Intestinal Microbiota Increases Cell Proliferation of Colonic Mucosa in Human-Flora-Associated (HFA) Mice

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

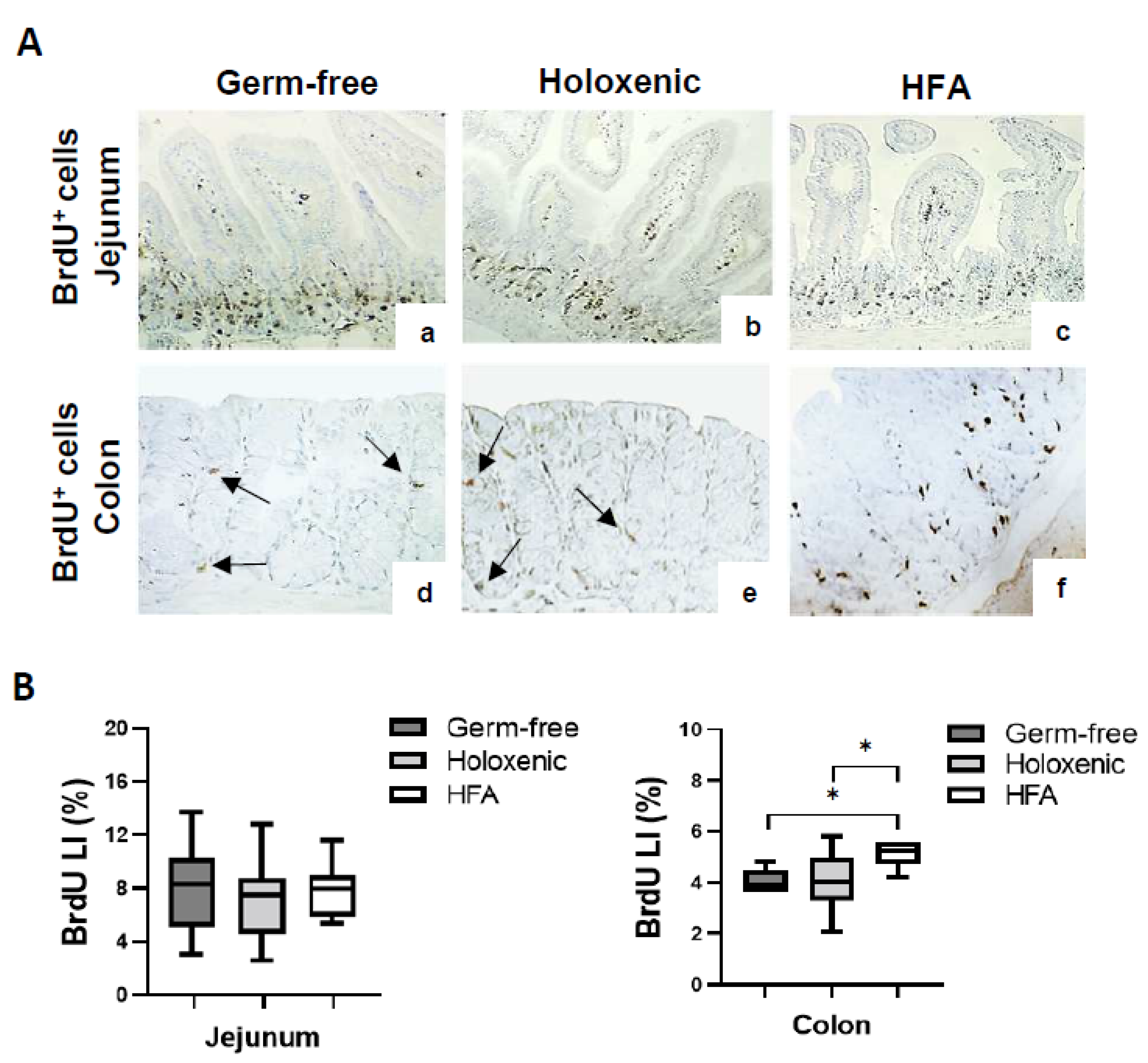

2.1. Intestinal Cell Proliferation in Germ-Free, Holoxenic, and HFA Mice

2.2. Bacteria Distribution along the Intestine of Germ-Free, Holoxenic, and HFA Mice

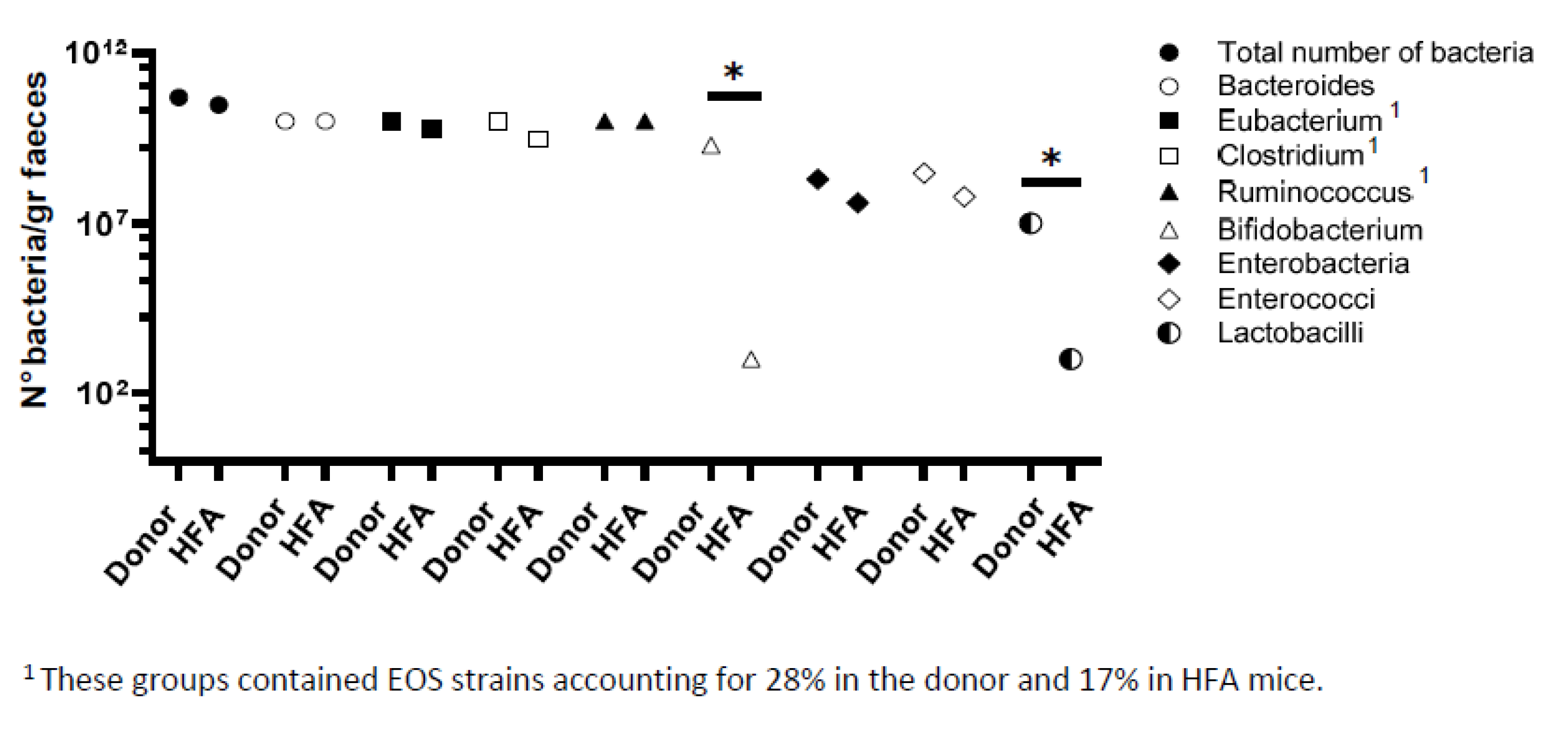

2.3. Bacteriological Analysis of Fecal Flora from Healthy Donor and HFA Mice

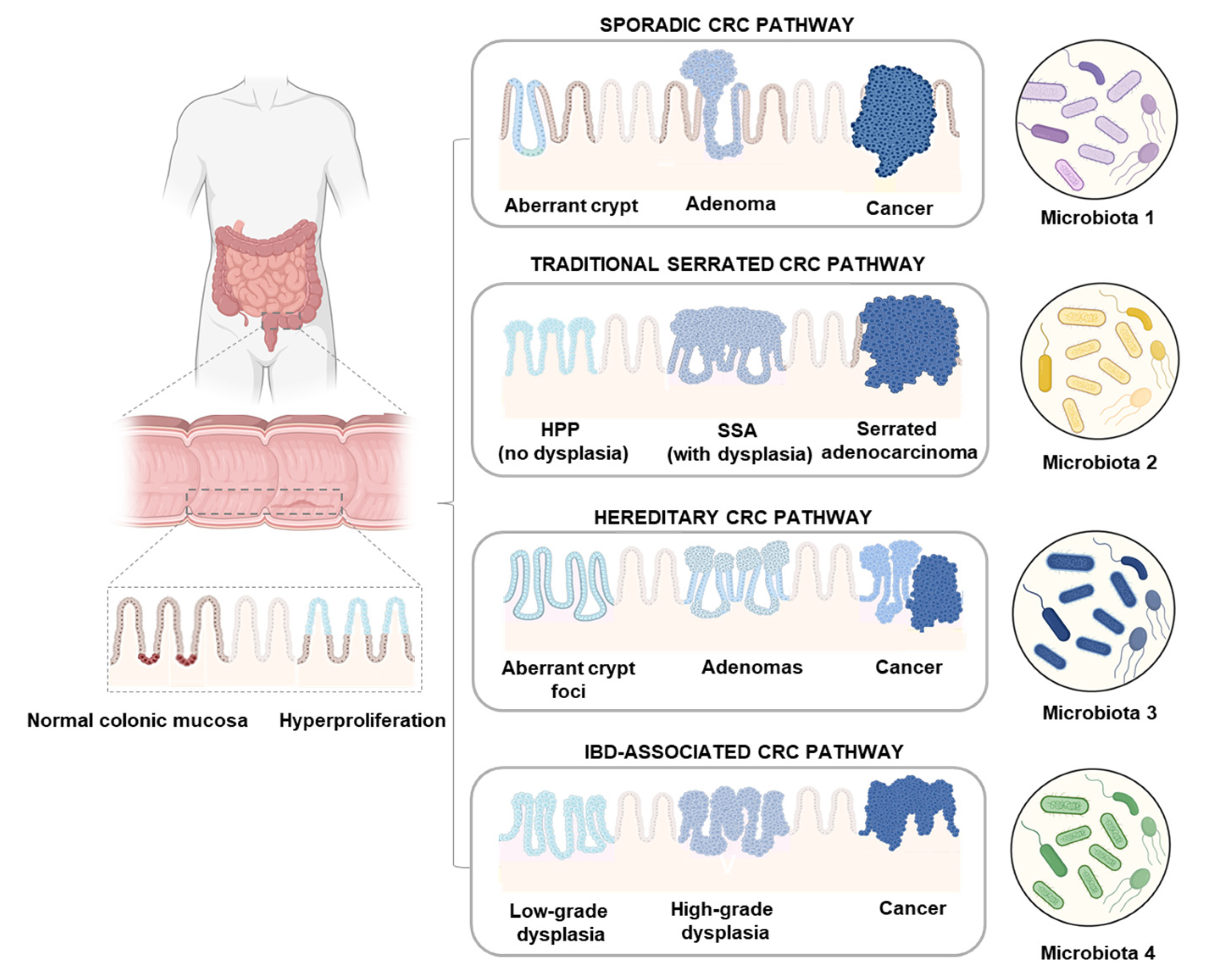

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals

4.2. BrdU Injection

4.3. BrdU Immunohistochemistry

4.4. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

4.5. Bacteriological Analysis

4.6. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vermeulen, L.; Snippert, H.J. Stem cell dynamics in homeostasis and cancer of the intestine. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 468–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanini, S.; Marzotto, M.; Giovinazzo, F.; Bassi, C.; Bellavite, P. Effects of dietary components on cancer of the diges-tive system. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015, 55, 1870–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahrami, H.; Tafrihi, M.; Mohamadzadeh, S. Reversing the Warburg effect to control cancer: A review of di-et-based solutions. J. Curr. Oncol. Med. Sci. 2022, 2, 234–248. [Google Scholar]

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Beltrán-Velasco, A.I.; Redondo-Flórez, L.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. Global Impacts of Western Diet and Its Effects on Metabolism and Health: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donaldson, G.P.; Lee, S.M.; Mazmanian, S.K. Gut biogeography of the bacterial microbiota. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd-Price, J.; Mahurkar, A.; Rahnavard, G.; Crabtree, J.; Orvis, J.; Hall, A.B.; Brady, A.; Creasy, H.H.; McCracken, C.; Giglio, M.G.; et al. Strains, functions and dynamics in the expanded Human Microbiome Project. Nature 2017, 550, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turnbaugh, P.J.; Ridaura, V.K.; Faith, J.J.; Rey, F.E.; Knight, R.; Gordon, J.I. The effect of diet on the human gut micro-biome: A metagenomic analysis in humanized gnotobiotic mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 2009, 1, 6ra14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, L.A.; Maurice, C.F.; Carmody, R.N.; Gootenberg, D.B.; Button, J.E.; Wolfe, B.E.; Ling, A.V.; Devlin, A.S.; Varma, Y.; Fischbach, M.A.; et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut micro-biome. Nature 2014, 505, 559–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jandhyala, S.M.; Talukdar, R.; Subramanyam, C.; Vuyyuru, H.; Sasikala, M.; Nageshwar Reddy, D. Role of the normal gut microbiota. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 8787–8803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchesi, J.R.; Adams, D.H.; Fava, F.; Hermes, G.D.; Hirschfield, G.M.; Hold, G.; Quraishi, M.N.; Kinross, J.; Smidt, H.; Tuohy, K.M.; et al. The gut microbiota and host health: A new clinical frontier. Gut 2016, 65, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.T.; Sears, C.L. The microbial landscape of colorectal cancer. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 240–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, S.H.; Yu, J. Gut microbiota in colorectal cancer: Mechanisms of action and clinical applications. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 690–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzaal, M.; Saeed, F.; Shah, Y.A.; Hussain, M.; Rabail, R.; Socol, C.T.; Hassoun, A.; Pateiro, M.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Rusu, A.V.; et al. Human gut microbiota in health and disease: Unveiling the relationship. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 999001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirayama, K.; Itoh, K. Human flora-associated (HFA) animals as a model for studying the role of intestinal flora in human health and disease. Curr. Issues Intest. Microbiol. 2005, 6, 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Lesher, S.; Walburg, H.E., Jr.; Sacher, G.A., Jr. Generation cycle in the duodenal crypt cells of germ-free and conventional mice. Nature 1964, 202, 884–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherbuy, C.; Honvo-Houeto, E.; Bruneau, A.; Bridonneau, C.; Mayeur, C.; Duée, P.H.; Langella, P.; Thomas, M. Microbiota matures colonic epithelium through a coordinated induction of cell cycle-related proteins in gnotobiotic rat. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2010, 299, G348–G357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaboriau-Routhiau, V.; Rakotobe, S.; Lecuyer, E.; Mulder, I.; Lan, A.; Bridonneau, C.; Rochet, V.; Pisi, A.; De Paepe, M.; Brandi, G.; et al. The key role of segmented filamentous bacteria in the coordi-nated maturation of gut helper T cell responses. Immunity 2009, 31, 677–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deschner, E.E. Early proliferative changes in gastrointestinal neoplasia. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1982, 77, 207–211. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.; Chen, H.; Shu, X.; Yin, Y.; Li, J.; Qin, J.; Chen, L.; Peng, K.; Xu, F.; Gu, W.; et al. Presence of Segmented Filamentous Bacteria in Human Children and Its Potential Role in the Modulation of Human Gut Immunity. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagier, J.C.; Million, M.; Hugon, P.; Armougom, F.; Raoult, D. Human gut microbiota: Repertoire and variations. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2012, 2, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagier, J.C.; Armougom, F.; Million, M.; Hugon, P.; Pagnier, I.; Robert, C.; Bittar, F.; Fournous, G.; Gimenez, G.; Maraninchi, M.J.; et al. Microbial culturomics: Paradigm shift in the human gut microbiome study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, 1185–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terpstra, O.T.; van Blankenstein, M.; Dees, J.; Eilers, G.A. Abnormal pattern of cell proliferation in the entire colonic mucosa of patients with colon adenoma or cancer. Gastroenterology 1987, 92, 704–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patchett, S.E.; Alstead, E.M.; Saunders, B.P.; Hodgson, S.V.; Farthing, M.J. Regional proliferative patterns in the colon of patients at risk for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Dis. Colon Rectum 1997, 40, 168–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinozaki, M.; Watanabe, T.; Kubota, Y.; Sawada, T.; Nagawa, H.; Muto, T. High proliferative activity is associated with dysplasia in ulcerative colitis. Dis. Colon Rectum 2000, 43, S34–S39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Hu, X.; Xiao, Y.; Yang, C.; Ding, Y.; Hou, N.; Wang, J.; Cheng, H.; Zhang, X. Overnutrition stimulates intestinal epithelium proliferation through β-catenin signaling in obese mice. Diabetes 2013, 62, 3736–3746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagio, M.; Shimizu, H.; Joe, G.H.; Takatsuki, M.; Shiwaku, M.; Xu, H.; Lee, J.Y.; Fujii, N.; Fukiya, S.; Hara, H.; et al. Diet supplementation with cholic acid promotes intestinal epithelial proliferation in rats exposed to γ-radiation. Toxicol. Lett. 2015, 232, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiratori, H.; Hattori, K.M.; Nakata, K.; Okawa, T.; Komiyama, S.; Kinashi, Y.; Kabumoto, Y.; Kaneko, Y.; Nagai, M.; Shindo, T.; et al. A purified diet affects intestinal epithelial proliferation and barrier functions through gut microbial alterations. Int. Immunol. 2024, 36, 223–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vannucci, L.; Stepankova, R.; Kozakova, H.; Fiserova, A.; Rossmann, P.; Tlaskalova-Hogenova, H. Colorectal carcinogenesis in germ-free and conventionally reared rats: Different intestinal environments affect the systemic immunity. Int. J. Oncol. 2008, 32, 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakatsu, G.; Li, X.; Zhou, H.; Sheng, J.; Wong, S.H.; Wu, W.K.; Ng, S.C.; Tsoi, H.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, N.; et al. Gut mucosal microbiome across stages of colorectal carcinogenesis. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Fan, H.; Tang, X.; Zhai, H.; Zhang, Z. Diversified pattern of the human colorectal cancer microbiome. Gut Pathog. 2013, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, F.; Nookaew, I.; Sommer, N.; Fogelstrand, P.; Bäckhed, F. Site-specific programming of the host epithelial transcriptome by the gut micro-biota. Genome Biol. 2015, 16, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Ashida, H.; Ogawa, M.; Yoshikawa, Y.; Mimuro, H.; Sasakawa, C. Bacterial interactions with the host epithelium. Cell Host Microbe 2010, 8, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raibaud, P.; Dickinson, A.B.; Sacquet, E.; Charlier, H.; Mocquot, G. Microflora of the digestive system of the rat. I. Technics of study and proposed culture media. Ann. Inst. Pasteur 1966, 110, 568–590. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, C.C.; Yu, J. Gut microbiota in colorectal cancer development and therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 20, 429–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvi, P.S.; Cowles, R.A. Butyrate and the Intestinal Epithelium: Modulation of Proliferation and Inflammation in Homeostasis and Disease. Cells 2021, 10, 1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Aidy, S.; Van Baarlen, P.; Derrien, M.; Lindenbergh-Kortleve, D.J.; Hooiveld, G.; Levenez, F.; Doré, J.; Dekker, J.; Samsom, J.N.; Nieuwenhuis, E.E.; et al. Temporal and spatial interplay of microbiota and intestinal mucosa drive establishment of immune homeostasis in conventionalized mice. Mucosal Immunol. 2012, 5, 567–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raibaud, P.; Ducluzeau, R.; Dubos, F.; Hudault, S.; Bewa, H.; Muller, M.C. Implantation of bacteria from the digestive tract of man and various animals into gnotobiotic mice. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1980, 33 (Suppl. 11), 2440–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandi, G.; Pisi, A.M.; Biasco, G. Ultrastructure et Micro-Écologie du Canal Alimentaire; Edra Medical Publishing & New Media: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 1–113. [Google Scholar]

- Lepercq, P.; Gérard, P.; Béguet, F.; Raibaud, P.; Grill, J.P.; Relano, P.; Cayuela, C.; Juste, C. Epimerization of chenodeoxycholic acid to ursodeoxycholic acid by Clostridium baratii isolated from human feces. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2004, 235, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Germ-Free | Holoxenic | HFA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jejunum | Colon | Jejunum | Colon | Jejunum | Colon | |

| Crypts analysed | 70 ± 3.2 | 76 ± 3.7 | 70 ± 3.5 | 65 ± 2.9 | 73 ± 3.6 | 63 ± 2.7 |

| Cells per crypt | 28 ± 0.9 | 25 ± 0.3 | 28 ± 0.6 | 30 ± 1.1 | 29 ± 0.7 | 32 ± 0.5 |

| Total n° cells | 1940 ± 142 | 1910 ± 130 | 1955 ± 196 | 1861 ± 135 | 2109 ± 191 | 2010 ± 130 |

| BrdU+ cells | 165 ± 66.4 | 58.8 ± 26.3 | 155 ± 75.4 | 68.7 ± 20.1 | 184 ± 58.9 | 109 ± 31.5 |

| Labelling index (%) | 8.36 ± 2.82 | 3.74 ± 1.32 | 7.71 ± 3.23 | 4.29 ± 1.11 | 8.29 ± 2.07 | 5.94 ± 1.26 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brandi, G.; Calabrese, C.; Tavolari, S.; Bridonneau, C.; Raibaud, P.; Liguori, G.; Thomas, M.; Di Battista, M.; Gaboriau-Routhiau, V.; Langella, P. Intestinal Microbiota Increases Cell Proliferation of Colonic Mucosa in Human-Flora-Associated (HFA) Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6182. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25116182

Brandi G, Calabrese C, Tavolari S, Bridonneau C, Raibaud P, Liguori G, Thomas M, Di Battista M, Gaboriau-Routhiau V, Langella P. Intestinal Microbiota Increases Cell Proliferation of Colonic Mucosa in Human-Flora-Associated (HFA) Mice. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2024; 25(11):6182. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25116182

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrandi, Giovanni, Carlo Calabrese, Simona Tavolari, Chantal Bridonneau, Pierre Raibaud, Giuseppina Liguori, Muriel Thomas, Monica Di Battista, Valerie Gaboriau-Routhiau, and Philippe Langella. 2024. "Intestinal Microbiota Increases Cell Proliferation of Colonic Mucosa in Human-Flora-Associated (HFA) Mice" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 25, no. 11: 6182. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25116182

APA StyleBrandi, G., Calabrese, C., Tavolari, S., Bridonneau, C., Raibaud, P., Liguori, G., Thomas, M., Di Battista, M., Gaboriau-Routhiau, V., & Langella, P. (2024). Intestinal Microbiota Increases Cell Proliferation of Colonic Mucosa in Human-Flora-Associated (HFA) Mice. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25(11), 6182. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25116182