Candidate Biological Markers for Social Anxiety Disorder: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

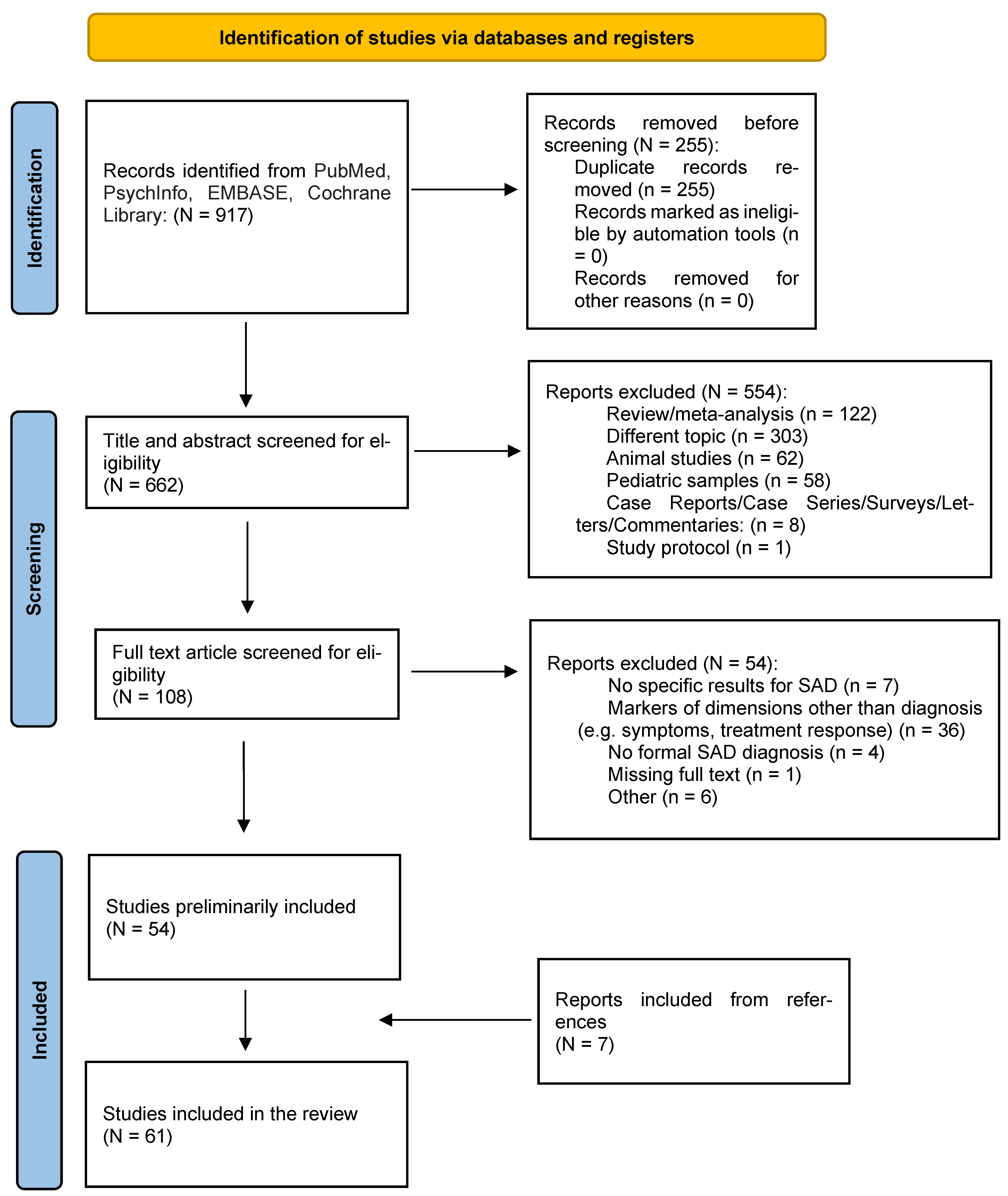

2. Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Genetics

| BIOMARKER TYPE | REFERENCE | BIOMARKER UNDER STUDY | STUDY DESIGN | SAMPLE SIZE | FINDINGS | QUALITY SCORE 1 | COHEN’S d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetics | [33] | SLC6A4 | SNPs genotyping (SAD vs. HC) | 1125 | Two SNPs with nominal significance: - rs818702 (p = 0.032) - rs140701 (p = 0.048) After Bonferroni’s correction: SAD = HC (p > 0.05) | Moderate | / |

| [34] 2 | 5HTT (SLC6A4), 5HT2AR | Linkage analysis (first-degree family members of probands affected by SAD) | 17 families (122 members) | No linkage to SAD (p > 0.05) | Moderate | / | |

| [35] 2 | DRD2, DRD3, DRD4, DAT1 | Linkage analysis (families of probands affected by SAD) | 17 families (122 members) | No linkage to SAD (p > 0.05) | Moderate | / | |

| [36] | Genome | Genome-wide linkage scan (families of probands affected by Panic Disorder) | 17 families (163 members) | Linkage to SAD for chromosome 16 (p = 0.0003) | Moderate | d = 0.165 | |

| [37] | MANEA | Multi-stage association study (SAD vs. HC) | 131 | C allele of the MANEA (rs1133503*C) (p = 0.004) | Moderate | d = 0.422 | |

| Epigenetics | [22] | OTXR methylation | Multilevel epigenetic study (SAD vs. HC) | 220 | ↓ OXTR methylation at CpG3 (Chr3: 8 809 437) (p < 0.001) | Strong | d = 0.535 |

| [45] | Genome methylation | Epigenome-wide association study (SAD vs. HC) | 143 | DMRs within SLC43A2 (p < 5 × 10−4) and TNXB (p < 3 × 10−26) | Weak | NA |

3.2. Epigenetics

3.3. Endocrine Biomarkers

3.3.1. Cortisol

| HORMONAL SYSTEM | REFERENCE | BIOMARKER UNDER STUDY | STUDY DESIGN | SAMPLE SIZE | FINDINGS | QUALITY SCORE 1 | COHEN’S d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cortisol and sAA | [53] | Salivary cortisol, plasma cortisol, sAA, prolactin | Cross-sectional (SAD vs. HC) Secretion after TSST | 166 | SAD = HC: - Salivary cortisol stress response (p > 0.131) - Plasma cortisol stress response (p = 0.084) - sAA stress response (p > 0.343) - Prolactin stress response (F < 1) - Basal hair cortisol levels (p = 0.918) | Moderate | / |

| [54] | sAA, salivary cortisol | Cross sectional (SAD vs. HC) Response to electrical stimulation | 112 | sAA: SAD > HC at all-time points (p < 0.01) Salivary cortisol: SAD = HC at all-time points (p > 0.05) | Moderate | sAA: d = 0.576 | |

| [55] | UFC, post-dexamethasone plasma cortisol | Cross-sectional (SAD vs. HC) | 54 patients (UFC); 64 patients (plasma cortisol) | SAD = HC - UFC (p = 0.15) - Post-dexamethasone (p = 0.37) | Weak | / | |

| [56] | sAA, salivary cortisol Measured in non-stressed conditions: - after awakening - during the day (including late evening) - after a low dose (0.5 mg) of dexamethasone | Cross-sectional (SAD vs. HC) | 86 | SAD = HC - Awakening sAA (p = 0.114) - Salivary cortisol (awakening, diurnal, late evening) (p = 0.201) - Post-dexamethasone salivary cortisol (p = 0.256) SAD > HC: - Diurnal sAA (p = 0.044) - Post-dexamethasone sAA (p = 0.040) | Moderate | Diurnal sAA: d = 0.508 Post-dexamethasone sAA: d = 0.518 | |

| [57] | Salivary cortisol - 1-h cortisol awakening response - evening cortisol - cortisol response after 0.5 mg of dexamethasone ingestion | Cross sectional (ADs vs. HC) | Current: 140 SAD patients Remitted: 487 SAD patients | SAD = HC (p > 0.05) | Moderate | / | |

| [59] | Plasma ACTH, plasma cortisol, salivary cortisol | Cross-sectional (SAD vs. HC) Secretion after TSST | 70 | Baseline ACTH, plasma and salivary cortisol: SAD = HC (p > 0.05) ACTH secretion pattern and AUCg: SAD = HC (p > 0.05) Plasma cortisol: SAD < HC - secretion pattern (p = 0.011) - AUCg (p = 0.007) Salivary cortisol: - secretion pattern SAD = HC (p > 0.05); - AUCg, SAD < HC (p = 0.007) | Strong | Plasma cortisol: d = 0.165 (secretion pattern); d = 0.229 (AUCg) Salivary cortisol: d = 0.229 (AUCg) | |

| [60] | Plasma cortisol, plasma ACTH | Cross-sectional (SAD vs. HC) Secretion after stressors: - mental arithmetic - short-term memory test in front of an audience | 30 | Baseline ACTH and cortisol: SAD = HC (p > 0.05) Delta max 2 cortisol response: SAD > HC (p < 0.04) Delta max 2 ACTH response: SAD = HC (p > 0.05) | Strong | Delta max 2 cortisol response: d = 0.767 | |

| [61] | Plasma cortisol and EA relationship | Cross-sectional (SAD vs. HC) Secretion after TSST | 24 | SAD ≠ HC (p = 0.015) - SAD: ↓ total cortisol secretion (AUCg) with ↑ EA score (r2 = −0.177) - HC: ↑ total cortisol secretion (AUCg) with ↑ EA score (r2 = 0.49) | Weak | d = 2.606 | |

| [62] | Cortisol plasma level and 5-HT1A receptor distribution | Cross-sectional (SAD vs. HC) | 30 | Plasma cortisol: SAD < HC (p = 0.016) | Moderate | d = 0.897 | |

| [63] | sAA | RCT sAA levels after TSST | 39 | SAD = HC (p > 0.05) | Strong | / | |

| Sexual steroids and cortisol | [58] | Platelet DHEA, DHEA-S, pregnenolone and cortisol | Cross-sectional (SAD vs. HC) | 47 | SAD = HC - DHEA: p = 0.75 - DHEA-S: p = 0.490 - Pregnenolone: p = 0.500 - Cortisol: p = 0.1285 - Cortisol/DHEA: p = 0.18 - Cortisol/DHEA-S: p = 0.72 | Moderate | / |

| Sexual steroids | [64] | Salivary testosterone | Cross-sectional (ADs vs. HC) | SAD patients: 135 males and 252 females | SAD females < HC (p < 0.001) SAD males = HC (p = 0.76) | Moderate | Females: d = 0.299 |

| [65] | PREG-S, ALLO and DHEA-S | Cross-sectional (SAD vs. HC) | 24 males | PREG-S: SAD < HC (p = 0.008) ALLO: SAD = HC (p = 0.96) DHEA-S: SAD = HC (p = 0.165) | Moderate | PREG-S: d = 1.184 | |

| Thyroid hormones | [66] | T3, T4, fT4, TSH, anti-thyroid Ab | Cross-sectional (SAD vs. HC) | 43 patients | SAD = HC - T3: p = 0.59 - T4: p = 0.95 - fT4: p = 0.81 - TSH: p = 0.81 - TSH TRH response pattern: p = 0.71 - Antityhroid Ab: p > 0.05 | Moderate | / |

3.3.2. Salivary Alpha Amylase

3.3.3. Sexual Steroids

3.3.4. Thyroid Hormones

3.4. Immunological Markers

| REFERENCE | BIOMARKER UNDER STUDY | STUDY DESIGN | SAMPLE SIZE | FINDINGS | QUALITY SCORE 1 | COHEN’S d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [78] | IL-6, TNF-α, hsCRP | Prospective (ADs vs. HC) | 384 SAD patients: current = 255, remitted = 129 | SAD = HC Current: - IL-6 p = 0.963 - TNF-α p = 0.314 - hsCRP p = 0.129 Remitted: - IL-6 p = 0.241 - TNF-α p = 0.925 - hsCRP p = 0.365 | Moderate | / |

| [79] | CRP | Cross-sectional (ADs vs. HC) | 508 SAD patients | SAD = HC (p = 0.124) | Moderate | / |

| [80] | CRP, IL-6, TNF-α | Cross-sectional (ADs vs. HC; comparison among ADs) | 651 SAD patients | ADs = HC (p > 0.05) CRP: SAD < ADs (p = 0.04) IL-6: SAD < ADs (p = 0.05); female SAD patients p = 0.007; male SAD patients p = 0.61 TNF-α: SAD = ADs (p = 0.64) | Moderate | CRP: d = 0.207 IL6: d = 0.205 (female SAD patients d = 0.281) |

| [81] | LPS-stimulated TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8 | Cross-sectional (SAD vs. HC; OCD vs. HC; SAD vs. OCD) | 26 SAD patients | SAD = HC TNF-α: p = 0.69 IL-6: p = 0.82 IL-8: p = 0.62 SAD = OCD TNF-α: p = 0.971 IL-6: p = 0.076 IL-8: p = 0.103 | Weak | / |

| [82] | Basal and LPS-stimulated IFN-γ, IL-10, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α | Cross-sectional (SAD vs. HC) | 68 | Stimulated IFN-γ, IL-10, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α: SAD = HC (p > 0.05) Unstimulated IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α: SAD = HC (p > 0.05) Unstimulated IL-10: - SAD < HC (p = 0.04) - SAD males < HC (p = 0.016) - SAD females = HC (p = 0.30) | Moderate | Unstimulated IL-10: d = 0.517 (males: d = 0.872) |

| [83] | IL-2, soluble IL-2R | Cross-sectional (SAD vs. HC) | 30 | SAD = HC (p > 0.05) | Weak | / |

| [84] | Circulating lymphocyte phenotypic surface markers | Cross-sectional (SAD vs. HC; PD vs. HC) | 65 | ↑ CD16 (p < 0.05) | Moderate | d = 0.442 |

3.5. Antioxidant Markers

| REFERENCE | BIOMARKER UNDER STUDY | STUDY DESIGN | SAMPLE SIZE | FINDINGS | QUALITY SCORE 1 | COHEN’S d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [82] | KYN, TRYP, KYNA, KYN/TRYP, KYNA/KYN | Cross-sectional (SAD vs. HC) | 68 | SAD > HC - KYNA (p = 0.0005) - KYNA/KYN (p = 0.0005) KYN: p = 0.78 TRYP: p = 0.58 KYN/TRYP: p = 0.70 | Moderate | KYNA: d = 0.941 KYNA/KYN: d = 1.037 |

| [94] | SOD, CAT, GSHPx, MDA | Clinical Trial (SAD vs. HC; pre- and post- citalopram treatment) | 78 | Baseline: SAD > HC - SOD (p < 0.05) - CAT (p < 0.01) - GSH-Px (p < 0.01) - MDA (p < 0.01) All ↓ after citalopram treatment (p < 0.05) | Weak | Baseline SOD: d = 1.297 Baseline CAT: d = 1.352 Baseline GSH-Px: d = 1.5827 Baseline MDA: d = 2.0111 |

| [95] | SOD, GSH-Px, CAT, MDA | Cross-sectional (SAD vs. HC) | 36 | SAD > HC - SOD (p < 0.01) - CAT (p < 0.01) - GSHPx (p < 0.001) - MDA (p < 0.001) | Weak | SOD: d = 1.319 CAT: d = 0.891 GSHPx: d = 1.816 MDA: d = 4.859 |

| [96] | AGEs | Cross-sectional case-control (affective disorders and ADs vs. HC) | 691 SAD patients | SAD = HC (p > 0.05) | Moderate | / |

3.6. Neurotrophic Factors

| REFERENCE | BIOMARKER UNDER STUDY | STUDY DESIGN | SAMPLE SIZE | FINDINGS | QUALITY SCORE 1 | COHEN’S d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [108] | Serum BDNF | Cross-sectional (ADs vs. HC) | 105 SAD patients | SAD = HC (p > 0.05) | Strong | / |

| [109] | Serum BDNF | Cross-sectional (ADs vs. HC) | 20 SAD patients | SAD = HC (p = 0.913) | Moderate | / |

| [110] | Serum GDNF | Cross-sectional (ADs vs. HC) | 70 SAD patients | SAD > HC (p = 0.004) | Moderate | NA |

3.7. Neuroimaging

| IMAGING TECHNIQUE | REFERENCE | BIOMARKER UNDER STUDY | STUDY DESIGN | SAMPLE SIZE | FINDINGS | QUALITY SCORE 1 | COHEN’S d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fMRI | [113] | RSFC | Cross-sectional (SAD vs. HC) | 28 | Increased LSAS score = ↑ RSFC in: - left ↔ right amygdala (p = 0.01) - left amygdala ↔ right TVA (p = 0.04) - left ↔ right TVA (p = 0.03) | Moderate | / |

| [114] | RSFC | Cross-sectional (SAD vs. HC) | 36 | ↓ positive connections within the frontal lobe: right median PFC ↔ right inferior frontal cortex (p < 0.05) ↓ negative connections frontal ↔ occipital lobes: right median PFC ↔ left calcarine fissure, left superior occipital cortex, left cuneus (p < 0.05) | Moderate | NA | |

| [115] | RSFC, network topology | Cross-sectional (SAD vs. HC) | 84 | - ↓ 49 positive connections (p < 0.05) in the frontal, occipital, parietal–(pre) motor, and temporal regions - ↓ default mode network connectivity (p < 0.01) - ↑ Lp (p < 0.01); ↓ Cp (p < 0.01) | Moderate | NA | |

| [116] | Amygdala response to angry schematic faces | Cross sectional (SAD vs. HC) | 22 | Angry vs. neutral faces: ↑ responses (all p < 0.001) in: -- right dorsal amygdala; -- left supramarginal gyrus; -- left supplementary eye field; ↓ right dACC response | Moderate | - Amygdala: d = 1.782 - Left supramarginal gyrus: d = 2.029 - Left supplementary eye field: d = 1.949 - Right dACC: d = 1.914 | |

| [117] | Amygdala activation to facial expressions | Cross-sectional (SAD vs. HC) Harsh (angry, fearful, and contemp- tous) vs. accepting (happy) facial emotional expressions | 30 | ↑ left allocortex activation (amygdala, uncus, parahippocampampal gyrus activation): - to contemptuous vs. happy faces (p = 0.004) - to angry vs. happy faces (p = 0.02) | Moderate | d = 1.14 d = 1.00 | |

| [118] | Amygdala reactivity to emotional faces with low, moderate, and high intensity | Cross sectional (SAD vs. HC) | 22 | ↑ left amygdala activation to high intensity emotional faces (p < 0.05) | Moderate | d = 0.899 | |

| [119] | Amygdala reactivity to threatening faces of low, moderate, and high intensity | Cross-sectional (SAD vs. HC) | 24 | - ↑ left amygdala reactivity to threatening faces at moderate (p < 0.03) and high intensity (p < 0.003) - ↑ right amygdala reactivity for high intensity (p < 0.04) SAD = HC: - left amygdala low intensity (p = 0.10) - right amygdala for moderate (p = 0.18) or low (p = 0.34) intensity | Moderate | - Left amygdala, moderate intensity: d = 0.947 - Left amygdala, high intensity: d = 1.361 - Right amygdala, high intensity: d = 0.891 | |

| [120] | Amygdala connectivity to PFC at rest and during threat processing | Cross-sectional (SAD vs. HC) (EFMT; a resting state Task) | 37 | At rest: ↓ connectivity - right amygdala ↔ rostral ACC (p < 0.05) During threat: ↓ connectivity - right amygdala ↔ rostral ACC (p < 0.05) - left amygdala ↔ rostral ACC (p < 0.05) - right amygdala ↔ DLPFC (p < 0.05) - left amygdala ↔ DLPFC (p < 0.05) | Moderate | At rest: d= 0.557–1.649 During threat: - d = 0.557 - d = NA - d = NA - d = 0.557 | |

| [121] | DLPFC activation during perception of laughter | Cross- sectional (SAD vs. HC) | 26 | ↑ activation during reappraisal in the left DLPFC (p = 0.007) | Moderate | / | |

| [122] | Insula Reactivity and Connectivity to ACC when processing threat | Cross-sectional (SAD vs. HC) (EFMT fear, angry, happy expressions) | 55 | ↑ activation to fear (>happy) faces in the left aINS (p < 0.003) and right aINS (p < 0.005) ↓ connectivity right aINS ↔ dACC during fearful face processing (p < 0.05) | Moderate | - Left aINS: d = 1.2365 - Right aINS: d = 0.823 - Right aINS ↔ dACC: d = 1.4741 | |

| [123] | Brain activation during exposure to emotional faces | Cross-sectional (SAD vs. HC) | 46 | Higher LSAS scores = ↑ activation - left anterior insula (p < 0.05) - right lateral PFC (p < 0.05) | Moderate | - Left aINS: d = 1.435 - Right lateral PFC: d = 1.666 | |

| [124] | FC during face processing | Cross sectional (SAD vs. HC; SAD vs. PD) | Primary sample: 16 SAD patients Replication sample: 14 SAD patients | ↓ FC left temporal pole ↔ left hippocampus (p = 0.042), particularly with angry faces (p = 0.027) | Strong | - All faces: d = 0.190 - Angry faces: d = 0.245 | |

| [125] | Fearful face processing brain signal (whole brain, fear network parietal lobe); regional gray matter volume | Cross-sectional (SAD vs. HC) (fMRI/sMRI + SVM) | 26 males | Fearful face processing: - Whole brain activation: SAD ≠ HC (p = 0.034) - Fear network activation: SAD ≠ HC (p = 0.017) - Parietal lobe activation: SAD = HC (p = 0.548) Gray matter volume: - Whole brain: SAD ≠ HC (p = 0.001) - Regional in fear network: SAD = HC (p = 0.397) - Regional in parietal lobe: SAD = HC (p = 0.232) | Moderate | - Whole brain activation: d = 0.742 - Fear network activation: d = 0.954 - Whole brain gray matter volume: d = 1.896 | |

| [126] | CT and CSA | Cross sectional (SAD vs. HC) | 64 | ↓ CT in 3 clusters in the bilateral SFG with large portions extending into the rMFG and rostral ACC (p < 0.05) ↑ CSA clusters (p < 0.05): - left SFG/rostral ACC - left rMFG - left STG/parts of MTG - right SFG/ACC - right lOFC/rMFG | Moderate | NA | |

| PET | [62] | Relationship between cortisol plasma levels and 5-HT1A receptor BP | Cross-sectional (SAD vs. HC) | 30 males | ↑ cortisol plasma levels: ↓ 5-HT1A BP in: - amygdala (p = 0.0067) - hippocampus (p = 0.04) | Moderate | - Amygdala: d = 0.863 - Hippocampus: d = 0.8072 |

| [127] | 5-HT1A receptor BP | Cross-sectional (SAD vs. HC) | 30 males | ↓ 5-HT1A BP: - amygdala (p = 0.024) - insula (p = 0.024) - ACC (p = 0.032) | Moderate | - Amygdala: d = 0.7892 - Insula: d = 1.292 - ACC: d = 1.131 |

3.8. Neuropsychogical Markers

| REFERENCE | BIOMARKER UNDER STUDY | STUDY DESIGN | SAMPLE SIZE | FINDINGS | QUALITY SCORE 1 | COHEN’S d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [121] | Laughter perception and interpretation | Cross-sectional (SAD vs. HC) | 26 | ↑ negative perception of laughter (p = 0.005) | Moderate | d = 1.219 |

| [129] | Eye movement parameters (visual scanpath) | Cross-sectional (SAD vs. HC) | 30 | “Hyperscanning” strategy for SAD: ↓ n. of fixation to neutral and sad faces (p < 0.01) ↓ total fixation duration (p < 0.01) ↓ scanpath length for neutral faces (p < 0.01) ↑ raw scanpath length for neutral and sad faces (p < 0.05) | Moderate | - Total n. of fixations: d = 1.102 - Total fixation duration: d = 1.231 - Scanpath length, neutral faces: d = 0.978 - Scanpath length, sad faces: d = 0.846 |

| [130] | Gaze avoidance | Cross-sectional (SAD vs. HC) | 50 | ↑ gaze avoidance: ↓ fixations (p = 0.04) ↓ dwell time (p = 0.03) | Strong | - Fixations: d = 3.559 - Dwell time: d = 3.561 |

| [131] | Gaze avoidance | Cross-sectional (SAD vs. NSAC) | 39 | ↑ gaze avoidance: ↓ Total time holding eye contact (p = 0.04) ↓ Number of fixation on eyes (p = 0.02) ↓ Fixation durations upon eyes (p = 0.047) | Moderate | - Total time holding eye contact: d = 0.283 - Number of fixations on eyes: d = 0.473 - Fixation durations upon eyes: d = 0.345 |

| [132] | FNE, SADS, TCI, platelet 5HT2 receptor density | Cross-sectional (SAD vs. HC) | 20 SAD males | ↑ FNE (p < 0.0001) ↑ SADS (p < 0.0001) ↑ harm avoidance (TCI) (p < 0.0001) ↓ novelty seeking (TCI) (p < 0.0001) ↓ cooperativeness (TCI) (p < 0.0001) ↓ self-directedness (p < 0.0001) Platelet 5HT2, receptor density: SAD = HC (p > 0.05) | Weak | - FNE: d = 4.427 - SADs: d = 4.2596 - Harm avoidance: d = 4.203 - Novelty seeking: d = 2.191 - Cooperativeness: d = 1.692 - Self-directedness: d = 4.054 |

| [133] | Negative interpretative bias (sorting cards with emotional expressions at baseline and under threat) | Cross-sectional (SAD vs. HC) | 52 | ↑ probability of misclassifying neutral cards as angry under threat (p < 0.005) | Strong | d = 1.835 |

3.9. Others (Neuropeptides and Electrocardiographic Parameters)

| BIOMARKERS TYPE | REFERENCE | BIOMARKER UNDER STUDY | STUDY DESIGN | SAMPLE SIZE | FINDINGS | QUALITY SCORE 1 | COHEN’S d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuropeptides | [137] | Plasma NPY, plasma NE | Cross-sectional (SAD vs. HC vs. PD) Resting conditions and after cold stress | 11 SAD patients | SAD = HC (p > 0.05) | Weak | / |

| [138] | Plasma oxytocin | Cross-sectional (SAD vs. HC) | 46 | SAD = HC (p = 0.8) | Moderate | / | |

| [139] | Plasma oxytocin | Cross-sectional (SAD vs. HC) Levels at baseline and after Trust Game | 67 | - Baseline: SAD = HC (p = 0.059) - Mean endpoint: SAD < HC (p = 0.025) - Change score (magnitude of change in oxytocin from baseline to endpoint): SAD = HC (p = 1.0) - AUC: SAD < HC (p = 0.011) | Moderate | Mean endpoint: d = 1.0361 AUC: NA | |

| Electro-cardiographic parameters | [140] | QT dispersion (QTd) | Cross-sectional (SAD vs. HC) | 31 | SAD > HC (p < 0.0001) | Strong | d = 1.616 |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Falk, L.; Leweke, F. Social Anxiety Disorder. Recognition. Assessment and Treatment. NEJM 2017, 376, 2255–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruscio, A.M.; Brown, T.; Chiu, W.; Sareen, J.; Stein, M.; Kessler, R. Social fears and social phobia in the USA: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychol. Med. 2008, 38, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lecrubier, Y.; Wittchen, H.U.; Faravelli, C.; Bobes, J.; Patel, A.; Knapp, M. European perspective on social anxiety disorder. Eur. Psychiatry 2000, 15, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.C. The impairments caused by social phobia in the general population: Implications for intervention. Acta Psych Scand. 2003, 417, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, M.B.; Stein, D.J. Social anxiety disorder. Lancet 2008, 371, 1115–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Social Anxiety Disorder: Recognition, Assessment and Treatment [NICE Guideline No. 159], 2013. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg159 (accessed on 14 November 2022).

- Acarturk, C.; Cuijpers, P.; van Straten, A.; de Graaf, R. Psychological treatment of social anxiety disorder: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 2009, 39, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stangier, U.; Schramm, E.; Heidenreich, T.; Berger, M.; Clark, D.M. Cognitive therapy vs interpersonal psychotherapy in social anxiety disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2011, 68, 692–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ipser, J.C.; Kariuki, C.M.; Stein, D.J. Pharmacotherapy for social anxiety disorder: A systematic review. Exp. Rev. Neurother. 2008, 8, 235–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canton, J.; Scott, K.M.; Glue, P. Optimal treatment of social phobia: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsych. Dis. Treat. 2012, 8, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pollack, M.H.; Van Ameringen, M.; Simon, N.M.; Worthington, J.W.; Hoge, E.A.; Keshaviah, A.; Stein, M.B. A double-blind randomized controlled trial of augmentation and switch strategies for refractory social anxiety disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 2014, 171, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozupone, M.; La Montagna, M.; D’Urso, F.; Daniele, A.; Greco, A.; Seripa, D.; Logroscino, G.; Bellomo, A.; Panza, F. The Role of Biomarkers in Psychiatry. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 1118, 135–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, M.B.; Keshaviah, A.; Haddad, S.A.; Van Ameringen, M.; Simon, N.M.; Pollack, M.H.; Smoller, J.W. Influence of RGS2 on sertraline treatment for social anxiety disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 2014, 39, 1340–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Serretti, A.; Chiesa, A.; Calati, R.; Perna, G.; Bellodi, L.; De Ronchi, D. Common genetic, clinical, demographic and psychosocial predictors of response to pharmacotherapy in mood and anxiety disorders. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2009, 24, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Gutiérrez, M.S.; Navarrete, F.; Sala, F.; Gasparyan, A.; Austrich-Olivares, A.; Manzanares, J. Biomarkers in Psychiatry: Concept, Definition, Types and Relevance to the Clinical Reality. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, C.H.Y.; Costafreda, S.G. Neuroimaging-based biomarkers in psychiatry: Clinical opportunities of a paradigm shift. Can. J. Psychiatry 2013, 58, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Meier, S.M.; Deckert, J. Genetics of Anxiety Disorders. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2019, 21, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiele, M.A.; Domschke, K. Epigenetics at the crossroads between genes, environment and resilience in anxiety disorders. Genes Brain Behav. 2018, 17, e12423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Esch, T.; Stefano, G.B. The Neurobiology of Love. Neuro. Endocrinol. Lett. 2005, 26, 175–192. [Google Scholar]

- Cataldo, I.; Azhari, A.; Lepri, B.; Esposito, G. Oxytocin receptors (OXTR) and early parental care: An interaction that modulates psychiatric disorders. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2018, 82, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apter-Levy, Y.; Feldman, M.; Vakart, A.; Ebstein, R.P.; Feldman, R. Impact of maternal depression across the first 6 years of life on the child’s mental health, social engagement, and empathy: The moderating role of oxytocin. Am. J. Psychiatry 2013, 170, 1161–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ziegler, C.; Dannlowski, U.; Bräuer, D.; Stevens, S.; Laeger, I.; Wittman, H.; Kugel, H.; Dobel, C.; Hurlemann, R.; Reif, A.; et al. Oxytocin receptor gene methylation: Converging multilevel evidence for a role in social anxiety. Neuropsychopharmacology 2015, 40, 1528–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dannlowski, U.; Kugel, H.; Grotegerd, D.; Redlich, R.; Opel, N.; Dohm, K.; Zaremba, D.; Grogler, A.; Schwieren, J.; Suslow, T.; et al. Disadvantage of social sensitivity: Interaction of oxytocin receptor genotype and child maltreatment on brain structure. Biol. Psychiatry 2016, 80, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabano, S.; Tassi, L.; Cannone, M.G.; Brescia, G.; Gaudioso, G.; Ferrara, M.; Colapetro, P.; Fontana, L.; Mioso, M.R.; Croci, G.A.; et al. Mental health and the effects on methylation of stress-related genes in front-line versus other health care professionals during the second wave of COVID-19 pandemic: An Italian pilot study. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2022, 24, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandelow, B.; Baldwin, D.; Abelli, M.; Bolea-Alamanac, B.; Bourin, M.; Chamberlain, S.R.; Consi, E.; Davies, S.; Domschke, K.; Fineberg, N.; et al. Biological markers for anxiety disorders, OCD and PTSD: A consensus statement. Part II: Neurochemistry, neurophysiology and neurocognition. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2017, 18, 162–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.K.; Jeon, S.W. Neuroinflammation and the Immune-Kynurenine Pathway in Anxiety Disorders. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2018, 16, 574–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovote, P.; Fadok, J.P.; Lüthi, A. Neuronal circuits for fear and anxiety. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2015, 16, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, M.S.; Pedersen, A.D. A systematic review of neuropsychological performance in social anxiety disorder. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2011, 65, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutterby, S.R.; Bedwell, J.S. Lack of neuropsychological deficits in generalized social phobia. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armijo-Olivo, S.; Stiles, C.R.; Hagen, N.A.; Biondo, P.D.; Cummings, G.G. Assessment of study quality for systematic reviews: A comparison of the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool and the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool: Methodological research. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2012, 18, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forstner, A.J.; Rambau, S.; Friedrich, N.; Ludwig, K.U.; Böhmer, A.C.; Mangold, E.; Maaser, A.; Hess, T.; Kleiman, A.; Bittner, A.; et al. Further evidence for genetic variation at the serotonin transporter gene SLC6A4 contributing toward anxiety. Psychiatr. Genet. 2017, 27, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, M.B.; Chartier, M.J.; Kozak, M.V.; King, N.; Kennedy, J.L. Genetic linkage to the serotonin transporter protein and 5HT2A receptor genes excluded in generalized social phobia. Psychiatry Res. 1998, 81, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, J.L.; Neves-Pereira, M.; King, N.; Lizak, M.V.; Basile, V.S.; Chartier, M.J.; Stein, M.B. Dopamine system genes not linked to social phobia. Psychiatr. Genet. 2001, 11, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelernter, J.; Page, G.P.; Stein, M.B.; Woods, S.W. Genome-wide linkage scan for loci predisposing to social phobia: Evidence for a chromosome 16 risk locus. Am. J. Psychiatry 2004, 161, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, K.P.; Stein, M.B.; Kranzler, H.R.; Yang, B.Z.; Farrer, L.A.; Gelernter, J. The α-endomannosidase gene (MANEA) is associated with panic disorder and social anxiety disorder. Transl. Psychiatry 2014, 4, e353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bas-Hoogendam, J.M.; Harrewijn, A.; Tissier, R.; van der Molen, M.J.; van Steenbergen, H.; van Vliet, I.M.; Reichart, C.G.; Houwing-Duistermaat, J.J.; Slagboom, P.E.; van der Wee, N.J.; et al. The Leiden Family Lab study on Social Anxiety Disorder: A multiplex, multigenerational family study on neurocognitive endophenotypes. Int. J. Methods Psych. Res. 2018, 27, e1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reinelt, E.; Stopsack, M.; Aldinger, M.; John, U.; Grabe, H.J.; Barnow, S. Testing the diathesis-stress model: 5-HTTLPR, childhood emotional maltreatment, and vulnerability to social anxiety disorder. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2013, 162, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneier, F.R.; Abi-Dargham, A.; Martinez, D.; Slifstein, M.; Hwang, D.R.; Liebowitz, M.R.; Laruelle, M. Dopamine transporters, D2 receptors, and dopamine release in generalized social anxiety disorder. Depress. Anxiety 2009, 26, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, K.M.; Perlis, R.H.; Wan, Y.J. Pharmacogenomic strategy for individualizing antidepressant therapy. Dialog. Clin. Neurosci. 2008, 10, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buoli, M.; Caldiroli, A.; Caletti, E.; Paoli, R.A.; Altamura, A.C. New approaches to the pharmacological management of generalized anxiety disorder. Exp. Opin. Pharm. 2013, 14, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Z.; Huang, Y.; Wang, J.; Min, W.; Zhou, B. The association between serotonin-related gene polymorphisms and susceptibility and early sertraline response in patients with panic disorder. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrer, L.A.; Kranzler, H.R.; Yu, Y.; Weiss, R.D.; Brady, K.T.; Anton, R.; Cubells, J.F.; Gelernter, J. Association of variants in MANEA with cocaine-related behaviors. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2009, 66, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegand, A.; Kreifelts, B.; Munk, M.H.J.; Geiselhart, N.; Ramadori, K.E.; MacIsaac, J.L.; Fallgatter, A.J.; Kobor, M.S.; Nieratschker, V. DNA methylation differences associated with social anxiety disorder and early life adversity. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jirtle, R.L.; Skinner, M.K. Environmental epigenomics and disease susceptibility. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2007, 8, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ziegler, C.; Grundner-Culemann, F.; Schiele, M.A.; Schlosser, P.; Kollert, L.; Mahr, M.; Gajewska, A.; Lesch, K.-P.; Deckert, J.; Köttgen, A.; et al. The DNA methylome in panic disorder: A case-control and longitudinal psychotherapy-epigenetic study. Transl. Psychiatry 2019, 9, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kesselmeier, M.; Pütter, C.; Volckmar, A.L.; Baurecht, H.; Grallert, H.; Illig, T.; Ismail, K.; Ollikainen, M.; Silén, Y.; Keski-Rahkonen, A.; et al. High-throughput DNA methylation analysis in anorexia nervosa confirms TNXB hypermethylation. World. J. Biol. Psychiatry 2018, 19, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iurato, S.; Carrillo-Roa, T.; Arloth, J.; Czamara, D.; Diener-Hölzl, L.; Lange, J.; Müller-Myhsok, B.; Binder, E.B.; Erhardt, A. DNA Methylation signatures in panic disorder. Transl. Psychiatry 2017, 7, 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Serati, M.; Grassi, S.; Redaelli, M.; Pergoli, L.; Cantone, L.; La Vecchia, A.; Barkin, J.L.; Colombo, E.; Tiso, G.; Abbiati, C.; et al. Is There an Association Between Oxytocin Levels in Plasma and Pregnant Women’s Mental Health? J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2021, 27, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marazziti, D.; Diep, P.T.; Carter, S.; Carbone, M.G. Oxytocin: An Old Hormone, a Novel Psychotropic Drug and its Possible Use in Treating Psychiatric Disorders. Curr. Med. Chem. 2022, 29, 5615–5687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czamara, D.; Eraslan, G.; Page, C.M.; Lahti, J.; Lahti-Pulkkinen, M.; Hämäläinen, E.; Kajantie, E.; Laivuori, H.; Villa, P.M.; Reynolds, R.M.; et al. Integrated analysis of environmental and genetic influences on cord blood DNA methylation in new-borns. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klumbies, E.; Braeuer, D.; Hoyer, J.; Kirschbaum, C. The reaction to social stress in social phobia: Discordance between physiological and subjective parameters. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e10567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tamura, A.; Maruyama, Y.; Ishitobi, Y.; Kawano, A.; Ando, T.; Ikeda, R.; Inoue, A.; Imanaga, J.; Okamoto, S.; Kanehisa, M.; et al. Salivary alpha-amylase and cortisol responsiveness following electrical stimulation stress in patients with the generalized type of social anxiety disorder. Pharmacopsychiatry 2013, 46, 225–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhde, T.W.; Tancer, M.E.; Gelernter, C.S.; Vittone, B.J. Normal urinary free cortisol and postdexamethasone cortisol in social phobia: Comparison to normal volunteers. J. Affect. Disord. 1994, 30, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Veen, J.F.; van Vliet, I.M.; Derijk, R.H.; van Pelt, J.; Mertens, B.; Zitman, F.G. Elevated alpha-amylase but not cortisol in generalized social anxiety disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2008, 33, 1313–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vreeburg, S.A.; Zitman, F.G.; van Pelt, J.; Derijk, R.H.; Verhagen, J.C.; van Dyck, R.; Hoogendijk, W.J.; Smit, J.H.; Penninx, B.W. Salivary cortisol levels in persons with and without different anxiety disorders. Psychosom. Med. 2010, 72, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laufer, N.; Maayan, R.; Hermesh, H.; Marom, S.; Gilad, R.; Strous, R.; Weizman, A. Involvement of GABAA receptor modulating neuroactive steroids in patients with social phobia. Psychiatry Res. 2005, 137, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrowski, K.; Schmalbach, I.; Strunk, A.; Hoyer, J.; Kirschbaum, C.; Joraschky, P. Cortisol reactivity in social anxiety disorder: A highly standardized and controlled study. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2021, 123, 104913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condren, R.M.; O’Neill, A.; Ryan, M.C.; Barrett, P.; Thakore, J.H. HPA axis response to a psychological stressor in generalised social phobia. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2002, 27, 693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaccarino, O.; Levitan, R.; Ravindran, A. The cortisol response to social stress in social anxiety disorder. Asian J. Psychiatry 2015, 14, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzenberger, R.; Wadsak, W.; Spindelegger, C.; Mitterhauser, M.; Akimova, E.; Mien, L.K.; Fink, M.; Moser, U.; Savli, M.; Kranz, G.S.; et al. Cortisol plasma levels in social anxiety disorder patients correlate with serotonin-1A receptor binding in limbic brain regions. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010, 13, 1129–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Rubio, M.J.; Espín, L.; Hidalgo, V.; Salvador, A.; Gómez-Amor, J. Autonomic markers associated with generalized social phobia symptoms: Heart rate variability and salivary alpha-amylase. Stress 2017, 20, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giltay, E.J.; Enter, D.; Zitman, F.G.; Penninx, B.W.; van Pelt, J.; Spinhoven, P.; Roelofs, K. Salivary testosterone: Associations with depression, anxiety disorders, and antidepressant use in a large cohort study. J. Psychosom. Res. 2012, 72, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Heydari, B.; Le Mellédo, J.M. Low pregnenolone sulphate plasma concentrations in patients with generalized social phobia. Psychol. Med. 2002, 32, 929–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tancer, M.E.; Stein, M.B.; Gelernter, C.S.; Uhde, T.W. The hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis in social phobia. Am. J. Psychiatry 1990, 147, 929–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bitran, D.; Shiekh, M.; McLeod, M. Anxiolytic effect of progesterone is mediated by the neurosteroid allopregnanolone at brain GABAA receptors. J. Neuroendocrinol. 1995, 7, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, D.S.; Kulkarni, S.K. Differential anxiolytic effects of neurosteroids in the mirrored chamber behavior test in mice. Brain Res. 1997, 752, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, G.; Lightman, S. The coshuman stress response. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cosci, F.; Mansueto, G. Biological and Clinical Markers in Panic Disorder. Psychiatry Investig. 2019, 16, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lenze, E.J.; Mantella, R.C.; Shi, P.; Goate, A.M.; Nowotny, P.; Butters, M.A.; Andreescu, C.; Thompson, P.A.; Rollman, B.L. Elevated cortisol in older adults with generalized anxiety disorder is reduced by treatment: A placebo-controlled evaluation of escitalopram. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Off. J. Am. Assoc. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2011, 19, 482–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dieleman, G.C.; Huizink, A.C.; Tulen, J.H.; Utens, E.M.; Creemers, H.E.; van der Ende, J.; Verhulst, F.C. Alterations in HPA-axis and autonomic nervous system functioning in childhood anxiety disorders point to a chronic stress hypothesis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2015, 51, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettema, J.M.; Prescott, C.A.; Myers, J.M.; Neale, M.C.; Kendler, K.S. The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for anxiety disorders in men and women. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shekhar, A.; Keim, S.R. LY354740, a potent group II metabotropic glutamate receptor agonist prevents lactate-induced panic-like response in panic-prone rats. Neuropharmacology 2000, 39, 1139–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutschemaekers, M.; de Kleine, R.A.; Hendriks, G.J.; Kampman, M.; Roelofs, K. The enhancing effects of testosterone in exposure treatment for social anxiety disorder: A randomized proof-of-concept trial. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engert, V.; Vogel, S.; Efanov, S.I.; Duchesne, A.; Corbo, V.; Ali, N.; Pruessner, J.C. Investigation into the cross-correlation of salivary cortisol and alpha-amylase responses to psychological stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2011, 36, 1294–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knorr, U.; Vinberg, M.; Kessing, L.V.; Wetterslev, J. Salivary cortisol in depressed patients versus control persons: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2010, 35, 1275–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaus, J.; von Känel, R.; Lasserre, A.M.; Strippoli, M.F.; Vandeleur, C.L.; Castelao, E.; Gholam-Rezaee, M.; Marangoni, C.; Wagner, E.N.; Marques-Vidal, P.; et al. The bidirectional relationship between anxiety disorders and circulating levels of inflammatory markers: Results from a large longitudinal population-based study. Depress. Anxiety 2018, 35, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Naudé, P.J.W.; Roest, A.M.; Stein, D.J.; de Jonge, P.; Doornbos, B. Anxiety disorders and CRP in a population cohort study with 54,326 participants: The LifeLines study. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2018, 19, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelzangs, N.; Beekman, A.T.; de Jonge, P.; Penninx, B.W. Anxiety disorders and inflammation in a large adult cohort. Transl. Psychiatry 2013, 3, e249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fluitman, S.; Denys, D.; Vulink, N.; Schutters, S.; Heijnen, C.; Westenberg, H. Lipopolysaccharide-induced cytokine production in obsessive-compulsive disorder and generalized social anxiety disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2010, 178, 313–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, M.I.; Long-Smith, C.; Moloney, G.M.; Morkl, S.; O’Mahony, S.M.; Cryan, J.F.; Clarke, G.; Dinan, T.G. The immune-kynurenine pathway in social anxiety disorder. Brain Behav. Immun. 2022, 99, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapaport, M.H.; Stein, M.B. Serum interleukin-2 and soluble interleukin-2 receptor levels in generalized social phobia. Anxiety 1994, 1, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapaport, M.H. Circulating lymphocyte phenotypic surface markers in anxiety disorder patients and normal volunteers. Biol. Psychiatry 1998, 43, 458–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michopoulos, V.; Powers, A.; Gillespie, C.F.; Ressler, K.J.; Jovanovic, T. Inflammation in Fear- and Anxiety-Based Disorders: PTSD, GAD, and Beyond. Neuropsychopharmacology 2017, 42, 254–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Costello, H.; Gould, R.L.; Abrol, E.; Howard, R. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between peripheral inflammatory cytokines and generalized anxiety disorder. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e027925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Altamura, A.C.; Buoli, M.; Albano, A.; Dell’Osso, B. Age at onset and latency to treatment (duration of untreated illness) in patients with mood and anxiety disorders: A naturalistic study. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2010, 25, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamers, F.; van Oppen, P.; Comijs, H.C.; Smit, J.H.; Spinhoven, P.; Van Balkom, A.J.L.M.; Nolen, W.A.; Zitman, F.G.; Beekman, A.T.F.; Penninx, B.W.J.H. Comorbidity patterns of anxiety and depressive disorders in a large cohort study: The Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA). J. Clin. Psychiatry 2011, 72, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, M.M.; Ferreira, T.B.; Pacheco, P.A.; Barros, P.O.; Almeida, C.R.; Araújo-Lima, C.F.; Silva-Filho, R.G.; Hygino, J.; Andrade, R.M.; Linhares, U.C.; et al. Enhanced Th17 phenotype in individuals with generalized anxiety disorder. J. Neuroimmunol. 2010, 229, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocki, T.; Wnuk, S.; Kloc, R.; Kocki, J.; Owe-Larsson, B.; Urbanska, E.M. New insight into the antidepressants action: Modulation of kynurenine pathway by increasing the kynurenic acid/3-hydroxykynurenine ratio. J. Neural. Transm. 2012, 119, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Farrell, K.; Harkin, A. Stress-related regulation of the kynurenine pathway: Relevance to neuropsychiatric and degenerative disorders. Neuropharmacology 2017, 112 Pt B, 307–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reinhorn, I.M.; Bernstein, C.N.; Graff, L.A.; Patten, S.B.; Sareen, J.; Fisk, J.D.; Bolton, J.M.; Hitchon, C.; Marrie, R.A.; CIHR Team in Defining the Burden and Managing the Effects of Immune-mediated Inflammatory Disease. Social phobia in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. J. Psychosom. Res. 2020, 128, 109890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altamura, A.C.; Buoli, M.; Pozzoli, S. Role of immunological factors in the pathophysiology and diagnosis of bipolar disorder: Comparison with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2014, 68, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atmaca, M.; Tezcan, E.; Kuloglu, M.; Ustundag, B.; Tunckol, H. Antioxidant enzyme and malondialdehyde values in social phobia before and after citalopram treatment. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2004, 254, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atmaca, M.; Kuloglu, M.; Tezcan, E.; Ustundag, B. Antioxidant enzyme and malondialdehyde levels in patients with social phobia. Psychiatry Res. 2008, 159, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, J.M.; Sutterland, A.L.; Sousa, P.A.D.F.P.D.; Schirmbeck, F.; Cohn, D.M.; Lok, A.; Tan, H.L.; Zwinderman, A.H.; de Haan, L. Association between skin autofluorescence of advanced glycation end products and affective disorders in the lifelines cohort study. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 275, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capuzzi, E.; Caldiroli, A.; Capellazzi, M.; Tagliabue, I.; Buoli, M.; Clerici, M. Biomarkers of suicidal behaviors: A comprehensive critical review. Adv. Clin. Chem. 2020, 96, 179–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, B.E. Inflammation and depression: A causal or coincidental link to the pathophysiology? Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2018, 30, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mor, A.; Tankiewicz-Kwedlo, A.; Krupa, A.; Pawlak, D. Role of Kynurenine Pathway in Oxidative Stress during Neurodegenerative Disorders. Cells 2021, 10, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldiroli, A.; Auxilia, A.M.; Capuzzi, E.; Clerici, M.; Buoli, M. Malondialdehyde and bipolar disorder: A short comprehensive review of available literature. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 274, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capuzzi, E.; Ossola, P.; Caldiroli, A.; Auxilia, A.M.; Buoli, M. Malondialdehyde as a candidate biomarker for bipolar disorder: A meta-analysis. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2022, 113, 110469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryleva, E.Y.; Brundin, L. Suicidality and activation of the kynurenine pathway of tryptophan metabolism. Curr. Top Behav. Neurosci. 2017, 31, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribaudo, G.; Bortoli, M.; Pavan, C.; Zagotto, G.; Orian, L. Antioxidant potential of psychotropic drugs: From clinical evidence to in vitro and in vivo assessment and toward a new challenge for in silico molecular design. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Réus, G.Z.; Jansen, K.; Titus, S.; Carvalho, A.F.; Gabbay, V.; Quevedo, J. Kynurenine pathway dysfunction in the pathophysiology and treatment of depression: Evidences from animal and human studies. J. Psych. Res. 2015, 68, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gheorghe, C.E.; Martin, J.A.; Manriquez, F.V.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F.; Clarke, G. Focus on the essentials: Tryptophan metabolism and the microbiome-gut-brain axis. Curr. Opin. Pharm. 2019, 48, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capuzzi, E.; Bartoli, F.; Crocamo, C.; Malerba, M.R.; Clerici, M.; Carrà, G. Recent suicide attempts and serum lipid profile in subjects with mental disorders: A cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 270, 611–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Humer, E.; Pieh, C.; Probst, T. Metabolomic Biomarkers in Anxiety Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molendijk, M.L.; Bus, B.A.; Spinhoven, P.; Penninx, B.W.; Prickaerts, J.; Oude Voshaar, R.C.; Elzinga, B.M. Gender specific associations of serum levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in anxiety. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2012, 13, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlino, D.; Francavilla, R.; Baj, G.; Kulak, K.; d’Adamo, P.; Ulivi, S.; Cappellani, S.; Gasparini, P.; Tongiorgi, E. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor serum levels in genetically isolated populations: Gender-specific association with anxiety disorder subtypes but not with anxiety levels or Val66Met polymorphism. PeerJ 2015, 3, e1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pedrotti Moreira, F.; Wiener, C.D.; Jansen, K.; Portela, L.V.; Lara, D.R.; Souza, L.D.M.; da Silva, R.A.; Oses, J.P. Serum GDNF levels and anxiety disorders in a population-based study of young adults. Clin. Chim. Acta 2018, 485, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucon-Xiccato, T.; Tomain, M.; D’Aniello, S.; Bertolucci, C. BDNF loss affects activity, sociability, and anxiety-like behaviour in zebrafish. Behav. Brain Res. 2023, 436, 114115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suliman, S.; Hemmings, S.M.; Seedat, S. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) protein levels in anxiety disorders: Systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreifelts, B.; Weigel, L.; Ethofer, T.; Brück, C.; Erb, M.; Wildgruber, D. Cerebral resting state markers of biased perception in social anxiety. Brain Struct. Funct. 2019, 224, 759–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Chen, H.; Qiu, C.; Liao, W.; Warwick, J.M.; Duan, X.; Zhang, W.; Gong, Q. Disrupted functional connectivity in social anxiety disorder: A resting-state fMRI study. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2011, 29, 701–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Qiu, C.; Meng, Y.; Yuan, M.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, Z.; Li, Y.; Huang, X.; Gong, Q.; Lui, S.; et al. Altered Topological Properties of Brain Networks in Social Anxiety Disorder: A Resting-state Functional MRI Study. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 43089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, K.C.; Wright, C.I.; Wedig, M.M.; Gold, A.L.; Pollack, M.H.; Rauch, S.L. A functional MRI study of amygdala responses to angry schematic faces in social anxiety disorder. Depress. Anxiety 2008, 25, 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, M.B.; Goldin, P.R.; Sareen, J.; Zorrilla, L.T.; Brown, G.G. Increased amygdala activation to angry and contemptuous faces in generalized social phobia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2002, 59, 1027–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yoon, K.L.; Fitzgerald, D.A.; Angstadt, M.; McCarron, R.A.; Phan, K.L. Amygdala reactivity to emotional faces at high and low intensity in generalized social phobia: A 4-Tesla functional MRI study. Psychiatry Res. 2007, 154, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klumpp, H.; Angstadt, M.; Nathan, P.J.; Phan, K.L. Amygdala reactivity to faces at varying intensities of threat in generalized social phobia: An event-related functional MRI study. Psychiatry Res. 2010, 183, 167–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prater, K.E.; Hosanagar, A.; Klumpp, H.; Angstadt, M.; Phan, K.L. Aberrant amygdala-frontal cortex connectivity during perception of fearful faces and at rest in generalized social anxiety disorder. Depress. Anxiety 2013, 30, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kreifelts, B.; Brück, C.; Ethofer, T.; Ritter, J.; Weigel, L.; Erb, M.; Wildgruber, D. Prefrontal mediation of emotion regulation in social anxiety disorder during laughter perception. Neuropsychologia 2017, 96, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klumpp, H.; Angstadt, M.; Phan, K.L. Insula reactivity and connectivity to anterior cingulate cortex when processing threat in generalized social anxiety disorder. Biol. Psychol. 2012, 89, 273–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carré, A.; Gierski, F.; Lemogne, C.; Tran, E.; Raucher-Chéné, D.; Béra-Potelle, C.; Portefaix, C.; Kaladjian, A.; Pierot, L.; Besche-Richard, C.; et al. Linear association between social anxiety symptoms and neural activations to angry faces: From subclinical to clinical levels. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2014, 9, 880–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pantazatos, S.P.; Talati, A.; Schneier, F.R.; Hirsch, J. Reduced anterior temporal and hippocampal functional connectivity during face processing discriminates individuals with social anxiety disorder from healthy controls and panic disorder, and increases following treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology 2014, 39, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Frick, A.; Gingnell, M.; Marquand, A.F.; Howner, K.; Fischer, H.; Kristiansson, M.; Williams, S.C.; Fredrikson, M.; Furmark, T. Classifying social anxiety disorder using multivoxel pattern analyses of brain function and structure. Behav. Brain Res. 2014, 259, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Luo, Q.; Wang, S.; Qiu, L.; Pan, N.; Kuang, W.; Lui, S.; Huang, X.; Yang, X.; Kemp, G.J.; et al. Dissociations in cortical thickness and surface area in non-comorbid never-treated patients with social anxiety disorder. EBioMedicine 2020, 58, 102910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzenberger, R.R.; Mitterhauser, M.; Spindelegger, C.; Wadsak, W.; Klein, N.; Mien, L.K.; Holik, A.; Attarbaschi, T.; Mossaheb, N.; Sacher, J.; et al. Reduced Serotonin-1A Receptor Binding in Social Anxiety Disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 2007, 61, 1081–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nakao, T.; Sanematsu, H.; Yoshiura, T.; Togao, O.; Murayama, K.; Tomita, M.; Masuda, Y.; Kanba, S. fMRI of patients with social anxiety disorder during a social situation task. Neurosci. Res. 2011, 69, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horley, K.; Williams, L.M.; Gonsalvez, C.; Gordon, E. Social phobics do not see eye to eye: A visual scanpath study of emotional expression processing. J. Anxiety Disord. 2003, 17, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moukheiber, A.; Rautureau, G.; Perez-Diaz, F.; Soussignan, R.; Dubal, S.; Jouvent, R.; Pelissolo, A. Gaze avoidance in social phobia: Objective measure and correlates. Behav. Res. Ther. 2010, 48, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weeks, J.W.; Howell, A.N.; Goldin, P.R. Gaze avoidance in social anxiety disorder. Depress. Anxiety 2013, 30, 749–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Sunitha, T.A.; Velayudhan, A.; Khanna, S. An investigation into the psychobiology of social phobia: Personality domains and serotonergic function. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1997, 95, 544–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohlman, J.; Carmin, C.N.; Price, R.B. Jumping to interpretations: Social anxiety disorder and the identification of emotional facial expressions. Behav. Res. 2007, 45, 591–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ollendick, T.H.; White, S.W.; Richey, J.; Kim-Spoon, J.; Ryan, S.M.; Wieckowski, A.T.; Coffman, M.C.; Elias, R.; Strege, M.V.; Capriola-Hall, N.N.; et al. Attention Bias Modification Treatment for Adolescents With Social Anxiety Disorder. Behav. Ther. 2019, 50, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ezzi, A.; Kamel, N.; Faye, I.; Gunaseli, E. Review of EEG, ERP, and Brain Connectivity Estimators as Predictive Biomarkers of Social Anxiety Disorder. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, Y.H.; Shin, J.E.; Lee, Y.I.; Jang, J.H.; Jo, H.J.; Choi, S.H. Altered Amygdala Resting-State Functional Connectivity and Hemispheric Asymmetry in Patients With Social Anxiety Disorder. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, M.B.; Hauger, R.L.; Dhalla, K.S.; Chartier, M.J.; Asmundson, G.J. Plasma neuropeptide Y in anxiety disorders: Findings in panic disorder and social phobia. Psychiatry Res. 1996, 59, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoge, E.A.; Pollack, M.H.; Kaufman, R.E.; Zak, P.J.; Simon, N.M. Oxytocin levels in social anxiety disorder. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2008, 14, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoge, E.A.; Lawson, E.A.; Metcalf, C.A.; Keshaviah, A.; Zak, P.J.; Pollack, M.H.; Simon, N.M. Plasma oxytocin immunoreactive products and response to trust in patients with social anxiety disorder. Depress. Anxiety 2012, 29, 924–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nahshoni, E.; Gur, S.; Marom, S.; Levin, J.B.; Weizman, A.; Hermesh, H. QT dispersion in patients with social phobia. J. Affect. Disord. 2004, 78, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccirillo, G.; Viola, E.; Nocco, M.; Santagada, E.; Durante, M.; Bucca, C.; Marigliano, V. Autonomic modulation and QT interval dispersion in hypertensive subjects with anxiety. Hypertension 1999, 34, 242–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maejima, Y.; Sakuma, K.; Santoso, P.; Gantulga, D.; Katsurada, K.; Ueta, Y.; Hiraoka, Y.; Nishimori, K.; Tanaka, S.; Shimomura, K.; et al. Oxytocinergic circuit from paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei to arcuate POMC neurons in hypothalamus. FEBS Lett. 2014, 588, 4404–4412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintana, D.S.; Guastella, A.J. An Allostatic Theory of Oxytocin. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2020, 24, 515–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakajima, M.; Görlich, A.; and Heintz, N. Oxytocin modulates female sociosexual behavior through a specific class of prefrontal cortical interneurons. Cell 2014, 159, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jang, M.; Jung, T.; Jeong, Y.; Byun, Y.; Noh, J. Oxytocin modulation in the medial prefrontal cortex of pair-exposed rats during fear conditioning. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2022, 141, 105752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guastella, A.J.; Mitchell, P.B.; Dadds, M.R. Oxytocin increases gaze to the eye region of human faces. Biol. Psychiatry 2008, 63, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andari, E.; Duhamel, J.-R.; Zalla, T.; Herbrecht, E.; Leboyer, M.; Sirigu, A. Promoting social behavior with oxytocin in high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 4389–4394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Labuschagne, I.; Phan, K.L.; Wood, A.; Angstadt, M.; Chua, P.; Heinrichs, M.; Stout, J.C.; Nathan, P.J. Medial frontal hyperactivity to sad faces in generalized social anxiety disorder and modulation by oxytocin. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012, 15, 883–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bernardi, J.; Aromolaran, K.A.; Aromolaran, A.S. Neurological Disorders and Risk of Arrhythmia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 22, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiner, I.C.; Tibubos, A.N.; Werner, A.M.; Ernst, M.; Brähler, E.; Wiltink, J.; Michal, M.; Schulz, A.; Wild, P.S.; Münzel, T.; et al. The association of chronic anxiousness with cardiovascular disease and mortality in the community: Results from the Gutenberg Health Study. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermani, M.; Marcus, M.; Katzman, M.A. Rates of detection of mood and anxiety disorders in primary care: A descriptive, cross-sectional study. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disord. 2011, 13, 27211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brook, C.A.; Schmidt, L.A. Social anxiety disorder: A review of environmental risk factors. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2008, 4, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koyuncu, A.; İnce, E.; Ertekin, E.; Tükel, R. Comorbidity in social anxiety disorder: Diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Drugs Context 2019, 8, 212573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viljoen, M.; Benecke, R.M.; Martin, L.; Adams, R.; Seedat, S.; Smith, C. Anxiety: An overlooked confounder in the characterisation of chronic stress-related conditions? PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0230053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Strawn, J.R.; Ekhator, N.N.; Horn, P.S.; Baker, D.G.; Geracioti, T.D., Jr. Blood pressure and cerebrospinal fluid norepinephrine in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychosom. Med. 2004, 66, 757–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Boksa, P. A way forward for research on biomarkers for psychiatric disorders. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2013, 38, 75–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Łoś, K.; Waszkiewicz, N. Biological Markers in Anxiety Disorders. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strawn, J.R.; Levine, A. Treatment Response Biomarkers in Anxiety Disorders: From Neuroimaging to Neuronally-Derived Extracellular Vesicles and Beyond. Biomark. Neuropsychiatry 2020, 3, 100024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Verbeke, W. Understanding importance of clinical biomarkers for diagnosis of anxiety disorders using machine learning models. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Caldiroli, A.; Capuzzi, E.; Affaticati, L.M.; Surace, T.; Di Forti, C.L.; Dakanalis, A.; Clerici, M.; Buoli, M. Candidate Biological Markers for Social Anxiety Disorder: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 835. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24010835

Caldiroli A, Capuzzi E, Affaticati LM, Surace T, Di Forti CL, Dakanalis A, Clerici M, Buoli M. Candidate Biological Markers for Social Anxiety Disorder: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023; 24(1):835. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24010835

Chicago/Turabian StyleCaldiroli, Alice, Enrico Capuzzi, Letizia M. Affaticati, Teresa Surace, Carla L. Di Forti, Antonios Dakanalis, Massimo Clerici, and Massimiliano Buoli. 2023. "Candidate Biological Markers for Social Anxiety Disorder: A Systematic Review" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 24, no. 1: 835. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24010835

APA StyleCaldiroli, A., Capuzzi, E., Affaticati, L. M., Surace, T., Di Forti, C. L., Dakanalis, A., Clerici, M., & Buoli, M. (2023). Candidate Biological Markers for Social Anxiety Disorder: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(1), 835. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24010835