Antiosteoporotic Nanohydroxyapatite Zoledronate Scaffold Seeded with Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stromal Cells for Bone Regeneration: A 3D In Vitro Model

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis and Characterization of the Apatitic Powders

2.2. Scaffolds Preparation and Characterization

2.3. In Vitro Fracture Model

2.4. Cell Viability and Morphology

2.5. Cell Differentiation and Metabolic Activity

2.5.1. Gene Expression by RT-PCR

2.5.2. Immunoenzymatic Assays

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Scaffolds Characterization

3.2. Cells Viability and Morphology

3.3. Cell Differentiation and Metabolic Activity

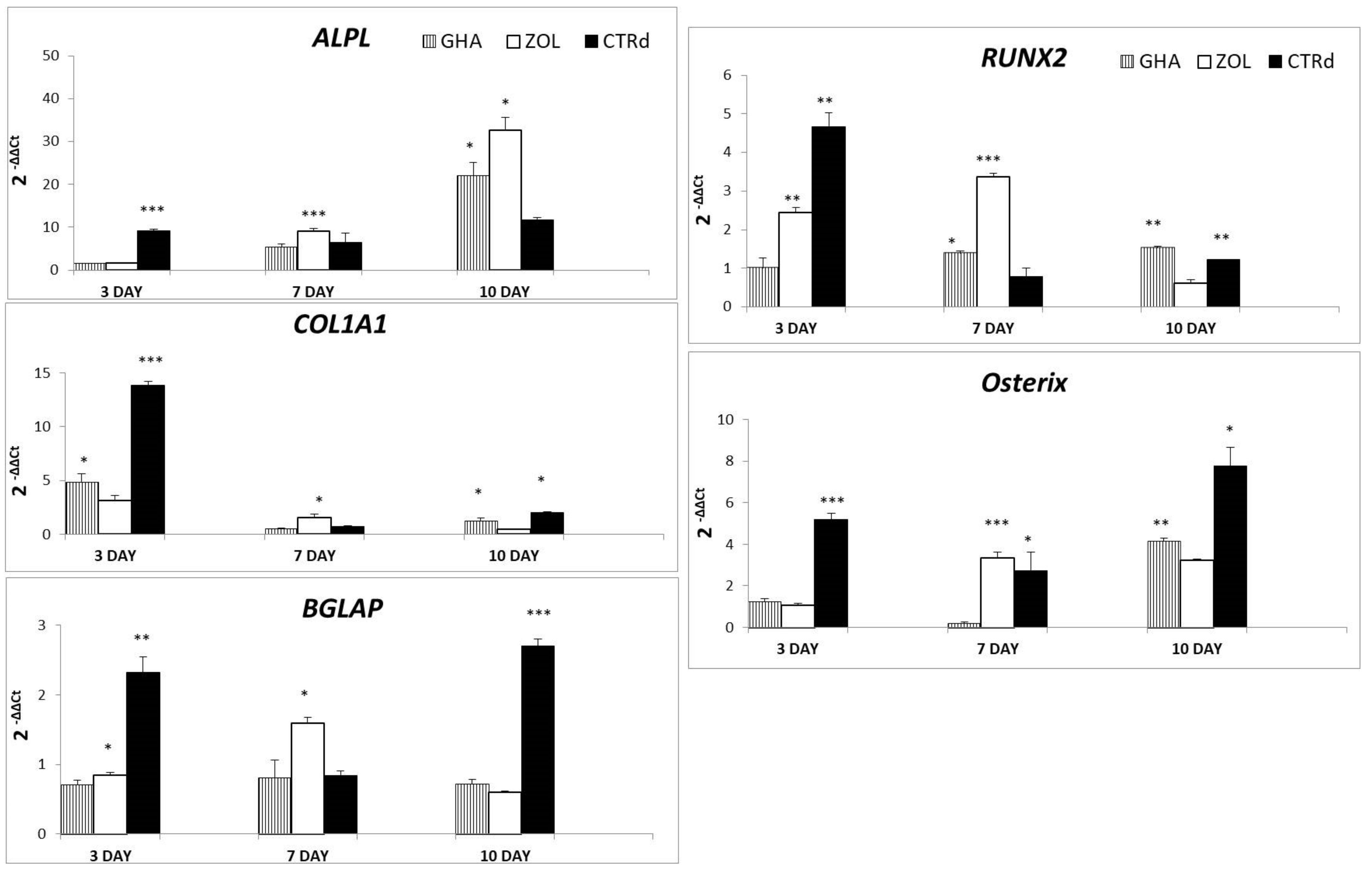

3.3.1. Gene Expression by RT-PCR

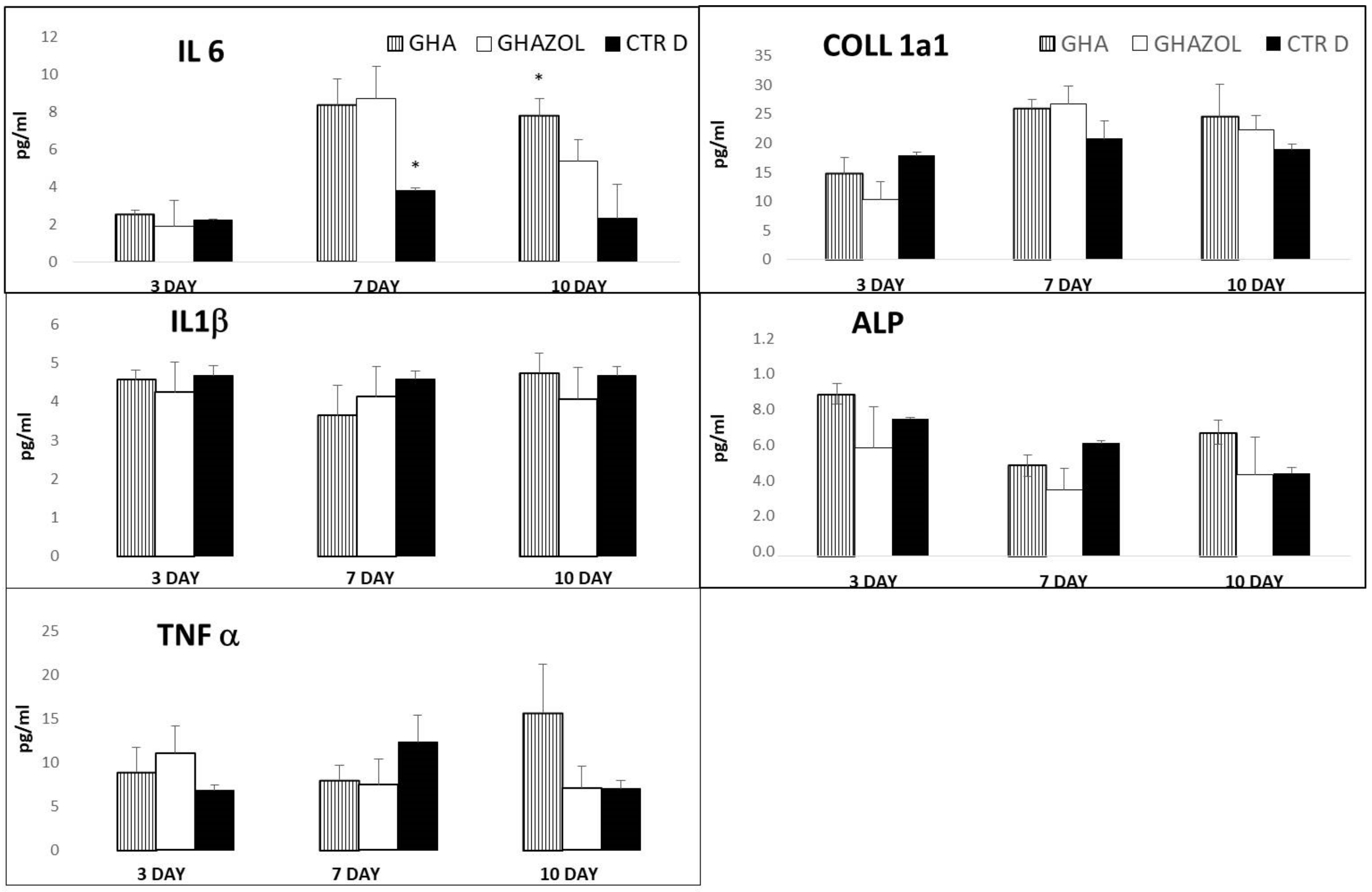

3.3.2. Immunoenzymatic Assays

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Calori, G.M.; Mazza, E.; Colombo, M.; Ripamonti, C. The use of bone-graft substitutes in large bone defects: Any specific needs? Injury 2011, 42 (Suppl. 2), S56–S63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campana, V.; Milano, G.; Pagano, E.; Barba, M.; Cicione, C.; Salonna, G.; Lattanzi, W.; Logroscino, G. Bone substitutes in orthopaedic surgery: From basic science to clinical practice. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2014, 25, 2445–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez de Grado, G.; Keller, L.; Idoux-Gillet, Y.; Wagner, Q.; Musset, A.M.; Benkirane-Jessel, N.; Bornert, F.; Offner, D. Bone substitutes: A review of their characteristics, clinical use, and perspectives for large bone defects management. J. Tissue Eng. 2018, 9, 2041731418776819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Veronesi, F.; Borsari, V.; Martini, L.; Visani, A.; Gasbarrini, A.; Brodano, G.B.; Fini, M. The Impact of Frailty on Spine Surgery: Systematic Review on 10 years Clinical Studies. Aging Dis. 2021, 12, 625–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernlund, E.; Svedbom, A.; Ivergård, M.; Compston, J.; Cooper, C.; Stenmark, J.; McCloskey, E.V.; Jönsson, B.; Kanis, J.A. Osteoporosis in the European Union: Medical management, epidemiology and economic burden. A report prepared in collaboration with the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) and the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industry Associations (EFPIA). Arch. Osteoporos 2013, 8, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pfeiffenberger, M.; Damerau, A.; Lang, A.; Buttgereit, F.; Hoff, P.; Gaber, T. Fracture Healing Research-Shift towards In Vitro Modeling? Biomedicines 2021, 9, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnell, O.; Kanis, J.A. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos. Int. 2006, 17, 1726–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamanna, F.; Gambardella, A.; Contartese, D.; Visani, A.; Fini, M. Nano-Based Biomaterials as Drug Delivery Systems Against Osteoporosis: A Systematic Review of Preclinical and Clinical Evidence. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conley, R.B.; Adib, G.; Adler, R.A.; Åkesson, K.E.; Alexander, I.M.; Amenta, K.C.; Blank, R.D.; Brox, W.T.; Carmody, E.E.; Chapman-Novakofski, K.; et al. Secondary Fracture Prevention: Consensus Clinical Recommendations from a Multistakeholder Coalition. J. Bone Miner Res. 2020, 35, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chevalley, T.; Brandi, M.L.; Cavalier, E.; Harvey, N.C.; Iolascon, G.; Cooper, C.; Hannouche, D.; Kaux, J.F.; Kurth, A.; Maggi, S.; et al. How can the orthopedic surgeon ensure optimal vitamin D status in patients operated for an osteoporotic fracture? Osteoporos Int. 2021, 32, 1921–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, A.B.; Ehrenstein, V.; Szepligeti, S.K.; Lunde, A.; Lagerros, Y.T.; Westerlund, A.; Tell, G.S.; Sørensen, H.T. Thirty-five-year trends in first-time hospitalization for hip fracture, 1-year mortality, and the prognostic impact of comorbidity: A Danish nationwide cohort study, 1980–2014. Epidemiology 2017, 28, 898–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgström, F.; Karlsson, L.; Ortsäter, G.; Norton, N.; Halbout, P.; Cooper, C.; Lorentzon, M.; McCloskey, E.V.; Harvey, N.C.; Javaid, M.K.; et al. International Osteoporosis Foundation. Fragility fractures in Europe: Burden, management and opportunities. Arch. Osteoporos. 2020, 15, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tian, K.V.; Chass, G.A.; Di Tommaso, D. Simulations reveal the role of composition into the atomic-level flexibility of bioactive glass cements. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 18, 837–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, O.; Kohidai, L.; Kohidai, Z.; Dobo-Nagy, C.; Csomo, K.B.; Lajko, M.; Mozes, M.; Keki, S.; Deak, G.; Tian, K.V.; et al. Cell physiological effects of glass ionomer cements on fibroblast cells. Toxicol. Vitr. 2019, 61, 104627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochicchio, B.; Barbaro, K.; De Bonis, A.; Rau, J.V.; Pepe, A. Electrospun poly(d,l-lactide)/gelatin/glass-ceramics tricomponent nanofibrous scaffold for bone tissue engineering. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2020, 108, 1064–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Ashok, D.; Nisbet, D.R.; Gautam, V. Bioinspired surface modification of orthopedic implants for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2019, 219, 119366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codrea, C.I.; Croitoru, A.-M.; Baciu, C.C.; Melinescu, A.; Ficai, D.; Fruth, V.; Ficai, A. Advances in Osteoporotic Bone Tissue Engineering. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigi, A.; Boanini, E. Calcium Phosphates as Delivery Systems for Bisphosphonates. J. Funct. Biomater. 2018, 9, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nancollas, G.H.; Tang, R.; Phipps, R.J.; Henneman, Z.; Gulde, S.; Wu, W.; Mangood, A.; Russell, R.G.G.; Ebetino, F.H. Novel insights into actions of bisphosphonates on bone: Differences in interactions with hydroxyapatite. Bone 2006, 38, 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, M.A.; Xia, Z.; Barnett, B.L.; Triffitt, J.T.; Phipps, R.J.; Dunford, J.E.; Locklin, R.M.; Ebetino, F.H.; Russell, R.G.G. Differences between bisphosphonates in binding affinities for hydroxyapatite. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomater. 2009, 92B, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boanini, E.; Torricelli, P.; Gazzano, M.; Della Bella, E.; Fini, M.; Bigi, A. Combined effect of strontium and zoledronate on hydroxyapatite structure and bone cell responses. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 5619–5626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panzavolta, S.; Torricelli, P.; Amadori, S.; Parrilli, A.; Rubini, K.; della Bella, E.; Fini, M.; Bigi, A. 3D interconnected porous biomimetic scaffolds: In vitro cell response. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2013, 101, 3560–3570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundelacruz, S.; Li, C.; Choi, Y.J.; Levin, M.; Kaplan, D.L. Bioelectric modulation of wound healing in a 3D in vitro model of tissue-engineered bone. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 6695–6705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Di Filippo, M.F.; Amadori, S.; Casolari, S.; Bigi, A.; Dolci, L.S.; Panzavolta, S. Cylindrical Layered Bone Scaffolds with Anisotropic Mechanical Properties as Potential Drug Delivery Systems. Molecules 2019, 24, 1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schmittgen, T.D.; Livak, K.J. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 1101–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuljanin, J.; Janković, I.; Nedeljković, J.; Prstojević, D.; Marinković, V. Spectrophotometric determination of alendronate in pharmaceutical formulations via complex formation with Fe(III) ions. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2002, 28, 1215–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annamalai, R.T.; Turner, P.A.; Carson, W.F.; Levi, B.; Kunkel, S.; Stegemann, J.P. Harnessing macrophage-mediated degradation of gelatin microspheres for spatiotemporal control of BMP2 release. Biomaterials 2018, 161, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, R.-L.; Sun, Y.; Ho, C.-K.; Liu, K.; Tang, Q.-Q.; Xie, Y.; Li, Q. IL-6 potentiates BMP-2-induced osteogenesis and adipogenesis via two different BMPR1A-mediated pathways. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, N.A. Cell-specific paracrine actions of IL-6 family cytokines from bone, marrow and muscle that control bone formation and resorption. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2016, 79, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.D.; Amirthalingam, S.; Kim, S.L.; Lee, S.S.; Rangasamy, J.; Hwang, N.S. Biomimetic Materials and Fabrication Approaches for Bone Tissue Engineering. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2017, 6, 1700612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagani, S.; Torricelli, P.; Veronesi, F.; Salamanna, F.; Cepollaro, S.; Fini, M. An advanced tri-culture model to evaluate the dynamic interplay among osteoblasts, osteoclasts, and endothelial cells. J. Cell Physiol. 2018, 233, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forte, L.; Torricelli, P.; Boanini, E.; Gazzano, M.; Fini, M.; Bigi, A. Antiresorptive and anti-angiogenetic octacalcium phosphate functionalized with bisphosphonates: An in vitro tri-culture study. Acta Biomater. 2017, 54, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, S.; Nazemi, M.; Jonkers, I.; Geris, L. Use of Computational Modeling to Study Joint Degeneration: A Review. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barh, D.; Chaitankar, V.; Yiannakopoulou, E.C.; Salawu, E.O.; Chowbina, S.; Ghosh, P.; Azevedo, V. In Silico Models: From Simple Networks to Complex Diseases. In Animal Biotechnology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; pp. 385–404. [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi, M.; Verbruggen, S.W.; Lacroix, D. In silico bone mechanobiology: Modeling a multifaceted biological system. WIREs Syst. Biol. Med. 2016, 8, 485–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peric, M.; Dumic-Cule, I.; Grcevic, D.; Matijasic, M.; Verbanac, D.; Paul, R.; Grgurevic, L.; Trkulja, V.; Bagi, C.M.; Vukicevic, S. The rational use of animal models in the evaluation of novel bone regenerative therapies. Bone 2015, 70, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Russell, W.M.S.; Burch, R.L. The Principles of Humane Experimental Technique. Universities Federation for Animal Welfare Wheathampstead; Methuen & Co. Ltd.: London, UK, 1959; (Reprinted in 1992). [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, W.H.; Miclau, T.; Chow, S.K.-H.; Yang, F.F.; Alt, V. Fracture healing in osteoporotic bone. Injury 2016, 47 (Suppl. 2), S21–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronesi, F.; Torricelli, P.; Borsari, V.; Tschon, M.; Rimondini, L.; Fini, M. Mesenchymal stem cells in the aging and osteoporotic population. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 2011, 21, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torricelli, P.; Fini, M.; Giavaresi, G.; Giardino, R. In vitro models to test orthopedic biomaterials in view of their clinical application in osteoporotic bone. Int. J. Artif. Organs 2004, 27, 658–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forte, L.; Sarda, S.; Torricelli, P.; Combes, C.; Brouillet, F.; Marsan, O.; Salamanna, F.; Fini, M.; Boanini, E.; Bigi, A. Multifunctionalization Modulates Hydroxyapatite Surface Interaction with Bisphosphonate: Antiosteoporotic and Antioxidative Stress Materials. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 5, 3429–3439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Salamanna, F.; Giavaresi, G.; Contartese, D.; Bigi, A.; Boanini, E.; Parrilli, A.; Lolli, R.; Gasbarrini, A.; Brodano, G.B.; Fini, M. Effect of strontium substituted ß-TCP associated to mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow and adipose tissue on spinal fusion in healthy and ovariectomized rat. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 20046–20056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boanini, E.; Torricelli, P.; Fini, M.; Bigi, A. Osteopenic bone cell response to strontium-substituted hydroxyapatite. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2011, 22, 2079–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Symbol | Gene | Primer FW | Primer RV | T Annealing | Amplicon Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALPL | Alkaline phosphatase liver/bone/kidney | QT00012957 * | 55 °C 20′′ | 110 bp | |

| COL1A1 | Collagen type 1, chain a 1 | QT00037793 * | 55 °C 20′′ | 118 bp | |

| BGLAP | Osteocalcin | QT00232771 * | 55 °C 20′′ | 90 bp | |

| RUNX2 | Runt related transcription factor 2 | CTTCACAAATCCTCCCCAAGT | AGGCGGTCAGAGAACAAAC | 60 °C 20′′ | 212 bp |

| SP7 | Osterix | QT000213514 * | 55 °C 20′′ | 120 bp | |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | TGGTATCGTGGAAGGACTCA | GCAGGGATGATGTTCTGGA | 56 °C 20′′ | 123 bp |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tschon, M.; Boanini, E.; Sartori, M.; Salamanna, F.; Panzavolta, S.; Bigi, A.; Fini, M. Antiosteoporotic Nanohydroxyapatite Zoledronate Scaffold Seeded with Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stromal Cells for Bone Regeneration: A 3D In Vitro Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5988. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23115988

Tschon M, Boanini E, Sartori M, Salamanna F, Panzavolta S, Bigi A, Fini M. Antiosteoporotic Nanohydroxyapatite Zoledronate Scaffold Seeded with Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stromal Cells for Bone Regeneration: A 3D In Vitro Model. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022; 23(11):5988. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23115988

Chicago/Turabian StyleTschon, Matilde, Elisa Boanini, Maria Sartori, Francesca Salamanna, Silvia Panzavolta, Adriana Bigi, and Milena Fini. 2022. "Antiosteoporotic Nanohydroxyapatite Zoledronate Scaffold Seeded with Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stromal Cells for Bone Regeneration: A 3D In Vitro Model" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 23, no. 11: 5988. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23115988

APA StyleTschon, M., Boanini, E., Sartori, M., Salamanna, F., Panzavolta, S., Bigi, A., & Fini, M. (2022). Antiosteoporotic Nanohydroxyapatite Zoledronate Scaffold Seeded with Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stromal Cells for Bone Regeneration: A 3D In Vitro Model. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(11), 5988. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23115988