Abstract

Plant AT-rich sequence and zinc-binding proteins (PLATZs) are a novel category of plant-specific transcription factors involved in growth, development, and abiotic stress responses. However, the PLATZ gene family has not been identified in barley. In this study, a total of 11 HvPLATZs were identified in barley, and they were unevenly distributed on five of the seven chromosomes. The phylogenetic tree, incorporating PLATZs from Arabidopsis, rice, maize, wheat, and barley, could be classified into six clusters, in which HvPLATZs are absent in Cluster VI. HvPLATZs exhibited conserved motif arrangements with a characteristic PLATZ domain. Two segmental duplication events were observed among HvPLATZs. All HvPLATZs were core genes present in 20 genotypes of the barley pan-genome. The HvPLATZ5 coding sequences were conserved among 20 barley genotypes, whereas HvPLATZ4/9/10 exhibited synonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs); the remaining ones showed nonsynonymous variations. The expression of HvPLATZ2/3/8 was ubiquitous in various tissues, whereas HvPLATZ7 appeared transcriptionally silent; the remaining genes displayed tissue-specific expression. The expression of HvPLATZs was modulated by salt stress, potassium deficiency, and osmotic stress, with response patterns being time-, tissue-, and stress type-dependent. The heterologous expression of HvPLATZ3/5/6/8/9/10/11 in yeast enhanced tolerance to salt and osmotic stress, whereas the expression of HvPLATZ2 compromised tolerance. These results advance our comprehension and facilitate further functional characterization of HvPLATZs.

1. Introduction

Transcription factors play critical roles in plant growth, development, and responses to external stimuli by activating or repressing target gene expression. Some transcription factors are ubiquitous in all eukaryotic organisms, while others are plant specific. In Arabidopsis, over 1500 transcription factors are encoded by >5% of its genome, with approximately 45% being plant specific [1].

PLATZs are plant-specific transcription factors and contain two conserved domains: C-x2-H-x11-C-x2-C-x(4–5)-C-x2-C-x(3–7)-H-x2-H and C-x2-C-x(10–11)-C-x3-C, and both are essential for zinc-dependent DNA binding. The first PLATZ gene was cloned from pea (Pisum sativum) in 2001 and was responsible for transcriptional repression mediated by an A/T-rich sequence [2]. Subsequently, more PLATZ genes were cloned and functionally identified in multiple plant species.

PLATZs regulate plant growth and development. AtPLATZ1 (ABA-INDUCED expression 1, AIN1) affects abscisic acid (ABA)-inhibited elongation of the primary root by regulating reactive oxygen species (ROS) homeostasis [3]. AtPLATZ3 (ORESARA15, ORE15) has been demonstrated to promote leaf growth by enhancing the rate and duration of cell proliferation during the early stage and restrains leaf senescence by regulating the GRF/GIF pathway during the later stage [4]. AtPLATZ3 also regulates the size of the root apical meristem through the antagonistic interplay between auxin and cytokinin signaling-related pathways [5]. In rice, GL6 positively regulates grain length by facilitating cell proliferation in developing panicles and grains [6]. Rice knockout lines of OsFl3 exhibited a decrease in thousand-kernel weight and grain size [7]. SG6 (SHORT GRAIN6) was also found to determine rice grain size through the division control of spikelet hull cells [8]. The interaction of maize ZmPLATZ12 (fl3) with RPC53 and TFC1, which are crucial elements of the RNA polymerase III transcription complex, affects endosperm development and storage reserve filling [9,10]. TaPLATZ-A1 in wheat is predominantly expressed in elongating stems and developing spikes and exhibits significant genetic interactions with the dwarfing gene RHT1 on plant height regulation [11]. The GmPLATZ gene binds to the promoters of cyclin genes and GmGA20OX, activating their expression for cell proliferation and therefore modulating seed size and weight [12]. The transcriptional repressor RhPLATZ9 plays a crucial role in regulating senescence in rose flowers, and the RhWRKY33a-RhPLATZ9-RhRbohD regulatory module functions as a protective mechanism to maintain petal ROS homeostasis, counteracting premature senescence induced by aging and stress [13]. PtaPLATZ18 has been evidenced to play a pivotal role in the regulation of growth and vascular tissue development in poplar [14].

PLATZs also play pivotal functions in plant abiotic stress responses. In Arabidopsis, AtPLATZ1 and AtPLATZ2 contribute to seed desiccation tolerance, and constitutive expression of AtPLATZ1 confers partial desiccation tolerance on transgenic plants [15]. AtPLATZ4 enhances drought tolerance by adjusting the expression of PIP2;8 and ABA signaling-related genes [16]. However, AtPLATZ2, functioning redundantly with AtPLATZ7, compromises the salt tolerance of seedlings by directly inhibiting CBL4/SOS3 and CBL10/SCaBP8 genes [17]. GmPLATZ17 suppresses the transcription of GmDREB5, thereby impairing soybean drought tolerance [18]. GmPLATZ1 is induced by drought, salinity, and ABA, and overexpression of GmPLATZ1 in Arabidopsis delays germination under osmotic stress [19]. Overexpression of cotton GhPLATZ1 in Arabidopsis improves tolerance to osmotic and salt stress during the germination and seedling stages [20]. Overexpression of PhePLATZ1 in Arabidopsis enhances drought tolerance through osmotic regulation, improvement in water retention capacity, and mitigation of membrane and oxidative damage [21]. SiPLATZ12 suppresses the expression of SiNHX, SiCBL, and SiSOS genes, resulting in impaired salt tolerance in foxtail millet [22]. GhiPLATZ17 and GhiPLATZ22 have been demonstrated to improve the salt tolerance of upland cotton [23]. Overexpression of PtPLATZ3 maintains chlorophyll content stability and membrane integrity and induces the expression of genes associated with cadmium tolerance and accumulation, substantially enhancing cadmium tolerance and accumulation [24]. Additionally, transcriptome analyses have revealed the involvement of PLATZs in plant response to drought [25], heat [26], and hormones [27] across diverse plant species.

The PLATZ family has been identified in multiple plant species, including Arabidopsis tahliana, rice, maize [10], Brassica rapa [28], wheat [29], alfalfa [30], and buckwheat [31]. However, gene family identification has not been reported in barley. In this study, 11 HvPLATZs were identified in barley, and systemic in silico analyses were conducted. The response patterns of HvPLATZs to abiotic stresses in barley roots and leaves were examined, and their functions in salt and osmotic stress tolerance were characterized in yeast. These findings provide a foundation for further functional characterization of HvPLATZs.

2. Results

2.1. Identification of PLATZ Genes in Barley

In total, 11 HvPLATZ genes were identified in barley (Table 1). The protein lengths of HvPLATZs varied from 212 aas to 272 aas, with 1–3 introns. Their isoelectric points (pI) were 7.15–9.44 and theoretical MW was 22.74–29.21 kDa (Table 1). The instability indices ranged from 48.06 (HvPLATZ9) to 71.76 (HvPLATZ1), all >40, suggesting that these proteins are relatively unstable [32]. HvPLATZs were localized in the nucleus, except HvPLATZ4, which was localized in the extracellular space (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of 11 HvPLATZs.

2.2. Phylogeny and Gene Structure Analysis of HvPLATZs

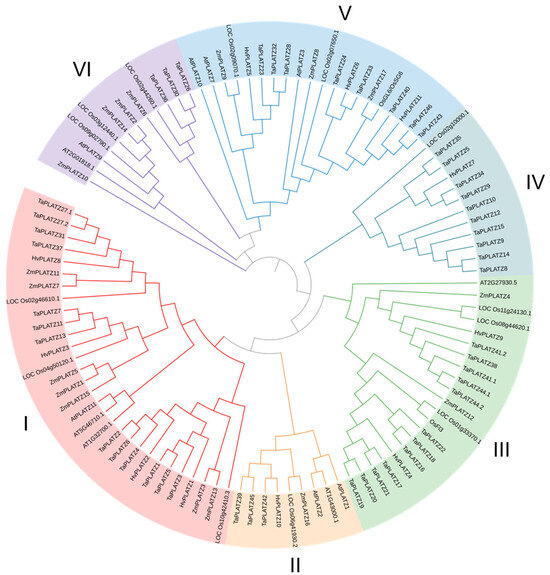

The protein sequences of 12 PLATZs in Arabidopsis, 15 PLATZs in rice, 17 ZmPLATZs in maize, 49 TaPLATZs in wheat, and 11 HvPLATZs in barley were used for phylogeny analysis (Figure 1). These 104 PLATZs were classified into six clusters based on phylogenetic relationships. Cluster I had 30 members, followed by Cluster III and V, containing 21 and 20 members, respectively. Cluster IV and VI each contained 12 members, and only 9 members were classified in Cluster II. Clusters I to V contained four, one, two, one, and three HvPLATZs, respectively. Notably, no HvPLATZ was classified into Cluster VI in this phylogenetic tree; neither AtPLATZ nor ZmPLATZ was classified into Cluster IV.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree of PLATZ family proteins from Arabidopsis, rice, maize, and barley. At: Arabidopsis thaliana; Os: Oryza sativa; Zm: Zea mays; Hv: Hordeum vulgare.

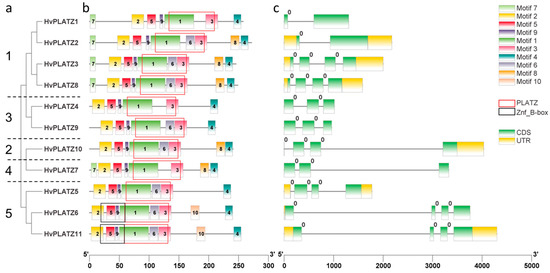

HvPLATZs in the same cluster displayed similar motif arrangements (Figure 2). HvPLATZ6 and HvPLATZ11, which possessed a B-box-type zinc finger domain (IPR000315, Znf_B-box), were in Cluster V and showed the same motif arrangements. According to the position between or within codons, introns are classified into three phases: phase 0, phase 1, and phase 2. Introns of phase 0 are located between two codons, whereas introns of phase 1 and phase 2 are located after the first position and after the second position in a codon, respectively [33]. Introns existed in all HvPLATZ genes, and intriguingly, all introns belonged to phase 0.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic relationship and sequence characteristics of HvPLATZs. (a) Phylogenetic tree of HvPLATZs, the HvPLATZs from Cluster I–V were designated as numbers 1–5, respectively; (b) conserved motifs of HvPLATZs; (c) gene structures of HvPLATZs.

2.3. Chromosomal Distribution and Duplication of HvPLATZs

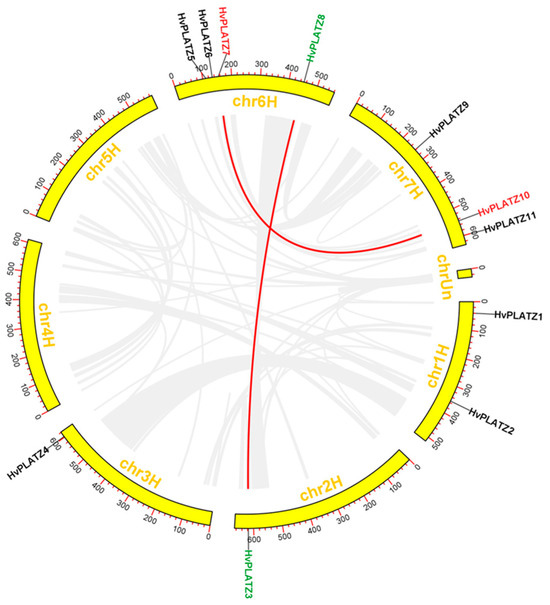

The distribution of 11 HvPLATZs was uneven across five out of seven chromosomes, with four genes on chromosome 6, three genes on chromosome 7, two genes on chromosome 1, and one gene each on chromosomes 2 and 3 (Figure 3). No HvPLATZ genes were found on chromosomes 4 and 5.

Figure 3.

Chromosomal distribution and segmental duplication of HvPLATZs. Segmentally duplicated genes were displayed in the same color and linked with red lines.

Gene duplication is recognized as the major driving force behind gene family expansion during evolution [34]. The HvPLATZ gene family did not exhibit tandem duplication events. In total, two pairs of HvPLATZ genes were segmentally duplicated (HvPLATZ3 and HvPLATZ8; HvPLATZ7 and HvPLATZ10; Figure 3).

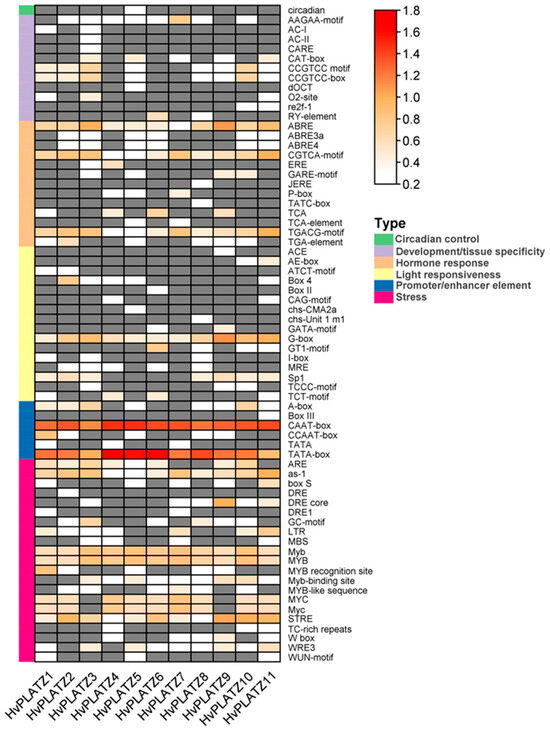

2.4. Cis-Acting Elements Identification

Sixty-eight cis-acting elements were identified and could be sorted into six functional types (Figure 4; File S1). Approximately one-third (21, 30.9%) of the elements were classified as “stress” responsive, followed by those involved in “light responsiveness” (16, 23.5%), “hormone response” (13, 23.5%), “development/tissue specificity” (11, 16.2%), and “promoter/enhancer element” (6, 8.8%). Only one type of element was observed in the “circadian control” category (Figure 4). In the “promoter/enhancer element” category, CAAT-box and TATA-box, which are binding sites of RNA polymerase and contribute to transcription efficiency, were present in all HvPLATZ promoters, suggesting their important roles in regulating HvPLATZs transcription. In the “hormone response” category, ABRE is involved in ABA responsiveness, while the CGTCA-motif and TGACG-motif were related to methyl jasmonate responsiveness, all of which widely existed in HvPLATZ promoters (Figure 4). In the “light responsiveness” category, G-box was also extensively present in promoters of HvPLATZs (Figure 4). Moreover, stress-responsive motifs, such as as-1, Myb, MYB, and STRE, were ubiquitously detected in all HvPLATZs. However, other cis-acting elements were relatively gene-specific and low-abundance. Therefore, HvPLATZs likely play crucial roles in hormone and stress responses but might vary in their response patterns and expression profiles.

Figure 4.

Cis-acting elements in promoters of HvPLATZs. Cis-acting elements were predicted following the 2-kb sequences upstream of the coding sequences of HvPLATZs. The quantity of cis-acting elements was normalized by log10(number + 1) and then used for visualization. Absent elements were displayed in grey color.

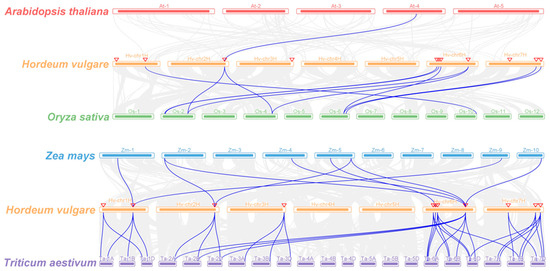

2.5. Syntenic Analysis of HvPLATZs

The synteny of PLATZs between barley and other plant species was analyzed (Figure 5; File S2). Among these comparisons, HvPLATZ3 and AtPLATZ11 were the only pair of orthologs detected between barley and Arabidopsis. The comparison between barley and rice revealed the presence of ten pairs of orthologous genes, comprising eight HvPLATZs in barley and seven corresponding genes in rice. HvPLATZ3 and HvPLATZ8 exhibited orthology to two PLATZ genes in rice (LOC_Os02g46610 and LOC_Os04g50120), while HvPLATZ7 and HvPLATZ10 were orthologous to LOC_Os06g41930. The comparison between maize and barley revealed the presence of nine pairs of orthologous genes, including seven ZmPLATZs and four HvPLATZs. HvPLATZ2 and HvPLATZ3 were identified as orthologs of two ZmPLATZ genes, namely ZmPLATZ3/13 and ZmPLATZ5/11, respectively. Notably, HvPLATZ8 was orthologous to four ZmPLATZs (ZmPLATZ5/7/11/15). The evolutionary proximity between barley and wheat resulted in the detection of substantially more orthologous gene pairs (34 pairs, including all HvPLATZs and 30 TaPLATZs) between these two species than those between rice and maize (Figure 5; File S2). HvPLATZ8 was orthologous to six TaPLATZs, followed by HvPLATZ7/11 and HvPLATZ2/3/4/5/10, which were orthologous to four and three TaPLATZs, respectively. HvPLATZ1/9 and HvPLATZ6 were orthologous to two and one TaPLATZ, respectively.

Figure 5.

Synteny analyses of PLATZs between barley and four plant species (Arabidopsis thaliana, Oryza sativa, Zea mays, and Triticum aestivum). Gray lines indicated collinear blocks and blue lines highlighted syntenic PLATZs gene pairs. Inverted triangles indicated the chromosomal positions of HvPLATZs.

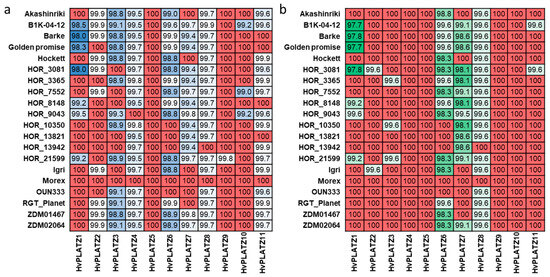

2.6. Natural Variation of HvPLATZs in Barley

A pan-genome refers to the diversity within a species in terms of genome content and structure [35]. Natural variation of genes in a pan-genome context includes not only genic presence/absence variation (PAV), but also base-level SNPs [36,37]. To investigate the natural variation of HvPLATZs, PAV and SNP were examined on the basis of the first generation of the barley pan-genome (Figure 6; Files S5 and S6) [36]. Notably, the coding sequences of HvPLATZ5 and HvPLATZ10 in assemblies of 17 genotypes featured CAT as start codons instead of the typical ATG (File S3). However, in de novo assemblies, the start codon was the typical ATG (File S3). Therefore, the discrepancy was probably attributable to the assembly process, and the subsequent analyses were conducted using sequences in which the initial codon CAT was replaced with the typical start codon ATG (File S4). The pan-genome can be classified into two categories: the core genome and the dispensable genome. The former consists of genes that are universally present across all genotypes, whereas the latter consists of genes that are absent in certain genotypes [35,38]. The 11 HvPLATZs were all a part of the core genome, accordingly (Figure 6). The nucleotide and protein sequences of HvPLATZs were identical in two to eight and five to ten genotypes, respectively, when compared with the reference cultivar Morex. Furthermore, the coding and protein sequence identity of HvPLATZs between Morex and other barley genotypes ranged from 98.0% to 100% and from 97.7% to 100%, respectively. The coding sequence of HvPLATZ5 was identical among all 20 genotypes, followed by HvPLATZ9 and HvPLATZ10, which shared identity among 19 and 17 genotypes, respectively. The coding sequences of HvPLATZ4 and HvPLATZ8 in eighteen genotypes exhibited SNPs compared with Morex. However, the SNPs in HvPLATZ4 were synonymous, whereas those in HvPLATZ8 were nonsynonymous. In addition to HvPLATZ5, the protein sequences of HvPLATZ4, HvPLATZ9, and HvPLATZ10 were identical across all 20 genotypes. Moreover, the wild barley genotype, B1K-04-12, exhibited the most HvPLATZs with SNPs compared with Morex. HOR_3081 possessed the most HvPLATZ members, with amino acid sequences distinct from those of Morex.

Figure 6.

Nucleotide (a) and amino acid (b) sequence identity of HvPLATZs among barley genotypes. Sequences of HvPLATZs in Morex were used as Blast queries, and the percent identity was designated in grids. Red color indicated absolute identity, and the darker of blue and green, the higher of nucleotide and amino acid identity, respectively.

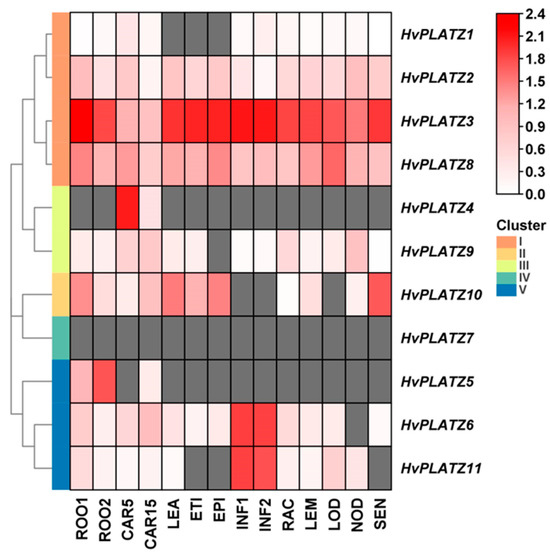

2.7. Tissue-Specific Expression of HvPLATZs

The tissue expression patterns of HvPLATZs were further analyzed (Figure 7; File S5). HvPLATZ2/3/8 in Cluster I expressed ubiquitously across all 14 tissues and stages, with exceptionally high levels for HvPLATZ3, suggesting critical involvement in growth and regulation. However, the expression of HvPLATZ7 from Cluster IV was not detected in any tested tissues, implying that these genes may be redundant or silent. The expression of the remaining seven HvPLATZs was detected in at least two tissues, exhibiting tissue-specific patterns of expression. Furthermore, HvPLATZ5 was not detected in developing grain at 5 d after pollination but exhibited expression at 15 d after pollination. Therefore, the expression of HvPLATZs is tissue-specific and developmental stage-dependent.

Figure 7.

Expression profiling of HvPLATZs in 14 tissues following transcriptomic data. FPKM values were normalized using log10(FPKM + 1) transformation. Grids filled with grey color indicated the absence of detectable gene expression. ROO1, roots from seedlings (10 cm shoot stage); ROO2, roots (28 DAP); CAR5, developing grain (5 DAP); CAR15, developing grain (15 DAP); LEA, shoots from seedlings (10 cm shoot stage); ETI, etiolated seedling, dark condition (10 DAP); EPI, epidermal strips (28 DAP); INF1, young developing inflorescences (5 mm); INF2, developing inflorescences (1–1.5 cm); RAC, inflorescences, rachis (35 DAP); LEM, inflorescences, lemma (42 DAP); LOD, inflorescences, lodicule (42 DAP); NOD, developing tillers, 3rd internode (42 DAP); SEN, senescing leaves (56 DAP).

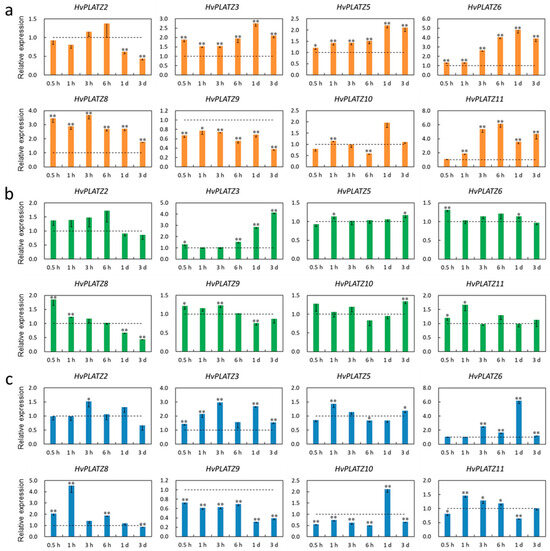

2.8. Transcriptional Responses of HvPLATZs to Abiotic Stresses

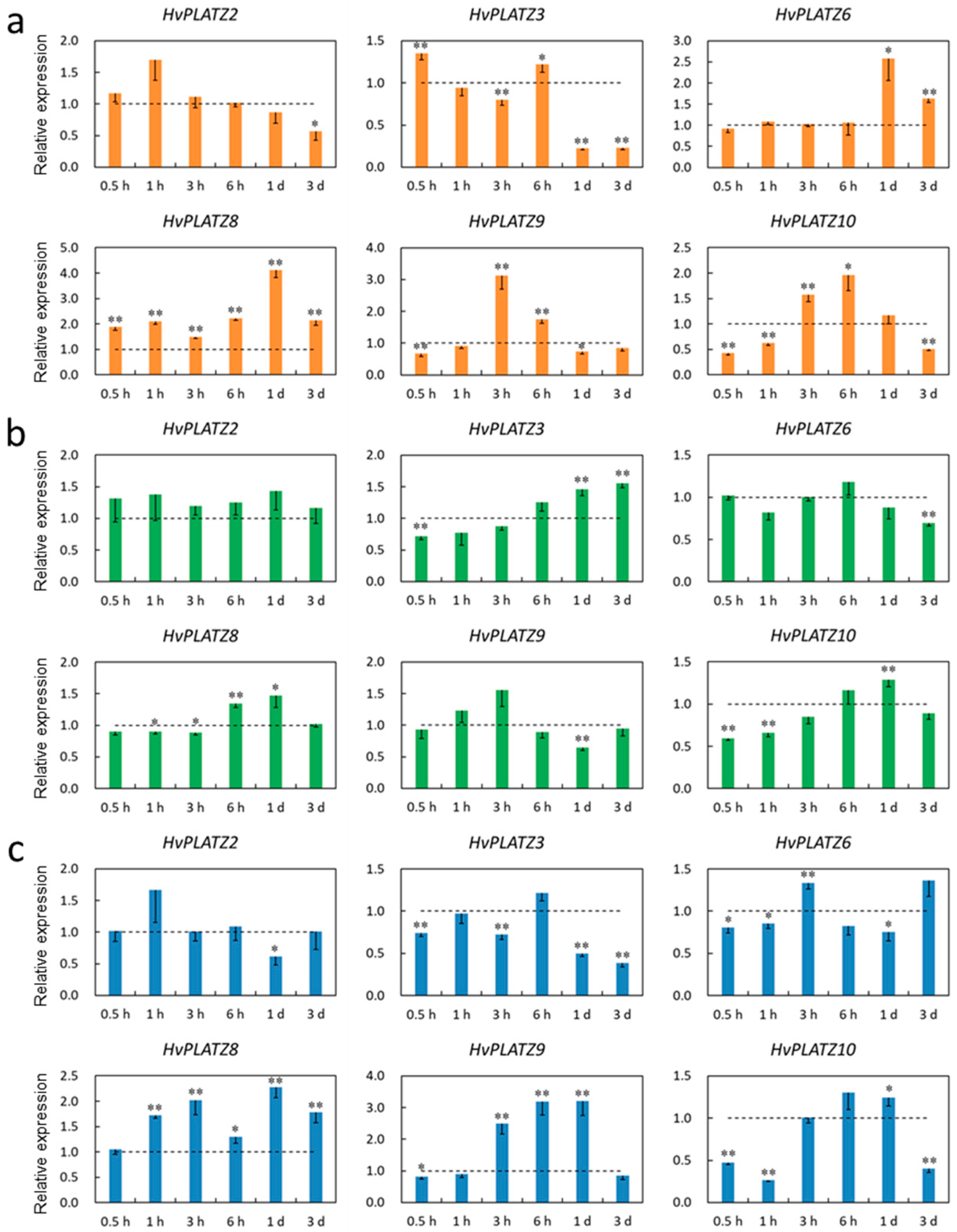

The transcriptional responses of HvPLATZs to salt, potassium deficiency, and osmotic stress treatments were investigated in roots and leaves. The expression of HvPLATZ1/4/7 was not detectable in roots under both control and stress conditions; therefore, only the results of the other eight HvPLATZs were presented (Figure 8). HvPLATZs were significantly induced or suppressed after stress treatments, except for HvPLATZ2 under low-potassium conditions (induced but not significantly). The expression of HvPLATZ3/5/6/8 and HvPLATZ9 was rapidly induced and suppressed, respectively, within 0.5 h of treatment initiation and throughout the entire treatment period. However, the expression of HvPLATZ2/10 exhibited a dynamic pattern, alternating between induction and suppression (Figure 8a). The expression of HvPLATZs was relatively less affected by potassium deficiency compared with salt stress (Figure 8b). Notably, the expression of HvPLATZ3 remained relatively stable after short-term (0.5–3 h) low-potassium treatment but was gradually and significantly induced via long-term (from 6 h to 3 d) treatment. The expression of HvPLATZ8 was rapidly and considerably induced at the initiation of therapy but subsequently declined and became significantly suppressed during the later stage of the treatment (1–3 d). The expression of HvPLATZ3 and HvPLATZ9 was consistently induced and suppressed, respectively, under osmotic stress (Figure 8c). However, the expression of the remaining HvPLATZs fluctuated, alternating between induction and suppression.

Figure 8.

Expression levels of HvPLATZs in barley roots in response to salt stress (a), potassium deficiency (b), and osmotic stress (c) at the seedling stage. Dotted lines indicated the expression levels of HvPLATZs in control seedlings. * and ** indicate significant difference at p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, respectively.

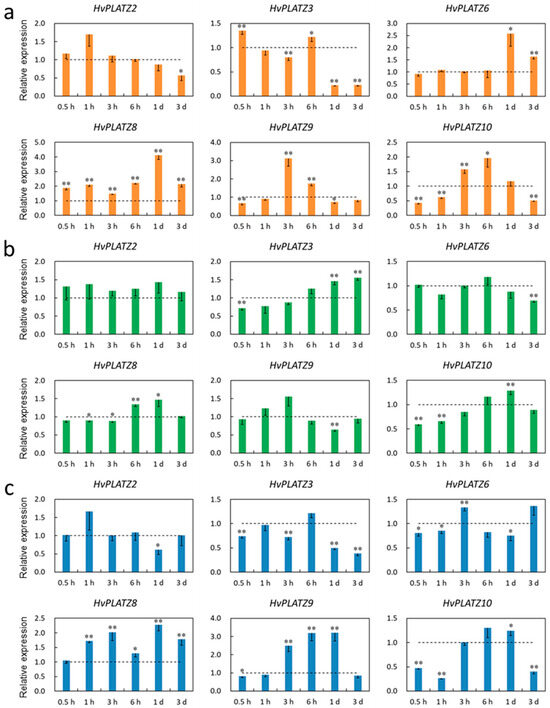

Only six HvPLATZs were detected in leaves via qRT-PCR (Figure 9). Only HvPLATZ8 was significantly induced after salt stress treatment (Figure 9a). The induction of HvPLATZ2 was consistently observed under potassium deficiency conditions, although the induction was not statistically significant (Figure 9b). After osmotic stress treatment for 1 h, the expression of HvPLATZ8 was also significantly upregulated (Figure 9c). The expression of HvPLATZs exhibited pleiotropic and dynamic changes between induction and suppression, excluding the aforementioned cases (Figure 9), suggesting a more intricate regulatory mechanism for abiotic stresses in leaves than that in roots.

Figure 9.

Expression levels of HvPLATZs in barley leaves in response to salt stress (a), potassium deficiency (b), and osmotic stress (c) at the seedling stage. Dotted lines indicated the expression levels of HvPLATZs in control seedlings. * and ** indicate significant difference at p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, respectively.

2.9. Functional Characterization of HvPLATZs in Yeast

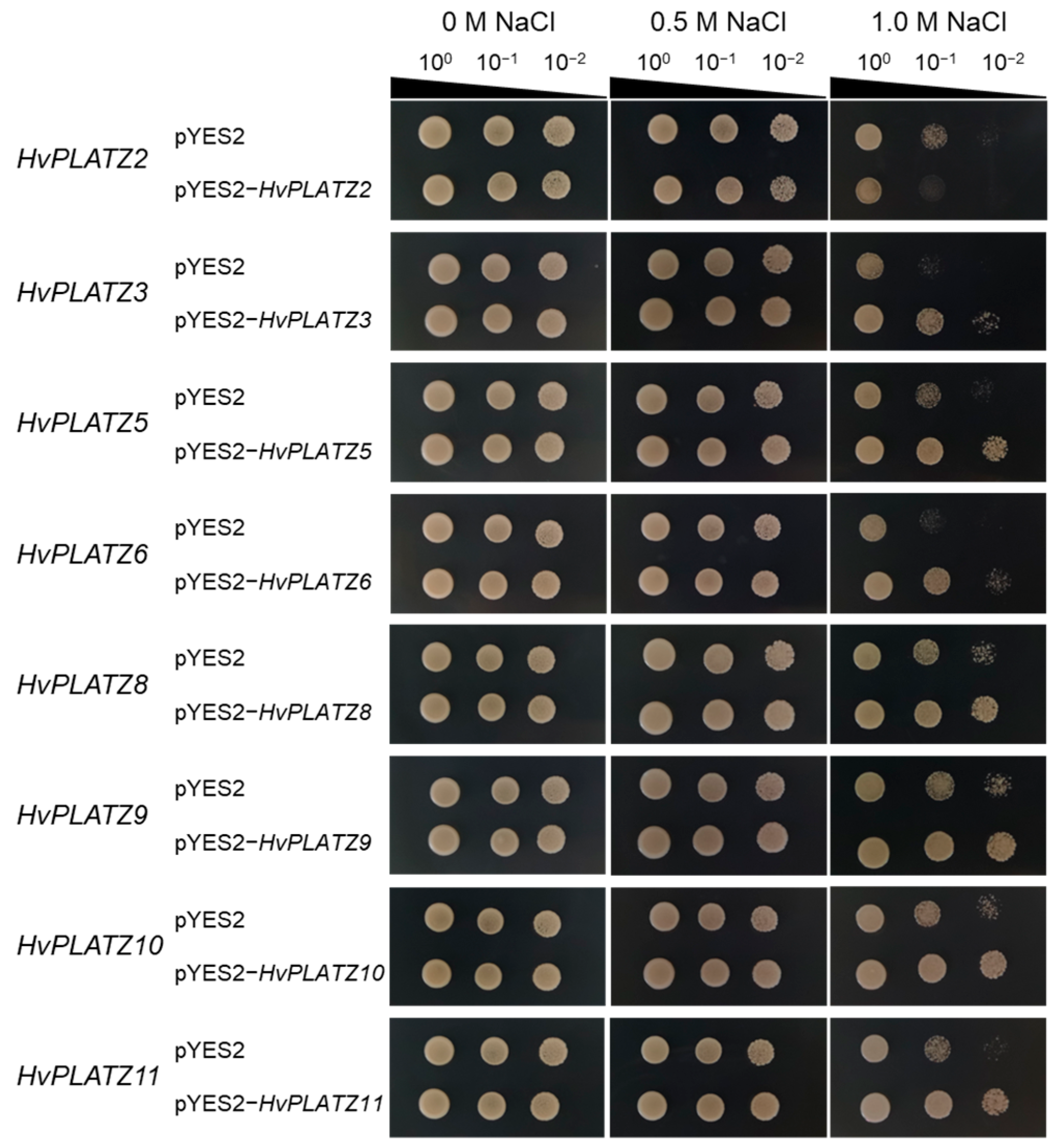

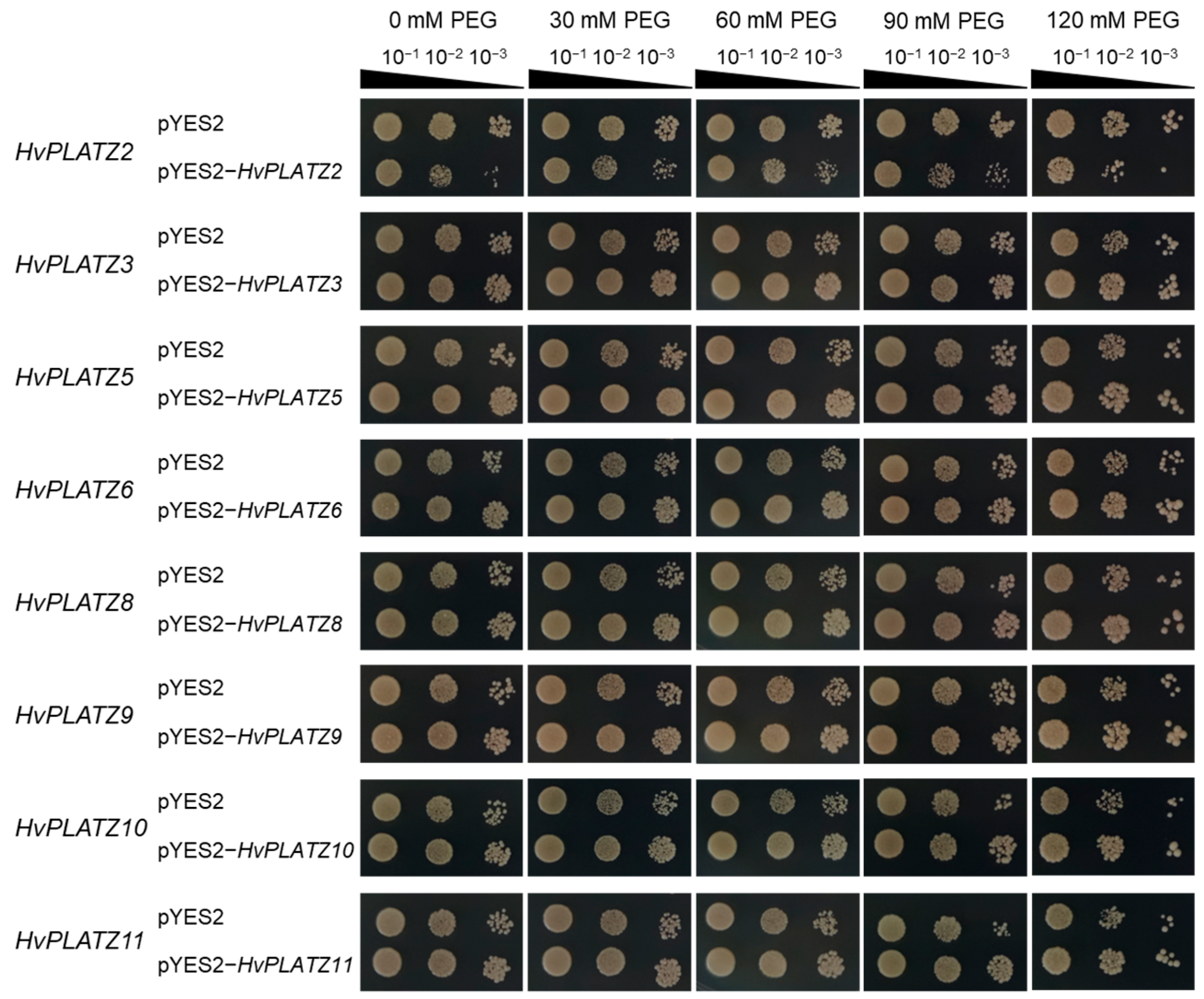

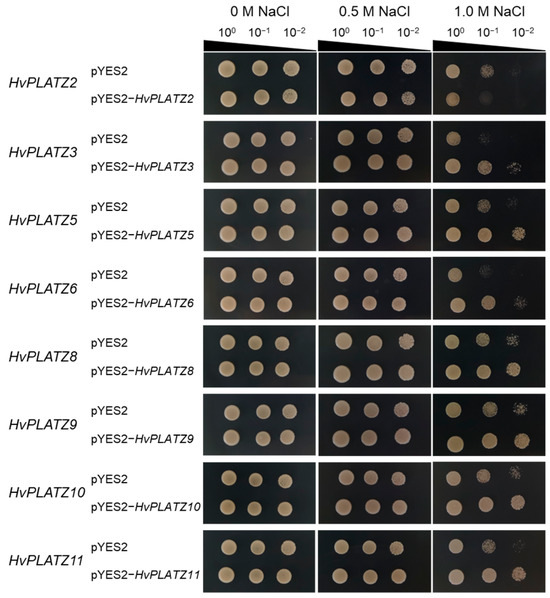

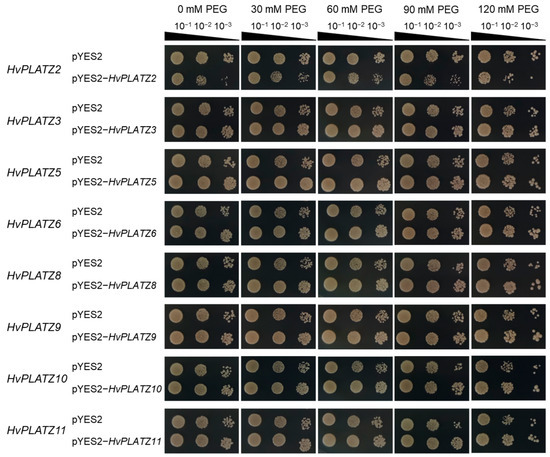

The qRT-PCR results indicated the expression of eight HvPLATZs in barley roots, with diverse responses to abiotic stresses (Figure 8 and Figure 9). To validate their roles in salt and osmotic stress responses, these genes were functionally characterized in yeast (Figure 10 and Figure 11). The yeast strains expressing both empty vector (pYES2) and recombinant vectors (pYES2-HvPLATZs) exhibited robust growth under normal conditions, performing similarly across various dilutions (Figure 10). However, growth differences were observed between strains expressing empty and recombinant vectors as the NaCl concentration in media increased to 1.0 M. The growth of strains expressing HvPLATZ2 was inferior to the control, whereas those expressing HvPLATZ3/5/6/8/9/10/11 exhibited superior growth compared with the control. These results revealed that HvPLATZ2 negatively regulated salt tolerance in yeast, whereas HvPLATZ3/5/6/8/9/10/11 positively regulated salt tolerance. In the osmotic stress tolerance essay, the robustness of strains decreased with increased dilution under control and osmotic stress conditions (Figure 11). Heterologous expression of HvPLATZ2 led to a decrease in osmotic stress tolerance in recombinant yeast strains, whereas the expression of HvPLATZ3/5/6/8/9/10/11 enhanced osmotic stress tolerance, consistent with the results observed in the salt tolerance assay (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Influence of HvPLATZs expression in the INVSC1 yeast strain on salt stress tolerance. HvPLATZs were recombined into pYES2-NTB vectors, and the recombinant vectors were transformed into INVSC1 yeast strain, respectively. The transformed INVSC1 strains were cultured on SD-Ura medium for 2 d. Then PCR-verified single colonies were resuspended in sterile water, serially diluted, and cultured on SG-Ura media with different concentrations of NaCl for 5 d.

Figure 11.

Influence of HvPLATZs expression in the INVSC1 yeast strain on osmotic stress tolerance. HvPLATZs were recombined into pYES2-NTB vectors, and the recombinant vectors were transformed into INVSC1 yeast strain, respectively. The transformed INVSC1 strains were cultured on SD-Ura medium for 2 d. Then PCR-verified single colonies were resuspended in sterile water and shaken cultured on SG-Ura media containing various concentrations of PEG3350 for 3 d. Yeast solutions were serially diluted and cultured on SG-Ura media for 4 d.

3. Discussion

3.1. PLATZ Family in Different Plant Species

TaPLATZ family members were identified as 49 and 62 by He et al. [29] and Fu et al. [39], respectively, with this discrepancy due to the inclusion of 13 additional scaffolds in the latter research. The current analyses involving PLATZs from wheat were based on the 49 TaPLATZs identified by He et al. [29]. Whole-genome duplication or polyploidization, tandem and segmental duplication are primary driving forces for gene family expansion [40]. The PLATZ members in Arabidopsis, rice, maize, and barley were 12, 15, 17, and 11, respectively, despite significant variations in genome sizes ranging from ~135 Mb (Arabidopsis) to ~5.3 Gb (barley). Thus, the number of PLATZ members in these species appeared to be relatively conserved. As an allohexaploid with a genome size of ~17 Gb, the wheat genome contained 49 TaPLATZs, triple the number of PLATZs in rice and maize, implying that polyploidization was the major driving force of PLATZ family expansion at a species level. Wheat shared the closest evolutionary relationship with barley in this study, which was reflected in phylogenetic and syntenic analyses (Figure 1 and Figure 5). The wheat genome exhibited nine tandem duplication events involving 20 TaPLATZs, while the barley genome displayed two segmental duplication events involving four HvPLATZs (Figure 3). These findings suggested that wheat and barley employed distinct strategies in expanding their PLATZ gene families.

HvPLATZ6 and HvPLATZ11 contained an additional Znf_B-box, similar to results reported in PLATZ families from maize [10], Brassica rapa [28], alfalfa [30], and tomato [41]. Deletion of the Znf_B-box led to a significant reduction in the anti-stress activities of MdBBX10 in E. coli, whereas the segment containing the Znf_B-box retained more than half of the activities of MdBBX10, suggesting that the Znf_B-box played a crucial role in stress tolerance [42]. The robust activities of HvPLATZ6/11 in the salt stress response in roots might be partially attributed to the presence of a Znf_B-box (Figure 8).

The peptide length of HvPLATZs ranged from 212 to 272 aas, similar to that of AtPLATZs from Arabidopsis (110–256 aas), OsPLATZs from rice (171–298 aas, except LOC_Os11g24130.1), ZmPLATZs from maize (198–309 aas), and TaPLATZs from wheat (158–275 aas). Although the peptide length of LOC_Os11g24130.1 was merely 80 aas, it possessed an intact PLATZ domain. Notably, the peptide length of MbPLATZ6 and MbPLATZ16 from M. baccata [43], as well as MsPLATZ17 from Medicago sativa [30] was 892 aas, 737 aas, and 629 aas, respectively. The anomalous phenomena might be ascribed to the inaccuracy in genome assembly and annotation, necessitating further analyses for validation. The pI of certain PLATZ members from Arabidopsis, rice, maize [44], and wheat [29] was <7.0. Conversely, all HvPLATZ members from barley exhibited the pI of >7.0 (Table 1), indicating that all HvPLATZs were basic proteins. Similar results were also reported in the PLATZ families of buckwheat [31], watermelon [45], apple [46], Populus trichocarpa [24], and ginkgo [47], with pI higher than 7.0.

3.2. Expression of HvPLATZs in Different Tissues and Response to Abiotic Stresses

The expression of HvPLATZ2/3/8 from Cluster I was detected in all 14 tested tissues (Figure 7), suggesting that HvPLATZ2/3/8 may be housekeeping genes playing pivotal roles in growth and development. HvPLATZ7 appeared to be a silent gene with no detectable expression in any tested tissues or developmental stages (Figure 7). The remaining seven HvPLATZs exhibited tissue-specific and/or developmental stage-dependent expression. Notably, the HvPLATZ gene family in barley exhibited segmental duplication events involving two pairs of HvPLATZs (HvPLATZ3/8 and HvPLATZ7/10, Figure 3). The segmentally duplicated gene pairs were phylogenetically clustered together (Figure 2), and the expression levels of HvPLATZ3 and HvPLATZ8 were comparably high and observed in all tested tissues and stages. However, HvPLATZ10 was detected in 11 tissues and stages, whereas HvPLATZ7 was completely absent in the detected tissues and stages (Figure 7). A similar phenomenon was also observed in poplar with segmentally duplicated PagPLATZs [48]. Additionally, HvPLATZ3 and HvPLATZ8 exhibited identical motif arrangements and introns, both classified into Cluster I. Conversely, HvPLATZ7 and HvPLATZ10 displayed divergent motif arrangements and introns, classified into Cluster IV and Cluster II, respectively (Figure 2). These results suggested that HvPLATZ3 and HvPLATZ8 were relatively conserved in terms of gene sequence, structure, and expression patterns. However, certain mutations might occur in HvPLATZ7 or HvPLATZ10 after segmental duplication, resulting in divergence in expression profiles and functions.

Cis-acting elements were abundantly detected in HvPLATZ promoters, incorporating 13 phytohormone-responsive elements and 21 stress-responsive ones (Figure 4; File S1). Cis-acting elements relevant to ABA and methyl jasmonate responsiveness, such as ABRE, CGTCA-motif, and TGACG-motif, as well as stress response-related elements like as-1, Myb, MYB, and STRE [49], were ubiquitously present in promoters of HvPLATZs. Therefore, the expression of HvPLATZs under abiotic stress conditions was determined (Figure 8 and Figure 9). The expression of eight HvPLATZs was detected in roots, whereas the expression of HvPLATZ5 and HvPLATZ11 was not observed in leaves (Figure 8 and Figure 9). The absence of HvPLATZ5 expression in leaves, as confirmed with qRT-PCR, was consistent with transcriptomic data [50] obtained from shoots of seedlings at the 10 cm shoot stage (Figure 7). The expression of HvPLATZs was influenced by salt, potassium deficiency, and osmotic stress treatments, but the response patterns varied depending on stress types. For example, HvPLATZ9 in roots was significantly downregulated under salt and osmotic stress conditions throughout the experiment, whereas it was upregulated after short-term (from 0.5 h to 3 h) and downregulated after long-term (from 1 to 3 d) potassium deficiency treatments, respectively. Similar results were also reported in SlPLATZs from tomato [51]. Moreover, tissue type also influenced response patterns. Under salt conditions, the expression of HvPLATZ9 was significantly downregulated in roots, whereas it was significantly upregulated in leaves after treatment for 3 h and 6 h (Figure 8 and Figure 9). Irrespective of stress and tissue types, the response patterns of HvPLATZs to abiotic stresses could be classified into three groups: (1) induction throughout the entire period, such as HvPLATZ3/5/6/8/11 in roots under salt conditions, HvPLATZ3 in roots under osmotic stress conditions, and HvPLATZ8 in leaves under salt and osmotic stress conditions; (2) suppression throughout the entire period, including HvPLATZ9 in roots under salt and osmotic stress conditions; (3) dynamic oscillation between induction and suppression, such as HvPLATZ10 in roots under osmotic stress conditions, HvPLATZ3/10 in leaves under salt conditions, and HvPLATZ10 in leaves under potassium deficiency conditions. These suggest that expression patterns of HvPLATZs were not only stress and tissue-type-related but also time-dependent.

3.3. Functions of HvPLATZs in Abiotic Stress Tolerance

The functional characterization of HvPLATZs in yeast revealed their involvement in salt and osmotic stress tolerance (Figure 10 and Figure 11). HvPLATZ2 expression compromised yeast growth under these stress conditions, indicating a negative regulatory role in salt and osmotic stress tolerance. This is consistent with the functions of AtPLATZ2/7 [17] and SiPLATZ12 [22] in salt tolerance and GmPLATZ17 [18] in drought tolerance. Conversely, the expression of HvPLATZ3/5/6/8/9/10/11 improved yeast growth under salt and osmotic stress conditions, suggesting a positive role in salt and osmotic stress tolerance. These findings are consistent with the functions observed for GhiPLATZ1/17/22 [20,23] in salt stress tolerance, AtPLATZ4 [16] and PhePLATZ1 [21] in drought tolerance, and AtPLATZ1/2 [15] in seed desiccation tolerance. Additionally, some PtPLATZs from Populus trichocarpa have also been reported to enhance yeast tolerance to cadmium [24].

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. HvPLATZ Genes Identification

The protein sequences of PLATZ genes from Arabidopsis and rice were retrieved from TAIR (https://www.arabidopsis.org/, accessed on 17 April 2023) and RiceData (https://ricedata.cn/, accessed on 17 April 2023), respectively, and were used for a blast search against the barley genome database (Morex v3). Meanwhile, “IPR006734” was used to search against the barley genome in Ensembl Plants (http://plants.ensembl.org/, accessed on 17 April 2023). Furthermore, “PLATZ” was used as a keyword to search against barley annotation files. The putative HvPLATZ genes were further scanned in InterPro [52], and only those containing the complete “IPR006734” domain were retained. Eleven HvPLATZ genes were identified in the end.

4.2. Physicochemical Properties and Subcellular Localizations

The molecular weights (MW), isoelectric points (pI), and instability indices of HvPLATZs were predicted using ExPASy [53]. Subcellular localizations of HvPLATZs were predicted using BUSCA [54].

4.3. Phylogeny, Syntenic Relationship, and Duplication Analyses

The PLATZ protein sequences from Arabidopsis (12), rice (15), maize (17) [10], and wheat (49) [29] were retrieved from TAIR, RGAP, MaizeGDB, and EnsemblPlants, respectively. Sequences of barley and these four plants were aligned using MAFFT (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/jdispatcher/msa/mafft?stype=protein, accessed on 28 April 2023) [55], and phylogenetic trees were constructed using MEGA X software (version 10.2.6) with the maximum-likelihood method (1000 bootstraps) [56]. The genome sequences and annotations of Arabidopsis, rice, maize, and wheat were downloaded to analyze syntenic relations with barley. Syntenic relationships and gene duplications were analyzed using TBtools (version 2.119) [57,58].

4.4. Sequence, Promoter, and Variation Analyses

Conserved motifs of HvPLATZs were identified using MEME Suite 5.5.2 [59] with parameters set to classic mode, with zero or one occurrence per sequence (zoops). Cis-acting elements in the 2 kb upstream regions of HvPLATZs coding sequences were identified using PlantCARE (https://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/, accessed on 17 April 2023) [60]. The pan-genome data [36] were obtained for variation analyses of 11 HvPLATZ genes.

4.5. Tissue-Specific Expression

Transcriptomic data (FPKM) of different tissues and stages were obtained from BARLEX (https://apex.ipk-gatersleben.de/apex/f?p=284:57::::::, accessed on 26 May 2023), normalized using a log10(FPKM + 1) transform, and visualized using TBtools [57].

4.6. Plant Growth and Abiotic Stress Treatments

Barley (cv. Golden promise) seeds were germinated in a 1/5 Hoagland solution for 6 d. The seedlings exhibiting uniform growth were transplanted into 5 L black barrels, with 18 plants per barrel. Eight days later, the seedlings were subjected to salt stress (200 mM NaCl), potassium deficiency (0.01 mM K+), and osmotic stress (20% PEG8000) in the background of a 1/5 Hoagland solution [61]. Plants growing in a 1/5 Hoagland solution were set as control. After treatments for 0.5 h, 1 h, 3 h, 6 h, 1 d, and 3 d, barley roots and leaves were collected for qRT-PCR. All samples were collected in three replicates, with two plants per replicate. During the entire growth period, seedlings were well aerated in a growth room and solutions were renewed every three days [61].

4.7. qRT-PCR

The MiniBEST Plant RNA Extraction Kit (9769, TaKaRa, Shiga, Japan) and PrimeScript RT Master Mix (RR036A, TaKaRa, Japan) were used for RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis, respectively. ChamQ Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Q711, Vazyme, Nanjing, China) was used for qRT-PCR with an LC480 II (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), conducting two technical replicates. Relative gene expressions were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method [62], with actin as the internal reference [58]. The primer sequences are listed in File S6.

4.8. Heterologous Expression of HvPLATZs in Yeast

The PrimeScript™ II 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (6210A, TaKaRa, Japan) was employed for synthesizing the 1st strand of cDNA. HvPLATZ genes were amplified with gene-specific primers (File S7) using Phanta Max Master Mix (P525, Vazyme, China). The pYES2-NTB was linearized using KpnI-HF (R3142V, New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) and then recombined with HvPLATZ PCR products using the ClonExpress II One Step Cloning Kit (C112, Vazyme, China). The recombinant vectors were transformed into DH5α cells (DL1001, WEIDI, Shanghai, China). Single colonies were verified via PCR and sequencing (File S7), and recombinant vectors were extracted using the TaKaRa MiniBEST Plasmid Purification Kit v.4.0 (9760, TaKaRa, Japan).

Recombinant vectors were transformed into an INVSC1 strain using the LiAc transformation method. The transformed INVSC1 strains were subsequently cultured on SD-Ura medium for 2 d. PCR-verified single colonies were then resuspended in sterile water (OD = 0.6), serially diluted (100, 10−1, and 10−2), and cultured at 30 °C on SG-Ura media with different concentrations of NaCl (0, 0.5, and 1.0 M) for 5 d. For the drought tolerance assay, single colonies were resuspended in sterile water (OD = 0.2) and shaken at 30 °C cultured on SG-Ura media containing various concentrations of PEG3350 (0, 30, 60, 90, and 120 mM) for 3 d. Yeast solutions were serially diluted (10−1, 10−2, and 10−3) and cultured at 30 °C on SG-Ura media for 4 d.

5. Conclusions

Eleven HvPLATZ genes were identified in barley and were classified into five clusters based on phylogeny. All HvPLATZ members possessed a typical PLATZ domain and exhibited conserved motif arrangements. Segmental duplication facilitated PLATZ family expansion in barley. HvPLATZs were core genes present in 20 genotypes of the barley pan-genome. The promoters of HvPLATZs contained a number of cis-acting elements involved in hormone and stress responses. The expression of HvPLATZs was influenced by abiotic stress and tissue type; furthermore, it varied over time. HvPLATZ2 negatively regulated salt tolerance in yeast, whereas HvPLATZ3/5/6/8/9/10/11 positively regulated salt tolerance. These findings advance our comprehension of the PLATZ family in barley and underpin further comprehensive functional characterization and breeding utilization of HvPLATZs.

Supplementary Materials

The supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms251810191/s1.

Author Contributions

K.C.: Conceptualization, Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing, Funding acquisition; X.S.: Investigation, Resources, Formal analysis; W.Y.: Formal analysis; L.L.: Formal analysis; F.G.: Formal analysis; J.W.: Writing—review and editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by an open project of the Key Laboratory of Digital Dry Land Crops of Zhejiang Province (2022E10012), the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LQ23C130004), the Zhejiang Science and Technology Major Program on Agricultural New Variety Breeding (2021C02064-3-2), and the China Agriculture Research System (CARS-05-01A-06).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article and Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Riechmann, J.L.; Heard, J.; Martin, G.; Reuber, L.; Jiang, C.; Keddie, J.; Adam, L.; Pineda, O.; Ratcliffe, O.J.; Samaha, R.R.; et al. Arabidopsis Transcription Factors: Genome-Wide Comparative Analysis among Eukaryotes. Science 2000, 290, 2105–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagano, Y.; Furuhashi, H.; Inaba, T.; Sasaki, Y. A Novel Class of Plant-Specific Zinc-Dependent DNA-Binding Protein That Binds to A/T-Rich DNA Sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001, 29, 4097–4105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, T.; Yin, X.; Wang, H.; Lu, P.; Liu, X.; Gong, C.; Wu, Y. ABA-INDUCED Expression 1 Is Involved in ABA-Inhibited Primary Root Elongation via Modulating ROS Homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Plant Sci. 2021, 304, 110821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.H.; Kim, J.; Jun, S.E.; Park, S.; Timilsina, R.; Kwon, D.S.; Kim, Y.; Park, S.J.; Hwang, J.Y.; Nam, H.G.; et al. ORESARA15, a PLATZ Transcription Factor, Mediates Leaf Growth and Senescence in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2018, 220, 609–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timilsina, R.; Kim, Y.; Park, S.; Park, H.; Park, S.J.; Kim, J.H.; Park, J.H.; Kim, D.; Park, Y.I.; Hwang, D.; et al. ORESARA 15, a PLATZ Transcription Factor, Controls Root Meristem Size through Auxin and Cytokinin Signalling-Related Pathways. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 2511–2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, A.; Hou, Q.; Si, L.; Huang, X.; Luo, J.; Lu, D.; Zhu, J.; Shangguan, Y.; Miao, J.; Xie, Y.; et al. The PLATZ Transcription Factor GL6 Affects Grain Length and Number in Rice. Plant Physiol. 2019, 180, 2077–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Fu, Y.; Lee, Y.R.J.; Chern, M.; Li, M.; Cheng, M.; Dong, H.; Yuan, Z.; Gui, L.; Yin, J.; et al. The PGS1 Basic Helix-Loop-Helix Protein Regulates Fl3 to Impact Seed Growth and Grain Yield in Cereals. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 1311–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.R.; Xue, H.W. The Rice PLATZ Protein SHORT GRAIN6 Determines Grain Size by Regulating Spikelet Hull Cell Division. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2020, 62, 847–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, J.; Ye, J.; Zheng, X.; Xiang, X.; Li, C.; Fu, M.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, Y. The Maize Imprinted Gene floury3 Encodes a PLATZ Protein Required for tRNA and 5S rRNA Transcription through Interaction with RNA Polymerase III. Plant Cell. 2017, 29, 2661–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ji, C.; Li, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, Y. Genome-Wide Analysis of the Plant-Specific PLATZ Proteins in Maize and Identification of Their General Role in Interaction with RNA Polymerase III Complex. BMC Plant Biol. 2018, 18, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, C.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, X.; Mo, Y.; Tranquilli, G.E.; Vanzetti, L.S.; Dubcovsky, J. Wheat Plant Height Locus RHT25 Encodes a PLATZ Transcription Factor That Interacts with DELLA (RHT1). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2300203120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lu, L.; Tao, J.J.; Cheng, T.; Jin, M.; Wang, Z.Y.; Wei, J.J.; Jiang, Z.H.; Sun, W.C.; et al. Global Analysis of Seed Transcriptomes Reveals a Novel PLATZ Regulator for Seed Size and Weight Control in Soybean. New Phytol. 2023, 240, 2436–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Liu, K.; Zhang, T.; Chen, J.; Zhao, S.; Cui, Y.; Zhou, W.; Yu, Y.; Chen, S.; Wang, C.; et al. The RhWRKY33a-RhPLATZ9 Regulatory Module Delays Petal Senescence by Suppressing Rapid Reactive Oxygen Species Accumulation in Rose Flowers. Plant J. 2023, 114, 1425–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guérin, C.; Behr, M.; Sait, J.; Mol, A.; El Jaziri, M.; Baucher, M. Evidence for Poplar PtaPLATZ18 in the Regulation of Plant Growth and Vascular Tissues Development. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1302536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Morales, S.I.; Chávez-Montes, R.A.; Hayano-Kanashiro, C.; Alejo-Jacuinde, G.; Rico-Cambron, T.Y.; de Folter, S.; Herrera-Estrella, L. Regulatory Network Analysis Reveals Novel Regulators of Seed Desiccation Tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E5232–E5241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wang, C.; Ji, Z.; Lu, J.; Zhang, L.; Li, C.; Huang, J.; Yang, G. Regulation of Drought Tolerance in Arabidopsis Involves the PLATZ4-Mediated Transcriptional Repression of Plasma Membrane Aquaporin PIP2;8. Plant J. 2023, 6, 434–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yang, R.; Liu, M.; Zhang, S.; Yan, K.; Yang, G.; Huang, J.; Zheng, C.; Wu, C. PLATZ2 Negatively Regulates Salt Tolerance in Arabidopsis Seedlings by Directly Suppressing the Expression of the CBL4/SOS3 and CBL10/SCaBP8 Genes. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 5589–5602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zheng, L.; Wei, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, M.; Wang, F.; Ma, Y.; Xu, Z. The Soybean PLATZ Transcription Factor GmPLATZ17 Suppresses Drought Tolerance by Interfering with Stress-Associated Gene Regulation of GmDREB5. Crop J. 2022, 10, 1014–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, H.; Choi, S.J.; Chung, E.; Lee, J. Molecular Characterization of Stress-Inducible PLATZ Gene from Soybean (Glycine max L.). Plant Omics 2015, 8, 479–484. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Yang, R.; Huo, Y.; Liu, S.; Yang, G.; Huang, J.; Zheng, C.; Wu, C. Expression of Cotton PLATZ1 in Transgenic Arabidopsis Reduces Sensitivity to Osmotic and Salt Stress for Germination and Seedling Establishment Associated with Modification of the Abscisic Acid, Gibberellin, and Ethylene Signalling Pathways. BMC Plant Biol. 2018, 18, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Lan, Y.; Wu, M.; Wang, L.; Liu, H.; Xiang, Y. PhePLATZ1, a PLATZ Transcription Factor in Moso Bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis), Improves Drought Resistance of Transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 186, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, S.; Zhang, L.; Wan, Y.; Tang, S.; Sui, Y.; Bai, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, M.; Fan, J.; Zhang, S.; et al. SiPLATZ12 Transcription Factor Negatively Regulates Salt Tolerance in Foxtail Millet (Setaria italica) by Suppressing the Expression of SiNHX, SiCBL and SiSOS Genes. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2023, 213, 105417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.; Tian, C.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Li, H.; He, S.; Jiao, Z.; Qayyum, A.; Du, X.; Peng, Z. GhiPLATZ17 and GhiPLATZ22, Zinc-Dependent DNA-Binding Transcription Factors, Promote Salt Tolerance in Upland Cotton. Plant Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Yang, H.; Bu, Y.; Wu, X.; Sun, N.; Xiao, J.; Jing, Y. Genome-Wide Identification of PLATZ Genes Related to Cadmium Tolerance in Populus trichocarpa and Characterization of the Role of PtPLATZ3 in Phytoremediation of Cadmium. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 228, 732–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zenda, T.; Liu, S.; Wang, X.; Liu, G.; Jin, H.; Dong, A.; Yang, Y.; Duan, H. Key Maize Drought-Responsive Genes and Pathways Revealed by Comparative Transcriptome and Physiological Analyses of Contrasting Inbred Lines. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, E.J.; Bonnot, T.; Hummel, M.; Hay, E.; Marzolino, J.M.; Quijada, I.A.; Nagel, D.H. Contribution of Time of Day and the Circadian Clock to the Heat Stress Responsive Transcriptome in Arabidopsis. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shi, S.H.; Li, F.L.; Zhao, C.Z.; Li, A.Q.; Hou, L.; Xia, H.; Wang, B.S.; Baltazar, J.L.; Wang, X.J.; et al. Global Transcriptome Analysis Provides New Insights in Thellungiella salsuginea Stress Response. Plant Biol. 2019, 21, 796–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin Azim, J.; Khan, M.F.H.; Hassan, L.; Robin, A.H.K. Genome-Wide Characterization and Expression Profiling of Plant-Specific PLATZ Transcription Factor Family Genes in Brassica rapa L. Plant Breed. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Liu, M.; Fang, Z.; Ma, D.; Zhou, Y.; Yin, J. Genome-Wide Analysis of a Plant at-Rich Sequence and Zinc-Binding Protein (PLATZ) in Triticum aestivum. Phyton-Int. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 90, 971–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; He, F.; Zhao, G.; Li, M.; Long, R.; Kang, J.; Yang, Q.; Chen, L. Genome-Wide Identification and Phylogenetic and Expression Analyses of the PLATZ Gene Family in Medicago sativa L. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Feng, S.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, L.; Luo, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Yang, Q.; Feng, B. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analysis of the Plant-Specific PLATZ Gene Family in Tartary Buckwheat (Fagopyrum tataricum). BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guruprasad, K.; Reddy, B.V.B.; Pandit, M.W. Correlation between Stability of a Protein and Its Dipeptide Composition: A Novel Approach for Predicting in Vivo Stability of a Protein from Its Primary Sequence. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 1990, 4, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogozin, I.B.; Carmel, L.; Csuros, M.; Koonin, E.V. Origin and Evolution of Spliceosomal Introns. Biol. Direct. 2012, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, Y.T.; Chao, Y.T.; Chen, W.C.; Shih, M.C.; Chang, S.B. Segmental and Tandem Chromosome Duplications Led to Divergent Evolution of the Chalcone Synthase Gene Family in Phalaenopsis orchids. Ann. Bot. 2019, 123, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monat, C.; Schreiber, M.; Stein, N.; Mascher, M. Prospects of Pan-Genomics in Barley. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2019, 132, 785–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayakodi, M.; Padmarasu, S.; Haberer, G.; Bonthala, V.S.; Gundlach, H.; Monat, C.; Lux, T.; Kamal, N.; Lang, D.; Himmelbach, A.; et al. The Barley Pan-Genome Reveals the Hidden Legacy of Mutation Breeding. Nature 2020, 588, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, R.; Rana, B.S.; Jha, A.K. Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP). In Encyclopedia of Animal Cognition and Behavior; Vonk, J., Shackelford, T., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tettelin, H.; Masignani, V.; Cieslewicz, M.J.; Donati, C.; Medini, D.; Ward, N.L.; Angiuoli, S.V.; Crabtree, J.; Jones, A.L.; Durkin, A.S.; et al. Genome Analysis of Multiple Pathogenic Isolates of Streptococcus agalactiae: Implications for the Microbial “Pan-Genome”. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 13950–13955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Cheng, M.; Li, M.; Guo, X.; Wu, Y.; Wang, J. Identification and Characterization of PLATZ Transcription Factors in Wheat. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, S.B.; Mitra, A.; Baumgarten, A.; Young, N.D.; May, G. The Roles of Segmental and Tandem Gene Duplication in the Evolution of Large Gene Families in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Plant Biol. 2004, 4, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Gao, Z.; Li, D.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y.; He, Q.; Qi, Y.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, J.; Xu, X.; et al. Functional Prediction of Tomato PLATZ Family Members and Functional Verification of SlPLATZ17. J. Integr. Agric. 2024, 23, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Dai, Y.; Li, R.; Yuan, L.; Chen, X.; Wang, X. Members of B-Box Protein Family from Malus domestica Enhanced Abiotic Stresses Tolerance in Escherichia Coli. Mol. Biotechnol. 2019, 61, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liang, J.; Luo, J.; Yang, F.; Feng, P.; Wang, H.; Guo, B.; Ma, F.; Zhao, T. Identification of PLATZ Genes in Malus and Expression Characteristics of MdPLATZs in Response to Drought and ABA Stresses. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1109784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Lan, Y.; Shi, Y.; Gao, Y.; Wu, M.; Xu, Y.; Xiang, Y. Systematic Analysis and Functional Characterization of the PLATZ Transcription Factors in Moso Bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis). J. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 42, 218–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Wang, H.; Wu, X.; Noman, M.; Wen, Y.; Li, D.; Song, F. Genome-Wide Characterization of the PLATZ Gene Family in Watermelon (Citrullus lanatus L.) with Putative Functions in Biotic and Abiotic Stress Response. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 201, 107854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, F.; Hou, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Hao, L.; Li, G.; Shao, J.; Tan, M. Genome-Wide Analysis of MdPLATZ Genes and Their Expression during Axillary Bud Outgrowth in Apple (Malus domestica Borkh.). BMC Genom. 2023, 24, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Rong, H.; Tian, Y.; Qu, Y.; Xu, M.; Xu, L.A. Genome-Wide Identification of PLATZ Transcription Factors in Ginkgo biloba L. and Their Expression Characteristics during Seed Development. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 946194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yuan, W.; Yuan, X.; Jiang, C.; An, Y.; Chen, N.; Huang, L.; Lu, M.; Zhang, J. Comparative Analysis of PLATZ Transcription Factors in Six Poplar Species and Analysis of the Role of PtrPLATZ14 in Leaf Development. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 263, 130471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ain-Ali, Q.U.; Mushtaq, N.; Amir, R.; Gul, A.; Tahir, M.; Munir, F. Genome-Wide Promoter Analysis, Homology Modeling and Protein Interaction Network of Dehydration Responsive Element Binding (DREB) Gene Family in Solanum tuberosum. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0261215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monat, C.; Padmarasu, S.; Lux, T.; Wicker, T.; Gundlach, H.; Himmelbach, A.; Ens, J.; Li, C.; Muehlbauer, G.J.; Schulman, A.H.; et al. TRITEX: Chromosome-Scale Sequence Assembly of Triticeae Genomes with Open-Source Tools. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wai, A.H.; Rahman, M.M.; Waseem, M.; Cho, L.H.; Naing, A.H.; Jeon, J.S.; Lee, D.J.; Kim, C.K.; Chung, M.Y. Comprehensive Genome-Wide Analysis and Expression Pattern Profiling of PLATZ Gene Family Members in Solanum lycopersicum L. under Multiple Abiotic Stresses. Plants 2022, 11, 3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paysan-Lafosse, T.; Blum, M.; Chuguransky, S.; Grego, T.; Pinto, B.L.; Salazar, G.A.; Bileschi, M.L.; Bork, P.; Bridge, A.; Colwell, L.; et al. InterPro in 2022. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D418–D427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasteiger, E.; Hoogland, C.; Gattiker, A.; Duvaud, S.; Wilkins, M.R.; Appel, R.D.; Bairoch, A. Protein Identification and Analysis Tools on the ExPASy Server; Walker, J.M., Ed.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Savojardo, C.; Martelli, P.L.; Fariselli, P.; Profiti, G.; Casadio, R. BUSCA: An Integrative Web Server to Predict Subcellular Localization of Proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W459–W466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madeira, F.; Pearce, M.; Tivey, A.R.N.; Basutkar, P.; Lee, J.; Edbali, O.; Madhusoodanan, N.; Kolesnikov, A.; Lopez, R. Search and Sequence Analysis Tools Services from EMBL-EBI in 2022. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, W276–W279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. TBtools: An Integrative Toolkit Developed for Interactive Analyses of Big Biological Data. Mol. Plant. 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, K.; Zeng, F.; Wang, J.; Zhang, G. Identification and Characterization of HAK/KUP/KT Potassium Transporter Gene Family in Barley and Their Expression under Abiotic Stress. BMC Genom. 2021, 22, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, T.L.; Johnson, J.; Grant, C.E.; Noble, W.S. The MEME Suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, W39–W49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lescot, M.; Déhais, P.; Thijs, G.; Marchal, K.; Moreau, Y.; Van de Peer, Y.; Rouzé, P.; Rombauts, S. PlantCARE, a Database of Plant Cis-Acting Regulatory Elements and a Portal to Tools for in Silico Analysis of Promoter Sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, K.; Kuang, L.; Yue, W.; Xie, S.; Xia, X.; Zhang, G.; Wang, J. Calmodulin and Calmodulin-like Gene Family in Barley: Identification, Characterization and Expression Analyses. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 964888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).