DNA Methylation Alterations in Fractionally Irradiated Rats and Breast Cancer Patients Receiving Radiotherapy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

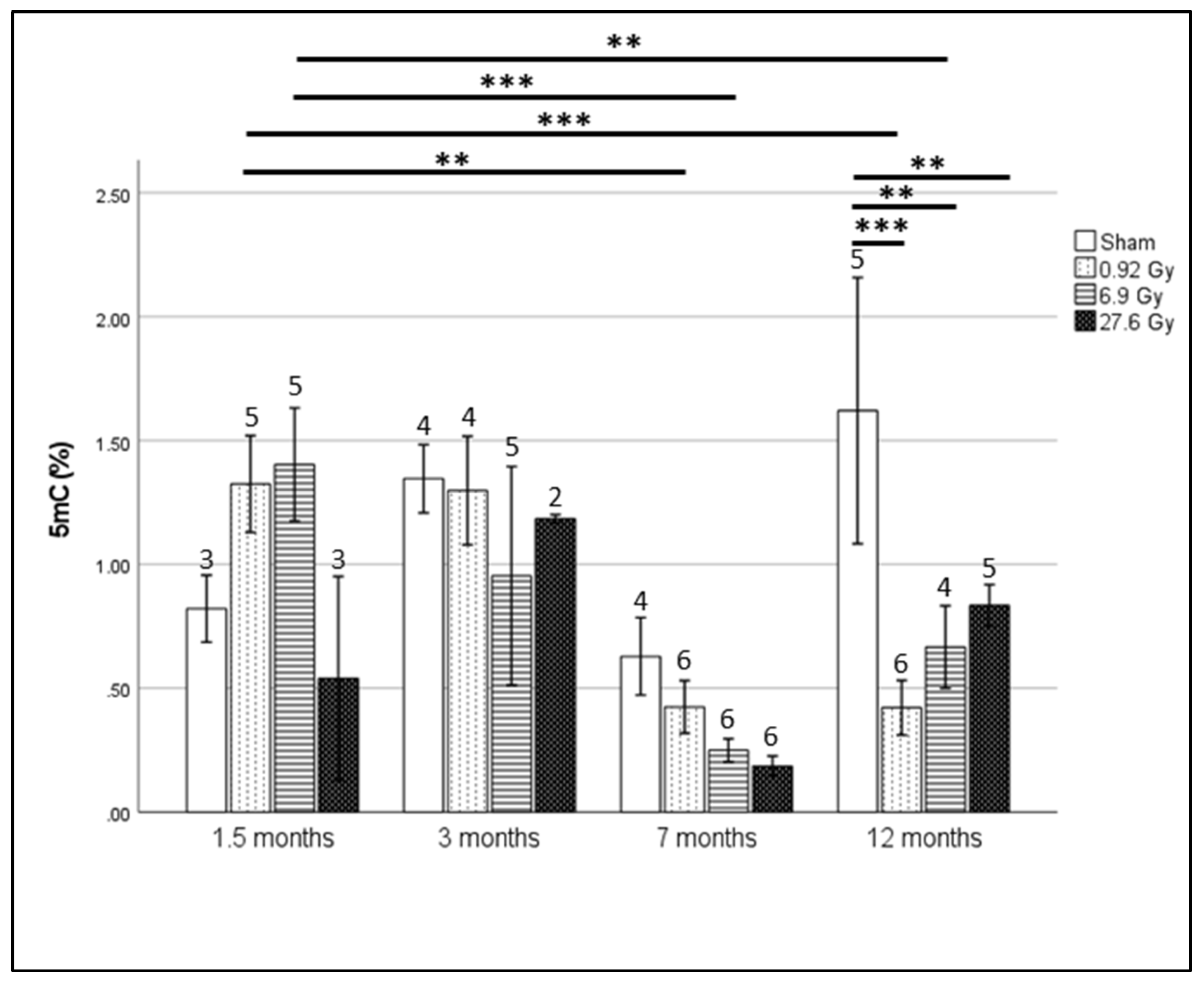

2.1. Global Hypomethylation Observed at 12 Months after Whole Heart Rat Irradiation

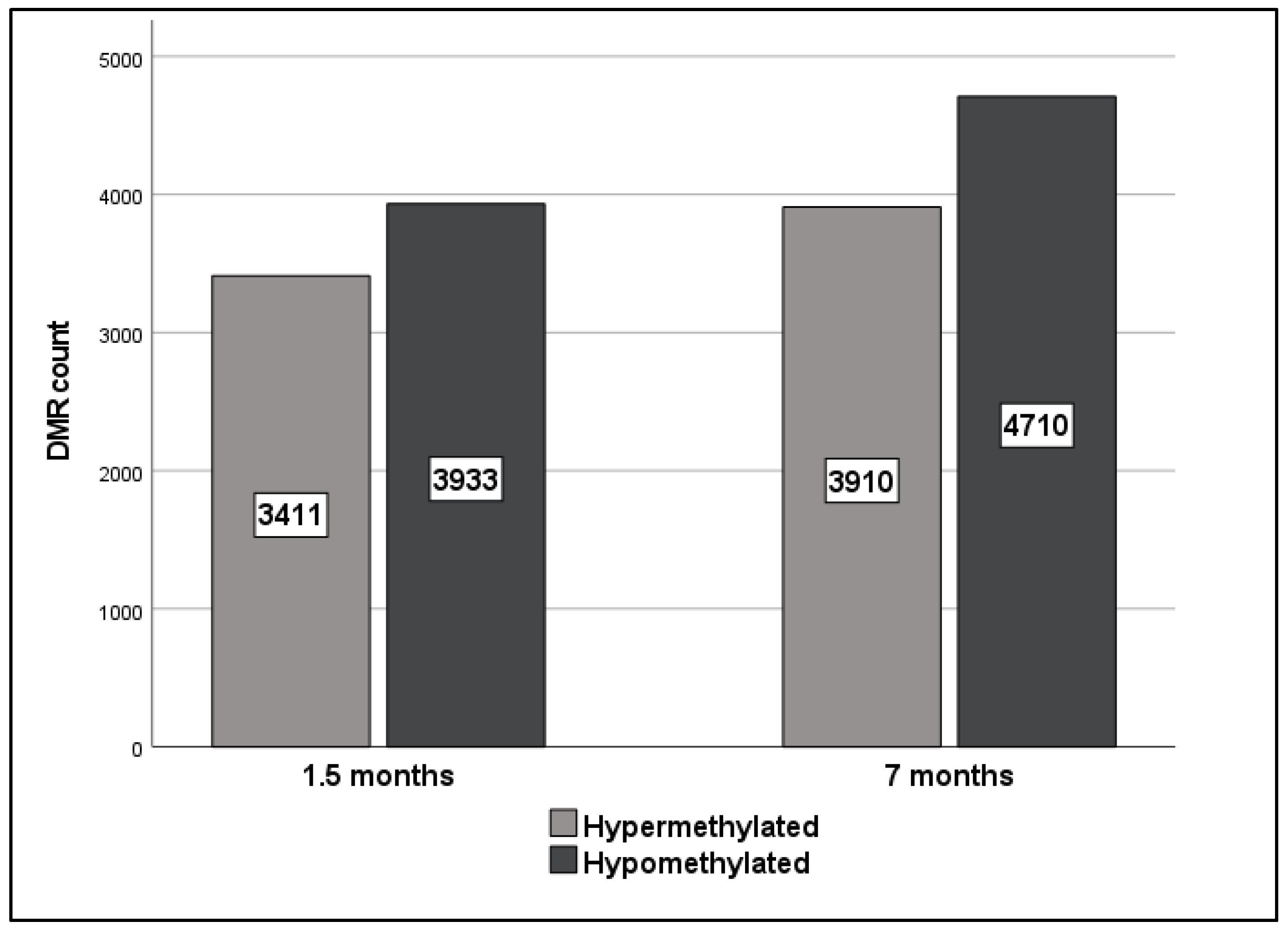

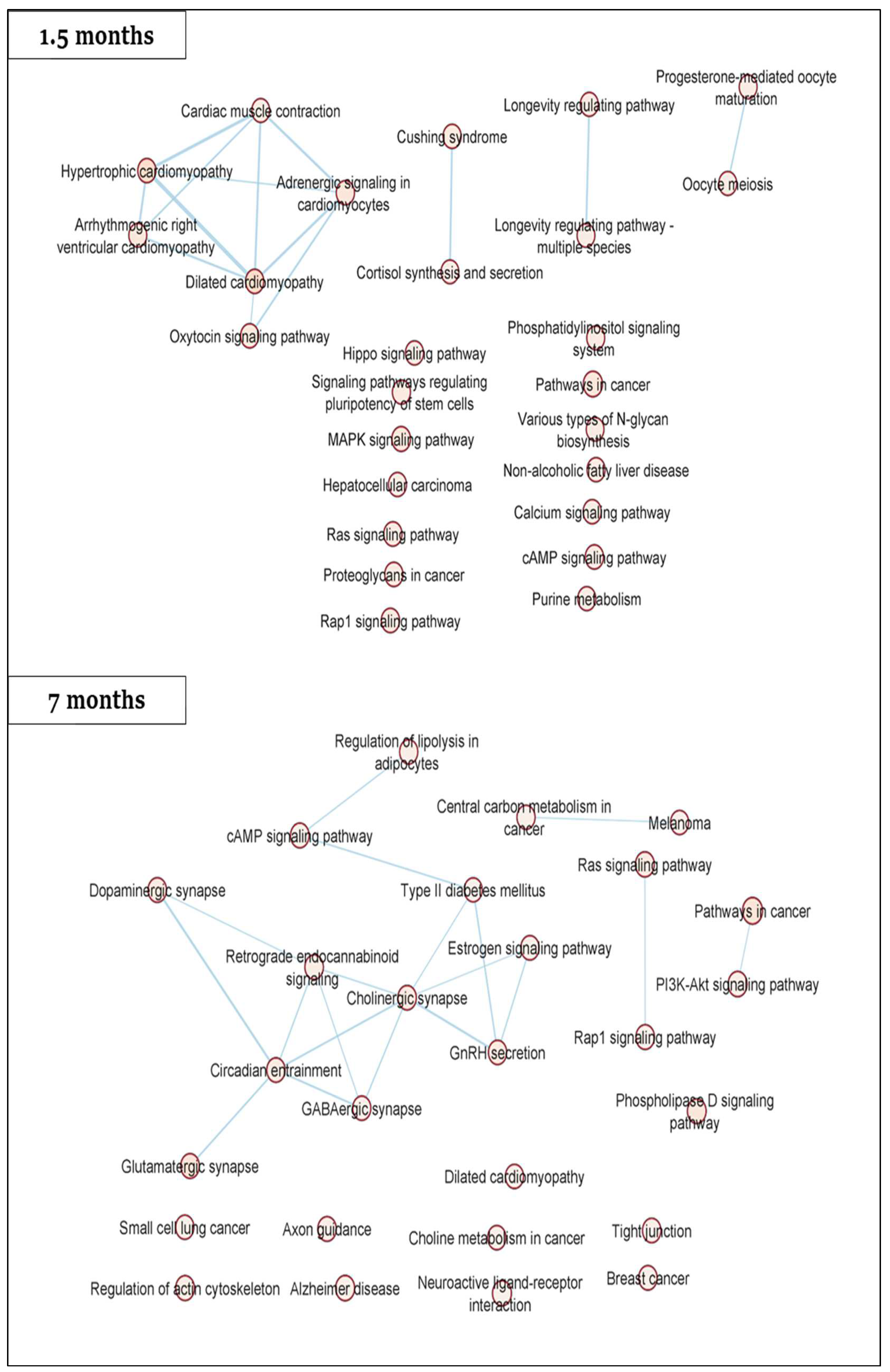

2.2. Gene-Specific DNA Methylation Analysis and Enriched Pathways of Rat DMRs

2.3. Hypomethylation of SLMAP at 1.5 Months Translates into a Dose-Dependent Increase in Gene Expression

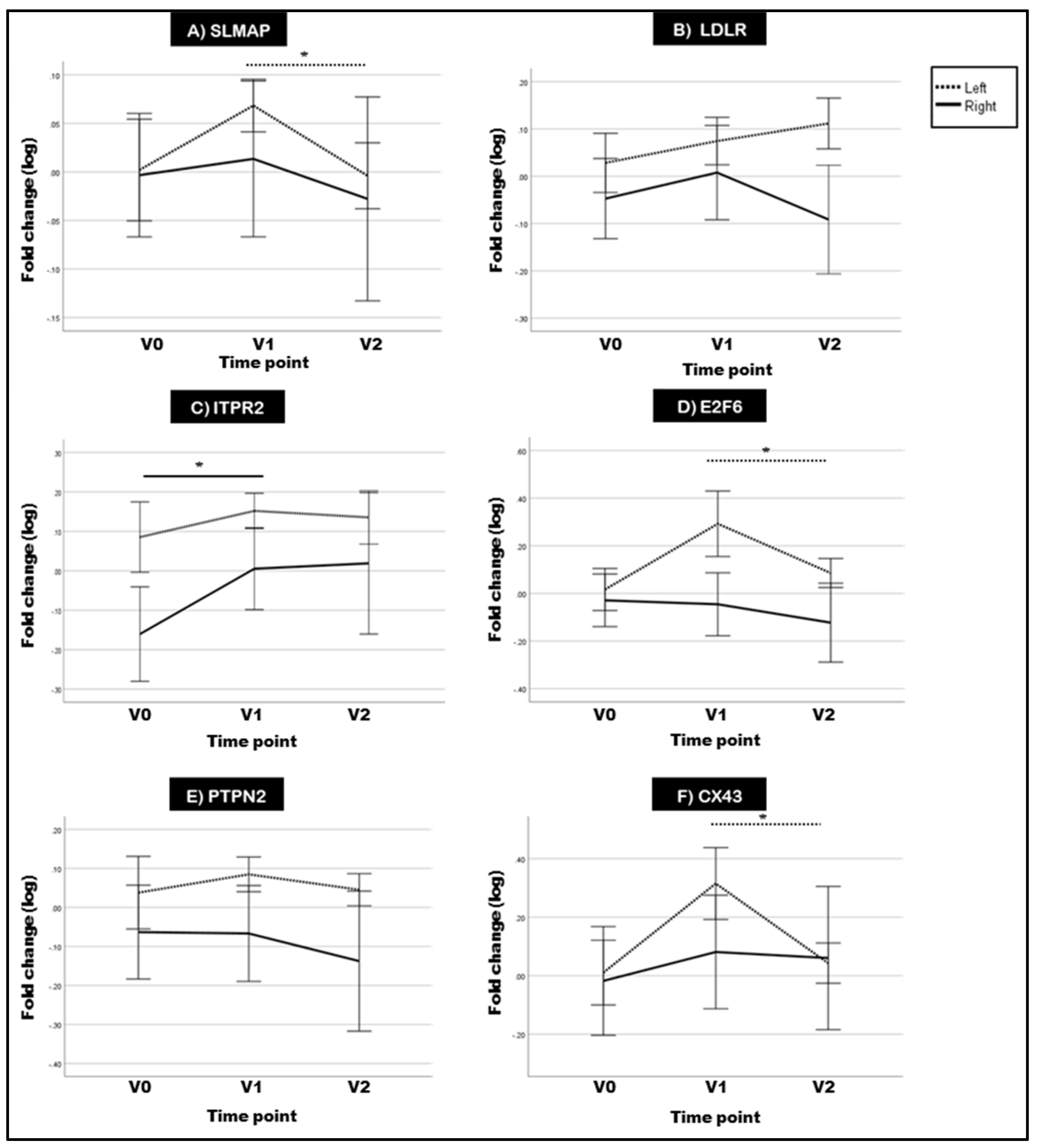

2.4. Two of the Selected Rat DMGs Show Altered Expression in BC Patient Blood

3. Discussion

Study Limitations

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals and Irradiation

4.2. DNA Extraction

4.3. Global DNA Methylation Using MethylFlash Global DNA Methylation

4.4. Gene-Specific DNA Methylation Analysis Using SureSelect Methyl-Seq

4.5. Pathway Analysis of Rat Differentially Methylated Regions (DMRs) by STRING-db

4.6. Investigation of Expression Alterations in DMRs Using Quantitative PCR

4.7. Correlation of Rat Global DNA Methylation and DMR Expression with Global Longitudinal Strain (GLS)

4.8. Investigating Gene Expression of Selected DMRs in Breast Cancer Patients’ Blood

4.8.1. Patient Selection

4.8.2. Radiotherapy Protocol

4.8.3. Blood Collection and Reverse Transcription qPCR

4.9. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Spetz, J.; Moslehi, J.; Sarosiek, K. Radiation-Induced Cardiovascular Toxicity: Mechanisms, Prevention, and Treatment. Curr. Treat. Options Cardiovasc. Med. 2018, 20, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baselet, B.; Sonveaux, P.; Baatout, S.; Aerts, A. Pathological effects of ionizing radiation: Endothelial activation and dysfunction. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2019, 76, 699–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darby, S.C.; Ewertz, M.; McGale, P.; Bennet, A.M.; Blom-Goldman, U.; Brønnum, D.; Correa, C.; Cutter, D.; Gagliardi, G.; Gigante, B.; et al. Risk of Ischemic Heart Disease in Women after Radiotherapy for Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 987–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallam, M.; Benotmane, M.A.; Baatout, S.; Guns, P.J.; Aerts, A. Radiation-induced cardiovascular disease: An overlooked role for DNA methylation? Epigenetics 2022, 17, 59–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, S.; Pathak, A.; Franck, D.; Latorzeff, I.; Jimenez, G.; Fondard, O.; Lapeyre, M.; Colombier, D.; Bruguiere, E.; Lairez, O.; et al. Early detection and prediction of cardiotoxicity after radiation therapy for breast cancer: The BACCARAT prospective cohort study. Radiat. Oncol. 2016, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, V.; Lairez, O.; Fondard, O.; Pathak, A.; Pinel, B.; Chevelle, C.; Franck, D.; Jimenez, G.; Camilleri, J.; Panh, L.; et al. Early detection of subclinical left ventricular dysfunction after breast cancer radiation therapy using speckle-tracking echocardiography: Association between cardiac exposure and longitudinal strain reduction (BACCARAT study). Radiat. Oncol. 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suelves, M.; Carrió, E.; Núñez-Álvarez, Y.; Peinado, M.A. DNA methylation dynamics in cellular commitment and differentiation. Brief. Funct. Genom. 2016, 15, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schübeler, D. Function and information content of DNA methylation. Nature 2015, 517, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chen, L.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wong, G. Identification of potential blood biomarkers for Parkinson’s disease by gene expression and DNA methylation data integration analysis. Clin. Epigenet. 2019, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.A.H.; Ansari, S.A.; Mensah-Brown, E.P.K.; Emerald, B.S. The role of DNA methylation in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin. Epigenet. 2020, 12, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, W.J.; Guanzon, D.; Ma, C.; Liew, Y.J.; Duesing, K.R.; Fung, K.Y.C.; Ross, J.P. DNA Methylation Cancer Biomarkers: Translation to the Clinic. Front. Genet. 2019, 0, 1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Sanlés, A.; Sayols-Baixeras, S.; Curcio, S.; Subirana, I.; Marrugat, J.; Elosua, R. DNA Methylation and Age-Independent Cardiovascular Risk, an Epigenome-Wide Approach. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2018, 38, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navas-Acien, A.; Domingo-Relloso, A.; Subedi, P.; Riffo-Campos, A.L.; Xia, R.; Gomez, L.; Haack, K.; Goldsmith, J.; Howard, B.V.; Best, L.G.; et al. Blood DNA Methylation and Incident Coronary Heart Disease: Evidence from the Strong Heart Study. JAMA Cardiol. 2021, 6, 1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, G.; Andersson, L.; Lauria, M.; Lindholm, M.; Fraga, M.F.; Villar-Garea, A.; Ballestar, E.; Esteller, M.; Zaina, S. DNA methylation polymorphisms precede any histological sign of atherosclerosis in mice lacking apolipoprotein E. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 29147–29154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabaei, S.; Tabaee, S.S. DNA methylation abnormalities in atherosclerosis. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2019, 47, 2031–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, D.; Sun, M.; You, L.; Lu, K.; Gao, L.; Hu, C.; Wu, S.; Chang, G.; Tao, H.; Zhang, D. DNA methylation and hydroxymethylation are associated with the degree of coronary atherosclerosis in elderly patients with coronary heart disease. Life Sci. 2019, 224, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, Y.; Horibe, H.; Oguri, M.; Sakuma, J.; Takeuchi, I.; Yasukochi, Y.; Kato, K.; Sawabe, M. Identification of novel hyper- or hypomethylated CpG sites and genes associated with atherosclerotic plaque using an epigenome-wide association study. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2018, 41, 2724–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Rai, P.S.; Upadhya, R.; Vishwanatha Shama Prasada, K.; Satish Rao, B.S.; Satyamoorthy, K. γ-radiation induces cellular sensitivity and aberrant methylation in human tumor cell lines. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2011, 87, 1086–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, S.; Simões, A.R.; Rocha, F.; Vala, I.S.; Pinto, A.T.; Ministro, A.; Poli, E.; Diegues, I.M.; Pina, F.; Benadjaoud, M.A.; et al. Molecular Changes in Cardiac Tissue as a New Marker to Predict Cardiac Dysfunction Induced By Radiotherapy. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 945521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, V.; Crijns, A.; Langendijk, J.; Spoor, D.; Vliegenthart, R.; Combs, S.E.; Mayinger, M.; Eraso, A.; Guedea, F.; Fiuza, M.; et al. Early detection of cardiovascular changes after radiotherapy for Breast cancer: Protocol for a European multicenter prospective cohort study (MEDIRAD EARLY HEART study). J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nader, M.; Westendorp, B.; Hawari, O.; Salih, M.; Stewart, A.F.R.; Leenen, F.H.H.; Tuana, B.S. Tail-anchored membrane protein SLMAP is a novel regulator of cardiac function at the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2012, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nader, M. The SLMAP/Striatin complex: An emerging regulator of normal and abnormal cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 858, 172491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franceschini, N.; Muallem, H.; Rose, K.M.; Boerwinkle, E.; Maeda, N. Low density lipoprotein receptor polymorphisms and the risk of coronary heart disease: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2009, 7, 496–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilker, E.; Mittleman, M.A.; Litonjua, A.A.; Poon, A.; Baccarelli, A.; Suh, H.; Wright, R.O.; Sparrow, D.; Vokonas, P.; Schwartz, J. Postural Changes in Blood Pressure Associated with Interactions between Candidate Genes for Chronic Respiratory Diseases and Exposure to Particulate Matter. Environ. Health Perspect. 2009, 117, 935–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankar, N.; de Tombe, P.P.; Mignery, G.A. Calcineurin-NFATc Regulates Type 2 Inositol 1,4,5-Trisphosphate Receptor (InsP3R2) Expression during Cardiac Remodeling. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 6188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.P.; Chang, S.Y.; Lin, C.J.; Chern, S.R.; Wu, P.S.; Chen, S.W.; Lai, S.T.; Chuang, T.Y.; Chen, W.L.; Yang, C.W.; et al. Prenatal diagnosis of a familial 5p14.3-p14.1 deletion encompassing CDH18, CDH12, PMCHL1, PRDM9 and CDH10 in a fetus with congenital heart disease on prenatal ultrasound. Taiwan J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 57, 734–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soemedi, R.; Wilson, I.J.; Bentham, J.; Darlay, R.; Töpf, A.; Zelenika, D.; Cosgrove, C.; Setchfield, K.; Thornborough, C.; Granados-Riveron, J.; et al. Contribution of global rare copy-number variants to the risk of sporadic congenital heart disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012, 91, 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Chen, J.; Qin, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhou, L. Mutations in voltage-gated L-type calcium channel: Implications in cardiac arrhythmia. Channels 2018, 12, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Sun, C.L.; Quiñones-Lombraña, A.; Singh, P.; Landier, W.; Hageman, L.; Mather, M.; Rotter, J.I.; Taylor, K.D.; Chen, Y.D.I.; et al. CELF4 variant and anthracycline-related cardiomyopathy: A children’s oncology group genome-wide association study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 863–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movassagh, M.; Bicknell, K.A.; Brooks, G. Characterisation and regulation of E2F-6 and E2F-6b in the rat heart: A potential target for myocardial regeneration? J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2006, 58, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westendorp, B.; Major, J.L.; Nader, M.; Salih, M.; Leenen, F.H.H.; Tuana, B.S. The E2F6 repressor activates gene expression in myocardium resulting in dilated cardiomyopathy. FASEB J. 2012, 26, 2569–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Gu, T.X.; Yu, F.M.; Zhang, G.W.; Zhao, Y. Overexpression of miR-210 promotes the potential of cardiac stem cells against hypoxia. Scand. Cardiovasc. J. 2018, 52, 367–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locquet, M.; Spoor, D.; Crijns, A.; van der Harst, P.; Eraso, A.; Guedea, F.; Fiuza, M.; Santos, S.C.R.; Combs, S.; Borm, K.; et al. Subclinical Left Ventricular Dysfunction Detected by Speckle-Tracking Echocardiography in Breast Cancer Patients Treated with Radiation Therapy: A Six-Month Follow-Up Analysis (MEDIRAD EARLY-HEART study). Front. Oncol. 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, R.; Vromans, E.; Anang, D.C.; Goetschalckx, I.; Hoorelbeke, D.; Decrock, E.; Baatout, S.; Leybaert, L.; Aerts, A. Connexin43 Hemichannel Targeting With TAT-Gap19 Alleviates Radiation-Induced Endothelial Cell Damage. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piroth, M.D.; Baumann, R.; Budach, W.; Dunst, J.; Feyer, P.; Fietkau, R.; Haase, W.; Harms, W.; Hehr, T.; Krug, D.; et al. Heart toxicity from breast cancer radiotherapy: Current findings, assessment, and prevention. Strahlenther. Onkol. 2019, 195, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antwih, D.A.; Gabbara, K.M.; Lancaster, W.D.; Ruden, D.M.; Zielske, S.P. Radiation-induced epigenetic DNA methylation modification of radiation-response pathways. Epigenetics 2013, 8, 839–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koturbash, I.; Jadavji, N.M.; Kutanzi, K.; Rodriguez-Juarez, R.; Kogosov, D.; Metz, G.A.S.; Kovalchuk, O. Fractionated low-dose exposure to ionizing radiation leads to DNA damage, epigenetic dysregulation, and behavioral impairment. Environ. Epigenet. 2016, 2, dvw025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loree, J.; Koturbash, I.; Kutanzi, K.; Baker, M.; Pogribny, I.; Kovalchuk, O. Radiation-induced molecular changes in rat mammary tissue: Possible implications for radiation-induced carcinogenesis. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2006, 82, 805–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jangiam, W.; Udomtanakunchai, C.; Reungpatthanaphong, P.; Tungjai, M.; Honikel, L.; Gordon, C.R.; Rithidech, K.N. Late Effects of Low-Dose Radiation on the Bone Marrow, Lung, and Testis Collected from the Same Exposed BALB/cJ Mice. Dose Response 2018, 16, 1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhmann, C.; Weichenhan, D.; Rehli, M.; Plass, C.; Schmezer, P.; Popanda, O. DNA methylation changes in cells regrowing after fractioned ionizing radiation. Radiother. Oncol. 2011, 101, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maierhofer, A.; Flunkert, J.; Dittrich, M.; Müller, T.; Schindler, D.; Nanda, I.; Haaf, T. Analysis of global DNA methylation changes in primary human fibroblasts in the early phase following X-ray irradiation. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zhang, M.; An, G.; Ma, Q. LncRNA TUG1 acts as a tumor suppressor in human glioma by promoting cell apoptosis. Exp. Biol. Med. 2016, 241, 644–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.-X.; Fei, X.-R.; Dong, Y.-F.; Cheng, C.-D.; Yang, Y.; Deng, X.-F.; Huang, H.-L.; Niu, W.-X.; Zhou, C.-X.; Xia, C.-Y.; et al. The long non-coding RNA CRNDE acts as a ceRNA and promotes glioma malignancy by preventing miR-136-5p-mediated downregulation of Bcl-2 and Wnt2. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 88163–88178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, C.-X. Relationship between global DNA methylation and hydroxymethylation levels in peripheral blood of elderly patients with myocardial infarction and the degree of coronary atherosclerosis. J. Shanghai Jiaotong Univ. Med. Sci. 2018, 12, 769–774. [Google Scholar]

- Guarrera, S.; Fiorito, G.; Onland-Moret, N.C.; Russo, A.; Agnoli, C.; Allione, A.; Di Gaetano, C.; Mattiello, A.; Ricceri, F.; Chiodini, P.; et al. Gene-specific DNA methylation profiles and LINE-1 hypomethylation are associated with myocardial infarction risk. Clin. Epigenet. 2015, 7, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Chen, L.-F.; Li, J.; Chen, J.; Tian, X.-L.; Wang, H.; Mei, Z.-J.; Xie, C.-H.; Zhong, Y.-H. Altered DNA Methylation and Gene Expression Profiles in Radiation-Induced Heart Fibrosis of Sprague-Dawley Rats. Radiat. Res. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Huang, Y.; Wu, J. Identify cross talk between circadian rhythm and coronary heart disease by multiple correlation analysis. J. Comput. Biol. 2018, 25, 1312–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, E.M.; Williams, I.I.I.W.P.; Kriegsfeld, L.J. Aging in the circadian system: Considerations for health, disease prevention and longevity. Exp. Gerontol. 2009, 44, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, X.; Kong, W. Endothelial tight junctions and their regulatory signaling pathways in vascular homeostasis and disease. Cell. Signal. 2020, 66, 109485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaev, V.O.; Moshkov, A.; Lyon, A.R.; Miragoli, M.; Novak, P.; Paur, H.; Lohse, M.J.; Korchev, Y.E.; Harding, S.E.; Gorelik, J. β2-adrenergic receptor redistribution in heart failure changes cAMP compartmentation. Science 2010, 327, 1653–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Communal, C.; Colucci, W.S. The control of cardiomyocyte apoptosis via the beta-adrenergic signaling pathways. Arch. Mal. Coeur Vaiss 2005, 98, 236–241. [Google Scholar]

- Sequeira, V.; Nijenkamp, L.L.A.M.; Regan, J.A.; van der Velden, J. The physiological role of cardiac cytoskeleton and its alterations in heart failure. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Biomembr. 2014, 1838, 700–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, M. Longevity genes, cardiac ageing, and the pathogenesis of cardiomyopathy: Implications for understanding the effects of current and future treatments for heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 3856–3861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhles, M.M.; Trifirò, G.; Dieleman, J.P.; Haag, M.D.; van Soest, E.M.; Verhamme, K.M.C.; Mazzaglia, G.; Herings, R.; de Luise, C.; Ross, D.; et al. The risk of new onset heart failure associated with dopamine agonist use in Parkinson’s disease. Pharmacol. Res. 2012, 65, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, T.; Sumida, T.S.; Nomura, S.; Satoh, M.; Higo, T.; Ito, M.; Ko, T.; Fujita, K.; Sweet, M.E.; Sanbe, A.; et al. Cardiac dopamine D1 receptor triggers ventricular arrhythmia in chronic heart failure. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azimzadeh, O.; Moertl, S.; Ramadan, R.; Baselet, B.; Laiakis, E.C.; Sebastian, S.; Beaton, D.; Hartikainen, J.M.; Kaiser, J.C.; Beheshti, A.; et al. Application of radiation omics in the development of adverse outcome pathway networks: An example of radiation-induced cardiovascular disease. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2022, 98, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juárez Olguín, H.; Calderón Guzmán, D.; Hernández García, E.; Barragán Mejía, G. The role of dopamine and its dysfunction as a consequence of oxidative stress. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2016, 2016, 9730467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbi, G.; Conti, V.; Russomanno, G.; Longobardi, G.; Furgi, G.; Filippelli, A.; Ferrara, N. Adrenergic signaling and oxidative stress: A role for sirtuins? Front. Physiol. 2013, 4, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilking, M.; Ndiaye, M.; Mukhtar, H.; Ahmad, N. Circadian rhythm connections to oxidative stress: Implications for human health. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013, 19, 192–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, L.; Cinato, M.; Mardani, I.; Miljanovic, A.; Arif, M.; Koh, A.; Lindbom, M.; Laudette, M.; Bollano, E.; Omerovic, E.; et al. Glucosylceramide synthase deficiency in the heart compromises β1-adrenergic receptor trafficking. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 4481–4492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, R.; Baatout, S.; Aerts, A.; Leybaert, L. The role of connexin proteins and their channels in radiation-induced atherosclerosis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2021, 78, 3087–3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gredilla, R.; Barja, G. Minireview: The Role of Oxidative Stress in Relation to Caloric Restriction and Longevity. Endocrinology 2005, 146, 3713–3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzzo, R.M.; Salih, M.; Moore, E.D.; Tuana, B.S. Molecular properties of cardiac tail-anchored membrane protein SLMAP are consistent with structural role in arrangement of excitation-contraction coupling apparatus. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2005, 288, 1810–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazarenko, M.S.; Markov, A.V.; Lebedev, I.N.; Freidin, M.B.; Sleptcov, A.A.; Koroleva, I.A.; Frolov, A.V.; Popov, V.A.; Barbarash, O.L.; Puzyrev, V.P. A Comparison of Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Patterns between Different Vascular Tissues from Patients with Coronary Heart Disease. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0122601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mia, M.M.; Singh, M.K. The Hippo Signaling Pathway in Cardiac Development and Diseases. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, S.; Yang, G.; Zablocki, D.; Liu, J.; Hong, C.; Kim, S.J.; Soler, S.; Odashima, M.; Thaisz, J.; Yehia, G.; et al. Activation of Mst1 causes dilated cardiomyopathy by stimulating apoptosis without compensatory ventricular myocyte hypertrophy. J. Clin. Investig. 2003, 111, 1463–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertini, E.; Oka, T.; Sudol, M.; Strano, S.; Blandino, G. At the crossroad between transformation and tumor suppression. Cell Cycle 2009, 8, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.A. Functions of DNA methylation: Islands, start sites, gene bodies and beyond. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2012, 13, 484–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jjingo, D.; Conley, A.B.; Yi, S.V.; Lunyak, V.V.; Jordan, I.K. On the presence and role of human gene-body DNA methylation. Oncotarget 2012, 3, 462–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Han, H.; DeCarvalho, D.D.; Lay, F.D.; Jones, P.A.; Liang, G. Gene body methylation can alter gene expression and is a therapeutic target in cancer. Cancer Cell 2014, 26, 577–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spainhour, J.C.G.; Lim, H.S.; Yi, S.V.; Qiu, P. Correlation Patterns Between DNA Methylation and Gene Expression in The Cancer Genome Atlas. Cancer Inform. 2019, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beltrami, C.M.; dos Reis, M.B.; Barros-Filho, M.C.; Marchi, F.A.; Kuasne, H.; Pinto, C.A.L.; Ambatipudi, S.; Herceg, Z.; Kowalski, L.P.; Rogatto, S.R. Integrated data analysis reveals potential drivers and pathways disrupted by DNA methylation in papillary thyroid carcinomas. Clin. Epigenet. 2017, 9, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luan, Z.M.; Zhang, H.; Qu, X.L. Prediction efficiency of PITX2 DNA methylation for prostate cancer survival. Genet. Mol. Res. 2016, 15, 6750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Feng, Z.-H.; Sun, H.; Zhao, Z.-H.; Yang, S.-B.; Yang, P. The blood genome-wide DNA methylation analysis reveals novel epigenetic changes in human heart failure. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2017, 21, 1828–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varley, K.E.; Gertz, J.; Bowling, K.M.; Parker, S.L.; Reddy, T.E.; Pauli-Behn, F.; Cross, M.K.; Williams, B.A.; Stamatoyannopoulos, J.A.; Crawford, G.E.; et al. Dynamic DNA methylation across diverse human cell lines and tissues. Genome Res. 2013, 23, 555–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulis, M.; Heath, S.; Bibikova, M.; Queirós, A.C.; Navarro, A.; Clot, G.; Martínez-Trillos, A.; Castellano, G.; Brun-Heath, I.; Pinyol, M.; et al. Epigenomic analysis detects widespread gene-body DNA hypomethylation in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Nat. Genet. 2012, 44, 1236–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maunakea, A.K.; Nagarajan, R.P.; Bilenky, M.; Ballinger, T.J.; Dsouza, C.; Fouse, S.D.; Johnson, B.E.; Hong, C.; Nielsen, C.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Conserved role of intragenic DNA methylation in regulating alternative promoters. Nature 2010, 466, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Wu, F.; Wang, F.; Cai, K.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Q.; Zhao, X.; Gui, Y.; Li, Q. Impact of DNA methyltransferase inhibitor 5-azacytidine on cardiac development of zebrafish in vivo and cardiomyocyte proliferation, apoptosis, and the homeostasis of gene expression in vitro. J. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 120, 17459–17471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Q.; Li, A.; Chen, X.; Qin, Y.; Sun, X.; Li, Y.; Yue, E.; Wang, C.; Ding, X.; Yan, Y.; et al. Overexpression of miR-135b attenuates pathological cardiac hypertrophy by targeting CACNA1C. Int. J. Cardiol. 2018, 269, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, W.; Du, J.; Wei, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Hou, Y. Altered long non-coding RNA expression profile in rabbit atria with atrial fibrillation: TCONS_00075467 modulates atrial electrical remodeling by sponging miR-328 to regulate CACNA1C. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2017, 108, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deplus, R.; Blanchon, L.; Rajavelu, A.; Boukaba, A.; Defrance, M.; Luciani, J.; Rothé, F.; Dedeurwaerder, S.; Denis, H.; Brinkman, A.B.; et al. Regulation of DNA Methylation Patterns by CK2-Mediated Phosphorylation of Dnmt3a. Cell Rep. 2014, 8, 743–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinberg, D.N.; Rosenbaum, P.; Chen, X.; Barrows, D.; Horth, C.; Marunde, M.R.; Popova, I.K.; Gillespie, Z.B.; Keogh, M.-C.; Lu, C.; et al. Two competing mechanisms of DNMT3A recruitment regulate the dynamics of de novo DNA methylation at PRC1-targeted CpG islands. Nat. Genet. 2021, 53, 794–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, A.; Stockwell, P.A.; Rodger, E.J.; Duncan, E.J.; Parry, M.F.; Weeks, R.J.; Morison, I.M. Genome-wide DNA methylation map of human neutrophils reveals widespread inter-individual epigenetic variation. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 17328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, M.N.; Volta, M.; Pidsley, R.; Lunnon, K.; Dixit, A.; Lovestone, S.; Coarfa, C.; Harris, R.A.; Milosavljevic, A.; Troakes, C.; et al. Functional annotation of the human brain methylome identifies tissue-specific epigenetic variation across brain and blood. Genome Biol. 2012, 13, R43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Rocha, C.; Zaina, S.; Lund, G. Is Any Cardiovascular Disease-Specific DNA Methylation Biomarker within Reach? Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2020, 22, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veenstra, C.; Karlsson, E.; Mirwani, S.M.; Nordenskjöld, B.; Fornander, T.; Pérez-Tenorio, G.; Stål, O. The effects of PTPN2 loss on cell signalling and clinical outcome in relation to breast cancer subtype. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 145, 1845–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nader, M.; Alsolme, E.; Alotaibi, S.; Alsomali, R.; Bakheet, D.; Dzimiri, N. SLMAP-3 is downregulated in human dilated ventricles and its overexpression promotes cardiomyocyte response to adrenergic stimuli by increasing intracellular calcium. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2019, 97, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimzadeh, O.; Azizova, T.; Merl-Pham, J.; Blutke, A.; Moseeva, M.; Zubkova, O.; Anastasov, N.; Feuchtinger, A.; Hauck, S.M.; Atkinson, M.J. Chronic occupational exposure to ionizing radiation induces alterations in the structure and metabolism of the heart: A proteomic analysis of human formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) cardiac tissue. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natesan, S.; Maxwell, J.T.; Hale, P.R.; Mignery, G.A. Abstract 298: CaMKII-Mediated Phosphorylation of InsP3R2 Activates Hypertrophic Gene Transcription. Circ. Res. 2012, 111, A298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harzheim, D.; Talasila, A.; Movassagh, M.; Foo, R.S.-Y.; Figg, N.; Bootman, M.D.; Roderick, H.L. Elevated InsP3R expression underlies enhanced calcium fluxes and spontaneous extra-systolic calcium release events in hypertrophic cardiac myocytes. Channels 2010, 4, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santulli, G.; Chen, B.; Forrester, F.; Wu, H.; Reiken, S.; Marks, A.R. Abstract 16984: Role of Inositol 1,4,5-Triphosphate Receptor 2 in Post-Ischemic Heart Failure. Circulation 2014, 130, A16984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberley, M.J.; Inman, D.R.; Farnham, P.J. E2F6 negatively regulates BRCA1 in human cancer cells without methylation of histone H3 on lysine 9. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 42466–42476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Major, J.L.; Dewan, A.; Salih, M.; Leddy, J.J.; Tuana, B.S. E2F6 Impairs Glycolysis and Activates BDH1 Expression Prior to Dilated Cardiomyopathy. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azimzadeh, O.; Azizova, T.; Merl-Pham, J.; Subramanian, V.; Bakshi, M.V.; Moseeva, M.; Zubkova, O.; Hauck, S.M.; Anastasov, N.; Atkinson, M.J.; et al. A dose-dependent perturbation in cardiac energy metabolism is linked to radiation-induced ischemic heart disease in Mayak nuclear workers. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 9067–9078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verheyde, J.; de Saint-Georges, L.; Leyns, L.; Benotmane, M.A. The Role of Trp53 in the Transcriptional Response to Ionizing Radiation in the Developing Brain. DNA Res. 2006, 13, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáez, J.C.; Retamal, M.A.; Basilio, D.; Bukauskas, F.F.; Bennett, M.V.L. Connexin-based gap junction hemichannels: Gating mechanisms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2005, 1711, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.W.; Burger, F.; Pelli, G.; Mach, F.; Kwak, B.R. Dual benefit of reduced Cx43 on atherosclerosis in LDL receptor-deficient mice. Cell Commun. Adhes. 2003, 10, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, B.R.; Veillard, N.; Pelli, G.; Mulhaupt, F.; James, R.W.; Chanson, M.; Mach, F. Reduced connexin43 expression inhibits atherosclerotic lesion formation in low-density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice. Circulation 2003, 107, 1033–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, R.; Vromans, E.; Anang, D.C.; Decrock, E.; Mysara, M.; Monsieurs, P.; Baatout, S.; Leybaert, L.; Aerts, A. Single and fractionated ionizing radiation induce alterations in endothelial connexin expression and channel function. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Sahni, N.S.; Tibshirani, R.; Skaane, P.; Urdal, P.; Berghagen, H.; Jensen, M.; Kristiansen, L.; Moen, C.; Sharma, P.; et al. Early detection of breast cancer based on gene-expression patterns in peripheral blood cells. Breast. Cancer Res. 2005, 7, R634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.C.; Delgado-Cruzata, L.; Flom, J.D.; Kappil, M.; Ferris, J.S.; Liao, Y.; Santella, R.M.; Terry, M.B. Global methylation profiles in DNA from different blood cell types. Epigenetics 2011, 6, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Choi, J.Y.; Lee, K.M.; Sung, H.; Park, S.K.; Oze, I.; Pan, K.F.; You, W.C.; Chen, Y.X.; Fang, J.Y.; et al. DNA Methylation in Peripheral Blood: A Potential Biomarker for Cancer Molecular Epidemiology. J. Epidemiol. 2012, 22, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zemmour, H.; Planer, D.; Magenheim, J.; Moss, J.; Neiman, D.; Gilon, D.; Korach, A.; Glaser, B.; Shemer, R.; Landesberg, G.; et al. Non-invasive detection of human cardiomyocyte death using methylation patterns of circulating DNA. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Ma, J.; Deng, H.; Huang, S.J.; Rao, J.; Xu WBin Huang, J.S.; Sun, S.Q.; Zhang, L. Cardiac-specific methylation patterns of circulating DNA for identification of cardiomyocyte death. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2020, 20, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheiermann, C.; Frenette, P.S.; Hidalgo, A. Regulation of leucocyte homeostasis in the circulation. Cardiovasc. Res. 2015, 107, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.C.; Zhang, H.P.; Kong, F.Q.; Zheng, H.; Yang, C.; He, Y.Y.; Wang, Y.H.; Yang, A.N.; Tian, J.; Yang, X.L.; et al. Integration of gene expression and DNA methylation profiles provides a molecular subtype for risk assessment in atherosclerosis. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 13, 4791–4799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agha, G.; Mendelson, M.M.; Ward-Caviness, C.K.; Joehanes, R.; Huan, T.X.; Gondalia, R.; Salfati, E.; Brody, J.A.; Fiorito, G.; Bressler, J.; et al. Blood Leukocyte DNA Methylation Predicts Risk of Future Myocardial Infarction and Coronary Heart Disease. Circulation 2019, 140, 645–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, T.; Joehanes, R.; Song, C.; Peng, F.; Guo, Y.; Mendelson, M.; Yao, C.; Liu, C.; Ma, J.; Richard, M.; et al. Genome-wide identification of DNA methylation QTLs in whole blood highlights pathways for cardiovascular disease. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.R.; Ryu, D.S.; Park, S.J.; Choe, S.H.; Cho, H.M.; Lee, S.R.; Kim, S.U.; Kim, Y.H.; Huh, J.W. Successful application of human-based methyl capture sequencing for methylome analysis in non-human primate models. BMC Genom. 2018, 19, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, C.; Zhang, X.; Aouizerat, B.E.; Xu, K. Comparison of methylation capture sequencing and Infinium MethylationEPIC array in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Epigenet. Chromatin 2020, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, J.L.; Cox, O.H.; Seifuddin, F.; Marque, L.; Tamashiro, K.L.; Zandi, P.P.; Wand, G.S.; Lee, R.S. A Rat Methyl-Seq Platform to Identify Epigenetic Changes Associated with Stress Exposure. J. Vis. Exp. 2018, 140, 58617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seifuddin, F.; Wand, G.; Cox, O.; Pirooznia, M.; Moody, L.; Yang, X.; Tai, J.; Boersma, G.; Tamashiro, K.; Zandi, P.; et al. Genome-wide Methyl-Seq analysis of blood-brain targets of glucocorticoid exposure. Epigenetics 2017, 12, 637–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Gable, A.L.; Nastou, K.C.; Lyon, D.; Kirsch, R.; Pyysalo, S.; Doncheva, N.T.; Legeay, M.; Fang, T.; Jensen, L.J.; et al. The STRING database in 2021: Customizable protein-protein networks, and functional characterization of user-uploaded gene/measurement sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A Software Environment for Integrated Models of Biomolecular Interaction Networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinert, T.; Modin, C.; Castano, F.M.; Lamy, P.; Wojdacz, T.K.; Hansen, L.L.; Wiuf, C.; Borre, M.; Dyrskjøt, L.; Ørntoft, T.F. Comprehensive genome methylation analysis in bladder cancer: Identification and validation of novel methylated genes and application of these as urinary tumor markers. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 5582–5592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernoff, M.B.; Demanelis, K.; Gillard, M.; Delgado, D.; Griend DJVander Pierce, B.L. Abstract 160: Identifying differential methylation patterns of benign and tumor prostate tissue in African American and European American prostate cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2020, 80, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarr, I.S.; McCann, E.P.; Benyamin, B.; Peters, T.J.; Twine, N.A.; Zhang, K.Y.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, Z.H.; Rowe, D.B.; Nicholson, G.A.; et al. Monozygotic twins and triplets discordant for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis display differential methylation and gene expression. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, C.L.; Jensen, J.L.; Ørntoft, T.F. Normalization of real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR data: A model-based variance estimation approach to identify genes suited for normalization, applied to bladder and colon cancer data sets. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 5245–5250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| DMR | Connection to Cardiac Function/Disease | Methylation State after 27.6 Gy FI Dose Relative to Sham Irradiated Rats (p-Value < 0.05) |

|---|---|---|

| SLMAP (Sarcolemma Associated Protein) | SLMAP is a component of cardiac membranes involved in excitation-contraction (E-C) coupling and its perturbation results in progressive deterioration of cardiac electrophysiology and function [21]. | Hypomethylated at 1.5 months after irradiation |

| SLMAP also interacts with cardiac myosin suggesting a direct role in controlling cardiomyocyte contraction [22]. | ||

| LDLR (Low Density Lipoprotein Receptor) | Knockouts and/or mutations in LDLR lead to ineffective clearance of serum low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and contribute to premature atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease [23]. | Hypomethylated at 7 months after irradiation |

| ITPR2 (Inositol 1,4,5-Trisphosphate Receptor Type 2) | Certain polymorphs of ITPR2 have been associated with higher systolic blood pressure. ITPR2 is expressed widely in myocytes with altered expression in heart failure [24,25]. | Hypomethylated at 7 months after irradiation |

| CDH18 (Cadherin 18) | A deletion involving CDH18 was reported to be found in a case of congenital heart disease [26]. | Hypomethylated at 1.5 months after irradiation |

| In a study involving copy-number variants and the risk of sporadic congenital heart disease, rare deletions in study participants with congenital heart disease were in found in a number of genes including CDH18 [27]. | ||

| CACNA1C (Calcium Voltage-Gated Channel Subunit Alpha1 C) | CACNA1C is a part of voltage-gated L-type calcium channel gene which plays an important role in cardiac electrical excitation [28]. | Hypomethylated at 1.5 and 7 months after irradiation |

| CELF4 (CUGBP Elav-like family member 4) | A polymorphism of CELF4 has been reported to have a modifying effect on anthracycline-related cardiomyopathy [29]. | Hypomethylated at 7 months after irradiation |

| E2F6 (E2F Transcription Factor 6) | E2F6 is a cell cycle regulator, abrogation of expression of E2F6 in neonatal cardiac myocytes leads to a significant decrease in myocyte viability suggesting a role in myocardial regeneration [30,31]. | Hypomethylated at 1.5 months after irradiation |

| Forced E2F6 expression activates gene expression in myocardium resulting in dilated cardiomyopathy [31]. | ||

| PTPN2 (Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase Non-Receptor Type 2) | Decreased expression of PTPN2 through activation of miR-201 leads to attenuation of apoptosis and improvement of migration of cardiac stem cells exposed to hypoxia which would in turn increases their potential to repair the injured myocardium [32]. | Hypomethylated at 7 months after irradiation |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sallam, M.; Mysara, M.; Benotmane, M.A.; Tamarat, R.; Santos, S.C.R.; Crijns, A.P.G., 5; Spoor, D.; Van Nieuwerburgh, F.; Deforce, D.; Baatout, S.; et al. DNA Methylation Alterations in Fractionally Irradiated Rats and Breast Cancer Patients Receiving Radiotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 16214. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232416214

Sallam M, Mysara M, Benotmane MA, Tamarat R, Santos SCR, Crijns APG 5, Spoor D, Van Nieuwerburgh F, Deforce D, Baatout S, et al. DNA Methylation Alterations in Fractionally Irradiated Rats and Breast Cancer Patients Receiving Radiotherapy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022; 23(24):16214. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232416214

Chicago/Turabian StyleSallam, Magy, Mohamed Mysara, Mohammed Abderrafi Benotmane, Radia Tamarat, Susana Constantino Rosa Santos, Anne P. G. Crijns 5, Daan Spoor, Filip Van Nieuwerburgh, Dieter Deforce, Sarah Baatout, and et al. 2022. "DNA Methylation Alterations in Fractionally Irradiated Rats and Breast Cancer Patients Receiving Radiotherapy" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 23, no. 24: 16214. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232416214

APA StyleSallam, M., Mysara, M., Benotmane, M. A., Tamarat, R., Santos, S. C. R., Crijns, A. P. G., 5, Spoor, D., Van Nieuwerburgh, F., Deforce, D., Baatout, S., Guns, P.-J., Aerts, A., & Ramadan, R. (2022). DNA Methylation Alterations in Fractionally Irradiated Rats and Breast Cancer Patients Receiving Radiotherapy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(24), 16214. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232416214