Galactic Cosmic Ray Particle Exposure Does Not Increase Protein Levels of Inflammation or Oxidative Stress Markers in Rat Microglial Cells In Vitro

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Viability

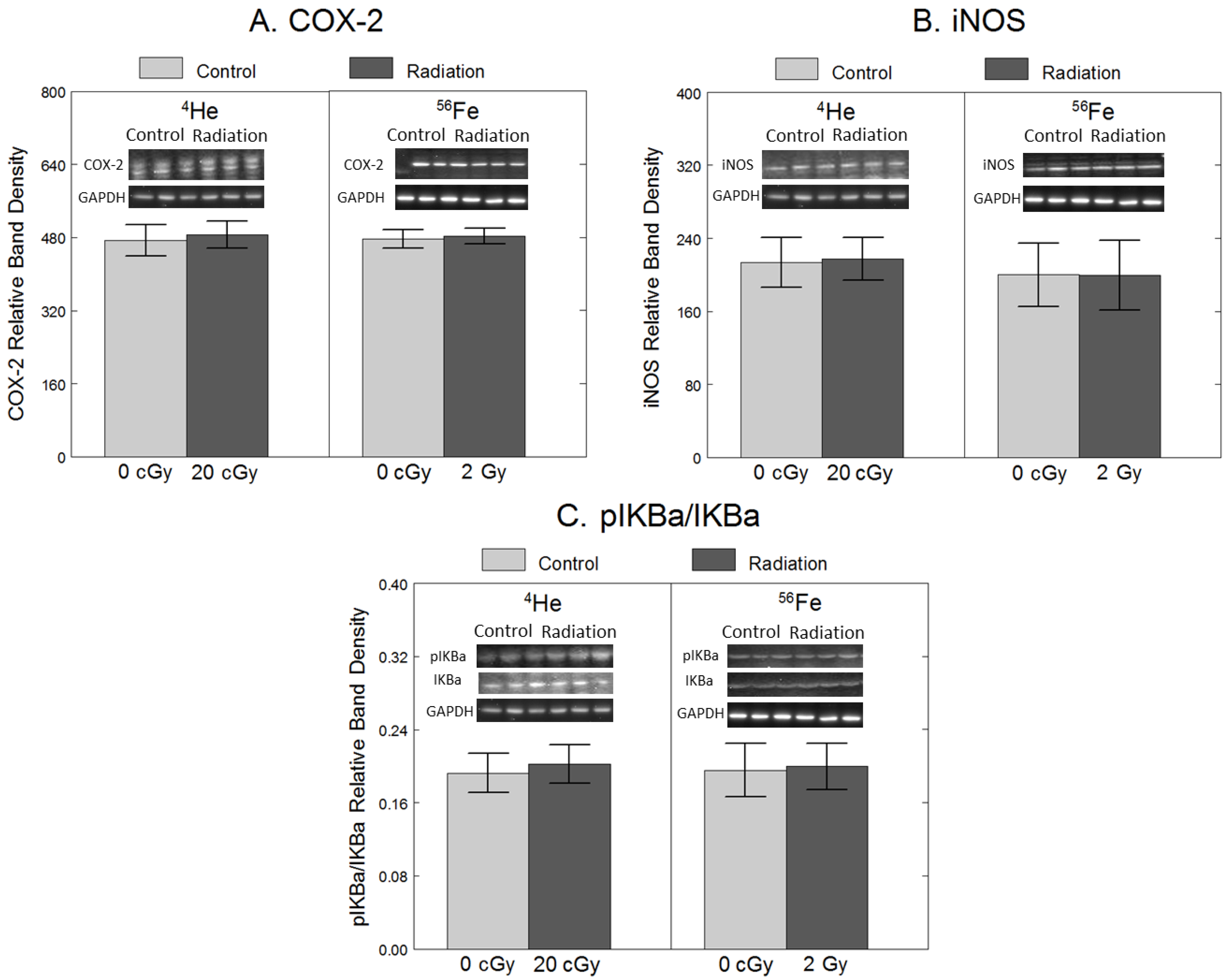

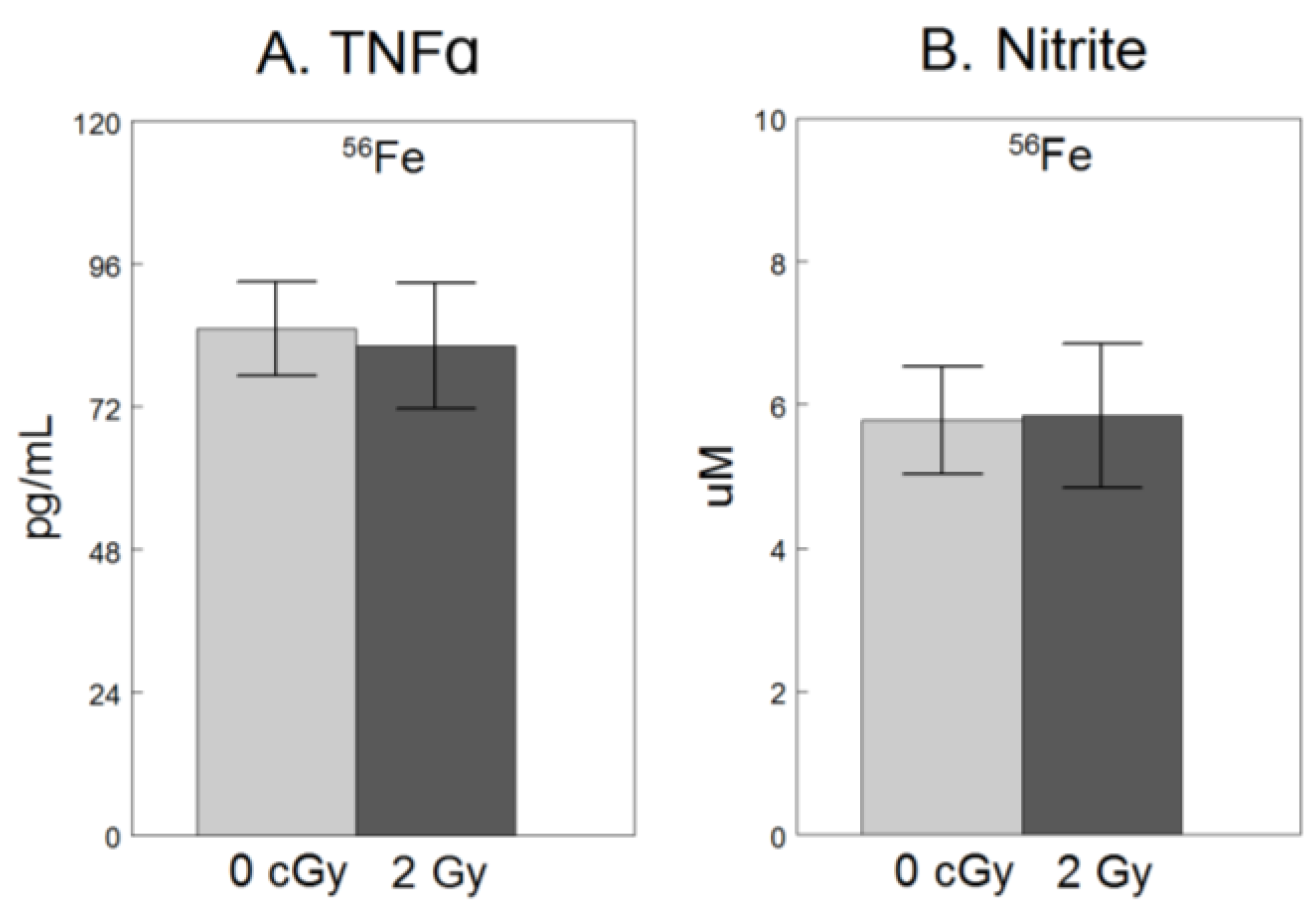

2.2. Inflammation

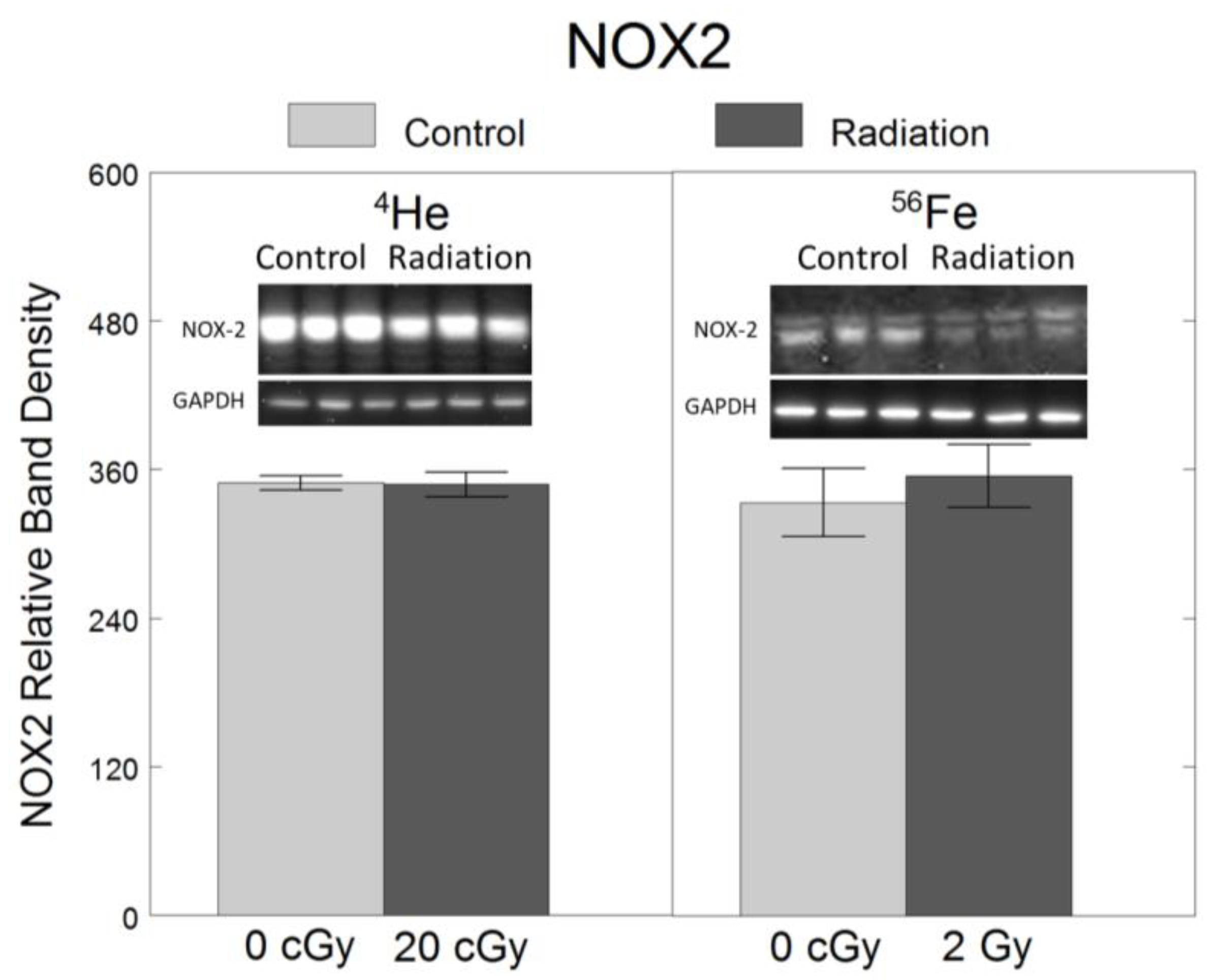

2.3. Oxidative Stress

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture and Irradiation Procedure

4.2. Cell Viability

4.3. Western Blots

4.4. TNFα Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

4.5. Nitrite Quantification

4.6. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Durante, M.; Cucinotta, F.A. Heavy ion carcinogenesis and human space exploration. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2008, 8, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabin, B.M.; Shukitt-Hale, B. A voyage to Mars: Space radiation, aging, and nutrition. Nutr. Aging 2014, 2, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, J.A.; Shukitt-Hale, B.; McEwen, J.; Rabin, B.M. CNS-induced deficits of heavy particle irradiation in space: The aging connection. Adv. Space Res. 2000, 25, 2057–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulose, S.M.; Bielinski, D.F.; Carrihill-Knoll, K.L.; Rabin, B.M.; Shukitt-Hale, B. Protective effects of blueberry- and strawberry diets on neuronal stress following exposure to 56Fe particles. Brain Res. 2014, 1593, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parihar, V.K.; Maroso, M.; Syage, A.; Allen, B.D.; Angulo, M.C.; Soltesz, I.; Limoli, C.L. Persistent nature of alterations in cognition and neuronal circuit excitability after exposure to simulated cosmic radiation in mice. Neurosci. Lett. 2018, 305, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dringen, R. Oxidative and antioxidative potential of brain microglial cells. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2005, 7, 1223–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lijia, Z.; Zhao, S.; Wang, X.; Wu, C.; Yang, J. A self-propelling cycle mediated by reactive oxide species and nitric oxide exists in LPS-activated microglia. Neurochem. Int. 2012, 61, 1220–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lull, M.E.; Block, M.L. Microglial activation and chronic neurodegeneration. Neurotherapeutics 2010, 7, 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Wu, X.; Block, M.L.; Liu, Y.; Breese, G.R.; Hong, J.S.; Knapp, D.J.; Crews, F.T. Systemic LPS causes chronic neuroinflammation and progressive neurodegeneration. Glia 2007, 55, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parihar, V.K.; Allen, B.D.; Caressi, C.; Kwok, S.; Chu, E.; Tran, K.K.; Chmielewski, N.N.; Giedzinski, E.; Acharya, M.M.; Britten, R.A.; et al. Cosmic radiation exposure and persistent cognitive dysfunction. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 34774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krukowski, K.; Grue, K.; Frias, E.S.; Pietrykowski, J.; Jones, T.; Nelson, G.; Rosi, S. Female mice are protected from space radiation-induced maladaptive responses. Brain Behav. Immun. 2018, 74, 106–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, B.D.; Syage, A.R.; Maroso, M.; Baddour, A.A.D.; Luong, V.; Minasyan, H.; Giedzinski, E.; West, B.L.; Soltesz, I.; Limoli, C.L.; et al. Mitigation of helium irradiation-induced brain injury by microglia depletion. J. Neuroinflamm. 2020, 17, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rola, R.; Sarkissian, V.; Obenaus, A.; Nelson, G.A.; Otsuka, S.; Limoli, C.L.; Fike, J.R. High-LET radiation induces inflammation and persistent changes in markers of hippocampal neurogenesis. Radiat. Res. 2005, 164 Pt 2, 556–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherry, J.D.; Liu, B.; Frost, J.L.; Lemere, C.A.; Williams, J.P.; Olschowka, J.A.; O’Banion, M.K. Galactic cosmic radiation leads to cognitive impairment and increased abeta plaque accumulation in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e53275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Hinshaw, R.G.; Le, K.X.; Park, M.A.; Wang, S.; Belanger, A.P.; Dubey, S.; Frost, J.L.; Shi, Q.; Holton, P.; et al. Space-like 56Fe irradiation manifests mild, early sex-specific behavioral and neuropathological changes in wildtype and Alzheimer’s-like transgenic mice. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raber, J.; Yamazaki, J.; Torres, E.R.S.; Kirchoff, N.; Stagaman, K.; Sharpton, T.; Turker, M.S.; Kronenberg, A. Combined Effects of Three High-Energy Charged Particle Beams Important for Space Flight on Brain, Behavioral and Cognitive Endpoints in B6D2F1 Female and Male Mice. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raber, J.; Fuentes Anaya, A.; Torres, E.R.S.; Lee, J.; Boutros, S.; Grygoryev, D.; Hammer, A.; Kasschau, K.D.; Sharpton, T.J.; Turker, M.S.; et al. Effects of Six Sequential Charged Particle Beams on Behavioral and Cognitive Performance in B6D2F1 Female and Male Mice. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweet, T.B.; Panda, N.; Hein, A.M.; Das, S.L.; Hurley, S.D.; Olschowka, J.A.; Williams, J.P.; O’Banion, M.K. Central Nervous System Effects of Whole-Body Proton Irradiation. Radiat. Res. 2014, 182, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rola, R.; Fishman, K.; Baure, J.; Rosi, S.; Lamborn, K.R.; Obenaus, A.; Nelson, G.A.; Fike, J.R. Hippocampal Neurogenesis and Neuroinflammation after Cranial Irradiation with 56Fe Particles. Radiat. Res. 2008, 169, 626–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, M.T.; Nisbet, A.; Jones, B.; Suzuki, M.; Matsufuji, N.; Murakami, T.; Bradley, D.A. Ion beams for space radiation radiobiological effect studies. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2019, 165, 108373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucinotta, F.A.; Cacao, E. Risks of cognitive detriments after low dose heavy ion and proton exposures. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2019, 95, 985–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betlazar, C.; Middleton, R.J.; Banati, R.B.; Liu, G.J. The impact of high and low dose ionising radiation on the central nervous system. Redox Biol. 2016, 9, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A.; Han, C.; Fang, X.; Sun, J.; Chen, X.; Wan, F. Extractable and non-extractable polyphenols from blueberries modulate LPS-induced expression of iNOS and COX-2 in RAW264.7 macrophages via the NF-kappaB signalling pathway. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 3393–3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozic, I.; Savic, D.; Laketa, D.; Bjelobaba, I.; Milenkovic, I.; Pekovic, S.; Nedeljkovic, N.; Lavrnja, I. Benfotiamine attenuates inflammatory response in LPS stimulated BV-2 microglia. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, M.M.; Green, K.N.; Allen, B.D.; Najafi, A.R.; Syage, A.; Minasyan, H.; Le, M.T.; Kawashita, T.; Giedzinski, E.; Parihar, V.K.; et al. Elimination of microglia improves cognitive function following cranial irradiation. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Sui, G.; Rosa, P.M.; Zhao, W. Radiation-induced c-Jun activation depends on MEK1-ERK1/2 signaling pathway in microglial cells. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e36739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanan, S.; Kooshki, M.; Zhao, W.; Hsu, F.C.; Robbins, M.E. PPARalpha ligands inhibit radiation-induced microglial inflammatory responses by negatively regulating NF-kappaB and AP-1 pathways. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008, 45, 1695–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnegg, C.I.; Kooshki, M.; Hsu, F.C.; Sui, G.; Robbins, M.E. PPARdelta prevents radiation-induced proinflammatory responses in microglia via transrepression of NF-kappaB and inhibition of the PKCalpha/MEK1/2/ERK1/2/AP-1 pathway. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012, 52, 1734–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyrkanides, S.; Moore, A.H.; Olschowka, J.A.; Daeschner, J.C.; Williams, J.P.; Hansen, J.T.; Kerry O’Banion, M. Cyclooxygenase-2 modulates brain inflammation-related gene expression in central nervous system radiation injury. Mol. Brain Res. 2002, 104, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Dong, J.H.; Huang, G.D.; Qu, X.F.; Wu, G.; Dong, X.R. NF-κB signaling modulates radiation-induced microglial activation. Oncol. Rep. 2014, 31, 2555–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.L.; Tian, D.S.; Li, Z.W.; Qu, W.S.; Zhan, Y.; Xie, M.J.; Yu, Z.Y.; Wang, W.; Wu, G. Tamoxifen alleviates irradiation-induced brain injury by attenuating microglial inflammatory response in vitro and in vivo. Brain Res. 2010, 1316, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.Y.; Jung, J.S.; Kim, T.H.; Lim, S.J.; Oh, E.S.; Kim, J.Y.; Ji, K.A.; Joe, E.H.; Cho, K.H.; Han, I.O. Ionizing radiation induces astrocyte gliosis through microglia activation. Neurobiol. Dis. 2006, 21, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cekanaviciute, E.; Rosi, S.; Costes, S.V. Central Nervous System Responses to Simulated Galactic Cosmic Rays. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahoon, D.S.; Shukitt-Hale, B.; Bielinski, D.F.; Hawkins, E.M.; Cacioppo, A.M.; Rabin, B.M. Effects of partial- or whole-body exposures to 56Fe particles on brain function and cognitive performance in rats. Life Sci. Space Res. 2020, 27, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahoon, D.S.; Rabin, B.M.; Fisher, D.R.; Shukitt-Hale, B. Effects of HZE-particle exposure location and energy on brain inflammation and oxidative stress in rats. Radiat. Res. 2023, 200, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Tessa, C.; Sivertz, M.; Chiang, I.H.; Lowenstein, D.; Rusek, A. Overview of the NASA space radiation laboratory. Life Sci. Space Res. 2016, 11, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Luo, M.; Huang, G.; Zhang, J.; Tong, F.; Cheng, Y.; Cai, Q.; Dong, J.; Wu, G.; Cheng, J. Relationship between irradiation-induced neuro-inflammatory environments and impaired cognitive function in the developing brain of mice. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2015, 91, 224–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyrkanides, S.; Olschowka, J.A.; Williams, J.P.; Hansen, J.T.; O’Banion, M.K. TNFα and IL-1β mediate intercellular adhesion molecule-1 induction via microglia-astrocyte interaction in CNS radiation injury. J. Neuroimmunol. 1999, 95, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strober, W. Trypan Blue Exclusion Test of Cell Viability. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. 2015, 111, A3 B 1–A3 B 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahoon, D.S.; Fisher, D.R.; Lamon-Fava, S.; Wu, D.; Zheng, T.; Shukitt-Hale, B. Blueberry treatment administered before and/or after lipopolysaccharide stimulation attenuates inflammation and oxidative stress in rat microglial cells. Nutr. Neurosci. 2023, 26, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cahoon, D.S.; Fisher, D.R.; Rabin, B.M.; Lamon-Fava, S.; Wu, D.; Zheng, T.; Shukitt-Hale, B. Galactic Cosmic Ray Particle Exposure Does Not Increase Protein Levels of Inflammation or Oxidative Stress Markers in Rat Microglial Cells In Vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5923. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25115923

Cahoon DS, Fisher DR, Rabin BM, Lamon-Fava S, Wu D, Zheng T, Shukitt-Hale B. Galactic Cosmic Ray Particle Exposure Does Not Increase Protein Levels of Inflammation or Oxidative Stress Markers in Rat Microglial Cells In Vitro. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2024; 25(11):5923. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25115923

Chicago/Turabian StyleCahoon, Danielle S., Derek R. Fisher, Bernard M. Rabin, Stefania Lamon-Fava, Dayong Wu, Tong Zheng, and Barbara Shukitt-Hale. 2024. "Galactic Cosmic Ray Particle Exposure Does Not Increase Protein Levels of Inflammation or Oxidative Stress Markers in Rat Microglial Cells In Vitro" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 25, no. 11: 5923. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25115923

APA StyleCahoon, D. S., Fisher, D. R., Rabin, B. M., Lamon-Fava, S., Wu, D., Zheng, T., & Shukitt-Hale, B. (2024). Galactic Cosmic Ray Particle Exposure Does Not Increase Protein Levels of Inflammation or Oxidative Stress Markers in Rat Microglial Cells In Vitro. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25(11), 5923. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25115923