3D Transparent Object Detection and Reconstruction Based on Passive Mode Single-Pixel Imaging

Abstract

:1. Introduction

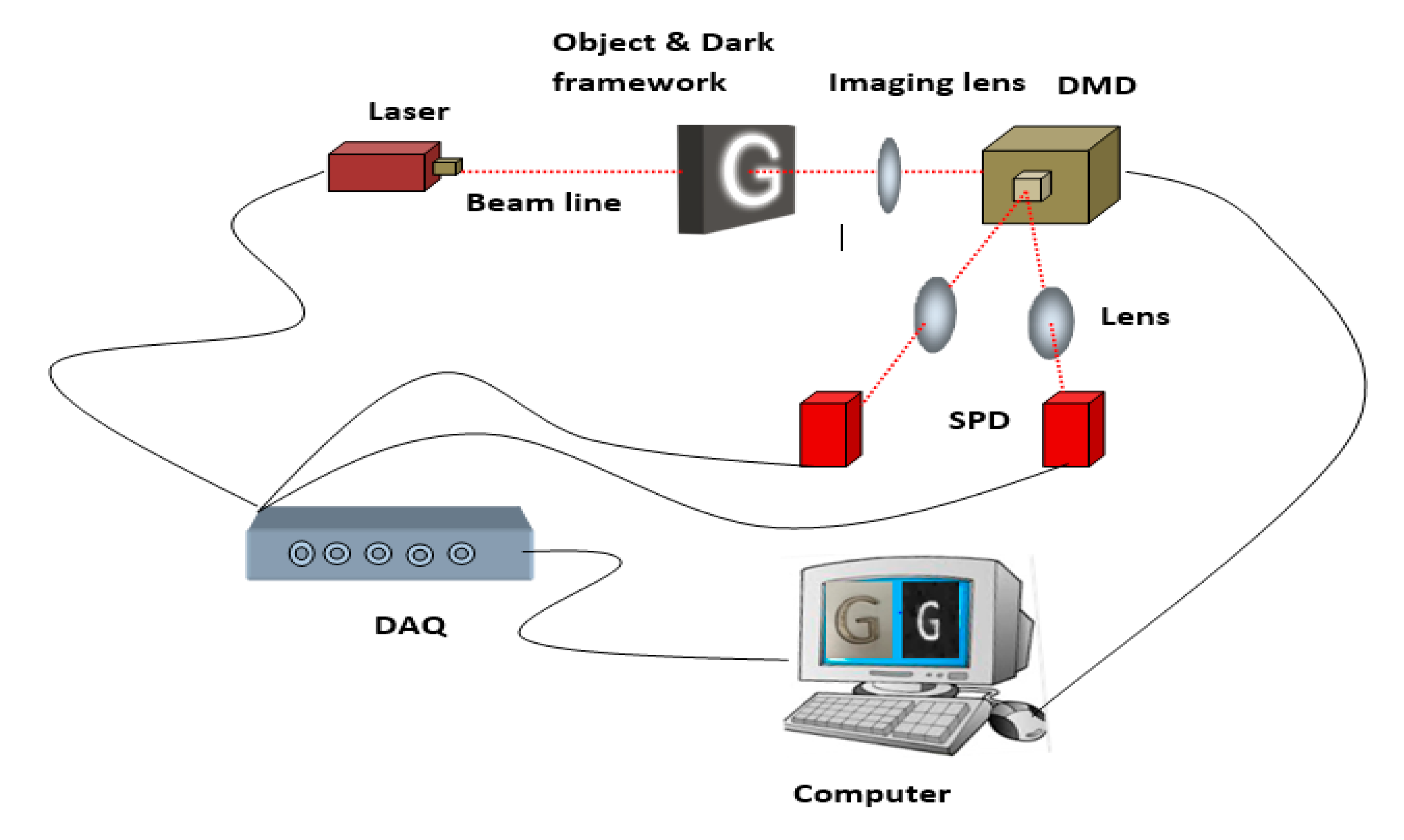

2. Experimental Setup

3. 3D Transparent Object Reconstruction

3.1. 2D Image Reconstruction

3.2. Disparity Map Using Normalized Cross-Correlation (NCC)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, M.; Chang, Y.; Aziz, E.-S.; Esche, S.K.; Chassapis, C. Real-Time 3D Model Reconstruction and Interaction Using Kinect for a Game-Based Virtual Laboratory. In ASME 2013 International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition; American Society of Mechanical Engineers Digital Collection: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kutulakos, K.N.; Steger, E. A theory of refractive and specular 3D shape by light-path triangulation. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2008, 76, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zheng, J.Y.; Murata, A. Acquiring 3D object models from specular motion using circular lights illumination. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Computer Vision (IEEE Cat. No. 98CH36271), Bombay, India, 7 January 1998; IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hullin, M.B.; Fuchs, M.; Ihrke, I.; Seidel, H.P.; Lensch, H.P. Fluorescent immersion range scanning. ACM Trans. Graph. 2008, 27, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rantoson, R.; Stolz, C.; Fofi, D.; Mériaudeau, F. 3D reconstruction of transparent objects exploiting surface fluorescence caused by UV irradiation. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing, Hong Kong, China, 26–29 September 2010; IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Qiao, Y.; Qiu, B. Reconstructing the surface of transparent objects by polarized light measurements. Opt. Express 2017, 25, 26296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alt, N.; Rives, P.; Steinbach, E. Reconstruction of transparent objects in unstructured scenes with a depth camera. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing, Melbourne, Austrilia, 15–18 September 2013; IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 4131–4135. [Google Scholar]

- Klank, U.; Carton, D.; Beetz, M. Transparent object detection and reconstruction on a mobile platform. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Shanghai, China, 9–13 May 2011; pp. 5971–5978. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, L.; Ohno, K.; Takeuchi, E.; Tadokoro, S. Transparent object detection using color image and laser reflectance image for mobile manipulator. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Biomimetics, Phuket, Thailand, 7–11 December 2011; IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier, J.-F.; Maldague, X. Shape from heating: A two-dimensional approach for shape extraction in infrared images. OptEn 1997, 36, 370–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eren, G.; Aubreton, O.; Meriaudeau, F.; Secades, L.A.S.; Fofi, D.; Naskali, A.T.; Ercil, A. Scanning from heating: 3D shape estimation of transparent objects from local surface heating. Opt. Express 2009, 17, 11457–11468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Katz, O.; Small, E.; Bromberg, Y.; Silberberg, Y. Focusing and compression of ultrashort pulses through scattering media. Nat. Photonics 2011, 5, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, M.P.; Gibson, G.M.; Bowman, R.W.; Sun, B.; Radwell, N.; Mitchell, K.J.; Padgett, M.J. Simultaneous real-time visible and infrared video with single-pixel detectors. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 10669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, G.M.; Sun, B.; Edgar, M.P.; Phillips, D.B.; Hempler, N.; Maker, G.T.; Padgett, M.J. Real-time imaging of methane gas leaks using a single-pixel camera. Opt. Express 2017, 25, 2998–3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, N.; Huynh, N.; Zhang, E.; Betcke, M.; Arridge, S.; Beard, P.; Cox, B. Single-pixel optical camera for video rate ultrasonic imaging. Optica 2016, 3, 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.F.; Atkinson, G.A.; Smith, L.N.; Smith, M.L. 3D face reconstructions from photometric stereo using near infrared and visible light. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2010, 114, 942–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.-J.; Edgar, M.P.; Gibson, G.M.; Sun, B.; Radwell, N.; Lamb, R.; Padgett, M.J. Single-pixel three-dimensional imaging with time-based depth resolution. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, M.-J.; Zhang, J.-M. Single-pixel imaging and its application in three-dimensional reconstruction: A brief review. Sensors 2019, 19, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shrekenhamer, D.; Watts, C.M.; Padilla, W.J. Terahertz single pixel imaging with an optically controlled dynamic spatial light modulator. Opt. Express 2013, 21, 12507–12518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerboukha, H.; Nallappan, K.; Skorobogatiy, M. Toward real-time terahertz imaging. Adv. Opt. Photonics 2018, 10, 843–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, J.; Krishnamurthy, K.; Brady, D.J. Compressive single-pixel snapshot x-ray diffraction imaging. Opt. Lett. 2014, 39, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erkmen, B.I. Computational ghost imaging for remote sensing. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 2012, 29, 782–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Xie, Z.; Liu, Z.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, S. Multiple-image encryption based on computational ghost imaging. Opt. Commun. 2016, 359, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Jiang, H.; Matthews, K.; Wilford, P. Lensless imaging by compressive sensing. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 15–18 September 2013; IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, X.; Zhong, J. Shadow-free single-pixel imaging. Opt. Commun. 2017, 403, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, L.; Suo, J.; Situ, G.; Li, Z.; Fan, J.; Chen, F.; Dai, Q. Multispectral imaging using a single bucket detector. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aspden, R.S.; Gemmell, N.R.; Morris, P.A.; Tasca, D.S.; Mertens, L.; Tanner, M.G.; Kirkwood, R.A.; Ruggeri, A.; Tosi, A.; Boyd, R.W.; et al. Photon-sparse microscopy: Visible light imaging using infrared illumination. Optica 2015, 2, 1049–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tajahuerce, E.; Durán, V.; Clemente, P.; Irles, E.; Soldevila, F.; Andrés, P.; Lancis, J. Image transmission through dynamic scattering media by single-pixel photodetection. Opt. Express 2014, 22, 16945–16955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Duarte, M.; Davenport, M.A.; Takbar, D.; Laska, J.N.; Sun, T.; Kelly, K.F.; Baraniuk, R.G. Single-pixel imaging via compressive sampling. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2008, 25, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sun, M.-J.; Xu, Z.-H.; Wu, L.-A. Collective noise model for focal plane modulated single-pixel imaging. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2018, 100, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, S.; Peng, J.; Yao, M.; Zheng, G.; Zhong, J. Simultaneous spatial, spectral, and 3D compressive imaging via efficient Fourier single-pixel measurements. Optica 2018, 5, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, F.; Araújo, F.M.; Correia, M.; Abolbashari, M.; Farahi, F. Active illumination single-pixel camera based on compressive sensing. Appl. Opt. 2011, 50, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bertolotti, J.; Van Putten, E.G.; Blum, C.; Lagendijk, A.; Vos, W.L.; Mosk, A.P. Non-invasive imaging through opaque scattering layers. Nature 2012, 491, 232–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, V.; Soldevila, F.; Irles, E.; Clemente, P.; Tajahuerce, E.; Andrés, P.; Lancis, J. Compressive imaging in scattering media. Opt. Express 2015, 23, 14424–14433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrocal, E.; Pettersson, S.-G.; Kristensson, E. High-contrast imaging through scattering media using structured illumination and Fourier filtering. Opt. Lett. 2016, 41, 5612–5615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winters, D.G.; Bartels, R.A. Two-dimensional single-pixel imaging by cascaded orthogonal line spatial modulation. Opt. Lett. 2015, 40, 2774–2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Edgar, M.P.; Bowman, R.W.; Vittert, L.E.; Welsh, S.; Bowman, A.; Padgett, M.J. 3D Computational Imaging with Single-Pixel Detectors. Science 2013, 340, 844–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yu, W.-K.; Yao, X.R.; Liu, X.F.; Li, L.Z.; Zhai, G.J. Three-dimensional single-pixel compressive reflectivity imaging based on complementary modulation. Appl. Opt. 2015, 54, 363–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirmani, A.; Venkatraman, D.; Shin, D.; Colaço, A.; Wong, F.N.C.; Shapiro, J.H.; Goyal, V.K. First-Photon Imaging. Science 2013, 343, 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howland, G.A.; Dixon, P.B.; Howell, J.C. Photon-counting compressive sensing laser radar for 3D imaging. Appl. Opt. 2011, 50, 5917–5920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McCarthy, A.; Krichel, N.J.; Gemmell, N.R.; Ren, X.; Tanner, M.G.; Dorenbos, S.N.; Zwiller, V.; Hadfield, R.H.; Buller, G. Kilometer-range, high resolution depth imaging via 1560 nm wavelength single-photon detection. Opt. Express 2013, 21, 8904–8915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Howland, G.A.; Lum, D.J.; Ware, M.R.; Howell, J.C. Photon counting compressive depth mapping. Opt. Express 2013, 21, 23822–23837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.; Edgar, M.P.; Sun, B.; Radwell, N.; Gibson, G.M.; Padgett, M.J. 3D single-pixel video. J. Opt. 2016, 18, 35203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldevila, F.; Salvador-Balaguer, E.; Clemente, P.; Tajahuerce, E.; Lancis, J. High-resolution adaptive imaging with a single photodiode. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gribben, J.; Boate, A.R.; Boukerche, A. Emerging Digital Micromirror Device Based Systems and Applications IX, Calibration for 3D Imaging with a Single-Pixel Camera; International Society for Optics and Photonics: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z. Flexible Camera Calibration by Viewing a Plane from Unknown Orientations. In Proceedings of the Seventh IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Kerkyra, Greece, 20–27 September 1999; IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Edgar, M.P.; Gibson, G.M.; Padgett, M.J. Principles and prospects for single-pixel imaging. Nat. Photon 2018, 13, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.-J.; Edgar, M.P.; Phillips, D.B.; Gibson, G.M.; Padgett, M.J. Improving the signal-to-noise ratio of single-pixel imaging using digital microscanning. Opt. Express 2016, 24, 10476–10485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Candès, E.J.; Romberg, J.K.; Tao, T. Stable signal recovery from incomplete and inaccurate measurements. Commun. Pure Appl. Math. 2006, 59, 1207–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mathai, A.; Guo, N.; Liu, D.; Wang, X. 3D Transparent Object Detection and Reconstruction Based on Passive Mode Single-Pixel Imaging. Sensors 2020, 20, 4211. https://doi.org/10.3390/s20154211

Mathai A, Guo N, Liu D, Wang X. 3D Transparent Object Detection and Reconstruction Based on Passive Mode Single-Pixel Imaging. Sensors. 2020; 20(15):4211. https://doi.org/10.3390/s20154211

Chicago/Turabian StyleMathai, Anumol, Ningqun Guo, Dong Liu, and Xin Wang. 2020. "3D Transparent Object Detection and Reconstruction Based on Passive Mode Single-Pixel Imaging" Sensors 20, no. 15: 4211. https://doi.org/10.3390/s20154211

APA StyleMathai, A., Guo, N., Liu, D., & Wang, X. (2020). 3D Transparent Object Detection and Reconstruction Based on Passive Mode Single-Pixel Imaging. Sensors, 20(15), 4211. https://doi.org/10.3390/s20154211