Mitochondrial DNA Supplementation of Oocytes Has Downstream Effects on the Transcriptional Profiles of Sus scrofa Adult Tissues with High mtDNA Copy Number

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Transcriptome Data from mtDNA-Supplemented Adult Pig Tissues with High mtDNA Copy Number

2.2. mtDNA Supplementation Affects mtDNA-Encoded Transcript Levels in Adult Tissues with High mtDNA Copy Number

2.3. mtDNA Supplementation Influences Glyoxylate Metabolism and Interferon Signalling Pathways

2.4. The Effect of the Source of mtDNA for Supplementation on Gene Expression

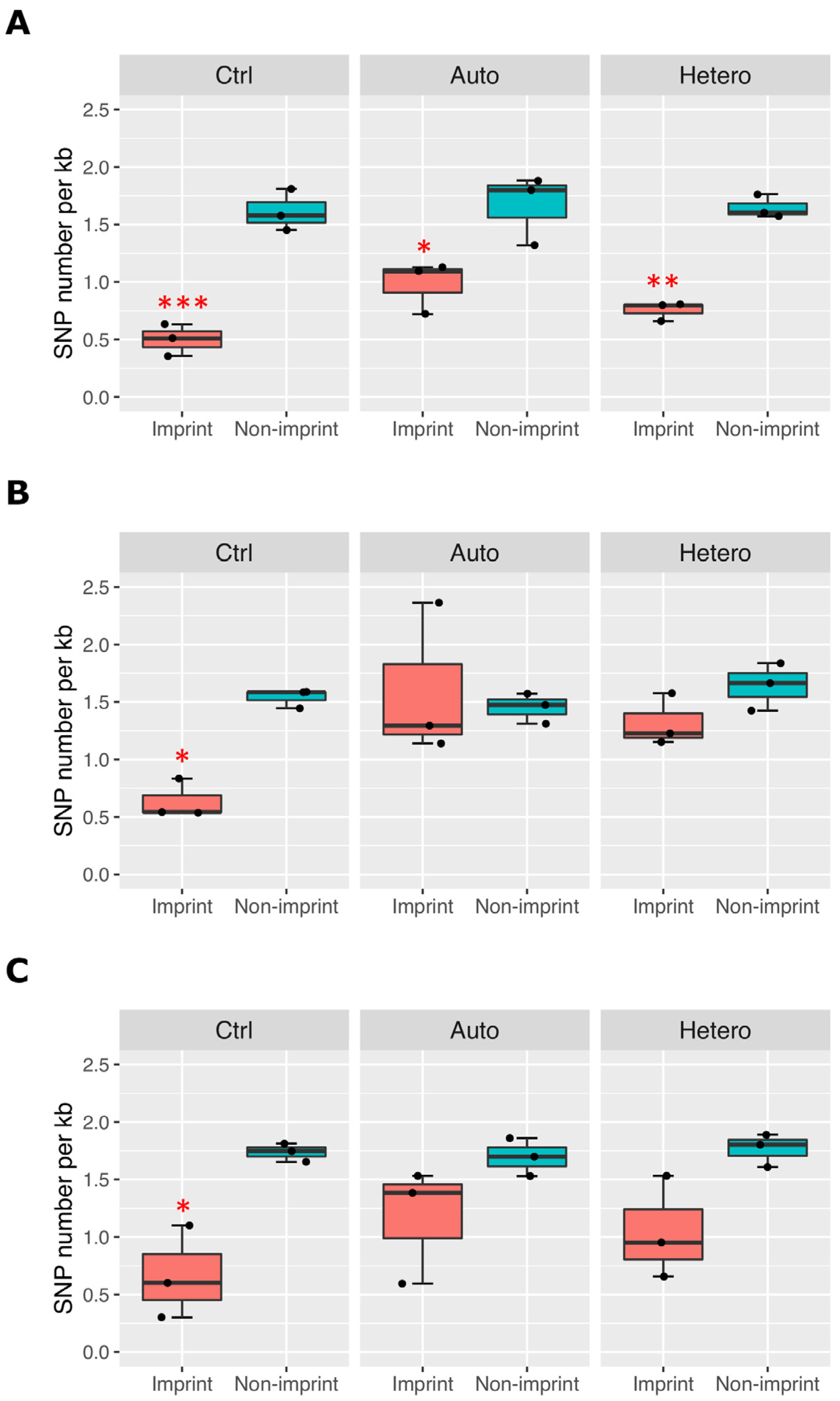

2.5. Imprinted Genes Are Differentially Expressed in mtDNA-Supplemented-Derived Pig Heart and Liver

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Tissue Collection from the Pigs

4.2. RNA Extraction from Heart, Liver and Brain, RNAseq Library Construction and NGS

4.3. RNAseq Data Analysis and Differentially Expressed Gene (DEG) Identification

4.4. Functional Pathway Enrichment and Gene Network Analysis

4.5. Bi-Allelic Expression Analysis of Genes in Imprinting Loci

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hatefi, Y. The mitochondrial electron transport and oxidative phosphorylation system. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1985, 54, 1015–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, S.; Bankier, A.T.; Barrell, B.G.; de Bruijn, M.H.; Coulson, A.R.; Drouin, J.; Eperon, I.C.; Nierlich, D.P.; Roe, B.A.; Sanger, F.; et al. Sequence and organization of the human mitochondrial genome. Nature 1981, 290, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ursing, B.M.; Arnason, U. The complete mitochondrial DNA sequence of the pig (Sus scrofa). J. Mol. Evol. 1998, 47, 302–306. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Calvo, S.E.; Mootha, V.K. The mitochondrial proteome and human disease. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 2010, 11, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorman, G.S.; Schaefer, A.M.; Ng, Y.; Gomez, N.; Blakely, E.L.; Alston, C.L.; Feeney, C.; Horvath, R.; Yu-Wai-Man, P.; Chinnery, P.F.; et al. Prevalence of nuclear and mitochondrial DNA mutations related to adult mitochondrial disease. Ann. Neurol. 2015, 77, 753–759. [Google Scholar]

- Schapira, A.H. Mitochondrial disease. Lancet 2006, 368, 70–82. [Google Scholar]

- Matilainen, O.; Quiros, P.M.; Auwerx, J. Mitochondria and Epigenetics—Crosstalk in Homeostasis and Stress. Trends Cell Biol. 2017, 27, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poyton, R.O.; McEwen, J.E. Crosstalk between nuclear and mitochondrial genomes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1996, 65, 563–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St John, J.C. Genomic Balance: Two Genomes Establishing Synchrony to Modulate Cellular Fate and Function. Cells 2019, 8, 1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagnone, G.; Tsai, T.S.; Srirattana, K.; Rossello, F.; Powell, D.R.; Rohrer, G.; Cree, L.; Trounce, I.A.; St John, J.C. Segregation of Naturally Occurring Mitochondrial DNA Variants in a Mini-Pig Model. Genetics 2016, 202, 931–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, R.D.; Mahmud, A.; McKenzie, M.; Trounce, I.A.; St John, J.C. Mitochondrial DNA copy number is regulated in a tissue specific manner by DNA methylation of the nuclear-encoded DNA polymerase gamma A. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 10124–10138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- St John, J.C.; Facucho-Oliveira, J.; Jiang, Y.; Kelly, R.; Salah, R. Mitochondrial DNA transmission, replication and inheritance: A journey from the gamete through the embryo and into offspring and embryonic stem cells. Hum. Reprod. Update 2010, 16, 488–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hance, N.; Ekstrand, M.I.; Trifunovic, A. Mitochondrial DNA polymerase gamma is essential for mammalian embryogenesis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005, 14, 1775–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson, N.G.; Wang, J.; Wilhelmsson, H.; Oldfors, A.; Rustin, P.; Lewandoski, M.; Barsh, G.S.; Clayton, D.A. Mitochondrial transcription factor A is necessary for mtDNA maintenance and embryogenesis in mice. Nat. Genet. 1998, 18, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Shourbagy, S.H.; Spikings, E.C.; Freitas, M.; St John, J.C. Mitochondria directly influence fertilisation outcome in the pig. Reproduction 2006, 131, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stigliani, S.; Persico, L.; Lagazio, C.; Anserini, P.; Venturini, P.L.; Scaruffi, P. Mitochondrial DNA in Day 3 embryo culture medium is a novel, non-invasive biomarker of blastocyst potential and implantation outcome. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2014, 20, 1238–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May-Panloup, P.; Chretien, M.F.; Jacques, C.; Vasseur, C.; Malthiery, Y.; Reynier, P. Low oocyte mitochondrial DNA content in ovarian insufficiency. Hum. Reprod. 2005, 20, 593–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynier, P.; May-Panloup, P.; Chretien, M.F.; Morgan, C.J.; Jean, M.; Savagner, F.; Barriere, P.; Malthiery, Y. Mitochondrial DNA content affects the fertilizability of human oocytes. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2001, 7, 425–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, T.A.; El Shourbagy, S.; St John, J.C. Mitochondrial content reflects oocyte variability and fertilization outcome. Fertil. Steril. 2006, 85, 584–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagnone, G.L.; Tsai, T.S.; Makanji, Y.; Matthews, P.; Gould, J.; Bonkowski, M.S.; Elgass, K.D.; Wong, A.S.; Wu, L.E.; McKenzie, M.; et al. Restoration of normal embryogenesis by mitochondrial supplementation in pig oocytes exhibiting mitochondrial DNA deficiency. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 23229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobarak, H.; Heidarpour, M.; Tsai, P.J.; Rezabakhsh, A.; Rahbarghazi, R.; Nouri, M.; Mahdipour, M. Autologous mitochondrial microinjection; a strategy to improve the oocyte quality and subsequent reproductive outcome during aging. Cell Biosci. 2019, 9, 95. [Google Scholar]

- St John, J.C.; Okada, T.; Andreas, E.; Penn, A. The role of mtDNA in oocyte quality and embryo development. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakih, M.; El Shmoury, M.; Szeptycki, J.; dela Cruz, D.B.; Lux, C.; Verjee, S.; Burgess, C.M.; Cohn, G.M.; Casper, R.F. The AUGMENT treatment: Physician reported outcomes of the initial global patient experience. JFIV Reprod. Med. Genet. 2015, 3, 154. [Google Scholar]

- Labarta, E.; de Los Santos, M.J.; Escriba, M.J.; Pellicer, A.; Herraiz, S. Mitochondria as a tool for oocyte rejuvenation. Fertil. Steril. 2019, 111, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.T.; Bonneau, A.R.; Giraldez, A.J. Zygotic genome activation during the maternal-to-zygotic transition. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2014, 30, 581–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oestrup, O.; Hall, V.; Petkov, S.G.; Wolf, X.A.; Hyldig, S.; Hyttel, P. From zygote to implantation: Morphological and molecular dynamics during embryo development in the pig. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2009, 44 (Suppl. 3), 39–49. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, T.S.; Tyagi, S.; St John, J.C. The molecular characterisation of mitochondrial DNA deficient oocytes using a pig model. Hum. Reprod. 2018, 33, 942–953. [Google Scholar]

- Okada, T.; McIlfatrick, S.; Hin, N.; Aryamanesh, N.; Breen, J.; St John, J.C. Mitochondrial supplementation of Sus scrofa metaphase II oocytes alters DNA methylation and gene expression profiles of blastocysts. Epigenetics Chromatin 2022, 15, 12. [Google Scholar]

- McIlfatrick, S.; O’Leary, S.; Okada, T.; Penn, A.; Nguyen, V.H.T.; McKenny, L.; Huang, S.-Y.; Andreas, E.; Finnie, J.; Kirkwood, R.; et al. Does supplementation of oocytes with additional mitochondrial DNA influence developmental outcome? iScience 2023, 26, 105956. [Google Scholar]

- Choux, C.; Binquet, C.; Carmignac, V.; Bruno, C.; Chapusot, C.; Barberet, J.; Lamotte, M.; Sagot, P.; Bourc’his, D.; Fauque, P. The epigenetic control of transposable elements and imprinted genes in newborns is affected by the mode of conception: ART versus spontaneous conception without underlying infertility. Hum. Reprod. 2018, 33, 331–340. [Google Scholar]

- Doherty, A.S.; Mann, M.R.; Tremblay, K.D.; Bartolomei, M.S.; Schultz, R.M. Differential effects of culture on imprinted H19 expression in the preimplantation mouse embryo. Biol. Reprod. 2000, 62, 1526–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, D.K.; Lane, M. Ex vivo early embryo development and effects on gene expression and imprinting. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2005, 17, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katari, S.; Turan, N.; Bibikova, M.; Erinle, O.; Chalian, R.; Foster, M.; Gaughan, J.P.; Coutifaris, C.; Sapienza, C. DNA methylation and gene expression differences in children conceived in vitro or in vivo. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009, 18, 3769–3778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gene Ontology, C. The Gene Ontology resource: Enriching a GOld mine. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D325–D334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, T.; McIlfatrick, S.; St John, J.C. Mitochondrial DNA deficiency and supplementation in Sus scrofa oocytes influence transcriptome profiles in oocytes and blastocysts. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, A.J.; Williams, B.R. Interferon-inducible antiviral effectors. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 8, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, J.S.; Tait, S.W. Mitochondrial DNA in inflammation and immunity. EMBO Rep. 2020, 21, e49799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, A.P.; Shadel, G.S. Mitochondrial DNA in innate immune responses and inflammatory pathology. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 17, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimada, K.; Crother, T.R.; Karlin, J.; Dagvadorj, J.; Chiba, N.; Chen, S.; Ramanujan, V.K.; Wolf, A.J.; Vergnes, L.; Ojcius, D.M.; et al. Oxidized mitochondrial DNA activates the NLRP3 inflammasome during apoptosis. Immunity 2012, 36, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lepelley, A.; Wai, T.; Crow, Y.J. Mitochondrial Nucleic Acid as a Driver of Pathogenic Type I Interferon Induction in Mendelian Disease. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 729763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, A.P.; Shadel, G.S.; Ghosh, S. Mitochondria in innate immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salido, E.; Pey, A.L.; Rodriguez, R.; Lorenzo, V. Primary hyperoxalurias: Disorders of glyoxylate detoxification. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1822, 1453–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Wu, Z.; Dai, Z.; Yang, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, G. Glycine metabolism in animals and humans: Implications for nutrition and health. Amino Acids 2013, 45, 463–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.Y.; Kim, E.H. Therapeutic Effects of Amino Acids in Liver Diseases: Current Studies and Future Perspectives. J. Cancer Prev. 2019, 24, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.L.; You, H.B.; Li, X.H.; Chen, X.F.; Liu, Z.J.; Gong, J.P. Glycine attenuates endotoxin-induced liver injury by downregulating TLR4 signaling in Kupffer cells. Am. J. Surg. 2008, 196, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinnery, P.F.; Andrews, R.M.; Turnbull, D.M.; Howell, N.N. Leber hereditary optic neuropathy: Does heteroplasmy influence the inheritance and expression of the G11778A mitochondrial DNA mutation? Am. J. Med. Genet. 2001, 98, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elson, J.L.; Samuels, D.C.; Turnbull, D.M.; Chinnery, P.F. Random intracellular drift explains the clonal expansion of mitochondrial DNA mutations with age. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001, 68, 802–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J.B.; Chinnery, P.F. The dynamics of mitochondrial DNA heteroplasmy: Implications for human health and disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2015, 16, 530–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Reyes, I.; Chandel, N.S. Mitochondrial TCA cycle metabolites control physiology and disease. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latorre-Pellicer, A.; Moreno-Loshuertos, R.; Lechuga-Vieco, A.V.; Sanchez-Cabo, F.; Torroja, C.; Acin-Perez, R.; Calvo, E.; Aix, E.; Gonzalez-Guerra, A.; Logan, A.; et al. Mitochondrial and nuclear DNA matching shapes metabolism and healthy ageing. Nature 2016, 535, 561–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.T.; Sun, X.; Tsai, T.S.; Johnson, J.L.; Gould, J.A.; Garama, D.J.; Gough, D.J.; McKenzie, M.; Trounce, I.A.; St John, J.C. Mitochondrial DNA haplotypes induce differential patterns of DNA methylation that result in differential chromosomal gene expression patterns. Cell Death Discov. 2017, 3, 17062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- St John, J.C.; Makanji, Y.; Johnson, J.L.; Tsai, T.S.; Lagondar, S.; Rodda, F.; Sun, X.; Pangestu, M.; Chen, P.; Temple-Smith, P. The transgenerational effects of oocyte mitochondrial supplementation. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, H.; Ferguson-Smith, A.C.; Shum, A.S.; Barton, S.C.; Surani, M.A. Temporal and spatial regulation of H19 imprinting in normal and uniparental mouse embryos. Development 1995, 121, 4195–4202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, S. FastQC. Available online: https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ (accessed on 4 November 2021).

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ensembl Index of /pub/release-98/fasta/sus_scrofa/dna/. Available online: http://ftp.ensembl.org/pub/release-98/fasta/sus_scrofa/dna/ (accessed on 4 November 2021).

- Dobin, A.; Davis, C.A.; Schlesinger, F.; Drenkow, J.; Zaleski, C.; Jha, S.; Batut, P.; Chaisson, M.; Gingeras, T.R. STAR: Ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Smyth, G.K.; Shi, W. featureCounts: An efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewels, P.; Magnusson, M.; Lundin, S.; Kaller, M. MultiQC: Summarize analysis results for multiple tools and samples in a single report. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 3047–3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kolde, R. pheatmap: Pretty Heatmaps. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/pheatmap/index.html (accessed on 4 November 2021).

- Subramanian, A.; Tamayo, P.; Mootha, V.K.; Mukherjee, S.; Ebert, B.L.; Gillette, M.A.; Paulovich, A.; Pomeroy, S.L.; Golub, T.R.; Lander, E.S.; et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 15545–15550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menges, M.; Hennig, L.; Gruissem, W.; Murray, J.A. Genome-wide gene expression in an Arabidopsis cell suspension. Plant Mol. Biol. 2003, 53, 423–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimand, J.; Isserlin, R.; Voisin, V.; Kucera, M.; Tannus-Lopes, C.; Rostamianfar, A.; Wadi, L.; Meyer, M.; Wong, J.; Xu, C.; et al. Pathway enrichment analysis and visualization of omics data using g:Profiler, GSEA, Cytoscape and EnrichmentMap. Nat. Protoc. 2019, 14, 482–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, J. How to Get All the Orthologous Genes between Two Species. Available online: https://www.ensembl.info/2009/01/21/how-to-get-all-the-orthologous-genes-between-two-species/ (accessed on 16 April 2023).

- Gillespie, M.; Jassal, B.; Stephan, R.; Milacic, M.; Rothfels, K.; Senff-Ribeiro, A.; Griss, J.; Sevilla, C.; Matthews, L.; Gong, C.; et al. The reactome pathway knowledgebase 2022. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D687–D692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Gable, A.L.; Lyon, D.; Junge, A.; Wyder, S.; Huerta-Cepas, J.; Simonovic, M.; Doncheva, N.T.; Morris, J.H.; Bork, P.; et al. STRING v11: Protein-protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D607–D613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Handsaker, B.; Wysoker, A.; Fennell, T.; Ruan, J.; Homer, N.; Marth, G.; Abecasis, G.; Durbin, R.; Genome Project Data Processing, S. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2078–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koboldt, D.C.; Zhang, Q.; Larson, D.E.; Shen, D.; McLellan, M.D.; Lin, L.; Miller, C.A.; Mardis, E.R.; Ding, L.; Wilson, R.K. VarScan 2: Somatic mutation and copy number alteration discovery in cancer by exome sequencing. Genome Res. 2012, 22, 568–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene_Id a | Symbol | Chromosome b | Gene_Biotype | Description | Log2fc c | Logcpm d | p Value e | FDR f |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain | ||||||||

| ENSSSCG00000002529 | AEMK02000452.1 | pseudogene | −2.6084 | 0.2896 | 2.52 × 10−12 | 3.88 × 10−8 | ||

| ENSSSCG00000041050 | 2 | lncRNA | −1.1361 | 5.0041 | 6.54 × 10−10 | 5.03 × 10−6 | ||

| ENSSSCG00000008995 | LRAT | 8 | protein_coding | lecithin retinol acyltransferase (Source: VGNC Symbol; Acc: VGNC: 89798) | −3.2222 | 0.9333 | 2.21 × 10−9 | 1.13 × 10−5 |

| ENSSSCG00000000207 | 5 | protein_coding | −1.8664 | 1.1183 | 7.49 × 10−9 | 2.88 × 10−5 | ||

| ENSSSCG00000048719 | 4 | lncRNA | −2.3907 | 2.7621 | 3.39 × 10−8 | 1.04 × 10−4 | ||

| ENSSSCG00000037684 | PDYN | 17 | protein_coding | prodynorphin (Source: VGNC Symbol; Acc: VGNC: 96477) | −1.8890 | 1.9398 | 1.20 × 10−7 | 3.08 × 10−4 |

| ENSSSCG00000041461 | AEMK02000489.1 | lncRNA | −1.0474 | 6.2832 | 1.44 × 10−6 | 0.0032 | ||

| ENSSSCG00000031141 | 9 | protein_coding | 0.7673 | 5.3265 | 4.02 × 10−6 | 0.0077 | ||

| ENSSSCG00000014876 | MYO7A | 9 | protein_coding | myosin VIIA (Source: VGNC Symbol; Acc: VGNC: 90533) | −1.2258 | 2.8836 | 1.04 × 10−5 | 0.0178 |

| ENSSSCG00000010017 | SMTN | 14 | protein_coding | smoothelin (Source: VGNC Symbol; Acc: VGNC: 93267) | −0.6804 | 5.0354 | 1.35 × 10−5 | 0.0207 |

| ENSSSCG00000018076 | tRNA-Ser | MT | Mt_tRNA | Product = tRNA-Ser | −1.1040 | 3.7806 | 1.66 × 10−5 | 0.0232 |

| ENSSSCG00000018061 | 12S rRNA | MT | Mt_rRNA | product = 12S ribosomal RNA | −0.6911 | 7.5659 | 2.82 × 10−5 | 0.0362 |

| ENSSSCG00000035731 | 1 | lncRNA | −1.1817 | 3.2115 | 3.44 × 10−5 | 0.0407 | ||

| ENSSSCG00000008997 | FGB | 8 | protein_coding | fibrinogen beta chain (Source: VGNC Symbol; Acc: VGNC: 98927) | −1.3491 | 1.5436 | 3.96 × 10−5 | 0.0435 |

| ENSSSCG00000043245 | 6 | lncRNA | 3.6467 | 0.8892 | 4.69 × 10−5 | 0.0481 | ||

| ENSSSCG00000018071 | tRNA-Ala | MT | Mt_tRNA | product = tRNA-Ala | 9.4169 | 0.5293 | 5.40 × 10−5 | 0.0520 |

| ENSSSCG00000024249 | GABRR2 | 1 | protein_coding | gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor subunit rho2 (Source: HGNC Symbol; Acc: HGNC: 4091) | 3.9193 | 1.1744 | 6.64 × 10−5 | 0.0601 |

| ENSSSCG00000008898 | 8 | protein_coding | HOP homeobox (Source: VGNC Symbol; Acc: VGNC: 88932) | −0.6543 | 6.0757 | 8.68 × 10−5 | 0.0742 | |

| ENSSSCG00000044872 | 8 | lncRNA | −2.0276 | 0.6183 | 9.28 × 10−5 | 0.0751 | ||

| Heart | ||||||||

| ENSSSCG00000031876 | TMEM159 | 3 | protein_coding | transmembrane protein 159 (Source: HGNC Symbol; Acc: HGNC: 30136) | −1.6888 | 3.5787 | 9.09 × 10−16 | 1.25 × 10−11 |

| ENSSSCG00000013513 | PLIN5 | 2 | protein_coding | perilipin 5 (Source: VGNC Symbol; Acc: VGNC: 91561) | −1.7601 | 3.7959 | 4.31 × 10−11 | 2.97 × 10−7 |

| ENSSSCG00000002529 | AEMK02000452.1 | pseudogene | −2.5629 | 0.6598 | 4.22 × 10−9 | 1.94 × 10−5 | ||

| ENSSSCG00000000207 | 5 | protein_coding | −1.1382 | 3.2356 | 3.42 × 10−6 | 0.0118 | ||

| ENSSSCG00000009498 | 11 | protein_coding | 3.8297 | 0.3891 | 8.24 × 10−6 | 0.0227 | ||

| ENSSSCG00000018095 | tRNA-Thr | MT | Mt_tRNA | product = tRNA-Thr | 8.4889 | −0.0175 | 1.38 × 10−5 | 0.0318 |

| ENSSSCG00000045913 | AEMK02000489.1 | lncRNA | 1.0243 | 4.0233 | 3.30 × 10−5 | 0.0648 | ||

| ENSSSCG00000018070 | tRNA-Trp | MT | Mt_tRNA | product = tRNA-Trp | 9.7782 | 3.3464 | 4.20 × 10−5 | 0.0722 |

| ENSSSCG00000007552 | 3 | protein_coding | 1.6328 | 3.3521 | 4.76 × 10−5 | 0.0729 | ||

| ENSSSCG00000018071 | tRNA-Ala | MT | Mt_tRNA | product = tRNA-Ala | 9.4738 | 0.9580 | 5.62 × 10−5 | 0.0732 |

| ENSSSCG00000014921 | PRSS23 | 9 | protein_coding | serine protease 23 (Source: VGNC Symbol; Acc: VGNC: 91880) | −0.6539 | 5.0841 | 5.85 × 10−5 | 0.0732 |

| ENSSSCG00000003616 | FAM167B | 6 | protein_coding | family with sequence similarity 167 member B (Source: VGNC Symbol; Acc: VGNC: 87925) | −0.7897 | 3.3686 | 7.56 × 10−5 | 0.0754 |

| ENSSSCG00000010096 | AIFM3 | 14 | protein_coding | apoptosis inducing factor mitochondria associated 3 (Source: VGNC Symbol; Acc: VGNC: 85200) | −1.8782 | 2.3705 | 7.60 × 10−5 | 0.0754 |

| ENSSSCG00000029268 | TOPAZ1 | 13 | protein_coding | testis and ovary specific PAZ domain containing 1 (Source: VGNC Symbol; Acc: VGNC: 94314) | 1.0174 | 3.5161 | 7.67 × 10−5 | 0.0754 |

| ENSSSCG00000050540 | 8 | lncRNA | 1.4389 | 2.6459 | 9.88 × 10−5 | 0.0874 | ||

| ENSSSCG00000026686 | PDZD9 | 3 | protein_coding | PDZ domain containing 9 (Source: VGNC Symbol; Acc: VGNC: 91297) | 1.0081 | 2.6808 | 1.04 × 10−4 | 0.0874 |

| ENSSSCG00000018080 | ATP8 | MT | protein_coding | mitochondrially encoded ATP synthase membrane subunit 8 (Source: VGNC Symbol; Acc: VGNC: 99789) | 4.4755 | 5.6610 | 1.08 × 10−4 | 0.0874 |

| ENSSSCG00000024837 | SYT12 | 2 | protein_coding | synaptotagmin 12 (Source:VGNC Symbol; Acc: VGNC: 93681) | −1.1184 | 1.8219 | 1.16 × 10−4 | 0.0885 |

| Liver | ||||||||

| ENSSSCG00000031474 | PTK6 | 17 | protein_coding | protein tyrosine kinase 6 (Source: VGNC Symbol; Acc: VGNC: 96517) | −5.5813 | −0.0562 | 3.88 × 10−17 | 5.55 × 10−13 |

| ENSSSCG00000003755 | MCOLN2 | 6 | protein_coding | mucolipin TRP cation channel 2 (Source: VGNC Symbol; Acc: VGNC: 90080) | 3.4286 | 3.1445 | 5.10 × 10−12 | 3.65 × 10−8 |

| ENSSSCG00000002529 | AEMK02000452.1 | pseudogene | −2.2307 | 1.4978 | 2.98 × 10−10 | 1.42 × 10−6 | ||

| ENSSSCG00000000207 | 5 | protein_coding | −1.3211 | 3.3023 | 1.82 × 10−7 | 6.41 × 10−4 | ||

| ENSSSCG00000017220 | OTOP3 | 12 | protein_coding | otopetrin 3 (Source: VGNC Symbol; Acc: VGNC: 91095) | −3.2197 | 2.6204 | 2.24 × 10−7 | 6.41 × 10−4 |

| ENSSSCG00000050540 | 8 | lncRNA | 1.7140 | 3.7928 | 4.50 × 10−7 | 0.0011 | ||

| ENSSSCG00000016401 | KIF1A | 15 | protein_coding | kinesin family member 1A (Source: HGNC Symbol; Acc: HGNC: 888) | 3.6472 | 2.7749 | 6.73 × 10−7 | 0.0014 |

| ENSSSCG00000049801 | 8 | lncRNA | 2.3897 | 1.9827 | 2.11 × 10−6 | 0.0038 | ||

| ENSSSCG00000047296 | 8 | lncRNA | 2.5920 | 1.0668 | 2.41 × 10−6 | 0.0038 | ||

| ENSSSCG00000034853 | Y | protein_coding | 4.2692 | −0.5967 | 3.69 × 10−6 | 0.0053 | ||

| ENSSSCG00000032896 | 10 | protein_coding | 2.4283 | 1.3265 | 8.02 × 10−6 | 0.0104 | ||

| ENSSSCG00000040822 | RERGL | 5 | protein_coding | RERG like (Source: VGNC Symbol; Acc: VGNC: 92218) | 2.7953 | −0.0188 | 1.73 × 10−5 | 0.0206 |

| ENSSSCG00000001484 | TINAG | 7 | protein_coding | tubulointerstitial nephritis antigen (Source: VGNC Symbol; Acc: VGNC: 93998) | −2.2315 | 0.6368 | 3.09 × 10−5 | 0.0340 |

| ENSSSCG00000018070 | tRNA-Trp | MT | Mt_tRNA | product = tRNA-Trp | 9.4671 | 0.7267 | 5.85 × 10−5 | 0.0598 |

| ENSSSCG00000046246 | 7 | pseudogene | 2.5585 | 0.3769 | 9.18 × 10−5 | 0.0876 | ||

| ENSSSCG00000015002 | ELMOD1 | 9 | protein_coding | ELMO domain containing 1 (Source: VGNC Symbol; Acc: VGNC: 87652) | 5.3844 | −0.2513 | 1.03 × 10−4 | 0.0912 |

| ENSSSCG00000004291 | NT5E | 1 | protein_coding | 5′-nucleotidase ecto (Source: VGNC Symbol; Acc: VGNC: 90925) | 1.2377 | 2.9849 | 1.10 × 10−4 | 0.0912 |

| ENSSSCG00000003603 | COL16A1 | 6 | protein_coding | collagen type XVI alpha 1 chain (Source: VGNC Symbol; Acc: VGNC: 86867) | 1.4794 | 3.3102 | 1.15 × 10−4 | 0.0912 |

| ENSSSCG00000035297 | ISG12(A) | 7 | protein_coding | putative ISG12(a) protein (Source: NCBI gene (formerly Entrezgene); Acc: 100153902) | −1.5001 | 4.6091 | 1.24 × 10−4 | 0.0937 |

| Reactome_ID | Reactome_Term | Brain | Heart | Liver |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 389661 | GLYOXYLATE METABOLISM AND GLYCINE DEGRADATION | 0.2416 | 0.0779 | 0.2376 |

| 909733 | INTERFERON ALPHA BETA SIGNALLING | 0.1460 | 0.0281 | 0.2452 |

| 913531 | INTERFERON SIGNALLING | 0.2492 | 0.0783 | 0.1927 |

| 877300 | INTERFERON GAMMA SIGNALLING | 0.0625 | 0.1082 | na |

| 68962 | ACTIVATION OF THE PRE-REPLICATIVE COMPLEX | na | 0.2440 | 0.0713 |

| 69190 | DNA STRAND ELONGATION | na | 0.1688 | 0.2299 |

| 114508 | EFFECTS OF PIP2 HYDROLYSIS | na | 0.2386 | 0.2465 |

| 187577 | SCF(SKP2)-MEDIATED DEGRADATION OF P27 P21 | na | 0.1373 | 0.0031 |

| 191273 | CHOLESTEROL BIOSYNTHESIS | 0.2346 | na | 0.0004 |

| 196854 | METABOLISM OF VITAMINS AND COFACTORS | 0.1906 | na | 0.2291 |

| 1474290 | COLLAGEN FORMATION | na | 0.2497 | 0.0000 |

| 1650814 | COLLAGEN BIOSYNTHESIS AND MODIFYING ENZYMES | na | 0.2481 | 0.0000 |

| 5619115 | DISORDERS OF TRANSMEMBRANE TRANSPORTERS | na | 0.2397 | 0.2397 |

| 6806667 | METABOLISM OF FAT-SOLUBLE VITAMINS | 0.0052 | na | 0.1915 |

| 8940973 | RUNX2 REGULATES OSTEOBLAST DIFFERENTIATION | 0.2115 | na | 0.1644 |

| 8941326 | RUNX2 REGULATES BONE DEVELOPMENT | 0.1433 | na | 0.2184 |

| 9658195 | LEISHMANIA INFECTION | 0.2358 | na | 0.2205 |

| 9662851 | ANTI-INFLAMMATORY RESPONSE FAVOURING LEISHMANIA PARASITE INFECTION | 0.1319 | na | 0.1506 |

| 9664323 | FCGR3A-MEDIATED IL10 SYNTHESIS | 0.2429 | na | 0.0510 |

| 9664433 | LEISHMANIA PARASITE GROWTH AND SURVIVAL | 0.1316 | na | 0.1489 |

| R-HSA-2173782 | BINDING AND UPTAKE OF LIGANDS BY SCAVENGER RECEPTORS | na | 0.1789 | 0.1650 |

| R-HSA-8948216 | COLLAGEN CHAIN TRIMERISATION | na | 0.1823 | 0.0000 |

| R-HSA-983189 | KINESINS | na | 0.2124 | 0.2295 |

| Reactome_ID | Reactome_Term | Brain | Heart | Liver |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R-HSA-1428517.1 | THE CITRIC ACID (TCA) CYCLE AND RESPIRATORY ELECTRON TRANSPORT | 0.0083 | 0.0198 | 0.0781 |

| 163200 | RESPIRATORY ELECTRON TRANSPORT, ATP SYNTHESIS BY CHEMIOSMOTIC COUPLING, AND HEAT PRODUCTION BY UNCOUPLING PROTEINS | 0.0653 | 0.0139 | 0.0673 |

| R-HSA-611105.3 | RESPIRATORY ELECTRON TRANSPORT | 0.0255 | 0.0365 | 0.1497 |

| R-HSA-3000171.3 | NON-INTEGRIN MEMBRANE-ECM INTERACTIONS | 0.1462 | 0.0184 | 0.1450 |

| 5173214 | O-GLYCOSYLATION OF TSR DOMAIN-CONTAINING PROTEINS | na | 0.0000 | 0.0579 |

| 9031628 | NGF-STIMULATED TRANSCRIPTION | na | 0.0529 | 0.0057 |

| 5083635 | DEFECTIVE B3GALTL CAUSES PPS | na | 0.0000 | 0.0592 |

| R-HSA-1296071.2 | POTASSIUM CHANNELS | na | 0.0497 | 0.0123 |

| 198725 | NUCLEAR EVENTS (KINASE AND TRANSCRIPTION FACTOR ACTIVATION) | na | 0.0631 | 0.0053 |

| R-HSA-445355.6 | SMOOTH MUSCLE CONTRACTION | na | 0.0104 | 0.0597 |

| R-HSA-5389840.1 | MITOCHONDRIAL TRANSLATION ELONGATION | na | 0.0154 | 0.0707 |

| 5419276 | MITOCHONDRIAL TRANSLATION TERMINATION | na | 0.0077 | 0.0946 |

| R-HSA-3906995.3 | DISEASES ASSOCIATED WITH O-GLYCOSYLATION OF PROTEINS | na | 0.0010 | 0.1056 |

| 418597 | G ALPHA (Z) SIGNALLING EVENTS | na | 0.0584 | 0.0598 |

| R-HSA-77289.5 | MITOCHONDRIAL FATTY ACID BETA-OXIDATION | 0.0539 | 0.0656 | na |

| R-HSA-187037.2 | SIGNALLING BY NTRK1 (TRKA) | na | 0.0871 | 0.0418 |

| R-HSA-1474228.4 | DEGRADATION OF THE EXTRACELLULAR MATRIX | na | 0.0132 | 0.1168 |

| 69017 | CDK-MEDIATED PHOSPHORYLATION AND REMOVAL OF CDC6 | na | 0.1258 | 0.0089 |

| R-HSA-69610.4 | P53-INDEPENDENT DNA DAMAGE RESPONSE | na | 0.1223 | 0.0214 |

| R-HSA-156842.2 | EUKARYOTIC TRANSLATION ELONGATION | na | 0.0000 | 0.1449 |

| R-HSA-5368287.1 | MITOCHONDRIAL TRANSLATION | na | 0.0049 | 0.1403 |

| R-HSA-156902.2 | PEPTIDE CHAIN ELONGATION | na | 0.0000 | 0.1475 |

| R-HSA-180585.1 | VIF-MEDIATED DEGRADATION OF APOBEC3G | na | 0.1197 | 0.0304 |

| R-HSA-69601.3 | UBIQUITIN-MEDIATED DEGRADATION OF PHOSPHORYLATED CDC25A | na | 0.1197 | 0.0324 |

| R-HSA-977444.3 | GABA B RECEPTOR ACTIVATION | na | 0.1299 | 0.0255 |

| R-HSA-450408.3 | AUF1 (HNRNP D0) BINDS AND DESTABILISES MRNA | na | 0.1455 | 0.0106 |

| R-HSA-5368286.1 | MITOCHONDRIAL TRANSLATION INITIATION | na | 0.0048 | 0.1525 |

| R-HSA-69613.2 | P53-INDEPENDENT G1 S DNA DAMAGE CHECKPOINT | na | 0.1405 | 0.0182 |

| 5619084 | ABC TRANSPORTER DISORDERS | na | 0.1279 | 0.0324 |

| R-HSA-6799198.1 | COMPLEX I BIOGENESIS | na | 0.0592 | 0.1032 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Okada, T.; Penn, A.; St. John, J.C. Mitochondrial DNA Supplementation of Oocytes Has Downstream Effects on the Transcriptional Profiles of Sus scrofa Adult Tissues with High mtDNA Copy Number. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7545. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24087545

Okada T, Penn A, St. John JC. Mitochondrial DNA Supplementation of Oocytes Has Downstream Effects on the Transcriptional Profiles of Sus scrofa Adult Tissues with High mtDNA Copy Number. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023; 24(8):7545. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24087545

Chicago/Turabian StyleOkada, Takashi, Alexander Penn, and Justin C. St. John. 2023. "Mitochondrial DNA Supplementation of Oocytes Has Downstream Effects on the Transcriptional Profiles of Sus scrofa Adult Tissues with High mtDNA Copy Number" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 24, no. 8: 7545. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24087545

APA StyleOkada, T., Penn, A., & St. John, J. C. (2023). Mitochondrial DNA Supplementation of Oocytes Has Downstream Effects on the Transcriptional Profiles of Sus scrofa Adult Tissues with High mtDNA Copy Number. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(8), 7545. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24087545