An Electrochemical Ti3C2Tx Aptasensor for Sensitive and Label-Free Detection of Marine Biological Toxins

Abstract

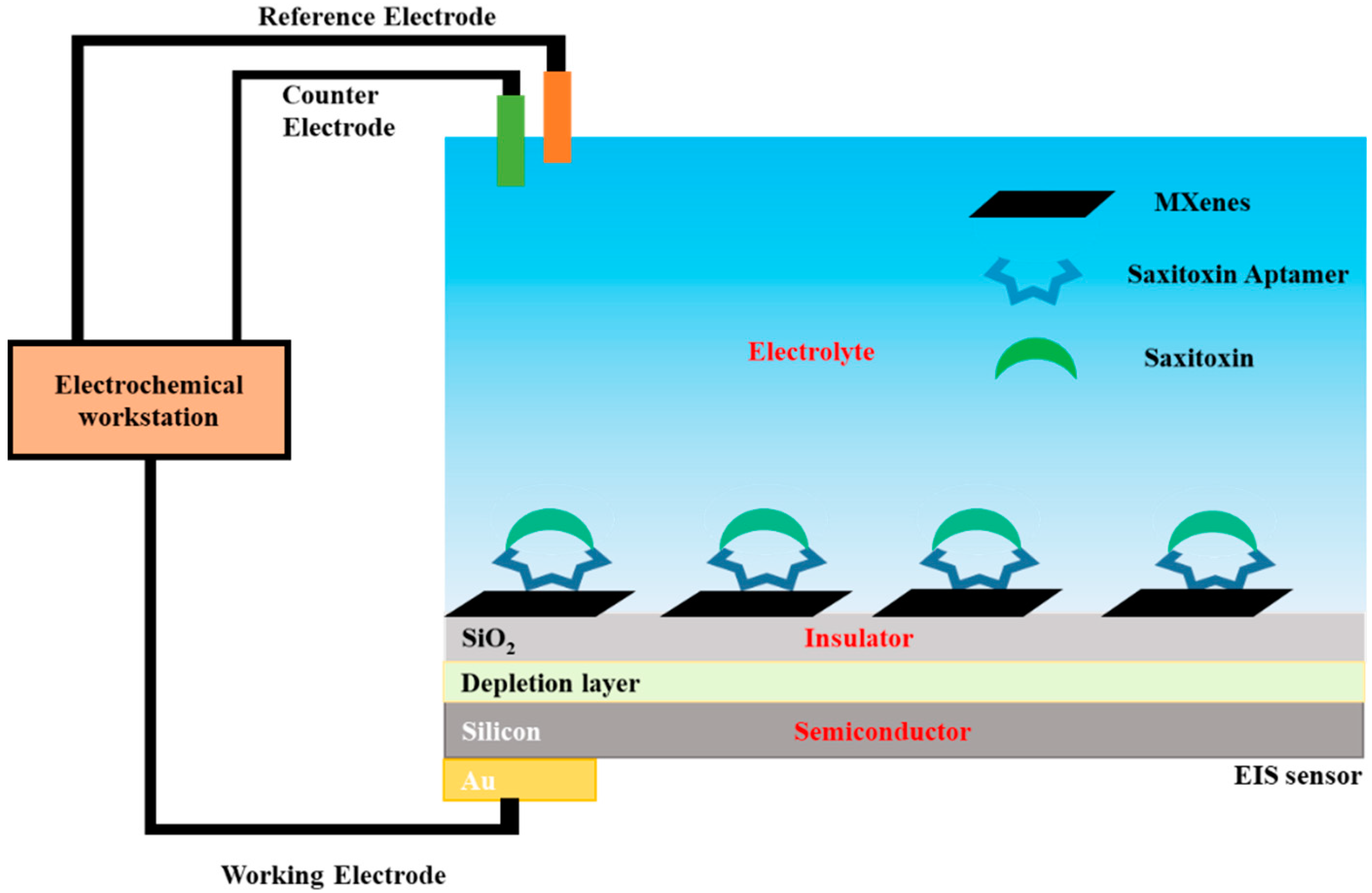

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. MXene Synthesis

2.2. Sensor Preparation and Functionalization

2.3. Measurements

2.4. Characterization

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of Aptamer Modified MXene

3.2. Real-Time Monitoring of STX

3.3. STX Detection

3.4. Selectivity and Stability of the Sensor

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schantz, E.J.; Mold, J.D.; Stanger, D.W.; Shavel, J.; Riel, F.J.; Bowden, J.P.; Lynch, J.M.; Wyler, R.S.; Riegel, B.; Sommer, H.J. Paralytic shellfish poison. VI. A procedure for the isolation and purification of the poison from toxic clam and mussel tissues. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1957, 79, 5230–5235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiese, M.; D’agostino, P.M.; Mihali, T.K.; Moffitt, M.C.; Neilan, B.A. Neurotoxic alkaloids: Saxitoxin and its analogs. Mar. Drugs 2010, 8, 2185–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Falconer, I.R.; Humpage, A.R. Health risk assessment of cyanobacterial (blue-green algal) toxins in drinking water. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2005, 2, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Faber, S. Saxitoxin and the induction of paralytic shellfish poisoning. J. Young Investig. 2012, 23, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Capper, A.; Flewelling, L.J.; Arthur, K. Dietary exposure to harmful algal bloom (HAB) toxins in the endangered manatee (Trichechus manatus latirostris) and green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas) in Florida, USA. Harmful Algae 2013, 28, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, P. Textbook of Adult Emergency Medicine. Emerg. Med. J. 2001, 18, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chorus, I. Current Approaches to Cyanotoxin Risk Assessment, Risk Management and Regulations in Different Countries; Federal Environmental Agency: Radolfzell, Germany, 2012; pp. 29–70. [Google Scholar]

- Vilariño, N.; Louzao, M.C.; Vieytes, M.R.; Botana, L.M. Biological methods for marine toxin detection. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2010, 397, 1673–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCall, J.R.; Holland, W.C.; Keeler, D.M.; Hardison, D.R.; Litaker, R.W. Improved Accuracy of Saxitoxin Measurement Using an Optimized Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay. Toxins 2019, 11, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Leira, F.; Alvarez, C.; Cabado, A.G.; Vieites, J.M.; Vieytes, M.R.; Botana, L.M. Development of a F actin-based live-cell fluorimetric microplate assay for diarrhetic shellfish toxins. Anal. Biochem. 2003, 317, 129–135. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Yu, R.-C.; Kong, F.-Z.; Chen, Z.-F.; Dai, L.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, Q.-C.; Wang, Y.-F.; Yan, T.; Zhou, M.-J. Paralytic shellfish toxins in phytoplankton and shellfish samples collected from the Bohai Sea, China. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 115, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya, S.; Cho, Y.; Konoki, K.; Nagasawa, K.; Oshima, Y.; Yotsu-Yamashita, M. Synthesis and identification of proposed biosynthetic intermediates of saxitoxin in the cyanobacterium Anabaena circinalis (TA04) and the dinoflagellate Alexandrium tamarense (Axat-2). Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014, 12, 3016–3020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regueiro, J.; Rossignoli, A.E.; Álvarez, G.; Blanco, J. Automated on-line solid-phase extraction coupled to liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry for determination of lipophilic marine toxins in shellfish. Food Chem. 2011, 129, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, R.; Kanamori, M.; Yoshida, H.; Okumura, Y.; Uchida, H.; Matsushima, R.; Oikawa, H.; Suzuki, T. Development of Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography with Post-Column Fluorescent Derivatization for the Rapid Detection of Saxitoxin Analogues and Analysis of Bivalve Monitoring Samples. Toxins 2019, 11, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Petropoulos, K.; Bodini, S.F.; Fabiani, L.; Micheli, L.; Porchetta, A.; Piermarini, S.; Volpe, G.; Pasquazzi, F.M.; Sanfilippo, L.; Moscetta, P. Re-modeling ELISA kits embedded in an automated system suitable for on-line detection of algal toxins in seawater. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2019, 283, 865–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juska, V.B.; Pemble, M.E. A critical review of electrochemical glucose sensing: Evolution of biosensor platforms based on advanced nanosystems. Sensors 2020, 20, 6013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Wu, C.; Cai, H.; Hu, N.; Zhou, J.; Wang, P. Cell-based biosensors and their application in biomedicine. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 6423–6461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaban, S.M.; Kim, D.-H. Recent Advances in Aptamer Sensors. Sensors 2021, 21, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pultar, J.; Sauer, U.; Domnanich, P.; Preininger, C. Bioelectronics, Aptamer–antibody on-chip sandwich immunoassay for detection of CRP in spiked serum. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2009, 24, 1456–1461. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Shen, S.; Lau, C.; Lu, J. A conformational switch-based fluorescent biosensor for homogeneous detection of telomerase activity. Talanta 2019, 199, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, I.M.; Kontoravdi, C.; Polizzi, K.M. Bioelectronics, Low-cost and user-friendly biosensor to test the integrity of mRNA molecules suitable for field applications. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 137, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tertis, M.; Leva, P.I.; Bogdan, D.; Suciu, M.; Graur, F.; Cristea, C. Bioelectronics, Impedimetric aptasensor for the label-free and selective detection of Interleukin-6 for colorectal cancer screening. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 137, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, S.; Zhou, L.; Cheng, Y.; Fang, J. An ssDNA aptamer selected by Cell-SELEX for the targeted imaging of poorly differentiated gastric cancer tissue. Talanta 2019, 199, 634–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goud, K.Y.; Kailasa, S.K.; Kumar, V.; Tsang, Y.F.; Gobi, K.V.; Kim, K.-H. Bioelectronics, Progress on nanostructured electrochemical sensors and their recognition elements for detection of mycotoxins: A review. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018, 121, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Q.; Xin, X.; Du, B.; Wu, D.; Han, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Cai, Y.; Li, R.; Yang, M.; Li, H. Bioelectronics, Electrochemical immunosensor for norethisterone based on signal amplification strategy of graphene sheets and multienzyme functionalized mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2010, 26, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, K.; Li, Z.; Lin, J.; Han, G.; Huang, P. Two-dimensional transition metal carbides and nitrides (MXenes) for biomedical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 5109–5124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naguib, M.; Mochalin, V.N.; Barsoum, M.W.; Gogotsi, Y. 25th anniversary article: MXenes: A new family of two-dimensional materials. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 992–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Shen, P.J. Are MXenes promising anode materials for Li ion batteries? Computational studies on electronic properties and Li storage capability of Ti3C2 and Ti3C2X2 (X = F, OH) monolayer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 16909–16916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Ha, E.; Zhao, G.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, D.; Yue, G.; Hu, L.; Sun, N.; Wang, Y.; Lee, L.Y.S.; et al. Recent advance in MXenes: A promising 2D material for catalysis, sensor and chemical adsorption. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017, 352, 306–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, Y. Potential environmental applications of MXenes: A critical review. Chemosphere 2021, 271, 129578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.; Liu, B.; Qiu, H.; Shi, X.; Cao, X.; Gu, J. MXenes for polymer matrix electromagnetic interference shielding composites: A review. Compos. Commun. 2021, 24, 100653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, F.; Liu, Y. Ti3C2 MXenes nanosheets catalyzed highly efficient electrogenerated chemiluminescence biosensor for the detection of exosomes. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 124, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Wang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, Y. In situ formation of gold nanoparticles decorated Ti3C2 MXenes nanoprobe for highly sensitive electrogenerated chemiluminescence detection of exosomes and their surface proteins. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 5546–5553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, G.; Yang, B.; Chen, R.; Zhou, K.; Han, S.; Zhou, Y. MXenes for memristive and tactile sensory systems. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2021, 8, 011316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Kong, S.; Chen, F.; Cai, W.; Wang, J.; Du, L.; Huang, Y.; Wu, C. Delaminated Ti3C2Tx flake as an effective UV-protective material for living cells. Mater. Lett. 2020, 260, 126972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Wang, J.; Du, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, F.; Chen, W.; Cai, W.; Wu, C.; Wang, P. Bioelectronics, Functional expression of olfactory receptors using cell-free expression system for biomimetic sensors towards odorant detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 130, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, C.; Cao, Y.; Wang, G. Functional MXene Materials: Progress of Their Applications. Chem. Asian J. 2018, 13, 2742–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riazi, H.; Anayee, M.; Hantanasirisakul, K.; Shamsabadi, A.A.; Anasori, B.; Gogotsi, Y.; Soroush, M. Surface Modification of a MXene by an Aminosilane Coupling Agent. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 7, 1902008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Yu, B.; Wei, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ye, S. Efficient removal of Pb(II) by Ti3C2Tx powder modified with a silane coupling agent. J. Mater. Sci. 2019, 54, 13283–13297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhu, H.; Lv, T.; Lin, Q.; Hou, H.; Li, Y.; Wu, Q.; Cui, C. The effect of amino-terminated hyperbranched polymers on the impact resistance of epoxy resins. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2016, 294, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronder, T.S.; Poghossian, A.; Scheja, S.; Wu, C.; Keusgen, M.; Mewes, D.; Schöning, M.J. DNA Immobilization and Hybridization Detection by the Intrinsic Molecular Charge Using Capacitive Field-Effect Sensors Modified with a Charged Weak Polyelectrolyte Layer. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 20068–20075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, L.; Yin, Y.; Fu, W.; Qiu, B.; Lin, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zheng, L.; Li, J.; Chen, G. Determination of paralytic shellfish poisoning toxins by HILIC–MS/MS coupled with dispersive solid phase extraction. Food Chem. 2013, 137, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.-J.; Park, J.-H.; Lee, B.; Kim, M.-G. Label-Free Direct Detection of Saxitoxin Based on a Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance Aptasensor. Toxins 2019, 11, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheng, S.; Zheng, B.; Yao, D.; Wang, Y.; Tian, J.; Liu, L.; Liang, H.; Ding, Y. Determination of Saxitoxin by Aptamer-based surface-enhanced Raman scattering. Anal. Lett. 2019, 52, 902–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Yan, X.; Zhao, L.; Huang, Y.; Wang, S.; Liang, X. A facile label-free electrochemical aptasensor constructed with nanotetrahedron and aptamer-triplex for sensitive detection of small molecule: Saxitoxin. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2020, 858, 113805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Zheng, B.; Yao, D.; Kuai, S.; Tian, J.; Liang, H.; Ding, Y. Study of the binding way between saxitoxin and its aptamer and a fluorescent aptasensor for detection of saxitoxin. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2018, 204, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Jiang, L.; Song, Y.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wu, X.; Tang, D. Amperometric aptasensor for saxitoxin using a gold electrode modified with carbon nanotubes on a self-assembled monolayer, and methylene blue as an electrochemical indicator probe. Microchim. Acta 2016, 183, 1971–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Methods | Detection Limit | Incubation Time | Linear Range (nM) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HILIC-MS/MS | 5.69 nM | 30 min | 27.1–754.2 | 42 |

| LSPR aptasensor | 8.23 nM | 30 min | 16.7–33,445 | 43 |

| SERS aptasensor | 11.7 nM | 30 min | 10–200 | 44 |

| Electrochemical aptasensor | 0.92 nM | 30 min | 1–400 | 45 |

| Fluorescence aptasensor | 10.0 nM | 30 min | 0–80.3 | 46 |

| Electrochemical aptasensor | 0.38 nM | 30 min | 0.9–30 | 47 |

| Electrochemical aptasensor | 0.03 nM | 60 min | 1.0–200 | This work |

| Detection in Buffer (Potential Shifts, V) | Detection in Mussel Tissue Extraction (Potential Shifts, V) | Rate of Recovery (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSTX = 100 nM | 0.169 ± 0.082 | 0.172 ± 0.025 | 103% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ullah, N.; Chen, W.; Noureen, B.; Tian, Y.; Du, L.; Wu, C.; Ma, J. An Electrochemical Ti3C2Tx Aptasensor for Sensitive and Label-Free Detection of Marine Biological Toxins. Sensors 2021, 21, 4938. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21144938

Ullah N, Chen W, Noureen B, Tian Y, Du L, Wu C, Ma J. An Electrochemical Ti3C2Tx Aptasensor for Sensitive and Label-Free Detection of Marine Biological Toxins. Sensors. 2021; 21(14):4938. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21144938

Chicago/Turabian StyleUllah, Najeeb, Wei Chen, Beenish Noureen, Yulan Tian, Liping Du, Chunsheng Wu, and Jie Ma. 2021. "An Electrochemical Ti3C2Tx Aptasensor for Sensitive and Label-Free Detection of Marine Biological Toxins" Sensors 21, no. 14: 4938. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21144938

APA StyleUllah, N., Chen, W., Noureen, B., Tian, Y., Du, L., Wu, C., & Ma, J. (2021). An Electrochemical Ti3C2Tx Aptasensor for Sensitive and Label-Free Detection of Marine Biological Toxins. Sensors, 21(14), 4938. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21144938