Human Placental Adaptive Changes in Response to Maternal Obesity: Sex Specificities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Placental Development

3. Impact of Maternal Obesity on Placental Development: Trophoblast Differentiation

4. Impact of Maternal Obesity on Placental Morphological Characteristics

5. Impact of Maternal Obesity on Placental Metabolism

5.1. Impact of Maternal Obesity on Placental Glucose Metabolism

5.2. Impact of Maternal Obesity on Placental Amino Acid Metabolism

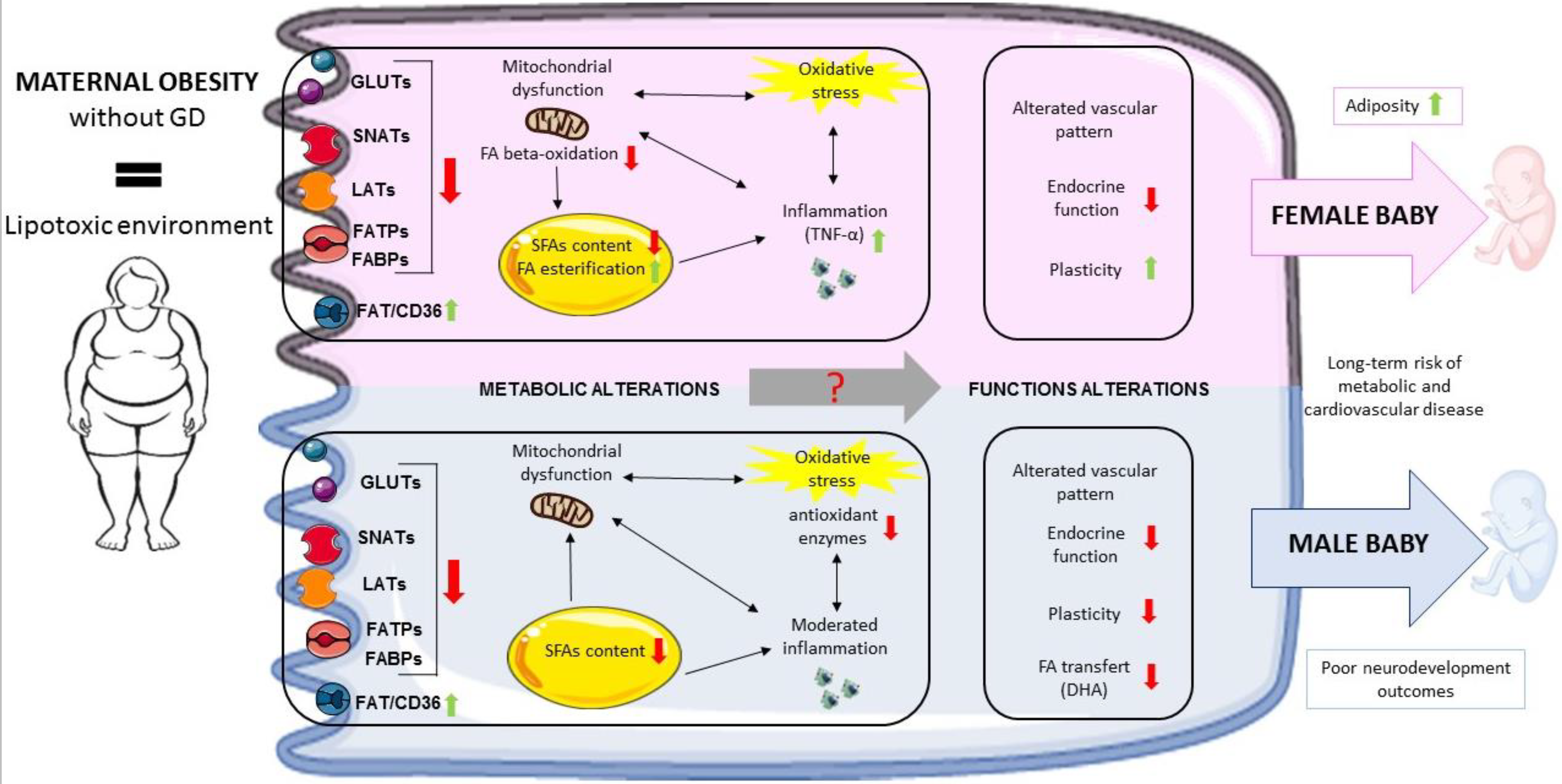

5.3. Impact of Maternal Obesity on Placental Lipid Metabolism

5.3.1. Fatty Acids (FAs)

5.3.2. Sphingolipids

6. Impact of Maternal Obesity on Placental Inflammatory/Immune Status

7. Impact of Maternal Obesity on Placental Oxidative Status

8. Impact of Maternal Obesity on the Placental Transcriptome

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chooi, Y.C.; Ding, C.; Magkos, F. The Epidemiology of Obesity. Metabolism 2019, 92, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2015 Eastern Mediterranean Region Obesity Collaborators. Burden of Obesity in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease 2015 Study. Int. J. Public Health 2018, 63, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeve, Y.B.; Konje, J.C.; Doshani, A. Placental Dysfunction in Obese Women and Antenatal Surveillance Strategies. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2015, 29, 350–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitanchez, D.; Jacqueminet, S.; Nizard, J.; Tanguy, M.-L.; Ciangura, C.; Lacorte, J.-M.; De Carne, C.; L’Hélias, L.F.; Chavatte-Palmer, P.; Charles, M.-A.; et al. Effect of Maternal Obesity on Birthweight and Neonatal Fat Mass: A Prospective Clinical Trial. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boney, C.M.; Verma, A.; Tucker, R.; Vohr, B.R. Metabolic Syndrome in Childhood: Association with Birth Weight, Maternal Obesity, and Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Pediatrics 2005, 115, e290–e296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, D.A.; Lithell, H.O.; Vagero, D.; Koupilova, I.; Mohsen, R.; Berglund, L.; Lithell, U.-B.; McKeigue, P.M. Reduced Fetal Growth Rate and Increased Risk of Death from Ischaemic Heart Disease: Cohort Study of 15,000 Swedish Men and Women Born 1915–1929. BMJ 1998, 317, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harder, T.; Plagemann, A.; Harder, A. Birth Weight and Subsequent Risk of Childhood Primary Brain Tumors: A Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2008, 168, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, D.J.; Powell, T.L.; Barrett, E.S.; Hardy, D.B. Developmental Origins of Metabolic Diseases. Physiol. Rev. 2021, 101, 739–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, J.M.; Luo, S.; Chow, T.; Herting, M.; Xiang, A.H.; Page, K.A. Sex Differences in the Association between Prenatal Exposure to Maternal Obesity and Hippocampal Volume in Children. Brain Behav. 2020, 10, e01522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogues, P.; Dos Santos, E.; Couturier-Tarrade, A.; Berveiller, P.; Arnould, L.; Lamy, E.; Grassin-Delyle, S.; Vialard, F.; Dieudonne, M.-N. Maternal Obesity Influences Placental Nutrient Transport, Inflammatory Status, and Morphology in Human Term Placenta. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 106, e1880–e1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatanaka, T.; Huang, W.; Wang, H.; Sugawara, M.; Prasad, P.D.; Leibach, F.H.; Ganapathy, V. Primary Structure, Functional Characteristics and Tissue Expression Pattern of Human ATA2, a Subtype of Amino Acid Transport System A. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2000, 1467, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansson, N.; Rosario, F.J.; Gaccioli, F.; Lager, S.; Jones, H.N.; Roos, S.; Jansson, T.; Powell, T.L. Activation of Placental mTOR Signaling and Amino Acid Transporters in Obese Women Giving Birth to Large Babies. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 98, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, A.C.; Powell, T.L.; Jansson, T. Placental Function in Maternal Obesity. Clin. Sci. 2020, 134, 961–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, V.H.J.; Smith, J.; McLea, S.A.; Heizer, A.B.; Richardson, J.L.; Myatt, L. Effect of Increasing Maternal Body Mass Index on Oxidative and Nitrative Stress in The Human Placenta. Placenta 2009, 30, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubé, E.; Gravel, A.; Martin, C.; Desparois, G.; Moussa, I.; Ethier-Chiasson, M.; Forest, J.C.; Giguére, Y.; Masse, A.; Lafond, J. Modulation of Fatty Acid Transport and Metabolism by Maternal Obesity in the: Human Full-Term Placenta. Biol. Reprod. 2012, 87, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabuig-Navarro, V.; Haghiac, M.; Minium, J.; Glazebrook, P.; Ranasinghe, G.C.; Hoppel, C.; De-Mouzon, S.H.; Catalano, P.; O’Tierney-Ginn, P. Effect of Maternal Obesity on Placental Lipid Metabolism. Endocrinology 2017, 158, 2543–2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, L.; Myatt, L. Sexual Dimorphism in the Effect of Maternal Obesity on Antioxidant Defense Mechanisms in the Human Placenta. Placenta 2017, 51, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, T.L.; Barner, K.; Madi, L.; Armstrong, M.; Manke, J.; Uhlson, C.; Jansson, T.; Ferchaud-Roucher, V. Sex-Specific Responses in Placental Fatty Acid Oxidation, Esterification and Transfer Capacity to Maternal Obesity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2021, 1866, 158861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon-Garcia, S.M.; Roeder, H.A.; Nelson, K.K.; Liao, X.; Pizzo, D.P.; Laurent, L.C.; Parast, M.M.; LaCoursiere, D.Y. Maternal Obesity and Sex-Specific Differences in Placental Pathology. Placenta 2016, 38, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Évain-Brion, D.; Malassiné, A.; Frydman, R. Le Placenta Humain; Ed. Médicales Internationales: Cachan, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Carbillon, L.; Uzan, M.; Challier, J.-C.; Merviel, P.; Uzan, S. Fetal-Placental and Decidual-Placental Units: Role of Endocrine and Paracrine Regulations in Parturition. Fetal Diagn. Ther. 2000, 15, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aplin, J.D. Developmental Cell Biology of Human Villous Trophoblast: Current Research Problems. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2010, 54, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knöfler, M.; Pollheimer, J. Human Placental Trophoblast Invasion and Differentiation: A Particular Focus on Wnt Signaling. Front. Genet. 2013, 4, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, G.J.; Jauniaux, E.; Charnock-Jones, D.S. The Influence of the Intrauterine Environment on Human Placental Development. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2010, 54, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Bouteiller, P.; Legrand-Abravanel, F.; Solier, C. Soluble HLA-G1 at the Materno-Foetal Interface—A Review. Placenta 2003, 24 (Suppl. A), S10–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanellopoulos-Langevin, C.; Caucheteux, S.M.; Verbeke, P.; Ojcius, D.M. Tolerance of the Fetus by the Maternal Immune System: Role of Inflammatory Mediators at the Feto-Maternal Interface. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. RB&E 2003, 1, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toufaily, C.; Vargas, A.; Lemire, M.; Lafond, J.; Rassart, É.; Barbeau, B. MFSD2a, the Syncytin-2 Receptor, Is Important for Trophoblast Fusion. Placenta 2013, 34, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malassiné, A.; Blaise, S.; Handschuh, K.; Lalucque, H.; Dupressoir, A.; Evain-Brion, D.; Heidmann, T. Expression of the Fusogenic HERV-FRD Env Glycoprotein (Syncytin 2) in Human Placenta Is Restricted to Villous Cytotrophoblastic Cells. Placenta 2007, 28, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellicer, A.; Dominguez, F.; Remohi, J.; Simón, C. Molecular Basis of Implantation. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2002, 5 (Suppl. 1), 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, M.H.; Dos Santos, E.; Rodriguez, Y.; Priou, C.; Berveiller, P.; Vialard, F.; Dieudonné, M.-N. Influence of Maternal Obesity on Human Trophoblast Differentiation: The Role of Mitochondrial Status. Reprod. Biol. 2022, 22, 100650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farley, D.M.; Choi, J.; Dudley, D.J.; Li, C.; Jenkins, S.L.; Myatt, L.; Nathanielsz, P.W. Placental Amino Acid Transport and Placental Leptin Resistance in Pregnancies Complicated by Maternal Obesity. Placenta 2010, 31, 718–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogues, P.; Dos Santos, E.; Jammes, H.; Berveiller, P.; Arnould, L.; Vialard, F.; Dieudonné, M.N. Maternal Obesity Influences Expression and DNA Methylation of the Adiponectin and Leptin Systems in Human Third-Trimester Placenta. Clin. Epigenet. 2019, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, E.A.; Wolfe, M.W. Adiponectin Attenuation of Endocrine Function within Human Term Trophoblast Cells. Endocrinology 2009, 150, 4358–4365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benaitreau, D.; Santos, E.D.; Leneveu, M.C.; De Mazancourt, P.; Pecquery, R.; Dieudonné, M.N. Adiponectin Promotes Syncytialisation of BeWo Cell Line and Primary Trophoblast Cells. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2010, 8, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fakhr, Y.; Brindley, D.N.; Hemmings, D.G. Physiological and Pathological Functions of Sphingolipids in Pregnancy. Cell. Signal. 2021, 85, 110041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khan, A.; Aye, I.L.; Barsoum, I.; Borbely, A.; Cebral, E.; Cerchi, G.; Clifton, V.L.; Collins, S.; Cotechini, T.; Davey, A.; et al. IFPA Meeting 2010 Workshops Report II: Placental Pathology; Trophoblast Invasion; Fetal Sex; Parasites and the Placenta; Decidua and Embryonic or Fetal Loss; Trophoblast Differentiation and Syncytialisation. Placenta 2011, 32 (Suppl. 2), S90–S99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mele, J.; Muralimanoharan, S.; Maloyan, A.; Myatt, L. Impaired Mitochondrial Function in Human Placenta with Increased Maternal Adiposity. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 307, E419–E425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, F.; Kiriakidou, M.; Strauss, J.F. Structural and Functional Changes in Mitochondria Associated with Trophoblast Differentiation: Methods to Isolate Enriched Preparations of Syncytiotrophoblast Mitochondria. Endocrinology 1997, 138, 2172–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraichard, C.; Bonnet, F.; Garnier, A.; Hébert-Schuster, M.; Bouzerara, A.; Gerbaud, P.; Ferecatu, I.; Fournier, T.; Hernandez, I.; Trabado, S.; et al. Placental Production of Progestins Is Fully Effective in Villous Cytotrophoblasts and Increases with the Syncytiotrophoblast Formation. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2020, 499, 110586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, D.D.L.R.; Zarco-Zavala, M.; Olvera-Sanchez, S.; Pardo, J.P.; Juarez, O.; Martinez, F.; Mendoza-Hernandez, G.; García-Trejo, J.J.; Flores-Herrera, O. Atypical Cristae Morphology of Human Syncytiotrophoblast Mitochondria: Role for Complex V. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 23911–23919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poidatz, D.; Dos Santos, E.; Gronier, H.; Vialard, F.; Maury, B.; De Mazancourt, P.; Dieudonné, M.-N. Trophoblast Syncytialisation Necessitates Mitochondrial Function through Estrogen-Related Receptor-γ Activation. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2015, 21, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashkovskaia, N.; Gey, U.; Rödel, G. Mitochondrial ROS Direct the Differentiation of Murine Pluripotent P19 Cells. Stem Cell Res. 2018, 30, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, O.; Dekker Nitert, M.; Gallo, L.A.; Vejzovic, M.; Fisher, J.J.; Perkins, A.V. Review: Placental Mitochondrial Function and Structure in Gestational Disorders. Placenta 2017, 54, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, M.; Sferruzzi-Perri, A.N. Placental Mitochondrial Function in Response to Gestational Exposures. Placenta 2021, 104, 124–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myatt, L.; Maloyan, A. Obesity and Placental Function. Semin. Reprod. Med. 2016, 34, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastman, A.J.; Moore, R.E.; Townsend, S.D.; Gaddy, J.A.; Aronoff, D.M. The Influence of Obesity and Associated Fatty Acids on Placental Inflammation. Clin. Ther. 2021, 43, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, K.A.; Riley, S.C.; Reynolds, R.M.; Barr, S.; Evans, M.; Statham, A.; Hor, K.; Jabbour, H.N.; Norman, J.E.; Denison, F.C. Placental Structure and Inflammation in Pregnancies Associated with Obesity. Placenta 2011, 32, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loardi, C.; Falchetti, M.; Prefumo, F.; Facchetti, F.; Frusca, T. Placental Morphology in Pregnancies Associated with Pregravid Obesity. J. Matern. Neonatal Med. 2016, 29, 2611–2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andres, R.L.; Kuyper, W.; Resnik, R.; Piacquadio, K.M.; Benirschke, K. The Association of Maternal Floor Infarction of the Placenta with Adverse Perinatal Outcome. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1990, 163, 935–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brett, K.E.; Ferraro, Z.M.; Yockell-Lelievre, J.; Gruslin, A.; Adamo, K.B. Maternal-Fetal Nutrient Transport in Pregnancy Pathologies: The Role of the Placenta. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 16153–16185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauguel-de Mouzon, S.; Challier, J.C.; Kacemi, A.; Caüzac, M.; Malek, A.; Girard, J. The GLUT3 Glucose Transporter Isoform Is Differentially Expressed within Human Placental Cell Types. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1997, 82, 2689–2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, T.; Wennergren, M.; Illsley, N.P. Glucose Transporter Protein Expression in Human Placenta throughout Gestation and in Intrauterine Growth Retardation. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1993, 77, 1554–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James-Allan, L.B.; Arbet, J.; Teal, S.B.; Powell, T.L.; Jansson, T. Insulin Stimulates GLUT4 Trafficking to the Syncytiotrophoblast Basal Plasma Membrane in the Human Placenta. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 104, 4225–4238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolahi, K.S.; Valent, A.M.; Thornburg, K.L. Cytotrophoblast, Not Syncytiotrophoblast, Dominates Glycolysis and Oxidative Phosphorylation in Human Term Placenta. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leduc, L.; Levy, E.; Bouity-Voubou, M.; Delvin, E. Fetal Programming of Atherosclerosis: Possible Role of the Mitochondria. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2010, 149, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brombach, C.; Tong, W.; Giussani, D.A. Maternal Obesity: New Placental Paradigms Unfolded. Trends Mol. Med. 2022, 28, 823–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, P.D.; Wang, H.; Huang, W.; Kekuda, R.; Rajan, D.P.; Leibach, F.H.; Ganapathy, V. Human LAT1, a Subunit of System L Amino Acid Transporter: Molecular Cloning and Transport Function. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999, 255, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda, M.; Fernández, E.; Torrents, D.; Estévez, R.; López, C.; Camps, M.; Lloberas, J.; Zorzano, A.; Palacín, M. Identification of a Membrane Protein, LAT-2, That Co-Expresses with 4F2 Heavy Chain, an L-Type Amino Acid Transport Activity with Broad Specificity for Small and Large Zwitterionic Amino Acids. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 19738–19744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desforges, M.; Mynett, K.J.; Jones, R.L.; Greenwood, S.L.; Westwood, M.; Sibley, C.P.; Glazier, J.D. The SNAT4 Isoform of the System A Amino Acid Transporter Is Functional in Human Placental Microvillous Plasma Membrane. J. Physiol. 2009, 587, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Huang, W.; Sugawara, M.; Devoe, L.D.; Leibach, F.H.; Prasad, P.D.; Ganapathy, V. Cloning and Functional Expression of ATA1, a Subtype of Amino Acid Transporter A, from Human Placenta. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000, 273, 1175–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, L.A.; Barrett, H.L.; Dekker Nitert, M. Review: Placental Transport and Metabolism of Energy Substrates in Maternal Obesity and Diabetes. Placenta 2017, 54, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauguel-de Mouzon, S.; Lepercq, J.; Catalano, P. The Known and Unknown of Leptin in Pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 194, 1537–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaughan, O.R.; Rosario, F.J.; Powell, T.L.; Jansson, T. Regulation of Placental Amino Acid Transport and Fetal Growth. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2017, 145, 217–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ditchfield, A.M.; Desforges, M.; Mills, T.A.; Glazier, J.D.; Wareing, M.; Mynett, K.; Sibley, C.P.; Greenwood, S.L. Maternal Obesity Is Associated with a Reduction in Placental Taurine Transporter Activity. Int. J. Obes. 2015, 39, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fattuoni, C.; Mandò, C.; Palmas, F.; Anelli, G.M.; Novielli, C.; Parejo Laudicina, E.; Savasi, V.M.; Barberini, L.; Dessì, A.; Pintus, R.; et al. Preliminary Metabolomics Analysis of Placenta in Maternal Obesity. Placenta 2018, 61, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauster, M.; Hiden, U.; van Poppel, M.; Frank, S.; Wadsack, C.; Hauguel-de Mouzon, S.; Desoye, G. Dysregulation of Placental Endothelial Lipase in Obese Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes 2011, 60, 2457–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafrir, E.; Khassis, S. Maternal-Fetal Fat Transport versus New Fat Synthesis in the Pregnant Diabetic Rat. Diabetologia 1982, 22, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura, M.T.; Demmelmair, H.; Krauss-Etschmann, S.; Nathan, P.; Dehmel, S.; Padilla, M.C.; Rueda, R.; Koletzko, B.; Campoy, C. Maternal BMI and Gestational Diabetes Alter Placental Lipid Transporters and Fatty Acid Composition. Placenta 2017, 57, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belcastro, L.; Ferreira, C.S.; Saraiva, M.A.; Mucci, D.B.; Murgia, A.; Lai, C.; Vigor, C.; Oger, C.; Galano, J.M.; Pinto, G.D.A.; et al. Decreased Fatty Acid Transporter fabp1 and Increased Isoprostanes and Neuroprostanes in the Human Term Placenta: Implications for Inflammation and Birth Weight in Maternal Pre-Gestational Obesity. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, T.; Thérond, P.; Handschuh, K.; Tsatsaris, V.; Evain-Brion, D. PPARgamma and Early Human Placental Development. Curr. Med. Chem. 2008, 15, 3011–3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Yang, H.; Ye, Y.; Ma, Z.; Kuhn, C.; Rahmeh, M.; Mahner, S.; Makrigiannakis, A.; Jeschke, U.; von Schönfeldt, V. Role of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors (PPARs) in Trophoblast Functions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, E433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaiff, W.T.; Carlson, M.G.; Smith, S.D.; Levy, R.; Nelson, D.M.; Sadovsky, Y. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor-Gamma Modulates Differentiation of Human Trophoblast in a Ligand-Specific Manner. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2000, 85, 3874–3881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabuig-Navarro, V.; Puchowicz, M.; Glazebrook, P.; Haghiac, M.; Minium, J.; Catalano, P.; Hauguel deMouzon, S.; O’Tierney-Ginn, P. Effect of ω-3 Supplementation on Placental Lipid Metabolism in Overweight and Obese Women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 103, 1064–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Bucher, M.; Myatt, L. Use of Glucose, Glutamine and Fatty Acids for Trophoblast Respiration in Lean, Obese and Gestational Diabetic Women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 104, 4178–4187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, S.A.; Chaurasia, B.; Holland, W.L. Metabolic Messengers: Ceramides. Nat. Metab. 2019, 1, 1051–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaurasia, B.; Summers, S.A. Ceramides—Lipotoxic Inducers of Metabolic Disorders. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 26, 538–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Field, B.C.; Gordillo, R.; Scherer, P.E. The Role of Ceramides in Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease Regulation of Ceramides by Adipokines. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 569250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, E.S.; Maynard, L.M.; Li, C. Trends in Mean Waist Circumference and Abdominal Obesity among US Adults, 1999–2012. JAMA 2014, 312, 1151–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, M.L.; Weber, A.; Roxlau, T.; Gaestel, M.; Kracht, M. Signal Integration, Crosstalk Mechanisms and Networks in the Function of Inflammatory Cytokines. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2011, 1813, 2165–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Wakkad, A.; Hassan, N.E.-M.; Sibaii, H.; El-Zayat, S.R. Proinflammatory, Anti-Inflammatory Cytokines and Adiponkines in Students with Central Obesity. Cytokine 2013, 61, 682–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muralimanoharan, S.; Guo, C.; Myatt, L.; Maloyan, A. Sexual Dimorphism in miR-210 Expression and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in the Placenta with Maternal Obesity. Int. J. Obes. 2015, 39, 1274–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lappas, M. Insulin-like Growth Factor-Binding Protein 1 and 7 Concentrations Are Lower in Obese Pregnant Women, Women with Gestational Diabetes and Their Fetuses. J. Perinatol. Off. J. Calif. Perinat. Assoc. 2015, 35, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webster, R.P.; Roberts, V.H.J.; Myatt, L. Protein Nitration in Placenta—Functional Significance. Placenta 2008, 29, 985–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saben, J.; Lindsey, F.; Zhong, Y.; Thakali, K.; Badger, T.M.; Andres, A.; Gomez-Acevedo, H.; Shankar, K. Maternal Obesity Is Associated with a Lipotoxic Placental Environment. Placenta 2014, 35, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malti, N.; Merzouk, H.; Merzouk, S.A.; Loukidi, B.; Karaouzene, N.; Malti, A.; Narce, M. Oxidative Stress and Maternal Obesity: Feto-Placental Unit Interaction. Placenta 2014, 35, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebert, J.F.; Myatt, L. Placental Mitochondrial Dysfunction with Metabolic Diseases: Therapeutic Approaches. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2021, 1867, 165967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hastie, R.; Lappas, M. The Effect of Pre-Existing Maternal Obesity and Diabetes on Placental Mitochondrial Content and Electron Transport Chain Activity. Placenta 2014, 35, 673–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros-Guzmán, A.K.; Carrasco-Legleu, C.E.; Levario-Carrillo, M.; Chávez-Corral, D.V.; Sánchez-Ramírez, B.; Mariñelarena-Carrillo, E.O.; Guerrero-Salgado, F.; Reza-López, S.A. Prepregnancy Obesity, Maternal Dietary Intake, and Oxidative Stress Biomarkers in the Fetomaternal Unit. Biomed. Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 5070453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altmäe, S.; Segura, M.T.; Esteban, F.J.; Bartel, S.; Brandi, P.; Irmler, M.; Beckers, J.; Demmelmair, H.; López-Sabater, C.; Koletzko, B.; et al. Maternal Pre-Pregnancy Obesity Is Associated with Altered Placental Transcriptome. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sureshchandra, S.; Marshall, N.E.; Wilson, R.M.; Barr, T.; Rais, M.; Purnell, J.Q.; Thornburg, K.L.; Messaoudi, I. Inflammatory Determinants of Pregravid Obesity in Placenta and Peripheral Blood. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedlmeier, E.-M.; Brunner, S.; Much, D.; Pagel, P.; Ulbrich, S.E.; Meyer, H.H.; Amann-Gassner, U.; Hauner, H.; Bader, B.L. Human Placental Transcriptome Shows Sexually Dimorphic Gene Expression and Responsiveness to Maternal Dietary N-3 Long-Chain Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Intervention during Pregnancy. BMC Genom. 2014, 15, 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howerton, C.L.; Bale, T.L. Targeted Placental Deletion of OGT Recapitulates the Prenatal Stress Phenotype Including Hypothalamic Mitochondrial Dysfunction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 9639–9644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bale, T.L. The Placenta and Neurodevelopment: Sex Differences in Prenatal Vulnerability. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2016, 18, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Placental Function | Maternal Obesity Impact | |

|---|---|---|

| Endocrine function | hCG Leptin Progesterone Leptin receptor Adiponectin receptor |  |

| Mitochondrial function | ERR-γ expression PPAR-γ/α expression PGC-1α expression Mitochondrial DNA content Mitochondrial respiration ATP production |  |

| Oxidative stress | Lipid peroxydation Protein carbonylation Protein nitrosylation Catalase Superoxide dismutase |  |

| Inflammation | Jun kinase Mitogen-activated protein kinase Janus-activated kinase TNF-α |  |

| Epigenetic changes | Leptin DNA methylation Adiponectin DNA methylation H3K2me3 |  |

| FA esterification | Free carnitine Diacylglycerol-o-transferase |  |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santos, E.D.; Hernández, M.H.; Sérazin, V.; Vialard, F.; Dieudonné, M.-N. Human Placental Adaptive Changes in Response to Maternal Obesity: Sex Specificities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9770. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24119770

Santos ED, Hernández MH, Sérazin V, Vialard F, Dieudonné M-N. Human Placental Adaptive Changes in Response to Maternal Obesity: Sex Specificities. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023; 24(11):9770. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24119770

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantos, Esther Dos, Marta Hita Hernández, Valérie Sérazin, François Vialard, and Marie-Noëlle Dieudonné. 2023. "Human Placental Adaptive Changes in Response to Maternal Obesity: Sex Specificities" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 24, no. 11: 9770. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24119770

APA StyleSantos, E. D., Hernández, M. H., Sérazin, V., Vialard, F., & Dieudonné, M.-N. (2023). Human Placental Adaptive Changes in Response to Maternal Obesity: Sex Specificities. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(11), 9770. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24119770