A Glance into MTHFR Deficiency at a Molecular Level

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

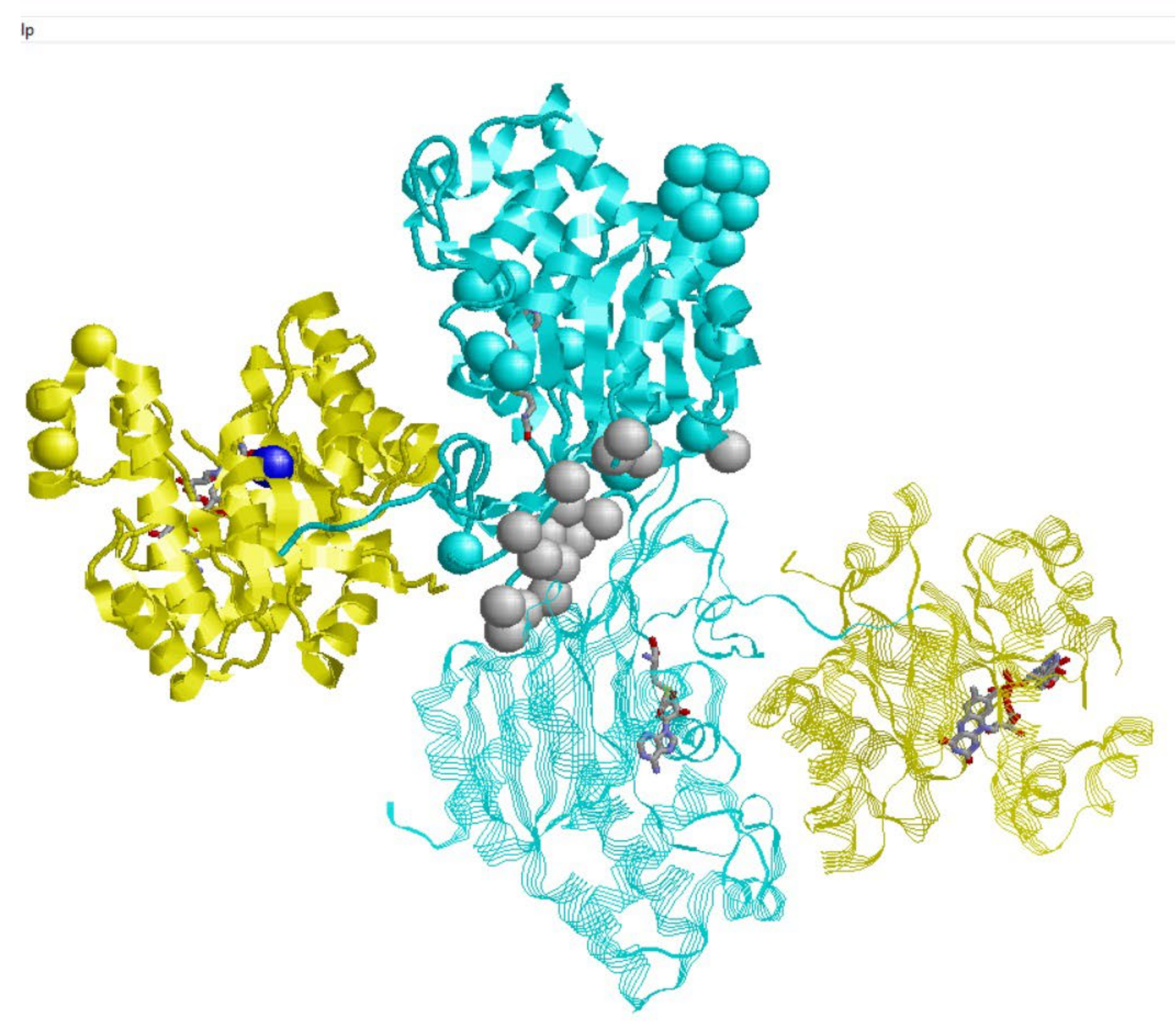

2.1. MTHFR and Protein-Protein Interactions

2.2. MTHFR and Protein Stability

| ΔΔG (kcal/mol) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variation | Effects | INPS3D | FoldX | PoPMuSiC2 | ISPRED4 | RSA (%) |

| Catalytic Domain | ||||||

| R46Q | No effect on NAD(P) affinity | −0.76 | −0.26 | −1.05 | N | 29 |

| R46W | No effect on NAD(P) affinity | −0.5 | −1.04 | −0.35 | N | 29 |

| R51P | −1.24 | −1.13 | −1.47 | N | 49 | |

| R52Q | Reduced affinity for NAD(P) | −1.06 | 0.08 | −0.77 | N | 23 |

| W59C | −1.59 | −3.58 | −2.52 | N | 2 | |

| W59S | −2.67 | −3.92 | −3.3 | N | 2 | |

| P66L | NAD(P) binding site | −0.46 | −4.09 | −0.01 | N | 20 |

| R68G | Reduced affinity for NAD(P) NAD(P) binding site | −0.92 | −0.40 | −0.59 | N | 96 |

| R82W | No effect on NAD(P) affinity | −0.66 | 0.2 | −0.81 | N | 44 |

| A113T | No effect NADPH | −1.17 | −1.44 | −1.71 | N | 0 |

| A116T | −0.65 | −2.29 | −1.95 | N | 0 | |

| H127Y | FAD binding site | −0.18 | 1.37 | −0.33 | N | 5 |

| T129N | Reduced affinity for NAD(P) FAD binding site | −1.17 | −1.37 | −0.81 | N | 7 |

| C130R | No effect on NAD(P) affinity | −1.99 | −16.08 | −1.34 | N | 1 |

| T139M | −0.34 | 0.83 | 0.29 | N | 18 | |

| Q147P | −0.46 | −2.95 | −0.91 | N | 73 | |

| G149V | −1.02 | −13.0 | −3.26 | N | 2 | |

| I153M | No effect on NAD(P) affinity | −1.56 | 0.18 | −1.71 | N | 1 |

| R157Q | No effect on NAD(P) affinity FAD binding site | −1.31 | −0.72 | −0.57 | N | 25 |

| A175T | Reduced affinity for NAD(P) FAD binding site | −1.13 | −0.73 | −0.54 | N | 8 |

| H181D | −1.79 | −2.23 | −1.5 | N | 10 | |

| R183Q | No effect on NAD(P) affinity | −1.48 | −3.34 | −0.82 | N | 16 |

| C193Y | −1.19 | −10.91 | −0.03 | N | 17 | |

| A195V | Reduced affinity for NAD(P) FAD binding site | −0.43 | 0.39 | 0 | N | 11 |

| G196D | Reduced affinity for NAD(P) | −1.08 | −3.26 | −1.18 | N | 2 |

| P202T | FAD binding site | −0.73 | −1.57 | −0.16 | N | 68 |

| V218L | Decreased affinity for FAD | −1.00 | −0.42 | −0.42 | N | 12 |

| A222V * | Decreased affinity for FAD | −0.71 | −1.08 | −0.09 | N | 11 |

| I225L | No effect on NAD(P) affinity | −1.32 | −0.57 | −1.17 | N | 0 |

| T227M | −1.58 | −2.9 | −0.14 | N | 1 | |

| P251L | −0.56 | 0.62 | −0.68 | N | 38 | |

| V253F | Reduced affinity for NAD(P) | −0.82 | −1.26 | −1 | N | 0 |

| P254S | No effect on NAD(P) affinity | −1.22 | −3.7 | −0.86 | N | 0 |

| G255V | −0.55 | −2.81 | 0.33 | N | 1 | |

| I256N | −3.24 | −3.27 | −2.47 | N | 1 | |

| F257V | −1.34 | −1.61 | −1.83 | N | 11 | |

| L323P | Substrate binding site NAD(P) binding site | −2.19 | −4.95 | −1.94 | N | 32 |

| N324S | −0.77 | −3.52 | −1.92 | N | 8 | |

| R325C | Substrate binding site | −0.78 | 0.41 | −0.34 | N | 43 |

| L333P | −3.39 | −6.05 | −3.62 | N | 0 | |

| R335C | −0.67 | −1.14 | −0.86 | N | 60 | |

| Regulatory Domain | ||||||

| M338T | −1.58 | −3.74 | −1.21 | N | 18 | |

| W339G | −2.78 | −4.46 | −2.55 | N | 20 | |

| R345C | −0.67 | −1.31 | −0.23 | N | 43 | |

| P348S | Reduced affinity for NAD(P) SAH binding site | −1.19 | −3.53 | −1.16 | N | 26 |

| H354Y | Reduced affinity for NAD(P) | −0.24 | −0.2 | −0.67 | N | 18 |

| R357C | −1.32 | −2.3 | −1.54 | N | 5 | |

| R357H | −1.28 | −1.09 | −0.29 | N | 5 | |

| R363H | Reduced affinity for NAD(P) | −1.39 | −1.34 | −0.83 | N | 6 |

| K372E | Reduced affinity for NAD(P) | −0.46 | 0.99 | −0.31 | N | 52 |

| R377C | Reduced affinity for NAD(P) | −1.17 | −3.99 | −1.4 | N | 0 |

| R377H | Reduced affinity for NAD(P) | −1.2 | −4.59 | −0.68 | N | 0 |

| W381R | −1.83 | −2.29 | −1.95 | N | 14 | |

| G387D | Reduced affinity for NAD(P) | −0.82 | −3.35 | −1.31 | I | 33 |

| G390D | −0.88 | −2.23 | 0.13 | N | 64 | |

| W421S | Reduced affinity for NAD(P) | −3.07 | −6.97 | −4 | N | 1 |

| E429A * | −0.13 | −0.79 | 0.2 | N | 50 | |

| F435S | −3.45 | −5.56 | −2.94 | N | 1 | |

| S440L | 0.03 | 2.15 | −0.55 | N | 25 | |

| Y506D | Reduced affinity for NAD(P) | −1.77 | −5.1 | −3.16 | I | 61 |

| Y512C | −1.94 | −4.31 | −2.18 | N | 2 | |

| R535Q | −0.79 | −1.61 | −0.77 | N | 25 | |

| R535W | 0.07 | −1.39 | −0.26 | N | 25 | |

| V536F | Reduced affinity for NAD(P) | −1.38 | −3.21 | −0.6 | N | 1 |

| P572L | Reduced affinity for NAD(P) | −0.43 | −7.32 | −0.09 | N | 0 |

| V574G | Reduced affinity for NAD(P) | −3.32 | −4.13 | −3.47 | N | 1 |

| V575G | Reduced affinity for NAD(P) | −3.64 | −4.06 | −3.07 | N | 8 |

| E586K | −0.8 | −5.23 | −0.99 | N | 1 | |

| L598P | Reduced affinity for NAD(P) | −2.49 | −7.34 | −2.68 | N | 22 |

| S603C | −1.03 | −1.81 | −0.7 | N | 15 | |

| L628P | Reduced affinity for NAD(P) | −0.83 | −4.47 | −2.25 | I | 57 |

| M338T | −1.58 | −3.74 | −1.21 | N | 18 | |

2.3. MTHFR Deficiency and Its Structural Model

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Characterization of Protein Surface and Annotation of Protein-Protein Interaction Sites

3.2. Prediction of ∆∆G Changes upon Single Residue Variation

3.3. Pfam-Like Model of the Regulatory Domain

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Froese, D.S.; Huemer, M.; Suormala, T.; Burda, P.; Coelho, D.; Guéant, J.L.; Landolt, M.A.; Kožich, V.; Fowler, B.; Baumgartner, M.R. Mutation Update and Review of Severe Methylenetetrahydrofolate Reductase Deficiency. Hum. Mutat. 2016, 37, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ducker, G.S.; Rabinowitz, J.D. One-Carbon Metabolism in Health and Disease. Cell Metab. 2017, 25, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Froese, D.S.; Fowler, B.; Baumgartner, M.R. Vitamin B12, folate, and the methionine remethylation cycle-biochemistry, pathways, and regulation. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2019, 42, 673–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yamada, K.; Chen, Z.; Rozen, R.; Matthews, R.G. Effects of common polymorphisms on the properties of recombinant human methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 14853–14858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bhatia, M.; Thakur, J.; Suyal, S.; Oniel, R.; Chakraborty, R.; Pradhan, S.; Sharma, M.; Sengupta, S.; Laxman, S.; Masakapalli, S.K.; et al. Allosteric inhibition of MTHFR prevents futile SAM cycling and maintains nucleotide pools in one-carbon metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 16037–16057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Froese, D.S.; Kopec, J.; Rembeza, E.; Bezerra, G.A.; Oberholzer, A.E.; Suormala, T.; Lutz, S.; Chalk, R.; Borkowska, O.; Baumgartner, M.R.; et al. Structural basis for the regulation of human 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase by phosphorylation and S-adenosylmethionine inhibition. Nat. Commun. 2018, 11, 2261–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Burda, P.; Schäfer, A.; Suormala, T.; Rummel, T.; Bürer, C.; Heuberger, D.; Frapolli, M.; Giunta, C.; Sokolová, J.; Vlášková, H.; et al. Insights into severe 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase deficiency: Molecular genetic and enzymatic characterization of 76 patients. Hum. Mutat. 2015, 36, 611–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frosst, P.; Blom, H.J.; Milos, R.; Goyette, P.; Sheppard, C.A.; Matthews, R.G.; Boers, G.J.H.; den Heijer, M.; Kluijtmans, L.A.J.; van den Heuvel, L.P.; et al. Worldwide distribution of a common methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase mutation. Nat. Genet. 1995, 10, 111–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skibola, C.F.; Smith, M.T.; Kane, E.; Roman, E.; Rollinson, S.; Cartwright, R.A.; Morgan, G. Polymorphisms in the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene are associated with susceptibility to acute leukemia in adults. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 12810–12815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bezerra, G.A.; Holenstein, A.; Foster, W.R.; Xie, B.; Hicks, K.G.; Bürer, C.; Lutz, S.; Mukherjee, A.; Sarkar, D.; Bhattacharya, D.; et al. Identification of small molecule allosteric modulators of 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) by targeting its unique regulatory domain. Biochimie 2021, 183, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savojardo, C.; Fariselli, P.; Martelli, P.L.; Casadio, R. ISPRED4: Interaction sites prediction in protein structures with a refining grammar model. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 1656–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casadio, R.; Savojardo, C.; Fariselli, P.; Capriotti, E.; Martelli, P.L. Turning failures into applications: The problem of protein ΔΔG prediction. Methods Mol. Biol. 2021; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Savojardo, C.; Fariselli, P.; Martelli, P.L.; Casadio, R. INPS-MD: A web server to predict stability of protein variants from sequence and structure. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 2542–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schymkowitz, J.; Borg, J.; Stricher, F.; Nys, R.; Rousseau, F.; Serrano, L. The FoldX web server: An online force field. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 33, W382–W388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pucci, F.; Bernaerts, K.V.; Kwasigroch, J.M.; Rooman, M. Quantification of biases in predictions of protein stability changes upon mutations. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 3659–3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Savojardo, C.; Manfredi, M.; Martelli, P.L.; Casadio, R. Solvent accessibility of residues undergoing pathogenic variations in Humans: From protein structures to protein Sequences. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 7, 626363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casadio, R.; Vassura, M.; Tiwari, S.; Fariselli, P.; Martelli, P.L. Correlating disease-related mutations to their effect on protein stability: A large-scale analysis of the human proteome. Hum. Mutat. 2011, 32, 1161–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savojardo, C.; Babbi, G.; Martelli, P.L.; Casadio, R. Functional and structural features of disease-related protein variants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Savojardo, C.; Babbi, G.; Martelli, P.L.; Casadio, R. Mapping OMIM disease-related variations on protein domains reveals an association among variation type, Pfam models, and disease classes. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 617016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Savojardo, C.; Babbi, G.; Baldazzi, D.; Martelli, P.L.; Casadio, R. A Glance into MTHFR Deficiency at a Molecular Level. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23010167

Savojardo C, Babbi G, Baldazzi D, Martelli PL, Casadio R. A Glance into MTHFR Deficiency at a Molecular Level. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022; 23(1):167. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23010167

Chicago/Turabian StyleSavojardo, Castrense, Giulia Babbi, Davide Baldazzi, Pier Luigi Martelli, and Rita Casadio. 2022. "A Glance into MTHFR Deficiency at a Molecular Level" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 23, no. 1: 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23010167

APA StyleSavojardo, C., Babbi, G., Baldazzi, D., Martelli, P. L., & Casadio, R. (2022). A Glance into MTHFR Deficiency at a Molecular Level. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(1), 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23010167