The Association of Selected GWAS Reported AD Risk Loci with CSF Biomarker Levels and Cognitive Decline in Slovenian Patients

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Patients’ Characteristic

2.2. Association of Investigated SNPs with Cognitive Impairment and AD Susceptibility

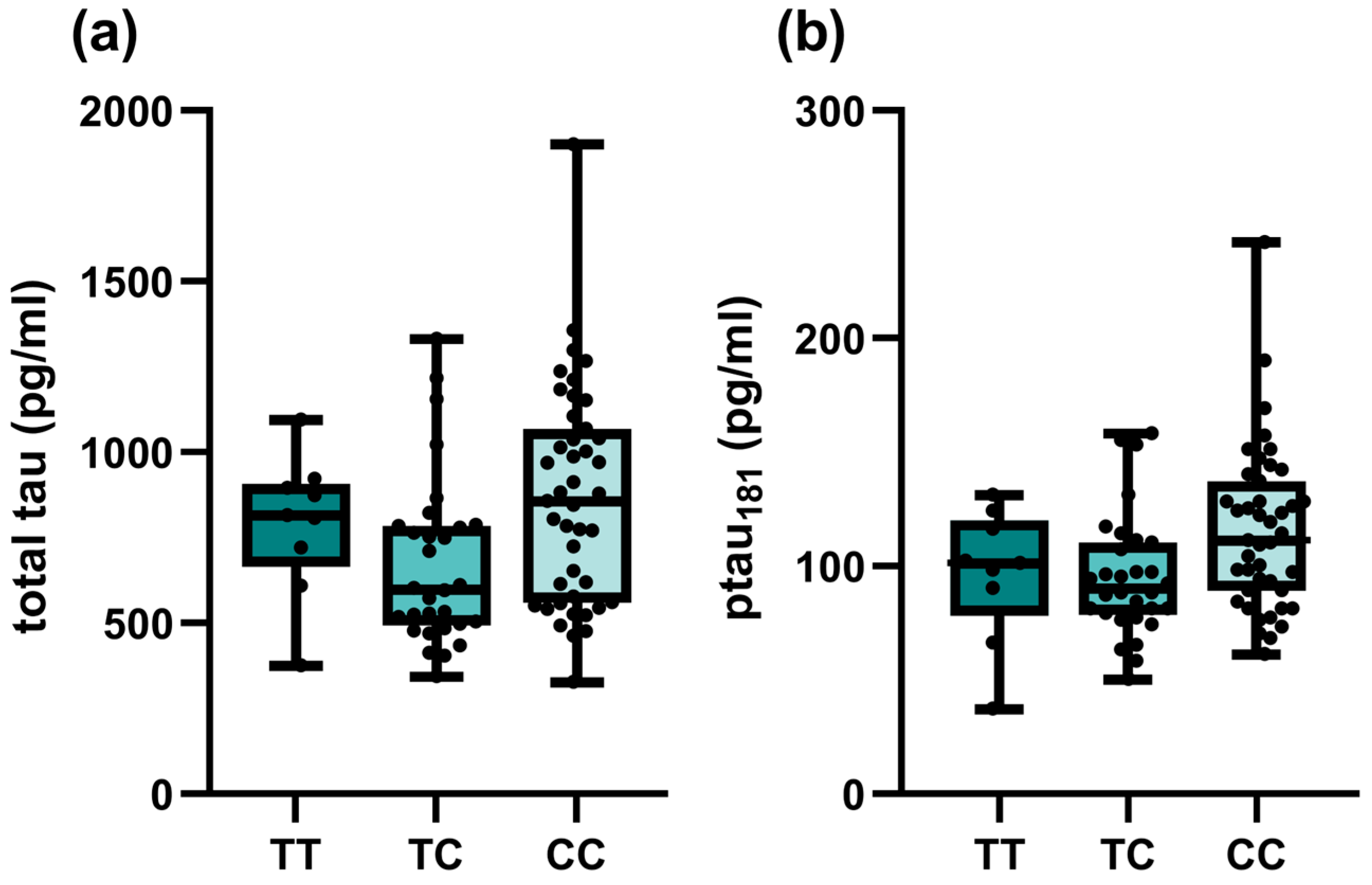

2.3. Association of Investigated SNPs with CSF Biomarker Levels and MMSE

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Subjects

4.2. Assessment

4.3. Cerebrospinal Fluid Analysis

4.4. Genotyping

4.5. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alzheimer’s Association 2023 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2023, 19, 1598–1695. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hebert, L.E.; Bienias, J.L.; Aggarwal, N.T.; Wilson, R.S.; Bennett, D.A.; Shah, R.C.; Evans, D.A. Change in risk of Alzheimer disease over time. Neurology 2010, 75, 786–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayeux, R.; Stern, Y. Epidemiology of Alzheimer Disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012, 2, a006239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masters, C.L.; Bateman, R.; Blennow, K.; Rowe, C.C.; Sperling, R.A.; Cummings, J.L. Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2015, 1, 15056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blennow, K.; Hampel, H.; Weiner, M.; Zetterberg, H. Cerebrospinal fluid and plasma biomarkers in Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2010, 6, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efthymiou, A.G.; Goate, A.M. Late onset Alzheimer’s disease genetics implicates microglial pathways in disease risk. Mol. Neurodegener. 2017, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, M.S.; DeKosky, S.T.; Dickson, D.; Dubois, B.; Feldman, H.H.; Fox, N.C.; Gamst, A.; Holtzman, D.M.; Jagust, W.J.; Petersen, R.C.; et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2011, 7, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, A.; Tardiff, S.; Dye, C.; Arrighi, H.M. Rate of Conversion from Prodromal Alzheimer’s Disease to Alzheimer’s Dementia: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Dis. Extra 2013, 3, 320–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naj, A.C.; Schellenberg, G.D. Genomic variants, genes, and pathways of Alzheimer’s disease: An overview. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2017, 174, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, J.C.; Ibrahim-Verbaas, C.A.; Harold, D.; Naj, A.C.; Sims, R.; Bellenguez, C.; Jun, G.; DeStefano, A.L.; Bis, J.C.; Beecham, G.W.; et al. Meta-analysis of 74,046 individuals identifies 11 new susceptibility loci for Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 1452–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellenguez, C.; Küçükali, F.; Jansen, I.E.; Kleineidam, L.; Moreno-Grau, S.; Amin, N.; Naj, A.C.; Campos-Martin, R.; Grenier-Boley, B.; Andrade, V.; et al. New insights into the genetic etiology of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Nat. Genet. 2022, 54, 412–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wightman, D.P.; Jansen, I.E.; Savage, J.E.; Shadrin, A.A.; Bahrami, S.; Holland, D.; Rongve, A.; Børte, S.; Winsvold, B.S.; Drange, O.K.; et al. A genome-wide association study with 1,126,563 individuals identifies new risk loci for Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Genet. 2021, 53, 1276–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, I.E.; Savage, J.E.; Watanabe, K.; Bryois, J.; Williams, D.M.; Steinberg, S.; Sealock, J.; Karlsson, I.K.; Hägg, S.; Athanasiu, L.; et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies new loci and functional pathways influencing Alzheimer’s disease risk. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannis, V.I.; Breslow, J.L.; Utermann, G.; Mahley, R.W.; Weisgraber, K.H.; Havel, R.J.; Goldstein, J.L.; Brown, M.S.; Schonfeld, G.; Hazzard, W.R.; et al. Proposed nomenclature of apoE isoproteins, apoE genotypes, and phenotypes. J. Lipid Res. 1982, 23, 911–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashford, J.W. APOE Genotype Effects on Alzheimer’s Disease Definition of AD Epidemiology of AD. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2004, 23, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corder, E.H.; Saunders, A.M.; Strittmatter, W.J.; Schmechel, D.E.; Gaskell, P.C.; Small, G.W.; Roses, A.D.; Haines, J.L.; Pericak-Vance, M.A. Gene Dose of Apolipoprotein E Type 4 Allele and the Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease in Late Onset Families. Science 1993, 261, 921–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaelson, D.M. APOE ε4: The most prevalent yet understudied risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. 2014, 10, 861–868. Alzheimers Dement. 2014, 10, 861–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogrinc, D.; Goričar, K.; Dolžan, V. Genetic Variability in Molecular Pathways Implicated in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Comprehensive Review. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humphries, A.D.; Streimann, I.C.; Stojanovski, D.; Johnston, A.J.; Yano, M.; Hoogenraad, N.J.; Ryan, M.T. Dissection of the mitochondrial import and assembly pathway for human Tom40. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 11535–11543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olgiati, P.; Politis, A.M.; Papadimitriou, G.N.; De Ronchi, D.; Serretti, A. Genetics of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease: Update from the Alzgene database and analysis of shared pathways. Int. J. Alzheimers. Dis. 2011, 11, 832379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amitay, M.; Shurki, A. The structure of G117H mutant of butyrylcholinesterase: Nerve agents scavenger. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 2009, 77, 370–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darvesh, S.; Hopkins, D.A.; Geula, C. Neurobiology of butyrylcholinesterase. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2003, 4, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehoe, P.G. The coming of age of the angiotensin hypothesis in Alzheimer’s disease: Progress toward disease prevention and treatment? J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018, 62, 1443–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddick, P.C.G.; Larson, J.L.; Rathore, N.; Bhangale, T.R.; Phung, Q.T.; Srinivasan, K.; Hansen, D.V.; Lill, J.R.; Pericak-Vance, M.A.; Haines, J.; et al. A Common Variant of IL-6R is Associated with Elevated IL-6 Pathway Activity in Alzheimer’s Disease Brains. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2017, 56, 1037–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grupe, A.; Abraham, R.; Li, Y.; Rowland, C.; Hollingworth, P.; Morgan, A.; Jehu, L.; Segurado, R.; Stone, D.; Schadt, E.; et al. Evidence for novel susceptibility genes for late-onset Alzheimer’s disease from a genome-wide association study of putative functional variants. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2007, 16, 865–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harold, D.; Abraham, R.; Hollingworth, P.; Sims, R.; Hamshere, M.; Pahwa, J.S.; Moskvina, V.; Williams, A.; Jones, N.; Thomas, C.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Variants at CLU and PICALM Associated with Alzheimer’s Disease, and Shows Evidence for Additional Susceptibility Genes. Nat. Genet. 2009, 41, 1088–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, S.J.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, S.Y.; You, S.; Kim, M.J.; Lee, J.Y.; Koh, J. Association of GWAS top hits with late-onset alzheimer disease in korean population. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2013, 27, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seshadri, S.; Fitzpatrick, A.L.; Ikram, M.A.; DeStefano, A.L.; Gudnason, V.; Boada, M.; Bis, J.C.; Smith, A.V.; Carassquillo, M.M.; Lambert, J.C.; et al. Genome-wide analysis of genetic loci associated with Alzheimer disease. JAMA-J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2010, 303, 1832–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feulner, T.M.; Laws, S.M.; Friedrich, P.; Wagenpfeil, S.; Wurst, S.H.R.; Riehle, C.; Kuhn, K.A.; Krawczak, M.; Schreiber, S.; Nikolaus, S.; et al. Examination of the current top candidate genes for AD in a genome-wide association study. Mol. Psychiatry 2010, 15, 756–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijsman, E.M.; Pankratz, N.D.; Choi, Y.; Rothstein, J.H.; Faber, K.M.; Cheng, R.; Lee, J.H.; Bird, T.D.; Bennett, D.A.; Diaz-Arrastia, R.; et al. Genome-wide association of familial late-onset alzheimer’s disease replicates BIN1 and CLU and nominates CUGBP2 in interaction with APOE. PLoS Genet. 2011, 7, e1001308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laumet, G.; Chouraki, V.; Grenier-Boley, B.; Legry, V.; Heath, S.; Zelenika, D.; Fievet, N.; Hannequin, D.; Delepine, M.; Pasquier, F.; et al. Systematic analysis of candidate genes for Alzheimer’s disease in a French, genome-wide association study. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2010, 20, 1181–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blue, E.E.; Cheng, A.; Chen, S.; Yu, C.E. Association of Uncommon, Noncoding Variants in the APOE Region with Risk of Alzheimer Disease in Adults of European Ancestry. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagnoli, S.; Piaceri, I.; Tedde, A.; Bessi, V.; Bracco, L.; Sorbi, S.; Nacmias, B. Tomm40 polymorphisms in Italian Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia patients. Neurol. Sci. 2013, 34, 995–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.C.; Chang, S.C.; Lee, Y.S.; Ho, W.M.; Huang, Y.H.; Wu, Y.Y.; Chu, Y.C.; Wu, K.H.; Wei, L.S.; Wang, H.L.; et al. TOMM40 Genetic Variants Cause Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, X.; Liu, C.; Liu, K.; Cong, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, R.; Fa, W.; Tian, N.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, N.; et al. Association and interaction of TOMM40 and PVRL2 with plasma amyloid-β and Alzheimer’s disease among Chinese older adults: A population-based study. Neurobiol. Aging 2022, 113, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gok, M.; Madrer, N.; Zorbaz, T.; Bennett, E.R.; Greenberg, D.; Bennett, D.A.; Soreq, H. Altered levels of variant cholinesterase transcripts contribute to the imbalanced cholinergic signaling in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2022, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, F.; Cui, Y.; Zheng, L.; Wei, Y. Association between ACE gene polymorphisms and Alzheimer’s disease in Han population in Hebei Peninsula. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2017, 10, 10134–10139. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Swaminathan, S.; Shen, L.; Risacher, S.L.; Nho, K.; Foroud, T.; Shaw, L.M.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Potkin, S.G.; Huentelman, M.J.; et al. Genome-wide association study of CSF biomarkers Aβ1-42, t-tau, and p-tau181p in the ADNI cohort. Neurology 2011, 76, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruchaga, C.; Kauwe, J.S.K.; Harari, O.; Jin, S.C.; Cai, Y.; Karch, C.M.; Benitez, B.A.; Jeng, A.T.; Skorupa, T.; Carrell, D.; et al. GWAS of cerebrospinal fluid tau levels identifies risk variants for Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 2013, 78, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanan, V.K.; Risacher, S.L.; Nho, K.; Kim, S.; Swaminathan, S.; Shen, L.; Foroud, T.M.; Hakonarson, H.; Huentelman, M.J.; Aisen, P.S.; et al. APOE and BCHE as modulators of cerebral amyloid deposition: A florbetapir PET genome-wide association study. Mol. Psychiatry 2014, 19, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumitrescu, L.; Barnes, L.L.; Thambisetty, M.; Beecham, G.; Kunkle, B.; Bush, W.S.; Gifford, K.A.; Chibnik, L.B.; Mukherjee, S.; De Jager, P.L.; et al. Sex differences in the genetic predictors of Alzheimer’s pathology. Brain 2019, 142, 2581–2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oatman, S.R.; Reddy, J.S.; Quicksall, Z.; Carrasquillo, M.M.; Wang, X.; Liu, C.C.; Yamazaki, Y.; Nguyen, T.T.; Malphrus, K.; Heckman, M.; et al. Genome-wide association study of brain biochemical phenotypes reveals distinct genetic architecture of Alzheimer’s disease related proteins. Mol. Neurodegener. 2023, 18, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damotte, V.; van der Lee, S.J.; Chouraki, V.; Grenier-Boley, B.; Simino, J.; Adams, H.; Tosto, G.; White, C.; Terzikhan, N.; Cruchaga, C.; et al. Plasma amyloid β levels are driven by genetic variants near APOE, BACE1, APP, PSEN2: A genome-wide association study in over 12,000 non-demented participants. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2021, 17, 1663–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, M.B.R.; Araújo, G.S.; Costa, I.G.; Oliveira, J.R.M. Combined Genome-Wide CSF Aβ-42’s Associations and Simple Network Properties Highlight New Risk Factors for Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2016, 58, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selkoe, D.J. Alzheimer’s Disease: Genes, Proteins, and Therapy. Physiol. Rev. 2001, 81, 741–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golde, T.E.; Eckman, C.B.; Younkin, S.G. Biochemical detection of Aβ isoforms: Implications for pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Mol. Basis Dis. 2000, 1502, 172–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, L.; Prabhu, B.M.; Galati, D.F.; Avadhani, N.G.; Anandatheerthavarada, H.K. Accumulation of amyloid precursor protein in the mitochondrial import channels of human Alzheimer’s disease brain is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 9057–9068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gottschalk, W.K.; Lutz, M.W.; He, Y.T.; Saunders, A.M.; Daniel, K.; Roses, A.D.; Chiba-falek, O.; Hill, C. The Broad Impact of TOM40 on Neurodegenerative Diseases in Aging. J. Park. Dis. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2014, 1, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Li, C.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, H.; Jin, T.; Chen, S. Meta-analysis of the rs2075650 polymorphism and risk of Alzheimer disease. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2016, 28, 805–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Zhao, J.; Xu, B.; Ma, X.; Dai, Q.; Li, T.; Xue, F.; Chen, B. The TOMM40 gene rs2075650 polymorphism contributes to Alzheimer’s disease in Caucasian, and Asian populations. Neurosci. Lett. 2016, 628, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulminski, A.M.; Jain-Washburn, E.; Loiko, E.; Loika, Y.; Feng, F.; Culminskaya, I. Associations of the APOE ε2 and ε4 alleles and polygenic profiles comprising APOE-TOMM40-APOC1 variants with Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers. Aging 2022, 14, 9782–9804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermey, G.; Riedel, I.B.; Rezgaoui, M.; Westergaard, U.B.; Schaller, C.; Hermans-Borgmeyer, I. SorCS1, a member of the novel sorting receptor family, is localized in somata and dendrites of neurons throughout the murine brain. Neurosci. Lett. 2001, 313, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Xu, J.; Wang, Y.; Tang, H.; Deng, Y.; Ren, R.; Wang, G.; Niu, W.; Ma, J.; Wu, Y.; et al. The Genetic Variation of SORCS1 Is Associated with Late-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease in Chinese Han Population. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e63621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edbauer, D.; Winkler, E.; Regula, J.T.; Pesold, B.; Steiner, H.; Haass, C. Reconstitution of γ-secretase activity. Nat. Cell Biol. 2003, 5, 486–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-H.; Park, I.; Youm, E.M.; Lee, S.; Park, J.-H.; Lee, J.; Lee, D.Y.; Byun, M.S.; Lee, J.H.; Yi, D.; et al. Novel Alzheimer’s disease risk variants identified based on whole-genome sequencing of APOE ε4 carriers. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.F.; Yu, J.T.; Zhang, W.; Wang, W.; Liu, Q.Y.; Ma, X.Y.; Ding, H.M.; Tan, L. SORCS1 and APOE polymorphisms interact to confer risk for late-onset Alzheimer’s disease in a Northern Han Chinese population. Brain Res. 2012, 1448, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arendt, T.; Brückner, M.K.; Lange, M.; Bigl, V. Changes in acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase in Alzheimer’s disease resemble embryonic development—A study of molecular forms. Neurochem. Int. 1992, 21, 381–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carson, K.A.; Geula, C.; Mesulam, M.-M. Electron microscopic localization of cholinesterase activity in Alzheimer brain tissue. Brain Res. 1991, 540, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darreh-Shori, T.; Siawesh, M.; Mousavi, M.; Andreasen, N.; Nordberg, A. Apolipoprotein ε4 Modulates Phenotype of Butyrylcholinesterase in CSF of Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2012, 28, 443–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolow, S.; Li, X.; Chen, L.; Taylor, K.D.; Rotter, J.I.; Rissman, R.A.; Aisen, P.S.; Apostolova, L.G. Deleterious Effect of Butyrylcholinesterase K-Variant in Donepezil Treatment of Mild Cognitive Impairment. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2017, 56, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reisberg, B.; Ferris, S.; De Leon, M.; Crook, T. The Global Deterioration Scale for assessment of primary degenerative dementia. Am. J. Psychiatry 1982, 139, 1136–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; ISBN 0-89042-555-8. [Google Scholar]

- Winblad, B.; Palmer, K.; Kivipelto, M.; Jelic, V.; Fratiglioni, L.; Wahlund, L.-O.; Nordberg, A.; Backman, L.; Albert, M.; Almkvist, O.; et al. Mild cognitive impairment - beyond controversies, towards a consensus: Report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. J. Intern. Med. 2004, 256, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogrinc, D.; Gregorič Kramberger, M.; Emeršič, A.; Čučnik, S.; Goričar, K.; Dolžan, V. Genetic Polymorphisms in Oxidative Stress and Inflammatory Pathways as Potential Biomarkers in Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perovnik, M.; Tomše, P.; Jamšek, J.; Emeršič, A.; Tang, C.; Eidelberg, D.; Trošt, M. Identification and validation of Alzheimer’s disease-related metabolic brain pattern in biomarker confirmed Alzheimer’s dementia patients. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11752 . [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, W.D.; Plummer, W.D.J. Power and sample size calculations: A review and computer program. Control. Clin. Trials 1990, 11, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Category/Unit | Cognitive Impairment | AD | MCI (AD) | MCI (NOT AD) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male, N (%) | 68 (46.9) | 35 (42.7) | 9 (32.1) | 24 (68.6) | 0.008 a |

| Female, N (%) | 77 (53.1) | 47 (57.3) | 19 (67.9) | 11 (31.4) | ||

| Age | Years, median (25–75%) | 76 (72–80) | 77 (73.75–80) | 75 (73–79.75) | 74 (67–78) | 0.039 b |

| Education | Years, median (25–75%) | 12 (10–14.25) [3] | 11.5 (8.5–12) [2] | 12 (12–16) [1] | 12 (11–15) | 0.022 b |

| Weight | kg, median (25–75%) | 70 (59–79.75) [25] | 67 (55.5–78) [17] | 67 (56–78) [9] | 75.5 (64.75–85) [3] | 0.011 b |

| BMI | kg/m2, median (25–75%) | 24.49 (20.99–27.01) [26] | 24.22 (20.23–26.61) [16] | 23.01 (20.45–27.54) [7] | 26.05 (23.74–28.57) [3] | 0.008 b |

| APOE status | APOE4 carriers, N (%) | 66 (45.5) | 43 (52.4) | 16 (57.1) | 7 (20) | 0.005 a |

| MMSE | Score, median (25–75%) | 24 (19.75–26) [27] | 20 (16–23) [19] | 27 (25.5–27) [7] | 26 (25–27) [9] | <0.001 b |

| Aβ42 | pg/mL, median (25–75%) | 740 (572.5–997.5) | 678.5 (542–771) | 648.5 (514.75–828) | 1305 (1119–1496) | <0.001 b |

| Aβ42/40 ratio | Median (25–75%) | 0.06 (0.05–0.08) [6] | 0.06 (0.04–0.06) [2] | 0.05 (0.04–0.06) [2] | 0.12 (0.09–0.14) [2] | <0.001 b |

| Total tau | pg/mL, median (25–75%) | 567 (418.5–879.5) | 771 (537–989) | 594 (463.25–910.75) | 311 (239–404) | <0.001 b |

| p-tau181 | pg/mL, median (25–75%) | 87 (64.5–116.5) | 98 (81–125.25) | 89 (77.25–128.5) | 50 (39–62) | 0.008 b |

| Gene | SNP | Genotype | AD N (%) | MCI N (%) | MCI (NOT AD) N (%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SORCS1 | rs1358030 | CC | 8 (9.8) | 4 (14.3) | 5 (14.3) | 0.467 |

| CT | 33 (40.2) | 14 (50) | 18 (51.4) | |||

| TT | 41 (50) | 10 (35.7) | 12 (34.3) | |||

| CT + TT | 74 (90.2) | 24 (85.7) | 30 (85.8) | Pdom = 0.639 | ||

| rs1416406 | TT | 9 (11) | 4 (14.3) | 2 (5.7) | 0.847 | |

| TC | 30 (36.6) | 9 (32.1) | 13 (37.1) | |||

| CC | 43 (52.4) | 15 (53.6) | 20 (57.1) | |||

| TC + CC | 73 (89) | 24 (85.7) | 33 (94.3) | Pdom = 0.528 | ||

| BCHE | rs1803274 | CC | 52 (63.4) | 19 (67.9) | 26 (74.3) | 0.741 |

| CT | 28 (34.1) | 8 (28.6) | 8 (22.9) | |||

| TT | 2 (2.4) | 1 (3.6) | 1 (2.9) | |||

| CT + TT | 30 (36.5) | 8 (28.6) | 9 (25.7) | Pdom = 1 | ||

| rs1799807 | TT | 78 (95.1) | 27 (96.4) | 34 (97.1) | 1 | |

| TC | 4 (4.9) | 1 (3.6) | 1 (2.9) | |||

| CC | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| TC + CC | 4 (4.9) | 1 (3.6) | 1 (2.9) | Pdom = 1 | ||

| TOMM40 | rs2075650 | AA | 42 (51.2) | 12 (42.9) | 26 (74.3) | 0.082 |

| AG | 34 (41.5) | 13 (46.4) | 7 (20) | |||

| GG | 6 (7.3) | 3 (10.7) | 2 (5.7) | |||

| AG + GG | 40 (49.8) | 16 (57.1) | 9 (25.7) | Pdom = 0.025 | ||

| rs157581 | TT | 28 (34.1) | 7 (25) | 23 (65.7) | 0.005 | |

| TC | 44 (53.7) | 17 (60.7) | 8 (22.9) | |||

| CC | 10 (12.2) | 4 (14.3) | 4 (11.4) | |||

| TC + CC | 54 (65.9) | 21 (75) | 12 (34.3) | Pdom = 0.001 | ||

| ACE | rs1800764 | CC | 21 (25.6) | 4 (14.3) | 4 (11.4) | 0.317 |

| CT | 38 (46.3) | 15 (53.6) | 16 (45.7) | |||

| TT | 23 (28) | 9 (32.1) | 15 (42.9) | |||

| CT + TT | 61 (74.4) | 24 (85.7) | 31 (88.6) | Pdom = 0.194 | ||

| rs4343 | GG | 27 (32.9) | 7 (25) | 8 (22.9) | 0.360 | |

| GA | 39 (47.6) | 13 (46.4) | 14 (40) | |||

| AA | 16 (19.5) | 8 (28.6) | 13 (37.1) | |||

| GA + AA | 55 (67.1) | 21 (75) | 27 (77.1) | Pdom = 0.506 | ||

| IL6 R | rs2228145 | AA | 31 (37.8) | 15 (53.6) | 14 (40) | 0.683 |

| AC | 43 (52.3) | 11 (39.3) | 17 (48.6) | |||

| CC | 8 (9.8) | 2 (7.1) | 4 (11.4) | |||

| AC + CC | 51 (62.2) | 13 (46.4) | 21 (60) | Pdom = 0.342 |

| SNP | Genotype | Aβ42 (pg/mL) | p | Aβ42/40 Ratio | p | Total tau (pg/mL) | p | p-tau (pg/mL) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SORCS1 rs1358030 | CC | 774 (560.5–1048) | 0.467 | 0.05 (0.04–0.08) | 0.792 | 769 (463.5–1240.5) | 0.301 | 95 (62.5–152) | 0.767 |

| CT | 740 (592.5–1114.5) | 0.06 (0.04–0.09) | 556 (379.5–849.5) | 84 (62.5–116) | |||||

| TT | 725 (538–877) | 0.06 (0.05–0.08) | 567 (427–878) | 87 (65–114) | |||||

| CT + TT | 735.5 (576.5–981.5) | Pdom = 0.701 | 0.06 (0.05–0.08) | Pdom = 0.533 | 557.5 (417.75–861.75) | Pdom = 0.148 | 86.5 (64.25–114.75) | Pdom = 0.499 | |

| SORCS1 rs1416406 | TT | 702 (570–916) | 0.944 | 0.06 (0.04–0.07) | 0.952 | 719 (461–894) | 0.175 | 90 (66–116) | 0.271 |

| TC | 744 (576.5–1066.5) | 0.06 (0.05–0.08) | 522.5 (411.75–774.25) | 81 (60.5–104.5) | |||||

| CC | 739 (566.5–1071.25) | 0.06 (0.04–0.09) | 615 (421.25–989) | 91 (66.5–126.5) | |||||

| TC + CC | 743.5 (573.75–1071.25) | Pdom = 0.745 | 0.06 (0.05–0.08) | Pdom = 0.877 | 557.5 (415.25–878.75) | Pdom = 0.745 | 85 (63.75–117.5) | Pdom = 0.768 | |

| BCHE rs1803274 | CC | 758.5 (567.75–1075.75) | 0.487 | 0.06 (0.05–0.08) | 0.271 | 552.5 (403–840) | 0.306 | 81 (60.75–111) | 0.136 |

| CT | 678.5 (566.5–893.5) | 0.06 (0.04–0.07) | 612.5 (440.25–1052.75) | 97.5 (67.75–140) | |||||

| CT + TT | 688 (563–851.5) | Pdom = 0.317 | 0.06 (0.04–0.07) | Pdom = 0.275 | 617 (437.5–1035) | Pdom = 0.201 | 96 (69–135.5) | Pdom = 0.062 | |

| BCHE rs1799807 | TT | 743 (570–1005) | 1 | 0.06 (0.04–0.08) | 0.471 | 567 (420–878) | 0.929 | 86 (65–116) | 0.897 |

| TC | 697 (661.25–958) | 0.07 (0.06–0.08) | 564.5 (329.5–1082) | 89 (49.5–135.25) | |||||

| TC + CC | 697 (661.25–958) | Pdom = 1 | 0.07 (0.06–0.08) | Pdom = 0.471 | 564.5 (329.5–1082) | Pdom = 0.929 | 89 (49.5–135.25) | Pdom = 0.897 | |

| TOMM40 rs2075650 | AA | 765 (591.75–1155.75) | 0.178 | 0.06 (0.04–0.09) | 0.170 | 552.5 (403–874.5) | 0.319 | 81 (58.5–110) | 0.203 |

| AG | 698 (579.5–878) | 0.06 (0.05–0.07) | 592.5 (459.75–859.25) | 93.5 (69.5–120.25) | |||||

| GG | 613 (513–877) | 0.05 (0.03–0.06) | 821 (385–1183) | 114 (59–151) | |||||

| AG + GG | 697 (558.5–871.5) | Pdom = 0.095 | 0.06 (0.05–0.07) | Pdom = 0.219 | 613 (458.5–940) | Pdom = 0.219 | 95 (69–124) | Pdom = 0.099 | |

| TOMM40 rs157581 | TT | 799.5 (593.25–1234.25) | 0.095 | 0.06 (0.04–0.11) | 0.239 | 543 (319–777.25) | 0.099 | 81 (56.75–109) | 0.106 |

| TC | 720 (565.5–885.5) | 0.06 (0.05–0.07) | 613 (470–886) | 95 (74–118) | |||||

| CC | 682.5 (520.75–815.5) | 0.06 (0.04–0.09) | 768 (374.75–1070.25) | 97.5 (57.5–131.75) | |||||

| TC + CC | 711 (561–877) | Pdom = 0.033 | 0.06 (0.05–0.07) | Pdom = 0.091 | 617 (468–911) | Pdom = 0.032 | 95 (73–123) | Pdom = 0.034 | |

| ACE rs1800764 | CC | 658 (542.5–899.5) | 0.341 | 0.06 (0.04–0.07) | 0.432 | 617 (459.5–888) | 0.641 | 97 (73.5–124) | 0.469 |

| CT | 759 (613.5–948.5) | 0.06 (0.05–0.08) | 549 (448.5–879) | 84 (66.5–115) | |||||

| TT | 743 (575–1291) | 0.06 (0.04–0.11) | 567 (403–881) | 81 (58–114) | |||||

| CT + TT | 747.5 (596.75–1071.75) | Pdom = 0.153 | 0.06 (0.05–0.08) | Pdom = 0.204 | 554 (412.5–876.75) | Pdom = 0.416 | 82 (63.25–114) | Pdom = 0.256 | |

| ACE rs4343 | GG | 712 (558.5–892.75) | 0.592 | 0.06 (0.05–0.07) | 0.979 | 594.5 (343.75–859.25) | 0.594 | 95 (59.75–123.25) | 0.732 |

| GA | 751 (613.75–926) | 0.06 (0.05–0.08) | 560 (467.75–894.5) | 86.5 (67.75–115.25) | |||||

| AA | 747 (545–1326.5) | 0.06 (0.04–0.11) | 515 (392.5–913) | 81 (57.5–122.5) | |||||

| GA + AA | 747 (585–1071) | Pdom = 0.353 | 0.06 (0.05–0.08) | Pdom = 0.845 | 549 (427–896) | Pdom = 0.819 | 83 (65–116) | Pdom = 0.642 | |

| IL6 R rs2228145 | AA | 718.5 (540–938.5) | 0.204 | 0.06 (0.04–0.08) | 0.984 | 557.5 (428.25–910.75) | 0.771 | 85.5 (68–122) | 0.796 |

| AC | 760 (602–1072) | 0.06 (0.05–0.08) | 571 (410–855) | 87 (65–111) | |||||

| CC | 636 (529–977.5) | 0.06 (0.04–0.10) | 688.5 (297.75–1075) | 82 (40.75–134.5) | |||||

| AC + CC | 747 (592.5–1071.5) | Pdom = 0.343 | 0.06 (0.05–0.08) | Pdom = 0.856 | 571 (407–875) | Pdom = 0.757 | 87 (63.5–114.5) | Pdom = 0.518 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vogrinc, D.; Gregorič Kramberger, M.; Emeršič, A.; Čučnik, S.; Goričar, K.; Dolžan, V. The Association of Selected GWAS Reported AD Risk Loci with CSF Biomarker Levels and Cognitive Decline in Slovenian Patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12966. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241612966

Vogrinc D, Gregorič Kramberger M, Emeršič A, Čučnik S, Goričar K, Dolžan V. The Association of Selected GWAS Reported AD Risk Loci with CSF Biomarker Levels and Cognitive Decline in Slovenian Patients. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023; 24(16):12966. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241612966

Chicago/Turabian StyleVogrinc, David, Milica Gregorič Kramberger, Andreja Emeršič, Saša Čučnik, Katja Goričar, and Vita Dolžan. 2023. "The Association of Selected GWAS Reported AD Risk Loci with CSF Biomarker Levels and Cognitive Decline in Slovenian Patients" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 24, no. 16: 12966. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241612966

APA StyleVogrinc, D., Gregorič Kramberger, M., Emeršič, A., Čučnik, S., Goričar, K., & Dolžan, V. (2023). The Association of Selected GWAS Reported AD Risk Loci with CSF Biomarker Levels and Cognitive Decline in Slovenian Patients. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(16), 12966. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241612966