Asymmetric Dimethylaminohydrolase Gene Polymorphisms Associated with Preeclampsia Comorbid with HIV Infection in Pregnant Women of African Ancestry

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Clinical Characteristics

2.2. Genotype and Allele Frequencies of SNPs rs669173, rs7521189, rs805305, and rs3131383

2.3. rs669173

2.3.1. Normotensive HIV-Negative Pregnant Women vs. Preeclamptic HIV-Negative Pregnant Women

2.3.2. Normotensive HIV-Positive vs. Preeclamptic HIV-Positive Group

2.3.3. Normotensive Group vs. Preeclamptic Groups Regardless of HIV Status

2.3.4. Early Onset Preeclampsia vs. Late Onset Preeclampsia Groups Irrespective of HIV Status

2.3.5. Normotensive Group vs. Early Onset Preeclampsia Group Irrespective of HIV Status

2.3.6. Normotensive Group vs. Late Onset Preeclampsia Group Irrespective of HIV Status

2.3.7. HIV-Negative vs. HIV-Positive Women Regardless of Pregnancy Type

2.4. rs7521189

2.4.1. Normotensive vs. Preeclamptic HIV-Negative Group

2.4.2. Normotensive vs. Preeclamptic HIV-Positive Group

2.4.3. Normotensive Group vs. Preeclamptic Group Irrespective of HIV Status

2.4.4. Early Onset Preeclampsia vs. Late Onset Preeclampsia Groups Irrespective of HIV Status

2.4.5. Normotensive Group vs. Early Onset Preeclampsia Group Irrespective of HIV Status

2.4.6. Normotensive vs. Late Onset Preeclampsia Group Irrespective of HIV Status

2.4.7. HIV-Negative Group vs. HIV-Positive Group Regardless of Pregnancy Type

2.5. rs805305

2.5.1. Normotensive vs. Preeclamptic HIV-Negative Group

2.5.2. Normotensive vs. Preeclamptic HIV-Positive

2.5.3. Normotensive Group vs. Preeclamptic Group Regardless of HIV Status

2.5.4. Early vs. Late Onset Preeclampsia Groups Regardless of HIV Status

2.5.5. Normotensive Group vs. Early Onset Preeclampsia Group Regardless of HIV Status

2.5.6. Normotensive vs. Late Onset Preeclampsia Group Regardless of HIV Status

2.5.7. HIV-Negative Group vs. HIV-Positive Group Regardless of Pregnancy Type

2.6. rs3131383

2.6.1. Normotensive HIV-Negative vs. Preeclamptic HIV-Negative Groups

2.6.2. Normotensive HIV-Positive Group vs. Preeclamptic HIV-Positive Group

2.6.3. Normotensive vs. Preeclamptic Groups Irrespective of HIV Status

2.6.4. Early Onset Preeclampsia vs. Late Onset Preeclampsia Groups Regardless of HIV Status

2.6.5. Normotensive Group vs. Early Onset Preeclampsia Group Regardless of HIV Status

2.6.6. Normotensive Group vs. Late Onset Preeclampsia Group Regardless of HIV Status

2.6.7. HIV-Negative Groups vs. HIV-Positive Groups Regardless of Pregnancy Type

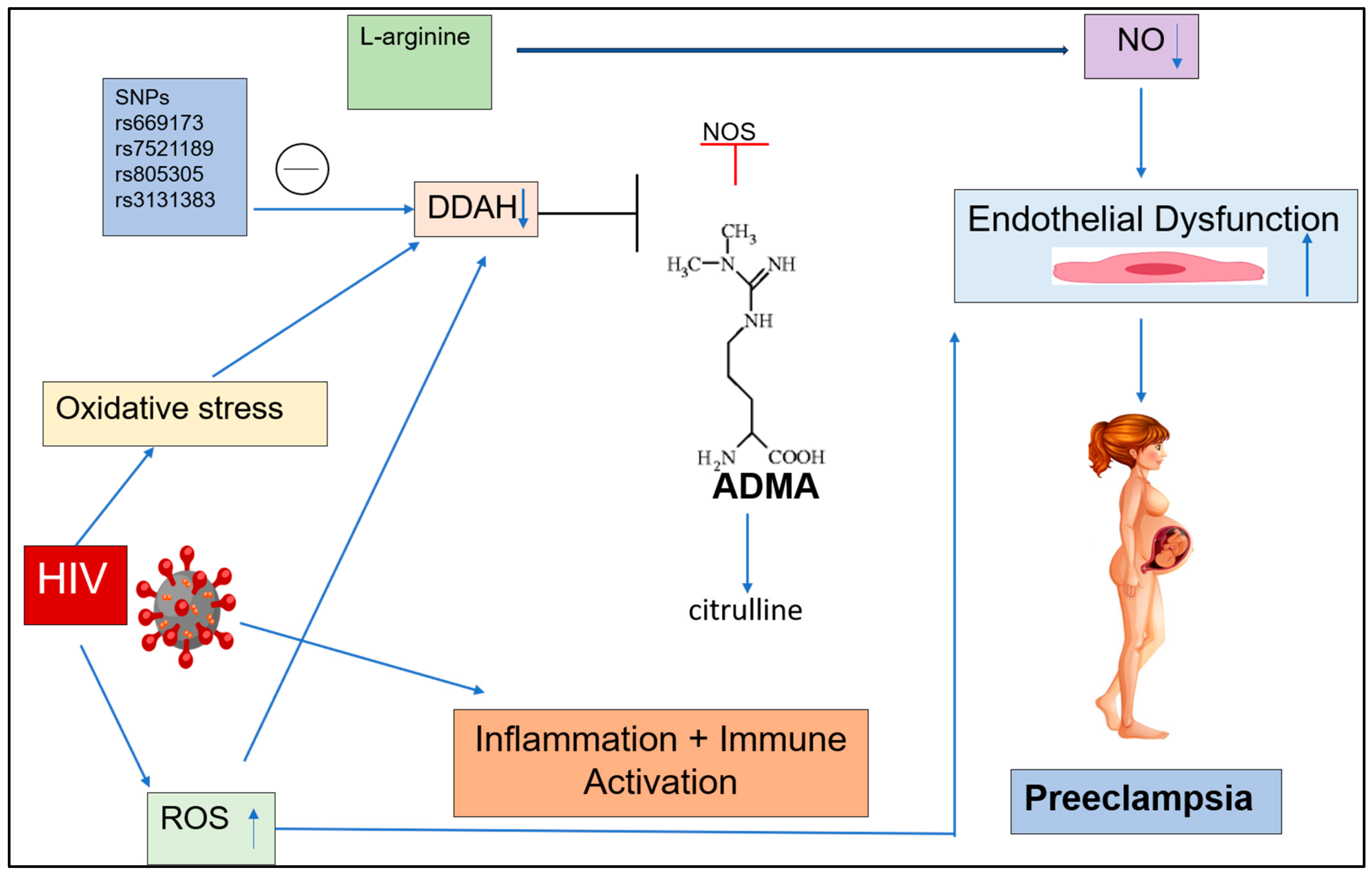

3. Discussion

3.1. DDAH 1

3.1.1. ADMA rs669173

3.1.2. ADMA rs7521189

3.2. DDAH 2

3.2.1. ADMA rs805305

3.2.2. ADMA rs3131383

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Population and Design

4.2. Sample Size

4.3. DNA Isolation

4.4. TaqMan Genotyping of ADMA Gene Polymorphisms

4.5. Genetic Modelling

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Magee, L.A.; Brown, M.A.; Hall, D.R.; Gupte, S.; Hennessy, A.; Karumanchi, S.A.; Kenny, L.C.; McCarthy, F.; Myers, J.; Poon, L.C. The 2021 International Society for the Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy classification, diagnosis & management recommendations for international practice. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2022, 27, 148–169. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Phipps, E.; Prasanna, D.; Brima, W.; Jim, B. Preeclampsia: Updates in pathogenesis, definitions, and guidelines. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016, 11, 1102–1113. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Garovic, V.D.; Dechend, R.; Easterling, T.; Karumanchi, S.A.; McMurtry Baird, S.; Magee, L.A.; Rana, S.; Vermunt, J.V.; August, P. Hypertension in pregnancy: Diagnosis, blood pressure goals, and pharmacotherapy: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension 2022, 79, e21–e41. [Google Scholar]

- Amaral, L.M.; Cunningham Jr, M.W.; Cornelius, D.C.; LaMarca, B. Preeclampsia: Long-term consequences for vascular health. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2015, 11, 403–415. [Google Scholar]

- Guerby, P.; Tasta, O.; Swiader, A.; Pont, F.; Bujold, E.; Parant, O.; Vayssiere, C.; Salvayre, R.; Negre-Salvayre, A. Role of oxidative stress in the dysfunction of the placental endothelial nitric oxide synthase in preeclampsia. Redox Biol. 2021, 40, 101861. [Google Scholar]

- Unicef. Trends in Maternal Mortality: 1990 to 2015: Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hounkpatin, O.I.; Amidou, S.A.; Houehanou, Y.C.; Lacroix, P.; Preux, P.M.; Houinato, D.S.; Bezanahary, H. Systematic review of observational studies of the impact of cardiovascular risk factors on preeclampsia in sub-saharan Africa. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilekis, J.V.; Reddy, U.M.; Roberts, J.M. Preeclampsia—A pressing problem: An executive summary of a National Institute of Child Health and Human Development workshop. Reprod. Sci. 2007, 14, 508–523. [Google Scholar]

- Jena, M.K.; Sharma, N.R.; Petitt, M.; Maulik, D.; Nayak, N.R. Pathogenesis of preeclampsia and therapeutic approaches targeting the placenta. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Bello, J.; Jiménez-Morales, M. Functional implications of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in protein-coding and non-coding RNA genes in multifactorial diseases. Gac. Med. Mex. 2017, 153, 238–250. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, I.; Siddiqui, H.I.; Qureshi, G.S.; Bernhardt, G.V. A review of literature on the pharmacogenomics of single-nucleotide polymorphisms. Biomed. Biotechnol. Res J. (BBRJ) 2022, 6, 14–20. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, J.M.; Gammill, H.S. Preeclampsia: Recent insights. Hypertension 2005, 46, 1243–1249. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gusella, A.; Martignoni, G.; Giacometti, C. Behind the Curtain of Abnormal Placentation in Pre-Eclampsia: From Molecular Mechanisms to Histological Hallmarks. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noris, M.; Perico, N.; Remuzzi, G. Mechanisms of disease: Pre-eclampsia. Nat. Clin. Pract. Nephrol. 2005, 1, 98–114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, J.S.; Ryan, M.J.; LaMarca, B.B.; Sedeek, M.; Murphy, S.R.; Granger, J.P. Pathophysiology of hypertension during preeclampsia: Linking placental ischemia with endothelial dysfunction. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2008, 294, H541–H550. [Google Scholar]

- Redman, C.W.; Sargent, I.L. Latest advances in understanding preeclampsia. Science 2005, 308, 1592–1594. [Google Scholar]

- Sankaralingam, S.; Arenas, I.A.; Lalu, M.M.; Davidge, S.T. Preeclampsia: Current understanding of the molecular basis of vascular dysfunction. Expert. Rev. Mol. Med. 2006, 8, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, S.J. Why is placentation abnormal in preeclampsia? Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 213, S115–S122. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, S.R.; LaMarca, B.B.D.; Parrish, M.; Cockrell, K.; Granger, J.P. Control of soluble fms-like tyrosine-1 (sFlt-1) production response to placental ischemia/hypoxia: Role of tumor necrosis factor-α. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2013, 304, R130–R135. [Google Scholar]

- Goulopoulou, S.; Davidge, S.T. Molecular mechanisms of maternal vascular dysfunction in preeclampsia. Trends Mol. Med. 2015, 21, 88–97. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Rana, S.; Karumanchi, S.A. Preeclampsia: The role of angiogenic factors in its pathogenesis. Physiology 2009, 24, 147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, L.J.; Morton, J.S.; Davidge, S.T. Vascular dysfunction in preeclampsia. Microcirculation 2014, 21, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karbach, S.; Wenzel, P.; Waisman, A.; Munzel, T.; Daiber, A. eNOS uncoupling in cardiovascular diseases-the role of oxidative stress and inflammation. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2014, 20, 3579–3594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leone, A.; Moncada, S.; Vallance, P.; Calver, A.; Collier, J. Accumulation of an endogenous inhibitor of nitric oxide synthesis in chronic renal failure. Lancet 1992, 339, 572–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibal, L.; Agarwal, S.C.; Home, P.D.; Boger, R.H. The role of asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) in endothelial dysfunction and cardiovascular disease. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2010, 6, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najbauer, J.; Johnson, B.A.; Young, A.L.; Aswad, D. Peptides with sequences similar to glycine, arginine-rich motifs in proteins interacting with RNA are efficiently recognized by methyltransferase (s) modifying arginine in numerous proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268, 10501–10509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiper, J.M.; Maria, J.S.; Chubb, A.; MacCallister, R.J.; Charles, I.G.; Whitley, G.S.J.; Vallance, P. Identification of two human dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolases with distinct tissue distributions and homology with microbial arginine deiminases. Biochem. J. 1999, 343, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achan, V.; Broadhead, M.; Malaki, M.; Whitley, G.; Leiper, J.; MacAllister, R.; Vallance, P. Asymmetric dimethylarginine causes hypertension and cardiac dysfunction in humans and is actively metabolized by dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2003, 23, 1455–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russwurm, M.; Koesling, D. Guanylyl cyclase: NO hits its target. Biochem. Soc. Symp. 2004, 71, 51–63. [Google Scholar]

- Hannemann, J.; Zummack, J.; Hillig, J.; Rendant-Gantzberg, L.; Böger, R. Association of variability in the DDAH1, DDAH2, AGXT2 and PRMT1 genes with circulating ADMA concentration in human whole blood. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palm, F.; Onozato, M.L.; Luo, Z.; Wilcox, C.S.J.A.J.o.P.-H.; Physiology, C. Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase (DDAH): Expression, regulation, and function in the cardiovascular and renal systems. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2007, 293, H3227–H3245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Gill, P.S.; Chabrashvili, T.; Onozato, M.L.; Raggio, J.; Mendonca, M.; Dennehy, K.; Li, M.; Modlinger, P.; Leiper, J.J.C.R. Isoform-specific regulation by NG, N G-dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase of rat serum asymmetric dimethylarginine and vascular endothelium-derived relaxing factor/NO. Circ. Res. 2007, 101, 627–635. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xuan, C.; Tian, Q.-W.; Li, H.; Zhang, B.-B.; He, G.-W.; Lun, L.-M. Levels of asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), an endogenous nitric oxide synthase inhibitor, and risk of coronary artery disease: A meta-analysis based on 4713 participants. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2016, 23, 502–510. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Akbar, F.; Heinonen, S.; Pirskanen, M.; Uimari, P.; Tuomainen, T.-P.; Salonen, J.T. Haplotypic association of DDAH1 with susceptibility to pre-eclampsia. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2005, 11, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wadham, C.; Mangoni, A.A. Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase regulation: A novel therapeutic target in cardiovascular disease. Expert. Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2009, 5, 303–319. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Yi, R.; Green, L.A.; Chelvanambi, S.; Seimetz, M.; Clauss, M. Increased cardiovascular disease risk in the HIV-positive population on ART: Potential role of HIV-Nef and Tat. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2015, 24, 279–282. [Google Scholar]

- Parikh, R.V.; Scherzer, R.; Grunfeld, C.; Nitta, E.M.; Leone, A.; Martin, J.N.; Deeks, S.G.; Ganz, P.; Hsue, P.Y. Elevated levels of asymmetric dimethylarginine are associated with lower CD4+ count and higher viral load in HIV-infected individuals. Atherosclerosis 2013, 229, 246–252. [Google Scholar]

- Song, L.; Ding, S.; Ge, Z.; Zhu, X.; Qiu, C.; Wang, Y.; Lai, E.; Yang, W.; Sun, Y.; Chow, S.A. Nucleoside/nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors attenuate angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis by impairing receptor tyrosine kinases signalling in endothelial cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 175, 1241–1259. [Google Scholar]

- Barillari, G. The anti-angiogenic effects of anti-human immunodeficiency virus drugs. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 806. [Google Scholar]

- Abhary, S.; Burdon, K.P.; Kuot, A.; Javadiyan, S.; Whiting, M.J.; Kasmeridis, N.; Petrovsky, N.; Craig, J.E. Sequence variation in DDAH1 and DDAH2 genes is strongly and additively associated with serum ADMA concentrations in individuals with type 2 diabetes. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9462. [Google Scholar]

- Savvidou, M.D.; Hingorani, A.D.; Tsikas, D.; Frölich, J.C.; Vallance, P.; Nicolaides, K.H. Endothelial dysfunction and raised plasma concentrations of asymmetric dimethylarginine in pregnant women who subsequently develop pre-eclampsia. Lancet 2003, 361, 1511–1517. [Google Scholar]

- Speer, P.D.; Powers, R.W.; Frank, M.P.; Harger, G.; Markovic, N.; Roberts, J.M. Elevated asymmetric dimethylarginine concentrations precede clinical preeclampsia, but not pregnancies with small-for-gestational-age infants. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2008, 198, 112.e111–112.e117. [Google Scholar]

- Braekke, K.; Ueland, P.M.; Harsem, N.K.; Staff, A.C. Asymmetric dimethylarginine in the maternal and fetal circulation in preeclampsia. Pediatr. Res. 2009, 66, 411–415. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Wu, S.; Xue, M.; Sandford, A.J.; Wu, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, G.; Tao, C.; Tang, Y.; Feng, Y. Heterozygote advantage of the rs3794624 polymorphism in CYBA for resistance to tuberculosis in two Chinese populations. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 38213. [Google Scholar]

- Valkonen, V.-P.; Tuomainen, T.-P.; Laaksonen, R. DDAH gene and cardiovascular risk. Vasc. Med. 2005, 10, S45–S48. [Google Scholar]

- Lind, L.; Ingelsson, E.; Kumar, J.; Syvänen, A.-C.; Axelsson, T.; Teerlink, T. Genetic variation in the dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase 1 gene (DDAH1) is related to asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) levels, but not to endothelium-dependent vasodilation. Vasc. Med. 2013, 18, 192–199. [Google Scholar]

- Fogarty, R.D.; Abhary, S.; Javadiyan, S.; Kasmeridis, N.; Petrovsky, N.; Whiting, M.J.; Craig, J.E.; Burdon, K.P. Relationship between DDAH gene variants and serum ADMA level in individuals with type 1 diabetes. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2012, 26, 195–198. [Google Scholar]

- Amir, M.; Hassanein, S.I.; Abdel Rahman, M.F.; Gad, M.Z. AGXT2 and DDAH-1 genetic variants are highly correlated with serum ADMA and SDMA levels and with incidence of coronary artery disease in Egyptians. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2018, 45, 2411–2419. [Google Scholar]

- Nasibullin, T.R.; Timasheva, Y.R.; Sadikova, R.I.; Tuktarova, I.A.; Erdman, V.V.; Nikolaeva, I.E.; Sabo, J.; Kruzliak, P.; Mustafina, O.E. Genotype/allelic combinations as potential predictors of myocardial infarction. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2016, 43, 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Böger, R.H. Association of asymmetric dimethylarginine and endothelial dysfunction. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2003, 41, 1467–1472. [Google Scholar]

- Vallance, P.; Leiper, J. Cardiovascular biology of the asymmetric dimethylarginine: Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase pathway. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2004, 24, 1023–1030. [Google Scholar]

- Predescu, D.; Predescu, S.; Shimizu, J.; Miyawaki-Shimizu, K.; Malik, A.B. Constitutive eNOS-derived nitric oxide is a determinant of endothelial junctional integrity. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2005, 289, L371–L381. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abbasi, F.; Asagmi, T.; Cooke, J.P.; Lamendola, C.; McLaughlin, T.; Reaven, G.M.; Stuehlinger, M.; Tsao, P.S. Plasma concentrations of asymmetric dimethylarginine are increased in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am. J. Cardiol. 2001, 88, 1201–1203. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sydow, K.; Mondon, C.E.; Schrader, J.; Konishi, H.; Cooke, J.P. Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase overexpression enhances insulin sensitivity. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2008, 28, 692–697. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hsu, C.-N.; Huang, L.-T.; Lau, Y.-T.; Lin, C.-Y.; Tain, Y.-L. The combined ratios of L-arginine and asymmetric and symmetric dimethylarginine as biomarkers in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Transl. Res. 2012, 159, 90–98. [Google Scholar]

- Dayoub, H.; Achan, V.; Adimoolam, S.; Jacobi, J.; Stuehlinger, M.C.; Wang, B.-y.; Tsao, P.S.; Kimoto, M.; Vallance, P.; Patterson, A.J. Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase regulates nitric oxide synthesis: Genetic and physiological evidence. Circulation 2003, 108, 3042–3047. [Google Scholar]

- Leiper, J.; Nandi, M.; Torondel, B.; Murray-Rust, J.; Malaki, M.; O’Hara, B.; Rossiter, S.; Anthony, S.; Madhani, M.; Selwood, D. Disruption of methylarginine metabolism impairs vascular homeostasis. Nat. Med. 2007, 13, 198–203. [Google Scholar]

- Wojciak-Stothard, B.; Torondel, B.; Zhao, L.; Renné, T.; Leiper, J.M. Modulation of Rac1 activity by ADMA/DDAH regulates pulmonary endothelial barrier function. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2009, 20, 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; He, B. Endothelial dysfunction: Molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. MedComm 2024, 5, e651. [Google Scholar]

- Abhary, S.; Kasmeridis, N.; Burdon, K.P.; Kuot, A.; Whiting, M.J.; Yew, W.P.; Petrovsky, N.; Craig, J.E. Diabetic retinopathy is associated with elevated serum asymmetric and symmetric dimethylarginines. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 2084–2086. [Google Scholar]

- Hanai, K.; Babazono, T.; Nyumura, I.; Toya, K.; Tanaka, N.; Tanaka, M.; Ishii, A.; Iwamoto, Y. Asymmetric dimethylarginine is closely associated with the development and progression of nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2009, 24, 1884–1888. [Google Scholar]

- Krzyzanowska, K.; Mittermayer, F.; Krugluger, W.; Schnack, C.; Hofer, M.; Wolzt, M.; Schernthaner, G. Asymmetric dimethylarginine is associated with macrovascular disease and total homocysteine in patients with type 2 diabetes. Atherosclerosis 2006, 189, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Malecki, M.T.; Undas, A.; Cyganek, K.; Mirkiewicz-Sieradzka, B.; Wolkow, P.; Osmenda, G.; Walus-Miarka, M.; Guzik, T.J.; Sieradzki, J. Plasma asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) is associated with retinopathy in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2007, 30, 2899–2901. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hannemann, J.; Glatzel, A.; Hillig, J.; Zummack, J.; Schumacher, U.; Lüneburg, N.; Harbaum, L.; Böger, R. Upregulation of DDAH2 limits pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular hypertrophy during chronic hypoxia in Ddah1 knockout mice. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 597559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorlova, O.Y.; Ying, J.; Amos, C.I.; Spitz, M.R.; Peng, B.; Gorlov, I.P. Derived SNP alleles are used more frequently than ancestral alleles as risk-associated variants in common human diseases. J. Bioinform. Comput. Biol. 2012, 10, 1241008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, R.; Erdmann, J.; Lüneburg, N.; Stritzke, J.; Schwedhelm, E.; Meisinger, C.; Peters, A.; Weil, J.; Schunkert, H.; Böger, R.H. Polymorphisms in the promoter region of the dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase 2 gene are associated with prevalence of hypertension. Pharm. Res. 2009, 60, 488–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaliq, O.P.; Konoshita, T.; Moodely, J.; Ramsuran, V.; Naicker, T. Gene polymorphisms of uric acid are associated with pre-eclampsia in South Africans of African ancestry. Hypertens. Pregnancy 2020, 39, 103–116. [Google Scholar]

- Mlambo, Z.P.; Sebitloane, M.; Naicker, T. Association of angiogenic factors (placental growth factor and soluble FMS-like tyrosine kinase-1) in preeclamptic women of African ancestry comorbid with HIV infection. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2024, 311, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf, M.; Thaha, M.; Yogiarto, R.M.; Aminuddin, M.; Yogiantoro, R.M.; Handajani, R.; Tomino, Y. Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase 2 gene polymorphism and its association with asymmetrical dimethyl arginine in hemodialyzed patients. J. Nephrol. 2013, 3, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, F.S.; Luizon, M.R.; Lopes, A.C.d.S.; Pereira, D.A.; Evangelista, F.C.G.; Godoi, L.C.; Dusse, L.M.; Alpoim, P.N. Early and late-onset preeclampsia: Effects of DDAH2 polymorphisms on ADMA levels and association with DDAH2 haplotypes. Rev. Bras. Ginecol. Obs. 2024, 46, e-rbgo19. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, L.; Tran, C.; Leiper, J.; Hingorani, A.; Vallance, P. Common genetic variation in a basal promoter element alters DDAH2 expression in endothelial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003, 310, 836–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dwyer, M.J.; Dempsey, F.; Crowley, V.; Kelleher, D.P.; McManus, R.; Ryan, T. Septic shock is correlated with asymmetrical dimethyl arginine levels, which may be influenced by a polymorphism in the dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase II gene: A prospective observational study. Crit. Care 2006, 10, R139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambden, S.; Tomlinson, J.; Piper, S.; Gordon, A.C.; Leiper, J. Evidence for a protective role for the rs805305 single nucleotide polymorphism of dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase 2 (DDAH2) in septic shock through the regulation of DDAH activity. Crit. Care 2018, 22, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray-Rust, J.; Leiper, J.; McAlister, M.; Phelan, J.; Tilley, S.; Maria, J.S.; Vallance, P.; McDonald, N. Structural insights into the hydrolysis of cellular nitric oxide synthase inhibitors by dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2001, 8, 679–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodžić, J.; Izetbegović, S.; Muračević, B.; Iriškić, R.; Jović, H.Š. Nitric oxide biosynthesis during normal pregnancy and pregnancy complicated by preeclampsia. Med. Glas. 2017, 14, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiessl, B.; Strasburger, C.; Bidlingmaier, M.; Mylonas, I.; Jeschke, U.; Kainer, F.; Friese, K. Plasma-and urine concentrations of nitrite/nitrate and cyclic Guanosinemonophosphate in intrauterine growth restricted and preeclamptic pregnancies. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2006, 274, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, E.F.; Gemmel, M.; Powers, R.W. Nitric oxide signaling in pregnancy and preeclampsia. Nitric Oxide 2020, 95, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Chen, J.; Sun, K.; Xin, Y.; Liu, J.; Hui, R. Common genetic variation in DDAH2 is associated with intracerebral haemorrhage in a Chinese population: A multi-centre case-control study in China. Clin. Sci. 2009, 117, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, S.L.; Yu, M.; Jennings, L.; Haymond, S.; Zhang, G.; Wainwright, M.S. Pilot study of the association of the DDAH2− 449G polymorphism with asymmetric dimethylarginine and hemodynamic shock in pediatric sepsis. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e33355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, A.M.M.; Brites-Anselmi, G.; Pinheiro, L.C.; de Almeida Belo, V.; Coeli-Lacchini, F.B.; Molina, C.A.F.; de Andrade, M.F.; Tucci, S., Jr.; Hirsch, E.; Tanus-Santos, J.E. Relationship between asymmetric dimethylarginine, nitrite and genetic polymorphisms: Impact on erectile dysfunction therapy. Nitric Oxide 2017, 71, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trimèche-Othmani, T.; Kammoun, M.; Callebert, J.; Abid, K.; Maatouk, F.; Mebazaa, A.; Launay, J.-M.; Vodovar, N.; Kenani, A. Association between genetic polymorphisms of ACE, eNOS, DDAH-2 and ADMA, SDMA and NOx with coronary artery disease in Tunisian population. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2016, 9, 4119–4124. [Google Scholar]

- Pintye, D.; Sziva, R.E.; Biwer, L.A.; Karreci, E.S.; Jacas, S.; Mastyugin, M.; Török, M.; Young, B.C.; Jagtap, P.; Southan, G.J.; et al. A Novel Dual-Function Nitric Oxide Donor Therapy for Preeclampsia—A Proof-of-Principle Study in a Murine Model. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tashie, W.; Fondjo, L.A.; Owiredu, W.K.; Ephraim, R.K.; Asare, L.; Adu-Gyamfi, E.A.; Seidu, L. Altered bioavailability of nitric oxide and L-arginine is a key determinant of endothelial dysfunction in preeclampsia. BioMed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 3251956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fondjo, L.A.; Awuah, E.O.; Sakyi, S.A.; Senu, E.; Detoh, E. Association between endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) gene variants and nitric oxide production in preeclampsia: A case–control study in Ghana. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 14740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellul, J.; Markoula, S.; Marousi, S.; Galidi, A.; Kyritsis, A.P.; Papathanasopoulos, P.; Georgiou, I. Association of endothelial nitric oxide synthase polymorphism G894T with functional outcome in acute stroke patients. Neurol. Res. 2011, 33, 835–840. [Google Scholar]

- Demir, B.; Demir, S.; Pasa, S.; Guven, S.; Atamer, Y.; Atamer, A.; Kocyigit, Y. The role of homocysteine, asymmetric dimethylarginine and nitric oxide in pre-eclampsia. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2012, 32, 525–528. [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa, K.; Wakino, S.; Tanaka, T.; Kimoto, M.; Tatematsu, S.; Kanda, T.; Yoshioka, K.; Homma, K.; Sugano, N.; Kurabayashi, M. Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase 2 increases vascular endothelial growth factor expression through Sp1 transcription factor in endothelial cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2006, 26, 1488–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupferminc, M.J.; Daniel, Y.; Englender, T.; Baram, A.; Many, A.; Jaffa, A.J.; Gull, I.; Lessing, J.B. Vascular endothelial growth factor is increased in patients with preeclampsia. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 1997, 38, 302–306. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.S.; Oh, M.-J.; Jung, J.W.; Lim, J.-E.; Seol, H.-J.; Lee, K.-J.; Kim, H.-J. The levels of circulating vascular endothelial growth factor and soluble Flt-1 in pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2007, 22, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, D. Genetic Variants Associated with Hypertension Risk: Progress and Implications. Pulse 2024, 12, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Yako, Y.Y.; Balti, E.V.; Matsha, T.E.; Dzudie, A.; Kruger, D.; Sobngwi, E.; Agyemang, C.; Kengne, A.P. Genetic factors contributing to hypertension in African-based populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2018, 20, 485–495. [Google Scholar]

- Kalideen, K.; Rayner, B.; Ramesar, R. Genetic Factors Contributing to the Pathogenesis of Essential Hypertension in Two African Populations. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trittmann, J.K.; Gastier-Foster, J.M.; Zmuda, E.J.; Frick, J.; Rogers, L.K.; Vieland, V.J.; Chicoine, L.G.; Nelin, L.D. A single nucleotide polymorphism in the dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase gene is associated with lower risk of pulmonary hypertension in bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Acta Paediatr. 2016, 105, e170–e175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casas, J.P.; Bautista, L.E.; Humphries, S.E.; Hingorani, A.D. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase genotype and ischemic heart disease: Meta-analysis of 26 studies involving 23028 subjects. Circulation 2004, 109, 1359–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catarino, C.; Santos-Silva, A.; Belo, L.; Rocha-Pereira, P.; Rocha, S.; Patrício, B.; Quintanilha, A.; Rebelo, I. Inflammatory disturbances in preeclampsia: Relationship between maternal and umbilical cord blood. J. Pregnancy 2012, 2012, 684384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeks, S.G. HIV infection, inflammation, immunosenescence, and aging. Annu. Rev. Med. 2011, 62, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, E.R.; Sutliff, R.L. The roles of HIV-1 proteins and antiretroviral drug therapy in HIV-1-associated endothelial dysfunction. J. Investig. Med. 2008, 56, 752–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, P.J.; Carrington, M. The impact of host genetic variation on infection with HIV-1. Nat. Immunol. 2015, 16, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvornyk, V.; Long, J.-R.; Xiong, D.-H.; Liu, P.-Y.; Zhao, L.-J.; Shen, H.; Zhang, Y.-Y.; Liu, Y.-J.; Rocha-Sanchez, S.; Xiao, P. Current limitations of SNP data from the public domain for studies of complex disorders: A test for ten candidate genes for obesity and osteoporosis. BMC Genet. 2004, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical power analysis. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 1992, 1, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manna, F.; Martin, G.; Lenormand, T. Fitness landscapes: An alternative theory for the dominance of mutation. Genetics 2011, 189, 923–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Patient Data | p Value | N− (n = 102) | N+ (n = 99) | EOPE− (n = 50) | EOPE+ (n = 52) | LOPE− (n = 51) | LOPE+ (n = 51) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systolic BP (mmHg) N vs. EOPE N vs. LOPE EOPE vs. LOPE | <0.0001 **** <0.0001 **** 0.9162 | 119.0 (111.0–124.0) | 114.0 (109.0–120.0) | 161.0 (155.0–168.0) | 161.0 (154.0–165.0) | 159.0 (155.0–168.8) | 155.0 (148.0–164.0) |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) N vs. EOPE N vs. LOPE EOPE vs. LOPE | <0.0001 **** <0.0001 **** 0.9543 | 71.00 (66.00–78.00) | 71.00 (65.00–75.00) | 104.0 (96.75–107.0) | 104.0 (94.00–111.0) | 101.5 (94.00–107.0) | 99.00 (96.00–105.0) |

| Gestational Age (weeks) N vs. EOPE N vs. LOPE EOPE vs. LOPE | <0.0001 **** <0.0001 **** <0.0001 **** | 39.00 (38.00–40.00) | 38.00 (37.00–39.00) | 30.00 (27.00–32.00) | 29.00 (25.00–32.00) | 38.00 (36.00–39.00) | 37.00 (35.00–38.00) |

| Maternal Age (years) N vs. EOPE N vs. LOPE EOPE vs. LOPE | <0.0001 **** 0.9639 0.0068 ** | 23.00 (20.00–28.00) | 27.00 (23.00–32.00) | 30.00 (23.25–35.00) | 30.00 (27.00–33.00) | 24.00 (20.75–30.00) | 29.00 (24.00–32.00) |

| Maternal Weight (Kg) N vs. EOPE N vs. LOPE EOPE vs. LOPE | 0.1317 0.0012 ** 0.5743 | 71.50 (60.15–83.63) | 70.00 (62.80–80.00) | 73.00 (63.93–90.00) | 73.10 (65.00–89.70) | 73.00 (63.50–89.40) | 77.00 (68.00–101.0) |

| SNP | N− vs. PE− OR (95% CI), p Value | N+ vs. PE+ OR (95% CI), p Value | EOPE− vs. EOPE+ OR (95% CI), p Value | LOPE− vs. LOPE+ OR (95% CI), p Value | N vs. PE OR (95% CI), p Value | HIV− vs. HIV+ OR (95% CI), p Value | N vs. EOPE OR (95% CI), p Value | N vs. LOPE OR (95% CI), p Value | EOPE vs. LOPE OR (95% CI), p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs669173 T>C Genotype | TT vs. CC (Co-dominant) | 0.4250 (0.1963–0.9202) p = 0.0352 * | 0.7792 (0.3732–1.627) p = 0.5756 | 2.000 (0.7026–5.693) p = 0.2930 | 0.5625 (0.1951–1.622) p = 0.4230 | 0.5817 (0.3423–0.9886) p = 0.0605 | 1.247 (0.7370–2.111) p = 0.4246 | 0.6018 (0.3168–1.143) p = 0.1397 | 0.5616 (0.2936–1.075) p = 0.0971 | 0.9333 (0.4476–1.946) p ≥ 0.9999 |

| TT vs. TC (Co-dominant) | 1.429 (0.7565–2.698) p = 0.3338 | 1.179 (0.6157–2.256) p = 0.7409 | 0.6667 (0.2605–1.706) p = 0.4788 | 1.333 (0.5178–3.433) p = 0.6343 | 1.302 (0.8272–2.049) p = 0.2993 | 0.9584 (0.6098–1.506) p = 0.9083 | 1.231 (0.7038–2.152) p = 0.4826 | 1.378 (0.7846–2.422) p = 0.3206 | 1.120 (0.5786–2.168) p = 0.8664 | |

| TC vs. CC (Co-dominant) | 0.6071 (0.2923 –1.261) p = 0.2030 | 0.9184 (0.4612–1.829) p = 0.8616 | 1.333 (0.5137–3.461) p = 0.6318 | 0.7500 (0.2913–1.931) p = 0.6343 | 0.7574 (0.4597–1.248) p = 0.3117 | 1.195 (0.7278–1.963) p = 0.5283 | 0.7406 (0.4056–1.352) p = 0.3548 | 0.7742 (0.4254–1.409) p = 0.4428 | 1.045 (0.5364–2.034) p ≥ 0.9999 | |

| TT vs. TC+CC (Dominant) | 1.682 (0.9325–3.034) p = 0.1020 | 1.217 (0.6703–2.209) p = 0.5462 | 0.5965 (0.2512–1.416) p = 0.2811 | 1.486 (0.6182–3.571) p = 0.5061 | 1.436 (0.9445–2.182) p = 0.1109 | 0.8998 (0.5932–1.365) p = 0.6712 | 1.369 (0.8187–2.288) p = 0.2500 | 1.507 (0.8948–2.539) p = 0.1558 | 1.101 (0.5990–2.024) p = 0.8768 | |

| TT+TC vs. CC (Recessive) | 1.918 (0.9724–3.782) p = 0.0646 | 1.167 (0.6199–2.196) p = 0.7477 | 0.6375 (0.2651–1.533) p = 0.3773 | 1.486 (0.6182–3.571) p = 0.5061 | 1.477 (0.9314–2.341) p = 0.1040 | 0.8216 (0.5200–1.298) p = 0.4170 | 1.477 (0.8485–2.570) p = 0.1923 | 1.477 (0.8485–2.570) p = 0.1923 | 1.000 (0.5406–1.850) p ≥ 0.9999 | |

| TT+CC vs. TC (Over-dominant) | 1.018 (0.5849–1.771) p ≥ 0.9999 | 1.053 (0.6031–1.838) p = 0.8876 | 0.9333 (0.4261–2.044) p ≥ 0.9999 | 1.000 (0.4583–2.182) p ≥ 0.9999 | 1.034 (0.6984–1.532) p = 0.9203 | 1.053 (0.7108–1.559) p = 0.8414 | 0.9941 (0.6144–1.608) p ≥ 0.9999 | 1.076 (0.6663–1.739) p = 0.8069 | 1.083 (0.6229–1.882) p = 0.8879 | |

| Allele | T vs. C (Major vs. minor) | 0.6320 (0.4260–0.9375 p = 0.0278 * | 0.8663 (0.5859–1.281) p = 0.4867 | 1.480 (0.8524–2.570) p = 0.2073 | 0.7302 (0.4210–1.267) p = 0.3270 | 0.7397 (0.5605–0.9761) p = 0.0346 * | 1.126 (0.8538–1.485) p = 0.4379 | 0.7543 (0.5377–1.058) p = 0.1193 | 0.7253 (0.5170–1.018) p = 0.0696 | 0.9615 (0.6521–1.418) p = 0.9211 |

| SNP | N− vs. PE− OR (95% CI), p Value | N+ vs. PE+ OR (95% CI), p Value | EOPE− vs. EOPE+ OR (95% CI), p Value | LOPE− vs. LOPE+ OR (95% CI), p Value | N vs. PE OR (95% CI), p Value | HIV− vs. HIV+ OR (95% CI), p Value | N vs. EOPE OR (95% CI), p Value | N vs. LOPE OR (95% CI), p Value | EOPE vs. LOPE OR (95% CI), p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs7521189 G>A Genotype | GG vs. AA (Co-dominant) | 1.714 (0.8017–3.666) p = 0.1835 | 1.903 (0.8697–4.165) p = 0.1185 | 0.8750 (0.2818–2.717) p ≥ 0.9999 | 2.054 (0.6548–6.440) p = 0.2554 | 1.827 (1.061–3.148) p = 0.0398 * | 1.334 (0.7791–2.286) p = 0.3386 | 1.555 (0.7904–3.058) p = 0.2346 | 2.130 (1.085–4.181) p = 0.0317 * | 1.370 (0.6166–3.045) p = 0.5425 |

| GG vs. GA (Co-dominant) | 1.943 (0.9723–3.882) p = 0.0828 | 1.418 (0.6853–2.936) p = 0.3640 | 1.167 (0.4155–3.276) p = 0.7977 | 0.9259 (0.3097–2.768) p ≥ 0.9999 | 1.669 (1.011–2.753) p = 0.0586 | 1.235 (0.7530–2.027) p = 0.4505 | 1.665 (0.9014–3.076) p = 0.1317 | 1.672 (0.8843–3.162) p = 0.1218 | 1.004 (0.4747–2.124) p ≥ 0.9999 | |

| GA vs. AA (Co-dominant) | 0.8824 (0.4572–1.703) p = 0.7394 | 1.342 (0.7084–2.542) p = 0.4189 | 0.7500 (0.3046–1.847) p = 0.6474 | 2.218 (0.9190–5.352) p = 0.0836 | 1.095 (0.6931–1.730) p = 0.7275 | 1.517 (0.6968–3.281) p = 0.3016 | 0.9336 (0.5326–1.637) p = 0.8867 | 1.274 (0.7375–2.200) p = 0.4038 | 1.365 (0.7321–2.543) p = 0.3465 | |

| GG vs. GA+AA (Dominant) | 1.851 (0.9724–3.525) p = 0.0766 | 1.595 (0.8070–3.154) p = 0.2287 | 1.050 (0.3949–2.792) p ≥ 0.9999 | 1.311 (0.4710–3.649) p = 0.7957 | 1.729 (1.084–2.759) p = 0.0256 * | 1.273 (0.8027–2.020) p = 0.3484 | 1.623 (0.9112–2.890) p = 0.1243 | 1.847 (1.019–3.347) p = 0.0485 * | 1.138 (0.5619–2.306) p = 0.8575 | |

| GG+GA vs. AA (Recessive) | 1.117 (0.6071–2.054) p = 0.7576 | 1.495 (0.8219–2.719) p = 0.2265 | 0.7829 (0.3334–1.839) p = 0.6654 | 2.171 (0.9501–4.960) p = 0.0988 | 1.298 (0.8477–1.988) p = 0.2357 | 1.159 (0.7580–1.774) p = 0.5171 | 1.106 (0.6530–1.873) p = 0.7868 | 1.511 (0.9082–2.514) p = 0.1150 | 1.366 (0.7596–2.457) p = 0.3711 | |

| GG+AA vs. GA (Over-dominant) | 1.457 (0.8367–2.538) p = 0.2061 | 0.9656 (0.5555–1.678) p ≥ 0.9999 | 1.264 (0.5805–2.752) p = 0.6922 | 0.5735 (0.2612–1.259) p = 0.2332 | 1.187 (0.8025–1.754) p = 0.4258 | 1.050 (0.7105–1.552) p = 0.8423 | 1.309 (0.8116–2.110) p = 0.2757) | 1.075 (0.6663–1.736) p = 0.8074 | 0.8217 (0.4741–1.424) p = 0.5754 | |

| Allele | G vs. A (Major vs. minor) | 1.319 (0.8930–1.949) p = 0.1663 | 1.395 (0.9410–2.068) p = 0.1096 | 0.9167 (0.5278–1.592) p = 0.7798 | 1.567 (0.8925–2.750) p = 0.1539 | 1.358 (1.030–1.792) p = 0.0346 * | 1.161 (0.8809–1.531) p = 0.2918 | 1.242 (0.8856–1.742) p = 0.2289 | 1.487 (1.057–2.092) p = 0.0252 * | 1.198 (0.8086–1.773) p = 0.4236 |

| SNP | N− vs. PE− OR (95% CI), p Value | N+ vs. PE+ OR (95% CI), p Value | EOPE− vs. EOPE+ OR (95% CI), p Value | LOPE− vs. LOPE+ OR (95% CI), p Value | N vs. PE OR (95% CI), p Value | HIV− vs. HIV+ OR (95% CI), p Value | N vs. EOPE OR (95% CI), p Value | N vs. LOPE OR (95% CI), p Value | EOPE vs. LOPE OR (95% CI), p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs805305 C>G Genotype | CC vs. GG (Co-dominant) | 2.396 (0.8613–6.668) p = 0.1407 | 0.9744 (0.3699–2.566) p ≥ 0.9999 | 0.5079 (0.1539–1.676) p = 0.3793 | 1.417 (0.3480–5.767) p = 0.7293 | 1.522 (0.7598–3.047) p = 0.2974 | 1.139 (0.5767–2.251) p = 0.7308 | 1.811 (0.8252–3.974) p = 0.1498 | 1.219 (0.5060–2.936) p = 0.6528 | 0.6730 (0.2723–1.664) p = 0.4983 |

| CC vs. CG (Co-dominant) | 1.058 (0.5399–2.073) p ≥ 0.9999 | 0.7441 (0.4016–1.379) p = 0.3526 | 1.219 (0.4536–3.276) p = 0.8038 | 1.395 (0.5777–3.368) p = 0.5072 | 0.8860 (0.5638–1.393) p = 0.6455 | 1.544 (0.9793–2.436) p = 0.0660 | 0.7276 (0.4066–1.302) p = 0.3157 | 1.052 (0.6135–1.804) p = 0.8906 | 1.446 (0.7487–2.792) p = 0.3194 | |

| CG vs. GG (Co-dominant) | 2.265 (0.7314–7.016) p = 0.1789 | 1.310 (0.4666–3.676) p = 0.7931 | 0.4167 (0.1034–1.679) p = 0.3053 | 1.016 (0.2255–4.575) p ≥ 0.9999 | 1.717 (0.8078–3.651) p = 0.1874 | 0.7377 (0.3507–1.552) p = 0.4513 | 1. (0.2418–2.609) p = 0.0626 | 1.159 (0.4524–2.967) p = 0.8105 | 0.4655 (0.1698–1.276) p = 0.2070 | |

| CC vs. CG+GG (Dominant) | 1.335 (0.7368–2.419) p = 0.3674 | 0.7934 (0.4509–1.396) p = 0.4727 | 0.8635 (0.3810–1.957) p = 0.8353 | 1.400 (0.6251–3.136) p = 0.5393 | 1.020 (0.6791–1.533) p ≥ 0.9999 | 1.424 (0.9461–2.144) p = 0.0973 | 0.9565 (0.5796–1.578) p = 0.8991 | 1.087 (0.6628–1.783) p = 0.8003 | 1.137 (0.6408–2.016) p = 0.7703 | |

| CC+CG vs. GG (Recessive) | 2.364 (0.8610–6.489) p = 0.0974 | 1.075 (0.4174–2.770) p ≥ 0.9999 | 0.4846 (0.1503–1.563) p = 0.2592 | 1.277 (0.3224–5.059) p ≥ 0.9999 | 1.576 (0.7966–3.117) p = 0.2331 | 1.005 (0.5154–1.961) p ≥ 0.9999 | 1.973 (0.9121–4.267) p = 0.0982 | 1.200 (0.5061–2.845) p = 0.6595 | 0.6083 (0.2506–1.477) p = 0.3763 | |

| CC+GG vs. CG (Over-dominant) | 0.9565 (0.4931–1.856) p ≥ 0.9999 | 0.7467 (0.4087–1.364) p = 0.3613 | 1.367 (0.5191–3.598) p = 0.6268 | 1.336 (0.5631–3.171) p = 0.6611 | 0.8407 (0.5394–1.310) p = 0.4978 | 1.519 (0.9713–2.376) p = 0.0712 | 0.6713 (0.3794–1.188) p = 0.2089 | 1.029 (0.6058–1.747) p ≥ 0.9999 | 1.532 (0.8042–2.920) p = 0.2544 | |

| Allele | C vs. G (Major vs. minor) | 1.505 (0.9244–2.450) p = 0.1102 | 0.8757 (0.5562–1.378) p = 0.6437 | 0.3804 (0.3804–1.383) p = 0.4126 | 1.320 (0.6855–2.540) p = 0.5063 | 1.131 (0.8124–1.573) p = 0.5009 | 1.263 (0.9071–1.759) p = 0.1784 | 1.162 (0.7786–1.733) p = 0.4710 | 1.100 (0.7345–1.647) p = 0.6782 | 0.9470 (0.5992–1.497) p = 0.9071 |

| SNP | N− vs. PE− OR (95% CI), p Value | N+ vs. PE+ OR (95% CI), p Value | EOPE− vs. EOPE+ OR (95% CI), p Value | LOPE− vs. LOPE+ OR (95% CI), p Value | N vs. PE OR (95% CI), p Value | HIV− vs. HIV+ OR (95% CI), p Value | N vs. EOPE OR (95% CI), p Value | N vs. LOPE OR (95% CI), p Value | EOPE vs. LOPE OR (95% CI), p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs3131383 G>T Genotype | GG vs. TT (Co-dominant) | 1.841 (0.8683–3.902) p = 0.1306 | 1.250 (0.5569–2.804) p = 0.6828 | 0.4934 (0.1463–1.664) p = 0.3642 | 0.7521 (0.2842–1.991) p = 0.6258 | 1.521 (0.8785–2.634) p = 0.1645 | 0.7687 (0.4447–1.328) p = 0.4050 | 0.9354 (0.4556–1.920) p ≥ 0.9999 | 2.303 (1.223–4.337) p = 0.0113 * | 2.462 (1.144–5.298) p = 0.0239 * |

| GG vs. GT (Co-dominant) | 2.137 (1.044–4.374) p = 0.0490 * | 1.117 (0.5569–2.240) p = 0.8596 | 0.5921 (0.2204–1.591) p = 0.3269 | 0.8254 (0.3243–2.101) p = 0.8126 | 1.535 (0.9337–2.524) p = 0.1025 | 0.9542 (0.5828–1.562) p = 0.9002 | 1.175 (0.6374–2.167) p = 0.6368 | 2.015 (1.113–3.648) p = 0.0271 * | 1.714 (0.8718–3.371) p = 0.1264 | |

| GT vs. TT (Co-dominant) | 0.8615 (0.3469–2.139) p = 0.8184 | 1.119 (0.4327–2.893) p ≥ 0.9999 | 0.8333 (0.2029–3.423) p ≥ 0.9999 | 0.9112 (0.3026–2.744) p ≥ 0.9999 | 0.9911 (0.5152–1.906) p ≥ 0.9999 | 0.8056 (0.4206–1.543) p = 0.6200 | 0.7959 (0.3402–1.862) p = 0.6699 | 1.143 (0.5457–2.394) p = 0.8506 | 1.436 (0.5933–3.475) p = 0.5052 | |

| GG vs. GT+TT (Dominant) | 1.993 (1.121–3.544) p = 0.0212 * | 1.169 (0.6555–2.086) p = 0.6591 | 0.5526 (0.2400–1.273) p = 0.2083 | 0.7901 (0.3630–1.720) p = 0.6923 | 1.529 (1.018–2.297) p = 0.0501 | 0.8686 (0.5797–1.301) p = 0.5368 | 1.070 (0.6443–1.778) p = 0.7963 | 2.141 (1.313–3.490) p = 0.0026 ** | 2.000 (1.136–3.522) p = 0.0228 * | |

| GG+GT vs. TT (Recessive) | 1.523 (0.7344–3.156) p = 0.2755 | 1.217 (0.5519–2.682) p = 0.6907 | 0.5585 (0.1695–1.841) p = 0.3848 | 0.8038 (0.3211–2.013) p = 0.8158 | 1.369 (0.8016–2.338) p = 0.2798 | 0.7776 (0.4562–1.326) p = 0.4169 | 0.9025 (0.4455–1.828) p = 0.8600 | 1.901 (1.036–3.490) p = 0.0521 | 2.107 (1.005–4.417) p = 0.0682 | |

| GG+TT vs. GT (Over-dominant) | 1.863 (0.9293–3.736) p = 0.0853 | 1.073 (0.5433–2.119) p = 0.8639 | 0.6628 (0.2516–1.746) p = 0.4675 | 0.9041 (0.3749–2.181) p ≥ 0.9999 | 1.410 (0.8687–2.289) p = 0.1787 | 1.006 (0.6223–1.627) p ≥ 0.9999 | 1.188 (0.6519–2.166) p = 0.6411 | 1.650 (0.9341–2.914) p = 0.0993 | 1.389 (0.7240–2.663) p = 0.4094 | |

| Allele | G vs. T (Major vs. minor) | 1.743 (1.123–2.705) p = 0.0150 * | 1.174 (0.7462–1.847) p = 0.4920 | 0.5748 (0.2965–1.114) p = 0.1340 | 0.8097 (0.4578–1.432) p = 0.5615 | 1.437 (1.049–1.969) p = 0.0257 * | 0.8426 (0.6161–1.152) p = 0.3006 | 1.009 (0.6758–1.506) p ≥ 0.9999 | 1.449 (0.9229–2.254) p = 0.0004 *** | 1.942 (1.260–2.994) p = 0.0034 ** |

| Genetic Model | Description of Predisposing Genotypes |

|---|---|

| Co-dominant | Equivalence in the impact of two alleles from a gene pair. |

| Dominant | Alleles that display the same phenotype irrespective of the identity of the paired alleles. |

| Recessive | A phenotype is expressed solely when the paired alleles are identical. |

| Over-dominant | The heterozygote is more effective than the homozygote. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mthembu, M.H.; Sibiya, S.; Mlambo, Z.P.; Mkhwanazi, N.P.; Naicker, T. Asymmetric Dimethylaminohydrolase Gene Polymorphisms Associated with Preeclampsia Comorbid with HIV Infection in Pregnant Women of African Ancestry. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3271. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26073271

Mthembu MH, Sibiya S, Mlambo ZP, Mkhwanazi NP, Naicker T. Asymmetric Dimethylaminohydrolase Gene Polymorphisms Associated with Preeclampsia Comorbid with HIV Infection in Pregnant Women of African Ancestry. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(7):3271. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26073271

Chicago/Turabian StyleMthembu, Mbuso Herald, Samukelisiwe Sibiya, Zinhle Pretty Mlambo, Nompumelelo P. Mkhwanazi, and Thajasvarie Naicker. 2025. "Asymmetric Dimethylaminohydrolase Gene Polymorphisms Associated with Preeclampsia Comorbid with HIV Infection in Pregnant Women of African Ancestry" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 7: 3271. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26073271

APA StyleMthembu, M. H., Sibiya, S., Mlambo, Z. P., Mkhwanazi, N. P., & Naicker, T. (2025). Asymmetric Dimethylaminohydrolase Gene Polymorphisms Associated with Preeclampsia Comorbid with HIV Infection in Pregnant Women of African Ancestry. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(7), 3271. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26073271