BrWAX3, Encoding a β-ketoacyl-CoA Synthase, Plays an Essential Role in Cuticular Wax Biosynthesis in Chinese Cabbage

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Phenotypic Characterization and Genetic Analysis of Glossy Trait in SD369

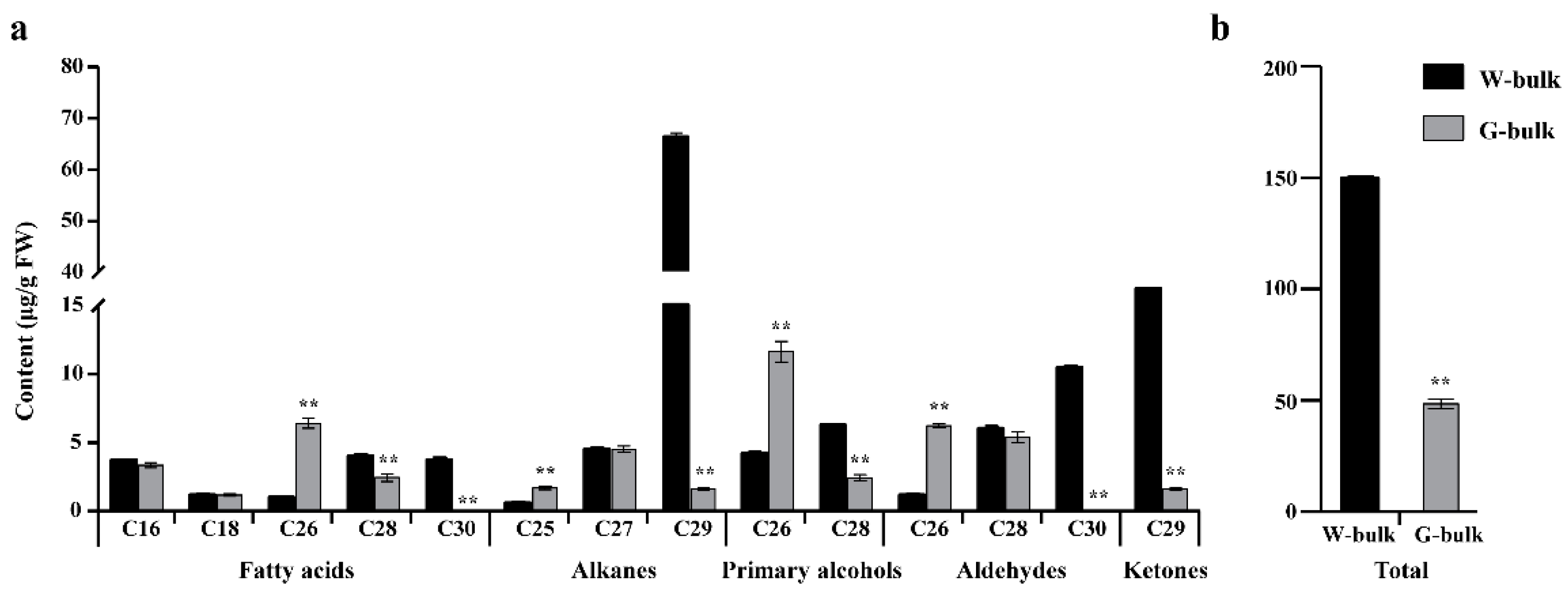

2.2. Cuticular Wax Analysis via GC-MS

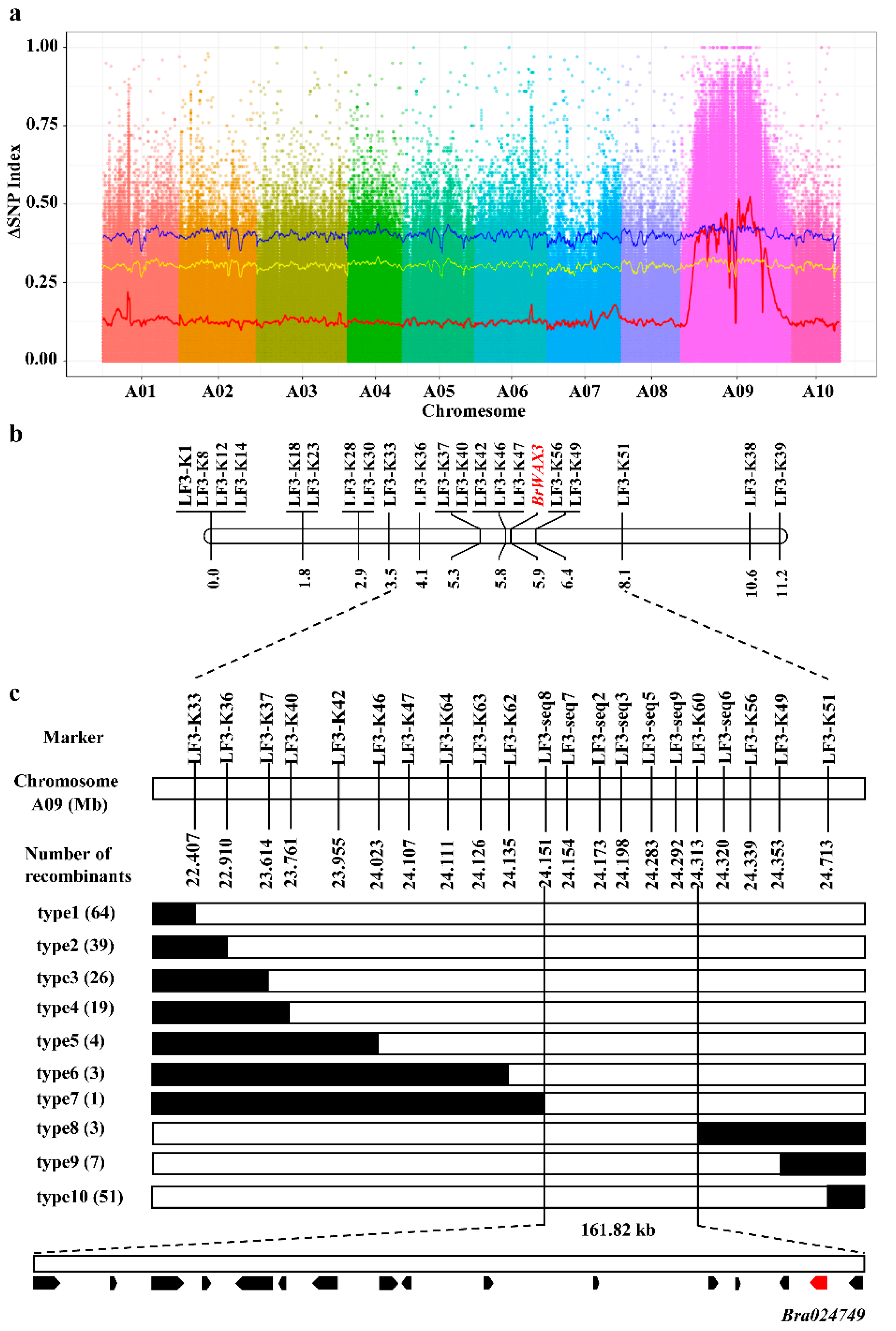

2.3. Fine Mapping of the BrWAX3 Gene

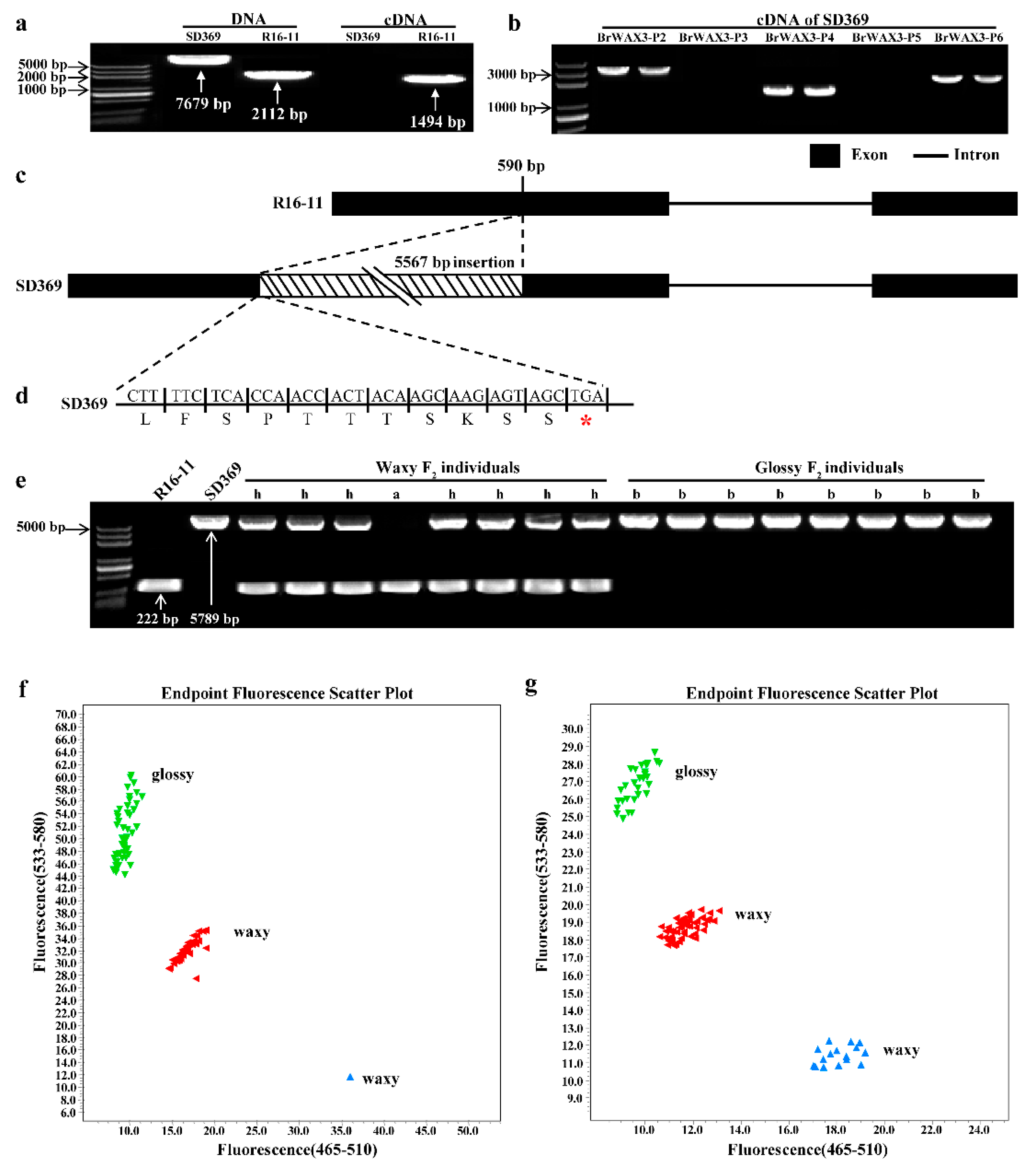

2.4. Candidate Gene Analysis

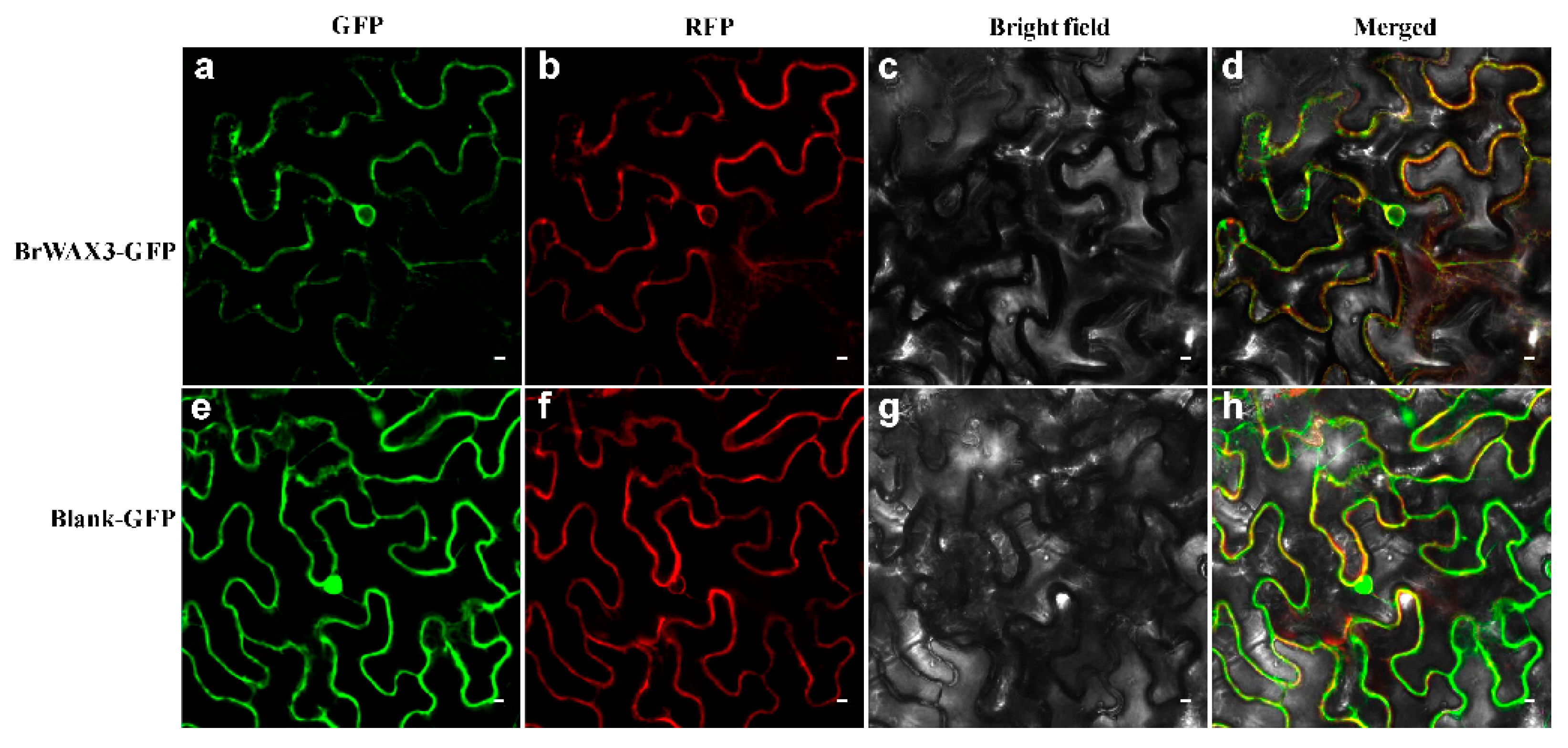

2.5. Expression Pattern Analysis and Subcellular Localization of BrWAX3

2.6. Sequence and Expression Pattern Analysis of BrCER6.A07

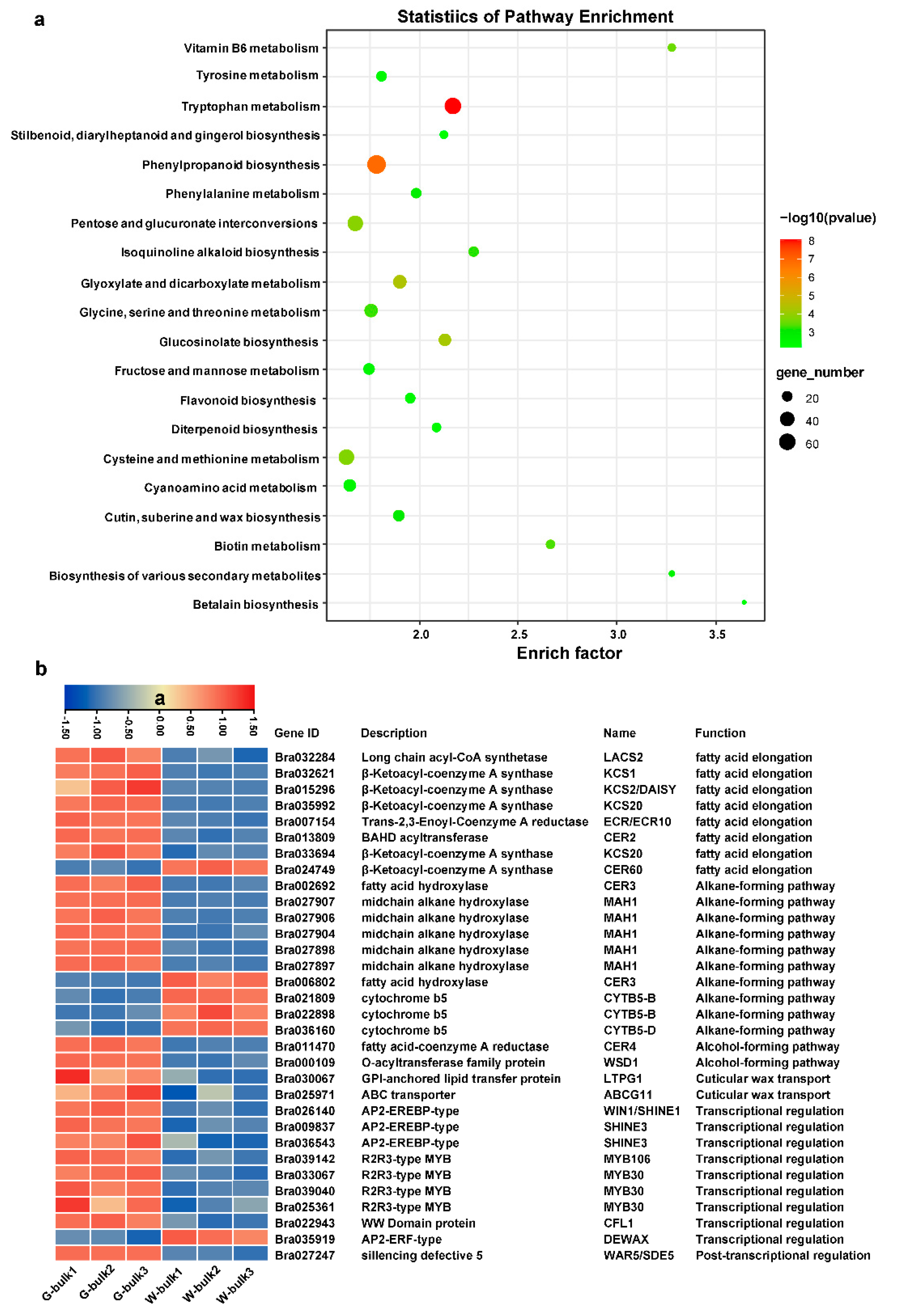

2.7. Transcriptome Analysis in Waxy and Glossy Stems

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials

4.2. Cryo-Scanning Electron Microscopy (cryo-SEM) and Gas Chromatography-Mass Mpectrometry (GC-MS)

4.3. Identification of Candidate Genes via Bulked-Segregant Analysis Sequencing (BSA-Seq) and Kompetitive Allele-Specific PCR (KASP) Assays

4.4. Gene Cloning and Sequence Analysis

4.5. RNA Extraction and Expression Analysis

4.6. Subcellular Localization

4.7. Transcriptome Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Riederer, M.; Schreiber, L. Protecting against water loss: Analysis of the barrier properties of plant cuticles. J. Exp. Bot. 2001, 52, 2023–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haslam, T.M.; Kunst, L. Arabidopsis ECERIFERUM2-LIKEs are mediators of condensing enzyme function. Plant Cell Physiol. 2021, 61, 2126–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beisson, F.; Li-Beisson, Y.; Pollard, M. Solving the puzzles of cutin and suberin polymer biosynthesis. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2012, 15, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Fang, Z.; Zhuang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Lv, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Sun, P.; Tang, J.; Liu, D.; et al. Fine-Mapping and analysis of Cgl1, a gene conferring glossy trait in Cabbage (Brassica oleracea L. var. capitata). Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Lee, S.B.; Suh, M.C. Advances in the understanding of cuticular waxes in Arabidopsis thaliana and crop species. Plant Cell Rep. 2015, 34, 557–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernard, A.; Joubès, J. Arabidopsis cuticular waxes: Advances in synthesis, export and regulation. Prog. Lipid Res. 2013, 52, 110–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdenx, B.; Bernard, A.; Domergue, F.; Pascal, S.; Léger, A.; Roby, D.; Pervent, M.; Vile, D.; Haslam, R.P.; Napier, J.A.; et al. Overexpression of Arabidopsis ECERIFERUM1 promotes wax very-long-chain alkane biosynthesis and influences plant response to biotic and abiotic stresses. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Yang, Q.; Fu, T.; Zhou, Y. Overexpression of the Brassica napus BnLAS gene in Arabidopsis affects plant development and increases drought tolerance. Plant Cell Rep. 2011, 30, 373–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, T.M.; Mañas-Fernández, A.; Zhao, L.; Kunst, L. Arabidopsis ECERIFERUM2 is a component of the fatty acid elongation machinery required for fatty acid extension to exceptional lengths. Plant Physiol. 2012, 160, 1164–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, A.A.; Clemens, S.; Zachgo, S.; Giblin, E.M.; Taylor, D.C.; Kunst, L. CUT1, an Arabidopsis gene required for cuticular wax biosynthesis and pollen fertility, encodes a very-long-chain fatty acid condensing enzyme. Plant Cell 1999, 11, 825–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieber, P.; Schorderet, M.; Ryser, U.; Buchala, A.; Kolattukudy, P.; Métraux, J.P.; Nawrath, C. Transgenic Arabidopsis plants expressing a fungal cutinase show alterations in the structure and properties of the cuticle and postgenital organ fusions. Plant Cell 2000, 12, 721–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haslam, T.M.; Kunst, L. Extending the story of very-long-chain fatty acid elongation. Plant Sci. 2013, 210, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaudoin, F.; Wu, X.; Li, F.; Haslam, R.P.; Markham, J.E.; Zheng, H.; Napier, J.A.; Kunst, L. Functional characterization of the Arabidopsis beta-ketoacyl-coenzyme A reductase candidates of the fatty acid elongase. Plant Physiol. 2009, 150, 1174–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millar, A.A.; Kunst, L. Very-long-chain fatty acid biosynthesis is controlled through the expression and specificity of the condensing enzyme. Plant J. 1997, 12, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.B.; Jung, S.J.; Go, Y.S.; Kim, H.U.; Kim, J.K.; Cho, H.J.; Park, O.K.; Suh, M.C. Two Arabidopsis 3-ketoacyl CoA synthase genes, KCS20 and KCS2/DAISY, are functionally redundant in cuticular wax and root suberin biosynthesis, but differentially controlled by osmotic stress. Plant J. 2009, 60, 462–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Jung, J.H.; Lee, S.B.; Go, Y.S.; Kim, H.J.; Cahoon, R.; Markham, J.E.; Cahoon, E.B.; Suh, M.C. Arabidopsis 3-ketoacyl-coenzyme a synthase9 is involved in the synthesis of tetracosanoic acids as precursors of cuticular waxes, suberins, sphingolipids, and phospholipids. Plant Physiol. 2013, 162, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, J.; Post-Beittenmiller, D.; Jaworski, J.G. KCS1 encodes a fatty acid elongase 3-ketoacyl-CoA synthase affecting wax biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1999, 17, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiebig, A.; Mayfield, J.A.; Miley, N.L.; Chau, S.; Fischer, R.L.; Preuss, D. Alterations in CER6, a gene identical to CUT1, differentially affect long-chain lipid content on the surface of pollen and stems. Plant Cell 2000, 12, 2001–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Ayaz, A.; Zheng, M.; Yang, X.; Zaman, W.; Zhao, H.; Lü, S. Arabidopsis KCS5 and KCS6 play redundant roles in wax synthesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooker, T.S.; Millar, A.A.; Kunst, L. Significance of the expression of the CER6 condensing enzyme for cuticular wax production in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2002, 129, 1568–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascal, S.; Bernard, A.; Sorel, M.; Pervent, M.; Vile, D.; Haslam, R.P.; Napier, J.A.; Lessire, R.; Domergue, F.; Joubès, J. The Arabidopsis cer26 mutant, like the cer2 mutant, is specifically affected in the very long chain fatty acid elongation process. Plant J. 2013, 73, 733–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Kim, R.J.; Lee, S.B.; Chung Suh, M. Protein-protein interactions in fatty acid elongase complexes are important for very-long-chain fatty acid synthesis. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 3004–3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, J.; Cao, W.; Tong, L.; Fang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhuang, M.; Wang, Y.; Yang, L.; Lv, H. Identification and validation of an ECERIFERUM2-LIKE gene controlling cuticular wax biosynthesis in cabbage (Brassica oleracea L. var. capitata L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 2021, 134, 4055–4066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Liu, H.; Wei, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Su, H.; Zhao, X.; Tian, B.; Zhang, X.W.; Yuan, Y. BrWAX2 plays an essential role in cuticular wax biosynthesis in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. pekinensis). Theor. Appl. Genet. 2022, 135, 693–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Tai, X.; Ren, Y.; Chen, J.; Bo, T. Genome-wide analysis of coding and long non-coding RNAs involved in cuticular wax biosynthesis in cabbage (Brassica oleracea L. var. capitata). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Ji, J.; Yang, L.; Fang, Z.; Zhuang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Lv, H.; Wang, Y.; Sun, P.; Tang, J.; et al. Fine-mapping and transcriptome analysis of BoGL-3, a wax-less gene in cabbage (Brassica oleracea L. var. capitata). Mol. Genet. Genom. 2019, 294, 1231–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Tang, J.; Liu, Z.; Dong, X.; Zhuang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Lv, H.; Sun, P.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; et al. Cgl2 plays an essential role in cuticular wax biosynthesis in cabbage (Brassica oleracea L. var. capitata). BMC Plant Biol. 2017, 17, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Dong, X.; Liu, Z.; Tang, J.; Zhuang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Lv, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Fang, Z.; et al. Fine mapping and candidate gene identification for wax biosynthesis locus, BoWax1 in Brassica oleracea L. var. capitata. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, Z.; Wang, P.; Wang, Q.; Yang, S.; Feng, H. Fine mapping of BrWax1, a gene controlling cuticular wax biosynthesis in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. pekinensis). Mol. Breeding 2013, 32, 867–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, Y.; Xie, F.; Kuang, H.; Wan, Z. Cloning of the Brcer1 gene involved in cuticular wax production in a glossy mutant of non-heading Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L. var. communis). Mol. Breeding 2017, 37, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Song, G.; Wang, N.; Huang, S.; Feng, H. A single SNP in Brcer1 results in wax deficiency in Chinese cabbage (Brassica campestris L. ssp. pekinensis). Sci. Hortic. 2021, 282, 110019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuels, L.; Kunst, L.; Jetter, R. Sealing plant surfaces: Cuticular wax formation by epidermal cells. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2008, 59, 683–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preuss, D.; Lemieux, B.; Yen, G.; Davis, R.W. A conditional sterile mutation eliminates surface components from Arabidopsis pollen and disrupts cell signaling during fertilization. Genes Dev. 1993, 7, 974–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hülskamp, M.; Kopczak, S.D.; Horejsi, T.F.; Kihl, B.K.; Pruitt, R.E. Identification of genes required for pollen-stigma recognition in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1995, 8, 703–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Geeta, R.; Das, S. Comparative sequence analysis across Brassicaceae, regulatory diversity in KCS5 and KCS6 homologs from Arabidopsis thaliana and Brassica juncea, and intronic fragment as a negative transcriptional regulator. Gene Expr. Patterns 2020, 38, 119146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, H.; Abe, A.; Yoshida, K.; Kosugi, S.; Natsume, S.; Mitsuoka, C.; Uemura, A.; Utsushi, H.; Tamiru, M.; Takuno, S.; et al. QTL-seq: Rapid mapping of quantitative trait loci in rice by whole genome resequencing of DNA from two bulked populations. Plant J. 2013, 74, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Sun, R.; Wu, J.; Liu, S.; Bai, Y.; Mun, J.H.; Bancroft, I.; Cheng, F.; et al. The genome of the mesopolyploid crop species Brassica rapa. Nat. Genet. 2011, 43, 1035–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Handsaker, B.; Wysoker, A.; Fennell, T.; Ruan, J.; Homer, N.; Marth, G.; Abecasis, G.; Durbin, R. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2078–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Liu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Su, H.; Wei, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, X.W.; Yuan, Y. Map-based cloning and characterization of Br-dyp1, a gene conferring dark yellow petal color trait in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. pekinensis). Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 841328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Yu, W.; Wei, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, X.; Tian, B.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, X. An extended KASP-SNP resource for molecular breeding in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. pekinensis). PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ooijen, J.; Van, J.W. JoinMap 4, Software for the Calculation of Genetic Linkage Maps in Experimental Populations, version 4; Kyazma B.V.: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCt method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mravec, J.; Skůpa, P.; Bailly, A.; Hoyerová, K.; Krecek, P.; Bielach, A.; Petrásek, J.; Zhang, J.; Gaykova, V.; Stierhof, Y.D.; et al. Subcellular homeostasis of phytohormone auxin is mediated by the ER-localized PIN5 transporter. Nature 2009, 459, 1136–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. HISAT: A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. TBtools: An integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Population | Total | Waxy | Glossy | Expected ratio | χ2 | χ20.05 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 (SD369) | 10 | 10 | 0 | - | - | - |

| P2 (R16-11) | 10 | 0 | 10 | - | - | - |

| F1 | 15 | 15 | 0 | - | - | - |

| F2-small | 142 | 102 | 40 | 3:1 | 0.76 | 3.84 |

| F2-large | 3980 | 3026 | 954 | 3:1 | 2.25 | 3.84 |

| BC1P1 (F1 × SD369) | 1020 | 540 | 494 | 1:1 | 2.05 | 3.84 |

| BC1P2 (F1 × R16-11) | 300 | 300 | 0 | - | - | - |

| Gene Name | Gene Position on A09 | Arabidopsis Homolog | Gene Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bra024763 | 24151883-24153849 | AT1G25280 | Member of TLP family |

| Bra024762 | 24164515-24164946 | AT5G05020 | Pollen Ole e 1 allergen and extension family protein |

| Bra024761 | 24171584-24174217 | AT1G25320 | Leucine-rich repeat protein kinase family protein |

| Bra024760 | 24179389-24180542 | AT1G25340 | putative transcription factor (MYB116) |

| Bra024759 | 24185650-24190615 | AT1G25350 | glutamine-tRNA ligase, putative/glutaminyl-tRNA synthetase |

| Bra024758 | 24192301-24193325 | AT1G25370 | hypothetical protein (DUF1639) |

| Bra024757 | 24197064-24199869 | AT1G25375 | Metallo-hydrolase/oxidoreductase superfamily protein |

| Bra024756 | 24207077-24209333 | AT1G25380 | Encodes a mitochondrial-localized NAD+ transporter that transports NAD+ in a counter exchange mode with ADP and AMP in vitro |

| Bra024755 | 24210118-24212198 | AT1G25390 | Protein kinase superfamily protein |

| Bra024754 | 24226168-24227349 | AT2G05970 | F-box protein (DUF295) |

| Bra024753 | 24253251-24253559 | AT1G25422 | hypothetical protein |

| Bra024752 | 24279278-24280968 | AT1G29470 | S-adenosyl-L-methionine-dependent methyltransferases superfamily protein |

| Bra024751 | 24285640-24285933 | AT1G25425 | CLAVATA3/ESR-RELATED 43 |

| Bra024750 | 24299524-24301114 | AT1G25440 | B-box type zinc finger protein with CCT domain-containing protein |

| Bra024749 | 24304800-24306911 | AT1G25450 | Encodes KCS5, a member of the β-ketoacyl-CoA synthase family involved in the biosynthesis of VLCFA (very long chain fatty acids); CER60 |

| Bra024748 | 24311235-24312823 | AT1G69710 | Regulator of chromosome condensation (RCC1) family with FYVE zinc finger domain-containing protein |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, S.; Tang, H.; Wei, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Su, H.; Niu, L.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, X. BrWAX3, Encoding a β-ketoacyl-CoA Synthase, Plays an Essential Role in Cuticular Wax Biosynthesis in Chinese Cabbage. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10938. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms231810938

Yang S, Tang H, Wei X, Zhao Y, Wang Z, Su H, Niu L, Yuan Y, Zhang X. BrWAX3, Encoding a β-ketoacyl-CoA Synthase, Plays an Essential Role in Cuticular Wax Biosynthesis in Chinese Cabbage. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022; 23(18):10938. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms231810938

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Shuangjuan, Hao Tang, Xiaochun Wei, Yanyan Zhao, Zhiyong Wang, Henan Su, Liujing Niu, Yuxiang Yuan, and Xiaowei Zhang. 2022. "BrWAX3, Encoding a β-ketoacyl-CoA Synthase, Plays an Essential Role in Cuticular Wax Biosynthesis in Chinese Cabbage" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 23, no. 18: 10938. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms231810938

APA StyleYang, S., Tang, H., Wei, X., Zhao, Y., Wang, Z., Su, H., Niu, L., Yuan, Y., & Zhang, X. (2022). BrWAX3, Encoding a β-ketoacyl-CoA Synthase, Plays an Essential Role in Cuticular Wax Biosynthesis in Chinese Cabbage. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(18), 10938. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms231810938