Rapid Determination of SARS-CoV-2 Integrity and Infectivity by Using Propidium Monoazide Coupled with Digital Droplet PCR

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

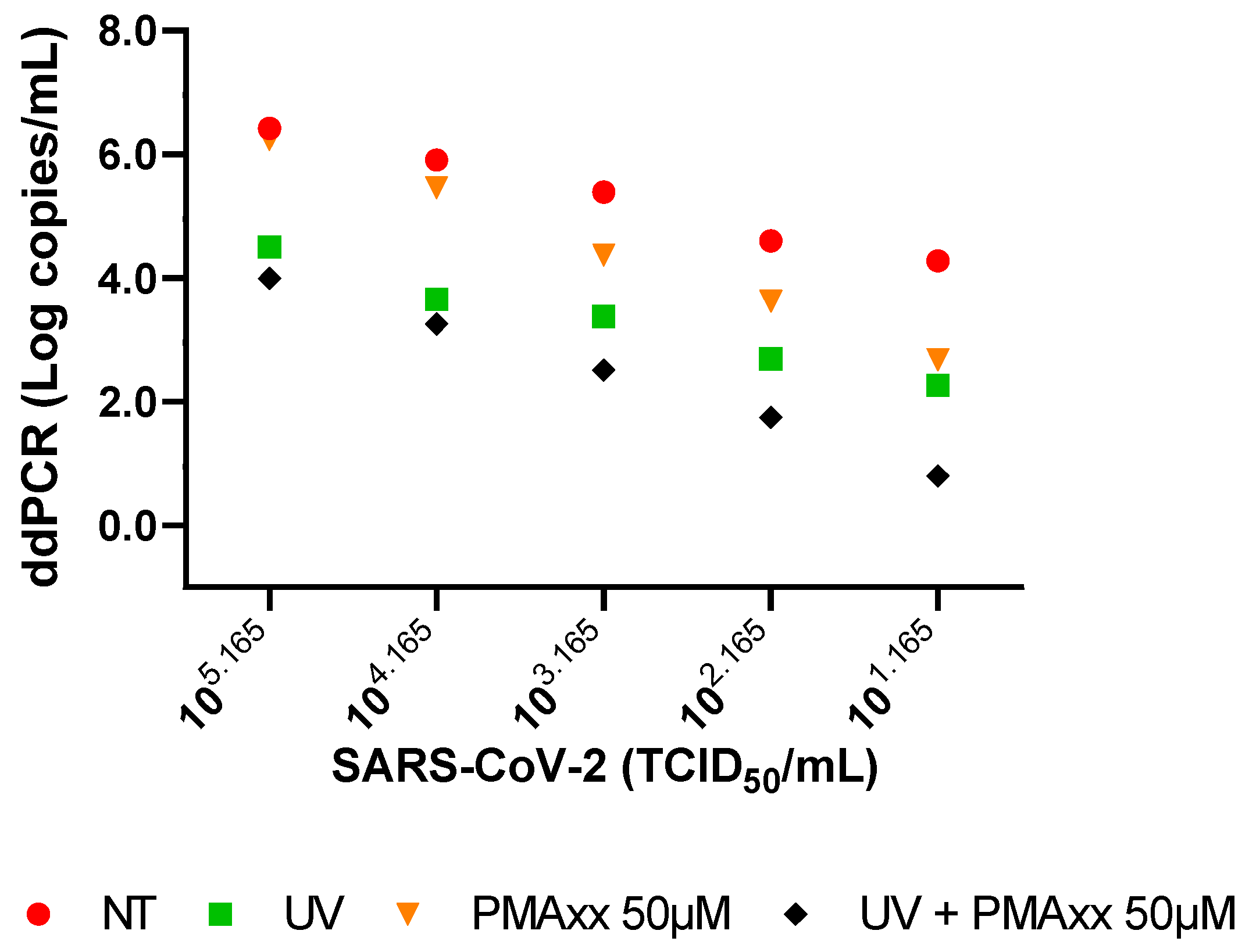

2.1. In Vitro Settings of PMAxx Treatment

2.2. Clinical Samples Treated with PMAxx

2.3. Comparison of PMAxx-ddPCR with SARS-CoV-2 Isolation and Negative-Chain PCR

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. SARS-CoV-2 Stock Preparation and UV Inactivation

4.2. Clinical Specimens

4.3. Propidium Monoazide Treatment and Viral RNA Extraction

4.4. SARS-CoV-2 Quantification with ddPCR

4.5. Negative-Chain SARS-CoV-2 RNA PCR

4.6. SARS-CoV-2 Isolation from Clinical Samples

4.7. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 (accessed on 3 May 2024).

- Chan, M.; Linn, M.M.N.; O’Hagan, T.; Guerra-Assunção, J.A.; Lackenby, A.; Workman, S.; Dacre, A.; Burns, S.O.; Breuer, J.; Hart, J.; et al. Persistent SARS-CoV-2 PCR Positivity Despite Anti-Viral Treatment in Immunodeficient Patients. J. Clin. Immunol. 2023, 43, 1083–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimaldi, P.; Russo, A.; Pisaturo, M.; Maggi, P.; Allegorico, E.; Gentile, I.; Sangiovanni, V.; Rossomando, A.; Pacilio, R.; Calabria, G.; et al. Clinical and epidemiological factors causing longer SARS-CoV-2 viral shedding: The results from the CoviCamp cohort. Infection 2024, 52, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danzetta, M.L.; Amato, L.; Cito, F.; Di Giuseppe, A.; Morelli, D.; Savini, G.; Mercante, M.T.; Lorusso, A.; Portanti, O.; Puglia, I.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 RNA Persistence in Naso-Pharyngeal Swabs. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carvalho, J.G.; Hvozdara, K. What are the Clinical Implications of a Positive RT-PCR Test 6 Months after a Mild SARS-CoV-2 Infection? Eur. J. Case Rep. Intern. Med. 2021, 8, 002463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laferl, H.; Kelani, H.; Seitz, T.; Holzer, B.; Zimpernik, I.; Steinrigl, A.; Schmoll, F.; Wenisch, C.; Allerberger, F. An approach to lifting self-isolation for health care workers with prolonged shedding of SARS-CoV-2 RNA. Infection 2021, 49, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institutes of Health. Available online: https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/special-populations/immunocompromised/ (accessed on 7 May 2024).

- Runfeng, L.; Yunlong, H.; Jicheng, H.; Weiqi, P.; Qinhai, M.; Yongxia, S.; Chufang, L.; Jin, Z.; Zhenhua, J.; Haiming, J.; et al. Lianhuaqingwen exerts anti-viral and anti-inflammatory activity against novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2). Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 156, 104761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manenti, A.; Maggetti, M.; Casa, E.; Martinuzzi, D.; Torelli, A.; Trombetta, C.M.; Marchi, S.; Montomoli, E. Evaluation of SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies using a CPE-based colorimetric live virus micro-neutralization assay in human serum samples. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 2096–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colavita, F.; Lapa, D.; Carletti, F.; Lalle, E.; Messina, F.; Rueca, M.; Matusali, G.; Meschi, S.; Bordi, L.; Marsella, P.; et al. Virological Characterization of the First 2 COVID-19 Patients Diagnosed in Italy: Phylogenetic Analysis, Virus Shedding Profile from Different Body Sites, and Antibody Response Kinetics. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2020, 7, ofaa403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iannetta, M.; Lalle, E.; Musso, M.; Carletti, F.; Scorzolini, L.; D’Abramo, A.; Chinello, P.; Castilletti, C.; Ippolito, G.; Capobianchi, M.R.; et al. Persistent detection of dengue virus RNA in vaginal secretion of a woman returning from Sri Lanka to Italy, April 2017. Euro Surveill 2017, 22, 30600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biava, M.; Caglioti, C.; Castilletti, C.; Bordi, L.; Carletti, F.; Colavita, F.; Quartu, S.; Nicastri, E.; Iannetta, M.; Vairo, F.; et al. Persistence of ZIKV-RNA in the cellular fraction of semen is accompanied by a surrogate-marker of viral replication. Diagnostic implications for sexual transmission. New Microbiol. 2018, 41, 30–33. [Google Scholar]

- Biava, M.; Caglioti, C.; Bordi, L.; Castilletti, C.; Colavita, F.; Quartu, S.; Nicastri, E.; Lauria, F.N.; Petrosillo, N.; Lanini, S.; et al. Detection of Viral RNA in Tissues following Plasma Clearance from an Ebola Virus Infected Patient. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e10006065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vita, S.; Bordi, L.; Sberna, G.; Caputi, P.; Lapa, D.; Corpolongo, A.; Mija, C.; D’Abramo, A.; Maggi, F.; Vairo, F.; et al. Autochthonous Dengue Fever in 2 Patients, Rome, Italy. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2024, 30, 183–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sberna, G.; Biagi, M.; Marafini, G.; Nardacci, R.; Biava, M.; Colavita, F.; Piselli, P.; Miraldi, E.; D’Offizi, G.; Capobianchi, M.R.; et al. In vitro Evaluation of Antiviral Efficacy of a Standardized Hydroalcoholic Extract of Poplar Type Propolis Against SARS-CoV-2. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 799546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Zhou, X.; He, X.; Wang, P.; Yue, S.; Wu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, Q.; Zhang, B.; Zhao, W. Detection of infectious dengue virus by selective real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Virol. Sin. 2016, 31, 342–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leifels, M.; Cheng, D.; Sozzi, E.; Shoults, D.C.; Wuertz, S.; Mongkolsuk, S.; Sirikanchana, K. Capsid integrity quantitative PCR to determine virus infectivity in environmental and food applications—A systematic review. Water Res. X 2020, 11, 100080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, W.; Xiong, J.; Nyaruaba, R.; Li, J.; Muturi, E.; Liu, H.; Yu, J.; Yang, H.; Wei, H. Rapid determination of infectious SARS-CoV-2 in PCR-positive samples by SDS-PMA assisted RT-qPCR. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 797, 149085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocker, A.; Cheung, C.Y.; Camper, A.K. Comparison of propidium monoazide with ethidium monoazide for differentiation of live vs. dead bacteria by selective removal of DNA from dead cells. J. Microbiol. Methods 2006, 67, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, M.R.; Fout, G.S.; Johnson, C.H.; White, K.M.; Parshionikar, S.U. Propidium monoazide reverse transcriptase PCR and RT-qPCR for detecting infectious enterovirus and norovirus. J. Virol. Methods. 2015, 219, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Qing, J.; Hu, D.; Vo, H.T.; Thi, K.T.; Wang, X.; Li, X. Application of propidium monoazide quantitative PCR to discriminate of infectious African swine fever viruses. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1290302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H.; Kang, G.; Woo, W.S.; Sohn, M.Y.; Son, H.J.; Park, C.I. Development of a Propidium Monoazide-Based Viability Quantitative PCR Assay for Red Sea Bream Iridovirus Detection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, D.; Qian, B.; Li, Y.; Zong, K.; Peng, W.; Liao, K.; Yu, X.; Sun, J.; Lv, X.; Ding, L.; et al. Prospects for the application of infectious virus detection technology based on propidium monoazide in African swine fever management. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1025758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrone, P.N.; Romsos, E.L.; Cleveland, M.H.; Vallone, P.M.; Kearsley, A.J. Affine analysis for quantitative PCR measurements. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2020, 412, 7977–7988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeJaco, R.F.; Roberts, M.J.; Romsos, E.L.; Vallone, P.M.; Kearsley, A.J. Reducing Bias and Quantifying Uncertainty in Fluorescence Produced by PCR. Bull. Math. Biol. 2023, 85, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Song, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wu, N.; Xu, J.; Sun, C.; Zhang, J.; Weng, T.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, Z.; et al. Molecular Architecture of the SARS-CoV-2 Virus. Cell 2020, 183, 730–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Scola, B.; Le Bideau, M.; Andreani, J.; Hoang, V.T.; Grimaldier, C.; Colson, P.; Gautret, P.; Raoult, D. Viral RNA load as determined by cell culture as a management tool for discharge of SARS-CoV-2 patients from infectious disease wards. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2020, 39, 1059–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beeching, N.J.; Fletcher, T.E.; Beadsworth, M.B.J. Covid-19: Testing times. BMJ 2020, 369, 1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaul, D. An overview of coronaviruses including the SARS-2 coronavirus—Molecular biology, epidemiology and clinical implications. Curr. Med. Res. Pract. 2020, 10, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Shan, Y.; Zhu, X.; An, B.; Luo, J.; Yang, N.; Zhao, K.; Wu, T.; Qiao, Q.; Zhu, F.; et al. Establishment and Evaluation of Propidium Monoazide-Digital Pcr (Pma-Dpcr) for Rapid Discrimination of Infectious Sars-Cov-2. SSRN, 2023; in preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roingeard, P.; Eymieux, S.; Burlaud-Gaillard, J.; Hourioux, C.; Patient, R.; Blanchard, E. The double-membrane vesicle (DMV): A virus-induced organelle dedicated to the replication of SARS-CoV-2 and other positive-sense single-stranded RNA viruses. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2022, 79, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gisaid. Available online: https://gisaid.org/ (accessed on 3 May 2024).

- European Virus Archive—GLOBAL. Available online: https://www.european-virus-archive.com/evag-news/sars-cov-2-collection (accessed on 3 May 2024).

- Reed, L.J.; Muench, H. A simple method of estimating fifty per cent endpoints. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1938, 27, 493–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biotium. Available online: https://biotium.com/ (accessed on 3 May 2024).

- Copan Italia. Available online: https://www.copangroup.com/ (accessed on 3 May 2024).

- Abbott Molecular. Available online: https://www.molecular.abbott/content/dam/add/molecular/alinity-m-sars-cov-2-assay/us/53-608191R11%20Alinity%20m%20SARS%20AMP%20Kit%20PI%20EUA_lg016.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2024).

- Qiagen. Available online: https://www.qiagen.com/us (accessed on 3 May 2024).

- Thermo-Fisher Scientific. Available online: https://www.thermofisher.com/it/en/home.html (accessed on 3 May 2024).

- Bio-Rad. Available online: https://www.bio-rad.com/ (accessed on 3 May 2024).

- Corman, V.M.; Landt, O.; Kaiser, M.; Molenkamp, R.; Meijer, A.; Chu, D.K.; Bleicker, T.; Brünink, S.; Schneider, J.; Schmidt, M.L.; et al. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Euro Surveill 2020, 25, 2000045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GraphPad Prism. Available online: https://www.graphpad.com/features (accessed on 3 May 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sberna, G.; Mija, C.; Lalle, E.; Rozera, G.; Matusali, G.; Carletti, F.; Girardi, E.; Maggi, F. Rapid Determination of SARS-CoV-2 Integrity and Infectivity by Using Propidium Monoazide Coupled with Digital Droplet PCR. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6156. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25116156

Sberna G, Mija C, Lalle E, Rozera G, Matusali G, Carletti F, Girardi E, Maggi F. Rapid Determination of SARS-CoV-2 Integrity and Infectivity by Using Propidium Monoazide Coupled with Digital Droplet PCR. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2024; 25(11):6156. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25116156

Chicago/Turabian StyleSberna, Giuseppe, Cosmina Mija, Eleonora Lalle, Gabriella Rozera, Giulia Matusali, Fabrizio Carletti, Enrico Girardi, and Fabrizio Maggi. 2024. "Rapid Determination of SARS-CoV-2 Integrity and Infectivity by Using Propidium Monoazide Coupled with Digital Droplet PCR" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 25, no. 11: 6156. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25116156

APA StyleSberna, G., Mija, C., Lalle, E., Rozera, G., Matusali, G., Carletti, F., Girardi, E., & Maggi, F. (2024). Rapid Determination of SARS-CoV-2 Integrity and Infectivity by Using Propidium Monoazide Coupled with Digital Droplet PCR. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25(11), 6156. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25116156