Case Report of Suspected Gonadal Mosaicism in FOXP1-Related Neurodevelopmental Disorder

Abstract

:1. Introduction

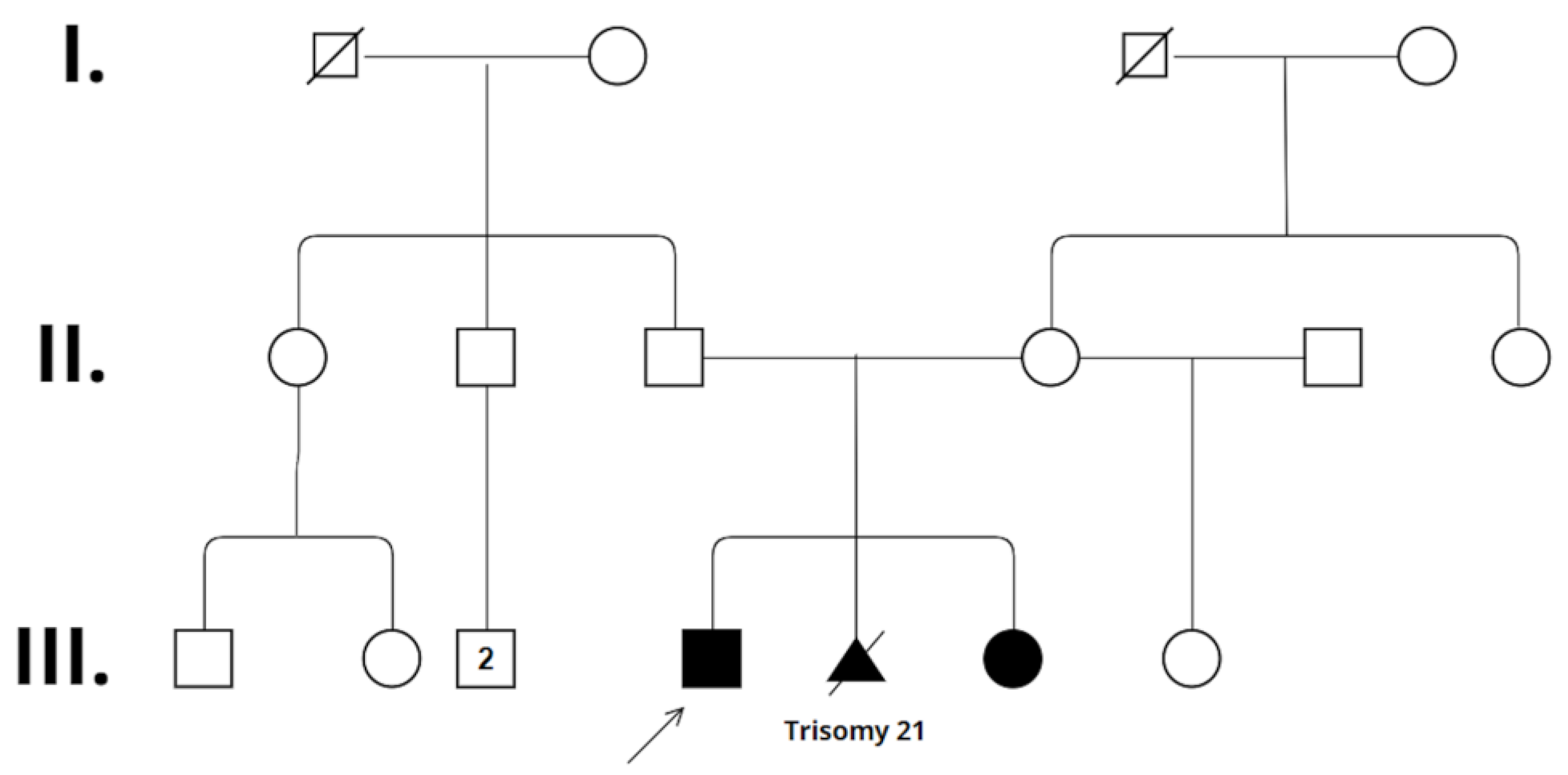

2. Case Presentation

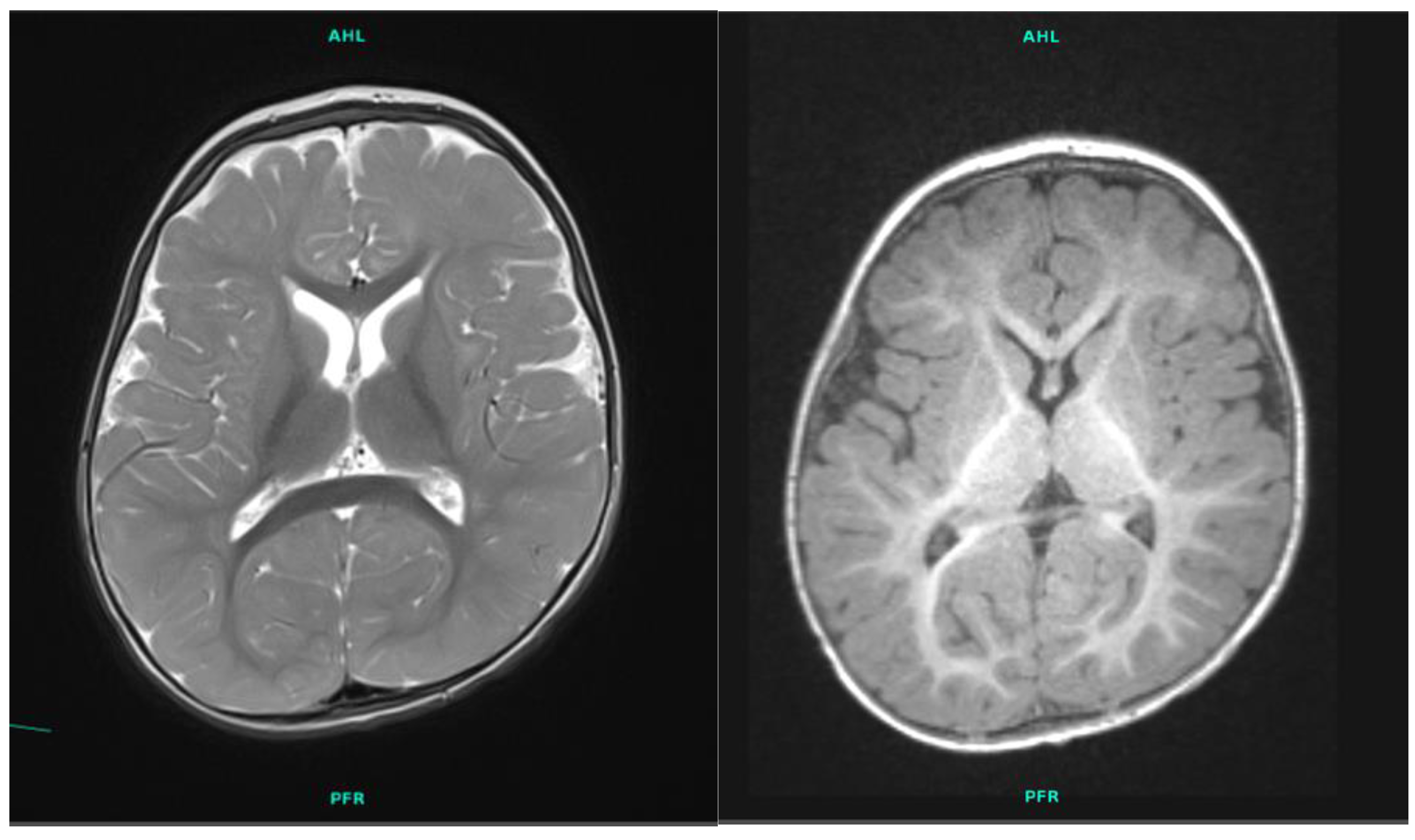

2.1. Patient 1

2.2. Patient 2

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Methods

5.1. GTG Banding

5.2. FISH

5.3. Array CGH

5.4. WES

5.5. Targeted Mutation Analysis

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Parenti, I.; Rabaneda, L.G.; Schoen, H.; Novarino, G. Neurodevelopmental Disorders: From Genetics to Functional Pathways. Trends Neurosci. 2020, 43, 608–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shu, W.; Yang, H.; Zhang, L.; Lu, M.M.; Morrisey, E.E. Characterization of a new subfamily of winged-helix/forkhead (Fox) genes that are expressed in the lung and act as transcriptional repressors. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 27488–27497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlsson, P.; Mahlapuu, M. Forkhead transcription factors: Key players in development and metabolism. Dev. Biol. 2002, 250, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araujo, D.J.; Anderson, A.G.; Berto, S.; Runnels, W.; Harper, M.; Ammanuel, S.; Rieger, M.A.; Huang, H.C.; Rajkovich, K.; Loerwald, K.W.; et al. FoxP1 orchestration of ASD-relevant signaling pathways in the striatum. Genes Dev. 2015, 29, 2081–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, H.; Wang, B.; Borde, M.; Nardone, J.; Maika, S.; Allred, L.; Tucker, P.W.; Rao, A. Foxp1 is an essential transcriptional regulator of B cell development. Nat. Immunol. 2006, 7, 819–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmesino, E.; Rousso, D.L.; Kao, T.J.; Klar, A.; Laufer, E.; Uemura, O.; Okamoto, H.; Novitch, B.G.; Kania, A. Foxp1 and lhx1 coordinate motor neuron migration with axon trajectory choice by gating Reelin signalling. PLoS Biol. 2010, 8, e1000446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, C.; Sakuma, M.; Mooroka, T.; Liscoe, A.; Gao, H.; Croce, K.J.; Sharma, A.; Kaplan, D.; Greaves, D.R.; Wang, Y.; et al. Down-regulation of the forkhead transcription factor Foxp1 is required for monocyte differentiation and macrophage function. Blood 2008, 112, 4699–4711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Weidenfeld, J.; Lu, M.M.; Maika, S.; Kuziel, W.A.; Morrisey, E.E.; Tucker, P.W. Foxp1 regulates cardiac outflow tract, endocardial cushion morphogenesis and myocyte proliferation and maturation. Development 2004, 131, 4477–4487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jepsen, K.; Gleiberman, A.S.; Shi, C.; Simon, D.I.; Rosenfeld, M.G. Cooperative regulation in development by SMRT and FOXP1. Genes Dev. 2008, 22, 740–745. [Google Scholar]

- Meerschaut, I.; Rochefort, D.; Revençu, N.; Pètre, J.; Corsello, C.; Rouleau, G.A.; Hamdan, F.F.; Michaud, J.L.; Morton, J.; Radley, J.; et al. FOXP1-related intellectual disability syndrome: A recognisable entity. J. Med. Genet. 2017, 54, 613–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rappold, G.; Siper, P.; Kostic, A.; Braden, R.; Morgan, A.; Koene, S.; Kolevzon, A. FOXP1 Syndrome. In GeneReviews(®); Adam, M.P., Feldman, J., Mirzaa, G.M., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Bean, L.J.H., Gripp, K.W., Amemiya, A., Eds.; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano, R.; Gbekie, C.; Siper, P.M.; Srivastava, S.; Saland, J.M.; Sethuram, S.; Tang, L.; Drapeau, E.; Frank, Y.; Buxbaum, J.D.; et al. FOXP1 syndrome: A review of the literature and practice parameters for medical assessment and monitoring. J. Neurodev. Disord. 2021, 13, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Professional Release 2022.1. Available online: https://www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk/ (accessed on 17 April 2024).

- Wilkie, A.O.M.; Goriely, A. Gonadal mosaicism and non-invasive prenatal diagnosis for ‘reassurance’ in sporadic paternal age effect (PAE) disorders. Prenat. Diagn. 2017, 37, 946–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sollis, E.; Deriziotis, P.; Saitsu, H.; Miyake, N.; Matsumoto, N.; Hoffer, M.J.V.; Ruivenkamp, C.A.L.; Alders, M.; Okamoto, N.; Bijlsma, E.K.; et al. Equivalent missense variant in the FOXP2 and FOXP1 transcription factors causes distinct neurodevelopmental disorders. Hum. Mutat. 2017, 38, 1542–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, J.L.; Debost, J.P.G.; Morton, S.U.; Wigdor, E.M.; Heyne, H.O.; Lal, D.; Howrigan, D.P.; Bloemendal, A.; Larsen, J.T.; Kosmicki, J.A.; et al. Paternal-age-related de novo mutations and risk for five disorders. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRae, J.F.; Clayton, S.; Fitzgerald, T.W.; Kaplanis, J.; Prigmore, E.; Rajan, D.; Sifrim, A.; Aitken, S.; Akawi, N.; Alvi, M. Deciphering Developmental Disorders Study, Prevalence and architecture of de novo mutations in developmental disorders. Nature 2017, 542, 433–438. [Google Scholar]

- Mohiuddin, M.; Kooy, R.F.; Pearson, C.E. De novo mutations, genetic mosaicism and human disease. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 983668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadlubowska, M.K.; Schrauwen, I. Methods to Improve Molecular Diagnosis in Genomic Cold Cases in Pediatric Neurology. Genes 2022, 13, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisk, S.; Wachtmeister, A.; Laurell, T.; Lindstrand, A.; Jäntti, N.; Malmgren, H.; Lagerstedt-Robinson, K.; Tesi, B.; Taylan, F.; Nordgren, A. Detection of germline mosaicism in fathers of children with intellectual disability syndromes caused by de novo variants. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 2022, 10, e1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møller, R.S.; Liebmann, N.; Larsen, L.H.G.; Stiller, M.; Hentschel, J.; Kako, N.; Abdin, D.; Di Donato, N.; Pal, D.K.; Zacher, P.; et al. Parental mosaicism in epilepsies due to alleged de novo variants. Epilepsia 2019, 60, e63–e66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yang, X.; Chen, J.; Li, S.; Zeng, Q.; Huang, A.Y.; Ye, A.Y.; Yu, Z.; Wang, S.; Jiang, Y.; et al. ATP1A3 mosaicism in families with alternating hemiplegia of childhood. Clin. Genet. 2019, 96, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breuss, M.W.; Yang, X.; Gleeson, J.G. Sperm mosaicism: Implications for genomic diversity and disease. Trends Genet. TIG 2021, 37, 890–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, X.; Wei, L.; Bao, X. MECP2 germline mosaicism plays an important part in the inheritance of Rett syndrome: A study of MECP2 germline mosaicism in males. BMC Med. 2023, 21, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Liu, A.; Xu, X.; Yang, X.; Zeng, Q.; Ye, A.Y.; Yu, Z.; Wang, S.; Huang, A.Y.; Wu, X.; et al. Genomic mosaicism in paternal sperm and multiple parental tissues in a Dravet syndrome cohort. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 15677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bessenyei, B.; Balogh, I.; Mokánszki, A.; Ujfalusi, A.; Pfundt, R.; Szakszon, K. MED13L-related intellectual disability due to paternal germinal mosaicism. Cold Spring Harb. Mol. Case Stud. 2022, 8, a006124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caspersson, T.; Zech, L.; Johansson, C.; Modest, E.J. Identification of human chromosomes by DNA-binding fluorescent agents. Chromosoma 1970, 30, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinkel, D.; Landegent, J.; Collins, C.; Fuscoe, J.; Segraves, R.; Lucas, J.; Gray, J. Fluorescence in situ hybridization with human chromosome-specific libraries: Detection of trisomy 21 and translocations of chromosome 4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1988, 85, 9138–9142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kallioniemi, A.; Kallioniemi, O.P.; Sudar, D.; Rutovitz, D.; Gray, J.W.; Waldman, F.; Pinkel, D. Comparative genomic hybridization for molecular cytogenetic analysis of solid tumors. Science. (N. Y.) 1992, 258, 818–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. Points to consider in the clinical application of genomic sequencing. Genet. Med. Off. J. Am. Coll. Med. Genet. 2012, 14, 759–761. [Google Scholar]

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 4 years | 14 months |

| Sex | male | female |

| FOXP1 variant | c.1541G>A heterozygous | c.1541G>A heterozygous |

| Neurobehavioral features | ||

| History of hypotonia | + | + |

| Motor delays | + | + |

| Speech delays | + | + |

| Swallowing or feeding problems | - | + |

| ID or GDD | + | + |

| ASD features | + | - |

| Behavioral problems | + | - |

| Dysmorphic features | ||

| Head and facial features | prominent forehead frontal hair upsweep | prominent forehead frontal hair upsweep round face |

| Eyes | ocular hypertelorism | ocular hypertelorism |

| Ears | - | - |

| Nose | wide nasal bridge broad nasal tip | wide nasal bridge broad nasal tip |

| Mouth | - | - |

| Extremities | - | - |

| Other | - | - |

| Medical features associated with FOXP1 syndrome | ||

| Neurology | dyskinetic movements | - |

| EEG | negative | N/A |

| Brain MRI | smaller basal ganglia and cerebral atrophy | N/A |

| Endocrinology | N/A | N/A |

| Cardiac | N/A | N/A |

| Nephrology/urology | - | N/A |

| Ophthalmology | convergent strabismus | convergent strabismus |

| Other medical problems | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zsigmond, A.; Till, Á.; Bene, J.; Czakó, M.; Mikó, A.; Hadzsiev, K. Case Report of Suspected Gonadal Mosaicism in FOXP1-Related Neurodevelopmental Disorder. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5709. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25115709

Zsigmond A, Till Á, Bene J, Czakó M, Mikó A, Hadzsiev K. Case Report of Suspected Gonadal Mosaicism in FOXP1-Related Neurodevelopmental Disorder. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2024; 25(11):5709. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25115709

Chicago/Turabian StyleZsigmond, Anna, Ágnes Till, Judit Bene, Márta Czakó, Alexandra Mikó, and Kinga Hadzsiev. 2024. "Case Report of Suspected Gonadal Mosaicism in FOXP1-Related Neurodevelopmental Disorder" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 25, no. 11: 5709. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25115709