SCGB1C1 Plays a Critical Role in Suppression of Allergic Airway Inflammation through the Induction of Regulatory T Cell Expansion

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

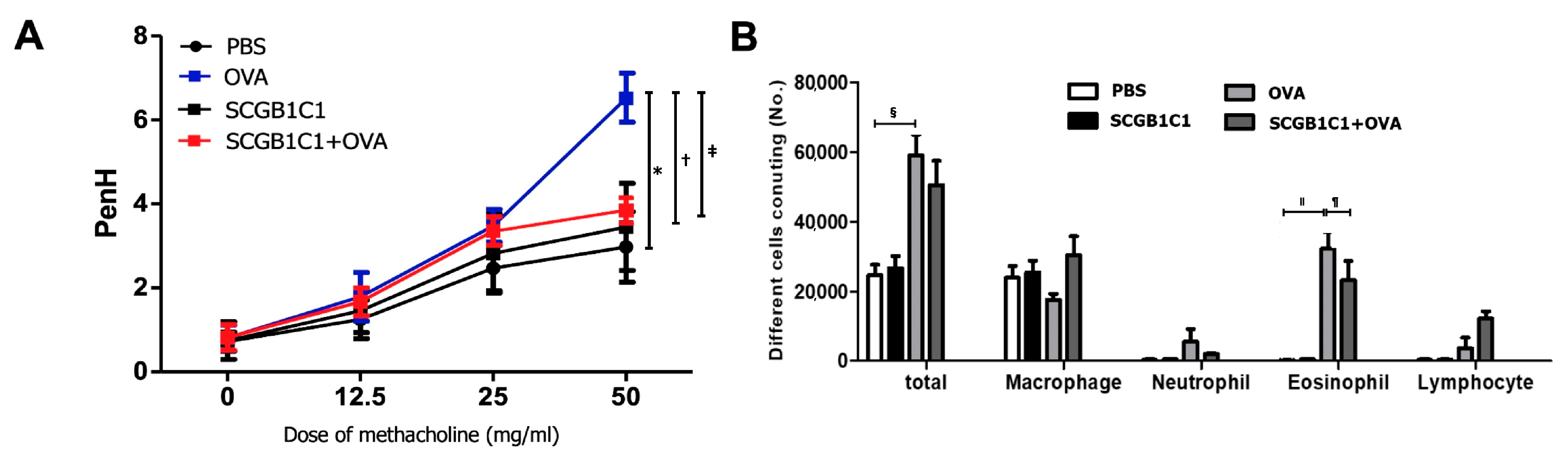

2.1. AHR and Inflammatory Cells in BALF

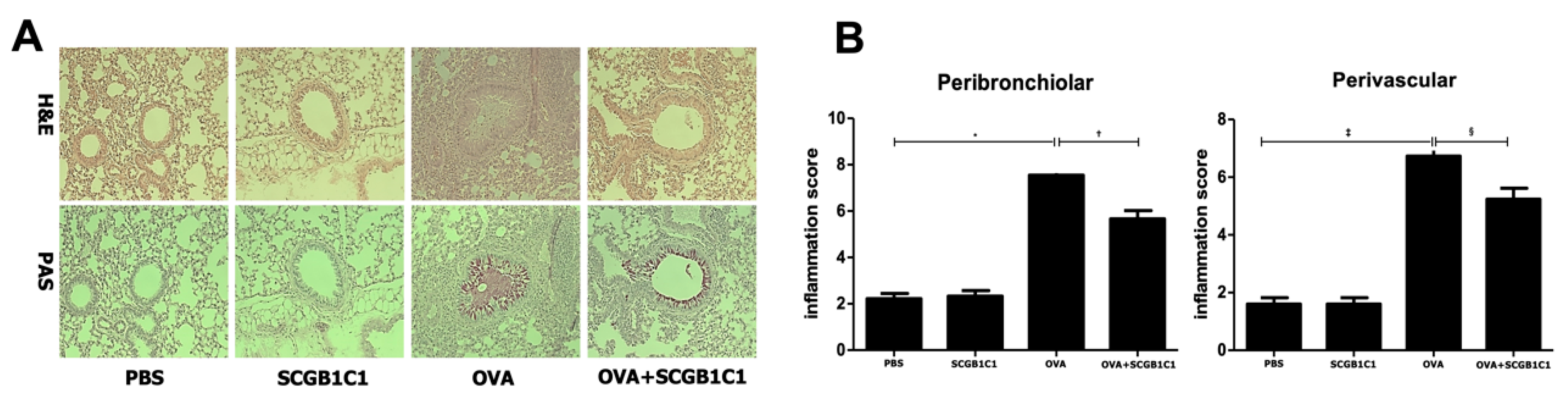

2.2. Lung Histology and Inflammation Score

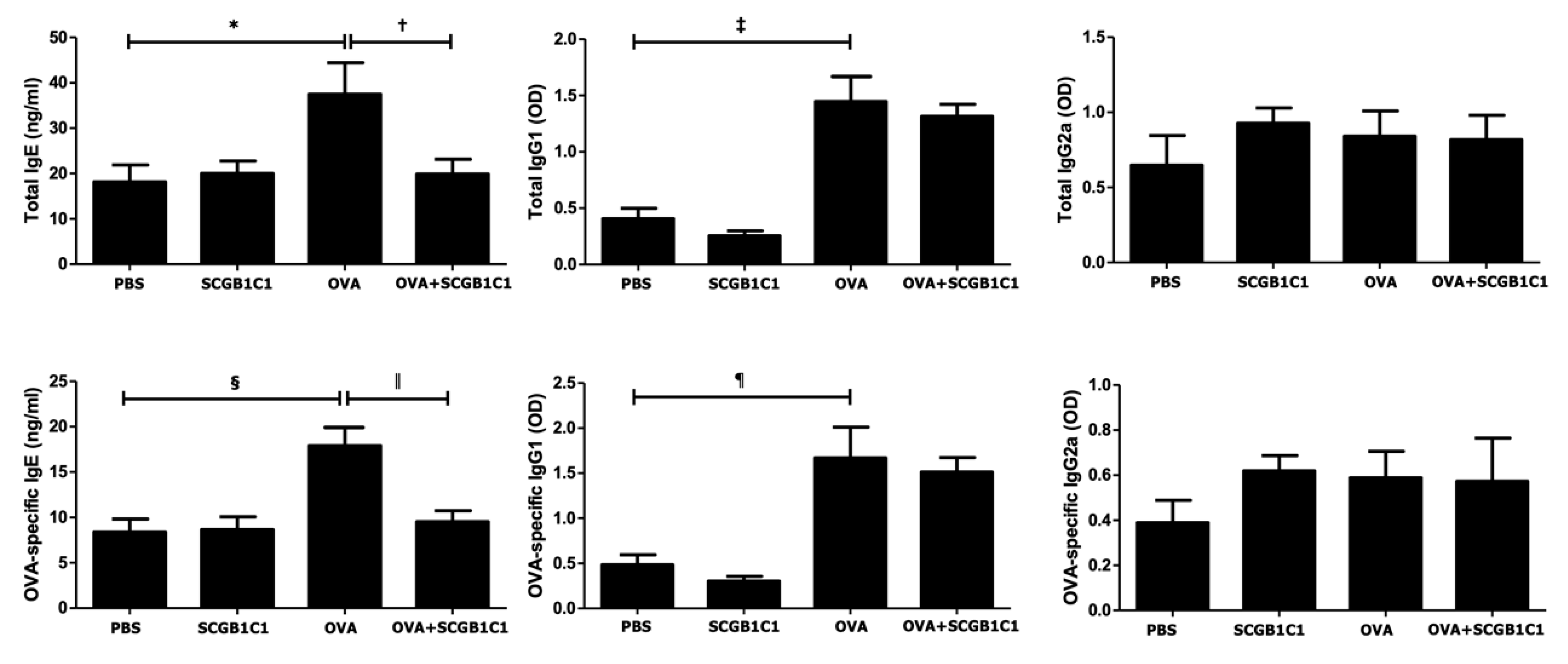

2.3. Serum Total and OVA-Specific IgE, IgG1, and IgG2a Levels

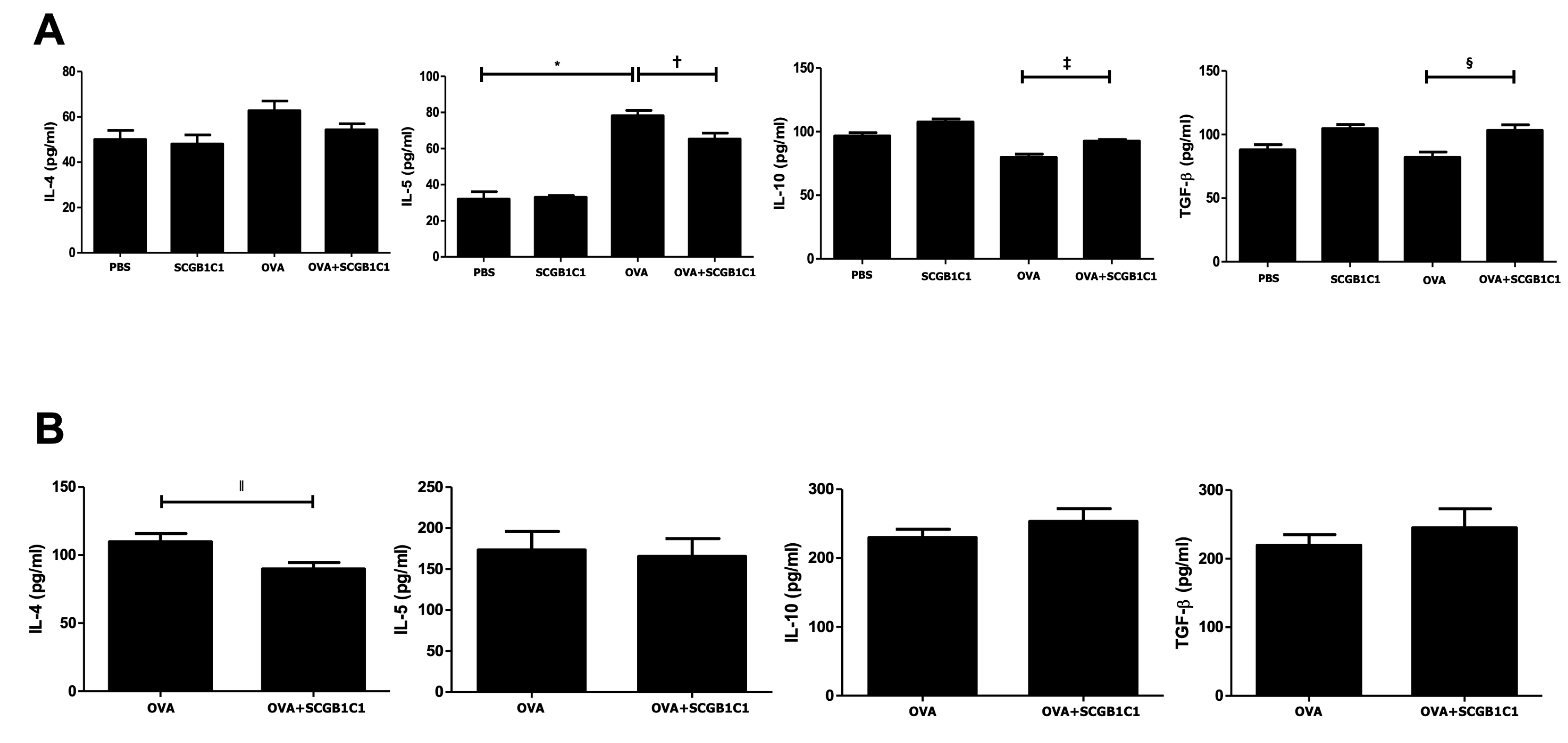

2.4. Expression of Cytokines in the BALF and LLNs

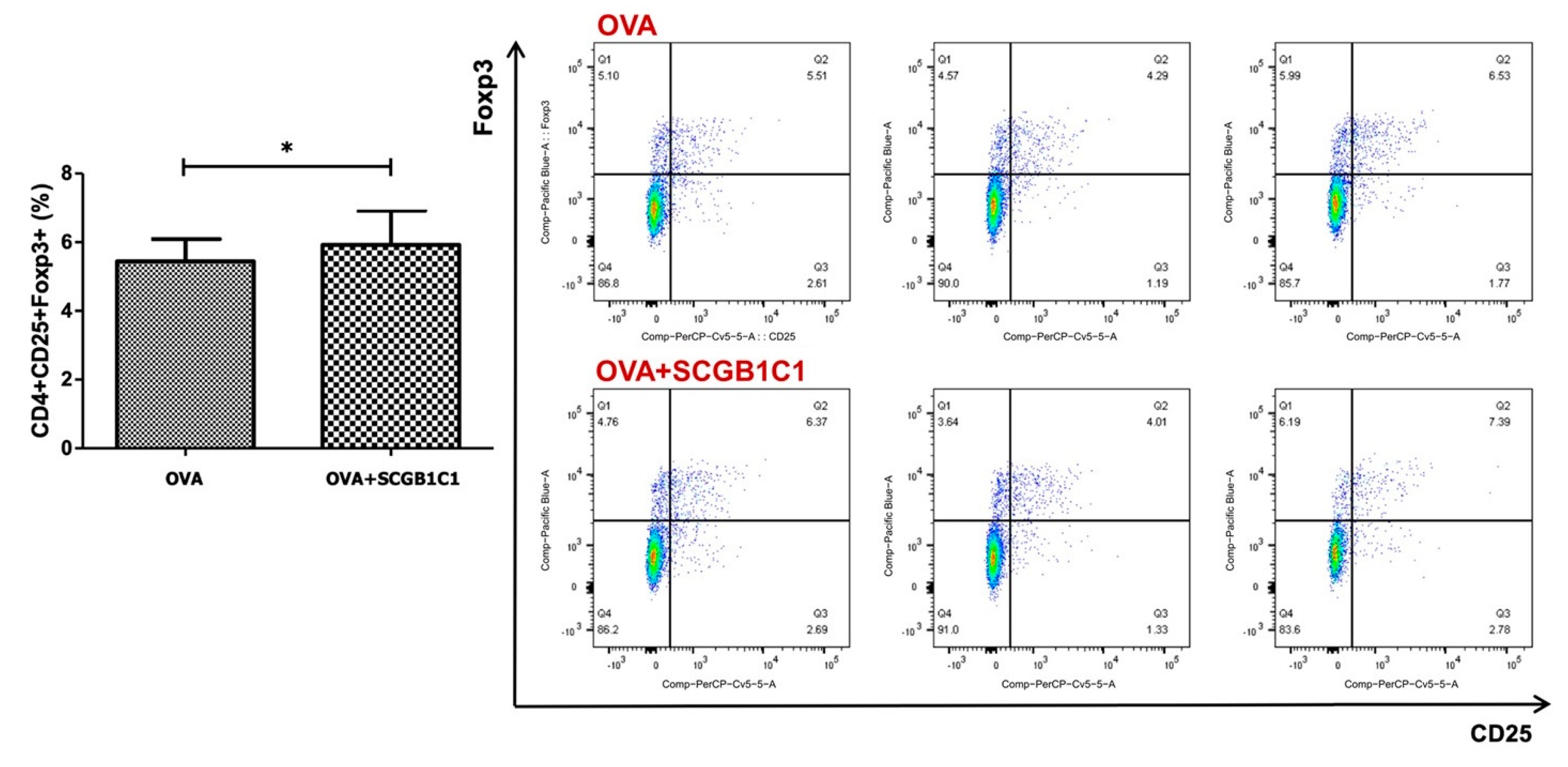

2.5. T Cell Population in the LLNs

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals

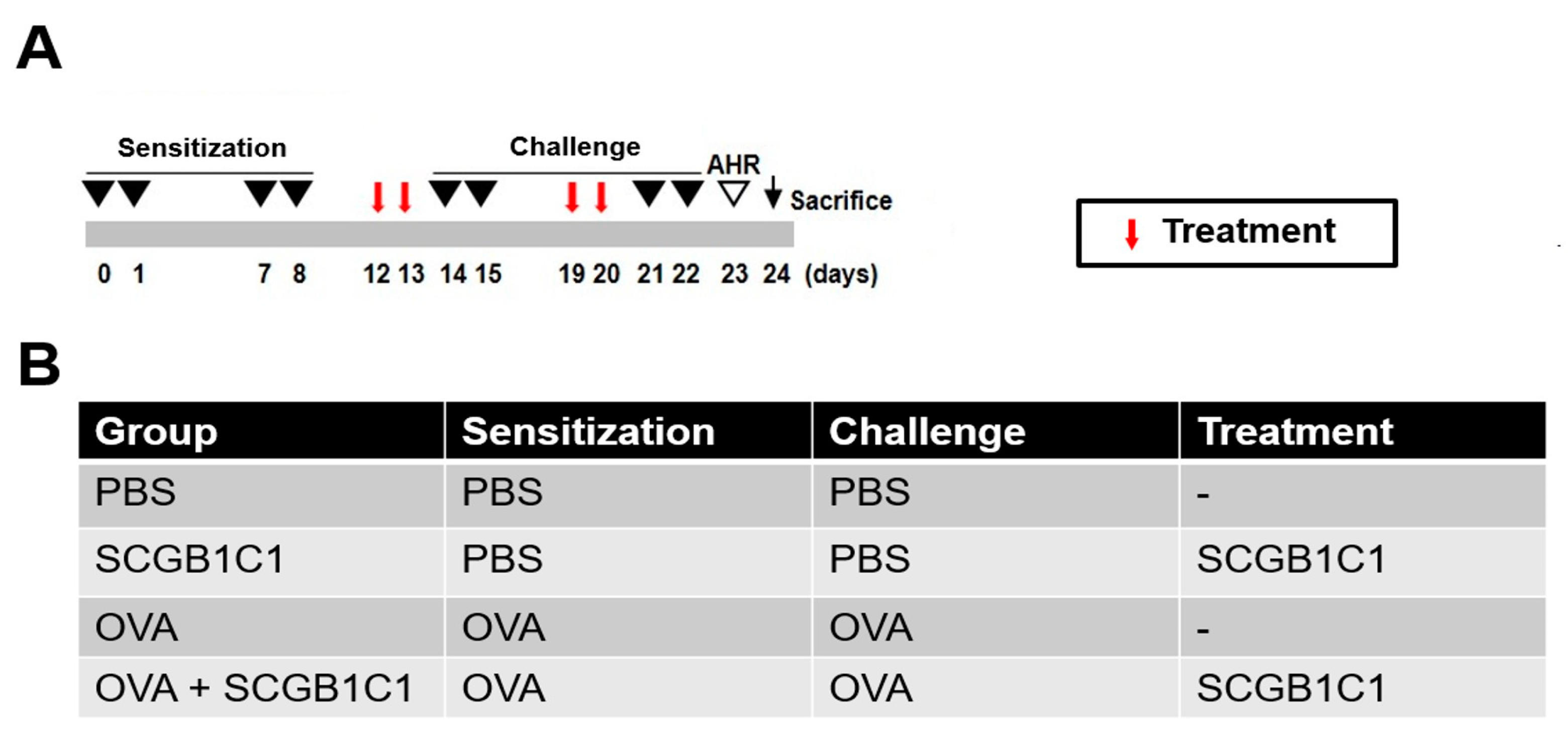

4.2. Mouse Model of Allergic Airway Inflammation

4.3. Intranasal Administration of SCGB1C1

4.4. Measurement of Airway AHR

4.5. Differential Cell Counting in Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid (BALF)

4.6. Lung Histology and Inflammation Scoring

4.7. Measurement of Serum Immunoglobulin

4.8. Expression of Cytokines in the Lung-Draining Lymph Nodes and BALF

4.9. Phenotypic Analysis of CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ Tregs

4.10. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Lee, H.Y.; Kim, I.K.; Yoon, H.K.; Kwon, S.S.; Rhee, C.K.; Lee, S.Y. Inhibitory effects of resveratrol on airway remodeling by transforming growth factor-beta/smad signaling pathway in chronic asthma model. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2017, 9, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, M.S.; Taylor, M.D.; Balic, A.; Finney, C.A.; Lamb, J.R.; Maizels, R.M. Suppression of allergic airway inflammation by helminth-induced regulatory T cells. J. Exp. Med. 2005, 202, 1199–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.Z.; Qin, X.J. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T lymphocytes in allergy and asthma. Allergy 2005, 60, 986–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaffar, Z.; Sivakuru, T.; Roberts, K. CD4+CD25+ T cells regulate airway eosinophilic inflammation by modulating the Th2 cell phenotype. J. Immunol. 2004, 172, 3842–3849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L. Increasing Prevalence of Allergic Rhinitis in China. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2019, 11, 156–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.K.; Cho, K.S.; Park, H.Y.; Shin, D.H.; Kim, Y.K.; Jung, J.S.; Park, S.K.; Roh, H.J. Adipose-derived stromal cells inhibit allergic airway inflammation in mice. Stem Cells Dev. 2010, 19, 1811–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uccelli, A.; Moretta, L.; Pistoia, V. Immunoregulatory function of mesenchymal stem cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 2006, 36, 2566–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonfield, T.L.; Koloze, M.; Lennon, D.P.; Zuchowski, B.; Yang, S.E.; Caplan, A.I. Human mesenchymal stem cells suppress chronic airway inflammation in the murine ovalbumin asthma model. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2010, 299, L760–L770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, M.; Sueblinvong, V.; Eisenhauer, P.; Ziats, N.P.; LeClair, L.; Poynter, M.E.; Steele, C.; Rincon, M.; Weiss, D.J. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells inhibit Th2-mediated allergic airways inflammation in mice. Stem Cells 2011, 29, 1137–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, F.F.; Borg, Z.D.; Goodwin, M.; Sokocevic, D.; Wagner, D.E.; Coffey, A.; Antunes, M.; Robinson, K.L.; Mitsialis, S.A.; Kourembanas, S.; et al. Systemic administration of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cell extracellular vesicles ameliorates Aspergillus Hyphal extract-induced allergic airway inflammation in immunocompetent mice. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2015, 4, 1302–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Cho, H.S.; Yang, S.H.; Shin, J.Y.; Kim, J.S.; Lee, S.T.; Chu, K.; Roh, J.K.; Kim, S.U.; Park, C.G. Soluble mediators from human neural stem cells play a critical role in suppression of T-cell activation and proliferation. J. Neurosci. Res. 2009, 87, 2264–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.S.; Park, M.K.; Kang, S.A.; Cho, K.S.; Mun, S.J.; Roh, H.J. Culture supernatant of adipose stem cells can ameliorate allergic airway inflammation via recruitment of CD4+CD25+Foxp3 T cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2017, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Lee, Y.T.; Hong, J.M.; Hwang, Y.I. Suppression of in vitro murine T cell proliferation by human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells is dependent mainly on cyclooxygenase-2 expression. Anat. Cell Biol. 2013, 46, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ionescu, L.I.; Alphonse, R.S.; Arizmendi, N.; Morgan, B.; Abel, M.; Eaton, F.; Duszyk, M.; Vliagoftis, H.; Aprahamian, T.R.; Walsh, K.; et al. Airway delivery of soluble factors from plastic-adherent bone marrow cells prevents murine asthma. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2012, 46, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mun, S.J.; Kang, S.A.; Park, H.K.; Yu, H.S.; Cho, K.S.; Roh, H.J. Intranasally administered extracellular vesicles from adipose stem cells have immunomodulatory effects in a mouse model of asthma. Stem Cells Int. 2021, 2021, 6686625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.S.; Ban, M.; Choi, E.J.; Moon, H.G.; Jeon, J.S.; Kim, D.K.; Park, S.K.; Jeon, S.G.; Roh, T.Y.; Myung, S.J.; et al. Extracellular vesicles derived from gut microbiota, especially Akkermansia muciniphila, protect the progression of dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e76520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, J.; Ludlow, J.W. Exosomes for repair, regeneration and rejuvenation. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2016, 16, 489–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.S.; Kang, S.A.; Kim, S.D.; Mun, S.J.; Yu, H.S.; Roh, H.J. Dendritic cells and M2 macrophage play an important role in suppression of Th2-mediated inflammation by adipose stem cells-derived extracellular vesicles. Stem Cell Res. 2019, 39, 101500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.D.; Kang, S.A.; Kim, Y.W.; Yu, H.S.; Cho, K.S.; Roh, H.J. Screening and functional pathway analysis of pulmonary genes associated with suppression of allergic airway inflammation by adipose stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles. Stem Cell Int. 2020, 2020, 5684250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolye, L.M.; Wang, M.Z. Overview of extracellualr vesicles, their origin, composition, purpose, and methods for exosome isolation and analysis. Cells 2019, 8, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Liu, X.; Shi, Y.; Ocansey, D.K.W.; Hu, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, C.; Xu, W.; Qian, H. Therapeutic advances of stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles in regenrative medicine. Cells 2020, 9, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Y.M.; Zhuansun, Y.X.; Chen, R.; Lin, L.; Lin, Y.; Li, J.G. Mesenchymal stem cell exosomes promote immunosuppression of regulatory T cells in asthma. Exp. Cell Res. 2018, 363, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valadi, H.; Ekström, K.; Bossios, A.; Sjöstrand, M.; Lee, J.J.; Lötvall, J.O. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007, 9, 654–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.D.; Cho, K.S. Immunomodulatory effects of mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles in allergic airway disease. Life 2022, 12, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostecka, Y.; Blahovec, J. Insulin-like growth factor binding proteins and their functions (minireview). Endocr. Regul. 1999, 33, 90–94. [Google Scholar]

- Vaillancourt, V.T.; Bordeleau, M.; Laviolette, M.; Laprise, C. From expression pattern to genetic association in asthma and asthma-related phenotypes. BMC Res. Notes 2012, 5, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orysiak, J.; Malczewska-Lenczowska, J.; Bik-Multanowski, M. Expression of SCGB1C1 gene as a potential marker of susceptibility to upper respiratory tract infections in elite athletes-a pilot study. Biol. Sport 2016, 33, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, B.C.; Thompson, D.C.; Wright, M.W.; McAndrews, M.; Bernard, A.; Nevert, D.W.; Vasiliou, V. Update of the human secretoglobin (SCGB) gene superfamily and an example of “evolutionary bloom” of androgen-binding protein genes within the mouse Scgb gene superfamily. Hum. Genom. 2011, 5, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Lu, X.; Yu, H.J.; Hua, X.Y.; Cui, Y.H.; Huang, S.K.; Liu, Z. The expression of osteopontin and its association with Clara cell 10 kDa protein in allergic rhinitis. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2010, 40, 1632–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthou, G.; Alissafi, T.; Semitekolou, M.; Simoes, D.C.; Economidou, E.; Gaga, M.; Lambrecht, B.N.; Lloyd, C.M.; Panoutsakopoulou, V. Osteopontin has a crucial role in allergic airway disease through regulation of dendritic cell subsets. Nat. Med. 2007, 13, 570–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdas, S.; Oadas, T. Differentially expressed Secretoglobin 1C1 gene in nasal polyposis. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2018, 64, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, K.S.; Park, M.K.; Kang, S.A.; Park, H.Y.; Hong, S.L.; Park, H.K.; Yu, H.S.; Roh, H.J. Adipose-derived stem cells ameliorate allergic airway inflammation by inducing regulatory T cells in a mouse model of asthma. Mediat. Inflamm. 2014, 2014, 436476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, K.S.; Lee, J.H.; Park, M.K.; Park, H.K.; Yu, H.S.; Roh, H.J. Prostaglandin E2 and Transforming Growth Factor-β Play a Critical Role in Suppression of Allergic Airway Inflammation by Adipose-Derived Stem Cells. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0131813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, S.-D.; Kang, S.-A.; Mun, S.-J.; Yu, H.-S.; Roh, H.-J.; Cho, K.-S. SCGB1C1 Plays a Critical Role in Suppression of Allergic Airway Inflammation through the Induction of Regulatory T Cell Expansion. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6282. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25116282

Kim S-D, Kang S-A, Mun S-J, Yu H-S, Roh H-J, Cho K-S. SCGB1C1 Plays a Critical Role in Suppression of Allergic Airway Inflammation through the Induction of Regulatory T Cell Expansion. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2024; 25(11):6282. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25116282

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Sung-Dong, Shin-Ae Kang, Sue-Jean Mun, Hak-Sun Yu, Hwan-Jung Roh, and Kyu-Sup Cho. 2024. "SCGB1C1 Plays a Critical Role in Suppression of Allergic Airway Inflammation through the Induction of Regulatory T Cell Expansion" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 25, no. 11: 6282. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25116282

APA StyleKim, S.-D., Kang, S.-A., Mun, S.-J., Yu, H.-S., Roh, H.-J., & Cho, K.-S. (2024). SCGB1C1 Plays a Critical Role in Suppression of Allergic Airway Inflammation through the Induction of Regulatory T Cell Expansion. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25(11), 6282. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25116282