Classic Galactosemia: Clinical and Computational Characterization of a Novel GALT Missense Variant (p.A303D) and a Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Screening Procedures and Clinical History

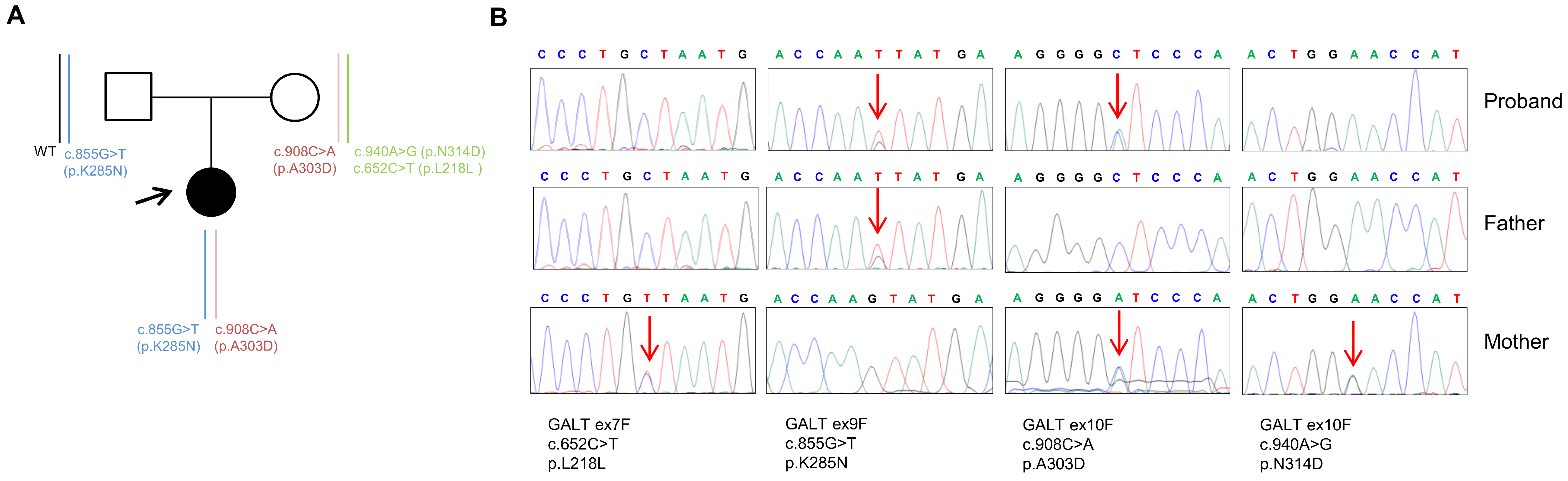

2.2. Genetic Analysis

2.3. In Silico Analysis of the Structural Impact of the GALT A303D Missense Variant

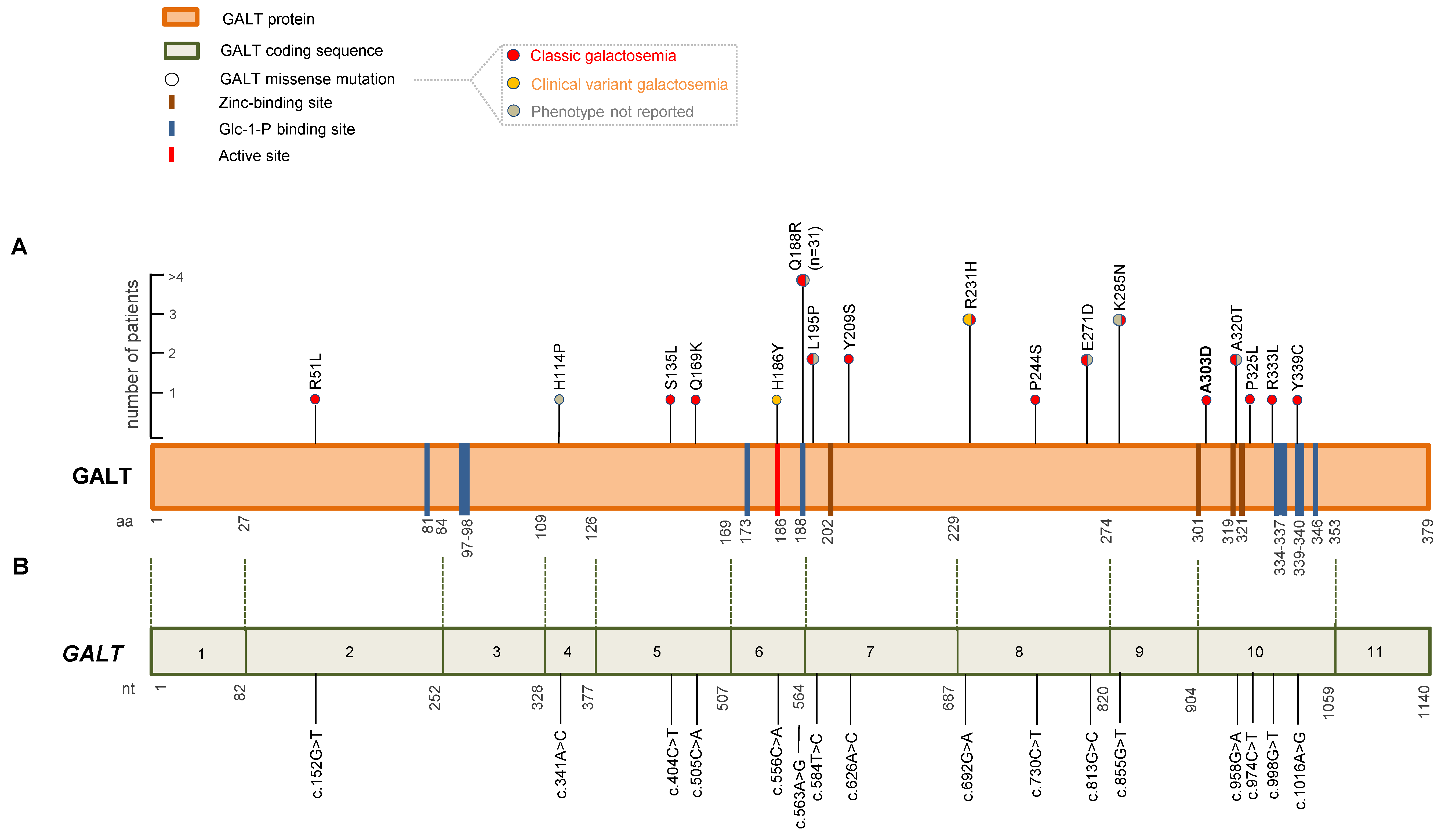

2.4. Literature Review

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Screening Procedures

4.2. Genetic Analysis

4.3. In Silico Prediction Analysis

4.4. Literature Review

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Demirbas, D.; Coelho, A.I.; Rubio-Gozalbo, M.E.; Berry, G.T. Hereditary Galactosemia. Metabolism 2018, 83, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viggiano, E.; Marabotti, A.; Politano, L.; Burlina, A. Galactose-1-Phosphate Uridyltransferase Deficiency: A Literature Review of the Putative Mechanisms of Short and Long-Term Complications and Allelic Variants. Clin. Genet. 2018, 93, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, G.T. Classic Galactosemia and Clinical Variant Galactosemia. In GeneReviews®; Adam, M.P., Mirzaa, G.M., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Bean, L.J., Gripp, K.W., Amemiya, A., Eds.; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch, A.M.; Grootenhuis, M.A.; Bakker, H.D.; Heijmans, H.S.A.; Wijburg, F.A.; Last, B.F. Living with Classical Galactosemia: Health-Related Quality of Life Consequences. Pediatrics 2004, 113, e423–e428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosch, A.M.; Maurice-Stam, H.; Wijburg, F.A.; Grootenhuis, M.A. Remarkable Differences: The Course of Life of Young Adults with Galactosaemia and PKU. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2009, 32, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, N.D.; Immerman, E.B.; Flach, J.E.; Florez, M.; Fridovich-Keil, J.L.; Elsas, L.J. The Human Galactose-1-Phosphate Uridyltransferase Gene. Genomics 1992, 14, 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çelik, M.; Akdeniz, O.; Ozbek, M.N.; Kirbiyik, O. Neonatal Classic Galactosemia-Diagnosis, Clinical Profile and Molecular Characteristics in Unscreened Turkish Population. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2022, 68, fmac098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stenson, P.D.; Mort, M.; Ball, E.V.; Evans, K.; Hayden, M.; Heywood, S.; Hussain, M.; Phillips, A.D.; Cooper, D.N. The Human Gene Mutation Database: Towards a Comprehensive Repository of Inherited Mutation Data for Medical Research, Genetic Diagnosis and next-Generation Sequencing Studies. Hum. Genet. 2017, 136, 665–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, A.I.; Trabuco, M.; Ramos, R.; Silva, M.J.; Tavares de Almeida, I.; Leandro, P.; Rivera, I.; Vicente, J.B. Functional and Structural Impact of the Most Prevalent Missense Mutations in Classic Galactosemia. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 2014, 2, 484–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Succoio, M.; Sacchettini, R.; Rossi, A.; Parenti, G.; Ruoppolo, M. Galactosemia: Biochemistry, Molecular Genetics, Newborn Screening, and Treatment. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karas, N.; Gobec, L.; Pfeifer, V.; Mlinar, B.; Battelino, T.; Lukac-Bajalo, J. Mutations in Galactose-1-Phosphate Uridyltransferase Gene in Patients with Idiopathic Presenile Cataract. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2003, 26, 699–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.S.; Podskarbi, T. Molecular and Biochemical Basis for Variants and Deficiency of GALT: Report of 4 Novel Mutations. Bratisl. Lek. Listy 2004, 105, 315–317. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Karczewski, K.J.; Francioli, L.C.; Tiao, G.; Cummings, B.B.; Alföldi, J.; Wang, Q.; Collins, R.L.; Laricchia, K.M.; Ganna, A.; Birnbaum, D.P.; et al. The Mutational Constraint Spectrum Quantified from Variation in 141,456 Humans. Nature 2020, 581, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 1000 Genomes Project Consortium; Auton, A.; Brooks, L.D.; Durbin, R.M.; Garrison, E.P.; Kang, H.M.; Korbel, J.O.; Marchini, J.L.; McCarthy, S.; McVean, G.A.; et al. A Global Reference for Human Genetic Variation. Nature 2015, 526, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auer, P.L.; Reiner, A.P.; Wang, G.; Kang, H.M.; Abecasis, G.R.; Altshuler, D.; Bamshad, M.J.; Nickerson, D.A.; Tracy, R.P.; Rich, S.S.; et al. Guidelines for Large-Scale Sequence-Based Complex Trait Association Studies: Lessons Learned from the NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2016, 99, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozák, L.; Francová, H.; Fajkusová, L.; Pijácková, A.; Macku, J.; Stastná, S.; Peskovová, K.; Martincová, O.; Krijt, J.; Bzdúch, V. Mutation Analysis of the GALT Gene in Czech and Slovak Galactosemia Populations: Identification of Six Novel Mutations, Including a Stop Codon Mutation (X380R). Hum. Mutat. 2000, 15, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrum, M.J.; Lee, J.M.; Riley, G.R.; Jang, W.; Rubinstein, W.S.; Church, D.M.; Maglott, D.R. ClinVar: Public Archive of Relationships among Sequence Variation and Human Phenotype. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, D980–D985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chunn, L.M.; Nefcy, D.C.; Scouten, R.W.; Tarpey, R.P.; Chauhan, G.; Lim, M.S.; Elenitoba-Johnson, K.S.J.; Schwartz, S.A.; Kiel, M.J. Mastermind: A Comprehensive Genomic Association Search Engine for Empirical Evidence Curation and Genetic Variant Interpretation. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 577152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and Guidelines for the Interpretation of Sequence Variants: A Joint Consensus Recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ittisoponpisan, S.; Islam, S.A.; Khanna, T.; Alhuzimi, E.; David, A.; Sternberg, M.J.E. Can Predicted Protein 3D Structures Provide Reliable Insights into Whether Missense Variants Are Disease Associated? J. Mol. Biol. 2019, 431, 2197–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.; Sims, G.E.; Murphy, S.; Miller, J.R.; Chan, A.P. Predicting the Functional Effect of Amino Acid Substitutions and Indels. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e46688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, D.E.V.; Ascher, D.B.; Blundell, T.L. mCSM: Predicting the Effects of Mutations in Proteins Using Graph-Based Signatures. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worth, C.L.; Preissner, R.; Blundell, T.L. SDM—A Server for Predicting Effects of Mutations on Protein Stability and Malfunction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, W215–W222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, D.E.V.; Ascher, D.B.; Blundell, T.L. DUET: A Server for Predicting Effects of Mutations on Protein Stability Using an Integrated Computational Approach. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, W314–W319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Ferrando, V.; Gazzo, A.; de la Cruz, X.; Orozco, M.; Gelpí, J.L. PMut: A Web-Based Tool for the Annotation of Pathological Variants on Proteins, 2017 Update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, W222–W228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCorvie, T.J.; Gleason, T.J.; Fridovich-Keil, J.L.; Timson, D.J. Misfolding of Galactose 1-Phosphate Uridylyltransferase Can Result in Type I Galactosemia. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1832, 1279–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Acierno, A.; Scafuri, B.; Facchiano, A.; Marabotti, A. The Evolution of a Web Resource: The Galactosemia Proteins Database 2.0. Hum. Mutat. 2018, 39, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delnoy, B.; Coelho, A.I.; Rubio-Gozalbo, M.E. Current and Future Treatments for Classic Galactosemia. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCorvie, T.J.; Kopec, J.; Pey, A.L.; Fitzpatrick, F.; Patel, D.; Chalk, R.; Shrestha, L.; Yue, W.W. Molecular Basis of Classic Galactosemia from the Structure of Human Galactose 1-Phosphate Uridylyltransferase. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2016, 25, 2234–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, A.E.; Sanders, R.D.; Garza, K.R.; McGaha, L.A.; Bean, L.J.H.; Coffee, B.W.; Thomas, J.W.; Cutler, D.J.; Kurtkaya, N.L.; Fridovich-Keil, J.L. Origins, Distribution and Expression of the Duarte-2 (D2) Allele of Galactose-1-Phosphate Uridylyltransferase. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009, 18, 1624–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.W. Regulation of Zinc-Dependent Enzymes by Metal Carrier Proteins. Biometals 2022, 35, 187–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ataie, N.J.; Hoang, Q.Q.; Zahniser, M.P.D.; Tu, Y.; Milne, A.; Petsko, G.A.; Ringe, D. Zinc Coordination Geometry and Ligand Binding Affinity: The Structural and Kinetic Analysis of the Second-Shell Serine 228 Residue and the Methionine 180 Residue of the Aminopeptidase from Vibrio Proteolyticus. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 7673–7683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Facchiano, A.; Marabotti, A. Analysis of Galactosemia-Linked Mutations of GALT Enzyme Using a Computational Biology Approach. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2010, 23, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Boutron, A.; Marabotti, A.; Facchiano, A.; Cheillan, D.; Zater, M.; Oliveira, C.; Costa, C.; Labrune, P.; Brivet, M.; French Galactosemia Working Group. Mutation Spectrum in the French Cohort of Galactosemic Patients and Structural Simulation of 27 Novel Missense Variations. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2012, 107, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, D.F.; Camelo, J.S.; Molfetta, G.A.; Turcato, M.; Souza, C.F.M.; Porta, G.; Steiner, C.E.; Silva, W.A. Clinical Profile and Molecular Characterization of Galactosemia in Brazil: Identification of Seven Novel Mutations. BMC Med. Genet. 2016, 17, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viggiano, E.; Marabotti, A.; Burlina, A.P.; Cazzorla, C.; D’Apice, M.R.; Giordano, L.; Fasan, I.; Novelli, G.; Facchiano, A.; Burlina, A.B. Clinical and Molecular Spectra in Galactosemic Patients from Neonatal Screening in Northeastern Italy: Structural and Functional Characterization of New Variations in the Galactose-1-Phosphate Uridyltransferase (GALT) Gene. Gene 2015, 559, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadža, D.P.; Sarnavka, V.; Vuković, J.; Fumić, K.; Krželj, V.; Lozić, B.; Pušeljić, S.; Pereira, H.; Silva, M.J.; Tavares de Almeida, I.; et al. Molecular Basis and Clinical Presentation of Classic Galactosemia in a Croatian Population. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 31, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riehman, K.; Crews, C.; Fridovich-Keil, J.L. Relationship between Genotype, Activity, and Galactose Sensitivity in Yeast Expressing Patient Alleles of Human Galactose-1-Phosphate Uridylyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 10634–10640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsas, L.J.; Langley, S.; Steele, E.; Evinger, J.; Fridovich-Keil, J.L.; Brown, A.; Singh, R.; Fernhoff, P.; Hjelm, L.N.; Dembure, P.P. Galactosemia: A Strategy to Identify New Biochemical Phenotypes and Molecular Genotypes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1995, 56, 630–639. [Google Scholar]

- Kozák, L.; Francová, H.; Pijácková, A.; Macku, J.; Stastná, S.; Peskovová, K.; Martincová, O.; Krijt, J. Presence of a Deletion in the 5′ Upstream Region of the GALT Gene in Duarte (D2) Alleles. J. Med. Genet. 1999, 36, 576–578. [Google Scholar]

- Smigielski, E.M.; Sirotkin, K.; Ward, M.; Sherry, S.T. dbSNP: A Database of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 352–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milánkovics, I.; Schuler, Á.; Kámory, E.; Csókay, B.; Fodor, F.; Somogyi, C.; Németh, K.; Fekete, G. Molecular and clinical analysis of patients with classic and Duarte galactosemia in western Hungary. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2010, 122, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welsink-Karssies, M.M.; van Weeghel, M.; Hollak, C.E.; Elfrink, H.L.; Janssen, M.C.; Lai, K.; Langendonk, J.G.; Oussoren, E.; Ruiter, J.P.; Treacy, E.P.; et al. The Galactose Index measured in fibroblasts of GALT deficient patients distinguishes variant patients detected by newborn screening from patients with classical phenotypes. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2020, 129, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucas-Del-Pozo, S.; Moreno-Martinez, D.; Camprodon-Gomez, M.; Moreno-Martinez, D.; Hernández-Vara, J. Galactosemia Diagnosis by Whole Exome Sequencing Later in Life. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 2021, 8 (Suppl. S1), S37–S39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuzyuk, T.; Viau, K.; Andrews, A.; Pasquali, M.; Longo, N. Biochemical changes and clinical outcomes in 34 patients with classic galactosemia. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2018, 41, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulpis, K.H.; Thodi, G.; Iakovou, K.; Chatzidaki, M.; Dotsikas, Y.; Molou, E.; Triantafylli, O.; Loukas, Y.L. Mutational analysis of GALT gene in Greek patients with galactosaemia: Identification of two novel mutations and clinical evaluation. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Investig. 2017, 77, 423–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gubbels, C.S.; Welt, C.K.; Dumoulin, J.C.; Robben, S.G.; Gordon, C.M.; Dunselman, G.A.; Rubio-Gozalbo, M.E.; Berry, G.T. The male reproductive system in classic galactosemia: Cryptorchidism and low semen volume. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2013, 36, 779–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gubbels, C.S.; Land, J.A.; Evers, J.L.; Bierau, J.; Menheere, P.P.; Robben, S.G.; Rubio-Gozalbo, M.E. Primary ovarian insufficiency in classic galactosemia: Role of FSH dysfunction and timing of the lesion. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2013, 36, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waisbren, S.E.; Potter, N.L.; Gordon, C.M.; Green, R.C.; Greenstein, P.; Gubbels, C.S.; Rubio-Gozalbo, E.; Schomer, D.; Welt, C.; Anastasoaie, V.; et al. The adult galactosemic phenotype. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2012, 35, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asteggiano, C.G.; Papazoglu, M.; Bistué Millón, M.B.; Peralta, M.F.; Azar, N.B.; Spécola, N.S.; Guelbert, N.; Suldrup, N.S.; Pereyra, M.; Dodelson de Kremer, R. Ten years of screening for congenital disorders of glycosylation in Argentina: Case studies and pitfalls. Pediatr. Res. 2018, 84, 837–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zekanowski, C.; Radomyska, B.; Bal, J. Molecular characterization of Polish patients with classical galactosaemia. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 1999, 22, 679–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Forte, G.; Buonadonna, A.L.; Pantaleo, A.; Fasano, C.; Capodiferro, D.; Grossi, V.; Sanese, P.; Cariola, F.; De Marco, K.; Lepore Signorile, M.; et al. Classic Galactosemia: Clinical and Computational Characterization of a Novel GALT Missense Variant (p.A303D) and a Literature Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17388. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms242417388

Forte G, Buonadonna AL, Pantaleo A, Fasano C, Capodiferro D, Grossi V, Sanese P, Cariola F, De Marco K, Lepore Signorile M, et al. Classic Galactosemia: Clinical and Computational Characterization of a Novel GALT Missense Variant (p.A303D) and a Literature Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023; 24(24):17388. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms242417388

Chicago/Turabian StyleForte, Giovanna, Antonia Lucia Buonadonna, Antonino Pantaleo, Candida Fasano, Donatella Capodiferro, Valentina Grossi, Paola Sanese, Filomena Cariola, Katia De Marco, Martina Lepore Signorile, and et al. 2023. "Classic Galactosemia: Clinical and Computational Characterization of a Novel GALT Missense Variant (p.A303D) and a Literature Review" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 24, no. 24: 17388. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms242417388

APA StyleForte, G., Buonadonna, A. L., Pantaleo, A., Fasano, C., Capodiferro, D., Grossi, V., Sanese, P., Cariola, F., De Marco, K., Lepore Signorile, M., Manghisi, A., Guglielmi, A. F., Simonetti, S., Laforgia, N., Disciglio, V., & Simone, C. (2023). Classic Galactosemia: Clinical and Computational Characterization of a Novel GALT Missense Variant (p.A303D) and a Literature Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(24), 17388. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms242417388