Dynamic Evaluation of Natural Killer Cells Subpopulations in COVID-19 Patients

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- ✓

- CD16-CD56+/++ with poor cytotoxic, but high cytokine production capacity, having a secretory phenotype.

- ✓

- CD16+CD56++ represents a NK subset with both secretory and cytolytic properties. These cells were studied in the context of melanoma and researchers found differences between CD56bright CD16- and/or CD16+ NK cells with higher activation state for the CD16+ cells, higher degranulation capacity, and higher cytokine production [9,10]. However, in the melanoma study, this cell type was only found in a metastatic lymph node [9]. IFNγ producing circulating CD56++ NK cells were found by de Jonge et al. in melanoma patients inversely correlated with survival [11].

- ✓

- ✓

- CD16++CD56- is another subtype of NK cells with a potential role in different types of infections, especially in HIV-infected patients [12]. Forconi et al. considered this kind of NK cells as an adaptation model of CD16+CD56+ in chronic infections, mainly focused on ADCC, as CD16 is highly expressed [13].

2. Results

2.1. Characterization of the Patients and Baseline Results

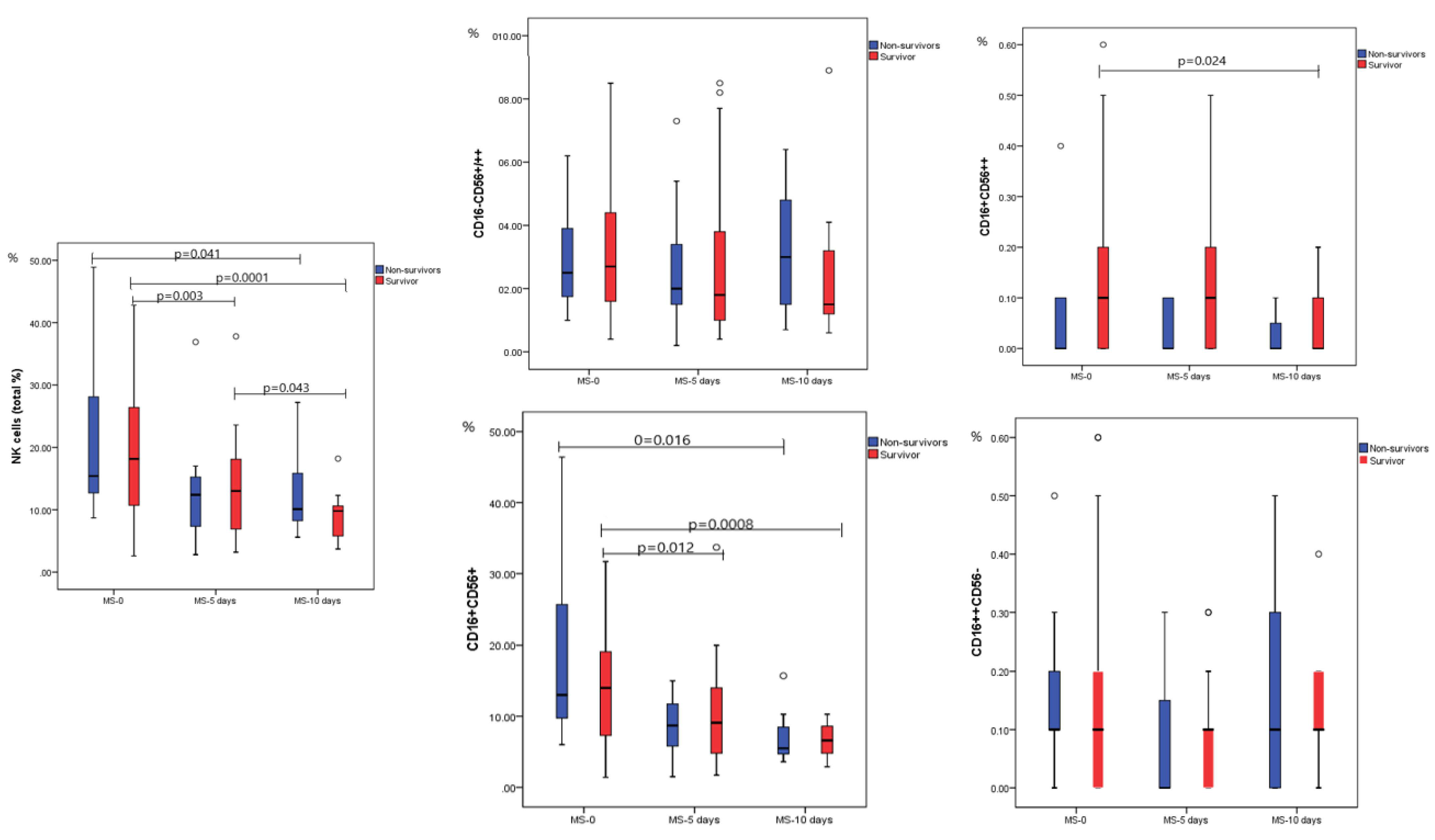

2.2. Dynamic Analysis of NK Cell Subpopulations

2.3. Expression of PD-1 on NK Cells according to Disease Severity and Outcome

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Patient Recruitment and Sample Collection

- -

- Mild grade (Stage I) was defined as a disease with few symptoms (low fever, cough, fatigue, anorexia, shortness of breath, myalgias), without evidence of viral pneumonia or hypoxia.

- -

- Moderate grade (Stage II) was defined as a disease with fever and respiratory symptoms, associated with pulmonary imaging findings, but no signs of severe pneumonia, including SpO2 ≥ 90% on room air.

- -

- Severe grade (Stage III) was defined as a disease with severe pneumonia, with clinical signs of pneumonia (fever, cough, dyspnea) plus one of the following: respiratory rate > 30 breaths/min; severe respiratory distress; or SpO2 < 90% on room air.

- -

- Critical grade (Stage IV) was defined as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), septic shock, and/or multiple organ dysfunction.

4.2. Natural Killer Lymphocyte Subset Analysis

4.3. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Caligiuri, M.A. Human natural killer cells. Blood 2008, 112, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vetvicka, V.; Sima, P.; Vannucci, L. Trained immunity as an adaptive branch of innate immunity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Zotto, G.; Marcenaro, E.; Vacca, P.; Sivori, S.; Pende, D.; Della Chiesa, M.; Moretta, F.; Ingegnere, T.; Mingari, M.C.; Moretta, A.; et al. Markers and function of human NK cells in normal and pathological conditions. Cytom. Part B Clin. Cytom. 2017, 92, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Alter, G.; Malenfant, J.M.; Altfeld, M. CD107a as a functional marker for the identification of natural killer cell activity. J. Immunol. Methods 2004, 294, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodridge, J.P.; Önfelt, B.; Malmberg, K.J. Newtonian cell interactions shape natural killer cell education. Immunol. Rev. 2015, 267, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dębska-Zielkowska, J.; Moszkowska, G.; Zieliński, M.; Zielińska, H.; Dukat-Mazurek, A.; Trzonkowski, P.; Stefańska, K. KIR Receptors as Key Regulators of NK Cells Activity in Health and Disease. Cells 2021, 10, 1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amand, M.; Iserentant, G.; Poli, A.; Sleiman, M.; Fievez, V.; Sanchez, I.P.; Sauvageot, N.; Michel, T.; Aouali, N.; Janji, B.; et al. Human CD56dim CD16dim Cells As an Individualized Natural Killer Cell Subset. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casado, J.L.; Moraga, E.; Vizcarra, P.; Velasco, H.; Martín-Hondarza, A.; Haemmerle, J.; Gómez, S.; Quereda, C.; Vallejo, A. Expansion of CD56DIM CD16NEG nk cell subset and increased inhibitory kirs in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Viruses 2022, 14, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messaoudene, M.; Fregni, G.; Fourmentraux-Neves, E.; Chanal, J.; Maubec, E.; Mazouz-Dorval, S.; Couturaud, B.; Girod, A.; Sastre-Garau, X.; Albert, S.; et al. Mature cytotoxic CD56bright/CD16+ natural killer cells can infiltrate lymph nodes adjacent to metastatic melanoma. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Michel, T.; Poli, A.; Cuapio, A.; Briquemont, B.; Iserentant, G.; Ollert, M.; Zimmer, J. Human CD56bright NK Cells: An Update. J. Immunol. 2016, 196, 2923–2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jonge, K.; Ebering, A.; Nassiri, S.; Maby-El Hajjami, H.; Ouertatani-Sakouhi, H.; Baumgaertner, P.; Speiser, D.E. Circulating CD56bright NK cells inversely correlate with survival of melanoma patients. Sci. Reports 2019, 9, 4487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Poli, A.; Michel, T.; Thérésine, M.; Andrès, E.; Hentges, F.; Zimmer, J. CD56bright natural killer (NK) cells: An important NK cell subset. Immunology 2009, 126, 458–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forconi, C.S.; Oduor, C.I.; Oluoch, P.O.; Ong’echa, J.M.; Münz, C.; Bailey, J.A.; Moormann, A.M. A New Hope for CD56negCD16pos NK Cells as Unconventional Cytotoxic Mediators: An Adaptation to Chronic Diseases. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Milush, J.M.; López-Vergès, S.; York, V.A.; Deeks, S.G.; Martin, J.N.; Hecht, F.M.; Lanier, L.L.; Nixon, D.F. CD56negCD16+ NK cells are activated mature NK cells with impaired effector function during HIV-1 infection. Retrovirology 2013, 10, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Björkström, N.K.; Riese, P.; Heuts, F.; Andersson, S.; Fauriat, C.; Ivarsson, M.A.; Björklund, A.T.; Flodström-Tullberg, M.; Michaëlsson, J.; Rottenberg, M.E.; et al. Expression patterns of NKG2A, KIR, and CD57 define a process of CD56dim NK-cell differentiation uncoupled from NK-cell education. Blood 2010, 116, 3853–3864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Niedźwiedzka-Rystwej, P.; Majchrzak, A.; Aksak-Wąs, B.; Serwin, K.; Czajkowski, Z.; Grywalska, E.; Korona-Głowniak, I.; Roliński, J.; Parczewski, M. Programmed Cell Death-1/Programmed Cell Death-1 Ligand as Prognostic Markers of Coronavirus Disease 2019 Severity. Cells 2022, 11, 1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghbash, P.S.; Eslami, N.; Shamekh, A.; Entezari-Maleki, T.; Baghi, H.B. SARS-CoV-2 infection: The role of PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 axis. Life Sci. 2021, 270, 119124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, C.; Li, M.; Zhu, S.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, L.; Xu, D.; Xu, J.; Li, Z.; Li, W.; Cui, J. PD-1-positive Natural Killer Cells have a weaker antitumor function than that of PD-1-negative Natural Killer Cells in Lung Cancer. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 17, 1964–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beenen, A.C.; Sauerer, T.; Schaft, N.; Dörrie, J. Beyond Cancer: Regulation and Function of PD-L1 in Health and Immune-Related Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortaz, E.; Jamaati, H.; Varahram, M.; Dezfuli, N.K.; Adocok, I.M. Programmed Cell Death Protein 1 (PD-1) Molecule in Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)? Tanaffos 2021, 20, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Huțanu, A.; Georgescu, A.M.; Andrejkovits, A.V.; Au, W.; Dobreanu, M. Insights into Innate Immune Response Against SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Rev. Română Med. Lab. 2021, 29, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coveney, C.; Tellier, M.; Lu, F.; Maleki-Toyserkani, S.; Jones, R.; Bart, V.M.T.; Pring, E.; Alrubayyi, A.; Richter, F.C.; Scourfield, D.O.; et al. Innate immunology in COVID-19—A living review. Part I: Viral entry, sensing and evasion. Oxford Open Immunol. 2020, 1, iqaa004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, P.R.S.; Alrubayyi, A.; Pring, E.; Bart, V.M.T.; Jones, R.; Coveney, C.; Lu, F.; Tellier, M.; Maleki-Toyserkani, S.; Richter, F.C.; et al. Innate immunology in COVID-19—A living review. Part II: Dysregulated inflammation drives immunopathology. Oxford Open Immunol. 2020, 1, iqaa005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.N.; You, Y.; Cui, X.M.; Gao, H.X.; Wang, G.L.; Zhang, S.B.; Yao, L.; Duan, L.J.; Zhu, K.L.; Wang, Y.L.; et al. Single-cell immune profiling reveals distinct immune response in asymptomatic COVID-19 patients. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021 61 2021, 6, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, D.; Etna, M.P.; Rizzo, F.; Sandini, S.; Severa, M.; Coccia, E.M. Innate immune response to sars-cov-2 infection: From cells to soluble mediators. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palermo, E.; Di Carlo, D.; Sgarbanti, M.; Hiscott, J. Type I Interferons in COVID-19 Pathogenesis. Biology 2021, 10, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Hou, H.; Yao, Y.; Wu, S.; Huang, M.; Ran, X.; Zhou, H.; Liu, Z.; Sun, Z. Systemically comparing host immunity between survived and deceased COVID-19 patients. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2020, 17, 875–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcinuño, S.; Gil-Etayo, F.J.; Mancebo, E.; López-Nevado, M.; Lalueza, A.; Díaz-Simón, R.; Pleguezuelo, D.E.; Serrano, M.; Cabrera-Marante, O.; Allende, L.M.; et al. Effective Natural Killer Cell Degranulation Is an Essential Key in COVID-19 Evolution. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Terunuma, H.; Nieda, M. Exploring the Utility of NK Cells in COVID-19. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Survivors n = 42 | Non-Survivors n = 11 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, years ± SD | 69.8 ± 13.1 | 75.6 ± 10.2 | 0.179 |

| Gender (male), n (%) | 22 (52.4%) | 5 (45.5%) | 0.943 |

| Clinical parameters | |||

| Disease severity | 0.014 | ||

| Mild, n (%) | 6 (14.3%) | - | |

| Moderate, n (%) | 14 (33.3%) | - | |

| Severe/critical, n (%) | 22 (52.4%) | 11 (100%) | |

| SaO2 % | 92.1% ± 5.1 | 79.6% ± 9.2 | <0.0001 |

| Antiviral therapy, n (%) | 27 (64.3%) | 7 (63.6%) | 0.754 |

| Antibiotherapy, n (%) | 33 (78.5%) | 11 (100%) | 0.217 |

| Vaccination | 13 (30.9%) | 3 (27.3%) | 0.894 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Hypertension | 28 (66.7%) | 11 (100%) | 0.026 |

| Chronic Cardiovascular disease | 22 (52.4%) | 9 (81.8%) | 0.078 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 6 (14.3%) | 3 (27.3%) | 0.307 |

| Asthma | 1 (2.4%) | 2 (18.2%) | 0.044 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 7 (16.7%) | 2 (18.2%) | 0.905 |

| Chronic hepatopathy | 3 (7.1%) | 0 (0%) | 0.361 |

| Other | 32 (76.7%) | 9 (81.8%) | 0.691 |

| Laboratory parameters | |||

| Leucocytes (WBC) | 8.87 ±4.12 | 9.42 ±4.14 | 0.679 |

| Neutrophils (%) | 78.68 ± 9.69 | 84.78 ± 6.14 | 0.077 |

| Neutrophils (#) | 6.83 ± 3.77 | 8.14 ± 3.97 | 0.289 |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 11.82 (3.33–36.31) | 7.31 (4.48–15.49) | 0.070 |

| Lymphocytes (#) | 0.83 (0.33–2.22) | 0.73 (0.30–0.93) | 0.050 |

| Monocytes (%) | 6.89 (0.68–17.45) | 5.48 (3.42–12.68) | 0.395 |

| Monocytes (#) | 0.56 (0.05–1.84) | 0.54 (0.30–0.82) | 0.904 |

| Natural Killer cells subpopulations | |||

| NK cells (total %) | 18.15 (2.60–42.80) | 15.40 (8.70–48.90) | 0.684 |

| NK cells (total #) | 0.15 (0.02–0.59) | 0.13 (0.06–0.30) | 0.339 |

| CD16−CD56+/++ | 2.70 (0.40–18.30) | 2.50 (1.00–6.20) | 0.613 |

| CD16+CD56++ | 0.10 (0.00–0.70) | 0.00 (0.00–0.40) | 0.086 |

| CD16+CD56+ | 14.0 (1.40–39.30) | 13.0 (6.0–46.40) | 0.496 |

| CD16++CD56− | 0.10 (0.00–0.60) | 0.10 (0.00–0.50) | 0.316 |

| NK cells | Mild (n = 6) | Moderate (n = 14) | Severe/Critical (n = 33) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NK cells (total %) | 10.7 (8.1–19.7) | 23.4 (6.8–33.2) | 18.7 (2.6–49.2) | 0.032 * 0.879 ** 0.029 *** |

| CD16-CD56+/++ | 1.55 (1.20–3.20) | 3.55 (0.80–7.70) | 2.60 (0.40–18.30) | 0.231* 0.753 ** 0.106 *** |

| CD16+CD56++ | 0.10 (0.00–0.20) | 0.10 (0.00–0.30) | 0.10 (0.00–0.70) | 0.496 * 0.421 ** 0.869 *** |

| CD16+CD56+ | 7.25 (4.90–14.40) | 18.15 (4.20–31.70) | 13.60 (1.40–46.40) | 0.069 * 0.762 ** 0.026 *** |

| CD16++CD56− | 0.25 (0.00–0.60) | 0.10 (0.00–0.20) | 0.10 (0.00–0.60) | 0.291 * 0.817 ** 0.305 *** |

| Excitation LASER | Fluorochrome | Specificity | Relative Brightness | Band-Pass filters (nm) | Mouse Antibody |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blue (488 nm) | BD Pharmingen™ PE | Human CD56 | Bright | 575/26 | BD 555516 |

| BD Pharmingen™ PE-Cy7™ | Human PD-1 | Brightest | 780/60 | BD 561272 | |

| BD Pharmingen™ PerCP-Cy 5.5 | Human CD45 | Moderate | 695/40 | BD 567310 | |

| Red (633 nm) | BD Pharmingen™ Alexa Fluor® 700 | Human CD16 | Dim | 730/45 | BD 560713 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huțanu, A.; Manu, D.; Gabor, M.R.; Văsieșiu, A.M.; Andrejkovits, A.V.; Dobreanu, M. Dynamic Evaluation of Natural Killer Cells Subpopulations in COVID-19 Patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11875. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms231911875

Huțanu A, Manu D, Gabor MR, Văsieșiu AM, Andrejkovits AV, Dobreanu M. Dynamic Evaluation of Natural Killer Cells Subpopulations in COVID-19 Patients. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022; 23(19):11875. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms231911875

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuțanu, Adina, Doina Manu, Manuela Rozalia Gabor, Anca Meda Văsieșiu, Akos Vince Andrejkovits, and Minodora Dobreanu. 2022. "Dynamic Evaluation of Natural Killer Cells Subpopulations in COVID-19 Patients" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 23, no. 19: 11875. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms231911875

APA StyleHuțanu, A., Manu, D., Gabor, M. R., Văsieșiu, A. M., Andrejkovits, A. V., & Dobreanu, M. (2022). Dynamic Evaluation of Natural Killer Cells Subpopulations in COVID-19 Patients. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(19), 11875. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms231911875