Allosteric Interactions between Adenosine A2A and Dopamine D2 Receptors in Heteromeric Complexes: Biochemical and Pharmacological Characteristics, and Opportunities for PET Imaging

Abstract

1. Introduction

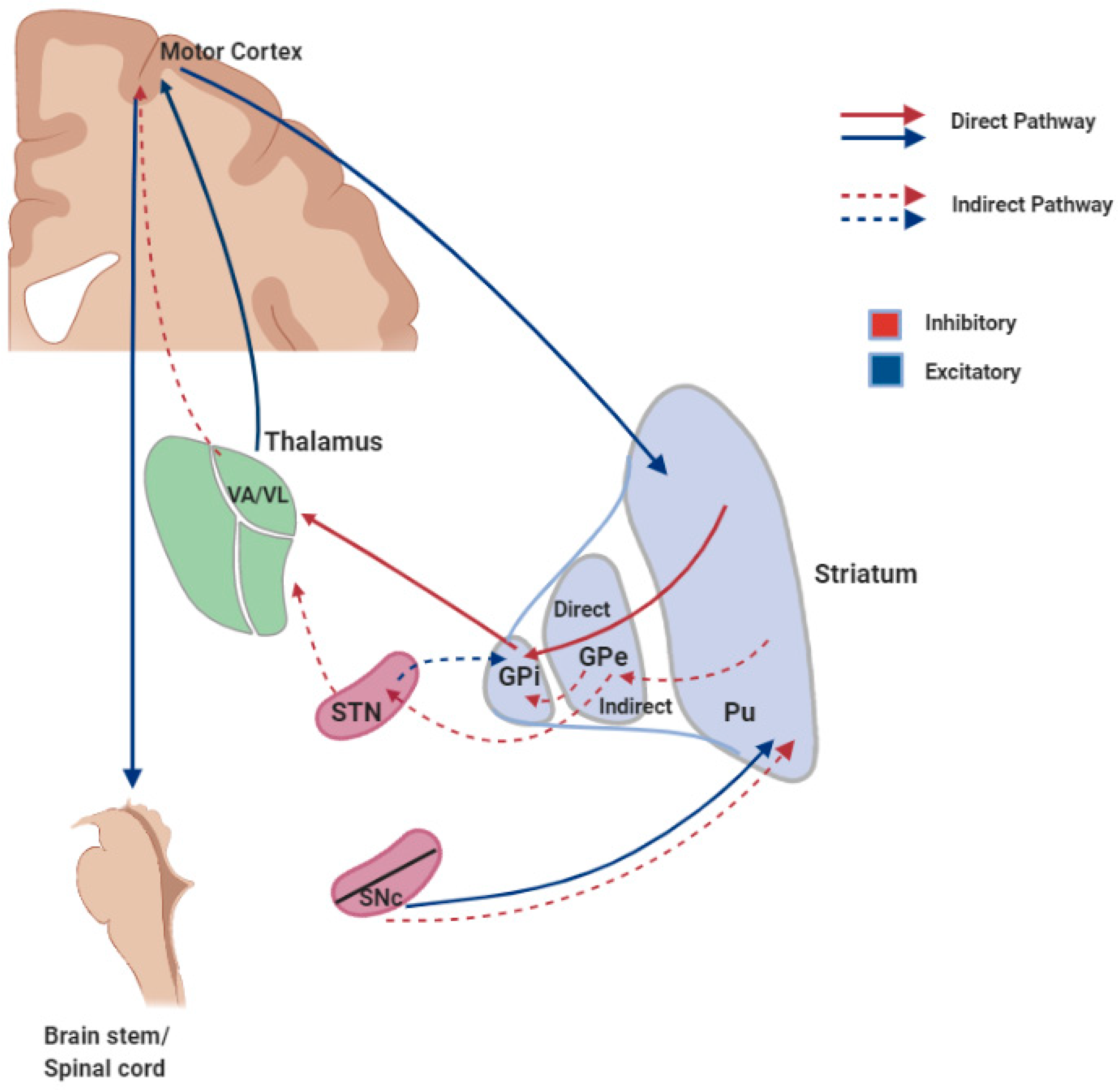

2. Antagonistic Interactions between Adenosine and Dopamine

2.1. Living Animals

2.2. Membrane Preparations

2.3. Intact Cells

2.4. Brain Slices

3. Regional, Cellular, and Subcellular Distribution of A2A and D2 Receptors

3.1. Regional Distribution

3.2. Cellular Distribution

3.3. Subcellular Location

4. A2AR and D2R Co-Aggregate, Co-Internalize and Co-Desensitize

5. A2AR and D2R Are at Very Close Distance in Biomembranes and Form Heteromers

6. Pharmacological Consequences of A2A/D2 Heteromer Formation

7. A2A/D2 Interactions and Parkinson’s Disease

8. A2AR-D2R Interactions and Schizophrenia

9. A2AR-D2R Interactions and Treatment of Drug Addiction

10. A2AR-D2R Interactions and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

11. PET Imaging of Adenosine–Dopamine Interactions

11.1. Pharmacological Challenge Studies

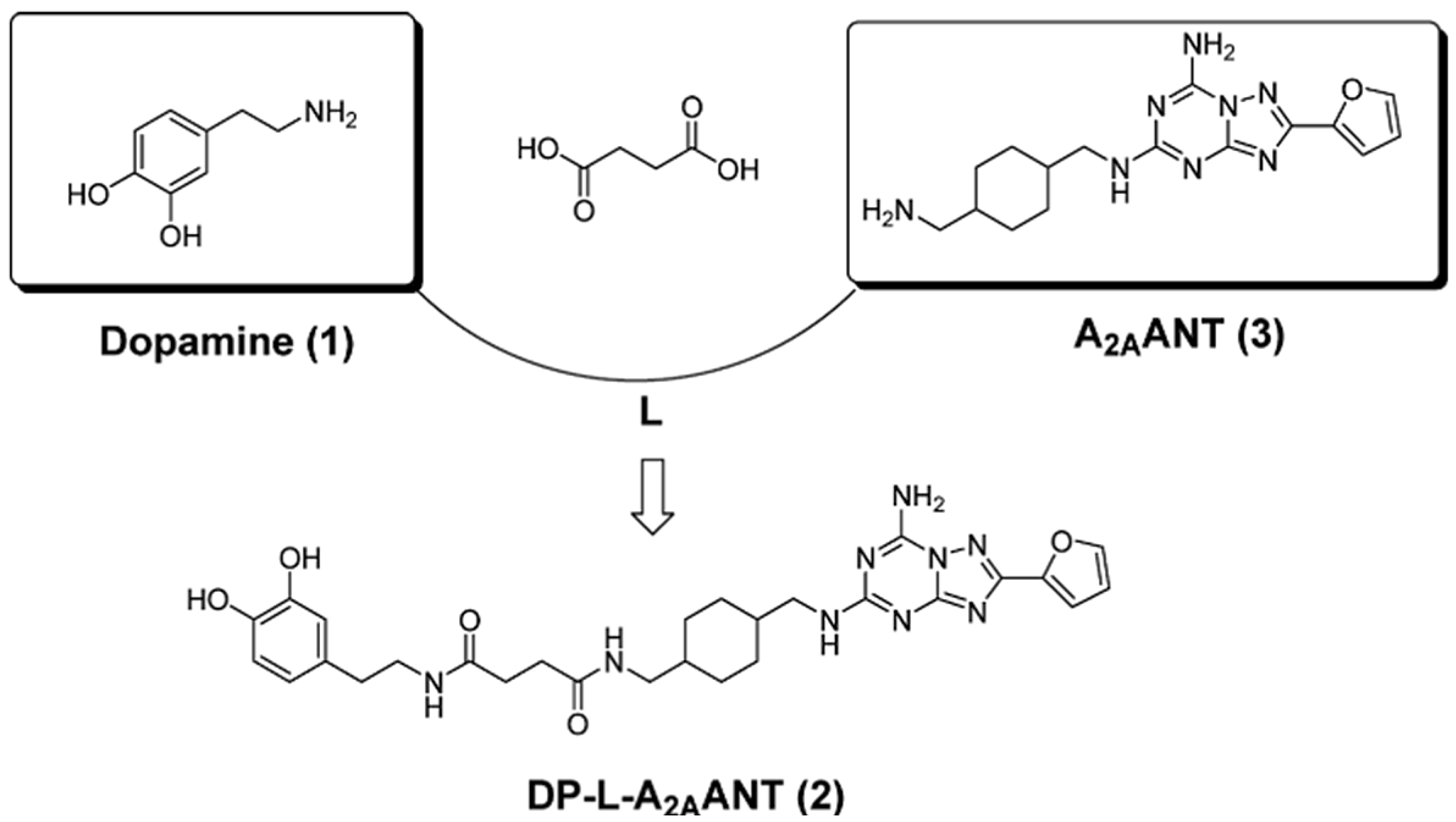

11.2. Studies with Bivalent Radioligands

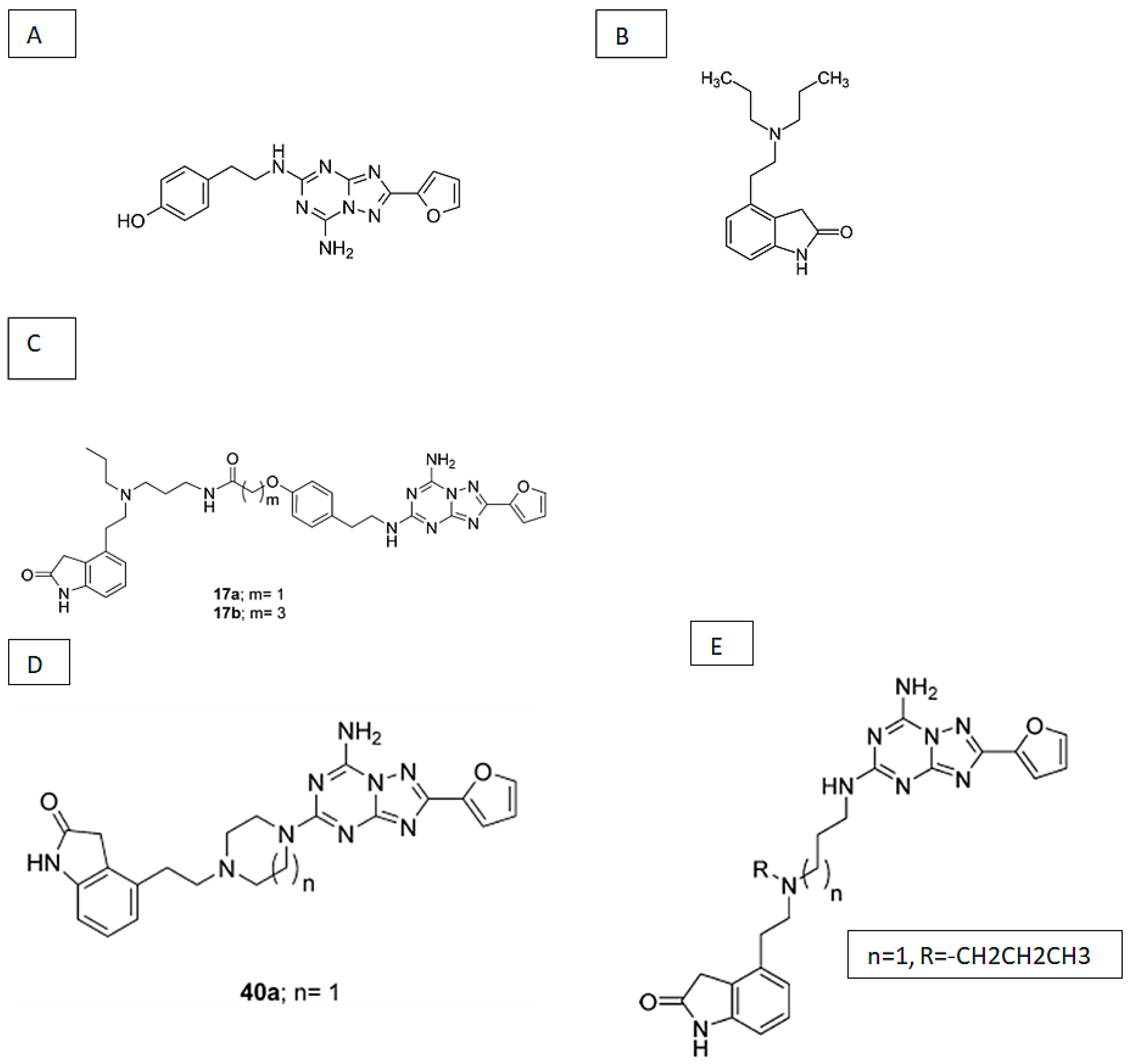

11.3. Studies with Radiolabeled Heteromer-Specific Allosteric Modulators

11.4. Other Opportunities for PET Imaging

12. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| A2AR | Adenosine A2A receptor |

| ADHD | Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder |

| AlphaScreen | Amplified luminescent proximity homogeneous assay screen (based on luminescent oxygen channeling immunoassay) |

| BBB | Blood–brain barrier |

| BHT-920 | 5,6,7,8-Tetrahydro-6-(2-propen-1-yl)-4H-thiazolo[4,5-d]azepin-2-amine dihydrochloride |

| BiFC | Bimolecular fluorescence complementation |

| BRET | Bioluminescence resonance energy transfer |

| CGS21680 | 2-[p-(2-carboxyethyl)phenethylamino]-5’- N-ethylcarboxamido-adenosine |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| CSC | 8-(3-Chlorostyryl)caffeine |

| D2R | Dopamine D2 receptor |

| DMFP | Desmethoxyfallypride |

| DMPX | 3,7-Dimethyl-1-propargylxanthine |

| FCP | Fluoroclebopride |

| FEBF | Fluorethyl-2,3-dihydrobenzofuran |

| FESP | Fluoroethyl-spiperone |

| FPE | Fluoropropyl-epidepride |

| FPSP | Fluoropropyl-spiperone |

| FRET | Fluorescence resonance energy transfer |

| MABN | 2,3-dimethoxy-N-[9-(4-fluorobenzyl)-9-azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonan-3beta-yl]benzamide |

| MBP | 2,3-dimethoxy-N-[1-(4-fluorobenzyl)piperidin4yl]benzamide |

| MNPA | Methoxy-N-n-propylnorapomorphine |

| MSN | Medium spiny neuron |

| MECA | 5′-(N-methyl)carboxamido-adenosine |

| NECA | 5’-(N-ethyl)carboxamido-adenosine |

| NMSP | N-methyl-spiperone |

| NPA | N-n-propylnorapomorphine |

| PANNS | Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale |

| PIA | N6-R-phenylisopropyladenosine |

| PPHT | (+/-)-2-(N-phenethyl-N-propyl)amino-5-hydroxytetralin |

| TMSX | [7-methyl-11C]-(E)-8-(3,4,5-trimethoxystyryl)-1,3,7-trimethylxanthine |

| XCC | 8-(p-carboxymethyloxy)phenyl-1,3 dipropylxanthine |

References

- Latini, S.; Corsi, C.; Pedata, F.; Pepeu, G. The Source of Brain Adenosine Outflow during Ischemia and Electrical Stimulation. Neurochem. Int. 1996, 28, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballarín, M.; Fredholm, B.B.; Ambrosio, S.; Mahy, N. Extracellular Levels of Adenosine and Its Metabolites in the Striatum of Awake Rats: Inhibition of Uptake and Metabolism. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1991, 142, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pazzagli, M.; Corsi, C.; Fratti, S.; Pedata, F.; Pepeu, G. Regulation of Extracellular Adenosine Levels in the Striatum of Aging Rats. Brain Res. 1995, 684, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo-Rodriguez, E.; Liu, M.; Blanco-Centurion, C.; Shiromani, P.J. Effects of Hypocretin (Orexin) Neuronal Loss on Sleep and Extracellular Adenosine Levels in the Rat Basal Forebrain. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 1191–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, A.M.; Battersby, A.S.; Baghdoyan, H.A.; Lydic, R. Opioid-Induced Decreases in Rat Brain Adenosine Levels Are Reversed by Inhibiting Adenosine Deaminase. Anesthesiology 2009, 111, 1327–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, R.; Engemann, S.C.; Sahota, P.; Thakkar, M.M. Effects of Ethanol on Extracellular Levels of Adenosine in the Basal Forebrain: An in Vivo Microdialysis Study in Freely Behaving Rats. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2010, 34, 813–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda, M.F.; Hamani, C.; De Almeida, A.C.; Amorim, B.O.; Macedo, C.E.; Fernandes, M.J.; Nobrega, J.N.; Aarão, M.C.; Madureira, A.P.; Rodrigues, A.M.; et al. Role of Adenosine in the Antiepileptic Effects of Deep Brain Stimulation. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collis, M.G.; Hourani, S.M. Adenosine Receptor Subtypes. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1993, 14, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredholm, B.B.; Abbracchio, M.P.; Burnstock, G.; Daly, J.W.; Harden, T.K.; Jacobson, K.A.; Leff, P.; Williams, M. Nomenclature and Classification of Purinoceptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 1994, 46, 143–156. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, T.M.; Stiles, G.L. Adenosine Receptors. Neuropharmacology 1995, 34, 683–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunwiddie, T.V.; Masino, S.A. The Role and Regulation of Adenosine in the Central Nervous System. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2001, 24, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredholm, B.B.; IJzerman, A.P.; Jacobson, K.A.; Klotz, K.N.; Linden, J. International Union of Pharmacology. XXV. Nomenclature and Classification of Adenosine Receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 2001, 53, 527–552. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fredholm, B.B.; IJzerman, A.P.; Jacobson, K.A.; Linden, J.; Müller, C.E. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXXI. Nomenclature and Classification of Adenosine Receptors--an Update. Pharmacol. Rev. 2011, 63, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuxe, K.; Ungerstedt, U. Action of Caffeine and Theophyllamine on Supersensitive Dopamine Receptors: Considerable Enhancement of Receptor Response to Treatment with DOPA and Dopamine Receptor Agonists. Med. Biol. 1974, 52, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ferré, S.; Herrera-Marschitz, M.; Grabowska-Andén, M.; Ungerstedt, U.; Casas, M.; Andén, N.E. Postsynaptic Dopamine/Adenosine Interaction: I. Adenosine Analogues Inhibit Dopamine D2-Mediated Behaviour in Short-Term Reserpinized Mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1991, 192, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferré, S.; Herrera-Marschitz, M.; Grabowska-Andén, M.; Casas, M.; Ungerstedt, U.; Andén, N.E. Postsynaptic Dopamine/Adenosine Interaction: II. Postsynaptic Dopamine Agonism and Adenosine Antagonism of Methylxanthines in Short-Term Reserpinized Mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1991, 192, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferré, S.; Rubio, A.; Fuxe, K. Stimulation of Adenosine A2 Receptors Induces Catalepsy. Neurosci. Lett. 1991, 130, 162–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevitt, J.; Vallance, C.; Harris, A.; Goode, T. Adenosine Antagonists Reverse the Cataleptic Effects of Haloperidol: Implications for the Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2009, 92, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Yacoubi, M.; Ledent, C.; Parmentier, M.; Costentin, J.; Vaugeois, J.M. Adenosine A2A Receptor Knockout Mice Are Partially Protected Against Drug-Induced Catalepsy. Neuroreport 2001, 12, 983–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varty, G.B.; Hodgson, R.A.; Pond, A.J.; Grzelak, M.E.; Parker, E.M.; Hunter, J.C. The Effects of Adenosine A2A Receptor Antagonists on Haloperidol-Induced Movement Disorders in Primates. Psychopharmacology 2008, 200, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, S.P.; Reddington, M. The Cellular Localization of Adenosine Receptors in Rat Neostriatum. Neuroscience 1989, 28, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebola, N.; Canas, P.M.; Oliveira, C.R.; Cunha, R.A. Different Synaptic and Subsynaptic Localization of Adenosine A2A Receptors in the Hippocampus and Striatum of the Rat. Neuroscience 2005, 132, 893–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettinger, B.D.; Lee, A.; Linden, J.; Rosin, D.L. Ultrastructural Localization of Adenosine A2A Receptors Suggests Multiple Cellular Sites for Modulation of GABAergic Neurons in Rat Striatum. J. Comp. Neurol. 2001, 431, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosin, D.L.; Hettinger, B.D.; Lee, A.; Linden, J. Anatomy of Adenosine A2A Receptors in Brain: Morphological Substrates for Integration of Striatal Function. Neurology 2003, 61, S12–S18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Font, L.; Mingote, S.; Farrar, A.M.; Pereira, M.; Worden, L.; Stopper, C.; Port, R.G.; Salamone, J.D. Intra-Accumbens Injections of the Adenosine A2A Agonist CGS 21680 Affect Effort-Related Choice Behavior in Rats. Psychopharmacology 2008, 199, 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worden, L.T.; Shahriari, M.; Farrar, A.M.; Sink, K.S.; Hockemeyer, J.; Müller, C.E.; Salamone, J.D. The Adenosine A2A Antagonist MSX-3 Reverses the Effort-Related Effects of Dopamine Blockade: Differential Interaction With D1 and D2 Family Antagonists. Psychopharmacology 2009, 203, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salamone, J.D.; Farrar, A.M.; Font, L.; Patel, V.; Schlar, D.E.; Nunes, E.J.; Collins, L.E.; Sager, T.N. Differential Actions of Adenosine A1 and A2A Antagonists on the Effort-Related Effects of Dopamine D2 Antagonism. Behav. Brain Res. 2009, 201, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferré, S.; von Euler, G.; Johansson, B.; Fredholm, B.B.; Fuxe, K. Stimulation of High-Affinity Adenosine A2 Receptors Decreases the Affinity of Dopamine D2 Receptors in Rat Striatal Membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1991, 88, 7238–7241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferré, S.; Fuxe, K. Dopamine Denervation Leads to an Increase in the Intramembrane Interaction between Adenosine A2 and Dopamine D2 Receptors in the Neostriatum. Brain Res. 1992, 594, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferré, S.; Snaprud, P.; Fuxe, K. Opposing Actions of an Adenosine A2 Receptor Agonist and a GTP Analogue on the Regulation of Dopamine D2 Receptors in Rat Neostriatal Membranes. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1993, 244, 311–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnati, L.F.; Fuxe, K.; Benfenati, F.; von Euler, G.; Fredholm, B. Intramembrane Receptor-Receptor Interactions: Integration of Signal Transduction Pathways in the Nervous System. Neurochem. Int. 1993, 22, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuxe, K.; Ferré, S.; Zoli, M.; Agnati, L.F. Integrated Events in Central Dopamine Transmission As Analyzed at Multiple Levels. Evidence for Intramembrane Adenosine A2A/Dopamine D2 and Adenosine A1/Dopamine D1 Receptor Interactions in the Basal Ganglia. Brain Res. Rev 1998, 26, 258–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.N.; Dasgupta, S.; Lledo, P.M.; Vincent, J.D.; Fuxe, K. Reduction of Dopamine D2 Receptor Transduction by Activation of Adenosine A2a Receptors in Stably A2a/D2 (Long-Form) Receptor Co-Transfected Mouse Fibroblast Cell Lines: Studies on Intracellular Calcium Levels. Neuroscience 1995, 68, 729–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, H.; Ferré, S.; Dalal, A.; Peterfreund, R.A.; Fuxe, K.; Vincent, J.D.; Lledo, P.M. Activation of Adenosine A1 and A2A Receptors Modulates Dopamine D2 Receptor-Induced Responses in Stably Transfected Human Neuroblastoma Cells. J. Neurochem. 2000, 74, 432–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dasgupta, S.; Ferré, S.; Kull, B.; Hedlund, P.B.; Finnman, U.B.; Ahlberg, S.; Arenas, E.; Fredholm, B.B.; Fuxe, K. Adenosine A2A Receptors Modulate the Binding Characteristics of Dopamine D2 Receptors in Stably Cotransfected Fibroblast Cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1996, 316, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kull, B.; Ferré, S.; Arslan, G.; Svenningsson, P.; Fuxe, K.; Owman, C.; Fredholm, B.B. Reciprocal Interactions Between Adenosine A2A and Dopamine D2 Receptors in Chinese Hamster Ovary Cells Co-Transfected With the Two Receptors. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1999, 58, 1035–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torvinen, M.; Kozell, L.B.; Neve, K.A.; Agnati, L.F.; Fuxe, K. Biochemical Identification of the Dopamine D2 Receptor Domains Interacting With the Adenosine A2A Receptor. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2004, 24, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Dueñas, V.; Gómez-Soler, M.; Jacobson, K.A.; Kumar, S.T.; Fuxe, K.; Borroto-Escuela, D.O.; Ciruela, F. Molecular Determinants of A2AR-D2R Allosterism: Role of the Intracellular Loop 3 of the D2R. J. Neurochem. 2012, 123, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Dueñas, V.; Gómez-Soler, M.; Morató, X.; Núñez, F.; Das, A.; Kumar, T.S.; Jaumà, S.; Jacobson, K.A.; Ciruela, F. Dopamine D(2) Receptor-Mediated Modulation of Adenosine A(2A) Receptor Agonist Binding Within the A(2A)R/D(2)R Oligomer Framework. Neurochem. Int. 2013, 63, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Trincavelli, M.L.; Cuboni, S.; Catena, D.M.; Maggio, R.; Klotz, K.N.; Novi, F.; Panighini, A.; Daniele, S.; Martini, C. Receptor Crosstalk: Haloperidol Treatment Enhances A(2A) Adenosine Receptor Functioning in a Transfected Cell Model. Purinergic Signal. 2010, 6, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaventura, J.; Navarro, G.; Casadó-Anguera, V.; Azdad, K.; Rea, W.; Moreno, E.; Brugarolas, M.; Mallol, J.; Canela, E.I.; Lluís, C.; et al. Allosteric Interactions Between Agonists and Antagonists Within the Adenosine A2A Receptor-Dopamine D2 Receptor Heterotetramer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, E3609–E3618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Cabiale, Z.; Hurd, Y.; Guidolin, D.; Finnman, U.B.; Zoli, M.; Agnati, L.F.; Vanderhaeghen, J.J.; Fuxe, K.; Ferré, S. Adenosine A2A Agonist CGS 21680 Decreases the Affinity of Dopamine D2 Receptors for Dopamine in Human Striatum. Neuroreport 2001, 12, 1831–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffmann, S.N.; Libert, F.; Vassart, G.; Vanderhaeghen, J.J. Distribution of Adenosine A2 Receptor MRNA in the Human Brain. Neurosci. Lett. 1991, 130, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, J.S.; Weaver, D.R.; Rivkees, S.A.; Peterfreund, R.A.; Pollack, A.E.; Adler, E.M.; Reppert, S.M. Molecular Cloning of the Rat A2 Adenosine Receptor: Selective Co-Expression With D2 Dopamine Receptors in Rat Striatum. Mol. Brain Res. 1992, 14, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterfreund, R.A.; MacCollin, M.; Gusella, J.; Fink, J.S. Characterization and Expression of the Human A2a Adenosine Receptor Gene. J. Neurochem. 1996, 66, 362–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, A.K.; Gubitz, A.K.; Sirinathsinghji, D.J.; Richardson, P.J.; Freeman, T.C. Tissue Distribution of Adenosine Receptor MRNAs in the Rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996, 118, 1461–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svenningsson, P.; Le, M.C.; Aubert, I.; Burbaud, P.; Fredholm, B.B.; Bloch, B. Cellular Distribution of Adenosine A2A Receptor MRNA in the Primate Striatum. J. Comp. Neurol. 1998, 399, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaelin-Lang, A.; Liniger, P.; Probst, A.; Lauterburg, T.; Burgunder, J.M. Adenosine A2A Receptor Gene Expression in the Normal Striatum and After 6-OH-Dopamine Lesion. J. Neural. Transm. 2000, 107, 851–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Mir, M.I.; Probst, A.; Palacios, J.M. Adenosine A2 Receptors: Selective Localization in the Human Basal Ganglia and Alterations with Disease. Neuroscience 1991, 42, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, H.; Mori, A.; Ichimura, M.; Shindou, T.; Yanagawa, K.; Shimada, J.; Kase, H. Binding of [3H]KF17837S, a Selective Adenosine A2 Receptor Antagonist, to Rat Brain Membranes. Mol. Pharmacol. 1994, 46, 817–822. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fredholm, B.B.; Lindström, K.; Dionisotti, S.; Ongini, E. [3H]SCH 58261, a Selective Adenosine A2A Receptor Antagonist, Is a Useful Ligand in Autoradiographic Studies. J. Neurochem. 1998, 70, 1210–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosin, D.L.; Robeva, A.; Woodard, R.L.; Guyenet, P.G.; Linden, J. Immunohistochemical Localization of Adenosine A2A Receptors in the Rat Central Nervous System. J. Comp. Neurol. 1998, 401, 163–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kull, B.; Svenningsson, P.; Hall, H.; Fredholm, B.B. GTP Differentially Affects Antagonist Radioligand Binding to Adenosine A(1) and A(2A) Receptors in Human Brain. Neuropharmacology 2000, 39, 2374–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, S.P.; Millns, P.J. [(3)H]ZM241385--an Antagonist Radioligand for Adenosine A(2A) Receptors in Rat Brain. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2001, 411, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMet, E.M.; Chicz-DeMet, A. Localization of Adenosine A2A-Receptors in Rat Brain With [3H]ZM-241385. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2002, 366, 478–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calon, F.; Dridi, M.; Hornykiewicz, O.; Bédard, P.J.; Rajput, A.H.; Di, P.T. Increased Adenosine A2A Receptors in the Brain of Parkinson’s Disease Patients With Dyskinesias. Brain 2004, 127, 1075–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogenpohl, J.W.; Ritter, S.L.; Hall, R.A.; Smith, Y. Adenosine A2A Receptor in the Monkey Basal Ganglia: Ultrastructural Localization and Colocalization with the Metabotropic Glutamate Receptor 5 in the Striatum. J. Comp. Neurol. 2012, 520, 570–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyson, S.J.; McGonigle, P.; Molinoff, P.B. Quantitative Autoradiographic Localization of the D1 and D2 Subtypes of Dopamine Receptors in Rat Brain. J. Neurosci. 1986, 6, 3177–3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Keyser, J.; Claeys, A.; De Backer, J.P.; Ebinger, G.; Roels, F.; Vauquelin, G. Autoradiographic Localization of D1 and D2 Dopamine Receptors in the Human Brain. Neurosci. Lett. 1988, 91, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meador-Woodruff, J.H.; Mansour, A.; Bunzow, J.R.; Van Tol, H.H.; Watson, S.J., Jr.; Civelli, O. Distribution of D2 Dopamine Receptor MRNA in Rat Brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1989, 86, 7625–7628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camps, M.; Cortés, R.; Gueye, B.; Probst, A.; Palacios, J.M. Dopamine Receptors in Human Brain: Autoradiographic Distribution of D2 Sites. Neuroscience 1989, 28, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landwehrmeyer, B.; Mengod, G.; Palacios, J.M. Differential Visualization of Dopamine D2 and D3 Receptor Sites in Rat Brain. A Comparative Study Using in Situ Hybridization Histochemistry and Ligand Binding Autoradiography. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1993, 5, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Moine, C.; Normand, E.; Guitteny, A.F.; Fouque, B.; Teoule, R.; Bloch, B. Dopamine Receptor Gene Expression by Enkephalin Neurons in Rat Forebrain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1990, 87, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, J.M.; Powell, T.P. The Structure of the Caudate Nucleus of the Cat: Light and Electron Microscopy. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1971, 262, 383–401. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, G.E.; Crutcher, M.D. Functional Architecture of Basal Ganglia Circuits: Neural Substrates of Parallel Processing. Trends Neurosci. 1990, 13, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerfen, C.R. The Neostriatal Mosaic: Multiple Levels of Compartmental Organization. Trends Neurosci. 1992, 15, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawaguchi, Y.; Wilson, C.J.; Emson, P.C. Projection Subtypes of Rat Neostriatal Matrix Cells Revealed by Intracellular Injection of Biocytin. J. Neurosci. 1990, 10, 3421–3438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerfen, C.R.; Engber, T.M.; Mahan, L.C.; Susel, Z.; Chase, T.N.; Monsma, F.J., Jr.; Sibley, D.R. D1 and D2 Dopamine Receptor-Regulated Gene Expression of Striatonigral and Striatopallidal Neurons. Science 1990, 250, 1429–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerfen, C.R.; Surmeier, D.J. Modulation of Striatal Projection Systems by Dopamine. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2011, 34, 441–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiffmann, S.N.; Libert, F.; Vassart, G.; Dumont, J.E.; Vanderhaeghen, J.J. A Cloned G Protein-Coupled Protein With a Distribution Restricted to Striatal Medium-Sized Neurons. Possible Relationship with D1 Dopamine Receptor. Brain Res. 1990, 519, 333–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, D.M.; Levey, A.I.; Brann, M.R. Expression of Muscarinic Acetylcholine and Dopamine Receptor MRNAs in Rat Basal Ganglia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1990, 87, 7050–7054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiffmann, S.N.; Jacobs, O.; Vanderhaeghen, J.J. Striatal Restricted Adenosine A2 Receptor (RDC8) Is Expressed by Enkephalin but Not by Substance P Neurons: An in Situ Hybridization Histochemistry Study. J. Neurochem. 1991, 57, 1062–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Augood, S.J.; Emson, P.C. Adenosine A2a Receptor MRNA Is Expressed by Enkephalin Cells but Not by Somatostatin Cells in Rat Striatum: A Co-Expression Study. Mol. Brain Res. 1994, 22, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svenningsson, P.; Le, M.C.; Kull, B.; Sunahara, R.; Bloch, B.; Fredholm, B.B. Cellular Expression of Adenosine A2A Receptor Messenger RNA in the Rat Central Nervous System With Special Reference to Dopamine Innervated Areas. Neuroscience 1997, 80, 1171–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferré, S.; Fuxe, K.; von Euler, G.; Johansson, B.; Fredholm, B.B. Adenosine-Dopamine Interactions in the Brain. Neuroscience 1992, 51, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferré, S.; O’Connor, W.T.; Fuxe, K.; Ungerstedt, U. The Striopallidal Neuron: A Main Locus for Adenosine-Dopamine Interactions in the Brain. J. Neurosci. 1993, 13, 5402–5406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, I.; Asanuma, M.; Diaz-Corrales, F.J.; Miyoshi, K.; Ogawa, N. Direct Evidence for Expression of Dopamine Receptors in Astrocytes from Basal Ganglia. Brain Res. 2004, 1029, 120–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daré, E.; Schulte, G.; Karovic, O.; Hammarberg, C.; Fredholm, B.B. Modulation of Glial Cell Functions by Adenosine Receptors. Physiol. Behav. 2007, 92, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, M.; Augusto, E.; Santos-Rodrigues, A.D.; Schwarzschild, M.A.; Chen, J.F.; Cunha, R.A.; Agostinho, P. Adenosine A2A Receptors Modulate Glutamate Uptake in Cultured Astrocytes and Gliosomes. Glia 2012, 60, 702–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, M.; Augusto, E.; Agostinho, P.; Cunha, R.A.; Chen, J.F. Antagonistic Interaction Between Adenosine A2A Receptors and Na+/K+-ATPase-A2 Controlling Glutamate Uptake in Astrocytes. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 18492–18502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervetto, C.; Venturini, A.; Passalacqua, M.; Guidolin, D.; Genedani, S.; Fuxe, K.; Borroto-Esquela, D.O.; Cortelli, P.; Woods, A.; Maura, G.; et al. A2A-D2 Receptor-Receptor Interaction Modulates Gliotransmitter Release From Striatal Astrocyte Processes. J. Neurochem. 2017, 140, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tozzi, A.; de Iure, A.; Di Filippo, M.; Tantucci, M.; Costa, C.; Borsini, F.; Ghiglieri, V.; Giampà, C.; Fusco, F.R.; Picconi, B.; et al. The Distinct Role of Medium Spiny Neurons and Cholinergic Interneurons in the D2/A2A Receptor Interaction in the Striatum: Implications for Parkinson’s Disease. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 1850–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levey, A.I.; Hersch, S.M.; Rye, D.B.; Sunahara, R.K.; Niznik, H.B.; Kitt, C.A.; Price, D.L.; Maggio, R.; Brann, M.R.; Ciliax, B.J. Localization of D1 and D2 Dopamine Receptors in Brain With Subtype-Specific Antibodies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 8861–8865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillion, J.; Canals, M.; Torvinen, M.; Casado, V.; Scott, R.; Terasmaa, A.; Hansson, A.; Watson, S.; Olah, M.E.; Mallol, J.; et al. Coaggregation, Cointernalization, and Codesensitization of Adenosine A2A Receptors and Dopamine D2 Receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 18091–18097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agnati, L.F.; Fuxe, K.; Torvinen, M.; Genedani, S.; Franco, R.; Watson, S.; Nussdorfer, G.G.; Leo, G.; Guidolin, D. New Methods to Evaluate Colocalization of Fluorophores in Immunocytochemical Preparations As Exemplified by a Study on A2A and D2 Receptors in Chinese Hamster Ovary Cells. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2005, 53, 941–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torvinen, M.; Torri, C.; Tombesi, A.; Marcellino, D.; Watson, S.; Lluis, C.; Franco, R.; Fuxe, K.; Agnati, L.F. Trafficking of Adenosine A2A and Dopamine D2 Receptors. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2005, 25, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genedani, S.; Guidolin, D.; Leo, G.; Filaferro, M.; Torvinen, M.; Woods, A.S.; Fuxe, K.; Ferré, S.; Agnati, L.F. Computer-Assisted Image Analysis of Caveolin-1 Involvement in the Internalization Process of Adenosine A2A-Dopamine D2 Receptor Heterodimers. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2005, 26, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borroto-Escuela, D.O.; Romero-Fernandez, W.; Tarakanov, A.O.; Ciruela, F.; Agnati, L.F.; Fuxe, K. On the Existence of a Possible A2A-D2-ß-Arrestin2 Complex: A2A Agonist Modulation of D2 Agonist-Induced ß-Arrestin2 Recruitment. J. Mol. Biol. 2011, 406, 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Wu, D.D.; Zhang, L.; Feng, L.Y. Modulation of A2a Receptor Antagonist on D2 Receptor Internalization and ERK Phosphorylation. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2013, 34, 1292–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trincavelli, M.L.; Daniele, S.; Orlandini, E.; Navarro, G.; Casadó, V.; Giacomelli, C.; Nencetti, S.; Nuti, E.; Macchia, M.; Huebner, H.; et al. A New D2 Dopamine Receptor Agonist Allosterically Modulates A(2A) Adenosine Receptor Signalling by Interacting With the A(2A)/D2 Receptor Heteromer. Cell Signal. 2012, 24, 951–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro, G.; Carriba, P.; Gandía, J.; Ciruela, F.; Casadó, V.; Cortés, A.; Mallol, J.; Canela, E.I.; Lluis, C.; Franco, R. Detection of Heteromers Formed by Cannabinoid CB1, Dopamine D2, and Adenosine A2A G-Protein-Coupled Receptors by Combining Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation and Bioluminescence Energy Transfer. Sci. World J. 2008, 8, 1088–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnati, L.F.; Guidolin, D.; Leo, G.; Carone, C.; Genedani, S.; Fuxe, K. Receptor-Receptor Interactions: A Novel Concept in Brain Integration. Prog. Neurobiol. 2010, 90, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavic, M.; Lluís, C.; Moreno, E.; Bakesová¡, J.; Canela, E.I.; Navarro, G. Production of Functional Recombinant G-Protein Coupled Receptors for Heteromerization Studies. J. Neurosci. Methods 2011, 199, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trifilieff, P.; Rives, M.L.; Urizar, E.; Piskorowski, R.A.; Vishwasrao, H.D.; Castrillon, J.; Schmauss, C.; Slättman, M.; Gullberg, M.; Javitch, J.A. Detection of Antigen Interactions Ex Vivo by Proximity Ligation Assay: Endogenous Dopamine D2-Adenosine A2A Receptor Complexes in the Striatum. Biotechniques 2011, 51, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Dueñas, V.; Llorente, J.; Gandía, J.; Borroto-Escuela, D.O.; Agnati, L.F.; Tasca, C.I.; Fuxe, K.; Ciruela, F. Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer-Based Technologies in the Study of Protein-Protein Interactions at the Cell Surface. Methods 2012, 57, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borroto-Escuela, D.O.; Romero-Fernandez, W.; Garriga, P.; Ciruela, F.; Narvaez, M.; Tarakanov, A.O.; Palkovits, M.; Agnati, L.F.; Fuxe, K. G Protein-Coupled Receptor Heterodimerization in the Brain. Methods Enzymol. 2013, 521, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Dueñas, V.; Gómez-Soler, M.; Valle-León, M.; Watanabe, M.; Ferrer, I.; Ciruela, F. Revealing Adenosine A(2A)-Dopamine D(2) Receptor Heteromers in Parkinson’s Disease Post-Mortem Brain Through a New AlphaScreen-Based Assay. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Cano, M.; Fernández-Dueñas, V.; Ciruela, F. Proximity Ligation Assay Image Analysis Protocol: Addressing Receptor-Receptor Interactions. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019, 2040, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Söderberg, O.; Gullberg, M.; Jarvius, M.; Ridderstråle, K.; Leuchowius, K.J.; Jarvius, J.; Wester, K.; Hydbring, P.; Bahram, F.; Larsson, L.G.; et al. Direct Observation of Individual Endogenous Protein Complexes in Situ by Proximity Ligation. Nat. Methods 2006, 3, 995–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandia, J.; Galino, J.; Amaral, O.B.; Soriano, A.; Lluís, C.; Franco, R.; Ciruela, F. Detection of Higher-Order G Protein-Coupled Receptor Oligomers by a Combined BRET-BiFC Technique. FEBS Lett. 2008, 582, 2979–2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiya, T.; Saitoh, O.; Yoshioka, K.; Nakata, H. Oligomerization of Adenosine A2A and Dopamine D2 Receptors in Living Cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003, 306, 544–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canals, M.; Marcellino, D.; Fanelli, F.; Ciruela, F.; de Benedetti, P.; Goldberg, S.R.; Neve, K.; Fuxe, K.; Agnati, L.F.; Woods, A.S.; et al. Adenosine A2A-Dopamine D2 Receptor-Receptor Heteromerization: Qualitative and Quantitative Assessment by Fluorescence and Bioluminescence Energy Transfer. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 46741–46749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prakash, A.; Luthra, P.M. Insilico Study of the A(2A)R-D(2)R Kinetics and Interfacial Contact Surface for Heteromerization. Amino Acids 2012, 43, 1451–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borroto-Escuela, D.O.; Rodriguez, D.; Romero-Fernandez, W.; Kapla, J.; Jaiteh, M.; Ranganathan, A.; Lazarova, T.; Fuxe, K.; Carlsson, J. Mapping the Interface of a GPCR Dimer: A Structural Model of the A(2A) Adenosine and D(2) Dopamine Receptor Heteromer. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarakanov, A.O.; Fuxe, K.G. Triplet Puzzle: Homologies of Receptor Heteromers. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2010, 41, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciruela, F.; Burgueño, J.; Casadó, V.; Canals, M.; Marcellino, D.; Goldberg, S.R.; Bader, M.; Fuxe, K.; Agnati, L.F.; Lluis, C.; et al. Combining Mass Spectrometry and Pull-Down Techniques for the Study of Receptor Heteromerization. Direct Epitope-Epitope Electrostatic Interactions Between Adenosine A2A and Dopamine D2 Receptors. Anal. Chem. 2004, 76, 5354–5363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woods, A.S.; Ferré, S. Amazing Stability of the Arginine-Phosphate Electrostatic Interaction. J. Proteome Res. 2005, 4, 1397–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borroto-Escuela, D.O.; Marcellino, D.; Narvaez, M.; Flajolet, M.; Heintz, N.; Agnati, L.; Ciruela, F.; Fuxe, K. A Serine Point Mutation in the Adenosine A2AR C-Terminal Tail Reduces Receptor Heteromerization and Allosteric Modulation of the Dopamine D2R. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 394, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borroto-Escuela, D.O.; Romero-Fernandez, W.; Tarakanov, A.O.; Gómez-Soler, M.; Corrales, F.; Marcellino, D.; Narvaez, M.; Frankowska, M.; Flajolet, M.; Heintz, N.; et al. Characterization of the A2AR-D2R Interface: Focus on the Role of the C-Terminal Tail and the Transmembrane Helices. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 402, 801–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro, G.; Aymerich, M.S.; Marcellino, D.; Cortés, A.; Casadó, V.; Mallol, J.; Canela, E.I.; Agnati, L.; Woods, A.S.; Fuxe, K.; et al. Interactions Between Calmodulin, Adenosine A2A, and Dopamine D2 Receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 28058–28068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamiya, T.; Saitoh, O.; Nakata, H. Functional Expression of Single-Chain Heterodimeric G-Protein-Coupled Receptors for Adenosine and Dopamine. Cell Struct. Funct. 2005, 29, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidi, P.A.; Chemel, B.R.; Hu, C.D.; Watts, V.J. Ligand-Dependent Oligomerization of Dopamine D(2) and Adenosine A(2A) Receptors in Living Neuronal Cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 2008, 74, 544–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.Y.; Lai, H.L.; Chen, H.M.; Siew, J.J.; Hsiao, C.T.; Chang, H.C.; Liao, K.S.; Tsai, S.C.; Wu, C.Y.; Kitajima, K.; et al. Functional Roles of ST8SIA3-Mediated Sialylation of Striatal Dopamine D(2) and Adenosine A(2A) Receptors. Transl. Psychiatry 2019, 9, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelassa, S.; Guidolin, D.; Venturini, A.; Averna, M.; Frumento, G.; Campanini, L.; Bernardi, R.; Cortelli, P.; Buonaura, G.C.; Maura, G.; et al. A2A-D2 Heteromers on Striatal Astrocytes: Biochemical and Biophysical Evidence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Dueñas, V.; Taura, J.J.; Cottet, M.; Gómez-Soler, M.; López-Cano, M.; Ledent, C.; Watanabe, M.; Trinquet, E.; Pin, J.P.; Luján, R.; et al. Untangling Dopamine-Adenosine Receptor-Receptor Assembly in Experimental Parkinsonism in Rats. Dis. Models Mech. 2015, 8, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, M.; Pu, Z.; Zhang, F.; Chen, L.; Ruan, Y.; Pan, X.; He, C.; Chen, X.; et al. Habit Formation After Random Interval Training Is Associated With Increased Adenosine A(2A) Receptor and Dopamine D(2) Receptor Heterodimers in the Striatum. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2016, 9, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borroto-Escuela, D.O.; Narváez, M.; Wydra, K.; Pintsuk, J.; Pinton, L.; Jimenez-Beristain, A.; Di Palma, M.; Jastrzebska, J.; Filip, M.; Fuxe, K. Cocaine Self-Administration Specifically Increases A2AR-D2R and D2R-Sigma1R Heteroreceptor Complexes in the Rat Nucleus Accumbens Shell. Relevance for Cocaine Use Disorder. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2017, 155, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonaventura, J.; Rico, A.J.; Moreno, E.; Sierra, S.; Sánchez, M.; Luquin, N.; Farré, D.; Müller, C.E.; Martínez-Pinilla, E.; Cortés, A.; et al. L-DOPA-Treatment in Primates Disrupts the Expression of A(2A) Adenosine-CB(1) Cannabinoid-D(2) Dopamine Receptor Heteromers in the Caudate Nucleus. Neuropharmacology 2014, 79, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Mészáros, J.; Walle, R.; Fan, R.; Sun, Z.; Dwork, A.J.; Trifilieff, P.; Javitch, J.A. Detecting G Protein-Coupled Receptor Complexes in Postmortem Human Brain With Proximity Ligation Assay and a Bayesian Classifier. Biotechniques 2020, 68, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferré, S.; Baler, R.; Bouvier, M.; Caron, M.G.; Devi, L.A.; Durroux, T.; Fuxe, K.; George, S.R.; Javitch, J.A.; Lohse, M.J.; et al. Building a New Conceptual Framework for Receptor Heteromers. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009, 5, 131–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferré, S.; Casadó, V.; Devi, L.A.; Filizola, M.; Jockers, R.; Lohse, M.J.; Milligan, G.; Pin, J.P.; Guitart, X. G Protein-Coupled Receptor Oligomerization Revisited: Functional and Pharmacological Perspectives. Pharmacol. Rev. 2014, 66, 413–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferré, S. The GPCR Heterotetramer: Challenging Classical Pharmacology. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2015, 36, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casadó-Anguera, V.; Bonaventura, J.; Moreno, E.; Navarro, G.; Cortés, A.; Ferré, S.; Casadó, V. Evidence for the Heterotetrameric Structure of the Adenosine A2A-Dopamine D2 Receptor Complex. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2016, 44, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro, G.; Cordomí, A.; Brugarolas, M.; Moreno, E.; Aguinaga, D.; Pérez-Benito, L.; Ferre, S.; Cortés, A.; Casadó, V.; Mallol, J.; et al. Cross-Communication Between G(i) and G(s) in a G-Protein-Coupled Receptor Heterotetramer Guided by a Receptor C-Terminal Domain. BMC Biol. 2018, 16, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferré, S.; Ciruela, F. Functional and Neuroprotective Role of Striatal Adenosine A(2A) Receptor Heterotetramers. J. Caffeine Adenosine Res. 2019, 9, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, I.; Ayoub, M.A.; Fujita, W.; Jaeger, W.C.; Pfleger, K.D.; Devi, L.A. G Protein-Coupled Receptor Heteromers. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2016, 56, 403–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuxe, K.; Borroto-Escuela, D.O.; Marcellino, D.; Romero-Fernandez, W.; Frankowska, M.; Guidolin, D.; Filip, M.; Ferraro, L.; Woods, A.S.; Tarakanov, A.; et al. GPCR Heteromers and Their Allosteric Receptor-Receptor Interactions. Curr. Med. Chem. 2012, 19, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuxe, K.; Marcellino, D.; Leo, G.; Agnati, L.F. Molecular Integration via Allosteric Interactions in Receptor Heteromers. A Working Hypothesis. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2010, 10, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferré, S.; Bonaventura, J.; Tomasi, D.; Navarro, G.; Moreno, E.; Cortés, A.; Lluís, C.; Casadó, V.; Volkow, N.D. Allosteric Mechanisms Within the Adenosine A2A-Dopamine D2 Receptor Heterotetramer. Neuropharmacology 2016, 104, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuxe, K.; Marcellino, D.; Borroto-Escuela, D.O.; Frankowska, M.; Ferraro, L.; Guidolin, D.; Ciruela, F.; Agnati, L.F. The Changing World of G Protein-Coupled Receptors: From Monomers to Dimers and Receptor Mosaics with Allosteric Receptor-Receptor Interactions. J. Recept. Signal Transduct. Res. 2010, 30, 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnati, L.F.; Leo, G.; Genedani, S.; Andreoli, N.; Marcellino, D.; Woods, A.; Piron, L.; Guidolin, D.; Fuxe, K. Structural Plasticity in G-Protein Coupled Receptors As Demonstrated by the Allosteric Actions of Homocysteine and Computer-Assisted Analysis of Disordered Domains. Brain Res. Rev 2008, 58, 459–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnati, L.F.; Guidolin, D.; Vilardaga, J.P.; Ciruela, F.; Fuxe, K. On the Expanding Terminology in the GPCR Field: The Meaning of Receptor Mosaics and Receptor Heteromers. J. Recept. Signal Transduct. Res. 2010, 30, 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popoli, P.; Pèzzola, A.; Torvinen, M.; Reggio, R.; Pintor, A.; Scarchilli, L.; Fuxe, K.; Ferré, S. The Selective MGlu(5) Receptor Agonist CHPG Inhibits Quinpirole-Induced Turning in 6-Hydroxydopamine-Lesioned Rats and Modulates the Binding Characteristics of Dopamine D(2) Receptors in the Rat Striatum: Interactions With Adenosine A(2a) Receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology 2001, 25, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabello, N.; Gandía, J.; Bertarelli, D.C.; Watanabe, M.; Lluís, C.; Franco, R.; Ferré, S.; Luján, R.; Ciruela, F. Metabotropic Glutamate Type 5, Dopamine D2 and Adenosine A2a Receptors Form Higher-Order Oligomers in Living Cells. J. Neurochem. 2009, 109, 1497–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro, G.; Moreno, E.; Bonaventura, J.; Brugarolas, M.; Farré, D.; Aguinaga, D.; Mallol, J.; Cortés, A.; Casadó, V.; Lluís, C.; et al. Cocaine Inhibits Dopamine D2 Receptor Signaling Via Sigma-1-D2 Receptor Heteromers. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borroto-Escuela, D.O.; Wydra, K.; Filip, M.; Fuxe, K. A2AR-D2R Heteroreceptor Complexes in Cocaine Reward and Addiction. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 39, 1008–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Fernandez, W.; Zhou, Z.; Beggiato, S.; Wydra, K.; Filip, M.; Tanganelli, S.; Borroto-Escuela, D.O.; Ferraro, L.; Fuxe, K. Acute Cocaine Treatment Enhances the Antagonistic Allosteric Adenosine A2A-Dopamine D2 Receptor-Receptor Interactions in Rat Dorsal Striatum Without Increasing Significantly Extracellular Dopamine Levels. Pharmacol. Rep. 2020, 72, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuxe, K.; Borroto-Escuela, D.O. Heteroreceptor Complexes and Their Allosteric Receptor-Receptor Interactions as a Novel Biological Principle for Integration of Communication in the CNS: Targets for Drug Development. Neuropsychopharmacology 2016, 41, 380–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferré, S.; Ciruela, F.; Woods, A.S.; Lluis, C.; Franco, R. Functional Relevance of Neurotransmitter Receptor Heteromers in the Central Nervous System. Trends Neurosci. 2007, 30, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purves, D.; Augustine, G.J.; Fitzpatrick, D.; Katz, L.C.; LaMantia, A.S.; McNamara, J.O.; Williams, S.M. Neuroscience; Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- DeLong, M.R. Primate Models of Movement Disorders of Basal Ganglia Origin. Trends Neurosci. 1990, 13, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepper, J.M.; Abercrombie, E.D.; Bolam, J.P. Basal Ganglia Macrocircuits. Prog. Brain Res. 2007, 160, 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Lanciego, J.L.; Luquin, N.; Obeso, J.A. Functional Neuroanatomy of the Basal Ganglia. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012, 2, a009621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parent, A.; Hazrati, L.N. Functional Anatomy of the Basal Ganglia. II. The Place of Subthalamic Nucleus and External Pallidum in Basal Ganglia Circuitry. Brain Res. Rev. 1995, 20, 128–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, P.J.; Kase, H.; Jenner, P.G. Adenosine A2A Receptor Antagonists as New Agents for the Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1997, 18, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, C.E.; Ferré, S. Blocking Striatal Adenosine A2A Receptors: A New Strategy for Basal Ganglia Disorders. Recent Pat. CNS Drug Discov. 2007, 2, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armentero, M.T.; Pinna, A.; Ferré, S.; Lanciego, J.L.; Müller, C.E.; Franco, R. Past, Present and Future of A(2A) Adenosine Receptor Antagonists in the Therapy of Parkinson’s Disease. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 132, 280–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szabó, N.; Kincses, Z.T.; Vécsei, L. Novel Therapy in Parkinson’s Disease: Adenosine A(2A) Receptor Antagonists. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2011, 7, 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preti, D.; Baraldi, P.G.; Moorman, A.R.; Borea, P.A.; Varani, K. History and Perspectives of A2A Adenosine Receptor Antagonists as Potential Therapeutic Agents. Med. Res. Rev. 2015, 35, 790–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, A.; Shindou, T. Modulation of GABAergic Transmission in the Striatopallidal System by Adenosine A2A Receptors: A Potential Mechanism for the Antiparkinsonian Effects of A2A Antagonists. Neurology 2003, 61, S44–S48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuxe, K.; Ferré, S.; Genedani, S.; Franco, R.; Agnati, L.F. Adenosine Receptor-Dopamine Receptor Interactions in the Basal Ganglia and Their Relevance for Brain Function. Physiol. Behav. 2007, 92, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, K.J.; Koller, J.M.; Campbell, M.C.; Gusnard, D.A.; Bandak, S.I. Quantification of Indirect Pathway Inhibition by the Adenosine A2a Antagonist SYN115 in Parkinson Disease. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 16284–16292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoyama, S.; Kase, H.; Borrelli, E. Rescue of Locomotor Impairment in Dopamine D2 Receptor-Deficient Mice by an Adenosine A2A Receptor Antagonist. J. Neurosci. 2000, 20, 5848–5852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strömberg, I.; Popoli, P.; Müller, C.E.; Ferré, S.; Fuxe, K. Electrophysiological and Behavioural Evidence for an Antagonistic Modulatory Role of Adenosine A2A Receptors in Dopamine D2 Receptor Regulation in the Rat Dopamine-Denervated Striatum. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2000, 12, 4033–4037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bové, J.; Marin, C.; Bonastre, M.; Tolosa, E. Adenosine A2A Antagonism Reverses Levodopa-Induced Motor Alterations in Hemiparkinsonian Rats. Synapse 2002, 46, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuya, T.; Takuma, K.; Sato, K.; Asai, M.; Murakami, Y.; Miyoshi, S.; Noda, A.; Nagai, T.; Mizoguchi, H.; Nishimura, S.; et al. Synergistic Effects of Adenosine A2A Antagonist and L-DOPA on Rotational Behaviors in 6-Hydroxydopamine-Induced Hemi-Parkinsonian Mouse Model. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2007, 103, 329–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauber, W.; Neuscheler, P.; Nagel, J.; Müller, C.E. Catalepsy Induced by a Blockade of Dopamine D1 or D2 Receptors Was Reversed by a Concomitant Blockade of Adenosine A(2A) Receptors in the Caudate-Putamen of Rats. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2001, 14, 1287–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanda, T.; Tashiro, T.; Kuwana, Y.; Jenner, P. Adenosine A2A Receptors Modify Motor Function in MPTP-Treated Common Marmosets. Neuroreport 1998, 9, 2857–2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bibbiani, F.; Oh, J.D.; Petzer, J.P.; Castagnoli, N., Jr.; Chen, J.F.; Schwarzschild, M.A.; Chase, T.N. A2A Antagonist Prevents Dopamine Agonist-Induced Motor Complications in Animal Models of Parkinson’s Disease. Exp. Neurol. 2003, 184, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mally, J.; Stone, T.W. The Effect of Theophylline on Parkinsonian Symptoms. J Pharm Pharmacol 1994, 46, 515–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostic, V.S.; Svetel, M.; Sternic, N.; Dragasevic, N.; Przedborski, S. Theophylline Increases “on” Time in Advanced Parkinsonian Patients. Neurology 1999, 52, 1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulisevsky, J.; Barbanoj, M.; Gironell, A.; Antonijoan, R.; Casas, M.; Pascual-Sedano, B. A Double-Blind Crossover, Placebo-Controlled Study of the Adenosine A2A Antagonist Theophylline in Parkinson’s Disease. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 2002, 25, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitagawa, M.; Houzen, H.; Tashiro, K. Effects of Caffeine on the Freezing of Gait in Parkinson’s Disease. Mov. Disord. 2007, 22, 710–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bara-Jimenez, W.; Sherzai, A.; Dimitrova, T.; Favit, A.; Bibbiani, F.; Gillespie, M.; Morris, M.J.; Mouradian, M.M.; Chase, T.N. Adenosine A(2A) Receptor Antagonist Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease. Neurology 2003, 61, 293–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauser, R.A.; Hubble, J.P.; Truong, D.D. Randomized Trial of the Adenosine A(2A) Receptor Antagonist Istradefylline in Advanced PD. Neurology 2003, 61, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stacy, M.A. The US-005/US-006 Clinical Investigator Group. Istradefylline (KW-6002) As Adjunctive Therapy in Patients with Advanced Parkinson’s Disease: A Positive Safety Profile with Supporting Efficacy. Mov. Disord. 2004, 19, S215–S216. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser, R.A.; Shulman, L.M.; Trugman, J.M.; Roberts, J.W.; Mori, A.; Ballerini, R.; Sussman, N.M. Study of Istradefylline in Patients With Parkinson’s Disease on Levodopa With Motor Fluctuations. Mov. Disord. 2008, 23, 2177–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeWitt, P.A.; Guttman, M.; Tetrud, J.W.; Tuite, P.J.; Mori, A.; Chaikin, P.; Sussman, N.M. Adenosine A2A Receptor Antagonist Istradefylline (KW-6002) Reduces "Off" Time in Parkinson’s Disease: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Multicenter Clinical Trial (6002-US-005). Ann. Neurol. 2008, 63, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, H.H.; Greeley, D.R.; Zweig, R.M.; Wojcieszek, J.; Mori, A.; Sussman, N.M. Istradefylline As Monotherapy for Parkinson Disease: Results of the 6002-US-051 Trial. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2010, 16, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, Y.; Kondo, T. Adenosine A2A Receptor Antagonist Istradefylline Reduces Daily off Time in Parkinson’s Disease. Mov. Disord. 2013, 28, 1138–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, T.; Mizuno, Y. A Long-Term Study of Istradefylline Safety and Efficacy in Patients with Parkinson Disease. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 2015, 38, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.; Miyamoto, M.; Miyamoto, T.; Uchiyama, T.; Watanabe, Y.; Suzuki, S.; Kadowaki, T.; Fujita, H.; Matsubara, T.; Sakuramoto, H.; et al. Istradefylline Improves Daytime Sleepiness in Patients With Parkinson’s Disease: An Open-Label, 3-Month Study. J. Neurol. Sci. 2017, 380, 230–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yabe, I.; Kitagawa, M.; Takahashi, I.; Matsushima, M.; Sasaki, H. The Efficacy of Istradefylline for Treating Mild Wearing-Off in Parkinson Disease. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 2017, 40, 261–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iijima, M.; Orimo, S.; Terashi, H.; Suzuki, M.; Hayashi, A.; Shimura, H.; Mitoma, H.; Kitagawa, K.; Okuma, Y. Efficacy of Istradefylline for Gait Disorders With Freezing of Gait in Parkinson’s Disease: A Single-Arm, Open-Label, Prospective, Multicenter Study. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2019, 20, 1405–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauser, R.A.; Olanow, C.W.; Kieburtz, K.D.; Pourcher, E.; Docu-Axelerad, A.; Lew, M.; Kozyolkin, O.; Neale, A.; Resburg, C.; Meya, U.; et al. Tozadenant (SYN115) in Patients With Parkinson’s Disease Who Have Motor Fluctuations on Levodopa: A Phase 2b, Double-Blind, Randomised Trial. Lancet Neurol. 2014, 13, 767–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dungo, R.; Deeks, E.D. Istradefylline: First Global Approval. Drugs 2013, 73, 875–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.F.; Cunha, R.A. The Belated US FDA Approval of the Adenosine A(2A) Receptor Antagonist Istradefylline for Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease. Purinergic Signal. 2020, 16, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeman, P. Targeting the Dopamine D2 Receptor in Schizophrenia. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2006, 10, 515–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferré, S.; O’Connor, W.T.; Snaprud, P.; Ungerstedt, U.; Fuxe, K. Antagonistic Interaction Between Adenosine A2A Receptors and Dopamine D2 Receptors in the Ventral Striopallidal System. Implications for the Treatment of Schizophrenia. Neuroscience 1994, 63, 765–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara, D.R.; Dall’Igna, O.P.; Ghisolfi, E.S.; Brunstein, M.G. Involvement of Adenosine in the Neurobiology of Schizophrenia and Its Therapeutic Implications. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2006, 30, 617–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lara, D.R.; Souza, D.O. Schizophrenia: A Purinergic Hypothesis. Med. Hypotheses 2000, 54, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boison, D.; Singer, P.; Shen, H.Y.; Feldon, J.; Yee, B.K. Adenosine Hypothesis of Schizophrenia--Opportunities for Pharmacotherapy. Neuropharmacology 2012, 62, 1527–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurumaji, A.; Toru, M. An Increase in [3H] CGS21680 Binding in the Striatum of Postmortem Brains of Chronic Schizophrenics. Brain Res. 1998, 808, 320–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deckert, J.; Brenner, M.; Durany, N.; Zöchling, R.; Paulus, W.; Ransmayr, G.; Tatschner, T.; Danielczyk, W.; Jellinger, K.; Riederer, P. Up-Regulation of Striatal Adenosine A(2A) Receptors in Schizophrenia. Neuroreport 2003, 14, 313–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, Y.; Kim, J.; Shin, J.Y.; Kim, J.I.; Seo, J.S.; Webster, M.J.; Lee, D.; Kim, S. Gene Expression Profiling by MRNA Sequencing Reveals Increased Expression of Immune/Inflammation-Related Genes in the Hippocampus of Individuals With Schizophrenia. Transl. Psychiatry 2013, 3, e321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, J.; Liu, L.; Yan, C.; Zhu, X.; Fan, M.; Yu, P.; Ji, K.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, G. Association Between ADORA2A Gene Polymorphisms and Schizophrenia in the North Chinese Han Population. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2019, 15, 2451–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferré, S. Adenosine-Dopamine Interactions in the Ventral Striatum. Implications for the Treatment of Schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology 1997, 133, 107–120. [Google Scholar]

- Borroto-Escuela, D.O.; Ferraro, L.; Narvaez, M.; Tanganelli, S.; Beggiato, S.; Liu, F.; Rivera, A.; Fuxe, K. Multiple Adenosine-Dopamine (A2A-D2 Like) Heteroreceptor Complexes in the Brain and Their Role in Schizophrenia. Cells 2020, 9, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuxe, K.; Borroto-Escuela, D.O.; Tarakanov, A.O.; Romero-Fernandez, W.; Ferraro, L.; Tanganelli, S.; Perez-Alea, M.; Di, P.M.; Agnati, L.F. Dopamine D2 Heteroreceptor Complexes and Their Receptor-Receptor Interactions in Ventral Striatum: Novel Targets for Antipsychotic Drugs. Prog. Brain Res. 2014, 211, 113–139. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rimondini, R.; Ferré, S.; Ogren, S.O.; Fuxe, K. Adenosine A2A Agonists: A Potential New Type of Atypical Antipsychotic. Neuropsychopharmacology 1997, 17, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, M.B.; Fuxe, K.; Werge, T.; Gerlach, J. The Adenosine A2A Receptor Agonist CGS 21680 Exhibits Antipsychotic-Like Activity in Cebus Apella Monkeys. Behav. Pharmacol. 2002, 13, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhondzadeh, S.; Shasavand, E.; Jamilian, H.; Shabestari, O.; Kamalipour, A. Dipyridamole in the Treatment of Schizophrenia: Adenosine-Dopamine Receptor Interactions. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2000, 25, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lara, D.R.; Brunstein, M.G.; Ghisolfi, E.S.; Lobato, M.I.; Belmonte-de-Abreu, P.; Souza, D.O. Allopurinol Augmentation for Poorly Responsive Schizophrenia. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2001, 16, 235–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lara, D.R.; Vianna, M.R.; de Paris, F.; Quevedo, J.; Oses, J.P.; Battastini, A.M.; Sarkis, J.J.; Souza, D.O. Chronic Treatment With Clozapine, but Not Haloperidol, Increases Striatal Ecto-5’-Nucleotidase Activity in Rats. Neuropsychobiology 2001, 44, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durieux, P.F.; Bearzatto, B.; Guiducci, S.; Buch, T.; Waisman, A.; Zoli, M.; Schiffmann, S.N.; de Kerchove, d.A. D2R Striatopallidal Neurons Inhibit Both Locomotor and Drug Reward Processes. Nat. Neurosci. 2009, 12, 393–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wydra, K.; Gawlinski, D.; Gawlinska, K.; Frankowska, M.; Borroto-Escuela, D.O.; Fuxe, K.; Filip, M. Adenosine A(2A)Receptors in Substance Use Disorders: A Focus on Cocaine. Cells 2020, 9, 1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldo, B.A.; Koob, G.F.; Markou, A. Role of Adenosine A2 Receptors in Brain Stimulation Reward under Baseline Conditions and During Cocaine Withdrawal in Rats. J. Neurosci. 1999, 19, 11017–11026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horger, B.A.; Wellman, P.J.; Morien, A.; Davies, B.T.; Schenk, S. Caffeine Exposure Sensitizes Rats to the Reinforcing Effects of Cocaine. Neuroreport 1991, 2, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferré, S. Mechanisms of the Psychostimulant Effects of Caffeine: Implications for Substance Use Disorders. Psychopharmacology 2016, 233, 1963–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, C.M.; Foye, M.M.; Cottam, N.; Ciraulo, D.A.; Kornetsky, C. Adenosine Agonists CGS 21680 and NECA Inhibit the Initiation of Cocaine Self-Administration. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2001, 68, 797–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wydra, K.; Suder, A.; Borroto-Escuela, D.O.; Filip, M.; Fuxe, K. On the Role of A2A and D2 Receptors in Control of Cocaine and Food-Seeking Behaviors in Rats. Psychopharmacology 2015, 232, 1767–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wydra, K.; Suder, A.; Frankowska, M.; Borroto Escuela, D.O.; Fuxe, K.; Filip, M. Effects of Intra-Accumbal or Intra-Prefrontal Cortex Microinjections of Adenosine 2A Receptor Ligands on Responses to Cocaine Reward and Seeking in Rats. Psychopharmacology 2018, 235, 3509–3523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borroto-Escuela, D.O.; Wydra, K.; Li, X.; Rodriguez, D.; Carlsson, J.; Jastrzebska, J.; Filip, M.; Fuxe, K. Disruption of A2AR-D2R Heteroreceptor Complexes After A2AR Transmembrane 5 Peptide Administration Enhances Cocaine Self-Administration in Rats. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018, 55, 7038–7048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borroto-Escuela, D.O.; Wydra, K.; Romero-Fernandez, W.; Zhou, Z.; Frankowska, M.; Filip, M.; Fuxe, K. A2AR Transmembrane 2 Peptide Administration Disrupts the A2AR-A2AR Homoreceptor but Not the A2AR-D2R Heteroreceptor Complex: Lack of Actions on Rodent Cocaine Self-Administration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 6100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filip, M.; Frankowska, M.; Zaniewska, M.; Przegalinski, E.; Muller, C.E.; Agnati, L.; Franco, R.; Roberts, D.C.; Fuxe, K. Involvement of Adenosine A2A and Dopamine Receptors in the Locomotor and Sensitizing Effects of Cocaine. Brain Res. 2006, 1077, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poleszak, E.; Malec, D. Adenosine Receptor Ligands and Cocaine in Conditioned Place Preference (CPP) Test in Rats. Pol. J. Pharmacol. 2002, 54, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Poleszak, E.; Malec, D. Effects of Adenosine Receptor Agonists and Antagonists in Amphetamine-Induced Conditioned Place Preference Test in Rats. Pol. J. Pharmacol. 2003, 55, 319–326. [Google Scholar]

- Bachtell, R.K.; Self, D.W. Effects of Adenosine A2A Receptor Stimulation on Cocaine-Seeking Behavior in Rats. Psychopharmacology 2009, 206, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weerts, E.M.; Griffiths, R.R. The Adenosine Receptor Antagonist CGS15943 Reinstates Cocaine-Seeking Behavior and Maintains Self-Administration in Baboons. Psychopharmacology 2003, 168, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neill, C.E.; LeTendre, M.L.; Bachtell, R.K. Adenosine A2A Receptors in the Nucleus Accumbens Bi-Directionally Alter Cocaine Seeking in Rats. Neuropsychopharmacology 2012, 37, 1245–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, N.S.; O’Neill, C.E.; Hobson, B.D.; Bachtell, R.K. Effects of Adenosine A(2A) Receptor Antagonists on Cocaine-Induced Locomotion and Cocaine Seeking. Psychopharmacology 2019, 236, 699–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orru, M.; Bakesová, J.; Brugarolas, M.; Quiroz, C.; Beaumont, V.; Goldberg, S.R.; Lluís, C.; Cortés, A.; Franco, R.; Casadó, V.; et al. Striatal Pre- and Postsynaptic Profile of Adenosine A(2A) Receptor Antagonists. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e16088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neill, C.E.; Hobson, B.D.; Levis, S.C.; Bachtell, R.K. Persistent Reduction of Cocaine Seeking by Pharmacological Manipulation of Adenosine A1 and A 2A Receptors During Extinction Training in Rats. Psychopharmacology 2014, 231, 3179–3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcellino, D.; Roberts, D.C.; Navarro, G.; Filip, M.; Agnati, L.; Lluís, C.; Franco, R.; Fuxe, K. Increase in A2A Receptors in the Nucleus Accumbens After Extended Cocaine Self-Administration and Its Disappearance After Cocaine Withdrawal. Brain Res. 2007, 1143, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frankowska, M.; Marcellino, D.; Adamczyk, P.; Filip, M.; Fuxe, K. Effects of Cocaine Self-Administration and Extinction on D2 -Like and A2A Receptor Recognition and D2 -Like/Gi Protein Coupling in Rat Striatum. Addict. Biol. 2013, 18, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubrusly, R.C.; Bhide, P.G. Cocaine Exposure Modulates Dopamine and Adenosine Signaling in the Fetal Brain. Neuropharmacology 2010, 58, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romieu, P.; Meunier, J.; Garcia, D.; Zozime, N.; Martin-Fardon, R.; Bowen, W.D.; Maurice, T. The Sigma1 (Sigma1) Receptor Activation Is a Key Step for the Reactivation of Cocaine Conditioned Place Preference by Drug Priming. Psychopharmacology 2004, 175, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kourrich, S.; Su, T.P.; Fujimoto, M.; Bonci, A. The Sigma-1 Receptor: Roles in Neuronal Plasticity and Disease. Trends Neurosci. 2012, 35, 762–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pintsuk, J.; Borroto-Escuela, D.O.; Pomierny, B.; Wydra, K.; Zaniewska, M.; Filip, M.; Fuxe, K. Cocaine Self-Administration Differentially Affects Allosteric A2A-D2 Receptor-Receptor Interactions in the Striatum. Relevance for Cocaine Use Disorder. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2016, 144, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guidolin, D.; Marcoli, M.; Tortorella, C.; Maura, G.; Agnati, L.F. Adenosine A(2A)-Dopamine D(2) Receptor-Receptor Interaction in Neurons and Astrocytes: Evidence and Perspectives. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2020, 169, 247–277. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marcellino, D.; Navarro, G.; Sahlholm, K.; Nilsson, J.; Agnati, L.F.; Canela, E.I.; Lluís, C.; Århem, P.; Franco, R.; Fuxe, K. Cocaine Produces D2R-Mediated Conformational Changes in the Adenosine A(2A)R-Dopamine D2R Heteromer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 394, 988–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filip, M.; Zaniewska, M.; Frankowska, M.; Wydra, K.; Fuxe, K. The Importance of the Adenosine A(2A) Receptor-Dopamine D(2) Receptor Interaction in Drug Addiction. Curr. Med. Chem. 2012, 19, 317–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borroto-Escuela, D.O.; Wydra, K.; Pintsuk, J.; Narvaez, M.; Corrales, F.; Zaniewska, M.; Agnati, L.F.; Franco, R.; Tanganelli, S.; Ferraro, L.; et al. Understanding the Functional Plasticity in Neural Networks of the Basal Ganglia in Cocaine Use Disorder: A Role for Allosteric Receptor-Receptor Interactions in A2A-D2 Heteroreceptor Complexes. Neural Plast. 2016, 2016, 4827268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballesteros-Yáñez, I.; Castillo, C.A.; Merighi, S.; Gessi, S. The Role of Adenosine Receptors in Psychostimulant Addiction. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volkow, N.D.; Wang, G.J.; Kollins, S.H.; Wigal, T.L.; Newcorn, J.H.; Telang, F.; Fowler, J.S.; Zhu, W.; Logan, J.; Ma, Y.; et al. Evaluating Dopamine Reward Pathway in ADHD: Clinical Implications. JAMA 2009, 302, 1084–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volkow, N.D.; Wang, G.J.; Newcorn, J.H.; Kollins, S.H.; Wigal, T.L.; Telang, F.; Fowler, J.S.; Goldstein, R.Z.; Klein, N.; Logan, J.; et al. Motivation Deficit in ADHD Is Associated With Dysfunction of the Dopamine Reward Pathway. Mol. Psychiatry 2011, 16, 1147–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comings, D.E.; Gade-Andavolu, R.; Gonzalez, N.; Wu, S.; Muhleman, D.; Blake, H.; Chiu, F.; Wang, E.; Farwell, K.; Darakjy, S.; et al. Multivariate Analysis of Associations of 42 Genes in ADHD, ODD and Conduct Disorder. Clin. Genet. 2000, 58, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molero, Y.; Gumpert, C.; Serlachius, E.; Lichtenstein, P.; Walum, H.; Johansson, D.; Anckarsäter, H.; Westberg, L.; Eriksson, E.; Halldner, L. A Study of the Possible Association between Adenosine A2A Receptor Gene Polymorphisms and Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Traits. Genes Brain Behav. 2013, 12, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuo, Y.; Ishido, M.; Morita, M.; Sawa, H.; Nagashima, K.; Niki, E. Behavioural Characteristics and Gene Expression in the Hyperactive Wiggling (Wig) Rat. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2007, 25, 3659–3666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandolfo, P.; Machado, N.J.; Köfalvi, A.; Takahashi, R.N.; Cunha, R.A. Caffeine Regulates Frontocorticostriatal Dopamine Transporter Density and Improves Attention and Cognitive Deficits in an Animal Model of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013, 23, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pires, V.A.; Pamplona, F.A.; Pandolfo, P.; Fernandes, D.; Prediger, R.D.; Takahashi, R.N. Adenosine Receptor Antagonists Improve Short-Term Object-Recognition Ability of Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats: A Rodent Model of Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Behav. Pharmacol. 2009, 20, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, C.B.; Almeida, A.S.; Marques, D.M.; Faé, A.H.L.; Machado, A.C.L.; Oliveira, D.L.; Portela, L.V.C.; Porciúncula, L.O. Caffeine and Adenosine A(2A) Receptors Rescue Neuronal Development in Vitro of Frontal Cortical Neurons in a Rat Model of Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder. Neuropharmacology 2020, 166, 107782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraporti, T.T.; Contini, V.; Tovo-Rodrigues, L.; Recamonde-Mendoza, M.; Rovaris, D.L.; Rohde, L.A.; Hutz, M.H.; Salatino-Oliveira, A.; Genro, J.P. Synergistic Effects Between ADORA2A and DRD2 Genes on Anxiety Disorders in Children with ADHD. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2019, 93, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, H.; Köhler, C.; Gawell, L.; Farde, L.; Sedvall, G. Raclopride, a New Selective Ligand for the Dopamine-D2 Receptors. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 1988, 12, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsinga, P.H.; Hatano, K.; Ishiwata, K. PET Tracers for Imaging of the Dopaminergic System. Curr. Med. Chem. 2006, 13, 2139–2153. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Prante, O.; Maschauer, S.; Banerjee, A. Radioligands for the Dopamine Receptor Subtypes. J. Labelled Comp. Radiopharm. 2013, 56, 130–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, A.; Prante, O. Subtype-Selective Dopamine Receptor Radioligands for PET Imaging: Current Status and Recent Developments. Curr. Med. Chem. 2012, 19, 3957–3966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mach, R.H.; Luedtke, R.R. Challenges in the Development of Dopamine D2- and D3-Selective Radiotracers for PET Imaging Studies. J. Labelled Comp. Radiopharm. 2018, 61, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Márián, T.; Boros, I.; Lengyel, Z.; Balkay, L.; Horváth, G.; Emri, M.; Sarkadi, E.; Szentmiklósi, A.J.; Fekete, I.; Trón, L. Preparation and Primary Evaluation of [11C]CSC As a Possible Tracer for Mapping Adenosine A2A Receptors by PET. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 1999, 50, 887–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishiwata, K.; Shimada, J.; Wang, W.F.; Harakawa, H.; Ishii, S.; Kiyosawa, M.; Suzuki, F.; Senda, M. Evaluation of Iodinated and Brominated [11C]Styrylxanthine Derivatives As in Vivo Radioligands Mapping Adenosine A2A Receptor in the Central Nervous System. Ann. Nucl. Med. 2000, 14, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, P.T.; Dall’Angelo, S.; Mulder-Krieger, T.; IJzerman, A.P.; Zanda, M.; O’Hagan, D. A New Class of Fluorinated A(2A) Adenosine Receptor Agonist With Application to Last-Step Enzymatic [(18) F]Fluorination for PET Imaging. Chembiochem 2017, 18, 2156–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharjee, A.K.; Lang, L.; Jacobson, O.; Shinkre, B.; Ma, Y.; Niu, G.; Trenkle, W.C.; Jacobson, K.A.; Chen, X.; Kiesewetter, D.O. Striatal Adenosine A(2A) Receptor-Mediated Positron Emission Tomographic Imaging in 6-Hydroxydopamine-Lesioned Rats Using [(18)F]-MRS5425. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2011, 38, 897–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schröder, S.; Lai, T.H.; Toussaint, M.; Kranz, M.; Chovsepian, A.; Shang, Q.; Dukic-Stefanovic, S.; Deuther-Conrad, W.; Teodoro, R.; Wenzel, B.; et al. PET Imaging of the Adenosine A(2A) Receptor in the Rotenone-Based Mouse Model of Parkinson’s Disease With [(18)F]FESCH Synthesized by a Simplified Two-Step One-Pot Radiolabeling Strategy. Molecules 2020, 25, 1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanapur, S.; Paul, S.; Shah, A.; Vatakuti, S.; Koole, M.J.; Zijlma, R.; Dierckx, R.A.; Luurtsema, G.; Garg, P.; Van Waarde, A.; et al. Development of [18F]-Labeled Pyrazolo[4,3-e]-1,2,4- Triazolo[1,5-c]Pyrimidine (SCH442416) Analogs for the Imaging of Cerebral Adenosine A2A Receptors With Positron Emission Tomography. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 6765–6780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanapur, S.; Van Waarde, A.; Dierckx, R.A.; Elsinga, P.H.; Koole, M.J. Preclinical Evaluation and Quantification of (18)F-Fluoroethyl and (18)F-Fluoropropyl Analogs of SCH442416 As Radioligands for PET Imaging of the Adenosine A(2A) Receptor in Rat Brain. J. Nucl. Med. 2017, 58, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirani, E.; Gillies, J.; Karasawa, A.; Shimada, J.; Kase, H.; Opacka-Juffry, J.; Osman, S.; Luthra, S.K.; Hume, S.P.; Brooks, D.J. Evaluation of [4-O-Methyl-(11)C]KW-6002 As a Potential PET Ligand for Mapping Central Adenosine A(2A) Receptors in Rats. Synapse 2001, 42, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, D.J.; Doder, M.; Osman, S.; Luthra, S.K.; Hirani, E.; Hume, S.; Kase, H.; Kilborn, J.; Martindill, S.; Mori, A. Positron Emission Tomography Analysis of [11C]KW-6002 Binding to Human and Rat Adenosine A2A Receptors in the Brain. Synapse 2008, 62, 671–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishiwata, K.; Noguchi, J.; Toyama, H.; Sakiyama, Y.; Koike, N.; Ishii, S.; Oda, K.; Endo, K.; Suzuki, F.; Senda, M. Synthesis and Preliminary Evaluation of [11C]KF17837, a Selective Adenosine A2A Antagonist. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 1996, 47, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishiwata, K.; Sakiyama, Y.; Sakiyama, T.; Shimada, J.; Toyama, H.; Oda, K.; Suzuki, F.; Senda, M. Myocardial Adenosine A2a Receptor Imaging of Rabbit by PET With [11C]KF17837. Ann. Nucl. Med. 1997, 11, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguchi, J.; Ishiwata, K.; Wakabayashi, S.; Nariai, T.; Shumiya, S.; Ishii, S.; Toyama, H.; Endo, K.; Suzuki, F.; Senda, M. Evaluation of Carbon-11-Labeled KF17837: A Potential CNS Adenosine A2a Receptor Ligand. J. Nucl. Med. 1998, 39, 498–503. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stone-Elander, S.; Thorell, J.O.; Eriksson, L.; Fredholm, B.B.; Ingvar, M. In Vivo Biodistribution of [N-11C-Methyl]KF 17837 Using 3-D-PET: Evaluation As a Ligand for the Study of Adenosine A2A Receptors. Nucl. Med. Biol. 1997, 24, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishiwata, K.; Noguchi, J.; Wakabayashi, S.; Shimada, J.; Ogi, N.; Nariai, T.; Tanaka, A.; Endo, K.; Suzuki, F.; Senda, M. 11C-Labeled KF18446: A Potential Central Nervous System Adenosine A2a Receptor Ligand. J. Nucl. Med. 2000, 41, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ishiwata, K.; Ogi, N.; Shimada, J.; Nonaka, H.; Tanaka, A.; Suzuki, F.; Senda, M. Further Characterization of a CNS Adenosine A2a Receptor Ligand [11C]KF18446 with in Vitro Autoradiography and in Vivo Tissue Uptake. Ann. Nucl. Med. 2000, 14, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishiwata, K.; Ogi, N.; Shimada, J.; Wang, W.; Ishii, K.; Tanaka, A.; Suzuki, F.; Senda, M. Search for PET Probes for Imaging the Globus Pallidus Studied With Rat Brain Ex Vivo Autoradiography. Ann. Nucl. Med. 2000, 14, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishiwata, K.; Ogi, N.; Hayakawa, N.; Oda, K.; Nagaoka, T.; Toyama, H.; Suzuki, F.; Endo, K.; Tanaka, A.; Senda, M. Adenosine A2A Receptor Imaging With [11C]KF18446 PET in the Rat Brain After Quinolinic Acid Lesion: Comparison With the Dopamine Receptor Imaging. Ann. Nucl. Med. 2002, 16, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishiwata, K.; Wang, W.F.; Kimura, Y.; Kawamura, K.; Ishii, K. Preclinical Studies on [11C]TMSX for Mapping Adenosine A2A Receptors by Positron Emission Tomography. Ann. Nucl. Med. 2003, 17, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishiwata, K.; Mizuno, M.; Kimura, Y.; Kawamura, K.; Oda, K.; Sasaki, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Muraoka, I.; Ishii, K. Potential of [11C]TMSX for the Evaluation of Adenosine A2A Receptors in the Skeletal Muscle by Positron Emission Tomography. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2004, 31, 949–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishiwata, K.; Kawamura, K.; Kimura, Y.; Oda, K.; Ishii, K. Potential of an Adenosine A2A Receptor Antagonist [11C]TMSX for Myocardial Imaging by Positron Emission Tomography: A First Human Study. Ann. Nucl. Med. 2003, 17, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishiwata, K.; Mishina, M.; Kimura, Y.; Oda, K.; Sasaki, T.; Ishii, K. First Visualization of Adenosine A(2A) Receptors in the Human Brain by Positron Emission Tomography With [11C]TMSX. Synapse 2005, 55, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, M.; Kimura, Y.; Tokizawa, K.; Ishii, K.; Oda, K.; Sasaki, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Muraoka, I.; Ishiwata, K. Greater Adenosine A(2A) Receptor Densities in Cardiac and Skeletal Muscle in Endurance-Trained Men: A [11C]TMSX PET Study. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2005, 32, 831–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishina, M.; Ishiwata, K.; Kimura, Y.; Naganawa, M.; Oda, K.; Kobayashi, S.; Katayama, Y.; Ishii, K. Evaluation of Distribution of Adenosine A2A Receptors in Normal Human Brain Measured With [11C]TMSX PET. Synapse 2007, 61, 778–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishina, M.; Ishiwata, K.; Naganawa, M.; Kimura, Y.; Kitamura, S.; Suzuki, M.; Hashimoto, M.; Ishibashi, K.; Oda, K.; Sakata, M.; et al. Adenosine A(2A) Receptors Measured With [C]TMSX PET in the Striata of Parkinson’s Disease Patients. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e17338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinonen, I.; Nesterov, S.V.; Liukko, K.; Kemppainen, J.; Någren, K.; Luotolahti, M.; Virsu, P.; Oikonen, V.; Nuutila, P.; Kujala, U.M.; et al. Myocardial Blood Flow and Adenosine A2A Receptor Density in Endurance Athletes and Untrained Men. J. Physiol. 2008, 586, 5193–5202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rissanen, E.; Virta, J.R.; Paavilainen, T.; Tuisku, J.; Helin, S.; Luoto, P.; Parkkola, R.; Rinne, J.O.; Airas, L. Adenosine A2A Receptors in Secondary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis: A [(11)C]TMSX Brain PET Study. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2013, 33, 1394–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rissanen, E.; Tuisku, J.; Luoto, P.; Arponen, E.; Johansson, J.; Oikonen, V.; Parkkola, R.; Airas, L.; Rinne, J.O. Automated Reference Region Extraction and Population-Based Input Function for Brain [(11)C]TMSX PET Image Analyses. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2015, 35, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naganawa, M.; Kimura, Y.; Mishina, M.; Manabe, Y.; Chihara, K.; Oda, K.; Ishii, K.; Ishiwata, K. Quantification of Adenosine A2A Receptors in the Human Brain Using [11C]TMSX and Positron Emission Tomography. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2007, 34, 679–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naganawa, M.; Kimura, Y.; Yano, J.; Mishina, M.; Yanagisawa, M.; Ishii, K.; Oda, K.; Ishiwata, K. Robust Estimation of the Arterial Input Function for Logan Plots Using an Intersectional Searching Algorithm and Clustering in Positron Emission Tomography for Neuroreceptor Imaging. Neuroimage 2008, 40, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naganawa, M.; Mishina, M.; Sakata, M.; Oda, K.; Hiura, M.; Ishii, K.; Ishiwata, K. Test-Retest Variability of Adenosine A2A Binding in the Human Brain With (11)C-TMSX and PET. EJNMMI Res 2014, 4, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishina, M.; Kimura, Y.; Naganawa, M.; Ishii, K.; Oda, K.; Sakata, M.; Toyohara, J.; Kobayashi, S.; Katayama, Y.; Ishiwata, K. Differential Effects of Age on Human Striatal Adenosine A1 and A2A Receptors. Synapse 2012, 66, 832–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahesmaa, M.; Oikonen, V.; Helin, S.; Luoto, P.; Din, U.; Pfeifer, A.; Nuutila, P.; Virtanen, K.A. Regulation of Human Brown Adipose Tissue by Adenosine and A(2A) Receptors Studies with [(15)O]H(2)O and [(11)C]TMSX PET/CT. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2019, 46, 743–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.F.; Ishiwata, K.; Nonaka, H.; Ishii, S.; Kiyosawa, M.; Shimada, J.; Suzuki, F.; Senda, M. Carbon-11-Labeled KF21213: A Highly Selective Ligand for Mapping CNS Adenosine A(2A) Receptors With Positron Emission Tomography. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2000, 27, 541–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barret, O.; Hannestad, J.; Alagille, D.; Vala, C.; Tavares, A.; Papin, C.; Morley, T.; Fowles, K.; Lee, H.; Seibyl, J.; et al. Adenosine 2A Receptor Occupancy by Tozadenant and Preladenant in Rhesus Monkeys. J. Nucl. Med. 2014, 55, 1712–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vala, C.; Morley, T.J.; Zhang, X.; Papin, C.; Tavares, A.A.; Lee, H.S.; Constantinescu, C.; Barret, O.; Carroll, V.M.; Baldwin, R.M.; et al. Synthesis and in Vivo Evaluation of Fluorine-18 and Iodine-123 Pyrazolo[4,3-e]-1,2,4-Triazolo[1,5-c] Pyrimidine Derivatives As PET and SPECT Radiotracers for Mapping A2A Receptors. ChemMedChem 2016, 11, 1936–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barret, O.; Hannestad, J.; Vala, C.; Alagille, D.; Tavares, A.; Laruelle, M.; Jennings, D.; Marek, K.; Russell, D.; Seibyl, J.; et al. Characterization in Humans of 18F-MNI-444, a PET Radiotracer for Brain Adenosine 2A Receptors. J. Nucl. Med. 2015, 56, 586–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Khanapur, S.; Huizing, A.P.; Zijlma, R.; Schepers, M.; Dierckx, R.A.; Van Waarde, A.; de Vries, E.F.; Elsinga, P.H. Synthesis and Preclinical Evaluation of 2-(2-Furanyl)-7-[2-[4-[4-(2-[11C]Methoxyethoxy)Phenyl]-1-Piperazinyl]Ethyl]7H-Pyrazolo[4,3-e][1,2,4]Triazolo[1,5-c]Pyrimidine-5-Amine ([11C]Preladenant) As a PET Tracer for the Imaging of Cerebral Adenosine A2A Receptors. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 9204–9210. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Elsinga, P.H.; Khanapur, S.; Dierckx, R.A.; de Vries, E.F.; de Jong, J.R. Radiation Dosimetry of a Novel Adenosine A(2A) Receptor Radioligand [(11)C]Preladenant Based on PET/CT Imaging and Ex Vivo Biodistribution in Rats. Mol. Imaging Biol. 2017, 19, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Khanapur, S.; de Jong, J.R.; Willemsen, A.T.; Dierckx, R.A.; Elsinga, P.H.; de Vries, E.F. In Vivo Evaluation of [(11)C]Preladenant Positron Emission Tomography for Quantification of Adenosine A(2A) Receptors in the Rat Brain. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2017, 37, 577–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Doorduin, J.; Elsinga, P.H.; Dierckx, R.A.J.O.; de Vries, E.F.J.; Casteels, C. Altered Adenosine 2A and Dopamine D2 Receptor Availability in the 6-Hydroxydopamine-Treated Rats With and Without Levodopa-Induced Dyskinesia. Neuroimage 2017, 157, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Boellaard, R.; Ishiwata, K.; Sakata, M.; Dierckx, R.A.J.O.; de Jong, J.R.; Nishiyama, S.; Ohba, H.; Tsukada, H.; de Vries, E.F.J.; et al. In Vivo Evaluation of (11)C-Preladenant for PET Imaging of Adenosine A(2A) Receptors in the Conscious Monkey. J. Nucl. Med. 2017, 58, 762–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishibashi, K.; Miura, Y.; Wagatsuma, K.; Toyohara, J.; Ishiwata, K.; Ishii, K. Occupancy of Adenosine A(2A) Receptors by Istradefylline in Patients With Parkinson’s Disease Using (11)C-Preladenant PET. Neuropharmacology 2018, 143, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakata, M.; Ishibashi, K.; Imai, M.; Wagatsuma, K.; Ishii, K.; Zhou, X.; de Vries, E.F.J.; Elsinga, P.H.; Ishiwata, K.; Toyohara, J. Initial Evaluation of an Adenosine A(2A) Receptor Ligand, (11)C-Preladenant, in Healthy Human Subjects. J. Nucl. Med. 2017, 58, 1464–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moresco, R.M.; Todde, S.; Belloli, S.; Simonelli, P.; Panzacchi, A.; Rigamonti, M.; Galli-Kienle, M.; Fazio, F. In Vivo Imaging of Adenosine A2A Receptors in Rat and Primate Brain Using [11C]SCH442416. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2005, 32, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todde, S.; Moresco, R.M.; Simonelli, P.; Baraldi, P.G.; Cacciari, B.; Spalluto, G.; Varani, K.; Monopoli, A.; Matarrese, M.; Carpinelli, A.; et al. Design, Radiosynthesis, and Biodistribution of a New Potent and Selective Ligand for in Vivo Imaging of the Adenosine A(2A) Receptor System Using Positron Emission Tomography. J. Med. Chem. 2000, 43, 4359–4362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihara, T.; Noda, A.; Arai, H.; Mihara, K.; Iwashita, A.; Murakami, Y.; Matsuya, T.; Miyoshi, S.; Nishimura, S.; Matsuoka, N. Brain Adenosine A2A Receptor Occupancy by a Novel A1/A2A Receptor Antagonist, ASP5854, in Rhesus Monkeys: Relationship to Anticataleptic Effect. J. Nucl. Med. 2008, 49, 1183–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]