FusionAtt: Deep Fusional Attention Networks for Multi-Channel Biomedical Signals

Abstract

1. Introduction

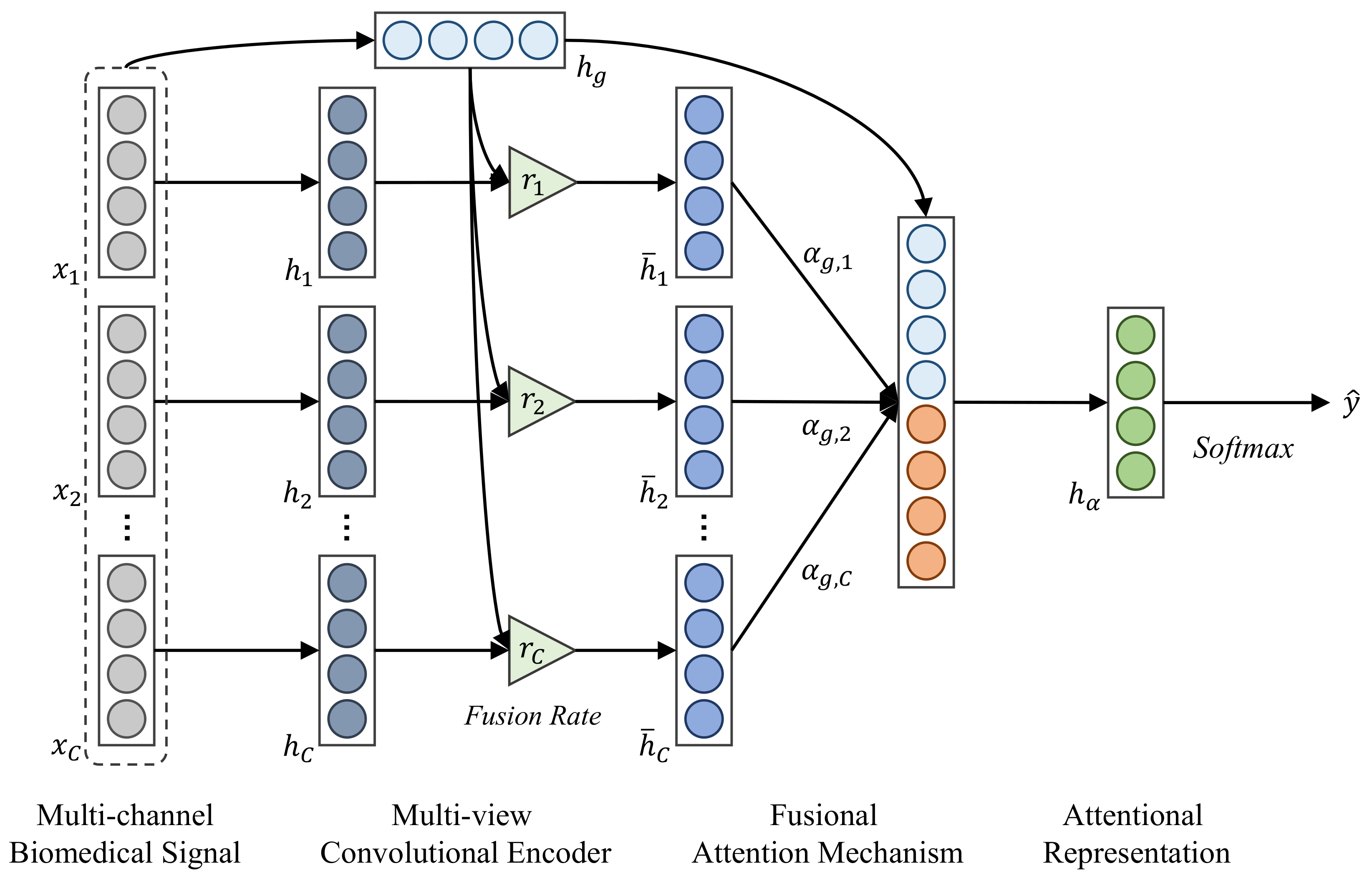

- We propose FusionAtt, a unified fusional attention neural network combined with multi-view convolutional encoder, designed to learn channel-aware representations of multi-channel biosignals.

- FusionAtt dynamically quantifies the importance of each biomedical channel by gated fusion, and relies on more informative ones to enhance feature representation, without prior expert knowledge.

- We empirically show that FusionAtt consistently achieved the best performance compared with nine biosignal feature learning baselines on two clinical datasets, demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed fusional attention mechanism.

2. Related Work

2.1. Deep Learning for Multi-Channel Biosignals

2.2. Attention-Based Neural Networks in Clinical Diagnosis

3. Methodology

3.1. Multi-View Convolutional Encoder

3.2. Fusional Attention Mechanism

3.3. Unified Training Procedure

4. Experiments

4.1. Datasets

4.2. Baseline Approaches

4.3. Implementation Details

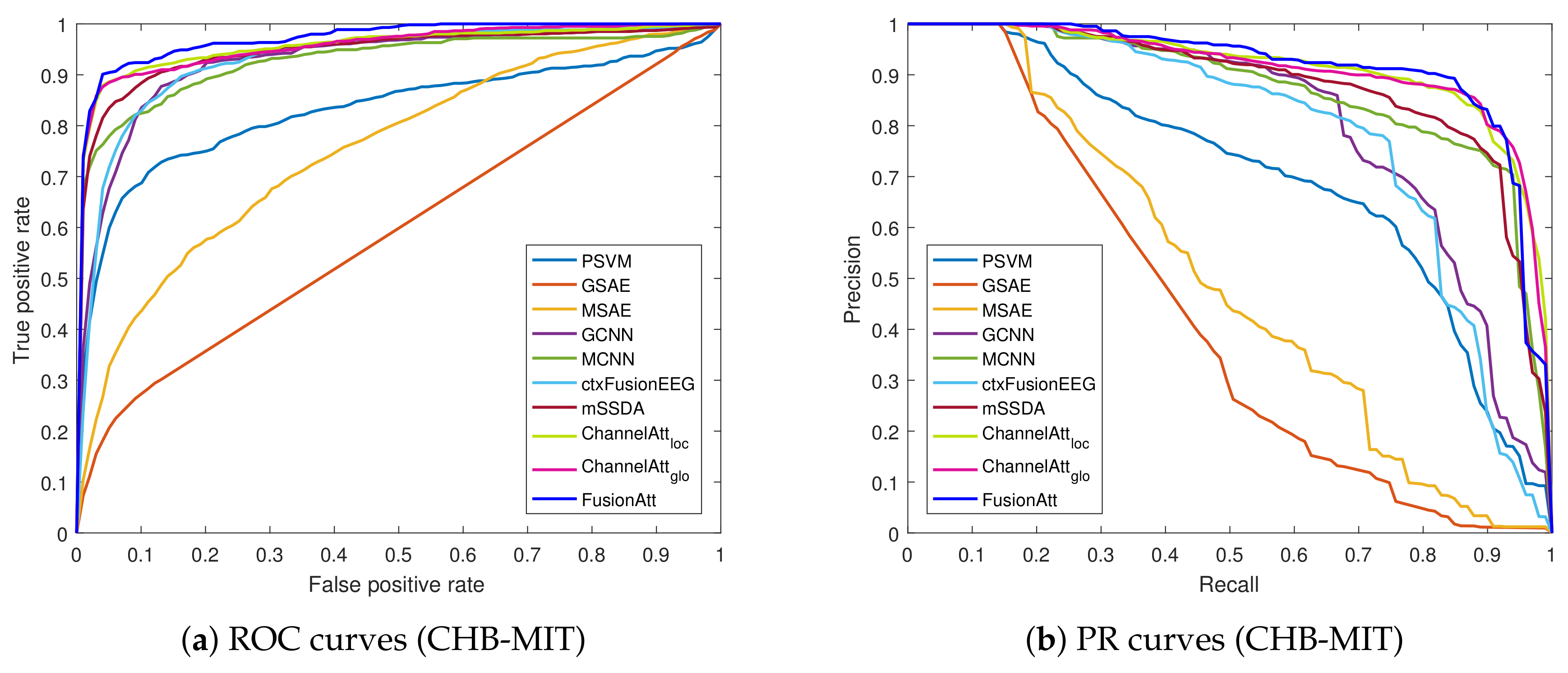

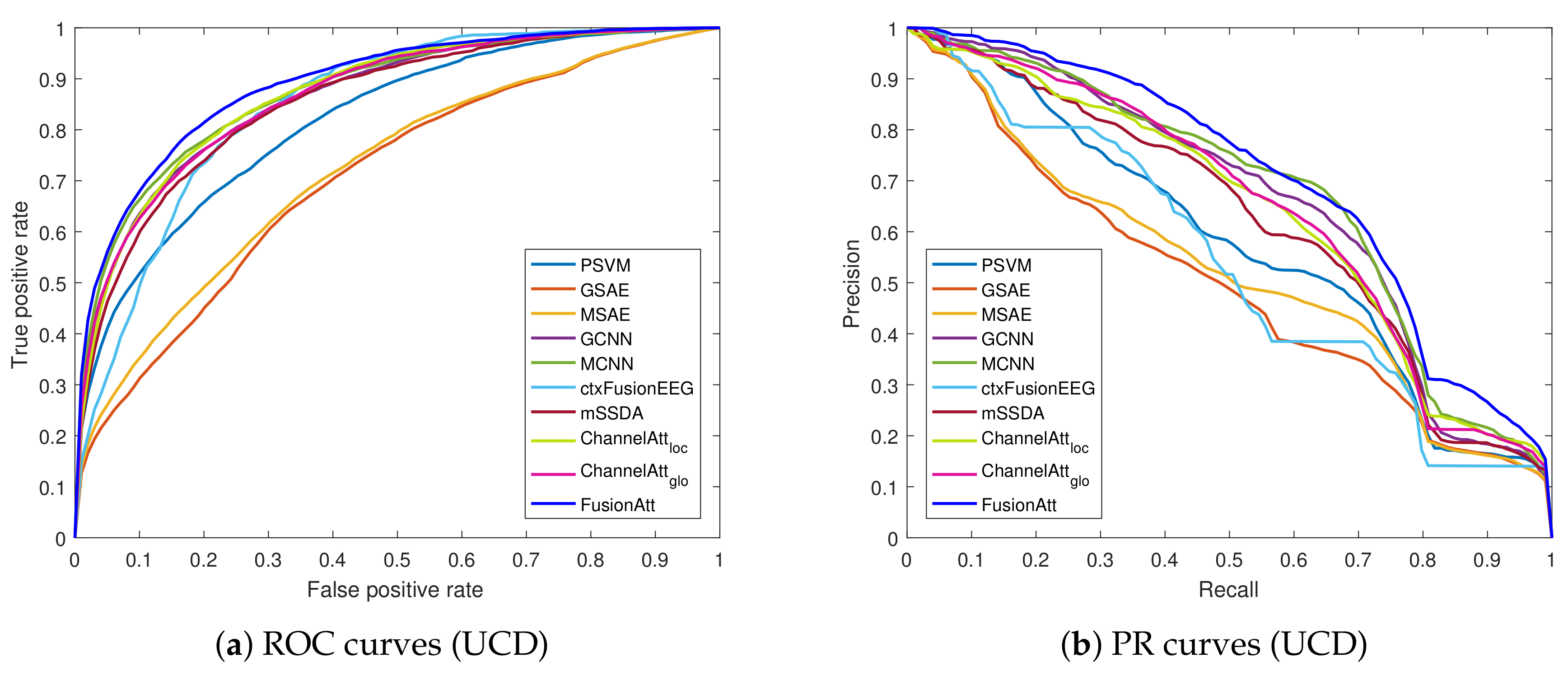

4.4. Performance on Clinical Tasks

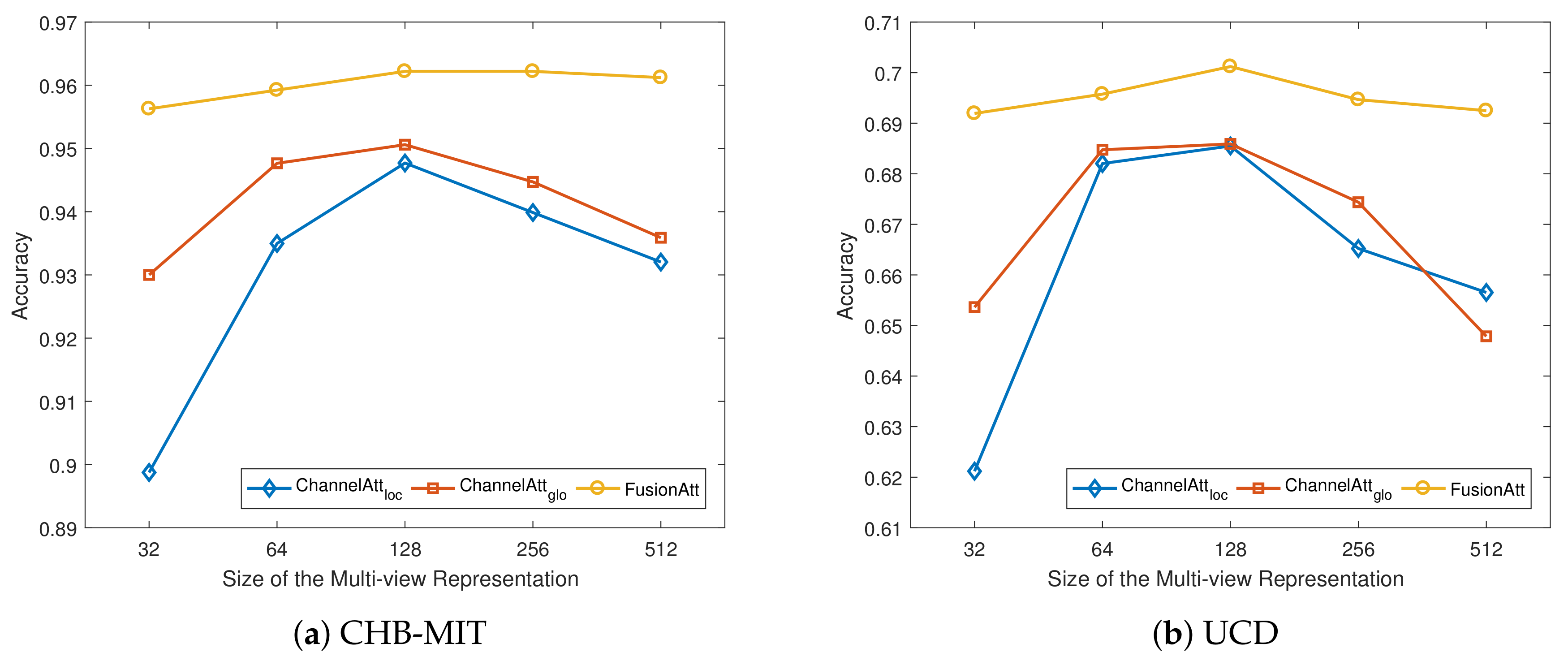

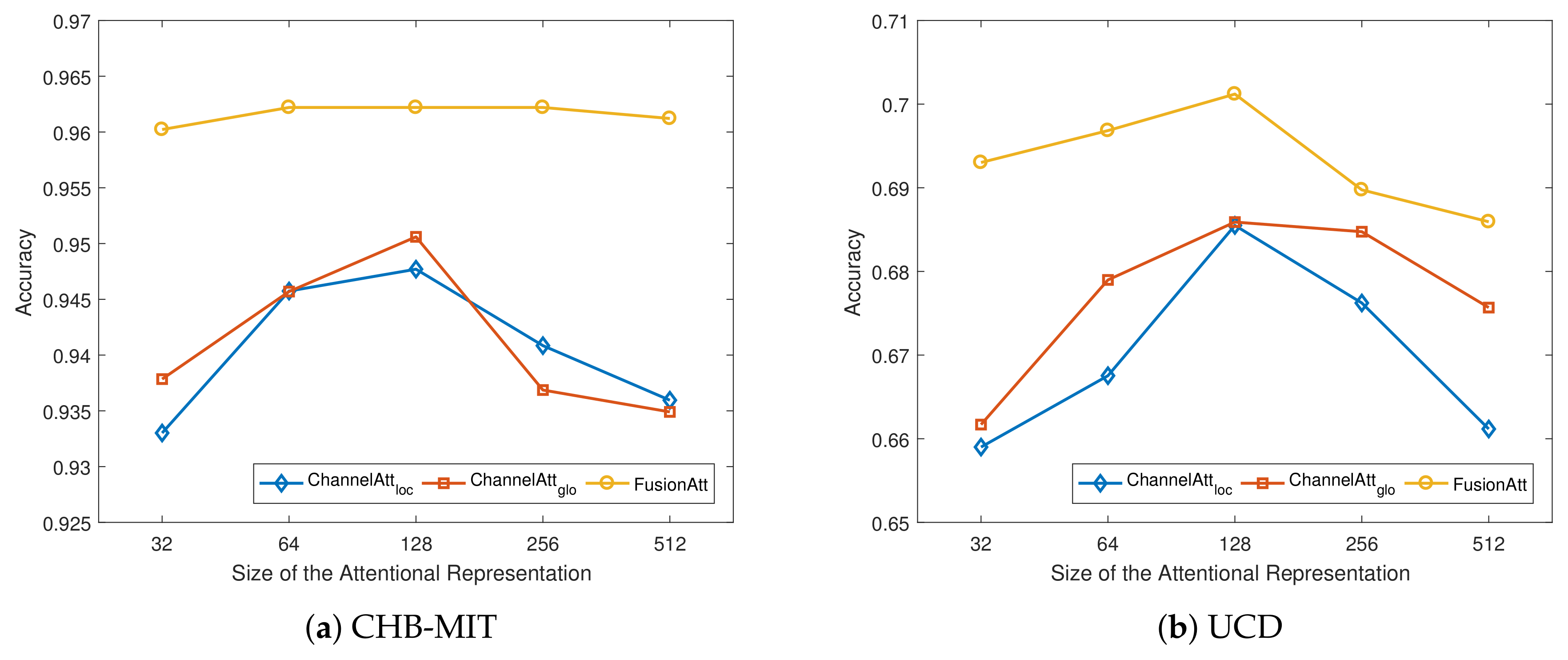

4.5. Sensitivity Analysis

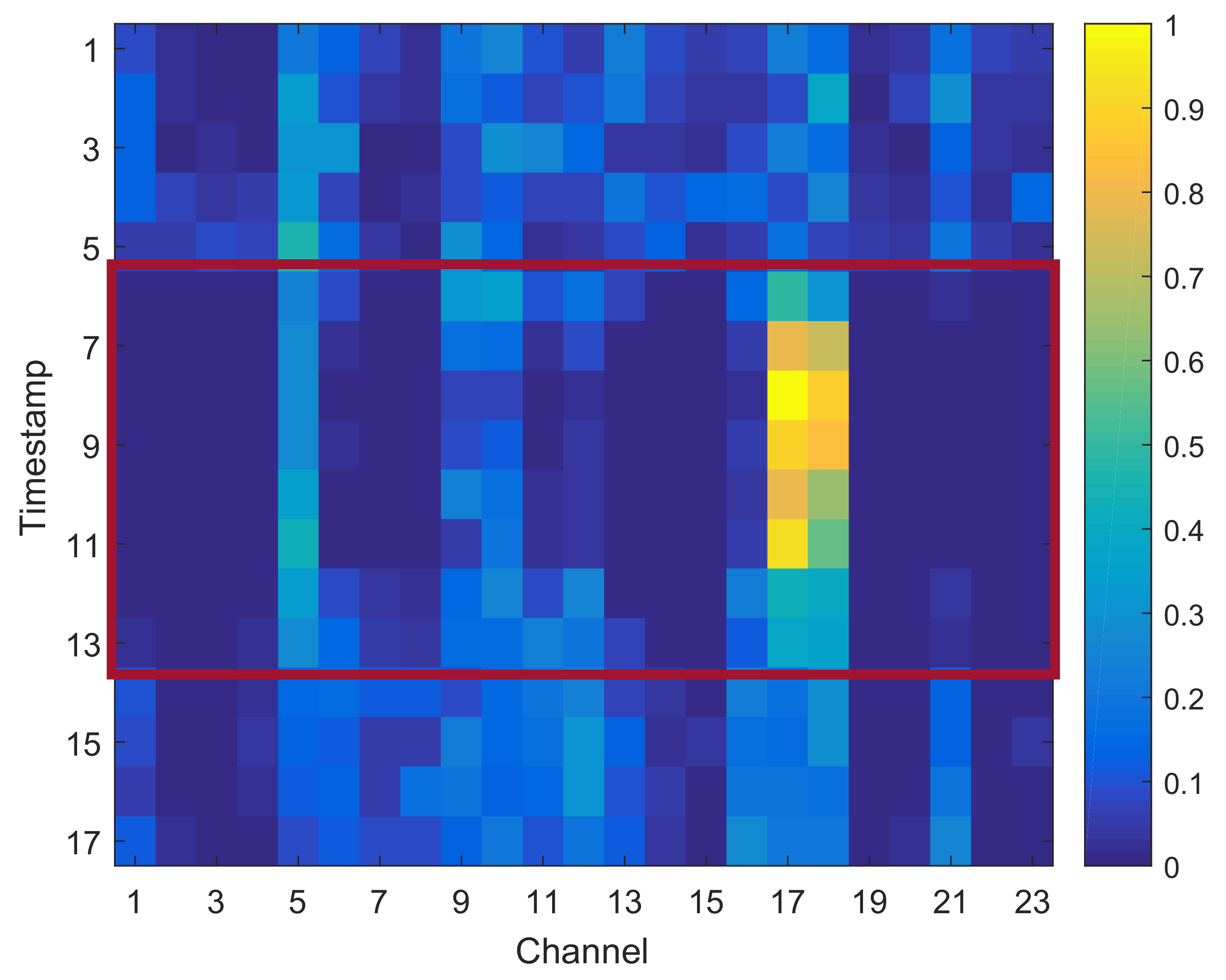

4.6. Case Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Johnson, A.E.; Ghassemi, M.M.; Nemati, S.; Niehaus, K.E.; Clifton, D.A.; Clifford, G.D. Machine learning and decision support in critical care. Proc. IEEE Inst. Electr. Electr. Eng. 2016, 104, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acar, E.; Levin-Schwartz, Y.; Calhoun, V.D.; Adali, T. Tensor-based fusion of EEG and FMRI to understand neurological changes in schizophrenia. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), Baltimore, MD, USA, 28–31 May 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Jia, X.; Xun, G.; Zhang, A. Improving eeg feature learning via synchronized facial video. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), Santa Clara, CA, USA, 29 Octorber–1 November 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 843–848. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Y.; Xun, G.; Jia, K.; Zhang, A. A multi-view deep learning method for epileptic seizure detection using short-time fourier transform. In Proceedings of the 8th ACM International Conference on Bioinformatics, Computational Biology, and Health Informatics, Boston, MA, USA, 20–23 August 2017; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 213–222. [Google Scholar]

- Längkvist, M.; Karlsson, L.; Loutfi, A. A review of unsupervised feature learning and deep learning for time-series modeling. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2014, 42, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supratak, A.; Wu, C.; Dong, H.; Sun, K.; Guo, Y. Survey on feature extraction and applications of biosignals. In Machine Learning for Health Informatics; Springer: Berline, Germany, 2016; pp. 161–182. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, A. Affective state recognition from EEG with deep belief networks. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine, Shanghai, China, 18–21 December 2013; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 305–310. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, X.; Li, K.; Li, X.; Zhang, A. A novel semi-supervised deep learning framework for affective state recognition on eeg signals. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics And Bioengineering, Boca Raton, FL, USA, 10–12 November 2014; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- LeCun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proc. IEEE 1998, 86, 2278–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, Y.; Bai, J.; Chen, F. Automatic sleep stage classification based on sparse deep belief net and combination of multiple classifiers. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control 2016, 38, 435–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Längkvist, M.; Karlsson, L.; Loutfi, A. Sleep stage classification using unsupervised feature learning. Adv. Artif. Neural Syst. 2012, 2012, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xun, G.; Jia, X.; Zhang, A. Detecting epileptic seizures with electroencephalogram via a context-learning model. BMC Med. Inf. Dec. Mak. 2016, 16, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Xun, G.; Jia, K.; Zhang, A. A novel wavelet-based model for eeg epileptic seizure detection using multi-context learning. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), Kansas City, MO, USA, 13–16 November 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 694–699. [Google Scholar]

- Ha, S.; Choi, S. Convolutional neural networks for human activity recognition using multiple accelerometer and gyroscope sensors. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 24–29 July 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 381–388. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, S.; Hu, S.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, A.; Abdelzaher, T. Deepsense: A unified deep learning framework for time-series mobile sensing data processing. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on World Wide Web. International World Wide Web Conferences Steering Committee, Perth, Australia, 3–7 April 2017; pp. 351–360. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, E.; Bahadori, M.T.; Song, L.; Stewart, W.F.; Sun, J. GRAM: graph-based attention model for healthcare representation learning. In Proceedings of the 23rd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Halifax, NS, Canada, 13–17 August 2017; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 787–795. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, F.; Chitta, R.; Zhou, J.; You, Q.; Sun, T.; Gao, J. Dipole: Diagnosis prediction in healthcare via attention-based bidirectional recurrent neural networks. In Proceedings of the 23rd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Halifax, NS, Canada, 13–17 August 2017; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1903–1911. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Y.; Xun, G.; Ma, F.; Suo, Q.; Xue, H.; Jia, K.; Zhang, A. A novel channel-aware attention framework for multi-channel eeg seizure detection via multi-view deep learning. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE EMBS International Conference on Biomedical & Health Informatics (BHI), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 4–7 March 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 206–209. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Xie, X.; Xu, X.; Sun, S. Multi-view learning overview: Recent progress and new challenges. Inf. Fus. 2017, 38, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoeb, A.H. Application of Machine Learning to Epileptic Seizure Onset Detection and Treatment. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Y.; Xun, G.; Suo, Q.; Jia, K.; Zhang, A. Wave2vec: Learning deep representations for biosignals. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining (ICDM), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–21 November 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1159–1164. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberger, A.L.; Amaral, L.A.; Glass, L.; Hausdorff, J.M.; Ivanov, P.C.; Mark, R.G.; Mietus, J.E.; Moody, G.B.; Peng, C.K.; Stanley, H.E. PhysioBank, PhysioToolkit, and PhysioNet: Components of a new research resource for complex physiologic signals. Circulation 2000, 101, e215–e220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortes, C.; Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Mach. Learn. 1995, 20, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, I. Principal Component Analysis; Springer: Berline, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton, G.E.; Salakhutdinov, R.R. Reducing the dimensionality of data with neural networks. Science 2006, 313, 504–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cell No. | Conv | Non-linear | Pooling |

|---|---|---|---|

| ReLU | 6 | ||

| ReLU | 3 | ||

| ReLU | 3 | ||

| ReLU | |||

| ReLU | |||

| ReLU |

| Method | Seizure Detection (CHB-MIT) | Sleep Stage Classification (UCD) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC-ROC | AUC-PR | F1-Score | Accuracy | AUC-ROC | AUC-PR | F1-Score | Accuracy | |

| PSVM | 0.8291 | 0.7021 | 0.6421 | 0.8768 | 0.8177 | 0.5764 | 0.5204 | 0.6193 |

| GSAE | 0.5934 | 0.4180 | 0.0668 | 0.7987 | 0.7068 | 0.4965 | 0.2760 | 0.4917 |

| MSAE | 0.7529 | 0.4937 | 0.1479 | 0.8013 | 0.7213 | 0.5224 | 0.3542 | 0.5262 |

| GCNN | 0.9255 | 0.8054 | 0.7506 | 0.8849 | 0.8655 | 0.6589 | 0.5042 | 0.6270 |

| MCNN | 0.9263 | 0.8702 | 0.7959 | 0.9088 | 0.8732 | 0.6725 | 0.5925 | 0.6590 |

| CtxFusionEEG | 0.9287 | 0.7833 | 0.7202 | 0.9025 | 0.8483 | 0.5330 | 0.4680 | 0.6688 |

| mSSDA | 0.9450 | 0.8801 | 0.8186 | 0.9364 | 0.8544 | 0.6208 | 0.5969 | 0.6741 |

| ChannelAtt | 0.9554 | 0.9134 | 0.8625 | 0.9477 | 0.8699 | 0.6370 | 0.5890 | 0.6855 |

| ChannelAtt | 0.9556 | 0.9119 | 0.8675 | 0.9506 | 0.8662 | 0.6458 | 0.6137 | 0.6859 |

| FusionAtt | 0.9701 | 0.9145 | 0.8953 | 0.9622 | 0.8894 | 0.7021 | 0.6637 | 0.7257 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yuan, Y.; Jia, K. FusionAtt: Deep Fusional Attention Networks for Multi-Channel Biomedical Signals. Sensors 2019, 19, 2429. https://doi.org/10.3390/s19112429

Yuan Y, Jia K. FusionAtt: Deep Fusional Attention Networks for Multi-Channel Biomedical Signals. Sensors. 2019; 19(11):2429. https://doi.org/10.3390/s19112429

Chicago/Turabian StyleYuan, Ye, and Kebin Jia. 2019. "FusionAtt: Deep Fusional Attention Networks for Multi-Channel Biomedical Signals" Sensors 19, no. 11: 2429. https://doi.org/10.3390/s19112429

APA StyleYuan, Y., & Jia, K. (2019). FusionAtt: Deep Fusional Attention Networks for Multi-Channel Biomedical Signals. Sensors, 19(11), 2429. https://doi.org/10.3390/s19112429