Deaminase-Driven Reverse Transcription Mutagenesis in Oncogenesis: Critical Analysis of Transcriptional Strand Asymmetries of Single Base Substitution Signatures

Abstract

:1. Introduction

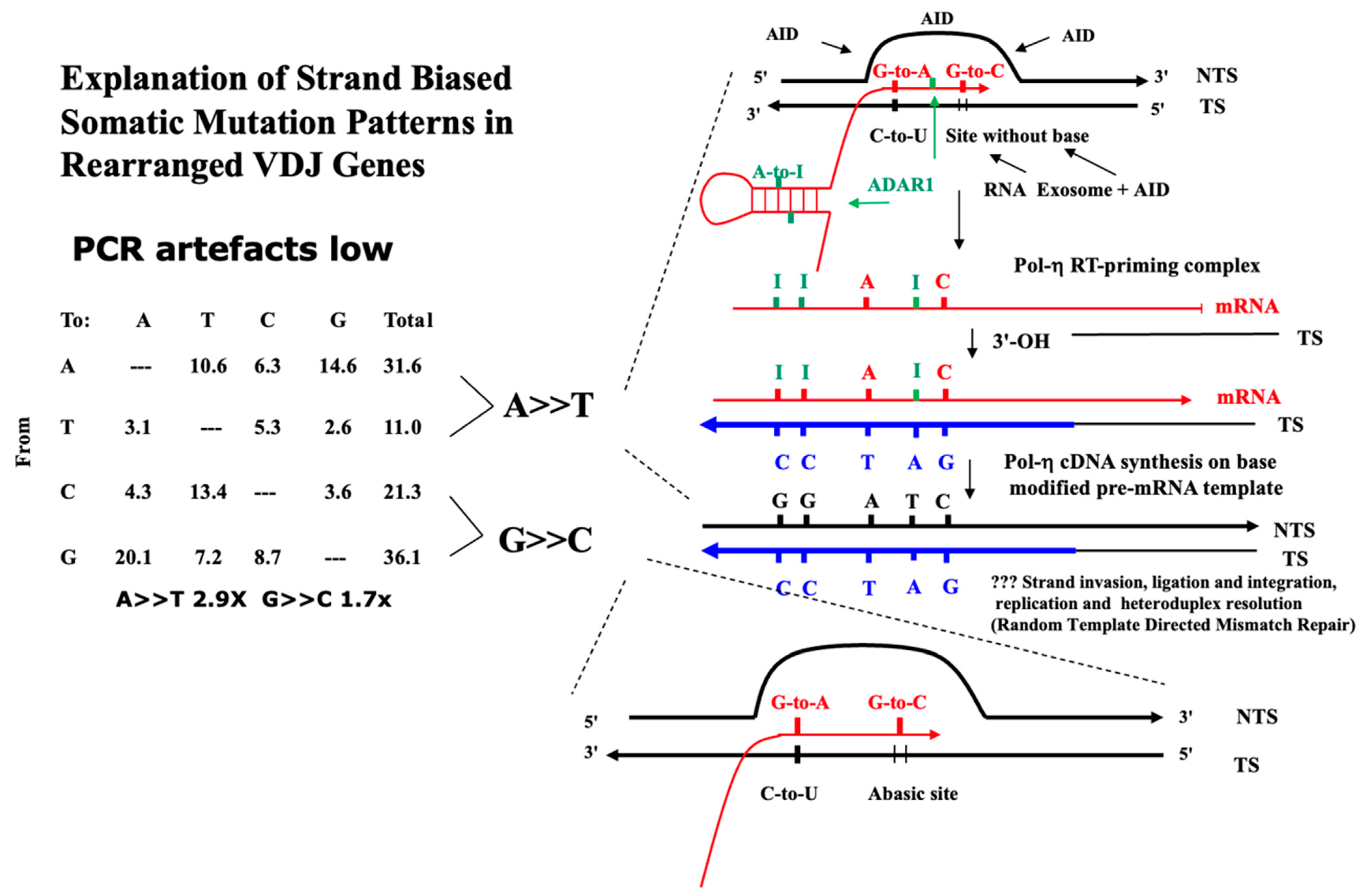

| A. Somatic mutations (Mean % 12 Studies Plus SEM) in Rearranged Murine IgV Loci | ||||||

| Mutant Base | ||||||

| From | A | T | C | G | Total | Strand Bias Factor |

| A | 10.6 (1.2) | 6.3 (0.9) | 14.6 (0.7) | 31.6 (1.7) | A>>T 2.9× | |

| T | 3.1 (0.6) | 5.3 (1.1) | 2.6 (0.6) | 11.0 (1.3) | p < 0.001 | |

| C | 4.3 (0.8) | 13.4 (1.3) | 3.6 (0.7) | 21.3 (1.3) | G>>C 1.7× | |

| G | 20.1 (1.9) | 7.2 (1.4) | 8.7 (0.7) | 36.1 (2.5) | p < 0.001 | |

| B. Somatic Mutations (as Percentage of Total 89,120 Mutations) in SBS5 | ||||||

| Mutant Base | ||||||

| From | A | T | C | G | Total | Strand Bias Factor |

| A | 5.3 | 3.7 | 16 | 25 | A>>T 1.1× | |

| T | 4.9 | 13.9 | 4.3 | 23.1 | p < 0.001 | |

| C | 5.4 | 15.5 | 4.2 | 25.2 | G>>C 1.1× | |

| G | 15.9 | 6.5 | 4.2 | 26.5 | p < 0.001 | |

| C. Somatic Mutations (as Percentage of Total 53,833 Mutations) in SBS3 | ||||||

| Mutant Base | ||||||

| From | A | T | C | G | Total | Strand Bias Factor |

| A | 8.4 | 4.7 | 8.8 | 21.8 | A>>T 1.04× | |

| T | 7.8 | 8.1 | 5.2 | 21 | p > 0.05 | |

| C | 9.3 | 8.4 | 9.5 | 27.2 | G>>C 1.1× | |

| G | 9.3 | 10.9 | 9.8 | 29.9 | p < 0.001 | |

| Alexandrov and colleagues [10,11,12] report single base substitution signatures (SBS) of mutagenesis in cancer using an algorithm-extraction of tri-nucleotide signatures from whole exome (WES) and whole genome (WGS) sequence data from thousands of cancer genomes. The present categories offer an alternative way of understanding these somatic mutation patterns based on the likelihood of the origin of the dominant deaminase-driven signature—C-site or A-site, or both C-site plus A-site. This categorisation is cognisant of the fact that certain apparent non-deaminase driven or ‘environmental exposure’ signatures (Tobacco Smoking, UV exposure, Reactive Oxygen Species viz. 8oxoG) are also present in certain cancer genomes. The most dominant signature is SBS5 occurring in all cancer genomes sequenced. SBS5 displays a ‘dysregulated Ig-Like SHM’ somatic mutation pattern [1,7,8,9,13,14] with transcriptional strand bias of mutations of A exceeding mutations of T (A>>T) and mutations of G exceeding mutations of C (G>>C), as in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3, online Supplementary Tables S1–S3. This strand-biased mutation pattern is also observed at both Ig and non-Ig loci (the TP53 DNA binding region) that have undergone somatic mutagenesis [7,14]. Listed below are the authors’ main Deaminase Driven Categories. Superscript T indicates Transcriptional Strand Asymmetry. The SBS Mutational Signatures (v3.4—October 2023) are at The Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC) website at https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/signatures/sbs/ (accessed on 15 April 2024) |

| C-site predominantly (putative AID/APOBEC driven) |

| SBS1T (at ACG strong strand bias, 5-meCpG, but slight reverse C>>G at CCG, GCG, TCG), SBS2, SBS6, SBS13, SBS19T (pure almost G>A >>C>T only), SBS7a, SBS7b |

| A-site predominantly (putative ADAR1 and coupled Target Site Reverse Transcription [TSRT], Pol-Eta and/or possibly DNA Pol-Theta driven) |

| SBS12T(Liver), SBS16T (Liver), SBS17aT, SBS17bT (but reverse strand bias not A>>T it is T>>A), SBS21T (DNA mismatch repair deficiency, but apparent reverse strand bias not A>>T it is T>>A) |

| C-site plus A-site more or less balanced “Ig-SHM-like” (AID/APOBEC/ADAR driven + TSRT via Pol eta, Pol theta?) SBS5T (SBS40 = SBS5?), SBS3T, SBS9T (but apparent reverse strand bias not A>>T it is T>>A). |

| SBS signatures not highlighted in above categories are discussed and analysed at length in Results and Analytical Discussion Section 2.1 |

| Strand Bias at Selected Base Pairs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Strand Bias | A-to-G> | T-to-G> | G-to-A> | G-to-T> | ||

| Cancer | A>>T | G>>C | T-to-C | A-to-C | C-to-T | C-to-A |

| Billiary-AdenoCA | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | + | ++ |

| Bladder-TCC | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ |

| Breast-Cancer | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| CNS-GBM | ++ | +++ | +++ | + | +++ | +++ |

| CNS-Medullo | + | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ |

| ColoRect-AdenoCA | RNS | +++ | R+ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| ESCC | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Eso-AdenoCA | NS | +++ | NS | ++ | NS | +++ |

| Head-SCC | +++ | +++ | +++ | NS | +++ | +++ |

| Liver-HCC | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Lung-AdenoCA | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | NS | +++ |

| Lung-SCC | +++ | +++ | +++ | R++ | +++ | +++ |

| Lymph-BNHL | NS | +++ | NS | + | +++ | +++ |

| Lymph-CLL | +++ | + | +++ | +++ | ++ | + |

| Panc-AdenoCA | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | + | +++ |

| Prost-AdenoCA | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | NS | +++ |

| Skin-Melanoma | R++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ |

| Stomach-AdenoCA | NS | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | +++ |

| Uterus-AdenoCA | R+++ | ++ | + | +++ | NS | + |

| Transcriptional Strand Asymmetry | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deduced Deamination | Inferred Cause of Transcriptional Strand Asymmetry | Inferred Cause of T-to-C>A-to-G at Collapsed R Loops † | ||

| DNA | RNA | |||

| COSMIC SBS | C-to-U | A-to-I | ||

| SBS5 | AID/APOBEC | ADAR (+Hx) | TSRT | ADAR (Hx) |

| SBS1 | AID/APOBEC | TSRT | ||

| SBS2/SBS13 | AID/APOBEC | |||

| SBS3 | AID/APOBEC | ADAR | TSRT, TCR | |

| SBS4 | TCR | |||

| SBS6 | AID/APOBEC | |||

| SBS7a, SBS7b | AID/APOBEC | TCR | ||

| SBS7c, SBS7d | ADAR (+Hx) | ADAR (Hx) | ||

| SBS8 | TCR | |||

| SBS9 | AID/APOBEC | ADAR (+Hx) | TSRT | ADAR (Hx) |

| SBS10a,b SBS14 | AID/APOBEC | |||

| SBS11 | AID/APOBEC | TSRT | ||

| SBS12 | AID/APOBEC | ADAR | TSRT | |

| SBS15 | AID/APOBEC | |||

| SBS16 | ADAR | TSRT | ||

| SBS17a, SBS17b | ADAR (+Hx) | ADAR (Hx) | ||

| SBS18 | TSRT | |||

| SBS19 | AID/APOBEC | TSRT | ||

| SBS84 | AID/APOBEC | |||

| SBS85 | ADAR (+Hx) | ADAR (Hx) | ||

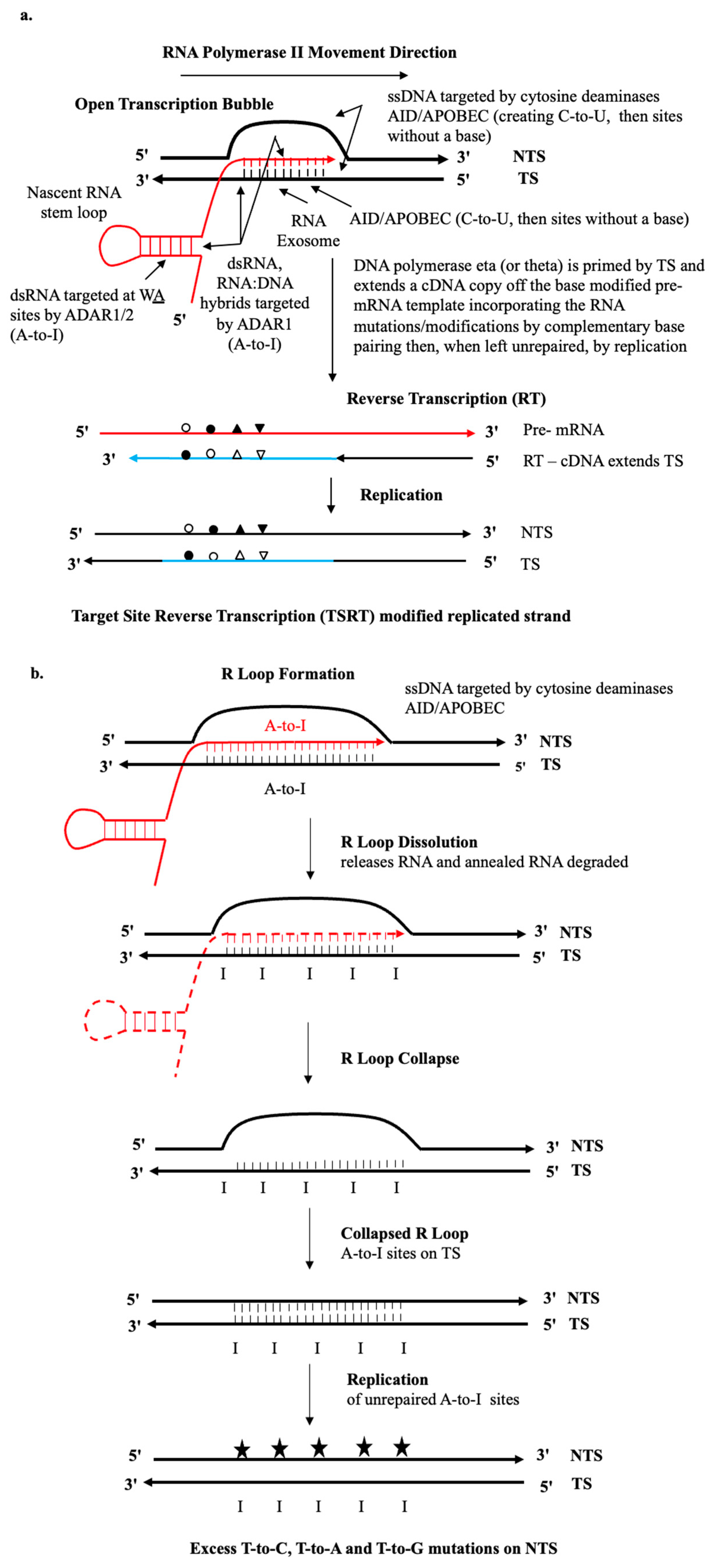

1.1. AID/APOBEC and ADAR Ig SHM-like Dysregulated Mutagenesis

1.2. Lagging and Leading Strands of the Replication Forks

1.3. Stalled Transcription Bubbles in RNA Pol II Transcribed Regions

1.4. Long R-Loops in RNA Pol II Transcribed Regions

1.5. Biochemistry of RNA Templated DNA Repair

1.6. The RNA Tether Model

1.7. Non-B Lymphocyte Immunoglobulin

2. Results of Critical Analysis of Transcriptional Strand-Bias: Implications for SBS Origins

2.1. Strong Evidence for DRT Origin of Many SBS Signatures

2.1.1. Origins SBS5

2.1.2. Origin SBS1

2.1.3. Origin SBS2/SBS13 (See Figure 4)

2.1.4. Origin SBS3

2.1.5. Origin SBS4

2.1.6. Origin SBS6

2.1.7. Origin SBS7a, SBS7b and SBS7c, SBS7d

2.1.8. Origin SBS8

2.1.9. Origins SBS9

2.1.10. Origin SBS10a, SBS10b, SBS14

2.1.11. Origin SBS11

2.1.12. Origin SBS12

2.1.13. Origin SBS15

2.1.14. Origin SBS16

2.1.15. Origin SBS17a, SBS17b

2.1.16. Origin SBS18

2.1.17. Origin SBS19

2.1.18. Origin SBS84, SBS85

2.1.19. SBS Signatures SBS20 Through SBS 44 (as [11])

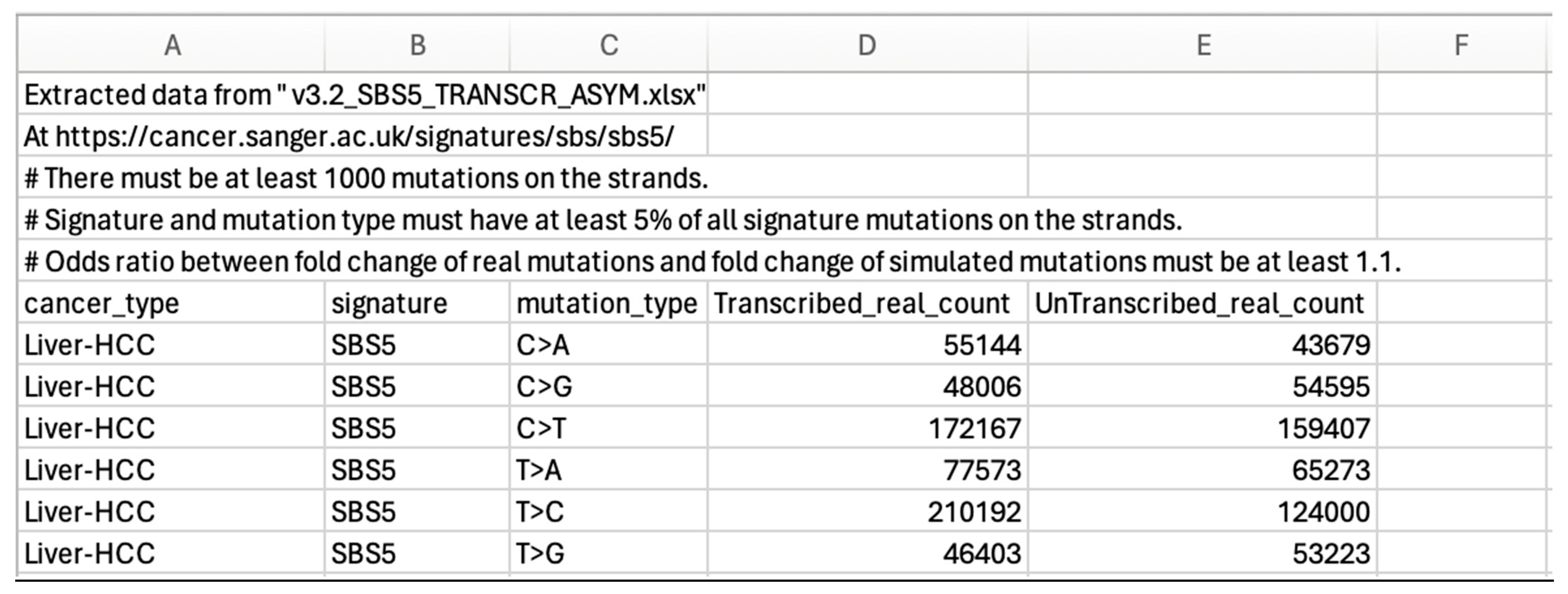

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Cancer Genome Sequence Source Data

3.2. Conversion of Transcriptional Strand Asymmetry SBS Somatic Mutation Numbers at the COSMIC Site to “Types of Mutation” Tables

3.2.1. Step One of Conversion

3.2.2. Step Two of Conversion

3.2.3. Step Three of Conversion

4. Summary and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Pecori, R.; Di Giorgio, S.; Lorenzo, J.P.; Papavasiliou, F.N. Functions and consequences of AID/APOBEC-mediated DNA and RNA deamination. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2022, 23, 505–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, M.G.; Flath, B.; Chelico, L. The interesting relationship between APOBEC3 deoxycytidine deaminases and cancer: A long road ahead. Open Biol. 2020, 10, 200188. [Google Scholar]

- Lindley, R.A. The importance of codon context for understanding the Ig-like somatic hypermutation strand-biased patterns in TP53 mutations in breast cancer. Cancer Genet. 2013, 206, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindley, R.A.; Hall, N.E. APOBEC and ADAR deaminases may cause many single nucleotide polymorphisms curated in the OMIM database. Mutat. Res. 2018, 810, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindley, R.A. Review of the mutational role of deaminases and the generation of a cognate molecular model to explain cancer mutation spectra. Med. Res. Arch. 2020, 8, 2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamrot, J.; Hall, N.E.; Lindley, R.A. Predicting clinical outcomes using cancer progression associated signatures. Oncotarget 2021, 12, 845–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, E.J.; Franklin, A. Lindley RA Somatic mutation patterns at Ig and Non-Ig Loci. DNA Repair 2024, 133, 103607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindley, R.A.; Humbert, P.; Larner, C.; Akmeenmana, E.H.; Pendlebury, C.R.R. Association between targeted somatic mutation (TSM) signatures and HGS-OvCa progression. Cancer Med. 2016, 5, 2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, E.J. Mechanism of somatic hypermutation: Critical analysis of strand biased mutation signatures at A:T and G:C base pairs. Mol. Immunol. 2009, 46, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrov, L.B.; Nik-Zainal, S.; Wedge, D.C.; Aparicio, S.A.J.R.; Behjati, S.; Bjankin, A.V.; Bignell, G.R.; Bolli, N.; Borg, A.; Borresen-Dale, A.-L.; et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature 2013, 500, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrov, L.B.; Kim, J.; Haradhvala, N.J.; Huang, M.N.; Ng, A.W.T.; Wu, Y.; Boot, A.; Covington, K.R.; Gordenin, D.A.; Bergstrom, E.N.; et al. The repertoire of mutational signatures in human cancer. Nature 2020, 578, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otlu, B.; Diaz-Gay, M.; Vernes, I.; Bergstrom, E.N.; Zhivagui, M.; Barnes, M.; Alexandrov, L.B. Topography of mutational signatures in human cancer. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 112930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steele, E.J.; Lindley, R.A. Somatic mutation patterns in non-lymphoid cancers resemble the strand biased somatic hypermutation spectra of antibody genes. DNA Repair 2010, 9, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindley, R.A.; Steele, E.J. Critical analysis of strand-biased somatic mutation signatures in TP53 versus Ig genes, in genome-wide data and the etiology of cancer. ISRN Genom. 2013, 2013, 921418. [Google Scholar]

- Kuraoka, I.; Endou, M.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Wada, T.; Handa, H.; Tanaka, K. Effects of endogenous DNA base lesions on transcription elongation by mammalian RNA polymerase II. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 7294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, U.; Meng, F.-L.; Keim, C.; Grinstein, V.; Pefanus, E.; Eccleston, J.; Zhang, T.; Myers, D.; Wasserman, C.R.; Wesemann, D.R.; et al. The RNA exosome targets the AID cytidine deaminase to both strands of transcribed duplex DNA substrates. Cell 2011, 144, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karijolich, J.; Yi, C.; Yu, Y.-T. Transcriptome-wide dynamics of RNA pseudouridylation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2015, 16, 581–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.I.; Clark, W.C.; Pan, D.W.; Eckwahl, M.J.; Dai, Q.; Pan, T. Pseudouridines have context-dependent mutation and stop rates in high-throughput sequencing. RNA Biol. 2018, 15, 892–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulos, P.G.; Athanasopoulou, K.; Daneva, G.N.; Scorilas, A. The Repertoire of RNA Modifications Orchestrates a Plethora of Cellular Responses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kierzek, E.; Malgowska, M.; Lisowiec, J.; Turner, D.H.; Gdaniec, Z.; Kierzek, R. The contribution of pseudouridine to stabilities and structure of RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 3492–3501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Li, Z. Human polynucleotide phosphorylase reduces oxidative RNA damage and protects HeLa cell against oxidative stress. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 372, 288–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, A.; Steele, E.J.; Lindley, R.A. A proposed reverse transcription mechanism for (CAG)n and similar expandable repeats that cause neurological and other diseases. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luan, D.D.; Korman, M.H.; Jakubczak, J.L.; Eichbush, T.H. Reverse transcription of R2B mRNA is primed by a nick at the chromosomal target site: A mechanism for non-LTR retrotransposition. Cell 1993, 72, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiromoto, Y.; Sakurai, M.; Minakuchi, M.; Ariyoshi, K.; Nishikura, K. ADAR1 RNA editing enzyme regulates R-loop formation and genome stability at telomeres in cancer cells. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayona-Feliu, A.; Herrera-Moyano, E.; Badra-Fajardo, N.; Galvan-Femenia, I.; Soler-Oliva, E.; Aguilera, A. The chromatin network helps prevent cancer-associated mutagenesis at transcription-replication conflicts. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoy, H.; Zwicky, K.; Kuster, D.; Lang, K.S.; Krietsch, J.; Crossley, M.P.; Schmid, J.A.; Cimprich, K.A.; Merrikh, H.; Lopes, M. Direct visualization of transcription-replication conflicts reveals post-replicative DNA:RNA hybrids. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2023, 30, 348–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, E.J.; Lindley, R.A.; Wen, J.; Weiller, G.F. Computational analyses show A-to-G mutations correlate with nascent mRNA hairpins at somatic hypermutation hotspots. DNA Repair 2006, 5, 1346–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, A.; Steele, E.J. RNA-directed DNA repair and antibody somatic hypermutation. Trends Genet. 2022, 38, 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoggins, J.W.; Rice, C.M. Interferon-stimulated genes and their antiviral effector functions. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2011, 1, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyzos, A.A.; McMurray, C.T. Close encounters: Moving along bumps, breaks, and bubbles on expanded trinucleotide tracts. DNA Repair 2017, 56, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, S.; Nagel, G.; Eshkind, L.; Neurath, M.F.; Samson, L.D.; Kaina, B. Both base excision repair and O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase protect against methylation-induced colon carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis 2010, 31, 2111–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krokan, H.E.; Bjoras, M. Base excision repair. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013, 5, a012583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamrot, J.; Balachandran, S.; Steele, E.J.; Lindley, R.A. Molecular model linking Th2 polarized M2 tumour-associated macrophages with deaminase-mediated cancer progression mutation signatures. Scand. J. Immunol. 2019, 89, e12760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Wang, X.; Wu, Y.; Xu, B.; Zhao, T.; Trapp, C.; Wang, X.; Unger, K.; Zhou, C.; Lu, S.; et al. APOBEC-mediated mutagenesis is a favorable predictor of prognosis and immunotherapy for bladder cancer patients: Evidence from pan-cancer analysis and multiple databases. Theranostics 2022, 12, 4181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.C.; Lorenzo, C.; Beal, P.A. DNA Editing in DNA/RNA hybrids by adenosine deaminases that act on RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 3369–3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milano, L.; Gautam, A.; Caldecott, K.W. DNA damage and transcription stress. Mol. Cell 2024, 84, 70. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S.; Patnaik, S.K.; Taggart, R.T.; Kannisto, E.D.; Enriques, S.M.; Gollnick, P.; Baysal, B.E. APOBEC3A cytidine deaminase induces RNA editing in monocytes and macrophages. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Patnaik, S.K.; Kemer, Z.; Baysal, B.E. Transient overexpression of exogenous APOBEC3A causes C-to-U RNA editing of thousands of genes. RNA Biol. 2016, 14, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, N.; Sheridan, R.M.; Ramachandran, S.; Bentley, D.L. The pausing zone and control of RNA polymerase II elongation by Spt5: Implications for the pause-release model. Mol. Cell 2022, 82, 3632–3645.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasakis, R.N.; Laganà, A.; Stamkopoulou, D.; Melnekoff, D.T.; Nedumaran, P.; Leshchenko, V.; Pecori, R.; Parekh, S.; Papavasiliou, F.N. ADAR1 can drive Multiple Myeloma progression by acting both as an RNA editor of specific transcripts and as a DNA mutator of their cognate genes. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, J.L.; Cristini, A.; Law, E.K.; Lee, S.Y.; Tellier, M.; Carpenter, M.A.; Beghe, C.; Sanchez, A.; Jarvis, M.C.; Stefanovska, B.; et al. APOBEC3B regulates R-loops and promotes transcription-associated mutagenesis in cancer. Nat. Genet. 2023, 55, 1721–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menendez, D.; Nguyen, T.-A.; Snipe, J.; Resnick, M.A. The Cytidine Deaminase APOBEC3 Family Is Subject to Transcriptional Regulation by p53. Mol. Cancer Res. 2017, 15, 735–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storici, F.; Bebenek, K.; Kunkel, T.A.; Gordenin, D.A.; Resnick, M.A. RNA-templated DNA repair. Nature 2007, 447, 338–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskin, H.; Shen, Y.; Huang, F.; Patel, M.; Yang, T.; Ashley, K.; Mazin, A.V.; Storici, F. Transcript-RNA-templated DNA recombination and repair. Nature 2014, 515, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meers, C.; Keskin, H.; Banyai, G.; Mazina, O.; Yang, T.; Gombolay, A.L.; Mukherjee, K.; Kaparos, R.; Kaparos, E.I.; Newman, G.; et al. Genetic characterization of three distinct mechanisms sup-porting RNA-driven DNA repair and modification reveals major role of DNA polymerase. Mol. Cell 2020, 79, 1037.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayle, R.; Holloman, W.K.; O’Donnell, M.E. DNA polymerase ζ has robust reverse transcriptase activity relative to other cellular DNA polymerases. J. Biol. Chem. 2024, 300, 107918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charaborty, A.; Tapryal, N.; Venkova, T.; Horikoshi, N.; Pandita, R.K.; Sarker, A.H.; Sarkar, P.S.; Pandita, T.K.; Hazra, T.K. Classical non-homologous end-joining pathway utilizes nascent RNA for error-free double-strand break repair of transcribed genes. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, A.; Tapryal, N.; Venkova, T.; Mitra, J.; Vasquez, V.; Sarker, A.H.; Duarte-Silva, S.; Huai, W.; Ashizawa, T.; Ghosh, G.; et al. Deficiency in classical nonhomologous end-joining-mediated repair of transcribed genes is linked to SCA3 pathogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 8154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A.; Tapryal, N.; Islam, A.; Sarker, A.H.; Manohar, K.; Mitra, J.; Hegde, M.L.; Hazra, T. Human DNA polymerase η promotes RNA-templated error-free repair of DNA double-strand breaks. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299, 102991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, A.; Milburn, P.J.; Blanden, R.V.; Steele, E.J. Human DNA polymerase-h(eta), an A-T mutator in somatic hypermutation of rearranged immunoglobulin genes, is a reverse transcriptase. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2004, 82, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieber, M.R. Mechanisms of human lymphoid chromosomal translocations. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2016, 16, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Hsieh, C.-L.; Lieber, M.R. The RNA tether model for human chromosomal translocation fragile zones. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2024, 49, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steele, E.J. Somatic hypermutation in immunity and cancer: Critical analysis of strand-biased and codon-context mutation signatures. DNA Repair 2016, 45, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senigl, F.; Maman, Y.; Dinesh, R.K.; Alinikula, J.; Seth, R.B.; Pecnova, L.; Omer, A.D.; Rao, S.S.P.; Weisz, D.; Buerstedde, J.-M.; et al. Topologically Associated Domains Delineate Susceptibility to Somatic Hypermutation. Cell Rep. 2019, 29, 3902–3915.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, M.; Huang, J.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Q.; Liao, Q.; Qiu, X. Immunoglobulin Expression in Cancer Cells and Its Critical Roles in Tumorigenesis. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 613530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Peng, H.; Gao, J.; Nong, A.; Hua, H.; Yang, S.; Chen, L.; Wu, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J. Current insights into the expression and functions of tumor-derived immunoglobulins. Cell Death Discov. 2021, 7, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G. RP215 and GHR106 Monoclonal Antibodies and Potential Therapeutic Applications. Open J. Immunol. 2023, 13, 61–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Huang, J.; Mao, Y.; Liu, S.; Sun, X.; Zhu, X.; Ma, T.; Zhang, L.; Ji, J.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Immunoglobulin gene transcripts have distinct VHDJH recombination characteristics in human epithelial cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 13610–13619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spisak, N.; de Manuel, M.; Milligan, W.; Sella, G.; Przeworski, M. The clock-like accumulation of germline and somatic mutations can arise from the interplay of DNA damage and repair. PLoS Biol. 2024, 22, e3002678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bass, B.L. RNA editing by adenosine deaminases that act on RNA. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2002, 71, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, G.; Hwang, S.; Yu, K.; Kang, J.Y.; Kang, C.; Hohng, S. Translocating RNA polymerase generates R-loops at DNA double-strand breaks without any additional factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, 9838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimeno, S.; Prados-Carvaja, L.R.; Fernandez-Avila, M.J.; Silvia, S.; Silvestris, D.A.; Endara-Coll, M.; Rogriguez-Real, G.; Domingo-Prim, J.; Mejias-Navarro, F.; Romero-Franco, A.; et al. ADAR-mediated RNA editing of DNA:RNA hybrids is required for DNA double strand break repair. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, F.; Fu, Y.; Kao, S.A.; Yang, H.; Chen, X.S. Family-Wide Comparative Analysis of Cytidine and Methylcytidine Deamination by Eleven Human APOBEC Proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 2017, 429, 1787–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petljak, M.; Dananberg, A.; Chu, K.; Bergstrom, E.N.; Striepen, J.; von Morgen, P.; Chen, Y.; Shah, H.; Sale, J.E.; Alexandrov, L.B.; et al. Mechanisms of APOBEC3 mutagenesis in human cancer cells. Nature 2022, 607, 799–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamborszky, J.; Szikriszt, B.; Gervai, J.Z.; Pipek, O.; Poti, A.; Krzystanek, M.; Ribli, D.; Szalai-Gindi, J.M.; Csabai, I.; Szallasi, Z.; et al. Loss of BRCA1 or BRCA2 markedly increases the rate of base substitution mutagenesis and has distinct effects on genomic deletions. Oncogene 2017, 36, 746–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandramouly, G.; Zhao, J.; McDevitt, S.; Rusanov, T.; Hoang, T.; Borisonnik, N.; Treddinick, T.; Lopezcolorado, F.W.; Kent, T.; Siddique, L.A.; et al. Polθ reverse transcribes RNA and promotes RNA-templated DNA repair. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabf1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.; Gervai, J.Z.; Poti, A.; Nemeth, E.; Szeltner, Z.; Szikriszt, B.; Gyure, Z.; Zamborsky, J.; Ceccon, M.; di Fagagna, F. d’A.; et al. BRCA1 deficiency specific base substitution mutagenesis is dependent on translesion synthesis and regulated by 53BP1. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Egli, M.; Guengerich, F.P. Human DNA polymerase η accommodates RNA for strand extension. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 18044–18051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Ghodke, P.P.; Egli, M.; Li, L.; Wang, Y.; Guengerich, F.P. Human DNA polymerase η has reverse transcriptase activity in cellular environments. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 6073–6081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanawalt, P.C.; Spivak, G. Transcriptional-coupled DNA repair: Two decades of progress and surprises. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 958–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denissenko, M.F.; Pao, A.; Tang, M.-S.; Pfeifer, G.P. Preferential formation of Benzo[a]pyrene adducts at lung cancer mutational hotspots in P53. Science 1996, 274, 430–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denissenko, M.F.; Pao, A.; Pfeifer, G.P.; Tang, M.-S. Slow repair of bulky DNA adducts along the nontranscribed strand of the human p53 gene may explain the strand bias of transversion mutations in cancers. Oncogene 1998, 16, 1241–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, S.-G.; Pettinga, D.; Johnson, J.; Li, P.; Pfeifer, G.P. The major mechanism of melanoma mutations is based on deamination of cytosine in pyrimidine dimers as determined by circle damage sequencing. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabi6508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neil, S.; Bieniasz, P. Human Immunodeficiency Virus, Restriction Factors, and Interferon. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2009, 29, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, M.B.; Temiz, N.A.; Harris, R.S. Evidence for APOBEC3B mutagenesis in multiple human cancers. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 977–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, S.A.; Lawrence, M.S.; Klimczak, L.J.; Grimm, S.A.; Fargo, D.; Stojanov, P.; Kiezun, A.; Kryukov, G.V.; Carter, S.L.; Saksena, G.; et al. An APOBEC cytidine deaminase mutagenesis pattern is widespread in human cancers. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 970–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, K.; A Roberts, S.; Klimczak, L.J.; Sterling, J.F.; Saini, N.; Malc, E.P.; Kim, J.; Kwiatkowski, D.J.; Fargo, D.C.; A Mieczkowski, P.; et al. An APOBEC3A hypermutation signature is distinguishable from the signature of background mutagenesis by APOBEC3B in human cancers. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 1067–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, M.R.; Davis, S.; Noonan, F.P.; Graff-Cherry, C.; Hawley, T.S.; Walker, R.; Feigenbaum, L.; Fuchs, E.; Lyakh, L.; Young, H.A.; et al. Interferon-g links ultraviolet radiation to melanomagenesis in mice. Nature 2011, 469, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, T.H.; Lin, C.H.; Qi, L.; Fei, J.; Li, Y.; Yong, K.J.; Liu, M.; Song, Y.; Chow, R.K.K.; Ng, V.H.E.; et al. A disrupted RNA editing balance mediated by ADARs (Adenosine Deaminases that act on RNA) in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut 2014, 63, 832–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindley, R.A.; Steele, E.J. Presumptive Evidence for ADAR1 A-to-I Deamination at WA-sites as the Mutagenic Genomic Driver in Hepatocellular and Related ADAR1-Hi Cancers. J. Carcinog. Mutagen. 2020, 11, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Haradhvala, N.J.; Polak, P.; Stojanov, P.; Covington, K.R.; Shinbrot, E.; Hess, J.M.; Rheinbay, E.; Kim, J.; Maruvka, Y.E.; Braunstein, L.Z.; et al. Mutational strand asymmetries in cancer genomes reveal mechanisms of DNA damage and repair. Cell 2016, 164, 538–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, T.M.; Vaisman, A.; Martomo, S.A.; Sullivan, P.; Lan, L.; Hanaoka, F.; Yasui, A.; Woodgate, R.; Gearhart, P.J. MSH2–MSH6 stimulates DNA polymerase eta, suggesting a role for A:T mutations in antibody genes. J. Exp. Med. 2005, 201, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogozin, I.B.; Pavlov, Y.I.; Bebenek, K.; Matsuda, T.; Kunkel, T.A. Somatic mutation hotspots correlate with DNA polymerase eta error spectrum. Nat. Immunol. 2001, 2, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, X.; Winter, D.B.; Kasmer, C.; Kraemer, K.H.; Lehmann, A.R.; Gearhart, P.J. DNA polymerase η is an A–T mutator in somatic hypermutation of immunoglobulin variable genes. Nat. Immunol. 2001, 2, 537–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorslund, T.; Sunesen, M.; Bohr, V.A.; Stevnsner, T. Repair of 8-oxoG is slower in endogenous nuclear genes than in mitochondrial DNA and is without strand bias. DNA Repair 2002, 1, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, C.J.; Talmane, L.; Luft, J.; Connelly, J.; Nicholson, M.D.; Verburg, J.C.; Pich, O.; Campbell, S.; Giasi, M.; Wei, P.-C.; et al. Strand-resolved mutagenicity of DNA damage and repair. Nature 2024, 630, 744–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, S.J.; Anderson, C.J.; Connor, F.; Pich, O.; Sundaram, V.; Feig, C.; Rayner, T.F.; Luck, M.; Aitken, S.; Luft, J.; et al. Pervasive lesion segregation shapes cancer genome evolution. Nature 2020, 583, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beale, R.C.L.; Petersen-Mahrt, S.K.; Watt, I.N.; Harris, R.S.; Rada, C.; Neuberger, M.S. Comparison of the different context-dependence of DNA deamination by APOBEC enzymes: Correlation with mutation spectra in vivo. J. Mol. Biol. 2004, 337, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, M.W.; Browne, M.; Langville, A.N.; Pauca, V.P.; Plemmons, R.J. Algorithms and applications for approximate nonnegative matrix factorization. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2007, 52, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, K.N.; Holmes, R.K.; Sheehy, A.M.; Davidson, N.O.; Cho, S.J.; Malim, M.H. Cytidine deamination of retroviral DNA by diverse APOBEC proteins. Curr. Biol. 2004, 4, 1392–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanc, V.; Davidson, N.O. C-to-U RNA Editing: Mechanisms leading to genetic diversity. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 1395–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buisson, R.; Langenbucher, A.; Bowen, D.; Kwan, E.E.; Benes, C.H.; Zou, L.; Lawrence, M.S. Passenger hotspot mutations in cancer driven by APOBEC3A and mesoscale genomic features. Science 2019, 364, eaaw2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, M.B.; Lackey, L.; Carpenter, M.A.; Rathore, A.; Land, A.M.; Leonard, B.; Refsland, E.W.; Kotandeniya, D.; Tretyakova, N.; Nikas, J.B.; et al. APOBEC3B is an enzymatic source of mutation in breast cancer. Nature 2013, 494, 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, Y.; Wang, X.; Esselman, W.J.; Zheng, Y.-H. Identification of APOBEC3-DE as another antiretroviral factor from the Human APOBEC Family. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 10522–10533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewa, B.; Danuta, M.-S. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and PAH-related DNA adducts. J. Appl. Genet. 2017, 58, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guttenplan, J.B.; Kosinska, W.; Zhao, Z.-L.; Chen, K.-M.; Aliaga, C.; DelTondo, J.; Cooper, T.; Sun, Y.-W.; Zhang, S.-M.; Jiang, K.; et al. Mutagenesis and carcinogenesis induced by dibenzo[a,l]pyrene in the mouse oral cavity: A potential new model for oral cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2012, 130, 2783–2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hache’, G.; Liddament, M.T.; Harris, R.S. The retroviral hypermutation specificity of APOBEC3F and APOBEC3G is governed by the C-terminal DNA Cytosine deaminase domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 10920–10924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harari, A.; Ooms, M.; Mulder, L.C.; Simon, V. Polymorphisms and splice variants influence the antiretroviral activity of human APOBEC3H. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, M.; Guetard, D.; Suspene, R.; Rusniok, C.; Wain-Hobson, S.; Vartanian, J.-P. Genetic editing of HBV DNA by monodomain human APOBEC3 cytidine deaminases and the recombinant nature of APOBEC3G. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e4277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, C.; Russu, I.M. Dynamics and stability of individual base pairs in two homologous RNA-DNA hybrids. Biochemistry 2009, 48, 3988–3997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonard, B.; Hart, S.N.; Burns, M.B.; Carpenter, M.A.; Temiz, N.A.; Rathore, A.; Vogel, R.I.; Nikas, J.B.; Law, E.K.; Brown, W.L.; et al. APOBEC3B upregulation and genomic mutation patterns in serous ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 7222–7231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liddament, M.T.; Brown, W.L.; Schumacher, A.J.; Harris, R.S. APOBEC3F properties and hypermutation preferences indicate activity against HIV-1 in vivo. Curr. Biol. 2004, 14, 1385–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindley, R.A.; Steele, E.J. Deaminases and Why Mice Sometimes Lie in Immuno-Oncology Pre-Clinical Trials? Ann. Clin. Oncol. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logue, E.C.; Bloch, N.; Dhuey, E.; Zhang, R.; Cao, P.; Herate, C.; Chauveau, L.; Hubbard, S.R.; Landau, N.R. A DNA sequence recognition loop on APOBEC3A controls substrate specificity. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e97062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malvezzi, S.; Farnung, L.; Aloisi, C.M.N.; Angelov, T.; Cramer, P.; Sturla, S.J. Mechanism of RNA polymerase II stalling by DNA alkylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 12172–12177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mertz, T.M.; Harcy, V.; Roberts, S.A. Risks at the DNA Replication Fork: Effects upon Carcinogenesis and Tumor Heterogeneity. Genes 2017, 8, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, B.R.; Hamilton, C.E.; Mwangi, M.M.; Dewell, S.; Papavasiliou, F.N. Transcriptome-wide sequencing reveals numerous APOBEC1 mRNA editing targets in transcript 3′ UTRs. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2011, 18, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, A.; Ortega, P.; Sakhtemani, R.; Manjunath, L.; Oh, S.; Bournique, E.; Becker, A.; Kim, K.; Durfee, C.; Temiz, N.A.; et al. Mesoscale DNA features impact APOBEC3A and APOBEC3B deaminase activity and shape tumor mutational landscapes. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seplyarskiy, V.B.; Soldatov, R.A.; Popadin, K.Y.; Antonarakis, S.E.; Bazykin, G.A.; Nikolaev, S.I. APOBEC-induced mutations in human cancers are strongly enriched on the lagging DNA strand during replication. Genome Res. 2016, 26, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sowden, M.; Hamm, J.K.; Smith, H.C. Overexpression of APOBEC-1 results in mooring sequence-dependent promiscuous RNA editing. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 3011–3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swann, P.F. Why do O6-alkylguanine and O4-alkylthymine miscode? The relationship between the structure of DNA containing O6-alkylguanine and O4-alkylthymine and the mutagenic properties of these bases. Mutat. Res. 1990, 233, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, B.J.M.; Nik-Zainal, S.; Wu, Y.L.; Stebbings, L.A.; Raine, K.; Campbell, P.J.; Rad, C.; Stratton, M.R.; Neuberger, M.S. DNA deaminases induce break-associated mutation showers with implication of APOBEC3B and 3A in breast cancer kataegis. eLife 2013, 2, e00534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiegand, H.L.; Doehle, B.P.; Bogerd, H.P.; Cullen, B.R. A second human antiretroviral factor, APOBEC3F, is suppressed by the HIV-1 and HIV-2 Vif proteins. EMBO J. 2004, 23, 2451–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Chen, D.; Konig, R.; Mariani, R.; Unutmaz, D.; Landau, N.R. APOBEC3B and APOBEC3C are potent inhibitors of simian immunodeficiency virus replication. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 53379–53386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Steele, E.J.; Lindley, R.A. Deaminase-Driven Reverse Transcription Mutagenesis in Oncogenesis: Critical Analysis of Transcriptional Strand Asymmetries of Single Base Substitution Signatures. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 989. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26030989

Steele EJ, Lindley RA. Deaminase-Driven Reverse Transcription Mutagenesis in Oncogenesis: Critical Analysis of Transcriptional Strand Asymmetries of Single Base Substitution Signatures. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(3):989. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26030989

Chicago/Turabian StyleSteele, Edward J., and Robyn A. Lindley. 2025. "Deaminase-Driven Reverse Transcription Mutagenesis in Oncogenesis: Critical Analysis of Transcriptional Strand Asymmetries of Single Base Substitution Signatures" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 3: 989. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26030989

APA StyleSteele, E. J., & Lindley, R. A. (2025). Deaminase-Driven Reverse Transcription Mutagenesis in Oncogenesis: Critical Analysis of Transcriptional Strand Asymmetries of Single Base Substitution Signatures. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(3), 989. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26030989