A Mitochondrial Supplement Improves Function and Mitochondrial Activity in Autism: A Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Cross-Over Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Participants

2.2. Mitochondrial Enzymology

2.3. Mitochondrial Respirometry

2.4. Behavioral and Cognitive Outcomes

2.5. Responder Analysis

2.6. Adverse Events

3. Discussion

3.1. Targeted Supplementation Improves Mitochondrial Function

3.2. Targeted Mitochondrial Supplementation Improves Core ASD Symptoms

3.3. Comparing to Other Treatment Studies

3.4. The Importance of Treating Mitochondrial Abnormalities in Neurodevelopmental Disorders

3.5. Limitations

4. Materials and Methods

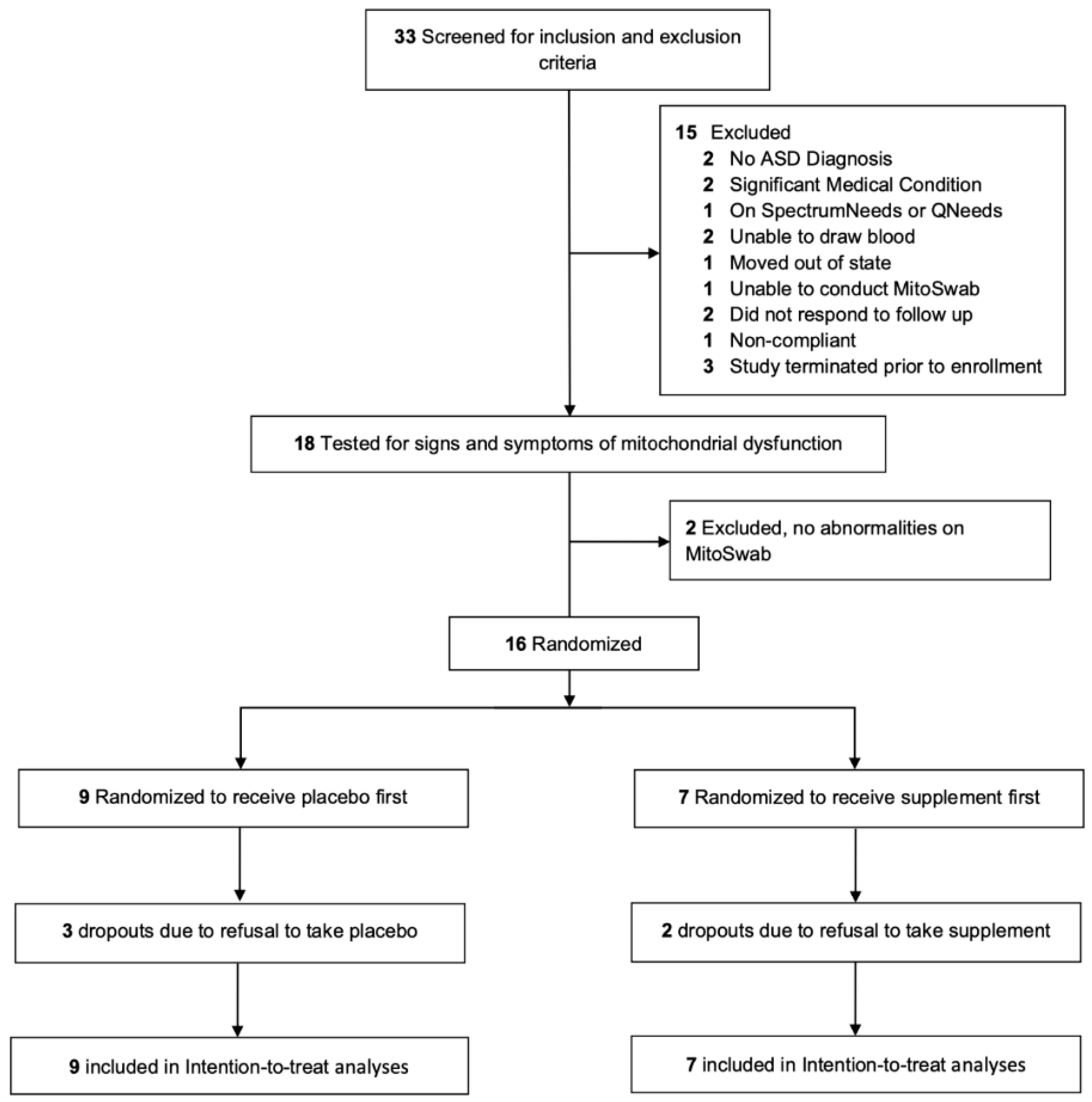

4.1. Study Design

4.2. Randomization

4.3. Study Procedure

4.4. Intervention

- Niacin is at about the UL. Niacinamide (also known as nicotinamide), the form of niacin in SpectrumNeeds®, does not cause flushing.

- Folate exceeds the UL. However, the UL only applied to synthetic folate, also known as folic acid. There is no known UL for non-synthetic folate, which is the type of folate used in SpectrumNeeds®. Half of the total folate is microbial sourced (6S)-5-Methyltetrahydrofolic acid Glucosamine salt. Half is calcium folinate, which is about one-half the dose recommended for pregnant women with a prior child born with a neural tube defect and one half to one-twenty-fifth the dosing given to children with ASD and suspected cerebral folate deficiency. These dosages are known to be generally well tolerated in ASD children [25].

4.5. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

4.6. Behavioral and Developmental Outcome Measures

4.6.1. Clinician Rated Measures

4.6.2. Psychometrician Rated Scales

4.6.3. Parent Rated Scales

4.7. Establishment and Maintenance of Assessment Fidelity

4.8. Adverse Effect Monitoring

4.9. Measures of Mitochondrial Enzymology

4.10. Measures of Mitochondrial Respiration

4.11. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zablotsky, B.; Black, L.I.; Maenner, M.J.; Schieve, L.A.; Blumberg, S.J. Estimated Prevalence of Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities Following Questionnaire Changes in the 2014 National Health Interview Survey. Natl. Health Stat. Rep. 2015, 87, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Rossignol, D.A.; Frye, R.E. A review of research trends in physiological abnormalities in autism spectrum disorders: Immune dysregulation, inflammation, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and environmental toxicant exposures. Mol. Psychiatry 2012, 17, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frye, R.E.; Slattery, J.; Delhey, L.; Furgerson, B.; Strickland, T.; Tippett, M.; Sailey, A.; Wynne, R.; Rose, S.; Melnyk, S.; et al. Folinic acid improves verbal communication in children with autism and language impairment: A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Mol. Psychiatry 2018, 23, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frye, R.E.; Rossignol, D.A. Identification and Treatment of Pathophysiological Comorbidities of Autism Spectrum Disorder to Achieve Optimal Outcomes. Clin. Med. Insights Pediatr. 2016, 10, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frye, R.E.; Rincon, N.; McCarty, P.J.; Brister, D.; Scheck, A.C.; Rossignol, D.A. Biomarkers of mitochondrial dysfunction in autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurobiol. Dis. 2024, 197, 106520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossignol, D.A.; Frye, R.E. Mitochondrial dysfunction in autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol. Psychiatry 2012, 17, 290–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frye, R.E.; McCarty, P.J.; Werner, B.A.; Rose, S.; Scheck, A.C. Bioenergetic signatures of neurodevelopmental regression. Front. Physiol. 2024, 15, 1306038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, S.; Frye, R.E.; Slattery, J.; Wynne, R.; Tippett, M.; Pavliv, O.; Melnyk, S.; James, S.J. Oxidative stress induces mitochondrial dysfunction in a subset of autism lymphoblastoid cell lines in a well-matched case control cohort. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e85436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geier, D.A.; Kern, J.K.; Davis, G.; King, P.G.; Adams, J.B.; Young, J.L.; Geier, M.R. A prospective double-blind, randomized clinical trial of levocarnitine to treat autism spectrum disorders. Med. Sci. Monit. 2011, 17, PI15–PI23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahmy, S.F.; El-Hamamsy, M.H.; Zaki, O.K.; Badary, O.A. l-Carnitine supplementation improves the behavioral symptoms in autistic children. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2013, 7, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, M.; Parmoon, Z.; Farahmand, Y.; Moradi, A.; Farahmand, K.; Moradi, K.; Basti, F.A.; Mohammadi, M.-R.; Akhondzadeh, S. l-carnitine adjunct to risperidone for treatment of autism spectrum disorder-associated behaviors: A randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2024, 39, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakibaei, F.; Jelvani, D. Effect of Adding l -Carnitine to Risperidone on Behavioral, Cognitive, Social, and Physical Symptoms in Children and Adolescents with Autism: A Randomized Double-Blinded Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 2023, 46, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goin-Kochel, R.P.; Scaglia, F.; Schaaf, C.P.; Berry, L.N.; Dang, D.; Nowel, K.P.; Laakman, A.L.; Dowell, L.R.; Minard, C.G.; Loh, A.; et al. Side Effects and Behavioral Outcomes Following High-Dose Carnitine Supplementation Among Young Males with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Pilot Study. Glob. Pediatr. Health 2019, 6, 2333794X19830696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedenfeld, S.; Hamada, K.; Audhya, T.; Adams, J. Biochemical Effects of Ribose and NADH Therapy in Children with Autism. Autism Insights 2011, 3, 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Gvozdjakova, A.; Kucharská, J.; Ostatníková, D.; Babinská, K.; Nakládal, D.; Crane, F.L. Ubiquinol improves symptoms in children with autism. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2014, 2014, 798957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mousavinejad, E.; Ghaffari, M.A.; Riahi, F.; Hajmohammadi, M.; Tiznobeyk, Z.; Mousavinejad, M. Coenzyme Q10 supplementation reduces oxidative stress and decreases antioxidant enzyme activity in children with autism spectrum disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 265, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonsdale, D.; Shamberger, R.J.; Audhya, T. Treatment of autism spectrum children with thiamine tetrahydrofurfuryl disulfide: A pilot study. Neuro Endocrinol. Lett. 2002, 23, 303–308. [Google Scholar]

- Legido, A.; Goldenthal, M.; Garvin, B.; Damle, S.; Corrigan, K.; Connell, J.; Thao, D.; Valencia, I.; Melvin, J.; Khurana, D.; et al. Effect of a Combination of Carnitine, Coenzyme Q10 and Alpha-Lipoic Acid (MitoCocktail) on Mitochondrial Function and Neurobehavioral Performance in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (P3.313). Neurology 2018, 90, P3-313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennuri, S.C.; Rose, S.; Frye, R.E. Mitochondrial Dysfunction Is Inducible in Lymphoblastoid Cell Lines from Children with Autism and May Involve the TORC1 Pathway. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frye, R.E.; Cakir, J.; Rose, S.; Delhey, L.; Bennuri, S.C.; Tippett, M.; Melnyk, S.; James, S.J.; Palmer, R.F.; Austin, C.; et al. Prenatal air pollution influences neurodevelopment and behavior in autism spectrum disorder by modulating mitochondrial physiology. Mol. Psychiatry 2020, 26, 1561–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frye, R.E.; Cakir, J.; Rose, S.; Delhey, L.; Bennuri, S.C.; Tippett, M.; Palmer, R.F.; Austin, C.; Curtin, P.; Arora, M. Early life metal exposure dysregulates cellular bioenergetics in children with regressive autism spectrum disorder. Transl. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, J.B.; Audhya, T.; McDonough-Means, S.; Rubin, R.A.; Quig, D.; Geis, E.; Gehn, E.; Loresto, M.; Mitchell, J.; Atwood, S.; et al. Effect of a vitamin/mineral supplement on children and adults with autism. BMC Pediatr. 2011, 11, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napoli, E.; Wong, S.; Hertz-Picciotto, I.; Giulivi, C. Deficits in bioenergetics and impaired immune response in granulocytes from children with autism. Pediatrics 2014, 133, e1405–e1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, K.F.; Altman, D.G.; Moher, D. CONSORT 2010 Statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010, 340, c332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossignol, D.A.; Frye, R.E. Cerebral Folate Deficiency, Folate Receptor Alpha Autoantibodies and Leucovorin (Folinic Acid) Treatment in Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.J.; Hwang, J.S.; Shin, A.L.; Kim, J.Y.; Bae, S.M.; Sheehy-Knight, J.; Kim, J.W. Accuracy of the Childhood Autism Rating Scale: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2019, 61, 1030–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busner, J.; Targum, S.D. The clinical global impressions scale: Applying a research tool in clinical practice. Psychiatry 2007, 4, 28–37. [Google Scholar]

- Scahill, L.; Riddle, M.A.; McSwiggin-Hardin, M.; Ort, S.I.; King, R.A.; Goodman, W.K.; Cicchetti, D.; Leckman, J.F. Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale: Reliability and validity. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 1997, 36, 844–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scahill, L.; McDougle, C.J.; Williams, S.K.; Dimitropoulos, A.; Aman, M.G.; McCracken, J.T.; Tierney, E.; Arnold, L.E.; Cronin, P.; Grados, M.; et al. Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale modified for pervasive developmental disorders. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2006, 45, 1114–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scahill, L.; Dimitropoulos, A.; McDougle, C.J.; Aman, M.G.; Feurer, I.D.; McCracken, J.T.; Tierney, E.; Pu, J.; White, S.; Lecavalier, L.; et al. Children’s Yale-Brown obsessive compulsive scale in autism spectrum disorder: Component structure and correlates of symptom checklist. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2014, 53, 97–107.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choque Olsson, N.; Bolte, S. Brief report: “Quick and (not so) dirty” assessment of change in autism: Cross-cultural reliability of the Developmental Disabilities CGAS and the OSU autism CGI. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2014, 44, 1773–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sparrow, S.; Cicchetti, D.; Balla, D. Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, 2nd ed.; Pearson: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pine, E.; Luby, J.; Abbacchi, A.; Constantino, J.N. Quantitative assessment of autistic symptomatology in preschoolers. Autism Int. J. Res. Pract. 2006, 10, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaat, A.J.; Lecavalier, L.; Aman, M.G. Validity of the aberrant behavior checklist in children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2014, 44, 1103–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frye, R.E.; Sequeira, J.M.; Quadros, E.V.; James, S.J.; Rossignol, D.A. Cerebral folate receptor autoantibodies in autism spectrum disorder. Mol. Psychiatry 2013, 18, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scahill, L.; Lecavalier, L.; Schultz, R.T.; Evans, A.N.; Maddox, B.; Pritchett, J.; Herrington, J.; Gillespie, S.; Miller, J.; Amoss, R.T.; et al. Development of the Parent-Rated Anxiety Scale for Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2019, 58, 887–896.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldenthal, M.J.; Kuruvilla, T.; Damle, S.; Salganicoff, L.; Sheth, S.; Shah, N.; Marks, H.; Khurana, D.; Valencia, I.; Legido, A. Non-invasive evaluation of buccal respiratory chain enzyme dysfunction in mitochondrial disease: Comparison with studies in muscle biopsy. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2012, 105, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yorns, W.R., Jr.; Valencia, I.; Jayaraman, A.; Sheth, S.; Legido, A.; Goldenthal, M.J. Buccal swab analysis of mitochondrial enzyme deficiency and DNA defects in a child with suspected myoclonic epilepsy and ragged red fibers (MERRF). J. Child Neurol. 2012, 27, 398–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezugha, H.; Goldenthal, M.; Valencia, I.; Anderson, C.E.; Legido, A.; Marks, H. 5q14.3 deletion manifesting as mitochondrial disease and autism: Case report. J. Child Neurol. 2010, 25, 1232–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, D.M.; Thorburn, D.R.; Turnbull, D.M.; Taylor, R.W. Biochemical assays of respiratory chain complex activity. Methods Cell Biol. Mitochondria 2007, 80, 93–120. [Google Scholar]

- Werner, B.A.; McCarty, P.J.; Lane, A.L.; Singh, I.; Karim, M.A.; Rose, S.; Frye, R.E. Time dependent changes in the bioenergetics of peripheral blood mononuclear cells: Processing time, collection tubes and cryopreservation effects. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2022, 14, 1628–1639. [Google Scholar]

- Perez, J.; Hill, B.G.; Benavides, G.A.; Dranka, B.P.; Darley-Usmar, V.M. Role of cellular bioenergetics in smooth muscle cell proliferation induced by platelet-derived growth factor. Biochem. J. 2010, 428, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, B.G.; Higdon, A.N.; Dranka, B.P.; Darley-Usmar, V.M. Regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell bioenergetic function by protein glutathiolation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1797, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jyonouchi, H.; Geng, L.; Rose, S.; Bennuri, S.C.; Frye, R.E. Variations in Mitochondrial Respiration Differ in IL-1ss/IL-10 Ratio Based Subgroups in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breton, C.V.; Song, A.Y.; Xiao, J.; Kim, S.-J.; Mehta, H.H.; Wan, J.; Yen, K.; Sioutas, C.; Lurmann, F.; Xue, S.; et al. Effects of air pollution on mitochondrial function, mitochondrial DNA methylation, and mitochondrial peptide expression. Mitochondrion 2019, 46, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dranka, B.P.; Hill, B.G.; Darley-Usmar, V.M. Mitochondrial reserve capacity in endothelial cells: The impact of nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010, 48, 905–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detry, M.A.; Lewis, R.J. The intention-to-treat principle: How to assess the true effect of choosing a medical treatment. JAMA 2014, 312, 85–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagel, S.; Haussen, D.C.; Nogueira, R.G. Importance of the Intention-to-Treat Principle. JAMA Neurol. 2020, 77, 905–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, I.R.; Carpenter, J.; Horton, N.J. Including all individuals is not enough: Lessons for intention-to-treat analysis. Clin. Trials 2012, 9, 396–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matts, J.P.; Launer, C.A.; Nelson, E.T.; Miller, C.; Dain, B. A graphical assessment of the potential impact of losses to follow-up on the validity of study results. The Terry Beirn Community Programs for Clinical Research on AIDS. Stat. Med. 1997, 16, 1943–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laird, N.M.; Ware, J.H. Random-effects models for longitudinal data. Biometrics 1982, 38, 963–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.E.; Denys, D.A.J.P.; Mattila, T.K.; Storosum, B.W.C.; de Boer, A.; Zantvoord, J.B. Exploring the minimal important difference in the treatment of paediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder using selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. BMJ Ment. Health 2024, 27, e300999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurek, L.; Balthazar, M.; Gulati, S.; Novakovic, N.; Núñez, M.; Oakley, J.; O’hagan, A. Response (minimum clinically relevant change) in ASD symptoms after an intervention according to CARS-2: Consensus from an expert elicitation procedure. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2022, 31, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Behavioral Scale | F-Value± | p-Value | Cohen’s Effect Size (d) | MCID | Responders (%) | Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | Treatment | ||||||

| Parent Rated | |||||||

| VABS Adaptive Behavioral Composite | 10.95 | <0.01 | 1.21 | — | — | — | — |

| VABS Communication | 7.02 | =0.01 | 0.97 | 3.8 | 25 | 56.25 | n/s |

| VABS Daily Living Skills | 7.70 | <0.01 | 1.01 | 2.8 | 12.5 | 68.75 | 16.4 (2.3, 114.6) ** |

| VABS Socialization | 8.59 | <0.01 | 1.07 | 3.0 | 25 | 62.5 | 6.0 (1.1, 33.8) * |

| ABC Social Withdrawal | 6.31 | <0.05 | 0.92 | 1.0 | 37.5 | 93.75 | 41.1 (3.1, 551.5) ** |

| ABC Hyperactivity | 4.43 | <0.05 | 0.77 | 2.6 | 18.75 | 81.25 | 42.6 (3.8, 475.8) ** |

| ABC Inappropriate Speech | 4.54 | <0.05 | 0.78 | 0.7 | 50 | 62.5 | n/s |

| ABC Irritability | 0.01 | n/s | 0.04 | 1.8 | 37.5 | 43.75 | n/s |

| ABC Stereotypy | 0.04 | n/s | 0.07 | 0.7 | 56.25 | 68.75 | n/s |

| ABC Total | 2.35 | n/s | 0.56 | — | — | — | — |

| Caregiver Strain | 1.65 | n/s | 0.46 | — | — | — | — |

| PRASC Receptive Language | — | — | — | — | 17 | 10 | n/s |

| PRASC Expressive Language | — | — | — | — | 2 | 4 | n/s |

| PRASC Verbal Comm | — | — | — | — | 8 | 33 | 9.0 (0.78,104.16) ** |

| PRASC Nonverbal Comm | — | — | — | — | 19 | 17 | n/s |

| PRASC Stereotyped Behavior | — | — | — | — | 33 | 33 | n/s |

| PRASC Hyperactivity | — | — | — | — | 17 | 17 | n/s |

| PRASC Mood | — | — | — | — | 38 | 25 | n/s |

| PRASC Attention | — | — | — | — | 2 | 2 | n/s |

| PRASC Aggression | — | — | — | — | 13 | 8 | n/s |

| PRASC Fine Motor Skills | — | — | — | — | 4 | 4 | n/s |

| PRASC Gross Motor Skills | — | — | — | — | 0 | 0 | n/s |

| PRASC Seizures | — | — | — | — | 0 | 0 | n/s |

| Clinician Rated | |||||||

| CARS | 0.90 | n/s | 0.35 | 4.5 | 37.5 | 37.5 | n/s |

| CYBOCS-ASD | 0.04 | n/s | 0.07 | 5.1 | 6.25 | 0 | n/s |

| CGI-I | 0.89 | n/s | 0.35 | — | 44 | 44 | n/s |

| OACIS Social | 3.45 | n/s | 0.68 | — | 44 | 56 | n/s |

| OACIS Aberrant | 0.49 | n/s | 0.25 | — | 38 | 25 | n/s |

| OACIS Repetitive | 1.04 | n/s | 0.37 | — | 19 | 38 | n/s |

| OACIS Verbal | 0.00 | n/s | 0.00 | — | 38 | 38 | n/s |

| OACIS Non-Verbal | 1.27 | n/s | 0.41 | — | 25 | 13 | n/s |

| OACIS Hyperactivity | 0.75 | n/s | 0.32 | — | 0 | 13 | n/s |

| OACIS Anxiety | 4.57 | 0.04 | 0.78 | — | 13 | 19 | n/s |

| OACIS Sensory | 4.30 | 0.04 | 0.76 | — | 6 | 38 | n/s |

| OACIS Restricted | 2.04 | n/s | 0.52 | — | 19 | 31 | n/s |

| OACIS Autism | 0.62 | n/s | 0.29 | — | 25 | 50 | n/s |

| Psychometrician | |||||||

| DAS-GCA | 0.81 | n/s | 0.33 | — | — | — | — |

| Daily Serving Size | 6.6 g | 8.8 g | 11 g | 13.2 g | Tolerable Upper Limit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Body Weight | Units | 15–20 kg | 21–40 kg | 41–60 kg | 61–100 kg | Age 4–8 Years |

| SpectrumNeeds | ||||||

| Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) | mg | 450 | 600 | 750 | 900 | ND |

| Vitamin D (cholecalciferol) | mcg | 11.25 | 15 | 18.75 | 22.5 | 75 |

| Vitamin E (d-α-tocopheryl acetate and mixed tocopherols) | mg | 37.5 | 50 | 62.5 | 75 | 300 |

| Thiamin (thiamin HCl) | mg | 18.75 | 25 | 31.25 | 37.5 | ND |

| Riboflavin | mg | 18.75 | 25 | 31.25 | 37.5 | ND |

| Niacinamide | mg | 18.75 | 25 | 31.25 | 37.5 | 15 |

| Vitamin B6 (50% as pyridoxine HCl and 50% as pyridoxal-5-phosphate) | mg | 15 | 20 | 25 | 30 | 40 |

| (6S)-5-methyltetrahydrofolic acid | mcg | 1250 | 1667 | 2084 | 2500 | ND |

| Calcium folinate | mcg | 1250 | 1667 | 2084 | 2500 | 400 |

| Vitamin B12 (as methylcobalamin) | mcg | 375 | 500 | 625 | 750 | ND |

| Biotin | mcg | 750 | 1000 | 1250 | 1500 | ND |

| Pantothenic acid (D-Ca pantothenate) | mg | 225 | 300 | 375 | 450 | ND |

| Calcium | mg | 45 | 60 | 75 | 90 | 2500 |

| Iodine (as K iodide) | mcg | 75 | 100 | 125 | 150 | 300 |

| Magnesium (Mg citrate and Mg malate) | mg | 150 | 200 | 250 | 300 | 110 |

| Zinc (Zn gluconate) | mg | 9 | 12 | 15 | 18 | 12 |

| Selenium (as selenomethionine) | mcg | 37.5 | 50 | 62.5 | 75 | 150 |

| Manganese (as Mn amino acid chelate) | mg | 0.75 | 1 | 1.25 | 1.5 | 3 |

| Chromium (Cr picolinate) | mcg | 37.5 | 50 | 62.5 | 75 | ND |

| Molybdenum (Na molybdate) | mcg | 75 | 100 | 125 | 150 | 600 |

| Potassium (K citrate) | mg | 37.5 | 50 | 62.5 | 75 | |

| Creatine monohydrate | mg | 937.5 | 1250 | 1562.5 | 1875 | |

| L-arginine | mg | 750 | 1000 | 1250 | 1500 | |

| Carnitine blend (acetyl L-carnitine HCl and L-carnitine) | mg | 375 | 500 | 625 | 750 | |

| Alpha ketoglutaric acid | mg | 225 | 300 | 375 | 450 | |

| Ubiquinone | mg | 187.5 | 250 | 312.5 | 375 | |

| Choline (choline bitartrate) | mg | 112.5 | 150 | 187.5 | 225 | 1000 |

| Inositol | mg | 75 | 100 | 125 | 150 | |

| Alpha lipoic acid | mg | 75 | 100 | 125 | 150 | |

| D-beta, D-gamma, D-delta tocopherols | mg | 3.3 | 4.4 | 5.5 | 6.6 | 300 |

| QNeeds | ||||||

| Co-enzyme Q10 (Ubiquinol) | mg | 200 | 300 | 400 | 400 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hill, Z.; McCarty, P.J.; Boles, R.G.; Frye, R.E. A Mitochondrial Supplement Improves Function and Mitochondrial Activity in Autism: A Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Cross-Over Trial. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2479. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26062479

Hill Z, McCarty PJ, Boles RG, Frye RE. A Mitochondrial Supplement Improves Function and Mitochondrial Activity in Autism: A Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Cross-Over Trial. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(6):2479. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26062479

Chicago/Turabian StyleHill, Zoë, Patrick J. McCarty, Richard G. Boles, and Richard E. Frye. 2025. "A Mitochondrial Supplement Improves Function and Mitochondrial Activity in Autism: A Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Cross-Over Trial" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 6: 2479. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26062479

APA StyleHill, Z., McCarty, P. J., Boles, R. G., & Frye, R. E. (2025). A Mitochondrial Supplement Improves Function and Mitochondrial Activity in Autism: A Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Cross-Over Trial. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(6), 2479. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26062479