Role of Oral Antioxidant Supplementation in the Current Management of Diabetic Retinopathy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Epidemiology and Risk Factors

3. Pathophysiology

- Inflammation: Microglial activation seems to be an early event in DR and can trigger the secretion of inflammatory mediators [21,22]. Proinflammatory cytokines (interleukins IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α) have been reported in higher levels in human vitreous samples [23,24], and have also correlated with the severity of DR [25]. Under inflammatory stimuli, endothelial cells increase the expression of intracellular and vascular adhesion molecules (ICAM-1 and VCAM-1) and E-selectin, allowing leukocyte adhesion to the endothelial cell walls and the production of leukostasis, which is a determining factor for posterior microvascular damage [26,27]. Increased levels of the above-mentioned molecules have been reported in diabetic blood samples [28], and the inhibition of ICAM-1 in cultured human retinal endothelial cells from diabetic patients reduced cell apoptosis. Interestingly, the use of an antioxidant agent reduced the levels of ICAM-1 on those retinal cultures and was able to reduce cellular loss [29].

- Neurodegeneration: Apoptosis seems to affect neurons before vascular cells. Electroretinogram (ERG) studies have shown the possibility of existing neuronal damage even before DR clinical signs were present, preceding microvascular changes. Furthermore, retinal analysis has demonstrated a thinner ganglion cell inner layer both in diabetic animal models and human subjects [30,31,32]. With regard to the role of oxidative stress in relation to neurodegeneration, ERG studies have been carried out on induced-diabetes mice, before and after antioxidant administration, thus verifying the protective role of lutein both on visual function and histological neuronal changes [31].

- Microvasculopathy: The walls of retinal capillaries have an external pericytes layer, a basement membrane and an inner endothelial cells layer. Pericyte loss occurs under hyperglycaemic conditions [33] and leads to focal microvascular dilatation with microaneurysm formation. A thickening of the basement membrane, due to debris deposition and endothelial cell dysfunction, leads to blood–retinal barrier (BRB) disruption, producing increased vascular permeability with exudation and haemorrhages [34]. Leukostasis derived from an inflammatory response is involved in endothelial cell impairment and is followed by microvascular occlusions [27]. Subsequent hypoxia promotes the activation of transcription factor hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1), which further stimulates the secretion of vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGFs), and therefore causes neovessel formation [35].

4. Important Role of Early Diagnosis

4.1. Classification of DR

4.2. Impact on Visual Impairment

5. Imaging Techniques for Diabetic Retinopathy Screening

5.1. Fundus Photography

5.2. Ultrawide-Field Imaging for Diabetic Retinopathy Screening

5.3. Optical Coherence Tomography for Diabetic Macular Oedema Screening

5.4. OCT Angiography in Diabetic Retinopathy Screening

5.5. Smartphone Function in Diabetic Retinopathy Screening

5.6. Automated DR Image Evaluation Systems Used for Teleophthalmology

6. Pathology Control and Monitoring

6.1. First Visit

6.1.1. Grade the Diabetic Retinopathy

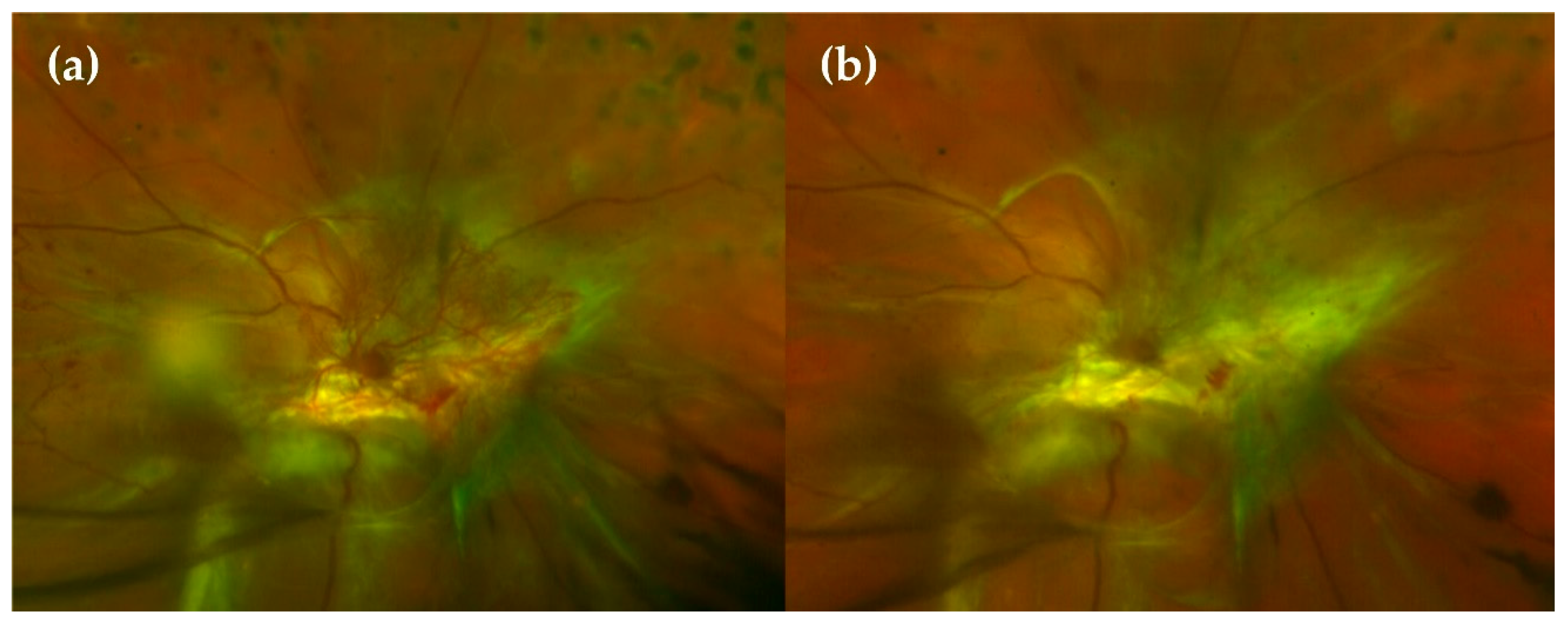

- Wide-field fluorescein angiography (WF-FA): Though some guidelines recommend performing FA on a case-by-case basis prior to macular laser treatment [60], analysing peripheral retina vascularisation is fundamental for DR management as global ischaemia is related to neovascularisation, which indicates treatment to prevent PDR [63]. As wide-field OCT angiography (WF-OCTA) is as yet uncommon, our group recommend performing a WF-FA at a moderate NPDR stage. WF-FA is also, to date, the best exploration for grading DR [64], detecting 1.6 to 3.5-fold more fields affecting DR severity than ultrawide-field colour imaging (Figure 2).

- Optical coherence tomography (OCT): OCT should be mandatory at every DR visit as several DMEs can only be seen in OCT examination. OCT is also the most useful imaging modality for calculating and monitoring the individual treatment response to anti-VEGF treatment [65].

- OCT angiography (OCT-A): OCT-A can demonstrate areas of capillary nonperfusion and it is very useful for assessing patients with DR and loss of visual acuity without central oedema. An increase in the area of the foveal avascular zone has been associated with worse visual acuity [60,66,67,68] (Figure 3).

6.1.2. Educational Advice

6.1.3. Establishing Goals for Controlling the Risk Factors Associated with DR Progression

- HbA1c < 7%: HbA1c control has a memory effect, in other words, the effect of the correct control over time protects against the progression of DR in the case of a future uncontrolled period [72]. Therefore, the early intervention in this parameter is essential. A 1% reduction in HbA1c is associated with a 35% reduction in the risk of developing DR, 15–25% in its progression, 25% in VA loss and 15% in developing blindness [73]. In T1DM compared to HbA1c of 9%, HbA1c under 7% diminishes the development of DR in 75% of cases and progression in 50%. Despite the importance of diminishing HbA1c, this reduction should not be acute, because, apart from the risk of hypoglycaemia, this reduction could promote DR progression, as shown in a study focusing on obese patients who underwent bariatric surgery. Notably, 18.9% of the patients who did not have DR before surgery developed DR in the first year after the procedure [74]. A DR study by an ophthalmologist is recommended before bariatric surgery. The goal of a HbA1c under 7% is variable depending on the patient [75]. A value under 6.5% is recommended if there is a risk of nephropathy and DR. A value between 7.1 and 8.5% could be tolerated if there are multiple comorbidities and if, despite maximum treatment, it is difficult to reach a value below 7%.

- BP < 150/85: When comparing patients with BPs under 180/10 mmHg with patients under 150/85 mmHg, there is a 33% reduction in the progression of DR and the necessity of laser treatment and a 50% reduction in vision loss in patients with lower BPs [76]. Although these data are classic, two more modern reviews and a meta-analysis indicate that reducing BP prevents the development of DR for up to four to five years [77] and reduces the relative risk of incidence of DR by 17% [78], but there is no clear evidence on slowing the progression once the disease has developed. In contrast to glycaemic control, BP control does not have a memory effect; once it becomes decompensated, the risk of progression of the disease increases regardless of the previous control.

- Obesity: A meta-analysis published in 2018 showed that obesity increased DR with a relative risk of 1.2, more in T2DM. Obesity was not associated with PDR [81].

- Smoking: The association of smoking and DR has been established for T1DM, but not for T2DM [82].

6.2. Follow-Ups

6.3. Consideration of Special Situations

6.3.1. DR and Pregnancy

6.3.2. DR and Cataract

7. Current Medical Treatment and Future Therapeutic Approaches

7.1. Nonsevere Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy. Anti-VEGF, PRP or Both?

7.2. Clinically Significant Macular Oedema (CSME)

8. Role of Oral Antioxidant Supplementation

- Enzymatic antioxidantsThe enzymatic agents accomplish their antioxidant activity by disintegrating and removing free radicals. These are intrinsic intracytosolic enzymes (catalase, superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase and peroxiredoxin) that carry chemical reactions in the presence of several cofactors, such as coenzyme Q10 (ubiquinone), copper (Cu), manganese (Mn), zinc (Zn) or selenium (Se). These cofactors have been added to oral supplementation to promote the inherent mechanisms of auto-defence in the cells [136,137,138].

- Nonenzymatic antioxidantsThe nonenzymatic agents act at a second level, disrupting the free radical chain reactions. The majority of them can be extracted from natural sources (plants and fruits), and the following categories are included within this group [130,136]:

- ◦

- Vitamins: C, E and A.

- ◦

- Polyphenols

- ▪

- Flavonoids: large group of agents including flavonols, flavones, flavanones, flavanols (example: pycnogenol containing catechin and epicatechin), anthocyanins, isoflavonoids, homoisoflavonoids and chalcones.

- ▪

- Nonflavonoids

- Hydroxycinnamic acids: curcumin.

- Stilbenes: resveratrol and pterostilbene.

- ◦

- Carotenoids: lutein, zeaxanthin, crocin and crocetin.

- OthersAlpha-lipoic acid [139], omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids [140], calcium dobesilate [141], Asiatic acid, extracts of Gingkgo biloba, turmeric root.Formulae containing different blends of the mentioned agents have been commercialised and used as in ophthalmologic pathologies [7,142,143]. Among them, Nutrof Omega®, Brudy Retina®, Diaberet® and Vitalux Forte® have been tested in patients suffering from DR. Divfuss® was specifically developed for the Diabetes Visual Function Supplement Study [144]. Their composition and effects are discussed later. From them, Diaberet® and Vitalux Forte® are no longer available and their formulae have been updated to Visucomplex Plus® and Vitalux Plus® by the corresponding laboratories.Is it time to include oral antioxidants in the daily management of DR patients? In order to answer this question, a systematic review of studies on antioxidant oral supplementation in DR patients is presented.

8.1. Methods

8.2. Results

- Clinical variablesDR onset or progressionDME onset or progressionBest corrected visual acuity (BCVA) improvementCentral macular thickness (CMT) changesRetinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thickness changesRetinal blood flow changesNumber of Ranibizumab intravitreal injections required

- Functional variablesRetinal sensitivity (dB)Contrast sensitivityGlare sensitivityMacular pigment ocular density (MPOD)

- Biochemical variablesHbA1c% valuesHigh-density lipoprotein (HDL)/Low-density lipoprotein (LDL)/total cholesterol/triglyceride levelsLipid peroxidation products levelsPlasma total antioxidant capacityROS levelsInterleukin 6 (IL-6) plasma levelsMicroalbuminuriaCreatinine clearance

8.3. Discussion

8.3.1. Clinical Variables Results

8.3.2. Functional Variables Results

8.3.3. Biochemical Variables Results

8.3.4. Safety Profile

8.3.5. Limitations

8.4. Conclusions

9. The Future

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yau, J.W.; Rogers, S.L.; Kawasaki, R.; Lamoureux, E.L.; Kowalski, J.W.; Bek, T.; Chen, S.J.; Dekker, J.M.; Fletcher, A.; Grauslund, J.; et al. Global prevalence and major risk factors of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 556–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Williams, R.; Colagiuri, S.; Chan, J.; Gregg, E.W.; Ke, C.; Lim, L.-L.; Yang, X. IDF Diabetes Atlas 2019; International Diabetes Foundation. 2019. Available online: https://www.diabetesatlas.org/upload/resources/material/20200302_133351_IDFATLAS9e-final-web.pdf (accessed on 13 March 2021).

- Wong, T.Y.; Sun, J.; Kawasaki, R.; Ruamviboonsuk, P.; Gupta, N.; Lansingh, V.C.; Maia, M.; Mathenge, W.; Moreker, S.; Muqit, M.M.K.; et al. Guidelines on Diabetic Eye Care: The International Council of Ophthalmology Recommendations for Screening, Follow-up, Referral, and Treatment Based on Resource Settings. Ophthalmology 2018, 125, 1608–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beagley, J.; Guariguata, L.; Weil, C.; Motala, A.A. Global estimates of undiagnosed diabetes in adults. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2014, 103, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownlee, M. The pathobiology of diabetic complications: A unifying mechanism. Diabetes 2005, 54, 1615–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kowluru, R.A.; Chan, P.S. Oxidative stress and diabetic retinopathy. Exp. Diabetes Res. 2007, 2007, 43603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Garcia-Medina, J.J.; Rubio-Velazquez, E.; Foulquie-Moreno, E.; Casaroli-Marano, R.P.; Pinazo-Duran, M.D.; Zanon-Moreno, V.; Del-Rio-Vellosillo, M. Update on the Effects of Antioxidants on Diabetic Retinopathy: In Vitro Experiments, Animal Studies and Clinical Trials. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flaxman, S.R.; Bourne, R.R.A.; Resnikoff, S.; Ackland, P.; Braithwaite, T.; Cicinelli, M.V.; Das, A.; Jonas, J.B.; Keeffe, J.; Kempen, J.H.; et al. Global causes of blindness and distance vision impairment 1990–2020: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2017, 5, e1221–e1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bourne, R.R.; Stevens, G.A.; White, R.A.; Smith, J.L.; Flaxman, S.R.; Price, H.; Jonas, J.B.; Keeffe, J.; Leasher, J.; Naidoo, K.; et al. Causes of vision loss worldwide, 1990-2010: A systematic analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2013, 1, e339–e349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rodriguez, M.L.; Perez, S.; Mena-Molla, S.; Desco, M.C.; Ortega, A.L. Oxidative Stress and Microvascular Alterations in Diabetic Retinopathy: Future Therapies. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2019, 2019, 4940825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Romero-Aroca, P.; Navarro-Gil, R.; Valls-Mateu, A.; Sagarra-Alamo, R.; Moreno-Ribas, A.; Soler, N. Differences in incidence of diabetic retinopathy between type 1 and 2 diabetes mellitus: A nine-year follow-up study. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 101, 1346–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wong, M.Y.Z.; Man, R.E.K.; Fenwick, E.K.; Gupta, P.; Li, L.J.; van Dam, R.M.; Chong, M.F.; Lamoureux, E.L. Dietary intake and diabetic retinopathy: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0186582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT)/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (EDIC) Study Research Group. Intensive Diabetes Treatment and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 1 Diabetes: The DCCT/EDIC Study 30-Year Follow-up. Diabetes Care 2016, 39, 686–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Effect of intensive blood-glucose control with metformin on complications in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 34). Lancet 1998, 352, 854–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.Y.; Yiang, G.T.; Lai, T.T.; Li, C.J. The Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction during the Pathogenesis of Diabetic Retinopathy. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2018, 2018, 3420187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Zhu, X.; Hu, Y.; Li, T.; Gao, Y.; Shi, Y.; Tang, S. Mitochondrial DNA oxidative damage triggering mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis in high glucose-induced HRECs. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2008, 49, 4203–4209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen-Bouterse, S.A.; Mohammad, G.; Kanwar, M.; Kowluru, R.A. Role of mitochondrial DNA damage in the development of diabetic retinopathy, and the metabolic memory phenomenon associated with its progression. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 2010, 13, 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, H.; Guan, W.; Kang, X.; Tai, X.; Shen, Y. Metabolic memory in mitochondrial oxidative damage triggers diabetic retinopathy. BMC Ophthalmol. 2018, 18, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, C.C.; Silva, K.C.; Biswas, S.K.; Martins, N.; De Faria, J.B.; De Faria, J.M. Arterial hypertension exacerbates oxidative stress in early diabetic retinopathy. Free Radic. Res. 2007, 41, 1151–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Lo, A.C.Y. Diabetic Retinopathy: Pathophysiology and Treatments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Altmann, C.; Schmidt, M.H.H. The Role of Microglia in Diabetic Retinopathy: Inflammation, Microvasculature Defects and Neurodegeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vujosevic, S.; Micera, A.; Bini, S.; Berton, M.; Esposito, G.; Midena, E. Aqueous Humor Biomarkers of Muller Cell Activation in Diabetic Eyes. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2015, 56, 3913–3918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Simo-Servat, O.; Hernandez, C.; Simo, R. Usefulness of the vitreous fluid analysis in the translational research of diabetic retinopathy. Mediat. Inflamm. 2012, 2012, 872978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugeswari, P.; Shukla, D.; Rajendran, A.; Kim, R.; Namperumalsamy, P.; Muthukkaruppan, V. Proinflammatory cytokines and angiogenic and anti-angiogenic factors in vitreous of patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy and eales’ disease. Retina 2008, 28, 817–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koleva-Georgieva, D.N.; Sivkova, N.P.; Terzieva, D. Serum inflammatory cytokines IL-1beta, IL-6, TNF-alpha and VEGF have influence on the development of diabetic retinopathy. Folia Med. 2011, 53, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rubsam, A.; Parikh, S.; Fort, P.E. Role of Inflammation in Diabetic Retinopathy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miyamoto, K.; Khosrof, S.; Bursell, S.E.; Rohan, R.; Murata, T.; Clermont, A.C.; Aiello, L.P.; Ogura, Y.; Adamis, A.P. Prevention of leukostasis and vascular leakage in streptozotocin-induced diabetic retinopathy via intercellular adhesion molecule-1 inhibition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 10836–10841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Blum, A.; Pastukh, N.; Socea, D.; Jabaly, H. Levels of adhesion molecules in peripheral blood correlat with stages of diabetic retinopathy and may serve as bio markers for microvascular complications. Cytokine 2018, 106, 76–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, P.; Ge, H.; Liu, H.; Kern, T.S.; Du, L.; Guan, L.; Su, S.; Liu, P. Leukocytes from diabetic patients kill retinal endothelial cells: Effects of berberine. Mol. Vis. 2013, 19, 2092–2105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tyrberg, M.; Lindblad, U.; Melander, A.; Lovestam-Adrian, M.; Ponjavic, V.; Andreasson, S. Electrophysiological studies in newly onset type 2 diabetes without visible vascular retinopathy. Doc. Ophthalmol. 2011, 123, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, M.; Ozawa, Y.; Kurihara, T.; Kubota, S.; Yuki, K.; Noda, K.; Kobayashi, S.; Ishida, S.; Tsubota, K. Neurodegenerative influence of oxidative stress in the retina of a murine model of diabetes. Diabetologia 2010, 53, 971–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sohn, E.H.; van Dijk, H.W.; Jiao, C.; Kok, P.H.; Jeong, W.; Demirkaya, N.; Garmager, A.; Wit, F.; Kucukevcilioglu, M.; van Velthoven, M.E.; et al. Retinal neurodegeneration may precede microvascular changes characteristic of diabetic retinopathy in diabetes mellitus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E2655–E2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Romeo, G.; Liu, W.H.; Asnaghi, V.; Kern, T.S.; Lorenzi, M. Activation of nuclear factor-kappaB induced by diabetes and high glucose regulates a proapoptotic program in retinal pericytes. Diabetes 2002, 51, 2241–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Durham, J.T.; Herman, I.M. Microvascular modifications in diabetic retinopathy. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2011, 11, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Lv, F.L.; Wang, G.H. Effects of HIF-1alpha on diabetic retinopathy angiogenesis and VEGF expression. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 22, 5071–5076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, C.P.; Ferris, F.L., 3rd; Klein, R.E.; Lee, P.P.; Agardh, C.D.; Davis, M.; Dills, D.; Kampik, A.; Pararajasegaram, R.; Verdaguer, J.T.; et al. Proposed international clinical diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema disease severity scales. Ophthalmology 2003, 110, 1677–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.S.; Lee, A.Y.; Baughman, D.; Sim, D.; Akelere, T.; Brand, C.; Crabb, D.P.; Denniston, A.K.; Downey, L.; Fitt, A.; et al. The United Kingdom Diabetic Retinopathy Electronic Medical Record Users Group: Report 3: Baseline Retinopathy and Clinical Features Predict Progression of Diabetic Retinopathy. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 180, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pereira, D.M.; Shah, A.; D’Souza, M.; Simon, P.; George, T.; D’Souza, N.; Suresh, S.; Baliga, M.S. Quality of Life in People with Diabetic Retinopathy: Indian Study. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2017, 11, NC01–NC06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenwick, E.K.; Man, R.E.K.; Gan, A.T.L.; Kumari, N.; Wong, C.; Aravindhan, A.; Gupta, P.; Wang, J.J.; Mitchell, P.; Wong, T.Y.; et al. Beyond vision loss: The independent impact of diabetic retinopathy on vision-related quality of life in a Chinese Singaporean population. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 103, 1314–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihnat, M.A.; Thorpe, J.E.; Kamat, C.D.; Szabo, C.; Green, D.E.; Warnke, L.A.; Lacza, Z.; Cselenyak, A.; Ross, K.; Shakir, S.; et al. Reactive oxygen species mediate a cellular ‘memory’ of high glucose stress signalling. Diabetologia 2007, 50, 1523–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kowluru, R.A.; Mohammad, G. Epigenetics and Mitochondrial Stability in the Metabolic Memory Phenomenon Associated with Continued Progression of Diabetic Retinopathy. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 6655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bernardes, R.; Serranho, P.; Lobo, C. Digital ocular fundus imaging: A review. Ophthalmologica 2011, 226, 161–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shi, L.; Wu, H.; Dong, J.; Jiang, K.; Lu, X.; Shi, J. Telemedicine for detecting diabetic retinopathy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2015, 99, 823–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenner, B.J.; Wong, R.L.M.; Lam, W.C.; Tan, G.S.W.; Cheung, G.C.M. Advances in Retinal Imaging and Applications in Diabetic Retinopathy Screening: A Review. Ophthalmol. Ther. 2018, 7, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, P.S.; Dela Cruz, A.J.; Ledesma, M.G.; van Hemert, J.; Radwan, A.; Cavallerano, J.D.; Aiello, L.M.; Sun, J.K.; Aiello, L.P. Diabetic Retinopathy Severity and Peripheral Lesions Are Associated with Nonperfusion on Ultrawide Field Angiography. Ophthalmology 2015, 122, 2465–2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmer-Galler, I.E.; Zeimer, R. Telemedicine in diabetic retinopathy screening. Int. Ophthalmol. Clin. 2009, 49, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlon, P.H. The English National Screening Programme for diabetic retinopathy 2003–2016. Acta Diabetol. 2017, 54, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wong, R.L.; Tsang, C.W.; Wong, D.S.; McGhee, S.; Lam, C.H.; Lian, J.; Lee, J.W.; Lai, J.S.; Chong, V.; Wong, I.Y. Are we making good use of our public resources? The false-positive rate of screening by fundus photography for diabetic macular oedema. Hong Kong Med. J. 2017, 23, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prescott, G.; Sharp, P.; Goatman, K.; Scotland, G.; Fleming, A.; Philip, S.; Staff, R.; Santiago, C.; Borooah, S.; Broadbent, D.; et al. Improving the cost-effectiveness of photographic screening for diabetic macular oedema: A prospective, multi-centre, UK study. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2014, 98, 1042–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.K.; Radwan, S.H.; Soliman, A.Z.; Lammer, J.; Lin, M.M.; Prager, S.G.; Silva, P.S.; Aiello, L.B.; Aiello, L.P. Neural Retinal Disorganization as a Robust Marker of Visual Acuity in Current and Resolved Diabetic Macular Edema. Diabetes 2015, 64, 2560–2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tan, A.C.S.; Tan, G.S.; Denniston, A.K.; Keane, P.A.; Ang, M.; Milea, D.; Chakravarthy, U.; Cheung, C.M.G. An overview of the clinical applications of optical coherence tomography angiography. Eye 2018, 32, 262–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ting, D.S.W.; Tan, G.S.W.; Agrawal, R.; Yanagi, Y.; Sie, N.M.; Wong, C.W.; San Yeo, I.Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Cheung, C.M.G.; Wong, T.Y. Optical Coherence Tomographic Angiography in Type 2 Diabetes and Diabetic Retinopathy. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017, 135, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samara, W.A.; Shahlaee, A.; Adam, M.K.; Khan, M.A.; Chiang, A.; Maguire, J.I.; Hsu, J.; Ho, A.C. Quantification of Diabetic Macular Ischemia Using Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography and Its Relationship with Visual Acuity. Ophthalmology 2017, 124, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadhwani, M.; Vashist, P.; Singh, S.S.; Gupta, N.; Malhotra, S.; Gupta, A.; Shukla, P.; Bhardwaj, A.; Gupta, V. Diabetic retinopathy screening programme utilising non-mydriatic fundus imaging in slum populations of New Delhi, India. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2018, 23, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gardner, G.G.; Keating, D.; Williamson, T.H.; Elliott, A.T. Automatic detection of diabetic retinopathy using an artificial neural network: A screening tool. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1996, 80, 940–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ting, D.S.W.; Cheung, C.Y.; Lim, G.; Tan, G.S.W.; Quang, N.D.; Gan, A.; Hamzah, H.; Garcia-Franco, R.; San Yeo, I.Y.; Lee, S.Y.; et al. Development and Validation of a Deep Learning System for Diabetic Retinopathy and Related Eye Diseases Using Retinal Images From Multiethnic Populations With Diabetes. JAMA 2017, 318, 2211–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargeya, R.; Leng, T. Automated Identification of Diabetic Retinopathy Using Deep Learning. Ophthalmology 2017, 124, 962–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause, J.; Gulshan, V.; Rahimy, E.; Karth, P.; Widner, K.; Corrado, G.S.; Peng, L.; Webster, D.R. Grader Variability and the Importance of Reference Standards for Evaluating Machine Learning Models for Diabetic Retinopathy. Ophthalmology 2018, 125, 1264–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van der Heijden, A.A.; Abramoff, M.D.; Verbraak, F.; van Hecke, M.V.; Liem, A.; Nijpels, G. Validation of automated screening for referable diabetic retinopathy with the IDx-DR device in the Hoorn Diabetes Care System. Acta Ophthalmol. 2018, 96, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoaku, W.M.; Ghanchi, F.; Bailey, C.; Banerjee, S.; Banerjee, S.; Downey, L.; Gale, R.; Hamilton, R.; Khunti, K.; Posner, E.; et al. Diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular oedema pathways and management: UK Consensus Working Group. Eye 2020, 34, 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlon, P.H.; Stratton, I.M.; Bachmann, M.O.; Jones, C.; Leese, G.P.; Four Nations Diabetic Retinopathy Screening Study Group. Risk of diabetic retinopathy at first screen in children at 12 and 13 years of age. Diabet. Med. 2016, 33, 1655–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Flaxel, C.J.; Adelman, R.A.; Bailey, S.T.; Fawzi, A.; Lim, J.I.; Vemulakonda, G.A.; Ying, G.-s. Diabetic Retinopathy Preferred Practice Pattern®. Ophthalmology 2020, 127, P66–P145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fan, W.; Nittala, M.G.; Velaga, S.B.; Hirano, T.; Wykoff, C.C.; Ip, M.; Lampen, S.I.R.; van Hemert, J.; Fleming, A.; Verhoek, M.; et al. Distribution of Nonperfusion and Neovascularization on Ultrawide-Field Fluorescein Angiography in Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy (RECOVERY Study): Report 1. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 206, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.; Sampani, K.; AbdelAl, O.; Fleming, A.; Cavallerano, J.; Souka, A.; El Baha, S.M.; Silva, P.S.; Sun, J.; Aiello, L.P. Disparity of microaneurysm count between ultrawide field colour imaging and ultrawide field fluorescein angiography in eyes with diabetic retinopathy. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayess, N.; Rahimy, E.; Ying, G.S.; Bagheri, N.; Ho, A.C.; Regillo, C.D.; Vander, J.F.; Hsu, J. Baseline choroidal thickness as a predictor for response to anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy in diabetic macular edema. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2015, 159, 85–91.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Hormel, T.T.; You, Q.; Guo, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, L.; Hwang, T.S.; Jia, Y. Robust non-perfusion area detection in three retinal plexuses using convolutional neural network in OCT angiography. Biomed. Opt. Express 2020, 11, 330–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Saraf, S.S.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, R.K.; Rezaei, K.A. Ultra-Widefield Protocol Enhances Automated Classification of Diabetic Retinopathy Severity with OCT Angiography. Ophthalmol. Retina 2020, 4, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Xu, D.; Wang, F. New insights into diabetic retinopathy by OCT angiography. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2018, 142, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virk, R.; Binns, A.M.; Chambers, R.; Anderson, J. How is the risk of being diagnosed with referable diabetic retinopathy affected by failure to attend diabetes eye screening appointments? Eye 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frith, E.; Loprinzi, P.D. Retinopathy and Mortality. Diabetes Spectr. 2018, 31, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ferris, F.L., 3rd. How effective are treatments for diabetic retinopathy? JAMA 1993, 269, 1290–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, R.; Bonfigli, A.R.; Prattichizzo, F.; La Sala, L.; De Nigris, V.; Ceriello, A. The “Metabolic Memory” Theory and the Early Treatment of Hyperglycemia in Prevention of Diabetic Complications. Nutrients 2017, 9, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. The relationship of glycemic exposure (HbA1c) to the risk of development and progression of retinopathy in the diabetes control and complications trial. Diabetes 1995, 44, 968–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, P.; Hulpus, A.; Idris, I. Short-Term Impact of Bariatric Surgery on Best-Corrected Distance Visual Acuity and Diabetic Retinopathy Progression. Obes. Surg. 2018, 28, 3711–3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, S.A.; Agarwal, G.; Bajaj, H.S.; Ross, S. Targets for Glycemic Control. Can. J. Diabetes 2018, 42 (Suppl. 1), S42–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 38. BMJ 1998, 317, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Do, D.V.; Wang, X.; Vedula, S.S.; Marrone, M.; Sleilati, G.; Hawkins, B.S.; Frank, R.N. Blood pressure control for diabetic retinopathy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 1, CD006127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhou, J.B.; Song, Z.H.; Bai, L.; Zhu, X.R.; Li, H.B.; Yang, J.K. Could Intensive Blood Pressure Control Really Reduce Diabetic Retinopathy Outcomes? Evidence from Meta-Analysis and Trial Sequential Analysis from Randomized Controlled Trials. Diabetes Ther. 2018, 9, 2015–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keech, A.C.; Mitchell, P.; Summanen, P.A.; O’Day, J.; Davis, T.M.; Moffitt, M.S.; Taskinen, M.R.; Simes, R.J.; Tse, D.; Williamson, E.; et al. Effect of fenofibrate on the need for laser treatment for diabetic retinopathy (FIELD study): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2007, 370, 1687–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Group, A.S.; Group, A.E.S.; Chew, E.Y.; Ambrosius, W.T.; Davis, M.D.; Danis, R.P.; Gangaputra, S.; Greven, C.M.; Hubbard, L.; Esser, B.A.; et al. Effects of medical therapies on retinopathy progression in type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhu, W.; Wu, Y.; Meng, Y.F.; Xing, Q.; Tao, J.J.; Lu, J. Association of obesity and risk of diabetic retinopathy in diabetes patients: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Medicine 2018, 97, e11807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Chen, Y.; Yang, W.; Gao, X.; Han, X.; Ji, L. The association of smoking and risk of diabetic retinopathy in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis. Endocrine 2018, 62, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, F.; Brown, A.; Cho, N.H.; Dahlquist, G.; Dodd, S.; Dunning, T.; Hirst, M.; Hwang, C.; Magliano, D.; Patterson, C.; et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Sixth Edition; International Diabetes Federation. 2013. Available online: http://dro.deakin.edu.au/view/DU:30060687 (accessed on 13 March 2021).

- Rasmussen, K.L.; Laugesen, C.S.; Ringholm, L.; Vestgaard, M.; Damm, P.; Mathiesen, E.R. Progression of diabetic retinopathy during pregnancy in women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 2010, 53, 1076–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, B.E.; Moss, S.E.; Klein, R. Effect of pregnancy on progression of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care 1990, 13, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, J.L.; Hodgson, L.A.; Lim, L.L.; Al-Qureshi, S. Diabetic retinopathy in pregnancy: A review. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2016, 44, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. Effect of pregnancy on microvascular complications in the diabetes control and complications trial. Diabetes Care 2000, 23, 1084–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Helen, C.C.; Tajunisah, I.; Reddy, S.C. Adverse outcomes in Type I diabetic pregnant women with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Int J. Ophthalmol. 2011, 4, 443–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, W.C.; Lim, L.T.; Quinn, M.J.; Knox, F.A.; McCance, D.; Best, R.M. Management and outcome of sight-threatening diabetic retinopathy in pregnancy. Eye 2004, 18, 826–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fazelat, A.; Lashkari, K. Off-label use of intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide for diabetic macular edema in a pregnant patient. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2011, 5, 439–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yoo, R.; Kim, H.C.; Chung, H. Dexamethasone intravitreal implant for diabetic macular edema in a pregnant patient. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 9, 1524–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concillado, M.; Lund-Andersen, H.; Mathiesen, E.R.; Larsen, M. Dexamethasone Intravitreal Implant for Diabetic Macular Edema During Pregnancy. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 165, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamilian, M.; Mirhosseini, N.; Eslahi, M.; Bahmani, F.; Shokrpour, M.; Chamani, M.; Asemi, Z. The effects of magnesium-zinc-calcium-vitamin D co-supplementation on biomarkers of inflammation, oxidative stress and pregnancy outcomes in gestational diabetes. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019, 19, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tham, Y.C.; Liu, L.; Rim, T.H.; Zhang, L.; Majithia, S.; Chee, M.L.; Tan, N.Y.Q.; Wong, K.H.; Ting, D.S.W.; Sabanayagam, C.; et al. Association of Cataract Surgery with Risk of Diabetic Retinopathy Among Asian Participants in the Singapore Epidemiology of Eye Diseases Study. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e208035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denniston, A.K.; Chakravarthy, U.; Zhu, H.; Lee, A.Y.; Crabb, D.P.; Tufail, A.; Bailey, C.; Akerele, T.; Al-Husainy, S.; Brand, C.; et al. The UK Diabetic Retinopathy Electronic Medical Record (UK DR EMR) Users Group, Report 2: Real-world data for the impact of cataract surgery on diabetic macular oedema. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 101, 1673–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hovland, P.G. Diabetic Retinopathy Severity and Cataract Surgery: When Less Is More. Ophthalmol. Retina 2020, 4, 349–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasongko, M.B.; Rogers, S.; Constantinou, M.; Sandhu, S.S.; Wickremasinghe, S.S.; Al-Qureshi, S.; Lim, L.L. Diabetic retinopathy progression 6 months post-cataract surgery with intravitreous bevacizumab vs triamcinolone: A secondary analysis of the DiMECAT trial. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.Q.; Cheng, J.W. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Clinical Outcomes of Intravitreal Anti-VEGF Agent Treatment Immediately after Cataract Surgery for Patients with Diabetic Retinopathy. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 2019, 2648267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Feng, Y.; Zhu, S.; Skiadaresi, E.; McAlinden, C.; Tu, R.; Gao, R.; Stephens, J.W.; Wang, Q.; Huang, J. Phacoemulsification cataract surgery with prophylactic intravitreal bevacizumab for patients with coexisting diabetic retinopathy: A Meta-Analysis. Retina 2019, 39, 1720–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group. Preliminary report on effects of photocoagulation therapy. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1976, 81, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group. Photocoagulation treatment of proliferative diabetic retinopathy: Relationship of adverse treatment effects to retinopathy severity. Diabetic retinopathy study report no. 5. Dev. Ophthalmol. 1981, 2, 248–261. [Google Scholar]

- Funatsu, H.; Yamashita, H.; Noma, H.; Mimura, T.; Yamashita, T.; Hori, S. Increased levels of vascular endothelial growth factor and interleukin-6 in the aqueous humor of diabetics with macular edema. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2002, 133, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, L.P.; Avery, R.L.; Arrigg, P.G.; Keyt, B.A.; Jampel, H.D.; Shah, S.T.; Pasquale, L.R.; Thieme, H.; Iwamoto, M.A.; Park, J.E.; et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor in ocular fluid of patients with diabetic retinopathy and other retinal disorders. N. Engl. J. Med. 1994, 331, 1480–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.G.; Glassman, A.R.; Jampol, L.M.; Inusah, S.; Aiello, L.P.; Antoszyk, A.N.; Baker, C.W.; Berger, B.B.; Bressler, N.M.; Browning, D.; et al. Panretinal Photocoagulation vs Intravitreous Ranibizumab for Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2015, 314, 2137–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sivaprasad, S.; Prevost, A.T.; Vasconcelos, J.C.; Riddell, A.; Murphy, C.; Kelly, J.; Bainbridge, J.; Tudor-Edwards, R.; Hopkins, D.; Hykin, P.; et al. Clinical efficacy of intravitreal aflibercept versus panretinal photocoagulation for best corrected visual acuity in patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy at 52 weeks (CLARITY): A multicentre, single-blinded, randomised, controlled, phase 2b, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2017, 389, 2193–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beaulieu, W.T.; Bressler, N.M.; Melia, M.; Owsley, C.; Mein, C.E.; Gross, J.G.; Jampol, L.M.; Glassman, A.R.; Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research, N. Panretinal Photocoagulation Versus Ranibizumab for Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy: Patient-Centered Outcomes from a Randomized Clinical Trial. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 170, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Figueira, J.; Fletcher, E.; Massin, P.; Silva, R.; Bandello, F.; Midena, E.; Varano, M.; Sivaprasad, S.; Eleftheriadis, H.; Menon, G.; et al. Ranibizumab Plus Panretinal Photocoagulation versus Panretinal Photocoagulation Alone for High-Risk Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy (PROTEUS Study). Ophthalmology 2018, 125, 691–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassman, A.R. Results of a Randomized Clinical Trial of Aflibercept vs Panretinal Photocoagulation for Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy: Is It Time to Retire Your Laser? JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017, 135, 685–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, J.G.; Glassman, A.R.; Liu, D.; Sun, J.K.; Antoszyk, A.N.; Baker, C.W.; Bressler, N.M.; Elman, M.J.; Ferris, F.L., 3rd; Gardner, T.W.; et al. Five-Year Outcomes of Panretinal Photocoagulation vs Intravitreous Ranibizumab for Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018, 136, 1138–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Obeid, A.; Gao, X.; Ali, F.S.; Talcott, K.E.; Aderman, C.M.; Hyman, L.; Ho, A.C.; Hsu, J. Loss to Follow-Up in Patients with Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy after Panretinal Photocoagulation or Intravitreal Anti-VEGF Injections. Ophthalmology 2018, 125, 1386–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeid, A.; Su, D.; Patel, S.N.; Uhr, J.H.; Borkar, D.; Gao, X.; Fineman, M.S.; Regillo, C.D.; Maguire, J.I.; Garg, S.J.; et al. Outcomes of Eyes Lost to Follow-up with Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy That Received Panretinal Photocoagulation versus Intravitreal Anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor. Ophthalmology 2019, 126, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jampol, L.M.; Glassman, A.R.; Sun, J. Evaluation and Care of Patients with Diabetic Retinopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1629–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.K.; Glassman, A.R.; Beaulieu, W.T.; Stockdale, C.R.; Bressler, N.M.; Flaxel, C.; Gross, J.G.; Shami, M.; Jampol, L.M.; Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network. Rationale and Application of the Protocol S Anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Algorithm for Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy. Ophthalmology 2019, 126, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group. Photocoagulation for diabetic macular edema. Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study report number 1. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1985, 103, 1796–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relhan, N.; Flynn, H.W., Jr. The Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study historical review and relevance to today’s management of diabetic macular edema. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2017, 28, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network. A randomized trial comparing intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide and focal/grid photocoagulation for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology 2008, 115, 1447–1459.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network; Elman, M.J.; Aiello, L.P.; Beck, R.W.; Bressler, N.M.; Bressler, S.B.; Edwards, A.R.; Ferris, F.L., 3rd; Friedman, S.M.; Glassman, A.R.; et al. Randomized trial evaluating ranibizumab plus prompt or deferred laser or triamcinolone plus prompt laser for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology 2010, 117, 1064–1077.e35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Michaelides, M.; Kaines, A.; Hamilton, R.D.; Fraser-Bell, S.; Rajendram, R.; Quhill, F.; Boos, C.J.; Xing, W.; Egan, C.; Peto, T.; et al. A prospective randomized trial of intravitreal bevacizumab or laser therapy in the management of diabetic macular edema (BOLT study) 12-month data: Report 2. Ophthalmology 2010, 117, 1078–1086.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, P.; Bandello, F.; Schmidt-Erfurth, U.; Lang, G.E.; Massin, P.; Schlingemann, R.O.; Sutter, F.; Simader, C.; Burian, G.; Gerstner, O.; et al. The RESTORE study: Ranibizumab monotherapy or combined with laser versus laser monotherapy for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology 2011, 118, 615–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nguyen, Q.D.; Brown, D.M.; Marcus, D.M.; Boyer, D.S.; Patel, S.; Feiner, L.; Gibson, A.; Sy, J.; Rundle, A.C.; Hopkins, J.J.; et al. Ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema: Results from 2 phase III randomized trials: RISE and RIDE. Ophthalmology 2012, 119, 789–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, D.M.; Schmidt-Erfurth, U.; Do, D.V.; Holz, F.G.; Boyer, D.S.; Midena, E.; Heier, J.S.; Terasaki, H.; Kaiser, P.K.; Marcus, D.M.; et al. Intravitreal Aflibercept for Diabetic Macular Edema: 100-Week Results from the VISTA and VIVID Studies. Ophthalmology 2015, 122, 2044–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elman, M.J.; Bressler, N.M.; Qin, H.; Beck, R.W.; Ferris, F.L., 3rd; Friedman, S.M.; Glassman, A.R.; Scott, I.U.; Stockdale, C.R.; Sun, J.K.; et al. Expanded 2-year follow-up of ranibizumab plus prompt or deferred laser or triamcinolone plus prompt laser for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology 2011, 118, 609–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bressler, N.M.; Beaulieu, W.T.; Glassman, A.R.; Blinder, K.J.; Bressler, S.B.; Jampol, L.M.; Melia, M.; Wells, J.A., 3rd; Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research, N. Persistent Macular Thickening Following Intravitreous Aflibercept, Bevacizumab, or Ranibizumab for Central-Involved Diabetic Macular Edema With Vision Impairment: A Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018, 136, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Glassman, A.R.; Wells, J.A., 3rd; Josic, K.; Maguire, M.G.; Antoszyk, A.N.; Baker, C.; Beaulieu, W.T.; Elman, M.J.; Jampol, L.M.; Sun, J.K. Five-Year Outcomes after Initial Aflibercept, Bevacizumab, or Ranibizumab Treatment for Diabetic Macular Edema (Protocol T Extension Study). Ophthalmology 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maturi, R.K.; Pollack, A.; Uy, H.S.; Varano, M.; Gomes, A.M.; Li, X.Y.; Cui, H.; Lou, J.; Hashad, Y.; Whitcup, S.M.; et al. Intraocular Pressure in Patients with Diabetic Macular Edema Treated with Dexamethasone Intravitreal Implant in the 3-Year Mead Study. Retina 2016, 36, 1143–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campochiaro, P.A.; Brown, D.M.; Pearson, A.; Chen, S.; Boyer, D.; Ruiz-Moreno, J.; Garretson, B.; Gupta, A.; Hariprasad, S.M.; Bailey, C.; et al. Sustained delivery fluocinolone acetonide vitreous inserts provide benefit for at least 3 years in patients with diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology 2012, 119, 2125–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt-Erfurth, U.; Garcia-Arumi, J.; Bandello, F.; Berg, K.; Chakravarthy, U.; Gerendas, B.S.; Jonas, J.; Larsen, M.; Tadayoni, R.; Loewenstein, A. Guidelines for the Management of Diabetic Macular Edema by the European Society of Retina Specialists (EURETINA). Ophthalmologica 2017, 237, 185–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suganya, N.; Bhakkiyalakshmi, E.; Sarada, D.V.; Ramkumar, K.M. Reversibility of endothelial dysfunction in diabetes: Role of polyphenols. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 116, 223–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lafuente, M.; Ortin, L.; Argente, M.; Guindo, J.L.; Lopez-Bernal, M.D.; Lopez-Roman, F.J.; Domingo, J.C.; Lajara, J. Three-Year Outcomes in a Randomized Single-Blind Controlled Trial of Intravitreal Ranibizumab and Oral Supplementation with Docosahexaenoic Acid and Antioxidants for Diabetic Macular Edema. Retina 2019, 39, 1083–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossino, M.G.; Casini, G. Nutraceuticals for the Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy. Nutrients 2019, 11, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Safi, S.Z.; Qvist, R.; Kumar, S.; Batumalaie, K.; Ismail, I.S. Molecular mechanisms of diabetic retinopathy, general preventive strategies, and novel therapeutic targets. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 801269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, C.; Miao, X.; Li, F.; Wang, S.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Sun, J. Oxidative Stress-Related Mechanisms and Antioxidant Therapy in Diabetic Retinopathy. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2017, 2017, 9702820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles-Rivera, R.R.; Castellanos-Gonzalez, J.A.; Olvera-Montano, C.; Flores-Martin, R.A.; Lopez-Contreras, A.K.; Arevalo-Simental, D.E.; Cardona-Munoz, E.G.; Roman-Pintos, L.M.; Rodriguez-Carrizalez, A.D. Adjuvant Therapies in Diabetic Retinopathy as an Early Approach to Delay Its Progression: The Importance of Oxidative Stress and Inflammation. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2020, 2020, 3096470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group. A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with vitamins C and E and beta carotene for age-related cataract and vision loss: AREDS report no. 9. Arch. Ophthalmol 2001, 119, 1439–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinazo-Duran, M.D.; Gallego-Pinazo, R.; Garcia-Medina, J.J.; Zanon-Moreno, V.; Nucci, C.; Dolz-Marco, R.; Martinez-Castillo, S.; Galbis-Estrada, C.; Marco-Ramirez, C.; Lopez-Galvez, M.I.; et al. Oxidative stress and its downstream signaling in aging eyes. Clin. Interv. Aging 2014, 9, 637–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Balasaheb, S.; Pal, D. Free radicals, natural antioxidants, and their reaction mechanisms. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 27986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Suksomboon, N.; Poolsup, N.; Juanak, N. Effects of coenzyme Q10 supplementation on metabolic profile in diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2015, 40, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agbor, G.A.; Vinson, J.A.; Patel, S.; Patel, K.; Scarpati, J.; Shiner, D.; Wardrop, F.; Tompkins, T.A. Effect of selenium- and glutathione-enriched yeast supplementation on a combined atherosclerosis and diabetes hamster model. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 8731–8736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajith, T.A. Alpha-lipoic acid: A possible pharmacological agent for treating dry eye disease and retinopathy in diabetes. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2020, 47, 1883–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eynard, A.R.; Repossi, G. Role of omega3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in diabetic retinopathy: A morphological and metabolically cross talk among blood retina barriers damage, autoimmunity and chronic inflammation. Lipids Health Dis. 2019, 18, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, W.; Wu, S.; Jin, J.; Li, W.; Wang, N. Calcium dobesilate for diabetic retinopathy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. China Life Sci. 2015, 58, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garcia-Medina, J.J.; Rubio-Velazquez, E.; Lopez-Bernal, M.D.; Cobo-Martinez, A.; Zanon-Moreno, V.; Pinazo-Duran, M.D.; Del-Rio-Vellosillo, M. Glaucoma and Antioxidants: Review and Update. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, M.; Senni, C.; Bernabei, F.; Cicero, A.F.G.; Vagge, A.; Maestri, A.; Scorcia, V.; Giannaccare, G. The Role of Nutrition and Nutritional Supplements in Ocular Surface Diseases. Nutrients 2020, 12, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chous, A.P.; Richer, S.P.; Gerson, J.D.; Kowluru, R.A. The Diabetes Visual Function Supplement Study (DiVFuSS). Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 100, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sanz-Gonzalez, S.M.; Garcia-Medina, J.J.; Zanon-Moreno, V.; Lopez-Galvez, M.I.; Galarreta-Mira, D.; Duarte, L.; Valero-Vello, M.; Ramirez, A.I.; Arevalo, J.F.; Pinazo-Duran, M.D.; et al. Clinical and Molecular-Genetic Insights into the Role of Oxidative Stress in Diabetic Retinopathy: Antioxidant Strategies and Future Avenues. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, S.W.; Shin, Y.U.; Cho, H.; Bae, S.H.; Kim, H.K.; for the Mogen Study Group. Effect of grape seed proanthocyanidin extract on hard exudates in patients with non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Medicine 2019, 98, e15515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sepahi, S.; Mohajeri, S.A.; Hosseini, S.M.; Khodaverdi, E.; Shoeibi, N.; Namdari, M.; Tabassi, S.A.S. Effects of Crocin on Diabetic Maculopathy: A Placebo-Controlled Randomized Clinical Trial. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 190, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.C.; Wu, C.R.; Wang, Z.L.; Wang, L.Y.; Han, Y.; Sun, S.L.; Li, Q.S.; Ma, L. Effect of lutein supplementation on visual function in nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 26, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafuente, M.; Ortin, L.; Argente, M.; Guindo, J.L.; Lopez-Bernal, M.D.; Lopez-Roman, F.J.; Garcia, M.J.; Domingo, J.C.; Lajara, J. Combined intravitreal ranibizumab and oral supplementation with docosahexaenoic acid and antioxidants for diabetic macular edema: Two-Year Randomized Single-Blind Controlled Trial Results. Retina 2017, 37, 1277–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Carrizalez, A.D.; Castellanos-Gonzalez, J.A.; Martinez-Romero, E.C.; Miller-Arrevillaga, G.; Pacheco-Moises, F.P.; Roman-Pintos, L.M.; Miranda-Diaz, A.G. The effect of ubiquinone and combined antioxidant therapy on oxidative stress markers in non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy: A phase IIa, randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled study. Redox Rep. 2016, 21, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roig-Revert, M.J.; Lleo-Perez, A.; Zanon-Moreno, V.; Vivar-Llopis, B.; Marin-Montiel, J.; Dolz-Marco, R.; Alonso-Munoz, L.; Albert-Fort, M.; Lopez-Galvez, M.I.; Galarreta-Mira, D.; et al. Enhanced Oxidative Stress and Other Potential Biomarkers for Retinopathy in Type 2 Diabetics: Beneficial Effects of the Nutraceutic Supplements. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 408180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domanico, D.; Fragiotta, S.; Cutini, A.; Carnevale, C.; Zompatori, L.; Vingolo, E.M. Circulating levels of reactive oxygen species in patients with nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy and the influence of antioxidant supplementation: 6-month follow-up. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2015, 63, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, K.; Shimada, A.; Miyaki, K.; Hirakata, A.; Matsuoka, K.; Omae, K.; Takei, I. Long-term effects of goshajinkigan in prevention of diabetic complications: A randomized open-labeled clinical trial. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2014, 2014, 128726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haritoglou, C.; Gerss, J.; Hammes, H.P.; Kampik, A.; Ulbig, M.W.; RETIPON Study Group. Alpha-lipoic acid for the prevention of diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmologica 2011, 226, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Garcia-Medina, J.J.; Pinazo-Duran, M.D.; Garcia-Medina, M.; Zanon-Moreno, V.; Pons-Vazquez, S. A 5-year follow-up of antioxidant supplementation in type 2 diabetic retinopathy. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2011, 21, 637–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forte, R.; Cennamo, G.; Finelli, M.L.; Bonavolonta, P.; de Crecchio, G.; Greco, G.M. Combination of flavonoids with Centella asiatica and Melilotus for diabetic cystoid macular edema without macular thickening. J. Ocul Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 27, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bursell, S.E.; Clermont, A.C.; Aiello, L.P.; Aiello, L.M.; Schlossman, D.K.; Feener, E.P.; Laffel, L.; King, G.L. High-dose vitamin E supplementation normalizes retinal blood flow and creatinine clearance in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 1999, 22, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, C. Assessing Vitamins, Minerals and Supplements Marketed to Children in Canada. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jafari, S.M.; McClements, D.J. Nanotechnology Approaches for Increasing Nutrient Bioavailability. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2017, 81, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapetanovic, I.M.; Muzzio, M.; Huang, Z.; Thompson, T.N.; McCormick, D.L. Pharmacokinetics, oral bioavailability, and metabolic profile of resveratrol and its dimethylether analog, pterostilbene, in rats. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2011, 68, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aiello, L.P.; Odia, I.; Glassman, A.R.; Melia, M.; Jampol, L.M.; Bressler, N.M.; Kiss, S.; Silva, P.S.; Wykoff, C.C.; Sun, J.K.; et al. Comparison of Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Standard 7-Field Imaging With Ultrawide-Field Imaging for Determining Severity of Diabetic Retinopathy. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019, 137, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spaide, R.F.; Klancnik, J.M., Jr.; Cooney, M.J. Retinal vascular layers in macular telangiectasia type 2 imaged by optical coherence tomographic angiography. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015, 133, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spaide, R.F.; Klancnik, J.M., Jr.; Cooney, M.J. Retinal vascular layers imaged by fluorescein angiography and optical coherence tomography angiography. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015, 133, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, P.D.; Sim, D.A.; Keane, P.A.; Cardoso, J.; Agrawal, R.; Tufail, A.; Egan, C.A. The Evaluation of Diabetic Macular Ischemia Using Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2016, 57, 626–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schmidt-Erfurth, U.; Sadeghipour, A.; Gerendas, B.S.; Waldstein, S.M.; Bogunovic, H. Artificial intelligence in retina. Prog. Retin Eye Res. 2018, 67, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, D.S.W.; Pasquale, L.R.; Peng, L.; Campbell, J.P.; Lee, A.Y.; Raman, R.; Tan, G.S.W.; Schmetterer, L.; Keane, P.A.; Wong, T.Y. Artificial intelligence and deep learning in ophthalmology. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 103, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Whitehead, M.; Wickremasinghe, S.; Osborne, A.; Van Wijngaarden, P.; Martin, K.R. Diabetic retinopathy: A complex pathophysiology requiring novel therapeutic strategies. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2018, 18, 1257–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disease | Ophthalmoscopy Findings |

| No apparent DR | No ocular findings |

| NPDR | No NV |

| Mild | Microaneurysms only |

| Moderate | Microaneurysms + blot haemorrhages, hard exudates, cotton wool spots (but less than in severe NPDR) |

| Severe | Intraretinal haemorrhages (≥20 in each quadrant) Definite venous beading (in two quadrants) Intraretinal microvascular abnormalities (IRMA) (in one quadrant) No signs of proliferative retinopathy |

| PDR | Neovascularisation or vitreous/preretinal haemorrhage/tractional retinal detachment |

| DME = retinal thickening of hard exudates in the posterior pole | |

| Mild | Some retinal thickening or hard exudates in the posterior pole but distant from the centre of the macula |

| Moderate | Retinal thickening or hard exudates approaching the centre of the macula but not involving the fovea |

| Severe | Retinal thickening or hard exudates involving the centre of the macula |

| No DR | NPDR | PDR | DME | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild | Moderate | Severe | Non-Centre Involving | Centre | |||

| PDR progression risk within 1 year/3 years | 5%/14% | 12–27%/30.48% | 52%/71% | ||||

| Referral to ophthalmologist | Not required | Not required | Required | Required | Required | Recommended if laser sources available * | Required |

| Treatment | Observation | Observation/PRP | PRP | Anti-VEGF/PRP/VPP | Laser: Focal/Grid | Anti-VEGF | |

| Antioxidants role | Potentially indicated | Worthwhile? | Potentially indicated | ||||

| Follow-up | 1–2 years | 6–12 months/1–2 years * | 3–6 months/6–12 months * | <3 months | <1 month If stabilised: 6 to 12 months | 3 months | 1 month |

| Author/Year/Country/Reference | Study | Study Focus | Antioxidant Composition per Pill | Trade Name Dose | N per Group: Supplemented (S) and Control (C). Mean Age (Years) | Follow-Up Time in Months | Clinical Findings | Biochemical Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sanz-González 2020 Spain [145] | Case-control study | Type 2 DM with and without DR | Oil as a source of PUFAs: 400 mg Omega-3 (ω3): DHA 140 mg Vitamin C 80 mg Vitamin D 5 µg Vitamin B 20.1 mg Vitamin E 12 mg Lutein 6 mg Zeaxanthin 0.3 mg Glutathione 1 mg Hydroxytyrosol 0.75 mg Zinc 7.5 mg Copper 1 mg Selenium 55 µg Manganese 2 mg Dosage = 1 tablet/day: Supplement or Placebo | Nutrof Omega® (Thea SA, (Barcelona, Spain) | N = 365 225 T2DM −With DR: 100 −Without DR: 125 140 healthy controls Mean Age: T2DM: 60 Controls: 55 | 38 | The placebo group was more representative in subjects with T2DM in whom DR progressed. NS differences in IOP and CMT | The A/ω3 regime significantly reduced the pro-oxidants (p < 0.05) and augmented the antioxidants (p < 0.05). |

| Moon 2019 Korea [146] | Randomised (1:2:2), double-blind controlled trial | Type 2 DM with NPDR 40–80 y.o. AV > 0.5 Without laser or intravitreal therapy or intraocular surgery in the previous 6 months | S group 1: 50 mg—Grape seed proanthocyanidins extracts (GSPE) (Vitis vinifera extract) S group 2: 250 mg of calcium dobesilate (CD) C group. | GSPE: Entelon (Hanlim Pharm, Seoul, South Korea) CD: Doxium (Ilsung Pharm, Seoul, South Korea). | N = 86 3 tablets 3 times daily S1: GSPE (150 mg/day): 32 S2: CD (750 mg/day): 35 Placebo: 19 | 12 | Hard exudates severity improvement: higher in GSPE (43.9%) vs. CD (14.29%) and vs. placebo (8%) (0.0007) NS differences between OCT parameters (CMT, TVM) GSPE TVM significantly decreases with respect to baseline. | NS differences with regard to vital signs and laboratory results between groups. |

| Lafuente 2019 Spain [129] | Randomised Single-Blind Controlled Trial | T2DM adults with decreased vision due to central-involved DME | Omega-3 Fatty Acids DHA 350 mg EPA 42.5 mg DPA 30 mg Vitamin C 26.7 mg Vitamin E 4 mg B vitamins 7.3 mg Lutein 3 mg Zeaxanthin 0.3 mg Glutathione 2 mg Zinc 1.66 mg Copper 0.16 mg Selenium 9.16 µg Manganese 0.33 mg | Brudyretina® 1.5 g (Brudy Lab S.L Barcelona, Spain) 3 capsules of 1.5 g once daily | N = 55 (69 eyes) S + Ranibizumab * n = 26 (31 eyes) C: Only Ranibizumab * n = 29 (38 eyes) All patients with four monthly doses of ranibizumab followed by pro re nata basis. | 36 | VA: NS difference in ETDRS letters. Gains of >5 and >10 letters significantly higher in S group. CMT: Significant decrease in S group vs. C group (275 ±50 µm vs. 310 ± 97 µm) Number of Ranibizumab injections: NS differences between groups. | Significant differences in HbA1c, plasma total antioxidant capacity values, erythrocyte DHA content and IL-6 levels in favour of S group. |

| Sepahi 2018 Iran [147] | Phase 2 randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. | Refractory to conventional DME therapy in type 1 or 2 diabetes Refractory therapy including: macular photocoagulation and intravitreal injection of bevacizumab with or without triamcinolone | S1: Crocin tablet 15 mg S2: Crocin tablet 5 mg | Crocin tablet Pharmaceutical laboratory of School of Pharmacy, Mashhad University of Medical Science, Mashhad, Iran 1 tablet per day (15 mg, 5 mg or placebo) | N = 60 patients (101 eyes) S 1: 20 (33 eyes) S 2: 20 (34 eyes) C: 20 (34 eyes) Age: 41–82 | Supplementation: 3 Follow-up: 6 | VA: LogMAR: S1 significantly improved compared to S2 (p < 0.05) and to C (p = 0.02). CMT: S1 significantly improved compared to S2 (p < 0.05) and to C (p = 0.005). S2 NS improvement compared to C. | HbA1c and FBS: S1 and S2 significantly better than C. |

| Zhang 2017 China [148] | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | NPDR mild or moderate stages Type 2 diabetes Exclusion criteria: DME, other eye disorders other than mild or moderate NPDR | Lutein 10 mg Placebo capsule | Lutein 10 mg 1 capsule once a day (1 capsule of placebo once a day if C) Lutein Pharmaceutical Co Ltd. (Guangzhou, China) | N = 30 patients S: 15 C: 15 Mean age: 60.2., SD: 10.3 | 9 | VA: slight NS improvement in S (p = 0.11) Contrast sensitivity: S: significant increase in 3 cycles/° by 0.16 (p = 0.02) ANOVA analysis showed differences between S and C. NS in 6.12 and 36 cycles/°. Glare sensitivity: NS differences. | |

| Lafuente 2017 Spain [149] | Randomised Single-Blind Controlled Trial | Type 2 diabetes adults with decreased vision due to central-involved DME. | Omega-3 Fatty Acids DHA 350 mg EPA 42.5 mg DPA 30 mg Vitamin C 26.7 mg Vitamin E 4 mg B vitamins 7.3 mg Lutein 3 mg Zeaxanthin 0.3 mg Glutathione 2 mg Zinc 1.66 mg Copper 0.16 mg Selenium 9.16 µg Manganese 0.33 mg | Brudyretina® 1.5 g (Brudy Lab S.L Barcelona, Spain) 3 capsules of 1.5 g once daily | N = 76 eyes S + Ranibizumab * n = 34 C: Only Ranibizumab * n = 42 All patients with four monthly doses of ranibizumab followed by pro re nata basis. | 24 | VA: NS difference in ETDRS letters. Gains of >5 letters significantly higher in S group (p = 0.044), NS for gains of >10 letters. CMT: Significant decrease in S group (95% CI 7.20–97.656; p = 0.024) Number of Ranibizumab injections: NS differences between groups. | Significant increase in TAC (total antioxidative capacity) in S group (p < 0.001) Significant reduction in the erythrocyte membrane content of ω-6 arachidonic acid in the S group (p < 0.05) NS differences in HbA1c levels |

| Rodriguez-Carrizalez 2016 Mexico [150] | Randomised, controlled, phase IIa clinical trial | T2DM with NPDR, but without DME | S1: Ubiquinone 400 mg Dosage 1 tablet/day S2: Vitamin C 180 mg Vitamin E 30 mg Lutein 10 mg Astaxanthin 4 mg Zeaxanthin 1 mg Zinc 20 mg Dosage 1 tablet/day C: Placebo tablet | Noncommercialised supplement | N = 60 patients S1: N = 20 S2: N = 20 C: N = 20 Mean age S1: 58.5 ± 1.9 S2: 62.1 ±1.1 C: 57.8± 1.9 | 6 | VA: NS changes | S1 and S2 Significant decrease in lipid peroxidation products, NO metabolites, catalase and glutathione peroxidase (p < 0.0001) Increased TAC (p < 0.0001) Vs. C group NS changes in HbA1c%, cholesterol and triglyceride levels between groups |

| Chous 2016 USA [144] | Randomised controlled clinical trial | T1 or T2DM without DR or with mild-to-moderate NPDR without CSME | S: Vitamin C 60 mg Vitamin D3 50 mg Vitamin E 40 mg α-Lipoic acid 150 mg Coenzyme Q10 20 mg Omega-3 Fatty Acids EPA 128 mg DHA 96 mg Zeaxanthin 8 mg Lutein 4 mg Zinc oxide 15 mg Benfotiamine N-acetyl cysteine Grape seed extract Resveratrol Turmeric root Extract green tea leaf Pycnogenol (Not specified mg) Dosage = 2 tablets/day C: Placebo tablet | DiVFuSS® (ZeaVision, LLC, Chesterfield, MO, USA) | N = 67 patients S: N = 39 C: N = 28 Mean age S: 53.5 ± 14.6 C: 59.7 ± 10.3 | 6 | VA: NS changes CMT: NS changes RNFL thickness: NS changes Contrast sensitivity, colour error Score, visual field mean sensitivity and MPOD: significant 27% improvement in the S group vs. 2% in the C group. (p values ranging from 0.008 to <0.0001). MPOD (macular pigment optical density) | NS changes in HbA1c, total cholesterol or TNF-α between the groups |

| Roig-Revert 2015 Spain [151] | Randomised, prospective, multicentre study | T2DM Group 1: NPDR ± DME Group 2: Diabetic patients without DR Healthy subjects | S: Vitamin C 80 mg Vitamin D 5 µg Vitamin B 20.1 mg Vitamin E 12 mg Omega-3: DHA 140 mg Lutein 6 mg Zeaxanthin 0.3 mg Glutathione 1 mg Hydroxytyrosol 0.75 mg Zinc 7.5 mg Copper 1 mg Selenium 55 µg Manganese 2 mg Dosage = 1 tablet/day C: no placebo capsule | Nutrof Omega® (Thea SA, (Barcelona, Spain) | N = 208 patients Group 1 DM DR+ (N = 62) S (n = not specified) C (n = not specified) Group 2 DM DR- (N = 68) S (N = not specified) C (n = not specified) Group 3 Healthy subjects (N = 78) S (n = not specified) C (n = not specified) Mean age DM DR+ 65.1 ± 8.6 DM DR− 62.3 ± 10.1 | 18 | Group 1 DM DR + DR progression: S: 61% C: 91% Group 2 DM DR- DR onset: S: 9% C: 35% RNFLT of the LE was significantly reduced in the S group (p = 0.01) | Significant reduction in TAS in supplemented DMDR+ (p = 0.020) Plasma lipid peroxidation by-products significantly decreased in the DMDR+ supplemented group. NS in terms of HbA1c, HDL/LDL cholesterol and triglycerides. |

| Domanico 2015 Italy [152] | Randomised prospective study | T2DM showing mild-to-moderate NPDR, without CSME or CVRF | Vitamin E 30 mg Pycnogenol 50 mg Coenzyme Q10 20 mg Dosage = 1 tablet/day C: no placebo capsule | Diaberet® (Visufarma, Rome, Italy) | N = 68 patients (eyes) S: N = 34 C: N = 34 Mean age S: 58.29 ± 12.37 C: 62.29 ± 11.54 | 6 | CMT: significant reduction on the S group (p < 0.01) (–15.44 µm, [95% CI: 3.26, 27.61]) | Significant reduction of ROS levels (free oxygen radical test) in the S group (p < 0.001) |

| Watanabe 2014 Japan [153] | Randomised, prospective study | T2DM patients without DR | 2.5 g of goshajinkigan extract three times a day, which included: 4.5 g of the compound extracts of 10 herbal medicines: Rehmanniae radix (5 g), Achyranthis radix (3 g), Corni fructus (3 g), Dioscoreae rhizoma (3 g), Hoelen (3 g), Plantaginis semen (3 g), Alismatis rhizoma (3 g), Moutan cortex (3 g), Cinnamomi cortex (1 g) and heat-processed Aconiti radix (1 g) | TJ-107; Tsumura Co., Tokyo, Japan | N = 116 patients S: N = 74 C: N = 42 Mean age S: 59.4 ± 7.8 C: 60.9 ± 7.4 | 60 | Progression of retinopathy: No differences between S and C. A total of 25 patients had DR at the end of the study. 17.9% in Goshajinkigan group 20.0% in control group p = 0.816 | Glycated haemoglobin significantly decreased in the S group at the 60th month. Fasting glucose significantly decreased in the S group beginning at the 36th month. No differences between insulin or oral antidiabetic medications. |

| Haritoglou 2011 Germany [154] | Randomised, prospective, multicentre, study | T2DM showing mild-to-moderate NPDR in at least one eye | S: α-lipoic acid (ALA) 600 mg Dosage 1 tablet/day C: placebo tablet | Noncommercialised supplement | N: = 399 patients S: = 196 C: = 203 Mean age S 58.0 C 57.9 | 24 | CSME debut during follow-up S 26/196 C 30/203 NS reduction in macular oedema development (p = 0.7108) | NS differences in terms of HbA1c levels between groups |

| García-Medina 2011 Spain [155] | Randomised prospective study | T2DM with NPDR but no CSME | S: Vitamin C 60 mg Vitamin E 10 mg Lutein 3 mg Zinc 13.5 mg Copper 1 mg Selenium 10 µg Manganese 1 mg Niacin 10 mg β-Carotene 3 mg Dosage = 2 tablets/day C: no placebo capsule | Vitalux Forte® (Novartis Pharma AG Ophthalmics, Basel, Switzerland) | N = 97 patients S: N = 56 C: N = 41 Mean age S 53.3 ± 11.9 C 57.0 ± 11.4 | 60 | VA: NS changes DR degree: Significant progression in C group (p < 0.01) vs. non-significant progression in S group | Significant reduced plasma lipid peroxidation end products (MDA) in S vs. increased in C group (p < 0.01) Stable TAS in the S group vs. significant decrease in C group (p = 0.02) |

| Forte 2011 Italy [156] | Randomised prospective, interventional, controlled study | T2DM and DME without macular thickening at OCT | S = Desmin 300 mg Troxerutin 300 mg C. asiatica 30 mg Melilotus 160 Dosage 1/day C = Placebo capsule | Noncommercialised supplement | N = 40 patients (eyes) S = 20 C = 20 Mean age S 63.6 ± 3.1 C 62.2 ± 3.4. | 14 | VA: NS differences CMT: NS differences between groups. Five eyes of the S group showed resolution of retinal cysts, in comparison to no changes in the C group RS (dB): S showed a significant increase at month 14 (p < 0.001) (16.43 ± 0.39) | NS differences during follow-up in terms of HbA1c, microalbuminuria or blood pressure |

| Bursell 1999 USA [157] | Randomised double-masked placebo-controlled crossover trial | T1DM without or with minimal DR | S = Vitamin E 1800 IU C = Placebo capsule Dosage 1800 IU/day | Noncommercialised supplement | N = 45 patients S = 36 (T1DM) C = 9 (ND) 4 months follow-up Crossover S = 9 (ND) C = 36 (T1DM) 4 months follow-up Mean age DM = 31.2 ± 6.8 ND = 31.6 ± 7.1 | 8 | T1DM significant increase in retinal blood flow (p < 0.001) (34.5 ± 7.8 pixel2/s) Retinal blood flow measured by mean circulation times in fluorescein angiography: C: No changes | NS differences in terms of HbA1c between groups Statistically significant creatinine clearance improvement after supplementation in T1DM subjects (p = 0.039). This change reverted after crossover. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alfonso-Muñoz, E.A.; Burggraaf-Sánchez de las Matas, R.; Mataix Boronat, J.; Molina Martín, J.C.; Desco, C. Role of Oral Antioxidant Supplementation in the Current Management of Diabetic Retinopathy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4020. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22084020

Alfonso-Muñoz EA, Burggraaf-Sánchez de las Matas R, Mataix Boronat J, Molina Martín JC, Desco C. Role of Oral Antioxidant Supplementation in the Current Management of Diabetic Retinopathy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021; 22(8):4020. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22084020

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlfonso-Muñoz, Enrique Antonio, Raquel Burggraaf-Sánchez de las Matas, Jorge Mataix Boronat, Julio César Molina Martín, and Carmen Desco. 2021. "Role of Oral Antioxidant Supplementation in the Current Management of Diabetic Retinopathy" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22, no. 8: 4020. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22084020

APA StyleAlfonso-Muñoz, E. A., Burggraaf-Sánchez de las Matas, R., Mataix Boronat, J., Molina Martín, J. C., & Desco, C. (2021). Role of Oral Antioxidant Supplementation in the Current Management of Diabetic Retinopathy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(8), 4020. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22084020