxy- and 3-aryl-4-amino- 2-trifluoromethylpyridines. Russ. Chem. Bull. 1996, 45, 2574–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, M.D.; Bagal, S.K.; Gibson, K.R.; Omoto, K.; Ryckmans, T.; Skerratt, S.E.; Stupple, P.A. Pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine Derivatives as Inhibitors of Tropomyosin-Related Kinases. Patent WO2012137089A1, 11 October 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, M.D.; Bagal, S.K.; Gibson, K.R.; Omoto, K.; Ryckmans, T.; Skerratt, S.E.; Stupple, P.A. Pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine Tropomysin-Related Kinase Inhibitors. Patent US8846698B2, 30 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser, C.R.; Weiss, M.J. Cyclization Of 2-Aminopyridine Derivatives To Form 1,8-Naphthyridines. J. Org. Chem. 1949, 14, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, L.; Su, W.; Zhou, M. Substituent effect of ancillary ligands on the luminescence of bis [4,6-(di-fluorophenyl)-pyridinato-N,C2′]iridium(III) complexes. Dalton Trans. 2012, 31, 9373–9381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carboni, S.; Da Settimo, A.; Bertini, D.; Ferrarini, P.L.; Livi, O.; Mori, C.; Tonetti, I. Gazz. Chim. Ital. 1972, 102, 253–264. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrand, Y.; Kendhale, A.M.; Garric, J.; Kauffmann, B.; Huc, I. Parallel and antiparallel triple helices of naphthyridine oligoamides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 1778–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateus, P.; Chandramouli, N.; Mackereth, C.D.; Kauffmann, B.; Ferrand, Y.; Huc, I. Allosteric recognition of homomeric and heteromeric pairs of monosaccharides by a foldamer capsule. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 5797–5805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gole, B.; Kauffmann, B.; Maurizot, V.; Huc, I.; Ferrand, Y. Light-controlled conformational switch of an aromatic oligoamide foldamer. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 8063–8067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Gan, Q.; Wicher, B.; Ferrand, Y.; Huc, I. Directional threading and sliding of a dissymmetrical foldamer helix on dissymmetrical axles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 4205–4209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Kauffmann, B.; Ferrand, Y.; Huc, I. Selective encapsulation of disaccharide xylobiose by an aromatic foldamer helical capsule. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 13542–13546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, N.; Kato, M.; Dohmori, R. [Synthesis of antimicrobial agents. II. Synthesis of 1,8-naphthyridine derivatives and their activities against Trichomonas vaginalis (author’s transl)]. Yakugaku Zasshi. 1979, 99, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Srinivasan, A.; Broom, A.D. Pyridopyrimidines. 10. Nucleophilic substitutions in the pyrido[3,2-d]pyrimidine series. J. Org. Chem. 1979, 44, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosowsky, A.; Forsch, R.A.; Queener, S.F. 2,4-Diaminopyrido[3,2-d]pyrimidine Inhibitors of Dihydrofolate Reductase from Pneumocystis carinii and Toxoplasma gondii. J. Med. Chem. 1995, 38, 2615–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desforges, G.; Gaillard, P.; Montagne, C.; Pomel, V.; Quattropani, A. 4-Morpholino-pyrido[3,2-d]pyrimidines. Patent WO2010037765A2, 8 April 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Shim, J.L.; Niess, R.; Broom, A.D. Acylation of some 6-aminouracil derivatives. J. Org. Chem. 1972, 37, 578–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogura, H.; Sakaguchi, M. A novel synthesis of 5-oxo- and 7-oxo-pyrido[2,3-d]pyrimidines. Chem. Lett. 1972, 1, 657–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komkov, A.V.; Dorokhov, V.A. Simple synthesis of alkyl 5-oxo-5, 8-dihydropyrido [2, 3-d] pyrimidine-7-carboxylates from 5-acetyl-4-aminopyrimidines. Russ. Chem Bull. 2002, 51, 1875–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassis, R.; Tapia, R.; Valderrama, A. Synthesis of 4 (1H)-quinolones by thermolysis of arylaminomethylene Meldrum’s acid derivatives. Synth. Commun. 1985, 15, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, S.B.; Fatema, S.; Patil, R.B.; Sangshetti, J.N.; Farooqui, M. Pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-4-ones: Ligand-based Design, Synthesis, and Evaluation as an Anti-inflammatory Agent. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2017, 54, 3299–3313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Shu, W.-M.; Yu, S.-B.; Ni, F.; Gao, M.; Wu, A.-X. Auto-tandem catalysis: Synthesis of 4H-pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-4-ones via copper-catalyzed aza-Michael addition–aerobic dehydrogenation–intramolecular amidation. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 1729–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bonacorso, H.G.; Righi, F.J.; Rodrigues, I.R.; Cechinel, C.A.; Costa, M.B.; Wastowski, A.D.; Martins, M.A.P.; Zanatta, N. New efficient approach for the synthesis of 2-alkyl(aryl) substituted 4H-pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-4-ones. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2006, 43, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roslan, I.I.; Lim, Q.-X.; Han, A.; Chuah, G.-K.; Jaenicke, S. Solvent-Free Synthesis of 4H-Pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-4-ones Catalyzed by BiCl3: A Green Route to a Privileged Backbone. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 2351–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathavan, S.; Durai Raj, A.K.; Yamajala, R.B.R.D. A Metal-free Approach for the Synthesis of Privileged 4H-pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-4-one Derivatives over a Heterogeneous Catalyst. ChemistrySelect 2019, 4, 10737–10741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Li, N.; Wu, C.; Guan, A.; Li, Y.; Peng, Z.; He, M.; Li, J.; Gong, Z.; Huang, L.; et al. Discovery of pyridopyrimidinones as potent and orally active dual inhibitors of PI3K/mTOR. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Ma, Y.; Sun, Y.; Ma, C.; Wang, Y.; Ren, X.; Huang, G. Catalyst-free synthesis of alkyl 4-oxo-4H-pyrido [1, 2-a] pyrimidine-2-carboxylate derivatives on water. Tetrahedron 2014, 70, 2761–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackaby, W.; Brookfield, F.; Bubert, C.; Hardick, D.; Ridgill, M.; Shepherd, J.; Thomas, E. METTL3 Inhibitory Compounds. Patent WO2020201773A1, 8 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kinzel, O.D.; Ball, R.G.; Donghi, M.; Maguire, C.K.; Muraglia, E.; Pesci, S.; Rowley, M.; Summa, V. 3-Hydroxy-4-oxo-4H-pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidine-2-carboxylates—fast access to a heterocyclic scaffold for HIV-1 integrase inhibitors. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008, 49, 6556–6558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donghi, M.; Kinzel, O.D.; Summa, V. 3-Hydroxy-4-oxo-4H-pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidine-2-carboxylates—A new class of HIV-1 integrase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 1930–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraglia, E.; Kinzel, O.; Gardelli, C.; Crescenzi, B.; Donghi, M.; Ferrara, M.; Nizi, E.; Orvieto, F.; Pescatore, G.; Laufer, R.; et al. Design and Synthesis of Bicyclic Pyrimidinones as Potent and Orally Bioavailable HIV-1 Integrase Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 861–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinzel, O.D.; Monteagudo, E.; Muraglia, E.; Orvieto, F.; Pescatore, G.; Rico Ferreira, M.; Rowley, M.; Summa, V. The synthesis of tetrahydropyridopyrimidones as a new scaffold for HIV-1 integrase inhibitors. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007, 48, 6552–6555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crescenzi, B.; Kinzel, O.; Muraglia, E.; Orvieto, F.; Pescatore, G.; Rowley, M.; Summa, V. Patent WO2004058757A1, 15 July 2004.

- Koch, U.; Attenni, B.; Malancona, S.; Colarusso, S.; Conte, I.; Di Filippo, M.; Harper, S.; Pacini, B.; Giomini, C.; Thomas, S.; et al. 2-(2-Thienyl)-5, 6-dihydroxy-4-carboxypyrimidines as inhibitors of the hepatitis C virus NS5B polymerase: Discovery, SAR, modeling, and mutagenesis. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 1693–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.-L.; Zhou, H.; Gauthier, D.R., Jr.; Askin, D. Efficient synthesis of functionalized pyrimidones via microwave-accelerated rearrangement reaction. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 1315–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisler, M.; Zupet, R. An improved synthesis of dimethyl diacetoxyfumarate and its condensation with heterocyclic amines. Org. Prep. Proced. Int. 1990, 22, 532–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E.D.; Vandegraaff, N.; Le, G.; Choi, N.; Issa, W.; Macfarlane, K.; Thienthong, N.; Winfield, L.J.; Coates, J.A.V.; Lu, L.; et al. Design of a series of bicyclic HIV-1 integrase inhibitors. Part 1: Selection of the scaffold. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 5913–5917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deadman, J.J.; Jones, E.D.; Le, G.T.; Rhodes, D.I.; Thienthong, N.; Vandegraff, N.; Winfield, L.J. Compounds Having Antiviral Properties. Patent WO2010000032A1, 7 January 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Le, G.; Vandegraff, N.; Rhodes, D.I.; Jones, E.D.; Coates, J.A.V.; Lu, L.; Li, X.; Yu, C.; Feng, X.; Deadman, J.J. Discovery of potent HIV integrase inhibitors active against raltegravir resistant viruses. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 5013–5018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, D.G.; Rees, C.W. Reaction of 1,2,4-triazolo[4,3-a]pyridine with dimethyl acetylenedicarboxylate: New structures and mechanisms. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Comm. 1982, 21, 1280–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.-F.; Steinbock, R.; Münch, A.; Stalke, D.; Ackermann, L. Manganese-Catalyzed Carbonylative Annulations for Redox-Neutral Late-Stage Diversification. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 5384–5388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huisgen, R.; Frauenberg, K.; Sturm, H.J. Cycloadditionen von pyridyl-und pyrimidyl-aziden. Tetrahedron Lett. 1969, 30, 2589–2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergnes, G.; Chabala, J.C.; Dhanak, D.; Knight, S.D.; Mcdonald, A.; Morgans, D.J.; Zhou, H.-J. Compounds, Compositions and Methods. Patent WO2004064741A2, 5 August 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ang, K.H.; Cox, M.; Lawrance, W.D.; Prager, R.; Smith, J.A.; Staker, W. Triplet lifetimes, solvent, and intramolecular capture of isoxazolones. Aust. J. Chem. 2004, 57, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mátyus, P.; Ősapay, K.; Gabányi, Z.; Kasztreiner, E.; Sohár, P. Kísérletek amino-diazinok két nukleofil reakciójának kvantumkémiai értelmezésére. Kem. Kozl. 1986, 66, 203–212. [Google Scholar]

- Mátyus, O.; Szilágyi, G.; Kasztreiner, E.; Rabloczky, G.; Sohár, P. Some aspects of the chemistry of pyrimido[1,2-B]pyridazinones. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1988, 25, 1535–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerorge, V.M.; Khetan, K.S.; Gupta, K.R. Advances in Heterocyclic Chemistry; Keritzky, R.A., Boulton, J.A., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA; San Francisco, CA, USA; London, UK, 1976; Volume 19, p. 280. [Google Scholar]

- Boer, R.F.; Petra, D.G.I.; Wanner, M.J.; Boesaart, A.; Koomen, G.J. Nucleos. Nucleot. 1995, 14, 349–352. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K.-C.; Huang, H.-S. Synthesis of methyl 4 (1H)-oxopyrimido[1,2-a]perimidine-2-carboxylate. Arch. Pharm. 1988, 321, 771–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagat, S.; Jain, M.; Pandey, M.K.; Saxena, P.A.; Jain, S.C. Synthesis of new bridgehead heterocycles: Pyrimido[3’,2’:3,4]-1,2,4-triazino[5,6-b]indoles. Heteroat. Chem. 2006, 17, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyarintseva, O.N.; Kurilo, G.N.; Anisimova, O.S.; Grinev, A.N. Reaction of 3-aminoindole-2-carboxylic acids with an acetylenedicarboxylate ester. Khim. Geterotsikl. 1977, 1, 82–84. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, M.; Guyot, M. Synthesis of 2-substituted indolopyridin-4-ones. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996, 37, 4931–4932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.M.G.; Castro, B.; Rangel, M.; Silva, A.M.S.; Brandão, P.; Felix, V.; Cavaleiro, J.A.S. Microwave-enhanced synthesis of novel pyridinone-fused porphyrins. Synlett 2009, 1009–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakazumi, H.; Endo, T.; Nakaue, T.; Kitao, T. Synthesis of 4,10-dihydro-4,10-dioxo-1H[1]benzothiopyrano[3,2-B]pyridine and 7-oxo-7,13-dihydro[1]benzothiopyrano[2,3-b]-1,5-benzodiazepine. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1985, 22, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, B.M.; Harrison, B.L. Certain Quinolines and Thienopyridines as Excitatory Amino Acid Antagonists. Patent US5026700A, 25 June 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Goerlitzer, K.; Kramer, C. Potential antiallergics. 3. Synthesis and transformations of 1, 4-dihydro-4-oxo-(1) benzothieno (3, 2-b) pyridine-2-carboxylic acid esters. Pharmazie 2000, 9, 645–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, J.M.; Huddleston, P.R.; Jones, A.W.; Edwards, M. Thienopyridines. Part 2. Application of the Conrad−Limpach and Gould−Jacobs reactions to the synthesis of thieno[3,4-b]pyridin4(1H)-ones. J. Chem. Res. S. 1980, 1, 4–5. [Google Scholar]

- Connor, D.T.; Young, P.A.; Strandtmann, M. Synthesis of 4,10-dihydro-4,10-dioxo-1H-[1]-benzopyrano[3,2-b]pyridine, 4,5-Dihydro-4,5-dioxo-1H-[1]-benzopyrano[2,3–6]pyridine and 1,5-Dihydro-1,5-dioxo-4H-[1]-benzopyrano[3,4-b]pyridine derivatives from aminobenzopyrones. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1981, 18, 697–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorokhov, V.A.; Vasilyev, A.V.; Baranin, S.V. Synthesis of 3-acetyl-4-amino-6-arylpyran-2-ones and ethyl 7-aryl-4,5(1H, 5H)-dioxopyrano[4,3-b]pyridine-2-carboxylates. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2002, 51, 503–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, D.T. 1,5-Dihydro-1,5-dioxo-N-1H-tetrazol-5-yl-4H-[1]benzopyrano[3,4-b]pyridine-3-Carboxamides and Process Thereof. Patent US4198511A, 15 April 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Goerlitzer, K.; Kramer, C. Potenzielle Antiallergika: Darstellung und Reaktionen von 1,4-Dihydro-4-oxo-[1]benzofuro[3, 2-b]pyridin-2-carbonsäureestern. Pharmazie 2000, 8, 587–594. [Google Scholar]

- Fehér, E.; Szatmári, I.; Dudás, T.; Zalatnai, A.; Farkas, T.; Lőrinczi, B.; Fülöp, F.; Vécsei, L.; Toldi, J. Structural evaluation and electrophysiological effects of some kynurenic acid analogs. Molecules 2019, 24, 3502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hall, M.C.; Johnson, G.H.; Wright, B.J. Quinoline derivatives as antiallergy agents. J. Med. Chem. 1974, 17, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryant, J.A.; Buckman, B.O.; Islam, I.; Mohan, R.; Morrissey, M.M.; Wei, G.P.; Wei, X.; Yuan, S. Platelet Adenosine Diphosphate Receptor Antagonists. Patent US2003060474A1, 27 March 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lőrinczi, B.; Csámpai, A.; Fülöp, F.; Szatmári, I. Synthetic-and DFT modelling studies on regioselective modified Mannich reactions of hydroxy-KYNA derivatives. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloan, N.L.; Luthra, S.K.; McRobbie, G.; Pimlott, S.L.; Sutherland, A. Late stage iodination of biologically active agents using a one-pot process from aryl amines. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 54881–54891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Szatmári, I.; Fülöp, F. Syntheses, transformations and applications of aminonaphthol derivatives prepared via modified Mannich reactions. Tetrahedron 2013, 69, 1255–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Szatmári, I.; Fülöp, F. Microwave-Assisted One-Pot Synthesis of (Aminoalkyl)naphthols and (Aminoalkyl)quinolinols by Using Ammonium Carbamate or Ammonium Hydrogen Carbonate as Solid Ammonia Source. Synthesis 2009, 5, 775–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szatmári, I.; Fülöp, F. Simple access to pentacyclic oxazinoisoquinolines via an unexpected transformation of aminomethylnaphthols. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011, 52, 4440–4442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sas, J.; Szatmári, I.; Fülöp, F. C-3 functionalization of indole derivatives with isoquinolines. Curr. Org. Chem. 2016, 20, 2038–2054. [Google Scholar]

- Lőrinczi, B.; Csámpai, A.; Fülöp, F.; Szatmári, I. Synthesis of new C-3 substituted kynurenic acid derivatives. Molecules 2020, 25, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Reaction | Reagent | Solvent | Temperature (°C) | Reaction Time | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| i | diethyl oxalacetate | glacial acetic acid | 40–50 °C; r.t. | 4 h; overnight | 2a 43% [26] |

| neat | 90 °C | 7 h | 2b 21% [27] | ||

| sodium (Z)-1,4-diethoxy-1,4-dioxobut-2-en-2-olate | glacial acetic acid | r.t. | 2.5 days | 2b 23% [28] | |

| ii | - | Ph2O | reflux | 10 + 10 min | 3a 84% [26] |

| Dowtherm A | 210 °C | 5 h | 3b 34% [27] | ||

| Ph2O | reflux | 15 + 20 min | 3b 29% [28] |

| Compound # | R2 | R3 | R4 | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 118 | H | 2-morpholinoethyl | H | 78 |

| 119 | H | 2-(dimethylamino)ethyl | Ph | 74 |

| 120 | Me | Me | H | 82 |

| 121 | Me | Bz | H | 85 |

| 122 | morpholine | H | 91 | |

| 123 | piperidine | H | 73 | |

| 124 | N-methyl-piperazine | H | 78 | |

| 125 | 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline | H | 81 | |

| 126 | 6,7-dimethoxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline | H | 72 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lőrinczi, B.; Szatmári, I. KYNA Derivatives with Modified Skeleton; Hydroxyquinolines with Potential Neuroprotective Effect. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11935. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222111935

Lőrinczi B, Szatmári I. KYNA Derivatives with Modified Skeleton; Hydroxyquinolines with Potential Neuroprotective Effect. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021; 22(21):11935. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222111935

Chicago/Turabian StyleLőrinczi, Bálint, and István Szatmári. 2021. "KYNA Derivatives with Modified Skeleton; Hydroxyquinolines with Potential Neuroprotective Effect" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22, no. 21: 11935. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222111935