30 Years Since the Proposal of Exon Skipping Therapy for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy and the Future of Pseudoexon Skipping

Abstract

1. Introduction

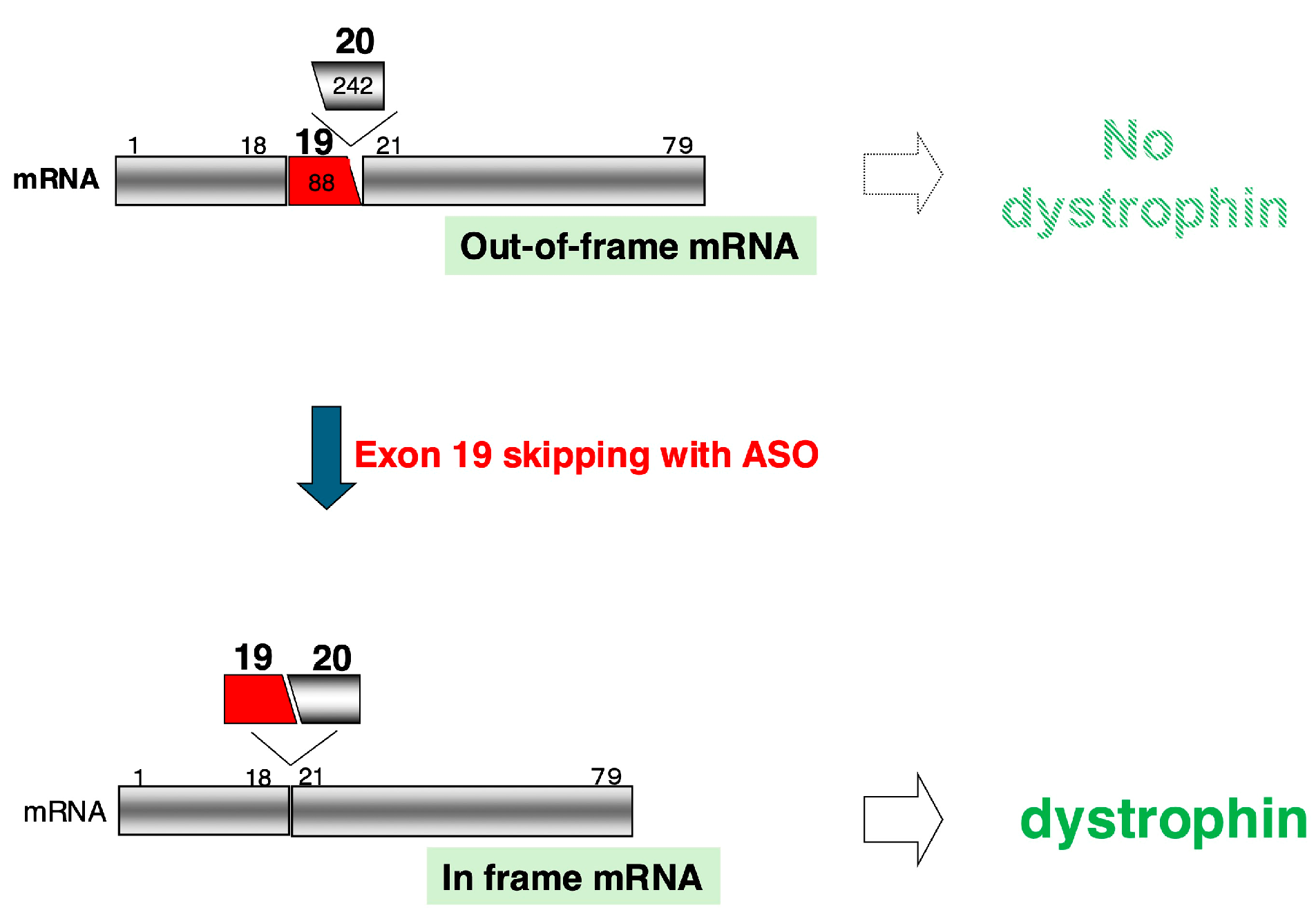

2. Exon-Skipping Therapy Using ASOs for DMD

2.1. Proposal of Exon-Skipping Therapy Using ASOs

2.2. ASOs Approved as Therapeutics for DMD

3. Development of ASO Therapeutics Inspired by Exon-Skipping Therapy for DMD

3.1. ASOs for Suppressing Exon Skipping

3.2. Expansion of Exon-Skipping Therapy

3.3. New Trends in Exon-Skipping Applications

4. Challenges and Improvements for ASO Drugs in DMD Treatment

4.1. Challenges of Approved ASO Drugs

4.2. Improvements in ASOs for DMD Treatment

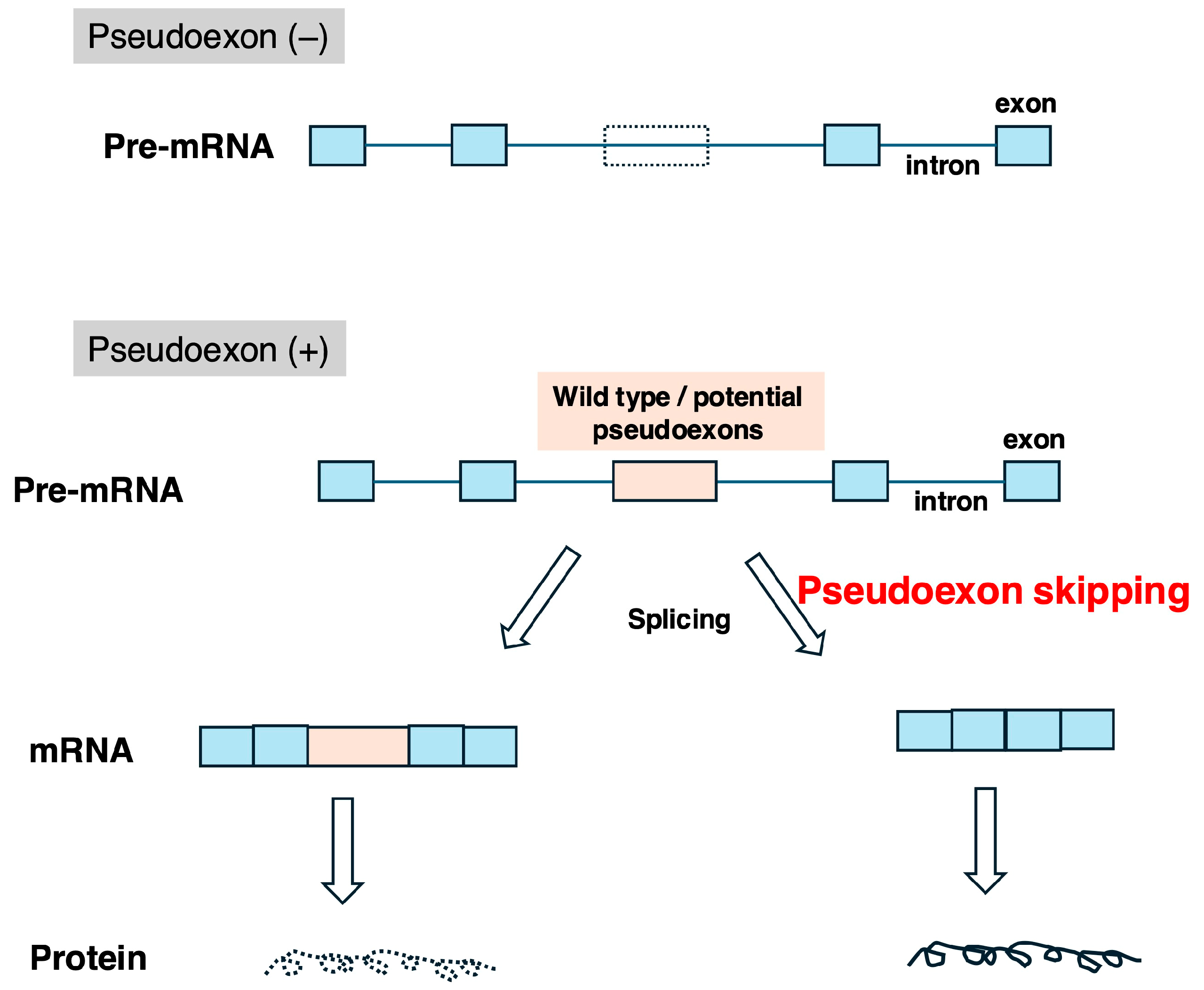

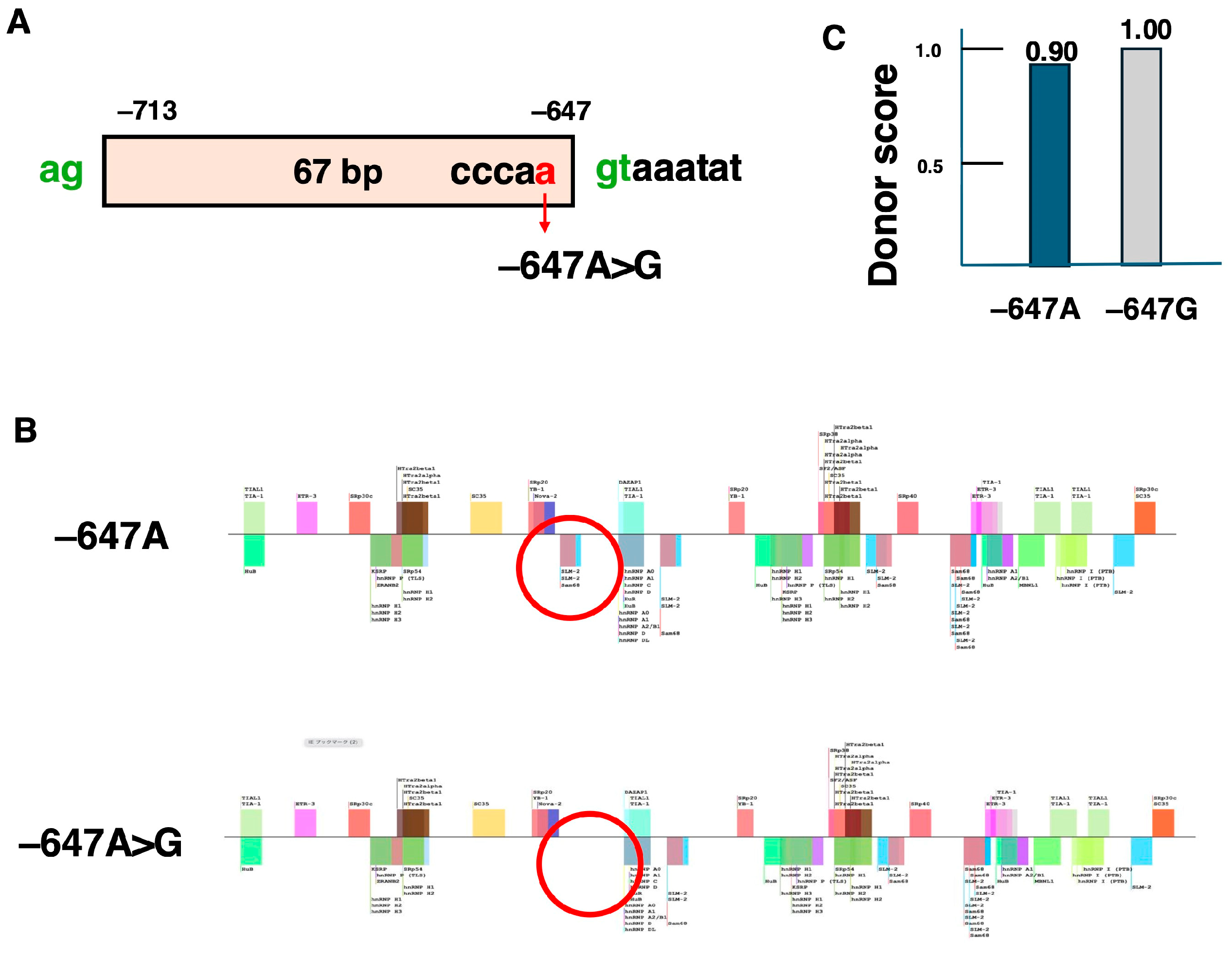

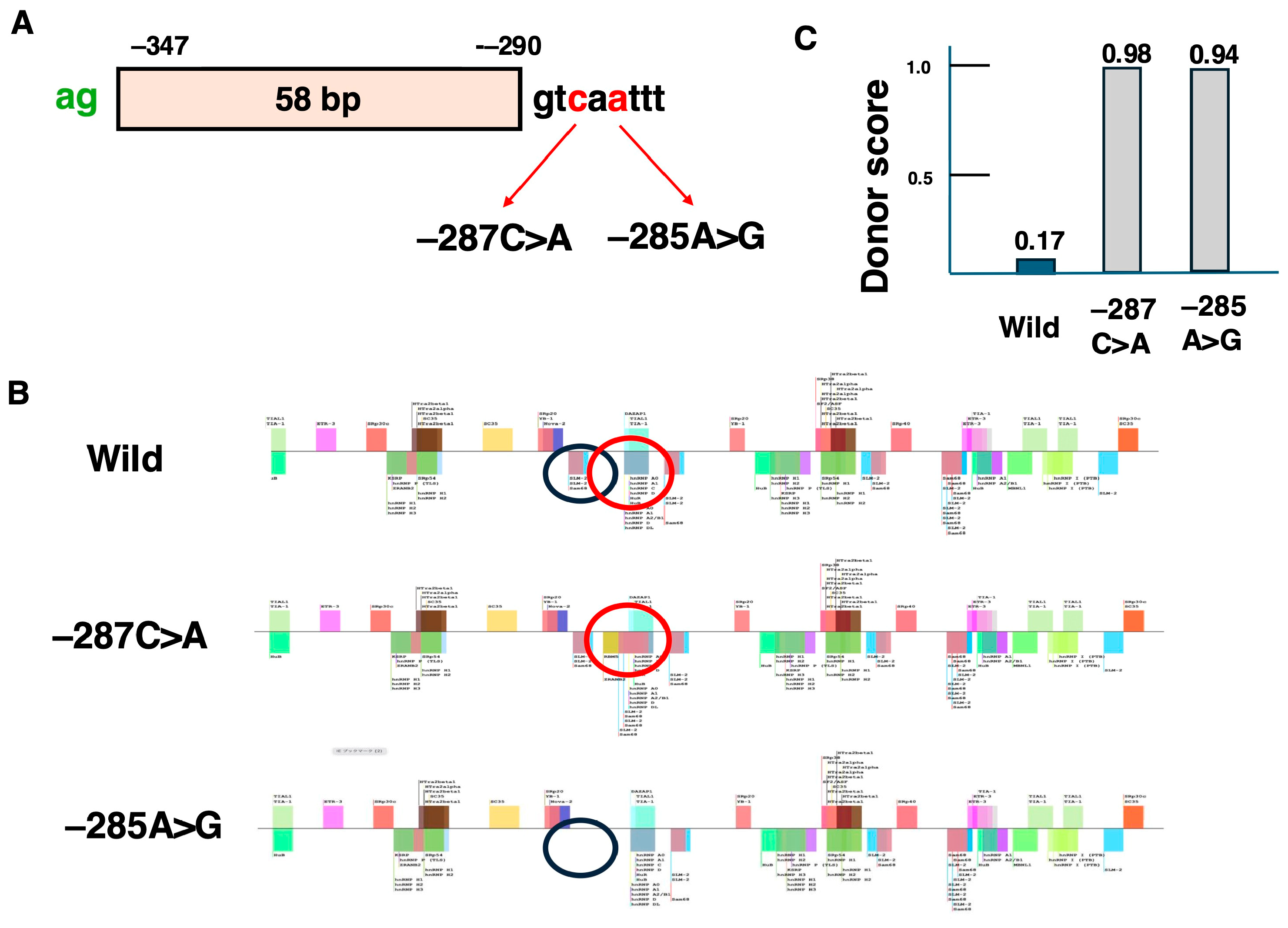

5. Therapeutic Strategies for Inducing Skipping of Pseudoexons in the DMD Gene

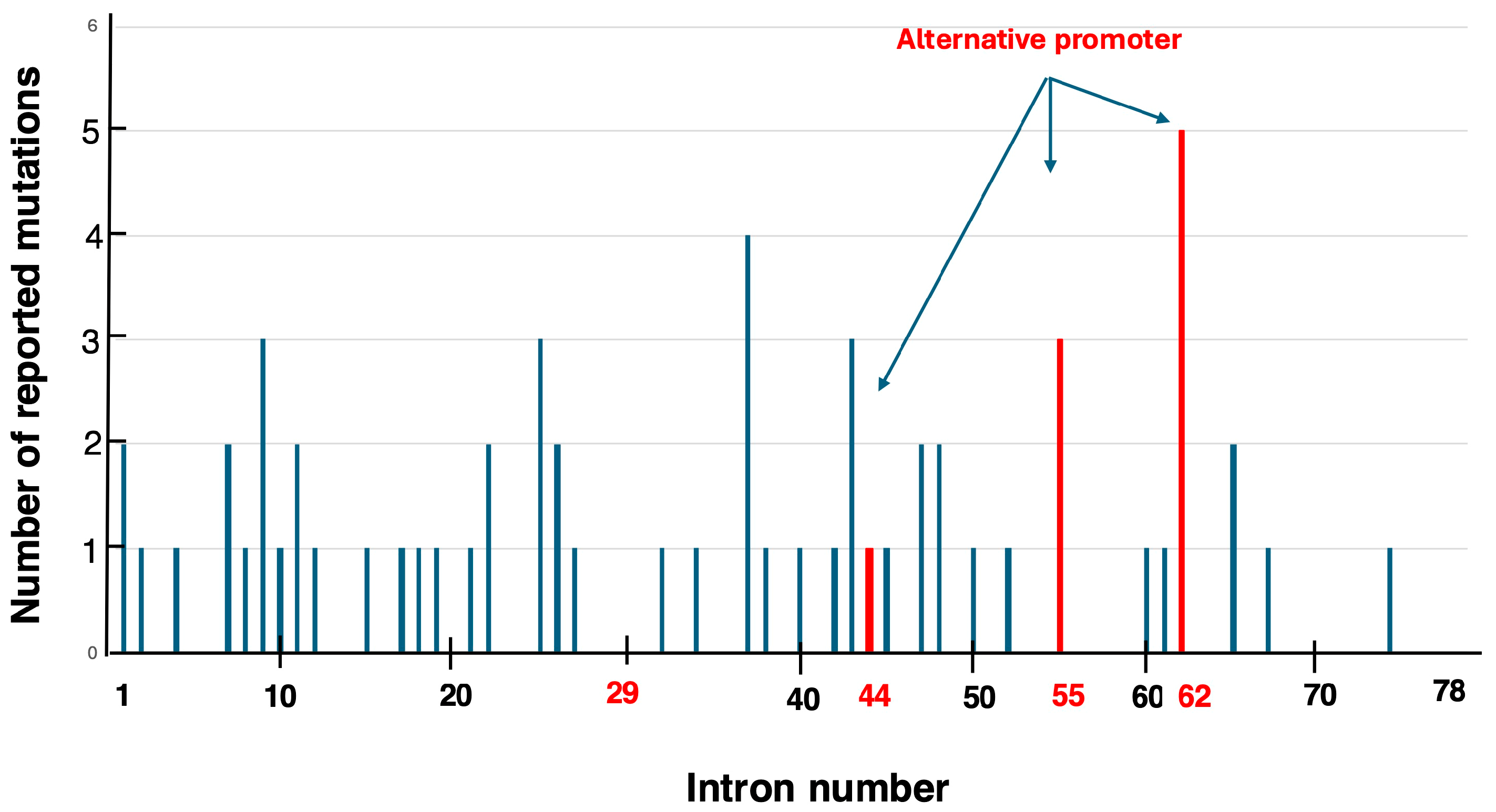

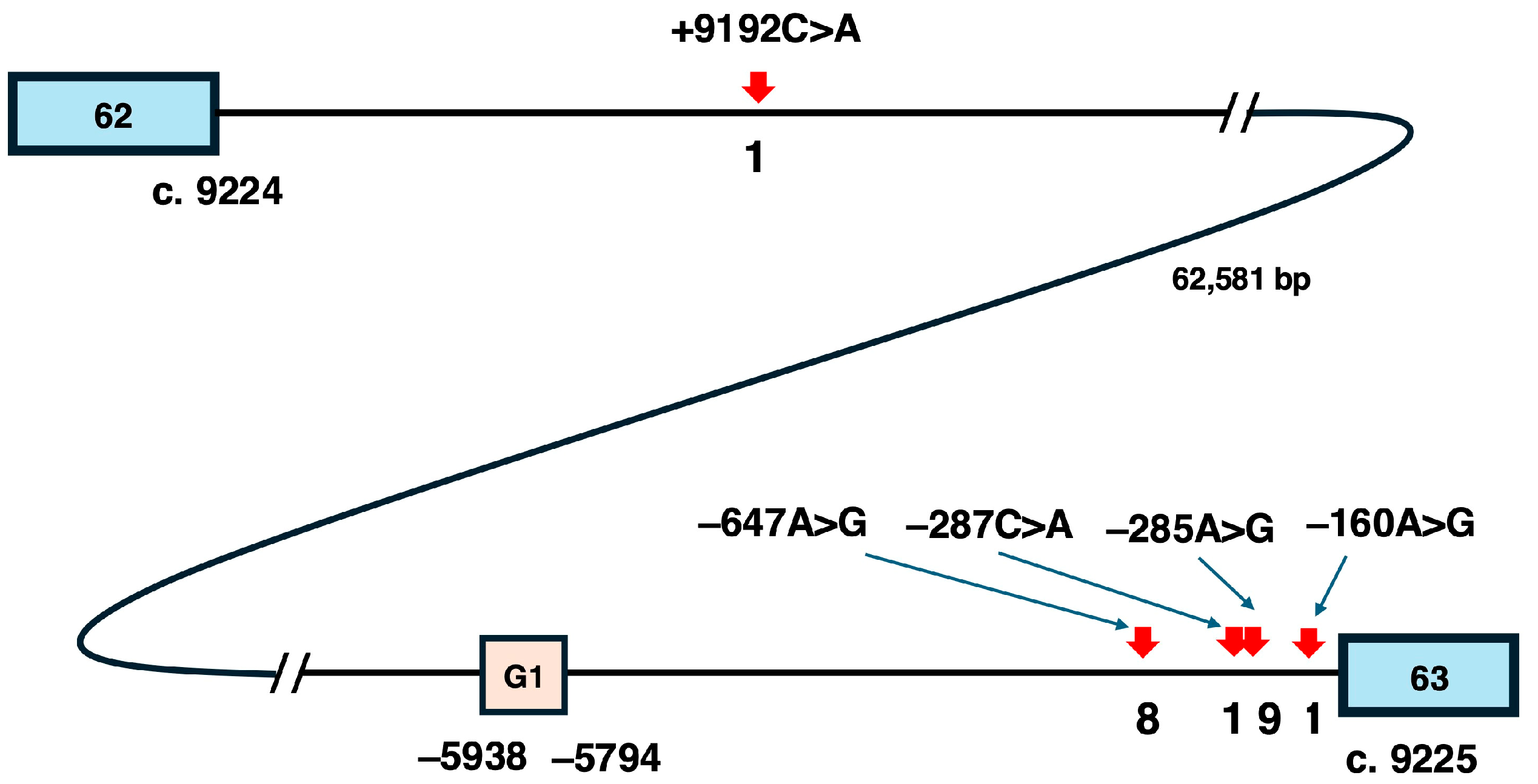

5.1. Identified Pseudoexons in the DMD Gene

5.2. Candidate Variants for Pseudoexon-Skipping Therapy

6. Final Remarks

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Duan, D.; Goemans, N.; Takeda, S.I.; Mercuri, E.; Aartsma Rus, A. Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2021, 7, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuo, M. Antisense Oligonucleotide-Mediated Exon-skipping Therapies: Precision Medicine Spreading from Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. JMA J. 2021, 4, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenig, M.; Hoffman, E.; Bertelson, C.; Monaco, A.; Feener, C.; Kunkel, L. Complete cloning of the duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) cDNA and preliminary genomic organization of the DMD gene in normal and affected individuals. Cell 1987, 50, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acsadi, G.; Dickson, G.; Love, D.R.; Jani, A.; Walsh, F.S.; Gurusinghe, A.; Wolff, J.A.; Davies, K.E. Human dystrophin ex-pression in mdx mice after intramuscular injection of DNA constructs. Nature 1991, 352, 815–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuo, M.; Masumura, T.; Nakajima, T.; Kitoh, Y.; Takumi, T.; Nishio, H.; Koga, J.; Nakamura, H. A very small frame-shifting deletion within exon 19 of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy gene. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1990, 170, 963–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuo, M.; Masumura, T.; Nishio, H.; Nakajima, T.; Kitoh, Y.; Takumi, T.; Koga, J.; Nakamura, H. Exon skipping during splicing of dystrophin mRNA precursor due to an intraexon deletion in the dystrophin gene of Duchenne muscular dystrophy kobe. J. Clin. Investig. 1991, 87, 2127–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeshima, Y.; Nishio, H.; Sakamoto, H.; Nakamura, H.; Matsuo, M. Modulation of in vitro splicing of the upstream intron by modifying an intra-exon sequence which is deleted from the dystrophin gene in dystrophin Kobe. J. Clin. Investig. 1995, 95, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pramono, Z.A.D.; Takeshima, Y.; Alimsardjono, H.; Ishii, A.; Takeda, S.-I.; Matsuo, M. Induction of Exon Skipping of the Dystrophin Transcript in Lymphoblastoid Cells by Transfecting an Antisense Oligodeoxynucleotide Complementary to an Exon Recognition Sequence. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996, 226, 445–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeshima, Y.; Wada, H.; Yagi, M.; Ishikawa, Y.; Ishikawa, Y.; Minami, R.; Nakamura, H.; Matsuo, M. Oligonucleotides against a splicing enhancer sequence led to dystrophin production in muscle cells from a Duchenne muscular dystrophy patient. Brain Dev. 2001, 23, 788–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeshima, Y.; Yagi, M.; Wada, H.; Ishibashi, K.; Nishiyama, A.; Kakumoto, M.; Sakaeda, T.; Saura, R.; Okumura, K.; Matsuo, M. Intravenous Infusion of an Antisense Oligonucleotide Results in Exon Skipping in Muscle Dystrophin mRNA of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Pediatr. Res. 2006, 59, 690–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aartsma-Rus, A.; Van Ommen, G.J.B. Antisense-mediated exon skipping: A versatile tool with therapeutic and research applications. RNA 2007, 13, 1609–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishikawa, Y.; Miura, T.; Nambu, N.; Awano, H.; Takeshima, Y.; Matsuo, M. A Duchenne muscular dystrophy patient treated with short-term exon skipping therapy 20 years ago exhibits superior cardiac function compared to untreated cases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025. in submission. [Google Scholar]

- Aartsma-Rus, A.; Janson, A.A.; Kaman, W.E.; Bremmer-Bout, M.; Dunnen, J.T.D.; Baas, F.; van Ommen, G.-J.B.; van Deutekom, J.C. Therapeutic antisense-induced exon skipping in cultured muscle cells from six different DMD patients. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003, 12, 907–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goemans, N.M.; Tulinius, M.; van den Akker, J.T.; Burm, B.E.; Ekhart, P.F.; Heuvelmans, N.; Holling, T.; Janson, A.A.; Platenburg, G.J.; Sipkens, J.A.; et al. Systemic Administration of PRO051 in Duchenne′s Muscular Dystrophy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 1513–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Deutekom, J.C.; Janson, A.A.; Ginjaar, I.B.; Frankhuizen, W.S.; Aartsma-Rus, A.; Bremmer-Bout, M.; Den Dunnen, J.T.; Koop, K.; Van Der Kooi, A.J.; Goemans, N.M.; et al. Local Dystrophin Restoration with Antisense Oligonucleotide PRO051. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 2677–2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Echevarría, L.; Aupy, P.; Goyenvalle, A. Exon-skipping advances for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2018, 27, R163–R172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aartsma-Rus, A.; Krieg, A.M. FDA Approves Eteplirsen for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: The Next Chapter in the Eteplirsen Saga. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2017, 27, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, C.S.; Pyle, A.D. Exon Skipping Therapy. Cell 2016, 167, 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assefa, M.; Gepfert, A.; Zaheer, M.; Hum, J.M.; Skinner, B.W. Casimersen (AMONDYS 45™): An Antisense Oligonucleotide for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincik, L.Y.; Dautel, A.D.; Staples, A.A.; Lauck, L.V.; Armstrong, C.J.; Howard, J.T.; McGregor, D.; Ahmadzadeh, S.; Shekoohi, S.; Kaye, A.D. Evolving Role of Viltolarsen for Treatment of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Adv. Ther. 2024, 41, 1338–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, S. Viltolarsen: First Approval. Drugs 2020, 80, 1027–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heo, Y.A. Golodirsen: First Approval. Drugs 2020, 80, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirley, M. Casimersen: First Approval. Drugs 2021, 81, 875–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aartsma-Rus, A.; Fokkema, I.; Verschuuren, J.; Ginjaar, I.; Van Deutekom, J.; Van Ommen, G.-J.; Den Dunnen, J.T. Theoretic applicability of antisense-mediated exon skipping for Duchenne muscular dystrophy mutations. Hum. Mutat. 2009, 30, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantara, S.; Simoncelli, G.; Ricci, C. Antisense Oligonucleotides (ASOs) in Motor Neuron Diseases: A Road to Cure in Light and Shade. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauffer, M.C.; van Roon-Mom, W.; Aartsma-Rus, A. Possibilities and limitations of antisense oligonucleotide therapies for the treatment of monogenic disorders. Commun. Med. 2024, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skordis, L.A.; Dunckley, M.G.; Yue, B.; Eperon, I.C.; Muntoni, F. Bifunctional antisense oligonucleotides provide a trans-acting splicing enhancer that stimulates SMN2 gene expression in patient fibroblasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2003, 100, 4114–4119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercuri, E.; Darras, B.T.; Chiriboga, C.A.; Day, J.W.; Campbell, C.; Connolly, A.M.; Iannaccone, S.T.; Kirschner, J.; Kuntz, N.L.; Saito, K.; et al. Nusinersen versus Sham Control in Later-Onset Spinal Muscular Atrophy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grainok, J.; Pitout, I.L.; Chen, F.K.; McLenachan, S.; Jeffery, R.C.H.; Mitrpant, C.; Fletcher, S. A Precision Therapy Approach for Retinitis Pigmentosa 11 Using Splice-Switching Antisense Oligonucleotides to Restore the Open Reading Frame of PRPF31. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.J.; Krainer, A.R. Antisense Oligonucleotide Therapeutics for Cystic Fibrosis: Recent Developments and Perspectives. Mol. Cells 2023, 46, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuijper, E.C.; Overzier, M.; Suidgeest, E.; Dzyubachyk, O.; Maguin, C.; Pérot, J.-B.; Flament, J.; Ariyurek, Y.; Mei, H.; Buijsen, R.A.; et al. Antisense oligonucleotide-mediated disruption of HTT caspase-6 cleavage site ameliorates the phenotype of YAC128 Huntington disease mice. Neurobiol. Dis. 2023, 190, 106368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, S.R.; Drack, A.V.; Cideciyan, A.V.; Jacobson, S.G.; Leroy, B.P.; Van Cauwenbergh, C.; Ho, A.C.; Dumitrescu, A.V.; Han, I.C.; Martin, M.; et al. Intravitreal antisense oligonucleotide sepofarsen in Leber congenital amaurosis type 10: A phase 1b/2 trial. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 1014–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Daele, S.; Masrori, P.; Van Damme, P.; Van Den Bosch, L. The sense of antisense therapies in ALS. Trends Mol. Med. 2024, 30, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Hu, C.; Moufawad El Achkar, C.; Black, L.E.; Douville, J.; Larson, A.; Pendergast, M.K.; Goldkind, S.F.; Lee, E.A.; Kuniholm, A.; et al. Patient-Customized Oligonucleotide Therapy for a Rare Genetic Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1644–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aartsma-Rus, A.; Collin, R.W.; Elgersma, Y.; Lauffer, M.C.; van Roon-Mom, W. Joining forces to develop individualized antisense oligonucleotides for patients with brain or eye diseases: The example of the Dutch Center for RNA Therapeutics. Ther. Adv. Rare Dis. 2024, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, M.; Maeta, K.; Suzuki, H.; Kurosawa, R.; Takenouchi, T.; Awaya, T.; Ajiro, M.; Takeuchi, A.; Nishio, H.; Hagiwara, M.; et al. Successful skipping of abnormal pseudoexon by antisense oligonucleotides in vitro for a patient with beta-propeller protein-associated neurodegeneration. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aartsma-Rus, A.; Goemans, N. A Sequel to the Eteplirsen Saga: Eteplirsen Is Approved in the United States but Was Not Approved in Europe. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2019, 29, 13–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odouard, I.; Ballreich, J.; Socal, M. Medicaid spending and utilization of gene and RNA therapies for rare inherited condi-tions. Health Aff. Sch. 2024, 2, qxae051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, U.S.; Kohut, M.; Yokota, T. Comprehensive review of adverse reactions and toxicology in ASO-based therapies for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: From FDA-approved drugs to peptide-conjugated ASO. Curr. Res. Toxicol. 2024, 7, 100182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faiella, M.; Botti, G.; Dalpiaz, A.; Gnudi, L.; Goyenvalle, A.; Pavan, B.; Perrone, D.; Bovolenta, M.; Marchesi, E. In Vitro Studies to Evaluate the Intestinal Permeation of an Ursodeoxycholic Acid-Conjugated Oligonucleotide for Duchenne Mus-cular Dystrophy Treatment. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deprey, K.; Batistatou, N.; Kritzer, J.A. A critical analysis of methods used to investigate the cellular uptake and subcellular localization of RNA therapeutics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 7623–7639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dastpeyman, M.; Sharifi, R.; Amin, A.; Karas, J.A.; Cuic, B.; Pan, Y.; Nicolazzo, J.A.; Turner, B.J.; Shabanpoor, F. Endosomal escape cell-penetrating peptides significantly enhance pharmacological effectiveness and CNS activity of systemically administered antisense oligonucleotides. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 599, 120398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, N.; Tone, Y.; Nagata, T.; Masuda, S.; Saito, T.; Motohashi, N.; Takagaki, K.; Aoki, Y.; Takeda, S. Exon 44 skipping in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: NS-089/NCNP-02, a dual-targeting antisense oligonucleotide. Mol. Ther.—Nucleic Acids 2023, 34, 102034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Deutekom, J.; Beekman, C.; Bijl, S.; Bosgra, S.; Eijnde, R.v.D.; Franken, D.; Groenendaal, B.; Harquouli, B.; Janson, A.; Koevoets, P.; et al. Next Generation Exon 51 Skipping Antisense Oligonucleotides for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2023, 33, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aartsma-Rus, A.; De Waele, L.; Houwen-Opstal, S.; Kirschner, J.; Krom, Y.D.; Mercuri, E.; Niks, E.H.; Straub, V.; van Duyvenvoorde, H.A.; Vroom, E. The Dilemma of Choice for Duchenne Patients Eligible for Exon 51 Skipping The European Experience. J. Neuromuscul. Dis. 2023, 10, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelbeen, S.; O′Reilly, D.; Van De Vijver, D.; Verhaart, I.; van Putten, M.; Hariharan, V.; Hassler, M.; Khvorova, A.; Damha, M.J.; Aartsma-Rus, A. Challenges of Assessing Exon 53 Skipping of the Human DMD Transcript with Locked Nucleic Acid-Modified Antisense Oligonucleotides in a Mouse Model for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2023, 33, 348–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doisy, M.; Vacca, O.; Saoudi, A.; Goyenvalle, A. Levels of Exon-Skipping Are Not Artificially Overestimated Because of the Increased Affinity of Tricyclo-DNA-Modified Antisense Oligonucleotides to the Target DMD Exon. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, N.M.; Calabrese, K.A.; Sun, C.M.; Tully, C.B.; Heier, C.R.; Fiorillo, A.A. Deletion of miR-146a enhances therapeutic protein restoration in model of dystrophin exon skipping. Mol. Ther.—Nucleic Acids 2024, 35, 102228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, K.R. The elusive promise of myostatin inhibition for muscular dystrophy. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2020, 33, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybalka, E.; Timpani, C.A.; Debruin, D.A.; Bagaric, R.M.; Campelj, D.G.; Hayes, A. The Failed Clinical Story of Myostatin Inhibitors against Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: Exploring the Biology behind the Battle. Cells 2020, 9, 2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeta, K.; Farea, M.; Nishio, H.; Matsuo, M. A novel splice variant of the human MSTN gene encodes a myostatin-specific myostatin inhibitor. J. Cachex- Sarcopenia Muscle 2023, 14, 2289–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birnkrant, D.J.; Ararat, E.; Mhanna, M.J. Cardiac phenotype determines survival in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2015, 51, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Chowns, J.; Day, S.M. Novel Insights Into DMD-Associated Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Circ. Genom. Precis. Med. 2023, 16, 431–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blain, A.M.; Greally, E.; McClorey, G.; Manzano, R.; Betts, C.A.; Godfrey, C.; O’donovan, L.; Coursindel, T.; Gait, M.J.; Wood, M.J.; et al. Peptide-conjugated phosphodiamidate oligomer-mediated exon skipping has benefits for cardiac function in mdx and Cmah-/-mdx mouse models of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0198897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamura, N.; Takakusa, H.; Asano, D.; Watanabe, K.; Shibaya, Y.; Yamanaka, R.; Fusegawa, K.; Kanda, A.; Nagase, H.; Takaishi, K.; et al. Tissue distribution of renadirsen sodium, a dystrophin exon-skipping antisense oligonucleotide, in heart and diaphragm after subcutaneous administration to cynomolgus monkeys. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 2024, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, U.S.S.; Doktor, T.K.; Andresen, B.S. Pseudoexon activation in disease by non-splice site deep intronic sequence variation—wild type pseudoexons constitute high-risk sites in the human genome. Hum. Mutat. 2021, 43, 103–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhir, A.; Buratti, E. Alternative splicing: Role of pseudoexons in human disease and potential therapeutic strategies. FEBS J. 2010, 277, 841–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keegan, N.P. Pseudoexons of the DMD Gene. J. Neuromuscul. Dis. 2020, 7, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeshima, Y.; Yagi, M.; Okizuka, Y.; Awano, H.; Zhang, Z.; Yamauchi, Y.; Nishio, H.; Matsuo, M. Mutation spectrum of the dystrophin gene in 442 Duchenne/Becker muscular dystrophy cases from one Japanese referral center. J. Hum. Genet. 2010, 55, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Habara, Y.; Nishiyama, A.; Oyazato, Y.; Yagi, M.; Takeshima, Y.; Matsuo, M. Identification of seven novel cryptic exons embedded in the dystrophin gene and characterization of 14 cryptic dystrophin exons. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 52, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurvich, O.L.; Tuohy, T.M.; Howard, M.T.; Finkel, R.S.; Medne, L.; Anderson, C.B.; Weiss, R.B.; Wilton, S.D.; Flanigan, K.M. DMD pseudoexon mutations: Splicing efficiency, phenotype, and potential therapy. Ann. Neurol. 2007, 63, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatto, F.; Benemei, S.; Piluso, G.; Bello, L. The complex landscape of DMD mutations: Moving towards personalized medicine. Front. Genet. 2024, 15, 1360224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Tang, L.; Xie, Z.; Sun, C.; Shuai, H.; Zhou, C.; Liu, Y.; Yu, M.; Zheng, Y.; Meng, L.; et al. Splicing Characteristics of Dystrophin Pseudoexons and Identification of a Novel Pathogenic Intronic Variant in the DMD Gene. Genes 2020, 11, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Han, C.; Mai, J.; Jiang, X.; Liao, J.; Hou, Y.; Cui, D. Novel Intronic Mutations Introduce Pseudoexons in DMD That Cause Muscular Dystrophy in Patients. Front. Genet. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keegan, N.P.; Wilton, S.D.; Fletcher, S. Analysis of Pathogenic Pseudoexons Reveals Novel Mechanisms Driving Cryptic Splicing. Front. Genet. 2022, 12, 806946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldrop, M.A.; Moore, S.A.; Mathews, K.D.; Darbro, B.W.; Medne, L.; Finkel, R.; Connolly, A.M.; Crawford, T.O.; Drachman, D.; Wein, N.; et al. Intron mutations and early transcription termination in Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophy. Hum. Mutat. 2022, 43, 511–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Lu, Y.; Yu, H.; Xie, Z.; Sun, C.; Cheng, X.; Niu, F.; Zhao, Y.; Deng, J.; Meng, L.; et al. A novel deep intronic variant introduce dystrophin pseudoexon in Becker muscular dystrophy: A case report. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuffery-Giraud, S.; Béroud, C.; Leturcq, F.; Ben Yaou, R.; Hamroun, D.; Michel-Calemard, L.; Moizard, M.-P.; Bernard, R.; Cossée, M.; Boisseau, P.; et al. Genotype-phenotype analysis in 2,405 patients with a dystrophinopathy using the UMD-DMD database: A model of nationwide knowledgebase. Hum. Mutat. 2009, 30, 934–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.; Gal-Mark, N.; Kfir, N.; Oren, R.; Kim, E.; Ast, G. Alu Exonization Events Reveal Features Required for Precise Recognition of Exons by the Splicing Machinery. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2009, 5, e1000300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Z.; Liu, C.; Lu, Y.; Sun, C.; Liu, Y.; Yu, M.; Shu, J.; Meng, L.; Deng, J.; Zhang, W.; et al. Exonization of a deep intronic long interspersed nuclear element in Becker muscular dystrophy. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 979732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Pizarro, A.; Leal, F.; Holm, L.L.; Doktor, T.K.; Petersen, U.S.; Bueno, M.; Thöny, B.; Pérez, B.; Andresen, B.S.; Desviat, L.R. Antisense Oligonucleotide Rescue of Deep-Intronic Variants Activating Pseudoexons in the 6-Pyruvoyl-Tetrahydropterin Synthase Gene. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2022, 32, 378–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Name | Target Exon | Year of Approval |

|---|---|---|

| Eteplirsen | 51 | 2016 |

| Golodrisen | 53 | 2020 |

| Viltolarsen | 53 | 2020 |

| Casimersen | 45 | 2021 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Matsuo, M. 30 Years Since the Proposal of Exon Skipping Therapy for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy and the Future of Pseudoexon Skipping. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1303. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26031303

Matsuo M. 30 Years Since the Proposal of Exon Skipping Therapy for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy and the Future of Pseudoexon Skipping. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(3):1303. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26031303

Chicago/Turabian StyleMatsuo, Masafumi. 2025. "30 Years Since the Proposal of Exon Skipping Therapy for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy and the Future of Pseudoexon Skipping" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 3: 1303. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26031303

APA StyleMatsuo, M. (2025). 30 Years Since the Proposal of Exon Skipping Therapy for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy and the Future of Pseudoexon Skipping. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(3), 1303. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26031303